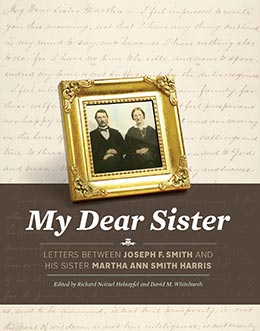

Decade Introduction

Richard Neitzel Holzapfel and David M. Whitchurch, "Decade Introduction," in My Dear Sister: Letters Between Joseph F. Smith and His Sister Martha Ann Smith Harris, ed. Richard Neitzel Holzapfel and David M. Whitchurch (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2019), 3–22.

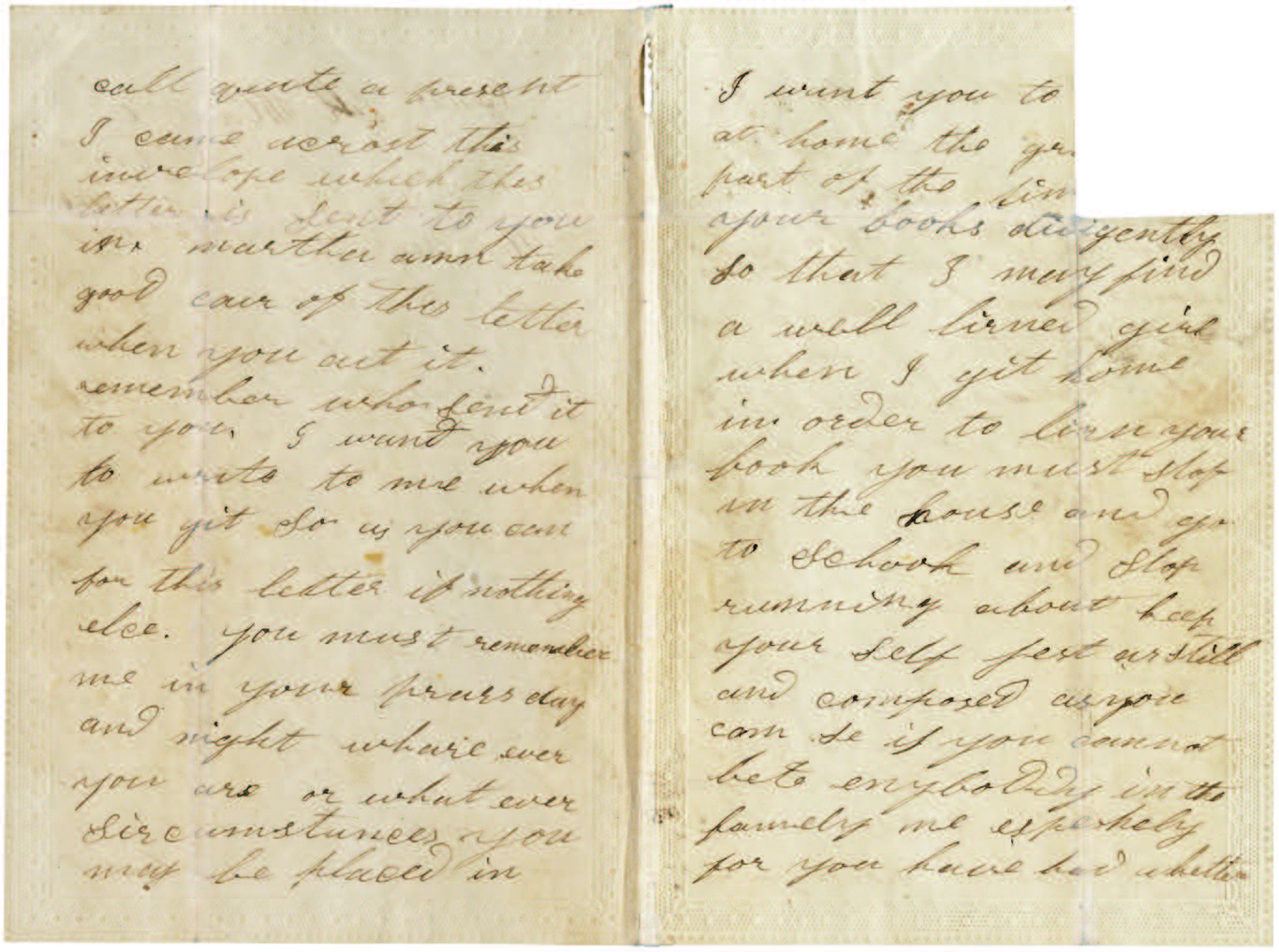

Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 14 July 1856

Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 14 July 1856

Mary Fielding Smith raised Joseph F. and Martha Ann by herself following Hyrum’s death in 1844. The influence of the Fielding family on Martha Ann and Joseph F. eclipsed the Smith family’s influence once Mary Fielding crossed the Mississippi River to Iowa in 1846—leaving most of the extended Smith family members, including a beloved grandmother, Lucy Mack Smith, in Illinois.

Shortly after Mary and her family arrived in the Salt Lake Valley, they traded the hardships of overland travel for those associated with establishing what they hoped would be their first permanent home. The summer cricket[1] infestations of early pioneer Utah, for example, devasted crop yields, making the winters of 1849–50 and 1850–51 deplorable for the settlers. Nevertheless, Mary and her family worked hard and endured. By 1850 they had completed a two-room, 14' x 22' adobe home on a forty-acre farm located about six miles southeast of Salt Lake City.[2] The year 1852 seemed to be a year of promise for the Smith household, including Joseph F. and his sister Martha Ann.[3]

William Jasper and Martha Ann Smith Harris, ca. 1857. Courtesy of Carole Call King.

William Jasper and Martha Ann Smith Harris, ca. 1857. Courtesy of Carole Call King.

Formative Events in Joseph F.’s Life

Between 12 May and 21 September 1852, a brief period of less than five months, Joseph F. experienced three important events that shaped his future experience in ways no one could have anticipated, including himself. The first occurred when President Heber C. Kimball (1801–68), a family friend and member of the Church’s First Presidency, baptized him in City Creek on 12 May. He recalled:

I felt in my soul that if I had sinned—and surely I was not without sin—that it had been forgiven me; that I was indeed cleansed from sin; my heart was touched, and I felt that I would not injure the smallest insect beneath my feet. I felt as if I wanted to do good everywhere to everybody and to everything. I felt a newness of life, a newness of desire to do that which was right. There was not one particle of desire for evil left in my soul. I was but a little boy, it is true, when I was baptized; but this was the influence that came upon me, and I know that it was from God, and was and ever has been a living witness to me of my acceptance of the Lord.[4]

Mary Fielding Smith’s home, circa 1910. Courtesy of CHL. Joseph F. Smith, John Henry Smith, and other family members at the Smith family homestead in the Sugar House area of Salt Lake City. The home was originally located at 2818 South Highland Drive, the southwest corner of 27th South and Highland Drive, before being moved to its present location at the This Is the Place Heritage Park in Salt Lake City. On the back of the photo mount is a description given in Joseph F. Smith’s handwriting: “The old home of Mary Fielding Smith, widow of Hyrum Smith, where she and family settled in the early Spring of 1849: They having arrived in Salt Lake Valley Sept. 23rd 1848. And wintered on Mill Creek during the winter of 1848–9. Joseph F. Smith.”

Mary Fielding Smith’s home, circa 1910. Courtesy of CHL. Joseph F. Smith, John Henry Smith, and other family members at the Smith family homestead in the Sugar House area of Salt Lake City. The home was originally located at 2818 South Highland Drive, the southwest corner of 27th South and Highland Drive, before being moved to its present location at the This Is the Place Heritage Park in Salt Lake City. On the back of the photo mount is a description given in Joseph F. Smith’s handwriting: “The old home of Mary Fielding Smith, widow of Hyrum Smith, where she and family settled in the early Spring of 1849: They having arrived in Salt Lake Valley Sept. 23rd 1848. And wintered on Mill Creek during the winter of 1848–9. Joseph F. Smith.”

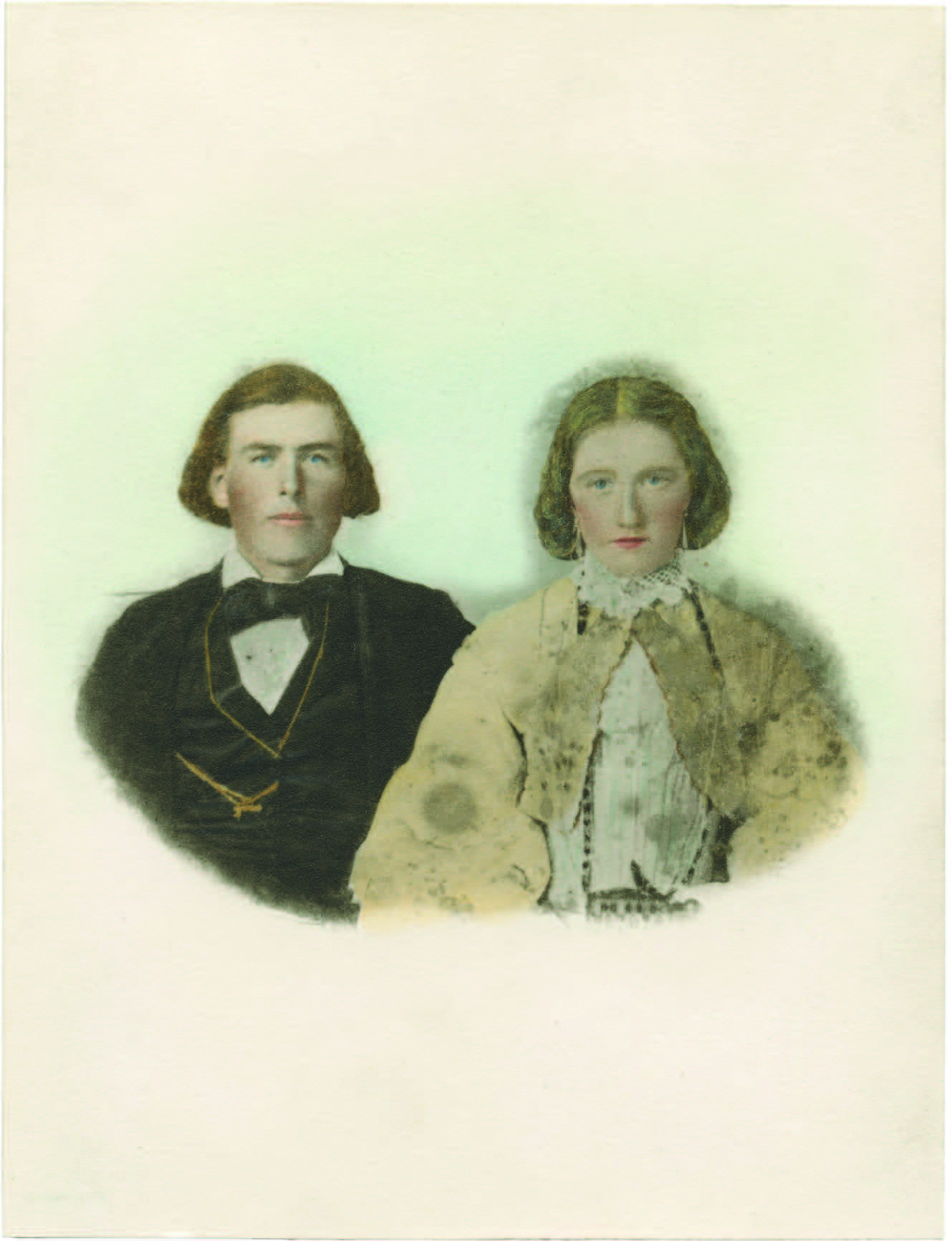

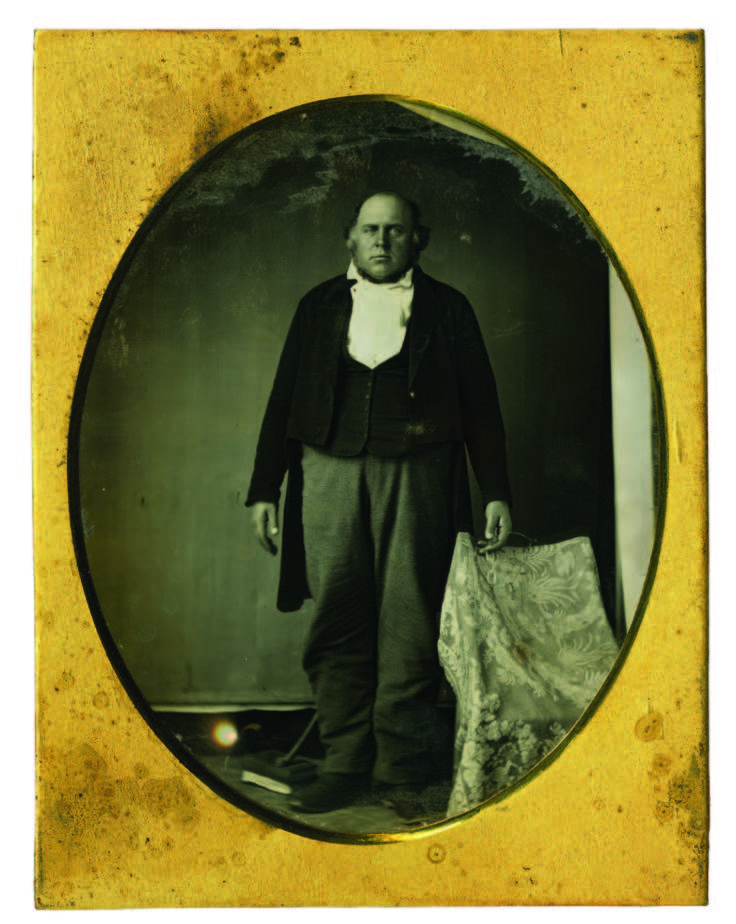

The second event occurred when John Smith (1781–1854), his father’s uncle and the Church Patriarch, gave him a patriarchal blessing on 25 June, just over a month after his baptism. Uncle John placed his hands on his head and began, “Brother Joseph in the name of Jesus of Nazareth . . .”[5] As the aged Patriarch spoke during the next few moments, Joseph F. learned about himself and his future: “Thou are one of the House of Ephraim called to push the people together from the ends of the earth and from the Isles afar off.”[6] The Patriarch continued, “You shall lead thousands to Zion.” Joseph F. heard many other promises, including “The mantle of thy Father shall be upon thee. . . . Your name shall be had in honorable remembrance among the Saints for ever. . . . Your posterity shall be great. . . . They shall spread upon the Mountains so numerous that they cannot be numbered for Multitudes.” The blessing concluded with a solemn “Even so Amen.”[7]

Church Patriarch John Smith, ca. early 1850s, photograph by Marsena Cannon, Salt Lake City, Utah. Courtesy of CHL.

Church Patriarch John Smith, ca. early 1850s, photograph by Marsena Cannon, Salt Lake City, Utah. Courtesy of CHL.

The third event occurred when Mary Fielding died on 21 September 1852. Joseph F. was thirteen years old and Martha Ann was eleven. Mary Fielding’s stepchildren were older but still relatively young: twenty-five-year-old Lovina was married and living in the Midwest, John was unmarried and one day short of his twentieth birthday, Jerusha was unmarried and sixteen years old, and Sarah was unmarried and fifteen years old. Mary Fielding’s death deeply affected all of Hyrum’s children, but none more than Joseph F. and Martha Ann.

In successive moves, Martha Ann and Joseph F. lived with Hannah Grinnels, the housekeeper and caretaker; their aunt Mercy Thompson; and their older half brother, John Smith. According to a family tradition, Martha Ann remained with John Smith until she was married in 1857.[8]

Mary Fielding’s death occurred less than three months after Joseph F. received his patriarchal blessing. She had been his “strong spirit and wise mind” guide and now she was gone.[9] Like the approaching fall weather, Mary Fielding’s death began to cast a long dark shadow over his baptism and patriarchal blessing. During the next two years, Joseph F.’s future seemed less certain than what his patriarchal blessing envisioned.

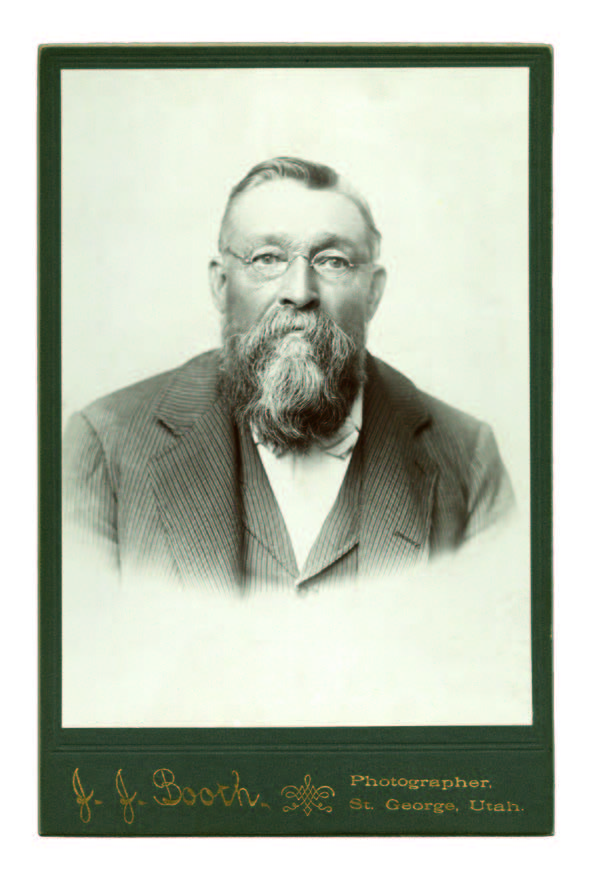

Samuel L. Adams, ca. 1890, photograph by J. J. Booth, St. George, Utah. Courtesy of CHL. Adams, one of Joseph F.’s friends, received a letter from Joseph F. that discussed the challenges he faced following his mother’s death in 1852.

Samuel L. Adams, ca. 1890, photograph by J. J. Booth, St. George, Utah. Courtesy of CHL. Adams, one of Joseph F.’s friends, received a letter from Joseph F. that discussed the challenges he faced following his mother’s death in 1852.

In 1888 Joseph F. described to a friend, Samuel L. Adams (1856–1910), the turmoil he felt following his mother’s death: “After my mother’s death there followed 18 months—from Sept 21st, 1852 to April, 1854 of perilous times for me. I was almost like a comet or fiery meteor, without attraction or gravitation to keep me balanced or guide me within reasonable bounds.”[10] Just days before he died in 1918, Joseph F. added, “I had to start out in the world without father or mother. . . . Without anything to start with in the world, except the example of my mother, I struggled along with hard knocks in early life.”[11]

By his own admission, both in public and private, the “hard knocks” included learning to control his temper, impulsive behavior, tendency to judge people hastily, and proclivity to hold a grudge against anyone he felt had wronged his family. He also experimented with two commonly used products of his day—alcohol and tobacco. Joseph F. eventually overcame these habits and invited others to do the same. In some cases, he strongly warned against their use to avoid the consequences of abusing them.[12] This is not surprising since nineteenth-century Latter-day Saints did not generally observe the Word of Wisdom the way their modern counterparts are required to do today.[13]

Doctrine and Covenants 89, a revelation known as the Word of Wisdom, was originally “sent” as a “greeting” and “not by commandment or constraint” when it was given to the Saints through the Prophet Joseph Smith in February 1833.[14] Martha Ann and Joseph F. lived at a time when waterborne disease, especially cholera, killed tens of thousands of people during several pandemics in the 1800s, including along the Mormon Trail between 1849 and 1855.[15] People in the second half of the nineteenth century faced diseases without the medical advances that have made twentieth- and twenty-first-century epidemics less common and deadly. In this setting, fermented drinks ended up being a safe alternative to local water sources. Later engineering advances eventually provided clean-water delivery systems and took human and animal waste away from human water sources.

Additionally, most Americans believed in the use of alcohol for medical purposes. Even though Latter-day Saints generally believed “the general use of whiskey and liquor was contrary to the principle [of the Word of Wisdom],” they nevertheless generally believed “these beverages had redeeming medicinal qualities. It was drunk by some to help remedy the effects of cholera, and evidently was used as an alleviating cure for the effects of other sicknesses.”[16] Joseph F. held a similar position.[17]

The use of tobacco in the United States was widespread, increasing almost exponentially from the 1800s to the mid-1960s. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Americans consumed tobacco primarily in the form of chewing tobacco and cigars. As one report notes, “The [annual] per-capita consumption of tobacco products in the early 1880s was approximately 6 pounds of tobacco per person aged 18 and older; 56 percent of that tobacco was in the form of chewing tobacco, whereas only 1 percent took the form of manufactured cigarette.”[18] Spitting tobacco was publicly acceptable for most common people, and spittoons were ubiquitous.[19]

Historian Jed Woodworth provides context for the gradual acceptance of the Word of Wisdom:

It required time to wind down practices that were so deeply ingrained in family tradition and culture, especially when fermented beverages of all kinds were frequently used for medicinal purposes. The term “strong drink” certainly included distilled spirits such as whiskey, which thereafter the Latter-day Saints generally shunned. They took a more moderate approach to milder alcoholic beverages like beer and “pure wine of the grape of the vine, of your own make.” For the next two generations, Latter-day Saint leaders taught the Word of Wisdom as a command from God, but they tolerated a variety of viewpoints on how strictly the commandment should be observed. This incubation period gave the Saints time to develop their own tradition of abstinence from habit-forming substances. By the early 20th century, when scientific medicines were more widely available and temple attendance had become a more regular feature of Latter-day Saint worship, the Church was ready to accept a more exacting standard of observance that would eliminate problems like alcoholism from among the obedient. In 1921, the Lord inspired President Heber J. Grant to call on all Saints to live the Word of Wisdom to the letter by completely abstaining from all alcohol, coffee, tea, and tobacco.[20]

Mission to the Sandwich Islands

Sometime during the winter of 1853–54, Martha Ann and Joseph F. were in school when, according to Joseph’s own recollection, the teacher pulled out a leather strap to punish Martha Ann.[21] Although corporal punishment in schools[22] was a common practice in the nineteenth century, Joseph F. defended his younger sister and shouted at the schoolmaster, D. M. Merrick, “Don’t whip her with that!” When Merrick turned on him, the apparently stronger frontier boy “licked him good and plenty.”[23]

This incident reveals the internal conflict Joseph F. faced as a young man in the wake of real persecution, loss, and death.[24] As noted, Joseph F. never seems to have been able to forget or forgive those who he felt wronged his family. Now Mary Fielding was gone and Joseph F. was in trouble.[25]

Joseph F. was expelled from school following the incident with the schoolteacher, ending his opportunity to continue a formal education. Apparently hoping to provide Joseph F. the direction he desperately needed in life, Church leaders decided to act to save the young man. During the April 1854 general conference, President Brigham Young (1801–77) read the names of those “appointed . . . to go on missions,” including the list of those called to the “Pacific Isles,” three thousand miles away from Salt Lake City.[26] Among those called to the islands was fifteen-year-old “Joseph Smith (son of Hyrum).”[27] Like most of those called that day, Joseph F. had no warning or even suspicion that he would be asked to serve a full-time mission. Called to the Sandwich Islands, he was at the time the youngest missionary ever called to a full-time proselyting mission in the Church.[28] As was the custom, Joseph F. was also endowed at this time.[29]

Joseph F.’s missionary certificate, signed by the First Presidency of the Church, is dated 18 April 1854. Six days later, on 24 April, he received the Melchizedek Priesthood and was ordained an elder by Church Apostle and family relative George A. Smith (1817–75), his father’s cousin. On the same day, Joseph F. “received [his] endowments in the old Council House” and was set apart as a missionary by Apostles Orson Hyde (1805–78) and Parley P. Pratt (1807–57), “Parley being mouth.”[30]

Years after Joseph F.’s mission to the Hawaiian Islands, George A. Smith visited the home of Ira Ames (1804–69) in Wellsville, Cache County, Utah, with Joseph F., who had just become a member of the Quorum of the Twelve in 1867. Charles W. Nibley (1849–1931), who was present on the occasion, remembered Old Father Ames asking George A. “who of the Smiths was this young Joseph F.” George A. replied, “He was Hyrum’s son; his mother Mary Fielding Smith.” Ames then observed, “He looks like a likely young fellow.” George A. agreed, “Yes, I think he will be alright. His father and mother left him when he was a young child, and we have been looking after him to try and help him along. We first sent him to school, but it was not long before he licked the schoolmaster and could not go to school. We then sent him on a mission, and he did pretty well at that. I think he will make good as an apostle.”[31] Joseph F.’s call to serve in Hawai‘i when he was a young, inexperienced, and rough fifteen-year-old began a personal journey that would eventually allow him to claim many of the promises he received from his baptism, confirmation, and patriarchal blessing.

George A. Smith, ca. 1856, photograph by Marsena Cannon, Salt Lake City, Utah. Courtesy of CHL.

George A. Smith, ca. 1856, photograph by Marsena Cannon, Salt Lake City, Utah. Courtesy of CHL.

In May 1854 Joseph F., along with twenty-one other missionaries going to the Pacific Isles, left Salt Lake City.[32] The group traveled to San Francisco by way of San Bernardino,[33] where some of them worked in the nearby mountains making “cut shingles” to help pay for their traveling expenses.[34] Joseph F. and some of the missionaries embarked from San Pedro on a steamer for San Francisco and then departed on the Vaquero for the islands on 8 September 1854.[35] They finally arrived in Honolulu, the capital of the Kingdom of Hawai‘i, nearly twenty days later, on 27 September 1854.[36]

The Sandwich Islands had been first dedicated for missionary work just four years earlier, in 1850.[37] According to one study, the total Hawaiian population (including those who were part Hawaiian) stood at 71,019 about the time Joseph F. arrived. Christianization was virtually complete with a Protestant membership of 56,840, followed by a Catholic membership of 11,401 and a Latter-day Saint membership of 2,778.[38] The Saints were organized into fifty-three branches scattered around the islands.[39]

Challenges and Opportunities

Joseph F. faced major challenges during his first mission to the islands, including a new language, new culture, new and exotic foods, and exposure to new religious traditions.[40] Biographer John J. Hammond observes, “It is hard to imagine today what a shock it was for New England sailors and missionaries to see the Sandwich Islands (Hawai‘i) for the first time: the flora and fauna was different, the food unrecognizable, the customs and language incomprehensible. . . . It was an extreme exercise in faith. They had little funds; there was no support system in case they were without food or lodging; the mission existed in name only and had no assets. . . . Many missionaries could not cope and soon left the islands.”[41]

Joseph F. was one of the missionaries who decided to stay in Hawai‘i until he was honorably released. He discovered that the people he served “had different habits to anything I had before known, and their food, and dress and houses and everthing were new and strange.”[42]

Lāhainā Fever

Within a few days, Joseph F. was assigned to labor in Maui. He recalled, “On my way to Maui, on board a small schooner, I was attacked with a severe fever, which clung to me for over two weeks.”[43] Mary Jane Dilworth Hammond (1831–77), the wife of Elder Francis A. Hammond (1822–1900), took care of him during this critical time and noted his progress in her diary.

Sat. Oct 7th /

Sund Oct. 8th /

Tues Oct 10th all quite well I buisy washing untill 9. o clock then called school and sewed a little Bro Joseph is better this morning he has had the Lahaina fever but not heavey.

Frid Oct 13th /

The Hawaiian Language

About three months after arriving in the islands, Joseph F. had not yet spoken in Hawaiian in any meeting even though he had been diligently studying the language. Elder Redick N. Allred (1822–1905) decided that the time had come and invited him, in Joseph F.’s words, to “give out the hymn, then to pray, and then, before the close of the meeting, to speak, all of which I did to the best of my knowledge, and I felt, and so did he, that the ‘ice’ was now broken.”[45] The same day or the next (Joseph F. could not remember) he “accompanied Brother Allred to another branch . . . where I took my part with him in administering the sacrament, blessing some children and baptizing and confirming, all of which I did in the Hawaiian language.”[46]

Joseph F. was now fully engaged and was sent on a 125-mile tour of the Church branches on the east end of Maui with a Native Hawaiian missionary, Elder Pake (unknown dates). Joseph F. recalled, “We made a sucessful tour, visited all the branches, held meetings and were warmly received and kindly treated by all.”[47]

About a month later, Joseph F. reported to Martha Ann, “I am well and Harty. and Have grew conciderable since you saw me last that things were progressing.”[48] In March 1855 Joseph F. reported to George A. Smith, “I have been greatly blessed in obtaining a portion of their language, and by the blessings of the Lord I have got so that I can chat quite freely with the natives in their own tongue.” He continued “to speak in meetings several times in the native language.”[49]

Mission president Francis A. Hammond noted with delight that Joseph F. had spoken in the April 1855 conference, “causing all the saints to rejoice exccedingly. He has only been here 6 months. The Lord has been with him in getting hold of the language. He spoke very feelingly & I rejoiced much to hear his voice in the native language.”[50]

“My Candid Opinion”

Joseph F.’s observations about life in the islands are not surprising given the cultural, political, religious, and historical context. In his surviving diaries and letters from his first mission to Hawai‘i, he recorded his candid opinions about almost everything he observed and experienced.[51]

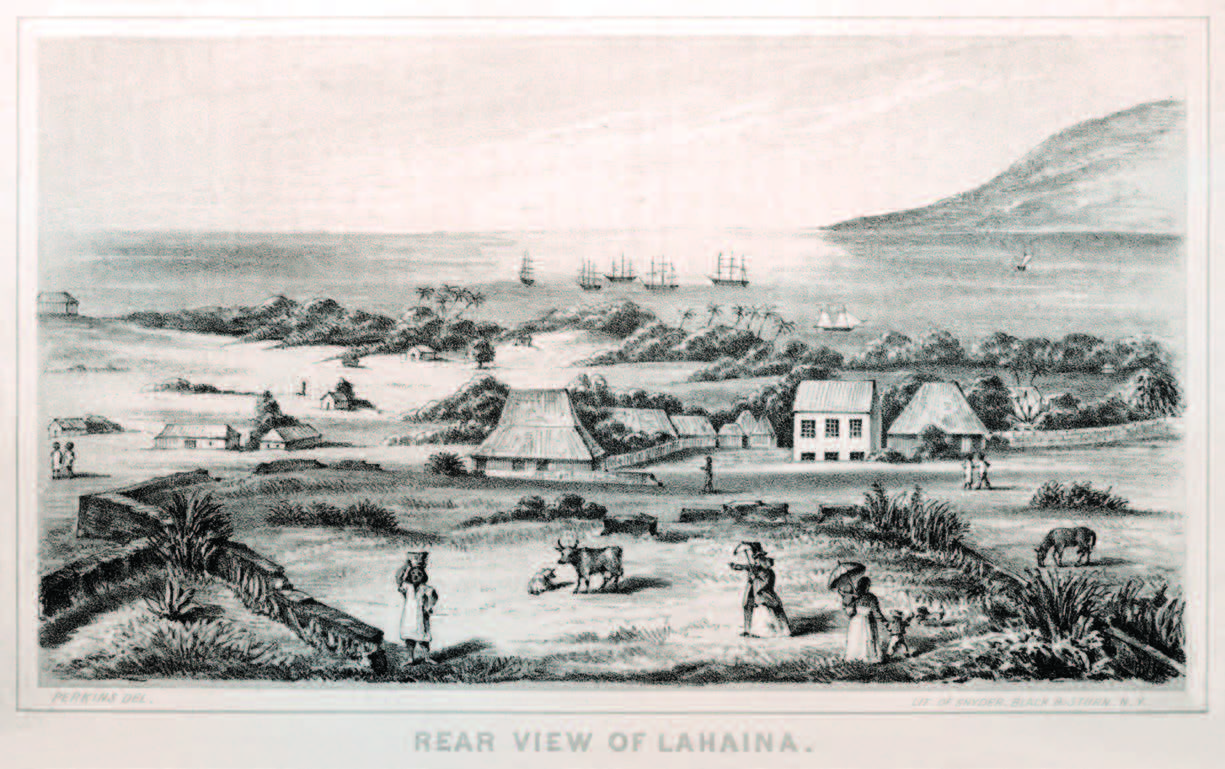

In one letter written to his sister from Lāhainā on the island of Maui, Joseph F. observed, “The signs of the times here are about as useual, there is but one Ship in this harbar now. but the streats are sworming with sailors, and prostitutes of the lowest grade. I tell you it is differant here to what it is in the vallyes. Men and Women go about the streats day and night, one party seeking for money and the other seeking to spend it, we can only let them . . . work out their own damnation.”[52]

Rear View of Lahaina, showing several ships in the harbor, published in Edward T. Perkins, Na Motu: or, Reef-Rovings in the South Seas (New York: Pudney & Russell, 1854).

Rear View of Lahaina, showing several ships in the harbor, published in Edward T. Perkins, Na Motu: or, Reef-Rovings in the South Seas (New York: Pudney & Russell, 1854).

Joseph F.’s journals and letters are remarkably candid in revealing his personal views on matters, including other Latter-day Saint missionaries and Hawaiian Church members. Not only did missionaries have to deal with Christian ministers who criticized the Church, but they also had to deal with John Hyde, a former Church member and one of the most notorious apostates during the early Utah period. He had been called to Hawai‘i as a full-time Latter-day Saint missionary, most likely to rekindle his spiritual commitment to the Church. However, on his way to his mission, Hyde rejected his faith and decided to give lectures critical of the Church in Hawai‘i.[53] Eventually Hyde published his most influential book critical of the Church, Mormonism: Its Leaders and Designs.[54]

Joseph F.’s surviving mission journals highlight the physical, emotional, social, and spiritual challenges he faced as a young teenager, including the struggle to find adequate food during much of his mission. He recorded that on Molaka‘i, for example, most of the people were “afflicted with a scarcity of food.”[55]

During this mission, Joseph F. also confronted difficult economic challenges as he labored without “purse or scrip.”[56] Many local members were poor themselves, as noted above, and sometimes they were either unable or unwilling to help the missionaries, who in such cases had to find employment.[57] When the members did help, Joseph F. was grateful and noted that such kindnesses and sacrifices “should not be forgotten.” For example, he noted in March 1856 that a brother “gave me his shoes from off his feet and went barefooted himself.”[58] Given their own situation and their past support of the missionaries, the members’ help and support were nothing less than remarkable.

Joseph F. and his fellow missionaries generally lived with the local people in thatched-roof huts and ate the same foods. As a result they were often criticized by British and Anglo-American Protestant missionaries for lowering their standards. The young Joseph F. struggled to adapt to this new environment. “I have slept in places where should my hog sleep my stumiche would forbid me eating of it,” he wrote.[59] In other words, the conditions were so poor that he would not eat a pig that lived in the same manner.

Joseph F.’s letters and journals note other challenges he faced that were unlike anything he had experienced before his mission: “I was a little dubious about going into the seas there had been 15 sharks caught . . . the longest was about 6 feet.”[60] The very young teenager sometimes struggled with Church members, Latter-day Saint missionaries, and religious leaders and missionaries of other denominations. He welcomed letters from home and was greatly disappointed when a letter did not arrive as expected.

The Gathering at Lāna‘i

As early as 1831, Latter-day Saint missionaries invited converts to leave their homes wherever they lived and gather to specific geographical areas identified by their leaders. Beginning in 1847, most converts were invited to gather in Utah. However, since the laws of the Kingdom of Hawai‘i prevented Native Hawaiians from emigrating to the United States, Church leaders asked the Hawaiian converts to gather on the island of Lāna‘i.[61] Joseph F. also noted this situation in one of his letters to his sister: “The Sandwich Island mission is rather weacker than it has been <for> sone time.”[62] In addition to the challenges that the Saints who remained behind experienced, Joseph F. wrote about the difficulty that the gathering caused for those who moved to Lāna‘i. “The Natives are verry poor here upon this Island as they have mostly all left their homes and came to this place.”[63]

Joseph F. noted while on Hawai‘i, “I allmost sometimes dread when sunday comes, for where the fiew saints who are left, are so dull and indifferant as those in my field, it is a hard task to preach to them in plainness.” Yet there were times when he felt a “good spirit” among the members of the Church, as he observed: “Where the saints are alive to the work, it is a chearing in sted of a labourious task to address them.”[64]

Joseph F.’s success in learning Hawaiian and his persistence in preaching the gospel led to a number of assignments in his mission, including being assigned as a conference president.[65] The first assignment came when at only age sixteen he was called as “President over the Maui Conference,” which included forty-one branches with 1,253 members.[66] He also served as president of the Kohala Conference on Maui. He was then sent to preside over the Hilo Conference on Hawai‘i, the largest island in the chain, followed by an assignment to direct the work on Molaka‘i.

Fire on Lāna‘i

On 26 June 1856, Joseph F. received a letter from Edward Partridge Jr. (1833–1900), a fellow missionary, informing him that a fire had destroyed one of the mission buildings on the island of Lāna‘i. “The house is burnt to the ground,” Partridge wrote, “and what is wors, most of the things that ware in it. four trunks were destroyed—three only saved. yours I am sorry to say was burned with its contents.”[67] Joseph F. lost two diaries, presumably covering the period from his arrival in 1854 to the end of 1855, extra clothes, toiletries, books, and letters, including those sent to him by Martha Ann.[68] He added, “Well these dear earned fiew things is gon and not one saved, and now I am destitute, but with old Jobe exclaim, ‘The Lord givith and the Lord taketh away, blessed by the name of the Lord’ I am confident that he has and will provide for his servants, so all is well.”[69]

In the last year of his mission, the Church’s stability in Hawai‘i had changed dramatically from the early period of rapid conversions and growth. The work not only had leveled off but also had begun a steady decline. The challenges, difficulties, and trials Joseph F. faced on this first mission provided a foundation for his lifelong service in the Church. As many have observed, he left home as a boy but nearly four years later returned to Utah as a man. This manhood was not only in terms of his physical size, but also included a more mature spirit, increased administrative acumen, and, most importantly, a new ability to serve as a powerful preacher and teacher of the restored gospel.

The Utah War and Mission Release

On Saturday, 3 October 1857, Joseph F. recorded in his journal that Brigham Young had requested that all missionaries “that could be spared” be released from their missions and return immediately to the Utah Territory.[70]

For weeks in the early spring of 1857, rumors had been spreading in the Latter-day Saint settlements in Utah that the president of the United States, James Buchanan, was sending troops to Utah to put down a “Mormon uprising.” Many federally appointed officials in Utah who were not Latter-day Saints felt that the Saints defied their authority and that the territory needed stronger federal control. Brigham Young, who had been the territorial governor since 1850 when the Utah Territory was created by the federal government, received news that mail had been cut off and that a new governor had been appointed to replace him. More alarmingly, various reports also noted that a large military force of twenty-five hundred soldiers was on its way to Utah to establish complete federal authority there.

“We expect to have warm times here,” wrote President Young to the missionaries in Hawai‘i, “would you not come and help us? if so, hasten to our midst.”[71] Accordingly, thirteen missionaries were released from the Sandwich Island Mission and gave farewell addresses during a conference the following day; Joseph F. was among them.[72] He departed Honolulu for California on 6 October aboard the Yankee, a 343-ton bark built in 1854.[73]

The Deseret News reported that the missionaries “arrived in San Francisco, from the Sandwich Islands, on the 22d October.”[74] The report continued, “They were all in good health, and were preparing to prosecute their journey, at as early a date as possible, to their homes from which they have been absent since the spring of ’54.”[75] The party arrived home in the Salt Lake Valley on 24 February 1858.

After his arrival, Joseph F. immediately enlisted in the territorial militia and spent the next several months performing various duties in defense of the Latter-day Saints during the crisis. Fortunately, the conflict was settled by negotiations in the spring of 1858. However, by that time Brigham Young had been replaced as governor of the Utah Territory with a federal appointee who came from outside Utah, the military had established a permanent headquarters west of Utah Lake in Cedar Valley, and the Saints’ lives had been significantly disrupted by the events of 1857–58.[76]

Having served as an elder in the Church during his mission, Joseph F. was ordained “into the 32nd quorum of Seventies” on 20 March 1858.[77] He spent the rest of the year working to support himself. As the harvest season ended, as was customary, many Saints gathered from time to time at dances and socials during the slower winter months. Apparently Joseph F. participated in these diversions as occasion allowed. Joseph “was ordained a High Priest, and appointed a member of the High Council of the Salt Lake Stake of Zion” on 16 October 1858.[78]

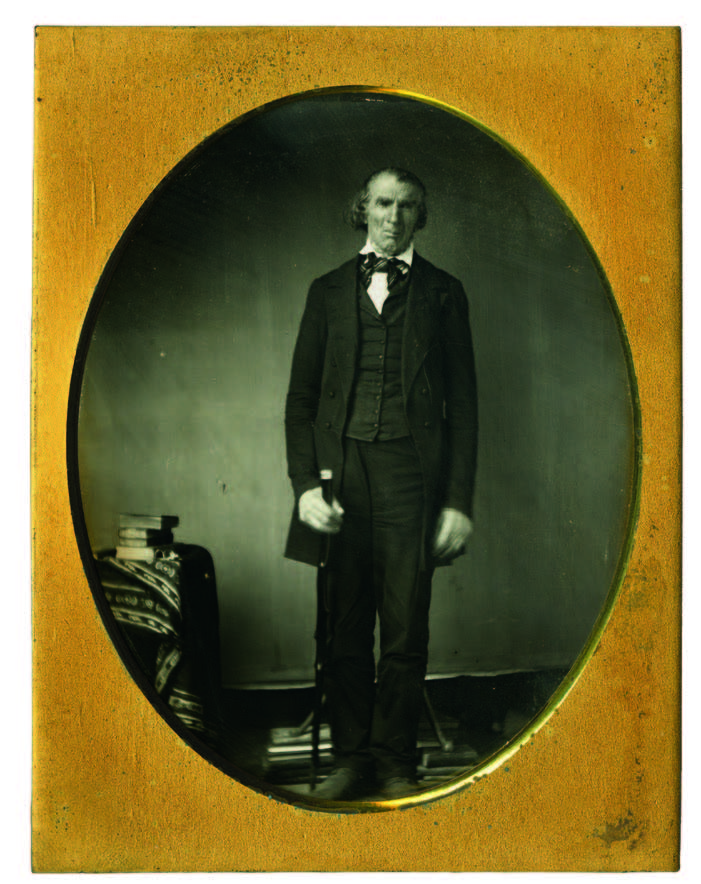

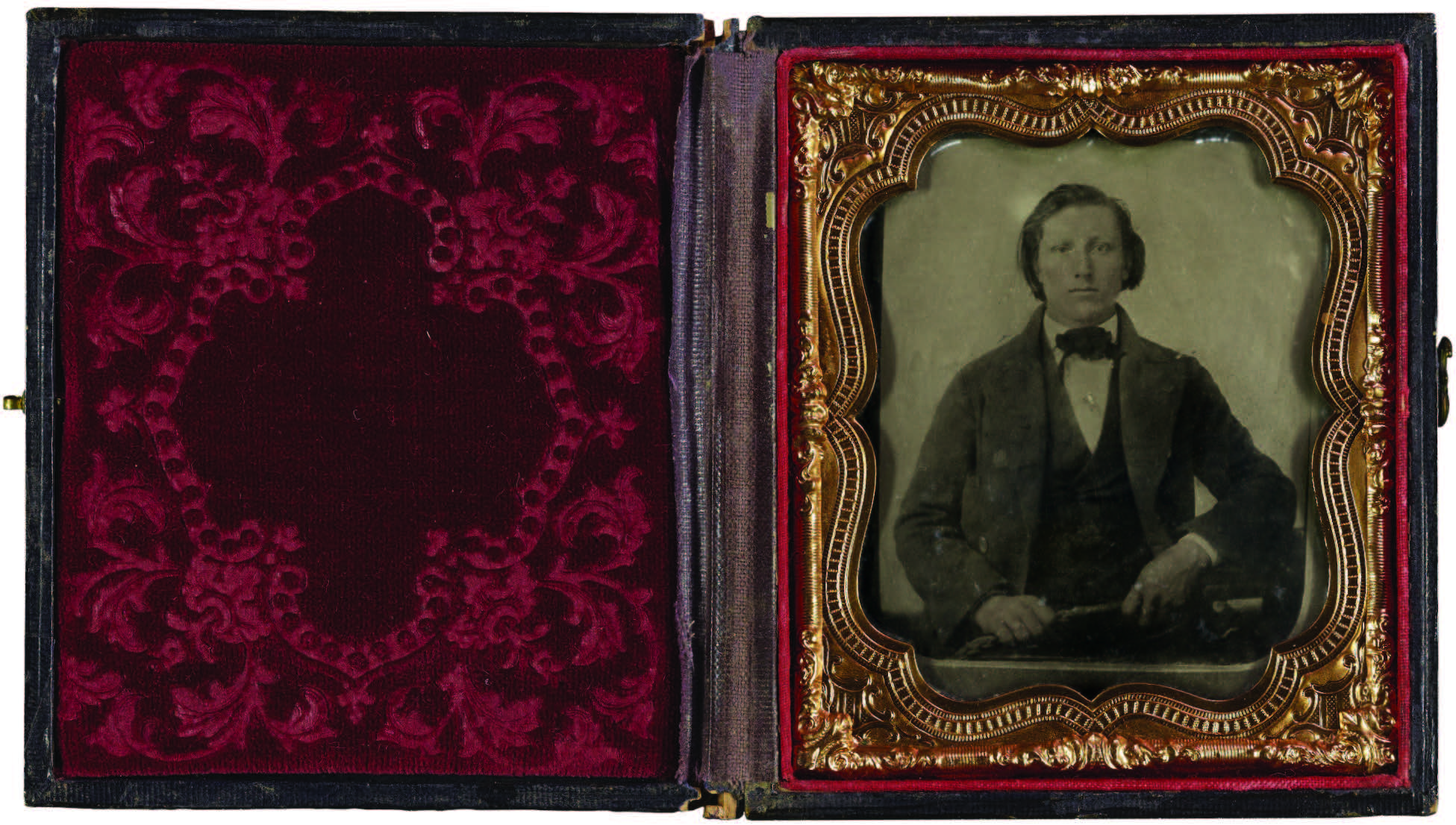

Joseph F. Smith, ca. 1858. Courtesy of CHL. This is the earliest known photograph of Joseph F. Smith, taken shortly after his return from his service in the Hawaiian Mission. He was between nineteen and twenty years of age. Later C. R. Savage of Salt Lake City, Utah, made a photographic print of the original ambrotype. This second-generation image is found in many collections.

Joseph F. Smith, ca. 1858. Courtesy of CHL. This is the earliest known photograph of Joseph F. Smith, taken shortly after his return from his service in the Hawaiian Mission. He was between nineteen and twenty years of age. Later C. R. Savage of Salt Lake City, Utah, made a photographic print of the original ambrotype. This second-generation image is found in many collections.

Courtship and Marriage

Joseph F. became romantically interested in his cousin Levira Annette Clark Smith (1842–88).[79] By February 1859 he was willing to reveal his affections to her. “It is with feelings of true emotions that I attempt to address you a few lines this morning,” he wrote. Struggling “to deliniate the feelings of my beating heart, in writing,” Joseph F. confessed his love for Levira. “I am aware that our acquaintance has been short to you, I do not know how pleasant, but allow me to say, that since I saw you first, the admiration and respect I first concieved for you. have daily grown, till they have changed to something stronger and more fervent.” Expressing his uncertainty regarding her feelings, he undertook “to simply aske you, cousin . . . what you think of ‘Cousin Joe.’”[80]

Levira must have reciprocated Joseph F.’s regards because only a few months later, on 5 April 1859, Church President Brigham Young performed the marriage sealing for them in his office in Salt Lake City. The Journal History of the Church adds, “A sumptuous wedding feast was prepared at Alfred Randells and partaken of by their friends and relatives.”[81]

Challenging Years for Martha Ann

Following the death of her mother in 1852, Martha Ann’s life was in flux. For a time, as noted previously, she remained at the family homestead with Hannah Grinnels, even though John Smith, Hyrum’s oldest son from his first wife, had been appointed by Brigham Young to be the family guardian.[82]

Mary Fielding Smith’s Home, 31 August 2018, photograph by Kate Beasley Holzapfel. This adobe home, built in 1850, was where Joseph F. and Martha Ann lived much of their lives during the 1850s. Martha Ann, following

Mary Fielding Smith’s Home, 31 August 2018, photograph by Kate Beasley Holzapfel. This adobe home, built in 1850, was where Joseph F. and Martha Ann lived much of their lives during the 1850s. Martha Ann, following

her marriage to William Jasper Harris in 1857, moved away to establish her own home. Courtesy of Kate Beasley Holzapfel.

Joseph F. left on his mission in late September 1854 while Martha Ann remained with family. Over the next several years, Martha Ann apparently spent some time at the home of her aunt Mercy Fielding (1807–93), her mother’s sister, living with her cousin Mary Jane (1838–1901).[83] It is clear from letters between Martha Ann and Hellen Maria Fisher (1835–1907), John Smith’s wife, that Martha Ann also lived with John and Hellen in the family homestead from at least 1856 to 1857.[84]

These years continued to be challenging for Martha Ann, as one would expect for such a young child. She often felt alone and isolated. Martha Ann noted in her letters that she did not always get along with John’s wife, Hellen, and other members of the family.[85] She often felt that John, her older half brother, was insensitive to her concerns.[86]

Adding to the challenges at home, Martha Ann was unable to attend school as much as Joseph F. encouraged her to because of the demanding nature of farm life and their poor financial situation. As noted, she frequently mentioned her poor writing skills and apologized for them in letters to Joseph F. When he asked her to write Ina Coolbrith (1841–1928) and Agnes Smith (1836–73), their cousins in California, Martha Ann declined, most likely because she felt embarrassed about her rudimentary writing skills.[87]

Life on the farm kept Martha Ann quite busy. A family history written by Martha Ann’s daughter notes: “Martha had little time for idleness. She did many chores, morning and night, before and after school. She herded sheep on the hills east of home, many times barefooted until her feet would bleed. She spun wool into yarn and wove the yarn into cloth, blankets, sheets, jeans for men’s clothing and linen with cotton war[p] and woolen wool for women’s clothing.” She also gleaned wheat with her friend Jane Fisher, which earned them enough money to purchase their own winter dresses.[88] Throughout the early letters, Joseph F. and Martha Ann wrote on occasion about the family farm animals, often referring to them by name as if they were beloved pets.[89]

When Martha Ann did have free time, much of it was spent with her friend Jane Fisher, the younger sister of John Smith’s wife, Hellen Maria Fisher. The Fisher family was apparently very close with the children of Hyrum Smith, as evidenced by several letters between Joseph F. and his sister and by letters between Joseph F. and the Fishers. Letters between Joseph F. and Jane suggest some early budding romantic feelings between them.[90] On at least two occasions, Martha appended brief notes to the end of letters Jane had written to Joseph F.[91]

The Reformation of 1856–57

In 1856 and 1857, nearly ten years after the Saints began to settle the Great Basin, Church leaders launched a spiritual renewal known as the “Mormon Reformation,” or simply the “Reformation.”[92] During this time the Saints were asked to join their leaders in personal introspection and soul-searching, the hope being that the Saints would increase their commitment to live gospel principles and heighten their individual spirituality. Martha Ann noted in a letter to her brother, “I hav been looking at myself and noticeing my self and triiy to reform and I see that I need a good deal of tutuing before I can become perfect.”[93] While commending his sister for her desires to reform, Joseph F. also advised prudence: “It is a good thing if you commence by degrees, you know this world, though small, cannot be circumscribeed with one huge stride, . . . therefore you see Martha that all our faults cannot be overcome in a moment, but they must be forsaken little by littel.”[94]

Perhaps one impact of the Reformation that most profoundly influenced Martha Ann was the increased emphasis on marriage, including participating in plural marriage, which the Church had openly announced in 1852.[95] “There is great excitment among the young folks here about getting married,” wrote William Harris, a family friend. “There is from twenty to forty a getting married evry day.”[96] The anxiety over marriage even made its way to the Sandwich Islands, where letters warned the missionaries that all the young girls in the territory were being married off.[97] However, Joseph Fisher, in a letter to young Joseph F., wrote that his daughter Jane “& 2 or 3 girls in the city are single yet not because they havent had offers but I think they must be waiting for some of the young misionari<e>s to return.”[98] Jane was most likely waiting for Joseph F.’s return.[99] Martha Ann had apparently also turned down several proposals of marriage. Joseph Fisher indicated that Martha Ann “frequently has proposials for mariage but none of them soots [suits].”[100] Martha Ann, however, soon found one proposal that did capture her attention.

Martha Ann’s Marriage to William Jasper Harris

Fifteen-year-old Martha Ann married twenty-year-old William Jasper Harris on 21 April 1857, just as the Reformation was ending. William had been called to serve a mission to the British Isles and reported at the Endowment House, a temporary temple and administrative office on the Temple Block in Salt Lake City, to be set apart as a missionary. A Church leader attending the meeting asked if there was anyone present who would consider marrying before departing for the mission field. William mentioned Martha Ann and was instructed to “go and get her right now and be married.”[101] When he entered the house, he asked Martha Ann to marry him that day. She turned to William’s mother and asked what she should do.[102] Her future mother-in-law responded, “Law me, honey, put on the calico dress and go with him!”[103] Martha Ann did and climbed into the wagon and headed to the Endowment House, where they were married. William left his young bride to begin his mission to England two days later.[104]

Martha Ann may have stayed with John Smith, her older half brother, for a time after William left, but she eventually went to live with her new mother-in-law, Emily Hill Harris Smoot (1815–82). Her son, Richard P. Harris, reported, “Martha lived with her mother-in-law and helped her spin and weave, milk many cows, make butter and cheese, and do all the other household duties. . . . [Emily Hill Harris] sat beside [Martha Ann] in the schoolroom and learned to read and write.”[105]

When Martha Ann reunited with Joseph F. is not known. The reunion must have been short-lived because Utah was on the move as the US Army made its way to the territory.

Like many other Salt Lake area residents, Martha Ann moved south with the family and relocated temporarily to Pond Town in Utah County.[106] As peace was established, most of the Salt Lake Valley Saints returned to their homes in the latter part of July 1858. Martha Ann, recalling her trip back to Salt Lake Valley, noted, “As we were travelling along the road I was driving a team of horses. I just drove around the Point of the Mountain[107] when we saw a man riding on a white mule. To my great surprise it was my husband. We had not heard from him for six months so we were not expecting him. It was an agreeable surprise. We reached home safe and found the old house just as we left it.”[108]

Lightning Strike

Not very long after this reunion, William Harris and Joseph Abbott (1840–59) were struck by lightning while plowing and sowing a field in Salt Lake City near what is now known as Pioneer Park on 18 May 1859.[109] The Deseret News reported a few days later, “On Wednesday last, about five p.m., William Harris and Joseph Abbott, engaged in planting corn, on what is commonly known as the ‘Old Fort Square,’ were struck by lightning and the latter instantly killed. Harris was knocked down, his body badly burned, and was taken up for dead but, by unwearied exertion, was resuscitated and in a fair way to recover. A light shower was passing over the city. Harris was furrowing out the ground and Abbot, a lad about 17 years old, was dropping the corn immediately after the plow and within ten or twelve feet of the other at the time of the occurrence.”[110]

According to a family tradition, William was dragged across the field by his frightened team of horses and was found by John Smith, his half brother-in-law. Abbot was an orphan who had been living with the Abraham O. Smoot family.

William never fully recovered from this accident and struggled physically for the rest of his life as a result. A short time later in August 1859, William and Martha Ann’s first child was born, William Jasper Harris Jr. (1859–1926).

The Final Letter of the 1850s

As noted earlier, Joseph F. returned home from his mission in Hawai‘i during the Utah War and immediately enlisted in the militia to help defend the Saints from the approaching military force sent by President Buchanan. When Joseph F. wrote his final extant letter to his sister during this decade, she was living temporarily in Utah County following the evacuation of the northern settlements. He was at the family farm in the Sugar House Ward. After the military threat had passed, most of the Saints who had moved south returned to their homes in the northern settlements.

Gaining an Education

Though short on formal education, Joseph F. and Martha Ann experienced significant personal growth during this period of their teen years. For Joseph F., informal education came primarily from serving a mission. He recalled in 1875 that it was in the Kingdom of Hawai‘i that he wrote his very first letter: “I was 15 years old and had never written a letter in my life, and did not know how to write a duzzen words, but I began to feel the need of education so I studied and practiced and prayed and tried to learn and have been learning at a disadvantage ever sine until now I can just write to be understood.”[111] That practice included preparing and sending a prodigious number of letters to missionaries, Church leaders, family, and friends, including his younger sister. Additionally, during this first mission Joseph F. also became a voracious reader, increasing his vocabulary, his knowledge of a variety of subjects, and his interest in the wider world.[112]

Summary

By the end of December 1859, Joseph F. was twenty-one years old and married with no children. Martha Ann was eighteen years old and married with one child.

Joseph F.’s surviving Hawaiian diaries often provide insights on the interconnection with the letters. For example, on 24 May 1856, he wrote, “Spent time reading one letter from my sister Martha. . . . I received good news from home. The folks were all well. Martha was on a visit to her friends in the city.”[113] On the following day, 25 May 1856, he recorded, “I wrote two letters today in answer to those received last evening from my Sister and cousin.”[114]

This experience in the islands of the Pacific helped shape Joseph F.’s understanding of an expanding worldwide Church and prepared him to hold significant administrative responsibilities as he continued to minister to the Saints and others. Years later, after receiving a copy of the “Hawaiian Annual” for 1907, Joseph F. sent a note to thank the missionary who sent it and reflected, “So many years of my youth and early manhood have been spent upon those ‘beautiful Isles of the Sea,’ that I naturally hail with delight the coming of any souvenir or reminder of passed scenes, and circustances of my triple sourines [sojourns], and later visit there.”[115]

Martha Ann, on the other hand, remained in Utah for the rest of her life (except for a few brief visits to California and Texas later in life), caring for family, friends, and neighbors.[116] She saw the world beyond the valleys in Utah largely through her brother’s letters. Martha Ann’s letters to Joseph F. provided him an important window into her life and helped keep him updated on events in Utah. Joseph F. was able to fill in gaps as he read letters from a variety of individuals writing him from home. Later, during his second mission, Joseph F. told Martha Ann that her letters “were my best corispondent on the Islands.”[117]

The surviving letters written between them in this decade reveal their love, loyalty, support, and concern for each other, especially during times when they were separated by long distances.

Notes

[1] The so-called Mormon cricket (Anabrus simplex) is a wingless species of shield-backed katydid. See https://

[2] See Frank T. Matheson, The Mary Fielding Smith Adobe Home (Boulder, CO: Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education, 1980).

[3] See David M. Whitchurch, “Personal Glimpses of Joseph F. Smith: Adolescent to Prophet,” in Joseph F. Smith: Reflections on the Man and His Times, ed. Craig K. Manscill et al. (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2013), 159–80.

[4] Sixty-Eighth Annual Conference (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret News Press, 1898), 65–66. See also Joseph F. Smith, Gospel Doctrine: Selections from the Sermons and Writings of Joseph F. Smith, comp. John A. Widtsoe, 5th ed. (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1939), 117–18.

[5] John Smith, “Patriarchal Blessing of Joseph F. Smith, 1852.” Joseph F. received a second patriarchal blessing on 25 February 1874 under the hands of his older half brother, John Smith (not to be confused with his father’s uncle, John Smith, who gave him his first blessing in 1852).

[6] See Doctrine and Covenants 58:44–45; Deuteronomy 33:17.

[7] John Smith, “Patriarchal Blessing, 1852.”

[8] Richard P. Harris, “Martha Ann Smith Harris,” Relief Society Magazine, January 1924, 14.

[9] Smith, Gospel Doctrine, 646.

[10] Joseph F. to Samuel L. Adams, 11 May 1888.

[11] “Minutes of a Meeting Held at the Bee Hive House, 1918 November 10.”

[12] See Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 14 June 1872, herein.

[13] The current requirement to observe the proscriptions mentioned in the Word of Wisdom as a test of fellowship and worthiness was established by President Heber J. Grant in 1921. See Thomas G. Alexander, Mormonism in Transition: A History of the Latter-day Saints, 1890–1930 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1986), 258–71; and Paul H. Peterson and Ronald W. Walker, “Brigham Young’s Word of Wisdom Legacy,” BYU Studies 42, nos. 3–4 (2003): 29–64. Currently, Latter-day Saints are not required to observe the prescriptions (as opposed to proscriptions) mentioned in the Word of Wisdom.

[14] Doctrine and Covenants 89:2; emphasis added.

[15] See Charles E. Rosenberg, The Cholera Years: The United States in 1832, 1849 and 1866 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987).

[16] Paul H. Peterson, “An Historical Analysis of the Word of Wisdom” (master’s thesis, Brigham Young University, 1972), 24.

[17] Joseph F. noted in 1879, “I bought a gallon of Alcohol at the drug store for bathing and medical purposes. Cost. $3.25 paid.” Joseph F., journal, 10 October 1879. See also Joseph F. Smith to Martha Ann, 28 July 1881, herein.

[18] “Epidemiology of Tobacco Use: History and Current Trends,” in Ending the Tobacco Problem: A Blueprint for the Nation, ed. Richard J. Bonnie, Kathleen Stratton, and Robert B. Wallace (Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2007), 41.

[19] In the late nineteenth-century United States, spittoons became a very common feature of banks, hotels, railway carriages, stores, and government buildings, including the White House and the United States Capitol building.

[20] Jed Woodworth, “The Word of Wisdom: D&C 89,” in Revelations in Context: The Stories Behind the Sections of the Doctrine and Covenants (Salt Lake City, UT: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 2016), 186.

[21] There is no record that explains why the teacher, D. M. Merrick, had chosen to discipline Martha Ann on this occasion. Whatever happened following this incident, B. F. Cummings reported, “President Smith speaks highly of [Merrick] as a teacher . . . and states that under him he made more rapid progress than under any other.” B. F. Cummings, “Shining Lights: How They Acquired Brightness,” Contributor, January 1895, 174.

[22] Legal efforts to stop this practice altogether started with Sweden in 1979, followed by Finland in 1983. In the United States it is still legal in nineteen states as of July 2018. The United Kingdom and the Czech Republic still allow teachers to administer physical punishment in certain situations and with certain limitations.

[23] Charles W. Nibley, “Reminiscences of President Joseph F. Smith,” Improvement Era, January 1919, 191–92; see also Smith, Gospel Doctrine, 656.

[24] Stephen C. Taysom opines that events from Joseph F.’s birth in Far West, Missouri, until his arrival in Utah were defining moments; see Taysom’s forthcoming biography, “Like a Fiery Meteor”: The Life of Joseph F. Smith.

[25] Joseph F. reflected on this challenging period, as he did about the other challenges he faced later in life, in public and private, inviting others to learn from his mistakes and his triumphs. For a thoughtful and sympathetic discussion, see Nathaniel R. Ricks, “Triumphs of the Young Joseph F. Smith,” in Manscill et al., Joseph F. Smith: Reflections on the Man and His Times, 37–51.

[26] “Minutes,” Deseret News, 13 April 1854, 2–3.

[27] “Minutes,” Deseret News, 13 April 1854, 2–3.

[28] The Hawaiian Islands were known as the Sandwich Islands at this time. They were so named by the first European visitor, Captain James Cook, after his sponsor, John Montagu, 4th Earl of Sandwich. The Sandwich Islands are composed of eight major islands, several atolls, and numerous islets. In 1854 these islands were an independent kingdom ruled by King Kamehameha III (King Kamehameha the Great). Beginning in the 1840s, the current name, Hawaiian Islands, began to be used and eventually became the common designation.

[29] At this time, temple ordinances were being performed in the upper room of the Council House, located on the corner of Main Street and South Temple Street.

[30] Andrew Jenson, “The Twelve Apostles: Joseph Fielding Smith,” Historical Record 6, nos. 3–5 (May 1887): 184.

[31] Smith, Gospel Doctrine, 655–56. Reminiscences present historians with challenges because memory often influences the way a story is remembered, especially after a long period of time has passed before retelling the story. As a result, historians are careful how they use reminiscences, preferring to use contemporary primary sources instead. However, lacking the kind of primary sources needed to adequately reconstruct Joseph F.’s life before he began to record his thoughts and experiences in letters and personal journals in the mid-1850s, we have exercised caution in drawing on reminiscences.

[32] Joseph F. later noted that he departed Salt Lake City “in company with D. M. Merrick, bound for the Sandwich Islands.” Joseph F., journal, 5 May 1857. If this was the same schoolmaster that he “licked,” there may have been reconciliation rather quickly following the incident at school.

[33] This was an important Latter-day Saint agricultural settlement in Southern California founded in 1851; see Edward Leo Lyman, San Bernardino: The Rise and Fall of a California Community (Salt Lake City, UT: Signature Press, 1996).

[34] Jenson, “Twelve Apostles,” 185.

[35] Conway B. Sonne, Ships, Saints, and Mariners: A Maritime Encyclopedia of Mormon Migration, 1830–1890 (Salt Lake City, UT: University of Utah Press, 1987), 193–94.

[36] Jenson, “Twelve Apostles,” 186.

[37] The mission covered several of the islands, but most of the work centered on Hawai‘i (for which the island chain eventually took its name), Maui (an important Protestant missionary and New England whaling center), Lāna‘i (the Church’s gathering place in the 1850s), Moloka‘i (where Joseph F. spent the last four months of his mission), O‘ahu (where the political capital of the Kingdom of Hawai‘i was located at the time), and Kaua‘i (an island west of O‘ahu); see R. Lanier Britsch, Unto the Islands of the Sea: A History of the Latter-day Saints in the Pacific (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1986), 94–95.

[38] Robert C. Schmitt, “Religious Statistics of Hawaii, 1825–1972,” Hawaiian Journal of History 7 (1973): 41–47.

[39] Fred E. Woods, “The Palawai Pioneers on the Island of Lanai: The First Hawaiian Latter-day Saint Gathering Place (1854–1864),” Mormon Historical Studies 5 , no . 2 (Fall 2004) : 5.

[40] Hawai‘i was in transition from a pre-Christian culture to a new, amalgamated Christian culture, one heavily influenced by New England Calvinist missionaries and Anglo-American merchants, traders, and whalers. Their economic, political, religious, and social world had been turned upside down with the advent of British and American explores, whalers, and missionaries. Aspects of precontact Hawaiian culture had been officially banned beginning in 1818. However, some Hawaiians retained certain practices and beliefs or adapted them.

[41] John J. Hammond, Island Adventures: The Hawaiian Mission of Francis A. Hammond, 1851–1865 (Salt Lake City, UT: Signature Books, 2016), ix.

[42] Hyrum M. Smith III and Scott G. Kenney, comps., From Prophet to Son: Advice of Joseph F. Smith to His Missionary Sons (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1981), vii.

[43] Jenson, “Twelve Apostles,” 186.

[44] Mary Jane Dilworth Hammond , journal, vol . 1 , 1853–1855, BYU.

[45] Quoted in Jenson, “Twelve Apostles,” 186.

[46] Quoted in Jenson, “Twelve Apostles,” 186.

[47] Quoted in Jenson, “Twelve Apostles,” 187.

[48] Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 28 January 1855, herein.

[49] Joseph F. to George A. Smith, 19 March 1855, published in “Sandwich Islands,” Deseret News, 11 July 1855, 143.

[50] F. A. Hammond, journal, 8–9 April 1855.

[51] For a good reason, Nathaniel R. Ricks titled his edited edition of Joseph F.’s Hawaiian mission diaries “My Candid Opinion”: The Sandwich Islands Diaries of Joseph F. Smith, 1856–1857 (Salt Lake City, UT: Signature Books, 2011).

[52] Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 18 February 1856, herein.

[53] See, for example, “Utah as It Is,” The Polynesian, 18 October 1858, 94; and “Lectures on Mormonism,” The Polynesian, 25 October 1856, 98. Interestingly, a letter to the editor, written by one of the Latter-day Saint missionaries, Edward Partridge, was published in the same issue. See Edward L. Hart, “John Hyde, Junior—An Earlier View,” BYU Studies 16, no. 2 (1976): 1–7.

[54] John H. Hyde Jr., Mormonism: Its Leaders and Designs (New York: W. P. Fetridge, 1857).

[55] Jenson, “Twelve Apostles,” 187.

[56] Latter-day Saint missionaries generally relied on members and others for food, housing, and laundry services during their labors. This common nineteenth-century missionary practice was based on Luke 10:4 and Doctrine and Covenants 24:18.

[57] The Hawaiian population had been decimated by the introduction of European weapons and disease, including sexually transmitted ones, following the arrival of Captain Cook in 1778. While exact numbers are unknown, the population may have fallen from an estimated 300,000 at the time of European contact to fewer than 80,000 by 1854. The economic situation in the islands eroded significantly during this period, and the culture was in complete disarray. Those living away from Honolulu, the capital of the Kingdom of Hawai‘i, lived in a variety of conditions, but many lived in what some have described as wretched conditions.

[58] Joseph F., journal, 1 March 1856.

[59] Joseph F., journal, 4 July 1856.

[60] Joseph F., journal, 22 July 1857.

[61] Church leaders established the City of “Iosepa,” or Joseph, in the Palawai Basin (identified by the Saints as the “Valley of Ephraim”) as the gathering place for Hawaiian converts.

[62] Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 23 November 1855, herein.

[63] Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 25 July 1857, herein.

[64] Whitchurch, “Personal Glimpses,” 169.

[65] Nineteenth-century Latter-day Saint missions were composed of conferences or districts. Each mission conference contained several local congregations identified as branches.

[66] Jenson, “Twelve Apostles,” 187.

[67] Copied by Joseph F. into his journal, letter dated 4 June 1856; see Ricks, “My Candid Opinion,” 37–38.

[68] See Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 12 December 1856, herein.

[69] Joseph F., journal, 26 June 1856.

[70] Joseph F., journal, 3 October 1857.

[71] Joseph F., journal, 3 October 1857.

[72] Joseph F. borrowed money from Silas Smith to leave immediately. However, because there were two Silas Smiths in the mission at this time, it is not known which one loaned the money. See biographical register, “Smith, Silas” and “Smith, Silas Sanford.”

[73] Sonne, Ships, Saints, and Mariners, 202.

[74] “Missionaries,” Deseret News, 9 December 1857, 317.

[75] “Missionaries,” 317.

[76] See Richard Neitzel Holzapfel, A History of Utah County (Salt Lake City, UT: Utah State Historical Society, 1999), 85–94.

[77] Jenson, “Twelve Apostles,” 189.

[78] Jenson, “Twelve Apostles,” 189.

[79] Before the mid-twentieth century, marriage between cousins was not only legal and socially acceptable in Western culture but also the norm in royal families. Queen Victoria and Prince Albert of the United Kingdom are the most famous examples during this period. In the United States, cousin marriage was legal in every state and territory before the Civil War. It was also legal in Canada, where Sir John A. Macdonald, who became the premier of the province of Canada (1856) and Canada’s first prime minister (1867), married his cousin Isabella Cark in 1843. Levira Annette Clark Smith was the daughter of Samuel Harrison and Levira Clark Smith. Her father was a brother to Hyrum Smith, Joseph F. and Martha Ann’s father. See biographical register, “Smith, Levira Annette Clark.”

[80] Joseph F. to Levira, 26 February 1859.

[81] Church Historian’s Office, Journal History of the Church, 5 April 1859, 1. Alfred J. Randall (1811–91) was a family friend and had accompanied Joseph F.’s father and uncle to Carthage in 1844. Randall was one of the last Latter-day Saints to leave the jail on 26 June, the day before the martyrdom. The Randall family had also been with the Smith family in Winter Quarters and had traveled with the Smiths to Utah in 1848. At the time of the marriage, Randall lived on West Temple just north of the Temple Block.

[82] There seems to be some confusion as to exactly what role John Smith took in caring for the family during this period, likely in part because he was serving as the Church Patriarch and appears to have been periodically working away from home. See Joseph F., journal, 31 January 1856.

[83] Mercy Fielding (Thompson) is the sister of Mary Fielding Smith, Martha Ann and Joseph F.’s mother. See biographical register, “Thompson, Mary Jane.”

[84] See Martha Ann to Joseph F., 31 January 1856 and 3 May 1857, herein. See also letter from Hellen Maria Fisher to Joseph F., 5 July 1857.

[85] Whatever difficulties existed between Hellen Maria Fisher and Martha Ann were later resolved. Details of when or how the resolution came about are unknown. See Martha Ann to Joseph F., 5 April 1857, herein.

[86] See J. B. Haws, “Joseph F. Smith’s Encouragement of His Brother, Patriarch John Smith,” in Manscill et al., Joseph F. Smith: Reflections on the Man and His Times, 133–58.

[87] Agnes Moulton Coolbrith married Don Carlos Smith, brother of Hyrum Smith, on 30 July 1835 in Kirtland, Ohio. They were parents of three children, the youngest being Josephine (Ina) Donna Smith. See biographical register, “Coolbrith, Agnes Moulton” and “Smith, Josephine Donna.” Joseph F. may have added to Martha Ann’s trepidation while attempting to encourage her: “I have received a letter lately from Cousin Josephine,” he once wrote. “She said she had written to you but had received no letter in return tolde me to speak to you about it, I would advise you to write to her. do your best to spell and write correct, for she is a good writer, this is what I wish you to progress in, till you are also a good writer.” See Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 14 June 1857, herein.

[88] Sarah Harris Passey, “Martha Ann Smith Harris” (unpublished manuscript in editors’ possession, courtesy of Carole Call King, granddaughter of Sarah Harris Passey).

[89] See Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 9 June 1855 and 14 July 1856, herein; and Martha Ann to Joseph F., 17 December 1856, herein.

[90] See Martha Ann to Joseph F., 29 July 1856, herein.

[91] See Martha Ann to Joseph F., 19 August 1857 and 11 May 1857, herein.

[92] Paul H. Peterson, “The Mormon Reformation of 1856–1857: The Rhetoric and the Reality,” Journal of Mormon History 15 (1989): 59–87.

[93] See Martha Ann to Joseph F., 17 December 1856, herein.

[94] See Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 17 April 1857, herein.

[95] Peterson, “Mormon Reformation of 1856–1857,” 71.

[96] Martha Ann to Joseph F., 3 February 1857, herein.

[97] Joseph Fisher to Joseph F., 24 February 1857.

[98] Joseph Fisher to Joseph F., 24 February 1857.

[99] See Martha Ann to Joseph F., 29 July 1856, herein.

[100] Joseph Fisher was stating that even though Martha Ann had a number of proposals, none were suitable for marriage. Joseph Fisher to Joseph F., 24 February 1857. Hellen Maria Fisher also wrote that Martha Ann “is not maried yet, it is not for want of offers.” Hellen M. Smith to Joseph F., 4 April 1857.

[101] Harris, “Martha Ann Smith Harris,” 15.

[102] Emily Hill Harris Smoot; see biographical register, “Hill, Almira Emily.”

[103] According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the exclamation law me is expresses “chiefly astonishment or admiration, or (often) surprise at being asked a question.”

[104] Harris, “Martha Ann Smith Harris,” 15.

[105] Harris, “Martha Ann Smith Harris,” 16.

[106] Pond Town’s name was changed to Salem, after Salem, Massachusetts, hometown of Pond Town’s oldest living resident at the time.

[107] This is the boundary, both geographically and politically, between Salt Lake and Utah Valleys.

[108] Carole Call King, “History of William Jasper Harris, 1841–1921” (paper presented at monthly meeting of the Daughters of Utah Pioneers, copy in the editors’ possession), 4.

[109] A ten-acre park located at 350 South and 300 West in Salt Lake City, site of the first fort built by the Latter-day Saints in Salt Lake Valley in 1847.

[110] “A Sad Occurrence,” Deseret News, 25 May 1859, 1.

[111] Joseph F. to Robert B. Taylor, 9 March 1875; see Scott G. Kenney, “Before the Beard: Trials of the Young Joseph F. Smith,” Sunstone 120 (November 2001): 38.

[112] See, for example, Joseph F., journal, 21 April 1857, where he notes receiving and reading a number of issues of two Church newspapers, the Deseret News (published in Salt Lake City beginning in 1850) and the Western Standard (published in San Francisco beginning in 1855): “On going to the Post Office, I received four Nos. of ‘D.N.’ and ‘W.S,’ . . . Spent the afternoon reading.” Other entries highlight Joseph F.’s wide range of reading material, which included novels, biographies, and national and international newspapers and magazines. See, for example, Joseph F., journal, 1 July 1857. For a brief summary, see Ricks, “My Candid Opinion,” xiv–xv.

[113] Joseph F., journal, 24 May 1856.

[114] Joseph F., journal, 25 May 1856.

[115] Joseph F. to Abraham Fernandez, 15 May 1907.

[116] She did make several trips to Joseph F.’s home in Southern California; see Martha Ann to Joseph F., 7 July 1914, herein.

[117] Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 15 December 1860, herein.

Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 17 October 1854 (p. 2; pp. 1 and 4 of this letter are displayed on p. xvi)

Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 17 October 1854 (p. 2; pp. 1 and 4 of this letter are displayed on p. xvi)

Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 17 October 1854 (p. 3)