Strife, Despair, and a Spirit of Emigration, 1852-55

James A. Toronto, Eric R Dursteler, and Michael W. Homer, "Strife, Despair, and a Spirit of Emigration, 1852-55," in Mormons in the Piazza: History of the Latter-Day Saints in Italy, James A. Toronto, Eric R. Dursteler, and Michael W. Homer (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2017), 81-104.

Following Lorenzo Snow’s final departure from Italy, Jabez Woodard expanded the mission outside the Waldensian valleys. The missionaries began preaching in Turin, where they attracted the attention not only of government officials but also of Catholics and Protestants, who were dismissive of their activities in the kingdom’s capital city. Later, the missionaries ventured to Genoa, the second largest city in the Kingdom of Sardinia. But they had little success outside the Waldensian valleys and thereafter focused most of their energies working with the families and friends of church members. While proselytizing efforts continued to find some success among the Waldensians, most of the active members left the valleys, bound for Utah to gather with the Saints.

Into the Plains of Piedmont and the Coasts of Liguria

Jabez Woodard left Malta shortly after 28 June 1852, the day he organized a branch of the church there with the assistance of Elder Thomas Obray (who had arrived from England just after Snow’s departure).[1] Back in the Waldensian valleys again, Woodard commended John Daniel Malan for his able leadership of the church during the missionaries’ absence and recommenced preaching from home to home and baptizing new converts. He also encountered recalcitrance among the Mormon converts and therefore “pruned the vineyard, cutting off dead branches,” excommunicating the dissident or unfaithful members from the church.[2]

In late July 1852, Woodard made his first proselytizing foray into Catholic territory, spending three weeks in Turin preaching and passing out literature. Woodard’s expansion of the Mormon mission to proselytize was technically inconsistent with the spirit of the Statuto (promulgated by King Carlo Alberto), which provided that the Catholic Church was the only religion of the state and that other existing cults would be tolerated. Nevertheless, Woodard was following in the footsteps of Waldensians and other Protestants who had already established churches and newspapers and were proselytizing in the capital.

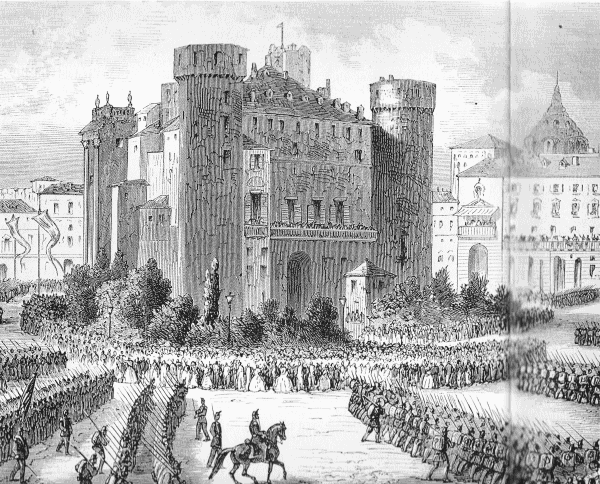

The king reviewing the army and national guard in Piazza Castello, Turin. Cosson-Smeeton, Il re passa in rivista l'esercito in Piazza Castello a Torino. Reprinted from Incisione (XIX secolo), Roma, Museo del Risorgimento, in Fraco Paloscia, ed., Il Piemonte dei grandi viaggiatori (Rome: Edizioni Abete, 1991), 12.

The king reviewing the army and national guard in Piazza Castello, Turin. Cosson-Smeeton, Il re passa in rivista l'esercito in Piazza Castello a Torino. Reprinted from Incisione (XIX secolo), Roma, Museo del Risorgimento, in Fraco Paloscia, ed., Il Piemonte dei grandi viaggiatori (Rome: Edizioni Abete, 1991), 12.

The Protestants were emboldened during the early 1850s when King Victor Emanuel II (Carlo Alberto’s successor) and his government ministers embarked on an aggressive campaign to secularize state affairs by effectively curtailing the Catholic Church’s temporal power. The focus of this campaign was the promulgation of the so-called Siccardi Laws that proposed severe limitations on church tribunals, the abolition of penalties for nonobservance of religious holidays, and the requirement that religious organizations obtain permission to acquire property or to accept donated property. In particular, the minister’s efforts to limit the Catholic Church tribunals strictly to internal church affairs and doctrinal matters, while making all citizens—including the clergy—subject to state courts in criminal and civil cases, set off a strong reaction from the Catholic hierarchy and newspapers. After these laws passed in the spring of 1850, supporters constructed—financed by grassroots collection of money—an obelisk monument with the inscription La legge è uguale per tutti (The law is equal for everyone), which still stands in Turin’s Piazza Savoia. But in 1852 the minister of justice, Carlo Boncompagni, proposed a new law to permit civil marriages in certain circumstances, which again aroused a “wave of recriminations” from Catholic and conservative quarters in Turin.[3]

When Protestants began worshipping outside the Waldensian valleys and publishing newspapers to advocate their positions, they were not prosecuted unless they fit within a formula which had been articulated by prime minister Camillo Cavour, who stated that “the King’s government cannot tolerate proselytism or public acts in locations where they could produce public tumult and disorder,” but no coercive measures were normally taken unless the activity threatened to create civil strife.[4] Some Catholics protested against this policy and occasionally the government relented and prosecuted Protestants or expelled foreign missionaries. In fact, Waldensian Pastor Amedeo Bert was prosecuted (and acquitted) in Turin for publishing an article which was alleged to have “excited contempt for the religion of the state” during the same period that Mormon missionaries arrived in the city to commence missionary activities.[5]

Woodard, accompanied by François Combe (who was a Waldensian convert from the valleys), printed public announcements and placed them in cafes and along the streets of the city. These flyers stated that they were “authorized to give all necessary information” concerning their church and that they would be present “every day from 7 to 9 in the evening, in via della Chiesa, n. 9 bis, left staircase, at the end of the courtyard, first floor” to explain to the public “information concerning their doctrines and emigration program which they have established to the United States.”[6] It is unclear whether the missionaries had copies of the newly published Il Libro di Mormon, but they did distribute copies of their first Italian language tract, Restaurazione dell’antico Evangelio.[7]

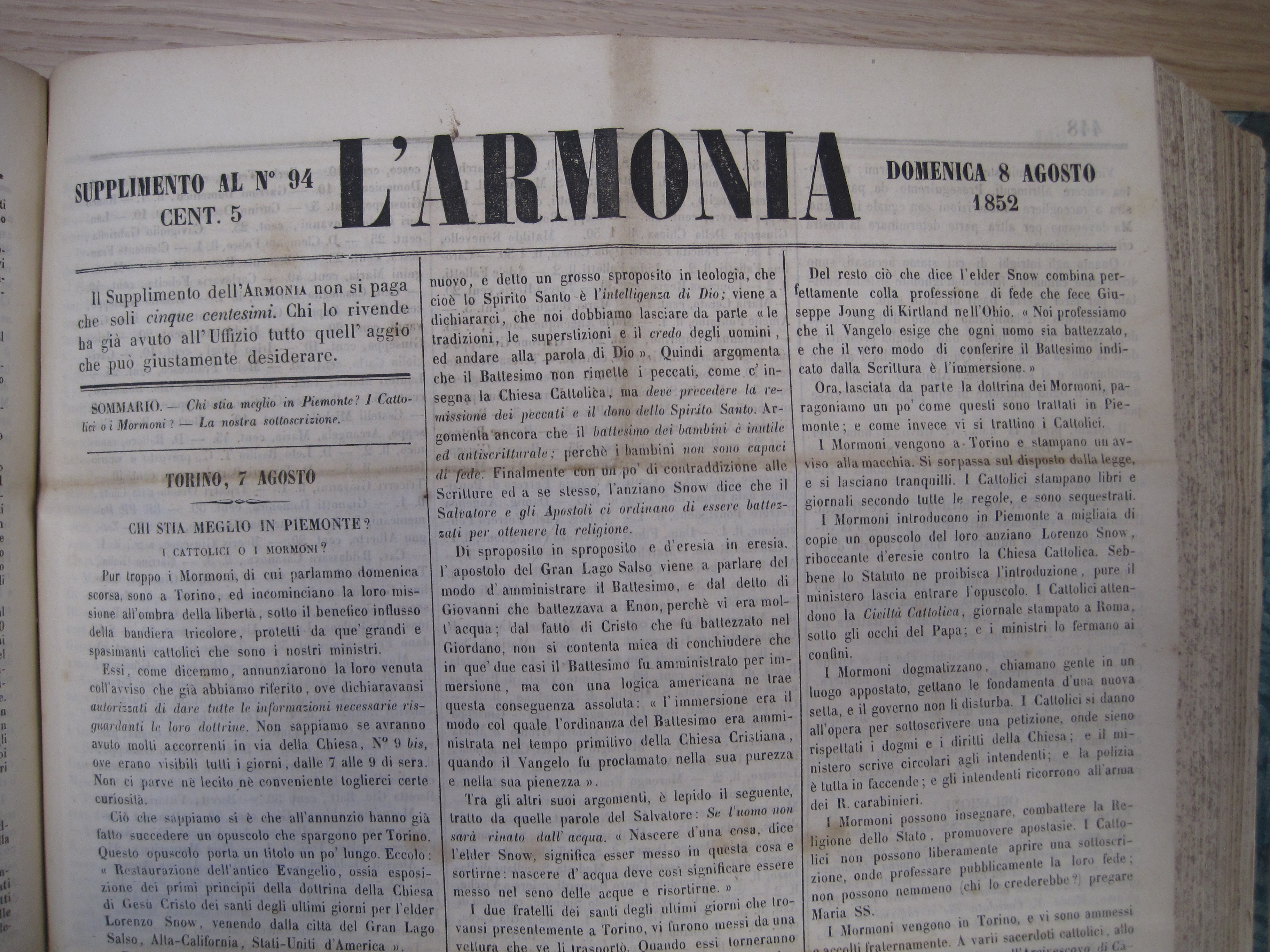

The same Catholic newspaper that was offended by Waldensian Pastor Amedeo Bert’s article complained about the presence of Mormon missionaries in the capital city of the Kingdom of Sardinia. On 1 August L’Armonia, one of many secular and sectarian newspapers founded in Turin in 1848 after King Carlo Alberto’s constitution was granted, published a supplement with a startling headline for its lead story: “Mormons in Turin.” The article discussed, for the first time in an Italian newspaper, the history and contents of the Book of Mormon and some points of church history and doctrine. It also employed a tactic common in nineteenth-century religious propaganda, maligning Joseph Smith by labeling him a new Muhammad.[8] The article argued that both Mormons and Waldensians were conducting missionary work and publishing religious pamphlets, contrary to the law of the Kingdom of Sardinia, and that the government was ignoring this while at the same time waging a “war” against the Catholic Church. Specifically, it accused the minister of justice, Carlo Boncompagni, of promoting a new marriage law that made it attractive for the Mormons to come to Italy: “For what reason did the Mormons come to Turin? They got word of the Boncompagni law . . . and since it does not prohibit plurality of wives, they believed that our Minister of Justice was a good Mormon. They saw that the wind among us was favorable for their doctrine, that we would embrace their brethren with open arms, so they sent two of them.”[9]

One week later, the headline of the lead article in L’Armonia asked, “Who is better off in Turin? The Catholics or the Mormons?” The newspaper complained that “unfortunately the Mormons, about whom we wrote last Sunday, are in Turin beginning their mission in the shadow of liberty, under the beneficial influence of the three-colored flag, protected by those great and liberty-obsessed Catholics who are our state ministers.” The article discussed Snow’s Restaurazione dell’antico Evangelio and warned readers to not be surprised if the missionaries began publishing a newspaper in Turin, or even building a temple, because the government ministers would allow such activities due to their “so-called love of liberty.” It then complained of what it characterized as the government’s persecution of the Catholic Church while the Mormon missionaries were being allowed to conduct their activities without fear of legal action:

The Mormons introduce in Piedmont thousands of copies of a pamphlet by their elder Lorenzo Snow, full of heresies against the Catholic Church. Although the Statuto prohibits the introduction of such materials, the ministry still lets the pamphlet enter. The Catholics wait for La Civiltà Cattolica, a newspaper printed in Rome under the eyes of the Pope, and the ministers stop it at the borders. . . . Mormons can teach, combat the religion of state, promote apostacies. The Catholics cannot . . . freely profess their faith in public; they cannot even (who would have believed it?) pray to the Virgin Mary. The Mormons come to Turin and are accepted in a brotherly way. [But] various Catholic priests, including the Archbishop of Turin and the Archbishop of Cagliari, are denied the right of return to their headquarters, to their homeland. The Mormons are in Piedmont, and no one insults them. The Catholic priests are derided in print, insulted, and persecuted on the public streets. . . . Thus one lives in Piedmont! Thus a liberal ministry treats the Catholic religion that, according to the first article of the Statuto, is the only religion of the state.[10]

During the same week that L’Armonia began targeting Mormon missionaries in Turin, another Catholic newspaper published in the same city warned its readers in another front-page article that “sects in Piedmont are doubling their forces and are hustling into Turin’s markets to make converts. Today they are spreading their calling cards in the workshops to invite the Torinese to gather in a home where two emissaries from the Society of the United States of America known as the Latter Day Saints will be present.” It then observed, “Who knows what this new brand of saints will teach? But it is certain that they will not teach either the doctrine of the Catholic Church or obedience to the Pope.”[11]

The Catholic newspaper L'Armonia. Courtesy of Archives of the Risorgimento Museum, Turin.

The Catholic newspaper L'Armonia. Courtesy of Archives of the Risorgimento Museum, Turin.

A second article in the same issue explained in more detail about this new threat and, like L’Armonia, revealed the contents of the missionaries’ handbills. “Look at those who have a chair in Piedmont,” the paper observed, “look at those who are privileged from the beginning. They print without identifying the printer, they claim they are authorized. They are perfectly in accord with the government; they state the place, the number, and the floor where they live.” It concluded that the Mormons were apparently acting with the government’s permission and that “in our time the same can be said in Piedmont, it is better to be an emigrant than a Piemontese; it is better being a heretic than a Catholic, because the former are blessed while the latter are persecuted.”[12]

Despite the polemics evident in L’Armonia and La Campana, perhaps the most scathing article published about Mormonism during this period appeared in La Civiltà Cattolica. The Jesuit publication, created to offer a Catholic alternative to the Risorgimento, bristled that Mormons were present in Piedmont under the guise of religious liberty. The article noted that Luigi Taparelli (one of the newspaper’s cofounders) had observed in 1841 that Mormonism’s founder, Joseph Smith, had surrounded himself with 2,000 armed proselytes on the banks of the Mississippi and that a decade later the church had proclaimed its independence from the United States. The article also complained that Lorenzo Snow had published La Voix de Joseph, that it considered to be anti-Catholic propaganda, and noted that the pamphlet was circulating in the public square because of the government’s backward interpretation of the Statuto (constitution).[13]

These articles demonstrate that Snow’s pamphlets and the presence of Mormon missionaries in Turin struck some Catholics’s religious sensibilities very deeply. But this polemic concerning the Mormons really reflected the deepening conflict between the Kingdom of Sardinia and Catholics who were already sparring about the Waldensians building a temple, holding services, and publishing in Torino. In fact, contrary to these publications’ assertions, the Sardinian government not ignoring the Mormon missionaries in Turin and occasionally harassed them about their missionary activities. Woodard wrote, “I have been twice summoned before the magistrates for having given religious instructions to persons in my own room. As I knew they could not attack me for any infringement of their laws against public meetings, I have continued to sell and circulate our works up to the present moment.” Nevertheless, he recognized that the police could employ different tactics: “As the police have refused to legalize my passport, it will be necessary for me to obtain a signature on the French frontier, which is only a few miles from the brethren here; but to be compelled to change residence in that manner, is one of the many vexations to which we are subjected in those countries where freedom is yet only a name.”[14]

Woodard later described the specific charge levied against him as “giving theological instructions without first being designated as an ‘Ecclesiastic’ upon the face of his passport.” After being compelled to leave Piedmont, he found some consolation in the fact that the French border was close enough for the church members in the Waldensian valleys to cross over and dine with him, then return to their homes by evening. Optimistic that “a simple change in the cabinet at Turin may allow my return,” he was also looking to other cities in Italy further south which, he was certain, “are fast ripening for the Gospel.”[15]

In November 1852, the Millennial Star noted that Woodard decided to visit his family and church headquarters in England during his forced exile, and during that time he made arrangements for a new missionary, Elder Thomas Margetts, to serve with him in Italy. In early January 1853, Woodard and Margetts met in Switzerland and made an arduous night crossing of the Alps during which they were “drawn on sledges [sleighs] through the snows” of the mountain passes.[16] One of their first acts after arriving in Torre Pellice was to ascend Mount Brigham to the Rock of Prophecy and hold a meeting to pray, prophesy, and make plans. In contemplating the many “provinces, principalities, [and] kingdoms” within the mission boundaries that were “yet unvisited by the messengers of truth,” Woodard and Margetts sensed the enormity of their task and lamented the lack of missionaries to carry it out. “The harvest is great, but the labourers are few.”

The missionaries decided to maximize their coverage by splitting up and working individually. Margetts worked primarily in Angrogna valley until the latter part of January, spending ten to twelve hours each day studying Italian. When he began to have health problems, he consulted with Woodard, and it was decided that Margetts would go to Genoa on the Ligurian coast: “Genoa being a seaport, we thought we should have more liberty for telling the people our message, and also that it would be more conducive to my health.”[17]

Woodard accompanied the inexperienced Margetts to Genoa, where for a month they sought a means of opening missionary work. But, finding that “with all their talk of liberty, there was no liberty for us, and that we could do nothing there unless we could do it privately,” Woodard returned to the valleys, while Margetts remained for about three more months discussing Mormonism with individuals in private settings. Although “a spirit of inquiry” was manifest on the part of many people, he managed to win only one convert, a nineteen-year-old man named Giovanni Baptista Paganinni, who was baptized and confirmed by Margetts on 29 March 1853.[18] In contemplating why many other persons who had been keenly interested in his message inexplicably began to avoid him and why the Catholic priests began to recognize and talk about him in the streets, Margetts concluded that it must have something to do with “the annual time of confession” in progress at the time in Genoa. Upon inquiring with acquaintances,

They told me that they firmly believed it to be their duty to confess all they heard from any one opposed to their religion, or contrary to the Catholic church. “Then,” said I, “you have confessed all that I have said to you about my religion.” “Certainly,” they replied, “we have told all to the priests, because we have been taught that we shall suffer if we do not tell all, and the priests have warned us against you, and we now believe you to be an impostor, and from this time you will be closely watched.”

About this same time, Margetts’s health took a turn for the worse as he began suffering “from a pain in the head, which had produced a degree of nervous debility” and difficulty in walking. He left Genoa for Turin in early May, discouraged by the combination of unfavorable laws, opposition from Catholic priests, and his illness that was made worse by lack of money, which forced him to live several weeks on one meal a day and rendered him “very weak and low in body.” On his arrival in Turin, he found that he was “well known,” presumably because messages had been sent from Genoa informing the authorities of his preaching activities. He remained only a few days before returning to the Waldensian valleys, where he found the comfort and care he needed. Because of his debilitating illness, Margetts was released from his mission by Woodard and departed for England on 8 June, with “mingled feelings” because he was unable to convert more Italians, “their day appearing to be in the future, and not now.”[19]

While Margetts was in Genoa, another missionary, Elder George D. Keaton, arrived from England to assist Woodard in moving the missionary campaign forward.[20] Keaton wrote from the province of Pinerolo in June to report that he had been appointed to work in the Waldensian mountains and valleys and had been distributing tracts, preaching, and bearing testimony. He was “generally well received,” many had “listened attentively” to his message, and he had baptized eight persons with many more investigating the work. Keaton had been “greatly blessed” in his study of French, and in accordance with Woodard’s predictions during a blessing on Mount Brigham: “My tongue has been loosened, and I have been enabled to dispense the words of life freely.” His reports to mission headquarters reflect the pattern seen before of preaching in private homes to congregations of relatives and neighbors, some of whom were eager listeners because of their dissatisfaction with their religion.[21] Woodard, meanwhile, was working for the first time in a nearby valley where, he reported, “the work has commenced in a place where we have hitherto had no footing, but where we have been mocked and derided every time we passed.”[22]

By the summer of 1853, Woodard had organized a total of three branches of the church: Angrogna, San Bartolomeo (Prarostino), and San Germano.[23] But even with the consolidation of the church, the fierce opposition did not abate, and Woodard describes ruffians throwing stones, issuing threats, and sabotaging meetings—a situation that became commonplace for the missionaries and converts in the valleys:

Our enemies in that neighborhood have been numerous and vigilant, embracing all classes, from the magistrate to the match-seller. To hinder our meetings, they have stopped up footpaths which have been frequented from time immemorial, but, finding this unsuccessful, they formed a “Holy Alliance” to attack me as I came out of a meeting. I had just bidden adieu to the brethren, who all retired to their homes, except the family in whose house I had preached, when from the threshold where I stood musing, I perceived a band of men approaching. I immediately guessed their intention, but before I could enter the garden several large stones struck right and left, yet without touching me. As the night was rather dark, I glided away under the vine trellis, one of the stones rattling through the foliage just over my bare head. . . . Then, striking their cudgels to the tune of the Devil’s concert, they retired, swearing they would yet have vengeance upon such a disorderly character as myself.[24]

In addition to religious and social persecution directed at the fledgling Latter-day Saint community, a severe agricultural crisis from 1853 to 1854 throughout Piedmont worsened conditions in the already fragile Waldensian economy, creating even greater distress for the valleys’ inhabitants. Woodard reported searching for “almost half a day in the vineyard of a brother, but could not find grapes enough to make our Sacramental wine. He has now sold all he possessed, to prepare for Zion, but I need not say how immensely the value of his property was diminished, while others of the brethren, who were dependent upon daily labour, no longer find employ where the crop fails on all sides.”[25]

By this time, church leaders and members were already well along in their plans to emigrate to Zion. In January 1854, according to previous instruction given by Lorenzo Snow, Woodard left Italy and returned home to England. Several weeks later, in February, he and his family accompanied the first group of Italian and Swiss emigrants when they left Liverpool for the Atlantic crossing. With Woodard’s departure, Italy ceased to be a separate and independent mission of the church and was combined with the Swiss Mission, becoming a conference of the Swiss and Italian Mission presided over by Stenhouse in Geneva.[26] During the next two years, two more groups of Mormon converts would depart from the valleys, which depleted the mission of most of its charter members.

Following Woodard’s departure, Keaton was the only full-time missionary in Italy. “The work of God is moving steadily onward, in the midst of opposition and persecution,” Keaton reported. “The cloven foot manifests itself in various ways. Ignorant persecuting rowdies often hold themselves in readiness, and watch for an opportunity to carry into effect their diabolical purposes. . . . In some places, we are obliged to watch for our opportunities to get about among the Saints and the people, for fear of the mob.” One day two ruffians stoned a passerby, thinking him a Mormon missionary. Receiving a severe blow, the victim ran after and accosted his attackers who, upon realizing he was not a Mormon, begged the man’s pardon. He replied, “They had no right to throw stones at ‘Mormons,’ or anyone else. They were summoned before the magistrates and punished. Since this occurrence, I have not seen anything of the persecutors in that direction.” Keaton said:

“I have preached in the parlours of the rich, in the humble cottages of the peasants, in school-rooms, and in stables among the cattle, where the people assemble in the evenings for the sake of the warmth. I have slept in the chambers of the rich, as well as in the hovels of the poor, and sometimes my entertainers have been so poor that they have not been able to provide me with a bed, in consequence of which I have been conducted into barns, to take my repose on hay and straw, where I have often been awakened by the cold night winds as they have swept over my face, but I have felt thankful that I had a cover over my head. During the severe weather this winter, I have often been obliged to sleep in stables among the cattle, as it has been too cold to sleep in barns.”[27]

Although the influence of the Waldensian pastors was a powerful deterrent to conversion, they were not always successful—despite strenuous efforts—in dissuading their parishioners from leaving their native faith to embrace Mormonism. For Keaton and the other missionaries, it was a source of gratification to see that some converts were unwilling to be swayed from their decision to embrace a new faith. Keaton tells of attending the annual Waldensian celebration of “The Glorious Return” of 1689 and the vows of loyalty that are renewed at that time. “The rev. gentleman who addressed the vast assembly, knowing that many in their valleys had been baptised into the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, and fearing that others would do likewise, seized the opportunity to exhort their hearers not to change their religion, but cleave to that faith which their forefathers had sworn to maintain. Many of the people will not believe anything that is not believed in by their religious leaders, but still there are those who are determined to use their own judgment in relation to religion as well as other matters.”[28]

In one parish the minister made the rounds of the church members’ homes “and reproved them for having received another baptism; but in vain did he exhort them to abandon the Saints, and cleave to the Protestant Church.” Keaton also noted that sometimes the preaching of the clergy only aided the cause of the missionaries. The pastor in one village “has been lecturing against the Saints, by which means he has stirred up many people to seek after the truth, who have come to us inquiring into our doctrine. In spite of all opposition, the Church which has been planted in Italy, remains as firm as the foundation of these Alpine mountains.”[29]

In March 1854, Stenhouse began to reorganize the missionary effort in Italy: “In consideration, therefore, of the many difficulties and much suffering attending the open circulation of our publications in Italy, I have been led to change tactics, and have sent two young Geneva Elders to Turin and Nice, to labour at their occupations, and to seek out opportunities of distributing the printed word, and of doing as much more as circumstances and the Spirit of the Lord may direct. For the present we see no other means of ‘scattering the seeds of righteousness’—it is dangerous to do ‘big business.’”[30]

In June, Keaton was transferred to Switzerland, where he spent the last year of his mission. Before his change of assignment, Keaton reported that he had been trying to open new areas to missionary work, traveling “in different parishes where the Gospel is yet unknown; and in some places a spirit of inquiry, quite encouraging, has been manifested.” He had “sown much seed” along the way, which he hoped in due time to reap.[31] Despite these warnings, Keaton optimistically reported in June: “The hireling clergy are not backward in opposing us, but the cannot put down ‘Mormonism,’ neither can they stop its progress.”[32]

The October 1854 General Council in Geneva

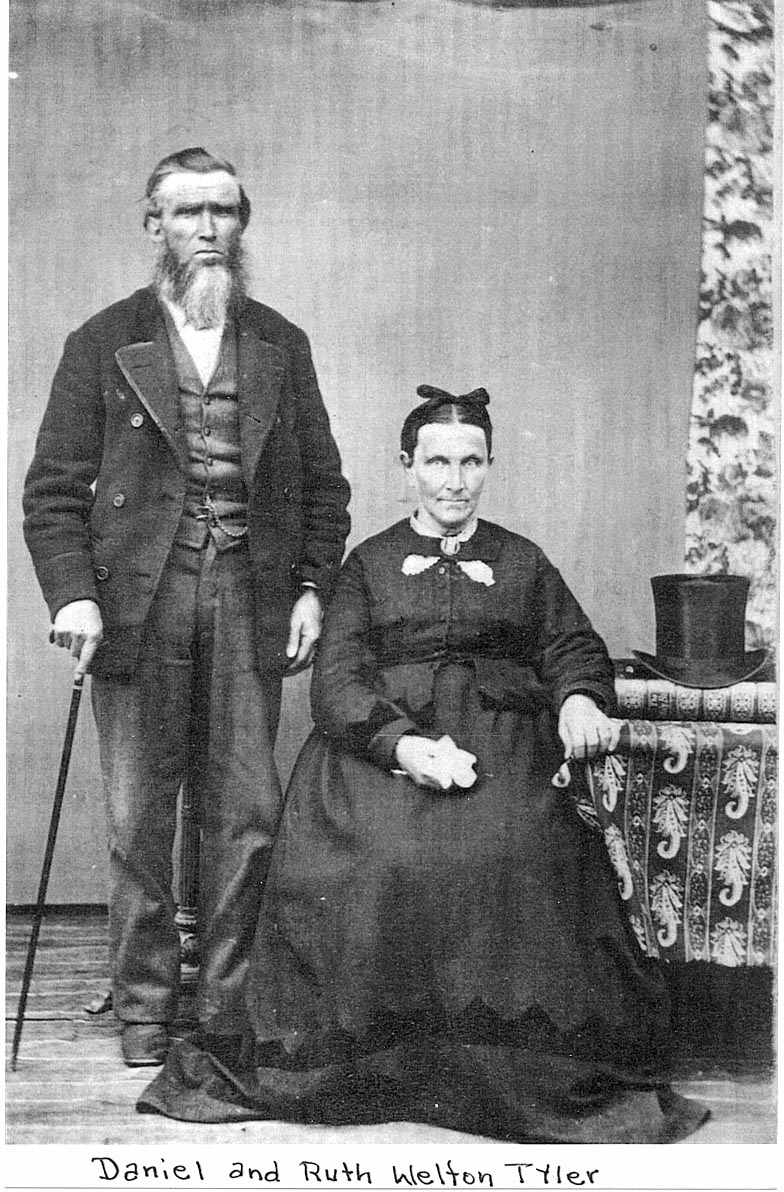

In October 1854, nine missionaries met at the headquarters of the Swiss and Italian Mission in Geneva to assess their efforts, reorganize the leadership, and plan for the future.[33] Elder Stenhouse, the mission president, presided over the council, while Charles Savage acted as clerk and Samuel Francis, newly arrived from England, acted as reporter. Stenhouse opened the proceedings by reflecting on his experiences of the past four years and dwelling on the progress that had been made despite many obstacles: “When I look back upon the circumstances attending the introduction of the principles of salvation in these nations, and consider our own weakness, and now look upon the work which has been accomplished, I feel profoundly grateful to the Lord for His goodness. . . . Brethren, do not be discouraged by difficulties. Let not doubts and fears weigh upon your minds. In spite of every opposition, the work of the Lord will be accomplished.” During the meeting, Stenhouse’s replacement, Daniel Tyler, was presented as the new president of the Swiss and Italian Mission.[34]

In subsequent sessions of the council, the missionaries reported on the status of the church in various areas of the mission. The number of church members in the mission was reported as “2 High Priests, 2 Seventies, 12 Elders, 9 Priests, 8 Teachers, 1 Deacon, 258 Members, total 292.” Keaton gave a positive appraisal of the prospects for growth in Italy: “There are three Branches in Italy. In the valleys where the Saints are, prospects are good. The Saints are good and faithful—the most obedient I have ever seen. They are very poor. We have been unsuccessful in endeavoring to introduce the Gospel into the towns on the plains.”[35]

During the course of the conference, Tyler reorganized the mission leadership, and a new missionary, Samuel Francis, was assigned as president of the Italian Conference.[36] Francis left Geneva on 6 October, traveling by coach, foot, and train, and reached Turin the next day, where he found Jean Jacques Ruban, a traveling elder from Geneva, waiting for him. “I felt glad to find a Bro[ther] so far from home, one whose spirit united with my own, and although we could not speak a word to each other, we felt we were one, and thus rejoiced my heart.” He traveled the final leg of his journey to Torre Pellice, where he was met by David Roman, one of the local church leaders. Troubled by his lack of linguistic skill, Francis was cheered when it became apparent that a few of the members spoke some English and that he could communicate a little with other people by using his dictionary, a phrase book, and hand gestures.

The members of the Italian conference were anxious to meet their new president, and Francis embarked on a series of get-acquainted visits that quickly familiarized him with the rugged terrain, stark lifestyle, and religious dynamics of the surrounding mountain culture. He met at the Malan home in Angrogna with local church leaders: Ruban, David Roman, Jean Bertoch (the branch president from San Germano), and Jean Malan (the branch president in Angrogna). Though unable to communicate well and fearful of becoming lost in the deep woods, Francis plunged into the daily, unpredictable demands of supervising missionary and church matters. He spent most of his time during the following weeks studying French and walking the rough mountain pathways to visit the people in their homes and to attend religious services in the area’s branches.

Francis was usually accompanied in his peregrinations by one of the church members or one of the two traveling elders, Ruban and Malan. Sleeping arrangements were an ongoing source of anxiety for the young itinerant preacher, who, accustomed to the norms of British propriety and the need for privacy, found some aspects of Waldensian hospitality difficult to accept: “In connection with Elder Bertoch, I visited Bro. Michel Roshan at Vivian. I was accommodated with a place to sleep with Elder Bertoch in the family bed. We were seven in number consisting of Bro. Roshan and wife, two daughters and son and Elder Bertoch and myself. I did not like my lodgings very well, and did not want them to invite me to pass the next night there.”[37]

Despite some strain in adjusting to a new language and culture, Francis’s writings reflect a growing sense of confidence and satisfaction. He reported in December that more than a hundred converts had been baptized in Italy since the beginning of the mission in 1850, but that at present there were only about seventy members left due to emigration and excommunication.[38] Nevertheless, he had opened some new areas to preaching and, despite the necessity of cutting off some individuals for neglect of duty, the members were thriving spiritually: “My little flock, and I assure you, I feel myself honoured to be their shepherd, are as happy and faithful as any who have presumed to tread the narrow way. You might see them, though they have two or three miles to go over rugged mountains, waiting more than an hour before the meeting time, for the arrival of the brethren. . . . We meet in peace in our stables, kitchens, and woodhouses, and enjoy ourselves much with the truth.” Francis described himself as “full of faith for Italy” and hoped to extend the work into the plains.[39]

Samuel Fracis, ca. 1890. C. R. Savage Collection, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT.

Samuel Fracis, ca. 1890. C. R. Savage Collection, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT.

Francis’s journal provides interesting insights into the early operation of the church. Although there were three organized branches—Angrogna, Prarostino/

In addition, the unity of the members was sometimes disrupted by the daily reality of conflicting egos and interests. Francis was on occasion constrained to arbitrate disputes between the members, even though frustrated by his inability to understand fully the issues involved. In Angrogna, for example, following heated contention between Elders Ruban, Malan, and Roman that lasted several days, a resolution was reached by the members themselves after Francis tried to intervene. The severity and trauma of the dispute made Malan’s wife, Pauline, physically ill, and required that Francis “administer the ordinance”—i.e., give her a blessing—to help her recover. The conflict lingered on for several more months and eventually necessitated the convening of a special church council. A few months later, both Malan and Roman were rebaptized as a sign of their repentance and reconciliation in this infelicitous affair.[41]

A War of Bread and Cheese and a Spirit of Emigration

In June 1855, Francis wrote a long report to mission headquarters in which he analyzed why the bright prospects for growth outlined in his previous missives had not materialized to the degree expected. The tone of the letter is reflective and somewhat apologetic: the Italian conference had seen only six baptisms so far, “rather a small figure . . . for six months.” The slow growth, in his opinion, could be attributed to economic conditions among the Waldensians that have “not been so bad as at present for many years.” His explanation of the crisis points to changes in traditional markets and the impact of plant infestations as the underlying causes. According to what he had learned, the coming of the railroad and shipment of local wheat to foreign markets raised prices sharply. “This, with the destruction of the vines, the potato disease, and a falling off of labour, accounts for the state of the inhabitants at present.”[42] Scholars have argued that this economic crisis also involved the simultaneous occurrence of a cholera epidemic, crop failure, and famine that caused widespread deprivation in Piedmont throughout the 1850s.[43]

The combined effect of all these factors was catastrophic for the vast majority of the inhabitants of the Waldensian valleys, who, even in the best of times, struggled to maintain a reasonable standard of living. Francis noted how the crisis adversely affected most of the Mormon converts: “The whole of our Saints here at present, are of the poorer class, and depend mostly on others for labour, or . . . have a little piece of ground on the tops of the mountains, which no one cares to purchase. And this winter, they, with many of their fellow mortals, have been the sufferers of indescribable poverty. . . . Elder Rochan has not had any employ for the last three or four months, and nearly all the other Saints in the valleys have been in the same condition.”[44]

Widespread economic distress led to an intensification of sectarian rivalry as religious organizations competed with each other to alleviate the effects of unemployment, hunger, and disease among the local population. Francis reported that missionary prospects were greatly diminished “through the influence of the Protestant priest, exercised in the shape of presents of money, wheat, potatoes, and other things, which is the strongest influence they can use” among the poor people of the Waldensian valleys.[45] The church had no financial resources to help the members, and other government and humanitarian sources were not available to them. In effect then, the members were left alone to deal with their destitution, and this of course inhibited their participation in church activities and left them vulnerable to enticements to forsake their new religion for want of basic needs.

Francis also pointed out that there were no benevolent societies to help the poor in the valleys, and donations collected abroad by Protestant charitable organizations were given to the local Waldensian ministers:

The poor apply to the minister for assistance, and if he has any he will supply them, but I need not tell you that he will give nothing to the Saints, unless they renounce “Mormonism.” Thus, the poor Saints are deprived of all charity, and have no hope, but in God. This winter and spring have been a severe trial; the rough hardy faces, that came so joyfully to the meetings . . . have been obliged to rest at home from weakness, caused by want. . . . Amid these scenes of poverty, the ministers have visited many of the Saints and tempted them with various articles of food to leave the Church, and, in some instances, the soft, smooth voice of the minister’s wife has sought by these temptations to draw the Saints away.[46]

He added that the “oily words” of English ladies visiting the valleys have been heard: one young Latter-day Saint sister was promised that if she would leave the church, she would be taken to England to serve an old gentleman, “intimating that without doubt he would leave her his money. . . . But I am glad to say the sister refused all her flattering temptations. Some of the saints have fallen among these circumstances, and others have had a hard struggle. . . . The Protestants will keep families of Catholics, if they will change their religion; and Catholics . . . will keep families of Protestants, if they will turn Catholics.” The sectarian rivalry in the valleys was, as Francis characterized it, “a continual war, not of arguments, but of bread and cheese.”[47]

It is both fascinating and lamentable that questions about the cause of the economic crisis in the valleys became a source of interfaith recriminations and strife. Francis attributed the blight that ruined the vineyards and orchards to the wickedness of the people themselves, stating that “the judgments of God continue to manifest themselves among the vines and fruit trees.” Perhaps his strong words are understandable given the inflammatory comments of the “would-be wise” in the community that “none of these things transpired until the ‘Mormons’ arrived, and they firmly believe that we are the ‘Jonahs,’ and threaten us that if the plagues don’t stop soon, they will ‘throw us overboard’ for proof.”[48]

Inclement weather during the winter and spring of 1855 contributed to the acute economic hardships suffered by the Waldensian people and presented obstacles to church work. Francis describes how deep snows in May ruined the wheat crop and late frosts severely damaged the fruit and walnut trees from which the people made their oil. On top of all that, torrential rains washed away wheat fields and bridges. These severe weather conditions often prevented church leaders from visiting the homes of members to provide comfort and disrupted missionaries’ proselytizing efforts.[49] All of this, coupled with preparations for war against Russia and “signs of eternal revolutions . . . is enough to tax the wisdom of this nation, which is struggling hard for life and liberty.”[50]

Notes

[1] Millennial Star, 13 November 1852, 603.

[2] Millennial Star, 18 September 1852, 476.

[3] Paola Notario and Narciso Nada, “Il Piemonte sabaudo: dal periodo napoleonico al Risorgimento,” in Giuseppe Galasso, ed., Storia d’Italia, vol. 8 (Torino: Unione Tipografica-Editrice Torinese, 1993), 362–78.

[4] Camillo Cavour, quoted in Valdo Vinay, Storia dei Valdesi, 3 vols. (Torino: Claudiana, 1980), 3:65.

[5] See “An Account of the Trial of Signor Amedeo Bert, Vaudois Pastor of Turin,” The Catholic Layman [Dublin, Ireland] 1, no. 8 (August 1852).

[6] “I Mormoni a Torino,” L’Armonia, Supplemento al n. 91 (1 Agosto 1852), 451. We are indebted to Ms. Francesca Rocci, head researcher and archivist in the Museo Nazionale del Risorgimento, Turin, Italy, for making copies of these issues available. L’Armonia had published one previous article concerning Mormonism before the appearance of missionaries in the city. See “I Mormoni,” L’Armonia, 29 January 1852, 59. This article prompted the Waldensian newspaper in Turin to suggest what it perceived to be similarities between Mormonism and Catholicism. See “Mormoni,” La Buona Novella, 20 February 1852, 209.

[7] The Mormon missionaries’ flat was located on Via della Chiesa in Borgo Nuovo (outside the original city walls)that was located outside the city center near the Jewish synagogue and the Waldensian temple. Although the area had non-Catholic buildings it was not an Italian ghetto (similar to the one located in Venice and Rome) since there were also important Catholic structures in that neighborhood including San Massimo which was a major Catholic church. The street name was inaugurated in 1825, before the church of San Massimo was constructed in 1845, but in 1859 the street’s name was changed to its current Via San Massimo.

[8] See Arnold H. Green, “Mormonism and Islam: From Polemics to Mutual Respect,” BYU Studies 40, no. 4 (2001): 198–220; and “The Muhammad-Joseph Smith Comparison: Subjective Metaphor or a Sociology of Prophethood,” in Mormons and Muslims: Spiritual Foundations and Modern Manifestations, ed. Spencer J. Palmer (Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Press, 1983).

[9] “I Mormoni a Torino,” L’Armonia, Supplimento al n. 91 (1 Agosto 1852), 451. Concerning L’Armonia, see Antonio Socci, La Società dell’Allegria, il partito Piemontese contro la chiesa di Don Bosco (Milan: SugarCo, 1989), 84–87, and Lorella Naldini, “I Reati di Stampa a Torino tra il 1848 e l’unitá” (Tesi di Laurea, Universitá degli Studi di Torino, 1984–85), 223–47. The most important writer for the newspaper was a Catholic publicist named Giacomo Margotti (1823–87). See entry for Margotti in The Catholic Encyclopedia (New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1910). One Italian historian labeled L’Armonia as “fanatic” among Catholic newspapers and Margotti as a “firebrand” in denouncing the government’s opposition to the Catholic Church. See Notario and Nada, “Il Piemonte sabaudo,” 393.

[10] “Chi stia meglio in Piemonte? I Cattolici o I Mormoni?,” L’Armonia, Supplimento al n. 94 (8 Agosto 1852), 465. The articles that originally appeared in L’Armonia were republished in French in L’Écho du Mont-Blanc, 6 August 1852, VI, n. 635, 2 and L’Écho du Mont-Blanc, 13 August 1852, VI, n. 638, 2, in Annecy, Savoie.

[11]“Immoralità in Piemonte,” La Campana, Anno 3, Secolo 1, Num. 576, 31 July 1852, 2319.

[12]“Torinesi all’Erta!” La Campana, 31 July 1852, 2321. The articles that appeared in La Campana were noted in Courrier des Alpes, August 3, 1852, n. 167, 3, published in Chambery, Savoie. The paper even quoted the final paragraph from the second article that “it is better to be an emigrant than a Piemontese; it is better being a heretic than a Catholic, because the former are blessed while the latter are persecuted.”

[13] See “I Mormoniti ossia la Libertà Religiosa in Piemonte,” La Civiltà Cattolica, Anno Terzo, vol. 9 (1852), 593–602. The article cites Taparelli’s observation concerning Mormonism (that may be the first time Mormons were mentioned in print in Italy) as P. Luigi Taparelli [D’Azeglio], Saggio teoretico di dritto naturale appoggiato sul fatto, 5 vols. (Palermo: Stamperia d’Antonio Muratori, 1840–43). Luigi Taparelli was the brother of Massimo D’Azeglio who was King Victor Emmanuel’s prime minister when Mormon missionaries began passing out their cards in Turin and the articles in L’Armonia, La Campana, and La Civiltà Cattolica were published. During the same year La Civita-Catholica published correspondence that reported the claim that the government was permitting Mormons to proselytize in Turin. See, “Corrispondenza di Torino,” La Civilta-Catholica, Anno Terzo, vol. 9 (1832), 544–48.

[14] Millennial Star, 18 September 1852, 478–77.

[15] Millennial Star, 18 September 1852, 476–77; Richards, The Scriptural Allegory, 58–59. For further details, see also Jabez Woodard, “Diaries, 1852–57,” chapter 10, Church History Library.

[16] Richards, The Scriptural Allegory, 60–61; Millennial Star, 19 February 1853, 127.

[17] Millennial Star, 19 February 1853, 127, and 20 August 1853, 556.

[18] Richards, The Scriptural Allegory, 301; see also “Manuscript History of the Italian Mission (1850–54),” LR 4140 2, Church History Library.

[19] Millennial Star, 19 March 1853, 186; 30 April 1853, 282; 21 May 1853, 330; 2 July 1853, 426; and 20 August 1853, 556–57.

[20] George Dennis Keaton was a British convert who served in Italy (1852–54) and was later called as mission president in France (1855–58) before emigrating to Utah.

[21] Millennial Star, 16 July 1853, 461–62.

[22] Millennial Star, 3 September 1853, 585–86.

[23] “Manuscript History of the Italian Mission (1850–54).”

[24] Millennial Star, 8 October 1853, 670–71.

[25] Millennial Star, 8 October 1853, 670–71.

[26] Millennial Star, 28 January 1854, 61–62; Millennial Star, 11 March 1854, 155; Millennial Star, 25 March 1854, 191–92; and “Manuscript History of the Italian Mission (1850–54).”

[27] Millennial Star, 18 February 1854, 110–11, and 1 April 1854, 204–6.

[28] Millennial Star, 1 April 1854, 204–6.

[29] Millennial Star, 18 February 1854, 110–11.

[30] Millennial Star, 25 March 1854, 191–92.

[31] Millennial Star, 3 June 1854, 350–1, and 20 January 1855, 46.

[32] “Editorial,” Millennial Star, 22 July 1854, 457.

[33] For what follows, see Millennial Star, 9 September 1854, 572; 16 September 1854, 590; 11 November 1854, 705–9.

[34] Daniel Tyler, “Diaries 1853–1855,” MS 4846 1–2, Church History Library.

[35] Millennial Star, 11 November 1854, 705–9; see also Samuel Francis, journal, 1 October 1854, Church History Library.

[36] Francis had converted to the Church as a teenager in Trowbridge, England, after several years of spiritual searching. Beginning in 1850 he had served as a full-time local missionary, or “traveling elder,” preaching in public, baptizing numerous converts, encountering mobs who threw stones and rubbish at him, and presiding over branches in Sherborne, Cornwall, and Falmouth. Though only twenty-four and daunted by the task before him, Francis was a seasoned missionary who brought to the work in Italy significant leadership experience, skill as a preacher and proselytizer, and vibrant energy and faith to the Mormon cause. See Francis, journal. Unless otherwise noted, all information cited about Francis’ experiences is derived from his journal.

[37] Francis, journal, 24 October 1854.

[38] Millennial Star, 20 January 1855, 46. Because of inconsistency and discrepancies in the branch records, it is difficult to obtain a clear statistical portrait of Church members in this early period. However, we calculate that, over the life of the mission, there were 180 converts of whom 70 (39 percent) were excommunicated for a variety of reasons. Another 77 (43 percent) emigrated to Utah or other areas, and the remaining 18 percent either died, returned to the Waldensian church, or are unaccounted for in the records. See “Appendix to Italian Mission,” in Richards, The Scriptural Allegory, 297–312; see also “Manuscript History of the Italian Mission (1850–54).”

[39] Francis, journal, 12 November 1854; and Millennial Star, 20 January 1855, 46.

[40] Francis, journal, 22 October 1854; and Millennial Star, 20 January1855, 46.

[41] Francis, journal, 12–22 November and 14–19 December 1854, and 5–7 March 1855.

[42] Millennial Star, 21 July 1855, 454–55. See also Emilio Sereni, Storia del Paesaggio Agrario Italiano (Roma-Bari: Laterza, 1984), 260–61.

[43] See Shepard B. Clough, The Economic History of Modern Italy (New York: Columbia University Press, 1964), 32–33, 58–59; Notario and Nada, “Il Piemonte sabaudo,” 385–86; Gianni Toniolo, An Economic History of Liberal Italy, 1850–1918, trans. Maria Rees (London: Routledge, 1990), 40–41; and Denis Mack Smith, Modern Italy: A Political History (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1997), 37–45, who analyzes macroeconomic factors underlying the impoverished conditions of peasants, “the submerged nine-tenths of Italian society” (38).

[44] Millennial Star, 21 July 1855, 455, and August 1855, 538.

[45] Millennial Star, 21 July 1855, 454.

[46] Millennial Star, 21 July 1855, 455. Apparently, these efforts to lure the Saints away were to some degree successful. Francis later reported that “we have been under the necessity of cutting off seven, who in their poverty have been bought with bread and polent by the Protestant ministers.” Millennial Star, 25 August 1855, 538.

[47] Millennial Star, 21 July 1855, 455.

[48] Millennial Star, 2 August 1856, 491.

[49] Millennial Star, 21 July 1855, 455. See also Millennial Star, 4 April 1857, 219.

[50] Millennial Star, 21 July 1855, 456. In 1855, the prime minister of the Kingdom of Sardinia, Count Cavour, sent fifteen thousand Piedmontese troops to the Crimean War to fight against the Russians in order to curry political favor with Britain and France, an action that won the Sardinian government a seat at the Paris peace congress in 1856. See Smith, Modern Italy, 19.