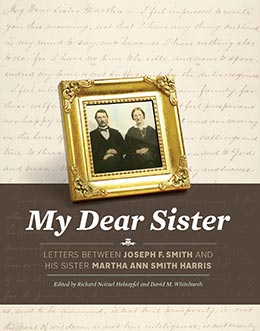

Decade Introduction

Richard Neitzel Holzapfel and David M. Whitchurch, "Decade Introduction," in My Dear Sister: Letters Between Joseph F. Smith and His Sister Martha Ann Smith Harris, ed. Richard Neitzel Holzapfel and David M. Whitchurch (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2019), 169–184.

Sarah Ellen Richards Smith and Mercy Josephine Smith, 15 August 1869, photograph by C. R. Savage, Salt Lake City, Utah. Sarah Ellen Richards, Joseph F. Smith’s plural wife, poses with Mercy Josephine, the daughter of Joseph F. Smith and Julina Lambson. Sarah Ellen Richards had lost her first and only child in February 1869, just five months earlier. Courtesy of Elaine Cannon Nichols.

Sarah Ellen Richards Smith and Mercy Josephine Smith, 15 August 1869, photograph by C. R. Savage, Salt Lake City, Utah. Sarah Ellen Richards, Joseph F. Smith’s plural wife, poses with Mercy Josephine, the daughter of Joseph F. Smith and Julina Lambson. Sarah Ellen Richards had lost her first and only child in February 1869, just five months earlier. Courtesy of Elaine Cannon Nichols.

In 1870 Joseph F. and Julina Lambson (1849–1936) suffered a devastating blow when their two-year-old, Mercy Josephine (1867–70), fell deathly ill. Joseph F. tenderly cared for his young daughter; his journal records the toll it took on him. “I have no apetite,” he wrote. “[M]y sympathy & solicitude for my darling little Josephine, has greatly bowed my spirit. . . . She is a sensitive, delicate, and tender little creature and loves her ‘papa.’”[1] On 6 June, Joseph F. attended to his duties at the Endowment House during the day, but when he returned home later that afternoon, he found that little Josephine had passed away. He was grief-stricken.

[Place image 112 here] Sarah Ellen Richards Smith and Mercy Josephine Smith, 15 August 1869, photograph by C. R. Savage, Salt Lake City, Utah. Courtesy of Elaine Cannon Nichols. Sarah Ellen Richards, Joseph F. Smith’s plural wife, poses with Mercy Josephine, the daughter of Joseph F. Smith and Julina Lambson. Sarah Ellen Richards had lost her first and only child in February 1869, just five months earlier.

In all, Joseph F. would lose thirteen children before his own death.[2] Julina noted, “He loved them all, but never got over losing [Mercy Josephine]. . . . He never got to where he could talk of his ‘Dodo’[3] without tears in his eyes.”[4] For the rest of his life, whenever his children were sick, Joseph F. could not help but worry. “I am, as you well know,” he once wrote to Julina, “almost useless when anything ails the children.”[5] Joseph F.’s letters from this decade demonstrate the depth of his grief over his children’s death, as well as his love for and devotion to the rest of his family.

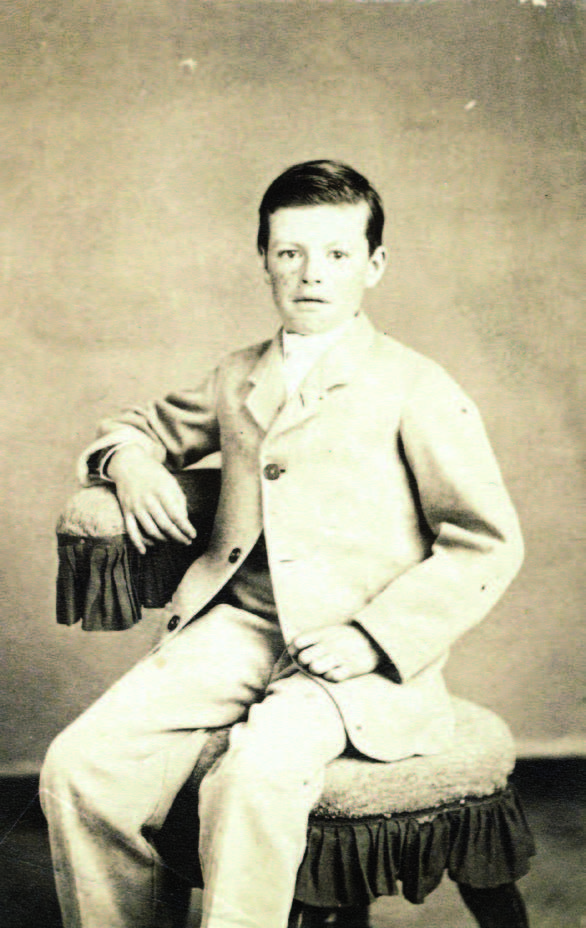

Despite such tender moments in which Joseph F. mourned the loss of a child, life continued in the Smith family, with work at the Historian’s Office and Endowment House, church meetings, family gatherings, and special celebrations. For example, in July 1870 Joseph F. noted in his diary, “Friday, July 15, 1870. at H. O. copying S. Record. Got Edward’s like ness taken at John Olsens.”[6]

Edward Arthur Smith, 15 July 1870. Courtesy of Wilburta Moore. See Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 27 February 1871, herein. Courtesy of Wilburta Moore

Edward Arthur Smith, 15 July 1870. Courtesy of Wilburta Moore. See Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 27 February 1871, herein. Courtesy of Wilburta Moore

Edward Arthur Smith (1858–1911) was the adopted son of Joseph F., who found him in England without family or support. It was a special day for Joseph F. and Julina to have Edward’s likeness taken to record and celebrate the life of a young child.

On the first day of the following year, Julina accompanied her husband and her younger sister, Edna (1851–1926), to the Endowment House on the northwest corner of the Temple Block in Salt Lake City on Sunday, 1 January 1871. There, in the structure built for sacred ordinances, she witnessed Joseph F. and Edna’s marriage sealing. There were now three sister wives and three children living in a house not far from the Historian’s Office and Temple Block.[7]

At the end of his journal for 1871, Joseph F. listed the things for which he was grateful but made one last observation: “I have buried two little girls.”[8]

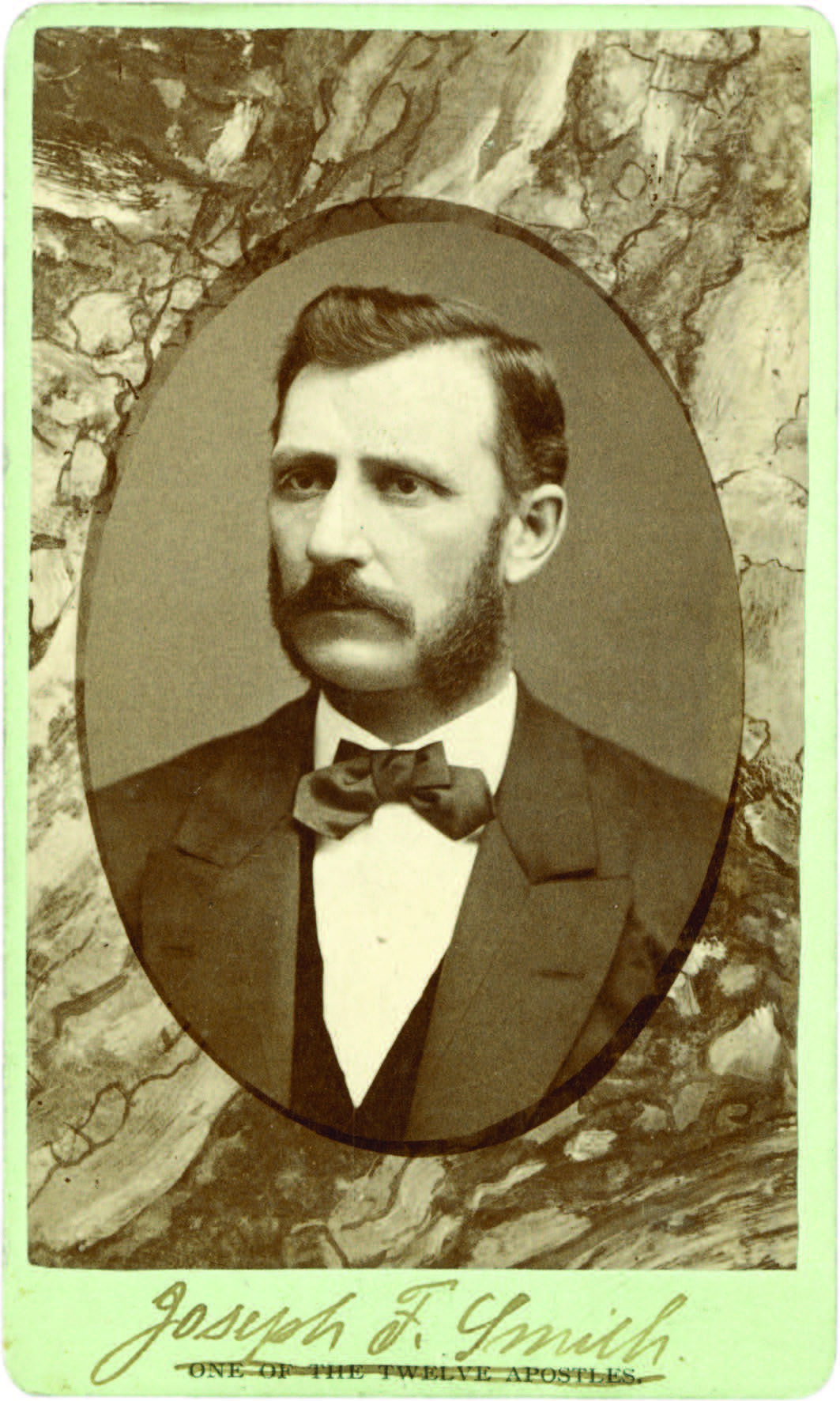

Joseph F.’s Second European Mission

In the 1873 October general conference, Joseph F. was called to preside over the European Mission, which included Great Britain, Holland, Germany, Scandinavia, and Switzerland. At the time he was only one year short of a five-year commitment that would secure him nearly 160 acres of farmland.[9] Leaving for the mission meant forfeiting his claim, but he did not object. “I felt that I was engaged in a bigger work than securing 160 acres of land,” he said. “I went as I was called, and God sustained and blessed me in it.”[10] Additionally, his call also temporarily ended his career in the territorial legislatures, which had begun in 1865.[11]

Joseph F. Smith shortly before his departure to England, ca. 1873, photograph by Charles Carter, Salt Lake City, Utah. Courtesy of CHL.

Joseph F. Smith shortly before his departure to England, ca. 1873, photograph by Charles Carter, Salt Lake City, Utah. Courtesy of CHL.

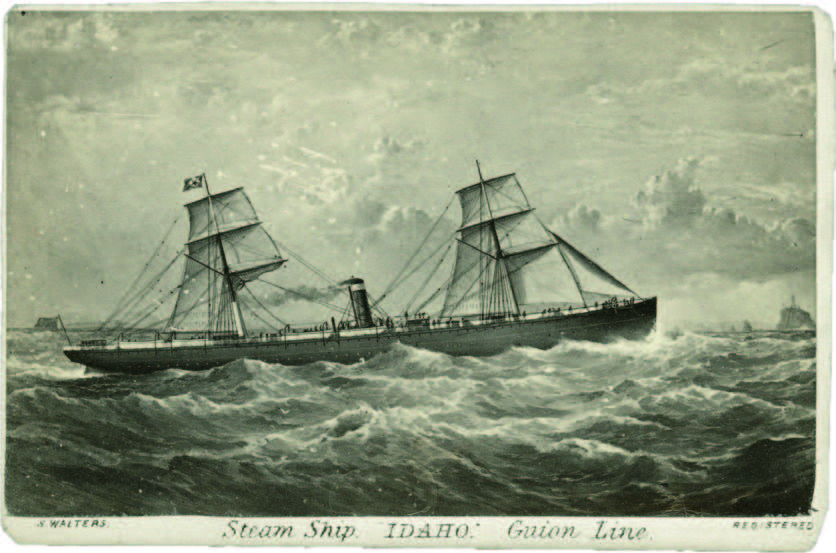

Joseph F. departed Salt Lake City on 28 February 1874, leaving three wives—Julina, Sarah Ellen, and Edna—and seven children behind. Edna was pregnant. En route he stopped in Washington, DC, and visited George Q. Cannon for two days. During his stay, Cannon took him to “the White House, and called on & shook hands with President U. S. Grant.”[12] Joseph F. also visited the War Department, Treasury, Patent Office, Capitol, and Washington Monument. Joseph F. continued his journey to New York City, where he boarded the steamship Idaho and sailed to England.

Joseph F. Smith, 27 May 1874, Lauritz Olsen, Kjøbenhavn (Copenhagen), Demark. Courtesy of CHL.

Joseph F. Smith, 27 May 1874, Lauritz Olsen, Kjøbenhavn (Copenhagen), Demark. Courtesy of CHL.

“Steam Ship Idaho, Guion Line.”

“Steam Ship Idaho, Guion Line.”

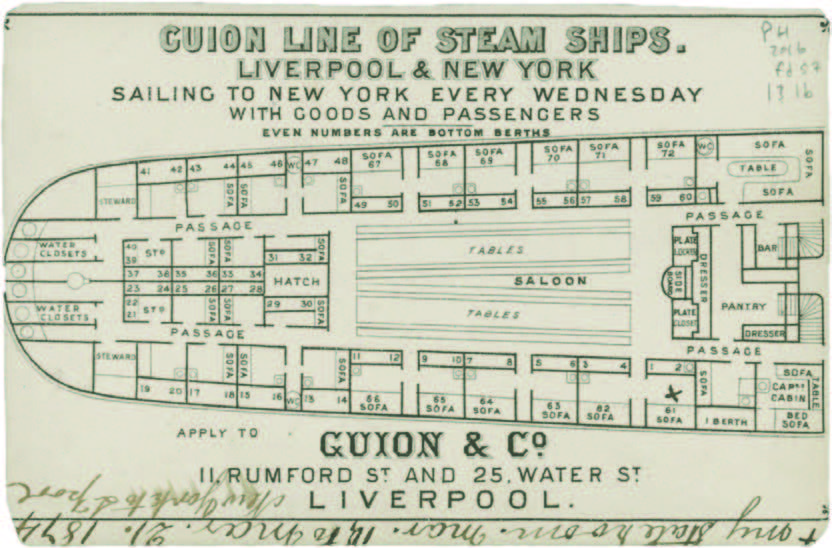

“Guion Line of Steam Ships.” Courtesy of CHL. Joseph F. noted in his journal on 10 March 1874, “Came to Peir 46. At the foot of Huston ST. N. River. And came on board the Idaho . . . set sail for Liverpool.” Joseph F. identified where he stayed during his voyage to England: “My State room. Mar. 10, to Mar. 21. 1874 New York to L. pool.” He placed an X on stateroom sixty-one.

“Guion Line of Steam Ships.” Courtesy of CHL. Joseph F. noted in his journal on 10 March 1874, “Came to Peir 46. At the foot of Huston ST. N. River. And came on board the Idaho . . . set sail for Liverpool.” Joseph F. identified where he stayed during his voyage to England: “My State room. Mar. 10, to Mar. 21. 1874 New York to L. pool.” He placed an X on stateroom sixty-one.

When his ship came into port on 21 March 1874, he reported, “bros. John C. Graham & Geo. F. Gibbs met me on board and ascorted [escorted] me to 42,”[13] the British Mission headquarters. He had traveled 2,740 miles by train and 3,050 miles by ship to get to his assignment. Although thirty-five-year-old Joseph F. had held significant positions on previous missions, this assignment would be his first major administrative position.

When he arrived, Joseph F. faced a number of challenges in Europe. First, there were only a handful of missionaries to help administer the work.[14] Second, he was responsible for the Church’s massive and highly successful emigration efforts.[15] Finally, he served as editor of the Millennial Star, the Church’s oldest continuous English-language publication.[16]

During this second mission, Joseph F. expressed concern about the poverty he confronted in England. In a letter to his sister, he observed, “I cannot bear to see suffering and poverty, I see sights which grieves me every time I go out in the streets.”[17] The never-ending demands of his important assignment and Liverpool’s dreary weather often made him miss his family and home in Utah.[18] In addition to writing letters, when time and circumstance allowed, he sent packages containing small gifts to his family with returning missionaries.[19]

During this mission, he had what he termed “one of the most memorable days of my life.”[20] He recounted: “I have traveled in the world for twenty years, meeting and passing through all classes of people. I am now over 35 years of age. Today for the first time in my life I was robbed of £17.10 by a gang of thieves between Liverpool and Crewe.[21] No man can know my mortification, Shame, and chagrin. I blame nobody so much as myself. I was caught off my guard, but I am all most stifflied with Shame. . . . This day let me not forget.”[22] On this mission Joseph F. had additional photographs taken as well. In one case he noted, “I am in excellent health as you will see by my Photo, which I inclose, it is the last one of a dozzen I had taken while in Denmark.”[23]

After nearly twenty months of service in Europe, Joseph F. learned that fellow Apostle George A. Smith (1817–75), his father’s cousin, had died in Utah. Joseph F. had worked with Elder Smith in the Historian’s Office since 1865. Additionally, George A. had become a father to Joseph F. and was his closest friend among the Apostles.[24] Shortly after receiving this news, Joseph F. was released from his missionary service and made his return home.[25]

After his arrival home from England, Joseph F. was assigned to preside over the Davis County Stake, an ecclesiastical area north of Salt Lake City.[26] This made him directly responsible for both the spiritual and the economic well-being of the Saints throughout the county. With the completion of the First Transcontinental Railroad in 1869, Utah witnessed a large influx of non–Latter-day Saints—changing forever the economic, social, and religious landscape there.[27]

Brigham Young responded to these challenges with a well-directed program encouraging self-sufficiency that included an all-out effort for the Saints to grow their own crops and produce their own goods, all to be sold through Church-established wholesale trading businesses like the Zion’s Cooperative Mercantile Institution.[28] Joseph F. was made president of the Davis County Cooperative, one of the many institutions established during this period to assist the Saints in remaining economically independent. He served in this capacity for the next year and a half.[29] He also continued working at the Historian’s Office and Endowment House in Salt Lake City.

Third European Mission and Death of Brigham Young

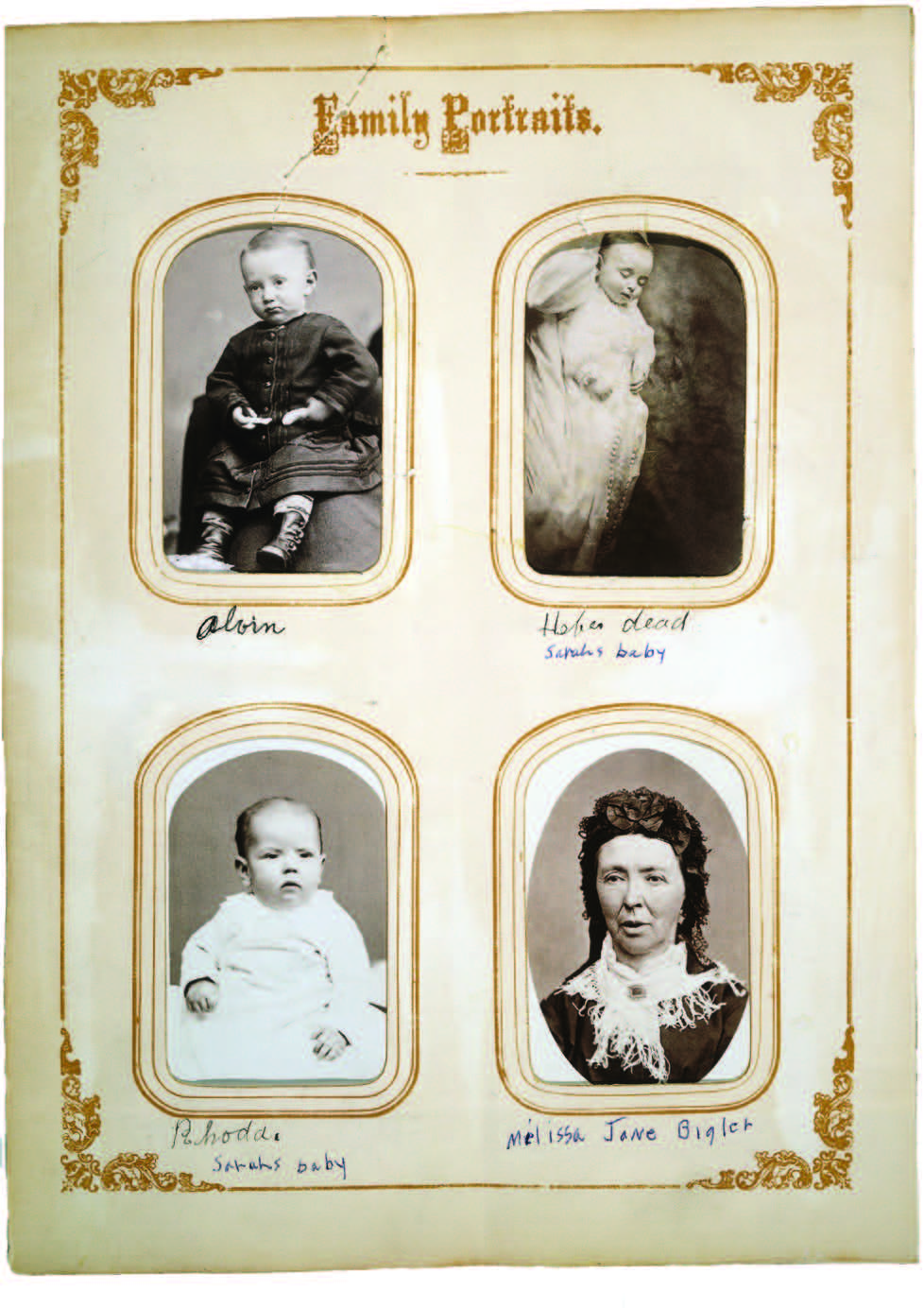

Just a few weeks before the April 1877 general conference, Joseph F. lost another child—Heber John (1876–77), the son of Sarah Ellen Richards. He was less than a year old at the time of his death on 3 March 1877. Since no photograph had been taken before he died, the family chose to remember him by having his photograph taken following his death; this type of photograph, known as a postmortem photograph or memorial portraiture, was popular in the nineteenth century.

Heber John’s postmortem photograph, 3 March 1877. Courtesy of Mary Lou Walker.

Heber John’s postmortem photograph, 3 March 1877. Courtesy of Mary Lou Walker.

At the April 1877 general conference, which coincided with the dedication of the St. George Temple in southern Utah, Joseph F. was once again called to preside over the European Mission. This would be his fifth international mission.[30] Because this assignment was expected to last for several years, Joseph F. took Sarah Ellen[31] and their four-year-old son Joseph Richards (1873–1954) with him, leaving Julina, Edna, and eight children in Utah.[32]

Just three months after his arrival, Joseph F. received word that Brigham Young had died on 29 August 1877, cutting short this mission. He immediately made the necessary arrangements so that he and his family could return to Utah. Once in Salt Lake City, Joseph F. took on a more active leadership role in the general affairs of the Church, including responding to the increasing government pressure against plural marriage, settling Brigham Young’s complicated estate, and tackling various other assignments as a member of the presiding Council of the Twelve until the First Presidency could be reorganized.[33]

Church History Mission

In the summer of 1878, Joseph F. was asked to accompany fellow Apostle Orson Pratt (1811–81) on a brief Church history mission to the eastern United States to gather information that would be helpful in completing a history of the early Church. Pratt had been appointed Church historian in place of John Taylor (1808–87). Now senior Apostle following the death of Brigham Young in 1877, Taylor had assigned Elders Pratt and Smith to this unusual Church mission. On their journey east, Pratt and Smith visited sites associated with the early history of the Restoration (1820–44), including Independence in Jackson County, Missouri, where they met with several members of the RLDS Church and with Latter-day Saints who had not moved to Utah. After visiting William E. McLellin (1806–83), one of the original members of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles,[34] Joseph F. reflected, “I never saw the sad effects of apostasy more plainly manifested.”[35] Despite this disappointment, Joseph F. began a friendly correspondence with McLellin, maintaining it until McLellin’s death.[36]

Following up on information provided by William McLellin, the Apostles traveled to Richmond in Ray County, Missouri, where they met with David Whitmer (1805–88), one of the Three Witnesses of the Book of Mormon. Although Whitmer had been excommunicated from the Church in 1838, he maintained faith in the founding revelations of the Restoration and in his testimony and witness of the Book of Mormon (his testimony is still published in current editions of the Book of Mormon). Joseph F. reported that David Whitmer “bore to us his usual strong and undeviating testimony to the truth of the Book of Mormon. . . . Nothing could be more earnest, more sincere, than that aged man’s solemn affirmation that he saw the angel and heard his voice declaring that the characters upon those plates were divinely translated.”[37]

After making numerous stops throughout Missouri, Elders Smith and Pratt went on to various cities in Illinois to visit members of the Smith family. They then traveled to Kirtland, Lake County, Ohio, the site of the first Latter-day Saint temple; Palmyra, Wayne County, New York, the site where the Book of Mormon was first printed; and New York City. On their return trip, Joseph F. visited Joseph Smith III in Plano, Kendall County, Illinois, the headquarters for the RLDS Church. During this visit, Joseph F. asked to see the manuscript of Joseph Smith’s translation of the Bible (JST). Although denied access to the manuscript, he was presented with a published copy of the translation, known as the Inspired Version, released in 1867.

Elders Smith and Pratt returned to Salt Lake City in time for the October 1878 general conference. Once back at home, Joseph F. continued his busy schedule with family, work, and Church responsibilities.

On 6 July 1879, Joseph F. witnessed another death in his family—his daughter Rhoda Ann. He wrote Martha Ann the following day: “It has become my painful duty to inform you, that we have this day laid away—in the great city of the dead upon the hill—another of my precious little pets.”[38]

As he dealt with that tragedy, Joseph F. faced continued opposition in the local press, primarily in the Salt Lake Tribune.[39] He noted in his journal in August 1879, “p.m. at meting in the Large Tabernacle. The congregation was large & many Strangers being present. . . . I followed 45 minutes. And had very good liberty. . . . For once I think I have spoken in the Tabernacle and have given the Anti-Mormon papers nothing to say.”[40]

One of the earliest public attacks occurred earlier in the decade when he was a member of the Salt Lake City Council. The Salt Lake Tribune described Joseph F. as having “a bad temper and worse taste . . . a bitter and narrow minded fanatic . . . [whose] affectation of superiority and sometimes positive insolence” rendered him “most unworthy” of a place on the city council.[41] During the following year in 1873, the Salt Lake Tribune published Joseph F.’s likeness as a woodcut with a caption that read, “Elder Joseph F. Smith, how he appears in his sublunary state, the champion of the Church and the opponent of free speech, the man whose zeal outruns his discretion.”[42]

These public attacks in the 1870s were some of the mildest of Joseph F.’s life. Unfortunately, in the decades ahead, Joseph F. was the specific target of the local, national, and international press in ways that John Taylor, Wilford Woodruff, and Lorenzo Snow never experienced.

Martha Ann’s Perseverance

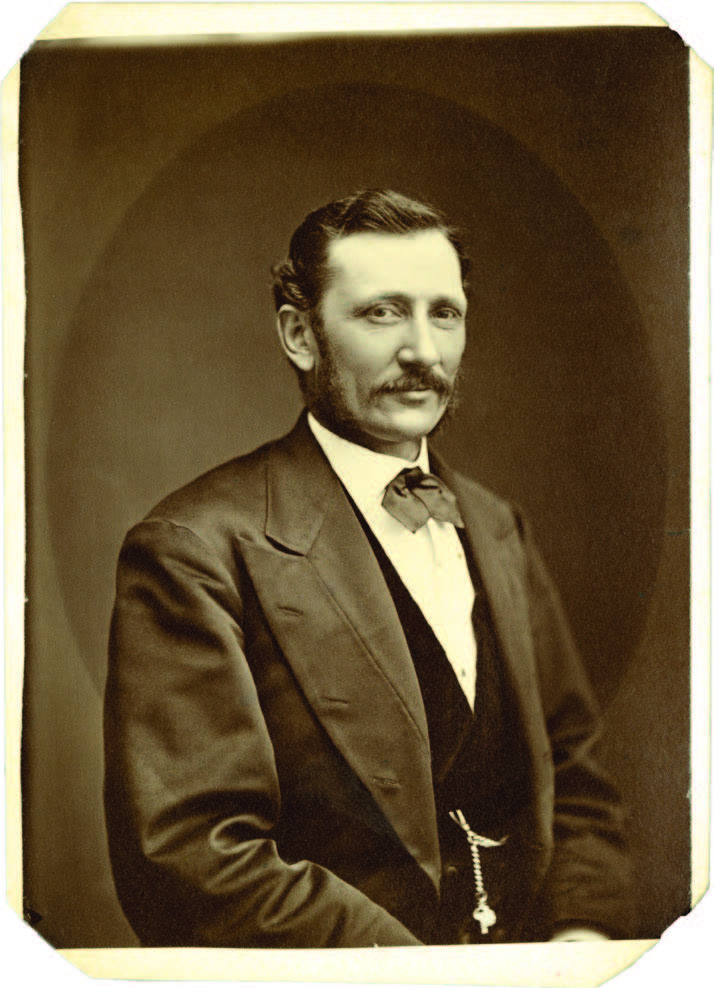

Martha Ann continued to dedicate her life to her growing family. The 1870 US Census reached their neighborhood on 12 August 1870. Martha Ann and William Jasper were living in the Provo First Ward at the time.[43] The family consisted of eight members: William Jasper, age thirty-two; Martha Ann, twenty-nine; William Jasper Jr., twelve; Joseph Albert, nine; Hyrum Smith, six; Mary Emily, four; Franklin Hill, two; and Lucy Smith, two months old. Martha’s occupation was listed as “Keeping House.”[44]

Four more children were born to Martha Ann and William Jasper after the 1870 census was completed: Lucy Smith Harris (1870–1903), John Fielding Harris (1872–1946), Mercy Ann Harris (1874–1905), Zina Christine Harris (1876–1958), and Martha Artimissa Harris (1879–1961).

Martha Ann continued to face financial challenges during this decade. Joseph F. in the fall of 1879 wrote, “My sister is in very straitened circumstance. Her husband is unthrifty.”[45] A few weeks later, he noted after a personal visit, “[Martha Ann] is in very low circumstance, but in good health.”[46] To help provide for her growing family, Martha Ann continued to make gloves and also sewed temple clothing used in Latter-day Saint temple worship and burial practice. She became a known authority on temple aprons, producing about six per week and sending them to the Relief Society Burial Clothes Department in Salt Lake City.[47] She also often helped with the dressing of deceased members in their temple clothing. Because many of her aprons were intended for burial, she would quip with her daughters that most of her work was “underground.”[48] Granddaughter Edna Mae Simmons (1899–1986) recalled: “Grandmother worked her fingers to the bone. She’d sit and embroider temple aprons all day long until she could hardly stand it. I think she used glasses to embroider with. . . . Grandmother would sit in her chair and embroider temple aprons. . . . Some of the aprons had each green leaf embroidered and appliquéd onto white satin. . . . Grandmother made beautiful temple robes, too. She worked very hard pleating the robes in fine linen. Linen was a fabric she loved.”[49] Martha Ann earned $1.50 for each apron and would continue this work to the end of her life.

Like many other nineteenth-century Latter-day Saint pioneers, Martha Ann lived in modest and humble circumstances throughout much of her life. There were critical moments in Provo when Martha Ann and her family were in desperate need of help. For example, in a letter written in 1874 to George A. Smith, Joseph F. asked for assistance to help his sister and her family: “I am sorry to say that William Harris is in a very bad fix. On Friday last he had five fits from 5 am to 7 pm. His family and friends thought he would never survive them. He is now perfectly helpless and dependent on charity. The family is destitute of necessaries. Smoot can supply them. Can Tithing Office send provisions, boots, shoes for children?”[50]

In a tender letter to his sister written in 1874, Joseph F. commended Martha Ann for her perseverance and compared her to their saintly mother, who had become, within the Latter-day Saint community, a singular example of faith and dedication: “[I]ndeed, yours has been a thorny path in this world, as mothers was, your patience and endurance are almost if not quite equal to hers.”[51] In response she wrote: “I have had so much to contend with first on one side and then on the other one would say why do you put up whith what you do I would not. and other sais you are a fool and so on I could not tell you half I have had to contend with it is very easy to talk but not so easy to perform I feel like leaving it all in the hands of the Lord and when he sees I have born enough he will ease my burdon and all will come out right in the end if I do my dutey in all things & bare all things with so with paciense which I hope I may bee inabled to do. the Lord has been good to me.”[52]

The primary sources support the family traditions that Martha Ann spent long hours day after day, week after week, month after month, and year after year, sewing or mending items to use or to give away or to sell, including gloves, burial clothing, and temple aprons.[53]

Martha Ann found time to serve her family, friends, and neighbors despite her own physical hardships. In June 1871, for example, while suffering with boils and a toothache, she went to Salt Lake City to assist Joseph F.’s wife Sarah in childbirth. While she was away, Martha Ann’s thoughts frequently turned toward home and her own family. In a letter to William, she wrote instructions to keep the boys out of the water, “for that will make them Sick.”[54] On another occasion Sarah was left weak and ill after her baby died, and Martha Ann traveled to Salt Lake City to help her recover. During her absence from home, she confessed in a letter to William, “I cannot stay away from [the children] mutch longer I want to see my little Frank so bad I can hardly stand it.”[55]

Provo Train Station, ca. 1878, C. R. Savage, Salt Lake City, Utah. Courtesy of BYU. Martha Ann and Joseph F. took advantage of the train connection between Salt Lake City and Provo as soon as that line was in operation. Joseph F. refers to the station in Utah County in letters and his diary.

Provo Train Station, ca. 1878, C. R. Savage, Salt Lake City, Utah. Courtesy of BYU. Martha Ann and Joseph F. took advantage of the train connection between Salt Lake City and Provo as soon as that line was in operation. Joseph F. refers to the station in Utah County in letters and his diary.

Martha Ann’s New Home

A few years after Martha Ann was born in 1841, her family abandoned their home in Nauvoo when residents in Hancock County forced them to evacuate the city in 1846. During the next several years, Martha Ann and her family lived as pioneers as they made their way to Utah, eventually arriving there in 1848. The first winter in the valley, they continued living in the wagons that had brought them to the Great Basin. Finally, in 1850, the Smith family moved into a small adobe home they hoped would become a permanent dwelling place.

However, as noted earlier, the death of Martha Ann’s mother in 1852 and her brother’s call to a mission in 1854 brought about another period of instability, with Martha Ann moving from house to house. Her rootlessness continued when she married William Jasper Harris in 1857, when William Jasper left on a mission, and when the Saints moved south during the Utah War.

Returning to Salt Lake City in 1858, Martha Ann met her husband, who was returning from his mission in England, at the Point of the Mountain. Reunited, they began to raise a family in Salt Lake City. In 1861 Martha Ann wrote her brother, “I am gitting tierd of renting houses for it is like throwing mo<n>ey away we will try to bye us a place the next time.”[56] Within a short time, William Jasper and Martha Ann bought a house very near Joseph F.’s home in Salt Lake City.[57]

In the spring of 1868, Martha Ann and her husband, along with their five children, moved again. This time they relocated to Provo, about forty-five miles south of Salt Lake City, and moved into a small adobe house located on lot 6, block 41. The lot was in the name of A. O. Smoot, her stepfather-in-law. We do not know the arrangement made between Smoot and William Jasper and Martha Ann for the house, but they did not have title to it during this period.

William Jasper and Martha had six more children while living in this humble home over the next fourteen years: Lucy Smith (born in 1870), John Fielding (1872), Mercy Ann (1874), Zina Christine (1876), Martha Artimissa (1879), and Sarah Lovina (1882). Granddaughter Edna Mae Hedquist (1899–1986) recalled that the “south door never did have any steps to it.”[58] As one would expect, there was no indoor plumbing.

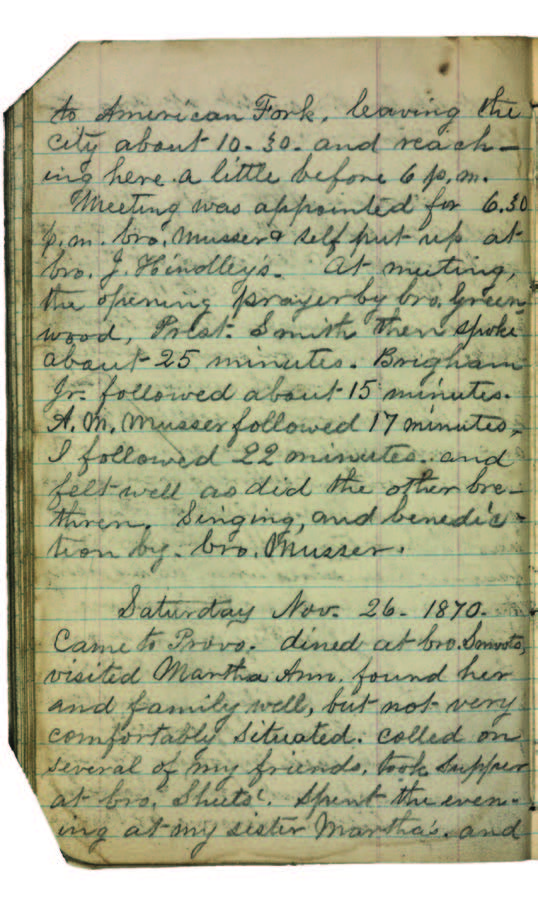

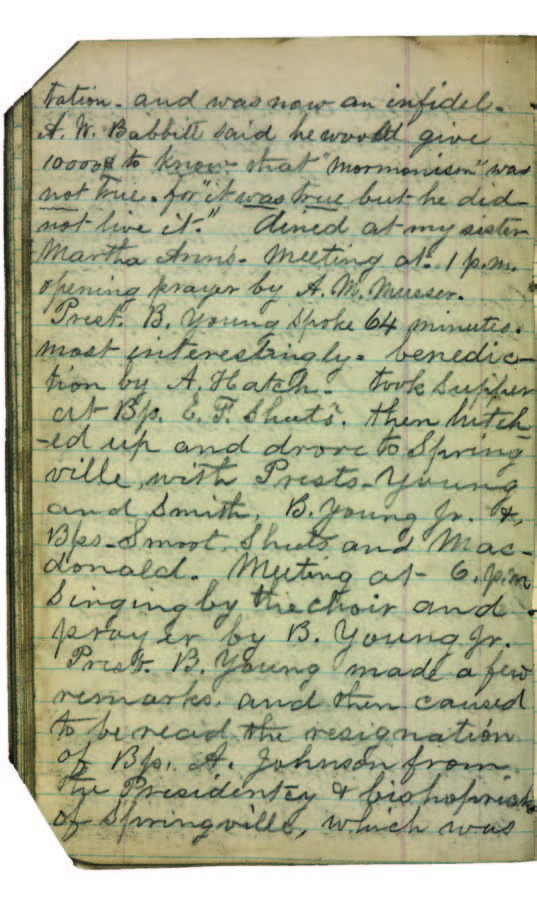

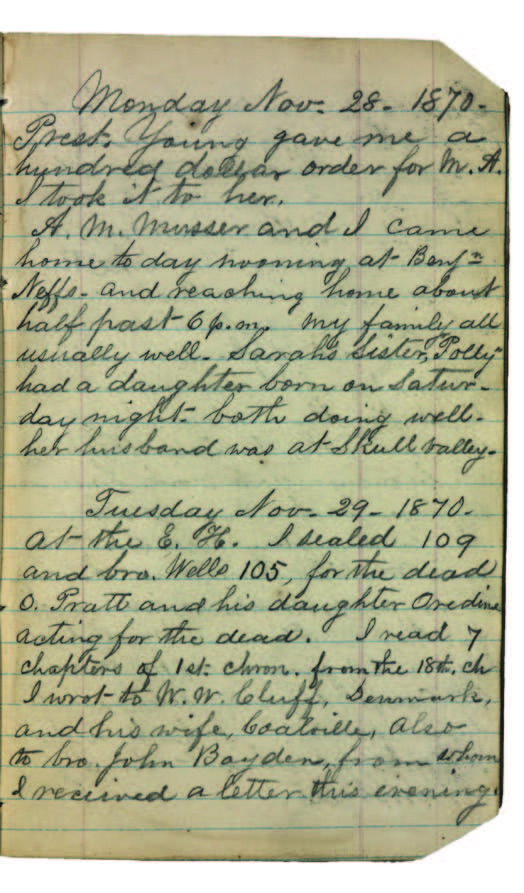

Joseph F.’s journal entries, dated 26, 27, and 28 November 1870. Courtesy of CHL. In separate entries covering three days when he visited Provo, Utah, on Church assignment with President Brigham Young, Joseph F. mentions being with Martha Ann, her economic challenges, Brigham Young’s desire to provide her a permanent home, and Brigham Young’s gift of one hundred dollars to help her.

Joseph F.’s journal entries, dated 26, 27, and 28 November 1870. Courtesy of CHL. In separate entries covering three days when he visited Provo, Utah, on Church assignment with President Brigham Young, Joseph F. mentions being with Martha Ann, her economic challenges, Brigham Young’s desire to provide her a permanent home, and Brigham Young’s gift of one hundred dollars to help her.

Joseph F. wrote Martha Ann in December 1870, “Has the Bishop done any thing about a house for you? let me know.”[59] Four months later he wrote, “bro. Dusenberry, told me he was living near you, & that he thought you were intending to move again. I enquired if you had succeeded in getting a better place, but he did not know. I am fearful that you do not have sufficient air in that little tucked up place, which may be the cause of your ill health.”[60] In May 1871 Joseph F. lamented and advised, “I wish you had a comfortable home. You had better take the deed of the place, if you can get no better one, and then try to enlarge your dwelling or build anew when ever you can. or if <you> should have it to exchange for or towords another and better place it would not be amiss.”[61]

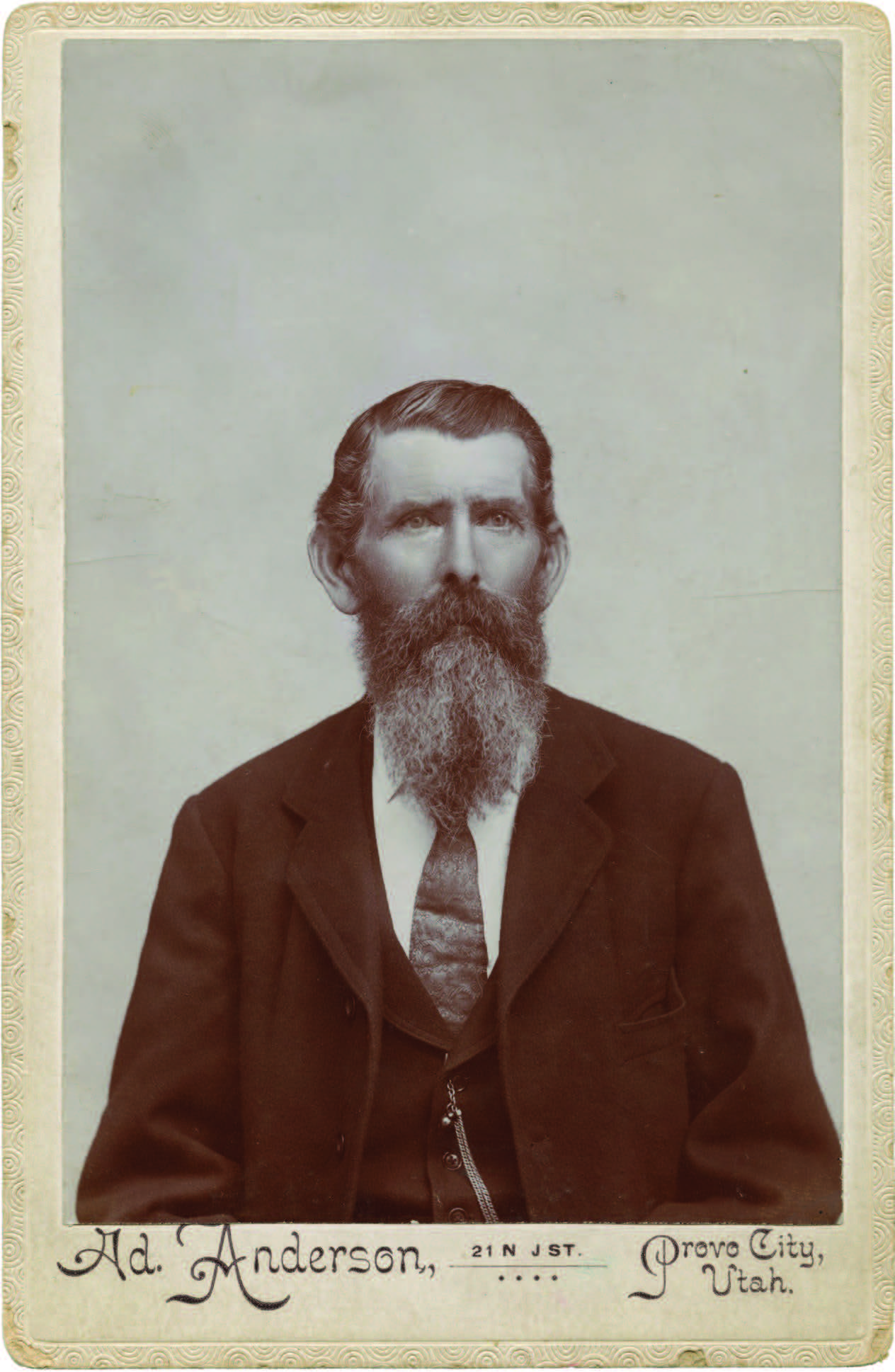

William Jasper Harris, ca. 1876, photograph by Ad. Anderson, Provo, Utah. Courtesy of Carole Call King.

William Jasper Harris, ca. 1876, photograph by Ad. Anderson, Provo, Utah. Courtesy of Carole Call King.

For many Utah residents, land ownership was problematic until 1870.[62] In June 1870 A. O. Smoot, Provo City mayor, purchased about 2,240 acres for approximately twenty-eight hundred dollars.[63] Later that month, Smoot was deeded the land “In trust” for the residents by President Ulysses S. Grant (1822–85).[64]

In 1872, when A. O. Smoot divided lots in Provo, the lot where Martha Ann was living was transferred to Brigham Young.[65] Following Brigham Young’s death, Joseph F. helped get the property transferred from Brigham Young’s estate to Martha Ann.[66] In the spring of 1878, Martha Ann was deeded a three-quarter-acre parcel identified as lot 6 in block 41 of plat A of the Provo City Survey of Utah County, Utah Territory, owned by Brigham Young according to his will.[67]

Personal Visits

As in other decades, Martha Ann and Joseph F. communicated not only through letters in the 1870s but also in person and through family members. For example, in March of 1879 Joseph F. noted, “William J. Harris came in from Provo and put up with us for the night.”[68] Ten days later he noted, “W.m. J. Harris and his son Willie and teams with us since Saturday night.”[69]

At the end of the month, Joseph F. made his way to Provo. “I took the 7 a.m. to Provo. . . . Afternoon and evening I visited “Aunt” Hanna & family . . . and my sister Martha Ann and family [were there] . . . took dinner at Pres. Smoots. Supper at Martha Anns & put up at Aunt Lucys. I bought 25c worth of candy for Marthas children. Her little Mercy will be 5 years old tomorrow.”[70] On the following day, Joseph F. recorded, “I dined at Joseph A. Harris with Aunt Zina Young. Zine & M. J. Thompson, & my sister & family. Took the train at 2.2-0pm for home.”[71]

After Joseph F. arrived home from Provo, Martha was not far from his mind. He mentioned, “I brought a “dress pattern” and trimmings for my sister Martha A. Harris. I paid $4.00 for the same.”[72]

When in October 1879 Joseph F.’s wife Edna Lambson delivered a baby, named Edna Melissa, Martha Ann came to Salt Lake City to help. She remained until the ninth.[73] In November 1879 Joseph F. was back in Utah County on assignment to speak at the Utah Stake Conference in Provo. Joseph F. recorded, “Sarah and I took supper at my sisters Martha Anns” and, on the following day, “Dined at Sister Emily Smoots. Joseph A. Harris & wife, & baby were with us. Martha Ann also came in with W. Harris.”[74]

Summary

At the end of the decade, Joseph F. was forty-one years old, married to three wives (he and Edna Lambson had been sealed in 1871), and the father to eleven living children. He buried four children during the 1870s: Julina’s daughter, Mercy Josephine (1870); Sarah’s son, Heber John (1877); Edna’s son, Alfred Jason (1878); and Sarah’s daughter, Rhoda Ann (1879).[75] In 1879 Martha Ann was thirty-eight years old and married to William J. Harris. They were the parents of ten living children, five of whom had been born during this decade. The Harris family continued to reside in Provo, Utah County, Utah.

Although in the 1870s the quality of life was changing drastically in the settlements along the Wasatch Front, Provo and Salt Lake City’s financial underpinnings were still highly dependent on the barter system. In a real sense, pioneering continued during the 1870s.[76] Martha Ann and Joseph F. were living in two worlds—the declining years of the pioneer period and the advent of premodern urbanization. However, each was experiencing this transformation in Utah rather differently.

The 1870s were full of challenges and opportunities for Joseph F. and Martha Ann. Both experienced sorrow at the loss of children and close friends and extended family members. Joseph F. once again spent time away from his family as he fulfilled the increasing demands of Church responsibilities. His travels away from home during this decade totaled nearly three years, taking him to Europe on two occasions and to the eastern United States on a special Church history assignment. For Martha Ann, the 1870s were a time of caring for her family and dealing with increased health and economic challenges in a more limited sphere than her brother’s.[77]

Notes

[1] Joseph F., journal, 5 June 1870.

[2] See appendix A, “Joseph F. Smith’s Family.”

[3] Dodo was Joseph F.’s pet name for his daughter Mercy Josephine Smith.

[4] Julina Lambson, journal, 1912, as cited in Joseph Fielding Smith, The Life of Joseph F. Smith: Sixth President of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1938), 458–59.

[5] Joseph F. to Julina Lambson, 2 April 1888.

[6] Joseph F., journal, 15 July 1870. The “H.O.” was the Historian’s Office where Joseph F. worked. That day he was most likely copying the sealings performed in the Endowment House in what he identified as the “S. Record” book.

[7] Julina Lambson (married 5 May 1866), Sarah Ellen Richards (married 1 March 1868), and Edna Lambson (married 1 January 1871).

[8] Joseph F., journal, 31 December 1871.

[9] This was part of the 1862 Homestead Act in which Congress granted land to homesteaders virtually free of charge if they improved it and occupied it for five years. According to the National Park Service, there were 16,798 homesteads in Utah, or about 7 percent of the total territorial land area; see https://

[10] Joseph F. Smith, “Discourse,” Deseret Weekly News, 2 May 1896, 2–3.

[11] Joseph F. served again in the 1880 and 1882 session and was the council president in 1882.

[12] Joseph F., journal, 7 March 1874.

[13] Joseph F., journal, 21 March 1874. The notation “42” was the affectionate nickname for the Church’s headquarters at 42 Islington Street in Liverpool.

[14] See Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 15 July 1874, herein.

[15] See Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 7 September 1874, herein.

[16] Blane M. Yorgason, From Orphaned Boy to Prophet of God (Ogden: Living Scriptures, 2001), 266. The Latter-day Saints’ Millennial Star began publication in 1840 and was suspended in 1970, when the Ensign magazine became the English-language publication for the entire Church.

[17] Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 15 July 1874, herein.

[18] Francis M. Gibbons, Joseph F. Smith: Patriarch and Preacher, Prophet of God (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1984), 98.

[19] See Martha Ann to Joseph F., 24 November 1874, herein.

[20] Joseph F., journal, 15 May 1874.

[21] Crewe was a railway town in Cheshire, England, that included an important locomotive works.

[22] Joseph F., journal, 15 May 1874.

[23] Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 15 July 1874, herein.

[24] Yorgason, From Orphaned Boy to Prophet of God, 270; Gibbons, Joseph F. Smith, 104.

[25] Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 15 July 1874, herein.

[26] Located in Davis County, Utah, the Davis Stake was an important early Church unit.

[27] For additional readings into the economic circumstances of the Saints during the 1870s, see Leonard J. Arrington, Great Basin Kingdom: An Economic History of the Latter-day Saints, 1830–1900 (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2005), 234–56.

[28] For more information on the United Order, see Arrington, Great Basin Kingdom, 327–41.

[29] Yorgason, From Orphaned Boy to Prophet of God, 270; see also Martha Ann to Joseph F., 31 May 1874, herein.

[30] The previous four missions were to the Sandwich Islands (1854–58), Great Britain (1860–63), the Sandwich Islands again (1864–65), and the British Isles and Europe (1874–75).

[31] Sarah Ellen Smith was twenty-six years old and was set apart by Brigham Young on 7 May 1877. She returned home on 27 September 1877.

[32] Son Joseph Fielding Smith suggested that Joseph F. may have chosen to bring Sarah since Julina had a young baby at the time and Sarah had just been through the death of her young child; he may have thought the trip would help take her mind off the recent tragic events.

[33] Gibbons, Joseph F. Smith, 111–12.

[34] See Reid L. Neilson and Mitchell K. Schaefer, “Excavating Early Mormon History: The 1878 History Fact-Finding Mission of Apostles Joseph F. Smith and Orson Pratt,” in Joseph F. Smith: Reflections on the Man and His Times, ed. Craig K. Manscill et al. (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2013), 359–78.

[35] Joseph F. Smith, “Reminiscences by the First Presidency: My Missions,” Deseret News, 21 December 1901, 57.

[36] See Jan Shipps and John W. Welch, eds., The Journals of William E. McLellin, 1831–1836 (Provo, Utah: BYU Studies, 1994), 353–55.

[37] Smith, “My Missions.”

[38] Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 7 July 1879, herein.

[39] Richard Neitzel Holzapfel and R. Q. Shupe, Joseph F. Smith: Portrait of a Prophet (Salt Lake City, UT: Bookcraft, 2000), 1–9, 143–47. We thank Stephen C. Taysom for the specific Tribune references mentioned in this section.

[40] Joseph F., journal, 31 August 1879. Reports of his sermons often appeared in the press, including the Salt Lake Tribune. In 1882, for example, the Tribune described him as a “natural ruffian and outlaw whose fanaticism leads him to distort all the images in the world’s kaleidoscope, and to imagine that [all] others are robbers and rogues.” See “The Conference,” Salt Lake Tribune, 5 October 1882, 2.

[41] “Our City Council and the Public,” Salt Lake Tribune, 2 August 1872, 2.

[42] “Elder Joseph F. Smith,” Salt Lake Tribune, 28 September 1873, 4.

[43] When the Provo First Ward boundary changed in April 1902, Martha Ann and her family became members of the Provo Sixth Ward.

[44] 1870 US Census, Provo City First Ward, Utah County, Utah Territory, 8.

[45] Joseph F., journal, 13 October 1879.

[46] Joseph F., journal, 29 November 1879.

[47] Many decades after Martha Ann’s death, polygamist break-off groups began claiming that she was involved in the transmission of knowledge about the “revealed pattern” of temple clothing. According to one version of this story, Emma Smith crossed the Mississippi River in 1846 to where Mary Fielding’s family was camped after their exodus from Nauvoo and handed Mary Fielding a package and said, “You will have more use of these than I; they are the original garments cut out by the two Angels and given to Joseph.” The temple clothing was eventually handed down to Martha Ann Smith. Later, before her death, Martha Ann met with Minnie Ellen Raymond (born on 5 September 1874 in Black Rivers Falls, Wisconsin) and Joseph F. Smith to pass along the full history of temple clothing and the original garments to Minnie. In this greatly expanded version of the story, a divine messenger commanded Minnie to make one hundred temple robes and garments following the exact pattern Martha Ann had given her and then took the original clothing that had been passed to her by Martha Ann. The story of a “revealed pattern” of temple clothing is late and continued to develop over time. There are no primary sources, including any documentation from Minnie before her death on 21 August 1946 or in the Harris family tradition to substantiate even the earliest versions of the story as told by Lorin C. Woolley beginning in the late 1930s and recorded by Joseph W. Musser. See Drew Briney, ed., Joseph W. Musser’s Book of Remembrance (Salt Lake City, UT: Hindsight Publications, 2010), 187–92. Minnie died an active member of the Church and was described an “an ardent temple, genealogist and Relief Society worker and had served as home missionary in the Liberty LDS Stake. At one time she was a former member of the Tabernacle Choir.” See “Obituaries,” Salt Lake Telegram, 21 August 1946, 17.

[48] Ruth Mae Harris, Martha Ann, Daughter of Hyrum and Mary Fielding Smith (Orem, UT: published by the author, 2002), 136.

[49] Harris, Martha Ann, 135–36.

[50] Joseph F. to George A. Smith, 26 January 1874, CHL; see Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 27 February 1874, herein.

[51] Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 5 August 1874, herein.

[52] Martha Ann to Joseph F., 15 August 1874, herein.

[53] See, for example, Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 15 July 1915 and 20 March 1916, herein.

[54] Martha Ann to William Jasper Harris, 23 June 1871, in Harris, Martha Ann, 143.

[55] Martha Ann to William Jasper Harris, 23 June 1871, in Harris, Martha Ann, 142.

[56] See Martha Ann to Joseph F., 12 March 1861, herein.

[57] Martha Ann to Joseph F., 30 May 1861, herein. See also G. Owens, comp., Salt Lake City Directory, Including Business Directory, Provo, Springville, and Ogden, Utah Territory (Salt Lake City, UT: G. Owens, 1867), 61.

[58] David J. Harris and Ruth B. Harris, ed. and comp., Harris Heritage (n.p.: self-published, 1977), 157.

[59] Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 7 December 1870, herein.

[60] Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 21 Apr. 1871, herein.

[61] Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 26 May 1871, herein.

[62] See Thomas G. Alexander, “Conflict and Fraud: Utah Public Land Surveys in the 1850s, the Subsequent Investigation, and Problems with the Land Disposal System,” Utah Historical Quarterly 80, no. 2 (Spring 2012): 108–31.

[63] Utah County Abstract Company, entry 1, 1 June 1870.

[64] Utah County Abstract Company, entry 2, 20 June 1872, Certificate 141.

[65] August 1872, transfer of mortgage deed of lot 6, block 41 (214 S. 300 W.) from A. O. Smoot to Brigham Young, Utah County Deed Record, Book B, p. 376, Utah County Administration Building, Recorders Office, Provo, Utah.

[66] See Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 22 April 1878, herein.

[67] Utah County Abstract Company, entry 6, 25 April 1878.

[68] Joseph F., journal, 7 March 1879.

[69] Joseph F., journal, 17 March 1879.

[70] Joseph F., journal, 29 March 1879.

[71] Joseph F., journal, 30 March 1879.

[72] Joseph F., journal, 3 April 1879.

[73] See Joseph F., journal, 6 October 1879 and 9 October 1879.

[74] Joseph F., journal, 29 and 30 November 1879.

[75] Joseph F. had buried Sarah’s daughter Sarah Ella in 1869, so by 1879 he had buried five children.

[76] Ronald W. Walker and Doris Dant, eds., Nearly Everything Imaginable: The Everyday Life of Utah’s Mormon Pioneers (Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Press, 1999).

[77] Additional letters written during this decade have not survived. For example, in 1870 alone Joseph F. noted several nonextant letters from Martha Ann in his diary. He mentioned in August 1870, “I got letters from Aunt Thompson & Martha Ann” (Joseph F., journal, 23 August 1870). In a letter written in September 1870 he noted, “Received a letter from Martha Ann went to the Drug Stowre and got two porous plasters for her hoping they may do her good” (Joseph F., journal, 22 September 1870). He recorded in October 1870, “I wrote to John Boyden, and to Martha Ann this evening having recived a letter from her this morning” (Joseph F., journal, 27 October 1870). In December 1870 he recorded, “I received a letter from Martha Ann which had been advertised” (Joseph F., journal, 7 December 1870). A final example comes from December 1870: “a.m. at H. O. received letters from W. W. Cluff—and Martha Ann. Wrote to William” (Joseph F., journal, 16 December 1870).