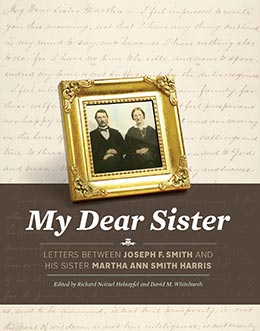

Approaching and Understanding Joseph F.'s and Martha Ann's Letters

Richard Neitzel Holzapfel and David M. Whitchurch, "Approaching and Understanding Joseph F.'s and Martha Ann's Letters," in My Dear Sister: Letters Between Joseph F. Smith and His Sister Martha Ann Smith Harris, ed. Richard Neitzel Holzapfel and David M. Whitchurch (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2019), li–lii.

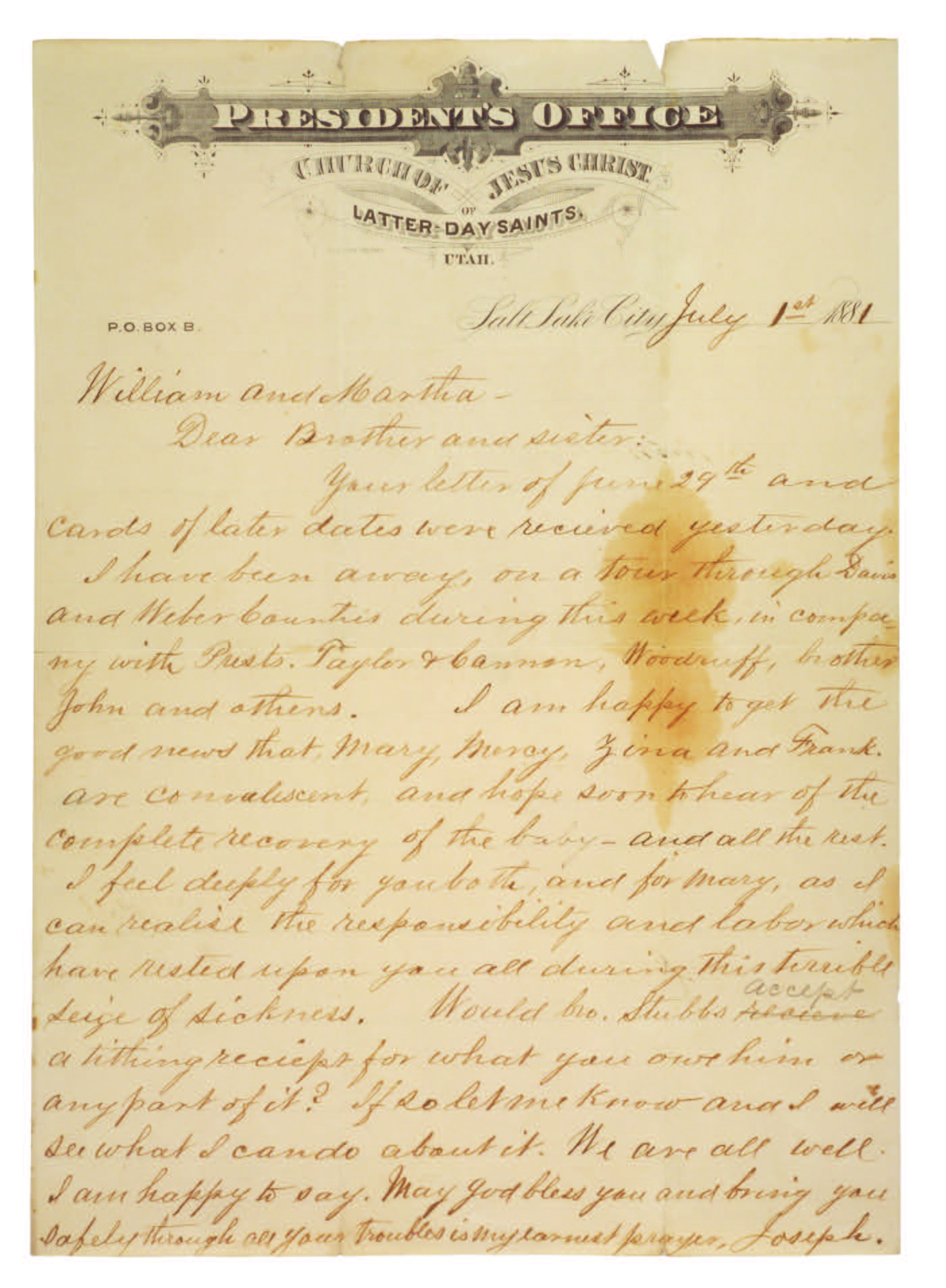

Joseph F. to William and Martha Ann, 1 July 1881 (p. 1)

Joseph F. to William and Martha Ann, 1 July 1881 (p. 1)

Reading Joseph F.’s and Martha Ann’s letters is to enter a new world—the historical past. The past is like a foreign country in many ways.[1] In Joseph F.’s and Martha Ann’s letters we find ourselves in a completely different place and time where we encounter people, practices, and ideas that we may not understand. We may be challenged by unfamiliar geographic place-names not easily placed on our mental maps. Additionally, we may be less familiar with the time line of the letters (1850s–1910s) than with the Joseph Smith period (1805–44) or with recent Church history—the time in which we live.

Unlike a narrative history, this collection of letters does not contain a story line. The letters, like the letters of Paul found in the New Testament, are preserved without historical context, introductions, or explanations. Joseph F. and Martha Ann did not imagine people living in the twenty-first century reading their letters and as a result did not always provide the kind of information we need today to understand them and their situation.

Many of the letters are preserved in isolation. In this sense, we are hearing only half the conversation, much like listening to someone at the market who is talking on a mobile phone as she or he stands in line at the cash register. By tone and sometimes by what is said, we can fill in the gaps, but for the most part we are at a loss to fully understand the conversation.[2]

Because many of Joseph F.’s and Martha Ann’s letters are lost, we do not have access to the full conversation. Additionally, we miss much of the conversation going on outside the letters—conversations Joseph F. and Martha Ann were having in person and through family and friends. Joseph F.’s journals provide us only some of those interactions. To meet these challenges to some degree, we have provided a historical introduction for each decade and, where possible, annotations identifying the people involved, what was taking place, and where the events occurred in order to establish a context for the letters written during that period.

We also face the challenge of setting aside the version of Joseph F. we have already created in our minds and allowing the sources to challenge our assumptions about him and his world.[3]

Finally, and most importantly, most people living in Western society today face a common problem when examining the past—presentism. One definition of presentism is “uncritical adherence to present-day attitudes, especially the tendency to interpret past events in terms of modern values and concepts.”[4] In historical analysis, presentism is often identified as the anachronistic introduction of present-day ideas and perspectives into interpretations of the past. Modern historians seek to avoid presentism in their work because they consider it a form of cultural bias and believe it creates a distorted understanding of their subject matter.[5]

Lynn Hunt, former American Historical Association president, argues that presentism does much damage to our understanding of the past: “Presentism, at its worst, encourages a kind of moral complacency and self-congratulation. Interpreting the past in terms of present concerns usually leads us to find ourselves morally superior; the Greeks had slavery, even David Hume was a racist, and European women endorsed imperial ventures. Our forebears constantly fail to measure up to our present-day standards. This is not to say that any of these findings are irrelevant or that we should endorse an entirely relativist point of view. It is to say that we must question the stance of temporal superiority that is implicit in the Western (and now probably worldwide) historical discipline.”[6]

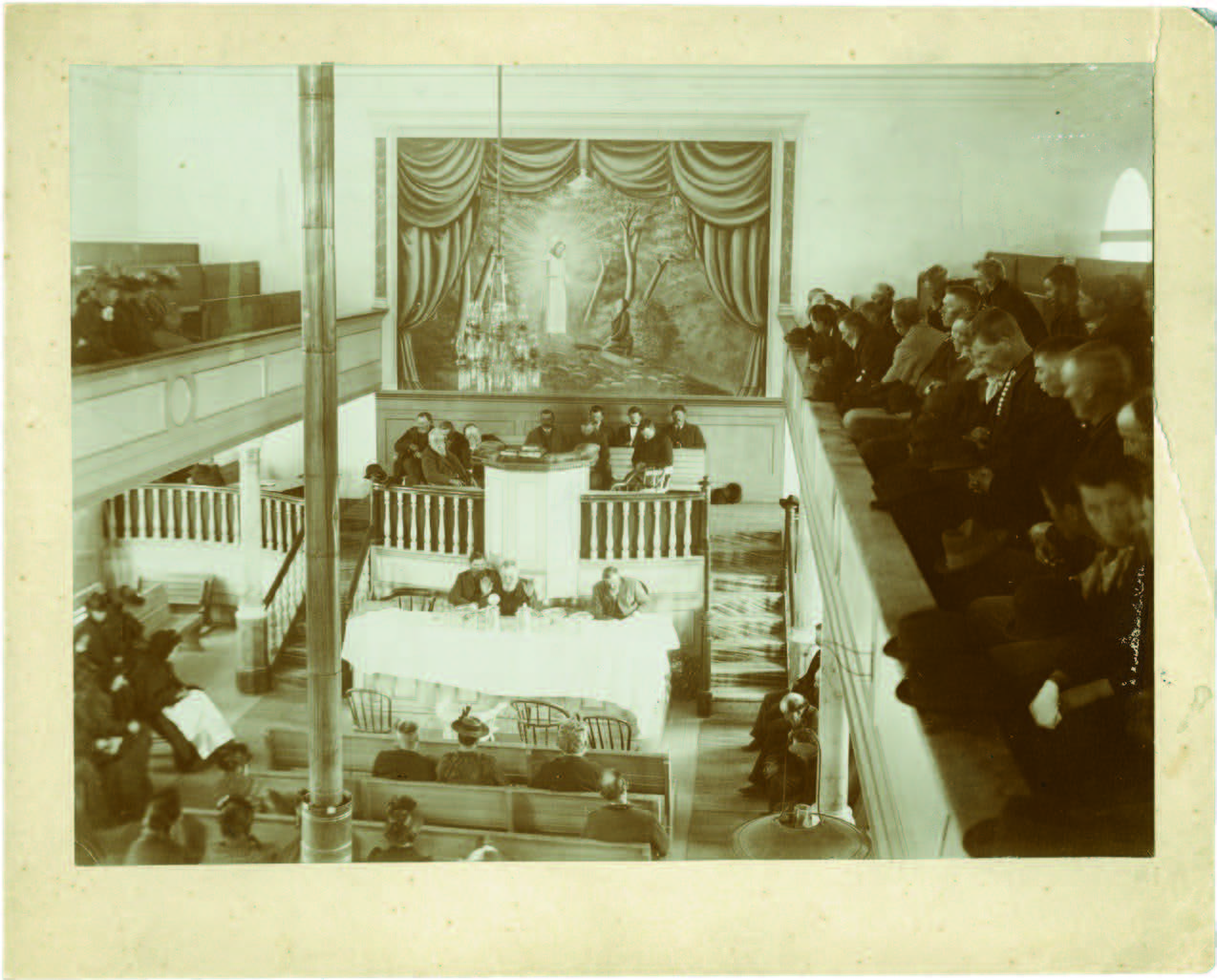

Interior view of the Ephraim Tabernacle, ca. 1895, photograph by Matson and Christensen, Ephraim, Utah. Unlike Church practice today, during most of Joseph F.’s and Martha Ann’s lives the sacrament was administered by mature men, with the acting priest uplifting both hands as he offered the prayers, as highlighted in this view of the Ephraim North Ward sacrament meeting. Additionally, wine was generally still used as a symbol of Christ’s blood, and the practice of first offering the emblems to the presiding leader had not been firmly established. Although the symbolism remains the same, much has changed in the practice over time. Courtesy of CHL.

Interior view of the Ephraim Tabernacle, ca. 1895, photograph by Matson and Christensen, Ephraim, Utah. Unlike Church practice today, during most of Joseph F.’s and Martha Ann’s lives the sacrament was administered by mature men, with the acting priest uplifting both hands as he offered the prayers, as highlighted in this view of the Ephraim North Ward sacrament meeting. Additionally, wine was generally still used as a symbol of Christ’s blood, and the practice of first offering the emblems to the presiding leader had not been firmly established. Although the symbolism remains the same, much has changed in the practice over time. Courtesy of CHL.

Hunt’s warnings are especially relevant today with an almost unlimited access to historical sources found online—often without context by someone who does not have the academic credentials to illuminate the proper context. This approach is almost like visiting the Roman Forum (Forum Romanum) without an authoritative academic guidebook or personal archeological and historical training. To make matters worse, visitors often are accompanied by guides who have no academic training—they have been trained only in guiding people to the major tourist sites in Rome. The tourist is bewildered with the ruins and will more likely than not draw incorrect conclusions and interpretations for what he or she sees in this remarkably rich archaeological site. The experience would be much different if the tourist had studied Roman archaeology or was accompanied by someone who had a PhD in Roman history and/

In the end, we discover thoroughly interesting and passionate people who lived in a time very different than our own. Joseph F. and Martha Ann were not twenty-first-century Latter-day Saints. They believed in many of the core teachings and principles contained in the restored gospel of Jesus Christ. However, they would not naturally feel completely comfortable walking into a three-hour-block Church meeting—some things would be familiar, but much of the experience would be just as foreign to them as it would be for us to walk into a Church meeting in 1886.

Latter-day Saints affirm, “We believe all that God has revealed, all that He does now reveal, and we believe that He will yet reveal many great and important things pertaining to the Kingdom of God.”[7] In this sense, we should expect early Latter-day Saints to have a different understanding of certain religious practices, policies, and doctrines and also how one lives a Latter-day Saint life (the practice of plural marriage, temple adoptions, gathering to specific locations, and so on). Martha Ann and Joseph F. did not interpret the Word of Wisdom the way we do today, they did not experience temple worship the same way we do today, and they did not see the world through the same lens we use today. Their cultural attitudes about women, minorities, children, and other religious faith traditions are significantly different from our cultural attitudes.

Instead of judging them on how we see the world today, a better approach may be to sympathize and empathize with them as they walk through life without many of the conveniences, advances, and understandings we enjoy today.

When we choose to celebrate their victories, both small and large, we may understand them better. It is best to remember that a future generation will see us as having lived in the past, and they will see and experience things in ways we cannot even imagine.

Notes

[1] Many people living in Western democratic industrial nations may have a difficult time reconstructing a world with different cultural, political, religious, and social points of view. For example, nineteenth-century attitudes about a husband’s legal right to administer corporal punishment to family members, including wives and children, and a schoolteacher’s legal rights to punish students would surprise most modern readers.

[2] An example is found in a letter written by Joseph F. Smith to Martha Ann in 1875: “Such things as you mention as having occurred at South Willow Creek, are of almost daily occurrence in this country. But that does not lessen the horror of such abominable wickedness.” Without Martha Ann’s letter, we are unable to reconstruct the events and exact location mentioned in Joseph F.’s response to the letter. See Joseph F. to Martha Ann, 31 March 1875, herein.

[3] See Stephen C. Taysom, “The Last Memory: Joseph F. Smith and Lieux de Mémoire in Late Nineteenth-Century Mormonism,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 48, no. 3 (Fall 2015): 1–23.

[4] English Oxford Living Dictionaries; see https://

[5] It is not an act of presentism, however, to hold people in the past accountable for their poor choices when those choices were noted by people in the past. See W. Paul Reeve, “‘To Save This Fallen Race’: Orson Pratt and the Debate over Indian Indenture and Black Servitude at the 1852 Utah Territorial Legislature,” unpublished paper delivered at the Mormon History Association Conference, 8 June 2018. Latter-day Saint Apostle and Utah territorial legislator Orson Pratt, for example, called slavery a “great evil” in 1852 and argued that black men be allowed to vote in Utah Territory. It is not presentism to suggest that those who opposed Pratt were on the wrong side of history, because Pratt made that very point in 1852.

[6] Lynn Hunt, “Against Presentism,” Perspectives on History, May 2002, https://

[7] Articles of Faith 1:9.