Decade Introduction

Richard Neitzel Holzapfel and David M. Whitchurch, "Decade Introduction," in My Dear Sister: Letters Between Joseph F. Smith and His Sister Martha Ann Smith Harris, ed. Richard Neitzel Holzapfel and David M. Whitchurch (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2019), 321–338.

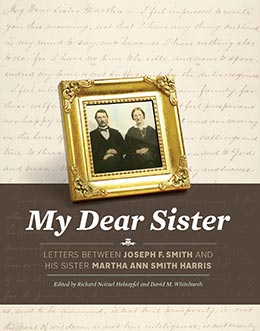

Joseph F., 6 April 1893, photograph by

Joseph F., 6 April 1893, photograph by

Charles Johnson, Sainsbury & Johnson Co.,

Salt Lake City, Utah. Courtesy of CHL.

In 1890 the Church and its members were still feeling the onerous effects of the Edmunds-Tucker Act, passed by the US Congress in 1887. Many Latter-day Saints had been incarcerated, and others, like Joseph F., had been on the underground in an effort to avoid arrest. The combined effects of the federal campaign to change Utah society were the disruption of family, community, religious, political, and economic life in the Latter-day Saint settlements throughout the Intermountain West. Additionally, the Church had been disincorporated in 1887, and the government was considering confiscating Church properties, including the temples. Finally, the Church had also been encumbered with a massive debt as it attempted to fulfill its mission to preach the gospel, gather the poor to Zion, and meet the financial obligations to fight the legal campaign against it and its members.

During this difficult period, Church leaders continued to minister to the Saints as best they could, despite the political and economic challenges facing them and the Church. Joseph F. accompanied Wilford Woodruff, George Q. Cannon, and other Church leaders on a tour to visit members in Arizona, Colorado, and New Mexico in the late summer of 1890. Joseph F. wrote his sister Martha Ann on 9 August, “I expect to leave here tomorrow or monday, on a mission to be gone some little time.”[1]

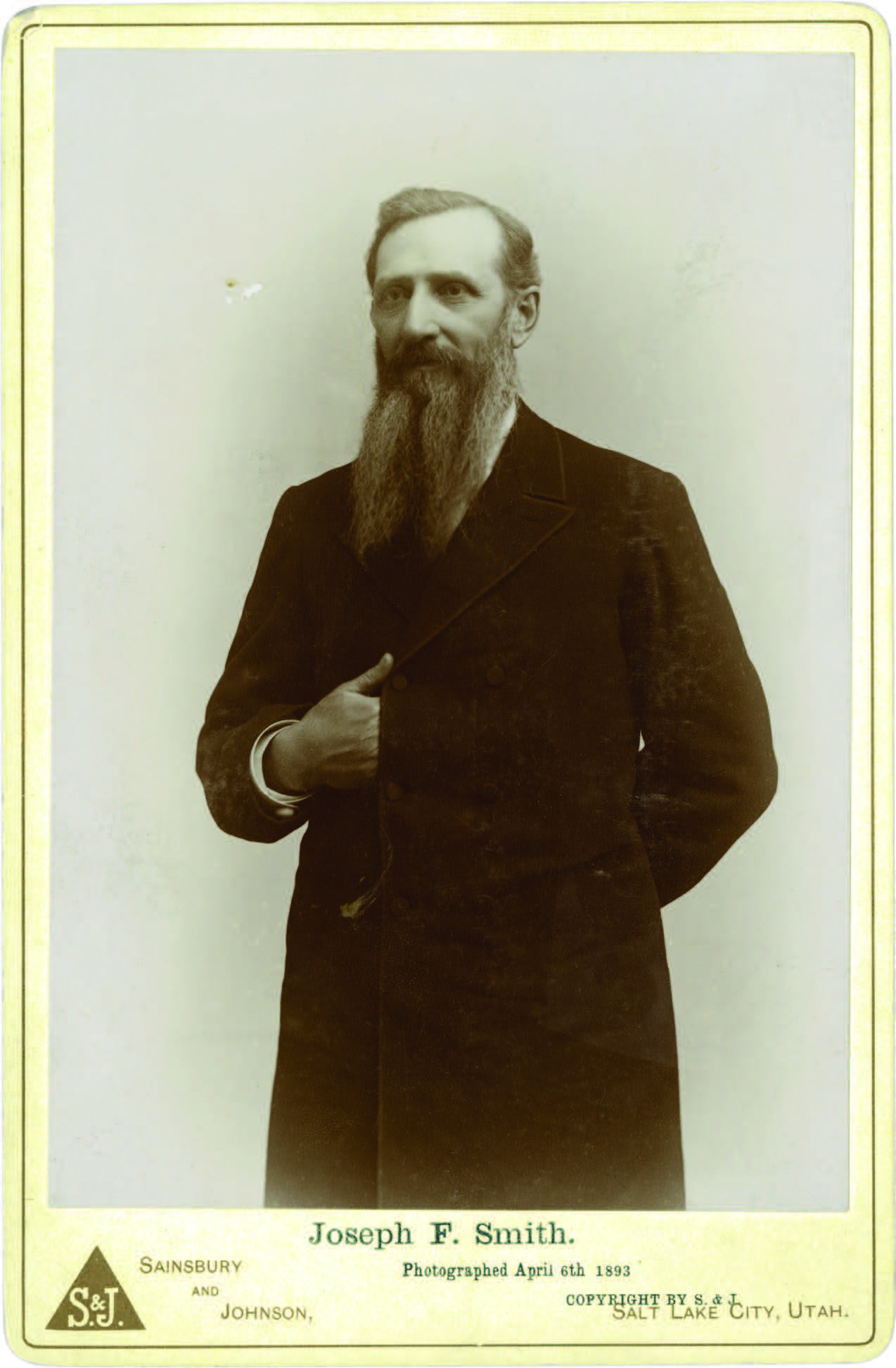

Envelope addressed to Jason Mack (Joseph F.) and postmarked “May 19, 1890.” Courtesy of CHL. Still concerned about possible arrest, Joseph F. continued to use aliases during this period to avoid detection. This particular alias was the name of Lucy Mack Smith’s brother Jason Mack (1760–1835).

Envelope addressed to Jason Mack (Joseph F.) and postmarked “May 19, 1890.” Courtesy of CHL. Still concerned about possible arrest, Joseph F. continued to use aliases during this period to avoid detection. This particular alias was the name of Lucy Mack Smith’s brother Jason Mack (1760–1835).

During the tour, they stopped for a multiday conference in Manassas, Conejos County, Colorado.[2] Joseph F. recorded in his journal details regarding a Sunday School conference, priesthood meeting, and stake conference they attended together and noted, “I spoke with good liberty” during the concluding meeting held on Monday, 18 August.[3]

By the time President Woodruff had returned to Utah from this and another short trip to California in September, he had reached an important “point in the history” of his life.[4] During this pivotal period, he had come to the conclusion that the Saints could continue practicing plural marriage and face even more pressure from the government or they could “safeguard and nourish their expanded vision of temple work” by ending the practice.[5] As a result, President Woodruff released the Manifesto in September 1890, announcing to the world that the Church was going to comply with the laws of the land by ending new plural marriages in the United States.[6]

While some Church members were relieved, others were confused about how the practice of plural marriage could simply be stopped in light of the Lord’s initial commands regarding it. Wilford Woodruff responded to some of the concerns in a stake conference in northern Utah:

The Lord has told me to ask the Latter-day Saints a question. . . . Which is the wisest course for the Latter-day Saints to pursue—to continue to attempt to practice plural marriage, with the laws of the nation against it and the opposition of sixty millions of people, and at the cost of the confiscation and loss of all the Temples, and the stopping of all ordinances therein, both for the living and the dead, and the imprisonment of the First Presidency and Twelve and the heads of families in the Church, and the confiscation of personal property of the people . . . or, after doing and suffering what we have through our adherence to this principle to cease the practice and submit to the law, and through doing so leave the Prophets, Apostles and fathers at home, so that they can instruct the people and attend to the duties of the Church, and also leave the Temples in the hands of the Saints, so that they can attend to the ordinances of the Gospel, both for the living and the dead?[7]

Although the Manifesto did not immediately put an end to all of the legal and financial challenges that the Church faced, it did allow Church leaders to appear in public for the first time in a number of years. The Saints rejoiced when, in October 1891, the entire First Presidency was present and on the stand together at the semiannual general conference in Salt Lake City. It was the first time this had happened in more than seven years.[8]

Joseph F. Smith family members at their home located at 333 West First North Street (200 North), Salt Lake City, 1891, photograph by Em. Martin, Salt Lake City, Utah. Courtesy of CHL. This was the center of Joseph F.’s world until he became President of the Church in 1901 and moved into the Beehive House.

Joseph F. Smith family members at their home located at 333 West First North Street (200 North), Salt Lake City, 1891, photograph by Em. Martin, Salt Lake City, Utah. Courtesy of CHL. This was the center of Joseph F.’s world until he became President of the Church in 1901 and moved into the Beehive House.

Relief Society Jubilee

On 17 March 1892, Joseph F. participated in the historic jubilee celebration of the founding of the Female Relief Society of Nauvoo, which fell on Thursday, the same day of the week as when the Prophet Joseph Smith met with the sisters in Nauvoo on 17 March 1842 to organize them into a group dedicated to saving souls and relieving the poor.[9] For the jubilee celebration, the Salt Lake Tabernacle was filled with Saints and decorated with bunting, flags, flowers, and portraits. General Relief Society officers and Church leaders attended and participated in the special program. In a remarkable effort to unify the sisters throughout the pioneer core area, each participating congregation offered a prayer at noon—the very same time Joseph F. prayed in the Salt Lake Tabernacle.[10]

The record is silent about Martha Ann’s participation in the jubilee celebrations in Salt Lake or Provo. However, she participated in at least one aspect of the jubilee. Local Relief Societies prepared individual Relief Society jubilee boxes for their wards on the occasion. The sisters in the local Relief Societies deposited various items, including letters written by those who had known the Prophet Joseph Smith.[11]

Martha Ann apparently deposited a letter into a jubilee box as indicated in a newspaper report in 1933: “An enjoyable time was spent by members of Camp Bonneville, Daughters of Utah Pioneers at the home of Mrs. Sarah Passey[12] Thursday afternoon. An interesting Program furnished as follows: Community singing, led by Mrs. Theresa Morgan; letters from the Relief Society Jubilee box, written by Martha Ann Smith Harris[13] and Mercy Rachel Fielding Thompson[14] 50 years ago read by Mrs. Mary H. Hafen.[15] . . . Delicious refreshments were served to 35 members and guests.”[16]

For Joseph F. and Martha Ann, this was the first of several important churchwide celebrations held during the decade. Within a month of the Relief Society jubilee celebration, the Saints celebrated again by witnessing the capstone laying for the Salt Lake Temple in April 1892. Another joyous event calling for Churchwide celebration was the dedication ceremonies for the completed Salt Lake Temple in April 1893.

Salt Lake Temple

As prosecution and government intervention in Church affairs decreased, Church leaders were able to focus more attention on other significant matters, including the completion of the Salt Lake Temple, a project that had begun in 1853.

Almost four decades later, Wilford Woodruff presided at the capstone ceremony held on 6 April 1892. During this special outdoor meeting, President Woodruff invited the Saints to complete the temple in one year so it could be dedicated on 6 April 1893. It was with a sense of celebration, then, that the Saints gathered on 6 April 1892, thirty-nine years from the time the cornerstones were laid, to rejoice together in the laying of the capstone. President Woodruff, who had pounded in the marking stake forty-five years earlier, wrote impressively in his diary that it was “the greatest day the Latter-day Saints ever saw in these mountains.”[17]

The city, already crowded for the semiannual conference, received thousands more who came for this historic event. Fifty thousand people jammed the Temple Block, while thousands more watched from adjoining rooftops, windows, and even power poles. Many more thronged the streets.

After the capstone-laying ceremony, many people remained to see the unveiling of the statue of the angel Moroni. The statue, designed by Utah-born sculptor Cyrus Dallin, was made of hammered copper covered with 22-karat gold leaf. Before nightfall, the massive figure was lowered into position on the stone ball of the 210-foot-high central east spire.

In the year that followed, carpenters, painters, plasterers, and other skilled craftsmen worked unstintingly to complete the interior of the temple. The inside of the temple was adorned with fine wood and plaster ornamental carvings, beautiful murals and paintings, mirrors, elegant curtains and draperies, the best carpets and furniture available, fine light fixtures, chandeliers, and specially ordered stained glass art windows. All things were made ready for the dedication ceremonies, which were to begin on 6 April 1893. In an effort to complete the temple on time, workers labored even on holidays. On Thanksgiving Day 1892, “nearly all the men were at work as usual,” one worker noted.[18]

The evening before the first dedication service, President Woodruff conducted nonmember guests through the building on a first-of-its-kind tour. This act was a step in reconciliation by Church leaders eager to rebuild harmony with non–Latter-day Saint neighbors after decades of hostility. Even federally appointed Utah Territorial Supreme Court justice Charles S. Zane, a longtime critic of the Church, was impressed by the quality of design, decorations, and craftsmanship. “The building is furnished opulently,” he noted in his journal after attending the open house.[19]

Wilford Woodruff, George Q. Cannon, and Joseph F., the First Presidency at the time, went to Charles Johnson’s studio for a series of group and individual photographs on this historic occasion.

Finally, the culmination of forty years of effort and sacrifice climaxed when President Woodruff entered the temple the morning of 6 April 1893. “The Temple Block gates opened at 8:30, and the street was packed long before that hour,” one priesthood leader noted. Two hours were required “to admit, one by one, the 2200 people” into the large upper assembly hall of the temple.[20]

Thomas Griggs, a member of the Tabernacle Choir, arrived at the south gate at 8:20, but the line was so long that “it was 9:55 A.M. when I was 10 feet from the [gate],” he wrote. “Wind, dust and a little rain had come and it was very uncomfortable, to be ended by the door keeper announcing . . . ‘No more can be admitted.’ . . . Being well known as a member of the choir [I was] . . . soon at the south west entrance and hurriedly passed through.”[21]

The focus of the service was the prayer of dedication offered by the aged prophet, “kneeling on a plush covered stool provided for the purpose” and reading the prayer he had prepared that would be read in each successive service of the many sessions.[22]

Following the conclusion of the dedication sessions, Joseph F. reported, “We all had a most precious time during the dedication services.”[23]

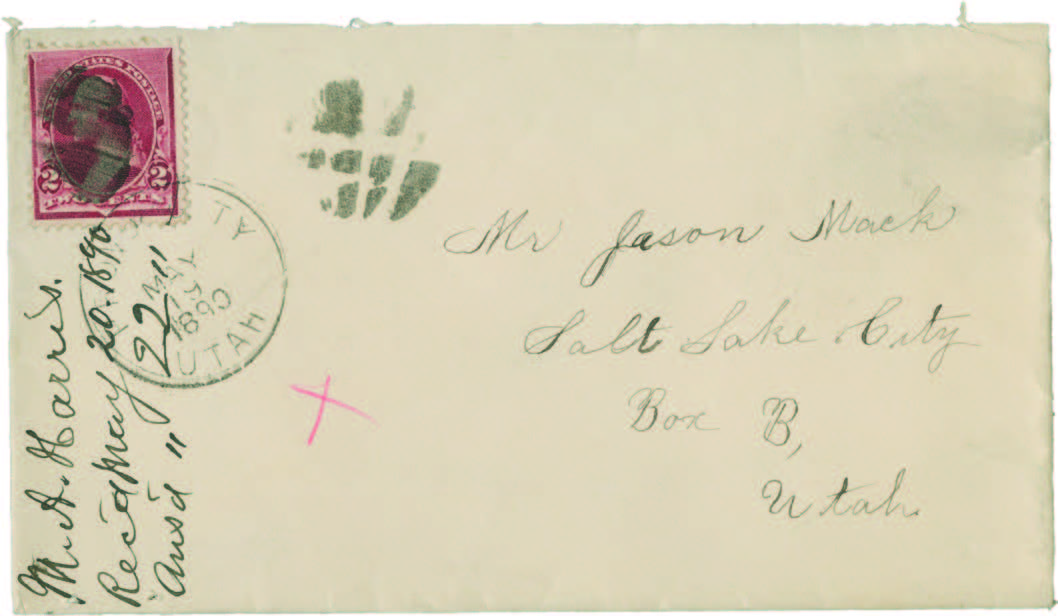

Zina Christine Harris and George Thomas Furner, ca. 18 October 1893, photograph by T. E. Daniels Jr., Provo, Utah. Courtesy of Carole Call King. Zina’s uncle Joseph F. performed the marriage ceremony in the recently dedicated Salt Lake Temple.

Zina Christine Harris and George Thomas Furner, ca. 18 October 1893, photograph by T. E. Daniels Jr., Provo, Utah. Courtesy of Carole Call King. Zina’s uncle Joseph F. performed the marriage ceremony in the recently dedicated Salt Lake Temple.

In October 1893 Joseph F. had the distinct privilege of performing the marriage sealing of Martha Ann’s daughter Zina Christine Harris (1876–1958) and George Thomas Furner (1868–1903) in the Salt Lake Temple.[24]

Mary F. Smith, Ida Bowman, Donette Smith, and Maggie Bowman, 17 February 1894. Courtesy of CHL. The individuals in the photograph are identified by numbers one through four. The reverse side reads, “To Papa. From Mamie & Donnie. Apr. 2d 1894. Taken Feb. 17. 1894. 1 Mary F. Smith – 24 2 Ida Bowman 21 3 Donnette Smith 21 4 Maggie Bowman 23.” Ida Bowman married Joseph F. Smith’s oldest son, Hyrum Mack, on 15 November 1895, less than two years after this photograph was taken. On the day of Hyrum Mack’s temple sealing, Heber J. Grant set him apart as a missionary to serve in Great Britain. He departed on his mission the next day, 16 November 1895, and returned on 7 March 1898.

Mary F. Smith, Ida Bowman, Donette Smith, and Maggie Bowman, 17 February 1894. Courtesy of CHL. The individuals in the photograph are identified by numbers one through four. The reverse side reads, “To Papa. From Mamie & Donnie. Apr. 2d 1894. Taken Feb. 17. 1894. 1 Mary F. Smith – 24 2 Ida Bowman 21 3 Donnette Smith 21 4 Maggie Bowman 23.” Ida Bowman married Joseph F. Smith’s oldest son, Hyrum Mack, on 15 November 1895, less than two years after this photograph was taken. On the day of Hyrum Mack’s temple sealing, Heber J. Grant set him apart as a missionary to serve in Great Britain. He departed on his mission the next day, 16 November 1895, and returned on 7 March 1898.

Additionally, the work to redeem the dead increased as many more members were able to take advantage of attending the newly dedicated temple in the largest metropolitan area in Utah. Joseph F. and Martha Ann were among those who did work for their own ancestors. Their enthusiasm can be seen in a letter Joseph F. wrote to Martha Ann in 1897: “We have agreed to meet at the Temple in this city on Wednesday, September 1st, to attend to the sealing of all the children living and dead to their father and mothers. . . . We have had a glorious time in the Temple today. I sealed sixteen couples, including our seventh great grandfather and mother . . . and Grandfather and mother Joseph and Lucy Mack Smith, and the work of sealing of children is nearly all completed. I am very anxious to have father’s work done.”[25]

The newly completed and dedicated temple in Salt Lake City became a central focus of Joseph F.’s life for the next twenty-five years as he visited the upper rooms in the Salt Lake Temple for weekly meetings with the First Presidency and Quorum of the Twelve Apostles.[26] Additionally, he served as the Salt Lake Temple president from 1898 to 1911.

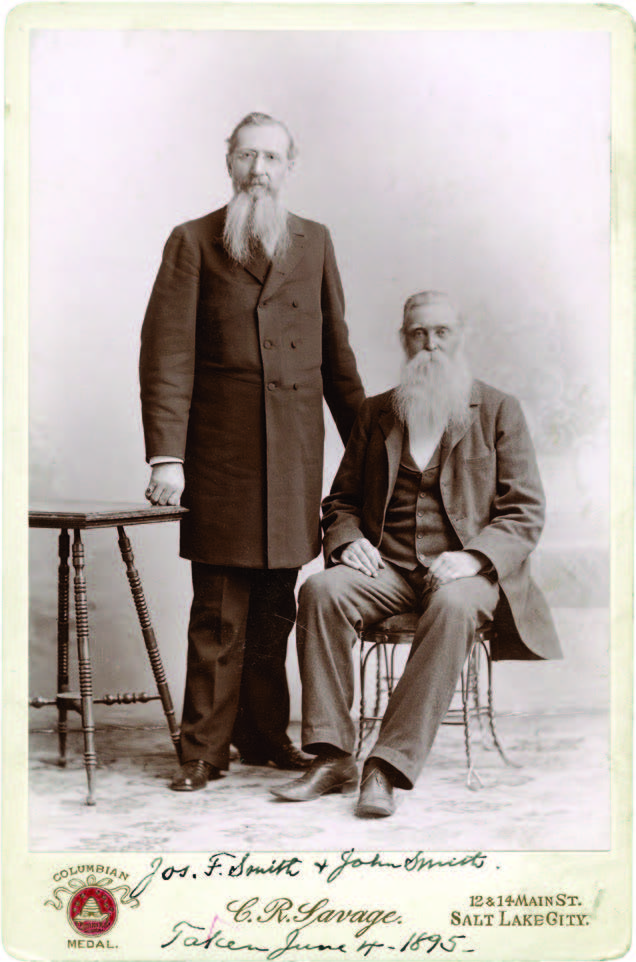

Joseph F. and John Smith, 14 June 1895, photograph by C. R. Savage, Salt Lake City, Utah. Courtesy of CHL. John and Joseph F. Smith were half brothers, sons of Hyrum Smith. Later, when Joseph F. Smith became President of the Church in 1901, it was only the second time in the Church’s history that two brothers occupied the positions of President and Patriarch at the same time (the first time being Joseph Smith Jr. and Hyrum Smith). On the photograph “Jos. F. Smith & John Smith. Taken June 4 1895” is written in Joseph F.’s hand.

Joseph F. and John Smith, 14 June 1895, photograph by C. R. Savage, Salt Lake City, Utah. Courtesy of CHL. John and Joseph F. Smith were half brothers, sons of Hyrum Smith. Later, when Joseph F. Smith became President of the Church in 1901, it was only the second time in the Church’s history that two brothers occupied the positions of President and Patriarch at the same time (the first time being Joseph Smith Jr. and Hyrum Smith). On the photograph “Jos. F. Smith & John Smith. Taken June 4 1895” is written in Joseph F.’s hand.

Church and Politics

A new political landscape appeared following the publication of the Manifesto as some former enemies of the Church threw down their weapons of war and collaborated with the Saints to promote the economic welfare of the Utah Territory. More importantly, they also now freely promoted statehood, which had been denied at every turn since the Saints began to settle the Great Basin in 1847. Church leaders knew statehood would provide greater independence in local affairs by allowing Utah residents to elect their own state officers, answerable to the local electorate, rather than potentially unsympathetic territorial appointees selected by the federal government.

There appeared to be two main obstacles preventing the people of Utah from receiving statehood. The first was the Church’s position on plural marriage, which had been largely resolved when the 1890 Manifesto was announced.[27] The other impediment was the political solidarity of Church members that was often viewed as antidemocratic.[28] To overcome this barrier, Church leaders decided to disband the People’s Party and encourage Latter-day Saints to join one of the two national parties, the Republican and Democratic Parties. The political party system in Utah had previously been divided almost exclusively along lines of religious affiliation, with most Latter-day Saints supporting the People’s Party and most others supporting the local Liberal Party (distinct from the national Democratic Party).

As the People’s Party was disbanded, many Latter-day Saints were attracted to the Democratic Party because the Republican Party had led the effort to end plural marriage in Utah and was seen as less sympathetic to the desires and aspirations of the members of the Church.

In order to create greater political balance among members, Church leaders encouraged some members to also join the Republican Party. Several Church leaders volunteered, including John Henry Smith (1848–1911) and Francis M. Lyman (1840–1916), both members of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles. Joseph F. also joined the Republican Party and became a major supporter of it for the rest of his life. The Church then released a statement in local newspapers: “The Church will not assert any right to control the political action of its members. As officers of the Church they disclaim such right. . . . All that is asked for the Church is that it shall have equal rights before the law.”[29] Ultimately, their efforts for home rule succeeded when in January 1896 Utah was made the forty-fifth state.

Mary Schwartz and Joseph F. family, 19 December 1896, photograph by C. R. Savage, Salt Lake City, Utah. Courtesy of CHL. From left: Mary Schwartz, Calvin, James, Samuel, and Joseph F., who identified himself as “Papa.”

Mary Schwartz and Joseph F. family, 19 December 1896, photograph by C. R. Savage, Salt Lake City, Utah. Courtesy of CHL. From left: Mary Schwartz, Calvin, James, Samuel, and Joseph F., who identified himself as “Papa.”

Travels and a New Prophet

Economic demands and heavy administrative responsibilities continued to press on Church leaders, particularly President Woodruff. In 1895 he traveled to Alaska to seek relief from an increasing number of health concerns. His counselors, George Q. Cannon and Joseph F., accompanied him.[30] Joseph F. mentioned this trip in his letter to Martha Ann, dated 27 September 1895: “Our recent trip to the north was a rest and a change, such as I seldom get, but which was a gracious boon to me both physical and mental and I am very thankful for it.”[31]

President Woodruff again sought relief when he traveled to the California coast in 1898. While there, in the home of a friend, he died quietly in his sleep on 2 September 1898. Eleven days later on 13 September 1898, President Lorenzo Snow was sustained as the new President of the Church. He selected George Q. Cannon and Joseph F. as his counselors.[32]

Joseph F. (seated in the center) and Sarah Ellen Smith and party, Lā‘ie Plantation Mission Home, 3 February 1899, photograph by Otto Hassing, Honolulu, Hawai‘i. Courtesy of CHL.

Joseph F. (seated in the center) and Sarah Ellen Smith and party, Lā‘ie Plantation Mission Home, 3 February 1899, photograph by Otto Hassing, Honolulu, Hawai‘i. Courtesy of CHL.

Two months after the reorganization of the First Presidency, Joseph F. celebrated his sixtieth birthday in November 1898. During the following year, Joseph F. made another trip to Hawai‘i. He took his ailing wife Sarah Ellen (1850–1915) with him, feeling that the trip would improve her health.[33] Joseph F., Sarah, and two of their daughters left for Hawai‘i on 7 January 1899.[34]

Although Joseph F.’s letters to Martha Ann make no mention of the financial burdens confronting the Church, the First Presidency was greatly concerned. The enormous debt resulted partly from government confiscation of Church property and members’ limited means in donating to the Church.

Immediately after being sustained as President of the Church, President Snow commenced a campaign to revitalize the practice of paying tithing. He held a special solemn assembly about tithing in July 1899, and the October general conference that year was dedicated to the theme. In that conference Joseph F. told the Saints:

We are not talking to you about paying your tithing because it is a pleasure to do so, or because we desire to harp upon that principle; but we are doing it because the necessities of the people are such that it becomes obligatory upon the leaders of the Church to say something upon this principle, that not only the people may do their duty in regard to this law, but that there may be something in the storehouse of the Lord with which to meet the necessities of the people; for the necessities of the Church are the necessities of the people.[35]

As a result of this increased emphasis, tithing revenue more than doubled from 1898 to 1899.[36] As a member of the First Presidency, Joseph F. played a particularly important role in helping extricate the Church from debt. In fact, later as President of the Church he would pay off the final debt.

As the decade ended, Joseph F. confided in his son Joseph Fielding Smith about his continuing struggle to manage his correspondence demands, both ecclesiastical and personal: “I am so busy during office or working hours that I cannot get a moment to dictate to our typewriter. And she loves working promptly at quitting time, and I am so unfortunate as to have no son or daughter qualified to write short hand or take dictation on typewriter nearly everyone of president’s cannons boys and Leroi Snow can both write short hand and typewrite. I feel condemned that I have not given my children more time for study and greater opportunities to learn. Still I do not know how I could have done more with my large responsibilities and limited means.”[37]

Continuing Health Challenges

The letters between Joseph F. and Martha Ann frequently mention Martha Ann’s ill health. In 1894, for example, Martha Ann fell and splintered her knee. The injury confined her to bed for six months and required her to use crutches for another year and a half.[38] One of her grandchildren remembered that during this time their “aunt” Zina Young (1821–1901) came from Salt Lake to care for Martha Ann. While there, Zina promised Martha Ann that she would be healed and “told her that she would walk again and be made well, with many other grand promises, which were surely fulfilled.”[39]

Mary Emily, Martha Ann, and Lucy Smith Harris, ca. 1890. Courtesy of Carole Call King.

Mary Emily, Martha Ann, and Lucy Smith Harris, ca. 1890. Courtesy of Carole Call King.

Martha Ann did recover, but within only a few years she fell again, this time breaking her right arm. In addition to all her injuries, she suffered from severe rheumatism. Despite her injuries and ailments, however difficult, Martha Ann used the time confined to her bed to sew, embroider temple aprons, and make other items of clothing for her family, grandchildren, friends, and neighbors.[40] Joseph F. alludes in one of his letters to his sister’s devotion to family and her dedication to service: “How you can ‘wait on the sick’, ‘make Temple clothing for one and another’ and take care of your own family is almost a mystery. I am thankful, however that the Lord gives you the strength to do it.”[41]

Most letters during this decade focus almost entirely on news of family and friends. For example, in a letter dated 25 October 1898, Joseph F. informs his sister of the birth of his grandson, George Smith Nelson.[42]

Joseph Smith Nelson and George Smith Nelson, 22 April 1899. Photograph by C. R. Savage, Salt Lake City, Utah. Courtesy of CHL. Joseph F.’s daughter Leonora Smith Nelson provided information on the back of this photograph: “To Grandpapa with our affections Joseph S. Nelson born Feb. 22 99. George S. Nelson Oct. 20, 98. Photographed April 22, 99.” Joseph F. added, “Grandpa’s own little boys.”

Joseph Smith Nelson and George Smith Nelson, 22 April 1899. Photograph by C. R. Savage, Salt Lake City, Utah. Courtesy of CHL. Joseph F.’s daughter Leonora Smith Nelson provided information on the back of this photograph: “To Grandpapa with our affections Joseph S. Nelson born Feb. 22 99. George S. Nelson Oct. 20, 98. Photographed April 22, 99.” Joseph F. added, “Grandpa’s own little boys.”

Interestingly, nothing is said in the known surviving letters from this decade about the 1890 Manifesto, the completion and dedication of the Salt Lake Temple in 1893, or Utah’s achieving statehood in 1896 after decades of effort.

Jonathan and Lucy Smith Harris Simmons, 15 June 1898, photograph by Ad. Anderson, Provo, Utah. Courtesy of Carole Call King. This photograph was taken on the day they were married.

Jonathan and Lucy Smith Harris Simmons, 15 June 1898, photograph by Ad. Anderson, Provo, Utah. Courtesy of Carole Call King. This photograph was taken on the day they were married.

Increasingly, rituals of birth, marriage, sickness, and death intertwined in Martha Ann and Joseph F.’s lives. For example, Joseph F. mentioned the pain of losing his eighth child when four-year-old Ruth (1893–98) died in March 1898:

We have, as you perhaps know, for a long time been passing under most trying ordeals of sickness. Aunt Sarah E. was taken with Typhoid fever—then Emily, with Scarlet fever, then Alice M. with Typhoid fever, then Rachel with scarlet fever—then Edith, and next our Dear little Ruth—who—in spite of all we could do by faith and prayer and skill, on the 17th inst—passed away—leaving us heart-broken and bowed down to the dust in grief & sorrow for our irreparable temporal loss.[43] You will no doubt remember our sweet little Ruth—to be loved—she needed only to be seen. To be admired she had but to be heard—for she was one of the brightest little Souls I ever saw. But O! my Soul, we have had to yield her spirit up to God who gave her, and her sweet little body to the grave. She was buried to day. I should have written you sooner but to tell the truth my poor heart has been in the icey chamber with the cherished lovely form of my darling babe! I could not write.[44]

Ruth Smith, daughter of Edna Lambson and Joseph F., 16 May 1897. Courtesy of CHL. Ruth was born on 21 December 1893 and died on 17 March 1898, ten months after this photograph was taken. Joseph F. mentions her death in a letter to Martha Ann, 19 March 1898. On the reverse side Joseph F. wrote, “Ruth May 16th ’97. My Darling little Ruth! Papa.”

Ruth Smith, daughter of Edna Lambson and Joseph F., 16 May 1897. Courtesy of CHL. Ruth was born on 21 December 1893 and died on 17 March 1898, ten months after this photograph was taken. Joseph F. mentions her death in a letter to Martha Ann, 19 March 1898. On the reverse side Joseph F. wrote, “Ruth May 16th ’97. My Darling little Ruth! Papa.”

For Martha Ann, the joy of celebrating the marriage of her daughter Lucy Smith Harris to Jonathan Simmons in Utah County on 15 June 1898 was followed by a tragedy when a grandson died after falling from a chair in 1898.[45] As Joseph F. noted earlier, “Your life has been a hard one as was that of our ever dear and precious Mother.[46] Surely there is a noble reward awaiting you after your trials. Cheer up. If I live and prosper I shall not forget you. My heart is full, my eyes moist. I am ever truly Joseph F.”[47]

A New Home In Provo

Martha Ann and William Jasper built a larger two-story home sometime around 1890 on the same lot where the adobe home had been built. Their daughter Sarah Harris noted, “Thirteen in the family lived in these two rooms [in the adobe home] until the youngest child (myself) was nine years old, when a larger and better house was built.”[48] The new home provided the family with a parlor and additional bedrooms, but it lacked a kitchen, dining room, and bathroom at first. The basement remained unfinished for years. Laundry was still being done outside during the summer, and water came from an artesian well near the north door of the old adobe house. The family continued to cook and eat in the small adobe home, and the outhouse in the backyard continued to be used for some time. Despite building a house, Martha Ann’s economic situation remained difficult.[49] Eventually, to bring in much-needed income, Martha Ann rented the adobe home and moved into the large home full-time.[50] In the big house, a bedroom on the main floor was converted into a kitchen to accommodate the new arrangement. When, after some time, an indoor bathroom was installed by utilizing part of the parlor space, Martha Ann was elated. Her granddaughter Edna Mae recalled, “I remember her saying when the bathroom was finished, she went in there and fell on her knees and offered a prayer of thanksgiving. At last, she didn’t have to go way out to the outhouse in the cold.”[51] Around this time, Martha Ann and William Jasper took in “BY Academy students as boarders” to help augment their family income.[52]

Summary

By the end of December 1899, Joseph F. was sixty-one years old. His five wives had borne forty children between 1858 and 1899: Julina had borne eleven children and buried one child; Sarah had borne eleven children and buried four children; Edna had borne ten children and buried three children; Alice had borne three children; and Mary had borne five children, of which one had died. Additionally, four more children were part of the family in 1899—one had been adopted, and three others became part of the family when Joseph F. married Alice in 1883.

Joseph F. Smith family portrait, 13 November 1898, photograph by Fox and Symons, Salt Lake City, Utah. Courtesy of CHL. Group photograph taken on his sixtieth birthday with his five wives and his children.

Joseph F. Smith family portrait, 13 November 1898, photograph by Fox and Symons, Salt Lake City, Utah. Courtesy of CHL. Group photograph taken on his sixtieth birthday with his five wives and his children.

Martha Ann was fifty-eight years old by the end of this decade. Between 1852 and 1882, she had given birth to eleven children, with all remarkably still alive in 1899. She and William had raised the family in a two-room adobe home in Provo but had finally built a second larger home on the same lot. With each generation of grandchildren and great-grandchildren, of course, the family continued to enlarge. Joseph F. often made mention of his sister’s growing family in his letters to her during this decade—for example, “Hoping You and William are well, and all the children, & childrens children, I am Your brother Joseph.”[53]

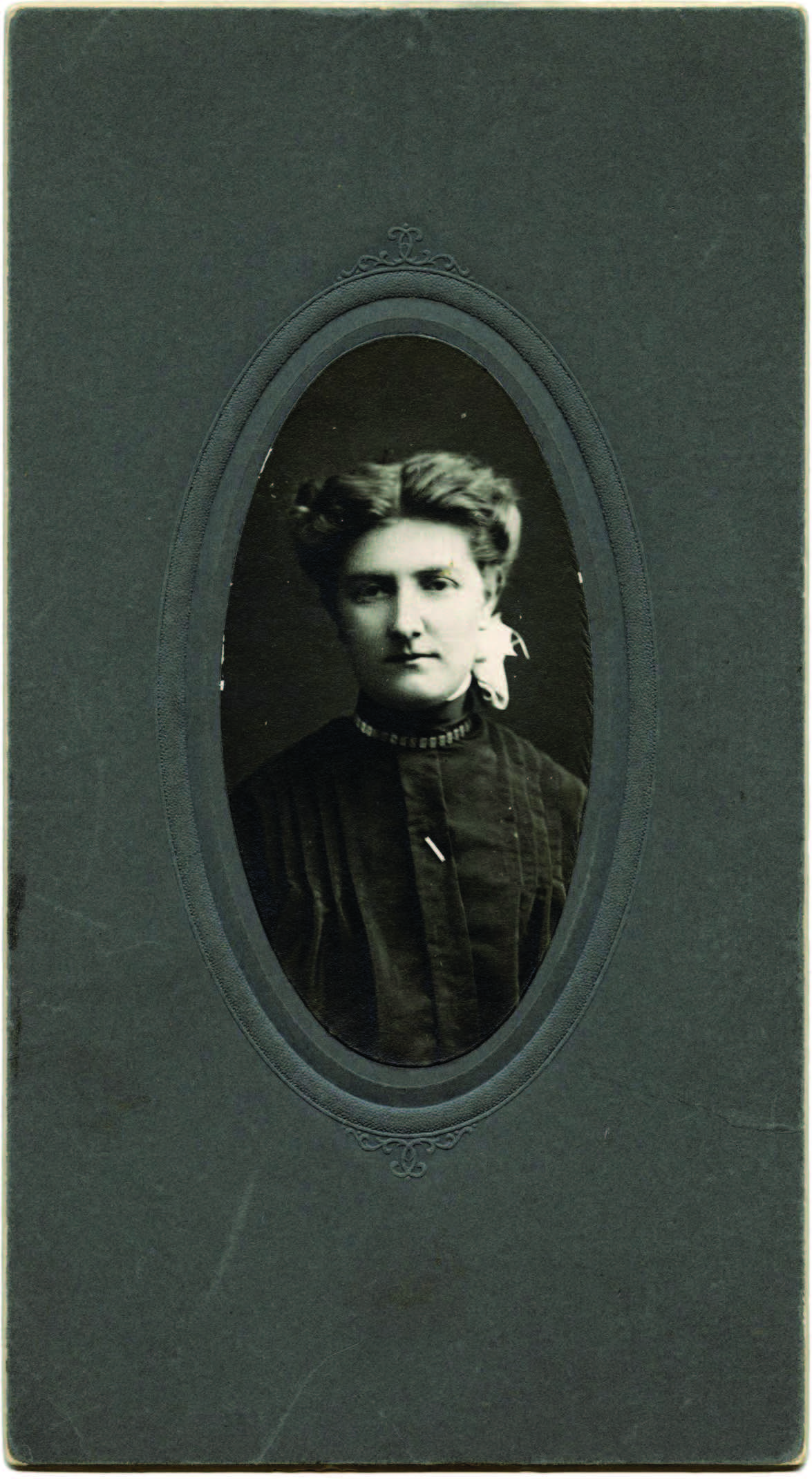

Sarah Lovina Harris, ca. 1899. Born in 1882, Sarah was Martha Ann and Williams’s last child. Courtesy of Carole Call King.

Sarah Lovina Harris, ca. 1899. Born in 1882, Sarah was Martha Ann and Williams’s last child. Courtesy of Carole Call King.

The letters written in the 1890s still show Martha Ann living in Provo in very humble circumstances. As noted above, in addition to her family’s challenging economic situation, she was plagued by poor health throughout the decade. Joseph F. understood and appreciated the differences in their lives and tried to comfort and honor his sister Martha Ann for her goodness and faithfulness:

What a comfort it is to know that all will be rewarded, eventually, according to their works, and the intents of their hearts. The noblest, and therefore in the true sense, the highest ideas that men can entertain are those of “faith, hope and charity”, and in all these I award you credit of being superior to most women, else you would have succumbed to your misfortunes long ago. but your hope, your charity for others, and your faith in providence have sustained you. In temporal things God has dealt more mercifully with me than with you, as it now seems, but who can tell what the end may be?[54]

The letters of this decade also reveal the challenges of having a conversation with another person through written correspondence. In a series of five letters written between 17 April and 22 May 1890, Joseph F. and Martha Ann misunderstand each other on almost every point.[55] We cannot always discern the meaning and intent in every letter. Joseph F. and Martha Ann shared a common human dilemma in misunderstanding each other from time to time. Adding to the complex and interconnected aspects of their letter-writing relationship was the fact that they also communicated with other family members and friends through letters that were often part of their dialogue.[56] This naturally increased the number of people in the conversation and also the possibility of misunderstanding.

As discussed earlier, Joseph F. sometimes felt dutybound to counsel his sister’s children. For example, Franklin Hill Harris (1867–1947) and his brother Hyrum Smith Harris (1863–1924) were working in Salt Lake City, and Joseph F. wrote a letter expressing his wish that they be fully engaged at Church and accept a call to become home missionaries.[57] In reply Frank (the name he was known by) reported that he had gone to Provo and “got my recommend from the Bishop and was roled in to the Ninttheen ward tonight. I will go up and get ordained a Elder tomorrow night.” Frank added to his report, “Mother Says when I wrote to you to give her Love to you. I every remain your Loving Nephew.”[58] Joseph F. received the letter on 25 March and responded to it on the same day.[59]

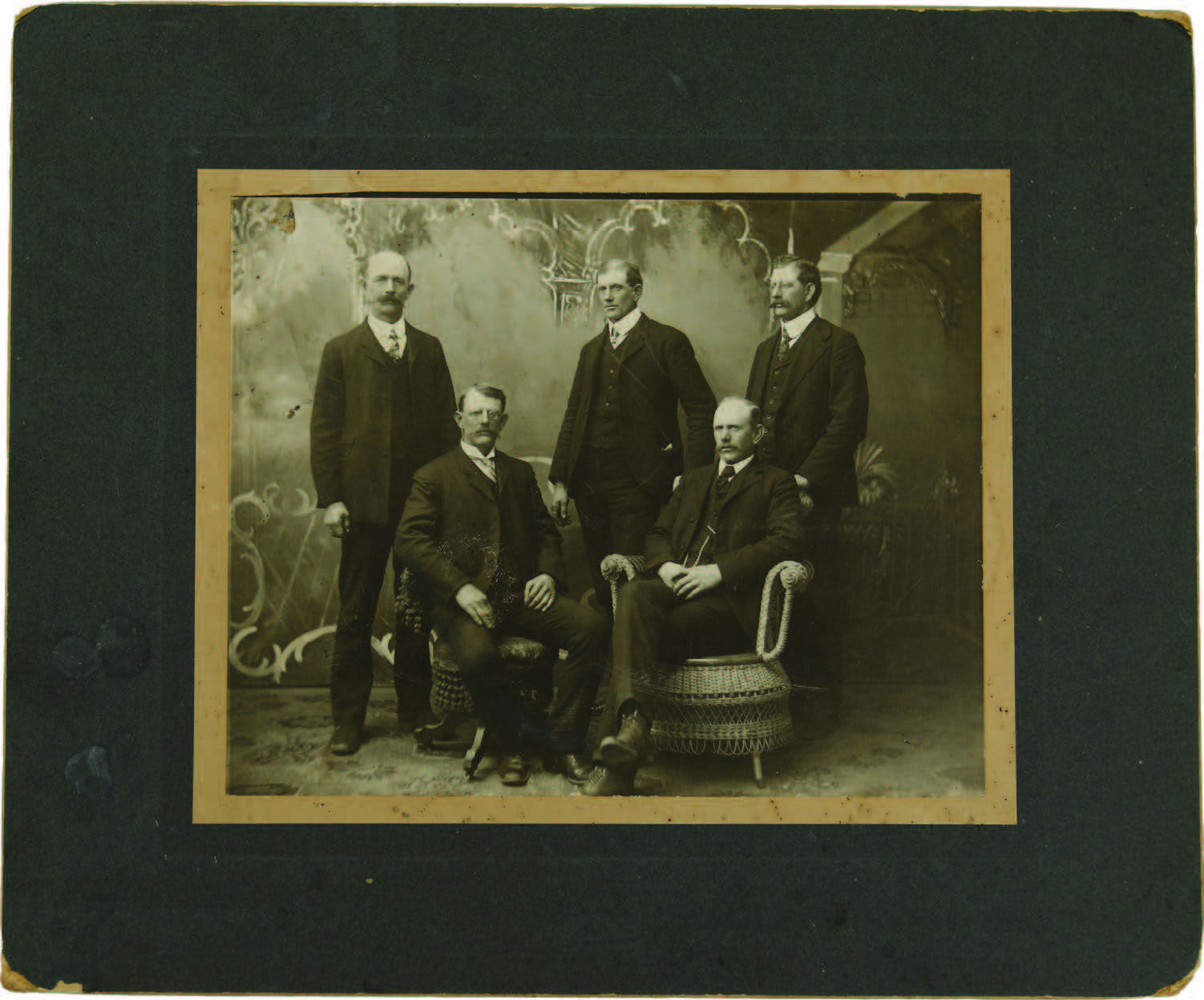

Martha Ann and William Jasper Harris’s sons, ca. 1898. Courtesy of David and Ruth Harris. Seated, left to right: William Jasper Harris Jr. and Franklin Hill Harris. Standing, left to right: Hyrum Smith Harris, Joseph Albert Harris, and John Fielding Harris.

Martha Ann and William Jasper Harris’s sons, ca. 1898. Courtesy of David and Ruth Harris. Seated, left to right: William Jasper Harris Jr. and Franklin Hill Harris. Standing, left to right: Hyrum Smith Harris, Joseph Albert Harris, and John Fielding Harris.

In a series of letters written in 1891, Joseph F. provided counsel intended directly for Martha Ann’s sons. He began his letter, “I feel interested in the welfare of your family, for their welfare is yours.”[60] He added, “My understanding of Joseph’s course, gives me confidence in him. I like his continuity and steadiness and persistance in his purpose, I like the spirit and disposition I have seen of John, I believe them both to be good boys. and I feel in my heart to bless them. Willie and Hyrum and Frank have my love and my most earnest faith and prayer, I love them because they are my sisters boys, because they are my Nephews, and because I feel in my heart that they are good boys, but we have all much to learn.”[61]

Joseph F. later provided additional counsel and direction for two of Martha Ann’s daughters. He cautiously justified his intervention: “You may think it is ‘none of my business’, to worry over your affairs, but, I cannot help it.”[62] Obviously, Joseph F. felt he should provide advice to Martha Ann’s children, and while the advice was not always accepted or appreciated, he developed a warm relationship with his nephews and nieces as they continued to write him asking for advice and help, requesting that he perform their temple sealings, visiting him in Salt Lake City, and sending him photographs and warm salutations.

Notes

[1] Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 9 August 1890, herein.

[2] Manassas was an early Latter-day Saint settlement located directly north of the New Mexico border in the San Luis Valley.

[3] See Joseph F., journal, 18 August 1890.

[4] Wilford Woodruff, journal, 25 September 1890, in Wilford Woodruff’s Journal: 1833–1898 Typescript, ed. Scott G. Kenney, vol. 9, 1 January 1889 to 2 September 1898 (Midvale, UT: Signature Books, 1985), 112–14; spelling corrected for readability.

[5] Richard E. Bennett, “‘Which Is the Wisest Course?’ The Transformation in Mormon Temple Consciousness, 1870–1898,” BYU Studies Quarterly 52, no. 2 (December 2013): 8.

[6] The intent and scope of the 1890 Manifesto was discussed during the administrations of Wilford Woodruff and Lorenzo Snow. Eventually, Joseph F. issued the Second Manifesto in 1904, which announced that no new plural marriages would be authorized, even outside the boundaries of the United States. It also stated that any person who performed or participated in new plural marriages would be subject to Church discipline, including excommunication. By October 1905, Latter-day Saint Apostles John W. Taylor and Matthias F. Cowley were forced to resign from the Quorum of the Twelve in the wake of the Smoot hearings. Taylor was eventually excommunicated in 1911 for continued opposition to the Second Manifesto.

[7] Cache Stake Conference, Logan, Cache County, Utah Territory, 1 November 1891. See “Remarks,” Deseret Weekly News, 14 November 1891, 658. Further excerpts from this conference are contained in Official Declaration 1 in the Doctrine and Covenants.

[8] Joseph F. was greeted with a warm welcome and recorded, “I shook hands with my friends until my hand and arm felt lame.” Joseph F., journal, 4 October 1891.

[9] See “The Relief Society Jubilee,” Woman’s Exponent, 15 January and 1 February 1892, 108.

[10] General Relief Society leaders Zina D. H. Young, Jane S. Richards, and Bathsheba W. Smith invited the Relief Society sisters to participate in the celebration “at 12 o’clock p.m. (high noon) let all join in a universal prayer of praise and thanksgiving to God.” “Letter of Greeting,” Woman’s Exponent, 15 January and 1 February 1892, 108. See “The Relief Society Jubilee,” Deseret Weekly, 26 March 1892, 483–86.

[11] Later, when the box was opened, some of the items were given to family members. For example, Tamma Durfee Miner wrote a long letter for the Relief Society jubilee box of the Utah Stake Relief Society (copy in possession of the authors). Hannah Sorensen wrote a brief autobiographical sketch as a letter addressed to her youngest son and included a “picture as I look now, and a little relic for your wife, or your daughter, also a lock of my hair.” As cited in Robert S. McPherson, Life in a Corner: Cultural Episodes in Southeastern Utah, 1880–1950 (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2015), 62. Another ward Relief Society jubilee box was donated to the Daughters of the Utah Pioneers Museum in Springville, Utah. “Jubilee Box donated to DUP museum,” Springville Herald, 31 March 1993, 4.

[12] Martha Ann’s daughter Sarah Harris Passey.

[13] A document in the CHL dating from about fifty years before the time of the 1933 report may be the one mentioned in the article: “Martha Ann Smith Harris to Posterity,” 22 March 1881.

[14] Mercy Rachel Fielding prepared an autobiography with instructions that it be given to her oldest female descendant in 1930. See “Mercy F. Thompson Autobiographical Sketch, 1880.”

[15] Mary H. Hafen was Martha Ann’s granddaughter and the daughter of Franklin Hill Harris and Josie Parkes Harris.

[16] “Pioneer Daughters at Regular Meeting,” Sunday Herald (Provo, UT), 12 February 1933, 5.

[17] Wilford Woodruff, journal, 6 April 1892.

[18] Samuel W. Richards, journal, 24 November 1892.

[19] Charles S. Zane, journal, 5 April 1893, Charles S. Zane Papers, Illinois State Historic Library, Springfield, Illinois.

[20] Joseph Henry Dean, journal, 6 April 1893.

[21] Thomas C. Griggs, journal, 6 April 1893.

[22] Joseph Henry Dean, journal, 6 April 1893.

[23] Joseph F. to Jesse B. Martin, 27 April 1893.

[24] Salt Lake Temple “Living Sealing Book A,” vol. 1, entry 206.

[25] Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 25 August 1897, herein.

[26] Francis M. Gibbons, Joseph F. Smith: Patriarch and Preacher, Prophet of God (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1984), 190–91.

[27] For several years following the 1890 Manifesto, some Church leaders and members remained confused about how it was to be interpreted. Eventually, Joseph F. issued a Second Manifesto in 1904 to make it absolutely clear that the Church would no longer sanction or permit new plural marriages. Church leaders and members who refused to comply with the Second Manifesto were disciplined. See Brian C. Hales, Modern Polygamy and Mormon Fundamentalism: The Generations after the Manifesto (Salt Lake City, UT: Greg Kofford Books, 2006), 51–74. See also Thomas G. Alexander, Mormonism in Transition: A History of the Latter-day Saints, 1830–1890 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1986), 60–73, 328–31.

[28] Edward Leo Lyman, “Utah Statehood,” in Encyclopedia of Mormonism, ed. Daniel H. Ludlow (New York: Macmillan, 1992), 4:1502–3.

[29] “They Have Neither Truth Nor Shame,” Deseret Evening News, 6 July 1891, 4.

[30] Richard Neitzel Holzapfel, “New Photographs of Wilford Woodruff’s Trip to Alaska, 1895,” BYU Studies 39, no. 2 (2000): 144–49.

[31] Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 27 September 1895, herein.

[32] See Richard Neitzel Holzapfel and Ronald Fox, “Photographs of the Fourteen Apostles of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, September and October 1898,” BYU Studies Quarterly 56, no. 4 (2017): 68–92.

[33] Joseph F. alludes to Sarah’s poor health in a letter to Martha Ann. See Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 13 October 1898, herein.

[34] See Brian William Sokolowsky, “Photographs of Joseph F. Smith and the Laie Plantation, Hawaii, 1899,” BYU Studies 41, no. 4 (2002): 47–63.

[35] Joseph F. Smith, in Conference Report, October 1899, 41.

[36] Gibbons, Joseph F. Smith, 203–4.

[37] Joseph F. to Joseph F. Smith Jr., 8 August 1899.

[38] Carole Call King, “History of Martha Ann Smith Harris, 1841–1923” (unpublished manuscript in editors’ possession).

[39] Ruth Mae Harris, Martha Ann, Daughter of Hyrum and Mary Fielding Smith (Orem, UT: published by the author, 2002), 137.

[40] Harris, Martha Ann, 137.

[41] Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 22 May 1890, herein.

[42] Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 25 October 1898, herein.

[43] Ruth Smith, Edna’s daughter (born 21 December 1893), died on 17 March 1898. See Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 19 March 1898, herein, note 243.

[44] Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 19 March 1898, herein.

[45] Martha Ann to William Harris, 20 November 1898, transcription in Harris, Martha Ann, 143–44. Though the letter was misdated, the envelope is clearly postmarked 22 November 1898.

[46] Mary Fielding.

[47] Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 13 March 1883, herein.

[48] Sarah Harris Passey, “Martha Ann Smith Harris,” manuscript, 7; in possession of the authors.

[49] In 1892 the Provo City Council abated Martha Ann’s city taxes because of her “indigent” state. “Taxes Remitted,” Daily Enquirer, 9 August 1892, 4. However, Martha Ann’s name continued to appear in the local newspaper for failure to pay taxes during the decade. See for example, “Delinquent Taxes,” Evening Dispatch, 5 December 1894, 3; “Delinquent Taxes,” Evening Dispatch, 7 December 1895, 2; “Delinquent Taxes,” Daily Enquirer, 15 December 1896, 5.

[50] See Martha Ann to Joseph F., 3 March 1913, herein.

[51] Interview by Mary Harris Hafen, as cited in David J. Harris and Ruth B. Harris, ed. and comp., Harris Heritage (n.p., self-published, 1977), 158–59.

[52] Harris, Martha Ann, 225.

[53] Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 2 May 1890, herein.

[54] Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 22 May 1890, herein.

[55] See Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 17 April 1890; Martha Ann to Joseph F., 29 April 1890; Joseph F. to Martha Ann; 2 May 1890; Martha Ann to Joseph F., 18 May 1890; and Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 22 May 1890, herein.

[56] Throughout their lives, Joseph F. and Martha Ann communicated with other family members at the same time they were writing each other. See, for example, Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 3 March 1870, herein; Joseph F. to William Jasper Harris, 18 March 1870; and Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 29 March 1870, herein.

[57] In the 1850s, Brigham Young began calling home-based missionaries, who would travel in pairs throughout the Utah Territory, speaking in meetings and visiting members’ homes to call them to repentance and greater levels of commitment. See Paul Edwards Damron, “Home Missionaries,” in Encyclopedia of Latter-day Saint History, ed. Arnold K. Garr, Donald Q. Cannon, and Richard O. Cowan (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2000), 508.

[58] Franklin Hill Harris to Joseph F., 23 March 1890.

[59] Joseph F. to Franklin H. Harris, 25 March 1890.

[60] Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 11 February 1891, herein.

[61] Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 11 February 1891, herein.

[62] Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 7 June 1891, herein.