Interior Features

Don F. Colvin, “Interior Features,” in Nauvoo Temple: A Story of Faith (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, 2002), 179–232.

Evidence concerning the building’s interior comes from a few architectural drawings, eyewitness descriptions, archeological evidence, and lists of materials in account books. Other than the Henry Lewis sketch of the baptismal font (Figure 4.1), there are no artist’s sketches or photographs of the temple’s interior available for analysis.

Evidence concerning the building’s interior comes from a few architectural drawings, eyewitness descriptions, archeological evidence, and lists of materials in account books. Other than the Henry Lewis sketch of the baptismal font (Figure 4.1), there are no artist’s sketches or photographs of the temple’s interior available for analysis.

Over the years uncertainty has existed regarding the extent of completion in various interior sections of the temple. Careful examination of each floor level and section of the building, along with consideration of all available evidence, will shed some light on this issue.

The Basement Story Work on the original basement excavation started in the fall of 1840. It was probably done by pick and shovel along with teams of oxen and scrapers to drag out the earth. Archaeological excavation shows that the cut into the earth was nearly vertical and that foundation or basement walls were laid against it except for a 30-foot space on the south side of the building, which is thought to “have been where the excavated earth was dragged or otherwise removed from the basement" [1] (see Figure 9.2).

Rooms

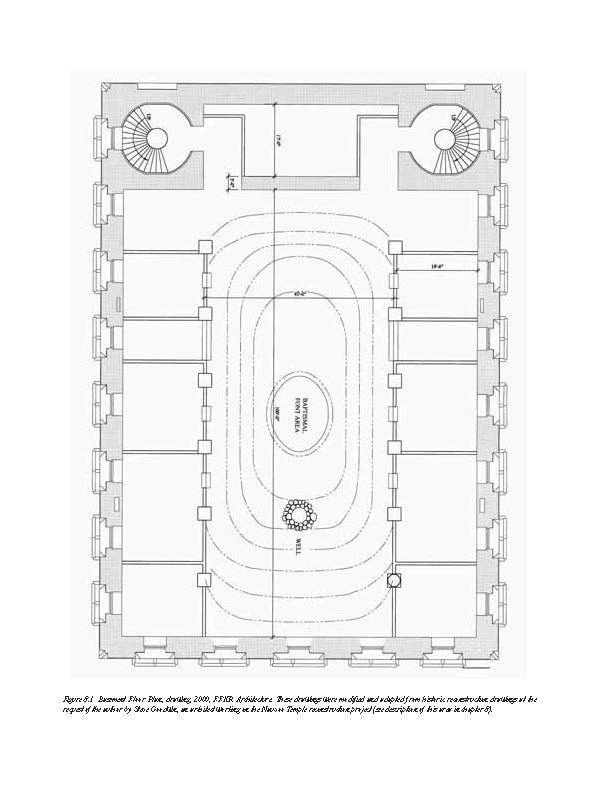

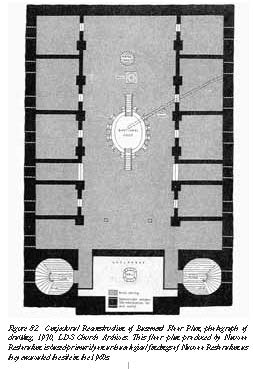

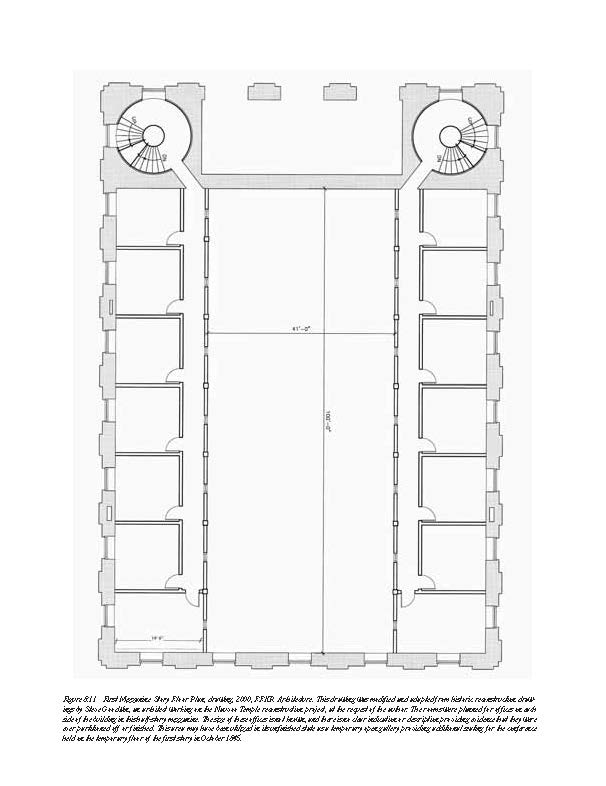

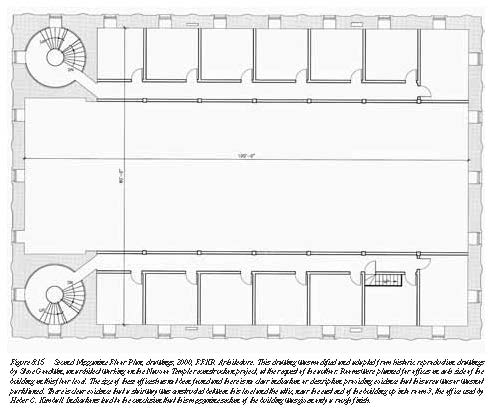

A letter from the Twelve Apostles to all Church members explained that “upon each side of the font there will be a suite of rooms fitted up for the washings." [2] Lyman O. Littlefield, a correspondent for the New-York Messenger, wrote that the basement “is divided off into thirteen rooms, the one in the centre is one hundred feet in length from east to west.” [3] There were six rooms along each side of the large main central room. Extending out from the walls and dividing the side rooms from each other were thick stone partitions that varied from 19 to 23 inches in thickness. [4] These heavy partitions provided additional strength to the outside walls and added support for floors above the basement. “The interior super structure was supported by 12 piers, 6 on each side, spaced at 15 foot intervals, center to center.” Each heavy stone “pier was 4 feet square, built on a subpier 8 feet square and approximately 4 feet deep.” [5] These piers provided the main support for beams, columns, and floors above the basement. They ran along each side of the large main room and had stone partitions running between them that separated the side rooms from the main hall. These side rooms were each 18 feet 6 inches wide but varied considerably in length. The last rooms on the west were open, lacking partitions separating them from the main hall (see Figures 8.1 and 8.2). The central room was 40 feet wide by 100 feet long. [6] Additional temporary rooms may have been curtained off on the east end of this main hall to provide more space for patrons changing clothes to participate in baptisms. [7]

A letter from the Twelve Apostles to all Church members explained that “upon each side of the font there will be a suite of rooms fitted up for the washings." [2] Lyman O. Littlefield, a correspondent for the New-York Messenger, wrote that the basement “is divided off into thirteen rooms, the one in the centre is one hundred feet in length from east to west.” [3] There were six rooms along each side of the large main central room. Extending out from the walls and dividing the side rooms from each other were thick stone partitions that varied from 19 to 23 inches in thickness. [4] These heavy partitions provided additional strength to the outside walls and added support for floors above the basement. “The interior super structure was supported by 12 piers, 6 on each side, spaced at 15 foot intervals, center to center.” Each heavy stone “pier was 4 feet square, built on a subpier 8 feet square and approximately 4 feet deep.” [5] These piers provided the main support for beams, columns, and floors above the basement. They ran along each side of the large main room and had stone partitions running between them that separated the side rooms from the main hall. These side rooms were each 18 feet 6 inches wide but varied considerably in length. The last rooms on the west were open, lacking partitions separating them from the main hall (see Figures 8.1 and 8.2). The central room was 40 feet wide by 100 feet long. [6] Additional temporary rooms may have been curtained off on the east end of this main hall to provide more space for patrons changing clothes to participate in baptisms. [7]

On the west end of the basement was the vestibule area. It was separated from the main hall by a 3-foot-thick stone wall that, except for two 6-foot-wide passageway exits, extended the full width of the basement. This heavy vestibule partition wall continued above the basement, through the first and second stories to the top of the stone walls. It provided stability to the building and direct support for the attic and steeple.

Access to the basement was through the stairwells and vestibule on the west end. It is logical to consider that another entrance may have been constructed on the east end or north side of the building, but there is no record of any kind to indicate that such existed.

The vestibule area was taken up by one large room or area about 16 or 17 feet wide by 30 to 32 feet long. From all available evidence, this area was walled off by a wooden partition with no doors or access into it. [8] This area seems never to have been developed or utilized. On each corner of the west end were stairwells with stairs providing access to each level of the building. “The stairwells were not true circles, as expected, but each was 16 feet east to west and 17 feet north to south. Rather than their perimeters being a continuous curve, there was a flattened space on each of the four sides, one of which was the entrance to the passageway” [9] (see Figures 8.1 and 8.2). These stairwells at their base opened toward the center of the vestibule area into a 6-foot-wide open hallway or passageway that then led east into the large main basement room. The entire vestibule area and stairwells can be seen in Figure 8.1.

All rooms of the basement were used extensively. In the baptismal font—both the earlier wooden and later stone font—thousands of ordinances were performed. Rooms on the sides were used as dressing rooms for patrons utilizing the font. Additional rooms were used by clerks appointed to keep records of all ordinances performed. Others were no doubt used for confirmation ordinances. The open side rooms on the north and south sides may have been used by the recording clerks or as a reception area for patrons waiting their turn to participate in the ordinances. There is no record available to indicate that any parts of the endowment ordinances were conducted in this part of the building.

Dimensions

The total inner dimensions of the basement area were the same as those of the first and second stories above. All are found to be 80 feet wide by 120 feet in length. [10] By adding the breadth of the 40- foot-wide main room in the basement plus a room on each side of 18 feet 6 inches, along with stone partitions on each side of 18 inches, we come to an overall width of 80 feet. The main hall was 100 feet long and had on its west end a 3-foot-thick wall, and beyond this the vestibule and stair wells were 16 or 17 feet wide. Adding these together, we come to a total interior length of 120 feet. The overall layout of the basement story floor plan can be seen in Figure 8.1.

The total inner dimensions of the basement area were the same as those of the first and second stories above. All are found to be 80 feet wide by 120 feet in length. [10] By adding the breadth of the 40- foot-wide main room in the basement plus a room on each side of 18 feet 6 inches, along with stone partitions on each side of 18 inches, we come to an overall width of 80 feet. The main hall was 100 feet long and had on its west end a 3-foot-thick wall, and beyond this the vestibule and stair wells were 16 or 17 feet wide. Adding these together, we come to a total interior length of 120 feet. The overall layout of the basement story floor plan can be seen in Figure 8.1.

The walls of the building in the basement area were either 4 feet 5 inches or 5 feet in thickness (see Figure 9.2). [11] They were composed of large irregular blocks of stone laid directly on the clay floor of the excavation, without footings, and cemented together with lime mortar. [12] The total outside dimensions in this area could very likely have been 90 feet wide by 130 feet in length. [13]

Depth

The sides and ends of the basement floor level were 5 or more feet below ground level. [14] Excavation of the temple site revealed that in the center of the basement where the baptismal font was located, the floor level was deeper. Here it ranged from 3 feet 3 inches to 4 feet 2 inches below the level of the outside walls (see Figure 9.1). It is not certain when this change of depth in the basement was implemented; it may have been done partially or even totally as the wooden font was constructed. Available evidence, however, leans in favor of this change being done at a later date. [15] Without question, the increased depth added to the basement floor level was done to accommodate the need for more headroom above the font. The wooden font was 7 feet high. [16] Without this change, headroom would have been at most only 5 feet from the rim of the font to the ceiling. [17] The stone font, which stood either 7 feet 7 inches or 8 feet high, would have had even more severe problems. [18] Without this change, headroom of the stone font would have been at most only 4 feet above the rim of the font. The entire basement area was scooped out to accommodate those working in the font and was inclined down to the center. Rooms on the sides were affected less than the main room. They were sloped 4 to 6 inches down from the outside wall to the inner partition wall. The large interior room was sloped down from 3 feet 3 inches on each end and 2 feet 9 inches on each side to the font at the center of the room. These grade levels can be examined by study of Figure 9.1. Steps were placed at the entrances of side rooms to lessen the slope of the grade on each side of the main room, as can be noted in Figure 8.2. Figure 9.3 shows how these steps were constructed. The problem of inadequate headroom may have been why Truman O. Angell felt that the temple committee had “much botched” some aspects of the basement area. [19] The committee had the walls in place in April before they made a decision in July to build the font. Since it was then impractical to start over, they must have opted to incline the floor to pick up additional height.

The Baptismal Font

Dominating the central hall of the basement was the baptismal font. It was placed beneath ground level by direct command of the Lord “to be immersed in the water and come forth out of the water is in the likeness of the resurrection of the dead in coming forth out of their graves. . . . Consequently, the baptismal font was instituted as a similitude of the grave, and was commanded to be in a place underneath where the living are wont to assemble, to show forth the living and the dead, and that all things may have their likeness” (D&C 128:12–13; see also Rom. 6:3–5).

There were really two fonts used in the temple, the original wooden one and its replacement, a permanent font made of stone. Both were located in the same spot. Joseph Smith provided a detailed description of this temporary wooden font:

The baptismal font is situated in the center of the basement room, under the main hall of the Temple; it is constructed of pine timber, and put together of staves tongued and grooved, oval shaped, sixteen feet long east and west, and twelve feet wide, seven feet high from the foundation, the basin four feet deep, the moulding of the cap and base are formed of beautiful carved work in antique style. The sides are finished with panel work. A flight of stairs in the north and south sides lead up and down into the basin, guarded by side railing.

The font stands upon twelve oxen, four on each side, and two at each end, their heads, shoulders, and fore legs projecting out from under the font; they are carved out of pine plank, glued together, and copied after the most beautiful five-year-old steer that could be found in the country, and they are an excellent striking likeness of the original; the horns were formed after the most perfect horn that could be procured.

The font was enclosed by a temporary frame building sided up with split oak clapboards, with a roof of the same material, and was so low that the timbers of the first story were laid above it. [20]

An observer pointed out that the carved wooden oxen were “so perfectly cut out of timber,” and looked so similar as to cause visitors “to look with surprize, resembling the living animal." [21] Another, commenting on the joining work, said that it was done with “a fidelity and perfection of detail difficult to surpass." [22] The oxen “were painted as white as snow." [23] It is reported that panels on the sides under the surface of the basin had “various scenes, handsomely painted." [24]

Though the decision to replace the wooden font was made during the winter of 1843, it was not until 15 January 1845 that a formal announcement was made to members of the Church. They were then informed that “as soon as the stone cutters get through with the cutting of the stone for the walls of the Temple, they will immediately proceed to cut the stone for and erect a font of hewn stone." [25] Stonecutters and carvers worked steadily, and by the end of June, Brigham Young was able to announce that “the new stone font is mostly cut.” At 4 p.m. on 27 June “the first stone was laid,” and it was expected that “in about five or six weeks . . . the font will be all finished." [26] President Young declared in July 1845: “We have taken down the wooden fount that was built.” He went on to explain that Joseph Smith had said to him, “We will build a wooden font to serve the present necessity.” It is also evident that some very real problems had developed with this temporary font in trying to keep it clean. As President Young explained, “we will have a fount that will not stink and keep us all the while cleansing it out." [27] On 20 August it was observed that the new font was “in an advanced state of completion." [28]

Though the decision to replace the wooden font was made during the winter of 1843, it was not until 15 January 1845 that a formal announcement was made to members of the Church. They were then informed that “as soon as the stone cutters get through with the cutting of the stone for the walls of the Temple, they will immediately proceed to cut the stone for and erect a font of hewn stone." [25] Stonecutters and carvers worked steadily, and by the end of June, Brigham Young was able to announce that “the new stone font is mostly cut.” At 4 p.m. on 27 June “the first stone was laid,” and it was expected that “in about five or six weeks . . . the font will be all finished." [26] President Young declared in July 1845: “We have taken down the wooden fount that was built.” He went on to explain that Joseph Smith had said to him, “We will build a wooden font to serve the present necessity.” It is also evident that some very real problems had developed with this temporary font in trying to keep it clean. As President Young explained, “we will have a fount that will not stink and keep us all the while cleansing it out." [27] On 20 August it was observed that the new font was “in an advanced state of completion." [28]

Visitors viewing the stone font might conclude that the stone oxen supported the font basin resting upon their backs, but this was not the case (see Figure 9.4). The stone basin “rested on a foundation of its own, composed of the heavy blocks of stone closely joined together and fashioned in the form of a circle. The oxen were not fully developed but resting on their forefeet, the middle of their bodies was firmly cemented to that circular foundation and thus the basin seemed to rest on their backs." [29] The oxen were further secured in position by having their front feet cemented in place by “Roman cement." [30]

Visitors viewing the stone font might conclude that the stone oxen supported the font basin resting upon their backs, but this was not the case (see Figure 9.4). The stone basin “rested on a foundation of its own, composed of the heavy blocks of stone closely joined together and fashioned in the form of a circle. The oxen were not fully developed but resting on their forefeet, the middle of their bodies was firmly cemented to that circular foundation and thus the basin seemed to rest on their backs." [29] The oxen were further secured in position by having their front feet cemented in place by “Roman cement." [30]

The architectural drawings of William Weeks indicate that the stone font was designed to stand upon an oval-shaped stone base 12 feet long by 8 feet wide. [31] There is, however, substantial evidence to indicate that changes were made during construction to increase the base size by 3 feet in each direction to dimensions of 15 feet long by 11½ feet wide. [32] Following these proportions, the stone font basin above this base had an outside dimension of 18 feet 5½ inches by 14 feet 3½ inches (see Figure 12.3). The depth of the font basin is difficult to determine. It could have been 3 feet 7 inches deep, as indicated by the architect’s drawings. This is a shallow basin and if the width and length were altered, then it is very possible that some depth may have been added in the stone basin. The overall height of the font was 7 feet 7 inches. [33] It could have been even taller if changes were added. A circular iron railing around the font added beauty and served the purpose of keeping the curious away from the oxen and font itself. [34]

Access to the font was provided by “a flight of stone steps with iron railing on each side [that] led up to the font and a similar flight on the other side descended therefrom" [35] (see the Henry Lewis Sketch of the font in Figure 5.2, as well as the reconstruction drawings, Figure 12.4). Littlefield explained that “the fount will be entered by a flight of steps in an arch form at each end." [36] In contrast to the earlier wooden font, the stone replacement had its stairs located on the east and west ends of the oval basin. [37] Each of the stone steps leading up to the font had a 9-inch rise with an 11-inch tread. [38] Remains of these steps were found during the archaeological excavation and can be examined in Figure 9.6. One end piece of a stair tread contained two sockets that showed a baluster spacing of 5½ inches. [39] The steps down into the font were carved into the bowl itself on both ends of the stone basin. They consisted of three steps on each end, having a 10-inch rise for each step with an 8-inch tread (see Figures 4.3 and 12.4).

The basement level where the font stood, as well as the area close around it, was level. “To the east and west of the font the slope rises only 6 inches in the first 10 feet presumably to the bottom of the font stairs, and then goes up more steeply to reach a level of 2.9 feet above the center to the west, at the vestibule wall, and 3.3 feet at the east wall." [40]

The oxen were each carved from solid blocks of stone. [41] William W. Player was called upon to supervise the construction of the font, and a master stone carver (as yet unidentified) was engaged to guide the creative hands of workers carving the oxen. The challenge of the stone carvers was to create from solid blocks of stone twelve identical oxen about the size of living natural animals and to duplicate the wooden oxen that preceded them. From the reports of most observers, they were successful in their task.

The editor of the Hancock Eagle, somewhat startled when first viewing the baptismal font, declared that "the beholder is lost in wonder at the magnitude of the design and the extraordinary amount of labor that must have been expended in the direction of the work." [42] Upon viewing the work, Charles Lanman described the "Baptismal Font, supported by twelve oxen, large as life, the whole executed in solid stone." [43] Emily Austin described the "oxen of white lime stone, very natural, and twelve in number, all perfectly executed, so that the veins in the ears and nose were plainly seen. The horns were perfectly natural, with small wrinkles at the bottom." [44] According to the Lewis sketch and other descriptions, there were four oxen on each side of the font and two at each end. [45] Another observer explained that the oxen “were well executed and with their bright eyes of glass and well formed ears, looked exceedingly life like and altogether presented a very handsome appearance." [46] The "oxen [had] tin horns and tin ears." [47] The ends of the horns were tipped with a metal resembling gold. [48] There were negative reports and critical observations, but most observers were pleased with the oxen and stone baptismal font.

It was decided on 15 March 1845 to “build a drain for the font." [49] Evidence confirming the existence of this drain was uncovered during the archeological excavation (see Figure 9.8). They found that “the drain was constructed of large slabs of stone, laid without mortar, to make a channel roughly 12 inches square. . . . It runs from the east end of the font in a southeasterly direction . . . then under the south wall in the direction of the ravine south of Mulholland Street. . . . The bottom of the drain channel is 9 feet below the existing ground level. . . . When the drain was first uncovered in 1962 a plumber’s flexible rod was able to probe 35 feet to the southeast." [50]

Water Supply

Joseph Smith explained that water for the font “was supplied from a well thirty feet deep in the east end of the basement." [51] The well was apparently dug early in the construction of the temple by Hiram Oaks and Jess McCarrol. Hiram Oaks’s granddaughter described the project: “They had to penetrate through ten feet of solid rock before they struck water. When they struck water, they lost the drill and water spirited up with great force. Grandfather put his hat over the hole until Jess could get a block of wood to stop the water." [52] This deep well with its reliable flow of water seems to have supplied the baptismal font adequately as well as all other needs of the temple. Designated by Nauvoo Restoration as Well B, this traditional well can be viewed much as it existed during 1846 in Figure 9.7. It was lined with stone and probably fitted with a pump to draw water for its various uses.

Water from the well was quite cold, so “arrangements were made to heat the rooms and the water in the baptismal font." [53] When ordinance work was being conducted, priesthood assignments were issued and men “were appointed to see to the fires." [54]

An additional well came to public attention during the occupation of the temple by mob forces in September 1846. A newspaper correspondent reported: “On Saturday, there was quite an excitement in the camp and the city, created by the discovery of a dry well under the floor of the portico of the Temple, about fifteen feet deep, and situated in a room to which there was no entrance except by an opening made in the floor; there were various surmises as to the purpose for which it had been made, but the most reasonable one is, that it had been used as a cistern whilst the temple was being built." [55]

This abandoned shallow well was rediscovered during archaeological excavations of the temple site in 1969. [56] An ordinary stone-lined well that was apparently dry during most of the year, it was walled off and never put to use. When and why it was dug, and for what purpose, remains unanswered. It may have been used as a drainage well to take water from the font before the southeasterly underground drain was built. If this is true, then it may be that this drainage well could not percolate the water away fast enough, and it became necessary to build the permanent drain.

During site excavation a 7-foot-wide square of brick paving was discovered near the east end of the basement (see Figure 8.4). Archaeologists believe that a water tank or boiler stood on this spot. This tank may have been utilized for storing water, or it may have been connected to a water heating device for the font. [57]

The Basement Floor

This area of the temple was not completed until the spring of 1846. Some type of temporary walkway or flooring was likely put in place for patrons utilizing the wooden baptismal font and dressing rooms. If this were not the case, they would have had to walk on the slippery clay floor of the basement, which would have been hazardous and dirty. A reporter who toured the temple in August 1845 found that the basement “floor was not yet paved, which I was informed however would be shortly done." [58] Another observer reported on 29 December 1845 that the basement floor was almost finished. [59] William Mendenhall recorded in his journal that he was laying brick in the temple in late March and early April 1846. [60] His effort may have been to assist in finishing the main floor or laying brick wall bases in side rooms in preparation for the temple’s dedication. An eyewitness who visited the temple shortly after the dedication in May 1846 was pleased “to perceive how much had been accomplished in a month. The appearance of the basement hall has been entirely changed by a laborious use of the trowel.” He described that the “animals” now showed to great advantage “in contact with the tiled floor” that had apparently just been laid. This observer went on to declare that “the basement floor is now considered finished." [61] Charles Lanman, who toured the temple during the summer of 1846, described the font as located “in the basement room, which is paved with brick, and converges to the centre." [62] Also in the summer of 1846, Hiram G. Ferris commented on the basement: “The floor of this room is made of brick and has a gradual descent from the sides and ends [to] the font." [63]

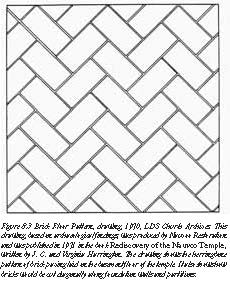

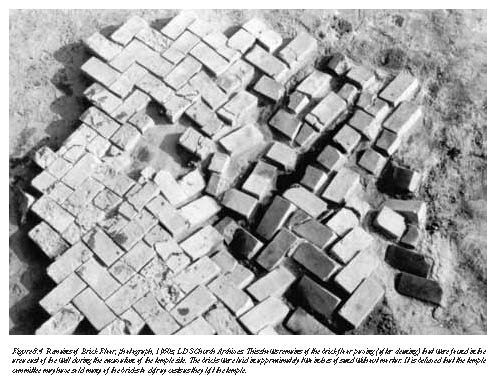

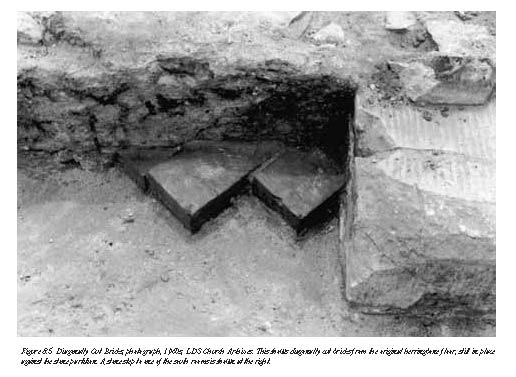

When the temple site was excavated in 1968, considerable evidence was found to confirm that most, if not all, of the basement area had been covered with about two inches of clean sand, and the sand then covered with “specially selected brick, larger than usually found in Nauvoo buildings of the period, and of a uniform red color.” Of some one hundred whole bricks, “over three-fourths of the bricks measured 9 [inches long] by 4¼ [inches wide] and 2_ inches [thick]." [64] The bricks were laid in a herringbone pattern as shown in Figures 8.3 and 8.4. There is strong evidence indicating that the sand layer and red brick paving were put in place between the late fall of 1845 and the dedication in the spring of 1846. [65]

Windows

The basement was illuminated by twenty-one windows, eight on each side and five on the east end. [66] Some artists’ sketches and paintings show two more basement windows at the front of the building, one on either side of the entrance steps. Architectural drawings plus photographic evidence in the 1865 Tintype (see Figure 11.3) clearly show that there were no basement windows on the front (west) end of the building. All basement windows were formed in a half circle described to be “about 5 feet high and as many wide." [67] A more accurate identification of the size of these windows, derived from a study of the architectural drawings and daguerreotypes, would be 4 feet 10 inches wide (same as windows in the walls above them) and about 3 feet 11 inches high. They matched the large windows in a direct line above them. A reporter by the name of Hiram Ferris described rooms in the basement, observing: “these small rooms on the sides are lighted by windows in the shape of an oblong semi-circle." [68] These windows were composed of several panes of glass in a fanlike pattern with what seems to be a row of upright window panes at the bottom (see Figure 6.12). “The lower sash probably opened in hopper fashion to ventilate the basement." [69]

Doors

It is apparent that some rooms on each side of the basement were fitted with doors. A visitor described these rooms “all with doors from within." [70] Another observer declared that each room “has one door opening into the large, or central room. But the end room [the walled off, enclosed area, under the front vestibule] has neither any visible door or window. It is directly under the entrance." [71]

Overall Extent of Completion

The basement area of the temple was probably used more extensively than any other portion of the building. Baptisms for the dead were conducted here beginning on 21 November 1841. [72] These ordinances took place in the wooden font and later in the stone font. Though the stone font was not totally finished by the winter of 1845–46, it was nevertheless considered usable. Baptisms for the dead were regularly conducted there in December 1845 [73] and continued until ordinance work ceased on 7 February 1846. It was recorded that 15,626 baptisms for the dead were completed in Nauvoo, almost all of which were done in the temple. [74] The font was completely finished prior to the dedication of the building in the spring of 1846. The basement area was used regularly by the police, who held meetings to regulate assignments for guarding the temple and other sites in Nauvoo. [75] During the summer of 1845 it was observed that the basement was temporarily used as a storage area. “Large piles of ornamental carpenter work is heaped in different parts of the room designed for the finishing of different parts of the Temple. Curious devices or emblems are wrought or carved upon many of the different pieces." [76]

Excavation of the temple site revealed that plaster was “found in place on several of the basement piers and partition remains." [77] Prevailing archaeological evidence indicates that the stone walls in the basement were plastered. There is no physical evidence to indicate whether or not these walls were painted. In the winter of 1846 several purchases of white lead, linseed oil, turpentine, and even “shelack” (shellac) were made for the temple. Some of this may have been for the windows, but some may also have been for areas of the basement. This wintertime purchase of paint was probably not used on the first or second stories, since at the time neither story was far enough along in completion. It is also possible that the basement walls were covered with lime whitewash. [78] As previously noted, doors and windows had been finished and used in this area of the building. There is also no question that the stone baptismal font had been finished and used prior to the exodus. No record is found of any permanent seating in basement rooms. It is assumed that benches, chairs, and stools were placed in the rooms or brought in by patrons.

Excavation of the temple site revealed that plaster was “found in place on several of the basement piers and partition remains." [77] Prevailing archaeological evidence indicates that the stone walls in the basement were plastered. There is no physical evidence to indicate whether or not these walls were painted. In the winter of 1846 several purchases of white lead, linseed oil, turpentine, and even “shelack” (shellac) were made for the temple. Some of this may have been for the windows, but some may also have been for areas of the basement. This wintertime purchase of paint was probably not used on the first or second stories, since at the time neither story was far enough along in completion. It is also possible that the basement walls were covered with lime whitewash. [78] As previously noted, doors and windows had been finished and used in this area of the building. There is also no question that the stone baptismal font had been finished and used prior to the exodus. No record is found of any permanent seating in basement rooms. It is assumed that benches, chairs, and stools were placed in the rooms or brought in by patrons.

Some questions have been raised relative to the completion of the basement floor. The only area of the basement that may have been left unfinished was the floor. Buckingham, who visited the temple in 1847, described the basement as unpaved. [79] His observation is in direct conflict with reports cited above that this area of the temple was paved with brick. Those who excavated the temple site in 1968 reported “it seems safe to conclude that brick paving was planned for the entire basement area, and had probably been laid in most if not all the rooms." [80] It is now evident that when Buckingham visited the building in 1847 the brick paving in existence in 1846 had been carried away. Since the bricks were laid in sand and not set in mortar, they could be removed easily. Because funds were scarce, it is possible that the temple committee had these bricks taken up following the temple's dedication. They may have been sold to purchase badly needed supplies for the western exodus. It is also possible that local citizens appropriated them for construction purposes.

Some questions have been raised relative to the completion of the basement floor. The only area of the basement that may have been left unfinished was the floor. Buckingham, who visited the temple in 1847, described the basement as unpaved. [79] His observation is in direct conflict with reports cited above that this area of the temple was paved with brick. Those who excavated the temple site in 1968 reported “it seems safe to conclude that brick paving was planned for the entire basement area, and had probably been laid in most if not all the rooms." [80] It is now evident that when Buckingham visited the building in 1847 the brick paving in existence in 1846 had been carried away. Since the bricks were laid in sand and not set in mortar, they could be removed easily. Because funds were scarce, it is possible that the temple committee had these bricks taken up following the temple's dedication. They may have been sold to purchase badly needed supplies for the western exodus. It is also possible that local citizens appropriated them for construction purposes.

Had the Saints remained in Nauvoo, some additional finer finish may have been added to the basement area. There is, however, clear evidence to indicate that this area of the temple was completed, functional, and heavily utilized. This is confirmed by the report of John Taylor in the summer of 1846, when he declared that “the basement story of the temple is finished." [81]

The First Story

The first story could properly be called the main floor of the temple. It was here that general conferences and other important Church meetings were held. This was also the place where the formal dedication services were conducted.

The Front Vestibule

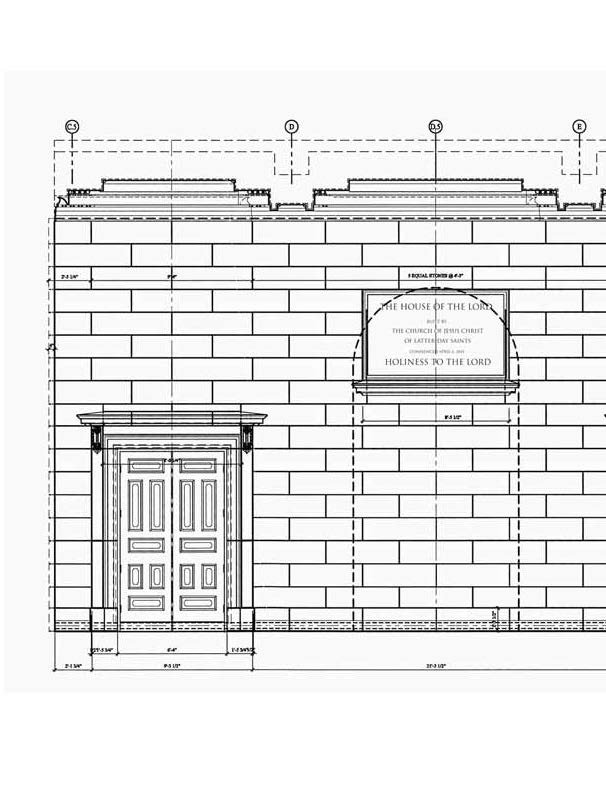

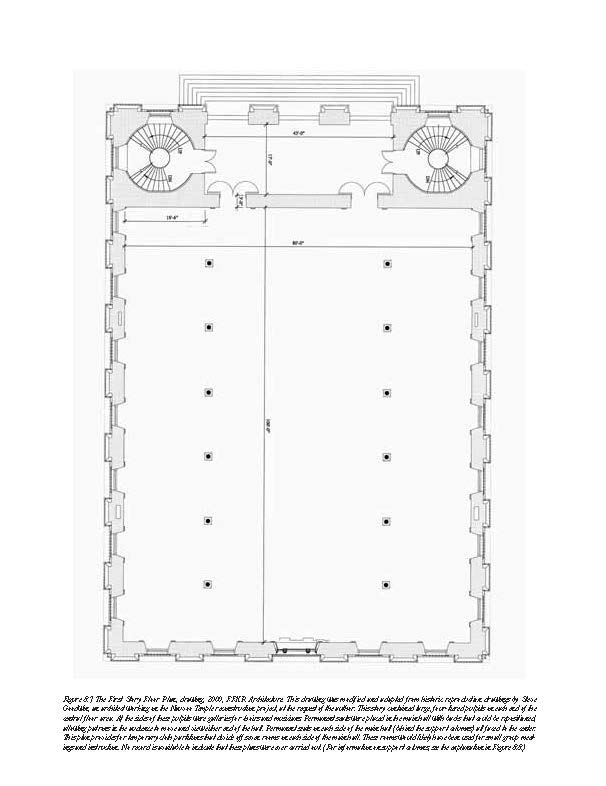

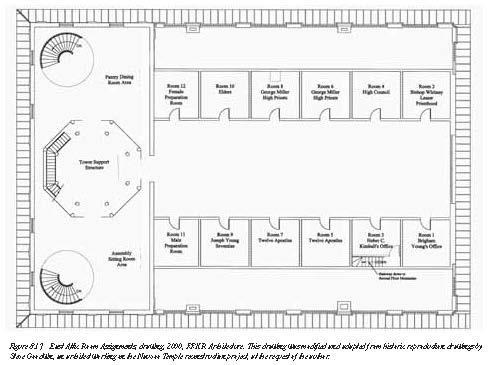

Entrance from outside the temple was gained by climbing a flight of ten steps. As Littlefield entered the building in 1845, he left this observation: “Now let us examine what is properly called the first story. . . . We enter this at the west end, passing through either of three large open doors or arched pass-ways, each of which is nine feet seven inches wide and twenty one feet high. Passing through these we are standing in a large outer court, forty-three feet by seventeen feet wide." [82] The area from the floor to the ceiling was 25 feet in height, identical to the main interior area of the first story (see Figure 7.1). On each end of this 43-foot-long outer lobby were stairwells, each 17 feet deep and 18 feet 6 inches long. These areas were separated from the open court by stone partition walls. Each wall had doors that opened into the large spiral staircases. Adding together the spacious outer court along with the stairwells on each side (43 feet plus 18½ and 18½) results in a total interior width dimension of 80 feet (see drawing of the first story floor plan and vestibule area, Figure 8.7).

Upon entering the vestibule, one’s attention was quickly drawn to the dedication plaque centered high on the interior wall (see Figure 8.6). It reads the same as its larger duplicate located on the outside of the front attic.

The House of the Lord

Built by

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

Commenced April 6, 1841.

Holiness to the Lord

No account has been found to describe the floor of this open exposed vestibule area. There is some evidence and good reason to conclude that it was a stone floor. Temple committee records show entries for flagging stones being produced in large quantity. [83] These flagging stones were likely about 4 inches thick and could have been laid over wooden beams. In this open, exposed area, this flagstone-type flooring would certainly have offered much greater protection from the elements than a wooden floor.

The Spiral Staircases

Enclosed within the solid stone stairwells “were winding stairs which led from one story to another until the top of the building was reached." [84] These stairs were built of wood in a spiral fashion. Fortunately, five drawings made by the architect have been preserved, furnishing a rather clear picture of these spiral staircases. To design and build such stairs was a significant engineering achievement. The architectural drawings clearly show that each step had a rise of 7" inches. As indicated by the drawings, there were thirteen risers or steps from the basement to the level of the first floor, a total rise of 11 feet 8 inches. The drawings show twenty-seven risers or steps from the first floor level to the first mezzanine, a total rise of 17 feet 1 inch. The heights for each of these areas are consistent with other architectural plans or drawings as well as the photographic evidence available for study. Detailed drawings of the stairs above the first mezzanine are not available. Both spiral staircases were well lighted, especially in the daytime, by the large windows as well as the circular windows located in the corners of the building. The spiral stairs left an open well area 6 feet in diameter at the middle of each spiral stair. [85] This may have been used as a location for a winch and pulley system to aid in getting firewood, coal, and water up to the level of the attic. A large amount of stove coal was purchased, as evidenced by entries found in the Building Committee account books.” This also is supported by the description of George Washington Bean, who explained: “I worked in the outer court of the Temple running a windlass, drawing up the wood and water needed to carry on the endowments." [86] If so used, it was probably the north stairwell that was utilized for this purpose.

Enclosed within the solid stone stairwells “were winding stairs which led from one story to another until the top of the building was reached." [84] These stairs were built of wood in a spiral fashion. Fortunately, five drawings made by the architect have been preserved, furnishing a rather clear picture of these spiral staircases. To design and build such stairs was a significant engineering achievement. The architectural drawings clearly show that each step had a rise of 7" inches. As indicated by the drawings, there were thirteen risers or steps from the basement to the level of the first floor, a total rise of 11 feet 8 inches. The drawings show twenty-seven risers or steps from the first floor level to the first mezzanine, a total rise of 17 feet 1 inch. The heights for each of these areas are consistent with other architectural plans or drawings as well as the photographic evidence available for study. Detailed drawings of the stairs above the first mezzanine are not available. Both spiral staircases were well lighted, especially in the daytime, by the large windows as well as the circular windows located in the corners of the building. The spiral stairs left an open well area 6 feet in diameter at the middle of each spiral stair. [85] This may have been used as a location for a winch and pulley system to aid in getting firewood, coal, and water up to the level of the attic. A large amount of stove coal was purchased, as evidenced by entries found in the Building Committee account books.” This also is supported by the description of George Washington Bean, who explained: “I worked in the outer court of the Temple running a windlass, drawing up the wood and water needed to carry on the endowments." [86] If so used, it was probably the north stairwell that was utilized for this purpose.

Stairs in the southwest stairwell were considered finished and used extensively by patrons who came for their temple ordinances. The stairs on the northwest stairwell were used consistently by workers during construction, but evidence indicates that these stairs had only a rough finish. Joseph Smith III, who visited the temple on several occasions, claimed that “the stairway in the northwest corner was not finished. Rough inch boards [steps] were laid over the risers so that the workmen could pass up and down." [87] Account books indicate that some hardwood was used in finishing the temple. There are purchases for cherry wood, oak, and walnut. [88] Some cherry wood was used for doorsills, but no other indication is given as to where these types of wood were used. [89] It is very possible that some hardwood was utilized in the stairs. Archaeological excavation found in the charred fragments “of the north stairwell, a small piece of walnut, possibly from the steps or handrail." [90]

The Main First-Floor Area

The large assembly hall of the first story was entered by the main entrance on the west end through one of two large doors coming off the outer court. This story was planned to be divided into fifteen rooms. The large room running through the center was 100 feet long from east to west and 50 feet wide. [91] The fourteen rooms on the sides of this main hall (seven on each side) were never permanently partitioned. There is also no record of any division into various-sized rooms by the planned temporary cloth partitions. [92] If such a division were to have taken place, the most common dimension of these rooms would probably have been 15 feet by 15 feet.

The overall dimensions of the first floor are easily determined. Architect’s drawings provide a cross-sectional drawing with an arched central ceiling over the main hall of 40 feet 9 inches (see Figure 7.1). On each side of this arched ceiling there were six support posts 12 inches in diameter, each of which was sheathed with twenty fluted staves, making them into rounded 18-inch-diameter columns. Beyond these support columns on each side of the building was an area 18 feet 6 inches in width (see Figure 8.7). Adding these figures together brings an internal width of 80 feet. Overall internal length of the first story was 120 feet: 100 feet in the main hall plus a 3-foot-thick dividing wall between the main assembly hall and the vestibule plus a 17-foot outer court vestibule or portico area. This area can be examined by study of the first-story floor plan (Figure 8.7).

The permanent wood floor was finished or put in place by New Year’s Day of 1846. [93] No written descriptions of this floor have been provided. There is a possibility that the finished flooring was laid over the top of a rough subfloor, or it may have been only a finished 1- to 2-inch tongue-and-groove floor (1-inch thickness was common in other Nauvoo buildings). Support for the floor was provided by heavy stone columns or piers in the basement (see Figures 9.1 and 9.2). There were six of these 4-foot-square columns on each side of the basement, each set at 19 feet from the outside walls. Over the center of these columns were six heavy timber beams running the whole width of the temple, which were set on 15-foot centers. These heavy 12-inch-diameter pine timbers or beams were anchored or inset 16 inches into the stone walls of the temple (see Figure 7.1). The timbers may have been one long pole or beam 82 to 83 feet long but more likely were sectioned into three pieces, with the middle section being fit into place having a beveled edge, as shown in Jackson’s drawing (see Figure 8.13). These beveled endpieces would likely have been nailed or bolted together by strong boards on one or both sides of the beam at the joint area. Between these timbers, floor joists were placed on 14-inch centers to provide stability and support for the flooring placed upon them. In all likelihood these floor joists were 3-by-12-inch boards, approximately 14 or 15 feet in length. A drawing showing this type of floor joists can be viewed by examination of the fragment showing some of the south stairwell (see Figure 7.10). Billing records also support these measurements.

As the temple neared completion, permanent bench seats were installed in the center hall and along each side. Buckingham reported that in the “grand hall” of the first floor “seats are provided in this hall . . . and they are arranged with backs, which are fitted like the backs to seats in a modern railroad car, so as to allow the spectator to sit and look in either direction, east or west." [94] Another observer reported that the benches in the central hall under the arch were “constructed with backs that turn either way so as to admit of the audience being seated facing either end of the room." [95] One additional witness who toured the building declared: “The benches under the arch face each other in pairs.” He then added: “Those at the sides all face the center." [96] No reliable figures are available on the seating capacity of the first story. Some attendance figures were reported for the October conference of 1845, but these seem to be inflated. [97]

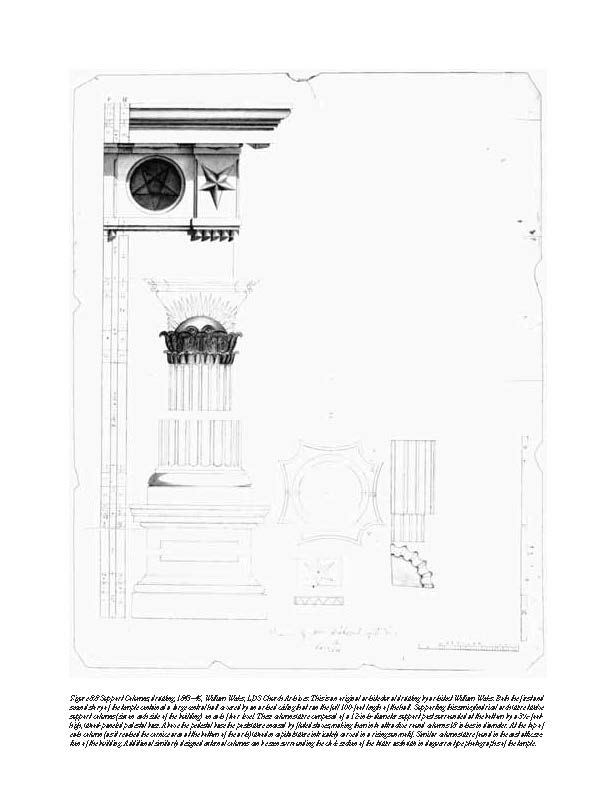

The first story of the Nauvoo Temple had “a large arch over its entire length." [98] Supporting this semicylindrical arch and the second floor above were twelve posts of round timber, each 12 inches in diameter. There were six of these posts on each side. The support posts were 24 feet in length rising from the level of the first floor to the bottom of the sleeper under the long timber beams supporting the second floor (see architect’s sketch of this area in Figure 7.1). Where exposed to view, each post was covered to 3½ feet by an ornamental wood-paneled pedestal. Above this pedestal each post was encased by fluted staves, making attractive columns. These round columns, each 18 inches in diameter, rose above the pedestals to the bottom of the first mezzanine.

The first story of the Nauvoo Temple had “a large arch over its entire length." [98] Supporting this semicylindrical arch and the second floor above were twelve posts of round timber, each 12 inches in diameter. There were six of these posts on each side. The support posts were 24 feet in length rising from the level of the first floor to the bottom of the sleeper under the long timber beams supporting the second floor (see architect’s sketch of this area in Figure 7.1). Where exposed to view, each post was covered to 3½ feet by an ornamental wood-paneled pedestal. Above this pedestal each post was encased by fluted staves, making attractive columns. These round columns, each 18 inches in diameter, rose above the pedestals to the bottom of the first mezzanine.

As noted by Tim Maxwell, an architect working on the Nauvoo Temple reconstruction project, “240 tapered staves 11 feet long are listed in the carpentry shop records. Also listed are 330 15-inch-long staves, evidently for carving the capitals. The number 330 is consistent when it is considered that one capital consisting of 30 staves may have been carved as a pattern prior to the 330 in the list. The 20 long staves and 30 short staves, when assembled in circles of the size pieces listed, both perfectly surround a 12 inch center. These dimensions and arrangement also confirm the fluted column and half sun-face capital found in William Weeks’ drawing that in the past was dismissed as only early discarded studies by Weeks." [99]

As noted by Tim Maxwell, an architect working on the Nauvoo Temple reconstruction project, “240 tapered staves 11 feet long are listed in the carpentry shop records. Also listed are 330 15-inch-long staves, evidently for carving the capitals. The number 330 is consistent when it is considered that one capital consisting of 30 staves may have been carved as a pattern prior to the 330 in the list. The 20 long staves and 30 short staves, when assembled in circles of the size pieces listed, both perfectly surround a 12 inch center. These dimensions and arrangement also confirm the fluted column and half sun-face capital found in William Weeks’ drawing that in the past was dismissed as only early discarded studies by Weeks." [99]

The columns supported an entablature and cornice running along the inner base of the arch. The entablature, frieze, cornice, soffits, and support columns were all places for special finish. Building records indicate considerable detailed wood carving and ornamentation in these areas. Ceilings on the sides under the mezzanines were flat.

Plans were made to subdivide the whole floor of the main hall by the use of “three great veils of rich crimson drapery." [100] These were to be suspended overhead from the ceiling and lowered into place when the occasion determined such a division. However, no record has been found to indicate that these plans were ever carried out.

The permanent floor was being laid in November 1845, making it possible to construct permanent tiered pulpits. In December Brigham Young, along with other leaders, “went down to the lower room and counseled on the arrangement of the pulpits." [101] On 1 January 1846 leaders found “the floor is laid, the framework of the pulpits and seats for the choir and band are put up; and the work of finishing the room for dedication progresses rapidly." [102] On this same date one year earlier a letter written by W. W. Phelps to William Smith was published in the Times and Seasons. It described features to be constructed in the interior of the temple. “The two great stories will each have two pulpits, one on each end; to accommodate the Melchisedek and Aaronic priesthoods; graded into four rising seats: the first for the president of the elders, and his two counsellors; the second for the president of the high priesthood and his two counsellors; the third for the Melchisedek president and his two counsellors, and the fourth for the president over the whole church, (the first president) and his two counsellors. . . . The Aaronic pulpit at the other end the same." [103]

J. H. Buckingham, who visited the temple a year after its dedication, left this description of the first story interior: “At the east and west end are raised platforms, composed of series of pulpits on steps one above the other. The fronts of these pulpits are semi-circular and are inscribed in gilded letters on the west side: PAP, PPQ, PTQ, PDQ, meaning, as the guide informed us, the uppermost one, President of Aaronic Priesthood; the second, President of the Priests’ Quorum; the third, President of the Teachers’ Quorum; and the fourth and lowest, President of the Deacons’ Quorum. On the east side the pulpits were marked PHP, PSZ, PHQ, and PEQ, and the knowledge of the guide was no better than ours as to what these symbolic letters were intended for." [104] The meaning of this last set of letters is explained in the previous paragraph except for the letters PSZ. They may have stood for President of the Seventy in Zion, but that is only conjecture.

James A. Scott, a member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints who attended the temple dedication on 1 May 1846, recorded the following description: “Inscriptions on the seats of the priesthood. Me P. highest seat PHP, 2nd PSZ, 3rd PHQ, 4th PEQ. A. P. highest seat PAP, 2nd PPQ, 3rd PTQ, 4th PDQ." [105] Scott confirms the PSZ lettering noted by Buckingham but offers no clarification. Further confirmation of the accuracy of this designation is provided by the same lettering being used on the Melchizedek Priesthood Pulpits in the St. George Temple (see note 104). Other descriptions show that each pulpit unit “was graded into four rising seats" [106] and was wide enough “to accommodate three persons each." [107] Each pulpit had its own decorative lettered insignia identifying its occupants.

On the wall in back of the highest pulpit on the east end was “an inscription in large gold letters," [108] which read “THE LORD HAS BEHELD OUR SACRIFICE: COME AFTER US." [109] An observer declared that these “two grand pulpits at the East and West ends gave to the whole an appearance of Oriental Magnificence." [110]

For conference meetings in the fall of 1845, temporary pulpits and seating were in place. At the west end of the large main hall “was constructed a large box for the use of the choir and players on instruments." [111] This may have been the area referred to as the galleries by L. O. Littlefield. Reporting his attendance at the conference, he stated: “I found a seat in the north gallery and had a commanding view of the congregation which spread out itself below and around me. . . . On either side ranged a solid phalanx of seated males, and all were oer-topt with down-gazing auditors that crowed the galleries." [112]

It is possible that temporary galleries or balconies had been constructed to provide additional seating at this conference. If so, these would have been taken down during the following month as the temporary floor was replaced. There is a single reference describing some type of gallery to be constructed on the permanent floor. “The gallery is to consist of different chambers, . . . which are all to be separated by veils, which can be drawn or withdrawn at a moment’s notice." [113] This described gallery may have been included as part of the large choir section that was built. Then again, due to the forced exodus these galleries may never have been constructed. There is no report of galleries being present as the first floor was finished. Another possibility is that for this fall conference temporary galleries were provided above the first floor in the unfinished first mezzanine. This area could have been open on the sides at this time and utilized as galleries to provide additional seating. Further explanation of this possibility is pursued in the next section.

Extent of Completion

The first story of the temple was completed with careful attention to detail and the highest quality of workmanship. It was described as “worthy of the attention of all architects who delight in originality and taste. It has been thronged with visitors from abroad since its completion, and excites the surprise and admiration of every beholder." [114] The vestibule entrance was complete, secured with doors and locks. Inside, the permanent wood floor was laid, and attractive decorated pulpits were in place along with large galleries for the choir and musicians. Visitors found “the inner temple an artistic work in the medium of wood, stone and glass." [115] One observer who visited the building in the fall of 1846 noted “the immense audience chamber . . . with its pews and changing backs, its immense altars and oratories, its gorgeous tapestry and motes in gold and silver, its ponderous chandeliers and innumerable columns and frescoes that elsewhere bewildered the eye with their gorgeous beauty." [116]

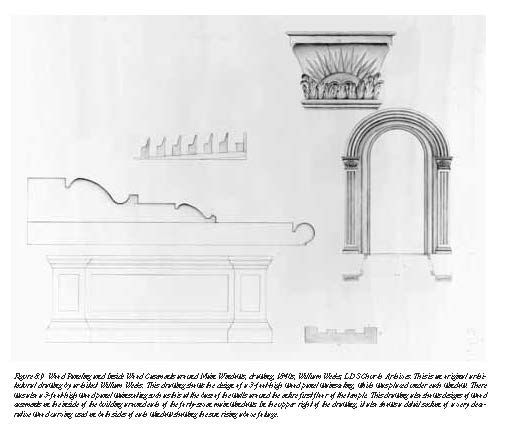

Another observer commented that “the work is of the best character . . . the carving both in wood and stone evinces great taste and ingenuity." [117] Much of the detailed finish work was completed as the exodus from Nauvoo was under way. Church leaders and many members had already gone west. In spite of this, the temple was pushed to completion. It was an unselfish act of love and devotion to God. Under the circumstances that existed, it is most significant to note the detail, artistry, and quality that was put into the efforts of these builders. Observers entering the main hall found that “the woodwork of the doors and windows was composed of beautifully carved work,” the tops of the door jambs being “ornamented with Corinthian capitals of the most exquisite workmanship!" [118] There was “beautiful vine work,” along with “delicately executed leaf and bud.” Bills for these artistically finished windows and door casings include orders for several pieces of door and window jambs, rails, pilasters, pedestals, capitals, sills, panels, sash, architraves, crown fillets, crown molds, and other items or pieces. [119] These were not simple, plain, or crude frames—they were works of art. Figure 8.10 illustrates the highly decorated woodwork around each window of this main floor. From descriptions and bills of materials it is evident that the same kind of work was put around each doorway as well.

Another observer commented that “the work is of the best character . . . the carving both in wood and stone evinces great taste and ingenuity." [117] Much of the detailed finish work was completed as the exodus from Nauvoo was under way. Church leaders and many members had already gone west. In spite of this, the temple was pushed to completion. It was an unselfish act of love and devotion to God. Under the circumstances that existed, it is most significant to note the detail, artistry, and quality that was put into the efforts of these builders. Observers entering the main hall found that “the woodwork of the doors and windows was composed of beautifully carved work,” the tops of the door jambs being “ornamented with Corinthian capitals of the most exquisite workmanship!" [118] There was “beautiful vine work,” along with “delicately executed leaf and bud.” Bills for these artistically finished windows and door casings include orders for several pieces of door and window jambs, rails, pilasters, pedestals, capitals, sills, panels, sash, architraves, crown fillets, crown molds, and other items or pieces. [119] These were not simple, plain, or crude frames—they were works of art. Figure 8.10 illustrates the highly decorated woodwork around each window of this main floor. From descriptions and bills of materials it is evident that the same kind of work was put around each doorway as well.

Wooden panels of varying lengths were used as part of a 3-foot-high wainscoting at the base of walls around the entire floor. There were panels under each window, in between windows and in between doors. Illustration of this paneling and wainscoting (under the windows) can be examined by study of Figure 8.9. Bills for this wainscoting furnish valuable insight into the details of this woodwork. An example of one of these bills is as follows:

A Bill of Wainscoting for North and South Sides

24 Pieces 6 feet 11 long x 5½ 1½

24 " 2 " " 3½ 1½

24 Panels 6 " 8 " 1½ 1

86 feet for west End wainscoting.

43 feet of panels x 14 1

43 " of fillet x 3_ 1¼

43 " of crown mold x 1¾ 1 [120]

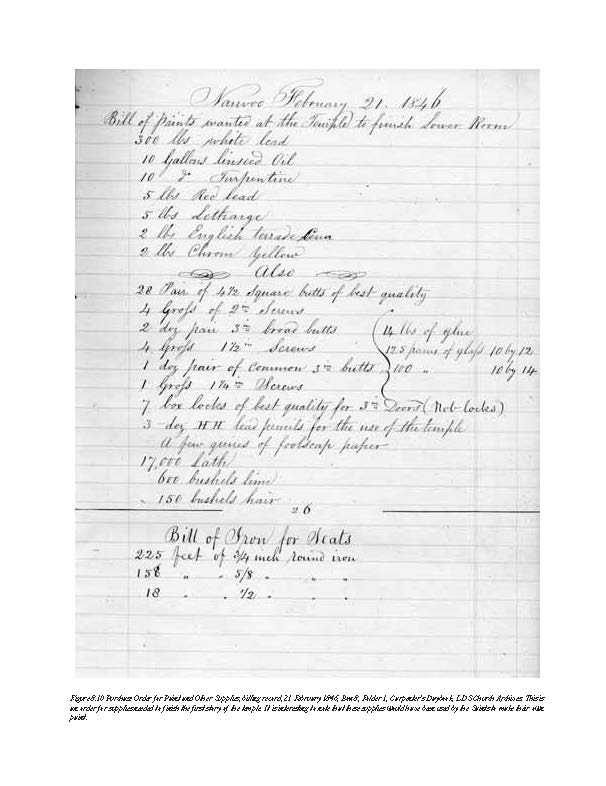

The arched semicylindrical ceiling over the main hall as well as the flat ceilings on the sides were all plastered and finished. A bill for this work was submitted on 21 February 1846; it included “17,000 lath 600 bushels lime and 150 bushels hair” (see Figure 8.11).

The first floor was predominantly white. Ceilings were plastered white, the stone walls were grayish white, and the woodwork was painted white or a light tan color. A bill of paints for the first floor included “300 lbs. white lead, 10 gallons linseed oil, 10 gallons turpentine, 5 lbs. red lead, 5 lbs. letharge, 2 lbs. English terra cena and 2 lbs. chrome yellow." [121]

The woodwork of the columns and cornice area around the bottom of the central arch was also specially finished. Bills of materials call for 205 feet each of crown molds, crown fillet, fascia, architraves, frieze, and other items, along with 214 mutules and mutule caps. [122] This was without question a place of extensive artistic detail.

The woodwork of the columns and cornice area around the bottom of the central arch was also specially finished. Bills of materials call for 205 feet each of crown molds, crown fillet, fascia, architraves, frieze, and other items, along with 214 mutules and mutule caps. [122] This was without question a place of extensive artistic detail.

After the dedication, many of the religious and decorative furnishings were removed from the temple. As noted by one observer, “When finished it was profusely ornamented on the inside, and dedicated by the most solemn services; these over, it was despoiled of its ornaments and abandoned.” He also noted: “The walls within the Temple were bare, the only ornaments being those cut in the wood or stone." [123]

The First Mezzanine Half-Story Recesses on the sides of the arch made it possible to construct a half-story on each side of the building between the first and second floors. The length of the recesses or half-stories was 100 feet. This created two side halls that were long but low and narrow. [124] These 100-foot-long hallways were each 18 feet 6 inches wide and 7 feet high (see architectural drawings, Figure 7.1 and 8.12). It was intended that these areas be divided into seven rooms on each side of the building. Each room was to be lighted by one of the lower round windows. No record has been found to determine if the partitions and rooms were actually constructed. This area would have consisted of a long hallway some 3 to 5 feet wide, along with seven rooms approximately 14 feet square on each side of the building. Some may have been built due to the intent of conducting endowment ordinances at this location. Brigham Young once stated, “In the recesses, on each side of the arch, on the first story, there will be a suit of rooms or ante-chambers. . . . As soon as suitable number of those rooms are completed we shall commence the endowment." [125] Since the endowment ordinances were moved to the main attic area, records are absent on any use of the first mezzanine. Layout of the floor plan for this first mezzanine can be studied by examining Figure 8.12.

There is some possibility that on a temporary basis this mezzanine was used as a gallery overlooking the main hall below, which is supported by the report of one observer who described having “a seat in the north gallery and had a commanding view of the congregation which spread out itself below and around me." [126] If temporary galleries were used here in the fall of 1845, they probably lacked tiered seating. This would mean that most of those seated there would have been unable to see the pulpits. Unfinished at this date, the first mezzanine could have been open on the sides, thus allowing such usage.

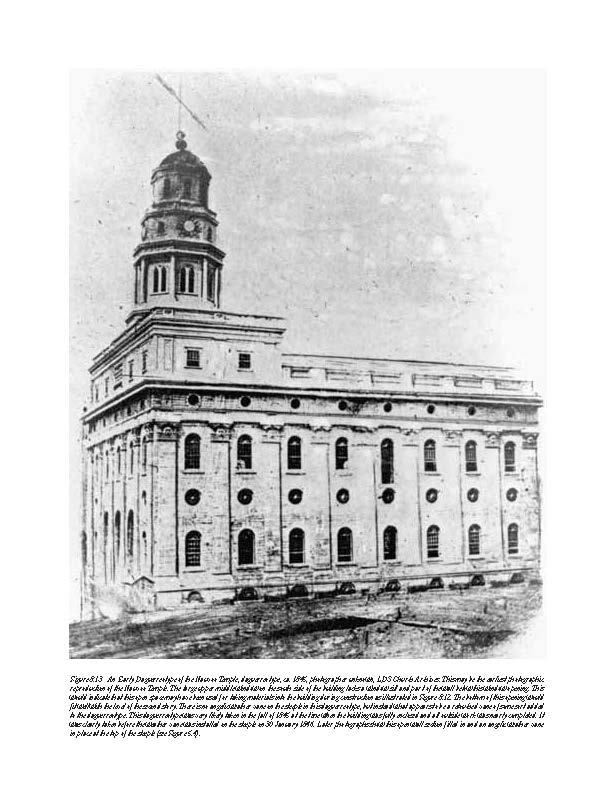

The Second Story As interior floors of the temple were under construction, observers could view “range upon range of massive timber,” and one visitor expressed being impressed with “the stupendous height of the ceiling, and the massiveness and quality of the timber." [127] Richard Jackson, a retired Church architect, noted an interesting possible method of construction used in building this floor and other floors of the temple. Jackson also served a Church mission in Nauvoo and has carefully studied the architecture and construction of the Nauvoo Temple. He notes that two very old photographs of the building show

the fifth window from the front on the third floor [second story] not yet having a sill in one and a modified sill in the other. In both it is obvious that the window opening extended down to what would probably have been the floor level, most likely to allow roof and floor framing members to be brought into the building for installation in the middle bay. A gin-pole would have been mounted on the top of the outside wall with a swinging boom-arm with a pulley on the end [see Figure 8.13]. The member would be raised to the level of the third floor [second story] by a horse pulling on a rope through a pulley on the ground. At the floor level, the member would be pulled into the building and unloosed. It would then be picked up with a similar pulley system mounted on top of the intermediate column supports and from there elevated or lowered into the Figure 8.13 desired position in the middle bay. When the work was finished the window opening would have been closed with matching material but the material lines show. [128]

Figure 8.13. Roof and Floor Framing Construction Process. Sketch by Richard Jackson.

Jackson’s observations are sustained by the earliest known daguerreotype of the building (see Figure 8.14), which indicates that this particular window area was indeed open and could easily have been utilized in the manner that he explained. Permanent stone steps in front of the building were not completed until late in the building’s construction. It is most likely that this opening and another like it on the north side were needed for bringing construction materials into the building. It would not be practical to bring everything in through the front entrances. Heavy beams and timbers used in construction would have been too cumbersome to move by hand. The floor of this story was supported by six 12-inch-diameter posts on each side of the building, along with the timbers and joists just like that of the first story.

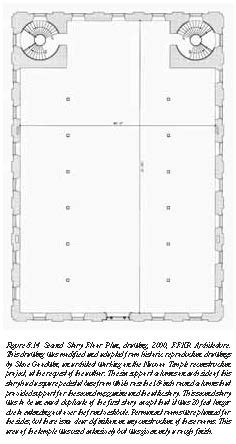

The second story was designed to be an exact duplicate of the first. It was, however, 20 feet longer than the first story in consequence of running out over the top of the front outer court or vestibule. This additional open space was marked by a stone arch which 41 feet and served as support for the tower. An excellent view of this arch can be seen by examining Figure 11.2. This artist’s sketch has some discrepancies in that it shows no access to the mezzanine levels and has another problem, as cited by Tim Maxwell: “The arch must have been the artists attempt to picture one that had in fact already collapsed at the time of the drawing. The arch pictured is far too thin over the top to have carried the tremendous dead weight and wind loads of a 90-foot-high tower. More likely the arch masonry was 8 to 12 feet deep at the thinnest point over this ." [129]

The room of the second story is described by Lanman as being in every particular precisely like that of the first story. [130] It was well lighted by large windows on both sides and both ends of the building. On 20 January 1846 it was announced in the Times and Seasons that “the floor of the second story is laid." [131] After the floor was laid, this hall was used on many occasions. Strong and substantial, this floor supported large crowds of people as they gathered here for the various meetings conducted in this part of the building. Typical of these meetings is the following, as Hosea Stout observed: “Went to the Temple to a public meeting in the Second Story but the congregation was so numerous that it would not contain them." [132] Brigham Young reported that on 24 January he “attended a general meeting of the official members of the church held in the second story of the Temple, for the purpose of arranging the business affairs of the church prior to our exit from this place." [133] Another example of such meetings is the report of Sunday services or a “public” meeting conducted in the second story of the temple on 1 February 1846. [134]

The room of the second story is described by Lanman as being in every particular precisely like that of the first story. [130] It was well lighted by large windows on both sides and both ends of the building. On 20 January 1846 it was announced in the Times and Seasons that “the floor of the second story is laid." [131] After the floor was laid, this hall was used on many occasions. Strong and substantial, this floor supported large crowds of people as they gathered here for the various meetings conducted in this part of the building. Typical of these meetings is the following, as Hosea Stout observed: “Went to the Temple to a public meeting in the Second Story but the congregation was so numerous that it would not contain them." [132] Brigham Young reported that on 24 January he “attended a general meeting of the official members of the church held in the second story of the Temple, for the purpose of arranging the business affairs of the church prior to our exit from this place." [133] Another example of such meetings is the report of Sunday services or a “public” meeting conducted in the second story of the temple on 1 February 1846. [134]

This area of the temple was said to have been “partially finished, having benches and temporary pulpits which could be used in case of necessity." [135] These pulpits and seating were probably the same ones used on the first floor for the October 1845 conference. Some office rooms may have been constructed along the sides of the main hall. Doors for those offices were ready by midsummer 1845, and bills of materials call for locks, hinges, etc. [136] Since they were ready this early, it is likely that some of them were put in place. A reporter from the Illinois Journal wrote that there were “small rooms eight or ten feet square on either side." [137] A description of these rooms and their exact location is uncertain. They may have been on the second floor level or on the level of the second mezzanine half-story. The floor was described as having a rough finish but was reportedly used for dances throughout the winter of 1845–46. [138] The room was also used for other recreation purposes following the exodus of the Mormons from Nauvoo. No record seems to be available describing the plastering or painting of this section of the building. Available evidence leads to the conclusion that this area, though not totally finished, was functionally completed and extensively used. A layout of the second story is found in Figure 8.15.

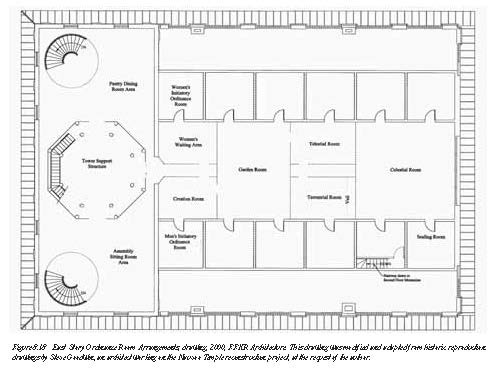

The Second Mezzanine or Upper Half-Story There is very little information on this area of the temple. It was planned to be identical in size and configuration with the lower mezzanine half-story. The only basic difference between the two was the size of the round windows. Smaller round windows providing illumination to this mezzanine section had a star shape configuration in the window panes (see Figures 6.2 and 7.12). The panes were colored glass or were painted in colors red, white, and blue. [139] From November 1845 through April 1846, heavy emphasis and urgency was given to work on the second story and the completion of the first story. It is therefore very likely that both the lower and upper mezzanine half-stories were only roughed in and never finished. No record has surfaced describing rooms, floors, extent of finish, or usage for this upper mezzanine section of the building. A layout of this second mezzanine and the proposed design of its rooms is found in Figure 8.16. It should be noted that a set of stairs was installed providing access between this mezzanine and the east attic area above it. This is explained in greater detail later in this chapter in the section describing the east main attic of the building.

The Front Attic Section

A boxlike rectangular attic or half-story the width of the stone walls on the west end at the top of the building. This front attic section was 86 to 87 feet long. Extending back from the front, it had a depth of 36 to 37 feet (see Figure 7.2). It was described as being 16½ feet in height. [140]

The inside of this front attic was described as containing “two or three large square rooms." [141] A nearly square room on the south end measured about 27 feet north to south and about 32 feet east to west. Nearly one quarter of this room was taken up by the southwest corner stairwell, as it rose from the basement to this level (see diagram of this floor level, Figure 8.17). The rest of this room was an assembly or waiting room area for those coming to receive their endowments (see note 142 for a justification for this conclusion). [142] In the center of this attic area was “a massive pine frame, from the centre of the roof from which rises the tower." [143] This large supporting timber frame was octagonal in shape and 29 feet in width. On the west side of this framed area between it and the outside wall was a narrow space only 2 or 2½ feet wide (see diagram in Figure 8.17). On the east side between this steeple base and the wall between the two attics was another narrow space of the same width. Open passageways are believed to have led into the interior of this framed tower base area. Here stairs could be accessed leading to the tower sections above. Access could be gained to the large room on the north end and also into the main east attic (see Figure 8.17). On the north end of this front attic was a room known as the “pantry” or “dining room,” identical in size to the south room. It had the same space taken up by a stairwell as the stairs rose to this level in the northwest corner of the building. This room was widely used by Church authorities, construction workers, temple ordinance workers, and patrons to eat and store food. [144] This was an essential accommodation necessitated by nearly round-the-clock temple ordinance work during December 1845, through January and early February 1846.

The front attic section was well illuminated during daylight hours by eight rectangular windows. Some seating may have been provided in the reception or assembly room, but no reference verifying this has been found. It is also likely that seating and tables were located in the pantry room, but again no information has surfaced to validate this conclusion. There appears to be no documentation as to whether or not this area was finished. However, it is likely that the area was plastered and painted at the same time as the east or main attic. Had it remained unfinished, it would most likely have been noted by observers.

The front attic section was well illuminated during daylight hours by eight rectangular windows. Some seating may have been provided in the reception or assembly room, but no reference verifying this has been found. It is also likely that seating and tables were located in the pantry room, but again no information has surfaced to validate this conclusion. There appears to be no documentation as to whether or not this area was finished. However, it is likely that the area was plastered and painted at the same time as the east or main attic. Had it remained unfinished, it would most likely have been noted by observers.

Tower or Steeple Section From the center of the front attic section rose an octagonal tower. Its timber framework was massive, containing posts, beams, braces, and supports (as can be observed by examining of Figures 7.3 and 12.1). Inside the framework of this tower was “a series of steps which were very steep." [145] Climbing up from the attic one could “ascend to the bell room of the steeple, thence to the clock room, at last to the observatory." [146] One who climbed the full height of this stairway described having “to ascend 15 flights of steps to reach the top." [147] This description undoubtedly also included the flights of stairs below the attic level.

The tower consisted of various sections. As the tower rose in height, those sections diminished in width, creating a telescopic effect. The base or pedestal section was 29 feet in diameter. It started on the floor of the attic and rose another 12½ feet above the attic roof. At the roof level on the east side of this octagonal base was a small doorway that provided access to the deck roof over the top of the main east attic. [148] The section above the base or pedestal narrowed to 22 feet in diameter. It was composed of the belfry and, directly above it, the clock section. The belfry had eight openings, each with two louvered Gothic shutters. The openings were about 4 feet wide and 10 feet tall. The louvers of the shutters were painted green. It is not clear as to whether any glass windows were put in the belfry section, but it likely remained open to the air. The belfry housed a large bell.

The tower consisted of various sections. As the tower rose in height, those sections diminished in width, creating a telescopic effect. The base or pedestal section was 29 feet in diameter. It started on the floor of the attic and rose another 12½ feet above the attic roof. At the roof level on the east side of this octagonal base was a small doorway that provided access to the deck roof over the top of the main east attic. [148] The section above the base or pedestal narrowed to 22 feet in diameter. It was composed of the belfry and, directly above it, the clock section. The belfry had eight openings, each with two louvered Gothic shutters. The openings were about 4 feet wide and 10 feet tall. The louvers of the shutters were painted green. It is not clear as to whether any glass windows were put in the belfry section, but it likely remained open to the air. The belfry housed a large bell.

The clock section was designed to have a clock on the four different faces of the tower. In between each of the clock facings were small windows. No descriptions have been found of this section’s interior. Above the clock section was the observatory, which diminished in size to a diameter of 17 feet. This area had eight windows, and it is likely that these windows had glass in them and could be opened to permit observation. Careful examination of the Chaffin daguerreotype (see Figure 5.4) indicates partially open windows in this section of the tower. It also shows that these had diamond-shaped, leaded glass panes. Rising above the observatory was the dome, said to be diminished in size to about 13 or 14 feet at its base. There are reports of visitors writing their names on the ceiling inside the dome. [149]

There is a bill in the temple billing records calling for 2,225 feet of floor to be used in various sections of the tower and its stairways. [150] The stairs were described by an observer who noted that some of the finishing work was not done, “the inside of this was not entirely finished,” making it possible for visitors “to observe the massive strength of the frame-work, and perceive the solidity and view the durability, with which it was constructed. The bare timbers presented a never-ending system of braces, each supporting the other successively." [151]

The Main East Attic Area

Brigham Young clearly described the layout and dimensions of this area:

The main room of the attic story is eighty-eight feet two inches long and twenty-eight feet eight inches wide. It is arched over, and the arch is divided into six spaces by cross beams to support the roof. There are six small rooms on each side about fourteen feet square. The last one on the east end on each side is a little smaller.