Conclusion

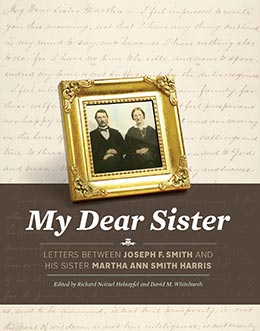

Richard Neitzel Holzapfel and David M. Whitchurch, "Conclusion," in My Dear Sister: Letters Between Joseph F. Smith and His Sister Martha Ann Smith Harris, ed. Richard Neitzel Holzapfel and David M. Whitchurch (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2019), 513–527.

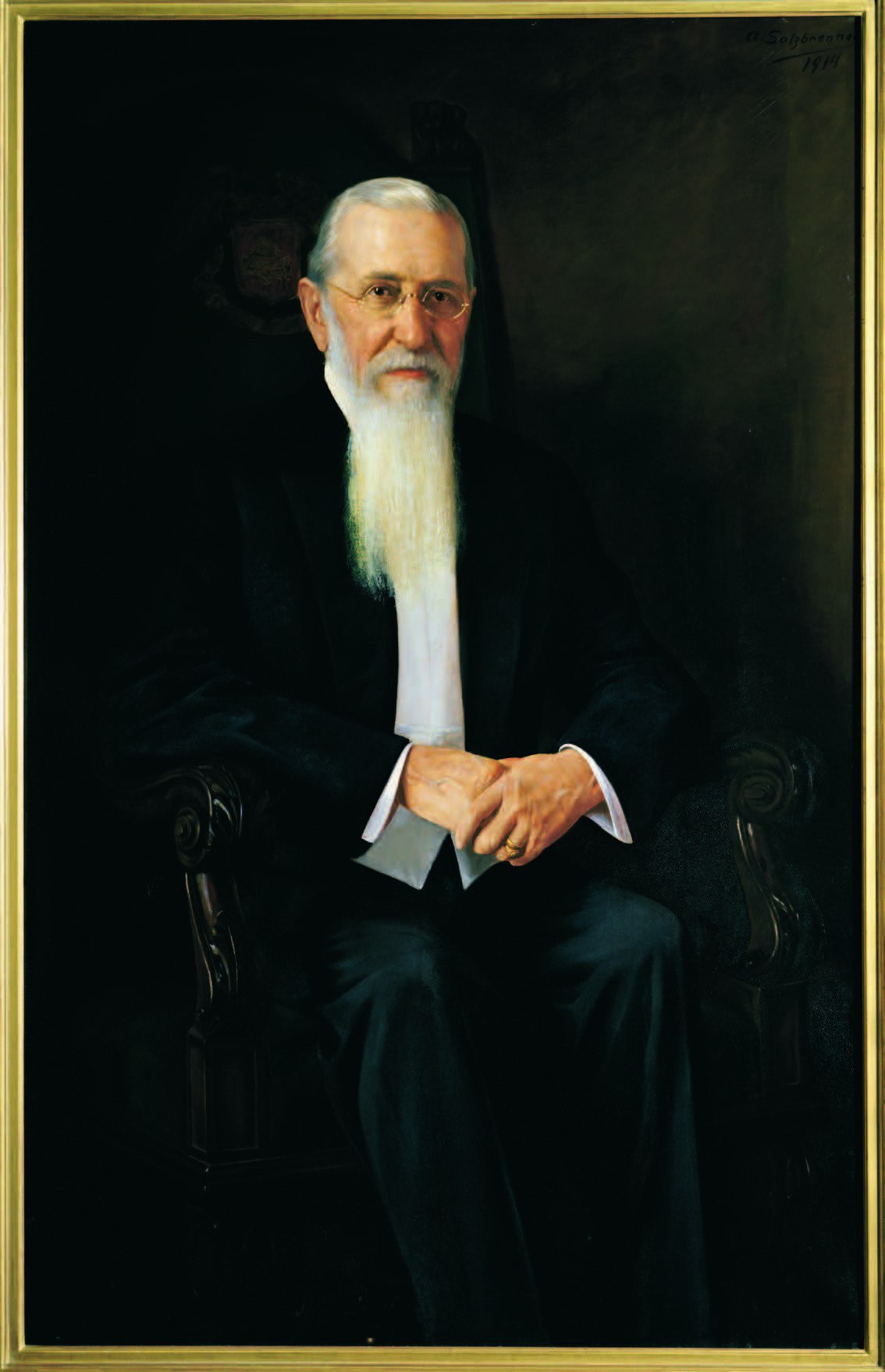

Portrait of Joseph F. Smith, ca. 1916, by Albert J. F. Salzbrenner. Courtesy of CHM.

Portrait of Joseph F. Smith, ca. 1916, by Albert J. F. Salzbrenner. Courtesy of CHM.

In 2018 the Joseph F. Smith family observed two centennial events, one celebrating the reception of the “Vision of the Redemption of the Dead” (3 October 1918) and the other marking the anniversary of Joseph F.’s death (19 November 1918). These events gave family members an opportunity to remember Joseph F.’s consecrated life and labors in behalf of the restored Church of Christ.

Joseph F. Smith’s diaries, letters, sermons, and personal reminiscences from his first mission to Hawai‘i reveal the beginnings of a lifelong process of steady self-improvement and accomplishment in building up the kingdom of God on earth. In 1861 during his mission to the British Isles, he acknowledged that this growth was going to take some time: “I have partly learned one thing, i.e. I am mighty small, and don’t know much—if anything. [p. 3] and I see a great deal more to learn every day and still experience is such a slow-and-sure School Teacher that I do not seem to make scarcely any progress in my lessons, but I hope—‘in patience to possess my soul’ and struggle unceasingly t[0.6 x 2.7 cm vertical tear along fold] the end.”[1]

In 1874, during another mission to England, Joseph F. reflected in his diary, “I pray God to give me the spirt of my mission & ability to performe every duty acceptably.”[2] He had been struggling with an assignment to edit the Church’s longest continuous publication, the Millennial Star. He recorded the day before, “[Tuesday, May 12, 1874] Busy most of the day trying to write for the Star, but did not get the Spirit.”[3] What he noted in his journal the next day is indicative of the faith and persistence that characterized his life and so often bore fruit in projects both small and large: “Busy most of the day writing. Did not feel clear went and prayed & felt better.”[4]

A source of Joseph F.’s motivation to dedicate his life’s labors to the Church is evident in an 1883 letter to a member who had requested permission to be sealed to or adopted[5] into Hyrum Smith’s family through Joseph F. “My father was a martyr for the truths sake,” he averred, “and wears his crown as such, my prayer and earnest, live-long desire is to prove true and faithful to the end as he did. . . . There is no doubt about the endurance or exaltation of those who die faithful but mortality is shrouded with uncertainty.”[6]

Less than seven months before he became President of the Church in 1901, Joseph F. wrote a letter to President Lorenzo Snow (1814–1901) to seek forgiveness following meetings he had participated in with the First Presidency and Quorum of the Twelve Apostles. According to Elder Rudger J. Clawson, a member of the Twelve present at those two meetings, “a discussion was held on 26 February 1901 about a ‘law now pending before the Utah legislature making it unlawful for anyone to bring a charge of adultery against a married man except the legal wife, she being the aggrieved party.’” Clawson noted that the purpose of the law was to “curtail the power of our enemies, who seek to bring trouble upon the Latter-day Saints by prosecuting polygamists for unlawful cohabitation.”[7] Recalling that George Q. Cannon was concerned about “the wisdom of passing such a law at this time,” Clawson reflected, “There is no question as to the advantages it would bring to our people, but it has been thought by some that it would bring trouble upon the church, as our enemies would claim that we were taking steps to revive the practice of polygamy, which is not true.”[8]

As was common in these meetings, “the brethren were called upon to give an expression of their views, and all present expressed themselves in favor of the bill, except Pres. Cannon, who thought it an unwise measure. Pres. Snow said he was not quite clear in his mind as to the policy and wisdom of such a law at this time. A vote was taken and was unanimous in favor of the measure.”[9]

Two days later, on Thursday, 28 February 1901, Church leaders met again at 11:00 a.m. The council opened with a hymn and a prayer. President Snow then raised concerns about the previous meeting (held on Tuesday, 26 February), indicating that “a difference of view existed among the brethren regarding the proposed law on adultery, and in the discussion that followed feelings of an improper character were manifested as between Pres. Cannon and Pres. J. F. Smith.”[10] President Snow said “that the matter ought to be rectified and the perfect union of the Twelve restored. He took the view that Pres. Smith was at fault.” Clawson further reported, “Pres. Smith made suitable acknowledgments and was freely forgiven. Pres. Geo. Q. Cannon also asked forgiveness, which was freely granted.”[11] The meeting closed with a hymn, “School Thy Feelings, O My Brother,” and a prayer.

Following this meeting, Joseph F. felt it necessary to send a personal letter of apology to President Snow:

I was deeply moved and grieved and hurt that I had in the least wronged any of my brethren [including President George Q. Cannon] by thought, word, or deed without being, myself, conscious of it, thereby injuring myself, even more than any one else, and giving you occasion or necessity for administering such severe reproof. . . . This was very hard to bear. I deeply regret it. . . . I humbly bow to the chastisement I have received, accepting your reproof, and that of the other brethren and esteem it as a timely earning and a blessing to me which by the help of the Lord I will endeavor to profit by throughout the future. I sincerely ask the Lord, yourself, and the brethren to thoroughly forgive my past mistake and follies, which I trust have been errors of the head more than of the heart, and I will try to do better.[12]

The refining process of a future President of the Church continued for another seventeen years. In 1907, after many years of being personally attacked and lampooned in the press, President Smith modestly reflected, “The Devil don’t care much about me. I am insignificant, but he hates the Priesthood, which is after the order of the Son of God!”[13] Despite his realistic view of his personal weaknesses and his vulnerability as a public figure, he persevered and continually improved as a disciple of Jesus Christ.

In January 1907 President Smith gave a memorable discourse in Provo titled “At Rest in Christ.”[14] In it he posited the question, “What does it mean to enter into the rest of the Lord?” His considered answer was emblematic of his own single-minded resolve to endure in faith and thereby win an eternal crown:

Speaking for myself, it means that through the love of God I have been won over to Him, so I can feel rest in Christ, that I may no more be disturbed by every wind of doctrine, by the cunning and craftiness of men, whereby they lay in wait to deceive; and that I am established in the knowledge and testimony of Jesus Christ, so that no power can turn me aside from the straight and narrow path that leads back to the presence of God, to enjoy exaltation in His glorious kingdom; that from this time henceforth I shall enjoy that rest until I shall rest with Him in the heavens.[15]

Joseph F. had tasted that rest and lived accordingly until eventually, through a long refining process, he saw the fulfillment of the Patriarch’s inspired declaration back in 1852: “Your name shall be had in honorable remembrance among the Saints for ever.”[16]

Close associate and friend Charles W. Nibley reflected shortly after Joseph F.’s death in 1918 that “many of the older people now alive can recall that forty years ago, or even less, he [Joseph F.] was considered a radical, and many a one of that time shook his head and said, ‘What will become of things if that fiery radical ever becomes president of the Church.’ But from the time he was made president of the Church, and even before that time, he became one of the most tolerant of men; tolerant of others’ opinions. . . . None more ready to forgive and forget.”[17]

Another observer, Judge Charles C. Goodwin (1832–1917), the former editor of the anti-Church Salt Lake Tribune from 1883 to 1903, noted just two years before Joseph F. died that he had “mellowed as the years” went by and that he sees “the good in humanity and forgives men their trespasses.” Goodwin added, “A more kindly and benevolent man has seldom held an exalted ecclesiastical position in these latter days than President Joseph F. Smith of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.” The former critic and enemy of Joseph F. observed, “To his people he is the great spiritual leader. To men at large he is a man of wide sympathies, great business acumen and a born leader of the great institution of which he is head.”[18]

A biographer opined, “President Smith’s accomplishments are remarkable. He husbanded five large families and steered Mormonism into a safe and uncontested position in American culture. He defined the nature of Mormonism sans theocracy, cooperatives, and polygamy. He is truly the father of modern Mormonism.”[19]

All evidence suggests that Joseph F. the teenager returned to Utah from that very first mission to Hawai‘i as a young adult having grown physically, intellectually, and spiritually. Moreover, through this three-year mission far away from home and his constant communication with his relatives, including Martha Ann, Joseph F. grounded himself with the same firmness of faith held by his honored father and mother and reflected in his very name, Joseph Fielding Smith.[20]

Joseph F.’s son and biographer, also named Joseph Fielding Smith, recounted his father’s return home from this first mission. In this version of the story, Joseph F. came face-to-face with a drunken, gun-wielding ruffian who asked Joseph F. if he was a Latter-day Saint. Risking being shot on the spot if he responded positively, Joseph F. declared with conviction, “Yes, siree; dyed in the wool; true blue, through and through.” The answer was given boldly and without any sign of fear, which completely disarmed the belligerent man, and in his bewilderment, he grasped the missionary by the hand and said: “Well, you are the —— pleasantest man I ever met! Shake, young fellow, I am glad to see a man that stands up for his convictions.”[21]

As is so often seen in his letters to Martha Ann, Joseph F.’s commitment to the gospel cause was the central focus of his life. An 1885 letter is a prime example:

I am well and as usual engaged in the duties of my calling as a messenger of the Gospel to the people of the Earth. I am as useful here at present as I could be any where. And when my labors will be more useful somewhere else I hope to be found there. With me it is the Kingdom of God or nothing. My only course is onward and, I trust, upward. I can yeald to nothing but the will and pleasure of the Almighty. It is my delight to serve the Lord and the people of God.[22]

His California cousin Ina Coolbrith, whom he continued to encourage and help financially throughout his life, recognized Joseph F.’s and Martha Ann’s commitment to their faith, but not in the same way Joseph F. understood it. When a non–Latter-day Saint relative asked her to visit Salt Lake City after she herself had done so, Ina replied, “Joseph and his sister are good, I do not doubt that, but absolutely fanatic in their religion, and would not, I fear, know anything different from their belief for all the Universe. To me, in this age of reason, it seems almost impossible.”[23]

Paralleling his lifelong commitment to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Joseph F. was his devotion to his family. Although his first marriage tragically ended in a divorce, Joseph F. was a loving and dedicated husband to five other wives and a devoted and much-beloved father to forty-eight children.[24]

Less than four months before his death, Joseph F. spoke at the dedication of a monument erected in honor of his father, Hyrum Smith (1800–1844), in the Salt Lake City Cemetery:

I am rich; the Lord has given me great riches in children and in children’s children; and in the fact that my children have, so far, honored me and their grandfather and their mothers and the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. . . . I trust and pray that all my children and my children’s children to the latest generation will abide in the truth. I want you to just take a look here at a little flock of my grandchildren—right here, every one of them. I love them. I know them all I never meet them but what I kiss them just as I do my own children. I don’t care how dirty their faces are, if I can only have the privilege of meeting with my grandchildren and kissing them and letting them know that I love them just as I love my own children. Then I shall be satisfied, and I expect to continue it as long as I can.[25]

Joseph F. Smith spoke his last words to his family from his deathbed in the Beehive House on Sunday, 10 November 1918. He compared the value of worldly riches and personal possessions with that of his family:

I have a beautiful watch and chain and rings. I never spent a dollar for any of them in my life because I could not afford it, but I have had friends and they have, from time to time, given me rings. A beautiful watch chain and fob were given me on the day of the dedication of the monument to the honor of the Prophet Joseph Smith in Vermont [23 December 1905]. And I had left to me the gold watch that belonged to my Uncle Joseph Smith. . . . . But when I look around me and see my boys and girls, whom the Lord has given to me, and I have succeeded, with His help, to make them tolerably comfortable, and at least respectable in the world, I have reached the treasure of my life—the substance of life worth living—my family. I have a family I am proud of, every individual member of it I love.[26]

Nine days later, on 19 November 1918, President Smith died. The primary sources are clear—he worked tirelessly to fulfil his duty in his family and his assignments in the Church. His unrelenting work schedule most likely contributed to his death. Even though he elevated his counselors as semi-equals, President Smith refused to delegate things that previous Church Presidents had been happy to unload. In particular, the diaries and letters reveal a grueling work ethic, often working until midnight or later. Family members, Church associates, and doctors warned him about the toll that such a regime would eventually have on his health. During the last decades of his life, he complained of severe back problems and a propensity to catching colds.[27] Joseph F.’s unrelenting dedication to minister to his family, his church, and those around him denied him the retirement that many Americans looked forward to and enjoyed.

Martha Ann’s Devotion to Family, Community, and Church

Martha Ann lived a life centered on her family, community, and church. Despite the personal and family challenges she faced, she contributed to her community in various ways, including through Church service, good deeds for neighbors, and a willingness to help extended family members when they were sick or otherwise needed extra help. Joseph F. noted this characteristic in a closing salute to her in December 1912: “you willingly take upon yourself . . . the well-being of others.”[28]

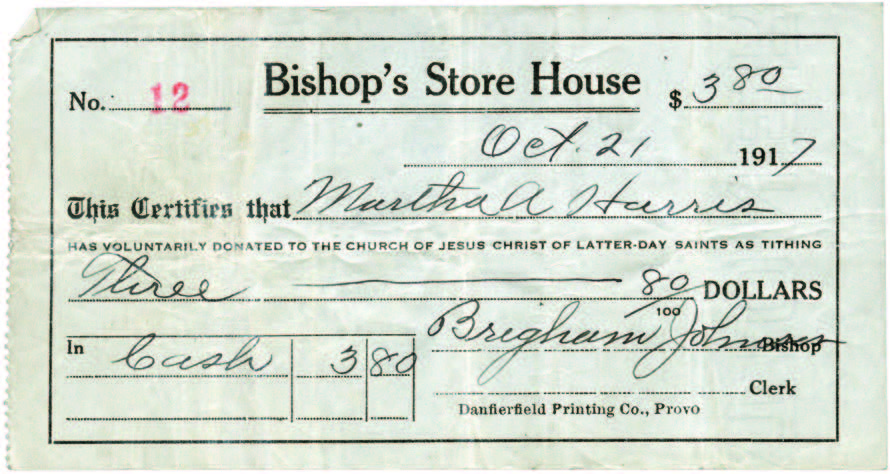

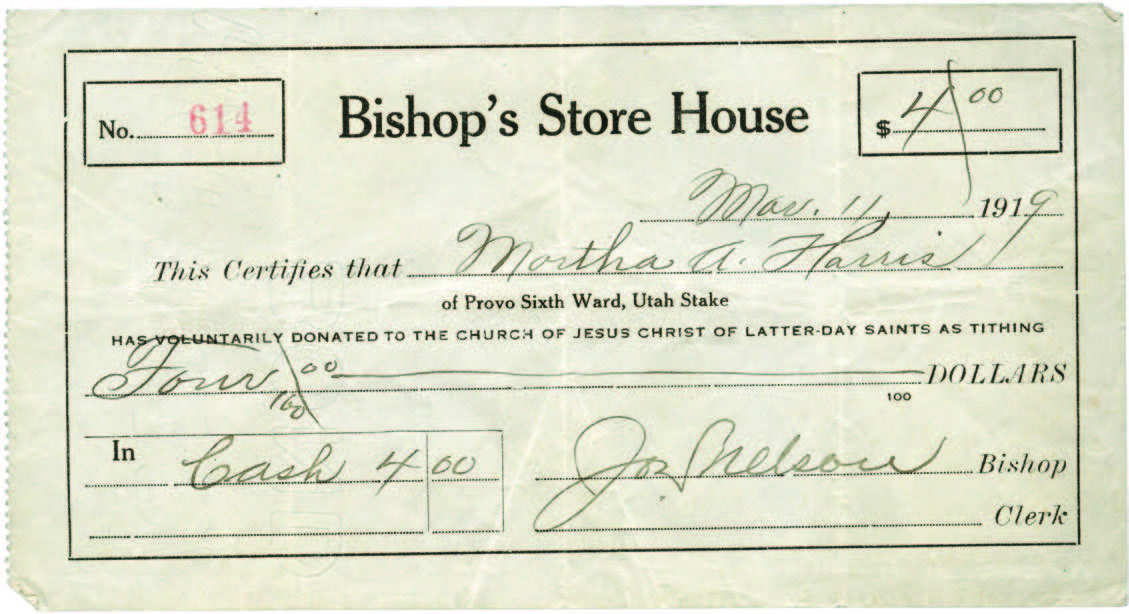

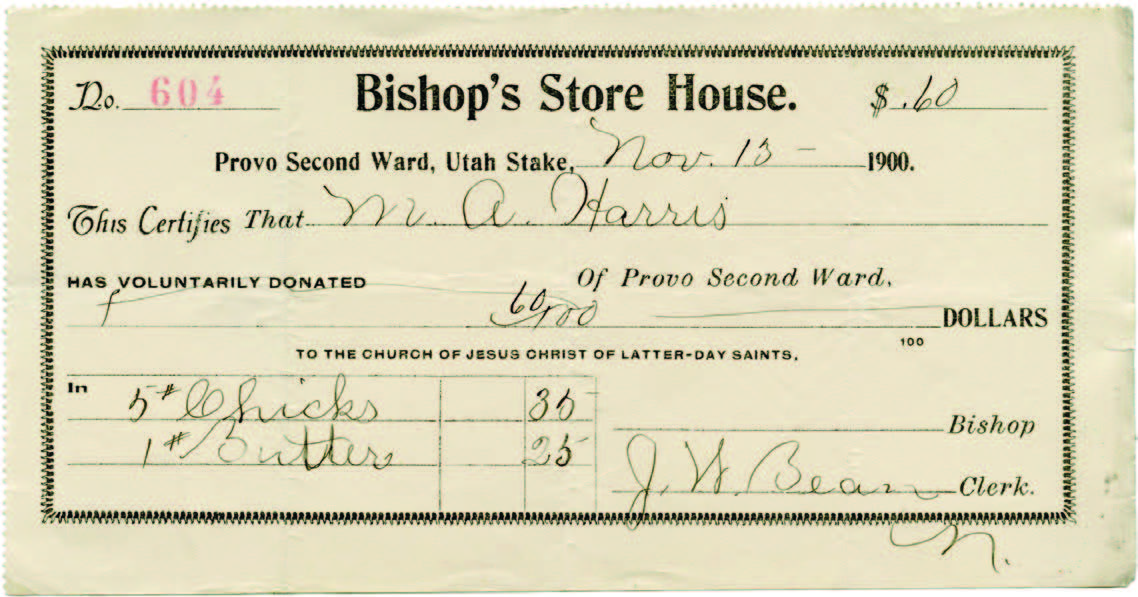

Martha Ann and William were also remembered as being generous, including paying tithes and offerings to the Church and helping others as they could. A grandson wrote, “Martha Ann Harris paid an honest tithing all her life,” a lesson she learned from her widowed mother, Mary Fielding.[29]

Martha Ann’s donation receipts from the Bishops’ Storehouse. Courtesy of Carole Call King.

Martha Ann’s donation receipts from the Bishops’ Storehouse. Courtesy of Carole Call King.

One report said Martha Ann “possessed qualities that brought happiness in all the homes she visited. Her charitable nature, her kindness and her devotion to duty and responsibilities were proverbial.”[30] Joseph F. gave his opinion, “The noblest, and therefore in the true sense, the highest ideas that men can entertain are those of ‘faith, hope and charity’, and in all these I award you credit of being superior to most women, else you would have succumbed to your misfortunes long ago. but your hope, your charity for others, and your faith in providence have sustained you.”[31]

Joseph F. was a pillar of strength to his younger sister Martha Ann throughout her life. When he died in 1918, Martha Ann was undoubtedly overcome with grief. She had already lived nine years without her husband, William, who had passed away in 1909. She now faced the remaining days of her life without her devoted brother and substitute parent who had supported her and encouraged her since they had become orphans in 1852.[32]

Sometimes historians have not fully appreciated the role that women like Martha Ann played in establishing the pioneer settlements.[33] Martha Ann and her family were involved in the transformation of Provo from a rough frontier settlement into a respectable, stable, and thriving long-term modern community. One scholar recently noted, “No one did more, for example, than Mormon women to provide stability and continuity in these communities.” He further observed, “Most frontier women faced similar challenging circumstance, but Mormon women carried additional burdens. Church leadership responsibilities—particularly stints as overseas missionaries—often removed fathers, husbands, and brothers from farming and business operation, leaving these responsibilities in the hands of their women, who soon proved equal to managing the sometimes difficult tasks involved. . . . Although most Mormon women—as one might expect—claimed these burdens were light and their yokes easy, they were called to go with the church and their families an extra mile—or two or three.” He concluded appropriately, “All the more extraordinary, then, that these hardy, hard-working, and dependable women viewed their roles as usual and commonplace, not in the least extraordinary.”[34]

Harris family reunion lunch, 11 April 1917, photograph by George Edward Anderson. Courtesy of Carole Call King. Martha Ann Smith Harris is seated in the first seat on the left. Anderson took two photographs at the luncheon. See George Edward Anderson Collection, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah. The second image focuses on the family members seated at the long banquet tables seen to the right in this view.

Harris family reunion lunch, 11 April 1917, photograph by George Edward Anderson. Courtesy of Carole Call King. Martha Ann Smith Harris is seated in the first seat on the left. Anderson took two photographs at the luncheon. See George Edward Anderson Collection, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah. The second image focuses on the family members seated at the long banquet tables seen to the right in this view.

According to Martha Ann’s son,

All of her eleven children grew up and were married in the temple. . . . The death of one of her daughters left two little babies, a boy and a girl, whom she took and cared for as she had for her own children. Both of these grew up and were married. The girl’s husband died leaving her to provide for herself and another little baby girl. This little girl she would often leave with her grandmother while she went out to work. Thus Martha Harris cared for three generations of babies, giving to each the same love, and care and attention that she had the others, and the first little girl brought her much cheer and happiness, and made her life seem less lonely.”[35]

In May 1921 the Harris family gathered in Provo again—this time to celebrate Martha Ann’s birthday. A Salt Lake City newspaper reported, “The eightieth birthday anniversary of Mrs. Martha A. Harris was celebrated Saturday afternoon at the home of her daughter, Mrs. Roy Passey. The affair was given by her four daughters, Mrs. Passey, Mrs. Walter Startup, Mrs. John Dennis and Mrs. Walter S. Corbett.”[36]

Martha Ann Smith Harris family, including grandchildren and great grandchildren, on her eightieth birthday, May 1921. Courtesy of Carole Call King. The family gathered at Sarah Harris Passey’s home, 618 East Center Street, Provo, Utah. Martha Ann raised eleven children and was loved by seventy-nine grandchildren and sixty-six great-grandchildren.

Martha Ann Smith Harris family, including grandchildren and great grandchildren, on her eightieth birthday, May 1921. Courtesy of Carole Call King. The family gathered at Sarah Harris Passey’s home, 618 East Center Street, Provo, Utah. Martha Ann raised eleven children and was loved by seventy-nine grandchildren and sixty-six great-grandchildren.

More than 112 relatives and friends came together to honor Martha Ann, many of whom came from out of town to celebrate this happy occasion. Among those visiting were Martha Ann’s two sisters-in-law, Edna Lambson Smith and Mary Schwartz Smith, both widows of Joseph F.[37] It was a milestone in many ways. For example, Martha Ann had lived longer than her parents (Hyrum was killed at age forty-four, and Mary Fielding died at fifty-one).

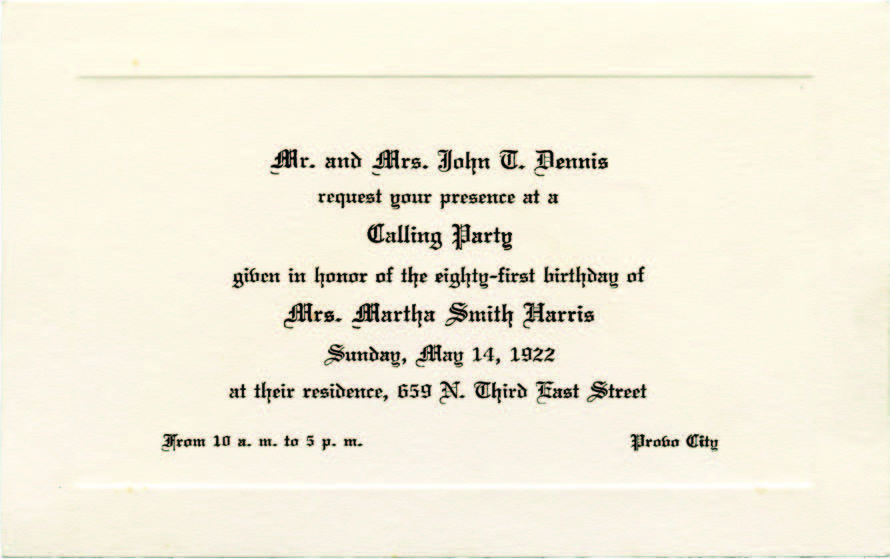

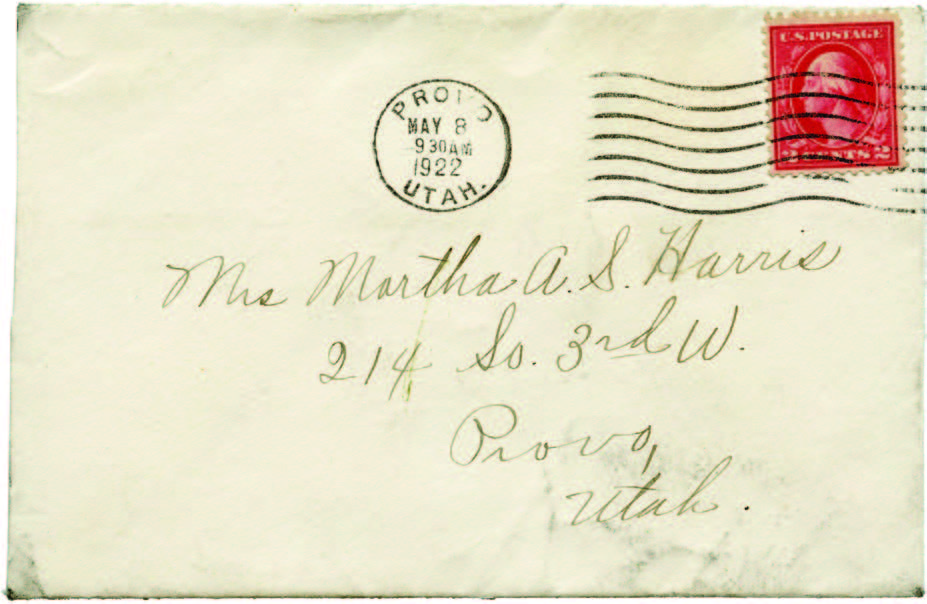

Envelope and invitation to Martha Ann’s eighty-first birthday gathering, 14 May 1922. Courtesy of Carole Call King.

Envelope and invitation to Martha Ann’s eighty-first birthday gathering, 14 May 1922. Courtesy of Carole Call King.

Family members continued to gather to celebrate special events, including Martha Ann’s birthday in 1922. Two months later, according to a family tradition, Martha Ann went to Salt Lake City for the diamond anniversary of the arrival of the pioneers to Salt Lake Valley. On Saturday, 22 July 1922, a special banquet held in the Hotel Utah honored sixty-six of the original 1847 pioneers and 240 pioneers who came behind them, including Martha Ann, who had arrived in the valley in 1848.[38] A local newspaper described those honored as “a hale and hearty crowd for all their years and entered into the enjoyment of the affair with zest and displayed something of the great spirit which had carried them across the plains despite the greatest hardships befalling any band of pathmakers in history.”[39]

Two days later, on Monday, 24 July 1922, the celebration continued at the Saltair Beach Resort on the shore of the Great Salt Lake. Organized by the Central Pioneer Day Committee and Daughters of the Utah Pioneers, the activities included a pioneer banquet and concert from 5:00 pm until 7:00 p.m. The celebration ended with a “spectacular fireworks display in the evening at 9 p.m.”[40]

In the fall of 1923, Martha Ann was at the end of her remarkable life. Silas Schwartz Smith (1900–1986), her nephew, wrote in September 1923:

Dear Aunt Martha, Just a word to tell you how I appreciate that beautiful Temple Apron that you sent me. I wore it when I was married on the fifth of September, and assure you that I value it greatly, especially since I realize the many hours of labor that you placed upon it. It seems good to have something worked out by the hands of Father’s only living Sister. Anella, my wife, and I leave in a few more days for Philadelphia where I will complete my medical training. Then after my hospital work, hope to return to Salt Lake City and take up a practice. It is my hope that Aunt Martha will still be enjoying good health, so that I may again see her. With much love for you, I remain your nephew. Silas S. Smith.”[41]

Unfortunately, Silas did not see his beloved aunt again. Martha Ann died at 6:00 a.m. on Friday, 19 October 1923, while “sitting in her chair, making temple aprons, . . . alone with her thoughts.”[42] She had lived to be eighty-two years, five months, and five days. Martha Ann’s son John F. Harris (1872–1946) was the undertaker who took care of the funeral.[43] A local Provo newspaper announced her death in the Friday evening issue, identifying her as an “honored pioneer woman.”[44]

Beyond her family and friends, Martha Ann was almost always identified as being the sister, daughter, or niece of an important leader in the Church. In death that did not change. When other newspapers in the state announced her death, it was always in relationship to her famous family.[45] Martha Ann had lived in the shadow of her well-known brother, Joseph F., and they both had lived in the shadows of their famous parents, Hyrum and Mary Fielding. Martha Ann was proud of her family and most likely would not have been surprised by the newspaper headlines announcing her death. She had lived most of her life away from the limelight and chose to focus her service on family, friends, neighbors, and the Church ward where she lived.

The funeral was held in the Provo Tabernacle on Monday afternoon, 22 October 1923. The Provo Sixth Ward bishop, Joseph Nelson, conducted the service, with members from the Provo Tabernacle Choir singing five beautiful compositions, including two Restoration hymns—“When First the Glorious Light Burst Forth in This Last Age” and “O My Father”—and a final hymn often sung at funerals, “I Know My Redeemer Lives.”[46] A delegation from Church headquarters, including Apostles George Albert Smith and Joseph Fielding Smith, Church Patriarch Hyrum G. Smith, and Presiding Bishopric counselor David Smith, came to honor Martha Ann. In addition to representing the Church, they also represented Martha Ann’s extended Smith family in Salt Lake City.

Local stake and ward leaders, family, friends, and neighbors also filled the Provo Tabernacle on Monday afternoon. George Albert Smith told those attending, “It will be strange to come to Provo and not find Aunt Martha here. She was one of the most remarkable women who has ever lived.”[47] He added, “Without much help from the outside she has carried burdens that would have crushed one less courageous. She was always devoted to someone else.”[48] Following the funeral, Martha Ann was buried next to her husband in the Provo City Cemetery.

Memorial marker for William Jasper Harris and Martha Ann Smith Harris, Provo City Cemetery, photograph by Brent R. Nordgren, July 2018. Courtesy of Brent R. Nordgren. For many nineteenth-century Americans, their memorial markers were one of the few written records of their lives. Fortunately, Martha Ann wrote and saved letters and told stories handed down through her posterity, allowing her life to be reconstructed and preserved.

Memorial marker for William Jasper Harris and Martha Ann Smith Harris, Provo City Cemetery, photograph by Brent R. Nordgren, July 2018. Courtesy of Brent R. Nordgren. For many nineteenth-century Americans, their memorial markers were one of the few written records of their lives. Fortunately, Martha Ann wrote and saved letters and told stories handed down through her posterity, allowing her life to be reconstructed and preserved.

In less than two months, a notice of Martha Ann’s passing was published in the Church’s monthly women’s publication, the Relief Society Magazine, as an editorial titled “Martha Ann Smith Harris.” The short announcement concluded, “Happily for us and happily for future generations, the sons and daughters of the great patriarch, Hyrum Smith, have given to the world a very large and honorable family of children and grandchildren, so that while we are no longer privileged to have among us the sons and daughters of one of the first founders of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, we still have with us many of their descendants.”[49]

A month later, in January 1924, a much longer article was published in the Relief Society Magazine[50] to help people beyond Provo, including Martha Ann’s extended family, to become more acquainted with “one of the most remarkable women who has ever lived.”[51]

Both Joseph F. and Martha Ann left large families and also a precious written record of their lives. It is apparent that the letter collections of Joseph F. and Martha Ann reveal more about his life and concerns than hers—a function of not only the greater quantity of extant Joseph F. letters but also the different content of his letters consistent with his different role in the sibling relationship. He was the elder brother who, as solicitous father figure and benefactor concerned about the welfare of his beloved Martha Ann, had wisdom, counsel, and encouragement to impart in an effort to lighten the burdens she carried. He also had missionary experiences and other adventures to report on that were largely foreign to Martha Ann’s experience and station in life. It comes as no surprise, then, that the trove of letters between them can seem one-sided in key ways. First, Joseph F. is in the spotlight. Second, Martha Ann is often relegated to the roles of either grateful recipient of her brother’s watchcare or primary source of family news. Because Martha Ann almost never provides her older brother counsel or direction for his life or the lives of his family, the reader may rashly assume that Joseph F. thought his life was nearly perfect and that only Martha Ann faced challenges requiring encouragement, advice, or admonition from concerned family members.

The Joseph F. and Martha Ann letter collection provides a view of their personal interaction. They were bound by blood, but also by their devotion to the restored gospel of Jesus Christ and to the Church their parents had supported until the end of their lives. From the martyrdom of their father, Hyrum, in 1844, and the death of their mother, Mary Fielding, in 1852, they continued to strengthen each other through visits and letters. To Martha Ann, her brother was “my truest most faithfull friend,”[52] and to Joseph F., she would always be “My Dear beloved Sister Martha Ann.”[53]

Notes

[1] Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 29 January 1861, herein.

[2] Joseph F., journal, 13 May 1874.

[3] Joseph F., journal, 12 May 1874.

[4] Joseph F., journal, 13 May 1874.

[5] The law of adoption was an ordinance generally performed in Latter-day Saint temples between 1846 and 1894 in which men who held the priesthood were sealed in a father-son relationship to other men who were not their biological offspring. It is generally assumed this practice occurred because many early adult converts did not have fathers who were members of the Church. See Gordon Irving, “The Law of Adoption: One Phase of the Development of the Mormon Concept of Salvation,” BYU Studies 14, no. 3 (Spring 1974): 291–314.

[6] Joseph F. to Andrew Borgesen, 14 November 1883. In the end, Joseph F. advised the man to consider being sealed directly to Hyrum.

[7] Rudger Clawson, journal, 26 February 1901, as quoted in Stan Larson, ed., A Ministry of Meetings: The Apostolic Diaries of Rudger Clawson (Salt Lake City, UT: Signature Books, 1993), 248.

[8] Clawson, journal, 26 February 1901, as quoted in Larson, Ministry of Meetings, 249.

[9] Clawson, journal, 26 February 1901, as quoted in Larson, Ministry of Meetings, 249.

[10] Clawson, journal, 26 February 1901, as quoted in Larson, Ministry of Meetings, 250.

[11] Clawson, journal, 26 February 1901; as quoted in Larson, Ministry of Meetings, 250.

[12] Joseph F. to Lorenzo Snow, 28 February 1901.

[13] Joseph F. to Joseph E. Taylor, 16 November 1907.

[14] Joseph F. Smith, “At Rest in Christ,” Latter-day Saints’ Millennial Star 69, no. 22 (30 May 1907): 337–49.

[15] Smith, “At Rest in Christ,” 338.

[16] “Patriarchal Blessing of Joseph F. Smith, 1852.”

[17] Joseph F. Smith, Gospel Doctrine: Selections from the Sermons and Writings of Joseph F. Smith, comp. John A. Widtsoe, 5th ed. (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1939), 658.

[18] Charles C. Goodwin, “The Pioneers,” Goodwin’s Weekly, 8 April 1916, 1.

[19] Kenney, “Before the Beard,” 21.

[20] See Ricks, “My Candid Opinion,” xi–xxii.

[21] There is no contemporary account of this incident. Joseph F.’s 1850s Hawaiian missionary journals end on 20 October 1857, when he was sailing home, before the encounter took place on the mainland; and his next journal did not begin until 27 April 1860, when he started on a mission to England. Because of this gap in the record, this story is based on secondary sources by those who presumably heard Joseph F. recount it. A version of the incident appeared within two months of Joseph F.’s death (see Charles W. Nibley; “Reminiscences of President Joseph F. Smith,” Improvement Era, January 1919, 192). Another version, used here with slight variations from Nibley’s account, was published a few months later (see Smith, Gospel Doctrine, 657). Joseph Fielding Smith, who preserved another version in his book Life of Joseph F. Smith, repeated the story to his children and grandchildren so often that they could easily repeat it verbatim years later (Vivian McConkie Adams, Joseph Fielding McConkie, and Mary McConkie Donoh, interview, 6 July 2013). As New Testament scholars have often observed, in such stories inconsequential variations should be expected while the core remains consistent (see, for example, J. D. G. Dunn, Jesus Remembered: Christianity in the Making, Volume 1 [Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2003]).

There are at least two letters in which Joseph F. used similar phrases found in the earliest versions of the story. The first reference—“I tell you martha they are going to flud the world with ‘true blue’ or with true borne ‘Mormons’ and I’m glad to here it”—appears in Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 15 February 1856, herein. The second reference—“I hope the boys will do well on their mission and will return ‘true-blue’ thoroughly ‘died in the wool’ Latter Day Saints, besides doing a good work”—appears in Joseph F. to Alma L. Smith, 29 March 1882. For a detailed analysis and discussion of the earliest versions, see Nathaniel R. Ricks, “True Blue, Depending on Who’s Telling the Tale: The Redacted Story of Joseph F. Smith and the ‘Ruffians,’” The Juvenile Instructor: Organ for Young Latter-day saint Scholars, 12 November 2013, https://

[22] Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 18 March 1885, herein.

[23] Ina Coobrith to Bio De Casseres, Adele T. De Casseres correspondence, 1910–1927.

[24] Forty-three children were born to Joseph F. and his five wives. He also adopted two additional children and invited Alice Ann Kimball’s three children from a previous marriage to become part of his family once he and Alice married in 1883. Some reminiscences from his children are found in Norman S. Bosworth, “Remembering Joseph F. Smith: Loving Father, Devoted Prophet,” Ensign, June 1983, 20–24.

[25] Joseph F. Smith, “Appreciation and Gratitude,” Improvement Era, August 1918, 861–62.

[26] See “Prest. Smith Is Called by Death,” Deseret Evening News, 19 November 1918, 2.

[27] We acknowledge Stephen C. Taysom’s insights on this important point.

[28] See, for example, Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 23 December 1912, herein.

[29] Richard P. Harris, “Martha Ann Smith Harris,” Relief Society Magazine, January 1924, 18.

[30] “Daughter of Martyred Patriarch of Church Paid Final Tribute,” Deseret News, 22 October 1923, 3.

[31] Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 22 May 1890, herein.

[32] Following Joseph F.’s death, Martha Ann was deprived of his financial help. It was fortuitous that Martha Ann had obtained a monthly pension of twelve dollars (based on William Jasper’s service in the Utah Militia Cavalry during the 1865–1872 Black Hawk War) beginning on 4 March 1917. She had been assisted by Senator Reed Smoot in obtaining the pension. See “No. 10,561 Pension Certificate of Martha A. Harris Payable Monthly by the Disbursing Clerk, Bureau of Pensions. Group 3. United States of America Bureau of Pensions.” Courtesy of Carole Call King. The pension was based on the Congressional Act of 4 March 1917 to help veterans of the “Indian Wars” during the nineteenth century. See “An Act to pension the survivors of certain Indian wars from January first, eighteen hundred and fifty-nine, to January, eighteen hundred and ninety-one, inclusive, and for other purposes,” Statutes of the United States of America Passed at the Second Session of the Sixty-Fourth Congress, 1916–1917 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1917) 2:1199.

[33] Wallace Stegner, one of the first to recognize Latter-day Saint women’s contributions, observed, “That I do not accept the faith that possessed them does not mean I doubt their frequent devotion and heroism in its service. Especially their women. Their women were incredible.” See Wallace Stegner, The Gathering of Zion: The Story of the Mormon Trail (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1964), 13.

[34] Richard W. Etulain, Beyond the Missouri: The Story of the American West (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2006), 159.

[35] Harris, “Martha Ann Smith Harris,” 18.

[36] “Provo,” Deseret News, 21 May 1921, section 3, vii.

[37] “Provo,” Deseret News, 21 May 1921, section 3, vii.

[38] According to one version of the story, Martha Ann “participated as a pioneer in the celebration in Salt Lake City in 1922 for the 75th anniversary of the pioneers’ arrival, when This is the Place monument was dedicated” (in editors’ possession). This memory cannot be completely relied on since the monument was dedicated by President George Albert Smith on 24 July 1947, more than twenty years after Martha Ann’s death in 1923. See “50,000 Attend ‘This Is the Place’ Site Ceremony,” Deseret News, July 24, 1947, 32.

[39] “Glowing Tribute Is Paid Pioneers at Big Banquet,” Salt Lake Telegram, 23 July 1922, 9.

[40] “Pioneer Program at Saltair Beach Monday,” Deseret News, 22 July 1922, iv.

[41] Silas S. Smith to Martha Ann, 9 September 1923.

[42] Eva Maeser Crandall, “A Trip on Memory Ship,” 7, BYU.

[43] Martha Ann Harris’s Death Certificate, 1 November 1923, Utah Department of Health. In a note to Joseph F., John F. Harris used his business letterhead, “Funeral Director and Licensed Embalmer, Depot Street, Burial Caskets Funeral Supplies.” John F. Harris to Joseph F., 20 September 1916.

[44] “Death Calls Aged Woman,” Daily Herald (Provo), 19 October 1923, 1.

[45] See, for example, “Niece of Prophet Jos. Smith Dies,” Ogden Standard-Examiner, 20 October 1923, 1; and “Joseph Smith’s Sister Claimed,” Salt Lake Telegram, 20 October 1923, 5.

[46] “Funeral for Aged Woman,” Daily Herald (Provo), 22 October 1923, 1.

[47] “Daughter of Martyred Patriarch of Church Is Paid Final Tribute,” Deseret News, 22 October 1923, 3.

[48] “Daughter of Martyred Patriarch,” 3.

[49] “Martha Ann Smith Harris,” Relief Society Magazine 10, no, 12 (December 1923): 592.

[50] See Richard P. Harris, “Martha Ann Smith Harris,” Relief Society Magazine, January 1924, 11–18.

[51] “Daughter of Martyred Patriarch,” 3.

[52] Martha Ann to Joseph F., 31 May 1874, herein.

[53] Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 21 June 1869, herein.