Nauvoo: A Place Where We Can Build A Temple

Don F. Colvin, “Nauvoo: A Place Where We Can Build a Temple,” in Nauvoo Temple: A Story of Faith (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, 2002), 3–14.

Walking the streets of old Nauvoo stimulates reflection, motivating one to wonder what this city must have been like when it was rivaling Chicago to be the largest in all of Illinois. Just prior to the forced exodus of its citizens to the West, when the city was at its height, Nauvoo boasted a population of twelve to fifteen thousand citizens. [1] One observer reported that Nauvoo’s inhabitants were housed in “at least two thousand houses in the city proper, and in the suburbs five hundred more.” Twelve hundred of these were described as “tolerably fit residences,” with probably five hundred being good brick houses, some of which were “elegantly and handsomely finished residences." [2] By January 1846 the population of Nauvoo had swelled to its greatest numbers as persecution and mobbings drove Church members from their homes in surrounding communities to seek refuge in the city. Many of these new citizens were housed in wagons or temporary shanties as they made preparations to leave the city and cross the plains to the West.

As impressive and substantial as are some of the restored homes now standing in Nauvoo, they are insignificant when compared to the city’s most prominent structure, the Nauvoo Temple. Visible from a long distance, it stood on a bluff overlooking the city and the mighty Mississippi River. One non-Mormon visitor noted that the temple was “larger than any building west of Cincinnati and north of St. Louis,” and he described it as “the finest building in the west. [3] Another visitor praised it in somewhat exaggerated terms as “the most splendid and imposing architectural monument in the new world . . . unique and wonderful as the faith of its builders." [4] The Nauvoo Temple was unquestionably one of the finest structures of nineteenth-century America. Built at great cost and sacrifice, its erection was a dominant concern of the entire Church during the Nauvoo period of Latter-day Saint history. The building has forever left its imprint on the history of Mormonism and the state of Illinois.

Who Were the Latter-day Saints?

Who were these people who built so much and so well in just a few short years? What was it that motivated them to sacrifice so much of their time, means, and energy—even under intense persecution—to build such a building and such a city, only to walk away and leave it all to the elements and to their persecutors? Commonly called Mormons, they were members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. The bulk of them had formerly been residents of New England, the eastern states, and southern Canada. Later, as the city grew, these were joined by converts from the southern states and the British Isles. Organized in Fayette, New York, 6 April 1830, the Church claimed to be the original Church of Jesus Christ, restored to earth in the latter days. A basic belief was acceptance of their Church president, Joseph Smith (as well as each of his successors), as a true prophet of God.

From New York the movement spread west as early as 1831, establishing settlements in northeastern Ohio and western Missouri. Kirtland, Ohio, was the main center of activity in the early 1830s, and it was here that the Latter-day Saints constructed their first temple. Due to apostasy and persecution, Church members left Ohio in 1837 and 1838 to the other main center of the Church in western Missouri. Their arrival in large numbers was perceived as an economic, social, and religious threat to earlier settlers, resulting in opposition and persecution. Motivated by political and religious reasons, armed mobs plundered Mormon homes and settlements. As the Saints marshaled their members for defense, a near state of war existed in western Missouri. Siding with the mob element, Missouri governor Lilburn W. Boggs issued an order of extermination in October 1838. In part it read: “The Mormons must be treated as enemies, and must be exterminated or driven from the state if necessary for the public peace." [5]

As the extermination order was put into effect, Church leaders were imprisoned and held under threat of the penalty of death. Church members were forced to leave their homes and lands and flee the state. Many spent the winter of 1838–39 as guests of the city of Quincy, Illinois, whose citizens were moved to sympathy for the refugee Latter-day Saints. Some wintered in wagons, in barns, or in dugouts along the riverbank, while others found similar refuge in Iowa.

After six long months of incarceration, Joseph Smith and those with him were allowed to escape from prison. They joined the main body of Church members on 16 April 1839 at Quincy, Illinois. The question of where to go to build anew now occupied the attention of all. After investigating possible sites, Church members purchased large farms at Commerce, Illinois, and in Iowa. The terms of purchase were generous, allowing for long-term payment. Sparsely inhabited and undeveloped, Commerce became the new home of the exiles.

The City of Nauvoo

Commerce, with but few residents, was largely a “paper town,” ushered into existence by eastern speculators who in 1837 established on paper what was to be the city. [6] Due in part to the financial panic of 1837, the intentions of these early founders were never realized, and the land awaited development under its new owners, the Latter-day Saints. Joseph Smith described the appearance of the settlement as he arrived to take up residence.

When I made the purchase . . . there were one stone house, three frame houses, and two block houses, which constituted the whole city of Commerce. Between Commerce and Mr. Davidson Hibbard’s, there was one stone house and three log houses, including the one that I live in, and these were all the houses in this vicinity, and the place was literally a wilderness. The land was mostly covered with trees and bushes, and much of it so wet that it was with the utmost difficulty a footman could get through, and totally impossible for teams. Commerce was so unhealthful, very few could live there; but believing that it might become a healthful place by the blessing of heaven to the Saints, and no more eligible place presenting itself, I considered it wisdom to make an attempt to build up a city. [7]

Throughout the summer of 1839 the Saints continued to gather on lands purchased by Church authorities. Presenting a general appearance of great destitution, the Saints occupied the lower ground along the bank of the river. Extending a considerable distance above the camps was a succession of ponds filled with stagnant water and decaying vegetation. Men were put to work cutting ditches to the river for the purpose of draining the swampy land. This project was completed during the summer of 1840. During this time many fell prey to sickness, mostly in the form of malaria fever carried by mosquitoes bred in the swampy land upon which they were settling. After the land had been drained, conditions were improved greatly, and the land was claimed for habitation and cultivation.

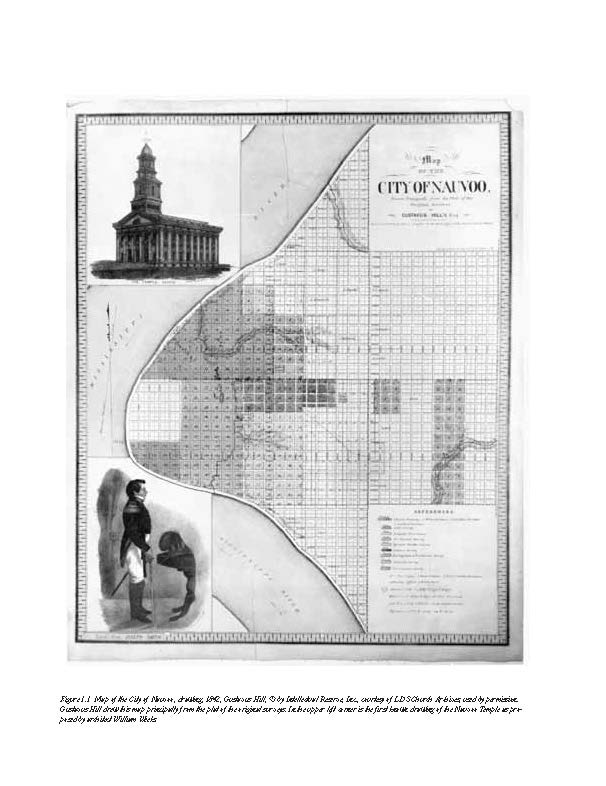

In September 1839 streets and lots were laid out in what was to be a new city called Nauvoo, meaning a beautiful situation or place. The city was given official status on 21 April 1840, when the United States Postal Department changed the name of the local post office at Commerce to Nauvoo. On 16 December 1840 the Illinois governor signed into law an act officially chartering the city. [8]

Nauvoo was a well-planned city laid out with broad streets; it evidenced many features now common in zoning and farsighted city planning. It grew in both population and improvements at a phenomenal rate. By August 1840 the population was estimated at more than three thousand inhabitants. [9] By the summer of 1841, it had grown to some eight or nine thousand citizens, and from then on it vied with Chicago for claim as the largest city in the state. [10]

The Saints from far and near were urged to gather and build up the city. This call resulted in a swelling of the population by a steady flow of new citizens. Converts came from all parts of the United States as well as from Canada and England. The influx of Church members from England began as early as June 1840. By 1846 a total of five thousand Saints had immigrated to America, the greater part of whom settled in Nauvoo. [11] The effect of these new citizens upon the culture, beauty, and industry of the city was considerable. They brought skills that contributed to the growth of industry and building. In addition, they contributed their talents in the cultural and intellectual activities of the city.

Exodus from Illinois

In the short space of six years, Nauvoo rose to attract the interest and attention of people from far and near. It was visited by a number of notable travelers of the time, with favorable comment. It fast became an industrial and shipping center and gave promise of becoming a cultural center as well. Due to its rapidly growing population, Nauvoo had significant political impact in Hancock County and the state of Illinois. As the city grew in power and influence, attitudes of many of its neighbors changed. Some developed bitter opposition to the cause of Mormonism. Most of these feelings grew out of political motivation. Added to this was continued harassment and agitation against Church leaders by old enemies from Missouri. Another source of the growing difficulty came from apostates and dissenters who showed their bitterness by striking out in acts of aggression against the Church and its leaders. Still another influence was that of envy and jealousy on the part of some citizens in neighboring towns who looked upon the rising wealth and industry of Nauvoo as diminishing the economy and growth of its neighbors. The unity and hard work of the Mormons were producing material growth while the rest of the state languished in a financial depression. To others the liberal Nauvoo Charter and the presence of the Nauvoo Legion excited fears and suspicions of religious oppression by zealous Mormons. [12]

A combination of these factors, along with rumors and other influences, united in an ever-growing storm of opposition and persecution. The situation gradually worsened, culminating in mob violence on 27 June 1844, when Church president Joseph Smith and his brother Hyrum were murdered by an armed mob. [13] A mournful silence settled over Nauvoo and the Latter-day Saints. Stunned by the tragic events, Church members waited for direction. The void of leadership was filled when the Twelve Apostles returned from their missions in the eastern states and were sustained as the new presiding authorities. [14] Under this new leadership, every effort was exacted toward completion of the temple and continued expansion of the Church. Contrary to the hopes of its enemies, it soon became apparent that the movement had taken on a new vitality.

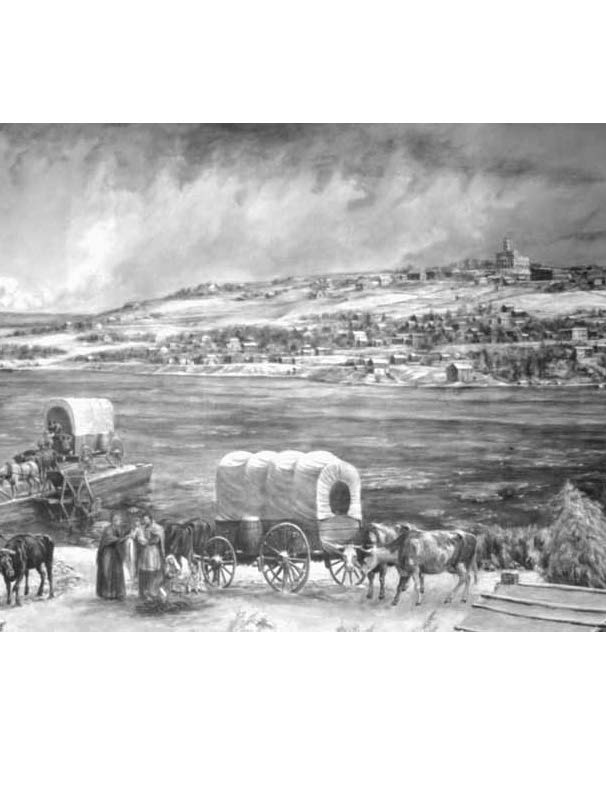

Mob action resumed and increased, forcing members of outlying Mormon settlements to flee to Nauvoo for refuge. The Nauvoo Charter was repealed by the state legislature, leaving the city without protection of city law. Mob forces, checked only in part by the state militia, threatened the destruction of the city unless the Mormons would leave. Agreements were made in the fall of 1845 between the Church and its enemies that allowed the Saints to leave the following spring. [15] Aggressive acts and harassment continued however, forcing a premature departure in the cold and snows of winter.

The first large group of Saints left their homes on 4 February 1846. Having ferried across the Mississippi River to Iowa, they gathered at Sugar Creek. [16] At this point of assembly, they organized for their journey across the plains. As weather conditions dictated, groups continued to cross the river on the ice and by ferry. Most left during the winter and spring and others during the summer. As fall approached, the only Latter-day Saints remaining in the city were the poor, the sick, the aged, and widows, along with their children. These, numbering nearly five hundred souls, had remained behind, awaiting the time when they could be picked up and assisted by their fellow Saints. Exodus of Church leaders along with the vast majority of members still failed to appease the mob. In September 1846, after overcoming a brief defense, the mobs drove the last of the Saints from their homes—away from their city and into the exposure of the open prairie.

Once again the people were exiles. This time their journey would eventually lead to the Great Basin of the Rocky Mountains near the Great Salt Lake. Here the industry that made Nauvoo would be put to work making the desert blossom. They would contribute a vital part in taming and colonizing the wilderness of the West. Nauvoo and its central structure, the temple, were to remain a silent symbol of the industry, faith, sacrifice, ideals, and dreams of its builders. As stated by historian B. H. Roberts, Nauvoo had enjoyed an adventurous career, “the most prosperous, but the briefest, and the saddest career of all American cities in modern times." [17]

Notes

[1] Thomas Ford, A History of Illinois (Chicago: Lakeside, 1946), 2:290. Ford lists the population at fifteen thousand. This figure may have been correct in February 1846 due to an influx of people from surrounding communities as refugees from persecution. During the summer and fall of 1845, as well as in early 1846, mobs drove families of Church members from their homes, burning houses, barns, and crops. These people fled to Nauvoo for safety. The most accurate figures on population are those compiled by Susan Easton Black, who concluded that the Ford figure was too high and that the population was probably eleven to twelve thousand. She compiled data “from over one thousand sources. . . . It acknowledges, highlights, and reconstructs the contribution and commitment of a total of 23,200 known people who were members of the Church at any time during the years from 1830 to 1848. A synthesis of all these noncensus data indicates that the population of Nauvoo grew from 100 in 1839 to about 4,000 in 1842, rose to about 12,000 in 1844, and stood at around 11,000 in 1845.” “How Large Was the Population of Nauvoo?” BYU Studies 35, no. 2 (1995): 93.

[2] Thomas Gregg, Missouri Republican, as quoted in David R. Crockett, Saints in the Wilderness (Tucson: LDS Gems, 1997), 186.

[3] J. R. Smith, a traveling artist and lecturer, as quoted by Glen M. Leonard and T. Edgar Lyon, “The Nauvoo Years,” Ensign, September 1979, 11.

[4] John Greenleaf Whittier, a famous poet and traveler, as quoted by William Mulder and A. Russell Mortensen, ed., Among the Mormons (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1973), 159.

[5] B. H. Roberts, A Comprehensive History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Salt Lake City: Deseret News, 1930), l:479.

[6] Gregg, History of Hancock County, Illinois (Chicago: C. C. Chapman, 1880), 2:245.

[7] Joseph Smith, History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, ed. B. H. Roberts, 2d ed., rev. (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1957), 3:375.

[8] Ibid., 4:239–49.

[9] Ibid., 4:178.

[10] Roberts, Comprehensive History, 2:84–85.

[11] Gustive O. Larson, Prelude to the Kingdom (Francestown, N. H.: M. Jones, 1947), 50; also, Richard L. Jensen, “Transplanted to Zion: The Impact of British Latter-day Saint Immigration upon Nauvoo,” BYU Studies 31, no. 1 (winter 1991): 78. He records that from 1840 to 1845 some 4,666 individuals came to Nauvoo from the British Isles.

[12] Kenneth Godfrey, “Causes of Mormon Non-Mormon Conflict in Hancock County, Illinois, 1839–1846” (Ph.D. diss., Brigham Young University, 1967). This dissertation presents a detailed survey of these conflicts; pages 112–44 are particularly insightful.

[13] Smith, History of the Church, 6:612–22.

[14] Roberts, Comprehensive History, 2:416–20.

[15] Ibid., 2:504–6.

[16] William E. Berrett and Alma P. Burton, Readings in LDS Church History from Original Manuscripts (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1955), 2:122–23.

[17] Roberts, Comprehensive History, 2:60.