Struggling to Take Root

Organizational, Media, and Social Challenges

James A. Toronto, Eric R Dursteler, and Michael W. Homer, "Struggling to Take Root: Organizational, Media, and Social Challenges," in Mormons in the Piazza: History of the Latter-Day Saints in Italy, James A. Toronto, Eric R. Dursteler, and Michael W. Homer (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2017), 315-350.

In September 1968, two years after the mission’s reestablishment, the missionary force in Italy stood at 163 and church membership had reached 353.[1] With a steadily increasing number of members and branches, and with better trained missionaries beginning to arrive, issues of establishing the church on a sound organizational footing began to occupy more of mission leaders’ time and attention. The freewheeling, autonomous style of missionary work gave way gradually to a more systematic approach reflecting the exigencies of managing a growing organization, standardizing mission practices, and ministering to the temporal and spiritual needs of a diverse membership. Issues of developing local leadership, finding suitable space for meetings, obtaining necessary legal clearances, and providing administrative and teaching materials took center stage. As the church continued to expand, reaction in the media to Mormon presence in Italy intensified, and problems in retaining converts hampered church growth.

Correlation and Italianization

One of the themes during this time in mission history is a tightening and increasing centralization of church organization. Mission records indicate that, beginning in 1968, supervisors and specialists from church offices in Salt Lake City and Frankfurt came to Italy more frequently to orient mission staff on current church policies and procedures. The buzzword was “correlation,” a term that reflected the church’s effort to manage explosive growth worldwide by standardizing vital administrative tasks such as planning, leadership training, missionary strategies and methods, acquisition and maintenance of physical facilities, financial and statistical reporting, and production and distribution of curriculum materials.

The manuscript history, for example, notes that in April 1968 an official from the Church Building Committee came to the mission office, where he remained for several days “to aid . . . in planning for future growth.” Two weeks later the office staff submitted the Correlated Report to church headquarters, thus bringing the mission in line with the Church Correlated Reporting system. In November 1968, members of the Primary General Board and the Relief Society General Board from Salt Lake City visited Italy to train mission and local leadership. Numerous other entries provide evidence of the process of organizational reform that was initiated churchwide during the late 1960s—changes that would shape missionary work and church administration for decades.[2]

In a lay religious community like the LDS Church, with no professionally trained clergy and no institutions for preparing new leaders, a challenge to rooting the organization in unfamiliar terrain was developing indigenous leadership. The presence of local leaders carried several advantages: mission leaders and missionaries could focus on missionary work rather than administrative concerns, it would help to dispel the image of the church as a foreign organization, and it would facilitate interaction with local, regional, and federal Italian institutions as the church sought to establish itself in Italy’s public space. Therefore, identifying and training Italian converts who could assume responsibility for the day-to-day oversight of church affairs was a high priority for mission leaders. This effort reflected the overall church strategy for integrating the church as rapidly as possible in newly opened areas around the world.

Interior view of the sparsely furnished apartment, located in Piazza Vescovio, 3, that served as the LDS chapel in the early days after missionary work opened in Rome. Courtesy of Noel Zaugg.

Interior view of the sparsely furnished apartment, located in Piazza Vescovio, 3, that served as the LDS chapel in the early days after missionary work opened in Rome. Courtesy of Noel Zaugg.

Shortly after the organization of the mission, Duns formed a mission council consisting of members and missionary leaders to help make decisions and set goals. His intent was to administer the mission like a stake, with the council providing overall supervision of church affairs. The council’s mandate was to institutionalize as many church programs as possible, including home teaching, family home evening, member-missionary work, priesthood correlation, Relief Society, Primary, and the Mutual Improvement Association. In cases where experienced Italian members could not be found to supervise the programs, missionaries or American members were temporarily appointed to serve on the council. Initially sister missionaries supervised the Primary and the wives of the mission presidents or a sister missionary had oversight for Relief Society. During the early years of the mission, the pressing need to train leaders for the women’s and children’s auxiliary organizations prompted mission leaders to request that church headquarters in Salt Lake City start sending missionary couples and more sister missionaries to Italy.

Both Duns and Christensen sought every opportunity to move Italians into leadership positions and, as much as possible, to accommodate their ideas and leadership styles. They made a concerted effort to send young Italian converts on missions to prepare them to serve as future leaders for the church. Italians were appointed to serve alongside missionaries in presidencies at the district, branch, quorum, and auxiliary levels in order to learn firsthand the principles and procedures of church administration. The early strategy of establishing Italian branches adjacent to American servicemen’s units provided opportunities for local converts to interact with experienced church leaders and observe church government in action.

Portable baptismal fonts constructed of metal of PVC piles and plastic were an important innovation in missionary work, facilitating the process of conversation and baptism by immersion in urban areas. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Portable baptismal fonts constructed of metal of PVC piles and plastic were an important innovation in missionary work, facilitating the process of conversation and baptism by immersion in urban areas. Courtesy of Church History Library.

The mission sponsored special leadership seminars and training sessions at the quarterly member conferences held in conjunction with missionary zone conferences. These leadership seminars provided training for branch leaders to perform priesthood assignments and ordinances, such as baptizing and confirming new members. Local leaders were given a general outline of how to conduct church meetings but told to adapt it as needed. Mission leaders wanted them to use their own initiative in applying the basic principles they had been taught to solving administrative problems and strengthening the membership base.

At times the outlines and procedures were altered in response to recommendations made by local Italian leadership. Duns described his approach to fostering local leadership and solving problems: “Most of the discussions and problems were of a joint effort, mostly using ideas resulting from remarks and ideas from the Italian members. I wanted their ideas. . . . Even the missionary, he had to think Italian, he had to be Italian, and if you could get an Italian to express himself . . . then we tried his ideas.”[3] In Duns’ estimation, the involvement of local members in discussion, decision making, and planning helped them in their homes and personal lives too. The focus on lay participation and collaborative problem solving had the added advantage, especially with the younger members of the church, of attracting greater involvement in activities and in strengthening the personal commitment of new converts.

As soon as Italian members had adequate experience, missionaries were released to focus on missionary work and the pool of local leaders began to deepen and assume greater responsibility for church affairs. An important step forward in this regard was the appointment of Leopoldo Larcher to serve as second counselor to Duns: his presence in the mission presidency sent a powerful symbolic message to Italians that one of their own could lead the church, and on the practical side, his assignment to work specifically with local members and to develop new leaders helped jumpstart the process of Italianization.

Physical Facilities and La Bella Figura

One of the most challenging issues in consolidating the presence of the church in new areas was providing physical facilities to support the growing religious community. The first church meetings held in Italy in the 1960s were low-key and simple in nature. Normally they took place in the living room of a member’s home or in a small chapel or schoolroom on a NATO military base. After Italy was reopened to missionary work in 1965, Sunday gatherings were often held in the cramped space of a missionary apartment where beds and tables were pushed aside to make room for a few chairs. The establishment of the mission in Italy in August 1966 opened up greater access to church resources and accelerated the pace of acquiring suitable space and equipment to accommodate an increasing number of converts and investigators.

For several reasons, the mission adopted a policy of renting meeting space on the ground level of apartment buildings. At a practical level, ground-floor space allowed easy access to meetings without using stairs or elevators and could accommodate the set-up requirements for the new portable baptismal fonts that were being installed throughout the mission. Oftentimes the missionaries used the meeting hall’s main windows, located along the public sidewalk, to display church literature and to attract walk-in contacts for teaching. The rationale also took into account contemporary political sensitivities: meeting at ground level provided a more transparent setting that would avoid arousing the suspicion of government authorities concerned during this era about Communists and other potentially subversive groups holding closed, secretive meetings.

As the number of missionaries, converts, and investigators increased and new cities were opened, the amount of time and financial resources spent by mission leaders in developing physical facilities expanded rapidly. There was constant pressure to locate, acquire, and furnish new meeting places or to enlarge and renovate existing space (which was the preferred option when possible). Duns and Christensen were keenly aware of the emphasis in Italian culture on maintaining la bella figura (attractive outward appearance) and the consequent difficulty of attracting and retaining Italian converts if the public face of the new religious movement lacked a modicum of aesthetic appeal.

Much effort, therefore, was expended in turning the stark meeting halls into chapels that were simply but attractively appointed. Stands and pulpits were designed by the missionaries and built by local carpenters; pianos and organs were rented or purchased; walls were replastered and painted; curtains (often sewn by local members) were installed on the windows and religious pictures hung on the walls; attractive displays were set up in the entryway of each chapel. Working in a country and among a population boasting some of the world’s most splendid religious art and architecture, mission leaders knew they could not compete with the Catholic Church. But they also knew that even the most committed Italian converts would be hard pressed to invite friends and family to a church that did not provide a minimally suitable public setting.

Another pragmatic issue involved providing accessible and functional baptismal facilities. Early baptisms were typically performed at a secluded beach, a local river or lake, a swimming pool, or a mountain stream dammed up to form a pool. This proved impractical during the cold winter months and due to the continued increase in the number of conversions in urban areas. The problem was solved by designing and contracting out the construction of portable baptismal fonts, the first of which were introduced to the missionaries at a conference in February 1968. Through his contacts at Fiat, Duns arranged for the fonts to be manufactured by the Pirelli and Michelin companies and then shipped to and installed in every Latter-day Saint meeting place. The fonts consisted of a steel frame supporting a large plastic tub, about four feet high and eight feet wide, with a stepladder and an electric coil to heat the water. The fonts were not without problems, including the potential of water leaking into lower floors or their weight causing the floor to collapse. On one occasion missionaries reported that while filling a font in their upper-floor apartment the floor began to sag ominously. They filled the font only partially and completed the baptism, but only with much anxiety and with strict instructions that everyone in attendance stand around the outside of the room with their backs to the wall.

While a small innovation, mission leaders felt that the installation of the portable baptismal fonts was a boon to missionary work. The convenience of holding baptismal services in the regular chapels meant that baptismal services could be attended by larger numbers of family, friends, and investigators. The impact of the simple but impressive rite of initiation—with participants dressed in white and accompanied by singing, short talks, and bearing of testimonies—was often instrumental in defusing the prejudice and concern of converts’ families and of reinforcing the commitment of members and investigators.[4]

Early Legal Issues for the Church in Italy

Provisions in both the Italian constitution and Vatican II documents created a favorable juridical and social climate for the introduction of new religious movements in post-war Italy. Moreover, the personal relationships that Benson and Duns had with high-ranking government officials helped smooth the way for the church’s reorganization in Italy. When local officials did challenge the missionaries about their activities, the questions were generally not about the legality of their presence as foreigners preaching a new religion, but whether they had complied with government stipulations to register their names with the Questura, obtained permits to put up displays and hold meetings in public, and avoided competing with local businesses in showing movies and selling books door-to-door.

There were times when officials at the city and parish levels collaborated to impede or prevent the proselytizing activities of Mormons, Jehovah’s Witnesses, and other new religious movements by imposing unwarranted bureaucratic obstacles and delays. But without a legal foundation for opposing missionary work and with good relations between church leaders and government officials in Rome, the impediments created by local officials were dealt with quickly and turned out to be minor annoyances in an overall open and tolerant Italian religious economy.

There are numerous examples of how favorable laws, increasing acceptance of non-Catholic groups, and positive personal relations facilitated the removal of obstacles during this time of transition to religious pluralism in Italian society. The ministry that supervised religious affairs, according to the agreement reached with Benson (which was consistent with the government’s rules concerning long-term visas), required all Mormon missionaries to register with the Questura upon their arrival in a new city, renew their registration every three months, and inform authorities when they left to serve in another city. But the large volume of transfers and constant movement among the missionaries made it virtually impossible for both government and mission officials to keep up with these bureaucratic procedures. So Duns worked out an arrangement with the ministry in Rome that the mission office would send a report every three months with a list of all the missionaries and where in Italy they were located. Missionaries still had to register and carry a permit or they could be detained for questioning by police, but the new system required less red tape and fewer time-consuming visits to the Questura.

Although it was not necessary to ask for ministry approval to open a city to missionary work, sometimes city officials would temporarily prohibit proselytism when missionaries arrived in town, explaining that they had first to write or telephone the official in charge of religious affairs in Rome for approval. But because Duns knew the minister, he was able to inform the local magistrates that they could contact Rome for verification if they desired, but that the church already had the necessary approval from the ministry. This approach seemed to deflect resistance and reduce or eliminate stalling tactics.

While there were no legal restrictions on proselytizing activities, in the early phase of missionary work Italian officials in some cities required the missionaries to obtain permits to go tracting because they were selling copies of the Book of Mormon. Their reasoning was that if roving salesmen needed licenses to sell their goods door-to-door, then Mormon missionaries should be placed under the same obligation. Eventually, as local officials began to realize that the missionaries were not selling books for profit, but distributing religious tracts either free or (in the case of the Book of Mormon) at cost, they dropped the requirement.

Christensen noted that the task of keeping the government apprised of missionary movements was a complex and daunting one but that ministry officials appreciated their diligent efforts to cooperate: “The Italian government tried to keep track of the location of each missionary. The local Carabinieri (policemen) were the source of control, and an office in the Italian government at Rome was the focal point. A missionary being transferred was supposed to check out with the local Carabinieri upon departing and to check in with them at the city where he or she was reassigned. The Carabinieri funneled their information to the office in Rome,” called the Office of Cults and Sects.[5]

Sometimes the missionaries forgot to check in or asked others to do it after leaving. Once Christensen was called by an official from that office and asked for a fresh list of where each missionary was because the existing lists were outdated. “He mentioned several who had long since departed for the USA. Others were not where his records indicated they should be.” Christensen drove to the government office to deliver the list, and the officer looked it over and thanked him. “He then turned to me and asked, ‘Do you have some sort of ceremony which changes a person into a Mormon?’ I said, ‘Yes, you bet. When individuals are deemed worthy and ready we baptize them by immersion in water.’ He asked, ‘Well, what kind of people are available who would accept such a change?’ I said, ‘Catholics, there aren’t many others in Italy.’ He thought about it for a moment and then said, ‘Well, you are not the biggest church in Italy but you are by far the best organized.’”[6]

Indeed, the perceptive Italian bureaucrat had put his finger on one of the traditional strengths of church growth: its strong organizational capacity. Over time this distinctive feature of Mormon outreach, together with a commitment to building cooperative relations with government officials and a philosophy of “going in the front door,” became decisive in the church’s push to achieve full legal integration in Italy. [7]

Translation and Publication of Mission Materials

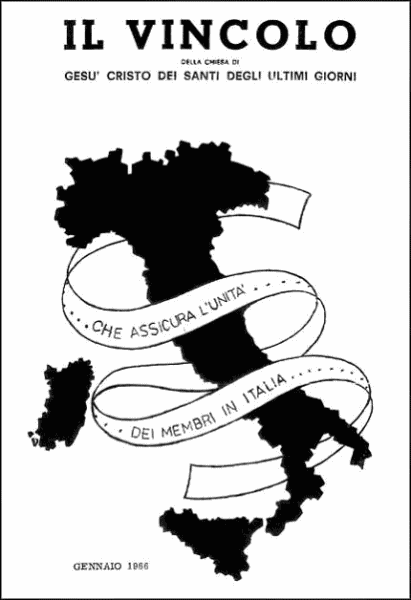

A significant challenge in the early years of the church was the social and geographical isolation of converts and the need to help them feel part of a larger religious communion. One of the main methods for helping members and missionaries stay connected with each other was the publication of newsletters and church materials. The earliest publication, Il Vincolo (The Bond) appeared even before the reopening of missionary work in August 1965. While president of the Italian District of the Swiss Mission, Leavitt Christensen, working with his wife, Rula, supervised the writing and translation of this newsletter by missionaries. Copies were then printed on a mimeograph machine in a spare bedroom of the Christensen home and mailed to the Italian members scattered across the peninsula. This rudimentary epistle was the only contact that many members had with the church before missionaries arrived in their area.

Cover of the newsletter Il Vincolo (The Bond), an early church publication that circulated in Italy before the reopening of the mission in 1966. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Cover of the newsletter Il Vincolo (The Bond), an early church publication that circulated in Italy before the reopening of the mission in 1966. Courtesy of Church History Library.

In April 1966, members of the Brescia Branch assumed responsibility for publishing this newsletter in order to free up missionaries to proselytize and “to make sure it gets done in good Italian and in a manner that will attract investigators.”[8] For two years Il Vincolo remained the main source of curriculum materials translated into Italian for Primary, Relief Society, Sunday School, and Mutual lessons. The church’s Frankfurt office assumed responsibility for its printing and mailing in 1967, although some members experienced long delays in receiving the newsletter because of incorrect addressing.

Beginning in June 1967, the mission office in Florence began publishing a monthly Italian-language magazine called La Stella (The Star). The next year production of this magazine was subsumed under the church’s new Unified Magazine system and the first five hundred copies of the official Italian-language church magazine came off the presses in Frankfurt in March 1968.[9] In October of that year the mission began issuing Il Dirigente (The Leader), a monthly bulletin for Italian branch officers and teachers containing messages from the mission presidency and auxiliary leaders on a mission level.

The first professionally published issue of the Italian church magazine La Stella (The Star) in March 1968. It shows the front entrance of church headquarters, 47 E. South Temple, Salt Lake City. Courtesy of James Toronto.

The first professionally published issue of the Italian church magazine La Stella (The Star) in March 1968. It shows the front entrance of church headquarters, 47 E. South Temple, Salt Lake City. Courtesy of James Toronto.

Shortly after the reopening of the mission, the office staff began producing a newsletter designed primarily to facilitate communication of information and provide opportunity for training and motivating missionaries who had only sporadic contact with mission leaders. Deciding on a suitable name for the newsletter turned out to be more problematic than anticipated, and a contest was held to name the newspaper. The first two issues of the weekly mission publication carried the name Ci Manca Un Nome (We Need a Name), then in quick succession during September several names were adopted and discarded: the Challenger, Il Messaggio (The Message), and the Weekly Reader. In September the name Il Pioniere (The Pioneer) was selected but was dropped a few months later when it was discovered that a publication of the Italian Communist Party carried the same name. In December and January, the titles included Il Lo, The Trumpeter, The Trumpet, and Life Line. By the end of February 1967, mission staff had finally settled on The Trumpet as the official title of the mission publication.[10]

During his tenure as mission president, Duns put Christensen (his counselor in the mission presidency) in charge of a major initiative to increase the number of church publications and curriculum materials available in Italian. At the time of the mission’s organization in 1966, only the Book of Mormon, the missionary handbook, and a few church tracts had been translated into Italian. It appears that this push in the Italian Mission coincided with an accelerated churchwide effort to address the growing demand for supplies and equipment during a time of rapid international expansion. This was part of an effort to centralize administrative tasks, including translation and distribution of curriculum materials. The Church News reported in late 1966 that an expanded translation program was underway throughout Europe “to make Church literature and material available to non-English-speaking membership at the same time it is available to English-speaking members.” This effort was to be accomplished, in part at least, through volunteer efforts by local members.[11]

J. Thomas Fyans, director of the Translation Department, and other administrators from Salt Lake City and Frankfurt began holding seminars with mission leaders and translators throughout Europe. In a seminar held in Italy, the director of translations from Frankfurt described the importance of translated materials to missionaries and members. The purpose of the department, he said, was “to relieve the mission presidents of the responsibility of translating, printing and distributing the materials essential to the various church organizations.”[12]

In the spring of 1967, Christensen participated in a conference held in Copenhagen that brought together leaders from church headquarters and translation coordinators from nine European countries. He later observed that it “sounded like the conference that was held just before all the people left the Tower of Babel” and described some of the problems encountered: “We’re really having a time trying to get all the church material translated into Italian. There are people translating from French to Italian, German to Italian, Spanish to Italian, and English to Italian. Some of the stuff was translated from French to Spanish to Italian. Most of my translators are non-members. We were lucky to find them and probably it is only because there are so many here around the American base [Camp Darby] that we could get those who spoke good English.” His plan was to have twenty translators working soon, including reviewers and typists, to produce Italian translations of church publications and audiovisual materials such as films, filmstrips, and slides.[13]

To meet burgeoning translation needs in Italy, the mission began holding a series of training seminars at various venues in northern Italy. During these conferences member and non-member translators met with officials from Frankfurt and with Duns and Christensen to coordinate their efforts and to resolve problems in the translation and distribution process. Christensen characterized the problems as a dearth of trained personnel, particularly members, and bottlenecks that keep materials from being ready on time.

Most of the translators hired by the mission were non-member Italian civilian employees at Camp Darby, the American base in Tirrenia where Christensen worked: “The people who have been working here at the base do the best job because they have learned a great deal of American-type English and idiomatic expressions. They don’t know doctrine well, however, and the reviewers have to be extra careful to keep out pagan talk.” A mother and her two daughters worked on the family home evening and adult Aaronic Priesthood lessons: “The girls do the translating and mamma types it up. She is the foreman of the crew and keeps them producing.” Christensen found a couple of men working in the bank at Camp Darby who worked together to translate the Relief Society lessons, but they struggled to turn in their work on time “since the bank personnel work long hours and these people don’t have much time or energy after a day at the bank.” All administrative forms (tithing and donation receipts, certificates, report forms, and so forth) were translated by Pietro Currarini, who proved to be skilled and efficient and later became head of the translation department in the mission. In all, there were twelve translators scattered around Italy (plus one in Salt Lake) in addition to several reviewers and typists. “It is sort of a hodgepodge arrangement,” Christensen concluded, “but we are slowly grinding out the most essential material.”[14]

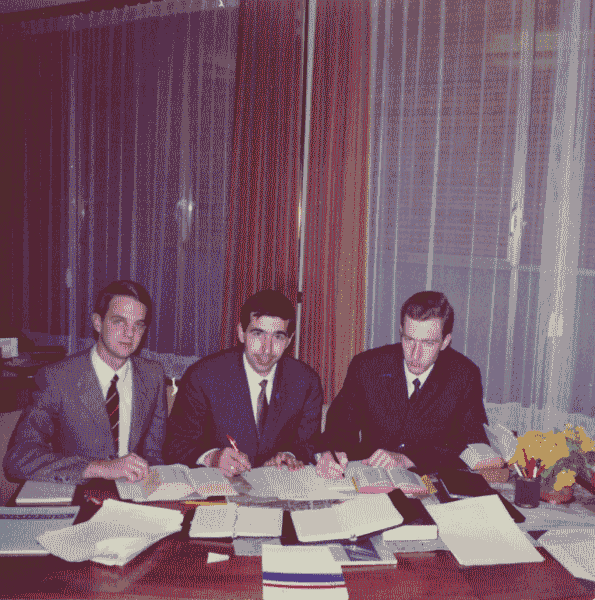

In a room at the Swiss Temple in Zollikofen, in June 1970, Leopoldo Larcher (center) and missionaries Dan Steurer (left) and Peter Lauener (right) translated the temple endowment into Italian. Courtesy of Church History Library.

In a room at the Swiss Temple in Zollikofen, in June 1970, Leopoldo Larcher (center) and missionaries Dan Steurer (left) and Peter Lauener (right) translated the temple endowment into Italian. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Meetings between representatives of the translation department in Frankfurt and mission leaders normally centered on how to improve the quality of materials and how to eliminate bottlenecks in the system such as customs clearance at the Italian border. Officials from Frankfurt expressed exasperation at the “the many difficulties they faced in an endeavor to bring the [twenty-two] tape recorders and [twenty-three] filmstrip projectors across the line from Switzerland to Italy.”[15] The timely distribution of supplies around the mission continued to challenge the office staff. An entry in the mission history for January 1970 notes that an employee from the Printing and Distribution Center in Frankfurt arrived in Florence with a car load full of much-needed supplies. The mission had “been without pamphlets and Books of Mormon for some time,” and it required the intervention of Hartman Rector Jr., a member of the church’s First Council of the Seventy, to achieve this breakthrough in the bureaucratic impasse.[16]

Participants in a seminar held in Florence in May 1967 also discussed concerns about the quality and accuracy of the translation of the 1964 edition of the Book of Mormon. Many of the early Italian converts found the translation to be inelegant and even inaccurate in places, and so efforts were launched to improve the quality of the language. The decision was made to print a new run of the 1964 edition to supply the immediate demands, and then to retranslate and publish a new edition. This initiative “would be put into the cycle as fast as the available help could be obtained.”[17]

According to the seminar report, other materials slated for translation or already in process included flannel board strips (being translated in Salt Lake City), the “Golden Book” missionary door approach tool, flip book pictures sent from the South German mission, the missionary handbook and study chart, and the Italian Press Book (for teaching missionaries how to deal with the Italian media). A church hymnal in Italian did not yet exist, and so several missionaries with musical background translated fifty-two hymns and had them printed. While there had been a delay in translating the temple ceremony into Italian, Duns noted that there would be Italian members ready for the temple ordinances by August (1967) and a number of missionaries “capable and talented” in Italian to assist with the translation of the ceremony.[18]

In July 1967, Francisco Rial, a missionary from South America who spoke English, Italian, French, Spanish, and Portuguese, was assigned to the mission office in Florence and designated to take over translation duties from Christensen, who was scheduled to return to the United States in November. Duns felt that Rial’s linguistic expertise would help relieve the bottleneck caused by a high volume of translation work and limited personnel for reviewing. Christensen noted that “[Rial’s] arrival was timed just right and he says that he feels it was why he was sent on his mission.”[19] Among other things, Rial was assigned to go through the existing translation of the Book of Mormon in Italian and make revisions in preparation for a new edition. The mission established an Office for Italian Reviewers, and Elder Rial and his companion moved to Livorno to live in closer proximity to the bulk of the translation team. Within a year or so, however, the church’s program of correlation and centralization eliminated the need for mission presidents and missionaries in Italy to shoulder these administrative tasks, allowing them to focus more on finding and strengthening converts.

All in all, the vital process of preparing, reviewing, publishing, and distributing Italian language materials was a laborious one, fraught with delays, setbacks, and frustrations. Despite its halting progress and ad hoc nature, however, an essential foundation was laid that strengthened the resolve and identity of converts during this tenuous period in Italian church history before the more sophisticated, centralized church correlation and translation programs was established. A letter from John Carr, supervisor of the translation department in Frankfurt, to President Duns acknowledged the contributions of these early translators, whether members, non-members, or missionaries: “We too are amazed at the amount of work which is being turned out. . . . I don’t know of a situation in Europe that to me is more inspiring and thrilling to contemplate than the work that’s being done in your Mission.”[20]

Italian Press Reaction to the Growing Mormon Presence

In a Church News article published in August 1966, about two weeks after the reestablishment of the mission, Ezra Taft Benson observed that “the Church is on the map” in Europe and credited Italian news media for providing coverage of church growth and “greatly aiding its proselyting program.”[21] A sampling of articles that appeared in the Italian press in the months following the organization and rededication of the mission supports that assertion.[22] The content and tone of coverage in the press indicate that Italians were curious about the growing presence of the LDS church in their midst but that they also reacted with fascination, amusement, and annoyance at the implausibility of a new religion like Mormonism—which they viewed as an obscure and bizarre American sect—attempting to insert itself in Italy’s religious space. Sometimes press coverage resulted from the missionaries’ tactic of paying a visit to local newspaper offices and introducing themselves to reporters and editors, but normally it came as an unsolicited effort on reporters’ part to simply do their job of covering news and events in society.

In general, Italian journalists were professional in their coverage, attempting to represent the doctrines and history of the church with objectivity and accuracy, despite occasional factual errors that occurred from relying on secondary source material. They sometimes offered the church a chance to print a response. Several themes emerge in the press coverage of LDS evangelism in Italy: Mormonism’s historical ties to the American frontier and polygamy; the LDS dietary and health code (Word of Wisdom); the volunteer and lay aspect of LDS experience; and the perception of the church as an American religious movement with vast financial resources. A survey of press coverage in the late 1960s provides insights into both the challenges faced by Mormon missionaries in dealing with Italian biases and stereotypes and the internal issues that Italians were grappling with as their society encountered an array of new, competing products in the religious marketplace.

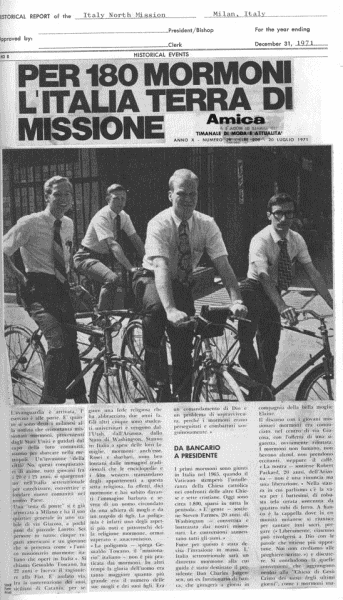

The weekly magazine Amica, published in Milan, featured missionaries in their signature white shirts on its cover shortly after a second mission was created in July 1971. The "vanguard" of 180 missionaries has arrived the journalists observes, and "the army is at the doors." Courtesy of Church History Library.

The weekly magazine Amica, published in Milan, featured missionaries in their signature white shirts on its cover shortly after a second mission was created in July 1971. The "vanguard" of 180 missionaries has arrived the journalists observes, and "the army is at the doors." Courtesy of Church History Library.

On 18 September 1966, a popular weekly magazine in Vicenza, Domenica del Corriere, published an article by Cesare Marchi, “A Family of Sicilians Has Become Mormon.”[23] Later that month the mission historical report recorded that as a result of this publicity “a literal tidal wave of correspondence flooded into the Mission Offices” requesting more information about the “Mormon religion.” It was one of the earliest attempts in Italian print media (after the second mission was organized) to document the rise of Mormon evangelism and to explore its implications in Italy’s evolving religious climate.[24]

The article describes in detail the curious scene of a Mormon baptism: The Cappitta family was originally from Sicily but lived in Verona. The father, mother, and two children ages eleven and fourteen, barefoot and dressed in white, stood beside a pool of green water in a rock quarry outside the city of Cittadella (near Vicenza). With the Brenta River and piles of gravel as a backdrop and to the accompaniment of trucks rumbling nearby, the Italians and some Americans from the US military base at Vicenza conducted the ceremony, forming a circle and performing the baptism by immersion. The two American missionaries who conducted the simple rite were also dressed in white—two college students who interrupted their studies to enroll in the army of twelve thousand Mormon missionaries who “make propaganda” for their church around the world. In exchange for giving up smoking, alcohol, tea, coffee, and other stimulants, the newly baptized converts became saints.” Moreover, the article states that in the LDS Church, “everyone is considered a priest.”[25]

Amazed that the Mormon missionaries could actually be laboring in the extremely Catholic area of Vicenza, Marchi attributed their presence and ability to find a few converts to the church’s American origins and connections. The reason for this is clear, he opined, when one remembers that the Mormons “make use of that huge psychological and organizational platform provided by the American families” of the nearby US military base.[26] Mormonism’s image in Italy as an American religion and the church’s continual efforts to counter that perception by emphasizing its international character continued to be a persistent theme in Mormon history over the next fifty years.

The article concluded with the reporter’s query concerning “what the Catholic ecclesiastical authority might think about this [LDS] proselytism.” He pointed out that Vatican II “has thrown wide open windows and gates” in Italy for greater circulation of ideas and a more open discussion of the freedom of individual conscience. He interviewed Monsignor Ofelio Bison, director of the Catechistic Office of the Diocese of Vicenza, who with equanimity and candor offered his explanation of Mormon proselytizing success and revealed something of the official Catholic attitude toward new religious movements:

Here the character of the Italians, who love novelties, comes into play a little bit. Then you add to this their scant knowledge of religious doctrine and their minimal knowledge of catechism. For people weak in religion, it is easy to let yourself be pulled off course. Another thing that needs to be added is that these American missionaries are lavish in giving charity and have at their disposal conspicuous financial means. Charitable largesse is an excellent hook (ottimo aggancio) for initiating discourse of a religious nature.

Q: “Is this proselytism at a level today to cause worries?”

A: “I would say no. It doesn’t worry us, but it does cause us pain. [Converts to other faiths] are sheep who no longer return to the fold.”

Q: “What defensive action do you believe the Catholic Church could put into effect to check the [Mormon] offensive?”

A: “It is not necessary to speak dramatically either of offensive or counteroffensive. We cannot coerce the conscience of anyone; everyone is free to choose. We limit ourselves to carrying out our own agenda.”[27]

According to Marchi and Monsignor Bison, then, Mormonism’s attractiveness derived from Italians’ fascination with novelty, their weak foundation in Catholic doctrine, and the beneficence and financial resources available to the missionaries and their converts through their American connections. Mormonism’s image in Italy as an American religion and the church’s efforts to counter that perception by emphasizing its international character continued to be a persistent theme over the next fifty years of mission history.

In December 1966, Cagliari’s Unione Sarda newspaper reported on “another Christian sect for whom we are a mission field” and announced “the arrival of the first missionaries of this strange sect [the Mormons] in Italy” who will soon be knocking on our doors.[28] The Italian fascination with the Mormons’ saga of settling the American West is evident, and the journalist, Fabio Bertini, highlighted the Mormon reputation for hard work and social justice, praising the Mormons as strong pioneers who made the harsh valleys of the Rocky Mountains blossom. He launched into a musing side trip, triggered by the state of Utah, noting that cities, rivers, and mountains had biblical names as do newspaper mastheads and advertising on street benches. The Mormons, who form 90 percent of Utah’s population, commented Bertini, believe that America and Utah are the “new Promised Land, . . . the new Zion” and anticipate Jesus’ Second Coming and millennial reign. It is part of their sacred duty to contribute to social and economic well-being, build churches and public buildings, take care of the poor and the needy, and keep a year’s supply of food and provisions in case of famine.

Bertini also interviewed an unnamed church leader to explain the lay ministry and missionary work. The fact that all young men become priests and that “there is no difference between members and clergy” is an attractive aspect of Mormonism, the official asserted. He described how, by age twenty-one, many young people enter missionary service at their own expense, with support from the local LDS community who raise money by auctioning books, fruit, flowers, pets, candy, and used items. Bertini, with a slightly incredulous tone, summarized: “So the young ‘cowboy’ learns to wear a necktie and low-cut shoes, to preach the gospel, and finally to go on a mission with a companion. . . . These are the people who will soon arrive to knock on our doors. Who would have ever thought [Chi ci avrebbe detto] that even Italy would become a mission field for the Mormons?”[29]

A month later, an article from a newspaper in Bergamo (between Brescia and Milan) described a debate between four Mormon missionaries and a group of local university students. The encounter reflects the ambivalent attitudes that Italians often evinced during this period toward the church and its connection to the United States: curiosity about why the missionaries had come to Italy, admiration for some aspects of American culture, and distaste for US foreign policy and involvement in the Vietnam War. The theme of the debate was “Differences between American and European culture,” and questions that the missionaries fielded from the audience included how they spent their spare time and how US colleges were organized. It was, according to the reporter, an interesting evening during which “the atmosphere heated up” as the exchange of opinions took place. The meeting ended with the missionaries showing slides depicting their life in the United States.[30]

In April 1967, two missionaries visited the offices of the Messaggero Veneto in Udine to introduce themselves and their new faith to the newspaper staff. The resulting article stresses the novelty of having two young Mormon missionaries in town and accurately presents the church’s beliefs, but the tone mixes respect, amusement, and skepticism. The editors of this regional newspaper clearly understood that the incursion and recruitment efforts of new religious groups in the deeply Catholic Veneto was a controversial issue but still felt a professional obligation to report the news objectively.[31]

With its readership’s sensibilities in mind, the article opens with a half-apologetic caveat: that newspapers are a magnet for unusual people and ideas, and the Mormons are making an announcement of something new. The unnamed reporter comments that he had been aware for several days of the two young men of “mystical aspect” who rode motor scooters from street to street and house to house, holding direct discussions about their doctrine with families. Their Italian, he notes, is “characteristic” of foreigners but quite “comprehensible.” In identifying their title as “Elder,” the author wryly notes the irony: “That’s exactly what they said: Elder. And so we see that indeed everything is relative in this world because the first missionary is 25 and the second is even younger so that, adding their ages, it’s not even half a century.”[32]

The article explains that Duns is the presiding officer, that the mission headquarters are in Florence, and where the missionaries in Udine are living, then summarizes their message: “We were interested in knowing what, in particular, one must do to be considered a good Mormon. Here it is: one must not smoke, it is prohibited to drink hot drinks, above all tea and coffee. And wine, we asked, can you drink wine? Oh no, they answered. We drew the conclusion that in the next two years—with all the respect that is due to the message and to the two missionaries—there will not be many Mormons in Udine.”[33]

Shortly after this article appeared, the newspaper La Sicilia reported on Mormon evangelization in Catania but with much less objectivity and restraint. While the basic facts are essentially accurate, the author’s tone is hostile, his prose drips with antipathy and sarcasm, and his interpretation of LDS teachings and missionary work is distorted and sensationalized. The Mormons, he announces, have “come ashore” at Piazza Verga in the heart of Catania and have set up a “trivial [Lilliputian] sacred display” (referring to the missionaries’ street board) on a little plywood table. The subheading states that ten missionaries from Utah and Arizona are attempting to convert others, perhaps with “the mirage of polygamy.”[34]

After a summary of Mormon history, the reporter critiques the Book of Mormon as a literary work lacking “elevated or poetic sentiments,” full of “naive assertions and anachronisms,” and composed in a “monotonous and pretentious” style. The principles of the Mormon Church, he continues, are a “mix of Judaism, Hinduism and Paganism, even Islam: a real muddle (guazzabuglio) of ingredients we find spicy (polygamy), alluring (the Mormon welfare program with indefatigable workers who provide for the poor and needy), and happy (dance halls, choirs, folklore shows, and social gatherings).” The journalist concluded by returning to the theme of polygamy, implying that Mormonism is a pseudo-religion that cannot be taken seriously. It prohibits the use of tobacco, alcohol, tea, and coffee on the one hand, he says, but on the other, it does not disapprove of the fact that Joseph Smith left behind twenty-seven wives when he was assassinated. Clearly, the reporter opines, the Mormons intend to use the allure of polygamy to entice Sicilians, especially men, to convert: “The missionaries, including two women, attempt with this puny exhibit to convert the citizens of Catania. To succeed—because they are in Sicily, land of the ‘womanizers’ [galli, roosters]—they depend on the temptations of polygamy. But this is forbidden by law here, so the galli will have to reject it.”[35]

In May 1967, two Mormon elders met with reporters in Brescia and talked about their experience in Italy, philosophy of seeking converts, religious beliefs, and views on controversial political and social issues. The two elders provided articulate, measured responses to the journalists’ questions. “We’ve been accepted and treated well so far,” the missionaries observed. “We’re not here to impose Mormonism, but to make it known. We believe every person has the right to follow the religion he prefers, to worship what and how he wishes.”[36] The reporters then posed questions of “vibrant currency” in Italy concerning divorce and the war in Vietnam. The missionaries, reflecting mission guidelines on how to respond to volatile questions, offered a discreet response: “We allow divorce although it happens rarely in our church. It would take a long time to explain our position on Vietnam. Many Mormons are in the armed services in Vietnam. We believe that every person and every government must respond in their own way.”[37]

Journalist Crescenzo Guarino wrote a series of three articles that appeared 1–3 March, 1968, in the newspaper Roma under the title “The Mormons: The Bible on Horseback,” giving extensive coverage to the church’s early activities in Italy. President Duns sent copies to Ezra Taft Benson, and the Church News subsequently printed an article with a summary of the articles. A note from Duns to Benson, enclosed with the articles, characterized the reporter’s presentation as “very fair and just” and pointed out that “most of his facts are surprisingly accurate for Italy.” Headings to the articles highlight themes that typically captivated Italian writers and readers: settling the Old West, the practice of polygamy, worldwide evangelism, and an austere code of life that seemed hopelessly incompatible with Italian culture. “The Puritans who prohibit wine and tobacco but appreciate a beautiful woman,” Guarino observed with irony, “hope to convert all of Italy. In the panorama of the minority religions of our country, a new movement has appeared: this North American Protestant faith has sent 18,000 missionaries all over the world.” The third article in the series asks how the Mormon missionaries, who consider coffee an “ungodly sin,” will ever “have luck in a country that, from dawn to dusk, is a steaming coffee pot?”[38]

Left to right: Apostle Thomas S. Monson, Frances Monson, Rula Christensen, and Leavitt Christensen, president of the Italian Mission. Elder Monson supervised missionary work in Italy beginning in 1968, visiting the country numerous times. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Left to right: Apostle Thomas S. Monson, Frances Monson, Rula Christensen, and Leavitt Christensen, president of the Italian Mission. Elder Monson supervised missionary work in Italy beginning in 1968, visiting the country numerous times. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Taken together, these newspaper articles from various geographic regions reflect something of the religious and political ferment that characterized this transitional period in modern Italian history. They show that, in many respects, Italy presented a social and juridical climate conducive to the introduction of new religions. Italians, in spite of their fixation on Mormonism’s association with polygamy and the mystique of the American West, were curious about the activities of the missionaries, open to discussion and debate about religious questions, and impressed by the historical LDS commitment to building prosperous close-knit communities and taking care of the poor.

In other respects, however, the questions and reactions of Italian journalists indicated that the LDS Church’s ability to make a place for itself in Italy’s religious space would constitute a formidable undertaking. Although Mormons and other new religious movements would make some inroads in Italian society, traditional identities and loyalties to Catholicism would see little change over the next several decades. Italian repugnance for Mormonism’s connection to polygamy and its emphasis on a health code and high participation for church members would hinder missionary efforts. The church’s image as an American organization elicited mixed reactions in Italy: Italian fondness for American culture often provided openings for the missionaries, but strong anti–Vietnam War sentiment and widespread sympathy for Communist and Socialist ideologies frequently created tensions.

The “Blossoming of the Rose” in Italy

The inaugural issue of the mission’s monthly Italian-language magazine, La Stella, appeared in June 1967 with the translation of an article by Henry A. Smith, editor of the Church News. In reporting on the progress of missionary work in Italy, he quotes a letter from the mission office staff in Florence that makes the earliest known reference in mission literature to what came to be known as the “rose” prophecy: “Many years ago Lorenzo Snow, an early missionary to Italy, made a prophecy that the day would come when Italy ‘would blossom as a rose’. That day must be here. Just as with a real rose, the growth has started slowly, almost imperceptibly, but it is accelerating rapidly and will soon burst into the splendor of full bloom. We are now in the stage of relatively slow, but sure development. That prophecy is now bearing fruit.”[39] From this first-known mention, the rose prophecy became a recurring theme in subsequent mission discourse, even though documents contemporary with Snow do not mention it.[40]

The sanguine predictions of success made in 1965 by the missionaries when proselytism began anew gradually gave way to a more cautious view based on deeper experience with the surrounding socioreligious reality. Church leaders continued for a time to maintain expectations for growth in Italy based on comparisons to high rates of conversion in other Latin Catholic countries. For example, minutes of a conference held in Rome at Piazza Vescovio 3/

In addition to the constraints noted in the press reaction to the growing Mormon presence in Italy, other factors both within the fledgling mission structure and in Italian society hampered efforts to reintroduce Mormonism in Italy. Mission records indicate that retaining members after their baptism surfaced as a major challenge early in the new mission. Disaffection occurred for a variety of reasons, detailed in chapter 13, that led to a gradual waning of commitment, decreased participation, and, in some cases, open apostasy. When missionaries were transferred to another city, converts often felt abandoned, especially if they had been more attached to the missionary than to the message, and unless other congregants and the new missionaries could connect with them, they lapsed into inactivity.

Family and societal pressures also exerted a powerful influence in determining whether a convert could forge a new religious identity and maintain consistent affiliation in the church. Christensen felt that, in a country with a 95 percent Catholic population, the parish priest had a powerful influence on a convert’s commitment: “It is economically difficult to get along in Italy if you are not of that faith. Italy is a country of small businesses. Their success depends on the support of other local families and especially the local Priests who come around to pronounce blessings upon the business enterprises of the faithful. . . . Many believe our doctrines but have not the courage to face the results of baptism. On the other hand there are many who believe and who have the courage of their convictions.” He added that the Vatican “never indicated, while we were there, that we even existed in Italy. The local Priests in the Parishes, however, were very actively combating what we did.”[42]

After baptism, families of converts to Mormonism continued to pressure them to reconsider, and conflicts arose when meetings were scheduled at the same time as family activities, especially during the week. Family and peers often criticized converts for reduced participation in Italian social life—especially no longer observing Catholic religious rituals and declining such small but significant cultural gestures as accepting a glass of wine, a cup of coffee, or a cigarette from a friend. In some instances, neighbors shunned them, storekeepers gave them a hard time, and employers refused to hire them because of their perceived religious deviancy. Duns commented that members often asked him to write letters of reference for employment in cases where the local parish priest, who traditionally performed this role, refused to help a former parishioner.[43] For these reasons, it became common for missionaries to spend considerable time fellowshipping and reactivating members in addition to recruiting new converts.

As noted earlier, the LDS Church’s reliance on personal development through lay leadership proved attractive to Italians, accustomed as they were to a more passive role in religious life. But finding converts, particularly men, who could make the transition from committed member to deeply involved leader posed problems in the early phase of church development. While many Italian converts adjusted quickly to leadership roles and exhibited commitment and acumen in taking the reins of a branch or auxiliary organization, in some cases tension and instability emerged when novice church leaders imported cultural and personal habits into the church setting. This would lead them to exhibit a style of leadership characterized by authoritarianism and cult of personality.

Within the first three years of the mission’s founding, several Italian leaders were excommunicated for apostasy related to egregious misconduct in their leadership position. Mission records document that elders from the mission office were occasionally dispatched to cities around the mission to meet with a church leader who deliberately ignored church teachings and procedures and defied the admonitions of the mission president. In the most serious cases, a branch president or prominent member disagreed with a church doctrine or policy and rallied a coterie of members to support him against the central church leadership. Sometimes unorthodox doctrines and practices crept in, necessitating action from mission leaders. In other cases, branch presidents and a good share of the branch membership had to be released from their callings and disciplined because they formed organizations and initiated practices that went far beyond church guidelines.

President Christensen cited numerous examples of these problems. One branch president, formerly a Communist, was released from his position and later excommunicated because he openly and insistently advocated that church leaders in Salt Lake City should still be teaching members to live under the United Order, a communal social and economic system practiced by some Mormons during the nineteenth century. In another instance, members in one branch organized a “Good Death Society,” the goal of which was to prepare to die well. This group was holding secret meetings under the direction of the local church leaders. Christensen had to disband the meetings and release leaders from their callings.[44]

Zone leaders, following a conference at the newly purchased mission home in Rome, loading publications in their cars and receiving last-minute instructions from President and Sister Christensen. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Zone leaders, following a conference at the newly purchased mission home in Rome, loading publications in their cars and receiving last-minute instructions from President and Sister Christensen. Courtesy of Church History Library.

In an article to all church members in Italy, published in La Stella in June 1971, Christensen wrote at length on the problem of false doctrines and practices that must be eliminated. He reviewed what revelation is, to whom it is given, and under what circumstances it is received. Apparently, some converts had approached him and other mission leaders with their own revelations about how the church should be run and what its doctrine should be. He cited examples in newer branches where members and investigators claimed to have had visions and had been possessed by multiple spirits. He warned the members to stay away from “idle amusements” such as magicians, soothsayers, and others who experiment with the powers of the devil and cautioned them against associating with individuals who felt the need to create tales in order to get attention. These problems, Christensen concluded, were especially harmful in small branches with many new members, and therefore members were advised to be grateful but discreet in sharing with others God’s personal revelations.[45]

Another persistent challenge was that investigators and converts frequently asked missionaries for assistance to emigrate to the United States despite the clear church policy that members should remain in their own countries. While many Italians during the 1960s may have had an aversion for the Vietnam War and other aspects of US foreign policy, they were also generally enamored with American life and culture. There was already a long tradition of US aid to Italy and Italian emigration to the US that forged strong economic, social, and political ties between the two countries.[46] The church’s image as an American religion with American leaders and missionaries compounded the problem of converts seeking to emigrate. In his oral history, Duns stated, “we did everything we could to stop that from happening” to help the church grow in Italy. He and other mission leaders reminded the members that everything needed to enjoy the blessings of the restored gospel is ‘right here for you with your own people.”[47]

In spite of the church’s policy and the efforts of mission leaders to keep members in Italy, over the years a sizable number of converts emigrated and settled in other European countries and the United States, especially Utah. They often attended church-sponsored schools or married LDS spouses—in many cases, returned missionaries who served in Italy. It is also true that many converts who were attracted to the Mormon Church hoping for better economic opportunities or finding an American spouse discontinued their participation in the LDS community when those hopes went unfulfilled. As we note in a later chapter, issues of migration would continue to impact church growth in both positive and negative ways, whether internal migration of church members to other cities in Italy, external migration to other countries, or the conversion of immigrants from other countries residing in Italy.

The End of “Chapter One”

Mission headquarters moved from Florence to this villa at Via Cimon 95, in the Monte Sacro neighborhood of Rome, in September 1970. Courtesy of James Toronto.

Mission headquarters moved from Florence to this villa at Via Cimon 95, in the Monte Sacro neighborhood of Rome, in September 1970. Courtesy of James Toronto.

By early 1969, significant changes in mission leadership had occurred. Leavitt Christensen, who had served as first counselor in the mission presidency, had left Italy in October 1967 and was replaced by Dan Jorgensen, an American banking executive working in Milan. In an unexpected turn of events, President Duns attended a mission presidents’ seminar in Germany on 15 February 1969 and, upon his return to Florence, announced that he had been released. He was replaced temporarily by Hartman Rector Jr., who had been assigned to work with Elder Thomas S. Monson. Duns offered no specific explanations for his release, which came five months before the end of his three-year tenure, except to say that his wife was having some health problems and that Rector, as a new General Authority, needed some firsthand experience in the mission field. Rector served for about six weeks before Leavitt and Rula Christensen returned in March 1969 to assume the presidency of the mission. The mission office staff held a testimony meeting to welcome the Christensens and the first “greenies” who had received training in Italian at the Language Training Mission at BYU. Both the Christensens and the new missionaries had arrived in Florence on the same day.

By 1970, due to growth in the number of missionaries and converts, and with pressing leadership and logistical issues to address, the mission had become more than one president could handle. Another factor that strained mission resources was the sheer geographic and demographic size of the country: a long-distance drive of about one thousand miles (1,600 kilometers) from the north border to the south border, and a population of approximately fifty-six million people.

Christensen made this point with Elder Monson, his supervisor in the Quorum of the Twelve: “I produced a map of Europe and placed a compass point on the North border of Italy and stretched it out so that the pencil point was at the South end of Italy. We then drew a circle with Italy as the radius. On the far end of the circle the pencil passed through the center of England and then through the Scandinavian countries. Monson said, ‘That is too big.’” Monson did not have the authority to unilaterally divide the mission, but he asked Christensen to start looking for a new mission home in Rome. “It was obvious that with two missions one would be in the North and one in the South,” explained Christensen. “The major airports were at Milan and Rome. This factor would facilitate the arrival and departure of missionaries.”[48]

In a letter to their family in January 1970, Leavitt and Rula Christensen sounded upbeat about the progress of the mission, the commitment of members and missionaries, and the prospects for future growth:

There is a spirit of expectancy here and everyone, members and missionaries, seem to feel the spirit of the Lord working on the people of Italy. We are getting in places and receiving successes that a year ago were not dreamed of. We have had nationwide television coverage which was very favorable and the publicity received from that has had a terrific impact on our ability to get into places. . . . We have a great mission, and the spirit is very high. Everyone is hot for baptisms and there is very little goofing off any more. But it has taken a lot of work and confidence building.[49]

Beginning in the spring of 1970, the Christensens looked diligently for a building in Rome that would serve as both a mission home and offices. When summer came, they had still found nothing suitable: sites were too close to the airport, or under the flight pattern, or on a busy street, or inadequate in size and shape. When it became too burdensome to be living in Florence and looking for real estate in Rome, they assigned the task to the zone leaders in Rome. The zone leaders found a villa that the Christensens visited and liked. Monson came as soon as he could and gave the stamp of approval:

He walked in the door, viewed the lower floor rooms, ascended the marble stairway to the bedroom area and on up to the third floor. When he returned he said, “This is the building the Lord wants us to have as a mission home.”. . . The sellers wanted the building preserved and were willing to sell to us at a lower price in order to do so. When we first went to see the owner and seller he produced a copy of the Improvement Era in which was shown pictures of the rooms in one of the LDS temples. He said that he had faith that his home would be in good hands with such an organization.[50]

The headquarters of the Italy Mission were moved from Florence to the new villa at Via Cimone 95 in Rome’s Monte Sacro neighborhood on 7–9 September 1970. At first, the church rented the villa; but on 15 October 1971, the purchase was confirmed with the owners, represented by Signora Maria Luisa Piergili Benagiano, and the money was wired from the LDS offices in Frankfurt. After the transfer was complete, the group “went to a nearby café to toast the event with a glass of orange juice.”[51]

Christensen reported in March 1971 that, after six years of proselytizing in Italy, nineteen cities had active missionary teams in Italy with 1,452 members organized into twenty-five Italian branches and four servicemen’s groups.[52] Annual baptismal figures indicated an upward trend in church growth: membership had nearly tripled since 1967, with 92 baptisms that year, 193 in 1968, 288 in 1969, and 365 in 1970.[53] Based on these figures, mission leaders projected 500 baptisms during 1971, and on 24 April of that year, amid the optimism generated by steady growth and positive publicity for the church in the national media, came the much-anticipated announcement. The Italy Mission would be divided into Italy North and Italy South, beginning 1 July, with Dan Charles Jorgensen as the president of Italy North and Christensen continuing as president of Italy South.[54]

Mission leaders referred to the division of the mission as an important milestone. At conferences held in Milan and Rome in May 1971, Monson challenged the missionaries to close out “Chapter One” of the “Great Italy Mission” in grand fashion by baptizing a hundred persons during May and June.[55] This nascent phase of LDS evangelization in Italy laid the foundation for a period of rapid expansion in the 1970s and early 80s, followed by three decades of slower growth but increasing maturity and stability within the church and greater acceptance and integration in Italian public life.

Notes

[1] Jack E. Jarrard, “Gospel Is Taught in Italy,” Church News, 2 November 1968, 3.

[2] For more detailed discussion of the Church’s expanding correlation and administrative programs during this period, see chapter 7 of Gregory A. Prince and Wm. Robert Wright, David O. McKay and the Rise of Modern Mormonism (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2005).

[3] John Duns, interview, 63.

[4] Duns, oral history, 9–10, 19; Christensen to family, Easter 1967. Duns noted that he got the idea of using portable fonts from the France Mission.

[5] Leavitt Christensen, files, clippings, and other memorabilia relating to his mission experience, 1969–93, “Papers 1960–1989,” MS 13473, Church History Library.

[6] Leavitt Christensen, files, clippings, and other memorabilia relating to his mission experience, 1969–93, “Papers 1960–1989,” MS 13473, Church History Library.

[7] “Going in the front door,” a phrase attributed to President Gordon B. Hinckley, refers to an approach that involves adopting transparent, legal means in entering new countries rather than resorting to surreptitious methods.

[8] Leavitt Christensen, journal, 11 April 1966; “History of the LDS Church in Italy, Swiss Mission, for the Years 1962, 63, 64, 65 and 66,” 1992, MS 13412, Church History Library.

[9] In January 2000 La Stella was combined with other non-English church magazines and renamed the Liahona. See “Publications,” Italy Rome Mission, CR 4142-20 vol. 4, “La Stella,” and Leavitt Christensen, “Papers 1960–1989,” MS 13473, Church History Library.

[10] Copies of these publications in James Toronto’s possession, courtesy of Rodney Boynton. The L. Tom Perry Special Collections at Brigham Young University has some copies of the mission newsletter.

[11] “An Enlarged Translation Program Is Under Way,” Church News, 24 December 1966, 11.

[12] Leavitt Christensen, minutes of meeting held 7 October 1967, “Papers 1960–1989,” MS 13473, Church History Library.

[13] Leavitt Christensen, letter, Easter 1967, “Papers 1960–1989,” MS 13473, Church History Library.

[14] Leavitt Christensen, letter, circa 1 October 1967, “Papers 1960–1989,” MS 13473, Church History Library.

[15] Christensen, official mission correspondence, 1966–68, “Papers 1960–1989,” MS 13473, Church History Library.

[16] “Italian Mission Manuscript History,” 24 January 1970, in Historical Report, 31 December 1970.

[17] Christensen, official mission correspondence, 1966–68, Christensen Papers.

[18] Christensen, official mission correspondence, 1966–68, Christensen Papers. Duns noted that, before the Italian translation of the temple ceremony was available, “members would go to a German or French session and have someone translate into Italian.” Oral history, 55. Mission records indicate that a team consisting of an Italian member and two missionaries—Leopoldo Larcher, Dan Steurer, and Peter Lauener—completed the translation at the Swiss Temple in June 1970. “Italian Mission Manuscript History,” 11 June 1970, in Historical Report, 31 December 1970.

[19] Christensen, letter, circa 1 October 1967, and official mission correspondence, 1966–68, Christensen Papers.

[20] John Carr to Duns, 3 December 1967, in Leavitt Christensen, official mission correspondence, 1966–68, “Papers 1960–1989,” MS 13473, Church History Library.

[21] Ezra Taft Benson, quoted in “Church Is on the Map,” Church News, 27 August 1966, 6. Soon after the August 1966 organization of the Italian Mission, the Church employed a clipping service, “L’Eco della Stampa,” in Milan that sent photocopies of articles on Mormonism from newspapers around Italy to the mission office.

[22] The newspaper articles analyzed in this section are part of a large file of articles we have assembled from a variety of sources, primarily mission archives and histories. The specific articles discussed here are located in “The Italian Mission (1966–71), Manuscript History and Historical Reports,” LR 4140-2, Church History Library.

[23] Cesare Marchi, “Una Famiglia di Siciliani Si E’ Fatta Mormone,” Domenica del Corriere, 18 September 1966, copy in “Italian Mission Manuscript History, Quarterly Historical Report,” 30 September 1966.

[24] “Italian Mission Manuscript History, Quarterly Historical Report,” 30 September 1966.

[25] Marchi, “Una Famiglia di Siciliani.”

[26] Marchi, “Una Famiglia di Siciliani.”

[27] Marchi, “Una Famiglia di Siciliani.”

[28] Fabio Bertini, “I Mormoni alla Porta,” Unione Sarda, 7 December 1966, also published under the name of Fabio Pierini on 14 December 1966, in Corriere del Ticino (Lugano) with the subtitle: “Un’altra Setta Cristiana per la Quale Siamo Terra di Missione,” copy in “Italian Mission Manuscript History, Quarterly Historical Report,” December 31, 1966.

[29] Bertini, “I Mormoni alla Porta.”

[30] “Dibattito fra Studenti al Circolo Bocconiano,” Giornale di Bergamo, 27 January 1967, copy in “Italian Mission Manuscript History, Quarterly Historical Report,” 30 September 1967.

[31] “I Mormoni in Città,” Messaggero Veneto-Udine, 6 April 1967, copy in Italian Mission Manuscript History, Quarterly Historical Report, 31 December 1968.

[32] “I Mormoni in Città.”

[33] “I Mormoni in Città.”

[34] “I Mormoni in Piazza Verga: ‘Mostra Sacra’ su una Tavoletta di Compensato,” La Sicilia, 18 April 1967, copy in “Italian Mission Manuscript History, Quarterly Historical Report,” 30 September 1967.

[35] “I Mormoni in Piazza Verga.”

[36] Sergio Castelletti, “A Brescia Due Missionari Mormoni: 35 Proseliti al ‘Verbo’ di Smith,” Brescia Notte, 24 May 1967, copy in “Italian Mission Manuscript History, Quarterly Historical Report,” 31 December 1968.

[37] Castelletti, “A Brescia Due Missionari Mormoni.”

[38] Crescenzo Guarino, “The Mormons: The Bible on Horseback,” Roma, 1–3 March 1968, summarized in “Italian Paper Tells Story of the Church,” Church News, 30 March 1968, 7.

[39] La Stella 1, no. 1 (June 1967), in “Italy Rome Mission, Publications,” CR 4142-20, vol. 4, Church History Library. For translated excerpts, see Henry A. Smith, “As We See It: From the Church Editor’s Desk,” Church News, 4 March 1967, 6. See also Henry A. Smith, “As We See It: From the Church Editor’s Desk,” Church News, 27 May 1967, 6, in which he again alludes to the rose prophecy in describing the reopening of missionary work in Torre Pellice: “Indeed, say reports, Italy seems to be blossoming like a rose in the very city where missionary work was started so long ago.”

[40] We have been unable to locate evidence that Snow ever uttered the phrase, well-known and oft-repeated by Italian members and missionaries during the second mission, “Italy will blossom as the rose.” The phrase “blossom as the rose” does appear in his pamphlet, The Voice of Joseph, 16, quoting Isaiah 35:1, referring, however, not to Italy but to the manner in which the Mormons transformed the Great Salt Lake valley into productive land. Also, while reflecting on where to begin his mission to Italy, Snow stated that “they [the Waldensians] appeared to my mind like the rose in the wilderness.” The Italian Mission, 10. On several occasions, though, he and other missionaries did express optimistic views about the future of the Mormon Church in Italy but in a different language. During the 19 September 1850 dedicatory event, the following prophecies were recorded: Snow: “The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, now organized, will increase and multiply, and continue its existence in Italy till that portion of Israel dwelling in these countries shall have heard and received the fullness of the Gospel.” Stenhouse: “From this time the work will commence, and nothing will hinder its progress; and before we are called to return, many will rejoice, and bear testimony to the principles of Truth.” Woodard: “The opposition which may be brought against this Church will, in a visible and peculiar manner, advance its interests; and the Work of God will at length go from this land to other nations of the earth.” The Italian Mission, 16.

[41] Thomas S. Monson, minutes of the member conference held at Piazza Vescovio 3/

[42] Leavitt Christensen, “Italian Mission Presidency,” #8: Files, clippings, and other memorabilia relating to his mission experience, 1969–93, Christensen Papers. Scholars have also noted the divergence of interests between the Vatican and the local Catholic churches in Italy: “The Vatican is not identical with the Catholic Church. . . . The growing difference between the concerns of the Vatican and the concerns of the Italian Catholic hierarchy is one of the major developments in this area in recent years.” Paul Furlong, “The Changing Role of the Vatican in Italian Politics,” in Luisa Quartermaine and John Pollard, eds., Italy Today: Patterns of Life and Politics (Exeter: University of Exeter Press, 1987), 66.

[43] Duns, oral history, 29, 50–51.

[44] Christensen, interview.

[45] Leavitt Christensen, “Editoriale del Presidente della Missione,” La Stella 4, no. 6 (June 1971): 189–90.