Decade Introduction

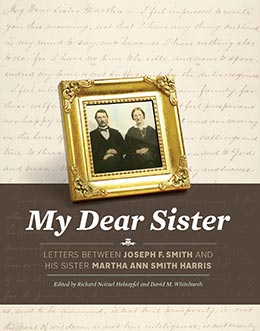

Richard Neitzel Holzapfel and David M. Whitchurch, "Decade Introduction," in My Dear Sister: Letters Between Joseph F. Smith and His Sister Martha Ann Smith Harris, ed. Richard Neitzel Holzapfel and David M. Whitchurch (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2019), 441–466.

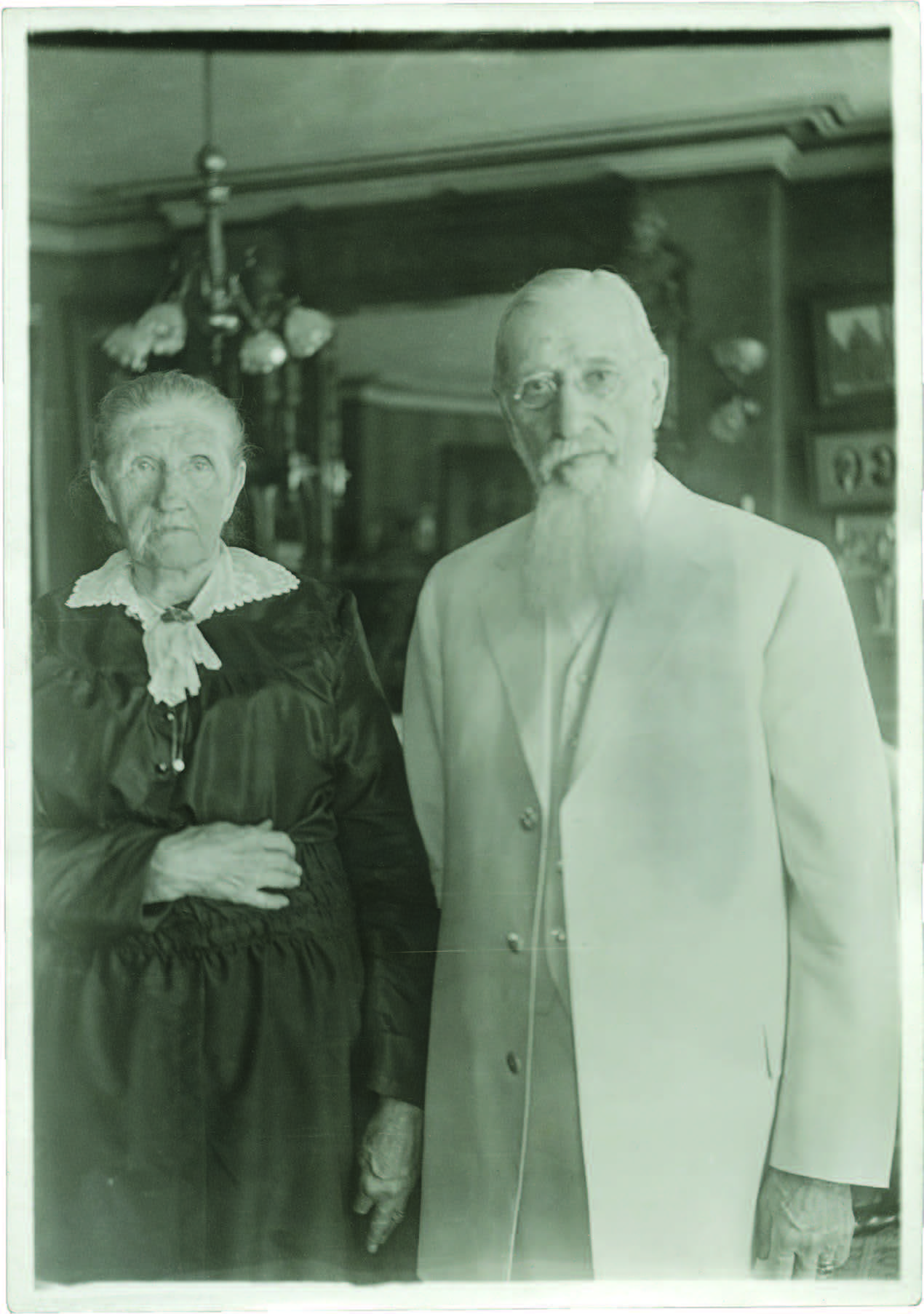

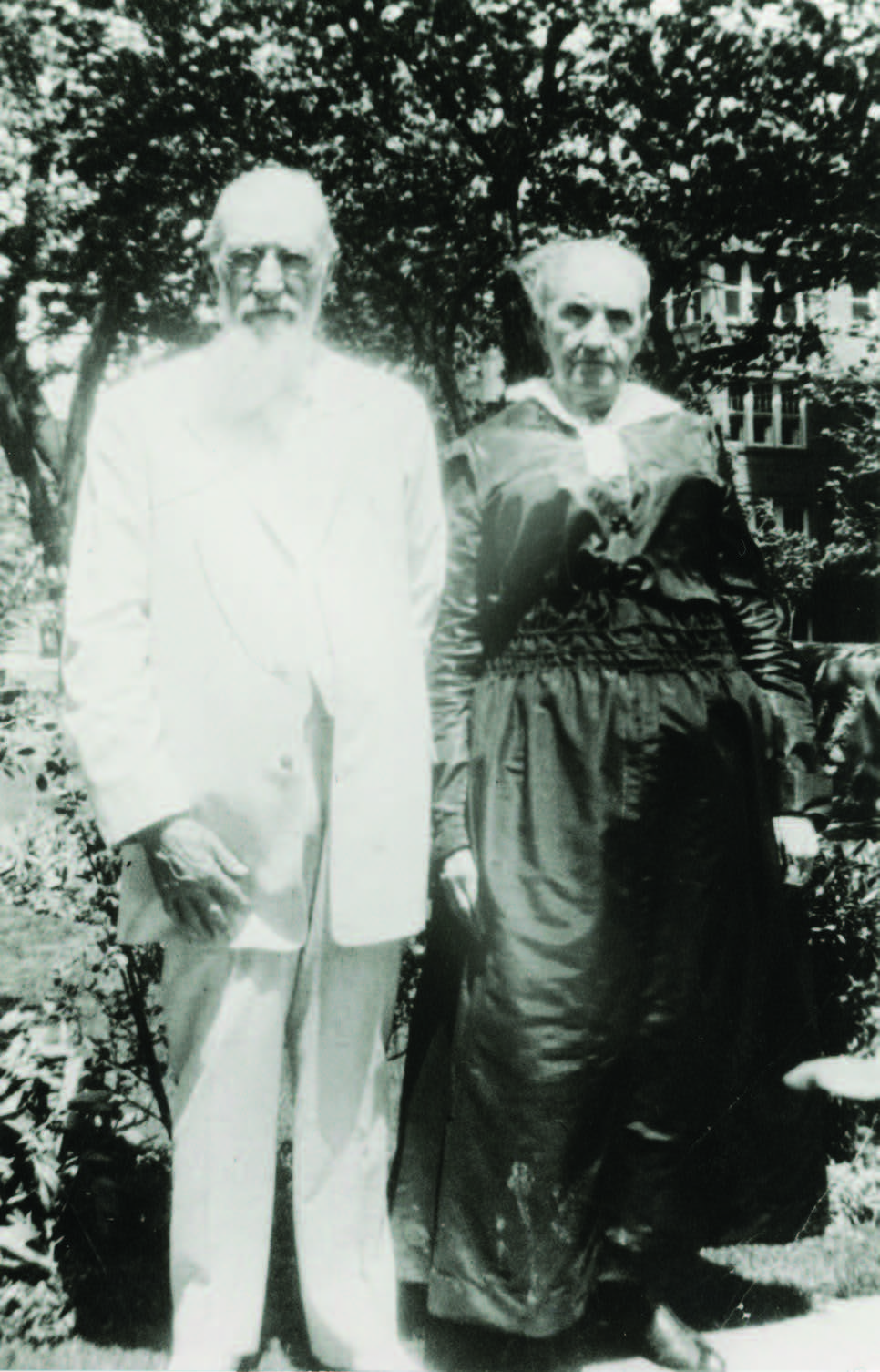

Martha Ann Smith Harris and Joseph F. Smith, 5 May 1916. Courtesy of Carole Call King.

Martha Ann Smith Harris and Joseph F. Smith, 5 May 1916. Courtesy of Carole Call King.

When Joseph F. became President of the Church in 1901, he had served in the First Presidency since 1880. No other Church President had been a member of the First Presidency before being called to preside over the entire Church. Additionally, Joseph F. had served more missions overseas than his predecessors, a record that has not been broken since his time.[1] He also visited the Saints around the world and was the first Church President to visit members outside the Latter-day Saint core area while serving in that capacity.

A Foundation for the Twentieth and Twenty-First Centuries

During President Joseph F. Smith’s administration, the Church was beginning to establish a permanent presence throughout the world that would become the basis for its explosive growth in the second half of the twentieth century.[2] Membership increased significantly, from 283,765 in 1901, when Joseph F. became President, to 495,962 at the time of his death in 1918.[3] His presidency set the course for the Church in the next six decades and beyond.[4]

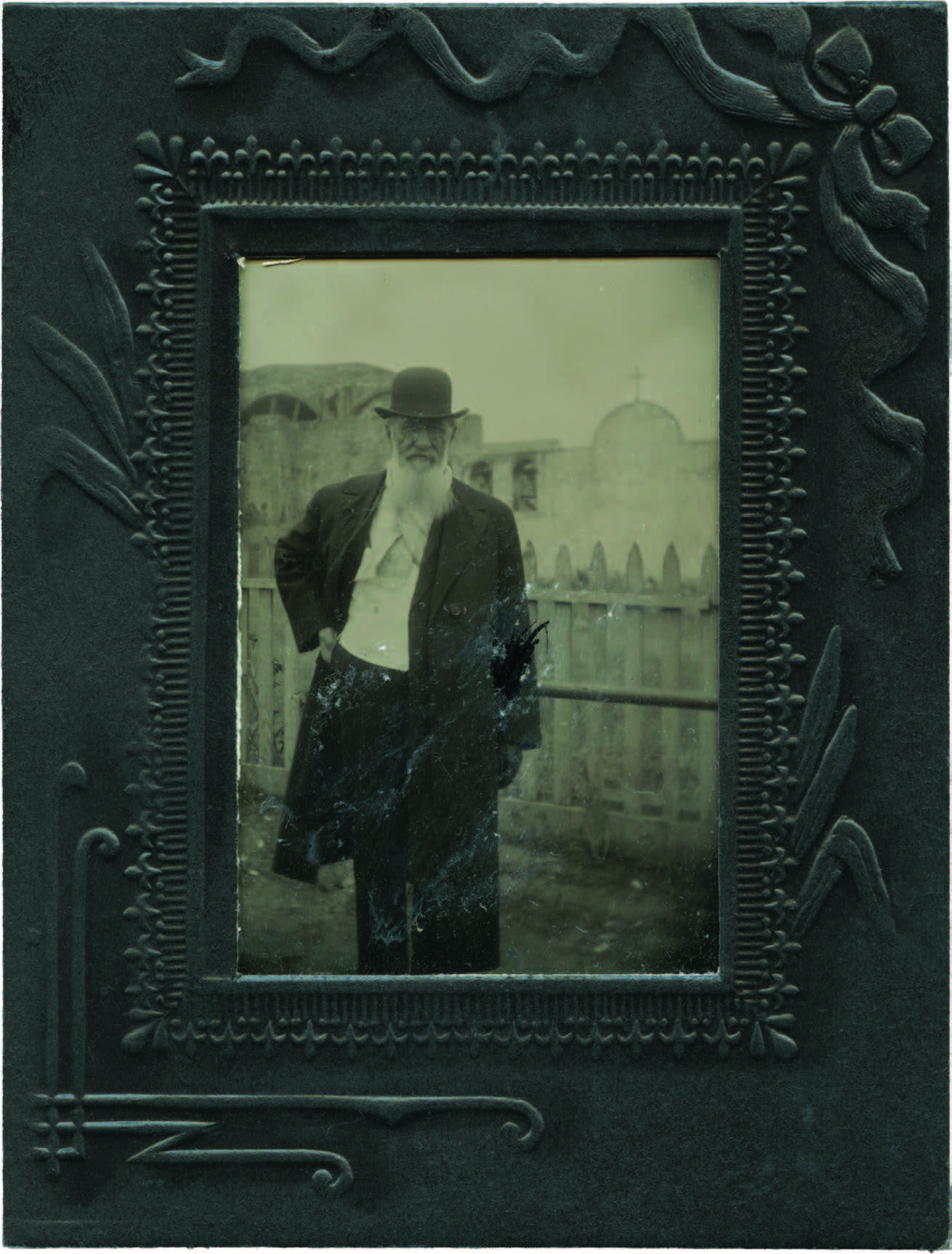

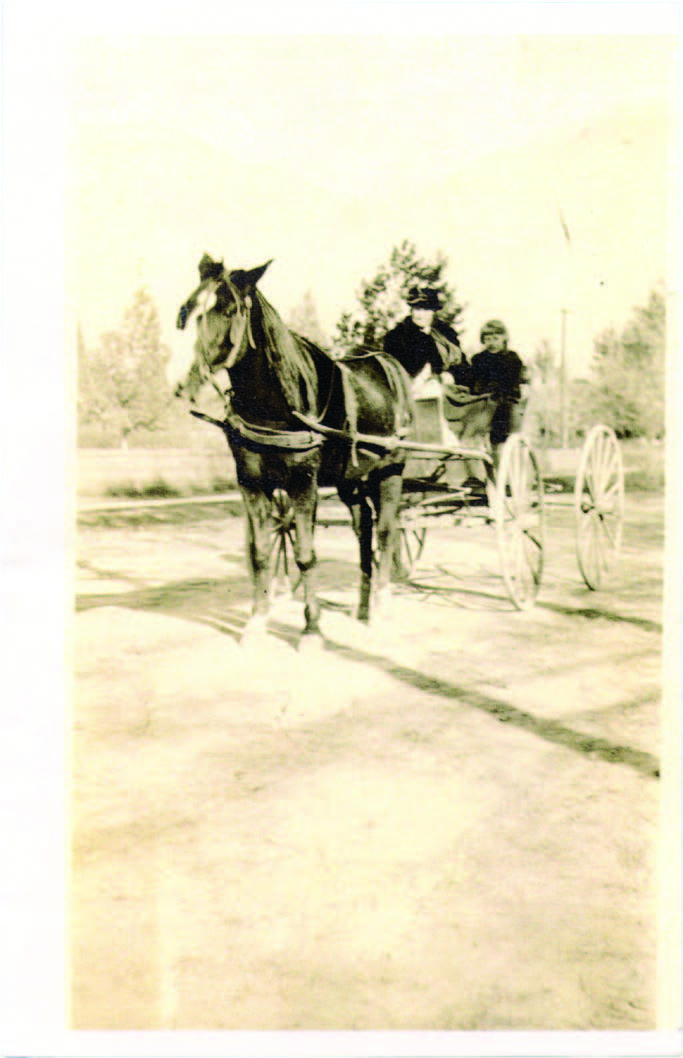

Joseph F. during a visit to Mexico in the last decade of his life. Courtesy of CHL.

Joseph F. during a visit to Mexico in the last decade of his life. Courtesy of CHL.

As the Church continued to retire its debts and began the process of moving from tithing-in-kind to cash donations, it was positioned to strengthen the infrastructure at its Salt Lake City headquarters by completing the Bureau of Information (1910), Bishop’s Building (1910), Business Building (1910), Deseret Gymnasium (1910), Hotel Utah (1911), and Church Administration Building (1917).[5]

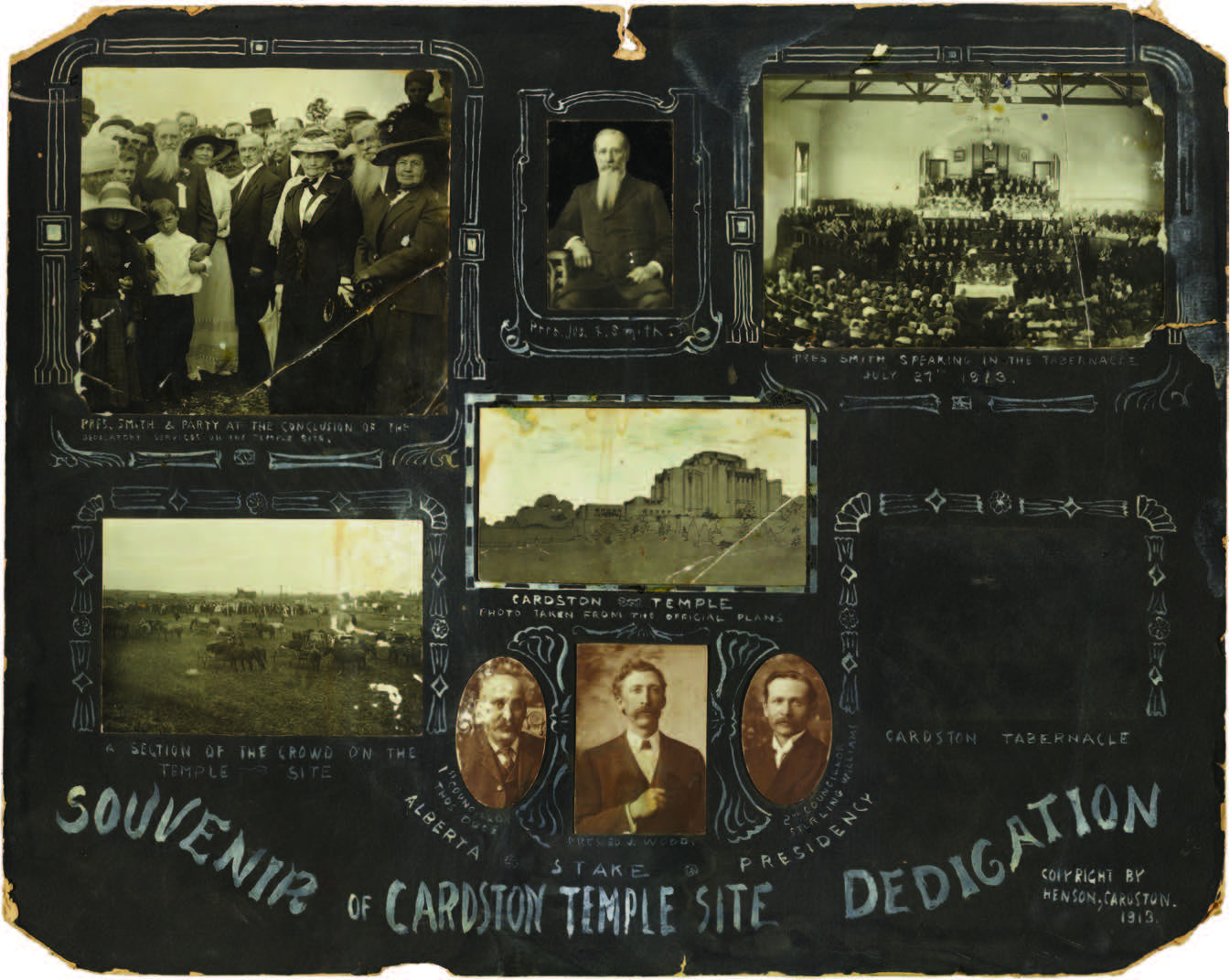

President Smith encouraged the Saints to remain where they lived in order to help build up the Church internationally. In February 1911 the First Presidency noted, “It is desirable that our people shall remain in their native lands and form congregations of a permanent character to aid in the work of proselyting.”[6] As he continued to meet the needs of a burgeoning membership outside Utah, President Smith participated in the groundbreaking and site dedication of two historic temples.[7] The first one was dedicated in Cardston, Alberta, Canada (1913),[8] and the other in Lā‘ie, O‘ahu, Hawai‘i (1915).[9]

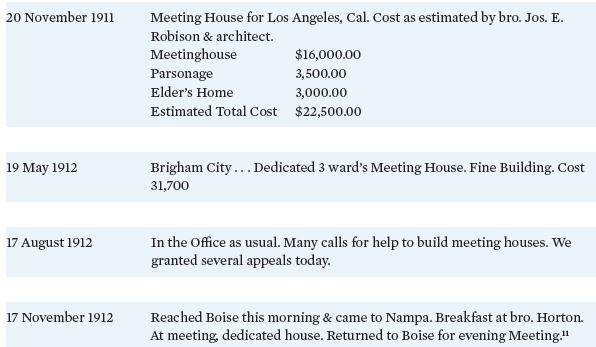

During President Smith’s administration, numerous local meetinghouses were planned, built, and dedicated throughout the Church—many beyond Utah’s borders—to accommodate and bless the lives of the Saints.[10] President Smith highlighted this effort in his 1911–12 journal:[11]

President Smith also supported the erection of many other Church-owned buildings in Utah. For example, he noted in May 1912, “Council at the Temple. Dedication Maeser building. To Provo at 4:30 p.m.”[12] He had presided over the cornerstone-laying ceremonies for the Karl G. Maeser Building in October 1909. The Maeser Memorial Building was the first building constructed on “Temple Hill,” the present-day site of Brigham Young University’s main campus.[13]

“Cardston Temple Site Souvenir,” 27 July 1913, photographs by Arthur Thomas Henson, Cardston, Alberta, Canada. Henson’s photomontage of temple groundbreaking ceremonies features images of Joseph F. Smith and local Church leaders and members, including a view of Joseph F. Smith and his party taken at the dedication (top left). Courtesy of CHL.

“Cardston Temple Site Souvenir,” 27 July 1913, photographs by Arthur Thomas Henson, Cardston, Alberta, Canada. Henson’s photomontage of temple groundbreaking ceremonies features images of Joseph F. Smith and local Church leaders and members, including a view of Joseph F. Smith and his party taken at the dedication (top left). Courtesy of CHL.

During this time of Church growth, new programs and organizational changes, such as the modern stake and ward structures, were being introduced.[14] Additional developments included the publication of the Children’s Friend (1902), a restructuring of the Mutual Improvement Associations (1903), Sunday School classes for adults (1906), weekly priesthood meetings (1909), the adoption of the Boy Scout program (1911), the beginning of the seminary program (1912), the publication of the Relief Society Magazine (1915), and the introduction of “Home Evenings” (1915).

Joseph F. Smith at the Maeser Memorial Building cornerstone-laying ceremony, 16 October 1909. Courtesy of BYU. Joseph F. is standing facing the camera to the right of the US flag.

Joseph F. Smith at the Maeser Memorial Building cornerstone-laying ceremony, 16 October 1909. Courtesy of BYU. Joseph F. is standing facing the camera to the right of the US flag.

During this decade, President Smith, along with members of the First Presidency and Council of the Twelve Apostles, issued major doctrinal statements.[15] For example, a statement issued on 30 June 1916 titled “The Father and the Son: A Doctrinal Exposition by the First Presidency and the Twelve” explains how the term Father is used in scripture as it relates to God.[16] Along with an earlier statement issued by the First Presidency in 1909, this important document demonstrates President Smith’s effort to clarify Church doctrine for the twentieth-century Church.[17]

A Personal Ministry

While presiding over an increasingly large Church membership scattered around the world, President Smith nevertheless took time to minister to individuals. In 1912 he wrote, “Office all day. Called at Melissas and prayed for her.”[18] In 1913 he recorded, “I baptized Robert S. Sant and confirmed him today in Font at Tabernacle, S.L.City. He is 8 years old today. I also baptized & confirmed Eloise Leilani Fernandez who will be 8 years old tomorrow.”[19] His journals and letters highlight this personal one-on-one attention generously extended to many people, including his beloved sister Martha Ann, throughout his ministry.

President Smith’s letters became an important way for him to extend his outreach to many more people than otherwise possible. This included people close by, such as his sister Martha Ann in Provo, as well as those farther away from Church headquarters. When he left Utah for an extended visit to California in 1912, President Smith recorded addresses of people he wanted to write while he was away from Utah—Martha Ann, two sons serving as missionaries in Europe, and other people not related to him, such as President Melvin J. Ballard (1873–1939), who was presiding over the Northwestern States Mission at the time.[20]

When President Smith returned home from any trip, many letters awaited his attention. After a trip to California, he noted, “Found all well at home and piles of letters to answer.”[21] A few days later, he recorded, “A.M. going over my personal letters.”[22] His journals and letters reveal a man dedicated to reading and writing letters on an almost daily basis. By 1912 he began receiving help with this increasing responsibility. He noted, “Read Letters. Met bro. Wally. At Temple. Prayed for Geo. Albert [Smith], C. W. & M Co. Meeting. I dictated letters.”[23]

Time Marches Forward

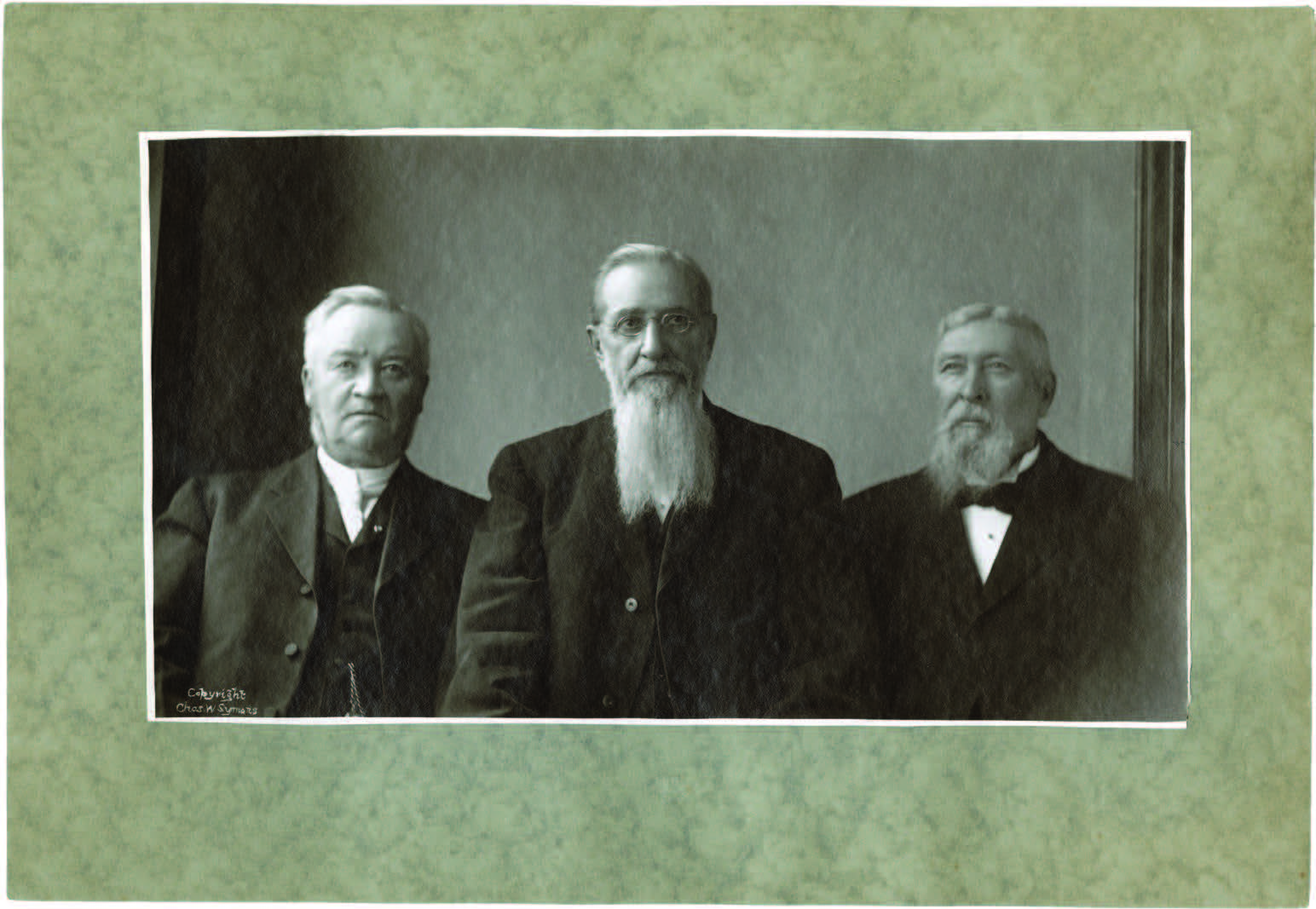

The decade of 1910 began with the death of John R. Winder (1821–1910), First Counselor in the First Presidency, on 27 March 1910. Anthon H. Lund (1844–1921), the Second Counselor, was sustained to replace him on 7 April 1910, and John Henry Smith (1848–1911), who had been serving as the President of the Quorum of the Twelve, was sustained as the new Second Counselor on the same day.[24] Before the end of the year, the newly reorganized First Presidency visited Heber Harris Thomas (1862–1926) to have a photograph taken.

The First Presidency, 30 December 1910, photograph by Heber H. Thomas. Courtesy of CHL. Left to right: Anthon H. Lund, Joseph F. Smith, and John Henry Smith.

The First Presidency, 30 December 1910, photograph by Heber H. Thomas. Courtesy of CHL. Left to right: Anthon H. Lund, Joseph F. Smith, and John Henry Smith.

A year and half later, on 13 October 1911, President John Henry Smith died, creating a vacancy soon filled by Charles W. Penrose (1832–1925). For a second time in Joseph F. Smith’s administration, the First Presidency consisted of two members born outside the United States (Lund was born in Denmark and Penrose in England).

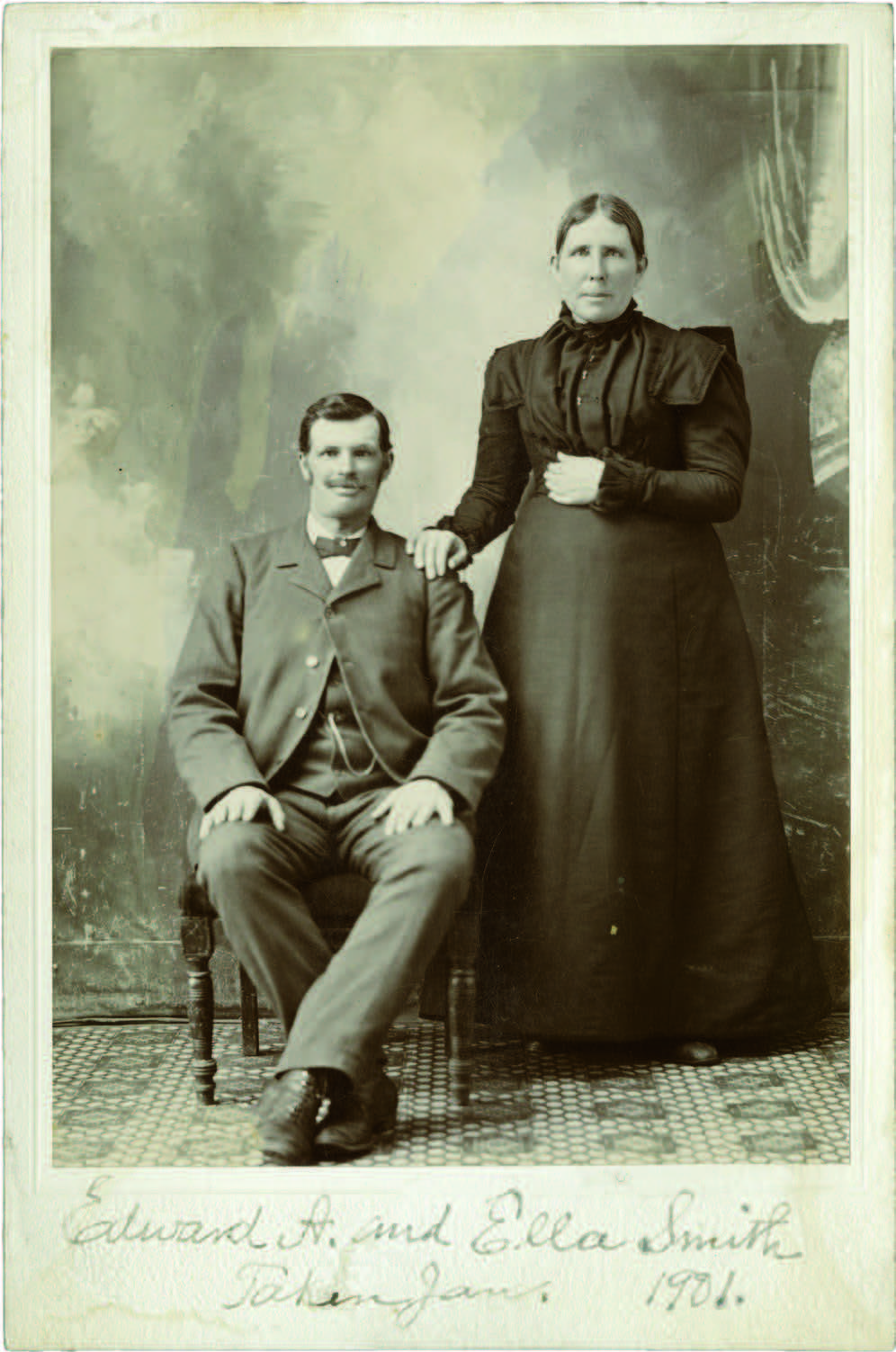

In the time between his first and last letters of this decade to Martha Ann, Joseph F. experienced personal losses in his immediate family, beginning with the death of his adopted son Edward Arthur (1858–1911) on 17 July 1911. Four years later, Joseph F.’s beloved wife Sarah Ellen Richards (1850–1915) died on 22 March 1915. Her passing was followed by the death of his daughter Zina (1890–1915) on 25 October 1915. Extended family members also died during this period, giving Joseph F. additional cause to weep and mourn for those close to him.

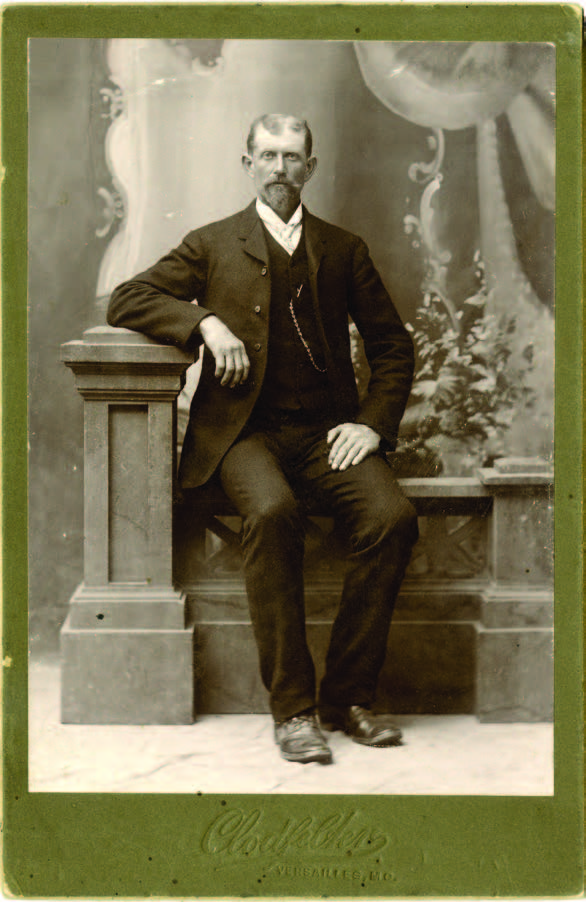

Edward A. and Cytha Ellen Smith, known as Ella Smith, January 1901. Courtesy of CHL. Ella Smith married Edward Arthur on 3 March 1881. They were the parents of eleven children. Edward, the adopted son of Joseph F., died on 17 July 1911. Joseph F. wrote on this card, “Edward A. and Ella Smith taken Jan. 1901.”

Edward A. and Cytha Ellen Smith, known as Ella Smith, January 1901. Courtesy of CHL. Ella Smith married Edward Arthur on 3 March 1881. They were the parents of eleven children. Edward, the adopted son of Joseph F., died on 17 July 1911. Joseph F. wrote on this card, “Edward A. and Ella Smith taken Jan. 1901.”

On the international scene, another death indirectly influenced the lives of Joseph F. and other Church members worldwide. The assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria on 28 June 1914 plunged Europe into war. In response to the outbreak of hostilities, that same year President Smith closed the missions in Europe, where the conflict was raging. Latter-day Saints living in Canada, particularly those from settlements in the western province of Alberta, and in the British Isles were immediately affected as husbands and sons marched off to join the conflict in Europe. With great anxiety and alarm, the European Saints witnessed the battles raging close to home.

When the United States officially entered World War I in April 1917, a large number of American Latter-day Saints from the western United States were sent to the battlefront in France. Six of President Smith’s own sons served during the war, which ended just days before his death in November 1918.

During his last year of life, President Smith experienced the heartache of death again and again when his son Hyrum Mack Smith[25] died in January following an appendectomy, his son-in-law Alonzo Pratt Kesler[26] died in February after falling from a ladder, and his daughter-in-law Ida Bowman[27] died in September after childbirth.

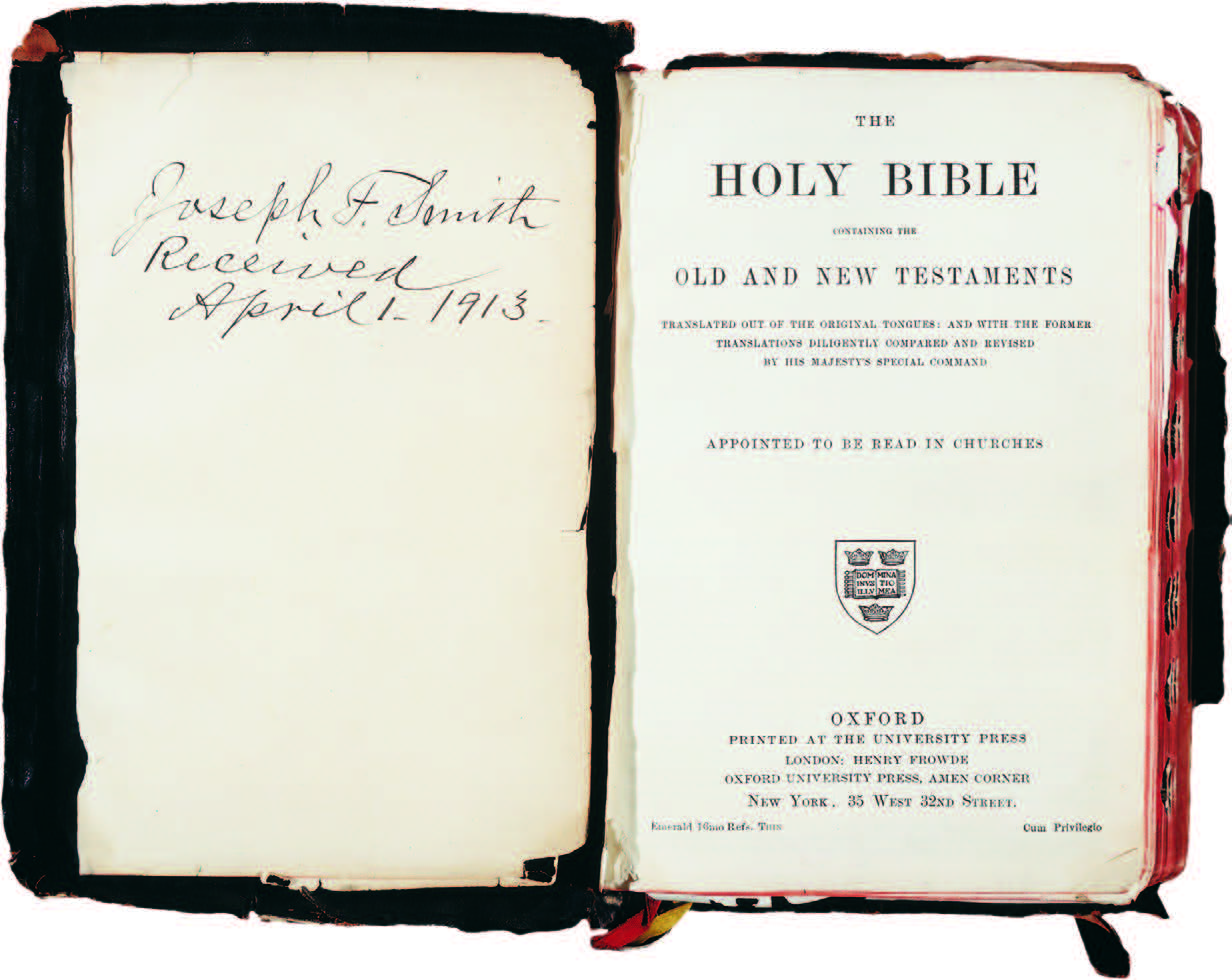

Joseph F.’s King James Version Bible, “Received April 1. 1913.” Courtesy of CHL. This may have been the Bible he was studying in October 1918 when he beheld a vision of the redemption of the dead.

Joseph F.’s King James Version Bible, “Received April 1. 1913.” Courtesy of CHL. This may have been the Bible he was studying in October 1918 when he beheld a vision of the redemption of the dead.

During the last few months of his life, President Joseph F. Smith was mostly confined to the Beehive House, his home in Salt Lake City. It was in this setting that he beheld on 3 October 1918 a magnificent vision of the redemption of the dead.[28]

The vision came to Joseph F. at a terrible personal cost through decades of burying family members one by one. One scholar noted the following:

One of the things that becomes obvious almost immediately is that Joseph F. Smith was acutely acquainted with death from the time of his father’s murder [in] 1844 until the death of JFS’s favored son in 1918, just months before JFS himself died. The decades in between were liberally sprinkled by the loss of many children. JFS grieved deeply the loss of each one. On August 26, 1883, JFS wrote to his sister Martha Ann that “Once more, and now for the sixth time, by the inexorable will of an inscrutable providence, we have been called upon to part with one of our dearest, most precious treasures. This time the pitiless monster, death, has chosen for his ‘shining mark,’ our beautiful, intelligent, bright and lovely little Albert Jesse [2 years old]. . . . [Despite] scalding tears, the heavens were brass above our heads. Our cries and tears fell alike to the earth and were buried this day with the lifeless form of our hearts treasure in the grave! And yet not all were buried, for our cry would ascend: why is it so? Why, God, did it have to be? And still our tears soak the earth to releave, if not to bury, our heartache in its lifeless bosom.”[29]

This would not be the last time that JFS buried a child who had died in his arms. It would not be the last time that he found the heavens as brass over his head. I think now of what we know as Doctrine and Covenants 138. The Vision of the Redemption of the Dead. We’ve studied its theology; we’ve contextualized it and given a nod to the role of World War One and Smith’s own impending death. But we have not, I think, yet reckoned with the full cost of that revelation. It seems to me that the gift we were given in that text was extruded from Joseph F. Smith, dead child by dead child, over the course of decades. God did not kill those children so that we could have this revelation. But God certainly used those experiences to deepen the well of yearning that a prophet seems to need in order to see beyond himself and into the heart and mind of God. That revelation cost this prophet dearly. . . . I cannot look at that revelation the same way anymore. In it resides the buried treasures lost by a prophet. In it we see the brass heavens break. Finally.[30]

The vision was grand and comforting for Joseph F. On a deeply personal level he mentions seeing his father, Hyrum Smith, who had been murdered in 1844.[31] Within two months after receiving this momentous revelation for the Church, Joseph F. was dead, five days after his eightieth birthday.[32]

Martha Ann’s Mixed Experiences

The conflict in Europe also affected Martha Ann’s life in Provo. For one thing, her grandson John Alvin Corbett (1897–1962), like several other Smith extended family members, was a soldier in France during the war. In a letter from “somewhere in France” and written to his grandmother Martha Ann, John wrote, “No one realizes what the world is till he gets out and gets into a place like this.”[33] He further reflected, “Of course, we have to consider that France has had 4 yrs of careless war and the flower of her youth have surely suffered. Only the women left you might say to do the work with the old and the young.” He then opined, “The people have brought this terrible thing on themselves through their disobedience to the laws of God and not listening to his teachings. Only something like this can bring them to their senses.”[34]

John Alvin Corbett, ca. 1918. Courtesy of Carole Call King.

John Alvin Corbett, ca. 1918. Courtesy of Carole Call King.

Before the outbreak of World War I, Martha Ann celebrated the birth of another granddaughter, Ann Adalaide Dennis (1910–2008). She was the daughter of Martha Ann’s daughter Zina Christine (1876–1958) and John Thomas Dennis (1866–1929). Zina and John’s marriage in 1909 was unique and must have given Martha Ann additional reasons to celebrate. John had previously married Martha Ann’s third daughter, Mercy Ann (1874–1905). Four years after her death in 1905, John married her younger sister, Zina Christine Harris Furner, Martha Ann’s fourth daughter. Zina Christine’s first husband, George Thomas Furner (1868–1902), had died in 1902, leaving her a widow with four young children: Merrilla (1895–1967), Zina May (1897–1934), Pearl Irene (1900–1987), and Sarah Rachel (1902–77). Zina and John had three children together; Ann Adalaide was the first, born on 12 July 1910.[35]

Zina Christine with her daughter, Ann Adalaide Dennis, 1910. Courtesy of Carole Call King.

Zina Christine with her daughter, Ann Adalaide Dennis, 1910. Courtesy of Carole Call King.

Martha’s son Joseph Albert died during the spring of 1911. According to a family tradition, Joseph Albert was robbed and severely beaten on a train on his way home from Texas where he had been visiting his brothers. “When he arrived at the Provo depot, he was put in a strait jacket and taken to the Utah State Mental Hospital. He didn’t recognize any of his family when he arrived.”[36] Upon hearing of Joseph Albert’s death, Joseph F. wrote his sister: “My Dear Sister Martha Ann:— I got the sad word last evening thro’ Julina, that Joseph Albert had passed over the dark river to the great majority beyond. While it is always sad and sorrowful to pass thro’ the gloomy shadows of the dark valley of death, there are some things much worse than death itself. A living death is more to be dreaded than the final sleep, and rest from the fatal ills of mortality. Joseph is all right now. He is beyond the power of death.”[37]

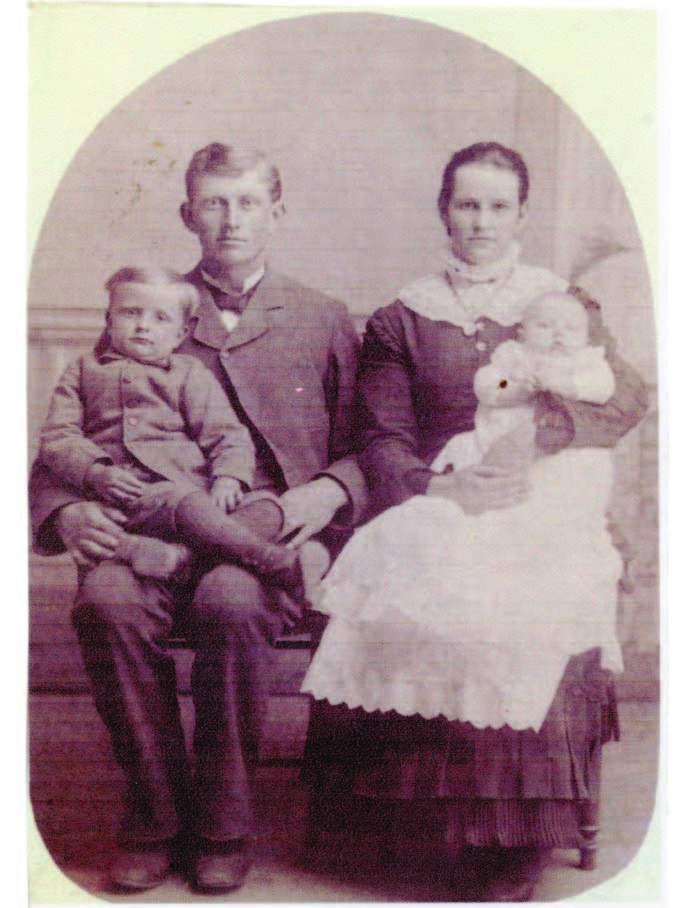

Joseph Albert Harris and Johanna Patten with “Burt” and “Frank,” ca. 1883. Courtesy of Carole Call King.

Joseph Albert Harris and Johanna Patten with “Burt” and “Frank,” ca. 1883. Courtesy of Carole Call King.

In July 1912, Martha Ann accompanied her brother to Southern California for a monthlong vacation. Joseph F. recorded in mid-July, “Edna L., Emma, and Martha, Lucy, Edith and I Started for Ocean Park Cal. We have 2 trunks & Satchels.”[38] The group traveled by train in a sleeping car, making the journey south through the desert a pleasant one. Joseph F. noted, “a.m. cool and pleasant p.m. warm.”[39] Wanting Martha Ann to enjoy her time in Southern California without any financial worries, Joseph F. took care of the expenses.[40]

Joseph F. Smith at Santa Monica, Los Angeles County, California, ca. 1914. Courtesy of Annie Clark Tanner Western Americana Collection, Special Collections Department, J. Willard Marriott Library, University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

Joseph F. Smith at Santa Monica, Los Angeles County, California, ca. 1914. Courtesy of Annie Clark Tanner Western Americana Collection, Special Collections Department, J. Willard Marriott Library, University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

Martha Ann went fishing, apparently became seasick, and, along with everyone else, did not catch any fish. Sometimes Joseph F. and Martha Ann remained alone at the cottage while everyone else traveled somewhere nearby. On one occasion, Joseph F. noted in his journal, “I was writing letters all day.”[41] A day after arriving home in Salt Lake City on 14 August, Joseph F. briefly noted, “Found all well at home and piles of letters to ans[wer].”[42] Overall, the trip to California provided Martha Ann with a well-deserved respite from the crush of daily work and other obligations in Provo.

Less than a year later, Martha Ann’s son-in-law Walter Sutton Corbett (1857–1912) died on 2 February 1912 at his home in Pleasant View.[43] The following month, Joseph F. noted in a letter to the local stake president in Provo that Mary Emily Harris (1865–1947), Walter’s wife, owed about two hundred dollars “for the burial of her husband and two children” and “a mortgage of some $600 or more on her house.”[44] Joseph F. had interceded to help his niece reduce her expenses and coordinate a final settlement of the bills by a group of friends and family members.

Tragedy struck again just months later when Mary Emily lost a daughter-in-law, Irene Colvin Corbett (1881–1912). Irene was married to Walter Harris Corbett (1885–1917), Mary’s son and Martha Ann’s grandson. At the time of her death, she was the mother of three children: Walter Colvin (1906–2002), Kady Roene (1908–73), and Mark Colvin (1910–76).

Irene had earned a degree at Brigham Young Academy in Provo, Utah, and then desired to continue her education by attending school in England. Her husband and some close Harris family members opposed her choice. Undeterred, she traveled to Salt Lake City with her father, Levi Alexander Colvin (1857–1928), to obtain a blessing from Joseph F., her great uncle-in-law, before departing. To her surprise, President Smith advised her to go to school on the East Coast instead of in England.[45] Nevertheless, with her parents’ help and support, Irene decided to go forward with her plans and made her way to England. The Salt Lake Tribune reported that Irene “went to England last October to study obstetrics.”[46] She spent 1911–12 in London training at the General Lying-In Hospital, where a photograph was taken, the last known image of Irene.

Irene Colvin Corbett (standing, second row on left), London, England, ca. 1911–12. Courtesy of Don Corbett. This image was sent to Martha Ann by her grandson’s wife Irene just weeks before she began her journey back to the United States.

Irene Colvin Corbett (standing, second row on left), London, England, ca. 1911–12. Courtesy of Don Corbett. This image was sent to Martha Ann by her grandson’s wife Irene just weeks before she began her journey back to the United States.

Concluding her studies there in 1912, Irene sent Martha Ann the photograph of herself and the other nurses taken in London and a poignant note in which she mentioned the challenges she faced when she decided to leave Utah to attend school in England the year before. Irene still felt hurt by her husband’s opposition and President Smith’s counsel: “In Going through the struggle here alone in the world I felt to resent Walter’s [her husband] and Pres. Smith’s remarks toward my father [Levi Colvin, who had mortgaged his farm to pay for her travel and school expenses] who is doing so much for me and has done for us all along. . . . My [nursing] course here has just about been ‘all work and no play.’” As is sometimes the case in history, she then penned what would become a tragic and ironic line, “But expect to enjoy my trip home better.”[47]

Tragically, three weeks after writing this note and sending the photograph, she took passage on the RMS Titanic, which sank in the North Atlantic on 15 April 1912, less than three hours after colliding with an iceberg.[48]

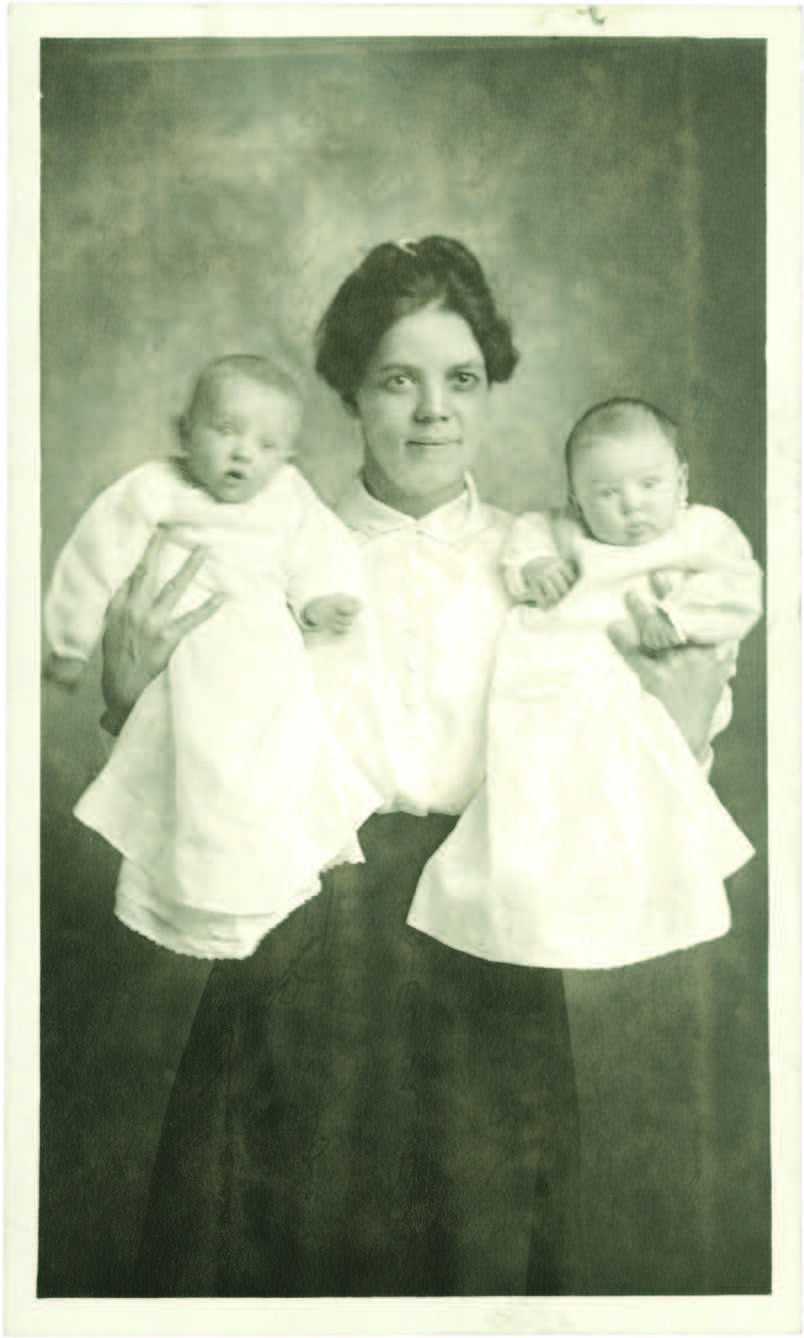

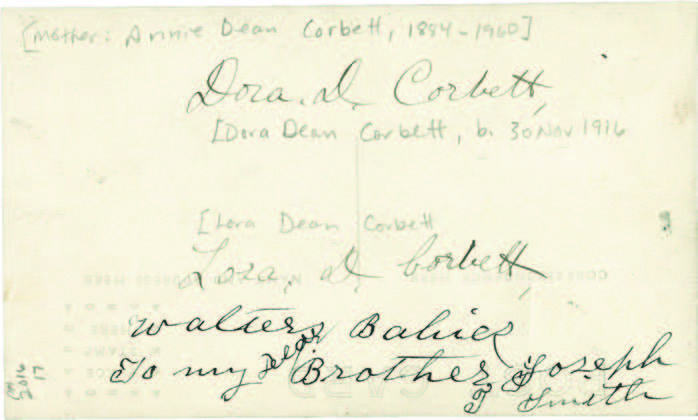

Walter married again in November 1914, but a year later he and his wife, Annie Dean (1884–1960), lost their first baby, Mary. A year later, on 30 November 1916, Annie delivered twin girls, Lora (1916–2006) and Dora (1916–75). This double joy was replaced with sadness when Walter died in February 1917 at the age of thirty-one.

Annie Dean Corbett and her two twins, Lora and Dora, ca. 1917. Courtesy of CHL. Martha Ann wrote, “Walter’s babies To my Dear Brother Joseph F Smith.”

Annie Dean Corbett and her two twins, Lora and Dora, ca. 1917. Courtesy of CHL. Martha Ann wrote, “Walter’s babies To my Dear Brother Joseph F Smith.”

In 1913 Martha Ann informed Joseph F. of a fire at her home.[49] This setback, along with other challenges, required Martha Ann to move back into the adobe home.[50] Letters between her and Joseph F. during this period often mention concerns with the annual property tax payment.[51] Martha Ann was unable to make the full payment in 1916, resulting in a tax sale. She obtained a mortgage release on 23 September 1918, and the following month, just weeks before Joseph F. died, the property was transferred to the Provo Sixth Ward Corporation of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.[52]

An event that brought much joy to Martha Ann during this period was the publication of an article about her mother, Mary Fielding Smith, that included photographs of Joseph F.’s and Martha Ann’s families in the Church’s Relief Society publication.[53] In January 1916 Martha Ann received a letter from Susa Young Gates (1856–1933), founder and editor of the Relief Society Magazine:

Dear Aunt Martha: I am just now sending you the picture which you lent me of your little family. Aunt Edna let me have your other group, and we are now working on the magazine. I hope to have it out in a week or ten days, when I will try and remember to send you a copy. . . . I wrote a little something about yourself, which I hope will prove satisfactory. President Smith has gone over the article very carefully and approved of it all. There is a very beautiful picture of your mother beside the other family groups. I hope you will like it all. May the Lord bless you and heal your body and comfort your spirit, is the prayer of, your living friend and sister, Susa Young Gates.[54]

When the March issue of the Relief Society Magazine appeared, readers were introduced to Mary Fielding Smith, Joseph F., and Martha Ann, along with information about their children.[55] Two photographs of Martha Ann and family members appeared in the article: (1) “Mrs. Martha A. Smith Harris, daughter of Mary Fielding Smith, and her three eldest boys” and (2) “William J. Harris and Martha A. Smith-Harris with their children.”[56]

The article acknowledged, “The people are not so well acquainted with Martha Ann Harris, the daughter of Mary Fielding Smith. For, like her mother, she is modest, retiring, and gentle. She is frugal and very industrious. . . . She has reared her family in the fear of the Lord and they have risen up to bless her in the gates.”[57]

During this decade, Martha Ann’s health continued to plague her as she aged. Her multiple accidents over the years had taken a toll. Joseph F. noted in a letter to their cousin, “Martha is still at her little home in Provo, in rather feeble health, but carrying the responsibility of maintaining her home, and caring for her two motherless grandchildren.”[58] A letter of hers in 1914 mentions some of the health problems she was facing at that time: “I am gaining sloly . . . while I have been here I have sufferd quite a bit with my knee & other ailments that I have to contend with. but I am very thankfull that I am as well as I am, at the present & hope & pray I may <still> be improving I got a pare of crutches & have yoused them some but I have been very week I could not get round mutch.”[59]

In February 1919 Vivian Clyde Safford (1896–1919), the husband of Martha Ann’s granddaughter Edna Mae, died, leaving behind his young wife and a newborn baby, Virginia Safford (1919–98). To support the family, Edna Mae worked during the day while seventy-eight-year-old Martha Ann watched the baby, performing as she had done so often before an act of service that revealed her innate gift of charity and reflected her unstinting devotion to her family throughout her life.[60]

President’s Home (Beehive House) and President’s Office, ca. 1914, C. R. Savage & Co., Salt Lake City, Utah. Courtesy of CHL. Martha Ann visited her brother at his home in Salt Lake City on numerous occasions, including at the annual and semiannual general conferences held in the spring and fall of each year.

President’s Home (Beehive House) and President’s Office, ca. 1914, C. R. Savage & Co., Salt Lake City, Utah. Courtesy of CHL. Martha Ann visited her brother at his home in Salt Lake City on numerous occasions, including at the annual and semiannual general conferences held in the spring and fall of each year.

During the latter part of her life, Martha Ann visited Salt Lake City whenever she could for general conference during President Smith’s administration. As her granddaughter Edna Mae Simmons recalled, “Grandmother went to Salt Lake for Conference every year—spring and fall—and stayed in the Beehive House where Uncle Joseph lived. There we had our own room and a bath to ourselves. Oh, how wonderful I thought it was! Then we ate in the large dining room at a big long table with Uncle Joseph at the head.”[61] During one visit, Martha Ann fell on the front steps of the Beehive House. Her granddaughter who had accompanied her recalled, “She went ‘a flying’ and broke her ribs. She convalesced in the Beehive House for several weeks.”[62]

Harris family reunion, 11 April 1917, photograph taken outside the Provo Sixth Ward building by George Edward Anderson, Provo, Utah. Front row: Mary Corbett, Martha Ann Harris, and William Harris Jr. Back row: Sarah Passey, Martha Startup, Zina Dennis, John Harris, Franklin Harris, and Hyrum Harris. This is one of four photographs taken by Anderson at the reunion. Courtesy of CHL.

Harris family reunion, 11 April 1917, photograph taken outside the Provo Sixth Ward building by George Edward Anderson, Provo, Utah. Front row: Mary Corbett, Martha Ann Harris, and William Harris Jr. Back row: Sarah Passey, Martha Startup, Zina Dennis, John Harris, Franklin Harris, and Hyrum Harris. This is one of four photographs taken by Anderson at the reunion. Courtesy of CHL.

As Martha Ann neared the end of her life, she remained close to her extended family. Her children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren recalled her uncanny ability to know when someone in her family was in trouble. “There seemed to be a thin veil between her and the Spirit World,” wrote one of her descendants. “When one of her sons was injured by a premature blast [probably while mining], his family decided to keep the news from her until he was well again, so she would not worry.” However, she wrote and asked them to tell her what the matter was because she knew something was wrong and could not rest until she knew what it was. After several similar instances, Martha Ann’s family learned to tell her immediately when anything happened to any member of her family.[63]

A Witness of the Restoration

Martha Ann often related her memories of Hyrum and Joseph the Prophet to her grandchildren and urged them to gain testimonies of the gospel’s truthfulness for themselves.[64] In one such instance, Elbert Startup (1912–99), a grandson, recorded Martha Ann’s recollection of the aftermath of the martyrdom: “I saw them bring in the bodies of Uncle Joseph, and of my father, and I remember that everyone was weeping. I remember that someone lifted me up to kiss my father’s lips for the very last time. I was only three years old, but I knew that something very important had happened that night.”[65]

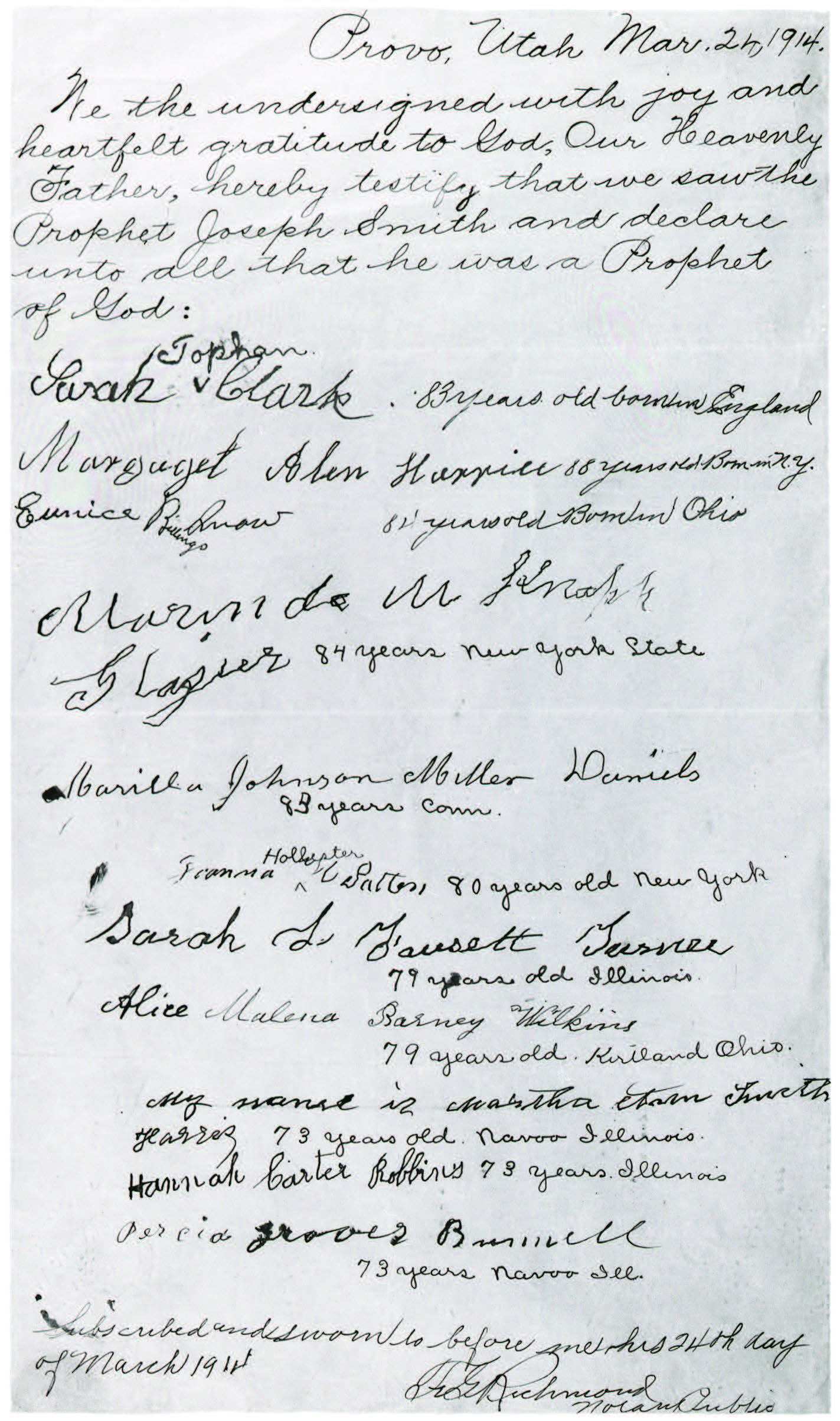

To share her testimony beyond her family circle, Martha Ann joined ten other Provo women in signing an affidavit officially witnessing that they had seen the Prophet Joseph Smith. The special occasion was captured in a photograph taken at the time.[66] The notarized document states, “Provo, Utah Mar. 24, 1914. We the undersigned with joy and heartfelt gratitude to God, Our Heavenly Father, hereby testify that we saw the Prophet Joseph Smith and declare unto all that he was a Prophet of God.” The eleven women signed their names and added their ages and birthplaces. Martha Ann was the ninth person to sign the document: “My name is Martha Ann Smith Harris, 73 years old. Nauvoo, Illinois.”[67]

Martha Ann and a group of sisters, 24 March 1914. Courtesy of the Pioneer Museum, Provo, Utah. Left to right: Margaret Allen Harris, Marinda Knapp Glazier, Martha Ann Smith Harris, Marilla Lucretia J. M. Daniels, Eunice Billings Snow, Johanna H. Patten, Alice M. B. Wilkins, Sarah L. Fausett Turner, Pericia Grover Bunnell, Hannah Carter Robbins, and Sarah Topham Clark. On the second sheet, the women have signed their names to their testimony. Martha Ann is the ninth signer: “My name is Martha Ann Smith Harris.” Someone has added “73 years old Nauvoo Illinois.”

Martha Ann and a group of sisters, 24 March 1914. Courtesy of the Pioneer Museum, Provo, Utah. Left to right: Margaret Allen Harris, Marinda Knapp Glazier, Martha Ann Smith Harris, Marilla Lucretia J. M. Daniels, Eunice Billings Snow, Johanna H. Patten, Alice M. B. Wilkins, Sarah L. Fausett Turner, Pericia Grover Bunnell, Hannah Carter Robbins, and Sarah Topham Clark. On the second sheet, the women have signed their names to their testimony. Martha Ann is the ninth signer: “My name is Martha Ann Smith Harris.” Someone has added “73 years old Nauvoo Illinois.”

Summary

Joseph F. was seventy-eight years old when he sent Martha Ann his last letter in December 1916. Four of his wives were still living, along with thirty-four children. In the end, Joseph F. was the father of forty-eight children, including two who had been adopted and three who had come into his family when he married Alice Ann Kimball. The year 1916 held special meaning for Joseph F. because he celebrated his fiftieth wedding anniversary with Julina. On 5 May that year, about two hundred fifty people joined in a celebration at the Beehive House. The following day the family gathered at the Thomas Studio in Salt Lake City for what has become a famous family photograph, with him and Julina dressed in white.

Joseph F. and Julina Lambson Smith and family, 5 May 1916, Thomas Studio. Courtesy of CHL.

Joseph F. and Julina Lambson Smith and family, 5 May 1916, Thomas Studio. Courtesy of CHL.

Later, family members gathered for “moving pictures,” which have not survived.[68] At this time Joseph F. and Martha Ann were photographed together—apparently for the last time—in at least two poses, one outdoors and one indoors.

Joseph F. and Martha Ann visiting, 5 May 1916, during the “Golden Wedding Reception given by President and Mrs. Joseph F. Smith in commemoration of their fiftieth wedding anniversary Friday evening, May the fifth from eight until eleven o’clock at the Beehive House, Salt Lake City.”[69] Courtesy of Carole Call King.

Joseph F. and Martha Ann visiting, 5 May 1916, during the “Golden Wedding Reception given by President and Mrs. Joseph F. Smith in commemoration of their fiftieth wedding anniversary Friday evening, May the fifth from eight until eleven o’clock at the Beehive House, Salt Lake City.”[69] Courtesy of Carole Call King.

Martha Ann was seventy-five years old when she received the last letter from her brother in 1916. She was the mother of eleven children, eight of whom were living in 1916. Her husband William Jasper had been dead seven years. She and Joseph F. were matriarch and patriarch over large, multigenerational families. Joseph F. wrote to her in 1916 about a family gathering where 125 members were present, including 65 of his 79 grandchildren.[70] Writing to him that same year, Martha Ann spoke of her 71 grandchildren and 34 great-grandchildren.[71]

Martha Ann enjoyed the company of family members who lived close by, giving her an opportunity to spend time with grandchildren and great-grandchildren. On one occasion in 1913, the family’s efforts to gather and celebrate Martha Ann’s birthday was mentioned in a Salt Lake City newspaper: “Mrs. Walter Startup entertained at her home Wednesday evening in honor of her mother, Mrs. Martha Harris, who had reached her seventy-second birth anniversary.”[72] At some point during the decade, the family expanded the birthday celebration into a Harris family reunion held near Martha Ann’s birthday. These reunions were generally held in the Provo Sixth Ward building (see photo on p. [to come]). As mentioned earlier, this tradition continued after Martha Ann’s death in 1923.

In these family gatherings, the stories of Martha Ann and William Jasper were retold to new generations. [73] Fortunately, Many descendants of Martha Ann who had known her firsthand shared their reminiscences of her on paper and in voice recordings. In these stories Martha Ann is described as a loving, kind, thoughtful, faithful, and hardworking mother, grandmother, and great-grandmother.

Family and health concerns are once again highlighted in the final letters between Joseph F. and his sister. Beyond the usual common maladies, they both confronted the increasing effects of aging. Joseph F. wrote with a touch of humor, “We are all usually well—but growing older at an excellerated pace, like the cart-wheel rolling down the hill, which gains speed as it nears the bottom!”[74]

Near the end of 1916, Joseph F.’s usual vigor took a permanent turn for the worse. Extracts from his journal show some of the health problems he faced near the end of his life:

I had a very painful, restless night; I could not rest.

I passed a most sleepless and uncomfortable night, with great difficulty to get full breath.

My heart was throbbing with rapid violence, and my head swam, and my eyes dimmed until I could scarcely see.[75]

From the thirty-five surviving letters from this decade, it appears that Joseph F. and Martha Ann visited each other from time to time, particularly during general conferences of the Church and family celebrations. Joseph F.’s already-rigorous schedule as a Church leader took on even more demands, a workload he maintained until health issues forced him to slow down in 1916.

Throughout this decade, Martha Ann continued to care for her children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren. As much as possible, she worked at home and continued making temple clothes. She expected to die long before her brother would,[76] but as it turned out, she lived five years beyond his death.[77]

Martha Ann always treasured her brother’s letters. On 3 March 1913 she penned these words:

I cirtenly do opricate your kindness to me poor old cripled up woman that I am I dont know what ever I would do if it was not for my dear good noble grand dear beloved generous harted even more than I could ever expect & I feel in my heart to say God bless you for ever. for you have helped me to bare my burdons helped to lighten the load that has rested on me if it had not have been for you I surly would hav sunk under the load I feel truly greatfull to you mor than I can express.[78]

The known letters between them of this final decade make few references to local and world events. The family is by far the predominant focus—a fitting finale to nearly six decades of correspondence between Joseph F. Smith and his “Dear Sister.”

Martha Artimissa Harris Startup with children, ca. 1913. Courtesy of Carole Call King. From left: Naomi, Norell, Martha Artimissa with Elbert Harris on her lap, and LaRue.

Martha Artimissa Harris Startup with children, ca. 1913. Courtesy of Carole Call King. From left: Naomi, Norell, Martha Artimissa with Elbert Harris on her lap, and LaRue.

Martha Ann and her granddaughter, Naomi Startup, ca. 1913. Courtesy of Carole Call King.

Martha Ann and her granddaughter, Naomi Startup, ca. 1913. Courtesy of Carole Call King.

Notes

[1] See Stephen C. Taysom’s forthcoming biography, “Like a Fiery Meteor”: The Life of Joseph F. Smith.

[2] “The Church in 1910,” in Mapping Mormonism: An Atlas of Latter-day Saint History, ed. Brandon S. Plewe et al. (Provo, UT: BYU Press, 2012), 132–33.

[3] See Church Membership Statistics (Provo, UT: Brigham Young University, 1973), 2.

[4] Joseph F.’s long-term impact is also seen in those he called to serve in the Quorum of the Twelve. Among them were mostly monogamist brethren, including Hyrum Mack Smith (1901), George Albert Smith (1903), David O. McKay (1906), George F. Richards (1906), Anthony W. Ivins (1907), Joseph Fielding Smith (1910), James E. Talmage (1911), Stephen L Richards (1917), and Richard L. Lyman (1918). This was an important and significant departure from the earlier practice of calling men who practiced plural marriage. Three of those called by Joseph F. became Presidents of the Church—George Albert Smith in 1945, David O. McKay in 1951, and Joseph Fielding Smith in 1970. Several of those called, including David O. McKay, Joseph Fielding Smith, Hyrum Mack Smith, and James E. Talmage, wrote important doctrinal and inspirational books. Elder John A. Widtsoe compiled Joseph F.’s sermons and writings in 1918, and the resulting book was published in early 1919 within a few months of the latter’s death. See Joseph F. Smith, Gospel Doctrine: Selections from the Sermons and Writings of Joseph F. Smith, comp. John A. Widtsoe, 5th ed. (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1939), v–vi.

[5] See W. Ray Luce, “Joseph F. Smith and the Great Mormon Building Boom,” in Joseph F. Smith: Reflections on the Man and His Times, ed. Craig K. Manscill et al. (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2013), 320–41.

[6] Quoted in James R. Clark, comp., Messages of the First Presidency (Salt Lake City, UT: Bookcraft, 1965), 4:222.

[7] See Gary L. Boatright Jr., “‘We Shall Have Temples Built’: Joseph F. Smith and a New Era of Temple Building,” in Manscill et al., Joseph F. Smith: Reflections on the Man and His Times, 303–19.

[8] See Richard Neitzel Holzapfel, “New Photographs of the Alberta Canada Temple Site Dedication, 1913,” BYU Studies 39, no. 1 (2000): 204–8. The Cardston Alberta Temple was dedicated in 1919 by Heber J. Grant.

[9] The temple in Lā‘ie was dedicated in 1923 by Heber J. Grant.

[10] See Smith, Gospel Doctrine, 650.

[11] Joseph F., journal, 20 November 1911, 19 May 1912, 17 August 1912, and 17 November 1912.

[12] Joseph F., journal, 30 May 1912.

[13] “Corner Stone Laid at B.Y.U.,” Deseret Evening News, 16 October 1909, 2.

[14] See Richard O. Cowan, “Church Programs in Transition,” in Manscill et al., Joseph F. Smith: Reflections on the Man and His Times, 418–33; and Scott C. Esplin, “Joseph F. Smith and the Shaping of the Modern Church Educational System,” in Manscill et al., Joseph F. Smith: Reflections on the Man and His Times, 401–17.

[15] For a wider view of Joseph F.’s doctrinal contributions, see Joseph Fielding McConkie, “Doctrinal Contributions of Joseph F. Smith,” in Manscill et al., Joseph F. Smith: Reflections on the Man and His Times, 17–35.

[16] “The Father and the Son: A Doctrinal Exposition by the First Presidency and the Twelve,” Improvement Era, August 1916, 934–42.

[17] See Joseph F. Smith, John R. Winder, and Anthon H. Lund, “The Origin of Man,” Improvement Era, November 1909, 75–81.

[18] Joseph F., journal, 28 May 1912.

[19] Joseph F., journal, 29 March 1913. Baptism of children in the nineteenth century took place around eight years of age. For many Latter-day Saint families this special event did not take place on a child’s eighth birthday.

[20] President Ballard’s address was recorded as 264 E. 25th Street, Portland, Oregon. President Smith and President Ballard developed a very close relationship. President Ballard began his service as mission president in 1901, the same year President Smith was sustained as Church President. President Ballard continued in that assignment until 1919, when he was called to fill the vacancy in the Quorum of the Twelve created when President Smith died. Later, in 1926, Elder Ballard’s son married Hyrum Mack Smith’s daughter, forging an even greater bond between the Ballard and Smith families.

[21] Joseph F., journal, 15 August 1912.

[22] Joseph F., journal, 18 August 1912.

[23] Joseph F., journal, 23 May 1912.

[24] John Henry Smith was Joseph F.’s second cousin. His father, George A. Smith, was Hyrum Smith’s cousin. George A. Smith’s father, John Smith, known as Uncle John, was Joseph Smith Sr.’s brother and gave Joseph F. his patriarchal blessing in 1852. At the time of John Henry Smith’s call to the First Presidency, his son George Albert Smith was also serving in the Quorum of the Twelve, the only time a father and son had served in that quorum simultaneously.

[25] “Apostle H. M. Smith, Eldest Son of President Smith of Mormon Church, Is Dead,” Ogden Standard, 24 January 1918, 2.

[26] “A. [P.] Kesler Is Killed in Fall from a Building,” Ogden Standard, 5 February 1918, 5.

[27] “Ida Bowman Smith,” Salt Lake Herald-Republican, 26 September 1918, 4.

[28] Found in Doctrine and Covenants 138.

[29] This quotation is from a letter included in this collection. See Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 26 August 1883, herein.

[30] Stephen Taysom, “Bob Dylan, Joseph F. Smith, and the Price of Revelation,” By Common Consent, 5 September 2013.

[31] See Doctrine and Covenants 138:53, 56–57.

[32] Because of the flu pandemic, no public funeral was held. However, people lined the streets to pay their respects as the solemn funeral procession made its way from the Beehive House to the Salt Lake City Cemetery. Martha Ann, along with her family, was present, as reported in a local Salt Lake City newspaper. See “Impressive Tribute Paid Church Head,” Salt Lake Tribune, 23 November 1918, 2.

[33] John Alvin Corbett to Martha Ann, 13 October 1918. Courtesy of Carole Call King.

[34] John Alvin Corbett to Martha Ann, 13 October 1918.

[35] Following John’s death in 1929, Zina Christine married Irving Llewelly Pratt in 1942.

[36] Based on conversation between Naomi Startup Biggs and Carole Call King, December 1993.

[37] Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 29 May 1911, herein.

[38] Joseph F., journal, 13 July 1912.

[39] Joseph F., journal, 14 July 1912.

[40] A few days after arriving in California, Joseph F. noted in his cash account record that he paid five dollars for a “Bathing Suit [for] Martha.” Additionally, he gave Martha Ann, Emma, Lucy, and Edith five dollars each. See Joseph F., cash accounts, 1911–12, 73–74.

[41] Joseph F., journal, 5 August 1912.

[42] Joseph F., journal, 15 August 1912.

[43] “Funeral Notice,” Provo Daily Herald, 6 February 1912, 8.

[44] Joseph F. to Joseph B. Keeler, 10 March 1912.

[45] Joseph F. reported to Irene’s husband the visit he had with Irene and her father, indicating that he had recommended an alternative but that she was determined to travel to England. See Joseph F. to Walter H. Corbett, 19 December 1911.

[46] “Memorial in Provo for Titanic Victim,” Salt Lake Tribune, 22 May 1912, 7.

[47] Irene Colvin Corbett to Martha Ann, 1 April 1912, emphasis added; as cited in Carole Call King, Verna Passey Call: Her Place in the Line of Extraordinary Women (n.p., 2018), 52.

[48] See Richard E. Bennett and Jeffrey L. Jensen, “‘Nearer, My God, to Thee’: The Sinking of the Titanic,” in Regional Studies in Latter-day Saint Church History: The British Isles, ed. Cynthia Doxey, Robert C. Freeman, Richard Neitzel Holzapfel, and Dennis A. Wright (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2007), 109–27.

[49] Joseph F. read in a local paper about a fire that damaged Martha Ann’s home; see Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 28 February 1913, herein. Martha Ann provided details in early March; see Martha Ann to Joseph F., 3 March 1913, herein.

[50] Later, on 16 October 1918, Martha Ann transferred the lot to the Church for one dollar. With the agreement, she could apparently remain in the home until her death. See Utah County Deed Record Book No. 180, entry number 5812.

[51] See Martha Ann to Joseph F., 26 December 1911; Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 22 November 1912; and Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 14 November 1916, herein.

[52] Following Martha Ann’s death in October 1923, the property was again transferred—this time to Martha Ann’s son-in-law Harry Walter Startup, who was married to Martha Artimissa Harris.

The adobe home is now gone, and the larger home, which was still standing at 214 South Third West in Provo in 2018, has been remodeled beyond recognition and is occupied by people who are not related to Martha Ann and William Jasper.

[53] Susa Young Gates, “Mothers in Israel,” Relief Society Magazine 3, no. 3 (March 1916): 122–48.

[54] Susa Young Gates to Martha Ann, 31 January 1916.

[55] See “Genealogy of William J. Harris and Martha Ann Smith,” Relief Society Magazine 3, no. 3 (March 1916): 146–48.

[56] Gates, “Mothers in Israel,” 141, 147. See page [to come] herein.

[57] Gates, “Mothers in Israel,” 140–41.

[58] Joseph F. to Ina D. Coolbrith, 23 October 1911.

[59] See Martha Ann to Joseph F., 7 July 1914, herein.

[60] See Carole Call King, “History of Martha Ann Smith Harris, 1841–1923” (unpublished manuscript in editors’ possession).

[61] Ruth Mae Harris, Martha Ann, Daughter of Hyrum and Mary Fielding Smith (Orem, UT: published by the author, 2002), 147.

[62] Harris, Martha Ann, 148.

[63] Harris, Martha Ann, 131.

[64] In one case, Martha Ann wrote a letter to Tennessee to witness the truth of the Restoration. See Martha Ann to Joanna Spears, 1920.

[65] Harris, Martha Ann, 131.

[66] The photograph and affidavit are displayed at the Provo Daughters of Utah Pioneers Museum in Provo, Utah. See Katherine Thatcher Brimhall, The Testifiers of the Prophet Joseph Smith: Biographical Vignettes of Mormon Pioneer Women (n.p., 2011).

[67] “March 24, 1914 Affidavit,” Provo Daughters of Utah Pioneers Museum, Provo, UT.

[68] Joseph F., journal, 5–6 May 1916.

[69] Invitation, “1866–1916,” Golden Wedding Reception, Joseph Smith Family Papers, CHL.

[70] See Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 14 November 1916, herein.

[71] See Martha Ann to Joseph F., 27 March 1916, herein.

[72] “Social Events in Utah,” Salt Lake Herald, 18 May 1913, 40.

[73] In 1935 a gathering that included swimming, games, singing, eating, and a special visit from Martha Ann’s sister-in-law Julina Lambson Smith took place with more than one hundred family members present. A Provo newspaper reported, “Remarks were then made by Mrs. Julina L. Smith, of Salt Lake, the eldest surviving wife of the [Church] president Joseph F. Smith. She gave a splendid talk on her acquaintances with and her love of Martha Ann and William [Jasper] Harris.” “Harris Family Reunion at Saratoga,” Daily Herald, 17 June 1935, 2. Her visit was timely since Julina died less than seven months later on 10 January 1936.

[74] See Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 30 September 1916, herein.

[75] Quoted in Joseph Fielding Smith, The Life of Joseph F. Smith: Sixth President of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1938), 472.

[76] See introduction to the 1880–89 letters.

[77] Martha Ann passed away in Provo on 19 October 1923 at the age of eighty-one.

[78] See Martha Ann to Joseph F., 3 March 1913, herein.