Retreat or Return: Mormons and Italy, 1867-1945

James A. Toronto, Eric R Dursteler, and Michael W. Homer, "Retreat or Return: Mormons and Italy 1867-1945," in Mormons in the Piazza: History of the Latter-Day Saints in Italy, James A. Toronto, Eric R. Dursteler, and Michael W. Homer (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2017), 177-212.

Following the departure of the last missionary, the baptism of the last converts in 1867, and the emigration of all remaining active members, the Mormons ceased to have an official presence in Italy. Save for several brief forays of individual missionaries, the country was ignored for almost a century; for the church in Italy, these were one hundred years of solitude.[1] When examining this hundred-year interregnum, several questions loom large: First, why did the church leave Italy and not return for almost a century? Second, what led to the reversal of this hundred-year absence? This chapter and the next will argue that the reasons for both the Mormon absence and their return are situated as much in Salt Lake City as in Italy. They will also touch on the nature and extent of the very limited involvement of the church in Italy during this interregnum.

Religion and Religious Diversity in the Kingdom of Italy, 1861–1929

On the surface it is quite surprising that Mormonism disappeared from the Italian scene so quickly and completely. The Mormons were among the very first to send missionaries to proselytize in Italy following the establishment of the Statuto in 1848, which blunted the privileged position that Roman Catholicism enjoyed in Piedmont.[2] This significant event marked a first fragile step toward a more open and even tolerant religious atmosphere and a religious pluralism. It would seem that the Latter-day Saints would have been ideally situated to take advantage of this situation, and yet missionaries were withdrawn in 1867, “too early to reap any significant benefit” from the evolving religious atmosphere and the strongly anti-clerical political environment that characterized Italy from unification in 1861 until the Lateran Accords of 1929, when growth of non-Catholic sects stalled until after World War II. During this seventy-year period, numerous Protestant denominations established permanent missions in Italy and experienced significant growth but, in contrast to the Mormons, did not depart.[3]

On the opposite side of the equation, Mormon missionaries did not return to Italy until 1965, too late to benefit from the “conversion boom” that Italy experienced after World War II when many Italian immigrants who had converted to Protestant sects abroad began to return to their homeland. The Jehovah’s Witnesses, for example, were boosted by Italians who had emigrated to Belgium at the turn of the century to work in the mines.[4] The Mormons’ failure to maintain an active presence in and their belated return to Italy is crucial to explaining the church’s relative lack of success compared to other denominations in more recent decades.[5]

Traditionally, the explanations given for the Mormon departure and delayed return have centered primarily on the domestic situation in Italy from 1850 to 1950.[6] A combination of economic hardship, cultural disinclination, political opposition, and especially religious opposition from the Roman Catholic Church all conspired to prevent Mormon missionaries from finding much success initially and from returning subsequently. This explanation (which has become axiomatic) attributes the Mormon Church’s hundred-year absence to factors internal to Italy itself. The roots of this view were derived from the first missionaries to Italy, who explained, and perhaps attempted to justify, their relative lack of success by pointing to Italian cultural attitudes. As for the factors which permitted the Mormons to return, according to this interpretation, it was again internal Italian developments, particularly World War II and the great reforms associated with the Second Vatican Council in the early 1960s, which opened previously closed doors by loosening the grip of Catholicism over Italy. While these things certainly did influence Mormon policies vis-à-vis Italy, it seems clear that the primary reason that the LDS Church’s absence from 1867 to 1965 was due as much or more to internal issues in Utah than to the situation in Italy.[7]

Despite claims that Italy was effectively closed to non-Catholic efforts, there is ample evidence that had the Mormons wished to remain in or return to Italy, they would have been able to do so. The experience of the first Mormon missionaries to Italy clearly suggests this, as do the numerous other Protestant churches who actively proselytized among the Italian people in the period after the Mormons left. Indeed, except for the Waldensians, all the Protestant congregations present in Italy were established in the period after 1850.[8]

Just as the Mormons were encouraged by political developments in Italy, many Protestant leaders and influential figures in Great Britain and the United States followed the developments of the Risorgimento with “lively interest.”[9] In the years leading up to and following the 1861 unification, the Kingdom of Italy seemed to be, to many Protestant sects, “an open field, full of promise.” As one British Methodist official reported, Italy was “already moving toward a religious revitalization” that paralleled the political events of the Risorgimento.[10]

The relationship between church and state in Italy, the so-called Roman Question, would haunt the new nation throughout its formative years, and would only be resolved by Benito Mussolini in 1929 with the Lateran Accords.[11] For the almost seventy years before this, however, the conflict between the liberal governments of Italy and the papacy created an environment in which non-Catholic groups could evangelize openly. When Italy was unified in 1861 it became a veritable battleground as competing Protestant sects vied for the people’s souls. The first to arrive were the Wesleyans in 1861, and they were followed over the next decade by the English Baptists, the Adventists, the American Baptists, and the Methodists.[12] The end of the papal temporal powers in 1870 had a catalytic effect which led many Protestants to believe that the papacy’s “spiritual domain” would soon also collapse. Indeed, within several weeks the United States’ Methodist Episcopal Church sent missionaries to Italy “to contribute to the spiritual transformation of the country,” and they were soon followed by the Jehovah’s Witnesses and the Salvation Army.[13] Even the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints became involved in 1873 when John Avondet spent almost two years among the Waldensians.[14] Foreign Protestants were joined by the native Waldensians, who began to evangelize actively throughout the kingdom in the same decades in which the Mormons were retreating.[15]

While the hoped for religious reform never materialized, these evangelizing efforts produced significant fruits, at least in comparison to Mormon results. By 1883 the Wesleyans counted 1,451 members. In 1881, after only eight years of work, the Methodists numbered over 1,400 members, and by 1906 there were 2,689 adult members and an established ecclesiastical structure, including pastors and schools throughout Italy. New groups appeared in this era: Pentecostalism was introduced by returning Italian immigrants who had converted in the Americas, and by 1929, there were congregations in 149 localities throughout Italy.[16]

Census figures indicate a significant growth of Italians describing themselves as Protestants: they numbered 32,684 in 1861, 58,651 in 1871, and 123,253 by 1911. Of course these numbers were minuscule within the broader demographic context: in 1871 Italy’s population numbered 26.8 million, and by 1901 it had risen to 32.5 million, despite massive emigration.[17] Thus, though Protestant numbers quadrupled between 1861 and 1911, they represented under a quarter of 1 percent of the total population, which remained predominantly and persistently Catholic.

As this overview suggests, the period following the unification was a dynamic time in the religious history of Italy. A number of new sects without historical roots in Italy were able to make modest inroads into the peninsula after 1861, which suggests a need to reconsider the traditional Mormon explanation for the closing of the mission in Italy. If laws did not prevent their return, however, Mormon missionaries encountered strong cultural and social barriers that made missionary work in Italy extremely difficult, and these certainly influenced their hesitation to return.

In addition, the Mormons were specifically targeted for discriminatory treatment by the United States government during the same period. In 1879, President Rutherford B. Hayes and his secretary of state, William M. Evarts, became convinced that Mormon immigrants represented “potential violators” of anti-polygamy laws and thus ordered American ambassadors in Europe to seek the aid of local officials “in stopping any further Mormon departures to the United States.”[18] In the same year, the American chargé d’affaires in Rome, George W. Wurts, met with the Italian prime minister, Benedetto Cairoli, to discuss the “Mormon problem.” He noted (apparently unaware of the short-lived first Italian mission two decades earlier) that there was no need to fear a “Mormon crusade in Italy where as yet Mormonism is unknown.” Cairoli responded that although Mormonism was not present in his country, “all civilized Christian powers should cooperate to terminate the existence of a sect whose tenets are contrary to the recognized laws of morality and decency.”[19] More traditional mainline Protestant sects, in contrast, enjoyed the strong support and protection of their governments, which certainly contributed to their evangelical success.

In the end, however, it is clear that Italy from unification until the fascist era, was a religious open ground, worked with success by numerous religious groups both native and imported. There was no insurmountable legal or cultural impediment to the Mormons’ remaining or returning to work in Italy. While factors related to Italy certainly played an important role in the tardy return to Italy, to fully understand this decision it is necessary to look to developments in Utah, rather than Italy.

Americans and Italians, Mormons and Catholics

Despite the serious financial and political problems the LDS Church faced from 1858 to 1900 with the Utah War[20] and government sanctions against polygamy, and despite broader national and international circumstances,[21] its leaders remained committed to expanding missionary work. In 1860, for example, three Apostles were called to preside over the European mission, initiating a new wave of conversion and immigration.[22] A decade later, Brigham Young instructed Lorenzo Snow, who was traveling through Europe and the Mediterranean (including Italy), to “observe closely what openings now exist, or where they may be effected, for the introduction of the Gospel.”[23] Around 1900, Mormon leaders proposed “opening new missions in those areas where the gospel was not being preached,” and a year later Brigham Young Jr. declared that “the eyes of the Twelve have been roaming over the habitable globe, and they have looked upon Turkey, Austria, Russia, and especially South America.”[24] Parallel to these efforts, the number of missionaries experienced a consistent upward trajectory: more than 2,300 served in the turbulent 1880s, and in the following decade, despite the near bankruptcy of the church, more than six thousand missionaries were called to labor.[25]

The hierarchy’s interest is also evident in the geography of Mormon missionary work. In the first heady years of the church’s international missionary effort, missionaries served throughout Europe, in the Sandwich Islands (Hawaii), “Australia, Chile, India, Burma, Malta, Germany, Gibraltar, Hong Kong, New Zealand, South Africa, [and] Siam (Thailand).” This pace slowed somewhat in the last decades of the nineteenth century, but ambitious attempts were made to proselytize in Turkey, Palestine, Austria-Hungary, Mexico, Russia, Samoa, and Tonga, and a number of missions were also opened in North America. Between 1888 and 1900, eleven new missions were opened.[26] As part of now-President Lorenzo Snow’s renewed stress on the worldwide mission of the church, Heber J. Grant opened the twentieth foreign mission, Japan, in 1901.[27]

The growth in numbers of missionaries and missions as well as the commitment to opening new areas suggests that in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries the LDS Church was not in a retrenchment mode. On the contrary, the dedication to missionary work seems to have been consistent, despite numerous political and economic troubles which plagued the church. The decision not to return to Italy then was not a product of insufficient missionary commitment or investment. It would seem that in part, at least, the decision not to return to Italy was a product of the meager success of the first mission combined with cultural attitudes towards Italy, Italians, and Roman Catholicism that were common among Mormons in the nineteenth and first half of the twentieth centuries.

Αlthough a number of influential people converted, the overall experience of the first missionaries to Italy was ultimately a disappointment. Other, even less successful missionary efforts in predominantly Roman Catholic lands, such as Parley P. Pratt’s mission to South America in the early 1850s, and recurring efforts in Mexico and Chile, served to reinforce these negative views.[28] This specter loomed over Italy and was only dispersed in the post-1945 period when changing circumstances led to some gradual alterations in Mormon attitudes to Catholicism and to Italy.

Among many missionaries and leaders the difficulties of the first mission, combined with beliefs regarding the limited number of God’s elect in the world, contributed to a view that Italy was possessed of only a few chosen souls. These had been identified and had gathered to Zion, and therefore there was probably not a need to expend precious, limited missionary resources on the barren spiritual landscape of Italy. Mormon views on the spiritual landscape of Italy were not unique. Protestant missionaries, such as Seventh-day Adventist leader Ellen White, made similar observations: “This field is not an easy one in which to labor, nor is it one which will show immediate results.”[29] Even the great French poet Lamartine characterized Italy “as the land of the dead, culturally, politically, and spiritually.”[30]

These initial impressions, born of more than a decade of difficult labor, became the default Mormon view. When John Taylor presided over the European Mission later in the century, he went to Italy “in the hope that I might see some chance of making an opening in that country.” He wrote of this experience:

I regard Italy as in such a condition that there are but few chances at the present time for any opening to be made. The Italians are bound up in the religious faith that they have been reared in, or they are infidel almost entirely. I noticed in my attendance at the churches, that they are usually well filled with priests and beggars, and that few, comparatively speaking, of the well-to-do classes, or the middle classes, were paying any attention whatever to religious observance.[31]

As Taylor’s quote suggests, the character of the Mormon reaction to their labors in Italy was rooted in both their direct experience in proselytizing in the country, but also in their cultural baggage. These attitudes are crucial to understanding the long reluctance of Mormon leaders to reopen the Italian Mission. They derive from common perceptions among nineteenth-century Protestant Americans, who tended to view Italy and Italians with a complex combination of admiration and disdain, pity and awe.

Nineteenth-century Americans entertained two seemingly contradictory images of Italy: the romantic and the nativist. The romantic picture was a product of travelers and writers who looked upon Italy as a conservatory of all the cultural values of the old world: creative spontaneity, artistic sensibility, moral idealism, and worldly experience. It represented to American travelers a “quasi-sacred ground of art,” where they could “cultivate aesthetic consciousness.”[32] As Henry James, who himself lived in Italy for a time, wrote, “We go to Italy, to gaze upon certain of the highest achievements of human power,” which illustrate “to the imagination the maximum of man’s creative force. . . . So wide is the interval between the great Italian monuments and the works of the colder genius of neighboring nations, that we find ourselves willing to look upon the former as the ideal and perfection of human effort, and to invest the country of their birth with a sort of half-sacred character.”[33]

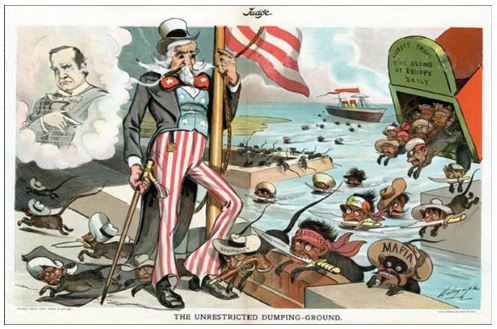

The striking flip side of this idealized Italy was the nativist picture. As more and more American tourists were traveling in Italy, large numbers of Italians were beginning to emigrate to America. In 1880 there were about forty-four thousand Italians in the United States, but by the first years of the twentieth-century, Italians represented one-fourth of all emigrants, and in a span of forty years they went from a marginal minority to the most visible immigrant group in the country. The Italy that most Americans encountered in their dealings with Italian immigrants was not the lofty land of James; rather, it was personified by the “young, robust, male, swarthy and emotional, frequently unlettered and unskilled, who worked in lowly jobs. . . . He quickly acquired the reputation of a sojourner with no sense of commitment to his host country.” Italians were perceived as being racially inferior: they were “the dark or swarthy one, . . . the untidy, non-self-improving one, natural resident of the slum and natural doer of the most unskilled labor, . . . the organized murderer, and thus . . . a ‘cause’ of violence in the world at large.”[34]

"The Unrestricted Dumping-Ground," Judge (1903), shows Italian immigrants swarming ashore in the United States "direct form the slums of Europe daily," bringing with them crime, anarchy, and Socialism. The image in the upper left is of President McKinley, assassinated by an anarchist two years earlier. Courtesy of www.flickr.com.

"The Unrestricted Dumping-Ground," Judge (1903), shows Italian immigrants swarming ashore in the United States "direct form the slums of Europe daily," bringing with them crime, anarchy, and Socialism. The image in the upper left is of President McKinley, assassinated by an anarchist two years earlier. Courtesy of www.flickr.com.

American views of Italy and Italians were schizophrenic, a complex combination of admiration for the seedbed of great civilizations, combined with disdain for the people, who were perceived as having become decadent and thus unworthy “descendants of their illustrious and proud ancestors.” Americans admired Italy’s cultural treasures and revered ancient Rome, “but detested the Italy of their time, dominated by the Papacy.” Italy was, as Mark Twain quipped, a “vast museum of magnificence and misery.”[35] James adored Italy’s “special beauty,” but he despised Italians, especially immigrants, whom he found physically and morally unclean. Similarly, Henry Blake Fuller admired Italy’s “high culture” but disdained “its social and moral decadence.”

These views permeated Protestant American society and thus inevitably flavored Mormon views as well. Like their fellow citizens, Mormon travelers were drawn to Italy, yet what they experienced alternately fascinated and repulsed them. Against the backdrop of monumental beauty, to Mormons the Italians “presented a sorry spectacle” of indolence, deceitfulness, squalor, and immorality.[36] When Brigham Young Jr. arrived in Bologna in 1863, he wrote:

I did not like this place at all. They show their vices a little too plain. As soon as we had arrived and fairly got the dust off from us, several ladies dressed in white presented themselves for us to pick from. They waited long and patiently but were disappointed at last. Such things as these make me disgusted with society as it exists at the present time, and long more earnestly for the society of virtuous men and women, which are only to be found as a community in my own loved home.[37]

This was not an isolated incident, and in the end, the son of the great church leader concluded that “if the soldiers, whores, and beggars were taken out of Italy, it would be without inhabitants except those who, like ourselves are merely transient residents.”[38] Young returned as president of the European Mission in 1864, and his views of Italy certainly influenced his decisions on where to allocate missionary resources.

Most Mormon travelers subscribed to the view of “admire Italy, despise the Italians.” In 1890, William Bowker Preston, son of the presiding bishop of the church, traveled through Italy on the way home from his mission. With his trusty Baedaker in hand, he immersed himself in the sights he had imagined since his youth. On his arrival in the capital, he rhapsodized, “At last the dream of my life is realized. I am in Rome.” Amid enthusiastic descriptions of the sights that filled dozens of pages in his journal, however, Preston also commented on the state of Italy and the Italians of his day: “I hope I’m not doing the poor Italians any wrong when I term them lazy, murderous and gossiping. I wouldn’t injure them for the world for they spring from that wonderful people who once ruled the world; and they were praiseworthy were they not?”[39]

In 1884, Ellen B. Ferguson—a physician, feminist, “great traveler,” and one of the most influential women in Utah Territory[40]—traveled to Italy and in the Mormon journal the Contributor wrote of passing from Switzerland to Italy:

We began to descend gradually by zigzag roads . . . into warmer weather, calmer air and softer scenery, until there lay before us, glittering in the dazzling midday sun, the blue expanse of Lake Como, the most beautiful of the Italian lakes. Could one live on the sense of beauty alone, the most artistic temperament, and the most vivid imagination might be filled to satiety with the exquisite loveliness of an Italian landscape. . . . The Italians as a race are indolent and effeminate. Ignorance, love of pleasure and superstition are their prominent characteristics. Of the moral dignity of man, they have but little conception. The soil, so prodigally fertile, produces, with but little labor all that is necessary for their support. The state of morals is lower than in any other country of Europe; what little virtue exists is found among the peasants.[41]

Suspicion of Italy and Italians persisted in the Mormon community. From 1870 on, almost the only mention of Italy in official church publications was of the political disorders of the peninsula: anarchists and socialists, and their roles in several high profile assassinations.[42] Underlying these views of Italians held by Mormons and Americans more generally loomed the issue of religion. Among nineteenth-century Americans, Italy’s wretchedness was a direct product of the deadening hand of its history and institutions, particularly the Catholic Church, which many Americans saw as “the great burden of Italian history.”[43]

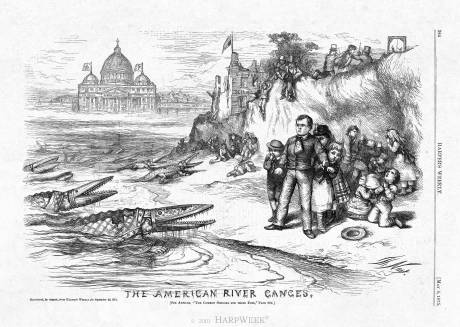

Thomas Nast, "The American River Ganges," Harper's Weekly (1875). Playing on fears in Protestant America that the pope intended to supplant democracy with the theocracy, this cartoon dipicts Roman Catholic bishops as alligators invading the shores of America and threatening its schoolchildren. Http://

Thomas Nast, "The American River Ganges," Harper's Weekly (1875). Playing on fears in Protestant America that the pope intended to supplant democracy with the theocracy, this cartoon dipicts Roman Catholic bishops as alligators invading the shores of America and threatening its schoolchildren. Http://

There was, of course, a long history of American ambivalence and open hostility to Catholicism, both to those within their own society as well as toward the institution of the papacy in Rome. Indeed, Arthur Schlesinger observed (with some exaggeration) that anti-Catholicism was “the deepest-held bias in the history of the American people.”[44] Anti-Catholicism included a combination of both religious and political sentiments and was widespread in the nineteenth and into the twentieth centuries. These views were a complex combination of historical sentiments that Americans inherited and perpetuated from their English Protestant ancestors and from their experiences in dealing with Irish and Italian Catholic immigrants, accentuated by the writings of travelers to Europe.[45] Mark Twain expressed this default Protestant American viewpoint: “I have been educated to enmity toward everything that is Catholic, and sometimes, in consequence of this, I find it much easier to discover Catholic faults than Catholic merits.”[46]

Almost all early Mormon converts were Protestants, and as a result they carried with them a certain religious and cultural baggage that informed their perceptions of the world and other religions. To be sure, most Mormons did not embrace the most extreme, virulently anti-Catholic attitudes which infected nineteenth-century American society; indeed, the history of Mormon relations and cooperation with Catholics in Utah is quite positive. Rather, Mormon bias against Catholicism was more theological in nature and was based on a sense that Catholics were less inclined to embrace the gospel than were the more spiritually pliant Protestants.[47]

The same attitude is also evident in the writings of the early Italian missionaries. When Lorenzo Snow arrived in what he described as “dark and benighted Italy,” he wrote:

My heart is pained to see [the Italians’] follies and wickedness—their gross darkness and superstition. I weep that the day of the Son of Man has come upon them unawares, so little are they prepared to receive the voice from on high. . . . They are clothed with darkness as with a garment, and, figuratively speaking, they know not their right hand from their left. . . . O Lord, let them become the objects of Thy compassion, that they may not all perish. . . . They do wickedly all the day long, and are guilty of many abominations. They have turned their backs upon Thee, though they kneel before the image of Thy Son, and decorate temples to Thy worship.[48]

Karl G. Maeser reported a similar sentiment in 1867 upon his visit to a Catholic canton in Switzerland:

Nothing struck us so much as the poverty, dirtiness, and filth of the villages, notwithstanding the countless arrangements of devotion at the road sides, and at all crossings of the streets, where crosses, little temples, &c., showed us that their faith in Christ had degenerated into the plainest idolatry, without sense or reason. There will be a poor show here, probably for a long time to come, for the light of truth.[49]

As Maeser’s quote suggests, while Mormons saw all religions as inimical to the restored truth, Catholics were perceived as suffering from a particularly bad case of spiritual blindness, much worse than their Protestant kin. Because of this, there was the sense that Catholics were unlikely to have the freedom of spirit and mind necessary to embrace the restored gospel.

Some Mormon leaders attributed meager Italian susceptibility to the gospel to racial and historical factors. In 1936, Reinhold Stoof, the former president of the South American Mission, reported that the majority of converts in Argentina were Italians and Spaniards. “There may be some who think that the ideal field of labor in which to find the scattered blood of Israel is the northern countries. For them it may be a consolation to know that a few centuries after Christ’s birth tribes from the north invaded Spain and Italy, and it may be that their remnants are the ones who today follow the voice of the Good Shepherd.”[50] Stephen L. Richards spoke a decade later about the diverse cultural makeup of Argentina in which “many nationalities were represented, with a preponderance of the brunette people from Spain, Italy, and the Mediterranean countries.” He wondered “how susceptible these people” would be to embracing the gospel, and what his experience might suggest about the possibility of taking the message to “Spain, Italy, Portugal, and adjacent countries. . . . I thought I could see in the disposition, customs and practices of these South Americans some of the reasons which have impeded gospel work among them.”[51]

Doubts about Catholic susceptibility to Mormonism are also evident in the geography of early missionary efforts. In the decades after the church was organized in 1830, the majority of the regions opened to missionary work were Protestant or possessed of a Protestant majority— Great Britain, Denmark, Norway, South Africa, Switzerland, and Germany. In England, converts came almost entirely from Protestant sects; a study of a sample of 298 converts reveals only two Roman Catholics.[52] Even in the few instances in which predominantly Catholic countries were opened, the missionary effort focused almost entirely to Protestants: of fifty-eight members on Malta, all except four were British, while converts in Paris, Le Havre, and Boulogne-Sur-Mer were almost entirely foreign-born Protestants, usually English or Swiss.[53] In 1867, when Octave Ursenbach visited the tiny branch in Paris, he reported that there was not a single French man or woman among them.[54] In Mexico the majority of the initial converts were Protestants, and this pattern persisted into the twentieth century: the first converts in South America in 1925 were six German-speakers.[55] Leonard Arrington attributes this to the fact that missionaries, who did not know the languages of the people they encountered, “worked primarily with British residents in these countries.”[56]

In the case of Italy, the missionaries came to the conclusion early on that the minuscule Protestant population would be their most likely source of success. Lorenzo Snow believed the Waldensians were “like the rose in the wilderness” and that they, not the vast Catholic majority, represented the best potential converts. He hoped that once a beachhead was established that the Waldensians would then become the means for taking the gospel to the Catholic population.[57]

Mormon attitudes toward Italians were accentuated by their doctrine of the Great Apostasy. The idea of a universal apostasy, often termed “the Great Apostasy,” is one of the linchpins of Mormonism and refers to what Mormons perceive as the “falling away” from Christ’s original church and his teachings in the centuries immediately following his crucifixion. For Mormons, Roman Catholicism held a privileged place in their apostasy narrative.[58]

Joseph Smith taught that “the Catholic religion is a false religion,” and this view was widespread among Mormons.[59] In 1841, for example, the Millennial Star editorialized, “The Roman Catholic Church or Mother Church is so corrupt, and so far apostatized from the Church, that a reformation was not only needed, but absolutely necessary,” and The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints claims “no affinity with the ‘Mother of Harlots or any of her daughters.’”[60] Until the last decades of the twentieth century, Roman Catholicism was also the most common exegetical gloss of Book of Mormon references to a “great and abominable church.”[61] This view of Roman Catholicism as the “Mother of Harlots” of John’s Revelation was not unique to the Mormon community: it was inherited from widely held views of the broader Protestant community.[62]

These views inhabited the mindset of Mormon missionaries as they set off to preach in Catholic lands. On his arrival in Italy in 1854, Samuel Francis wrote, “I had heard many times of the inquisition, and secret murders, and other diabolical means the Catholics made use of against those who opposed the Catholic faith.”[63] When Apostle John A. Widtsoe visited Rome, he reported on “the wonders of the city, made ugly by the evil that is centered there . . . [in] the heart of Catholicism.”[64] Such views were not limited to Italy: Moses Thatcher commented on Mexico, “Whatever may have been the condition of the Indian races occupying Mexico at the time of the conquest; we know that the thraldom [sic] of their bondage has, under the Catholic rule, been fearful since.”[65] And a 1929 article in a Mormon youth publication commented, “It is in the Catholic world that dictatorship mostly flourishes . . . Italy, Spain, Poland.”[66]

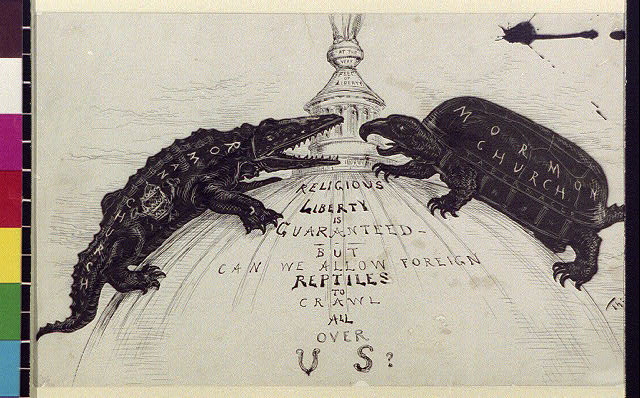

Political cartoon by Thomas Nast, portraying the Catholic and Mormon churches as malevolent reptiles threatening the United States. Published between 1860 and 1902. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Political cartoon by Thomas Nast, portraying the Catholic and Mormon churches as malevolent reptiles threatening the United States. Published between 1860 and 1902. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

In general, Mormon doctrinal anti-Catholicism did not translate into political or social discrimination. Utah Mormons generally got on quite well with their Roman Catholic neighbors, often even better than with the state’s Protestants.[67] In comparison to the anti-Catholic views of many mainstream Protestant denominations, Mormon views on Catholicism were quite benign.[68] Probably this was a product of the marginalized and often persecuted nature of both sects’ experiences in the often violently intolerant Protestant atmosphere of nineteenth-century America. Indeed, anti-Mormon and anti-Catholic literature regularly resorted to common images and caricatures, which effectively conflated the religions.[69] From the arrival of Utah’s first Roman Catholics in 1862, relations tended to be quite friendly: they used the Tabernacle to celebrate mass, and Brigham Young was instrumental in helping obtain land to construct a church of their own. Mormon leaders in St. George invited local Catholics to use their tabernacle and provided a choir that learned the “Kyrie,” “Gloria,” and “Credo” in Latin especially for a service.[70]

Conversely, Mormons benefitted from the Catholic presence in their community. Many Mormon children attended Catholic schools in Salt Lake City; in fact, they often outnumbered the Catholic children, and the nuns who taught them “experienced much kindness from the Mormons.”[71] The earliest hospital in Salt Lake City was the Hospital of the Holy Cross, which served many more Mormons than Catholics.[72] When the first Catholic church in Salt Lake City was dedicated, a large crowd attended, dominated by Mormons, who overflowed onto the entrance steps.[73] The first Catholic bishop of Utah, Lawrence Scanlan, while opposed to polygamy, cultivated “amicable relations” with the Saints. Following his death, a Mormon Apostle eulogized the bishop as “a saintly man who has won the sincere love and respect of every man and woman in the state of Utah by the true godliness of his life.”[74] In July 1915, US senator Reed Smoot organized “a special organ recital for a large delegation of Catholic visitors, including the papal delegate to the United States and the bishop-elect of the Roman Catholic diocese of Salt Lake City.”[75]

Despite their theological differences, Mormon leaders generally preached respect and tolerance of other faiths. Brigham Young stated, “Let us treat with candor the religious sentiments of all men, no matter if they differ from ours, or appear to us absurd and foolish. Those who hold them may be as sincere as we are in their convictions.”[76] A Catholic priest in 1882 reported, “As a rule the Mormons are no more bigoted against the Catholic, than against the Protestant, whatever bigotry they do possess is inherited by them from Protestant ancestary [sic] rather than taught to them by the Mormon Church.”[77]

Misperceptions were not limited to the Latter-day Saints: Following the exodus west, a number of Italians visited Utah and quite a few books were published that discussed aspects of the church, and many of these accounts perpetuated stereotypes about the Mormons.[78] After the Manifesto, for instance, many Italian writers, such as Romolo Bianchi, refused to accept that Mormons were no longer polygamists and continued to describe the church in its nineteenth-century context.[79] In 1912, Luigi Villari claimed the Mormons continued to practice polygamy,[80] and as late as 1925, Arnoldo Cipolla wrote that Mormonism was a “religious sect that inclines men toward polygamy.”[81] In a 1928 publication, Arnoldo Fraccaroli reported that Mormons not only continued to practice polygamy but killed cats which hunt mice on Sunday. This strange notion derives from a Reformation-era polemic about the Puritans, whom Fraccaroli conflated with the Mormons.[82] A notable exception was Irene di Robilant, who wrote a favorable account of Mormonism in 1929 which not only recognized that polygamy had ceased but also concluded that previous travel accounts had overemphasized the practice of plural marriage. She was convinced that Mormon polygamy had not been practiced for pleasure but to provide women with protection, family, and offspring.[83]

Contacts: 1865–1940

If Mormons did not officially reestablish a presence in Italy in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, there continued to be some scattered contacts. These included visits by travelers over the years, both official and not, and occasional brief missionary forays, none of which proved successful.

The late nineteenth century saw an explosion of Americans traveling to Europe: in 1870 their numbers were under 35,000, but by 1885 they had grown to 100,000 annually, and by 1914 almost 250,000. Among all European nations, Italy was one of Americans’ chief destinations.[84] In particular, scholars and the general public in this period maintained an inordinate fascination with the Italian Renaissance: Progressive-era Americans saw the United States as the culmination of the modernizing process that they traced to the piazzas of Renaissance Florence.[85] Italy was also a popular destination among Mormon travelers, due to both the church’s early involvement there, and to the enchantment Italy held for American society. This interest ensured that, while no official Mormon presence existed in Italy, many Mormons passed through in a variety of capacities.

It was not uncommon, for example, for missionaries to travel in Europe after being released, and invariably these travels included a visit to Italy. In 1902, for example, James and Frederick Barker, who were both serving missions in Europe, met and traveled to Italy. They visited all the major sights, and also traveled to the Waldensian valleys of northern Italy, where their mother, Margaret Stalle, one of the early Italian converts, was born. James Barker returned again in 1927 and in 1947 to do genealogical research.[86] In 1926, Elder Wayne Price Smith spent a week in Italy at the end of his missionary service. His first stop was Venice, where he visited the major sites, the Murano glass factories, and swam on the Lido before leaving “the Land of Water and beautiful Women” for Florence, Naples (with an obligatory stop at Pompeii), and then Rome, where he attended a public speech by Mussolini. While in Venice, Smith and his travel companion ran into two other Latter-day Saint missionaries, a Brother Leishman and Brother Schettler, who were traveling home from the Holy Land.[87]

Leaders and officials of the church also descended with some frequency on the peninsula. In 1872–73, Lorenzo Snow spent a month in Italy on his way to Palestine, where he had been charged to “dedicate and consecrate the land to the Lord” and to establish contacts “with men in position and influence in society.” His group of seven, including his sister Eliza R. Snow and President George A. Smith, visited Genoa, Milan, Venice, Florence, Naples, and Rome. They also passed through Turin, though Snow made no mention of his missionary labors there. His outspoken sister did write from Milan, “I see no hope for millions of people under the training of the ‘Mother of Harlots,’ and the influence of priestcraft, but through the ordinances of the dead.”[88] In 1884–85, John Henry Smith passed through Italy, visiting Milan, Genoa, Pisa, Florence, and Rome, of which he wrote, “We returned to our hotel, thankful that the dreams of our youth had been realized in standing in the eternal City.”[89] Members of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles presided over the European mission and regularly traveled to Italy: In 1902 Francis M. Lyman passed through on his return from visiting the Turkish mission, and rededicated Italy to missionary work.[90] Heber J. Grant, Lyman’s successor, visited Venice, Pompeii, and Rome with his wife, and found St. Peter’s “more wonderful than any building I have ever seen.”[91] A few years later, Rudger Clawson also traveled through the peninsula.[92]

Future church presidents also passed through Italy. In 1939, Joseph Fielding Smith and his wife, Jessie, were assigned to visit members of the church throughout Europe, and spent several weeks vacationing in Italy.[93] A few years earlier, Spencer W. Kimball and his wife, Camilla, traveled to Italy with an international Rotary group.[94]

In addition to missionaries and officials, other Mormons made the pilgrimage to Italy. In 1926, the renowned Mormon sculptor Avard T. Fairbanks was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship and spent two years in Rome and Florence with his wife and four young boys. He studied under Dante Soderini, a noted Italian sculptor, and executed a number of works, including a bronze for the Arciconfraternità della Misericordia.[95]

Attempts to Reestablish Missionary Work

While the Mormon presence in Italy was effectively over by 1870, there were still sporadic, brief missionary forays in the subsequent decades. Missionaries were occasionally sent to test the waters in Italy or returned as converts to visit and teach among family members. In the end none of these missionaries organized a new branch of the church, though they did encounter family and friends, some of whom eventually left the valleys and immigrated to Utah.[96]

In 1876, Joseph Toronto spent eighteen months in his hometown Palermo settling business matters and trying to find converts. He returned to Utah with a group of fourteen friends and relatives, including his sister Maria Grazia Scappatura and her husband and family, whose “boat and train expenses” he paid.[97] His visit attracted officials’ attention: In 1880, a US consular official in Palermo reported that “a few Mormons of Sicilian extraction” had come to put in order their financial affairs and to represent “the advantages that must necessarily accrue to all those who espouse their creed and emigrate to Utah.” Their efforts failed because, as the report mistakenly stated, “They refused absolutely to give pecuniary aid to all those who showed a disposition to accompany them.”[98]

Some of the original Waldensian converts also returned to Italy seeking additional converts. In 1879, Jacob Rivoir was called by church president John Taylor to return to the Piedmont valleys. He went to preach among family and friends for one year and was accompanied by his wife, Catherine Jouve. They were well received in the valleys, and Rivoir preached publicly to gatherings of Waldensians. By 1880, he was able to report to the Deseret News that he and his wife had baptized eleven people, including his elder brother Pierre’s family, and others were expressing interest. This success led Rivoir to ask for additional missionaries to assist in the work in Italy. In addition to working in the valleys, he traveled to Rome with a Brother Alfred Andre “to bear testimony in that great city.” Before his departure, Rivoir appointed several local elders to oversee the small Mormon community, and in fall 1880 he returned to Utah with his brother’s family of seven, including the uniquely named infant, Alma Abinadi Rivoir, born to Pierre’s daughter Giuditta.[99]

The following year, another Italian missionary serving in Switzerland, James Beus, visited the Waldensian valleys to work with family members and to encourage them to emigrate. In 1883 he was formally set apart as a traveling elder to Italy. Although he did not convert any of his relatives, he did encounter one cousin who emigrated to Utah (followed several years later by his family).[100] Later that year, Andrew Villet traveled alone to the valleys, where he labored for over six months. His letters and reports from the period make clear that he was the only member of the church in Italy. From the outset, while complimentary of the kindness and hospitality of the people, Villet had few illusions about the prospects for his work: He wrote, “It is not likely that the number of believers will be very numerous in this country, for they are but a small people who live in the tops of the mountains here. . . . However, I have hope that some will embrace the Gospel, and that the Lord will bless my labors.”[101] He held public and private meetings, passed out numerous pamphlets, and held informal religious discussions. While the Waldensians received him in their homes and fed him (during his six-month sojourn he slept outside only a few nights, once in a cave after being chased from a meeting after the audience discovered he was Mormon), he reported that ministers tried to prevent the people from receiving him and that they resorted to “abuse and denunciation in the newspapers.” He found some who accepted his message but lacked “the courage to embrace the Gospel,” either because of “a fear of persecution” or because of opposition from family members. A family of three were baptized in March, but “persecution soon overthrew them.” By June, Villet’s cautious optimism had turned to frustration. He reported that “so far as baptisms are concerned, I have no better prospect now than in the beginning; rather worse, indeed, for in the beginning I had hope, but now I have but little. I have now visited all the Protestants without finding a single soul willing to embrace the Gospel.”[102]

A decade later, James Bertoch, a fifty-three-year-old farmer who had converted and immigrated to Utah in 1854, returned to the Waldensian valleys as a missionary with his companion, Jules Giauque (Grangue). He spent much of his time visiting family members (some of whom were prominent citizens), sightseeing and researching his genealogy. He also preached to groups, proselytized door to door and engaged in spirited religious discussions.[103] Bertoch had minimal contact with the valley’s Catholic inhabitants: While staying at a “catholic taverne,” he had “a little conversation with the old lady of the house on religious topics and she seemed a little more inclined to listen than the catholic do as a rule and she toke [sic] one of our pamphlets.”[104] In February 1893, Bertoch and Grangues spent two weeks traveling in Florence and Rome, before parting company. Bertoch left for good in March, but during his time there he was warmly received as a returning son of the valleys, and many at least listened to his preaching. Ultimately, however, he did not convert anyone, though a number of Waldensians that he met during his sojourn did immigrate to Utah and North Carolina.[105]

The last missionary foray into Italy occurred in 1900 when Louis S. Cardon, president of the Swiss Mission and grandson of one of the original Waldensian converts, directed Daniel B. Richards to test the possibility of reinitiating missionary work. Richards was joined by President Cardon’s father, Paul Cardon, who came in part to do genealogical research. After several months of work, all the missionaries were able to accomplish was to hand out a few tracts and books and encounter a “real old lady” who had joined the church forty years prior, though she had little faith in Mormonism. In July of the same year, they returned to Switzerland, and Richards was sent to finish his mission in Germany.[106]

The overall failure of these occasional missionaries to attract converts or even interest in their message certainly contributed to the prevailing belief that what little blood of Israel dwelt in Italy had been gathered, and that future efforts would probably be futile. After Richards, no significant missionary effort was carried out in Italy until the early 1960s. There were occasional, passing contacts. For example, in 1905, an Elder Markow was released from the Syrian Mission, and on his trip home he passed through Florence in order “to find a man who has been recommended from Zion to a missionary visit.” We have no record of who the man was or whether Markow ever found him.[107] In 1931, forty-six year-old Elder Riccardo Robezzoli of the Swiss-German Mission crossed the Austrian border to work among his relatives near Trento. The day after his arrival, however, he was visited by the police: “They come to warn me that catholic was the religion of the state, not to venture to preach a new religion; the mob could become violent and I could end in jail.”[108] Another source suggests that sometime during the 1930s two missionaries were sent from Geneva to spread Mormon publications in Turin and Nice because “for the present we see no other means of scattering the seeds of righteousness.”[109]

Italy on the Horizon

Despite the limited activity in Italy from 1870 on, the country did not fall completely off the radar screen of church leaders. In 1905, President Hugh J. Cannon, the recently released president of the Swiss-German mission, reported in a general conference address on the condition of the work in Europe: “I expect in a very short time to hear that missionaries have been sent into the northern part of Italy, over the Alps from the French part of Switzerland. Many people have been gathered from that part of the country, and some prominent families now in Utah accepted the Gospel there. I firmly believe that many more will embrace the Gospel in that part of the world.”[110] When the French Mission was reopened in 1912, its jurisdiction included all “French speaking inhabitants of Belgium, Switzerland, and Italy,” but no missionaries were sent to Italy, and the French Mission was closed two years later at the outbreak of World War I.[111]

In a 1926 conference address, the Apostle Melvin J. Ballard, reporting on his experiences in South America, noted that in Argentina, several from the some two million Italians there were converted. This caused him to reflect on taking the gospel to Italy itself:

I am anxious, therefore, that in the period which yet remains to the Gentile nations to hear the gospel message, we shall send forth the help necessary, not only to those south American countries, but my soul has been turned toward Spain, since I have been in that South land, and also toward Italy. I do not feel we are justified in the opportunity we have given to either Spain or Italy or France or China or to other nations to hear the gospel: so I am looking forward for the time to come in the very near future when those lands shall be fully given the opportunity. Not many of them may come into the fold, and yet I believe that there is some of the blood of Israel in Spain and in Italy, and that the people are entitled to the opportunity of hearing the gospel before the day of judgment shall come.[112]

A former president of the South American Mission, Reinhold Stoof, reported in 1936 that the majority of the converts in that mission were “Italians and Spaniards.” Based on their positive experiences, the missionaries were eager “to establish a mission in Italy or Spain,” which, he believed, might still possess some of the blood of Israel.[113] A decade later in a conference address on his mission presidency in Argentina, James L. Barker, grandson of one of the original Waldensian converts, reported that most members there were still “of Spanish or Italian descent.” He believed that some of these individuals, who could not hear the gospel in their native lands, might have been led to Argentina, “not knowing why they went.” He concluded, “We have not preached the Gospel to the Italians, the Spaniards and others in Southern Europe. We sometimes have said perhaps they won’t accept it. They have never had a chance. . . . not one month’s work has ever been done in Italy, in the Italian language. Perhaps the fine members in Argentina may be a help and a means of spreading the Gospel to their countrymen in Europe.”[114]

There were other sporadic mentions of Italy in Church publications: The Encyclopedic History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, published in 1941, reported “there are still a few scattered members of the Church in Italy,” without specifying how many, where, or who they were.[115] The official church magazine, the Improvement Era, noted in 1927 the iconography of the friezes in the new temple in Mesa, Arizona, which depicted the gathering of Israel, including an Italian woman under an arbor, who “having become converted is pleading with the husband to join her.”[116] In general, however, Italy received little attention. After World War I, only passing references to Italy’s political situation appeared, such as the rise of Mussolini, which was generally seen as a positive development for backward Italy, or the controversial invasion of Ethiopia in 1935.[117] Elder Joseph F. Merrill, writing in the Millennial Star, editorialized against “deliberately slaughtering a relatively defenceless [sic] people” and attributed the invasion not to “the citizens of Italy [who] are a cultured, refined and lovable people. As a race many of them have always been marching with the vanguard of civilization. . . . We suspect it is really not Italy that we see [pushing the invasion of Ethiopia] but a single Italian with a mad complex.”[118]

Talk of reopening Italy to missionary work continued; Richard Cowan has suggested that the church leadership had decided to return to Italy in the 1920s, a period in which many missions were being reopened throughout Europe. Perhaps in preparation for this, the over eight hundred copies of the Book of Mormon printed in Italian in 1852 that had remained unassembled were finally bound. Five hundred signatures were found stored in Liverpool in 1929 by Apostle and European Mission president John A. Widtsoe, who had them bound and sent one hundred copies to California to use among Italian immigrants.[119]

In 1932, Elder Widtsoe traveled with his wife through Italy to study whether it might be reopened to missionary work. While in Rome he visited a Major Perilli, with whom he had corresponded after they met at the International Health Exposition in Berlin earlier that year. Perilli was enthusiastic about the Word of Wisdom and arranged for Widtsoe to meet with an important media figure, who, Widtsoe claimed, “felt that we should open our mission in Italy since many people were not fully satisfied with existing religious conditions.” Further evidence of this were the almost two hundred Italians who had written to Salt Lake and “were studying gospel” on their own since “no opportunity had been found to send missionaries at that time.”[120] In Naples, Widtsoe met with one of these investigators, Pasquale Gagliano, who had converted from Roman Catholicism and become a Baptist minister in southern Italy. In the course of preparing a series of lectures against Mormonism, he had corresponded with leaders in Salt Lake City and had become “convinced that in ‘Mormonism’ was truth that the Protestant sects had missed.” When the Widtsoes returned from Europe in 1934, his wife, Leah Dunford Widtsoe, gave a speech to a group of Latter-day missionary mothers entitled “The Missionary Possibilities in Italy.”[121]

Ultimately, the decision to reopen the Italian mission was delayed by a combination of factors, including the two world wars and the depression, which among other things, produced a shortage of missionaries.[122] If previously their absence was a product of Mormon cultural attitudes, Mussolini’s negotiation of the Lateran Accords in 1929 erected political and legal barriers that significantly altered the playing field for non-Catholic religions in Italy. This treaty resolved many of the disagreements that had plagued the Italian church/

The alliance between fascism and Catholicism created a more difficult atmosphere for non-Catholic religions in Italy than had previously been the case. Even before the accords, Mussolini restricted Protestant missionary efforts in Italy, and after 1929 the Catholic Church “expected the active support of the Regime in the restriction, if not the total suppression, of Protestant propaganda and proselytism.”[127] Indeed, one of the first disputes following the signing of the accords centered on the former’s complaint about “excessive tolerance” towards the so-called “permitted churches.”[128] One scholar has described this period as “the dark night of the Concordat.” Italy’s Protestants were viewed with suspicion and even as potential traitors because of their perceived association with foreign powers. The regime closely monitored the activities of all non-Catholic denominations and attempted to control them through a variety of means, including requiring governmental approval to appoint all pastors. A communication from the Ministry of the Interior in 1940 warned that Protestants “harbor a deep-seated hostility against Fascism, one which stems from their fundamental religious principles. It is necessary, therefore, to pay the most vigilant attention to their activities.” The Lateran accords, combined with the fascist regime’s vigilant suspicion, made evangelization by Italian Protestants and other religious groups interested in proselyting in Mussolini’s Italy nearly impossible.[129] From 1929 on, then, the door for the Mormons to return to Italy was effectively closed, and it would not reopen until the years following World War II.

Notes

[1] Portions of this chapter were previously published in Eric R. Dursteler, “One Hundred Years of Solitude: Mormonism in Italy, 1867–1964,” International Journal of Mormon Studies 11 (2011): 119–48.

[2] Anthony Cardoza, “Cavour and Piedmont,” in Italy in the Nineteenth Century 1796–1900, ed. John A. Davis (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000), 118; Michael W. Homer, “Discovering Italy: The Mormon Mission and the Reaction of the Kingdom of Sardegna, the Catholic Church, and Her Protestant Rivals” (unpublished paper), 9.

[3] Michael W. Homer, “LDS Prospects in Italy for the Twenty-first Century,” Dialogue 29 (Spring 1996): 151–52.

[4] Homer, “LDS Prospects in Italy,” 151–52.

[5] Massimo Introvigne, I Mormoni (Vatican City: Libreria editrice vaticana, 1993), 195–97; Homer, “LDS Prospects in Italy,” 153; Franco Garelli, Religione e chiesa in Italia (Bologna: Il Mulino, 1991), 12–15.

[6] See, for example, A. Bryan Weston, “Europe,” in Encyclopedia of Latter-day Saint History, ed. Arnold K. Garr, Donald Q. Cannon, and Richard O. Cowan (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2000), 344–45; Richard G. Wilkins, “All’Italiana—The Italian Way,” New Era, March 1978, 30; Ralph L. Cottrell Jr., “A History of the Discontinued Mediterranean Missions of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints” (master’s thesis, Brigham Young University, 1963), 69.

[7] The most perceptive analysis of the shortfall of the first mission is in James R. Moss et al., eds., The International Church (Provo, UT: Brigham Young University, 1982), 32.

[8] Giorgio Tourn, You Are My Witnesses: The Waldensians across 800 Years (Turin: Claudiana, 1989), 215.

[9] John P. Diggins, Mussolini and Fascism: The View from America (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1972), 7.

[10] Valdo Vilnay, Storia dei valdesi (Turin: Claudiana, 1980), 3:75; Tourn, You Are My Witnesses, 203.

[11] Alice A. Kelikan, “The Church and Catholicism,” in Liberal and Fascist Italy, 1900–1945, ed. Adrian Lyttelton (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002), 45–58; Harry Hearder, Italy in the Age of the Risorgimento, 1790–1870 (London: Longman, 1980), 288–89; Kertzer, “Religion and Society,” 183, 193–94; see also Martin Clark, Modern Italy, 1871–1982 (London: Longman, 1984), 81–88.

[12] Vilnay, Storia dei valdesi, 3:75–9; Kertzer, “Religion and Society,” 201; also Michael W. Homer, “The Church’s Image in Italy from the 1840s to 1946: A Bibliographic Essay,” BYU Studies 31, no. 2 (1991): 87; Binchy, Church and State in Fascist Italy, 594.

[13] Tourn, You Are My Witnesses, 172, 207; Giorgio Spini, Italia liberale e protestanti (Turin: Claudiana, 2002), 40.

[14] Homer, “The Church’s Image in Italy,” 88; The History of the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (Independence, MO: Herald House, 1906), 4:16–17, 22, 59–60, 73.

[15] See the very detailed discussion of this in Vilnay, Storia dei valdesi, 3:79–173; also Spini, Italia liberale e protestanti, 151–220.

[16] Vilnay, Storia dei valdesi, 3:234–37, 241; Tourn, You Are My Witnesses, 208, 210, 222.

[17] Spini, Italia liberale e protestanti, 85; Clark, Modern Italy, 31.

[18] James B. Allen and Glen M. Leonard, The Story of the Latter-day Saints, 2nd ed. (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1992), 397–98.

[19] Foreign Relations of the United States, 1879 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1879), 601–4.

[20] B. H. Roberts, A Comprehensive History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 6 vols. (Salt Lake City: Deseret News Press, 1940), 4:124; Leonard J. Arrington, “Historical Development of International Mormonism,” Religious Studies and Theology 7 (1987): 14; Allen and Leonard, The Story of the Latter-day Saints, 322, 344; Deseret Morning News 2005 Church Almanac (Salt Lake City: Deseret News, 2005), 635.

[21] Thomas G. Alexander, Mormonism in Transition: A History of the Latter-day Saints, 1890–1930 (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1996), 5, 216–18; Moss, The International Church, 71; Allen and Leonard, The Story of the Latter-day Saints, 506.

[22] Allen and Leonard, The Story of the Latter-day Saints, 322–23.

[23] Eliza R Snow Smith, Biography and Family Record of Lorenzo Snow: One of the Twelve Apostles of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (1884; repr., Salt Lake: Zion’s Bookstore, 1975), 496–97.

[24] Alexander, Mormonism in Transition, 216–17; Allen and Leonard, The Story of the Latter-day Saints, 441–42, 459–60.

[25] Arrington, “Historical Development of International Mormonism,” 14– 15; Allen and Leonard, The Story of the Latter-day Saints, 322, 343–44, 396, 426, 460; Deseret Morning News 2005 Church Almanac, 635.

[26] David J. Whittaker, “Mormon Missiology: An Introduction and Guide to the Sources,” in The Disciple as Witness: Essays on Latter-day Saint History and Doctrine in Honor of Richard Lloyd Anderson, ed. Stephen D. Ricks et al. (Provo, UT: FARMS, 2000), 463–64; Allen and Leonard, The Story of the Latter-day Saints, 396, 426, 459–60; R. Lanier Britsch, “Missions and Missionary Work,” in Encyclopedia of Latter-day Saint History, 760; Alexander, Mormonism in Transition, 212; F. LaMond Tullis, “Reopening the Mexican Mission in 1901,” BYU Studies 22, no. 4 (1982): 441.

[27] Whittaker, “Mormon Missiology,” 463–64; R. Lanier Britsch, “Missions and Missionary Work,” in Encyclopedia of Latter-day Saint History, 760; Alexander, Mormonism in Transition, 235–36; Maureen Ursenback Beecher and Paul Thomas Smith, “Snow, Lorenzo,” in Encyclopedia of Mormonism, ed. Daniel H. Ludlow (New York: Macmillan, 1992), 3:1370.

[28] Gordon Irving, “Mormonism and Latin America: A Preliminary Survey,” in Task Papers in LDS History, no. 10 (Salt Lake City: Historical Department of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1976), 7–20; A. Delbert Palmer and Mark L. Grover, “Hoping to Establish a Presence: Parley P. Pratt’s 1851 Mission to Chile,” BYU Studies 38, no. 4 (1999): 115–31.

[29] D. A. Delafield, Ellen G. White in Europe, 1885–1887 (Washington, DC: Review and Herald Publishing Association, 1975), 138.

[30] Tourn, You Are My Witnesses, 164–66.

[31] John Taylor, in Journal of Discourses, 26:177.

[32] Diggins, Mussolini and Fascism, 6–8; Richard H. Brodhead, “Strangers on a Train: The Double Dream of Italy in the American Gilded Age,” Modernism/

[33] Brodhead, “Strangers on a Train,” 13; Alexander DeConde, “Endearment or Antipathy? Nineteenth-Century American Attitudes toward Italians,” Ethnic Groups 4 (1982): 132–33; Carl Maves, Sensuous Pessimism: Italy in the Work of Henry James (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1973), 5.

[34] DeConde, “Endearment or Antipathy?,” 138–39; Brodhead, “Strangers on a Train,” 2, 6.

[35] Angelo Principe, “Il Risorgimento visto dai Protestanti dell’alto Canada 1846–1860,” Rassegna storica del risorgimento 66 (1979): 152; Diggins, Mussolini and Fascism, 6, 8.

[36] Diggins, Mussolini and Fascism, 10.

[37] Dean C. Jessee, ed., Letters of Brigham Young to His Sons (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1974), 47.

[38] Jessee, Letters of Brigham Young, 47.

[39] William Bowker Preston, “Journal 1890 January–October,” MS 7557, Church History Library.

[40] Jill Mulvay Derr, Janath Russell Cannon, and Maureen Ursenbach Beecher, Women of Covenant: The Story of Relief Society (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1992), 107, 134; Janet Peterson and LaRene Gaunt, Elect Ladies (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1990), 55–56; Claire Wilcox Noall, “Utah’s Pioneer Women Doctors,” Improvement Era 42 (January–August 1939).

[41] Ellen B. Ferguson, “Scenes in Italy,” Contributor 6 (October 1884): 12–14.

[42] Millennial Star, 2 July 1894, 423; Millennial Star, 9 July 1894, 446; Millennial Star, 27 August 1894, 551; Millennial Star, 3 September 1894, 567.

[43] Diggins, Mussolini and Fascism, 10.

[44] John Tracy Ellis, American Catholicism (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1969), 159.

[45] Howard R. Marraro, “Il problema religioso del Risorgimento italiano visto dagli americani,” Rassegna storica del risorgimento 43 (1956): 463–64, 468.

[46] Mark Twain, Innocents Abroad (Hartford, CT: American Publishing Company, 1869), 599–600.

[47] Irving, “Mormonism and Latin America,” 7.

[48] Smith, Biography and Family Record of Lorenzo Snow, 134, 120.

[49] Millennial Star, 12 October 1867, 652.

[50] Reinhold Stoof, in Conference Report, April 1936, 87–89.

[51] Stephen L. Richards, in Conference Report, October 1948, 144–51.

[52] Malcolm R. Thorp, “The Religious Background of Mormon Converts in Britain, 1837–52,” Journal of Mormon History 4 (1977): 52–54, 58–60; also Tim B. Heaton, Stan L. Albrecht, and J. Randal Johnson, “The Making of British Saints in Historical Perspective,” BYU Studies 27, no. 2 (1987): 121–22.

[53] Cottrell, “History of the Discontinued Mediterranean Missions,” 42; Christian Euvrard, Louis Auguste Bertrand (1808–1875): Journaliste socialiste & Pionnier mormon (Le Mans: Impri’Ouest, 2005), 140–41. See also John DeLon Peterson, “The History of the Mormon Missionary Movement in South America to 1940” (master’s thesis, University of Utah, 1961), 5–6.

[54] Moss, The International Church, 40–41; Millennial Star, 21 September 1867, 605.

[55] Tullis, “Reopening the Mexican Mission,” 446; Alexander, Mormonism in Transition, 235; Peterson, “The History of the Mormon Missionary Movement in South America,” 44–102.

[56] Arrington, “Historical Development of International Mormonism,” 12–13.

[57] Homer, “LDS Prospects in Italy,” 139; Homer, “Discovering Italy,” 1, 3, 10.

[58] On this see, Eric R Dursteler, “Inheriting the ‘Great Apostasy’: The Evolution of Mormon Views on the Middle Ages and the Renaissance,” Journal of Mormon History 28 (Fall 2002): 23–59.

[59] Joseph Fielding Smith, ed., Teachings of the Prophet Joseph Smith (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1976), 375.

[60] Millennial Star, January 1841, 235, 236–38; see also Times and Seasons, 15 June 1842, 815–16.

[61] The persistence of Mormon anti-Catholic ideas is evidenced in the controversy over the identification of “the church of the devil” and “the great and abominable church” of 1 Nephi 13–14 with Roman Catholicism in the first edition (1958) of Bruce R. McConkie’s Mormon Doctrine. On this, see David John Buerger, “Speaking with Authority: The Theological Influence of Elder Bruce R. McConkie,” Sunstone 9 (March 1985): 9; Prince and Wright, David O. McKay and the Rise of Modern Mormonism, 49–53. Also, Gregory Prince, “A turbulent coexistence: Duane Hunt, David O. McKay, and a Quarter-Century of Catholic-Mormon Relations,” Journal of Mormon History 31 (2005), 143–63. For a very early example of the conflation of Catholicism with the “great and abominable church,” see Winchester, History of the Priesthood, 79–82.

[62] Fawn M. Brodie, No Man Knows My History: The Life of Joseph Smith the Mormon Prophet (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1960), 59; Thomas F. O’Dea, The Mormons (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1957), 34; Whitney R. Cross, The Burned-Over District: The Social and Intellectual History of Enthusiastic Religions in Western New York, 1800–1850 (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1950), 232–33.

[63] Samuel Francis, Journal, 69–70, cited in Homer, “Discovering Italy,” 29. This voyeuristic fascination with the Inquisition was shared by many travelers, including Twain, Innocents Abroad, 274–75.

[64] John A. Widtsoe, In a Sunlit Land (Salt Lake City: Deseret News, 1952), 206.

[65] Kenneth W. Godfrey, “Moses Thatcher and Mormon Beginnings in Mexico,” BYU Studies 38, no. 4 (Winter 1999): 139–40.

[66] J. M. Sjodahl, “Signs of the Times,” Juvenile Instructor 64 (March 1929): 145–46.

[67] Alexander, Mormonism in Transition, 253; Francis J. Weber, “The Church in Utah, 1882. A Contemporary Account,” Records of the American Catholic Historical Society 81 (1970): 200; Bernice Maher Mooney and Jerome C. Stoffel, Salt of the Earth: The History of the Catholic Diocese of Salt Lake City, 1776–1987 (Salt Lake City: Catholic Diocese of Salt Lake City, 1987), 40–41, 46–47; Bishop Scanlan, The Catholic Church in Utah (Salt Lake City: Intermountain Catholic Press, 1909), 331–33.

[68] J. Tremayne Copplestone, Twentieth-Century Perspectives (The Methodist Episcopal Church, 1896–1939), vol. 4 of History of Methodist Missions (New York: The Board of Global Ministries, 1973), 378–98.

[69] Thomas J. Carty, A Catholic in the White House: Religion, Politics, and John F. Kennedy’s Presidential Campaign (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004), 11–25; Gary L. Bunker and Davis Bitton, The Mormon Graphic Image, 1834–1914: Cartoons, Caricatures, and Illustrations (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1983), 82–86.

[70] Allen and Leonard, The Story of the Latter-day Saints, 349; Scanlan, The Catholic Church in Utah, 282, 330–34; Mooney and Stoffel, Salt of the Earth, 40–47; Bernice Maher Mooney, “The Cathedral of the Madeleine: The Building and Embellishment of a Historic Place,” Utah Historical Quarterly 49 (Spring 1981): 110–12; Francis J. Weber, “Father Lawrence Scanlan’s Report of Catholicism in Utah, 1880,” Utah Historical Quarterly 34 (1966): 289.

[71] Mooney, “The Cathedral of the Madeleine,” 112; Francis J. Weber, “Catholicism among the Mormons,” Utah Historical Quarterly 44 (1976): 143; Francis J. Weber, “The Church in Utah, 1882. A Contemporary Account,” Records of the American Catholic Historical Society 81 (1970): 202; Raymond H. Schmandt, “Pope Pius IX’s Requiem in Salt Lake City, Utah, February 24, 1878,” Records of the American Catholic Historical Society 81 (1970): 212. See also Robert J. Dwyer, “Catholic Education in Utah,” Utah Historical Quarterly 43 (1975): 362–65.

[72] Weber, “Catholicism among the Mormons,” 147.

[73] Mooney and Stoffel, Salt of the Earth, 49–51; Mooney, “The Cathedral of the Madeleine,” 112. A large number of church members also attended the Requiem Mass for Pius IX in 1878; Schmandt, “Pope Pius IX’s Requiem,” 211–12.

[74] Mooney, “The Cathedral of the Madeleine,” 112; Weber, “Catholicism among the Mormons,” 146–47.

[75] Alexander, Mormonism in Transition, 253.

[76] Brigham Young, in Journal of Discourses, 19:194.

[77] Weber, “The Church in Utah, 1882,” 202.

[78] A sample of these includes Samuele Mazzuchelli (1844), Enrico Besana (1869, 1871), Francesco Vavaro Pojero (1878), Giovanni Vigna dal Ferro (1881), Carlo Gardini (1887), Augusto Torlonia (1892), Leonetto Cipriani (1934), Giuseppe Fovel (1864), Emilio Teza (1874), and the adventure stories of Emilio Salgari and a fantasy travel account published in the Jesuit Jiumal La Civiltà Caltolica, (see Francesco Saverio Rondina, L’Emigrante Italiano (Roma: La Griltà Caltolica, 1892). On these accounts generally, see Michael W. Homer, On the Way to Somewhere Else (Spokane: Arthur H. Clark Company, 2006).

[79] Romolo Bianchi, L’Evoluzione religiosa nella società Americana (Cremona: Tip. Sociale, 1910), 182–98.

[80] Luigi Villari, Gli Stati Uniti d’America e l’emigrazione Italiana (Milan: Fratelli Treves, 1912), 208.

[81] Arnoldo Cipolla, Nell’ America del Nord: Impressioni di viaggio in Alaska, Stati Uniti e Canada (Turin: G. B. Paravia e Co., 1925), 234.

[82] Arnoldo Fraccaroli, Vita d’America (Milan: Fratelli Treves, 1928), 14–15, 175–76.

[83] Irene di Robilant, Vita Americana (Turin: Fratelli Bocca, 1929), 91–108.

[84] Christopher Endy, “Travel and World Power: Americans in Europe, 1890–1917,” Diplomatic History 22 (1998): 567–69, 582.

[85] Anthony Molho, “Italian History in American Universities,” in Italia e Stati Uniti concordanze e dissonanze (Rome: Il Veltro, 1981), 205–8; “American Historians and the Italian Renaissance: An Overview,” Schifanoia 8 (1990): 15–16; “The Italian Renaissance: Made in the USA,” 263–94; Muir, “The Italian Renaissance in America,” 1096.

[86]“Barker, Frederick Journals (1902–1905),” MS 7979, Church History Library; Archibald F. Bennett, “Triumph in the Alps,” Instructor 93 (August 1958): 227.

[87] Wayne Price Smith, “Missionary Papers 1924–1926,” vol. 3, MS 14837, Church History Library. See also “Journal of Joseph Woodward Murray, Mission Journal May 1907–November 1908; September–October 1909,” MS 13742, Church History Library.

[88] George A. Smith, Lorenzo Snow, Paul A. Schettler, and Eliza R. Snow, Correspondence of Palestine Tourists (Salt Lake City: Deseret News Steam Printing Establishment, 1875), 106–7. See also Heidi S. Swinton, “Lorenzo Snow,” in The Presidents of the Church, ed. Leonard J. Arrington (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1986), 167; Homer, “The Church’s Image in Italy,” 88; and Homer, “Discovering Italy,” 27. Also Lorenzo Snow to His Wife, Jan 3, 1873 from Milan, MS 3187 2, Church History Library.

[89] Jean Bickmore White, Church, State, and Politics: The Diaries of John Henry Smith (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1990), 128–30.

[90] Andrew Jensen, Latter-day Saint Biographical Dictionary, vol. 4 (Salt Lake City: The Andrew Jenson History Company, 1936), 737; Dean B. Cleverly, “Missions,” in Encyclopedia of Mormonism, 2:917; Albert R. Lyman, Francis Marion Lyman, 1840–1916 (Delta, UT: Melvin A. Lyman, 1958), 157–59; Louisa Maria Tanner, “Postcards 1901–1906,” MS 7358.

[91] Ronald W. Walker, “Heber J. Grant’s European Mission, 1903–1906,” Journal of Mormon History 14 (1988): 29.

[92] Rudger Clawson to Hyrum Valentine, 23 Jan 1913, MS 1340, Hyrum Washington Valentine Papers, 1911–40.

[93] Francis M. Gibbons, Joseph Fielding Smith: Gospel Scholar, Prophet of God (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1992), 271–73; Francis M. Gibbons, Dynamic Disciples, Prophets of God: Life Stories of the Presidents of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1996), 228.

[94] Edward L. Kimball and Andrew E. Kimball, Spencer W. Kimball: Twelfth President of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1977), 163.

[95] Ellen Greer, “Great Art Can Be Beautiful,” Improvement Era 9 (September 1950): 716–18, 742; Eugene F. Fairbanks, A Sculptor’s Testimony in Bronze and Stone: The Sacred Sculpture of Avard T. Fairbanks (Salt Lake City: Publishers Press, 1994), 3.

[96] Homer, “LDS Prospects in Italy,” 142.

[97] Homer, “The Church’s Image in Italy,” 88, 99; Homer, “LDS Prospects in Italy,” 152; Joseph Toronto: Italian Pioneer and Patriarch (Salt Lake City: Toronto Family Organization, 1983), 25–26; Kate Carter, Heart Throbs of the West (Salt Lake City: Daughters of Utah Pioneers, 947), 4:283.

[98] Foreign Relations of the United States, 1880 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1880), 644–45.

[99] Millennial Star, 19 January 1880, 47; Millennial Star, 12 April 1880, 230–31; Millennial Star, 10 May 1880, 298; Millennial Star, 21 June 1880, 397; Millennial Star, 11 October 1880, 651; Gordon Irving, “Jacob Rivoir’s Homeland,” Church News, 12 February 1980, 16; Homer, “The Church’s Image in Italy,” 89; Homer, “Discovering Italy,” 27; Diane Stokoe, “The Mormon Waldensians,” (master’s thesis, Brigham Young University, 1985), 51; Comune di San Germano Chisone, r. 130, n. 24.

[100] Millennial Star, 30 January 1882, 77; Millennial Star, 8 January 1883, 27–28.

[101] Millennial Star, 19 February 1883, 125; Millennial Star, 21 January 1884, 46; Millennial Star, 28 January 1884, 55.

[102] Millennial Star, 7 April 1884, 220–21; Millennial Star, 30 June 1884, 411–12.

[103] Millennial Star, 19 September 1892, 602–3; “James Bertoch Missionary Journal,” MSS B 1572, James Bertoch Family Papers, 1862–1900, Utah State Historical Society, Salt Lake City, A7–A9, B2–B4, C5–C7. See also Michael W. Homer and Flora Ferrero, eds., James Bertoch Missionary Journal and Letters to his Family, June 22, 1892 to March 25, 1893 (Salt Lake City: Prairie Dog Press, 2004).

[104]“James Bertoch Missionary Journal,” C3.

[105] Michael W. Homer, “An Immigrant Story: Three Orphaned Italians in Early Utah Territory,” Utah Historical Quarterly 70, no. 3 (Summer 2002); mission journal of James Bertoch, 30 June 1892, copy in possession of author; Millennial Star, 19 September 1892, 602–63.

[106] Cottrell, “History of the Discontinued Mediterranean Missions,” 29–30; Homer, “The Church’s Image in Italy,” 89; James A. Toronto, “Italy,” in Encyclopedia of Latter-day Saint History, 556–58.

[107] 1 November 1905, in Joseph W. Booth, “The Journals of Joseph Wilford Booth, 1886–1928,” MS 155, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT.