Joseph F. and Martha Ann's Parents

Richard Neitzel Holzapfel and David M. Whitchurch, "Joseph F. and Martha Ann's Parents," in My Dear Sister: Letters between Joseph F. Smith and His Sister Martha Ann Smith Harris, ed. Richard Neitzel Holzapfel and David M. Whitchurch (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2019), lv–lxxi.

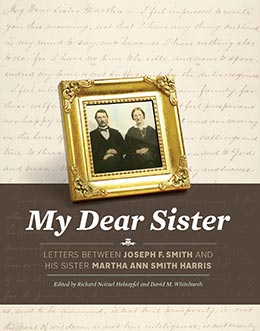

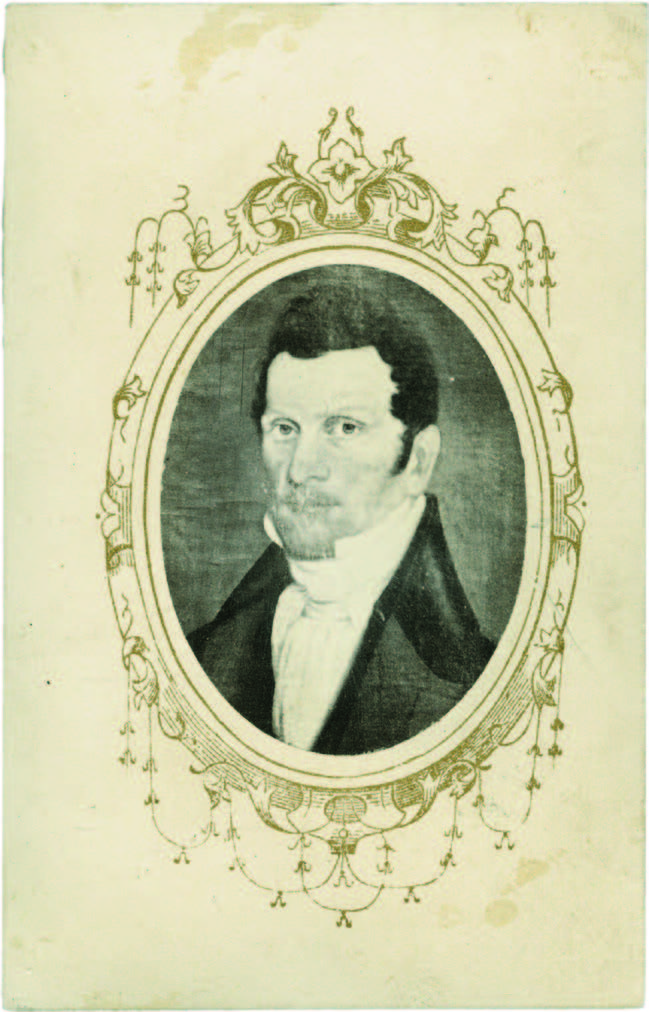

Hyrum and Mary Fielding Smith portraits, ca. 1842, by Sutcliffe Maudsley. Courtesy of CHM.

Hyrum and Mary Fielding Smith portraits, ca. 1842, by Sutcliffe Maudsley. Courtesy of CHM.

Joseph F. and Martha Ann Smith’s parents were Hyrum (1800–1844) and Mary Fielding Smith (1801–52).[1] Naturally, Hyrum and Mary Fielding became larger-than-life heroes in the memory of Martha Ann and Joseph F. because of their young ages at the times of their parents’ death.[2] Modern Latter-day Saints inherited that memory—a memory that continues to shape our understanding of the past.

Hyrum Smith was born in Tunbridge, Orange County, Vermont.[3] He was the second son of Lucy Mack (1775–1856) and Joseph Smith Sr. (1771–1840). His brother Joseph Smith Jr. (1805–44) was born just before Hyrum’s sixth birthday. At the age of about six, Joseph contracted typhoid fever followed by a severe bone infection (osteomyelitis) in his left leg.[4] According to a family tradition, Hyrum, already known for his tender and compassionate nature, helped the family by assuming much of the personal care Joseph required.[5]

From this and other experiences, the two brothers developed a deep bond that lasted throughout their lives.[6] Hyrum became one of Joseph’s closest advisers, confidants, and co-laborers from the earliest period of the Restoration of the gospel of Jesus Christ through the establishment of the Church, and he remained so until his martyrdom at Joseph’s side in 1844.[7]

The Smith family eventually moved from Vermont to Palmyra, Wayne County, New York. Joseph Sr. had purchased one hundred acres in nearby Manchester Township by 1820.[8] He and his oldest sons began immediately to clear the land for farming. Additionally, the Smith boys worked as day laborers to supplement the family income in order to pay the annual mortgage on the farm.[9]

Hyrum and several family members, including his mother, became members of the Western Presbyterian Church of Palmyra in the early 1820s.[10] Between 1820 and 1827, many of the founding events of the Restoration of the gospel of Jesus Christ took place in New York. Eventually, the family became involved in the coming forth of the Book of Mormon (1827–30) and the organization of the Church of Christ (1830).

During this period, on 2 November 1826, Hyrum married Jerusha T. Barden (1805–37).[11] She was remembered by the family for her “singular beauty and fine character.”[12] Her mother-in-law, Lucy Mack Smith, said Jerusha was “one of the most excellent women, with whom I [have] seen much enjoyment.”[13] Over the years of their marriage, Jerusha developed a very close relationship with Hyrum’s mother and “was so endeared to the family that she enjoyed their greatest confidence.”[14]

Hyrum and Jerusha Smith. Each has an inscription on the reverse side. Hyrum’s card reads, “Hyrum Smith Patriarh & Martyr from a Likeness taken in his 34th year by ‘Webber’ of Kirtland.” Jerusha’s card reads, “Jerusha Barden Wife of Hyruym Smith Patgriach and Mother of John Smith Patrarch.” Original spelling retained. Courtesy of CHL.

Hyrum and Jerusha Smith. Each has an inscription on the reverse side. Hyrum’s card reads, “Hyrum Smith Patriarh & Martyr from a Likeness taken in his 34th year by ‘Webber’ of Kirtland.” Jerusha’s card reads, “Jerusha Barden Wife of Hyruym Smith Patgriach and Mother of John Smith Patrarch.” Original spelling retained. Courtesy of CHL.

In 1827, Jerusha gave birth to their first child, a daughter named Lovina (1827–76). Nearly two years later, Hyrum’s brother, Joseph Smith, dictated a revelation for him, known today as Doctrine and Covenants 11. Within a month, he was baptized by his brother Joseph Smith in June 1829.[15]

Another girl, Mary, was born (1829–32) to Hyrum and Jerusha on 27 June 1829. Shortly thereafter, Hyrum saw and handled the Book of Mormon plates along with seven other men who became known as the Eight Witnesses.[16] Their testimony is still published with the Book of Mormon.[17]

On 6 April 1830, Hyrum became a founding member of the Church of Christ. Jerusha was baptized shortly thereafter in June 1830.[18] Apparently, Jerusha’s family was not supportive of her decision to join the “Mormons.”[19]

As conflict and challenges intensified in New York against the Church in 1830, Hyrum and his family joined the Saints gathering in Kirtland, Geauga (renamed Lake) County, Ohio, in early 1831.[20] During the following years, Hyrum was often absent from home, serving and working with his brother Joseph Smith, the President of the Church, as one of the leading elders in the Church.[21]

Tragically, Hyrum and Jerusha’s second child, Mary, died on 29 May 1832. In his diary, Hyrum recorded his grief at losing his young daughter: “Not passing mutch tribulation until the 29th of May then I was Cald to view a Scene which Brought sorrw to unto me Sorrow and mourning Even a scene of Death Mary was Cald from time to a ternity on the 29th Day of May She expired in mine arms s Such a Day I never Before exspeirenced and O may god grant that we may meet her again At the greate Day of redemption to part no more.”[22]

Hyrum and Jerusha’s first son, John (1832–1911), was born in Kirtland on 22 September 1832. Three more children were born to Jerusha and Hyrum in Ohio: Hyrum [sometimes spelled Hiram] Smith (1834–41) on 27 April 1834, Jerusha Smith (1836–1912) on 13 January 1836, and Sarah Smith (1837–76) on 2 October 1837.

The Smith home in Kirtland was described as “affectionate and happy, . . . where culture and refinement were characteristic qualities.”[23] It was also the center of considerable activity, as it was often used as a meetinghouse for church services, a gathering place for extended family, and a hospice of sorts for anyone in need of assistance.[24]

During the Kirtland period, Hyrum continued to play a significant role in the Church. For example, in February 1832 he was appointed counselor to Bishop Newel K. Whitney. The following year he was called to be a member of the committee to supervise construction of the Kirtland Temple. Then in September 1834, he was called to the Kirtland high council. Three years later, in September 1837, he was sustained as assistant counselor in the First Presidency, and just two months later he replaced Frederick G. Williams as second counselor in the First Presidency.[25]

During this period, Hyrum received a blessing in which he was promised, “If thou desirest thou mayest bring many souls to Jesus.”[26] Tragically, Jerusha died suddenly on 13 October 1837, eleven days after giving birth to Sarah. Hyrum was en route to Missouri on church business at the time with his brothers Joseph and William. His brothers Samuel and Don Carlos wrote a letter to inform him of her death. They wanted Hyrum to “rest assured that we have done all that we could do to save Jerusha but in vain She is no more, her place can never be supplied! O the scenery, the scenery how afflicting! The funeral I expect will be on the Sabbath at 10 o’clock.”[27]

Jerusha’s obituary in the local newspaper noted: “She has left five small children together with numerous relatives to mourn her loss, a loss which is severely felt by all. Our sister was beloved and highly esteemed by every lover of truth and virtue.”[28] On hearing the news, Hyrum was grief-stricken and shortly afterward left Far West, Missouri, to return to Kirtland.[29] In the meantime, a family friend, Hannah Woodcock Grinnels (1783–1853), took care of the motherless children until he arrived back in Kirtland around December 10.[30]

Before Jerusha’s death, a recent convert named Mary Fielding (1801–52) arrived in Kirtland from Toronto, Upper Canada (generally comprising present-day southern Ontario), where she and her brother Joseph (1797–1863) and her sister Mercy (1807–93) had been converted and baptized. The Fieldings had migrated to Canada from England.[31] In Kirtland, the Fieldings became acquainted with Hyrum and his family. Mary eventually became part of Hyrum’s family.[32]

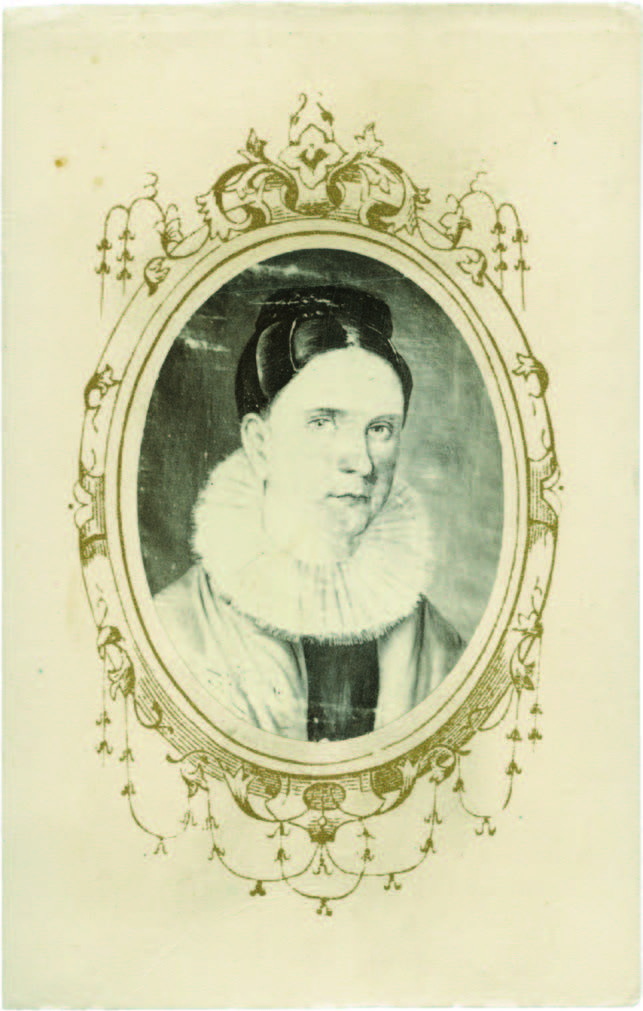

Liberty Jail, ca. 1878, photograph by J. T. Hicks. Courtesy of CHL. Joseph F. received this image on 8 September 1878. An inscription on the back notes, “From Miss Josie Schweich Richmond, Ray Co. MO. grand-daughter of D. Whitmer.”

Liberty Jail, ca. 1878, photograph by J. T. Hicks. Courtesy of CHL. Joseph F. received this image on 8 September 1878. An inscription on the back notes, “From Miss Josie Schweich Richmond, Ray Co. MO. grand-daughter of D. Whitmer.”

Mary Fielding was born on 21 July 1801, at Honydon, Bedfordshire, England.[33] She was the sixth child of John Fielding (1759–1836) and Rachel Abbotson (1767–1828).[34] The Fielding family were strict Methodists—the faith Mary Fielding brought with her to Upper Canada in 1834 when she emigrated to join her brother and sister.[35]

On 24 December 1837, following the death of Jerusha, Mary Fielding (age thirty-six) and Hyrum (age thirty-seven) were married.[36] Mary Fielding effectively became the mother to Jerusha’s five children.[37]

In 1838, Hyrum and Mary took their family to the new Church gathering place of Far West, Missouri.[38] Their stay there did not last long. In August, tension on the Missouri frontier between Latter-day Saints and some Missourians flared into violent skirmishes. The conflict tragically increased, resulting in a three-month conflict known as the Missouri Mormon War.[39]

Several encounters occurred during the conflict, including the Battle of Crooked River, which left three Latter-day Saints and one Missourian dead, and the Hawn’s Mill massacre, which left seventeen Latter-day Saint men and boys dead and another fourteen wounded.[40]

Just days before the Hawn’s Mill massacre, after hearing exaggerated reports about a full-scale “rebellion” in northern Missouri, Governor Lilburn W. Boggs (1796–1860) issued Executive Order 44, also known as the extermination order, authorizing the expulsion of all Latter-day Saints from the state.[41] In the end, as word spread of Boggs’s executive order, attacks on the Latter-day Saints ended when their enemies realized the Latter-day Saints would now be forced to move beyond state boundaries.

Hyrum and Joseph were arrested by state militia officers at Far West, Caldwell County, on 31 October. After a short stop in Jackson County, they were held almost one month (4–29 November) in the Richmond Jail in Ray County and just over four months (1 December 1838—6 April 1839) in Liberty Jail in Clay County.

The conditions in this filthy jail during the winter of 1838–39 were horrific. Joseph and Hyrum were at times lonely, hungry, cold, sick, and despondent. Joseph’s description paints a terrible scene:

Thursday night I sat down just as the sun is going down, as we peak throu the greats of this lonesome prision, to write to you, that I may make known to you my situation. It is I believe <it is> now about five months and six days since I have bean under the grimace, of a guard night and day, and within the walls grates and screeking of iron dors, of a lonesome dark durty prison. With immotions known only to God, do I write this letter, the contemplations, of the mind under these circumstances, defies the pen, or tounge, or Angels, to discribe, or paint, to the human mind being, who never experiance what I we experience. This night we expect; is the last night we shall try our weary joints and bones on our dirty straw couches in these walls, let our case hereafter be as it may, as we expect to start tomorrow. . . . we cannot get into a worse hole then this is, we shall not stay here but one night besides this if that thank God, we swall never cast a lingering wish after liberty in clay county Mo. we have enough of it to last forever.[42]

On 13 November 1838, two weeks after Hyrum’s arrest, Mary gave birth to their first child—Joseph Fielding Smith (1838–1918), but also known as Joseph F. Smith through much of his life.[43] Mary was sickly for much of the next four months.

The separation and the lack of communication between them caused challenges for each.[44] Finally, in January 1839 Mary traveled forty miles on a makeshift bed in the back of a wagon to visit her husband in the Liberty Jail. During her overnight visit, Hyrum saw his son for the first time and may have blessed him.[45]

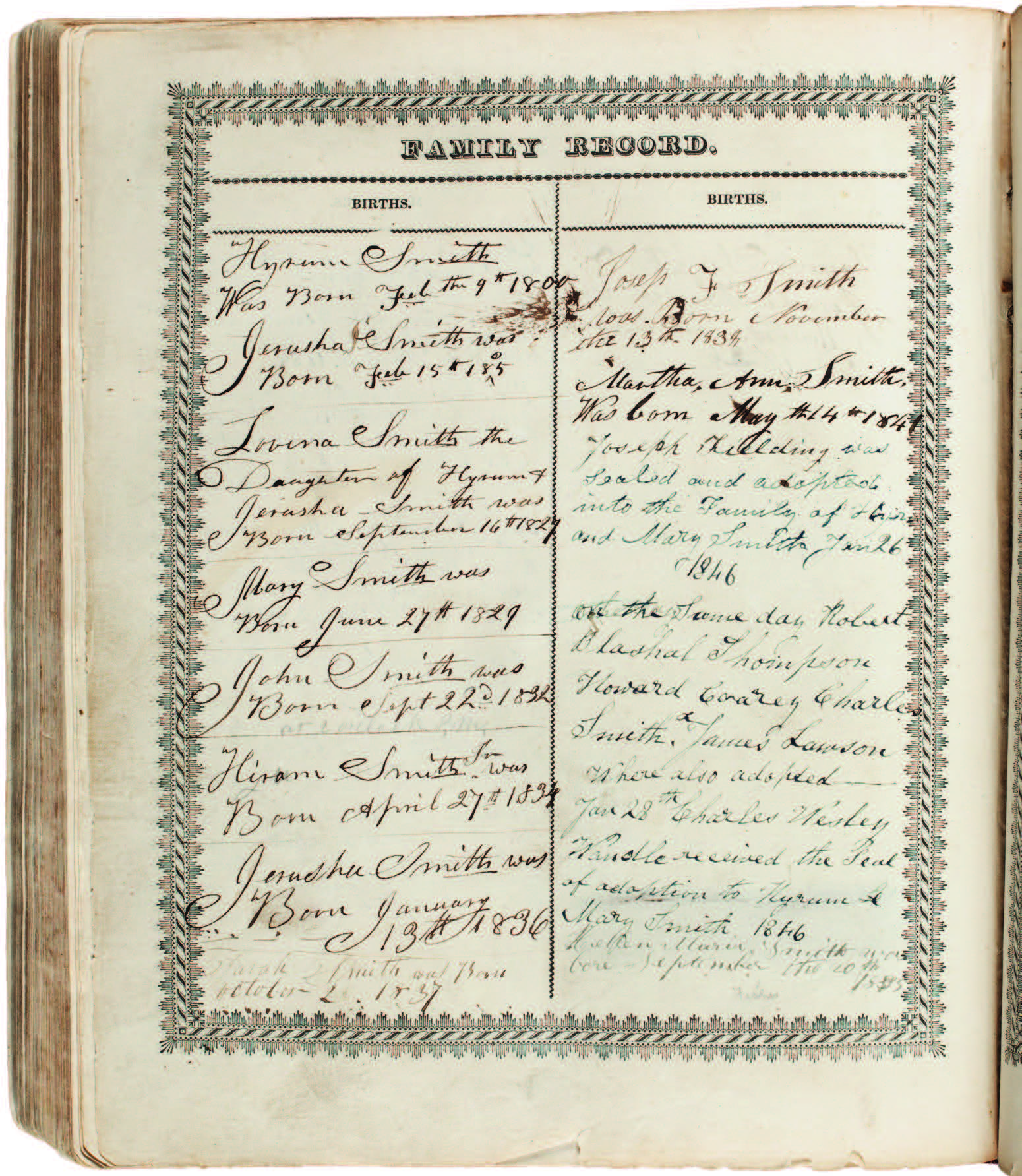

Hyrum Smith family Bible, The Holy Bible (Boston: Langdon Coffin, 1834). Courtesy of BYU. Like many other large-size Bibles of the day, this one had been printed so that family history information could be recorded. Here someone noted the births of Joseph F. and Martha Ann in a preprinted section titled “Family Record.”

Hyrum Smith family Bible, The Holy Bible (Boston: Langdon Coffin, 1834). Courtesy of BYU. Like many other large-size Bibles of the day, this one had been printed so that family history information could be recorded. Here someone noted the births of Joseph F. and Martha Ann in a preprinted section titled “Family Record.”

Nauvoo Landscape, ca. 1859, painting by Johann Schröder. Courtesy of CHM.

Nauvoo Landscape, ca. 1859, painting by Johann Schröder. Courtesy of CHM.

As their leaders languished in a Missouri jail during the winter of 1838–39, the Latter-day Saints were forced to leave their homes to comply with the extermination order issued by Governor Boggs. Like many other beleaguered Saints, Mary fled to Quincy, Adams County, Illinois, seeking refuge from the violence and persecution in northern Missouri.

In early April 1839, a hearing for Hyrum and the other Latter-day Saint prisoners was held in Gallatin, Missouri. During the proceedings, the judge granted a change of venue and issued an order for Church leaders to be taken to Columbia, Boone County, Missouri. While en route on 16 April, the prisoners were allowed to escape. A few days later, Hyrum and Joseph were reunited with their families in Illinois. Shortly thereafter, Hyrum, Mary, and their children settled in Commerce (later Nauvoo), Illinois, which had been identified as the next major Latter-day Saint gathering place.[46]

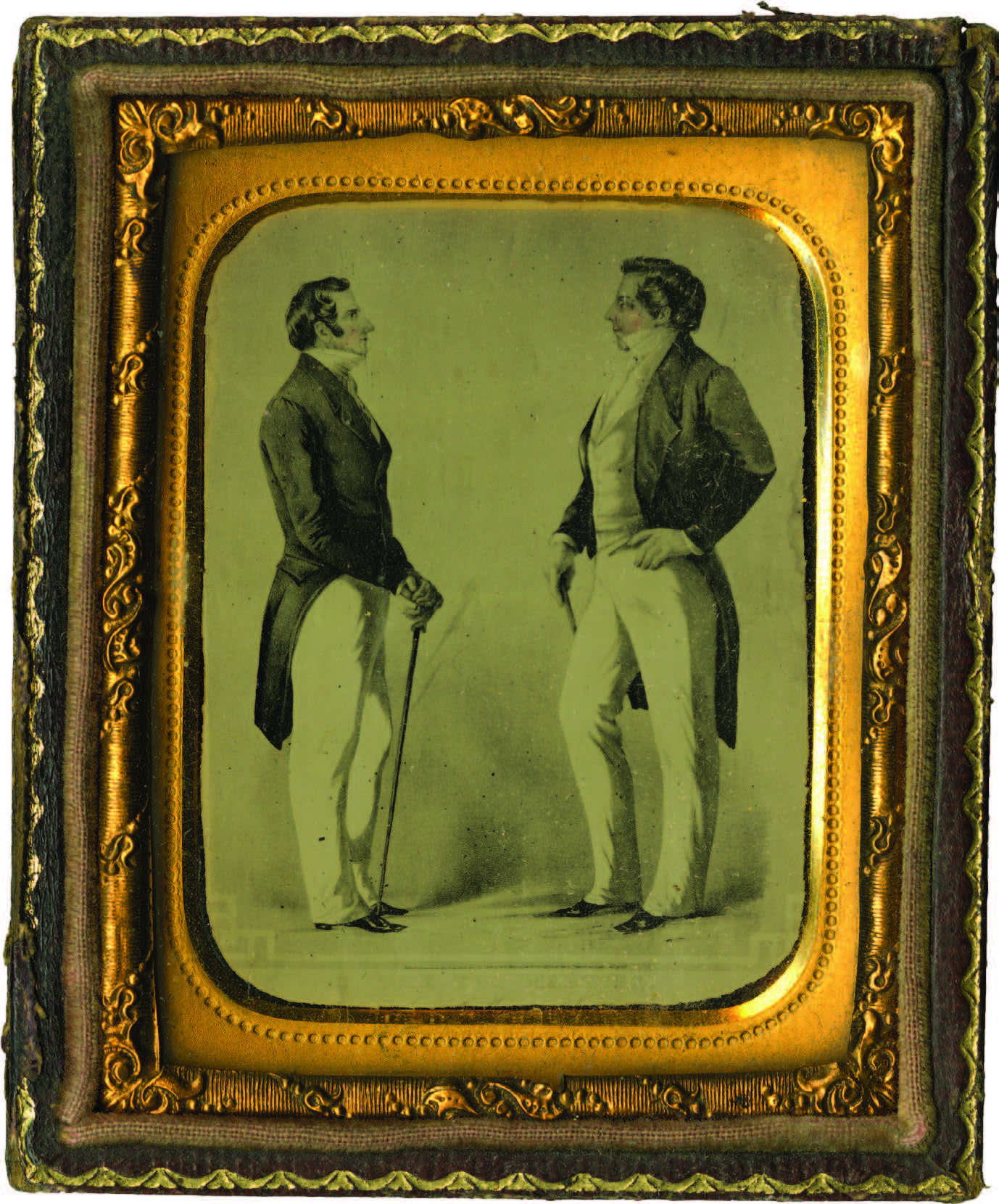

Joseph and Hyrum Smith, image based on David Rogers’s painting, ca.1842, published by Jules Remy and Julius Brenchley, A Journey to Great-Salt-Lake City (London: W. Jeffs, 1861). Courtesy of CHL.

Joseph and Hyrum Smith, image based on David Rogers’s painting, ca.1842, published by Jules Remy and Julius Brenchley, A Journey to Great-Salt-Lake City (London: W. Jeffs, 1861). Courtesy of CHL.

During this period in Nauvoo, Hyrum was called to assume Oliver Cowdery’s position, as stated in Doctrine and Covenants 124:91–96. As a result, he played an increasingly significant role in the religious, social, political, and economic activities in the Church. While Joseph Smith was in Washington, DC, for example, Hyrum wrote him a lengthy letter, dated 2 January 1840, highlighting his activities while Joseph was absent from Nauvoo.[47]

In Nauvoo, Mary and Hyrum welcomed their second child, Martha Ann (1841–1923) on 14 May 1841. Later that year, Hyrum buried his seven-year-old son, Hyrum Jr. What Joseph F. remembered about that event is not known. It was not, however, the last time Joseph F. witnessed the burial of a young child.[48]

As an increasing number of Saints moved into western Illinois, many local and influential citizens in Hancock County feared Latter-day Saint political and economic power.[49] By 1841, the Anti-Mormon Party had been organized as a political tool. Unfortunately, physical violence—so common in pre–Civil War America and largely aimed at abolitionists, minority ethnic groups, and religious groups—eventually became the main method used to drive the Latter-day Saints from the state.[50]

During this tense period, Hyrum joined in the introduction of new ordinances when on 4 May 1842 he was washed, anointed, and endowed in Joseph Smith’s red brick store on Water Street in Nauvoo, along with several other Church leaders.[51] Hyrum and Mary were sealed for time and eternity on 29 May 1843.[52] By 23 December 1843, Mary Fielding was administering these ordinances to other women. Bathsheba W. Smith recalled receiving her own blessings when Mary “pour[ed] oil on” her head and “blessed” her.[53]

When the temple was open to the Saints, following the deaths of Joseph and Hyrum, Mary Fielding worked there to help them receive the same temple blessings she had received earlier. Martha Ann recalled, “I went with my mother every day for three weeks while she worked in the Nauvoo Temple. What joy that was to me.”[54]

Hyrum and Mary Fielding also participated in plural marriage, which was being taught and practiced by a select group of Saints in Nauvoo.[55] Hyrum married Mercy Rachel Fielding Thompson, Mary Fielding’s sister, on 11 August 1843.[56] Plural marriage became a lightning rod for increased antagonism from without and rebellion from within the Church, including by some senior leaders.

In 1844, tension reached a fever pitch. Opposition to Joseph Smith was coming from both within and without the Latter-day Saint community:

The opposition that Joseph Smith faced stemmed from a variety of sources. Many non-Mormons in the area, for example, felt the Nauvoo Municipal Court had overstepped its authority on 1 July 1843 when it discharged Joseph Smith from his arrest in Dixon. Following the Democratic Party’s virtual sweep in the August 1843 county elections, others, especially local Whigs, opposed Smith’s growing political influence in western Illinois. In addition, rumors, misunderstandings, and disagreements about the practice and validity of plural marriage turned several influential Latter-day Saints against the Mormon leader. Some church members also turned against him over doctrinal developments—such as those taught in the King Follett discourse—and over concern that his roles as president of the church and mayor of Nauvoo represented a dangerous combination of church and state. Joseph Smith’s tendency to speak freely and publicly against his detractors—a habit his brother Hyrum cautioned him about—also probably contributed to the intensity of the opposition against him.[57]

At this time a small but influential group of Latter-day Saint business, political, and Church leaders organized what they denominated the True Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (or Reformed Church) as an alternative to Joseph Smith’s prophetic leadership. Opponents increasingly felt that Joseph and Hyrum had to be removed.

The conspiracy to kill the Smith brothers centered among influential men in Hancock County. Through a series of events, including the destruction of an opposition newspaper, the Nauvoo Expositor, in June 1844 Joseph and Hyrum were ordered to appear in Carthage, Hancock County.[58] They were held in the local two-story jail to await trial.

Thursday afternoon, 27 June 1844, was hot and humid. About 5:00 p.m. an organized armed body of men rushed Carthage Jail and within a few minutes of “scuffling, shouts, and shots”[59] murdered Joseph and Hyrum Smith.[60]

Joseph F. and Martha Ann recalled different details about the days following the martyrdom, but the general outlines remain consistent—Mary Fielding and her family experienced shock, dismay, anger, hopelessness, and fear.

Carthage Jail, 27 July 2015. Courtesy of the National Register of Historic Places.

Carthage Jail, 27 July 2015. Courtesy of the National Register of Historic Places.

The last time young Joseph F. saw his father alive was on a street in Nauvoo before going with his brother Joseph to Carthage Jail in June 1844. Joseph F., during a visit to Nauvoo, recalled, “‘This is the exact spot where I stood when the brethren came riding up on their way to Carthage. Without getting off his horse father leaned over in his saddle and picked me up off the ground. He kissed me good-bye and put me down again, and I saw him ride away.”[61]

Joseph F. recalled, “I heard the voice of Dimmick B. Huntington at the window of the old chamber of my mother’s home on the morning after the 27th day of June, 1844, saying to my mother, ‘Hyrum is dead!’ . . . It was a misty, foggy morning; everything looked dark and gloomy and dismal, not only to me, but I have heard scores of others say the very same thing. Now, these are some of the things I remember.”[62]

A non–Latter-day Saint observer of the events in Nauvoo recalled that Mary Fielding “had gathered her . . . children into the sitting room and the youngest [Martha Ann] about four years old sat on her lap. The poor and disabled that fed at the table of her husband, had come in and formed a group of about twenty about the room. They were all sobbing and weeping, each expressing his grief in his own peculiar way. Mrs. Smith seemed stupefied with horror.”[63]

Martha Ann and Joseph F. both remembered seeing the lifeless bodies of their father and uncle in the Mansion House in Nauvoo following their murders. Martha recalled, “Oh how I did love them & imagine again how I felt when I saw them laying side by side murdered in cold blood for preaching the gospel. . . . I saw the anguish & the sorrow the heart felt grief of my dear mother My dear brothers & sisters My aged grandmother & cousins & their mother I cannot never forget how dreadful it was.”[64]

Joseph F. also recalled the moment when Mary Fielding lifted him up to look at his dead father.[65] Historian Scott Kenney’s description captures the pathos of the tragic scene in the Mansion House, located on Water Street in Nauvoo:

Peering through the glass, he saw faces once so familiar, now distended and ashen, their jaws tied shut, cotton stuffed into the bullet hole at the base of his fathers’ nose. [Joseph F.] retained few memories of his father, but his mother’s lifting him to see Hyrum’s body was one of them. At five, he could not fully understand the meaning of death. The anguish in his mother’s voice, the sight of his father’s and Uncle Joseph’s barely recognizable bodies, the stench—it was no doubt a traumatic day. And not only on that day, but for many days following, the sorrow, anger, and fear of the entire community reinforced the horrendous nature of his father’s murder. How could the experience not have a lasting effect?”[66]

The sight and smell of death, especially the disfigured face of the father, Hyrum, had a frightful impact on Martha Ann and Joseph F. Stephen C. Taysom observed, “Unlike most children, who learn eventually that there is no monster under the bed, JFS learned early and often that the brutality he feared was very real, and that it would reach out and snatch happiness away from him with shocking caprice.”[67]

Hyrum Smith’s blood-stained shirt from when he was shot and killed in Carthage Jail on 27 June 1844.

Hyrum Smith’s blood-stained shirt from when he was shot and killed in Carthage Jail on 27 June 1844.

Photograph by Welden C. Andersen, 2010. Joseph F.’s and Martha Ann’s memories of their father’s murder was intensified by Mary Fielding Smith’s decision to preserve his clothing as a physical reminder of the brutality of the event. Courtesy of CHM.

Martha Ann and Joseph F. struggled to understand the significance of the tragic events during the last days of June 1844, but the memory of those events was engraved in their minds and hearts for the rest of their lives.[68] Martha Ann’s great-great-granddaughter recalled, “When I was a child of about six or seven, I was at my grandparents. Grampa [Elbert Startup] talked about how his grandmother [Martha Ann] would ask if he had a testimony of the gospel and of her father, Hyrum Smith, and Uncle Joseph’s work. Her last memory of her father was being lifted up as a young child and kissing him goodbye for the last time as he lay in his coffin.”[69]

Martha Ann wrote, “I can remember many little things of my beloved father’s death. How sad and sorrowful my mother would look. She scarcely ever smiled. If we could get her to laugh we thought we had accomplished quite a feat. I never saw her more than smile. . . . I can see that sorrowful look now [1881].”[70]

The deaths of Hyrum and Joseph were immediately followed by the death of Samuel H. Smith (1808–44), Martha Ann and Joseph F.’s uncle, on 30 July 1844.[71] Mary Fielding took in three of his children to help Samuel’s pregnant wife for a season. Of course, Mary Fielding’s main responsibilities centered on seven children—five older stepchildren (Lovina was married just days before Hyrum’s martyrdom) and two young children, Joseph F. and Martha Ann.[72]

During the winter of 1845–46, the Nauvoo Temple was completed to the point that Saints could gather and worship in the limestone building that dominated the bluff overlooking the Mississippi. Martha Ann and Joseph F. entered the temple to participate in a special ceremony on 26 January 1846.[73] They, along with their half siblings, in their turn, knelt at the altar and were sealed to their individual parents—for Joseph F. and Martha Ann that was Hyrum and Mary Fielding. This was the beginning of a lifetime connection to temples and temple worship for Martha Ann and Joseph F.[74]

After a temporary lull in the conflict in Hancock County between the Saints and their neighbors, attacks on outlying Latter-day Saint settlements increased steadily in an effort to dislodge the Saints from western Illinois. Church leaders agreed to abandon Nauvoo beginning in the spring of 1846, hoping to provide a window to prepare for the exodus. Brigham Young and a vanguard company of Saints left Nauvoo in February 1846. Latter-day Saints continued to leave the city during the spring and summer. However, by the fall of 1846, pressure for the remaining Saints to depart came to a climax during the “Battle of Nauvoo” in September 1846. Joseph F. remembered the sound of cannon fire as his family camped across the river after fleeing the city.[75]

Martha Ann recalled leaving Nauvoo: “We left our home, just as it was, with all the furniture, in fact everything we owned. The fruit trees were loaded with rosy peaches and apples. We bade goodby to the loved home that reminded us of our beloved father everywhere we turned.”[76]

Eventually, Mary Fielding and her family made their way to the settlement at Winter Quarters in present-day Nebraska on the banks of the Missouri River.[77] The family remained in the area until the spring of 1848. During two successive winters on the banks of the Missouri River, the Saints witnessed more than six hundred men, women, and children die from tuberculosis, cholera, scarlet fever, typhus, and other diseases.[78]

Circumstances were such that when the family moved west with other migrating Saints, nine-year-old Joseph F. and his older half brother John were each responsible for driving one of the family wagons to the Great Salt Lake Valley, the new Latter-day Saint gathering place.[79]

On arriving, the Smiths, like many other pioneer families, slept for a short season in the wagons they had used to make the trek west. They survived that first difficult winter on meager rations of bread, butter, cornmeal, parched corn, and milk. Mary added to their diet a variety of local vegetation, including sego lily bulbs that were boiled, roasted, or made into porridge.

Salt Lake City Cemetery, Smith family plot, photograph by Richard Neitzel Holzapfel, 12 October 2013. Courtesy of the editors. On the left is the original nineteenth-century Mary Fielding Smith grave marker. The second photograph shows modern grave markers for Joseph F.’s children, who were buried next to Mary Fielding, and a new grave maker for Mary Fielding.

Salt Lake City Cemetery, Smith family plot, photograph by Richard Neitzel Holzapfel, 12 October 2013. Courtesy of the editors. On the left is the original nineteenth-century Mary Fielding Smith grave marker. The second photograph shows modern grave markers for Joseph F.’s children, who were buried next to Mary Fielding, and a new grave maker for Mary Fielding.

Once in Utah, Joseph F. worked herding the family stock (including protecting the animals from predators), cutting and hauling wood from the nearby canyons, irrigating, harvesting and threshing the crops on the farm, and tending to a myriad of other duties.[80] He later reflected: “My schooling had been extremely limited. My mother taught me to read and write, by the camp fires, and subsequently by the greater luxury of the primeval tallow candle in the covered wagon and the old log cabin, 10 x 12 feet in size, where first the soles of our feet found rest, after the weary months of travel across the plains.”[81]

Mary continued to nurture and teach her young daughter Martha Ann the skills necessary to survive on the frontier. According to a family tradition, Martha Ann “learned to spin wool, and as a young teenager, she could spin four skeins a day. Mary Fielding also taught Martha Ann to knit, measuring off a specific amount of yarn which Martha had to knit before a meal. As Martha Ann became more skilled, she learned to weave fabric and dye cloth for bedding and clothing. She even learned to weave denim for men’s work clothes.”[82]

Malnourished and exhausted, Mary Fielding died in 1852, leaving Joseph F. and Martha Ann orphaned.[83] She was only fifty-one years old when she fell ill on the way home from a meeting. She was taken to the home of Heber C. Kimball (1801–68) and Vilate Kimball (1806–67), where she died after eight weeks and two days of watchful care from her sister and members of the Kimball and Young families.[84] Heber C. Kimball said, “I have never seen a person in life that had a greater anxiety to live than she had, and there was only one thing she desired to live for, and that was to see to her family; it distressed her to think that she could not see to them; she wept about it. She experienced this anxiety for a month previous to her death, and she wept and prayed that the diseased place might be opened.”[85]

Following Mary Fielding’s death, “Martha Ann, who had just turned eleven, raced from the Kimball home and prayed that she too might die. Joseph F., almost fourteen, fainted.”[86]

Brigham Young’s funeral address was recently discovered, transcribed from the original Pitman shorthand notes, and published. The transcription begins with the following explanation of the setting for this address: “September 23, a company of friends met at President Kimball’s to perform their last duties to Sister Mary Smith who departed this life on Wednesday 22 instant at half past 5 p.m. President Young present. The meeting opened with singing and prayer by President Young.”[87]

Brigham counseled those present, including Joseph F. and Martha Ann, “I can [say] to my friends and immediate connections of Sister Mary, and to the children: pattern after her; abide in her good work, be faithful, keep together. Let this family keep together, let them love each other, let them pray, serve the Lord and live just as long as [they] can upon the earth and carry out the work commenced by their father and their mothers.”[88]

Hannah Grinnels, known by Joseph F. and Martha Ann as “Aunty Grinnells,” who had been living with the family since the death of Jerusha in 1837, took the primary responsibility to care for the younger children.[89] Unfortunately, Hannah died a little more than a year after Mary Fielding, leaving Joseph F. and Martha Ann mourning again. Sources are unclear, but it appears that for a time Joseph F. and Martha Ann moved into the home of their aunt, Mercy Rachel Fielding Thompson (1807–93). The next several years were challenging and difficult for both Joseph F. and Martha Ann.

Two years later in April 1854, fifteen-year-old Joseph F. was sent as a missionary to Hawai‘i, some three thousand miles from his sister. It was during this mission to the Pacific that Joseph F. and Martha Ann began to write to each other—a tradition that spanned six decades.

Notes

[1] The two standard family tributes to Hyrum and Mary Fielding are Pearson H. Corbett, Hyrum Smith, Patriarch (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1963), and Don Cecil Corbett, Mary Fielding Smith: Daughter of Britain (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1966); see also Jeffrey S. O’Driscoll, Hyrum Smith: A Life of Integrity (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2003).

[2] Their circumstance highlights the challenges and opportunities of using reminiscences to help reconstruct Joseph F.’s life; see Stephen C. Taysom, “The Last Memory: Joseph F. Smith and Lieux de Mémoire in Late Nineteenth-Century Mormonism,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 48, no. 3 (Fall 2015): 1–23.

[3] Larry C. Porter, “The Joseph and Lucy Mack Smith Family,” in Mapping Mormonism: An Atlas of Latter-day Saint History, ed. Brandon S. Plewe et al. (Provo, UT: BYU Press, 2012), 14–15.

[4] Richard L. Bushman, Joseph Smith: Rough Stone Rolling (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2005), 20.

[5] Lucy Mack Smith described Hyrum’s role in helping his brother Joseph after his surgery: “Hyrum, who was rather remarkable for his tenderness and sympathy, now desired that he might take my place. As he was a good, trusty boy, we let him do so; and, in order to make the task as easy for him as possible, we laid Joseph upon a low bed, and Hyrum sat beside him, almost day and night, for some considerable length of time, holding the affected part of his leg in his hands, and pressing it between them, so that his afflicted brother might be enabled to endure the pain, which was so excruciating, that he was scarcely able to bear it.” Lucy [Mack] Smith, Biographical Sketches of Joseph Smith the Prophet, and His Progenitors for Many Generations (Liverpool, England: S. W. Richards, 1853), 63.

[6] See O’Driscoll, Hyrum Smith, 10.

[7] Although they were virtually inseparable in life, Joseph and Hyrum were distinct individuals with significant differences in mood and personality; see Stephen C. Taysom’s forthcoming biography, “Like a Fiery Meteor”: The Life of Joseph F. Smith.

[8] Larry C. Porter, “Palmyra–Manchester, New York,” in Encyclopedia of Latter-day Saint History, ed. Arnold K. Garr, Donald Q. Cannon, and Richard O. Cowan (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2000), 889–90.

[9] Don Enders, “Palmyra & Manchester,” in Plewe et al., Mapping Mormonism, 16–17.

[10] O’Driscoll, Hyrum Smith, 32

[11] Smith, Biographical Sketches, 40; see also Jerusha T. Barden Smith’s biography at http://

[12] Corbett, Hyrum Smith, 33.

[13] Smith, Biographical Sketches, 94.

[14] Smith, Biographical Sketches, 94.

[15] Karen Lynn Davidson, David J. Whittaker, Mark Ashurst-McGee, and Richard L. Jensen, eds., Histories, Volume 1: Joseph Smith Histories, 1832–1844, vol. 1 of the Histories series of The Joseph Smith Papers, ed. Dean C. Jessee, Ronald K. Esplin, and Richard Lyman Bushman (Salt Lake City, UT: Church Historian’s Press, 2012), 312–14.

[16] See Terryl Givens, By the Hand of Mormon: The American Scripture That Launched a New World Religion (New York: Oxford University Press, 2002), 40.

[17] The Book of Mormon: Another Testament of Jesus Christ (Salt Lake City, UT: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 2017), vii.

[18] Joseph Fielding Smith, “The Patriarch Hyrum Smith,” Young Woman’s Journal, June 1905, 274–77.

[19] Jerry C. Roundy, Jerusha Barden, 1st Wife of Patriarch Hyrum Smith (Provo, UT: E. H. Peirce 1999), 16.

[20] Karl Ricks Anderson, “The Western Reserve,” in Plewe et al., Mapping Mormonism, 28–29.

[21] Bruce A. Van Orden, “Smith, Hyrum,” in Encyclopedia of Mormonism, ed. Daniel H. Ludlow (New York: Macmillan, 1992), 3:1329–30.

[22] Hyrum Smith papers, 29 May 1832, 19th Century Mormon and Western Manuscripts, BYU.

[23] Corbett, Hyrum Smith, 147.

[24] Corbett, Hyrum Smith, 105.

[25] See Hyrum Smith’s biography at http://

[26] Kirtland High Council Minutebook, 1 March 1835, 186.

[27] Samuel Smith (Kirtland, OH) to Hyrum Smith (Far West, MO), 13 October 1837.

[28] “Obituary,” Elders’ Journal of the Church of the Latter Day Saints, October 1837, 16.

[29] O’Driscoll, Hyrum Smith, 162.

[30] Lovina was ten years old, John four, Hyrum three, Jerusha one, and Sarah less than two weeks old when their mother, Jerusha, died. Hannah’s last name is spelled differently (e.g., Grennels) in various sources; see O’Driscoll, Hyrum Smith, 162.

[31] Mary Fielding was English, spoke with an English accent, and reflected many cultural traits found in nineteenth-century British society; see Taysom, “Like a Fiery Meteor.”

[32] See Susan Arrington Madsen, “Mary Fielding Smith,” in Ludlow, Encyclopedia of Mormonism, 6:1358–59. See also Amanda Hendrix-Komoto, “To Forsake Thy Father and Mother: Mary Fielding Smith and the Familial Politics of Conversion,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 45, no. 3 (Fall 2012): 26–37.

[33] Honeydon is a hamlet located in the Borough of Bedford in Bedfordshire, England.

See Kenneth Mays, “Picturing History: Honeydon, Bedfordshire,” Deseret News, 3 October 2012.

[34] Also known as Rachel Ibbotson. A recent history of Mary Fielding’s early life is found in Jay Parry, “Mary Fielding Smith,” Women of Faith in the Latter Days, Volume 1: 1775–1820, ed. Richard E. Turley Jr. and Brittany A. Chapman (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2011), 376–88.

[35] Mary Fielding’s brother, Reverend James Fielding, was a Methodist minister, as were the husbands of her two sisters in England.

[36] As a tutor, Mary Fielding had already become well acquainted with the Smith family before Hyrum’s wife had passed away in October 1837. After Jerusha died, Joseph Smith “informed Hyrum that it was the will of the Lord that he marries again and take as a wife a young English convert, Mary Fielding by name.” Joseph Fielding Smith, The Life of Joseph F. Smith: Sixth President of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1938), 120. Hyrum, according to a family tradition, did not want to simply make this a matter of convenience, so he decided to court Mary in such a way that “his gentlemanly and courtly proposal . . . provided the basis of lasting affection between them.” Corbett, Mary Fielding Smith, 45.

[37] Mary Fielding struggled as a stepmother. In a letter written to Hyrum, she signed, “your faithful companion and friend but unhappy stepmother M. Smith.” Mary Fielding Smith to Hyrum Smith, 14 September 1842.

Corbett, Mary Fielding Smith, 45.

[38] Alexander L. Baugh, “Settling Northern Missouri,” in Plewe et al., Mapping Mormonism, 48–49.

[39] Governor Boggs was willing to call out state militia forces to end this conflict. In fact, he had engaged in two other military conflicts during this period. The first was between Native peoples and the state of Missouri in 1838 and a second conflict with the state of Iowa in 1839. See Richard Neitzel Holzapfel, “Crossing Borders: Lilburn Boggs and the 1839 Missouri–Iowa War,” Mormon Historical Association annual meeting, St. Louis, MO, 2 June 2017, forthcoming in BYU Studies Quarterly.

[40] The spelling of Jacob Hawn’s last name was thought to be have been “Haun” until recent discoveries made it clear that it had been misspelled in modern sources. See Alexander L. Baugh, “Jacob Hawn and the Hawn’s Mill Massacre: Missouri Millwright and Oregon Pioneer,” Mormon Historical Studies 11, no. 1 (Spring 2010): 4.

[41] Sean Cannon, “The Mormon–Missouri War,” in Plewe et al., Mapping Mormonism, 50–51.

[42] Joseph Smith to Emma Smith, 4 April 1839, Joseph Smith Papers, Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Yale University. See also “Letter to Emma Smith, 4 April 1839,” p. [1], The Joseph Smith Papers, http://

[43] Stephen C. Taysom suggests even though Joseph F. was an infant during this period, Missouri cast a long and traumatizing shadow during the rest of his life. Mobs were real and dangerous; see Taysom, “Last Memory,” 9–10.

[44] See Hyrum Smith to Mary Fielding Smith, 20 March 1839; Hyrum Smith to Mary Fielding Smith, 30 March 1839; and Mary Fielding Smith to Hyrum Smith, 11 April 1839.

[45] See Alexander L. Baugh, “Was Joseph F. Smith Blessed by His Father Hyrum Smith in Liberty Jail?,” Mormon Historical Studies 4, no. 1 (Spring 2003): 101–5.

[46] Donald Q. Cannon and Brandon S. Plewe, “Commerce, Illinois,” in Plewe et al., Mapping Mormonism, 52–53.

[47] Hyrum Smith, letter, Nauvoo, Hancock County, Illinois, to Joseph Smith and Elias Higbee, Washington DC, 2 January 1840, in Joseph Smith Letterbook 2, pp. 91–94, handwriting of Howard Coray.

[48] See Taysom, “Like a Fiery Meteor.”

[49] Brandon S. Plewe and Donald Q. Cannon, “Buying Nauvoo”; and Donald Q. Cannon and Brandon S. Plewe, “Building Nauvoo,” in Plewe et al., Mapping Mormonism, 54–55, 56–57.

[50] Kenneth W. Godfrey, “Conflict in Hancock County,” in Plewe et al., Mapping Mormonism, 62–63; see also David Grimsted, American Mobbing, 1828–1861: Toward Civil War (New York: Oxford University Press, 2003), 3.

[51] Andrew H. Hedges, Alex D. Smith, and Richard Lloyd Anderson, eds., Journals, Volume 2: December 1841–April 1843, vol. 2 of the Journals series of The Joseph Smith Papers, ed. Dean C. Jessee, Ronald K. Esplin, and Richard Lyman Bushman (Salt Lake City, UT: Church Historian’s Press, 2010), 53–54n198.

[52] Andrew H. Hedges, Alex D. Smith, and Brent M. Rogers, eds., Journals, Volume 3: May 1843–June 1844, vol. 3 of the Journals series of The Joseph Smith Papers, ed. Ronald K. Esplin and Matthew J. Grow (Salt Lake City, UT: Church Historian’s Press, 2015), 24n87.

[53] Bathsheba W. Smith, “Testimony,” in “Respondent’s Testimony, Temple Lot Case,” 1892, 302, Community of Christ, Library-Archives, Independence, MO.

[54] Martha Ann to posterity, 22 March 1881. Because Martha Ann was between four and five years old when these ordinances were preformed, one should be cautious when referring to reminiscences of events the occurred decades earlier.

[55] See Kathryn M. Daynes, More Wives Than One: Transformation of the Mormon Marriage System, 1840–1910 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2001).

[56] Mercy R. Thompson, Affidavit, Salt Lake County, Utah Territory, 19 June 1869, in Joseph F. Smith, Affidavits about Celestial Marriage, 1:34.

[57] Hedges, Smith, and Rogers, Journals, Volume 3, xxii–xxiii.

[58] See Dallin H. Oaks and Marvin S. Hill, Carthage Conspiracy: The Trial of the Accused Assassins of Joseph Smith (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1975).

[59] Davis Bitton, The Martyrdom Remembered: A One-Hundred-Fifty-Year Perspective on the Assassination of Joseph Smith (Salt Lake City, UT: Aspen Books, 1994), xvi. Joseph Smith was the first US presidential candidate to be assassinated. Robert F. Kennedy, who was shot in June 1968, is the most famous.

[60] See “Extra,” Nauvoo Neighbor, 30 June 1844, 1; and “Extra,” Nauvoo Neighbor, 2 July 1844, 1.

[61] Preston Nibley, The Presidents of the Church (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1959), 228.

[62] Joseph F. Smith, “Boyhood Recollections of President Joseph F. Smith,” Utah Genealogical and Historical Magazine, April 1916, 57–58.

[63] B. W. Richmond, “The Prophet’s Death,” Deseret Evening News, 27 December 1875, 3.

[64] Martha Ann to Joanna Spears, 1920.

[65] See Preston Nibley, The Presidents of the Church (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book Company, 1941), 229.

[66] Scott G. Kenney, “Before the Beard: Trials of the Young Joseph F. Smith,” Sunstone 120 (November 2001): 22.

[67] See Taysom, “Like a Fiery Meteor.”

[68] See, for example, Joseph F., journal, 27 April 1860.

[69] Renee Horton, “Reminiscence,” as quoted in Ruth Mae Harris, Martha Ann, Daughter of Hyrum and Mary Fielding Smith (Orem, UT: published by the author, 2002), 131.

[70] Martha Ann to posterity, 22 March 1881.

[71] Sometime after Samuel’s death, rumors began to circulate that he had been poisoned by Hosea Stout on orders from Willard Richards; see Dean L. Jarman and Kyle R. Walker, “Samuel Harrison Smith,” in United by Faith: The Joseph Sr. and Lucy Mack Smith Family (American Fork, UT: Covenant Communications, 2005), 234–35. See also D. Michael Quinn, The Mormon Hierarchy: Origins of Power (Salt Lake City, UT: Signature Books, 1994), 152–53; and William Smith, “Mormonism: A Letter from William Smith, Brother of Joseph the Prophet,” New York Tribune, 19 May 1857, 3. William’s letter was quickly debunked by Samuel Smith’s son, Samuel H. B. Smith; see “Letter to the Editor,” The Mormon, 6 June 1857. Although the accusation was generally not taken seriously by the members of the family in Utah, the rumor may be part of the basis for the underlying tension found in some of Joseph F.’s letters to his cousin Josephine Donna Smith, the daughter of Don Carlos Smith (she was known as Ina Coolbrith during most of her adult life). Additionally, much of the tensions between Joseph F. and Coolbrith also developed over her rejection of the Church for what Joseph F. saw as ultimately more worldly pursuits and culture. For one interpretation of their relationship, see Aleta George, Ina Coolbrith: The Bittersweet Song of California’s First Poet Laureate (Suisun City, CA: Shifting Plates, 2015).

[72] Mary Fielding filed a petition to the county court to grant her permission as guardian of John, Jerusha, Sarah, Joseph F., and Martha Ann Smith to sell listed Nauvoo properties for the children’s support and education. The petition was signed by Mary Fielding Smith and certified by Hancock County justice of the peace Isaac Higbee and filed by Hancock County circuit court clerk D. E. Head, 18 May 1846. See “Mary Smith, Petition, 1846 April 10, Hancock [Ill.: County], Circuit Court.”

[73] Devery S. Anderson and Gary James Bergera, eds., The Nauvoo Endowment Companies, 1845–1846: A Documentary History (Salt Lake City, UT: Signature Books, 2005), 497.

[74] Eventually Martha Ann was endowed, completed family history work, performed proxy ordinances for family members, and spent her adult life making temple clothing for the living and dead. Joseph F. was endowed, worked with the temple records in the Historian’s Office, became an ordinance worker in the Salt Lake Endowment House, and served as the president of the Salt Lake Temple.

[75] Smith, “Boyhood Recollections,” 58–59.

[76] As cited in Sarah Harris Passey, “Martha Ann Smith Harris” (unpublished manuscript in editors’ possession, courtesy of Carole Call King, granddaughter of Sarah Harris Passey).

[77] Gail Geo. Holmes, “The Middle Missouri Valley,” in Plewe et al., Mapping Mormonism, 76–77.

[78] See Conrey Bryson, Winter Quarters (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1986), 165.

[79] See Joseph F. Smith, “Recollections,” Juvenile Instructor, 27 May 1871, 87–88; 10 June 1871, 91; and 24 June 1871, 98–99.

[80] Andrew Jenson, “The Twelve Apostles: Joseph Fielding Smith,” Historical Record 6, nos. 3–5 (May 1887): 184. Additional reminiscences are found in several sources, including “Reminiscences, 1838–circa 1848,” labeled as “Jos. F. Smith’s Journal commencing 13 Nov. 1838,” circa 1890s, CHL. See also Smith, “Boyhood Recollections,” 52–69.

[81] Jenson, “Twelve Apostles,” 184.

[82] Harris, Martha Ann, 81–82.

[83] “Died,” Deseret Weekly News, 11 December 1852, 3; Edward W. Tullidge, Women of Mormondom (New York: Tullidge & Crandall, 1877), 249; and Andrew Jenson, Latter-day Saint Biographical Encyclopedia (Salt Lake City, UT: Andrew Jenson History Co., 1914), 2:710–11.

[84] Following the deaths of Joseph and Hyrum Smith, many of their plural wives were married to other Church leaders in an effort to support and assist them. Heber C. Kimball married Mary as a plural wife in 1844, but they never lived together in a marriage relationship. However, Heber C. and his wife Vilate Kimball were close friends; see “U.S. and International Marriage Records, 1560–1900,” database, Ancestry.com (http://

[85] Heber C. Kimball, “Funeral Address,” 23 September 1852, in Journal of Discourses (London: Latter-day Saints’ Book Depot, 1854–86), 1:246.

[86] Harris, Martha Ann, 83. A number of printed sources attribute a dream about Hyrum and his wife, dated circa 1852 and found in the Joseph F. Smith Papers (CHL), to Martha Ann. Church History Library staff members believe the dream is more likely attributed to Lovina Smith Walker, Joseph F. and Martha Ann’s oldest half sister.

[87] Brigham Young, “Sermon at the Funeral of Mary Fielding Smith,” 23 September 1852, CHL.

[88] Young, “Sermon at the Funeral of Mary Fielding Smith.”

[89] See Richard P. Harris, “Martha Ann Smith Harris,” Relief Society Magazine, January 1924, 14.