Decade Introduction

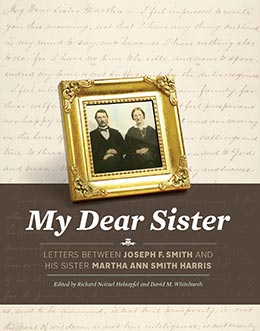

Richard Neitzel Holzapfel and David M. Whitchurch, "Decade Introduction," in My Dear Sister: Letters Between Joseph F. Smith and His Sister Martha Ann Smith Harris, ed. Richard Neitzel Holzapfel and David M. Whitchurch (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2019), 387–404.

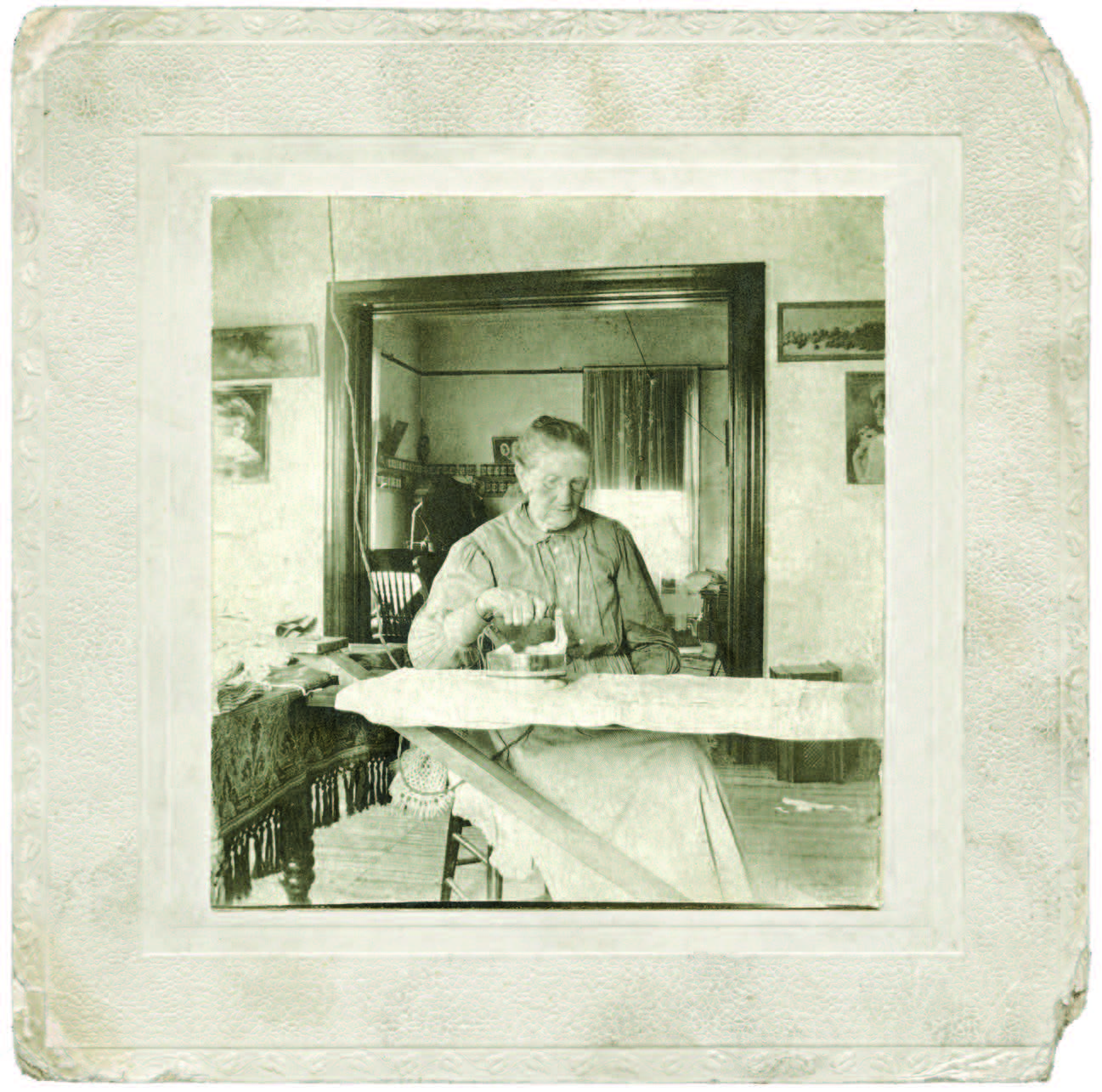

Martha Ann Smith Harris, 14 May 1901, photograph by Adam Anderson, Provo, Utah. Courtesy of CHL.

Martha Ann Smith Harris, 14 May 1901, photograph by Adam Anderson, Provo, Utah. Courtesy of CHL.

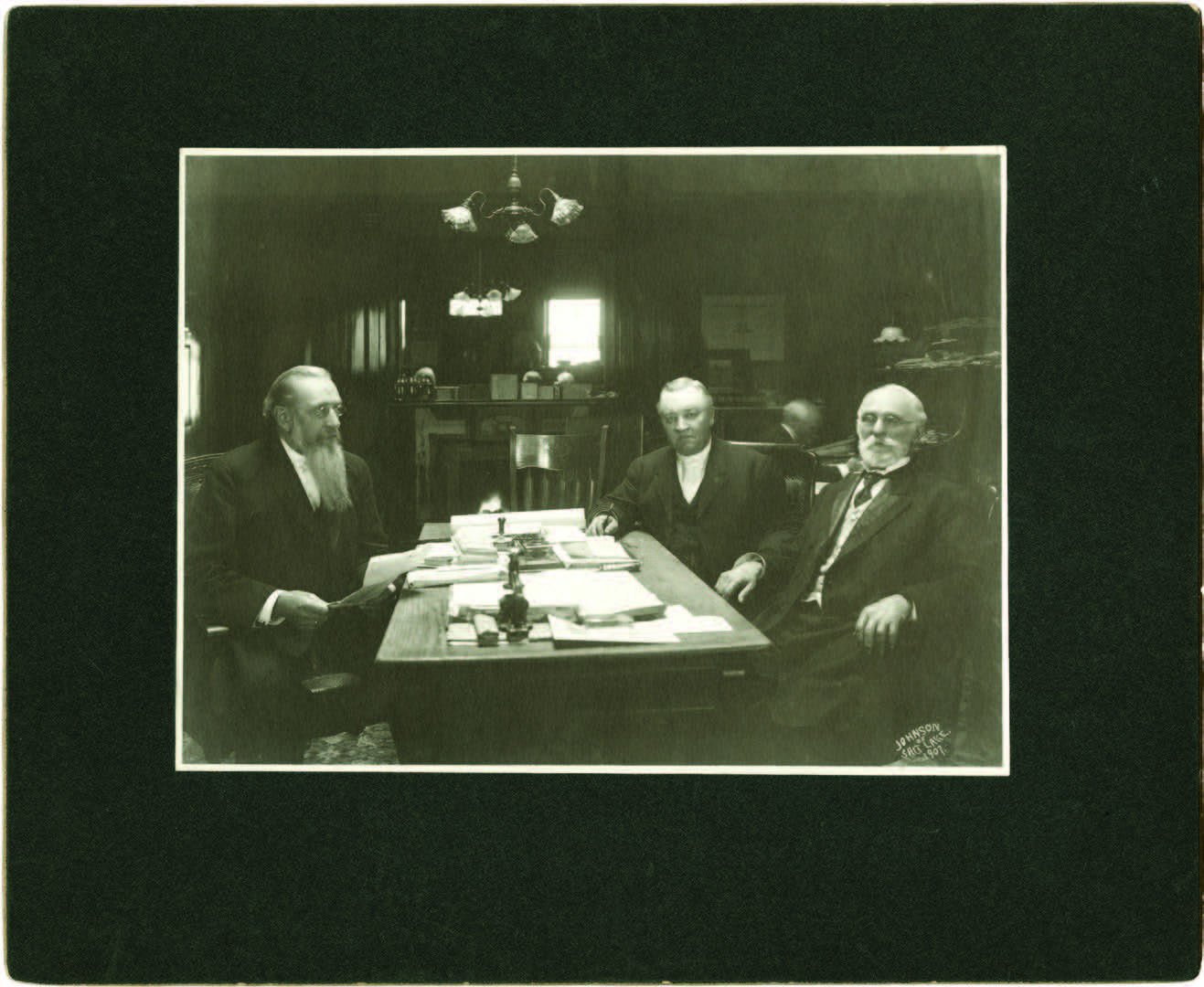

As the twentieth century dawned, the Church witnessed changes in leadership that would influence its course for years to come. When George Q. Cannon died on 12 April 1901, Joseph F. was called by President Lorenzo Snow to be the First Counselor in the First Presidency. Joseph F. served in this capacity until the death of President Lorenzo Snow later that year. He was then sustained as the sixth President of the Church during the general conference in November 1901.[1] President Joseph F. Smith chose as counselors a native of England, John R. Winder (1821–1910), and a native of Denmark, Anthon H. Lund (1844–1921). A hallmark of his presidency was that he raised the status of his counselors to near equals with him in decision making. President Smith mentions the importance of this relationship in several sermons.[2]

The First Presidency, 19 November 1907, photograph by Charles E. Johnson, Salt Lake City, Utah. From left to right: Joseph F. Smith, Anthon H. Lund, and John R. Winder. One of the secretaries in the office of the First Presidency is seated behind the group. Note the large stack of correspondence on the desk near President Smith’s left hand. In most cases he dealt with official Church correspondence during the day and personal correspondence after work until late. Courtesy of CHL.

The First Presidency, 19 November 1907, photograph by Charles E. Johnson, Salt Lake City, Utah. From left to right: Joseph F. Smith, Anthon H. Lund, and John R. Winder. One of the secretaries in the office of the First Presidency is seated behind the group. Note the large stack of correspondence on the desk near President Smith’s left hand. In most cases he dealt with official Church correspondence during the day and personal correspondence after work until late. Courtesy of CHL.

In his new role, President Smith worked energetically to improve the Latter-day Saints’ image, retire the Church’s debt, meet the needs of a growing international membership, and preserve the early history of the Restoration with the purchase of historical sites associated with the founding events of the Church.[3]

During this time of increased responsibilities, President Smith was often weighed down by a desire to accomplish more despite his continual strenuous efforts. In a letter to Martha Ann’s daughter and son-in-law, Naomi and Walter Startup, he noted, “I need more time, more endurance, more ability and more help to meet all my obligations, and to perform more promptly my duties.”[4]

The Latter-day Saints’ Public Image

The number of new plural marriage sealings being performed began to drop rapidly in 1889. This trajectory continued following the decision by Church President Wilford Woodruff (1807–1898) to publicly issue a statement, known as the 1890 Manifesto, that the Church would comply with United States law.

However, the scope and interpretation of the Manifesto was not universally agreed upon by Church leaders and members. Many believed new plural marriages could be performed in Mexico and Canada without violating the intent of the 1890 Manifesto. The question of continuing cohabitation by those who had entered into the practice before 1890 was not addressed in an authoritative manner at this time. As a result, some men with plural families chose to live monogamously, while others chose to continue to support and live with their plural families. Nevertheless, the 1890 Manifesto represented a significant shift in Church teachings regarding plural marriage and began the process of ending new plural marriage sealings in the Church.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, the American public demanded clarification of the issues surrounding alleged new plural marriages being performed by Church authorities and continuing cohabitation by its members. When Apostle Reed Smoot (1862–1941)[5] was elected to the United States Senate as one of Utah’s two senators in 1902, these issues came to a head.

By the time Smoot arrived in Washington, DC, on 20 January 1903, a group of Utah citizens had written a letter to the president of the United States protesting Smoot’s seating as a senator by virtue of his conflict of interest as a Latter-day Saint Apostle and his views on plural marriage.[6] They also believed Smoot’s allegiance to his church would supersede his allegiance to the country. [7]

In response, the Senate organized a series of hearings to determine the propriety of the appointment. Among many other witnesses, President Smith was subpoenaed as one of the chief witnesses, becoming the first President of the Church to appear before a Senate committee hearing.[8] During the ensuing months, President Smith testified before Congress about the Church’s doctrines and practices. He was asked probing questions regarding not only Smoot’s appointment to Congress but also details about his own personal life, including his continued cohabitation with his plural wives after the 1890 announcement of the Manifesto.

Though the hearings purportedly concerned the seating of Senator-Elect Smoot, it became clear that the Church was on trial not only in the US Congress but also in the press.[9] Never before had the Church been so thoroughly investigated by an official federal government body and criticized and lampooned in public lectures, newspaper articles, editorials, and political cartoons.[10] It was a particularly challenging time for the Church. President Smith personally felt humiliated by the experience.[11]

In Washington, President Smith promised the committee that he would clarify the Church’s position on new plural marriage sealings, including those performed in Mexico and Canada. As a result, he issued another official statement on plural marriage at the Church’s general conference in the fall of 1904. The statement, known as the Second Manifesto, broadened the scope of the 1890 Manifesto throughout the world, including in Canada and Mexico, and is considered a watershed event in Church history.

President Francis M. Lyman (1840–1916), President of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles at the time, explained, “When [the 1890 Manifesto] was given, it simply gave notice to the Saints that they need not enter plural marriage any longer, but the action taken at the conference held in Salt Lake City on the 6th day of April 1904 [the Second Manifesto] made that manifesto prohibitory.”[12] The First Presidency directed President Lyman to send letters to each member of the Quorum of the Twelve informing them that they planned to “strictly enforce” the intent and scope of the Second Manifesto as they had outlined.[13]

Despite this effort to end new plural marriage sealings, some leaders at the local, stake, and general level continued to authorize new plural marriage sealings after 1904. By October 1905, two Church Apostles, John W. Taylor[14] and Matthias F. Cowley,[15] resigned from the Quorum of the Twelve because of their continued opposition to the Second Manifesto.[16] Taylor and Cowley continued to be “out of harmony” with Church leaders following being dropped from the Quorum of the Twelve and were eventually disciplined for performing unauthorized new plural marriage sealings outside the temple.[17]

In the end, the Church had turned a corner regarding its efforts to end new plural marriage sealings, and Senator Smoot was able to retain his seat.[18] Finally, despite the embarrassment of the lengthy Smoot hearings and the painful resignations of two Apostles, this period of Church history provided the Saints an opportunity to tell its own story.[19]

The Church’s Debt

Though Lorenzo Snow made significant progress in retiring the Church’s massive debt before his death in 1901, President Smith continued to address this pressing need once he became Church President.[20] As President Snow before him, Joseph F. continued to stress the sacred opportunity and blessing every member had to pay tithes and offerings. He taught the promised blessings that would come from doing so. As a result of increased donations to the Church and careful debt management, President Smith could make a triumphant announcement at the 1907 April general conference: “Today the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints owes not a dollar that it cannot pay at once. At last we are in a position to pay as we go. We do not have to borrow any more, and we won’t have to if the Latter-day Saints continue to live their religion and observe the law of tithing.”[21]

A Worldwide Church

For some time, the Church had asked members to remain where they lived, instead of emigrating to the Latter-day Saint core area as had been the practice since 1831. During President Smith’s administration, the Church increased efforts to expand beyond the traditional borders of the Intermountain West by building chapels in areas where the Church hoped to grow and stay.

To emphasize his vision of an international Church, President Smith and his wife Edna (1851–1926) departed Salt Lake City on a trip to Europe to strengthen and encourage the Saints living there. As a result, he became the first Church President to visit members outside the United States.[22] During his trip, he visited Belgium, England, France, Holland, Germany, and Switzerland, where he attended various conferences and instructed the Saints and missionaries before returning home to prepare for general conference in October.

Joseph F. Smith and party at British Mission home, 1906. Courtesy of CHL. A group portrait of Joseph F. Smith, his wife Edna, and four of his sons, along with Charles W. Nibley and two of his daughters and Heber J. Grant, his wife Emily, and two of his daughters.

Joseph F. Smith and party at British Mission home, 1906. Courtesy of CHL. A group portrait of Joseph F. Smith, his wife Edna, and four of his sons, along with Charles W. Nibley and two of his daughters and Heber J. Grant, his wife Emily, and two of his daughters.

A few years later, in the early spring of 1909, President Smith returned to the Hawaiian Islands with his wife Julina Lambson (1849–1936) and several family members. Again, this was a historic trip because no Church President had yet traveled to Hawai‘i to minister to the people.[23] President Smith received a warm welcome from the Saints and missionaries. He thanked them for their dedication and sacrifices over and over again. It was a tender time for him, as he reflected on his ministry among the people he loved there, beginning in 1854. As President Smith and his party departed for home in late March, he noted that they were met at the wharf by “many of the good Hawaiian Sisters who fairly Smothered us with flowers and leis of a great variety.”[24]

Church History

As he looked toward the future, President Smith also made efforts to remember the past. During his administration, the Church began to buy sites associated with its beginnings.[25] In 1903 President Smith authorized the purchase of Carthage Jail, where his father, Hyrum, and uncle Joseph were martyred in 1844. This was followed by the purchase of the Vermont farm where Joseph Smith had been born in 1805. Shortly thereafter, the Church placed a 38½-foot[26] granite obelisk shaft there to commemorate the Prophet’s birth. President Smith, along with family members and Church leaders, attended the monument’s unveiling on 23 December 1905, exactly one hundred years after Joseph Smith’s birth. Before returning to Salt Lake City, the party toured many Church historical sites in New York and Ohio.

Family Life

Joseph F.’s large family remained the center of his life. He rejoiced at the birth of four children and many grandchildren during this decade. He also experienced heartbreak when family members, including his own children, died. In early 1901, Joseph F.’s daughter Alice Smith (1884–1901) passed away at the age of eighteen. A local Salt Lake paper reported, “The parents and friends have stood by her for a year and helplessly watched her life gradually ebb away. . . . There was nothing that love or skill could suggest that was not done, but the bloom faded from her beautiful cheeks and the silent working of the disease went on without abatement.”[27]

During the sickness, Joseph F. kept Martha Ann updated on Alice’s condition: “I am happy to say that we are all better with the exception of Aunt Sarah’s Alice, who is still quite poorly.”[28] The newspaper noted that she had returned home from school a year earlier, but “she failed gradually from then on. The affliction was so deeply rooted that nothing seemed to be able to control it. So that the pall of her impending fate has been hanging over the home on Second West street for several weeks.” The news report concluded, “This morning, at 10:30, surrounded by her father and mother, and other members of the family, her sweet soul was released, and nothing was left but the wasted form and sorrowing hearts.”[29]

Home of Joseph F. and Sara Ellen Richards Smith, 25 September 1906, Shipler Photographers. Courtesy of USHS. Alice Smith returned home from school in 1900 to convalesce but died here in April 1901.

Home of Joseph F. and Sara Ellen Richards Smith, 25 September 1906, Shipler Photographers. Courtesy of USHS. Alice Smith returned home from school in 1900 to convalesce but died here in April 1901.

Joseph F. also supported his sister Martha Ann in her times of trouble and loss. A year following his daughter’s death, Joseph F. took an opportunity to write a letter to his wife Edna Lambson to update her on family matters: “I got a letter this morning from Aunt Martha telling how little Mary Corbett was suffering, and while I was reading it, I got a message thru the phone that she passed away last night or this morning at about 1 o’clock.”[30]

A local Salt Lake City newspaper reported: “Provo July 26 Mamie Corbett, the 11 year old daughter of Mr. and Mrs. W S Corbett, died last night, after several weeks of severe illness, commencing with periostitis, caused by taking cold, and for which an operation was performed. This was followed by pleurisy pneumonia, and finally meningitis, which was the immediate cause of the child’s death.”[31]

Joseph F. wrote a short letter to Josephine Harris, Martha Ann’s daughter-in-law, and mentioned he had attended the funeral. “My Dear Niece: I got your letter of 25th on the 26th but I have been so driven with crowding duties that I could not get to your affairs. I was at Provo on Monday attending the funeral of little Mary Corbett.”[32]

Each death brought great sorrow to Joseph F. In a tender letter to Martha Ann on 22 November 1905, he recorded his feelings at the loss of his six-month-old grandson Alfred William Peterson Jr. (1905): “Yesterday morning at about 2 o’clock My precious Mamies Sweet little boy[33] passed into the great beyond from whence he so recently came. He was a most inteligant, attractive, beautiful little man. . . . We are all broken up. To my beloved and noble Mammie death could not have come in a more cruel way. He was her very hope, joy and life!”[34]

Writing and receiving letters continued to be an important means for Joseph F. to keep in touch with family members even though it was challenging to do so. For example, he noted in a letter to his wife Sarah Kimball, “This is Sunday night. I am a little tired. I have been at work all day with my accounts, which have been neglected of late, having been so much away from home, and so busy when at home, that I let my own affairs go behind. And then have, with Joseph’s help, got a lot of correspondences off my hands, today. Thus I have been busy all day. My eyes begin to ache, and my head swim, so I must stop pretty soon, I also prepared an article for the Era today, so you may guess I have not been idle.”[35]

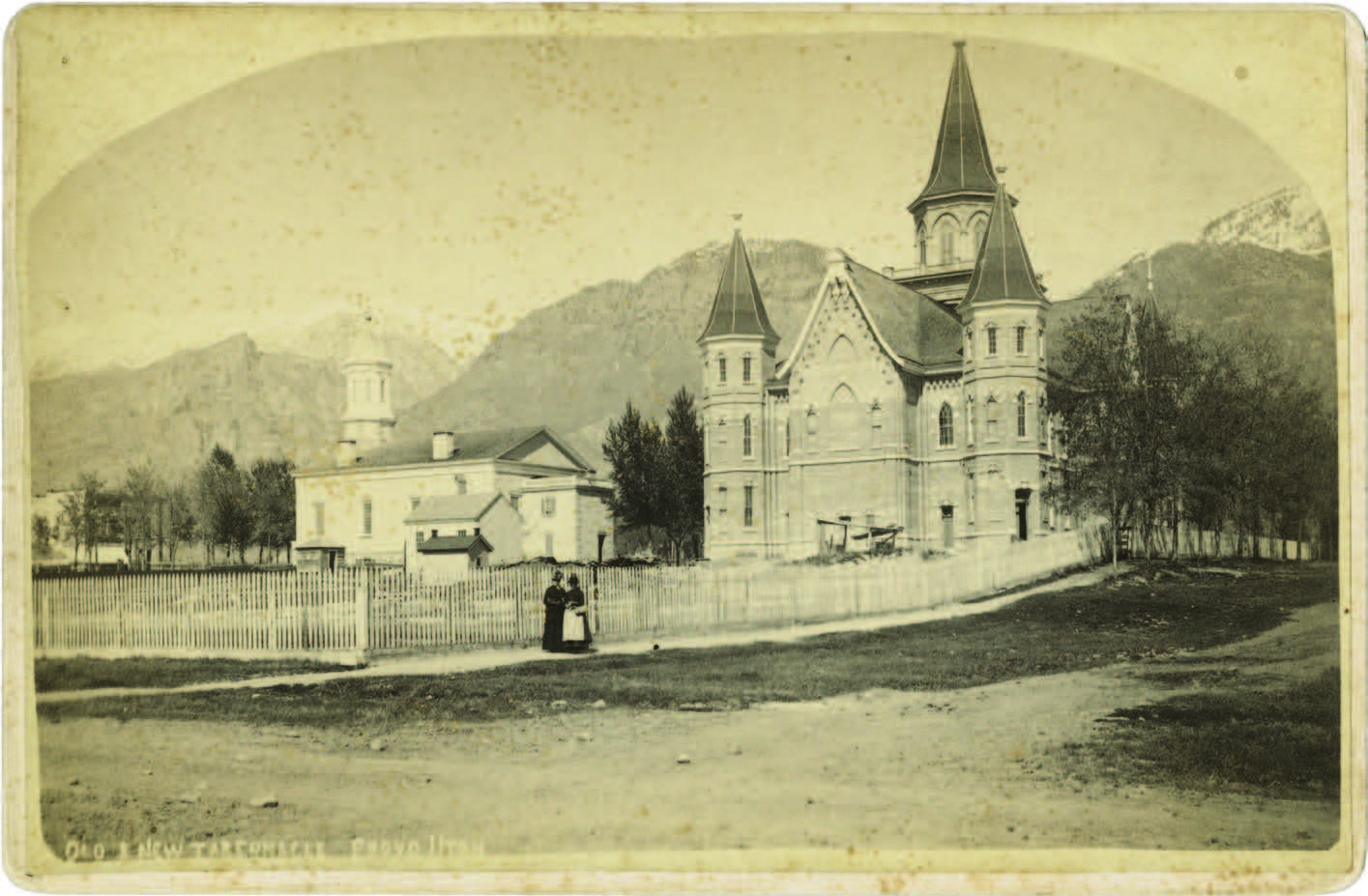

Old and New Provo Tabernacles, ca. 1886, photography by F. I. Monsen and Company, Salt Lake City, Utah. View looking east showing side and rear of old tabernacle (1861–1919) and back of new tabernacle (1898–2010).

Old and New Provo Tabernacles, ca. 1886, photography by F. I. Monsen and Company, Salt Lake City, Utah. View looking east showing side and rear of old tabernacle (1861–1919) and back of new tabernacle (1898–2010).

Construction of the new tabernacle, known as the Provo Stake Tabernacle, began in 1883. The April 1886 general conference of the Church was held in the new tabernacle. However, it was not dedicated until 1898. Joseph F.

Smith participated in various meetings in both buildings during his ministry. Martha Ann also attended meetings in these historic buildings, and in 1923 friends and family gathered in the Provo Stake Tabernacle to honor

Martha Ann during her funeral services. Courtesy of CHL.

By 1900 Joseph F. had started to use his children to help him with his correspondence. In some cases, they were learning how to help him. After a letter had been typed with multiple corrections, Joseph F. would pick up a pen and add a note to the letter, “P.S. I dictated the foregoing to one of my boys who is just learning to typewrite, therefore you will kindly excuse its in-artistic appearance.”[36]

His letterpress copybooks during this period are filled with letters to his missionary children. As noted earlier, between 1895 and 1914, Joseph F. sent twelve sons on missions.[37]

In addition to the letters between Joseph F. and his missionary sons, his letters to Martha Ann provide important information about his life and ministry during this period. Additionally, they are one of the few primary sources to help reconstruct Martha Ann’s world during this decade.

Martha Ann Smith Harris

Joseph F. and Martha Ann continued to face the deaths of loved ones during this period. Martha Ann’s thirteen-month-old granddaughter, Lucy Jane Corbett, was tragically killed by a train on 21 March 1901.[38]

It is hard to imagine how Martha Ann’s daughter Mary Emily Harris (1865–1947) and her husband, Walter Sutton Corbett (1857–1912), felt as they lost two children within such a short time. That Joseph F. and Martha Ann also felt deeply about these deaths is manifested in the letters written during this period.

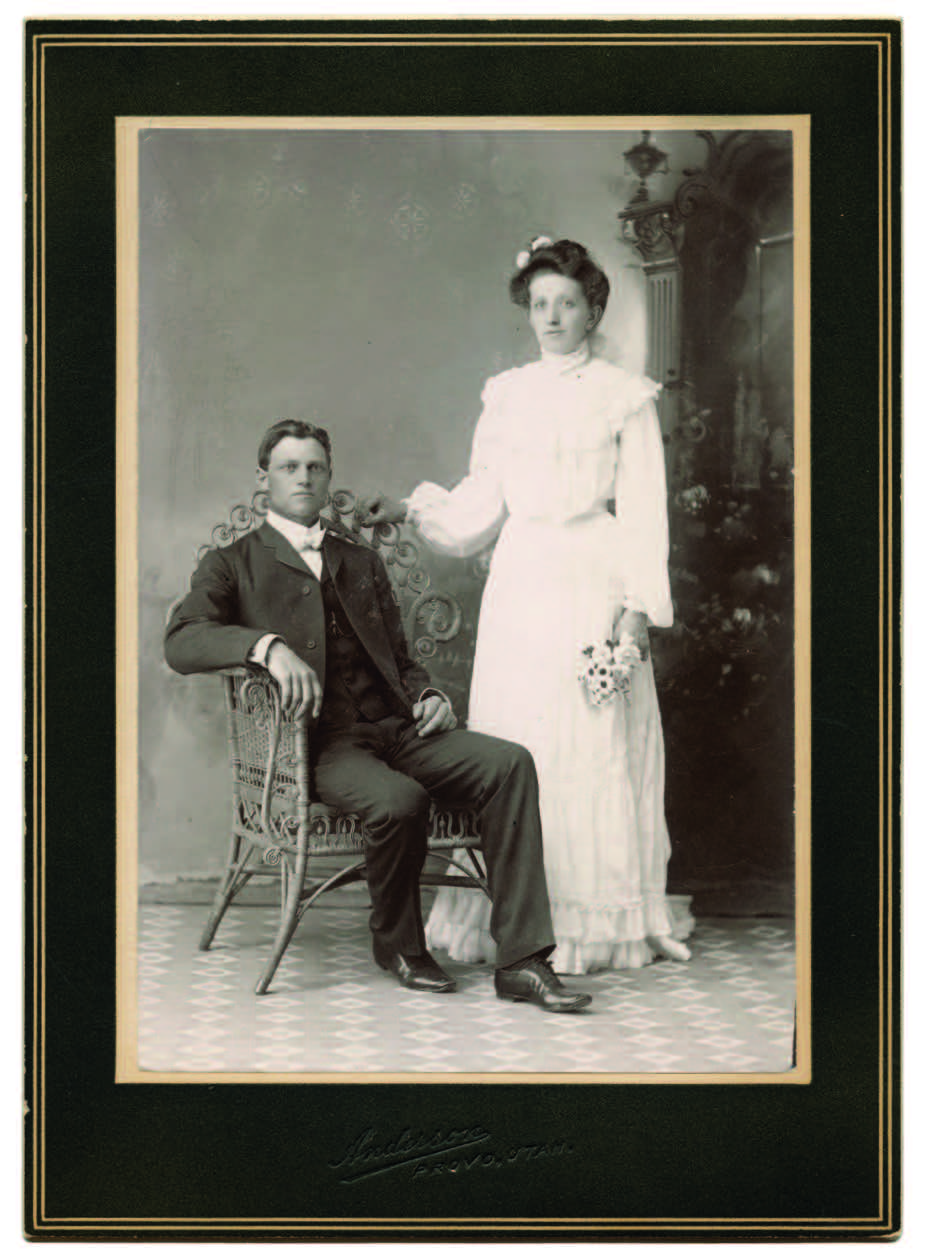

The natural rhythms of life continued to flow through Martha Ann’s family. For example, nearly a year later, Martha Ann and William celebrated a daughter’s wedding when Mercy Ann Harris (1874–1905) married John Thomas Dennis (1866–1929) in June 1903. Again, Martha Ann’s brother Joseph F. was able to perform the marriage sealing in the Salt Lake Temple.[39] To have the President of the Church participate was certainly appreciated, but the fact that he was her brother made the wedding ceremony even more meaningful for Martha Ann and her family.

John and Mercy Ann Harris Dennis on their wedding day, 25 June 1903, photograph by Anderson, Provo, Utah. Courtesy of Carole Call King.

John and Mercy Ann Harris Dennis on their wedding day, 25 June 1903, photograph by Anderson, Provo, Utah. Courtesy of Carole Call King.

One month after celebrating this special occasion, Martha Ann and William Jasper’s daughter, Lucy Smith Harris Simmons (1870–1903), died from complications during delivery on 26 July 1903. Her baby, Lucy, also died at the same time. Martha Ann chose to raise Lucy’s two young children, Edna Mae (1899–1986) and John Arthur (1900–1961). Joseph F. was worried about that decision, and in a letter dated 10 April 1907 he wrote, “I have been thinking about you and Dear Lucy’s children. I feel it is too much for you to try to take care of them alone. And Even if you could and did succeed in doing so for a while, the moment you cannot do it any longer the children would have to do without you—or without your help.”[40]

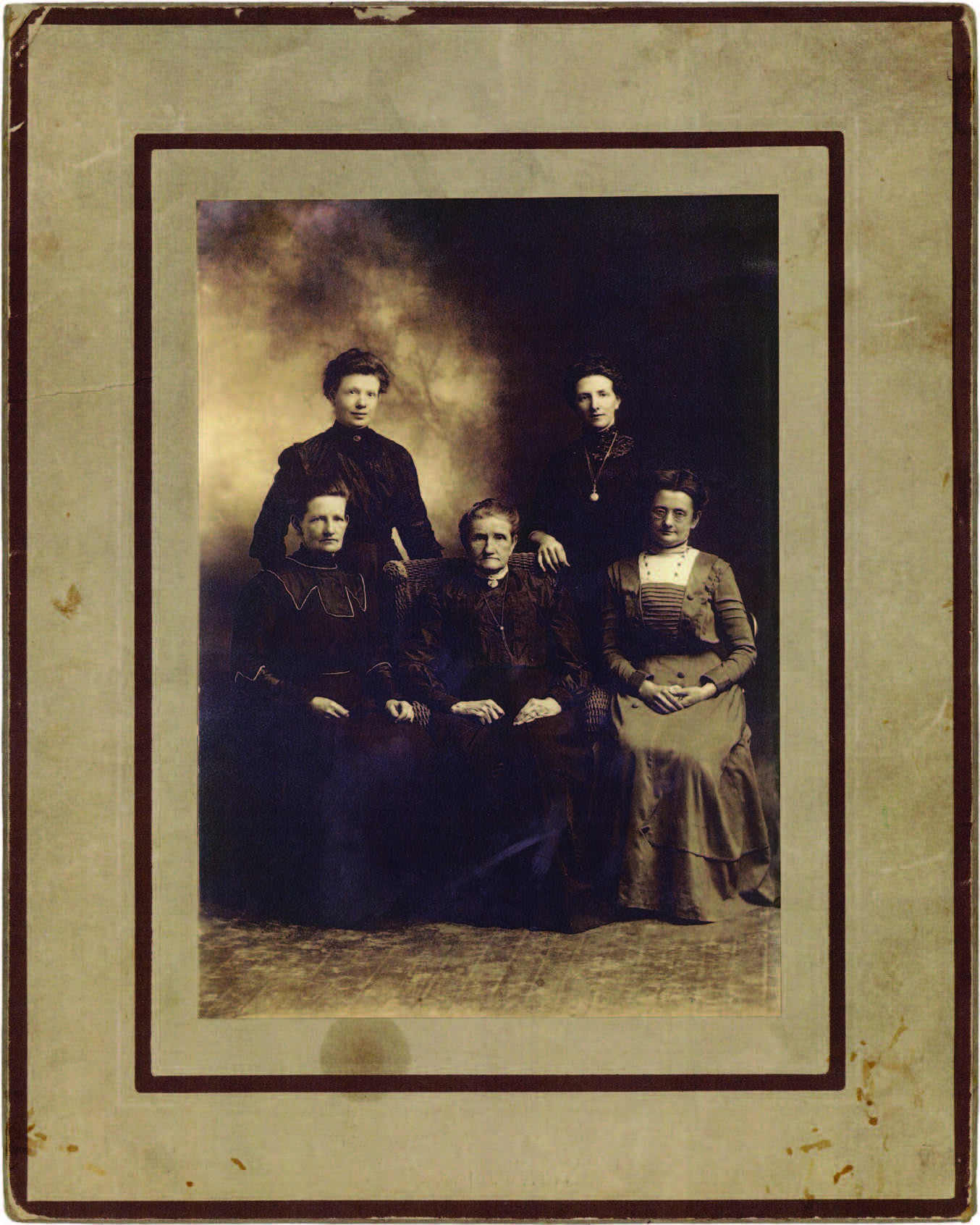

Martha Ann and her daughters sometime after the death of Lucy Smith Harris Simmons in 1903 and before the death of Mercy Ann Dennis in 1905.

Martha Ann and her daughters sometime after the death of Lucy Smith Harris Simmons in 1903 and before the death of Mercy Ann Dennis in 1905.

Joseph F. reached out to his nephew Hyrum Smith Harris and his wife Delia Twede Harris to encourage them to adopt the children.[41] At the time, Hyrum and Delia had no children since their only child, Mercy Rachel Harris, had died within a few months of her birth in 1891. In the end, Martha Ann decided to raise these two grandchildren as her own children, despite her brother’s counsel. Later, still childless, Hyrum and Delia adopted a daughter, Julina Harris, who was born on 3 July 1909.

Delia Twede Harris and her adopted daughter, Julina Harris, ca. 1913. Courtesy of Carole Call King.

Delia Twede Harris and her adopted daughter, Julina Harris, ca. 1913. Courtesy of Carole Call King.

Martha Ann’s decision to ignore Joseph F.’s counsel is surprising given that Joseph F. was rather adamant that she not take on such a heavy responsibility. In a letter written in April he wrote, “I have been think about you and Dear Lucy’s children. I feel it is too much for you to try to take care of them alone. And Even if you could and did succeed in doing so for a while, the moment you cannot do it any longer the children would have to do without you or without your help.”[42]

Martha Ann’s reason for disregarding her brother’s advice is made apparent only after Ina Coolbrith writes about Martha Ann raising her grandchildren in two letters to Joseph F. in 1912 and 1913. Ina seemed not to grasp how or why Martha Ann took upon herself such a significant responsibility, especially given the health challenges she faced at the time. In response to Ina’s comments to Joseph F., Martha Ann revealed why she ignored his counsel:

Pleas give my love to cousin Ina & I know she will not under stand how I can take care of these children [Edna Mae Simmons and John Arthur Simmons]. I can do it becaus I loved thir mother [Lucy Smith Harris Simmon] mother she was true & faithfull to me. & the Sunday before she died she said to me if <I> knew my children would be taken care of as good as little Sarah is being taken care of. I could die contented I told her if any thing ever hapened too her I would just as good care of them & I did of her that is Zinas little girl that I raised on a bottle. that is I said if I am alive I have tryed to do it the best I could. but I little thought that in one week they they would be in my care.[43]

Mercy Ann Dennis lost her first child, George A. Dennis, on the day of his birth in 1904. The next year was even more tragic for Martha Ann’s family when Mercy Ann gave birth to another stillborn child, Marguerite, on 9 January 1905.[44] Little Marguerite was buried on 11 January. Twelve days later, on 23 January 1905, Mercy Ann died too, at the age of thirty. Martha Ann had taken care of her at the Harris home in Provo during this difficult time. Zina, Martha Ann’s daughter who had lost a child in 1899 and her own husband in 1903, wrote the following:

To Mother on the death of her girls, Mercy & Lucy:

Break the news gently to Mother dear heart, tell her oh gently

That she is now called with a dear living daughters to past

Speak gently words to her pray for her too

Show her the tranquil sweet peace she has gained

And the rest, oh so blissful, now spirit so free.[45]

Funerals brought the family together as they gathered to mourn and support one another. For example, when Hellen Fisher Smith, the wife of Martha’s older half brother John Smith, died in September 1907, Martha Ann made her way to Salt Lake City to help Joseph F.’s wives make burial clothes; she also attended the funeral.[46]

Despite such hard times, Martha Ann celebrated the births of grandchildren and enjoyed being a grandmother, as when her son Franklin Hill Harris and his wife, Josephine P. Robinson (1868–1965), had their first child, Franklin Hyrum (1898–1971). This couple added four more children to their family in the first decade of the twentieth century: Richard Parkes (1900–1976), Mary Harris (1903–91), Carl Joseph (1906–87), and Leonora Harris (1909–76). For Martha Ann, these were joyous blessings straight from heaven.

Frank and Josephine Harris family, October 1906, Olson & Hafen, Provo, Utah. Courtesy of CHL. Franklin Hyrum, Carl Joseph, Josephine Robinson, Richard Parkes, Franklin “Frank” Hill, and Mary Harris.

Frank and Josephine Harris family, October 1906, Olson & Hafen, Provo, Utah. Courtesy of CHL. Franklin Hyrum, Carl Joseph, Josephine Robinson, Richard Parkes, Franklin “Frank” Hill, and Mary Harris.

Economic Challenges

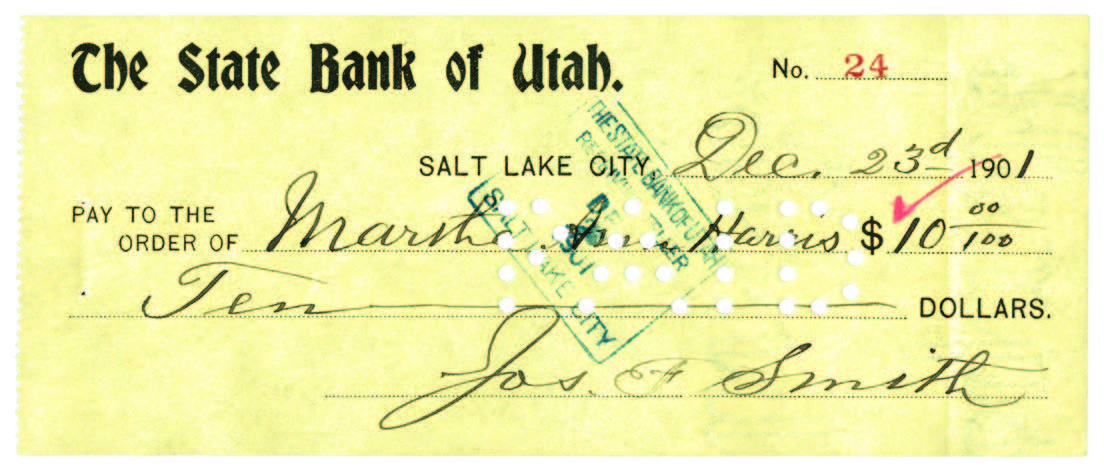

Although Martha Ann was the major contributor to the family economy for some time as the decade began, she continued to struggle financially for the remainder of her life. As their letters so often demonstrate, Joseph F. helped his sister whenever he could. For example, in December 1901 he wrote, “I send you here with my check No. 24. for ten dollars, which please accept as a small token of remembrance for your Christmas dinner.”[47]

Joseph F. Smith’s check, drawn on an account with the State Bank of Utah, dated 23 December 1901. Courtesy of CHL. Martha Ann countersigned the back of the check to cash it.

Joseph F. Smith’s check, drawn on an account with the State Bank of Utah, dated 23 December 1901. Courtesy of CHL. Martha Ann countersigned the back of the check to cash it.

In June 1904 Joseph F. offered to replace the home’s roof and make needed repairs. He recorded the work done in an account book: “June 1 to 30. Paid E. D. Partridge for shingling and repairing my sister, Martha Ann. Harris’ house.”[48] In December that year, Joseph F. sent her a check for ten dollars to cover a Christmas meal. During the next month, he handed her cash on two separate occasions. In February 1906 he presented her with a gift of “dress goods, Sheeting, etc.” costing fifteen dollars. During the decade, Joseph F.’s account books reveal numerous gifts in addition to cash, including shoes, linen, dress patterns, slippers, pillows, tablecloths, and a subscription to the Deseret Semi-Weekly News.[49]

William Harris’s Death

As the decade ended, Martha Ann experienced another heartbreak when her beloved husband, William Jasper Harris, was killed in an accident in 1909. He and his son John Albert (1872–1946) attended a Black Hawk War veterans’ celebration at the Opera House on Center Street in Provo on Friday, 23 April 1909.[50] As they crossed the street while walking home after the event, an out-of-control horse and buggy driven by a family friend struck William. He suffered severe injuries to the head and died in his home early the next morning.[51] Martha Ann and William had celebrated their fifty-second wedding anniversary just three days before the accident.

To his son Franklin Richards Smith (1888–1967), who was serving a mission in the British Isles at the time, Joseph F. wrote, “This morning Uncle William Harris died, from being knocked down and run over by a team and wagon late last night. The time for the funeral has not yet been set.”[52] The funeral was held on 29 April.[53] Joseph F. attended the funeral, as noted in a letter written late that evening: “It is now 8 p.m., I have just come into the office from attending the funeral of Wm. J. Harris, my sister’s husband, at Provo.” Apostles Orson F. Whitney (1855–1931) and Francis M. Lyman (1840–1916) had delivered the eulogies.[54]

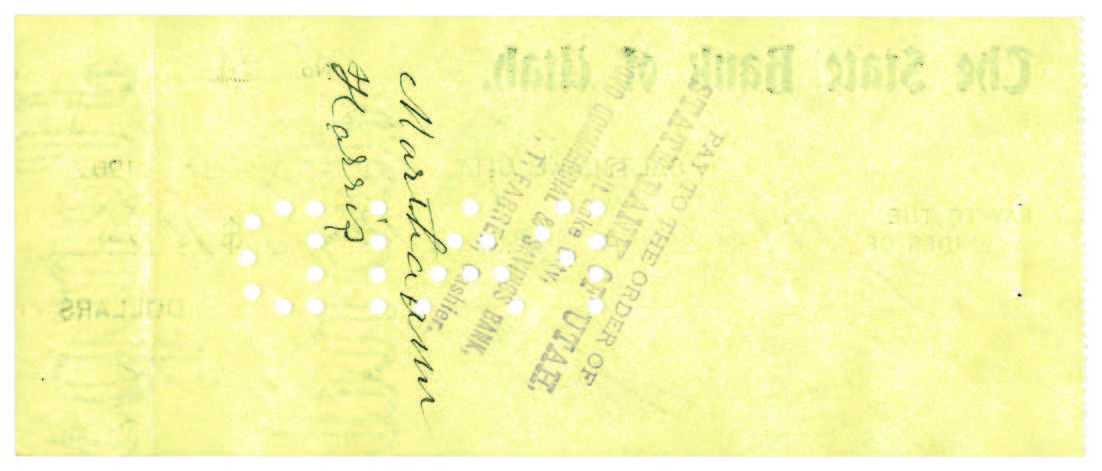

Martha Ann ironing at home in Provo, Utah, ca. 1909. Courtesy of Carole Call King.

Martha Ann ironing at home in Provo, Utah, ca. 1909. Courtesy of Carole Call King.

A few days later, Joseph F. wrote his sister, “I spoke to Frank when he was here about it, and I told him I would help him out on the Expenses of the Undertaker. I will enclose in this letter a note for you to hand or send to mr. Edward L. Jones, the Undertaker, as I do not know his address. All you need to do will be to send it to him by one of the Children, or any person who can deliver it to him.”[55] In that note, Joseph F. asked the undertaker to “kindly send” him a status on the funeral expenses, as he wanted to help pay for the “burial of Wm. J. Harris.”[56]

Martha Ann made her way north to Salt Lake City to stay with her brother during this time of mourning. On 4 July 1909, Joseph F. wrote his nephew Hyrum S. Harris, “Your mother is here. Adelia’s little baby girl, as pretty as a picture, was born yesterday (July 3r). Your mother starts for Provo with ‘it’ in a few minutes by the San Pedro Rwy. You should come at once to Provo, or send Adelia to take care of her baby. Your mother is as pleased she would be with one of her own. She acts just like a young mother. We all feel sure that Adelia will be proud of it too, and if she doesn’t come quickly for it, I fear Aunt Martha will not want to give it up. Now you see the situation and you will govern yourself accordingly. We all send love and congratulations for the baby and best wishes for Adelia. Affectionally, your Uncle Joseph F.”[57]

Mary and Donette Smith, ca. 1900, photograph by Charles W. Symons, Fox & Symons, Salt Lake City, Utah. Courtesy of CHL. The photograph was colorized by the photographer in the studio in an effort to capture the natural colors of clothing, eyes, and hair. As Joseph F.’s family grew, more and more photographs were being taken at studios in Salt Lake City in an effort to document his personal family life and to share that life with his friends and family, including Martha Ann. See, for example, the letter from Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 16 January 1891, herein.

Mary and Donette Smith, ca. 1900, photograph by Charles W. Symons, Fox & Symons, Salt Lake City, Utah. Courtesy of CHL. The photograph was colorized by the photographer in the studio in an effort to capture the natural colors of clothing, eyes, and hair. As Joseph F.’s family grew, more and more photographs were being taken at studios in Salt Lake City in an effort to document his personal family life and to share that life with his friends and family, including Martha Ann. See, for example, the letter from Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 16 January 1891, herein.

Continuing Health Issues

Martha Ann continued to suffer from sickness and injuries throughout much of the decade. She was in a great deal of pain from a second break to her knee sometime following her daughter Martha Artimissa’s marriage in 1903. Martha Ann’s grandson Elbert remembered that before her injury, Martha Ann would walk to Artimissa’s house for a home-cooked meal each day. After her injury, she was unable to make the trip, so Elbert would drop off a tin of food for her, which he would hang from the handlebars of his bicycle on his way to school. That routine continued for some time until the family got a dog and trained it to carry a container of mush in his mouth to Martha Ann’s house every day.[58]

Summary

In 1909 Joseph F. was seventy-one years old. He and his five wives, thirty-seven living children, and increasingly large third-generation family enjoyed time together whenever possible during the time he led the church to which he had dedicated his life since he was fifteen years of age.

Reflecting on life’s opportunities and challenges in 1906, Joseph F. wrote a man in Chicago who was not a member of the Church, “I would not have you think we have no cares, no sickness, anxieties, no ups and downs. Of these incidents of life we have and share, but ‘the fruit of righteousness is sown in peace of them that make peace,’ we pull together in love and confidence and hope of the glorious promise of immortality and eternal life and union now and forever.”[59]

Joseph F. knew personally about tragic losses and the compensating eternal promises of the gospel. The same held true for Martha Ann. Although by 1909 she had lost her husband, two children, and several grandchildren, she and her nine living children, along with their spouses and children, continued to build strong family relationships as they began the next decade.

Like the letters written to Martha Ann during the previous decade, Joseph F.’s known 1900–1909 letters to his sister were similarly brief and usually written in haste. On 6 May 1909, he noted, “I need not say that I have been very busy since I saw you last. I have had no time for writing letters—but have thought many times I aught to drop you just a line or two.”

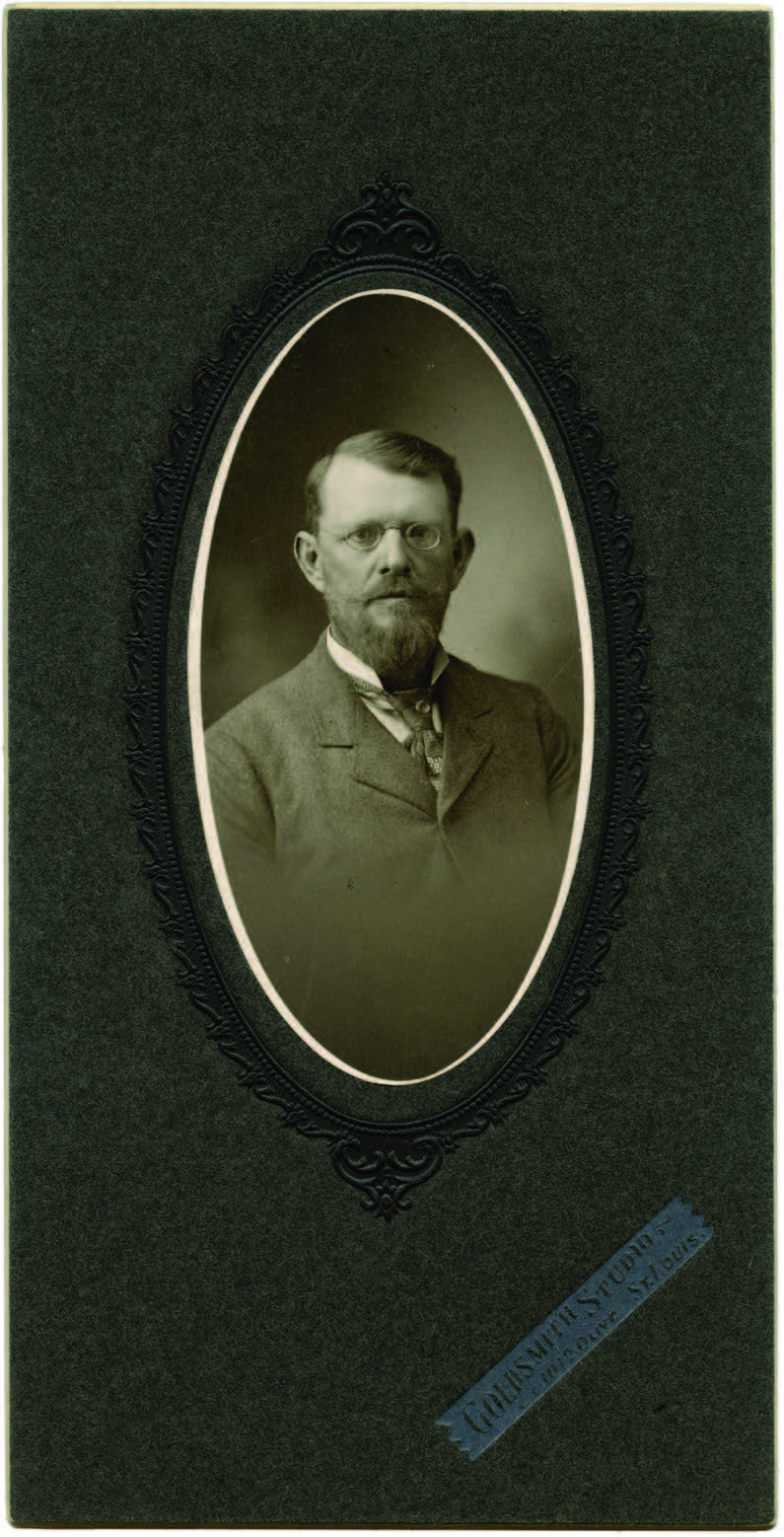

William Jasper Harris Jr., ca. 1900, photograph by Goldsmith Studio, St. Louis, Missouri. Courtesy of Carole Call King. William was Martha Ann’s oldest son. During his lifetime he had frequent interaction with Joseph F., his uncle. In some instances during the 1890s and early 1900s, Joseph F. gave strong counsel to his nephew that sometimes affected Martha Ann’s relationship with her brother. Fortunately, family loyalty trumped moments of passion and momentary discord.

William Jasper Harris Jr., ca. 1900, photograph by Goldsmith Studio, St. Louis, Missouri. Courtesy of Carole Call King. William was Martha Ann’s oldest son. During his lifetime he had frequent interaction with Joseph F., his uncle. In some instances during the 1890s and early 1900s, Joseph F. gave strong counsel to his nephew that sometimes affected Martha Ann’s relationship with her brother. Fortunately, family loyalty trumped moments of passion and momentary discord.

The brevity and family focus of the letters from this period do not hide the great love that existed between Joseph F. and Martha Ann. Every missive begins with “My own Dear Sister” or “My Dear Sister” and ends with such tender phrases as “With love to all I am affectionately your brother” and “Lovingly, I am your brother.” While these expressions might initially appear to be routine elements of courteous written correspondence, they ring true, evidenced by many years of ongoing affection and personal interest in each other’s lives as expressed in hundreds of letters between them, Joseph F.’s personal journal entries about Martha Ann and her family, and letters they wrote to extended family members and friends in which they mention each other. This devotion is also apparent in the historical record.

Notes

[1] Joseph F. moved into the Beehive House, which had become the Church President’s home in 1889, after being set apart as President of the Church. He maintained the other homes in Salt Lake City that had been built for each of his wives.

[2] We acknowledge Stephen C. Taysom’s insight on this important point.

[3] See Justin R. Bray, “Joseph F. Smith’s Beard and the Public Image of the Latter-day Saints,” in Joseph F. Smith: Reflections on the Man and His Times, ed. Craig K. Manscill et al. (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2013), 457–69; Howard D. Swainston, “Tithing,” in Encyclopedia of Mormonism, ed. Daniel H. Ludlow (New York: Macmillan, 1992), 4:1480–82; Jennifer L. Lund, “Joseph F. Smith and the Origins of the Church Historic Sites Program,” in Manscill et al., Joseph F. Smith: Reflections on the Man and His Times, 342–58.

[4] Joseph F. to Elder Walter Startup and Dear Little Naomi, 25 January 1908.

[5] Reed Smoot was a prominent businessman, member of the Utah state legislature, United States senator from 1903 to 1933, and a member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles from 1900 until the time of his death in 1941. See Milton R. Merrill, Reed Smoot: Apostle in Politics (Logan: Utah State University Press, 1990).

[6] It should be noted that while Smoot was a monogamist himself, he still accepted the principle of plural marriage as divinely inspired.

[7] Milton R. Merrill, “Reed Smoot, Apostle in Politics” (PhD diss., Columbia University, 1950), 27–28. See also Harvard S. Heath, “Smoot Hearings,” in Ludlow, Encyclopedia of Mormonism, 3:1363–64.

[8] Joseph F., as President of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, was subpoenaed to appear before a Senate hearing “to testify of the power the Church exerted over its members in general and over General Authorities in particular.” While other Apostles were questioned as well, Joseph F. received “especially harsh treatment” throughout the hearings. See Heath, “Smoot Hearings,” 3:1363–64. See also Harvard S. Heath, “Reed Smoot: The First Modern Mormon,” 2 vols. (PhD diss., Brigham Young University, 1990), 1:113.

[9] See Kathleen Flake, The Politics of American Religious Identity: The Seating of Senator Reed Smoot, Mormon Apostle (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2004).

[10] See Gary L. Bunker and Davis Bitton, The Mormon Graphic Image, 1834–1914: Cartoons, Caricatures, and Illustrations (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1983), 57–70.

[11] See Stephen C. Taysom’s forthcoming biography, “Like a Fiery Meteor”: The Life of Joseph F. Smith.

[12] “President Lyman Very Emphatic,” Deseret Evening News, October 31, 1910, 1.

[13] Francis M. Lyman letter to John W. Taylor, May 3, 1904, Francis Marion Lyman Papers; Francis M. Lyman letter to Matthias F. Cowley, May 6, 1904, in Francis M. Lyman journal, May 6, 1904; as cited in “The Manifesto and the End of Plural Marriage,” Gospel Topics, topics.lds.org (https://

[14] John Whittaker Taylor was the son of the third President of the Church, John Taylor, and a member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles until he resigned in 1905. See Andrew Jenson, Latter-day Saint Biographical Encyclopedia: A Compilation of Biographical Sketches of Prominent Men and Women in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Salt Lake City: Andrew Jenson History, 1901–36), 1:151–56.

[15] Matthias F. Cowley was a member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles until he resigned in 1905. Cowley was the father of Apostle Matthew Cowley and also of well-known FBI agent Samuel P. Cowley. See Jenson, Latter-day Saint Biographical Encyclopedia, 1:168–72.

[16] See Victor W. Jorgensen and B. Carmon Hardy, “The Taylor-Cowley Affair and the Watershed of Mormon History,” Utah Historical Quarterly 48 (January 1980): 4–36.

[17] Taylor was eventually excommunicated in 1911 for his continued involvement in new plural marriages. Cowley was also disciplined in 1911 for the same reason, but he eventually returned to full fellowship before he died in 1940.

[18] This affirmative decision from the Senate hearings was not issued until 20 February 1907.

[19] See commentary by Harvard S. Heath in his introduction to Michael Harold Paulos, ed., The Mormon Church on Trial: Transcripts of the Reed Smoot Hearings (Salt Lake City, UT: Signature Books, 2008), xix.

[20] The debt owed had reached more than two million dollars by 1898.

[21] Joseph F., in Conference Report, April 1907, 5–6.

[22] See map “Travels of Joseph F. Smith,” in Mapping Mormonism: An Atlas of Latter-day Saint History, ed. Brandon S. Plewe et al. (Provo, UT: BYU Press, 2012), 131.

[23] An extant journal for the period 17 February through 1 April 1909 highlights Joseph F.’s trip to Hawai‘i.

[24] Joseph F., journal, 24 March 1909.

[25] James A. Davis, “Historical Sites: 1903–present,” in Plewe et al., Mapping Mormonism, 136–39.

[26] Representing the life span of the Prophet; he was 38½ years old when he was murdered.

[27] “Beautiful Girl Dead,” Deseret Evening News, 29 April 1901, 1.

[28] Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 2 April 1901, herein.

[29] “Beautiful Girl Dead,” 1.

[30] Joseph F. to Edna Lambson, 26 July 1902.

[31] “Provo News Notes,” Salt Lake Herald, 27 July 1902, 5.

[32] Joseph F. to Josephine Harris, 30 July 1902.

[33] Mamie is a nickname for Mary Sophronia Smith, daughter of Joseph F. and Julina Lambson. Mary Sophronia married Alfred William Peterson on 17 December 1901. Their son Alfred William Peterson Jr. (born 25 May 1905) died 21 November 1905.

[34] See Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 22 November 1905, herein. Joseph F. suffered another loss in 1907 when Leonora Smith died, leaving behind a husband and six young children (the oldest was just ten years of age).

[35] Joseph F. to Sarah Kimball, 18 August 1907.

[36] Joseph F. to C. C. Bush, 18 February 1900. See also Joseph F. to Jos. H. Dean, 21 June 1900, where Joseph F. signs his name and adds in his own handwriting, “This was dictated to my son David, who is just learning to use the typewriter. Please excuse errors.”

[37] See Hyrum M. Smith III and Scott G. Kenney, comp., From Prophet to Son: Advice of Joseph F. Smith to His Missionary Sons (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1981), viii.

[38] See Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 2 April 1901, herein.

[39] Salt Lake Temple “Living Sealings Book A,” 1:311, entry 5581.

[40] See Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 10 April 1907, herein.

[41] See Joseph F. to Hyrum S. Harris, 10 April 1907.

[42] Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 10 April 1907, herein.

[43] Martha Ann to Joseph F., 6 March 1913, herein.

[44] Death Certificate for Marguerite Dennis, 9 January 1905, file no. 16520, Utah State Board of Health.

[45] A copy of this poem is in the editors’ possession courtesy of David J. and Ruth B. Harris.

[46] Joseph F. to E. Wesley Smith, 3 September 1907.

[47] Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 23 December 1901, herein.

[48] Joseph F., Account Book, June 1904.

[49] Joseph F., Account Book, February 1906. Joseph F. was generous to a large circle of family and friends through most of his life.

[50] The Black Hawk War was a conflict between the settlers in southern Utah and some of the native peoples in that region. See John Peterson, “Black Hawk War,” in Encyclopedia of Latter-day Saint History, ed. Arnold K. Garr, Donald Q. Cannon, and Richard O. Cowan (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2000), 106–7.

[51] See “Racing Teams Kill Pioneer,” Deseret News, 24 April 1909, 1.

[52] Joseph F. to Franklin Richards Smith, 25 April 1909.

[53] Joseph F. helped Martha Ann with some of the funeral expenses. See Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 6 May 1909, herein.

[54] Joseph F. to Will G. Farrell, 29 April 1909.

[55] Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 6 May 1909, herein.

[56] Joseph F. to Elder S. Jones, 6 May 1909.

[57] Joseph F. to Hyrum S. Harris, 4 July 1909.

[58] Ruth Mae Harris, Martha Ann, Daughter of Hyrum and Mary Fielding Smith (Orem, UT: published by the author, 2002), 139.

[59] Joseph F. to Jos. S. Sohott, 28 November 1911.