Reopening the Italian Mission, 1965-71

James A. Toronto, Eric R Dursteler, and Michael W. Homer, "Reopening the Italian Mission, 1965-71," in Mormons in the Piazza: History of the Latter-Day Saints in Italy, James A. Toronto, Eric R. Dursteler, and Michael W. Homer (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2017), 259-314.

Mormon evangelization of Italy resumed against a backdrop of postwar social change and political unrest that would both propel and hinder church growth.[1] The first missionaries returning to Italy were initially ill prepared but earnest in their efforts to attract converts, employing a variety of innovative strategies to introduce their message and dispel widespread stereotypes about Mormonism in the Italian public square. Mission leaders sought ways to provide adequate training for young missionaries living in isolated conditions and struggling to adapt to the rigors of missionary life in a different culture. At the same time, new converts required support as they faced challenges of their own: the social cost of being among a small minority of Italians to embrace a foreign faith and the difficulties inherent in adjusting to their new religious identity and community.

Map of Italy showing some of the major cities where LDS missionary activity and church growth occurred, 1965-present. Courtesy of BYU studies.

Map of Italy showing some of the major cities where LDS missionary activity and church growth occurred, 1965-present. Courtesy of BYU studies.

The “Wild West” of Missionary Work

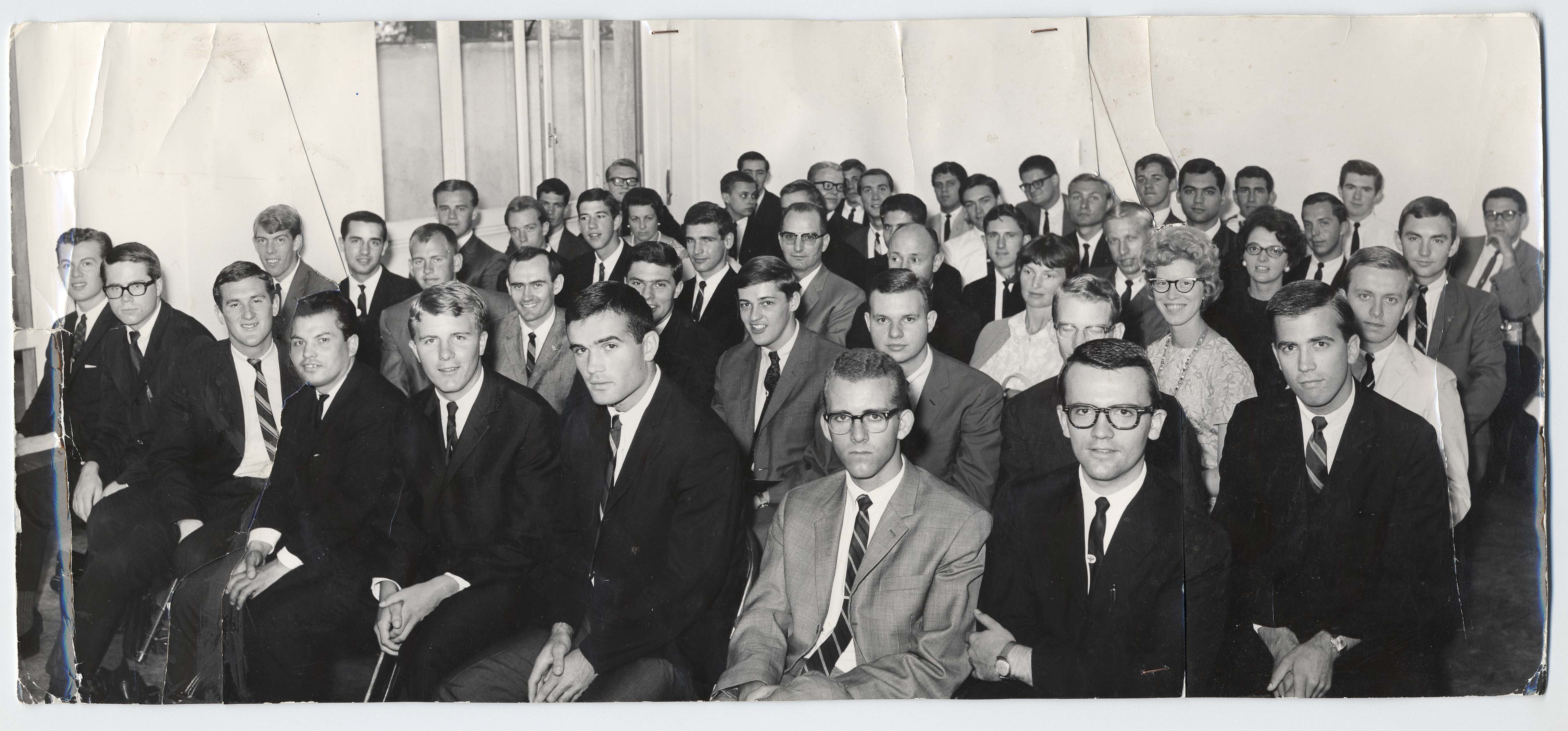

In the winter cold of Saturday morning, 27 February 1965, twenty-two missionaries gathered at the LDS chapel in Lugano, Switzerland, in the southern canton of Tesin.[2] They had traveled there from three different European missions—South German, Bavarian, and Swiss—and had been instructed to fast and pray in preparation for this important meeting. Most of these elders had previously proselytized in Italian-speaking zones in Germany and Switzerland and, because of their firsthand experience with Italian language and culture, had been reassigned to form the vanguard for reopening formal missionary work in Italy. After the missionaries shared testimonies and feelings about their new assignment, John M. Russon, who had been called as the president of the Swiss Mission in 1962, gave the group final instructions. Then they split up and headed south toward Italy, some taking the train and others squeezing into the mission’s two Volkswagen minibuses, with Russon riding in one.

After arriving at their rendezvous point, the Stazione Centrale in Milan, the missionaries traveling by bus received a sobering introduction to their new field of labor when they learned that “the suitcases of about three of the elders were stolen right out of the mission bus, right in front of the train station.” The office staff back in the mission home in Zurich found some humor in the inauspicious incident, opining in the mission newsletter that “apparently the devil is determined that these [missionaries] shall proceed without purse or scrip.”[3]

This theft did little to dampen the elders’ enthusiasm. Most had been preparing for and anticipating their arrival in Italy for weeks. The missionaries dispersed to seven cities—Pordenone, Vicenza, Verona, Brescia, Milan, Turin, and Como-Varese—that Russon had divided into the Milan, Turin, and Vicenza districts of the Swiss Mission’s new Italian Zone (headquartered in Milan). These cities had been chosen in part because a few Italian or American Mormons were already living there who could assist the missionaries. After registering at the local police station (questura) and locating a place to live, the missionaries began the challenging task of introducing a new faith in Italy’s religious landscape.

The first group of twenty-two missionaries gather in Lugano, Switzerland, preparing to enter Italy in February 1965. President John Russon in kneeling on the bottom row, far left. Courtesy of Church History Library.

The first group of twenty-two missionaries gather in Lugano, Switzerland, preparing to enter Italy in February 1965. President John Russon in kneeling on the bottom row, far left. Courtesy of Church History Library.

The “spot tracting” carried out by President Russon and two elders on an earlier trip to Italy suggested that the Italians would be receptive to the missionaries’ message; and from the first day of proselytizing, this proved to be the case. With very limited knowledge of their new field of labor and few resources or networks to rely on, the missionaries resorted mostly to tracting—knocking on doors in residential areas—as their main method of locating potential converts. It became customary for missionaries to keep a card file or written log of names contacted while tracting so that missionaries who worked in the same area later could refer to the previous notes and have some idea of which buildings and doors they might revisit. Despite the long hours and physical demands of going door-to-door, the elders generally reported a sense of satisfaction at finding so many people who were willing to listen, treat them with kindness, share meals with them, and engage in religious discussion.

Besides noting the curiosity and hospitality of the Italians, the missionaries often commented on the contrasts in living conditions that they encountered while tracting through a cross-section of Italian society of the mid-sixties. There were private villas of wealthy elites; apartment buildings guarded by portieri (doormen) of the growing upper and middle classes; government housing projects; and sprawling urban slums of those who had recently migrated from the economically depressed regions of southern Italy to the industrial and commercial centers in the north where job opportunities were more plentiful. The missionaries arrived at a time of rapid transformation in Italian society, as mass migrations from south to north brought about isolation, dislocation, dissolution of kinship ties, loss of status and identity, and a search for meaning and belonging in life. It was a time of social tensions and political ferment, with Italians struggling to cope with the changes that were reshaping the structure and assumptions of traditional Italian life.

Studies of this era document the “dramatic” cultural, psychological, and social impact of these changes as Italy experienced both the benefits of the post-war “economic miracle” but also unrest and alienation stemming from mass movement of populations, appalling living conditions, and discrimination against immigrants in northern cities.[4] Paul Ginsborg has asserted that this period of inter-regional migration was “unparalleled” in Italy’s history. From 1955 to 1971, more than nine million Italians “left their places of birth, left their villages where their families had lived for generations, left the unchanging world of rural Italy, and began new lives in the booming cities and towns of the industrial nation.” The southern regions of Puglia, Sicily, and Campania “suffered the greatest haemorrhages of population,” and the major industrial centers of central and northern Italy “were transformed by this sudden influx.”[5] Guido Crainz described these changes as an “essential aspect” of the times that “radically shaped the ways of living and working, of producing and consuming, of thinking and dreaming of the Italians.”[6] In sum, these turbulent circumstances and the ecumenical reforms implemented by Vatican II helped create a relatively open, receptive religious climate that the missionaries enjoyed during their first months in Italy.[7]

Missionaries began proselytizing in Rome in January 1967. Here the missionaries use a street board to attract the attention of passerby in Piazza Cavour. Courtesy of Noel Zaugg.

Missionaries began proselytizing in Rome in January 1967. Here the missionaries use a street board to attract the attention of passerby in Piazza Cavour. Courtesy of Noel Zaugg.

Reminiscences of missionaries provide a picture of the early years of the Italian Mission. The experience of Bruno Vassel, who with his companion opened proselytizing in Verona in February 1965, was typical of those early halcyon days. He was initially called to the Bavarian Mission in August 1963 and labored for several months in Nuremberg as part of the Italian-speaking zone before his transfer to Italy. Accustomed to dealing with constant rejection in his previous work in Germany, he found his new assignment a refreshing change: “Italy was just heaven—it was the celestial kingdom. We talked with 50 people and made 15 appointments for teaching in one day. And day after day, city after city, we filled our appointment books by tracting.” He also gradually realized that there were linguistic and cultural nuances that would require some adjustments in their approach to proselytism. It soon became clear that the Italian language he had absorbed while proselytizing in Germany among Italian gastarbeiter (guest workers, allowed in Germany on limited visas only to supplement the labor force) was more of a dialect, a fact that introduced him to north-south differences, an underlying tension in Italian society. While he and his companion were tracting one day, a woman listened to them for a few minutes and then responded indignantly: “Why are you speaking like Sicilians? Don’t you know that Italy ends in Rome?”[8]

Lloyd Baird, who started his missionary service in the Swiss Mission in April 1965 but transferred to Verona, Italy, just three months later, had similar experiences: “My mission in Italy was a wonderful time. . . . We were a bunch of kids having fun. Switzerland was a bear—we would do two months of tracting without getting in a door, whereas in Italy, everyone was willing to talk and their love of life made the experience interesting. It was easy to fall in love with the people and the culture.”[9] James Jacobs, assigned to Italy in summer 1965 after working with Italians in the North German Mission, recalled that he was “happy to have an Italian behind every door—they were curious, open, engaging. . . . I adored the Italians. Many were poor but invited us in, fed us, and listened to us.”[10]

Although the missionaries spent the bulk of their time doing door-to-door tracting, they also tried to be innovative in finding ways to contact people and to raise awareness of their presence. They used a street board (mostra stradale) consisting usually of plywood panels on which scriptural quotations and illustrations were mounted. Setting them up in busy commercial districts, parks, and piazzas, the missionaries would use them to attract attention and initiate conversations. Often, after checking in at the questura of a new city, the elders would visit the offices of the major newspaper to speak with editors and reporters, encouraging them to publish a story about the arrival of the Mormons in Italy. Occasionally the newspapers responded; and in time, a number of stories—most of which were unsolicited by the missionaries—began to appear in Italian print and electronic media.

Another activity that became common was the participation of musical and athletic groups from the church-owned Brigham Young University in free concerts and in local competitions. In July 1965, for example, the BYU track and field team, as part of a European tour, traveled to Milan to compete in a track meet against universities from both Milan and Turin.[11] Events like this were always a welcome diversion for missionaries who lived near enough to attend. While such events offered a break from tracting, they also drew throngs of spectators, including the press, and the missionaries seized the occasion to pass out literature and initiate religious discussions.[12] Another proselytizing method employed by some missionaries involved looking up names of Italian members converted in Germany and Switzerland and now back in Italy, then contacting them to invite them to come to church and to ask if they had family and friends who might listen to their message.[13]

Cities were opened, closed, and occasionally reopened to proselytism as the missionaries “tested the waters” to determine an area’s productivity. One common approach for selecting a city for missionary work was for a pair of elders to stop in a neighborhood, do some spot tracting to get a feel for the receptiveness of the people, and then after prayer and consultation with mission leaders decide whether to continue laboring there. A city might be closed down and missionaries withdrawn because of tepid response, overt opposition, or, as in the case of Milan, effective vigilance on the part of portieri guarding apartment buildings.[14] In some cases, however, the constant contact with the portieri led to new proselytizing methods and conversions. In Rome, for example, whenever a building guard refused to let the missionaries enter an apartment building, they began placing signed letters in the tenants’ mailboxes to introduce themselves and their message. The earliest converts in Rome after its opening in 1967 were the Maffi family, who responded to one such letter and a portiere, Italo Consoli, whom the missionaries had befriended.[15]

Once a decision was made to open a city to missionary work, the elders adopted a strategy of meeting local power brokers to facilitate entry into the community’s social and religious space. Missionaries sought to meet the mayor, the local Catholic priest, and (in northern Italy) Communist leaders. Sometimes these efforts led to unexpected encounters. In one southern city, upon inquiring who could help find an apartment, the missionaries were told to go to the piazza to meet “the employment counselor.” There they found a man “like someone out of the Godfather movie sitting in the park, drinking wine, people consulting him. We explained our religion. He listened for a while, then he said, ‘OK—you’ll be all right.’” A short time later someone appeared and informed the elders that “we knew you were coming and Giuseppe said we should help out.” The missionaries found out later that their benefactor was one of the Mafia chieftains in town.[16]

Opposition to Mormon Proselytism

Just as in the nineteenth-century mission, the activities of the missionaries initially went relatively unnoticed, and they encountered little resistance to their efforts to find and convert religious seekers. But as more missionaries arrived in the following months and the number of Italians attracted to their message increased, the opposition to proselytizing stiffened. The opposition originated primarily from two sources: local police and parish priests. Although the Italian constitution of 1948 guaranteed the right of all religious groups to propagate their faith publicly, traditional attitudes and loyalties in post-war Italy were still deep seated. The transition from religious monopoly to religious pluralism was slow, although legal structures and societal perspectives would evolve in the direction of religious diversity over the rest of the twentieth century. It was not surprising that implementation of laws and citizens’ actual behavior in streets, workplaces, and schools lagged behind.

Officials at the local level, responding to complaints from citizens offended or threatened by the proselytizing of new religious groups, frequently took steps to discourage missionary activities. It was rare for Mormon missionaries to be arrested, and if so, they were quickly released because their activities were legally protected. For their part, the missionaries, ever-ready to find an audience for their message, viewed these encounters with local police officials as an opportunity to make contacts by means other than tracting. In May 1966, for example, police in Padua brought two missionaries into the station in response to complaints about their work. While they were questioned, the elders established a friendship with one of the officers who later joined the church.[17]

Leavitt Christensen, a native of Kanosh, Utah, was working as a civilian personnel officer at the Camp Darby military base near Pisa when he was appointed president of the Italian District of the Swiss Mission in 1964. He reported an incident illustrating the dichotomy that occasionally surfaced between national law and local practice where religious freedom was concerned:

The police [in Varese Ligure] came and told the Elders that they could not hold meetings without special permission from the government and that if they met together, more than two of them, it was a meeting and that they would be arrested if they did so. . . . The missionaries were having meetings in the back room of a tavern. The police told them that it being a public place that such meetings were prohibited. They were also prohibited from holding meetings outside as it was against the law. Any tracts they distributed required payment of 20 lire tax per copy. That is a little over 3 cents per copy.

Christensen commented that similar problems existed throughout Italy, but he was well aware of the distinction between the stance of the federal government and behavior at the local level: “The local officials are the problems; they don’t follow the party line from Rome which is to tolerate other faiths.”[18] Both early converts and missionaries also emphasized that opposition stemmed from deeply rooted religious attitudes at the local and personal level, not from government policies in Rome or directives from the Vatican.

Typically, during the first few weeks after their arrival in a new city, the missionaries had little difficulty finding people to teach. But as local priests began to hear reports from parishioners that Mormon missionaries were circulating in the area trying to win converts, openness to the elders’ message and teaching opportunities began to wane. Missionaries reported that, in some instances, their tracting in a neighborhood prompted local religious leaders to visit their parishioners and dissuade them from responding to the Mormons’ recruitment efforts.[19]

“It was interesting and predictable, when those weekly reports would come in,” Russon observed in his oral history. “We would read the same glowing reports the first week, and then the second week a little bit of fallout would show up. And then over a period of six or eight weeks we would detect some discouragement on the part of the missionaries as they would find these pressures building up and the people finding too much pressure to withstand in some cases.” He noted that, while a few investigators requested baptism—“the cream would always rise to the top”—proselytizing became increasingly difficult for the missionaries after the early euphoria wore off. “Those first initial weeks were beautiful. [The missionaries] thought they were in a paradise, because they’d come from Germany and Switzerland, where the going had been hard, and here were all these doors opening for them. It was a bonanza for a while. But then the realism began to settle in as the pressures would build up as described.”[20] Because of the reaction that conversion often evoked from family, friends, and neighbors, early converts in some cases had to pull their children out of school and move away because other students and their parents made life so miserable for them. A young attorney who converted to Mormonism in Verona reported that he lost three jobs in a short time and eventually moved to another city.[21]

Opposition also came from evangelical Protestant groups who were trying to make headway in Italy and viewed the arrival of the Mormons with alarm. Well-founded rumors of Mormon plans to begin missionary work in Italy had begun to circulate before February 1965, and one Italian Protestant group held a conference near Rome to receive instruction from an American member of their church on how to counteract the Mormons. Four church members who attended the Protestant meeting reported that the Protestant missionary propagated false and outrageous allegations (e.g., that Mormons held sexual orgies in their temples), role-played Mormon proselytizing tactics, and gave suggestions on how to thwart them.[22]

Both John Russon and Leavitt Christensen viewed Catholic and Protestant opposition as temporary obstacles that would diminish over time. Russon reported that an attorney in Modena wrote to him requesting that missionaries be sent to that area. The two men met and had a long conversation while traveling together to Lake Garda near Verona. Based on their candid exchange of views, Russon concluded that the attorney “manifest[ed] the spirit of reform that was going on in the minds of the people” and that many Italians were “anxious” to see “what [the LDS Church] and perhaps other religions could do to help break this hold of the Catholic Church, because it dominates virtually every aspect of their lives, just as we let the [LDS] Church be so much a part of our lives. It governs them financially, . . . politically for the most part, and religiously. And so if they go counter to the church, they can really feel the pressures the church brings to bear.”[23]

Russon’s observation about the parallel influences exerted by the Catholic and LDS Churches respectively in their areas of dominance had its ironies, but it also gave him confidence that religious diversity would develop for a variety of reasons, not just changing one religion for another. Similarly, Christensen described how some Catholic priests exerted social and economic influence to protect their interests but likewise predicted that, in time, less defensiveness would develop. In some areas, “the local priests give some sort of absolution to the employers if they will hire only those who are recommended by the priest; therefore no one gets work unless the priest says so. If the employer doesn’t cooperate, then he doesn’t get the blessings of the Church and he suffers. They are good enough businessmen to see that that doesn’t happen. It is going to be hard going until enough people are converted to establish a precedent and break this stranglehold on the economy.”[24]

Challenges Faced by Early Converts

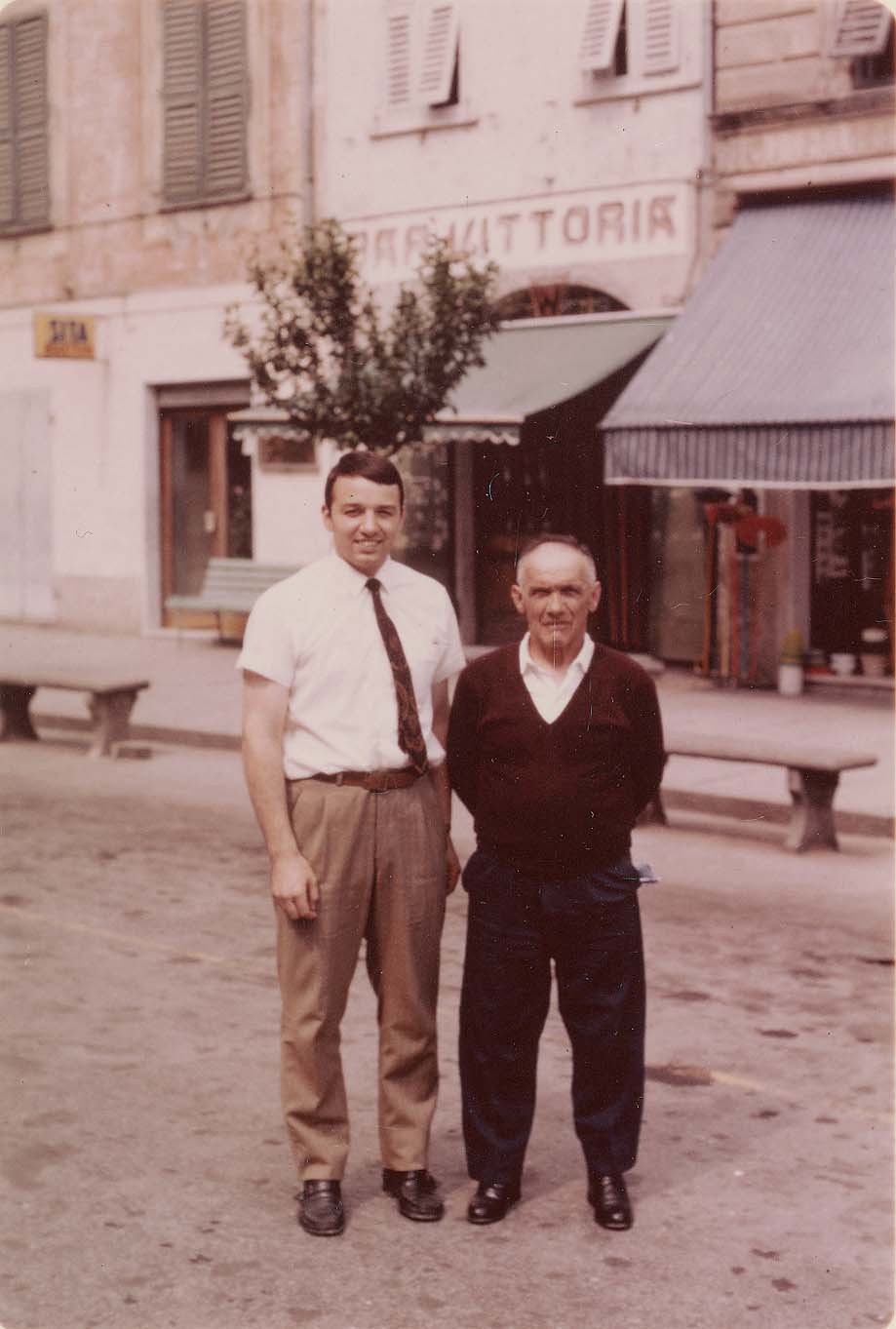

Emanuele Giannini (right), one of the early Italian converts to Mormonism, who was baptized in 1965. He was the only member of the churchin his home town Of varese Varese Ligure. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Emanuele Giannini (right), one of the early Italian converts to Mormonism, who was baptized in 1965. He was the only member of the churchin his home town Of varese Varese Ligure. Courtesy of Church History Library.

The story of Pietro Emanuele Giannini, one of the first Italians baptized after the arrival of the missionaries, illustrates the challenges and isolation that Italian converts often faced during this period as they turned away from their traditional religion toward a new religious identity and way of life. In late 1964, Leavitt Christensen received a letter from Giovanni Ottoboni, a church member of Italian origin living in Argentina, who said that he wanted the missionaries to visit his mother, two sisters, and an uncle who were still living in Italy. President Russon agreed to send two of the first missionaries in Italy to Varese Ligure, a small town about fifty kilometers northwest of La Spezia, to help teach Ottoboni’s relatives. Some of them expressed a desire to be baptized, and on 26 June 1965, Christensen and his wife, Rula, together with the two missionaries, drove to the village to conduct the baptismal interviews:

When we got there we found that the local priests had scared most of the family off. They had told them that anyone who joined the new sect would be denied burial in the town and would be [cut off] from all social activity. The aged mother and daughters then refused baptism but the old uncle was not intimidated and decided to go through with it. In doing so he put his little business and his only means of living in great jeopardy. His name was Pietro Emanuele Giannini. He was found to be worthy of baptism. Brother Ottoboni [who was visiting from Argentina] had prepared a pool in the thick foliage at the outskirts of the town. So all members went there for the baptism. The event had not gone unnoticed in the town. As we looked about us we could see several townspeople peering through the foliage. They showed both curiosity and consternation. We invited them to come closer to watch but they would not. Instead they jeered and flung ugly names at Brother Giannini. They reminded him of the fate that would befall him. He was not moved by any of it. Amid this the baptism was held.[25]

To avoid further confrontations, the group walked a mile uphill to a secluded spot to confirm Giannini a member of the church. But news of the baptism spread quickly through the isolated village, and the missionaries later reported that within thirty minutes spurious rumors were circulating that the Mormons had baptized Giannini naked. Then local religious leaders took action, presumably as a lesson to those who might consider conversion in the future: “Now the priests have apparently forbidden people to come to the old man’s tavern and he is about to close it due to lack of customers. . . . The old man says he doesn’t care anyway because what he was selling is against the word of wisdom and he shouldn’t be in that business.”[26]

Six months later, on 2 January 1967, Christensen and Daniel Walsh, president of the LDS American servicemen’s group in Livorno, traveled to Varese Ligure to visit the new Italian convert:

On the way we worried lest Brother Giannini might have drifted back into his old ways due to his dependence on the little business and also due to loneliness. As we walked into the establishment no one was there except Brother Giannini who sat alone in a far corner. When we approached he looked up and then sprang to his feet and embracing each, planted the usual hello kiss on each cheek of each of us. When we looked at the table we found that he had been reading the Book of Mormon. Brother Walsh asked him if he had read it all the way through. He replied that he had read it many times. Brother Walsh’s question was unnecessary because a quick look at the book showed that all the pages were dog-eared and dirty from handling. Brother Giannini stated that the Book of Mormon was his best and only real friend in town. We returned home happy in the knowledge that he had so much courage, but sad that he had to endure so much in the little village.[27]

Giannini’s baptism illustrates a pattern of conversion that was fairly typical of these early days: An individual living in an area of Italy distant from any of the organized branches in urban areas requests contact with the church, is taught and baptized by missionaries who travel great distances to do so, and then struggles in isolation and ostracism to maintain her or his new faith but who constitutes a tenuous presence for the new church.

Two other conversion stories illustrate this pattern of spiritual conversion and the individual courage and commitment that made it possible for the church to gain a toehold in difficult religious terrain. In November 1965, Rendell N. Mabey, an attorney from Bountiful, Utah, who served as president of the Swiss Mission (1965–68), traveled from Naples to Palermo in Sicily to conduct some business for the church.[28] While there he arranged to meet Antonino Giurintano, whose sister, Giuseppina Oliva, had joined the church in Argentina and then returned to Palermo. Antonino had written several letters to church offices in Buenos Aires asking for missionaries to come to Sicily and teach him, and his petitions had been forwarded to the Swiss Mission office in Zurich. Mabey recounted the beginnings of a Mormon presence in Palermo:

I had brought with me a letter from a Mr. Antonino [Giurintano], to whom I had some six weeks earlier mailed a Book of Mormon. I told Brother Di Francesca[29] that I felt we should visit that man that very night. When we finally located the good man and his family, he was overwhelmed with joy. He handed me a letter which he had just written in which he requested that I come to Palermo at once and baptize him. He was just about to go out the door to mail the letter to me as we arrived. After some three hours of inquiry and discussion, it was concluded that this man was ready for baptism.

He agreed to close down his little factory for the baptism. We met the next morning and, with his wife, son, and his sister who is a member, proceeded to the market place to purchase white clothing suitable for baptism. . . . The six of us adults then climbed into a little cab with the driver and proceeded to the sea just outside the harbor area. Sicily is not unlike a big rock pile, and the sea coast is very unfriendly as far as beaches are concerned. We finally selected a fairly secluded piece of coast [a beach area known as Vergine Maria]. It was cold and the waves were substantial. We changed our clothes among the large rocks, held a prayer circle, and then I held Brother Antonino by the hand and together we entered the water. Brother Di Francesca sat on a rock above us and served as witness.

It was very difficult to stand because of the sharp rocks, high waves and an undertow. Suddenly it was not so cold and the waves subsided enough for me to baptize him. As he arose from the water a big wave hit us and pulled us into deep water. We were just about to undertake to swim when another wave pushed us back towards shore. We were then able to touch bottom and reach shore. There Brother Antonino sat on a rock and was confirmed a member of the church by Brother Di Francesca.[30]

Mabey made the long journey back to Palermo the following May (1966) to baptize Giurintano’s colleague Salvatore Ferrante, who worked in the same factory. At first Ferrante’s father opposed his son’s baptism; Mabey befriended him, and he eventually consented to the baptism and even helped with the translation of the ceremonies from German (spoken by both Mabey and the father who had been a guest worker in Germany) to Italian for the few members in attendance. Mabey then organized the Palermo Branch with Antonino as president and Salvatore, Giuseppina, and Vincenzo rounding out the branch membership.[31] The following week the branch held its first sacrament meeting in the home of Sister Oliva on the first floor of Via Crociferi, 24, and thereafter the branch grew rapidly [a macchia d’olio] as the small group of Palermitan converts proselytized mostly through family networks.[32] Thereafter Mabey continued to correspond with branch members concerning personal and family problems, and he assigned missionaries located in Naples to visit and assist them once each month.[33]

As noted earlier, Leone Michelini converted to Mormonism in 1964 while working in Germany, and upon his return to Turin his wife, Almerina, and their two children were baptized. Their experience (along with that of Giuseppina Oliva and Giovanni Ottoboni) illustrates the crucial role that Italians converted abroad played in helping establish the first small groups and the obstacles they often faced during this early period in finding space and opportunity to meet with other Latter-day Saints.

In October 1964 we returned to Turin and were the only church members there. The missionaries came from Switzerland to visit us once each month. On February 27, 1965, the first missionaries arrived in Italy to work full-time, and eight were assigned to Turin. The first LDS community was established in my house, on the second floor of Via Tunisi, 10. Every Sunday I cleared out the kitchen and borrowed extra chairs from my neighbor [to hold sacrament meeting]. That happened for three months, and the first conference of all the missionaries in Italy with President Russon was also held in our home in April 1965. . . . Later, when my family had to leave Turin, another meeting house was located at Corso Re Umberto, 45. The landlord of the apartment agreed to rent the apartment to the missionaries only if I took responsibility and only with the guarantee that I personally would assume liability for any eventual damages.

A few months later, Almerina moved with her children to their family home in the Polesine area near the Adriatic Sea because her husband could not leave his job in Germany. They spent the next two years without contact with church members, except for occasional visits from the missionaries, until an LDS branch was opened in Padua, sixty-three kilometers away. Despite the distance, the Michelinis’ perseverance helped open the way to the first tenuous growth in that area: “Getting to Padua for Sunday meetings meant waking up at 4:00 A.M. due to scarcity of good connections on the secondary bus and train lines, and then arriving in Padua at 9 A.M. We didn’t get home until 1 A.M. that night. For this reason we decided to move to Padua, and in 1968, in my house at Vicolo Cigolo 51B were performed the first eight baptisms.”[34]

Establishing a Toehold in Italian Terrain

Gradually, with a baptism here and there, and with Italian converts returning home from Germany and Switzerland, the seeds of Mormonism took tenuous root in Italian soil. Missionaries continued to be reassigned from the Italian zones of German-speaking missions; and by the time of Russon’s release as president in July 1965, the number of missionaries serving in Italy stood at forty-four, all of them assigned to locations in northern Italy.

President Mabey continued to take an active role in promoting missionary work in Italy, despite being stretched impossibly in his geographically vast mission. Upon receiving his call as president, he had thought he would be able to sleep at home most nights because Switzerland is a small country. But then he learned the true dimensions of his mission field: the German- and Italian-speaking parts of Switzerland, Italy, Yugoslavia, Greece, North Africa, the Middle East, and all the Iron Curtain countries except East Germany—twenty-one countries in all by the time the Mabeys finished their mission.[35] An important milestone was reached in March 1966 with the organization of the Brescia branch, consisting entirely of Italian members (five in all), with Leopoldo Larcher as president.[36] A second milestone occurred in spring 1966 when Naples was opened to missionary work, marking the first movement of Mormon missionaries south of Florence to central and southern Italy.[37]

Elders generally provided branch leadership because only a handful of Italian men had joined the church in each area, and most, at this early stage, lacked experience in church administration. Church meetings on Sunday were often held in the living room of the missionaries’ apartment or a member’s home until there was a nucleus of members large enough to warrant renting a separate apartment or building as the church’s meeting place in a city.[38]

Almerina Michelini (right) with her daughter, Nives, and her son, Hermes, at their home in Polesine in April 1966. Courtesy of Noel Zaugg.

Almerina Michelini (right) with her daughter, Nives, and her son, Hermes, at their home in Polesine in April 1966. Courtesy of Noel Zaugg.

The missionaries who served during this groundbreaking period in Italy were given a great deal of autonomy and flexibility in their proselytizing methods. Other than sending in a written report, they had only sporadic contact with the mission president—usually at zone conferences a few times each year. This meant that the elders and sisters had minimal oversight from the central office in Zurich to determine proselytizing methods, allocation of time and money, living arrangements, and how to solve problems.

Because of the geographical expanse of his mission field and his own leadership style, Mabey encouraged the missionaries’ autonomy. “I used to tell the missionaries that this was their mission just as much as it was mine and that the Lord would bless them just as much as He would bless me, and He trusted them just as much as He trusted me, and I trusted them too.” During zone conferences Mabey interviewed all the missionaries, sometimes during mammoth sessions that lasted six or eight hours at a time. Often he huddled in his overcoat, since the old buildings or schoolhouses often had inadequate heating or none, despite the bitter cold. Despite this strenuous schedule, Mabey also made a point of visiting the missionary apartments, or “pads,” to check on their living and work conditions.[39]

During this era, the mission organization was fairly spontaneous and a spirit of making do and figuring things out independently was encouraged. It was, according to one elder, the “Wild West” of missionary work: “I didn’t see a mission president for nine months for district and zone conference and interviews. We only had to write a letter to the mission president once/

The majority of missionaries appreciated the reduced structure and greater degree of trust; for the most part, they engaged in proselytizing with dedication. However, Mabey later estimated that perhaps 3–5 percent did not succeed in this system. They saw the less stringent standards and lack of close supervision as an opportunity to avoid the rigors of missionary life. They sometimes ignored or relaxed dress and grooming standards, engaged in unapproved activities such as football and basketball tournaments as diversions, and traveled outside of their assigned areas.[41] A whole genre of mission folklore developed around the topic of illicit missionary trips, referred to as austflugs.[42]

Sister missionaries began serving in Italy in the period just before the Italian Mission was officially reestablished in August 1966. In this photo, taken in the late 1960s, Sister Rula Christensen (left) poses at a gathering in a local park with four other sister missionaries. Courtesy of Church of History Library.

Sister missionaries began serving in Italy in the period just before the Italian Mission was officially reestablished in August 1966. In this photo, taken in the late 1960s, Sister Rula Christensen (left) poses at a gathering in a local park with four other sister missionaries. Courtesy of Church of History Library.

A fascinating development during this incipient stage—one that has been documented in other contexts as well—is the appearance of pseudo-Mormon groups or individuals who adopted the name and selected teachings of the church without authorization.[43] According to the account of Leavitt Christensen (president of the Italian District), in April 1965 he accompanied President Russon and Paul Kelly (a U.S. Air Force officer stationed at Aviano airbase near Pordenone and serving as a counselor in the Italian District presidency) to meet with a “professor” who was making unauthorized use of the church’s name. They traveled by car to Grisolia (near Cosenza), a remote hilltop village at the end of a long drive in the dark along winding mountain roads. The three church leaders found a doorway with the name of the church inscribed in large, bold, red lettering. A man came to the door and invited the guests into his small apartment.

For the next ninety minutes, Russon conducted a detailed interview about the group’s origins and activities. The “professor” had heard about the church from an uncle in Boston and had received letters, pamphlets, manuals, pictures of church presidents, teaching aids, and roll books from church headquarters in Salt Lake City. Though unbaptized himself, he claimed that he had baptized three hundred “converts” to Mormonism in a nearby river and that there were several thousand other followers in surrounding towns. The professor, it appeared, was collecting tithing from the group to support himself and a clandestine political agenda. He expressed interest in having the Mormon missionaries come teach his congregation; but when Russon explained that membership would involve giving up wine, coffee, tobacco, and tea, he retorted: “I don’t think the members would go for that. These things are needed in Italy.” The visitors then noticed a picture of Adolph Hitler on the wall and asked the professor about it. He arose and tore the picture down, stating that he had no affiliation with the Nazis.

At that point, Russon ended the interview and the visitors bade their host goodnight. Russon and his two companions recommended in their report that the LDS Church should exercise more caution when receiving such requests and investigate “similar movements prior to furnishing lesson materials and supplies and prior to giving evidence of support in the form of official letters. It is believed such letters if confiscated by the authorities in Rome might prove embarrassing and possibly detrimental to the Church in its efforts to gain official status in Italy.”[44] It is not clear what became of this group, as mission records contain no further references to its activities.

“Long Live Italy!” The Italian Mission Reopens

June 1966 marked sixteen months of Italian missionary work under the auspices of the Swiss Mission. Russon reported in 1965 that the Italian missionary zone had been baptizing at four times the rate of the rest of the mission.[45] By August 1966 the number of converts stood at forty-two. The missionary force had grown to forty-seven elders and two sisters working in almost twenty cities, with two Italian-member branches operating in Brescia and Palermo.[46] These positive results tipped the balance in favor of creating a new mission in Italy.

In July 1966, the president of the new mission, John Duns Jr., and his wife, Wanda, stood on Ponte Vecchio in Florence watching Rendell and Rachel Mabey disappear into the summer crowds. Florence had been chosen as mission headquarters because of its cultural importance, historical openness to non-Catholic religions, and its geographical location between northern and southern Italy.[47] The Mabeys had traveled with them in northern Italy for several days, meeting members and missionaries, getting acquainted with Florence, and overseeing renovations in the new mission home before Mabey bade them farewell, saying: “All right, President, it’s your mission now. We’re going to go back home [to Zurich].”[48] At that point, Duns later observed, he and his wife “felt we were the loneliest two people in the whole world.”[49] Few programs and materials were available, the mission had no headquarters, and the Duns family had no place to live for the time being except a small pensione.

Missionaries and a few church members gathered at the organization of the newly opened Italian Mission in Florence in August 1966. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Missionaries and a few church members gathered at the organization of the newly opened Italian Mission in Florence in August 1966. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Duns, from Palmdale, California, was a pragmatic man with a reputation for getting things done. For three and a half years in the early 1960s he had lived with his family in Italy, working as an engineer for Lockheed Aircraft and Fiat Corporation and serving as the LDS servicemen’s coordinator. After assessing the situation as the new mission president, he decided to start with the most pressing matters and to work in familiar territory. To begin developing the Italian church, he relied on contacts in business and government that he had established during his first sojourn in Italy. With the help of former colleagues at Fiat, he negotiated reduced prices for the purchase of mission vehicles[50] and developed a new, portable baptismal font.[51]

His circle of professional contacts also proved beneficial in cultivating positive relations with government officials: “Through my work I was able to take President Benson right in to the ministers in Rome. The doors just opened to us.” He also tapped into the existing strength and structure of the American servicemen’s branches: “That’s where we tried to start our missionary programs. . . . That’s where we tried to assign missionaries to work, using servicemen and their families in the program which the Church wanted—to help people they knew. We tried to get them in local areas to find places to meet, places to live, and to start [teaching] the gospel.”[52]

A few days after his arrival, Duns issued an appeal to all the missionaries to renew their commitment to work hard in establishing the church in Italy:

It’s going to require a tremendous amount of work to accomplish our goal: to teach, baptize, and then fellowship these lovable Italian people. The eyes of the whole church are upon us—particularly because of the location of our new mission. I ask and request the full devotion of you all—not just a superficial devotion which works when there is nothing “better” to do, but a deep-rooted devotion which is willing to sacrifice to reach our ultimate goal: baptize and build up the church in Italy.[53]

He selected several elders to serve as his office staff and, assisted by Ferrin Sager, a full-time church employee from the regional office in Frankfurt, rented and began furnishing a space at Via Degli Artisti 8 in the city center to serve as the mission office. An apartment located at Via Lorenzo Il Magnifico 26 became the Duns residence, and the living room would serve as mission headquarters until the mission offices were completed. For a time, they had no office machines and no stationery. Elder James Jacobs, one of Duns’ assistants, recalls sitting at the coffee table in the Duns living room and typing out transfers on his Olympia typewriter that he had brought with him from Germany.[54]

On 2 August, two weeks after Duns’ arrival in Italy, Ezra Taft Benson convened an all-mission conference in Florence. The purpose of Benson’s visit was to reestablish a formal mission of the church in Italy. Plans for reopening the mission were kept relatively quiet to avoid attracting negative attention from other religious groups.[55] During the five-hour meeting held in the new mission office, with forty-seven missionaries present, the Italian Mission was officially organized with Duns as mission president, Leavitt Christensen as first counselor, and Leopoldo Larcher as second counselor.[56] To mark the transition, one enthusiastic missionary wrote: “The Swiss Mission is dead. Long live Italy!”[57]

Training, Supervising, and Motivating Missionaries

With the mission formally established, the flow of missionaries into Italy increased sharply and the need for more effective training, supervision, and organization became more urgent. The first new elder, Yves Jean, arrived from France the day after the conference. Groups of missionaries from the United States arrived in August and were assigned to work in southern Italy and Sicily. By September, missionaries numbered sixty, and by October the force had swelled to ninety-five. The mission was organized into one zone consisting of twelve districts, and many cities were opened to missionary work including Bari, Brindisi, Foggia, Avellino, Messina, Palermo, Agrigento, Catania, Cosenza, and Reggio di Calabria. By December, the number of missionaries had climbed to 116, the mission was divided into a north and south zone, missionaries were working in thirty-five cities, and convert baptisms since the establishment of the mission totaled eighteen.

One of the mission’s early challenges was lack of training and experience among the missionaries, most of whom began their service in the German-speaking missions or had just arrived in the mission field. The Language Training Mission had been established in 1963 in Provo, Utah, but did not include instruction in Italian until January 1969.[58] The mission history noted that “many elders were called to be senior companions when they had been in the mission only a few months and knew only a door approach and a screening discussion. At this time the mission’s biggest problem was finding elders who knew the language and the six discussions.”[59] Duns and his mission staff therefore adopted an innovative measure designed to provide new missionaries with training in Italian language and culture and proselytizing techniques. In September 1966, about six weeks after the new mission was opened, three language schools were established: first in Brescia, then in Florence and Bologna. Many of the new missionaries (“greenies,” or verdini, in mission slang) were assigned to one of these schools for four to six weeks. An experienced elder—normally one with exceptional Italian language skills—was assigned to be the teacher. The missionaries studied from the Jones grammar book[60] and practiced door approaches, prayers, and the missionary lessons in the mornings; then they went out to proselytize in the afternoons and evenings.[61]

Duns utilized zone and district conferences throughout the mission as another means of supervising and motivating the missionary force. Duns, an energetic traveler, launched an ambitious plan to visit each of the twelve districts and to interview every missionary. Accompanied by his wife and two members of the mission office staff, the party drove from Florence to Udine near the Austrian-Yugoslavian border, to Turin near the French border, and down both sides of the peninsula and around the island of Sicily. In the span of several weeks they covered nearly 2,000 miles, maintaining an intense schedule of conferences and interviews. Initially, Duns’ responsibilities and travel included even areas beyond Italy. In January 1967 he succeeded, after numerous attempts, in visiting the Tripoli Branch in Libya. He reported that they held an enjoyable conference with the American members there but that “Tripoli was not very suitable for missionary work, and that the Mission would not be sending missionaries there.”[62] After a meeting with Duns a few months later in May, Benson “decided that the Italian Mission would no longer be responsible for Greece and Northern Africa.”[63]

Although most missionaries responded to this fast-moving schedule by intensifying their own efforts, even the elders who had taken advantage of the “Wild West” autonomy by slackening their proselytizing schedules learned that there was a new marshal in town. While Duns’ leadership style was not authoritarian, he took direct action to communicate more uniform expectations. He cracked down on missionaries in Italy who were “going all over the place and doing a lot of [unauthorized] things” more appropriate for tourists than missionaries.[64] There was, for example, the issue of the austflug that had to be dealt with firmly. Lloyd Baird, a zone leader at that time, observed, “I had the dubious honor to stand up in district conferences and remind the missionaries that Paris and Zurich and the Matterhorn were not within our mission boundaries.” In addition to these public announcements, “I had to talk privately with several missionaries to curtail their visits outside the mission. We saw pictures of elders at some of these sites and had to take some action.”[65]

Mission publications occasionally published a list of mission rules that included admonitions to avoid activities such as “excessive radio listening,” visiting “more than one movie, opera, musical concert, or public entertainment each month, “ walking “any person of the opposite sex home,” “swimming, skiing, and riding scooters,” and calling missionaries “by their first names or nicknames.”[66] Duns called a special meeting of the office staff in February 1968 to curtail problems of profanity and vulgarity among some missionaries and warned, “Severe steps will be taken against elders who violate the mission rule on profanity.” He also announced that “a firmer position” would be adopted in dealing with violations of other mission rules. In September of the same year, Duns summoned the missionaries of the Taranto and Milan districts to the mission office in Florence where he conducted personal interviews to warn them against flirting and inappropriate association with girls.[67]

Duns, like President Mabey before him, felt that the vast majority of missionaries were obedient and focused on missionary work. They were “excellent” in building up a positive image of the church through teaching by example—how they acted and treated people.[68] The problems, in his view, did not result from laziness or succumbing to temptation but from a lack of preparation and proper motives on the part of some missionaries who came on a mission to please a parent or a social group. Rather than taking a punitive approach, therefore, he sought “to settle” the missionaries when they got to Italy: to inspire them with a vision of what it meant to be a missionary, to acquaint them with mission rules, and to teach them how to share the message effectively.[69] Orientation meetings for new missionaries, zone and district conferences, mission newsletters, and personal interviews provided opportunities for such training that combined spiritual admonition and personal management training.

Topics in 1967 district conferences, for example, included religiously oriented discussions on desire and motivation to do the work, obeying mission rules, building personal testimony, effective door approaches, using the European Information Service (EIS—the church’s public relations arm in Europe), and accelerating the pace of moving investigators toward baptism. But there were also presentations on personal goals, leadership and planning, cleanliness (taught by Sister Duns), managing finances, and time management. Duns interviewed each missionary during zone conferences and organized open-house sessions for church members in each location to build missionary-member morale. On the lighter side, sometimes the missionaries played pick-up games of football between conference sessions, followed in the evenings by the popular American “hootenanny”—a group sing-along followed by refreshments.[70]

Duns also organized contests to designate the “best” district and the most productive missionary companionships to foster esprit de corps and greater dedication to mission goals. The mission office proselyting staff (called MOPS) kept comparative statistics on proselytizing activities and hours, teaching time, and number of baptisms for each district and companionship. Missionary districts submitted goals for the number of baptisms per year, and graphs showing each district’s progress toward these goals were published periodically. Prizes were not awarded, but results of the competition were published in the mission newsletter. Duns felt that “a little competitive spirit” was positive and didn’t “hurt a bit”—it was one way to motivate his young missionaries who faced many hardships and struggled often with fear and discouragement.[71]

The mission office at Viale Mazzini 35 in Forence, which by summer 1967 had replaced the original headquarters at Via degli Artisti 8. Courtesy of Noel Zaugg.

The mission office at Viale Mazzini 35 in Forence, which by summer 1967 had replaced the original headquarters at Via degli Artisti 8. Courtesy of Noel Zaugg.

Mission leaders also made a concerted effort to provide greater structure and continuity in missionary work, to standardize policies and procedures, and to decentralize the mission organization to bring leadership closer to the missionaries spread across the peninsula. In March 1968, for example, “Diversion Day”—the day set aside each week for food shopping, letter writing, cleaning the apartment, washing clothes, and sightseeing—was standardized across the mission, instead of allowing each missionary companionship to choose the day.[72] Subsequently, the name was changed to “Preparation Day” (P-Day) to underscore appropriate missionary activities rather than a “diversion” from being a missionary.

The administrative structure of the mission evolved steadily as well. By March 1968, the mission’s twenty-one districts were organized in five zones: (1) Padua, Trieste, Verona, and Brescia, (2) Pisa, Florence, Rome I, Rome II, Naples, and Cagliari in Sardinia, (3) Modena, Milan, Genoa, Turin I, and Turin II, (4) Catania and Palermo in Sardinia, and (5) Taranto, Lecce, Bari, and Brindisi.

Communication with Italian members and non-English-speaking missionaries was often a serious obstacle for mission presidents who usually spoke at best only rudimentary Italian. As the number of converts and missionaries continued to increase, the problem became more acute. By January 1968, when the missionary force reached 149 and spanned eleven countries,[73] Duns was often forced to play “a wonderful game of charades” in trying to communicate with his non-English-speaking missionaries and with the Italian members.[74] More fluent missionaries often acted as interpreters during meetings and interviews, but the resulting noise level frequently generated a problem of its own. During October 1966 the missionaries in Brescia attempted “a type of ‘United Nations’ translation technique” in which a missionary translated “using a microphone-amplifier setup which was connected to various headsets.” Although the distribution of the microphones and headsets was somewhat cumbersome, the translation itself “was very effective and eliminated the usual confusion which had distracted somewhat from previous conferences.”[75]

Experiences with Evil Spirits

Missionaries occasionally reported that they had experiences with evil spirits, which mission leaders took very seriously. Opposition or possession by unseen malevolent spirits, normally associated with the presence of Satan and his desire to thwart God’s work, had long been part of both early Christian and Mormon history.[76] Duns and his replacement, Leavitt Christensen, who served as mission president from March 1969 to March 1972, both received anxious communications from missionaries, both elders and sisters, in various cities—Verona, Rome, Brescia, and Naples—reporting strange illnesses, unexplained noises in their apartments, and chairs moving around in empty church meeting halls. For example, in January 1968, Duns received an urgent telegram from the missionaries in Verona and drove to the city to investigate. The missionaries reported that they “had some rather trying experiences with evil spirits. They have heard mysterious footfalls, shufflings, etc. about the chapel. Drinking glasses have been breaking seemingly on their own.”[77]

Mormonism does not provide an elaborate or even a standard exorcism ritual, but Duns learned that one of the missionaries had “commanded the evil spirits to leave, after which the elders felt considerably more comfortable.”[78] One companionship telephoned Christensen in January 1970 claiming “to have been attacked by an evil spirit.” They reported being awakened in the night with their pillows being pressed over their faces. They handled this alarming event by rising and saying a prayer together, and after that they “were not bothered anymore.”[79] The issue of evil spirits became so serious in one city that Duns considered closing it to missionary work. He visited the missionaries and “was there to see it” but decided against closure because he “didn’t want to take the branch out of that area.” Eventually Duns “found the solution to [this problem]” in the mission and “got it corrected.”[80]

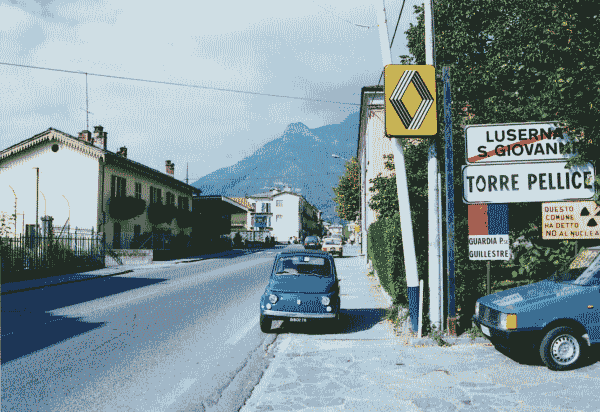

A view of modern Torre Pellice. In the foothills nearby, Elder Ezra Taft Benson held a dedicatory prayer service in November 1966. Courtesy of James Toronto.

A view of modern Torre Pellice. In the foothills nearby, Elder Ezra Taft Benson held a dedicatory prayer service in November 1966. Courtesy of James Toronto.

The missionaries generally interpreted such supernatural events as a sign that “the adversary,” alarmed at the success of their efforts, was directly attacking their work. Duns felt that pride and contention—both tools of Satan according to church doctrine—lay at the root of these problems. The root cause, he believed, was that missionaries were boasting about their successes in proselytizing, visiting Catholic churches and tourist sites, and arguing too much with Catholic priests. He and other mission leaders admonished missionaries to avoid invidious comparisons and acrimonious disputations which only generated strife, drove out the spirit of God, and created an angry atmosphere conducive to the powers of darkness.[81]

The Rededication of Italy, November 1966

On 23 November 1966, four months after the organization of the Italian Mission, Apostle Ezra Taft Benson sent a detailed report to the First Presidency describing the mission’s progress. He concluded: “The missionary work is taking hold and the spirit of the missionaries is most satisfying.” He recommended, based on the mission’s results, “that the quota of missionaries in Italy be gradually built up to about 180” from its current base of about 100.[82]

In the same report, Benson detailed the prayer service that he conducted in Torre Pellice in November 1966 to rededicate Italy for the preaching of the gospel, a solemn and joyous revitalization of the first dedication which Apostle Lorenzo Snow had conducted in Torre Pellice more than a century earlier. The ceremony had originally been scheduled for Florence in conjunction with a mission conference; but devastating floods, some of the heaviest in Italy’s history, had swept through northern Italy just a few days before the conference, leaving Florence mired under three feet of mud without gas, heat, light, or water. Damage to priceless art and architecture treasures amounted to $159 million dollars in Florence alone, and the cost to the nation as a whole was almost three billion dollars.[83]

Benson directed that the conference and ceremony be transferred to Turin since it had largely been spared by the floods. Despite the flood-related transportation stoppages that prevented many from traveling to the dedication, thirty-five missionaries assembled for a conference on Thursday, 10 November, in Turin with Benson, his wife, Flora, John and Wanda Duns, and their twelve-year-old daughter, Teri.[84] Following a number of talks on the progress of the work in Italy, the group drove in several vehicles to Torre Pellice near the Italian-French border about forty kilometers to the southwest. As the group traveled up into Pellice valley, the road became steeper and increasingly narrow and the villages more remote.[85]

Wanda Duns remembered that “President Benson sat with his lap full of papers, scanning the territory and reading from a historical description of the first dedication.” He “was anxious to rededicate in as close a proximity to where President Snow had stood as was possible to determine.”[86] The group had somewhat naively hoped that “Mount Brigham” would be indicated on a map or road sign. Lacking such an indicator, two elders were sent to inquire about its location from some local people, who had no information on the topic. However, the group continued to drive through the valley until Benson indicated a mountain and said, “I think we’ll climb here.” About three-fourths of the way to the top, Benson announced to the group that had struggled up the steep incline in the late afternoon in their Sunday best clothes, “This is it, this is the spot!”[87]

The group sang several hymns; then Benson rededicated “the great nation of Italy” for the preaching of the gospel, noting that it had been 116 years since Lorenzo Snow’s first dedication. He invoked God’s blessings on Italy, its government, and its people: “We know, Heavenly Father, that Thou dost love Thy children and we have in our hearts a love for the Italian people as we assemble here today, and, Holy Father, we pray Thee that Thy blessings may be showered upon them.” He predicted “that this Thy work has a great future in this land of Italy” and that “thousands of Thy children in this land will be brought into the truth and into membership in Thy great church and kingdom that has been restored to the earth.”

Group at the dedicatory prayer service on a hillside near Torre Pellice, Italy, 10 November 1966. Elder Taft Benson is in the middle of the group. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Group at the dedicatory prayer service on a hillside near Torre Pellice, Italy, 10 November 1966. Elder Taft Benson is in the middle of the group. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Benson then acknowledged that the church “can prosper only in an atmosphere of freedom and liberty” and invoked blessings on Italy’s national leaders to the end that peace would be maintained, that the land be shielded from “insidious forces which would destroy the free agency of man,” and that religious freedom would be promoted to allow new faiths in Italy “freedom to present their cause and their beliefs.” Benson also implored the Almighty to temper the natural violence recently experienced in the floods so that “the sunshine of Thy Sweet Spirit” would cause “a resurgence of spirituality, a desire to seek for the truth.” The prayer ended with a vow, spoken on behalf of all the missionaries in Italy, to “rededicate our lives unto Thee and all that we have and are to the upbuilding of Thy Kingdom in the world and the furtherance of truth and righteousness among Thy people.”[88]

At the conclusion of the prayer, Teri Duns recalled, Benson continued for a few moments to look “solemnly into the heavens as tears streamed down his face.” As rain began to fall, the group sang “I Need Thee Every Hour” and “God Be with You Till We Meet Again.”[89]

Benson’s personal account of this event in his report to the First Presidency reads: “[In Torre Pellice] we climbed the mountain side and as near as we could determine, stood in approximately the same area where Elder Lorenzo Snow had dedicated the land [in 1850]. It was a beautiful setting, overlooking the lovely green valley—the moan of the beautiful, clear river reaching us from the distance and two mountain ranges beyond, with snow-capped mountains. Tears were shed as we received the witness that many . . . would now receive the Gospel. Songs of praise rang through the valley as villagers watched, curiously. It was a memorable and inspirational occasion.”[90]

Group at the rededication of Italy on 10 November 1966, near Torre Pellice, Italy. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Group at the rededication of Italy on 10 November 1966, near Torre Pellice, Italy. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Following the dedication, the Duns family returned to Florence to deal with the aftermath of the flooding. The mission home and office buildings were undamaged, but most of the missionaries had to be stationed outside Florence because potable water had to be trucked in from Bologna for the next thirty days. The church supplied humanitarian assistance for flood victims in coordination with the Italian Red Cross “by sending goods and clothing to the people of Florence. Ninety cartons of shoes, clothes, and different supplies were airlifted from Salt Lake to New York by United Airlines, and from New York to Rome by Alitalia Airlines. . . . In all, the Church gave an estimated $22,000 worth of goods to the people of Florence.” In addition, missionaries participated in the cleanup effort, wading through water in the downtown area and shoveling out the deep mud that had accumulated in the lower levels of stores and residences.[91]

Opening Cities and Establishing Branches: The “Shotgun Method”

When he organized the mission in August 1966, Benson instructed Duns to “just go and build your strength in membership.” Duns interpreted this counsel to mean that he should look for cities where the missionaries could begin baptizing right away, organize small branches, and build up Italian leadership as quickly as possible. Because Duns was well acquainted with Italy and its regions from his previous years of residence and travel there, he adopted a strategy of dispersing missionaries across the whole country, rather than targeting only a few key cities. Benson described this approach of “scattering” missionaries throughout the peninsula as “the shotgun method.”[92]

The strategy involved sending one or more pairs of missionaries into a large city on a trial basis “to see what it was like, see whether we had any rhyme or reason, or then if we had problems.” In general, he assigned companionships to cities of 100,000 residents or more, with the intent of expanding outward to smaller cities. This approach allowed the church to baptize members sufficiently close to one another so that they could communicate relatively easily and travel to conferences. Many of the early converts lived on the outskirts of large cities and did not own cars, so the mission made a conscious effort “to get centrally located” so that members and investigators could use public transportation to come to meetings.[93]

Another important criterion was whether Italian or American church members already resided in the target city. The church members’ kinship/

Duns believed that the missionaries should not draw undue attention to themselves in opening new cities to avoid creating more problems for the church. His concern was no doubt related to the somewhat ambiguous legal status of new religious movements in Italy at the time, opposition from local Catholic officials, and anti-Americanism in areas of Communist influence. When some of the missionaries suggested putting the name of the church on the side of the mission cars for publicity, Duns refused, explaining that “we should try just to be one of the people, just try to mingle with the people” as much as possible. He also directed that, whenever possible, LDS meetings be held “at times that didn’t conflict with Catholic masses on Sundays.”[95]

After Benson rededicated Italy for proselytizing, Duns authorized missionaries to dedicate newly opened cities for the preaching of the gospel.[96] For example, the mission history records that a ceremony took place in Rome on 8 July 1967: “Elders of the Rome District gathered on a wooded hill in one of the sections of this great city, for the purpose of dedicating the city for the preaching of the Gospel.” The district leader, John Abner, led the group of ten missionaries in a religious service, “presenting unto the Lord the ancient city of Rome for His work in this dispensation. Elder Paul Toscano offered the dedicatory prayer.”[97]

Time and experience brought about some adjustments to the shotgun strategy. As small branches began to form, missionaries gradually consolidated their efforts, focusing on fewer but more fruitful cities. As it became clear in the early going that growth would be more rapid in the south than in the north, more missionary resources shifted toward the southern regions. Duns, reflecting later on the “shotgun strategy,” wondered if he should have concentrated his missionary force in either the north or the south, then gradually spread to outlying areas “instead of just going all over Italy.”[98] But while baptisms remained sparse for the first year or so, his decision was vindicated by an increasing baptismal rate in subsequent years, and statistics for the year 1970 indicated that five of the top six missionary districts in total baptisms were in southern Italy.[99] Duns noted in an interview that by 1975, just six years after his release, “the church is growing in the cities we opened” and three missions had been created in the zones he had established throughout Italy.[100]

“Teaching the Gospel from All Angles”

The central task that confronts missionaries on a day-to-day basis is how to introduce their message to as many people as possible in ways that effectively address their most pressing issues, questions, and needs. As the number of missionaries in Italy increased, mission leaders sought more innovative and, they hoped, more efficient means of winning converts. In Duns’ estimation, the fundamental goal of establishing the church in Italy required a two-pronged strategy: first at the macro level, to initiate long-term efforts to change the image of the church, and second at the micro level, to improve methods of contacting and teaching individuals and families.

Perceptions of Mormonism in Italy, the missionaries soon learned, were stereotypical and negative, shaped largely by the American cinema and popular Italian literature which generally portrayed Mormons as a nineteenth-century clandestine religion that practiced polygamy on the Western frontier.[101] To combat this caricature, Duns believed it was necessary to dispel the image of Mormons as a small “American cult out of Utah,” instead communicating the changing reality of a mainstream religious community of growing influence worldwide. The “general overall plan,” Duns explained, was to “stir up interest” by showing Italians the true nature of the church—“that we’re not there to disrupt their way of life. We’re there to help them and to build their way of life.” The missionaries wanted Italians to perceive Latter-day Saints as normal, law-abiding citizens who aspire to make positive contributions to the societies in which they live and who love music, art, education, and sports. They sought to portray the church as a multi-faceted, progressive religious organization that “had a variety of programs for everybody to participate in.”[102]

To this end, the missionaries undertook a number of activities that went beyond the traditional methods of door-to-door tracting, street boards, and member referrals. As a first step, Duns again tapped into his extensive professional network in Italy, handing out church books and Mormon Tabernacle Choir records to friends to arouse interest and arranging speaking engagements with former colleagues in the Italian government, military, and automotive industry. During one such meeting with former colleagues in the Fiat conference room in Turin, he was favorably received and he responded to many sincere questions about his present duties as a Mormon mission president. Duns concluded from these experiences, perhaps somewhat optimistically, that the Italians “were beginning to look for something. They wanted something for their families that they didn’t have.”[103]

Duns’ personal initiative was eventually transformed into a mission-wide proselytizing effort called the “VIP Program.” This program consisted of inviting influential people to meet in the conference room of a five-star hotel for an “Encounter with the Mormons” [Incontro con i Mormoni] to learn about the church and meet the Duns family. Italian members of the church worked closely with the missionaries in planning and making the presentations. Often such VIPs saw the newly translated church film, Man’s Search for Happiness, originally made for the New York’s World Fair in 1964, and discussion ensued. At one Incontro, seventy prominent lawyers, educators, and religious leaders viewed the film; and Duns then addressed the group, encouraging them “to think more seriously about the meaning of existence” and challenging them “to listen to the message of the missionaries.” Reporters who covered the event wrote favorable articles in local newspapers.[104]

Another finding method used from the earliest days of missionary work in Italy centered on musical presentations, which were used to improve public perceptions about the church and to create an opening for religious dialogue. One of the earliest examples of this approach was the appearance on national TV of 107 missionaries who had gathered for a mission conference in Florence on 23–25 December 1966. They spent Christmas Eve singing carols in the city center “with the intent . . . to spread in song the Christmas spirit through a city which had recently been ravaged by floods.” The group assembled at the main cathedral, the Duomo, and began singing Christmas carols and Mormon songs in English and Italian. Their singing attracted the attention of a BBC television crew in Florence to cover the pope’s visit later that evening. The BBC director requested that the group sing at Piazza Santa Croce to provide background music for the Pope’s appearance at 9:00 P.M. It turned out that the pope was an hour late. The missionaries seized this opportunity and sang for the large throngs who paid rapt attention when the TV crew trained their lights on the Mormon choir and filmed the impromptu concert, including a rendition of “Silent Night” in Italian.

Afterwards, several missionaries were interviewed by TV reporters in Italian about their activities in Italy. According to two elders, “It was a huge success. We succeeded in getting the Italians near us to sing along.” The next day, images of the missionaries singing were broadcast over national television as were some of the interview segments. This gave “an unexpected boost” to spreading the gospel in Italy. With a touch of missionary hyperbole, reflecting the enthusiasm engendered by a sudden burst of public exposure after laboring in virtual anonymity, President Duns commented: “Florence will never be the same after tonight.”[105]

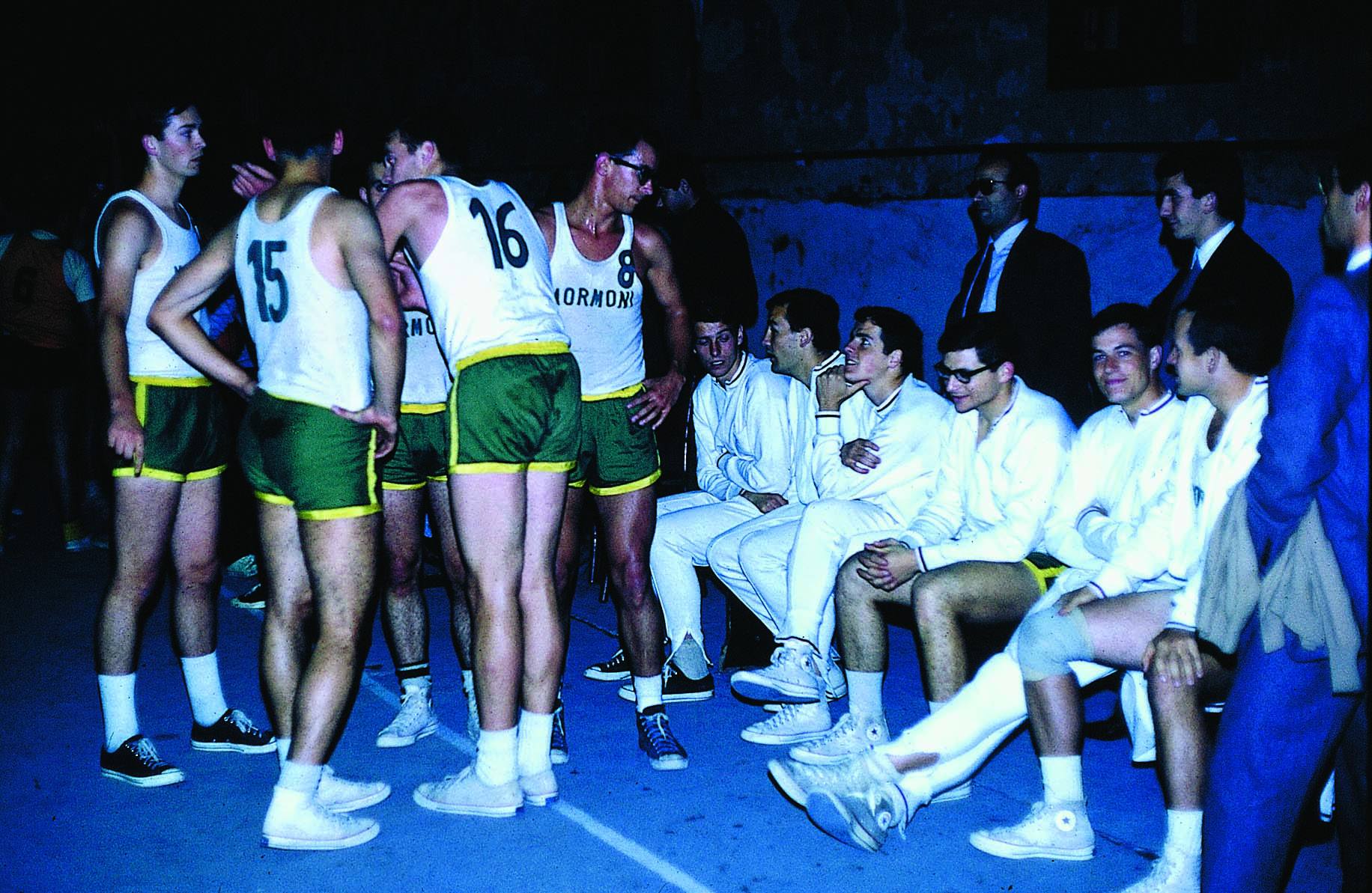

Because of their positive experience with the impromptu choir concert on Christmas Eve 1966, the missionaries sensed the potential of musical and sporting events in garnering media attention and, hence, attracting wider exposure for their message. In August 1967 seven elders were transferred to mission headquarters in Florence to join a newly formed mission basketball team, carrying the evangelically pragmatic name I Mormoni SUG (The Mormons LDS). The missionaries played against teams from universities and sporting clubs throughout Italy, normally in large cities already opened to missionary work. Team members presented each opposing team with copies of the Book of Mormon and gave a brief explanation of the church. Other missionaries working in the area performed during half-time shows (such as judo exhibitions), dressed up as female cheerleaders to urge the team on to victory, passed out church literature, and invited spectators to church services.[106]

In February 1968, after six months of competition, the mission basketball team officially disbanded, and the sports experiment ended. The team’s record was twenty wins and twenty-four losses; however, the winning percentage was secondary to the overall objective of spreading “the name and spirit of Mormonism in Italy through the new and fast-growing sport of basketball.” A total of 176 copies of the Book of Mormon had been distributed, 90 newspaper articles had been published, and 13,000 spectators had attended the games.[107]

Another attempt to raise awareness and dispel myths about the church was a “bold” public relations program, “Tri Summer 6ixty 8ight,” that mission leaders hoped would “have a great effect on the future of the Italian Mission.” It consisted of three parts: (1) the formation of a traveling talent group; (2) arranging for a visit by the BYU Folk Dancers to perform in a talent program in Venice and Rome; and (3) facilitating the broadcast of the church’s long-running radio program featuring the Mormon Tabernacle Choir and a brief interdenominational message, The Spoken Word, over Italy’s national radio network.[108]