Joshua M. Matson, "Between the Testaments: The History of Judea Between the Testaments of the Bible," in New Testament History, Culture, and Society: A Background to the Texts of the New Testament, ed. Lincoln H. Blumell (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2019), 3-18.

Joshua M. Matson is a PhD candidate at Florida State University.

The four centuries that precede the Common Era are known by a variety of names. The Jews refer to this time as the Second Temple period, emphasizing the return of the faith’s central sacred space. Protestant Christians often refer to this time as the intertestamental period, acknowledging the interlude between the faith’s two primary collections of sacred text. Orthodox Christians and Catholics prefer the deuterocanonical period, highlighting the production and acceptance of additional religious texts such as the Apocrypha. In recent years, some Christians have also named it the Four Hundred Silent Years, suggesting a lack of prophetic activity between the prophet Malachi and the New Testament apostles. The varied names of this period serve as a fitting introduction to a time that attempted to bridge gaps in the historical and religious record but was fraught with division.

The biblical record reveals little concerning the events of these four centuries. Only the books of Ezra, Nehemiah, Haggai, Zechariah, and Malachi are explicitly contemporaneous with events following the Babylonian exile. Malachi, composed around 420 BC, completes the record of the Old Testament, leaving a considerable gap of commentary on the political, social, and religious developments in the time between the conclusion of the Old Testament and the beginning of the New Testament. While various historical sources shed additional light on the history of this period in Judea, recent discoveries such as the Dead Sea Scrolls and a renewed appreciation and acceptance for noncanonical Jewish literature have added a considerable amount of information pertaining to the Jewish history that preceded the events of the New Testament. From these historical sources, we can bridge the gap between the testaments of the Bible.

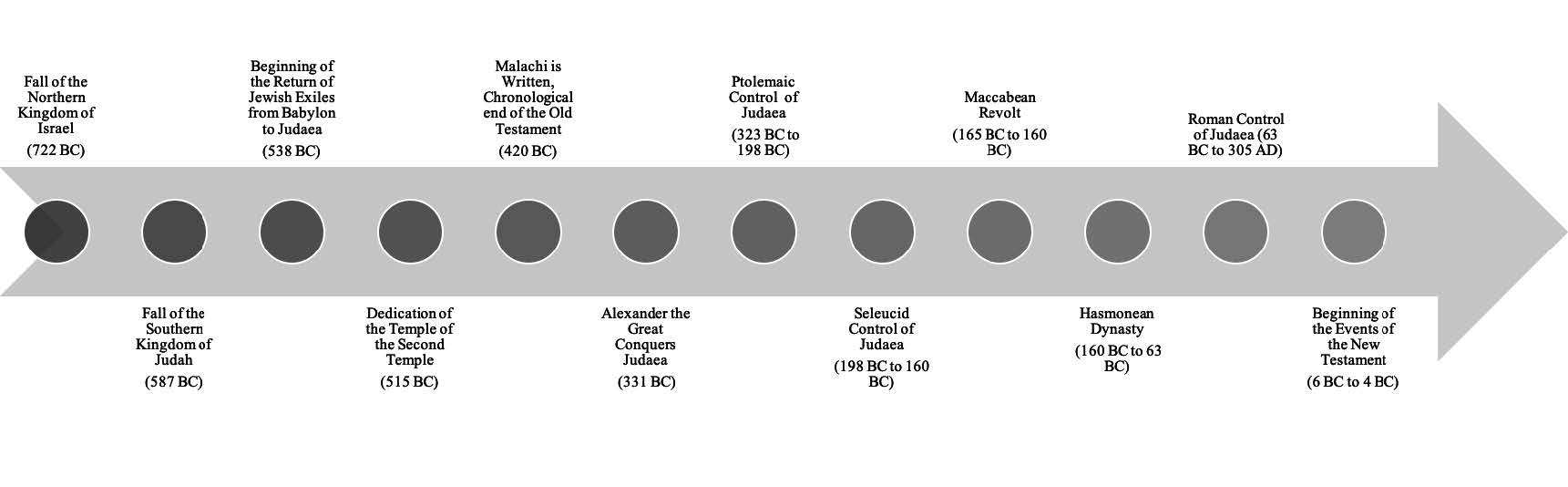

Table 1. Timeline between the Old and New Testaments.

Table 1. Timeline between the Old and New Testaments.

The Period of Destruction and Exile (721–538 BC)

Prior to the destruction of the northern Israelites in 722 BC and the exile of Jews from Judah in 587 BC, divisions existed among the Israelite people. The books of 1–2 Kings and 2 Chronicles preserve the history of this division between the Northern Kingdom of Israel and the Southern Kingdom of Judah. These kingdoms divided themselves along lines of political, social, economic, and religious ideologies. Beginning in the late tenth century BC, tension abounded as these separate kingdoms attempted to navigate the shifting geopolitical landscape of Israel. While the Southern Kingdom of Judah outlasted the Northern Kingdom by a century and a half, ultimately both fell to domineering world powers that imposed on them their forms of conquest. These conquests began the diaspora or the displacement of Jewish people from the land of Judea.

The Assyrian conquest of the Northern Kingdom of Israel is well documented in the histories of the Old Testament (2 Kings 15:29 and 17:3–6) and in Assyrian inscriptions. Conquering Israel in 722 BC, the Assyrians destroyed Samaria, the capital of the Northern Kingdom, and imposed their method of exile upon the Israelites by scattering nearly all the inhabitants of the ten northern tribes throughout the vast Assyrian empire. A mass return of these Israelite exiles to Judea following the fall of the Assyrian empire is not found among the biblical or historical record, and these tribes are often designated as the lost ten tribes of Israel in later religious texts. These lost tribes dispersed themselves throughout the world in many ways in the following centuries. The Assyrian conquest of the kingdom of Israel foreshadowed the events of the Babylonian conquest of the kingdom of Judah a century later.

The Babylonian conquest of the Southern Kingdom of Judah is similarly documented in the histories and prophetic literature of the Old Testament (2 Kings 25:8–12 and 2 Chronicles 36:17–21) and the Babylonian Chronicles. Jeremiah and Ezekiel are the primary prophetic commentators of the events that are described in the histories of 2 Kings and 2 Chronicles. The Babylonian model of conquest differed from that of the Assyrians, but not radically. Instead of scattering the inhabitants of Judah throughout the empire, the Babylonians focused on exiling waves of Judahite elites over a twenty-year period. First in 606 BC and again in 587 BC, Babylonians carried members of the priestly and royal families of Judah away into captivity. The captivity of 587 BC differed from its predecessor as the Babylonians employed a greater level of destruction by razing the walls of Jerusalem, burning the city, and destroying the temple. In response to the destruction of the city and their central place of worship, the people of Judah in exile remained largely intact and were left to reflect on unfulfilled promises, mourn the loss of their promised land, and devise new ways in which to continue to practice their religion.

While the biblical record focuses primarily on the captivity of the inhabitants of the Northern and Southern Kingdoms, the non-elites who remained in the land of Judea after 587 BC are almost completely lost in the narrative of exile (2 Kings 25:12). The peasantry and those situated in villages and towns throughout the countryside of Judea faced many of the same challenges as the exiles. Left to themselves for a half century, these inhabitants devised their own mechanisms to cope with unfulfilled promises and developed new practices for their religion. These decisions would become a focal point in divisions in the period following the exile and in the New Testament (Ezra 4:4 and 9:1).

The experiences of the elites taken into Babylon dominate the narrative of exile found in both biblical and historical records. Babylonian traditions heavily influenced exiled elites’ responses to the loss of their cultural, religious, and political identity. Because exiles could meet in congregations in Babylon, local synagogues appear to have replaced the temple as the central place of worship. Aramaic replaced Hebrew as the primary language spoken by the people (Ezra 4:7). The Jewish calendar was replaced by the Babylonian. New narratives, including some found in the additional Old Testament writings named the Apocrypha, focus on individuals faithfully living the Mosaic law in exile rather than dwelling in a land of promise (see especially Daniel and Esther). These changes occurred in almost every Jewish community throughout the Babylonian empire.

Jewish communities also held vehemently to the traditions that made them a peculiar people. These communities attributed their failure to remain faithful to God as the primary factor in their captivity. The communities of exiles instituted a religious reform to combat a similar captive fate in the future. These reforms are made manifest in the records produced by the returned exiles. Everyday life appears to have been viewed through the lens of exile, and the religious perspective of the Southern Kingdom of Judah focused on returning to the genesis of Jewish culture, religion, and politics. Exclusive monotheism (Nehemiah 9:6), a renewed adherence to the Mosaic law (Nehemiah 8:2–18), an abhorrence for intercultural marriage (i.e., exogamy, Ezra 9), and a greater commitment to the institutions of the Aaronite priesthood and the Davidic monarchy became trademarks of Jewish identity shortly after the exiles’ return from Babylon. These ideologies likely developed during the period of exile but flourished once the Jewish communities returned to Judea.

Returning from Exile and Judea under Persian Rule (538–331 BC)

The Persian Empire approached conquered peoples differently than the Assyrian and Babylonian Empires. When the Persians defeated the Babylonians in the mid-sixth century BC, they allowed those exiled under Babylonian rule to return to their original lands and maintain an amount of political, cultural, and religious autonomy. In 538 BC, the Persian king Cyrus the Great authorized the rebuilding of the Jerusalem temple and allowed the sacred vessels for the temple to be returned to the city. Coupled with the autonomy that they were granted by the Babylonians, some Jewish communities of the Babylonian exile began to return to Jerusalem, although many remained in Babylon despite Cyrus’s edict (Ezra 1:4–6). These communities intended to carry out their reforms in the promised land free from the divisions and strife that had plagued them prior to the exile. Unsuspectingly, however, they found the land they were returning to inhabited by peoples who had different religious, cultural, and political expectations than their own (Ezra 9:1). The reestablishment of these reformed Jewish communities would take over a hundred years to be realized.

The return of the Jewish communities from exile proved divisive almost immediately. The ‘am haggôlâ (people of the deportation/

The exiles who returned to their promised land moved quickly to regain control of Judea from the people of the land, the adversaries of Judah and Benjamin, and the Edomites. The introduction of new religious and political practices developed in Babylon by the people of the exile and the syncretism of religion and culture by the people already in Judea resulted in contention. Different cultural histories also contributed to this outcome. Haggai, Zechariah, Ezra, and Nehemiah preserve partial histories of this period from the perspective of the returnees from the exile. These records recount the disputes that led to the eventual dividing of Judea into three distinctive regions during the fifth century BC. The people of the land remained in the villages and countryside of Judea as subjects to the people of the exile and vocally opposed the political and religious reforms instituted by the returned exiles, including the building of the Jerusalem temple (Ezra 4:4–5). The adversaries of Judah and Benjamin inhabited the vacated northern territories of Ephraim and Manasseh. Later generations renamed this land Samaria, after the central city of the Northern Kingdom, and named the people Samaritans. Like the reference to “Samaritans” in 2 Kings 17:29, it is uncertain if this is a reference to the same group discussed in the New Testament, as the term is employed to describe both the inhabitants of Samaria and members of the religious group. While the origination and connection of the Samaritans that appear in the New Testament with these settlers in Samaria is unclear, the tensions exhibited at this early period, as well as confrontations discussed below, illustrate why there would be great animosity between Jews and Samaritans in Jesus’s day. Making the cultural landscape even more diverse were the Edomites who inhabited the southern region of Judea, which was later named Idumea (Ezekiel 36:5). Ultimately, the people of the exile regained control of the land of Judah and the city of Jerusalem, but only after a lengthy period of reconstruction and consolidation.

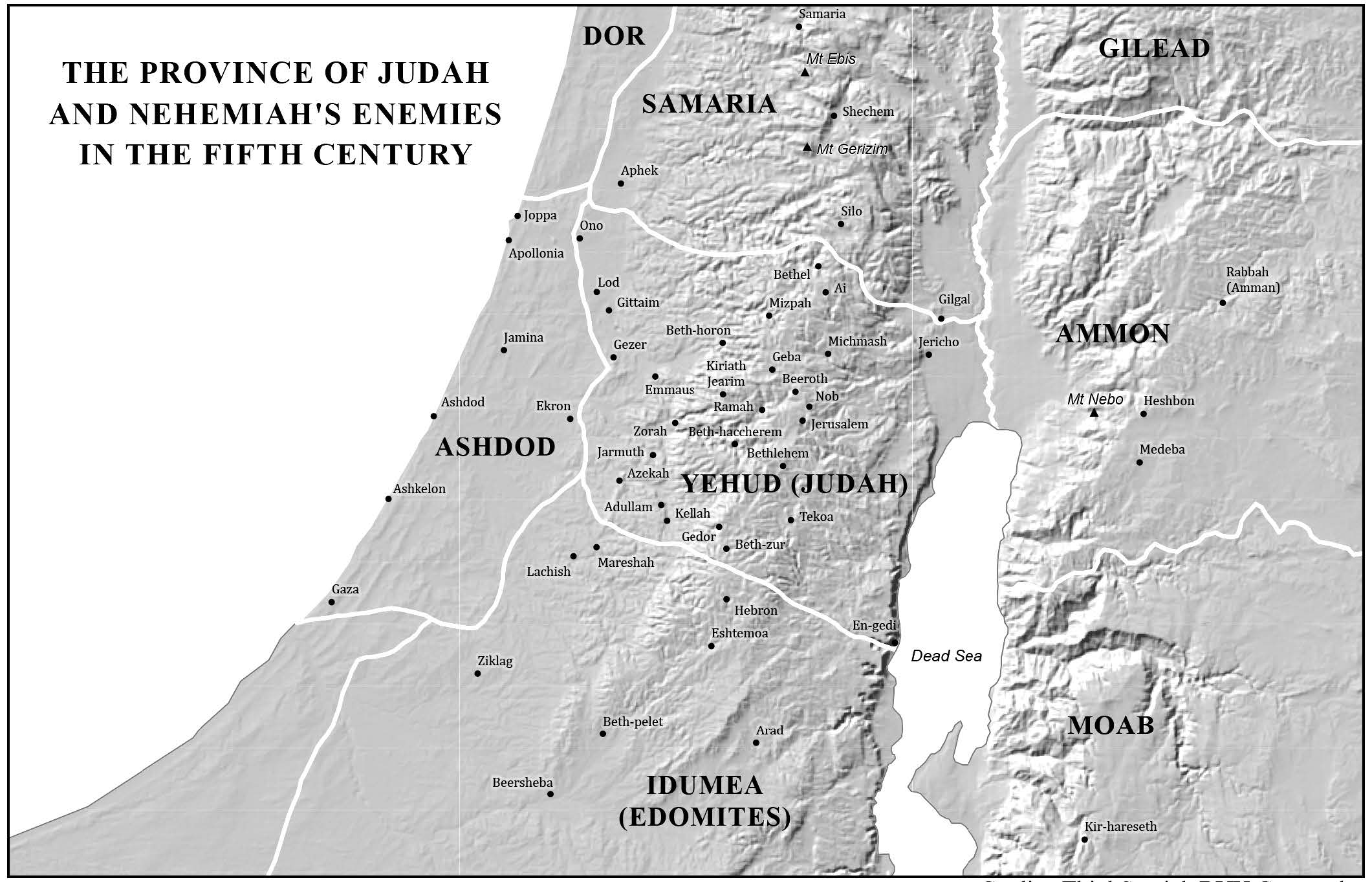

Map of postexile Judea. Map by ThinkSpatial.

Map of postexile Judea. Map by ThinkSpatial.

After gaining control of the region, the people of the exile focused on rebuilding the temple in Jerusalem. The books of Haggai and Zechariah were written during this period, while Ezra recounts these events from a later perspective. These accounts are fragmentary and unclear on the chronology of rebuilding the temple. The Jerusalem community, under the political direction of the governor Zerubbabel (a descendant of the old royal house of David) and the religious direction of the high priest Jeshua, rebuilt the altars and structure of the temple, establishing Jerusalem as the center of the religious hierarchy. This temple was only a shell of the former one built by Solomon, but its establishment centered the religious activities of Judea in Jerusalem for the returned exiles. The dedication of the temple in 515 BC brought religious centrality back to Jerusalem (Nehemiah 12:27–13:3). After the mysterious disappearance of Zerubbabel, Jeshua reappropriated the office of high priest into a central political figure appointed by the ruling nation, creating a small priestly temple-state that received autonomy from the Persian Empire. These events created religious centrality in Jerusalem, but the city remained a place of insecurity with voids in religious and political law.

After nearly a century of reinstatement in Judea, the people of the exile continued to wrestle with the other inhabitants of Judea to restore Jerusalem to its former glory. Aware of the instability in the city and region, Persian kings appointed Nehemiah and Ezra to return to Jerusalem to usher in the restoration of the social, political, cultural, and religious community that had once thrived within its walls. While the sequence of events in the fifth century BC is still unclear, Ezra and Nehemiah sought to reestablish political and religious stability. Strict adherence to the law of Moses, the paying of tithes, Sabbath day observance, and laws against intermarriage with those outside of the community were among the laws instituted during this time, and they played a prominent role in the history of the Jewish people throughout the period. Additionally, Ezra, acting as a scribe and priest within the Jerusalem community, initiated the study of Torah, or the Law contained in the first five books of the Old Testament, ushering in a distinct period of studying religious texts among the Jewish people.

Jewish communities took various approaches to authoritative religious texts following the exile. Although all Jewish communities at the time accepted the Torah, they disputed the authoritative nature of other Jewish texts. Throughout the Second Temple period, authoritative religious texts (primarily the Torah) played an important role in shaping Jewish communities and their interpretation of the Law with each Jewish community maintaining a different opinion of what constituted authoritative scripture. However, groups like the Samaritans interpreted these authoritative texts very differently than the Jews in Jerusalem. Unlike other Jewish communities of the Second Temple period, the Samaritans only adhered to their own version of the Torah (known as the Samaritan Pentateuch) with divergent traditions. One such tradition is the belief that the properly designated location for a central place of worship was Mount Gerizim, not Mount Ebal or, as later dictated, Jerusalem (see Samaritan Pentateuch, Deuteronomy 27:4). This belief was further manifested at this time by the building of a temple. While concerns about the proper interpretation of authoritative texts elevated tensions in Judea during the time of Malachi (420 BC), it served as a primary indicator of each Jewish community’s identity during the Hellenistic period. Judea maintained near complete autonomy throughout the remainder of the dominance of the Persian Empire in the eastern Mediterranean area. Religious communities took advantage of this autonomy.

The biblical and historical records are silent regarding Judea and the events of the next century and a half. Although the Persians engaged in a variety of political and cultural entanglements, the inhabitants of Judea were primarily unaffected by them. This autonomy would be maintained throughout the Persian period but diminished with the overthrowing of the Persian Empire by Alexander the Great and the introduction of Hellenism to Judea.

The Hellenization of Judea (331–164 BC)

As mentioned above, the biblical record is silent about events that occur after the fifth century BC, requiring scholars to look to other sources to create a history of the period. The writings of Flavius Josephus are one prominent source scholars refer to when discussing the history of the Second Temple period. Josephus was a Roman Jew who lived during the first century AD. A political diplomat, military general, and historian, Josephus wrote extensively about the history of the Jewish people. While Josephus wrote other works, Jewish Antiquities and the Jewish War are valuable histories that preserve information about the time between the Old and New Testaments. Antiquities preserves a history of the Jewish people from the creation of the world to the days of Gessius Florus, the Roman procurator of Judea from AD 64–66. Most of the early chapters of this work are drawn from the history presented in the Old Testament. The Jewish War overlaps with Antiquities and preserves a war history of the Jewish people from the rule of the Seleucid king Antiochus IV Epiphanes (175–164 BC) to the aftermath of the destruction of the Jewish temple (AD 70). Many of the things that are known to scholars today about the intertestamental period are based on the histories of Josephus and the Maccabean histories included in the Apocrypha.

Alexander the Great rapidly conquered the Persian Empire through military campaigns between 334 and 324 BC. Alexander gained control of the region of Judea between 333 and 331 BC with a series of campaigns in the western border of the Persian Empire (Antiquities 11.8). Alexander is credited with attempting to unify his conquered empire with the spread of Hellenism (Greek culture and language). The spread of Hellenism through the region of Judea, and to Jews throughout the diaspora, marked a period of shifting ideals and manifestations within Judaism.

Hellenism spread throughout Jewish communities in various ways. Greek became the preferred language of the elite throughout the empire, although Hebrew and Aramaic remained in general use among the inhabitants of Judea. The Hebrew scriptures were translated into Greek in Egypt and utilized throughout the empire. Hellenistic structures like the gymnasium and the stadium became the social centers of communities, even in Jerusalem. Some Jewish inhabitants removed the distinguishing mark of circumcision through a variety of methods, including an operation known as epispasm. Others, including some high priests, took Greek names (see Antiquities 12.5). Education of elite citizens emphasized Hellenistic culture over traditional Jewish history. Jewish communities adopted and fought against Hellenism to varying degrees. While some communities believed that the adoption of some elements of Hellenistic culture did not weaken Jewish identification, others became outraged and rose in rebellion against it.

The inhabitants of Judea found themselves in a precarious political situation following the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC. Immediately following his death, Alexander’s generals divided the conquered lands among themselves. These generals began dynasties that determined the destinies of various lands throughout the empire. The Ptolemies in Egypt and the Seleucids in Syria-Mesopotamia governed the people living in Judea for almost two hundred years. Originally, the Ptolemies ruled Judea. Under Ptolemaic control, the inhabitants of Judea experienced a change in imperial protocol. While the Persians had allowed a great degree of autonomy to the people of Judea, the Ptolemies constructed a large bureaucracy that wielded considerable political power. On the whole, Jews in Judea and Egypt flourished under Ptolemaic control and had a certain degree of autonomy.

Located on the border between these two dynasties, Judea observed battles between the Ptolemies and the Seleucids that penetrated community dynamics. These battles forced individuals and communities to take sides, hoping that their side would prevail and reward them for their loyalty. High priests, now the preeminent position of authority and power among the Jewish people in Judea, aligned themselves with outside forces for political gain, appointment, and advancement. In 198 BC, the Seleucids wrestled control of Judea away from the Ptolemies.

Under Seleucid rule, the Jewish communities in Judea experienced a lessening of religious and political autonomy. While the Seleucids approached ruling their territories through cooperation with established elites, these elites often failed to cooperate with those who had opinions differing from those within the Seleucid hierarchy. In Judea, the Seleucids provided financial and political incentives to the elites of high priestly families in exchange for loyalty to Syrian rulers and the implementation of Hellenization. As individuals obtained the position of high priest by bribery, rather than lineage, and Jewish communities disputed the appropriate degree of Hellenization allowed by the Jewish law, considerable divisions arose among the Judean people. The Maccabean histories, found in the Apocrypha as 1 and 2 Maccabees, preserve an account of the events surrounding this period.

According to the Maccabean narrative, the ascension of Antiochus IV Epiphanes to the throne of Seleucid Syria marked the decisive moment in the divisive atmosphere in Judea between Jews and Hellenistic rulers. Around 175 BC Antiochus raised taxes on the inhabitants of Judea to fund his failed military campaigns into Egypt. Additionally, Jason, a highly Hellenized Jew, successfully bribed Antiochus to appoint him to the position of high priest. Three years later, Menelaus, a highly Hellenized Jew devoid of priestly lineage, acquired the position from Jason. In 167 BC, Antiochus collaborated with the Hellenized Jewish elite in Jerusalem to convert the Jerusalem temple into a pagan shrine. Some sources, including 1 and 2 Maccabees, suggest that Antiochus instituted these changes to force Greek culture, religion, and language upon the inhabitants of Judea (1 Maccabees 1:10–15). Scholars of the Second Temple period debate Antiochus’s motives and the extent of his forced reform. However, the results of Antiochus’s decisions are undisputed as they led to a revolution in Judea against Hellenistic rule.

A Period of Revolt and Restitution (165–160 BC)

Mattathias, a priest from outside of Jerusalem, together with his five sons, led the revolt against Hellenistic rule. Employing guerrilla-style tactics, the rebels attempted to drive the Seleucids out of Judea and reinstate political, cultural, and religious autonomy to the region (1 Maccabees 2:1–14). Mattathias and his supporters initiated their assaults on the villages and towns of Judea in 167/

Judas, one of Mattathias’s sons who was given the new name of Maccabeus or Maccabee (fighter or hammer), became the primary leader of the rebellion (1 Maccabees 3:1–9). Under Judas’s leadership, the revolutionaries defeated the Seleucid forces near the city of Jerusalem in 164 BC (Jewish War 1.1). Following their victory, they easily regained control of the city. Almost immediately, Judas’s followers focused on purifying and rededicating the temple in Jerusalem. Future generations commemorated the events of this rededication with the festival of Hanukkah. Around the same time the revolutionaries gained control of Jerusalem, Antiochus died, igniting a succession crisis in the Seleucid Empire. The Jews took advantage of the political instability, and what began as a fight for religious freedom became an all-out war for Jewish independence (Antiquities 13.7).

After restoring the temple in Jerusalem and appointing a high priest whom they believed to be the rightful successor to the position (a decision that would further divide other Jewish communities who did not agree), Judas and his followers focused on forcing the Seleucids out of Judea. Judas marshaled a series of successful military campaigns throughout Judea in the following years. In 160 BC, however, Judas was killed by Seleucid forces, creating a leadership crisis among the rebelling Jews. Disoriented by their defeat, Judas’s forces retreated to the countryside of Judea. The Seleucids quickly regained control of Jerusalem and appointed Alcimus, a highly Hellenized Jew outside of the lineage of the high priestly families, to the position of high priest. The revolutionaries regrouped and appointed Jonathan, one of Judas’s brothers, as their new leader. In 159 BC Alcimus died, and Jonathan led a successful campaign to regain Jerusalem (Jewish War 1.2).

While Jonathan ruled as a general for the ensuing years, in 152 BC he tactfully negotiated with the Seleucid rulers and obtained an appointment to be high priest in Jerusalem. The official recognition of Jonathan by the Seleucids began a period of autonomous rule like that enjoyed under the Persians. Descendants of the family of Mattathias officiated in the role of both political leader and high priest for over a century, creating the Hasmonean dynasty.[1] Although Jonathan was not from a high priestly family line, he convinced the Jewish people that he and his posterity would maintain the position of high priest only until the advent of another prophet who could successfully identify a rightful successor (1 Maccabees 14:41). This change in religious practice, coupled with the divisions throughout Judaism over Hellenism and the revolt against it, led to the creation of various Jewish factions, including the Pharisees, Sadducees, and Essenes (Antiquities 18.1). These groups constantly contended with one another over religious and political matters. Some of these religious factions, including the community that authored some of the Dead Sea Scrolls, moved away from Jerusalem to establish their own religious communities, free from the rule of the Hasmoneans.

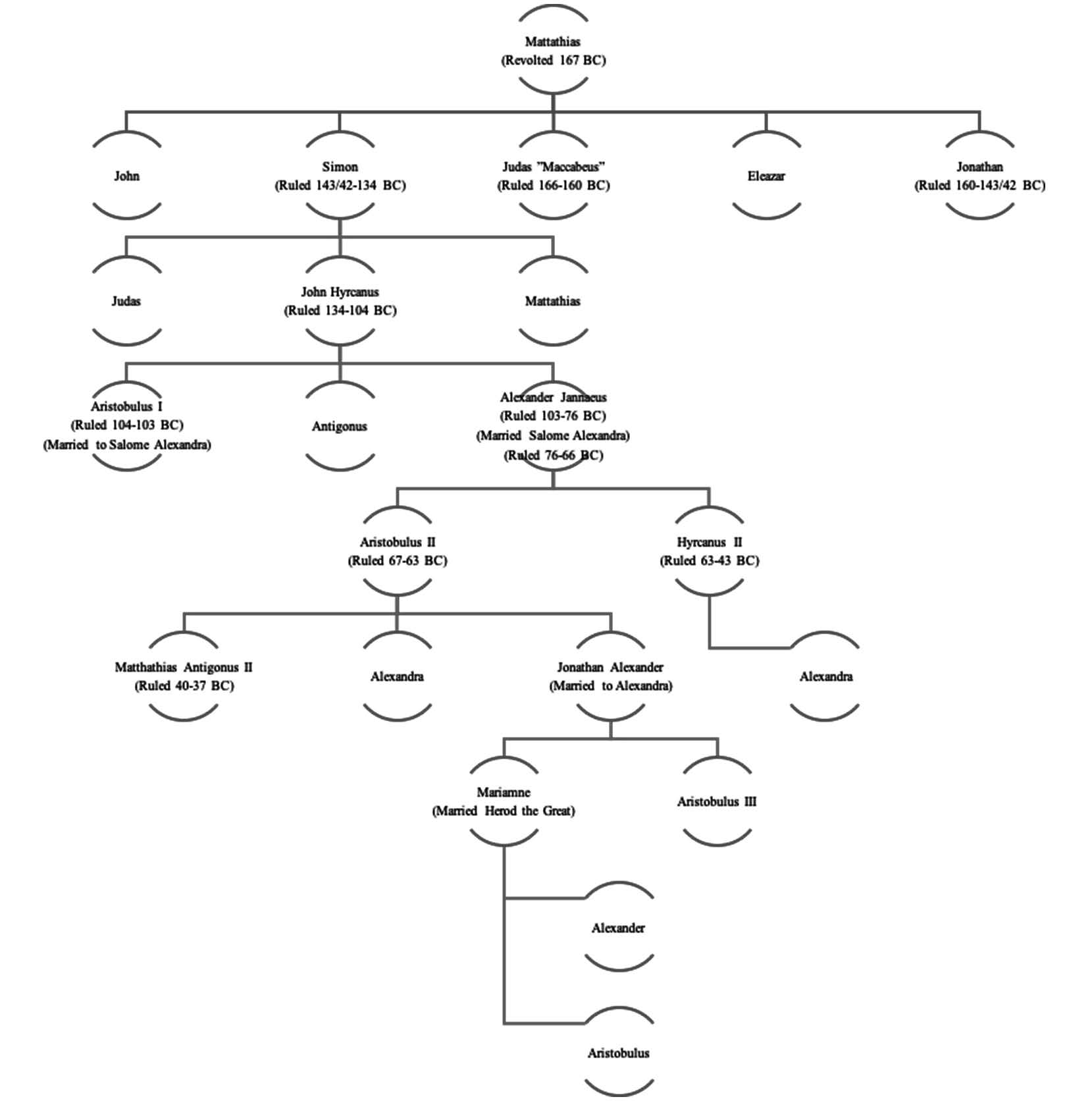

Table 2. Hasmonean family tree.

Table 2. Hasmonean family tree.

The Hasmonean Dynasty (160–63 BC)

Political instability in the Seleucid Empire ensured that the beginnings of the Hasmonean dynasty were anything but ideal and smooth. The Seleucids engaged in various internal battles between claimants to the throne. Although Jonathan and his family had been granted autonomous authority in Judea, the Seleucid claimants persuaded him to participate in numerous military campaigns to maintain that autonomy (Antiquities 13.5). During one of these campaigns, those antagonistic to the Hasmoneans and the claimant they supported killed Jonathan, leaving the Jewish state without a leader. The Jerusalem assembly appointed Simon, the last remaining brother of Judas, as ethnarch (ruler of the people) and high priest (Antiquities 13.6).

Simon continued the campaign for Judean independence. One of the claimants to the Seleucid throne, Demetrius II, made concessions with Simon and the Jewish people in 142 BC in exchange for their support in obtaining control of the empire. Complete Jewish independence was among these concessions. In 141 BC, Simon led a successful campaign against one of the final remaining Greek and highly Hellenized Jewish communities at the Acra fortress, marking the beginning of Jewish independence (1 Maccabees 13:52–14:15).

Jewish independence preceded the restitution of the Jewish state to lands that were part of Davidic and Solomonic kingdoms in earlier times. Simon’s son-in-law orchestrated Simon’s assassination in 135 BC, leaving the throne of Judea and the position of high priest in the control of Simon’s son John Hyrcanus. Although Antiochus VII, the ruler of the Seleucids, attempted to regain some of the lands the Hasmoneans had captured during the revolts, Hyrcanus negotiated a deal with the Seleucids to maintain autonomy in Judea in exchange for tribute payments for the cities in their control. This agreement ensured that Hyrcanus reigned for over twenty years and allowed him to lead military campaigns to restore the borders of the old kingdom (Antiquities 13.8). Among these campaigns, Hyrcanus annexed Idumea in the south and persuaded the inhabitants to convert to Judaism. He also moved to the north and acquired Galilee and Samaria. In Samaria, he destroyed the temple on Mount Gerizim, causing a final divisive blow between the Samaritans and the Jews. Hyrcanus died in 104 BC, leaving the throne to his son Aristobulus I (Antiquities 13.10).

Aristobulus I ruled over Judea for only a year but changed the Hasmonean state for the remainder of the dynasty. After gaining control of Judea, Aristobulus continued to push the boundaries of the Hasmonean state toward those that existed during the kingdoms of David and Solomon. Further, Aristobulus took upon himself the title of king (Antiquities 13.11). Previous rulers in the dynasty had avoided the title for a variety of reasons, but now the rulers would be known as both priests and kings. This development reflected and molded Jewish expectations of the coming messianic age and proved divisive among the various Jewish factions throughout Judea.

Map of the expansion of the Hasmonean Empire.

Map of the expansion of the Hasmonean Empire.

Map by ThinkSpatial.

Aristobulus’s heir to the throne, his brother Alexander Jannaeus, furthered the divide in Judea during his twenty-seven year reign. Jannaeus continued to expand the borders of the Hasmonean state, attaining the borders of the earlier kingdom of Solomon, and took upon himself the title of king. Jannaeus faced a rebellion from the Pharisees and other Jewish factions because of his support for the Sadducees and his adoption of many Hellenistic practices. These internal conflicts soon spilled over into civil war (Antiquities 13.13). The opponents of Jannaeus solicited the help of Demetrius III, a rival to the Seleucid throne, and engaged in a lengthy series of battles. Jannaeus ultimately prevailed and executed eight hundred of his opponents during a victory feast in Jerusalem. Following Jannaeus’s death in 76 BC, his wife Alexandra Jannaea Salome became queen. This form of succession, from husband to wife, resembled that of other Hellenistic kingdoms (Antiquities 13.16). The dynasty that started as a defense of religious freedom and independence against Hellenistic rule now resembled Hellenism itself.

Salome reigned masterfully from 76 to 67 BC and facilitated further divisions among the Judeans. She shifted the religious alliances of the crown and aligned herself with the Pharisees, a move that angered the Sadducees, who had been supported by her husband. Salome’s support for the Pharisees included placing them among the ruling class of the society. Further, Salome installed her son, Hyrcanus II, to the position of high priest and expanded the power of the Sanhedrin, a ruling body of religious leaders. This move granted the Sanhedrin power to pronounce judgment in religious matters that had previously been reserved for the high priest. Salome’s death signaled the beginning of a civil war between Hyrcanus II and his brother Aristobulus II and began the decline of the Hasmonean dynasty (Antiquities 14.1).

The civil war between Hyrcanus and Aristobulus introduced the Romans into political matters in Judea. Aristobulus almost immediately seized the throne from Hyrcanus. After the bitter takeover, Hyrcanus fled to Petra and allied himself with Rome’s eastern opponents, the Nabateans. Convinced that his brother would continue to pursue him until his death, Hyrcanus led a joint assault on Jerusalem with his newfound allies. During the fierce battle, both Hyrcanus and Aristobulus appealed to Rome for intervention (Antiquities 14.3). The Romans conquered the remnants of the Seleucid Empire in the seventies BC and began to expand throughout the Eastern Mediterranean. Rome intervened and expelled the Nabateans, opening the way for Aristobulus to again prevail over his brother. Eventually, the Roman general Pompey interrogated both brothers to decide who should reign. Aristobulus and his supporters made numerous fateful mistakes, so the Romans sided with Hyrcanus and assigned him to the positions of high priest and ethnarch, revoking the title of king and taking control of the Hasmonean kingdom (Jewish War 1.6). Again, the inhabitants of Judea found themselves under the control of a foreign power.

Roman Rule through the Herodian Dynasty (63 BC–AD 70)

Roman rule over Judea began in a way that divided the Jewish people from their new overseers religiously and geographically. Following the intervention of the Romans in the civil war between Hyrcanus and Aristobulus, Pompey explored the Temple Mount in Jerusalem. Curiously, Pompey visited the Holy of Holies, which he had heard was void of any cultic objects (Jewish War 1.7). Jewish communities joined together to express their anger over the insensitivity of this Roman ruler. Additionally, although Hyrcanus II ruled over Jerusalem and the temple-state, the Romans divided the remaining lands that had been part of the Hasmonean kingdom and restored independence to each region. In this realignment, the Samaritans, Idumeans, and other Jewish and non-Jewish regions of the Eastern Mediterranean were placed under the control of the Roman proconsul of Syria.

The realignment of the region lasted through the life of Pompey. Following Pompey’s death in 48 BC, Hyrcanus II obtained the support of Julius Caesar. Caesar appointed Antipater, the trusted advisor of Hyrcanus, to the position of governor of Judea and reconfirmed the position of high priest upon Hyrcanus with added political powers. Furthermore, Caesar returned lands that had been realigned by Pompey to the jurisdiction of Judea. For the remainder of Caesar’s reign, the remnants of the Hasmoneans controlled Judea with little intervention from the Romans (Antiquities 14.8).

Caesar’s death in 44 BC triggered another period of instability throughout the Mediterranean. In Judea, Aristobulus II’s son Antigonus seized the opportunity to take back control of the region and establish an independent kingdom. Antigonus allied with Rome’s primary opponent in the East, the Parthians, and attacked Hyrcanus in Judea. After capturing Jerusalem, the forces of Antigonus killed Antipater and imprisoned Hyrcanus. Antigonus proclaimed himself king of Judea and attempted to reestablish the autonomy of the Hasmonean dynasty. However, the Romans appointed Herod, one of Antipater’s sons, to establish their own dynasty over Judea (Antiquities 14.9).

Herod stands as an example of the complex worlds of Judea in the final century before Christ. Herod’s family is situated at the crossroads of the old and the new in many ways, bridging divides and creating new ones. Herod presented his ancestry as deriving from the tribe of Judah and the Babylonian exile. His grandfather and father were Idumeans and converts to Judaism. Both acquired social status and position in the Hasmonean state under Salome and Hyrcanus II. Herod’s mother came from a Nabatean family that likely aligned themselves with Hyrcanus in his campaign to regain the throne from his brother. Herod married Mariamne I, the granddaughter of both Aristobulus II and Hyrcanus II. Herod’s marriage tied him directly to the Hasmonean royal line. Ultimately, Herod’s father, Antipater, appointed Herod governor of Jerusalem in 47 BC. The assault by Antigonus in 44 BC limited Herod’s original appointment, but political allegiances reinstated him.

The Romans grew tired of the Hasmonean struggles to regain autonomous power in Judea and looked for a suitable replacement. Herod’s knowledge of the political system of the Romans and the Jews, as well as his ability to maintain both systems, made him an ideal candidate for appointment. Herod’s lineage, however, prevented him from being accepted by the Jews as a legitimate heir to the position of high priest. Instead, Rome proclaimed Herod king of Judea, Galilee, and Perea in 40 BC, and together they recaptured Jerusalem from Antigonus and the Parthians in 37 BC. Herod’s appointment was not an autonomous kingship, but the role of a client king. Herod and his descendants occupied such positions in Judea until almost AD 100.

Herod’s rule over Judea mirrored that of the Hasmoneans and those that ruled an independent Judea before them. The support Herod received from the overseeing Romans distinguished him from the earlier kingdoms. Herod expanded the borders of Judea to the size that had been obtained by the Hasmoneans. Herod fortified these borders by erecting fortresses throughout the region. Additionally, he initiated an extensive building project to rebuild the Tomb of the Patriarchs and the capital of Samaria and to construct new cities. Herod’s renovations to the Jerusalem temple returned the sacred edifice to the glory and prestige that it had enjoyed in the days of Solomon. Herod also engaged in construction projects that were clearly Hellenistic. In Jerusalem, Herod constructed a theater, an amphitheater, a hippodrome, temples to foreign deities, and a golden eagle above the gate to the temple. The Jews in Judea oscillated in their support for their complicated client-king.

Herod executed laws and judgment in erratic ways to preserve his position of power. He ordered that Aristobulus III, a high priest of Jerusalem and the brother of his wife Mariamne, be drowned so that he could appoint a less established family to the high priesthood. This appointment, and the consistent appointing and disposing of high priests, ensured loyalty to Herod and prevented the possibility of revolt by the temple-state. Similarly, he executed his wife Mariamne and two of her sons to prevent familial conflict between the children he fathered from his ten wives that could jeopardize his authority in the eyes of the Romans. Ultimately, following Herod’s death in 4 BC, the Romans left the region of Judea in control of his descendants.

Herod’s posterity who ruled over Judea play a central role in the narrative of the New Testament. Rome appointed Herod’s son Archelaus ethnarch of Judea. Archelaus’s brother, Antipas, became the tetrarch (ruler of a quarter) of Galilee. Philip, the half-brother of Archelaus and Antipas, became the tetrarch of the gentile region of Iturea on the eastern side of the Jordan River. The history of New Testament Judea predominantly occurs in the areas ruled by these three sons of Herod. Archelaus’s inability to control the region of Judea in a similar manner to his father led to his removal in AD 6. Instead of appointing another ethnarch, Rome installed a prefect of equestrian rank over Judea. Pontius Pilate served as the fifth prefect over Judea. Shortly after his rule, the title of governor was changed to that of procurator and the Jews were again limited to controlling the temple-state while others controlled the political landscape of Judea.

Two of Herod’s grandsons appear prominently in Judea throughout the New Testament narrative. Rome exiled Antipas in AD 37 and appointed Agrippa I, Herod’s grandson by Mariamne, first as heir to Philip’s tetrarch and then in AD 39 expanded his rule over Antipas’s tetrarchy. Additionally, Rome allotted the expanse of Judea to mirror the borders of previous kingdoms. Following Agrippa I’s death in AD 44, Rome reinstated their own rulers over Judea because Agrippa II was too young to rule in his father’s stead. In AD 50, the Romans appointed Agrippa II as overseer of the kingdom of Chalcis in the north. Additionally, the Romans appointed Agrippa II as high priest, where he deposed the Sadducee high priest Ananus, adding to the tumultuous tension between Jews and Romans that would eventually erupt in rebellion. These revolts ultimately led to the temple’s destruction in AD 70 and the removal of the Jews from Judea.

Conclusion

A brief overview of the history of the Second Temple period highlights that this was a time of divisiveness within Judaism. Jewish communities of this period were at odds with those who ruled over them. These tensions, especially against the Hellenistic rulers that followed an age of autonomy under Persian rule, grew as Jewish communities experienced constant fluctuation between autonomy and oppression. Additionally, Jews frequently found themselves at odds with one another. From the earliest days of their return from exile, the Jews of this period struggled to create a cohesive identity, holding to traditions and adaptations that were at the core of their uniqueness, no group wanting to sacrifice their identity at the cost of another. This history emphasizes the consistent attempts made by Jewish communities and outside leaders to bridge the divides that existed in the social, cultural, political, and religious aspects of their time. It also emphasizes that while attempts were made to bridge these divides, those bridges frequently were adorned with the peculiarities of those in power at the cost of those who were not. Although the biblical sources for this period are scarce, the historical record reveals seeds that were planted within the Old Testament history that grew in adversity and sprouted roots of discord and contention among the Jews that span throughout the text of the New Testament.

Further Reading

Brown, S. Kent, and Richard Neitzel Holzapfel. Between the Testaments: From Malachi to Matthew. Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2002. Goodman, Martin. “Jewish History, 331 BCE–135 BCE.” In The Jewish Annotated New Testament, edited by Amy-Jill Levine and Marc Zvi Brettler, 507–13. New York: Oxford, 2011. Grabbe, Lester L. A History of the Jews and Judaism in the Second Temple Period, vol. 4. New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2006. Holzapfel, Richard Neitzel, Eric D. Huntsman, and Thomas A. Wayment. Jesus Christ and the World of the New Testament. Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2006.

Notes

[1] The origin of the name Hasmonean is a point of uncertainty among scholars. The term originates in the histories of Josephus and may not have been used prior to his written histories. For Josephus, the name pays homage to an ancestor of Mattathias named Hašmônay who was a descendant of Joiarib (see Jewish War 1.36 and Antiquities 11.111 and 20.190, 238). This name would be significant as it would tie Mattathias and his children into a priestly line of the Aaronite Priesthood. An alternative scholarly opinion is that the name Hasmonean is linked to the village of Hesbon (see Joshua 15:27), making the reference perhaps a link to Mattathias’ ancestral home. A final opinion among scholars is that the name Hasmonean is taken from the Hebrew “Ha Simeon” a reference to the tribe of Simeon, one of the twelve tribes of Israel.