Introduction and Historiography

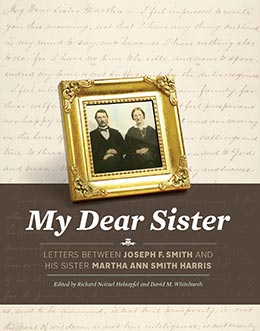

Richard Neitzel Holzapfel and David M. Whitchurch, "Introduction," in My Dear Sister: Letters Between Joseph F. Smith and His Sister Martha Ann Smith Harris, ed. Richard Neitzel Holzapfel and David M. Whitchurch (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2019), xi–xl.

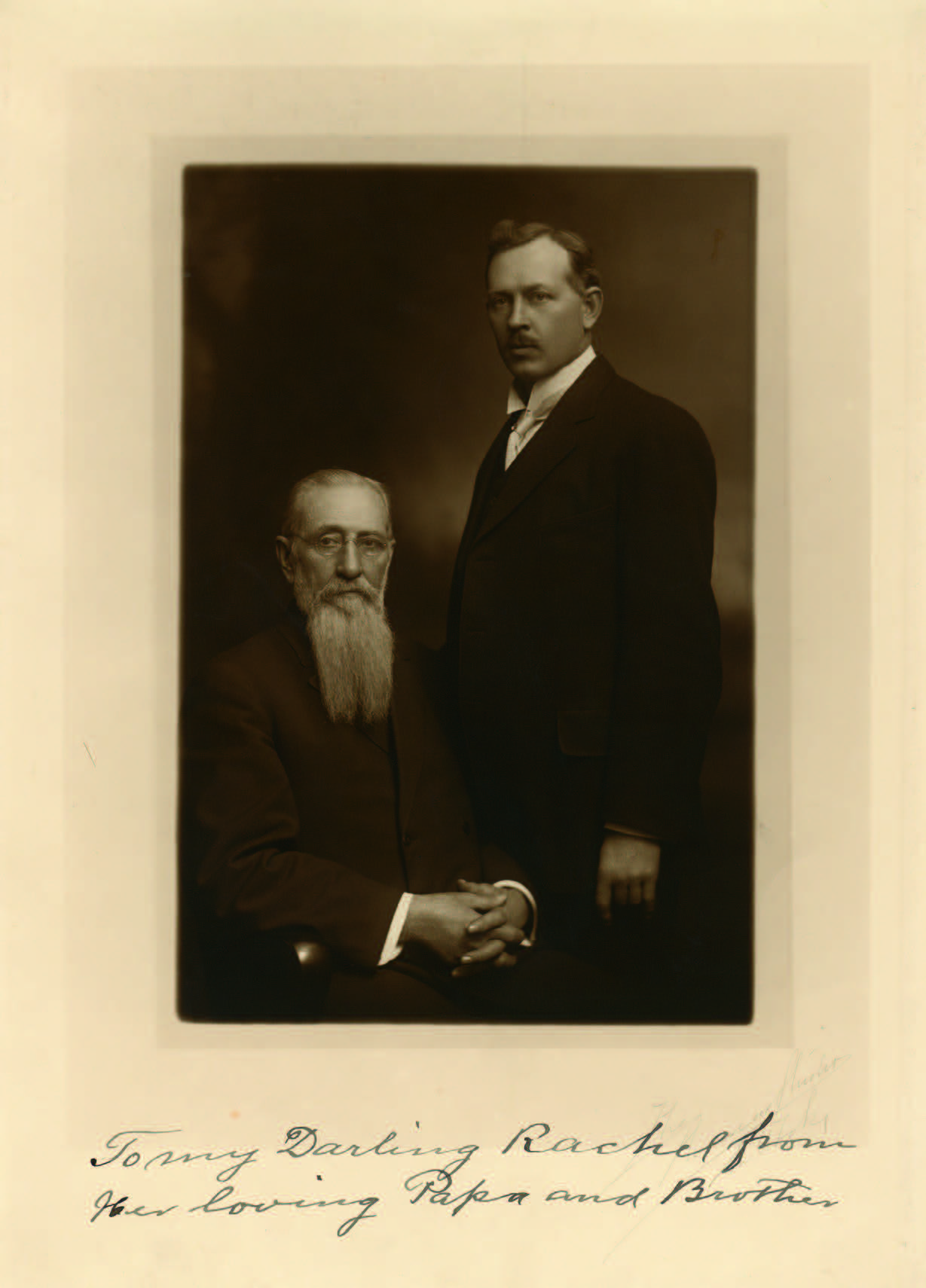

Joseph F. Smith and his son and biographer, Joseph Fielding Smith, ca. 1915. Courtesy of CHL.

Joseph F. Smith and his son and biographer, Joseph Fielding Smith, ca. 1915. Courtesy of CHL.

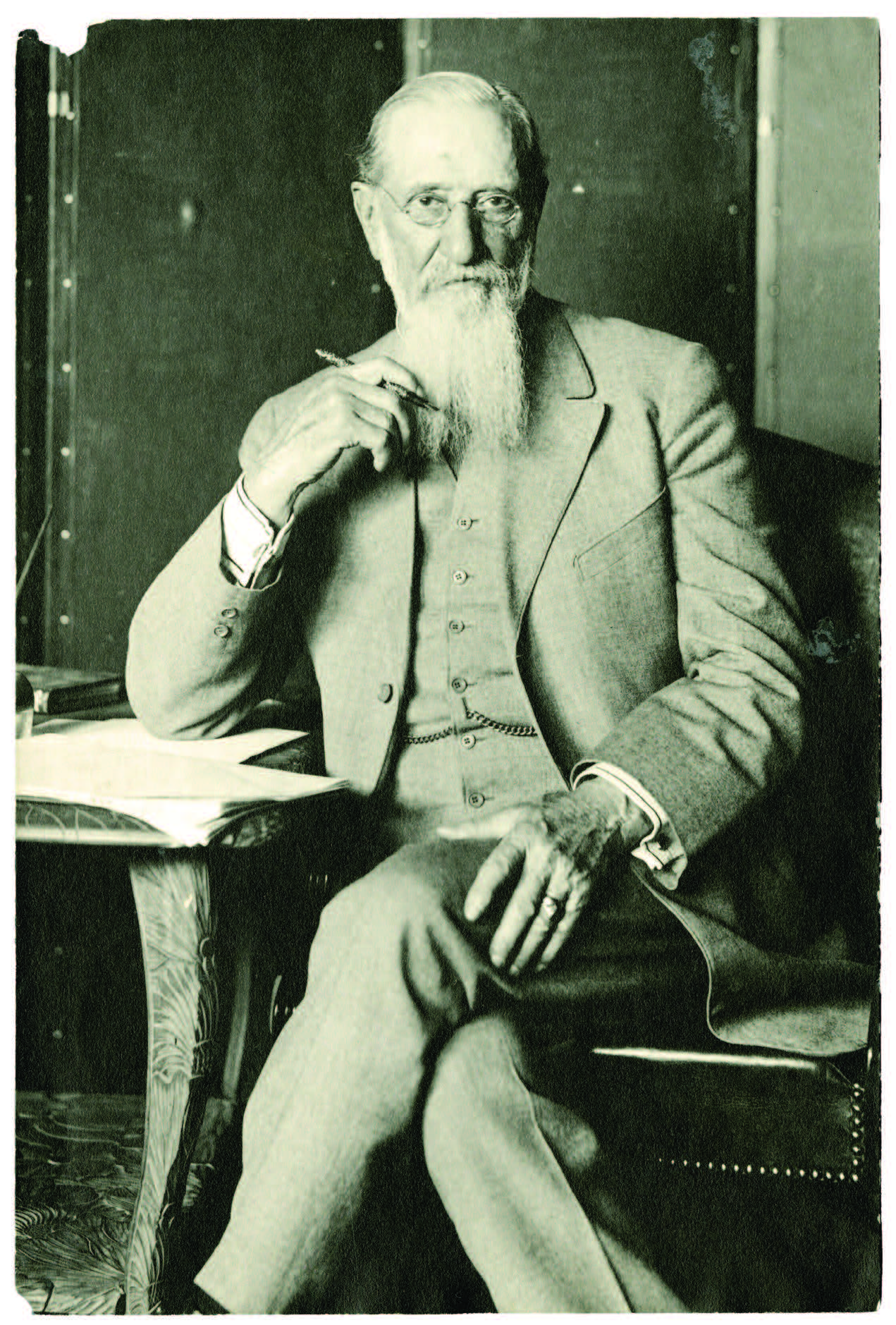

It has been eighty years since The Life of Joseph F. Smith: Sixth President of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints was published in 1938.[1] Written by his son Joseph Fielding Smith (1876–1972), this biography became an instant classic and contained source material unavailable to the public. Not only did Joseph Fielding know his father as an intimate family member, but he also worked closely with him before and after his mission as a young man (1899–1901) and then observed his father in another small circle as he served for nine years in the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles during the time his father was the President of the Church. Finally, Joseph Fielding Smith had complete access to a rich collection of Joseph F. Smith papers, including diaries, letters, sermons, reminiscences, and other related Church material preserved in the archives at Church headquarters, as he prepared his father’s biography.

In the past several decades, historians have made significant advances in reconstructing the story of the Church and the lives of its leaders, including the life of Joseph F.[2] Using primary source material at various institutions, especially at the Church History Library, these historians have helped Latter-day Saints appreciate, understand, and expand their understanding of the remarkable story of God’s people, human and fallible, trying to do the will of a perfect God—sometimes failing and sometimes succeeding in their efforts.

Some of Joseph F.’s sources became available in 2003 with the creation of Selected Collections from the Archives of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.[3] Since then, the Church History Library has continued to digitalize and preserve electronically additional sources. (Note that because all primary sources cited in the footnotes herein reside in the Church History Library unless otherwise noted, for space reasons the source citations dispense with listing that repository.)

Joseph F. has been the subject of these recent efforts. For example, Hyrum M. Smith III and Scott G. Kenney published in 1981 a collection of letters written by Joseph F. to his missionary sons.[4] Kenney followed up with an interpretive essay on the trials of the young Joseph F.[5] Ten years later, Nathaniel R. Ricks edited and published some of Joseph F. Smith’s first mission journals (1856–57).[6] In 2012 David M. Whitchurch and Mallory Hales Perry published a study highlighting a letter from Joseph F. to Susa Young Gates.[7]

A symposium focused on Joseph F. Smith’s life and ministry was sponsored by the BYU Department of Church History and Doctrine, BYU Religious Studies Center, and the Church History Library in 2012. The proceedings, Joseph F. Smith: Reflections on the Man and His Times, were published the following year.[8]

Recently, historian Stephen C. Taysom has published important interpretive essays on Joseph F.’s life as he prepares a new fresh and comprehensive biography of Joseph F., tentatively titled “Like a Fiery Meteor”: The Life of Joseph F. Smith. This work will become the definitive biography for years to come.

However, even with the primary sources now available and the excellent interpretive essays and books being written about Joseph F., we will never really be able to say we are in a position to reconstruct Joseph F.’s life in a way that would allow us to know him as those who lived with him knew him. As Taysom has observed, “Very early in my research it became clear to me that I was never going to get the ‘real’ JFS. I was never going to find the guy who lived and walked and ate and rolled his eyes. Most of the things that made him the fluid human being who completely inhabited every second of his 80 years on earth are gone. What I am dealing with is the version of JFS that is left behind in the archival traces of his life.”[9] To underscore this point, Taysom adds, “Imagine if you suddenly died tomorrow and a stranger had to reconstruct your life only from things you had written or things that others had written about you. And not everything that was ever written, just those things that survived the ravages of time and nature and that people happened to save. Those sources would reveal a lot about you, but they would be of limited assistance in getting at you as a living, vital personality.”[10]

Nevertheless, collecting the fragmentary sources and carefully examining them in context, to “see through a glass darkly,” is still worthy of effort.[11] Joseph F.’s life belongs to the Latter-day Saints, not just his descendants, because Joseph F. dedicated his life and ministry to his people.

Letters as Sources

When reconstructing a life or preparing a historical study, historians utilize many types of primary resources, including letters, diaries, and autobiographical reminiscences. Each type is a personal window into past lives and provides historians with particular opportunities and challenges. An autobiographical reminiscence is easily discerned as being distinct and different from a diary or letter because generally a long period of reflection has occurred before it was created. This long period provides nuanced interpretations of the past by the author, sometimes reconstructing the past in a way that does not always match the contemporary record of events.

Although diaries and letters are often contemporary accounts of one’s life, they are more different from each other than one might recognize at first. For example, diaries are a more recent form, while letters are a much older form (think of the Apostle Paul’s letters in the New Testament). Further, they each had their own purpose; letters were meant to be part of a dialogue between two or more people, while diaries were written to oneself and form a kind of self-dialogue or self-reflection.

Historians have discovered a treasure trove of information in Joseph F.’s diaries, some thirty-six volumes housed in the Church History Library.[12] Joseph F. presumably began keeping a diary at the beginning of his first mission—a mission to Hawai‘i in 1854. Unfortunately, two volumes beginning with his arrival in September 1854 to the end of 1855 were destroyed in a fire at the mission headquarters in June 1856. Those covering 1856–57 survived and were published in 2011.[13]

The Nature of Letters

There were well-established conventions regarding nineteenth-century letters, including how they should be written, what they should and should not contain, how they were to be read, and how they were to be sent. Scholars often classify letters into distinctive categories such as administrative, business, diplomatic, personal, and travel. Joseph F.’s letters to his sister may bridge several categories but are decidedly personal for the most part.

Nineteenth-century grammar, spelling, usage, and vocabulary are in many ways much different from today’s literary conventions. People often spelled a word, particularly proper nouns, the way they heard them, and they often spelled words differently in the same letter.[14] Written American English was still fluid in the second half of the nineteenth century.

Letter Collections

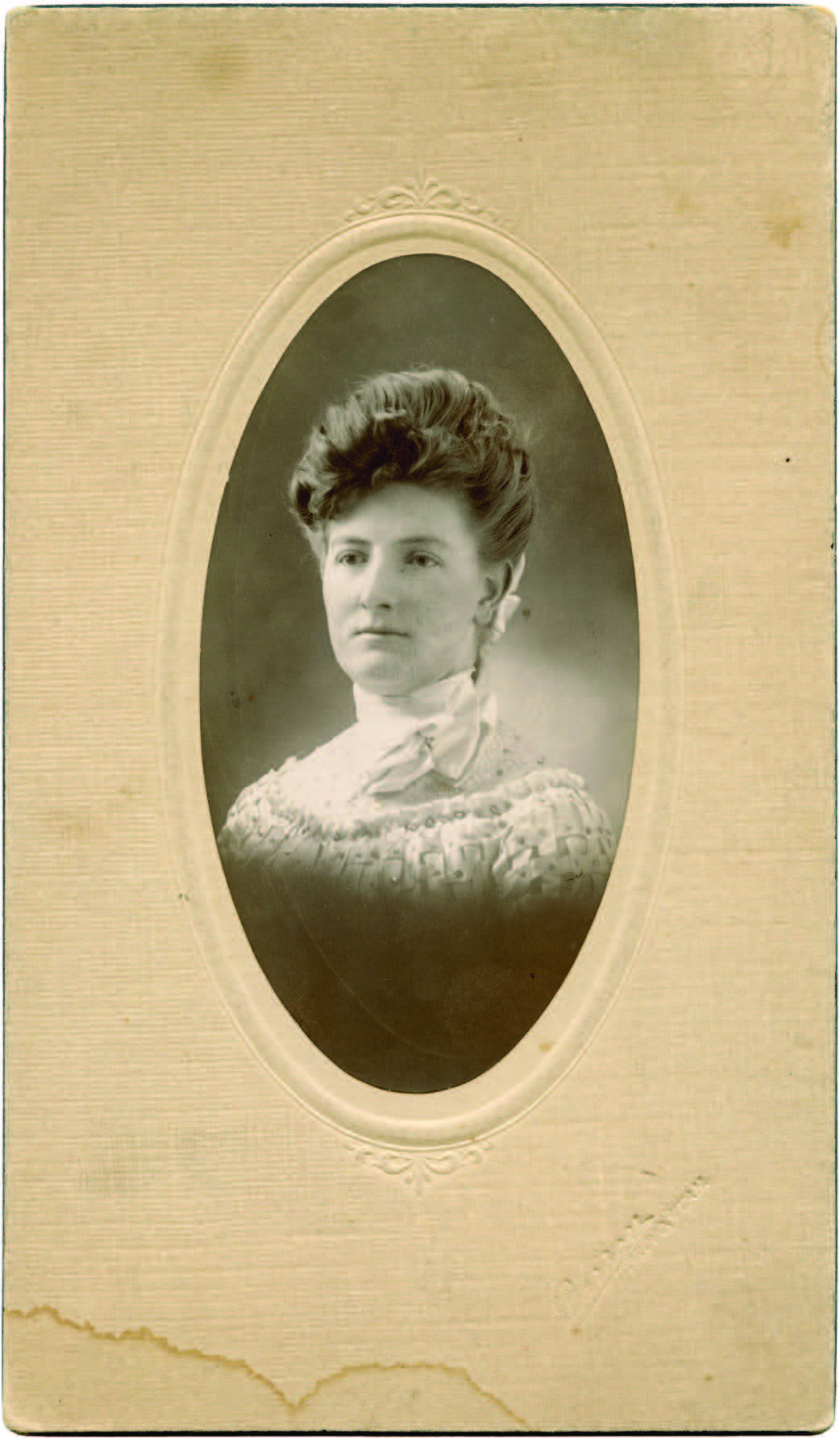

Sarah Lovina Harris Passey, ca 1906–7. Sarah was the youngest daughter of Martha Ann and the one who had preserved her mother’s letters, including those sent to Martha Ann by Joseph F. Courtesy of Carole Call King.

Sarah Lovina Harris Passey, ca 1906–7. Sarah was the youngest daughter of Martha Ann and the one who had preserved her mother’s letters, including those sent to Martha Ann by Joseph F. Courtesy of Carole Call King.

Many important letter collections have been published in the recent past. For example, the annotated letters of John Adams, second president of the United States, are published in nine volumes.[15] Latter-day Saints were introduced to letters by Brigham Young (1801–77) to some of his sons in an important collection entitled My Dear Son: Letters of Brigham Young to His Sons.[16] The letters between Ellen Spencer Clawson of Salt Lake City and Ellen Pratt McGary of San Bernardino in the 1850s concern two women who had been childhood friends in Nauvoo, Illinois, and crossed the plains together to Utah in the 1840s. This fascinating correspondence was published in Dear Ellen: Two Mormon Women and Their Letters.[17]

As already noted, in 1981 Hyrum M. Smith III and Scott G. Kenney, two of Joseph F.’s descendants, published a selection of letters written to his sons while they served full-time missions.[18] Two other collections, Post-Manifesto Polygamy: The 1899–1904 Correspondence of Helen, Owen, and Avery Woodruff and In the Whirlpool: The Pre-Manifesto Letters of President Wilford Woodruff to the William Atkin Family, 1885–1890, remind us of the importance of letters as primary sources in providing additional depth and breadth to the Latter-day Saint story.[19]

Joseph F. and Martha Ann Smith Harris Letter Collection

Carole Call King did not realize the treasure she inherited when her father, Anson B. Call Jr. (1900–93), passed away.[20] Busy with the funeral and other family demands, she overlooked the contents of one box. Left unnoticed on a closet shelf for some time, it caught her attention one day as she was putting away the vacuum. In the bottom of the box, underneath her mother’s chiffon wedding dress, she found three small, long, narrow boxes neatly wrapped in tissue paper. On them her grandmother Sarah Lovina Harris Passey (1883–1961) had written in her own hand the words “Letters to mother.”[21]

King opened the box and discovered inside nearly a hundred original letters written by Joseph F. Smith, the sixth President of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Joseph F., “for by that name he was affectionately called,” had addressed and sent them to his younger sister Martha Ann Smith Harris (1841–1923), King’s great-grandmother.[22]

Richard Neitzel Holzapfel, a professor from Brigham Young University, contacted King after hearing about an 1854 letter that she had found in one of the boxes that included a lock of Joseph F.’s hair in the envelope. In the course of their conversation, Holzapfel learned about the other letters and arranged to visit with her the following day at her home in Mountain Green, Morgan County, Utah. King graciously showed him the collection of handwritten letters, many of which were inside their original envelopes. During their conversation, King gave Professor Holzapfel permission to copy, transcribe, and publish this important collection of personal letters between Joseph F. and Martha Ann.

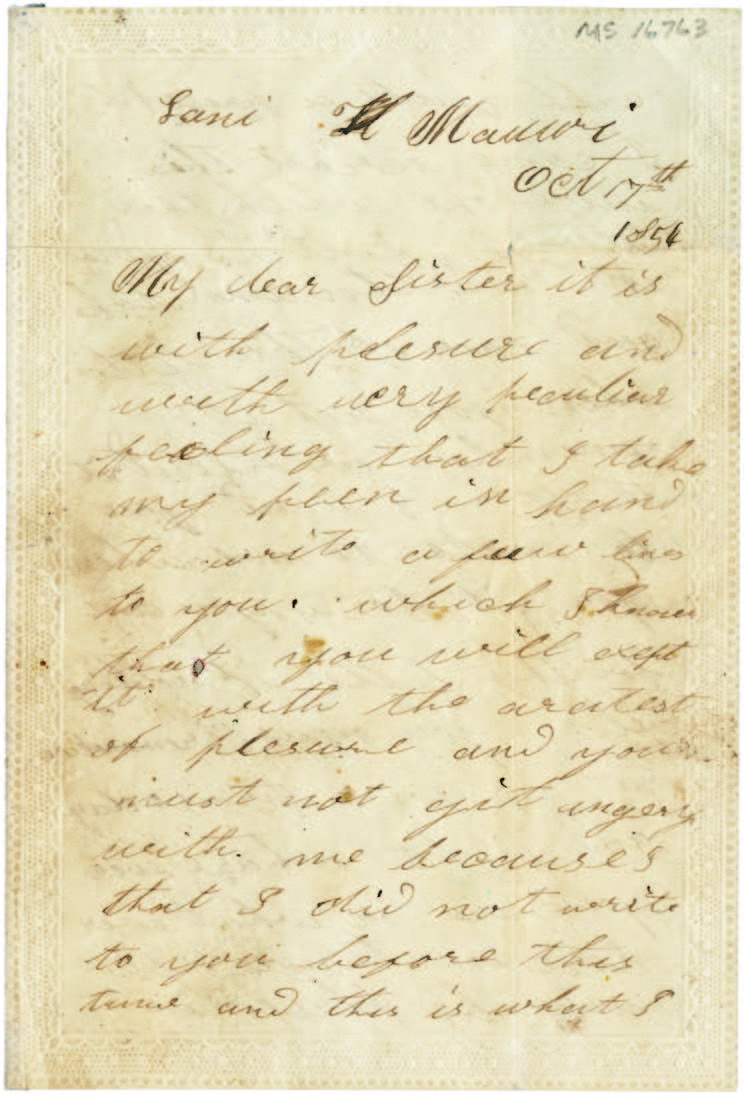

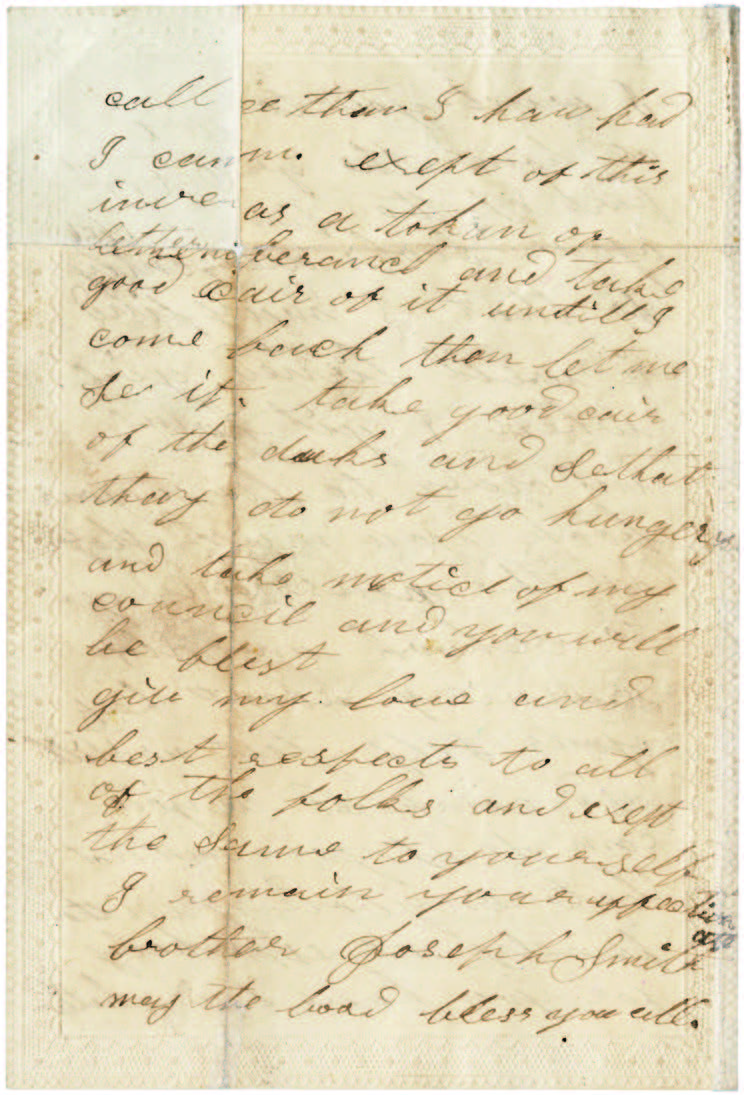

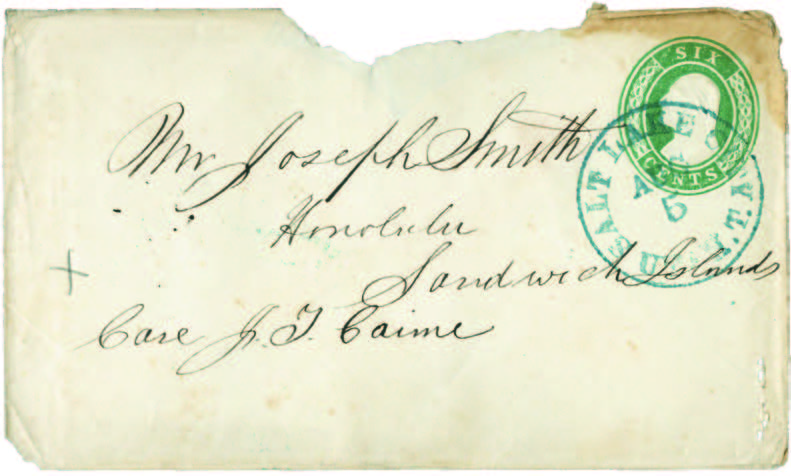

Letter from Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 17 October 1854, with envelope and lock of hair. Courtesy of CHL. This the first known extant letter in the collection written to Martha Ann from Hawai‘i. This letter was in possession of Carole Call King, along with the other letters her grandmother had preserved. King eventually donated the collection to the CHL.

Letter from Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 17 October 1854, with envelope and lock of hair. Courtesy of CHL. This the first known extant letter in the collection written to Martha Ann from Hawai‘i. This letter was in possession of Carole Call King, along with the other letters her grandmother had preserved. King eventually donated the collection to the CHL.

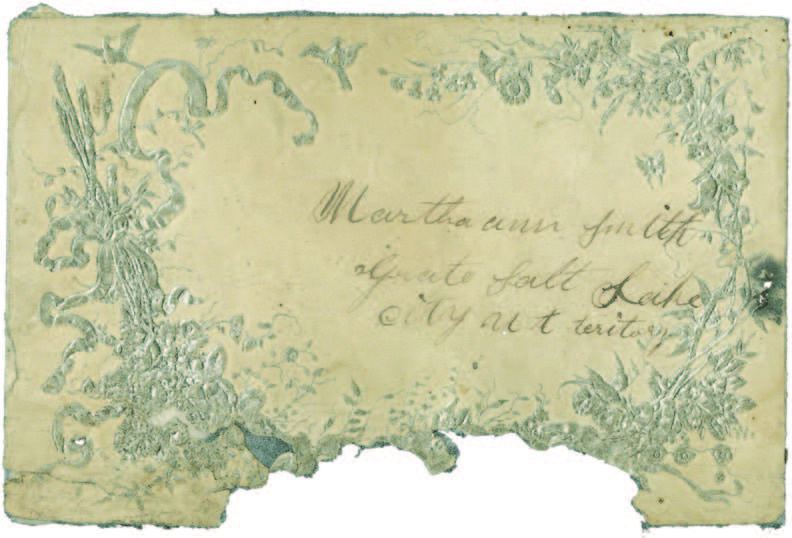

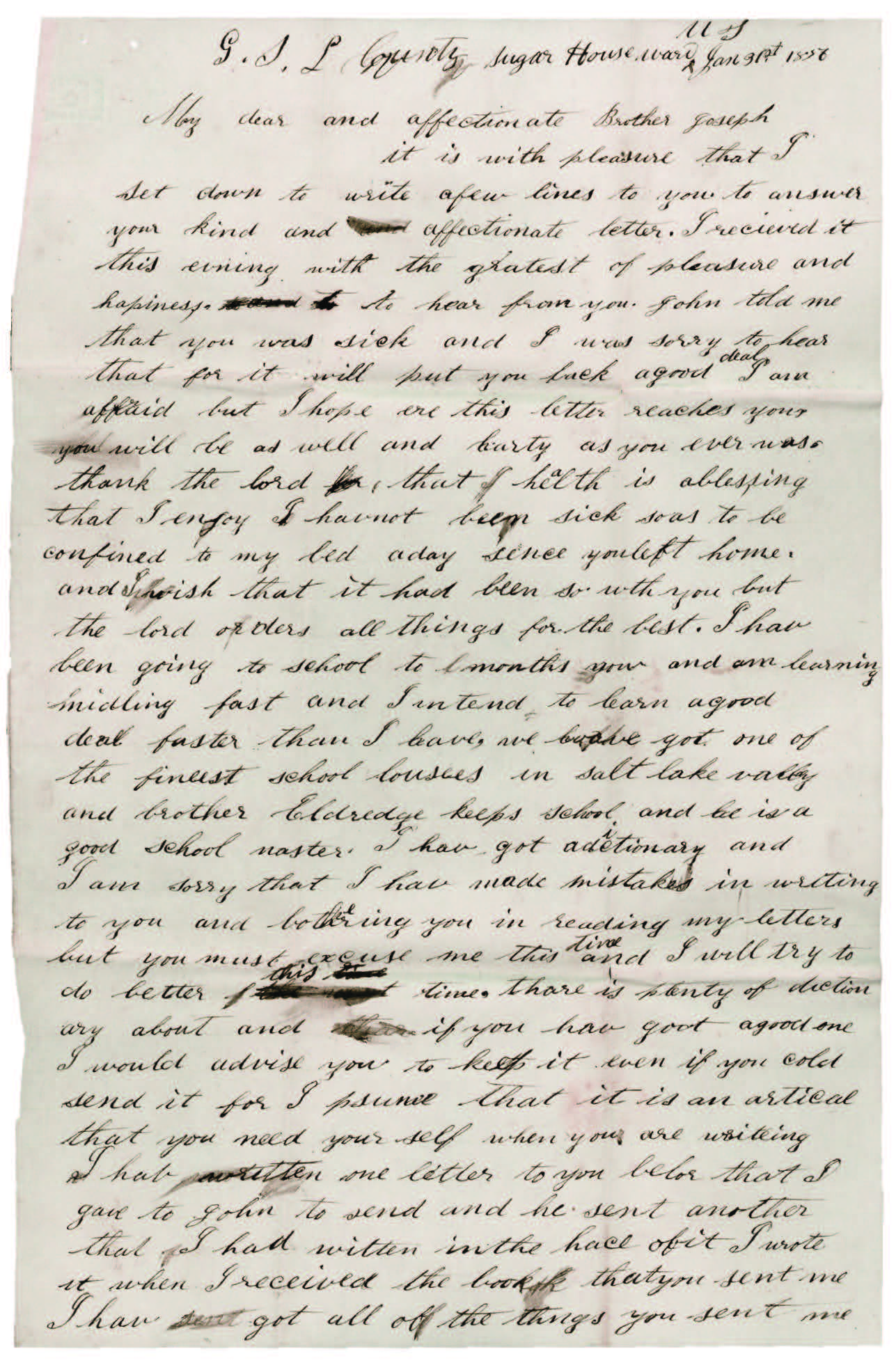

Letter from Martha Ann to Joseph F., 31 January 1856. Courtesy of CHL. This is Martha Ann’s first known surviving letter to her brother.

Letter from Martha Ann to Joseph F., 31 January 1856. Courtesy of CHL. This is Martha Ann’s first known surviving letter to her brother.

In the months that followed, Holzapfel invited a colleague, BYU professor David M. Whitchurch, to join the project. Whitchurch oversaw the challenging transcription effort, producing summaries of each letter along with a biographic register. At the same time, Holzapfel began searching in several institutional repositories for additional letters, researching material for historical summaries for each decade represented in the letter collection, and gathering information to be used to annotate each letter to help readers contextualize the documents.

Another important development occurred when Carole Call King donated the collection of letters and envelopes to the Church History Library in Salt Lake City.[23] In response to Carole Call King’s generosity, the Church provided Holzapfel and Whitchurch copies of Martha Ann’s letters to Joseph F. housed in their collection, which had previously been closed to researchers. Additional letters were donated to the Church History Library by other Harris family members.[24]

Holzapfel and Whitchurch searched the Church History Library and the libraries at Brigham Young University, the University of Utah, and the Utah State Historical Society looking for additional letters. Eventually, they discovered nineteen of Joseph F.’s letterpress copybooks at the Church History Library, two in private possession, and one at the University of Utah.[25]

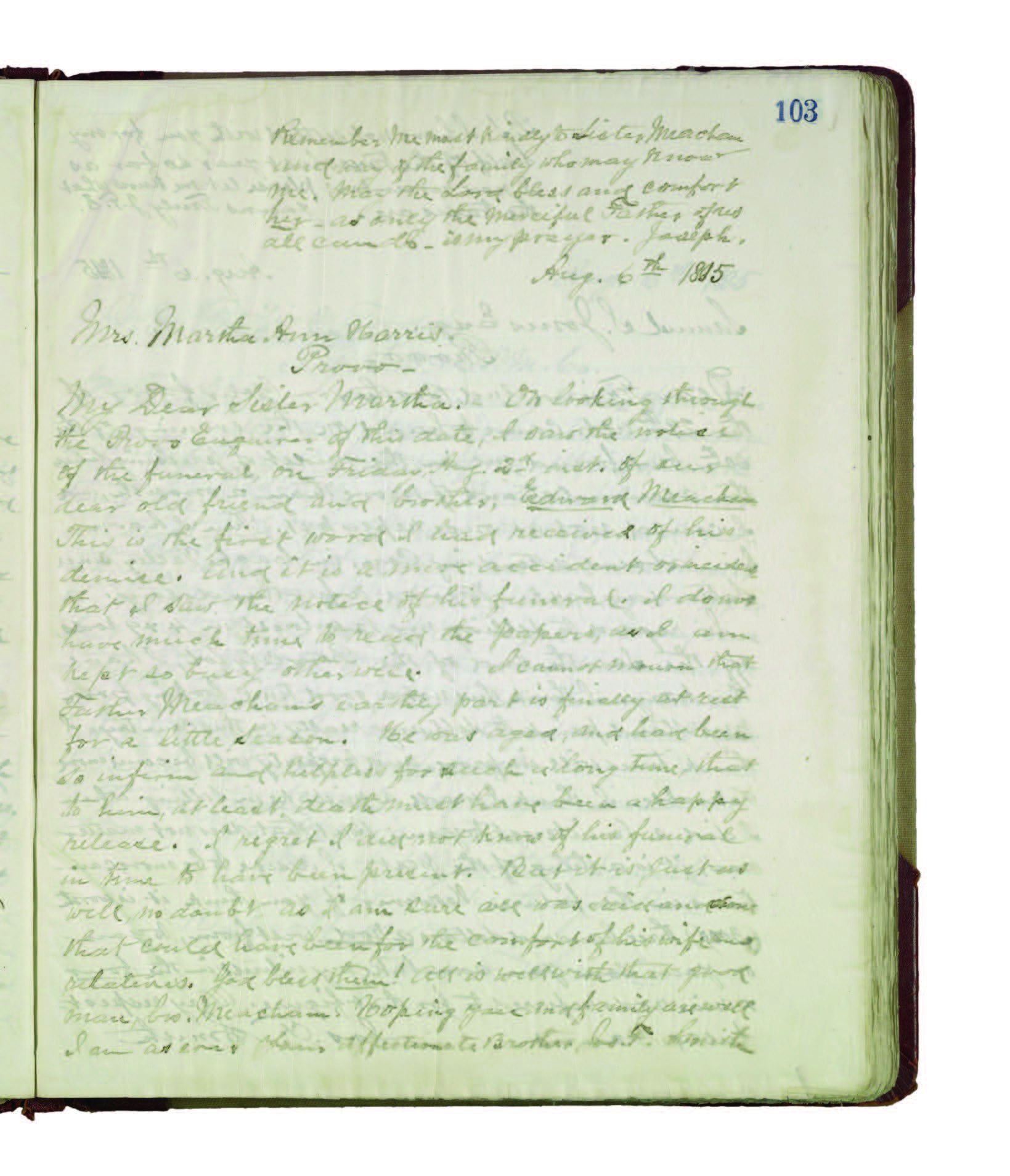

Copies of sixty-nine letters are preserved only in Joseph F.’s letterpress copybooks, the originals not having survived.[26] Additionally, one incomplete original Joseph F. letter was handed down in the family. Fortunately, a complete copy of that letter is found in one of the copybooks.[27]

The letterpress copybooks offer clues to help date letters when questions arise about the exact date of composition. In cases where original letters are damaged by tears or holes, copies from the letterpress copybooks have made it possible to produce more complete and accurate transcriptions.

Letterpress Copybooks

Historians Barbara Rhodes and William Wells Streeter observe, “Letterpress copybooks are an early type of document copying process. They were commonly used in office environments throughout the 19th century.”[28] Rhodes and Streeter continue:

The historic copy press process involved the transfer of ink on a freshly written document to a moistened sheet of copying paper through the use of direct contact and pressure. The books were manufactured specifically for this purpose and would have been purchased blank. The user would have written a letter on a regular sheet of writing paper but with specially formulated copying ink. A sheet of copying paper would have been dampened and the original document laid onto the damp sheet. The book would be closed and put into a copy press, transferring the ink onto the copying book page. Because the soluble copying ink was transferred directly, it left a mirror image print to be read from the verso of the thin paper.[29]

Professor JoAnne Yates of MIT’s Sloan School of Management adds: “These letter presses were used by some individuals and businessmen in the first half of the nineteenth century, but they only came into general use in the second half of the century. A letter press reduced the labor cost, both by decreasing copying time and by allowing an office boy to do the copying once performed by a more expensive clerk. At the same time, it eliminated the danger of miscopying. Copies were now facsimiles of the letter sent, down to the signature.”[30]

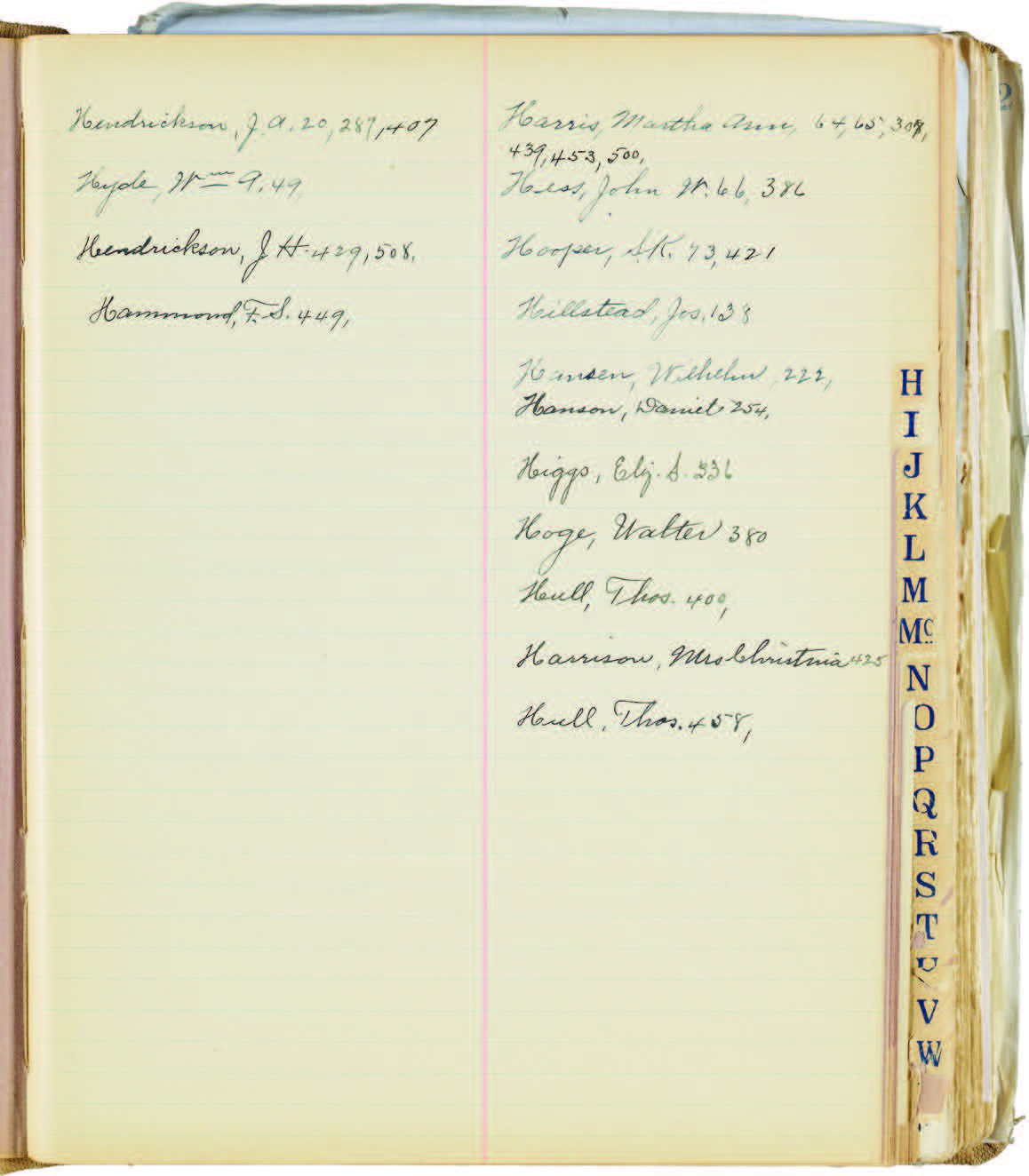

Generally, letterpress copybooks begin with an index allowing the letters to be located rather quickly. However, owners or clerks sometimes missed letters during the indexing process, and as a result a page-by-page search was required for this project in order to find all of Joseph F.’s letters to Martha Ann that had been copied into the letterpress copybooks.

Joseph F. Smith letterpress copybook, 23 November 1899 through 3 February 1902. Courtesy of CHL. It is open to the index section highlighting the letter H. A clerk identified six letters written to Martha Ann in this copybook.

Joseph F. Smith letterpress copybook, 23 November 1899 through 3 February 1902. Courtesy of CHL. It is open to the index section highlighting the letter H. A clerk identified six letters written to Martha Ann in this copybook.

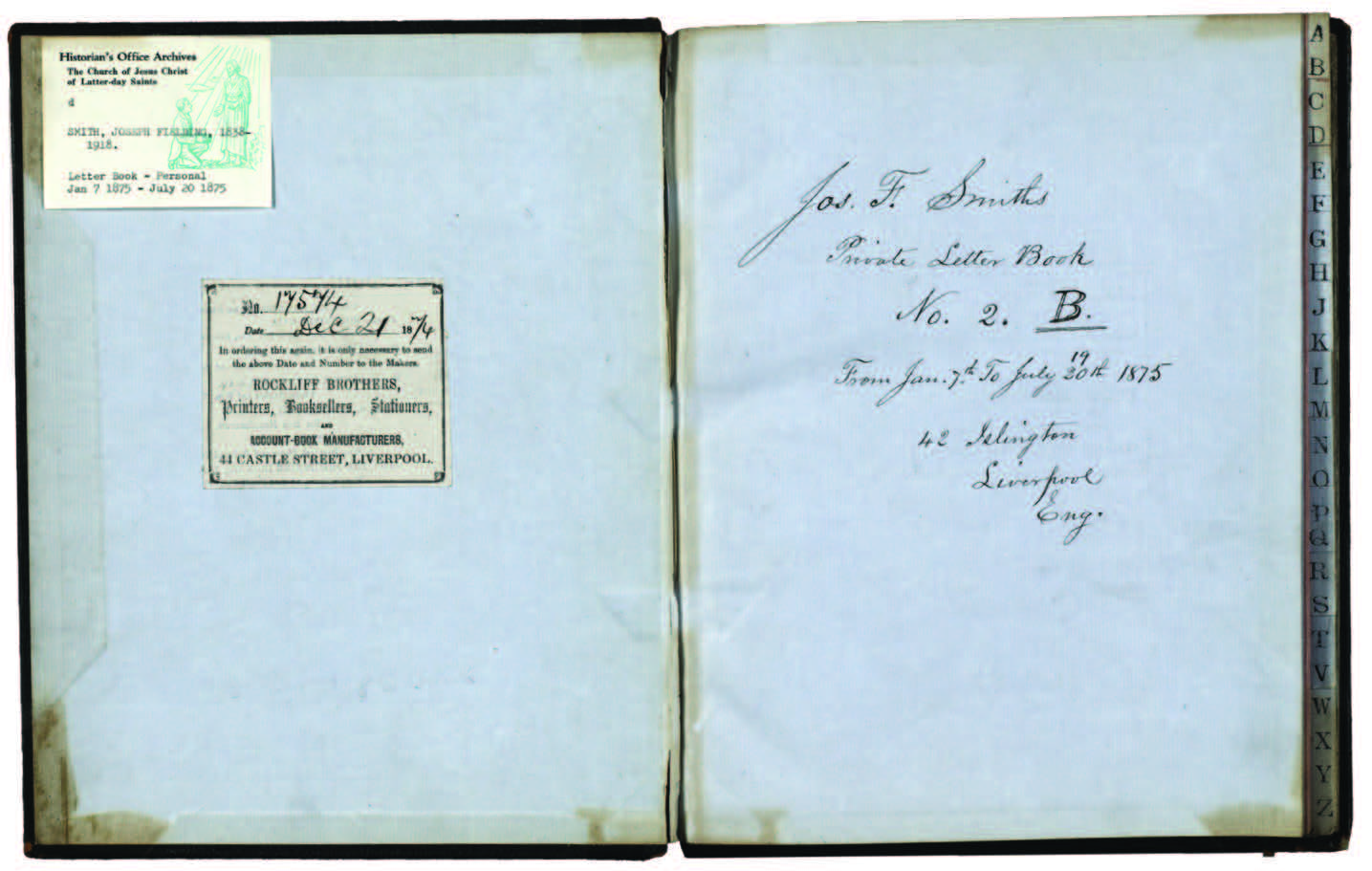

Apparently, Joseph F. purchased his first letterpress copybook in Liverpool, England, while he served as president of the European Mission.[31] A photocopy of this letterpress copybook is preserved in the Annie Clark Tanner Western Americana Collection, Special Collections Department, J. Willard Marriott Library, University of Utah, Salt Lake City. Joseph F. wrote on the page facing the inside cover, “Joseph F. Smiths Letter Book No. 1-A From July 17, 1874 to December 31, 1876.”[32]

Joseph F.’s nineteen letterpress copybooks that are preserved in the Church History Library cover various time frames from 7 January 1875 through 27 March 1917 with some major gaps.[33]

Inside cover of Joseph F.’s second letterpress copybook, covering the period of 7 January through 20 July 1875. Courtesy of CHL.

Inside cover of Joseph F.’s second letterpress copybook, covering the period of 7 January through 20 July 1875. Courtesy of CHL.

As noted earlier, the letterpress copybooks preserve copies of original letters now lost as well as copies of many extant original letters written after 1875.[34] When combined with the original letters of Martha Ann to Joseph F. that were preserved in the CHL, we have additional sources that provide important and interesting information. Many of the original letters are preserved with their accompanying envelopes. The additional information gleaned from the envelopes themselves, including postage marks and Joseph F.’s handwritten comments on the front or back, are invaluable. Additionally, some of Joseph F.’s original letters were often written on preprinted letterhead, providing even more information about the context of the letters. None of this kind of information is preserved in the letterpress copybooks.

We have included a representative sampling of the images of the letters and envelopes for each decade. Many more images of the original letters, envelopes, and copies from the letterpress copybooks exist. The decision to limit the number of images used herein is based on the desire to provide more historical context with introductory essays, photographs of the people and places mentioned in the letters, introductions for each decade, extensive annotation for each letter, and a biographical register.

Research Continued

Whitchurch took charge of the entire project and worked tirelessly to provide additional annotations, finish the historical summaries for each chapter, and complete a penultimate draft while Holzapfel was on academic leave from BYU between 2010 and 2013 to preside over the Alabama Birmingham Mission. On his return to BYU during the summer of 2013, Holzapfel reengaged in the project and continued research and writing. In 2014 Holzapfel and Whitchurch learned of two additional letterpress copybooks in private possession covering the periods March 1888 through August 1888, March 1895, and September 1896. Mark L. McConkie, a great-grandson of Joseph F. Smith, had obtained them from his father and mother, Bruce R. and Amelia Smith McConkie. Amelia was Joseph Fielding Smith’s daughter and Joseph F.’s granddaughter. Holzapfel flew to Colorado to examine them and found they contained additional letters addressed to Martha Ann.[35]

Letterpress copybooks, 16 March 1895–4 September 1896 (to the left) and 2 March 1888–29 August 1888 (to the right). Courtesy of Mark L. and Mary Ann McConkie.

Letterpress copybooks, 16 March 1895–4 September 1896 (to the left) and 2 March 1888–29 August 1888 (to the right). Courtesy of Mark L. and Mary Ann McConkie.

Under the date 29 August 1888, Joseph F. provided important information about some of his missing letters: “The following correspondence is continued from my coppy book opened in Washington D. C. Feb. 1888. This book was laid aside Aug. 29th 1884. Four years ago today when I left Salt lake City on a mission with Elders Erastus Snow and John Morgan to Colorado, Arizona and New Mexico, and S. Eastern Utah. from which date until now I have been in Exile on account of persecutions and prosecutions under the Edmunds and Edmunds-Tucker Laws. On Sept. 15th I copied one letter in this book. Most of my letters since 1884 have not been copied in any book.”[36]

The letters from Joseph F. to Martha Ann that were discovered in one of these letterpress copybooks added to the growing collection of letters and filled an important gap in the correspondence. McConkie allowed Holzapfel to take the letterpress copybooks to Salt Lake City to be digitized. Copies were donated to the Church History Library and the originals returned. Additionally, McConkie graciously gave permission to include the letters in this book.

Letter from Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 6 August 1895, copy found in Joseph F.’s letterpress copybook. Courtesy of Mark L. and Mary Ann McConkie.

Letter from Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 6 August 1895, copy found in Joseph F.’s letterpress copybook. Courtesy of Mark L. and Mary Ann McConkie.

The Finish Line

Holzapfel and Whitchurch continued preparing the manuscript for publication during the next two years, providing additional annotations to the letters, expanding the historical summaries, and adding additional images from the Smith and Harris families and institutional repositories. The search for additional letters and efforts to complete the research ended in 2018.

This book contains all the known surviving letters—241—between Joseph F. and his sister Martha Ann.

Joseph F. and Martha Ann Letters

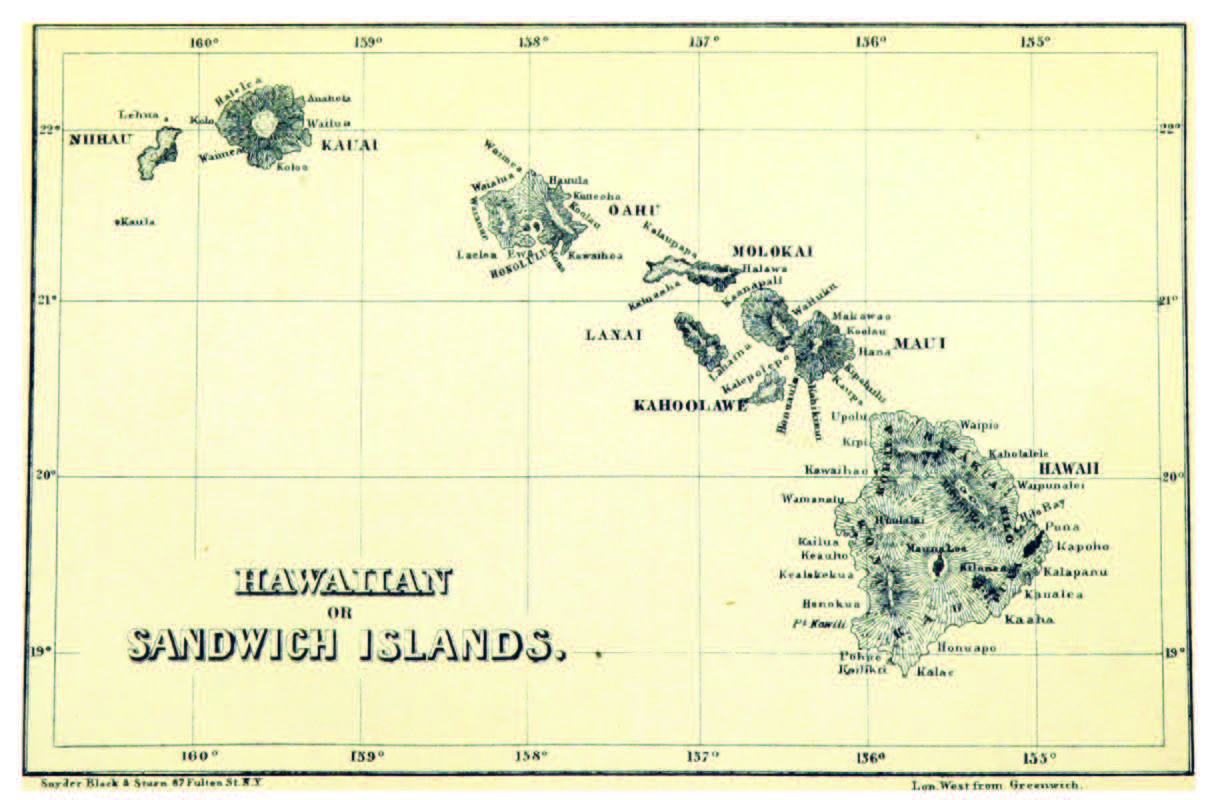

The first letter in the collection is dated 17 October 1854 and was handwritten on plain paper by Joseph F. when he was a fifteen-year-old inexperienced and undereducated young missionary living on the island of Maui in the Kingdom of Hawai‘i, identified as the Sandwich Islands in the letters.[37] Martha Ann’s first letter in the collection, dated 31 January 1856, was written when she was fourteen and living in Salt Lake City in Utah Territory.

Hawaiian or Sandwich Islands, in Edward T. Perkins, Na Motu: or, Reef-Rovings in the South Seas (New York: Pudney & Russell, 1854).

Hawaiian or Sandwich Islands, in Edward T. Perkins, Na Motu: or, Reef-Rovings in the South Seas (New York: Pudney & Russell, 1854).

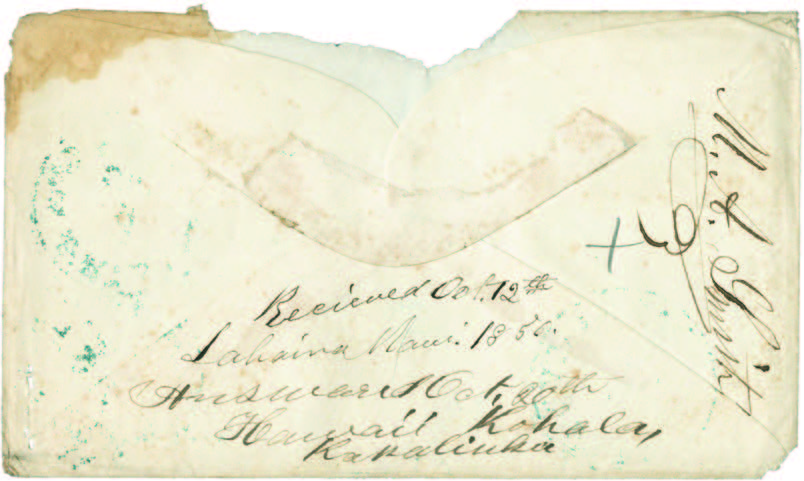

The last two letters in the collection are dated 13 December and 19 December 1916. The earlier letter was written by Martha Ann. The final letter in the collection was written by Joseph F. Martha Ann’s letter is handwritten on high-quality paper without lines. She was a much-beloved seventy-five-year-old mother, grandmother, and great-grandmother living in Provo, Utah, a city that had come of age since she moved there in the 1860s.

Joseph F. typed his letter on official Church stationery. He was a much-beloved seventy-eight-year-old President of the Church living in Salt Lake City, the largest city in Utah—the state capital and the world headquarters of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

Much had changed in the Church, Utah, America, and the world from the time when the first letter was handwritten in 1854 to when the last letter was typed in 1916. For example, the Kingdom of Hawai‘i no longer existed; it had been absorbed into the United States as a territory.[38] Additionally, Utah was a territory when Martha Ann received the first letter from Hawai‘i, but it had already been a state for more than twenty years when she and Joseph F. exchanged letters in December 1916.[39]

Of course, other changes had swept across the landscape in Utah, the nation, and the world during the more than sixty years that separated the first letter from the last letter. For example, when Martha Ann said goodbye to her brother in 1854, neither she nor Joseph F. could have imagined a day when women voted and ran for public office.[40] Joseph F. had supported women leaders such as Emmeline B. Wells in their effort to achieve woman’s suffrage in Utah in 1896.[41]

Group portraits of Joseph F.’s younger children, December 1896, photograph by C. R. Savage, Salt Lake City, Utah. Courtesy of CHL. The portrait of eight daughters was taken on 12 December 1896 and the portrait of eight sons on 19 December 1896.

Group portraits of Joseph F.’s younger children, December 1896, photograph by C. R. Savage, Salt Lake City, Utah. Courtesy of CHL. The portrait of eight daughters was taken on 12 December 1896 and the portrait of eight sons on 19 December 1896.

Another change was in their individual familial relationships. Martha Ann and Joseph F. were unmarried orphaned children in 1854, but by 1916 Martha was a widowed mother of a large multigenerational family and Joseph F. was the husband to four living wives with an even larger multigenerational family.[42]

In this view, Martha Ann is seated in the second row holding two great-grandchildren and surrounded by her family in front of the Provo Sixth Ward building. This photograph is one of four taken at the Martha Ann Smith and William Jasper Harris family reunion in 1917. The exact date is found written on the reverse side of two of the original glass-plate negatives by the photographer. See George Edward Anderson Collection, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah. A tradition of holding a reunion each year continued uninterrupted long after Martha Ann died in 1923.[43]

Martha Ann and Joseph F.’s correspondence collection does not contain all the letters they wrote to each other; they both mention letters they received that are not extant.[44] For example, in May 1880 Joseph F. noted, “It has been a long time since I wrote to you, and I have received several letters for which I am indebted to you.”[45] We did not find any letters written by Martha Ann in 1880, so we assume these letters have been lost to the ravages of time and nature. Also, a fire in Hawai‘i during Joseph F.’s first mission in 1856 destroyed his trunk and the contents inside, including the letters Martha had sent to him previously.[46] When Martha Ann found out about the fire, she asked Joseph F. if her letters had been destroyed: “ <did> you gitt your letters all burnt up or did you save enny of them. pleas tell me about it in the next letter you write to me.”[47] In his follow-up letter Joseph F. noted, “Well, now for your letter; you asked me if all my letters ware burnt, or if any were remaining. all those I recieved before the misfortune ware burned,[48] but no axident has yet happened to those I’ve recieved since.”[49]

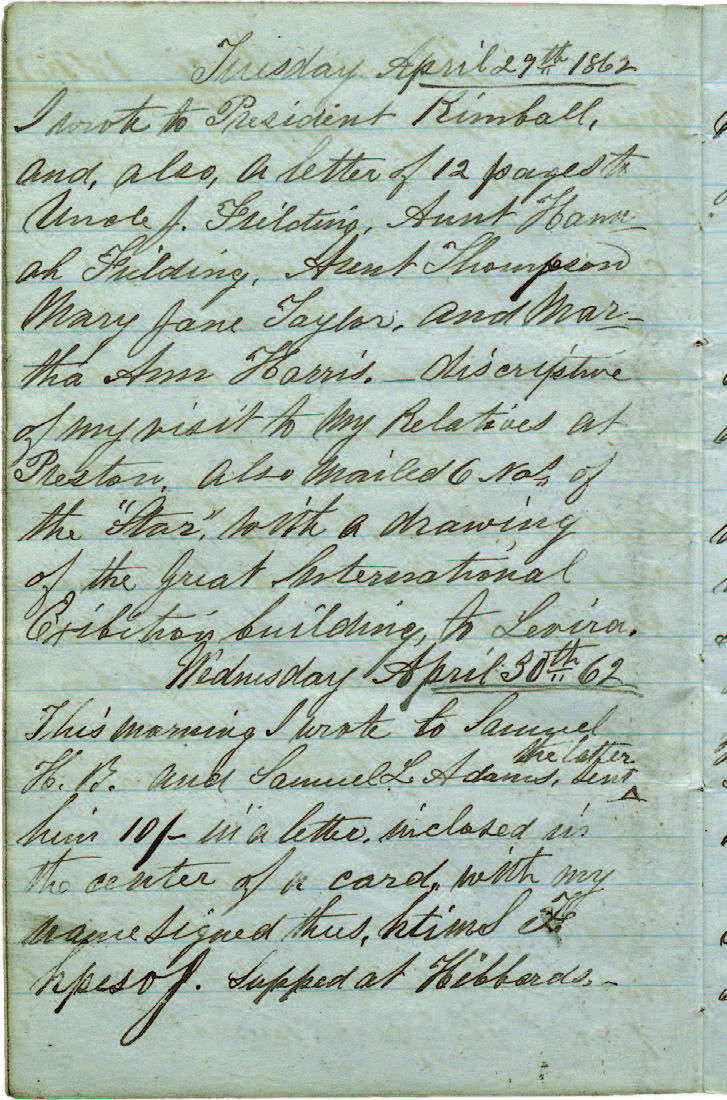

Some of Joseph F.’s letters written before he began the practice of keeping copies through a letterpress copybook have been lost. For example, he noted in his journal: “Tuesday April 29th 1862. I wrote to President Kimball, and also, a letter of 12 pages to Uncle J. Fielding, Aunt Hannah Fielding, Aunt Thompson, Mary Jane Taylor, and Martha Ann Harris.”[50] Since no letter to Martha Ann dated 29 April has been found, we assume it may have not survived.

Like other nineteenth- and early twentieth-century letters, Joseph F. and Martha Ann’s letters are records containing cultural, historical, linguistic, and social information. Not surprisingly, the letters are interwoven throughout with observations about family matters, including rather mundane concerns and incidents. Additionally, the letters are full of shared life experiences, including births, marriages, sicknesses, and deaths of immediate and extended family members and friends.

Maintaining good health without antibiotics and other advances in medicine during this period was a great concern. In a letter to his first cousin once removed, John L. Smith (1823–93), Joseph F. noted, “We have had the measles, colds, coughs, canker, and one thing and then another ever since last Dec. and are not thro’ with it yet. Tho’ we are getting somewhat accustomed to it. And are much better. I am fearful however that one of our little ones has the whopping cough and if so we have 6 more liable to take it. What the end may be no man knoweth!”[51]

William Jasper and Martha Ann Smith Harris family reunion, 11 April 1912, photograph by George Edward Anderson, Springville, Utah. This is one of four photographs taken on this occasion by the well-known photographer George Edward Anderson. In this view, the entire family was positioned outside the main entrance of the Provo Sixth Ward building with Martha Ann prominently placed in the center holding two grandchildren. Courtesy of Carole Call King.

William Jasper and Martha Ann Smith Harris family reunion, 11 April 1912, photograph by George Edward Anderson, Springville, Utah. This is one of four photographs taken on this occasion by the well-known photographer George Edward Anderson. In this view, the entire family was positioned outside the main entrance of the Provo Sixth Ward building with Martha Ann prominently placed in the center holding two grandchildren. Courtesy of Carole Call King.

As to be expected, there are also references to historically significant events—for example, the Utah War in 1857; the Church’s actions to counteract the move by Walter M. Gibson (1822–88) to create an independent Latter-day Saint rogue colony in Hawai‘i beginning in 1861; the visits of Alexander Smith (1838–1909) and David Smith (1844–1904), Joseph Smith and Emma Hale Smith’s sons and Joseph F. and Martha Ann’s cousins, to Salt Lake City in the 1860s when Alexander and David arrived as missionaries for the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints; the US government’s legal campaign to end plural marriage in the 1880s; and the political situation in Utah following statehood in 1896.

Joseph F.’s journal for 29 April 1862. Courtesy of CHL.

Joseph F.’s journal for 29 April 1862. Courtesy of CHL.

S. George Ellsworth, a much-respected western, Utah, and Latter-day Saint historian and university professor, emphasizes the value of letters.

Personal letters have a way of being quickly lost, misplaced, or purposely destroyed. Rare indeed are collections of significant family letters. Their preservation can be attributed to familial piety, a historic sense, sentimentality, accident, or just plain squirrel tendencies. Yet there is no more valuable record of personal reflections of events, institutions, and contemporary attitudes than the letter written from the heart and intended only for the eye of the receiver. The author of a journal, by the very act of maintaining entries, implies interest in the preservation of his life events for himself or posterity. Not so with letters. Hurriedly written, full of apologies for spelling or penmanship with promises to do better next time, the personal letter provides the only record of intimate conversation though taking place at a distance. Through letters one is permitted to glimpse into the heart of another’s life and age.[52]

This is true of this remarkable family letter collection preserved by Martha Ann and her descendants and fellow Church members, to whom Martha Ann and Joseph F. were dedicated all their lives.

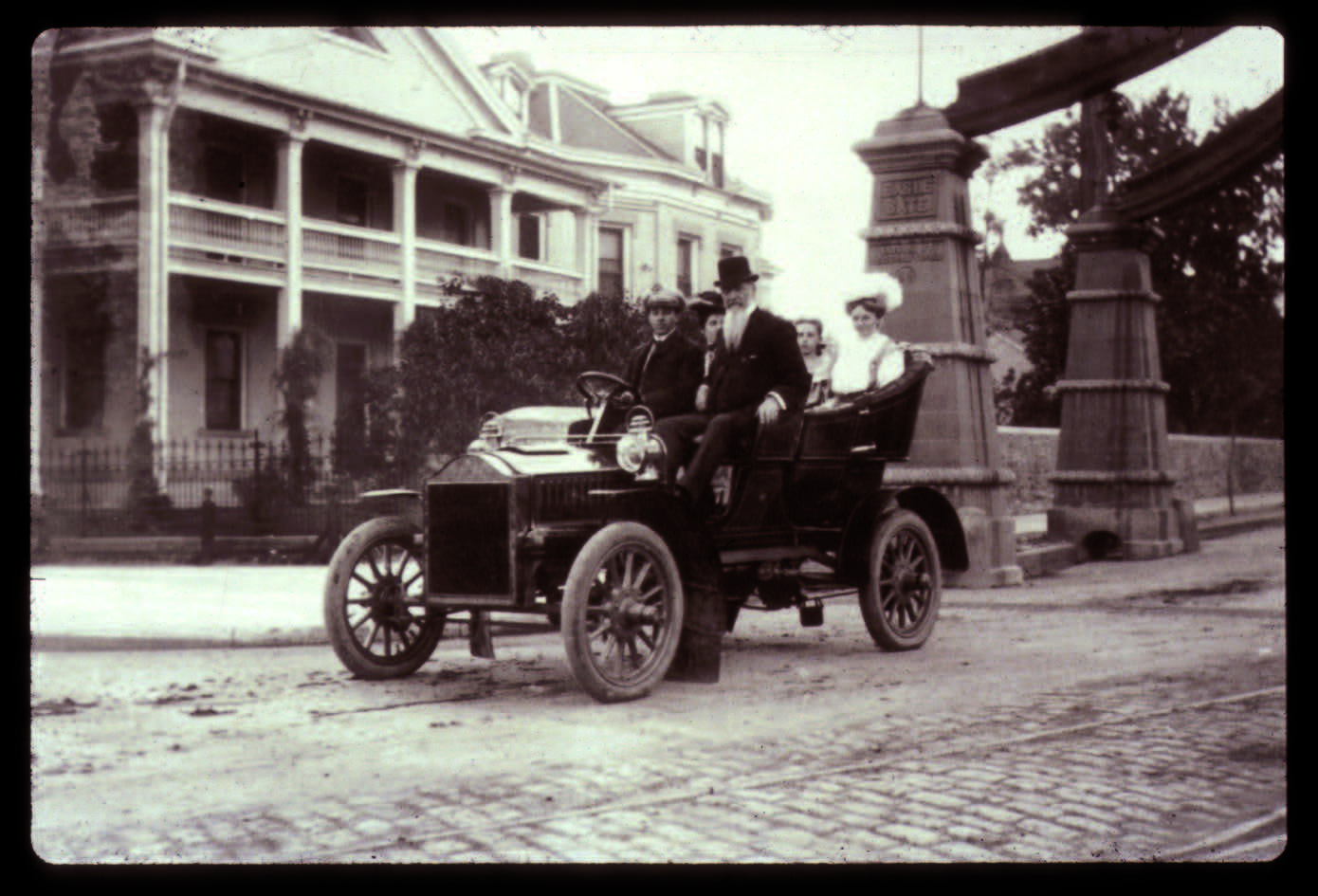

The letters of the last two decades, from about 1900 through 1916, become noticeably more sporadic, with much shorter content. Additionally, there are no extant letters from the last two years of Joseph F.’s life (1917–18). This is likely due to a combination of factors, including advances in communication. For example, in a letter written in June 1899, Joseph F. asked Martha Ann to respond by telegraph: “Want to do Temple-work next week for the Fieldings. Expect Rachel Burton down next Monday. Can you come? Let me know by Deseret wire.[53] All well here.”[54] In another letter to Martha Ann written in 1911, Joseph F. noted that he sometimes used the telephone to relay information: “We will keep you posted by letter or phone as to his condition.”[55]

Joseph F. Smith and party, ca. 1902–3. Courtesy of Anne Alice Smith Nebeker.

Joseph F. Smith and party, ca. 1902–3. Courtesy of Anne Alice Smith Nebeker.

Additionally, improved travel between Salt Lake City, where Joseph F. lived, and Provo, where Martha Ann lived, a relatively short distance of forty-five miles, made visits much easier during the last several decades of their lives. Also, Joseph F., as President of the Church, was no longer assigned to foreign missions that separated him from family in Utah for long periods of time, making it less critical to write letters to them.

He often saw Martha Ann or members of her family during his frequent visits to Provo and visits by family to Salt Lake City. These visits would naturally allow Joseph F. to obtain information about Martha Ann’s health and family concerns. Martha Ann, later in life, also traveled to Salt Lake City to attend general conference twice each year and generally stayed with Joseph F.

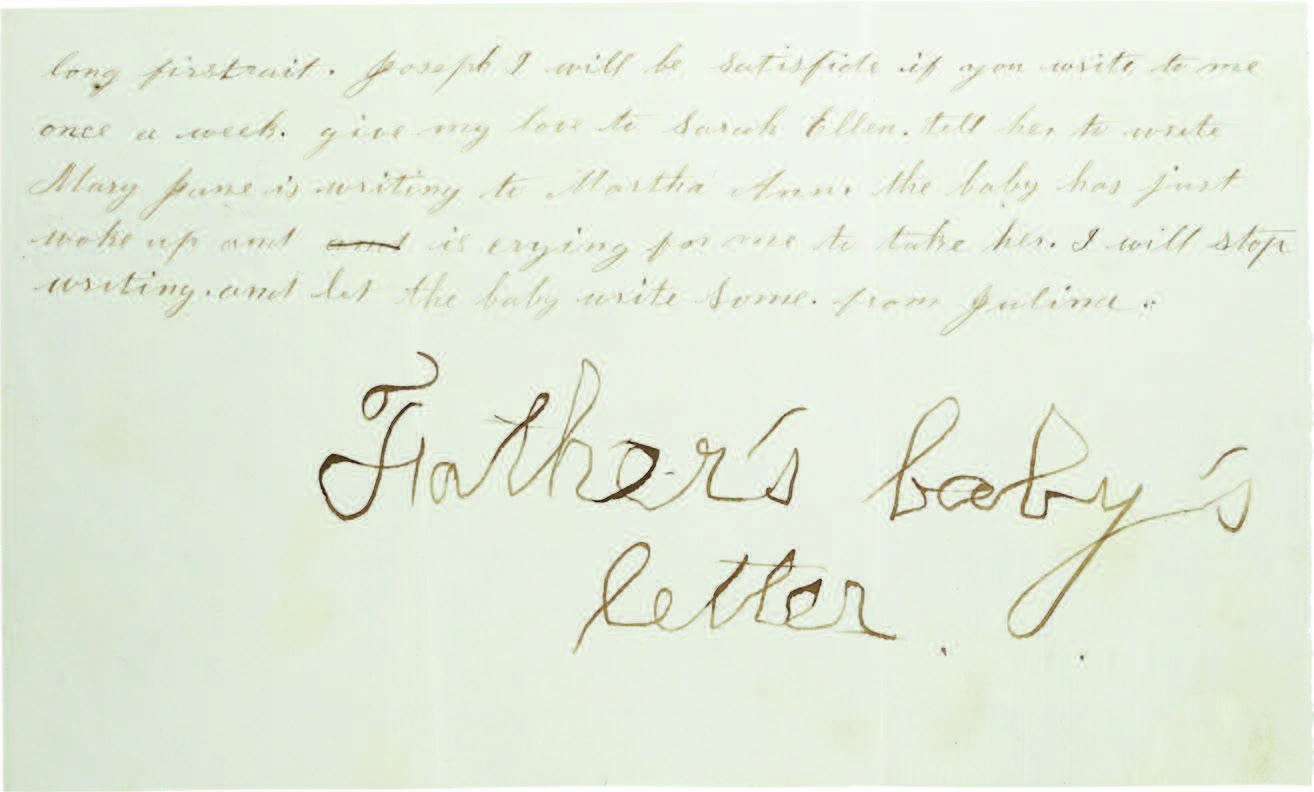

Letter from Julina Smith to Joseph F., 23 April 1868 (reverse side). Courtesy of CHL. Julina mentions that their young daughter, “Mary Jane, is writing to Martha Ann.” Apparently Mary Jane finishes the letter to Joseph F.

Letter from Julina Smith to Joseph F., 23 April 1868 (reverse side). Courtesy of CHL. Julina mentions that their young daughter, “Mary Jane, is writing to Martha Ann.” Apparently Mary Jane finishes the letter to Joseph F.

They both used their connections with other family members to keep in contact and expected that letters written to other family members would be shared among them. For example, Joseph F. noted in a letter to Martha Ann, dated 25 July 1857, “I wrote a long letter to Aunt Thompson yesterday-evening—gave her a short history of my travels for the last three or four months, it may b be interresting to you, if you have an oppertunity of hearing it.”[56] In 1881 he asked his nephew William J. Harris Jr. to provide information to Martha Ann: “I did not write to your mother when our last baby was born, but you could tell her, what the baby was like as you saw it.”[57] On another occasion, Julina Smith mentioned, “I am going to write a little to Martha Ann and send her the babies photograph.”[58]

In a letter written to one of his sons, George Carlos Smith (1881–1931), Joseph F. asked him to contact Martha Ann’s husband, William Jasper Harris (1836–1909), to request the use of his horse and buggy: “I intend to visit Provo tomorrow morning by Oregon Short Line. Meet us at the Station with Uncle William’s buggy.”[59]

During the fall of 1898, one of his daughters was attending Brigham Young Academy. In his letters to her, he often made reference to his sister. In one letter Joseph F. thanked her for taking time to visit his sister and her family: “I am glad you go down to see Aunt Martha occasionally, and we all want to be remembered to her and to all the children.”[60] Nearly three months later, he asked her to pass along his greetings to the family from whom she received room and board in Provo and to his sister: “With kind love to Bro. and Sister Boyden, to Aunt Martha and her family.”[61]

In the later years of life Joseph F. and his sister had large families that naturally took more of their time, so it is not surprising that fewer letters between them were being written. Joseph F. observed in September 1895 the shifting nature of their letter writing: “Your favor of the 22nd inst. Came to hand on the 23rd inst. I did not expect an answer to my letter, therefore to hear from you was an unexpected surprise. In former years we corresponded once in a while, but of late this practice seems to have gone into disuse.”[62]

Envelope for letter from Martha Ann to Joseph F., 29 July 1856, with a postmark of 5 August 1856. Courtesy of CHL.

Envelope for letter from Martha Ann to Joseph F., 29 July 1856, with a postmark of 5 August 1856. Courtesy of CHL.

The Joseph F. and Martha Ann letter collection provides insights into the relationship between two siblings who began corresponding when they were young people and who each developed along different paths in life as they were prematurely thrust into the responsibilities of adulthood. It highlights Joseph F.’s experience as a young missionary, maturing Church leader, and father of a large family living in multiple households.[63] The collection also provides insight into Martha Ann’s experiences growing up in Salt Lake City and aging in Provo, where daily toil and survival were often of foremost concern. We also learn about Martha Ann’s work in her family and community, where she fulfilled many roles, including provider, caregiver, supporter, and friend. Martha Ann, unlike her brother, lived in a monogamous household. Nevertheless, she was part of a complex family web of relationships as a member of the Hyrum Smith (1800–1844) family.

Additionally, the letter collection demonstrates very clearly Joseph F.’s role as an older brother who was willing to provide personal counsel and direction to his younger sister, and later to her children, on a variety of matters. Surprisingly, even when he was still a teenager, the letters reveal that Joseph F. had also assumed the role of Martha Ann’s parents, both father and mother. This may be partly due to the siblings’ unique position as the only children of Hyrum and Mary Fielding.[64] This certainly influenced their relationship in positive ways—Joseph F. felt deeply responsible and genuinely concerned about Martha’s temporal and spiritual welfare and her personal happiness.

Martha Ann regularly acknowledged her gratitude for Joseph F.’s attention to the details of her life. For example, in 1874 Martha Ann wrote, “to my truest most faithfull friend that I have had sence the death of my dear Mother you have never forsaken me you have been more than a brother to me you have filled as near as could bee the plase of a Father I do feel greatfull to you for all you have done and may the God we try to sirve reward you for I never can more than bee greatfull.”[65]

As in most family relationships, Martha Ann and Joseph F. did not always understand each other. Complex family relationships naturally complicated their own relationship from time to time. Joseph F. mentioned one such situation in 1898: “I was very sorry you left us so abruptly on the morning you went away. It was so unnecessary—but of course we are all free agents, and will only be held for our voluntery acts. I did not follow you to the Depot—for the reason you made <it> unwise if not impossible for me to do so. You had a full half hour, I should think, to wait at the station before the train started. We were all sorry to have you leave us feeling as you did. I hope your feelings may change when you know us better.”[66]

However, their lifelong commitment and loyalty to one another allowed them to soothe any tension they may have had at specific times. Throughout the letters, Joseph F. is acutely aware that his life had often provided him opportunities that his sister did not enjoy. In 1869 he wrote, “I feel condemned sometimes when I see the comfortable situation of my family and know that my own sister does not enjoy as much.”[67] In 1877 he also noted, “I wish you were as strong and healthy as I am, and as well or better clad.”[68] As they grew older, his feelings became even more tender as he considered Martha Ann’s deteriorating health and seemingly never-ending financial challenges.

Despite Joseph F.’s own pressing financial concerns as his own family grew in size, he was nevertheless mindful of Martha Ann’s situation.[69] Highlighting Joseph F.’s efforts to assist Martha Ann, the letters mention gifts he sent from time to time, including for weddings and births, and especially during the holidays.[70] Additionally, through the letters we discover that at some point Joseph F. provided Martha Ann a monthly allowance, which increased over time to help her make ends meet.[71] In the end Joseph F., despite his distinct advantages in life, admired his sister for her tenacity and endurance. For example, he noted in his diary a letter he had received praising Martha Ann from his Aunt Zina Huntington in 1862, “Martha Ann was up last evening to see us. Looks stately and fine as ever, one of God’s noble women. If you could see those noble boys of her, it would do your soul very good. Men in miniature.”[72]

For Martha Ann, these letters provide insight into the day-to-day struggles of survival on the pioneer frontier. She is very much self-aware. For example, she wrote Joseph F. in 1863, “I am not a very good writer which you are well aware off but what I write ill composed as it is comes from my heart and I mean it I may not not have the languege of some nor the talent for writing that this will ed<i>fye a preson say ferinstence <that> Levira[73] has but my life has been far differenty spent to what hrs has been I have had to earn my bred by hard labor ever sence my m<o>thr died[74] I have ben obliged to work hard and it does not have a tendencey to refine any ones mind to such things.”[75]

Her letters also provide a woman’s view of life’s rhythms—marriage, childbearing, sickness, family financial concerns, and death.[76] She does not provide counsel or direction to her older brother; she clearly sees her role as one who receives counsel, direction, and help. The nineteenth- and early twentieth-century context reveals much about the multifaceted relationship Joseph F. and Martha Ann experienced over a long period.

Pen and paper served to strengthen the bond between Joseph F. and Martha Ann throughout their lives. That they preserved some of their letters is not surprising since for many people of that era letters often became a representative keepsake of a loved one who was far away. A special letter was often carried with a person or tucked under a pillow as a means of embracing a cherished personal connection.

Because Martha Ann remained in Utah, many of Joseph F.’s letters were preserved. Since he was on the road, traveling from continent to continent during the 1850s, 1860s, and 1870s, some of her letters to him did not survive. This was also true for the difficult years of the second half of the 1880s when Joseph F. was on the move and in hiding to avoid prosecution for plural marriage.

As noted above, the letter collections range in date over nearly six decades, from 1854, when Joseph F. first arrived in the Sandwich Islands, to 1916, just two years before his death. The nearly lifelong personal correspondence between Joseph F. and Martha Ann demonstrates a brother and sister who cared deeply for each other—a brother who was concerned for the well-being of his younger sister and a sister who adored her older brother.

Another important aspect of the collection is that many of the original envelopes from Joseph F.’s letters were preserved by Martha Ann and subsequently by her family. At first, letters were folded and sealed with wax so they could be sent without a cover (envelope). Eventually, innovation produced machines that made envelopes relatively inexpensive. Advances in making postal stamps, coupled with postal reforms in the United States, allowed an increasing number of Americans to communicate with family, friends, and others. Joseph F. and Martha Ann took advantage of these advances, as demonstrated by the letters, envelopes, and postal services they used to communicate with each other.

This publication includes all known letters written between Joseph F. and Martha Ann from 1854 to 1916. During that time, there are just nine years of correspondence for which no known record of their communication exists (1859, 1865–67, 1882, 1889, 1903–4, and 1908). The historical overview and introduction to the letters for each decade, along with the footnotes included with each letter, provide illuminating context. The following chart summarizes the locations from which the letters were sent and the approximate years in which they were written.

Letters from Joseph F. Smith to Martha Ann Smith Harris

| Place of origin | Number of letters |

| Sandwich Islands [Hawaiian Islands] (1854–58) | 13 |

| Salt Lake City, Utah, USA (1858) | 1 |

| British Isles [Great Britain] (1860–63) | 8 |

| Sandwich Islands [Hawaiian Islands] (1864) | 2 |

| Salt Lake City, Utah, USA (1868–74) | 33 |

| British Isles [Great Britain] (1874–75) | 10 |

| Salt Lake City, Utah, USA (1875–76) | 3 |

| British Isles [Great Britain] (1877) | 1 |

Salt Lake City, Utah, USA (1877–84) No address provided (1877–84) | 16 7 |

| Sacramento, California, USA (1885) | 1 |

| Sandwich Islands [Hawaiian Islands] (1885) | 4 |

| No address provided (1887) | 1 |

| Salt Lake City, Utah, USA (1890–1916) | 40 |

| No address provided (1890–1916) | 53 |

| Total | 193[77] |

Letters from Martha Ann Smith Harris to Joseph F. Smith

| Place of origin | Number of letters |

Salt Lake City, Utah, USA (1854–67) No address provided (1854–67) | 23 3 |

Provo, Utah, USA (1868–1916) No address provided (1868–1916) Total | 20 2 48 |

| Total Letters between Joseph F. and Martha Ann | 241 |

Writing Skills and Improvement

It is clear that both Joseph F. and Martha Ann lacked the benefits of long-term formal educational opportunities, as the letters are full of spelling, grammar, syntax, and mechanical errors. Joseph F. estimated the extent of his formal education to have been just a little over three years.[78]

For example, in an early letter to Martha Ann, Joseph F. counseled her to improve her writing even as he was trying to improve himself: “I hope that the school will soon start again that you can keepe going as much as posible. I want to see you improve in writing, and every thing els, when you write take pains and make the letters all plain and destinct, and be shure to spell all of the words right that you can; . . . now I will worant that if you will go to school with a prayerful heart, and your mind on your studies, insted of being upon play and folly, that you will learn faster than ever you did in your life before. the thing of it is be prayerful, pray morning and night.”[79]

Later in life, when he became more proficient, Joseph F. still noted that he was not a good speller but offered advice about writing so that his children would be better than he was: “I do not attempt to counsel your spelling because I am a good speller myself, but only because I would like you to spell and write better than I.”[80]

A brief review of the original 1850s letters demonstrates that Joseph F. and Martha Ann began with about the same command of English and writing skills. Their spelling, grammar, usage, mechanics, and calligraphy clearly reveal a lack of formal and informal education. Given their life experiences from their births to 1854, this is not surprising. They lived in several frontier communities that were brand-new or recently established; they both worked to assist the family with chores and responsibilities that were sometimes only expected of older children and adults; they were unable to follow a daily schedule, which included attending school, on a regular basis; they did not live in a house for significant periods of time; and finally, they experienced many tragic events, including the murder of their father and the early death of their mother.

Scholars have observed that immigration and migration impacted nineteenth-century frontier culture.[81] Generally accepted social niceties and cultural refinements were either forgotten entirely or so weakened that children struggled to completely assimilate them. It was the nineteenth century after all, and pioneering only added to the challenge of creating a refined society with all of the opportunities that a more stable community could afford children.

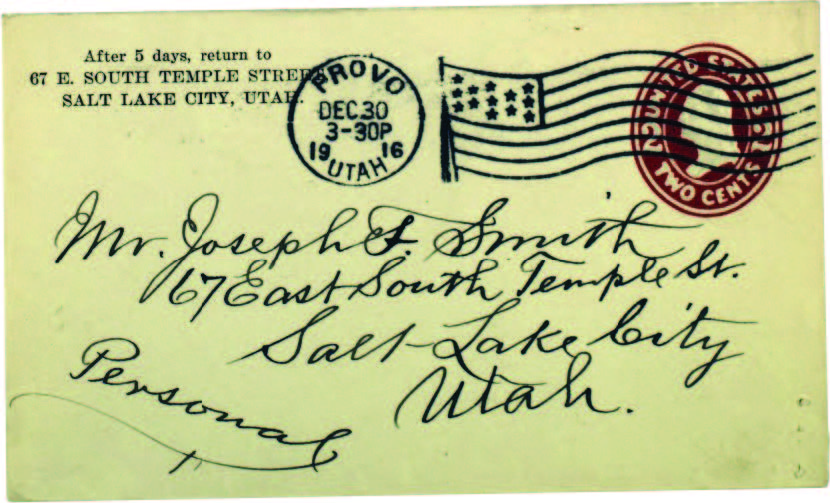

Joseph F. improved dramatically in his language ability and calligraphy. His mission diaries from the 1850s reveal important themes that are also highlighted in his letters to Martha Ann. Joseph F. became a voracious reader of books, newspapers, and other items that came into his hands. He also practiced his writing by keeping a daily journal and maintaining a remarkable correspondence with numerous people, and he used a dictionary and other sources to increase his vocabulary.[82] Lists of new words are found on envelopes and in notebooks and journals. His letters and journals show that he used these new words often and that they became familiar to him. By 1916, when the last letters in this collection were prepared, Joseph F. had become a skilled orator and writer with a rich vocabulary. He was able to draw from a wide variety of published materials, including poems, hymns, biographies, and other reading material. In the end, Joseph F. was indefatigable in his effort to improve and learn. Taysom notes, “I am dazzled by his intellect and his unbreakable will.”[83] Reading this collection of letters will most likely confirm Taysom’s assessment.

Martha Ann, on the other hand, remained at about the same skill level and may have lost some of her calligraphy skills, as one might expect, in the last decades of her life. Limited in life opportunities of traveling and exposure to a wide variety of print culture, she instead spent most of her time raising a family, including grandchildren and great-grandchildren. Martha Ann’s daily work was often of a different kind than that of her brother. Working with her hands to sew in limited lighting made it more challenging to pick up a book, keep a journal, or write many letters. That she wrote letters to a variety of people is not surprising given she was a member of an important Latter-day Saint family. However, buying a new pen or paper was sometimes impossible—choosing them over bread was not a hard decision.[84] To help defray these extra expenses in later life, Joseph F. sent her self-addressed stamped envelopes. He added a handwritten postscript in a typed letter to Martha Ann in 1896: “Please find herewith a stamped Envelope.”[85] Given her struggles and limited opportunities, we are fortunate that she chose to write even when she was reluctant to do so.

A prestamped, self-addressed envelope in Joseph F.’s hand. Postmarked 20 December 1916, it was sent to Martha Ann so she could write Joseph F. without incurring expense. Courtesy of CHL.

A prestamped, self-addressed envelope in Joseph F.’s hand. Postmarked 20 December 1916, it was sent to Martha Ann so she could write Joseph F. without incurring expense. Courtesy of CHL.

The collection also reveals much about a period of great transition in Latter-day Saint history. Joseph F. and Martha Ann not only witnessed but also participated in the events that brought the exiled Latter-day Saints to the Great Basin seeking refuge from persecution. Their lives also spanned the early decades of the twentieth century, when the Church was becoming a somewhat respected American religious institution.

Most telling throughout their six decades of correspondence are Joseph F.’s reflections and personal counsel to his sister about his mission and Church experiences, his perspectives on education and local and national political events, his thoughts on proclaiming the gospel of Jesus Christ, his profound grief after the death of a child, his devotion to his family and the Church, and the gratitude and love he and his sister shared for each other. Additional insights can be gained from a careful analysis of these letters. Certainly, future studies on a variety of topics will benefit from this remarkably rich collection of personal letters.[86]

Joseph F.’s Letters

The letters between Joseph F. and Martha Ann are part of a much larger collection of correspondences written and received by him. Many of these letters are preserved in public and private repositories, primarily the Church History Library. A brief review of these various collections reveals that Joseph F. was a prolific letter writer, as noted above. For example, between 1895 and 1914, Joseph F. wrote hundreds of letters to twelve missionary sons. Some 334 copies of these letters alone are preserved in the Church History Library, with additional original letters in the private possession of descendants.[87]

A comparison between the letters written to his missionary sons and those sent to his sister reveals Joseph F.’s effort to encourage improvement and offer suggestions and corrections regarding grammar and spelling. As their father, he was going to provide encouragement to each of them to improve their communication skills.

Another interesting facet of Joseph F.’s correspondence collection is a number of letters partly or fully written in Hawaiian. These are written to or received from Church members in Hawai‘i, a missionary son, and those living in the Hawaiian settlement of Iosepa in Skull Valley, Tooele County, Utah.[88]

Interestingly, a selection of his letters was published in Joseph F.’s lifetime.[89] This was a common practice in the Church during the nineteenth century, in which letters from the mission, emigrating companies (both land and ocean), and Church leaders were published.[90]

Of special note, Joseph F. dictated two letters on 24 May 1918 into a recording machine, preserving his voice for future generations to hear. One letter was addressed to President Joseph Eckersley (1866–1960), a stake president living in Loa, Wayne County, Utah.[91] The other was addressed to his son Calvin Schwartz (1890–1966), who was an army chaplain stationed at Camp Lewis, a US military installation located about nine miles south-southwest of Tacoma, Pierce County, Washington. Extracts from both letters were published in 1972 after the recording was discovered in Salt Lake City.[92]

The letter to Calvin shows how Joseph F. handled the numerous letters that flooded to him: “I have received this morning your most welcome favor and have read its contents with a great deal of interest. Your mother was here this morning while the letter was being read to me and was extremely pleased to hear from you.”[93] Although this letter had been read to him (implying secretarial assistance), for much of Joseph F.’s life most of his letter writing had been done without a secretary or stenographer. For example, Joseph F. responded to a son’s request to obtain more help in 1905: “In your letter of July 21st answering mine of June 30, you give me a good lecture on taking care of myself and of having a stenographer to assist me in writing my letters, &c. All of which I accept in the loveliest kindness. But my son, I never yet put upon another any burden I was not willing to carry myself.”[94] This insight makes his large body of correspondence all the more remarkable.

Joseph F. Smith at a writing desk, ca. 1916. Courtesy of CHL.

Joseph F. Smith at a writing desk, ca. 1916. Courtesy of CHL.

To keep up with a large amount of correspondence, Joseph F. asked the Salt Lake City postmaster, Arthur L. Thomas (1851–1924), to “arrange for three deliveries of mail daily to the Church office at about 9 and 11:30 a.m., and 4 p.m. and for collecting daily, the last, about 6:30 p.m.”[95]

In several letters, Joseph F. talks about the challenges he faced in keeping up with his correspondences. Later in life, as a counselor to Church Presidents, Joseph F. naturally placed their requests above other considerations. For example, he wrote to son David Asael Smith (1879–1952) a letter but was required to end it early: “Bro. [Lorenzo] Snow has called for me, so I will have to conclude this letter.”[96]

In many letters, Joseph F. mentions his habit in later life to write to family members late in the evening: “I have been very busy today. . . but have not had time. It’s now after 8 p.m. and I have not had my dinner.”[97] Having received a letter on 13 December 1898 from his daughter Edna Melissa Smith (1879–1958), who was attending Brigham Young Academy in Provo, Utah, he responded on 16 December. “I have been so busy I could not get a moment during office hours to write you. It is now just 8 p.m. All are gone from the office long ago except the guard and myself.”[98]

In a letter dated 12 July 1899, Joseph F. wrote Louise Emily Shurtliff Smith (1876–1908), his daughter-in-law, a short letter that provides insight into his efforts to communicate with family members. At the time, his son Joseph Fielding Smith (1876–1972) was serving a full-time mission in the British Isles. Joseph F. wrote, “I have concluded to put an end, at least temporarily, to the admonition of my consciences and the prompting of my desire to writ you a few words. I have been O so busy—all the time and have so many ‘irons in the fire’, that I have neglected to write, and have keenly felt condemned for it. We are all usually well. I am alone in the office, and it is 8 pm.”[99]

In 1908, he noted in a letter to his son E. Wesley Smith (1886–1970), who was serving a mission in Hawai‘i at the time, “I am devoting a portion of this sabbath day to the task of answering letters. My time is so much occupied during working hours from day to day that I have but little time, and that generally after I should be a rest in bed for correspondence, I am availing myself today of the services of your brother Joseph F. to assist me in replying to communications from mission fields and elsewhere to which I feel bound to reply.”[100]

As we began this project, we examined a number of entries in Joseph F.’s diaries along with the corresponding letters written at the same time. In some instances, Joseph F.’s letters provide more details than his diaries; this is especially true of the latter period of his life. In one specific case, the letters are the only record written by his own hand of his activities that have been preserved.[101]

Of course, in many other cases, Joseph F.’s journals record daily experiences over multiple days, weeks, and months and therefore present a much more comprehensive word picture of his daily life and concerns. The letters between him and another person cannot provide such a picture because large gaps of time exist between each letter. However, because Joseph F. kept a remarkable correspondence schedule, a study of his incoming and outgoing letters provides a remarkable and fuller view of his world, concerns, and insights. In many of his letters, he goes well beyond most of his journal entries on specific subjects.

Martha Ann’s Letters

Although not as voluminous as Joseph F.’s letter collection,[102] Martha Ann’s collection is remarkable because it spans the time from when she was a teenager in the 1850s to when she approached the end of her life in the early 1920s.[103] The hundreds of extant letters provide a window into her life and experiences as a member of a complex, multigenerational family network throughout her life.

An examination of the letters she received and retained reveals Martha Ann’s participation in extended conversations with family, friends, and associates.[104] For example, in early 1923 E. Wesley Smith (1886–1970), who was serving as president of the Hawaiian Mission, wrote:

Our Beloved Aunt Martha: How happy and extremely delighted we were to received your excellent letter, so full of good cheer and encouragement. We highly appreciate this letter, coming from you, in your own handwriting, an own sister to our beloved father. . . . Your big generous heart is manifest in this letter. Oh, what a wonderful spirit you have; always thinking about other people, sympathizing with them; praying for them and wishing blessings upon their heads, always desiring to be helpful and striving to aid. All these expressions of love from you have more than repaid us for any little thing we may have done in your behalf in the past.[105]

Unfortunately, most of the letters Martha Ann wrote were not retained or did not survive. As already mentioned, we know of at least eighty letters she wrote to Joseph F. that are not extant.

Toward the end of her life, Martha Ann wrote what would become her last surviving letter. At the time, Martha Ann’s grandson John Clifford Harris (1900–49) was serving in the Southern States Mission. In a ten-page letter addressed to John’s friend Francis Joanna Sherrell Spears (1880–1956) of Cookeville, Tennessee, she shared her testimony of the restored gospel, her reminiscences of the Prophet Joseph Smith and her father, Patriarch Hyrum Smith, and thanked Joanna for showing kindness to her grandson.[106]

Given the realities of nineteenth-century pioneer life, Martha Ann’s reluctance to write (owing to her poor penmanship and spelling),[107] the loss of her earliest letters to fire, and the vagaries of preserving family letters through succeeding generations, it is remarkable that we have as many of her letters as we do—more than seventy in all and as many as three hundred letters she received from friends and family members, including her brother Joseph F.[108]

Notes

[1] Joseph Fielding Smith, The Life of Joseph F. Smith: Sixth President of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1938).

[2] In contexts herein treating Joseph F. Smith’s younger years, he is referred to as “Joseph F.,” the name used affectionately by his sister Martha Ann and others who were close to him. In contexts dealing with his official capacity as President of the Church, he is referred to as “President Smith” or by his full name.

[3] Richard E. Turley Jr., ed., Selected Collections from the Archives of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 2 vols. (Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Press, 2003)

[4] Hyrum M. Smith III and Scott G. Kenney, comp., From Prophet to Son: Advice of Joseph F. Smith to His Missionary Sons (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1981).

[5] Scott G. Kenney, “Before the Beard: Trials of the Young Joseph F. Smith,” Sunstone 120 (November 2001): 20–42.

[6] Nathaniel R. Ricks, ed., “My Candid Opinion”: The Sandwich Islands Diaries of Joseph F. Smith, 1856–1857 (Salt Lake City, UT: Signature Books, 2011).

[7] David M. Whitchurch and Mallory Hales Perry, “Friends and Enemies in Washington: Joseph F. Smith’s Letter to Susa Young Gates, March 21, 1889,” Mormon Historical Studies 13, nos. 1–2 (Spring/

[8] See Craig K. Manscill et al., eds., Joseph F. Smith: Reflections on the Man and His Times (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2013).

[9] Matt Bowman, “Scholarly Inquiry: A Conversation with Stephen C. Taysom,” Juvenile Instructor, 25 May 2016, https://

[10] Bowman, “Scholarly Inquiry.”

[11] See 1 Corinthians 13:12.

[12] See Joseph F. Smith papers, 1854–1918, MS 1325. Some of Joseph F.’s journals, letters, and other items in this collection are currently closed to research. All primary sources cited in this book are found in the CHL unless otherwise noted.

[13] See Ricks, “My Candid Opinion.”

[14] See, for example, Martha Ann to Joseph F., 3 May 1857, herein.

[15] L. H. Butterfield, et. al, Adams Family Correspondences (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1963–2007).

[16] Dean C. Jessee, ed., My Dear Son: Letters of Brigham Young to His Sons (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1971).

[17] S. George Ellsworth, Dear Ellen: Two Mormon Women and Their Letters (Salt Lake City, UT: Tanner Trust Fund, University of Utah Library, 1974).

[18] See Smith and Kenney, From Prophet to Son. One of these letters, Joseph F. to Joseph Fielding Smith, 20 June 1899, was reprinted in Larry E. Morris, A Treasury of Latter-day Saint Letters (Salt Lake City, UT: Eagle Gate, 2001), 40–42.

[19] See Lu Ann Faylor Snyder and Phillip A. Snyder, eds., Post-Manifesto Polygamy: The 1899–1904 Correspondence of Helen, Owen, and Avery Woodruff (Logan, UT: Utah State University Press, 2009); and Reid L. Neilson, ed., In the Whirlpool: The Pre-Manifesto Letters of President Wilford Woodruff to the William Atkin Family, 1885–1890 (Norman, OK: Arthur H. Clark Company, 2011).

[20] An earlier report of the discovery of the letters was published in 2004. See David M. Whitchurch, “‘My Dear Sister’: Letters between Joseph F. Smith and His Sister, Martha Ann Smith Harris (1854–1916),” Mormon Historical Studies 5, no. 1 (Spring 2004): 195–202.

[21] Carole Call King noted, “I received all the family history material when my parents died. I really don’t think my darling mother knew about the treasured letters her mother left her. There were so many boxes of papers, photographs, letters, etc., she probably never went through all the things she had. My grandmother, Sarah Lovina Harris Passey, youngest child of Martha Ann Smith Harris, saved the letters received from her mother.” Carole Call King to Richard Neitzel Holzapfel, 14 October 2014, in editors’ possession.

[22] See Charles W. Nibley, “Reminiscences of President Joseph F. Smith,” Improvement Era, January 1919, 191–98; see also Joseph F. Smith, Gospel Doctrine: Selections from the Sermons and Writings of Joseph F. Smith, comp. John A. Widtsoe, 5th ed. (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1939), 656.

[23] Carole Call King donated her collection of letters to the CHL on 6 July 2001; see MS 16763, Carole C. King Collection, 1854–1916.

[24] Shirlee Passey Williams, Verna Passey Call’s sister, donated several letters, including letters from Joseph F. to Martha Ann, to the CHL. Barry K. Williams provided Carole Call King with additional letters on 19 July 2000.

[25] The fact that Joseph F. kept copies of his letters may suggest that he was concerned about the future interpretation of his life and wanted to preserve his own viewpoint. Another possibility is that he kept copies of his letters so he could reference them as needed. We appreciate Nathaniel R. Ricks for sharing this insight.

[26] When the transcription of a nonextant letter is based on a copy found in the letterpress copybook, we have noted this in the first footnote.

[27] Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 22 May 1890, herein.

[28] Barbara Rhodes and William Wells Streeter, Before Photocopying: The Art and History of Mechanical Copying (New Castle, DE: Oak Knoll Press & Herald Bindery, 1999), 113.

[29] Rhodes and Streeter, Before Photocopying, 9.

[30] JoAnne Yates, Control through Communication: The Rise of System in American Management (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1989), 26–28.

[31] Inside the letterpress copybook is a sticker that reads “W. Pitt & Co. Wholesale Stationers, and Account-book Manufacturers, 2, Strand Street, Liverpool.” Joseph F. Smith Family papers, Annie Clark Tanner Western Americana Collection, Special Collections Department, J. Willard Marriott Library, University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

[32] Joseph F. Smith letterpress copybook, 17 July 1874 through 31 December 1876.

[33] These letterpress copybooks are located in the CHL. They cover 7 January–20 July 1875; 19 July 1875–7 September 1879; 6 June–10 December 1877; 9 September 1879–12 September 1883; 18 May–16 June 1880; 19 September 1881–15 January 1884; 14 September 1883–14 March 1890; 18 January 1884–3 May 1889; 12 November 1885–4 March 1886; 17 March 1890–1 May 1891; 1 May 1891–25 November 1882; 26 November 1892–19 March 1895; 4 September 1896–1 April 1898; 5 April 1898–20 November 1899; 23 November 1899–3 February 1902; 2 February 1902–4 April 1905; 2 April 1905–1 May 1907; 4 May 1907–19 September 1909; 20 September 1909–26 February 1912; 9 March 1912–7 November 1914; and 7 November 1914–27 March 1917.

[34] The first example of an extant original letter that has a copy preserved in a letterpress copybook is Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 31 March 1875, herein.

[35] See Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 6 August 1895; 27 September 1895; [1 November] 1895; 28 March 1896; and 21 April 1896, herein.

[36] Joseph F. Smith letterpress copybook, 29 August 1888, 139, in private possession. Courtesy of Mark L. and Mary Ann McConkie.

[37] Joseph F. crossed oceans many times in his life, beginning in 1854. Martha Ann had no such opportunity. In 1914 Joseph F. arranged for his seventy-three-year-old sister to see the Pacific Ocean. See Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 24 June 1914; and Martha Ann to Joseph F., 7 July 1914, herein. This was not the last time Joseph F. arranged for her to spend time in Southern California.

[38] An independent kingdom between 1810 and 1893, Hawai‘i became an independent republic briefly from 1894 through 1898, when it was annexed by the United States as a territory.

[39] Utah was organized as an incorporated territory of the United States on 9 September 1850 by the Organic Act of Congress in 1850 and became the forty-fifth state on 4 January 1896.

[40] Women voted in Utah between 1870 and 1887 but were disenfranchised by the United States government during the battle over plural marriage.

[41] See Carol Cornwall Madsen, An Advocate for Women: The Public Life of Emmeline B. Wells, 1870–1920 (Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Press; Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2006), 250–51, 303.

[42] See Lisa Olsen Tait, “‘A Modern Patriarchal Family’: The Wives of Joseph F. Smith in the Relief Society Magazine, 1915–19,” in Manscill et al., Joseph F. Smith: Reflections on the Man and His Times, 74–95; and Edith E. Smith Patrick, comp., Brief Histories of the Family of President Joseph F. Smith and Julina L. Smith (n.p., n.d.). See appendix A (Joseph F.’s wives and children) and appendix B (Martha Ann’s husband and children).

[43] The reunions were announced in the Provo newspaper, inviting all family members to attend. See, for example, “Harris Family Plans Annual Reunion,” Daily Herald, 13 May 1930, 3 (held at the Provo Sixth Ward). In 1947 the general public was invited to an annual reunion where a special program took place at the Joseph Smith Building at Brigham Young University in honor of the pioneer centennial; see “Pageant to Depict Life History of Ancestors at Harris Reunion,” Daily Herald, 5 June 1847, 7.

[44] Joseph F. mentions receiving more than eighty letters from Martha Ann that are no longer extant. The one he mentions was written in 1855: “Your kind and affectionate letter of March 31st [1855].” See Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 9 June 1855, herein. The last letter mentioned by him was in 1916, “Your Card of gratulation in remembrance of myself and Nov. 13th and that of Artie’s, reached me this morning.” See Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 14 November 1916, herein.

[45] See Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 21 May 1880, herein.

[46] See Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 17 April 1857, herein; see also Joseph F., journal, 26 June 1856.

[47] Martha Ann to Joseph F., 17 December 1856, herein.

[48] See Joseph F., journal, 26 June 1856; and Martha Ann to Joseph F., 17 December 1856, herein.

[49] Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 17 April 1857, herein.

[50] Joseph F., journal, 29 April 1862.

[51] Joseph F. to John L. Smith, 21 May 1883.

[52] Ellsworth, Dear Ellen, x.

[53] The Deseret Telegraph Company was formed in 1867 and connected Latter-day Saint settlements along the Wasatch Front, both north and south.

[54] See Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 16 June 1899, herein.

[55] See Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 6 November 1911, herein.

[56] Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 25 July 1857, herein.

[57] Joseph F. to William J. Harris Jr., 9 September 1881.

[58] Julina Smith to Joseph F., 17 May 1868.

[59] Joseph F. to George C. Smith, 23 November 1898.

[60] Joseph F. to Alice Smith, 24 September 1898.

[61] Joseph F. to Alice Smith, 12 December 1898.

[62] Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 27 September 1895, herein.

[63] Joseph F. and Martha Ann’s many letters to other people have also survived. For letters by Martha Ann, see Carole Call King, “History of Martha Ann Smith Harris, 1841–1923” (unpublished manuscript in editors’ possession), 97–100, 141–44, 294–95, 302–3.

[64] Hyrum’s older children, Joseph F. and Martha Ann’s half siblings, also took interest in their welfare. However, Joseph F. never fully trusted his older half brother John’s ability to handle finances and manage his life; see letters from Joseph F. to John Smith in the CHL (MS 2861). Additionally, Mercy Fielding Thompson also served as a surrogate mother to her niece and nephew.

[65] Martha Ann to Joseph F., 31 May 1874, herein.

[66] Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 13 October 1898, herein.

[67] Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 24 December 1869, herein.

[68] Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 25 August 1877, herein.

[69] For example, Joseph F. borrowed five hundred dollars to pay taxes in 1895 and sold some property at a loss the following year to again pay taxes; see Smith and Kenney, From Prophet to Son, 30. Nevertheless, he purchased train tickets for Martha Ann and William during this economically challenging period; see Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 16 November 1896, herein.

[70] See other examples: Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 1 February 1906, 24 December 1910, and 19 December 1916, herein.

[71] See Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 8 March 1907, herein.

[72] See Joseph F., journal, 9 April 1862.

[73] Levira Annette Clark Smith.

[74] Mary Fielding Smith, Joseph F. and Martha Ann’s mother, died on 21 September 1852.

[75] Martha Ann to Joseph F., 3 April 1863, herein.

[76] Her letters may provide additional perspectives into the male-female dynamics within the broader Latter-day Saint marriage structure.

[77] An incomplete letter found in the CHL (Carole C. King Collection, 1854–1916, MS 16763, fragment 4) consists of four pages of a larger letter. These pages represent pages two, three, four, and five as indicated by the last page being marked as “Page 5.” This letter is in Joseph F.’s handwriting. These pages are undated and do not contain a general greeting or salutation. Internal evidence suggests that this was written while Joseph F. was serving his first mission in England (1860–63), because it mentions his wife Levira and compares the weather of England and America. There are twelve lines before Joseph F. begins a new paragraph, “Dear William.” This is followed by ninety-three lines apparently addressed to William Jasper Harris. This may be a letter within a letter and, if so, could be to Martha Ann. But because of the uncertainty, we have not included this fragment as part of the collection, and it is not represented in the numbers above.

[78] See Kenney, “Before the Beard,” 26.

[79] Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 18 October 1855, herein.

[80] Joseph F. to Hyrum M. Smith, 17 December 1896; see Smith and Kenney, From Prophet to Son, 52.

[81] See Stanley B. Kimball, Historic Sites and Markers along the Mormon and Other Great Western Trails (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1988).

[82] See Ricks, “My Candid Opinion,” xiv–xvi.

[83] Bowman, “Scholarly Inquiry.”

[84] For Willie, Martha Ann’s son, Joseph F. supplied pens, paper, envelopes, and stamps to help defray the cost of writing letters to him. See Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 18 January 1870; and Martha Ann to Joseph F., 13 December 1916, herein. Martha Ann was also running a household and often had little spare time for self-improvement.

[85] Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 21 April 1896, herein.

[86] See, for example, David M. Whitchurch, “The Pedagogy of a Church Leader: Lessons Learned from Joseph F. Smith’s 1854–1916 Letters to His Sister, Martha Ann Smith Harris,” Religious Educator 2, no. 2 (2001): 83–107.

[87] See Smith and Kenney, From Prophet to Son, 89.

[88] Located about seventy-five miles southwest of Salt Lake City in Skull Valley, Iosepa (the Hawaiian equivalent for Joseph) was a Latter-day Saint Polynesian settlement established primarily for Hawaiian members who had immigrated to Utah beginning in 1889. More than two hundred people lived in the community before it was abandoned following the plans to build a temple at Lā‘ie, O‘ahu, Hawai‘i, in 1917. See Matthew Kester, Remembering Iosepa: History, Place, and Religion in the American West (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013).

[89] See, for example, “Extracts from Letters of Elder Joseph F. Smith to His Family,” Woman’s Exponent 6, no. 9 (1 October 1877), 67.

[90] See, for example, Reid L. Neilson and Nathan N. Waite, eds., Settling the Valley, Proclaiming the Gospel: The General Epistles of the Mormon First Presidency (New York: Oxford University Press, 2017.

[91] An excerpt is available via YouTube: http://

[92] The location of the original recording cylinder is unknown at this time.

[93] “Record Transcription,” New Era, January 1972, 66.

[94] Joseph F. to Alvin F. Smith, 10 August 1905; and Smith and Kenney, From Prophet to Son, 89.

[95] Joseph F. to Arthur L. Thomas, 30 September 1898.

[96] Joseph F. to David A. Smith, 12 December 1898.

[97] Joseph F. to George C. Smith, 8 November 1898.

[98] Joseph F. to Edna M. Smith, 16 December 1898.

[99] Joseph F. to Louise S. Smith, 12 July 1899.

[100] Joseph F. to E. Wesley Smith, 17 May 1908.

[101] As noted above, his diaries for the period from his arrival in Hawai‘i in September 1854 to the end of 1855 were lost in a fire in June 1856, so his letters from that period are important to help reconstruct his personal history.

[102] Like Joseph F.’s letter collection, Martha Ann’s letters are mostly found in the Church History Library, with a few others scattered among family members.

[103] See Martha Ann to Joseph F., 31 January 1856, herein; and Martha Ann to Joanna Spears, [Fall] 1920.

[104] Martha Ann also engaged in a lifetime correspondence with many of her extended family members, in particular her sisters-in-law, the wives of Joseph F. See, for example, Martha Ann to Julina Smith, 21 December 1889.

[105] E. Wesley Smith to Martha Ann, 27 January 1923; original spelling preserved.

[106] Martha Ann to Joanna Spears, 1920.

[107] See, for example, Martha Ann to Joseph F., 2 March 1856, herein; and Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 12 November 1883, herein.

[108] In Martha Ann’s letter collection are a number of letters written to her that mention additional letters she had written that are not extant. As noted, Joseph F. mentioned as many as eighty letters he had received from Martha Ann that have not survived.