Decade Introduction

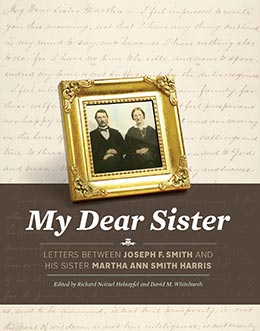

Richard Neitzel Holzapfel and David M. Whitchurch, "Decade Introduction," in My Dear Sister: Letters Between Joseph F. Smith and His Sister Martha Ann Smith Harris, ed. Richard Neitzel Holzapfel and David M. Whitchurch (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2019), 267–280.

The First Presidency with George Q. Cannon, John Taylor, and Joseph F. Smith, ca. 1880. Courtesy of CHL.

The First Presidency with George Q. Cannon, John Taylor, and Joseph F. Smith, ca. 1880. Courtesy of CHL.

The First Presidency of the Church was reorganized in the October 1880 general conference, three years after the death of Brigham Young (1801-77). Joseph F.'s notes, taken at a meeting of the Quorum of the Twelve held in the Endowment House on 9 October, simply stated: "The Twelve met at 6 p.m. in the E. H. when the motion of C. C. Rich & seconded by O. Pratt that we organize the 1st Presidency was put and carried. Then a motion of W. Woodruff John Taylor was chosen President. He then chose G. Q. C. & Joseph F. as councillors."[1]

A day later, at a historic Sunday afternoon conference session, John Taylor (1808-87) was sustained as President of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, with George Q. Cannon and Joseph F. Smith chosen as councelors in the First Presidency. [2] Joseph F. was fourty-one years old when called and would serve as a member of the presidency until his own death in 1918, thirty-eight years later.

The Campaign against the Church

Following the Church’s first public acknowledgment on 29 August 1852 that it practiced plural marriage, an increasing number of religious and political leaders in the United States began a campaign to eradicate the practice, primarily through enacting laws against it and the institutional Church that supported it.[3] The general population in the United States was firmly opposed to the practice and supported the government’s effort, which became more intense after 1884, to end it.

Between 1862 and 1887, Congress enacted four antipolygamy laws directed specifically at the Church and its members: the Morrill Act (1862), the Poland Act (1874), the Edmunds Act (1882), and the Edmunds-Tucker Act (1887). The Edmunds and Edmunds-Tucker Acts were especially detrimental to Church members because they allowed a separate crime to be charged for each day a person lived with or supported more than one wife. Additionally, the Edmunds-Tucker Act gave the federal government the added authority to disincorporate the Church, escheat its property and financial assets, and disenfranchise women voters.[4] The Edmunds-Tucker Act also made plural marriage a felony and set the punishment at six months in prison and a three-hundred-dollar fine, while simultaneously depriving anyone participating in its practice, including wives, of the right to vote. A whirlwind of prosecution was about to break out across the Latter-day Saints’ religious landscape in the western part of the United States. In 1879 the US Supreme Court had affirmed the arrest and conviction of George Reynolds (1842–1904), a secretary to the First Presidency who had originally volunteered to act as a test case regarding the extent of the “free exercise clause” of the US Constitution. He had been prosecuted for cohabitation under the 1862 Morrill Act. Basically, the court ruled that the Constitution guaranteed protection of religious belief but not religious practice. A few days after the beginning of the new year in 1879, Joseph F. had noted in his journal, “We got news that the Supreme Court had decided in the Reynolds case, against Reynolds.”[5] This short entry belies the significance of the news for fellow member George Reynolds, the Church, and its members, including Joseph F. and his family. Latter-day Saints were surprised and shocked by the decision, believing the US Constitution protected their marriage practice because it was based on their religious belief. This historic case opened the way for increased legal actions against the Church and individual members.[6]

Plural Marriage

Various studies have attempted to identify how pervasive the practice of plural marriage was in the Church during the nineteenth century. Some have examined the adult male population, which would naturally result in smaller numbers. Others have included wives and children, which would dramatically increase the numbers and therefore the percentage of participation. Whichever category one chooses to use, the percentage of Latter-day Saints involved in plural marriage apparently hit its peak during the Reformation in the 1850s.[7]

As one would suspect, the percentage of those involved in the practice changed over time and varied from community to community. However, if one counts “closest monogamous relatives—parent, sibling, married children, and in-laws—one could argue that by 1880 close to a majority of the Mormon population was directly or indirectly affected by a practice much more prevalent than generally acknowledged.”[8]

Most studies also reveal that males who participated in the practice were generally married to two wives, making Joseph F.’s situation an exception to the general rule. Already by 1880, he was married to three wives. During this decade, he married two more times. Alice Ann Kimball (1858–1946) was Joseph F.’s fourth wife, married on 6 December 1883. She was the daughter of Heber C. Kimball (1801–68), a member of the First Presidency at the time of his death and a personal associate of Joseph F.’s father, Hyrum Smith (1800–44). Joseph F. married his fifth wife, Mary Taylor Schwartz (1865–1956), the niece of John Taylor (1808–87), on 13 January 1884.

Alice Ann Kimball, ca. 1888. Courtesy of CHL. Joseph F. Smith was sealed to Alice on Thursday, 6 December 1883, in Salt Lake City. Alice had three children—Alice May (1877–1920), Heber Chase (1881–1971), and Charles Coulson (1881–1933)—from a previous marriage. These children became part of Joseph F.’s family.

Alice Ann Kimball, ca. 1888. Courtesy of CHL. Joseph F. Smith was sealed to Alice on Thursday, 6 December 1883, in Salt Lake City. Alice had three children—Alice May (1877–1920), Heber Chase (1881–1971), and Charles Coulson (1881–1933)—from a previous marriage. These children became part of Joseph F.’s family.

On the Underground or Exiled

As the government’s efforts to end plural marriage intensified, especially after 1884, Church leaders chose to go into hiding (on the “underground”) or leave Utah as exiles to avoid arrest and incarceration rather than submitting to what they considered to be unjust laws.

President John Taylor was particularly concerned with Joseph F.’s personal safety because of his position in the First Presidency and his work at the Endowment House. Both assignments gave him particular knowledge about the Church’s marriage practices, something the federal government would surely want to obtain if possible. Additionally, as noted above, Joseph F. was practicing plural marriage himself and therefore was also subject to arrest. Joseph F., attempting to lighten the mood during this challenging period, wrote to Martha Ann, “It seemes I am in some demand in certain quarters.”[9]

Joseph F. began his life on the underground on 29 August 1884, when he departed with his wife Edna Lambson (1851–1926) and one of their children on a tour through Utah, Colorado, New Mexico, and Arizona, visiting members and conducting Church business. Joseph F. had to be constantly vigilant to avoid arrest. Informers and spies were hired by government officials to locate Church leaders in order to arrest them. Apparently, movement in and out of the territory was particularly difficult. In a letter to Susa Young Gates in 1889, Joseph F. noted that he had left Utah for Washington, DC: “This makes the 4th time, in a year, that I have run the gauntlet getting out and in, the territory.”[10] He continued, “I have seen none of my family for several days— Some of my friends are very anxious to interview me— But owing to the circumstances over which I now have no control I am not anxious for the honor! I may be in stripes however by the time you get home.”[11] He would basically remain out of the public eye until September 1891, seven years later, when President Benjamin Harrison granted him amnesty.

Joseph F.’s life on the underground was often challenging. In addition to the constant fear of possible detection and arrest, he was worried about his family’s welfare. Of this experience his wife Edna wrote, “We are living at our poorest now. No butter, no meat, but imported bacon, and we women folks cannot eat that. . . . Some of us are almost starved.”[12] Additionally, the homes of Joseph F.’s wives were under constant surveillance by federal marshals and without warning they were raided.[13] At various times, Joseph F. traveled to Salt Lake City to visit his wives and children. However, with such a large family, he found it difficult to remain incognito. “I am getting quite an experience,” he wrote. “It is rather funny to try to conceal oneself at home with so many little prattlers, so happy to see their papa.”[14]

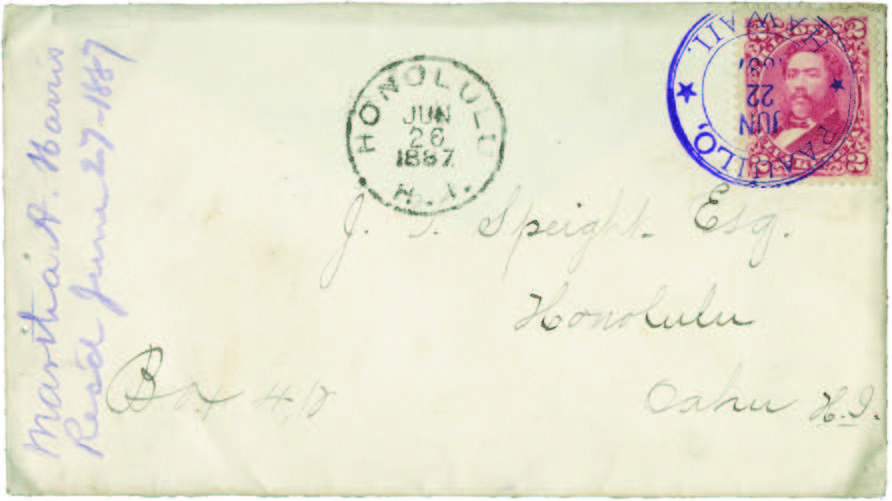

Finally, President Taylor decided that Joseph F. needed to leave Utah for a longer season and called him to return to Hawai‘i. Joseph F. and Julina Lambson (1849–1936), along with their daughter, Julina Clarissa (1884–1923),[15] departed on 2 February 1885, beginning an exile in the islands under the pseudonyms “Mr. and Mrs. Speight” (see letter envelope below).

Envelope addressed to J. S. Speight (Joseph F.’s alias). Courtesy of CHL. The first postmark (to the right) features a two-cent stamp depicting King David Kalākaua and is dated “Jun 22 1887 Paauilo, Hawaii.” The second postmark (center) is dated “26 June 1887 Honolulu H.A.” Joseph F. wrote on the envelope, “Martha A. Harris Rec’d June 27 1887,” with a purple pencil. A few days later, Joseph F. was on his way home to Utah.

Envelope addressed to J. S. Speight (Joseph F.’s alias). Courtesy of CHL. The first postmark (to the right) features a two-cent stamp depicting King David Kalākaua and is dated “Jun 22 1887 Paauilo, Hawaii.” The second postmark (center) is dated “26 June 1887 Honolulu H.A.” Joseph F. wrote on the envelope, “Martha A. Harris Rec’d June 27 1887,” with a purple pencil. A few days later, Joseph F. was on his way home to Utah.

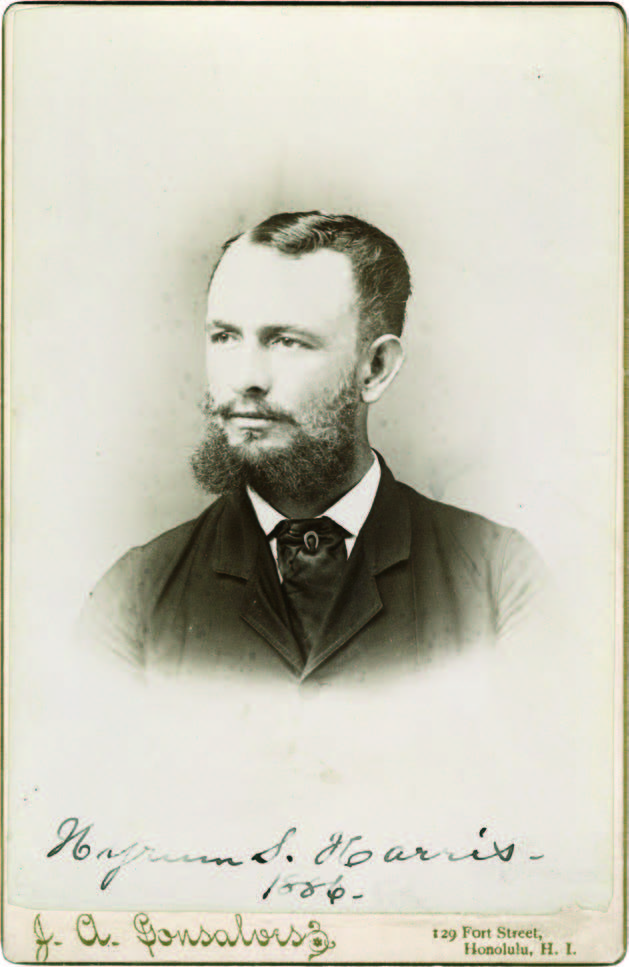

During his exile in Hawai‘i, Joseph F. was able to visit Martha Ann’s son Hyrum Smith Harris (1863–1924), who was serving a mission in the islands at the time. He wrote Martha Ann about visiting his nephew: “I arrived in these lands on Feb—9th and and the following day came out here—where I met our boy, Hyrum, looking and feeling well, and seemingly as happy as he could be so far from home, and surrounded by so many circumstances foreign to his customs of youth. He is making very good progress in the study of the language.”[16]

Hyrum Smith Harris, 1886, photograph by J. A. Gonsalves, Honolulu, Hawai‘i. Courtesy of CHL.

Hyrum Smith Harris, 1886, photograph by J. A. Gonsalves, Honolulu, Hawai‘i. Courtesy of CHL.

In January 1886 Julina, who was five months pregnant, noted in her journal, “One year this morning Since I left my home and precious children little did I think of being away from them so long oh how my heart yearns for their presence. When O when can we go home.”[17] In addition to the pain of separation, Joseph F. and Julina experienced heartache when they received word that Joseph’s son Robert (1883–86) had died in February 1886. Edna Lambson (1851–1928), his mother, was Julina’s sister, in addition to being one of her husband’s plural wives. Julina recorded:

Albert came early [from Honolulu] in the evening bringing the Sad news of little Roberts death, Joseph met him at the barn. I Stepped out of the door I cold See by their looks that Something was rong they both looked so Sad, I asked what is the matter you have brought bad news, Albert answered “Your children are all right. I thought he ment all of Josephs children, So I said is it ours Albert “no.” is it mothers “no.” it is Robert he is dead, I burst into tears. I felt that it was too hard, Oh my poor Sister Edna in her touching letter She Says. “I am So lonesome no baby to love.” Poor girl how my heartaches for her, and poor papa to See his grief seems more than I can bear. O. Lord comfort thier heart.[18]

Two weeks later, Julina finally decided to write in her journal again: “Jos has fretted So much and felt So very bad over the loss of his little Robert one of the nicest children we had, at first I thought it was no comfort to him my being hear with little Ina [Julina Clarissa], but I can now See that if he had been here along, it would have been harder, it Seems that he can not Stand it to be alone.”[19]

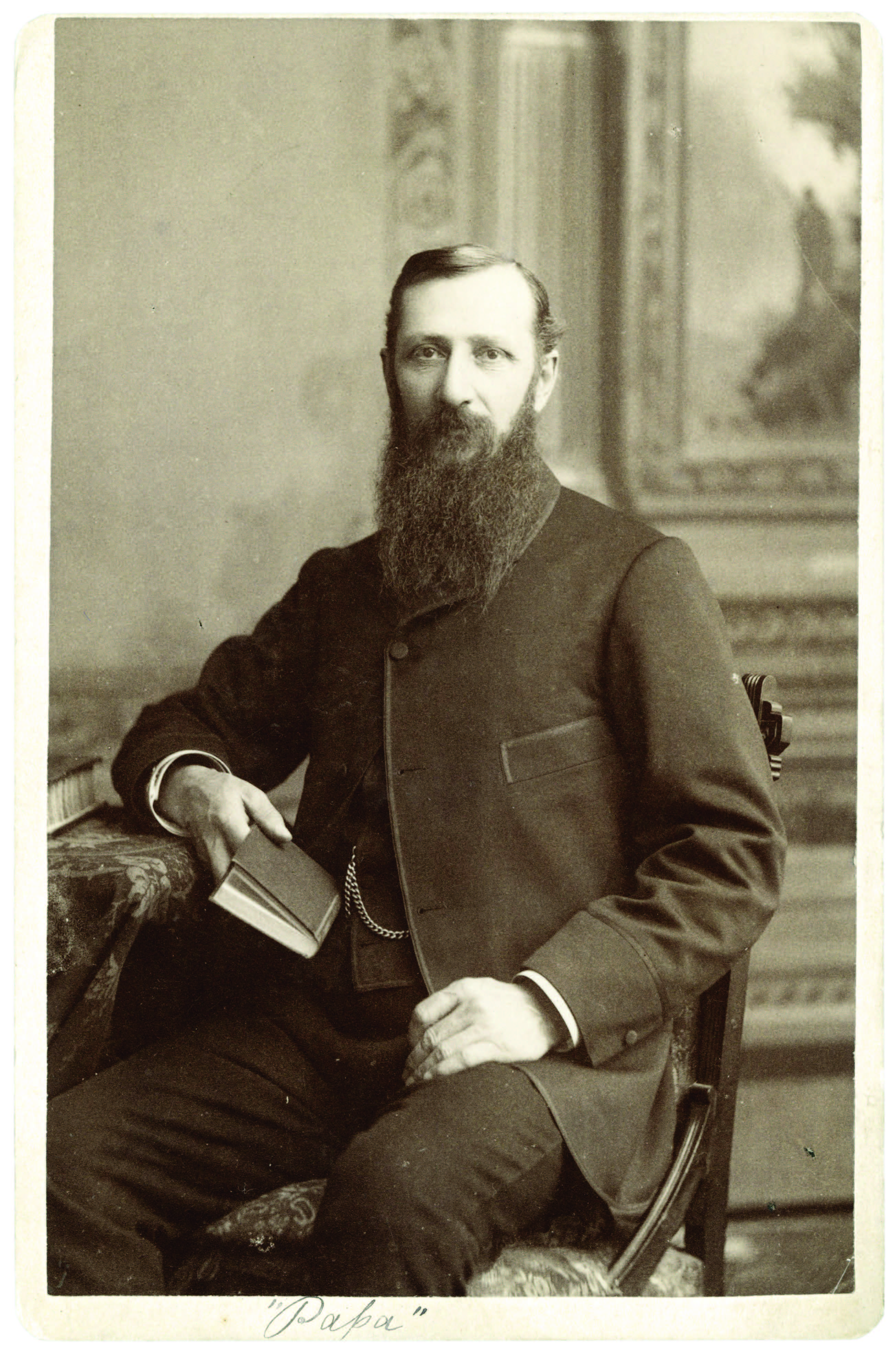

Joseph F. Smith, ca. 1884, photograph by C. R. Savage, Salt Lake City, Utah. Courtesy of CHL.

Joseph F. Smith, ca. 1884, photograph by C. R. Savage, Salt Lake City, Utah. Courtesy of CHL.

Julina delivered a baby boy, Elias Wesley Smith (1886–1970), on 21 April 1886, while in exile. Years later Wesley was called to serve a mission in Hawai‘i. In a letter dated 12 May 1907, Joseph F. told his son about some of his activities in Lā‘ie just before Wesley was born: “You mentioned helping to white wash the fences, barns, etc. at Laie. Did you realize that I helped to build the barn and carriage house, and the square 4 roomed house nearest the barn when I was there, before you were born?”[20]

In November 1886 Joseph F. became seriously ill and dangerously emaciated. Julina’s teenage daughter Donnette (1872–1961) came to the islands to take care of Joseph F. and help Julina with her baby. In March 1887, after his recovery, Joseph F. sent Julina and Donnette back to Utah. As they set sail, he wrote: “I took the last look at the receding forms of my loved and loving ones until God in his mercy shall permit us to meet again. When the ship passed the line of sight, I . . . climbed Puuoina to look again at the speeding steamer. . . . When once alone, my soul burst forth in tears and I wept their fountains dry and felt all the pangs and grief of parting with my heart’s best treasures on earth.”[21]

Lā‘ie, O‘ahu, Hawai‘i, ca. 1885. Courtesy of CHL. Joseph F. and Julina Smith lived at the Lā‘ie Church plantation on the island of O‘ahu from 1885 through 1887.

Lā‘ie, O‘ahu, Hawai‘i, ca. 1885. Courtesy of CHL. Joseph F. and Julina Smith lived at the Lā‘ie Church plantation on the island of O‘ahu from 1885 through 1887.

When Joseph F. received a letter from Martha Ann on 27 June 1887, momentous changes were under way in the Kingdom of Hawai‘i.[22] Just one day later, Walter M. Gibson[23] (1822–88) and other cabinet members in the government of King David Kalākaua (1836–91) resigned under pressure of antimonarchists who supported the annexation of Hawai‘i by the United States.[24]

According to Joseph Fielding Smith, “Joseph F. Smith said that he met Gibson several times after his excommunication from the Church [in 1864] and when he was a man of power in the Hawaiian Islands, and that he never seemed to hold a spirit of bitterness. . . . [Apparently] there were even occasions when he befriended the Saints when he exercised power as Prime-minister to King Kalakaua.”[25] It is possible that Joseph F. was personally a recipient of that kindness during his exile in Hawai‘i between 1885 and 1887.

Church Responsibilities Back Home

Joseph F. was planning to remain in Hawai‘i for a while longer, but his exile was cut short by news that Church president John Taylor was near death.[26] As a result, he sailed home on 1 July 1887 on the steamer Mariposa, a ship owned by the Oceanic Steamship Company.[27]

As soon as he was back in Utah, Joseph F. hurried to the home of Thomas F. Roueche (1833–1903) in Kaysville, Davis County, where President Taylor had been in hiding from federal officers.[28] George Q. Cannon, Joseph F.’s fellow counselor in the First Presidency, arrived shortly thereafter, on 18 July. This was the first time the First Presidency had been together since 1884.[29] President Taylor died a week later, on 25 July 1887. Due to possible arrests, only five Apostles were able to attend the public funeral.

In February 1888 Wilford Woodruff, the senior Apostle of the Quorum of the Twelve, sent Joseph F. on a brief mission to Washington, DC, to help manage Church finances, supervise the missionary effort and immigration affairs, and garner political favor for the beleaguered Latter-day Saints. Joseph F. and Charles W. Penrose (1832–1925) traveled together under the pseudonyms “Jason Mack” and “Charles Williams,” respectively. They returned to Utah in June for six months before returning to Washington, DC, again in December. This short mission ended in March 1889, when Joseph F. returned to Utah in preparation for the annual general conference of the Church.[30]

In April 1889 the First Presidency was reorganized with Wilford Woodruff as President. He called George Q. Cannon and Joseph F. Smith, who had been counselors in the previous First Presidency, to be his counselors.

Pacific Islanders in Utah

At this same time, Joseph F.’s connections with the Hawaiian Saints reemerged, but this time in Utah.[31] While serving his first mission in Hawai‘i in the 1850s, Joseph F. often mentioned Jonathan Napela (1813–79), one of the earliest Hawaiian converts in the islands.[32] Eager to receive his temple blessings, Jonathan came to Utah for a visit in 1869. During his time in Utah, he met Church leaders, attended the annual Pioneer Day celebration, spoke to local Latter-day Saint congregations, received his temple endowment, and had his photograph taken at Edward Martin’s studio in Salt Lake City.[33]

Napela’s reports to the Hawaiian Saints in the islands increased interest among many of them to make the journey to Utah to receive their own temple blessings. Within five years, small groups of Native Hawaiian Latter-day Saints began settling in Utah.

In 1888 Joseph F. noted in a letter to Wilford Woodruff, “They come to Utah believing it to be the gathering place for the Saints—the Zion of the latter days—and while they are ignorant of our language and customs and will appear awkward and dependent somewhat at first, they are naturally bright.”[34]

These Hawaiian pioneers to the Great Basin were among the first minority groups to settle in what was still a European-American dominated society. Although he had some reservations about an effort to establish a permanent presence of Hawaiian Saints in Utah, Joseph F. supported and encouraged efforts to provide Church help to these Saints and was involved in the decision to create a Church-owned joint-stock company (the Iosepa Agriculture and Stock Company) that led to the establishment of a Hawaiian gathering place in Skull Valley, about seventy-five miles southwest of Salt Lake City.[35] Named in honor of the Prophet Joseph Smith and Joseph F., Iosepa became the home of several hundred Hawaiian converts beginning in 1889.[36]

Joseph F. was pleased to see the new settlement become the gathering place for the Hawaiian Saints and continually sought to support and help the Hawaiian Saints, who he believed were members of the house of Israel through Father Lehi, mentioned in the Book of Mormon.

Counter to prevailing views of many American and European explorers, colonizers, and others at the time, Joseph F. believed the Hawaiian people “have souls to save.”[37] Joseph F. opined that “the long experience I have had upon those islands and the intimate acquaintance I formed with that people in the days of my childhood [have given me] a particular warmth of friendship in my heart towards them.”[38]

As a result of his earlier experiences in Hawai’i and his scriptural understanding, Joseph F. supported the Hawaiian Saints’ temporal and spiritual advancement through his Church assignment as a counselor in the First Presidency, letters to Church leaders in Utah and Hawai’i, and personal visits to Iosepa.[39]

Martha Ann’s Blessings and Struggles

Martha Ann and William had been married twenty-five years when their eleventh and last child was born on 8 December 1882. Sarah Lovina (1882–1961) was welcomed into the Harris home in Provo, Utah County, Utah Territory.

Joseph F. acknowledged the birth of Martha Ann’s daughter in a letter to his brother-in-law, William Jasper Harris, six days later: “Yours of the 9th inst. Containing information of your family increase on the 8th is duly received.” Joseph F. added, “I am thankful that Martha Ann and daughter are or were at your writing so well.” He then asked William Jasper if Martha Ann might be willing to “swap her girls for boys!”[40] Martha Ann’s last four babies were girls, Mercy Ann (born 30 March 1874), Zina Christine (born 13 May 1876), Martha Artimissa (born 27 June 1879), and Sarah Lovina (born 8 December 1882). Joseph F. observed and proposed, “[H]er preponderance of girls is now getting noticeable. . . . Let us have this thing put right next time. With love. Yours Truly. Joseph.”[41]

Given the infant and childhood mortality rate in the United States during the nineteenth century, it is rather remarkable that Martha Ann lost none of her children during their infancy or childhood, in stark contrast to her brother’s experience with losing young children.[42]

Sarah Lovina Harris, ca. 1883. Courtesy of Carole Call King.

Sarah Lovina Harris, ca. 1883. Courtesy of Carole Call King.

While Martha Ann celebrated Sarah Lovina’s birth, two challenges remained constant for Martha Ann: the economic struggles she experienced as she cared for a large family and her health concerns.

In a letter to his brother-in-law, William Jasper Harris, written in 1881, Joseph F. responded to a report about Martha Ann: “I am extremely sorry to hear of Martha’s continued illness. What can be done for her? If I can do anything please let me know what and I will endeavor to do it. . . . Do you need anything that I can get for you? Please let me know. We are all well. With love and prayers for Martha Ann, I am as ever Joseph F.”[43]

Nearly half of Joseph F.’s letters written to Martha Ann in the 1880s make reference to Martha Ann’s humble circumstances.[44] For example, in a letter dated 23 November 1881, he wrote:

I herewith send you an order, (No. 1497) on the Provo Woollen factory for $50.00 I send you this on condition that you will get with it such things as you may need to clothe yourself and the little children, as far as possible, for the winter. And this is all I ask. I also send you order No. 775: for $10.00 for shoes for yourself and little ones, so far as it will go. and as every little helps, if wisely used this may do you a little good in the face of the present and future cold weather.[45]

In another letter written four years later, Joseph F. lamented to his sister: “Why should my poor—dear sister and her family ever be bound down by the strong cords of poverty and want? Perhaps it is all right, but it seemes to me there is a screw loose some where. I do not think it is your fault. surely you have ever worked hard enough and have deserved better fare.”[46] This pattern of helping Martha Ann would continue not just during the 1880s but throughout the remainder of Joseph F.’s life.

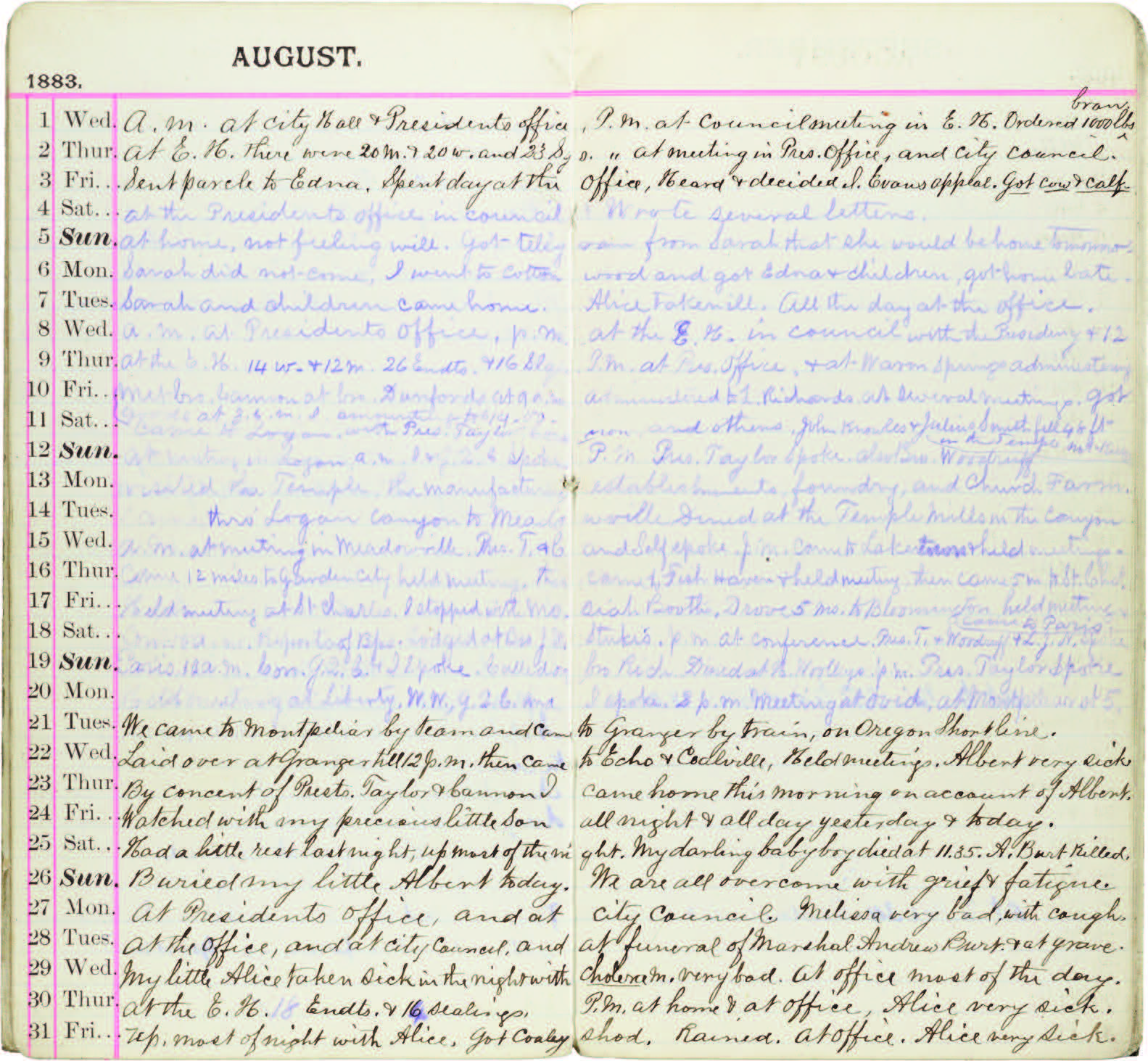

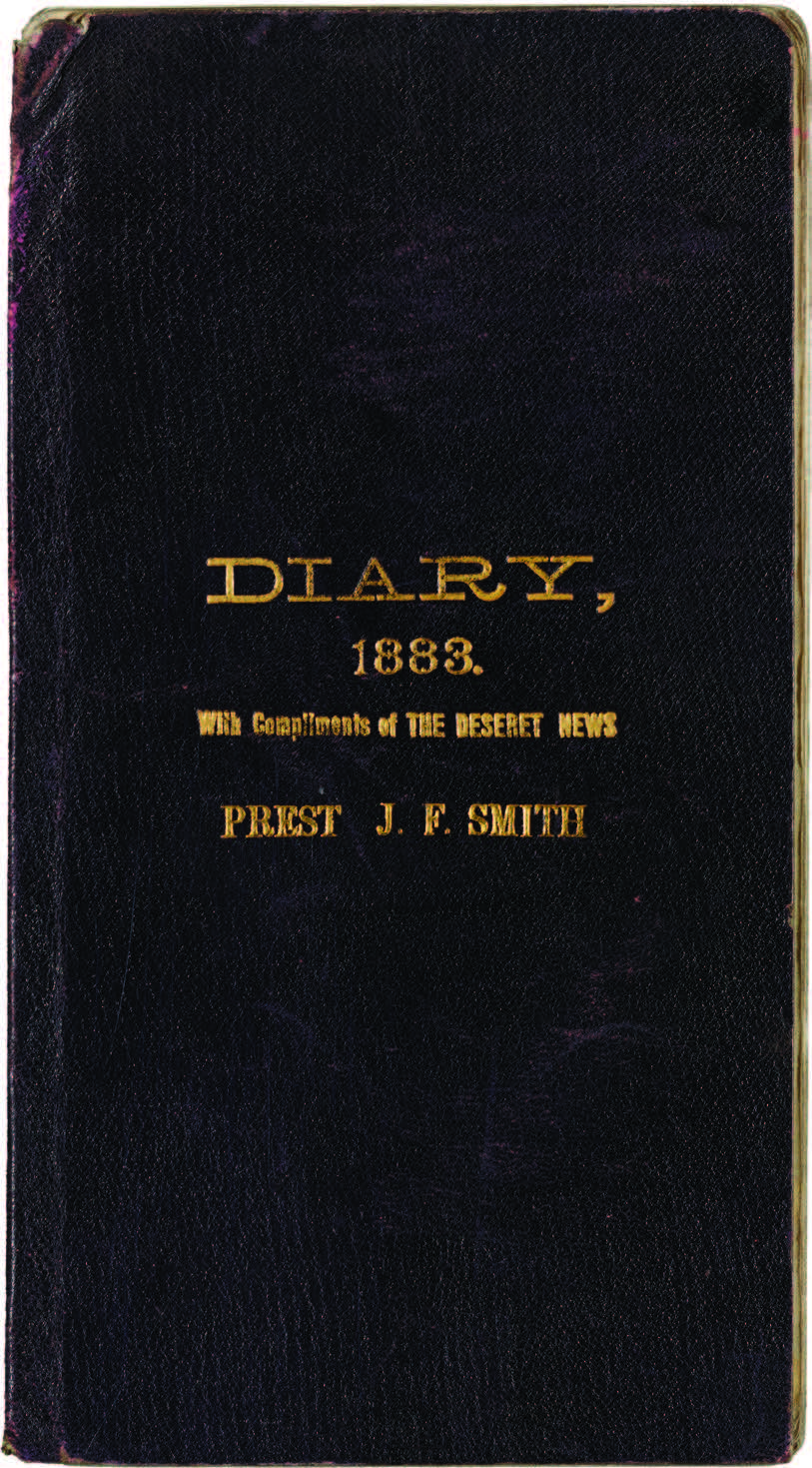

Joseph F.’s journal for August 1883. Courtesy of CHL. This 1883 journal was kept in a complimentary diary provided by the Deseret News with his name embossed in gold on the cover. This particular journal did not allow extensive writing per day, basically giving a single line across two pages for daily entries. These images highlight August 1883. Although this particular journal did not allow extensive comments, his entries for the twenty-fourth, twenty-fifth, and twenty-sixth are poignant: “Watched with my precious little Son all night & all day yesterday & today. Had a little rest last night, up most of the night. My darling baby boy died at 11.35. Buried my little Albert today. We are all overcome with greif & fatique.”

Joseph F.’s journal for August 1883. Courtesy of CHL. This 1883 journal was kept in a complimentary diary provided by the Deseret News with his name embossed in gold on the cover. This particular journal did not allow extensive writing per day, basically giving a single line across two pages for daily entries. These images highlight August 1883. Although this particular journal did not allow extensive comments, his entries for the twenty-fourth, twenty-fifth, and twenty-sixth are poignant: “Watched with my precious little Son all night & all day yesterday & today. Had a little rest last night, up most of the night. My darling baby boy died at 11.35. Buried my little Albert today. We are all overcome with greif & fatique.”

In 1881 Martha Ann wrote one of her most important letters, identified herein as “Martha Ann to her Posterity, 22 March 1881.”[47] It is an autobiographical letter reaching back to her birth in Nauvoo and covering the major events in her life, including the death of her father, leaving Nauvoo, arriving in Utah, the death of her mother, her marriage to William Jasper, his mission to England, her move to Utah County during the Utah War, her move to Provo, and an update on her membership in the Provo First Ward Relief Society.[48]

Martha Ann went on to counsel her posterity, to express gratitude for her neighbors and friends in Provo (who “have helped me in times of sickness and need”) and for a merciful Heavenly Father, and to plead that she and her family would be saved in the kingdom of heaven:

Now my dear children, never be ungrateful. Always be sure to pay your tithing, for by so doing I have, and you will, receive a great many favours and blessings. . . . I feel to sincerely thank my Heavenly Father for His mercies to me. Ingratitude is a very great sin. Through privations and hardships, my load has seemed at times more than I could shoulder, but I tried to do my duty, have tried to be a good Latter-day Saint. My Father in Heaven knows how hard it has been. He has seen my struggles, has heard and answered my prayers, that have been offered for the welfare of those I love. Though many times I have fallen short through my weakness, my desire is to do the will of the Lord and live so while I remain here on the earth to strive to keep his commandments, that at the last day He may say “Well done, my faithful handmaid.” This is the desire of my heart. I DEDICATE MYSELF AND ALL I HAVE ON THIS EARTH INTO THE HAND OF MY HEAVENLY FATHER, asking him in the name of Jesus Christ to grant me that me and my companion and my children and those I love may be saved in the Kingdom of Heaven. Even so, Amen.[49]

Towards the end of the letter she predicted, “When [her family] read this letter I shall have passed away very likely.”[50]

In addition to her own challenges, Martha Ann was also concerned with her brother’s safety during the last half of the decade. Joseph F.’s prominence in the Church leadership was one factor for concern because federal law enforcement officials targeted Church leaders—in particular Joseph F., George Q. Cannon, and John Taylor—and their families for special prosecution.

Summary

At decade’s end, fifty-one-year-old Joseph F. was supporting five families living in separate households with twenty-one living children (one had been adopted in the 1860s, and another three had been adopted when he married Alice Ann Kimball in 1883). Tragically, he buried three young children in the 1880s. Never before had family life been so complicated for him. His opportunities to visit his family when he wanted were limited because spies and law enforcement officers were monitoring his homes in an effort to arrest him.

Martha Ann was forty-eight years old at the end of the decade. She and William were the parents of eleven living children, one born in 1882. The family residence remained in Provo, Utah.

Financial hardship continued to plague Martha Ann and her family. In a letter written to Joseph F.’s wife Julina Lambson, Martha Ann mentioned her efforts to augment the family budget: “I have been busiy all the fall making gloves and taking in anything I could git to do.” In closing the letter, she wrote with some remorse, “Love to send them [her nephews and nieces] something more substantial than a kiss but they will have to take the will for the deed intill my Ship Came in.”[51]

The letters written during this decade reveal Joseph F. and Martha Ann’s deep affection and concern for each other. More tellingly, they attest to their unflinching determination to overcome obstacles in order to serve the Lord in any capacity or station in which they found themselves and to support and strengthen their cherished family relationships.

Notes

[1] Joseph F., journal, 9 October 1880.

[2] Fifty-first Semiannual General Conference, 10 October 1880; see John Taylor, “The Organization of the First Presidency, Etc.,” in Journal of Discourses, 22:38–41.

[3] Orson Pratt of the Quorum of the Twelve announced that plural marriage was an official practice of the Church. See also Deseret News, “Extra,” 4 September 1852, 15.

[4] In 1890 the US Supreme Court upheld the legality of the Edmunds-Tucker Act. See US Supreme Court, 140 US 665, Late Corporation of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints v. United States, 19 May 1890. For a recent summary, see Andrew H. Hedges and Richard Neitzel Holzapfel, eds., Within These Prison Walls: Lorenzo Snow’s Record Book, 1886–1897 (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2010). For examinations of the antipolygamy legislation, see Gustive Olof Larson, The “Americanization” of Utah for Statehood (San Marino, CA: Huntington Library, 1971); Edward Leo Lyman, Political Deliverance, The Mormon Quest for Utah Statehood (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1986); Edwin Brown Firmage and Richard Collin Mangrum, Zion in the Courts: A Legal History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1830–1900 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2001), 139; and Edwin Brown Firmage, “The Judicial Campaign against Polygamy and the Enduring Legal Questions,” BYU Studies 27, no. 3 (Summer 1987): 96.

[5] Joseph F., journal, 7 January 1879.

[6] For a brief overview of the federal campaign to end plural marriage, see Holzapfel and Hedges, Within These Prison Walls, xvii–xxvi.

[7] See Lowell C. Bennion, “Plural Marriage,” in Mapping Mormonism: An Atlas of Latter-day Saint History, ed. Brandon S. Plewe et al. (Provo, UT: BYU Press, 2012), 122.

[8] Bennion, “Plural Marriage,” 124.

[9] Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 18 March 1885, herein.

[10] Joseph F. to Susa Young Gates, 21 March 1889. To “run the gauntlet” was an English phrase that recalls a military punishment when the guilty party was forced to run between two rows of soldiers who would strike them with fists, switches, and weapons.

[11] Joseph F. to Susa Young Gates, 21 March 1889.

[12] Scott Kenney, “Joseph F. Smith,” in Presidents of the Church: Biographical Essays, ed. Leonard J. Arrington (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1986), 196–97.

[13] See Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 22 May 1885, herein.

[14] Joseph F., journal, 7 December 1884.

[15] They had left five other children at home, Mary Sophronia (born 7 October 1869), Donette (born 17 September 1872), Joseph Fielding (born 19 July 1876), David Asael (born 24 May 1879), and George Carlos (born 14 October 1881).

[16] Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 18 March 1885, herein. Julina Lambson mentions him several times in her journal; for example, see “Hyrum took Ina [Julina Clarissa] to Sunday School.” Julina Lambson, journal, 28 March 1886.

[17] Julina Lambson, journal, 29 January 1886.

[18] Julina Lambson, journal, 21 February 1886.

[19] Julina Lambson, journal, 7 March 1886.

[20] Joseph F. to E. Wesley Smith, 12 May 1907.

[21] Joseph F., journal, 15 March 1887.

[22] See Martha Ann to Joseph F., May–June 1887, herein.

[23] As discussed earlier, Gibson had arrived in the islands in 1861 as a Latter-day Saint missionary, but disturbing reports about his behavior and activity on the island of Lāna‘i (the Church’s gathering place for the Hawaiian Saints at the time) eventually reached Church headquarters in Salt Lake City, leading to his excommunication in 1864. Gibson continued to live in Hawai‘i for many years, and he was offered a position in King Kalākaua’s government as premier and minister of foreign affairs in 1882. Gibson wielded significant influence and power in Hawaiian political affairs between 1882 and 1887. See Gwynn Barrett, “Walter Murray Gibson: The Shepherd Saint of Lanai Revisited,” Utah Historical Quarterly 40, no. 2 (Spring 1972): 142–62.

[24] On 6 July 1887, a few days later, King Kalākaua signed a new constitution, known as the “Bayonet Constitution,” that curtailed his authority, disenfranchised as many as two-thirds of the formerly eligible Native Hawaiians from voting, and extended voting rights to noncitizens, including foreign residents of American and European background.

[25] Joseph Fielding Smith, The Life of Joseph F. Smith: Sixth President of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1938), 224.

[26] The Kingdom of Hawai‘i no longer existed when Joseph F. returned to the islands in 1899. It had become a US Territory in 1898 by the same forces that had brought about the constitutional changes and the downfall of Walter M. Gibson in 1887.

[27] Conway B. Sonne, Ships, Saints, and Mariners: A Maritime Encyclopedia of Mormon Migration, 1830–1890 (Salt Lake City, UT: University of Utah Press, 1987), 139.

[28] Thomas F. Roueche was a prominent citizen of Davis County, being the first mayor of Kaysville. He and John Taylor both served on the Legislative Assembly of the Territory of Utah, albeit in different years. Additionally, he was a trusted member of the Church. Andrew Jenson, LDS Biographical Encyclopedia (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1901), 1:464.

[29] Blane M. Yorgason, From Orphaned Boy to Prophet of God (Ogden: Living Scriptures, 2001), 307–8.

[30] Francis M. Gibbons, Joseph F. Smith: Patriarch and Preacher, Prophet of God (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1984), 158.

[31] For a detailed discussion, see Stephen C. Taysom’s forthcoming biography, “Like a Fiery Meteor”: The Life of Joseph F. Smith. We appreciate Taysom’s willingness to share his research for this section.

[32] For example, see Joseph F., diary, 10 February 1856. See also Fred E. Woods, “Jonathan Napela: A Noble Hawaiian Convert,” in Regional Studies in Latter-day Saint Church History: The Pacific Isles, ed. Reid L. Neilson, Steven C. Harper, Craig K. Manscill, and Mary Jane Woodger (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2008), 23–36.

[33] The image in the CHL is identified as “J. H. Napela” (written on the image itself), photograph by Edward Martin, 1869, Edward Martin portraits 1860, PH 1600, folder 3, item 4.

[34] Wilford Woodruff, journal, 16 May 1889.

[35] Now a ghost town identified with a historical marker, Iosepa was inhabited between 1889 and 1917. See Matthew Kester, Remembering Iosepa: History, Place, and Religion in the American West (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013).

[36] See Harold S. Davis, “The Iosepa Origin of Joseph F. Smith’s ‘Laie Prophecy,’” BYU

Studies 33, no. 1 (1993): 81–108.

[37] Joseph F to Wilford Woodruff, 19 May 1888.

[38] Joseph F. to Alice Smith, 13 September 1899. Nevertheless, Joseph F. lived in a culture and time when attitudes and actions did not always match the high expectations announced in Latter-day Saint scripture; see, for example, 2 Nephi 26:33.

[39] For example, see Joseph F. to Marriner W. Merrill, 20 October 1890, in which he recommends a Hawaiian couple to receive the highest temple blessings in the Church.

[40] Joseph F. to William J. Harris, 14 December 1882.

[41] Joseph F. to William J. Harris, 14 December 1882.

[42] Three grown children—Lucy Smith (died 1903), Mercy Ann (died 1905), and Joseph Albert (died 1911), ranging between twenty and fifty years of age—died before Martha Ann’s death in 1923.

[43] Joseph F. to William Jasper Harris, 5 January 1881.

[44] See Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 1 July 1881, 28 July 1881, 23 November 1881, 13 March 1883, 12 November 1883, 15 August 1884, 30 November 1885, 11 February 1887, and 11 March 1887, herein.

[45] Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 23 November 1881, herein.

[46] Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 30 November 1885, herein.

[47] Other early Latter-day Saint converts prepared similar letters at this time. For example, Helen Mar Kimball Whitney wrote a letter on 30 March 1881 to her family covering the same key themes Martha Ann does in this letter. See Jeni Broberg Holzapfel and Richard Neitzel Holzapfel, eds., A Woman’s View: Helen Mar Whitney’s Reminiscences of Early Church History (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1997), 481–87.

[48] Later in life, Martha Ann wrote another letter in which she provided recollections of her early life in Nauvoo, especially the martyrdom of her uncle Joseph Smith and her father, Hyrum Smith. See Martha Ann to Joanna Spears, 1920. Spears lived in Cookeville, Tennessee, and had provided some kindness to Martha Ann’s grandson J. C. Harris during his labors in the Southern States Mission.

[49] Martha Ann to her posterity, 22 March 1881.

[50] Martha Ann to her posterity, 22 March 1881. Helen Mar Kimball Whitney has a very similar phrase at the end of her 1881 letter: “Before [“my children”] have broken this seal the writer of these few lines will most likely have passed onto another stage of action, but I shall live until I have finished my Earthly mission and rejoice in the day of salvation & may all my loved ones enjoy these blessings is the prayer of your affectionate mother. Helen Mar Kimball Smith Whitney.” Holzapfel and Holzapfel, A Woman’s View, 487.

[51] Martha Ann to Julina Smith, 21 December 1889.