Outreach to Catholics and Dwindling Mormon Presence, 1855-67

James A. Toronto, Eric R Dursteler, and Michael W. Homer, "Outreach to Catholics and Dwindling Mormon Presence, 1855-67," in Mormons in the Piazza: History of the Latter-Day Saints in Italy, James A. Toronto, Eric R. Dursteler, and Michael W. Homer (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2017), 105-136.

When converts emigrated from the valleys to Utah in three groups during 1854–1855, it changed the dynamics of the mission. The membership was drastically drained, and the many advantages of having members who were familiar with the valleys were significantly diminished. This development convinced the missionaries to once again attempt to spread the mission to Turin where they again encountered stiff opposition from both Catholics and Protestants, who took advantage of the Mormons’ presence to debate government policies toward religious groups. But this new initiative did not produce any convert baptisms, and the missionaries again retreated to the Waldensian valleys until the close of the mission.

An Unexpected Visit

After the Malan family departed with the second group of Italian converts in March 1855 and their home was no longer available as a residence and headquarters, Samuel Francis was obliged to rent a room from a Dr. Gianetti at Torre Pellice after returning to the valleys. Subsequent efforts to locate another suitable headquarters proved fruitless. “Since the departure of the emigrants,” Francis wrote to Keaton, “we have not found a house like that of brother Malan.”[1] Over the next few months Francis engaged in his normal activities of writing correspondence, visiting church members, and preaching the gospel. But in June 1855, Samuel Francis lent a copy of Stenhouse’s pamphlet Mormons and Their Enemies to a Waldensian pastor in St. Barthelemy. After a heated discussion, the pastor ordered Francis to leave his home. [2]

Francis began to cast his eye toward the Catholic regions of the Chisone valley and the city of Turin. No doubt Francics’s positive impression of Turin disposed him in that direction, but perhaps the low number of baptisms that year among the Waldensians, their indigent circumstances, and the opposition of Waldensian pastors, also contributed to his budding desire to reopen missionary work among the Catholics. In early June he sent Ruban to Perosa “to see if anything could be done among the Catholics,” and the report must have been favorable because on 2 July Francis left San Germano with Elders Ruban, Rochan, and Rivoir to “visit the Catholics” in Perosa. But rainy weather and lack of success in arousing interest dampened the missionaries’ enthusiasm. The missionaries made further visits in July, but they did little more than leave some tracts and hold a few conversations with Catholic priests.

By the fall of 1855, Francis, at the behest of Daniel Tyler, had begun to study the Italian language in preparation for more sustained preaching among the Catholics. On 18 September, while writing his Italian exercises in his rented room at Torre Pellice, he was startled to see his faithful friend John Chislett, who informed him that Franklin D. Richards, president of the European Mission and a member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, was in Pinerolo along with other church representatives Daniel Tyler, William H. Kimball, and John L. Smith. Chislett told him that they had forwarded a letter requesting a meeting in Turin but that the communication never arrived. Thereafter, Francis met them in Pinerolo and accompanied them to Torre Pellice, where he rented another room to accommodate his guests and prepared a supper of mushrooms, bread, and butter.[3] This visit brought great satisfaction to Francis, who had suffered loneliness and discouragement during the past year as the only English missionary in Italy: “Oh, how indescribably happy I felt to see again so many of the Elders of Israel. . . . The hearty shake of the hand, the “God bless you” of the brethren strengthened and refreshed me and I felt in truth in the company of angels.”[4]

For the next week, the group toured the Italian conference. Tyler was impressed by the steadfastness of two sisters, recent converts to the church, who visited the church leaders in Torre Pellice: “Their parents had turned them out of doors without giving them a change of clothing because they would not deny the faith. They were laboring at a low price to earn more clothes. We gave them lessons in English which seemed to please them very much. They did not seem downcast.”[5] They spent another full day in pilgrimage to Mount Brigham and the Rock of Prophecy, where “a spirit of prophecy and revelation rested upon us and we all prophecied [sic] good things for Italy.”[6] During this meeting, Richards prophesied on the work’s success in Italy, Germany, and Switzerland, and he directed Francis to undertake “a mission to the city of Turin.”[7]

The group also visited the homes of the church members in the mountains. In San Germano they found the Chatelain family “almost dying from the effects of eating fungis [mushrooms]. We laid hands on them and they began to recover.” On Sunday, 23 September, a conference of all the church members was held in Prarostino, during which church authorities were sustained and each missionary addressed the congregation, with Chislett and Francis translating. The group traveled to Turin the next day, and before leaving for Geneva, Richards set Francis apart for his mission to Turin. Though Francis “felt very lonely” after their departure, he also “felt abundantly the blessing they had sealed upon my head and was strengthened and built up from the many good instructions they had made known to me.”[8]

Francis spent the next several months on administrative duties, updating the “History of the Italian Mission,” and also selecting and preparing a third group of converts for emigration to Utah. After determining the final list of thirty-one names—“the most destitute and most worthy” members[9]—and receiving 2,769 francs from mission headquarters for financing, Francis accompanied the emigrants to Lyon and from there to Liverpool, England on 28 November. Francis spent the next two months in his native land, assisting the Italian emigrants, and enjoying the company of his family and the English Saints.

In mid-February 1856, Francis returned to Geneva to work as clerk for the new mission president, John L. Smith.[10] In April, he was pleasantly surprised to hear Smith announce that Francis would return to Piedmont that week: “I was glad to hear this news, as I had been a little unsettled about the work there. I was longing to see the saints, and to commence the mission Pres. F. D. Richards gave me to Turin.”[11] He received about eighty francs in donations from the saints and from mission funds to support his journey, and set out for Italy on 11 April. He reached Turin three days later after a miserable journey, “suffering dreadfully” from the worst toothache of his life and nursing a headache caused by the rough night crossing over the mountain pass on sledges. Worse yet, his travel trunk (portmanteau) with valuable belongings including nearly two years of his journal went missing.[12]

While Francis was in Switzerland, additional strife and disunity crept into the church in Italy. After his arrival in Turin he spent the first few weeks visiting the homes of the Saints, telling them the news gleaned during his trip, and hearing their concerns about the conduct of the branch president, Elder Ruban, whom they accused of exhibiting “imprudence” in his relations with church members. Francis discussed these matters with Ruban and sought to reconcile the aggrieved parties.

Missionizing Again in Turin

Esther Weisbrodt Francis. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Esther Weisbrodt Francis. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Francis continued to study Italian and prepared to proselytize in Turin. He visited the city on at least two occasions to shop for new clothing and to find an apartment with the help of Jean Rostan, a convert from Prarostino. Rostan offered to provide lodging and help with the missionary work in Turin, and Francis was sanguine about the prospects for success with the involvement of a native member: “I feel that the Lord has answered our prayers . . . and that He will make me the instrument of establishing a Turin Branch of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints before the close of 1856.”[13]

Toward the end of June, Francis made a new acquaintance that would change his life: he began exchanging English lessons for Italian lessons with Esther Weisbrodt,[14] a teacher in one of the Protestant schools in Prarostino. Soon, language lessons turned to religious discussions, and although “she raised many objections, reasoned very strongly from her weak points, and manifested much prejudice at first,” after a few days she seemed more amenable to the principles of Mormonism. Weisbrodt eventually accepted baptism, and their friendship would blossom into romance and lead to the extraordinary event of a Mormon missionary marrying one of his converts while still serving his mission.

On Sunday, 29 June, a special conference was held to transact business and prepare the members for Francis’s departure to Turin. “We had an excellent time and I labored incessantly through the day to teach the saints principles and bless and strengthen them in the work.” The next two days in Prarostino were spent making final arrangements. He learned, to his great disappointment, that Brother Rostan had reneged on his promise and would not be accompanying him during his mission to Turin, thus depriving him of the benefits that a local missionary would bring to the new enterprise: “Thus I was obliged to go alone, without a single recommendation, and with a very imperfect knowledge of the [Italian] language; in fact, the little I had learned, I was obliged to unlearn and commence de noveau.”[15] After bidding farewell to the church members and having some long conversations with Weisbrodt, he left for Turin on 2 July 1856 and found “a nice room on Viale Belvedere, Borgo-nuovo, 3rd story for 19 frs. per month.” [16] After writing a letter to the Saints, Francis “took a walk through the city humbly and earnestly asking the Almighty to direct me how and where to commence my labors.”[17]

The mission to Turin would last nearly six months—by far the most sustained effort of the early Mormon missionaries to proselytize in Catholic territory. But it would prove to be a time of adversity and turmoil, both for the church in Italy and for Francis personally, and the expected harvest of converts never materialized. Francis went about his new task with characteristic energy and temerity; but felt greatly constrained by the existing legal and social environment and by his inability to communicate effectively in Italian. Since public preaching was prohibited, he employed several methods to garner attention to his cause. He printed publicity flyers to announce his location and willingness to hold religious discussions in private.

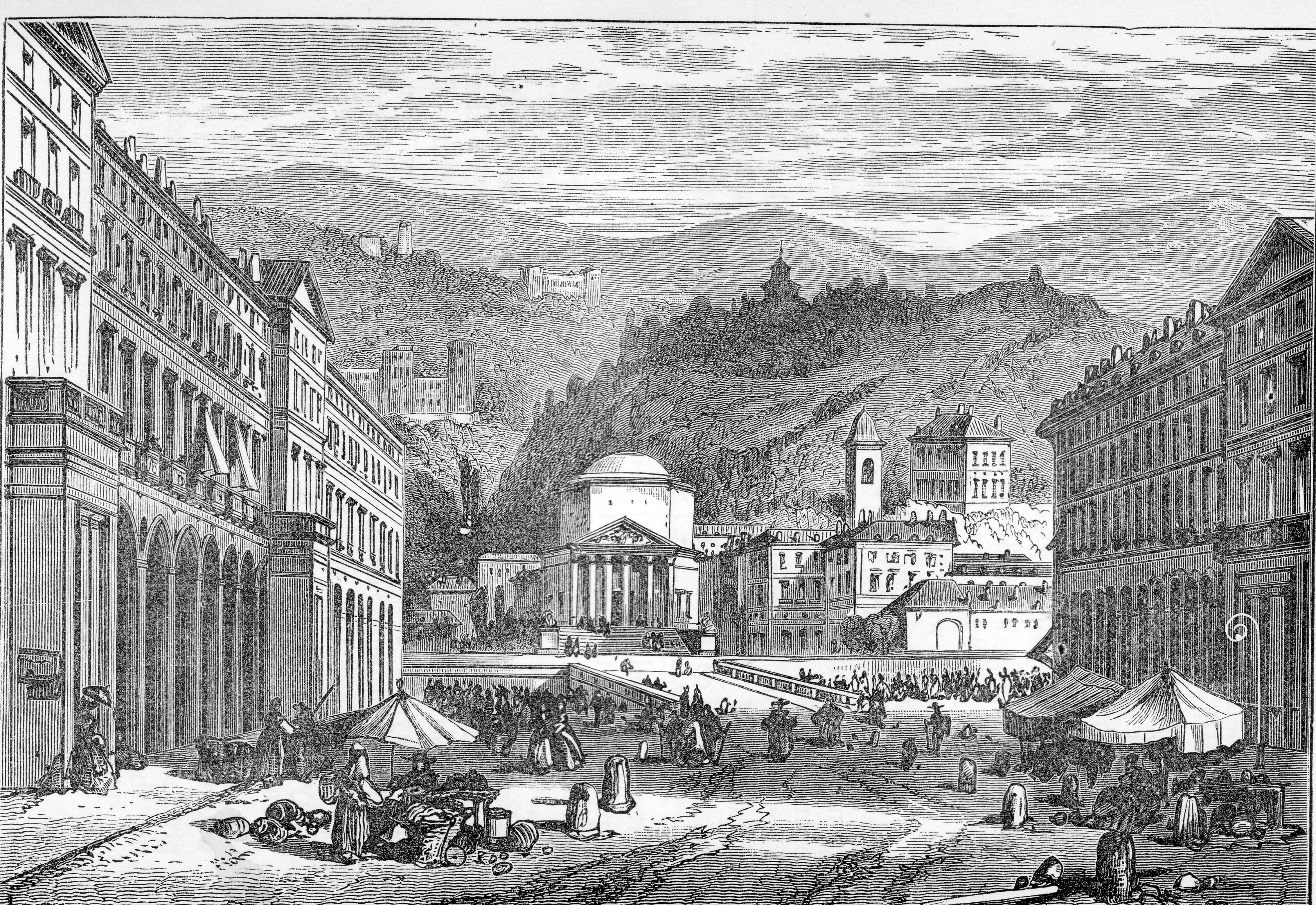

Piazza Vittorio Veneto, a center of commercial and social life in the heart of Turin. Reprinted from J.A. Wylie, History of the Waldenses, 4th ed. (London: Cassell & Company, 1889), 53.

Piazza Vittorio Veneto, a center of commercial and social life in the heart of Turin. Reprinted from J.A. Wylie, History of the Waldenses, 4th ed. (London: Cassell & Company, 1889), 53.

Another more audacious approach was his habit of attending religious services in other churches and passing out tracts to the “honest”—those he felt, based on spiritual impressions, would respond positively to his message. “In the morning I wrote my address on a few tracts,” he recorded on his first Sunday in Turin, “and asked the Lord to bless them and me in distributing them among the people. I visited the Protestant church to have a look at the people and to see if [I] could find any honest among them. I felt I could and made up my mind to give them some tracts, but among the crowd in going out I lost them. In the afternoon I visited the same church and saw the lady that accompanied me across the Alps. I determined to speak to her and give her a tract, but she was lost among the crowd. I returned home a little sorryful that I had not been able to succeed.”[18]

Another tactic was contacting acquaintances of people he knew in the valleys. Weisbrodt, for instance, had given him the names of several of her friends in Turin, and soon after arriving he addressed three tracts to these individuals, inserting a personal note inviting them “to call upon me, or give me an opportunity to call upon them.” One of these contacts, a Mr. Varisco, did respond to the invitation, and though uninterested in religion (he was “liberal minded”), he arranged meetings for Francis with other acquaintances (including a Mr. Girardi and a Mr. Bouchet) and notables in Turin society.[19]

Francis clearly had ambivalent feelings about life in Turin. On the one hand, after almost two years in the rural mountain valleys of Piedmont, he was enthralled by the beauty of the urban landscape and the sophistication of the culture that now surrounded him. His occasional encounters with the social elite were always noted obsequiously by the young missionary raised among the English working classes. He mentioned seeing Victor Emanuel II, the king of Sardinia, and having conversations about religion with Gustavo Modena, “one of the Great Italian actors”; Mr. Gazzola, “formerly a cardinal in the Catholic church”; and Mr. Bert, “the Protestant minister at Turin.”[20]

For relaxation, he enjoyed attending the theater and opera in Teatro Garbino, strolling in Il Giardino del Re and other public parks, and walking through the bustling streets and picturesque piazzas of the Piedmontese capital. Nevertheless, Francis recorded that the urban lifestyle and the Italian outlook represented impediments to his success. After a Sunday evening walk, he wrote, “All was life and gaiety, bands were playing, the people dancing, the Cafes were crammed, also the Theatres, il Giardino Publico and other promenades were thronged. Everyone was apparently happy.” He lamented that “none among all that people were thinking of Eternity, their only object was to make the present sweet. Oh! how my soul wept in looking upon that people. I was unhappy, yes, I could have sat down and cried for them.” He wished that he had “the liberty to preach in the streets” so that he “could declare the Gospel to them in their own language.” Feeling frustrated and “bound on every side,” he returned to his room “sick of the scenes” he had witnessed.[21]

In spite of these challenges, missionary work in Turin was not devoid of opportunities to promote Mormonism. His approach of distributing tracts at church doors and along public walks and gardens aroused much interest: “I formed several acquaintances, and received many invitations, and for a few weeks I was occupied every day discussing our principles.” On numerous instances Francis held long conversations with “strangers” during meetings in private homes. Only one of these contacts, a young man named Perinetto, came back for more instruction and expressed interest in baptism, but he eventually drifted away from regular contact. For Francis the explanation was clear: “All with whom I was brought in contact were too secular in their views, or so firmly bound to their former traditions, that I found it impossible to induce them to obey the truth.”[22]

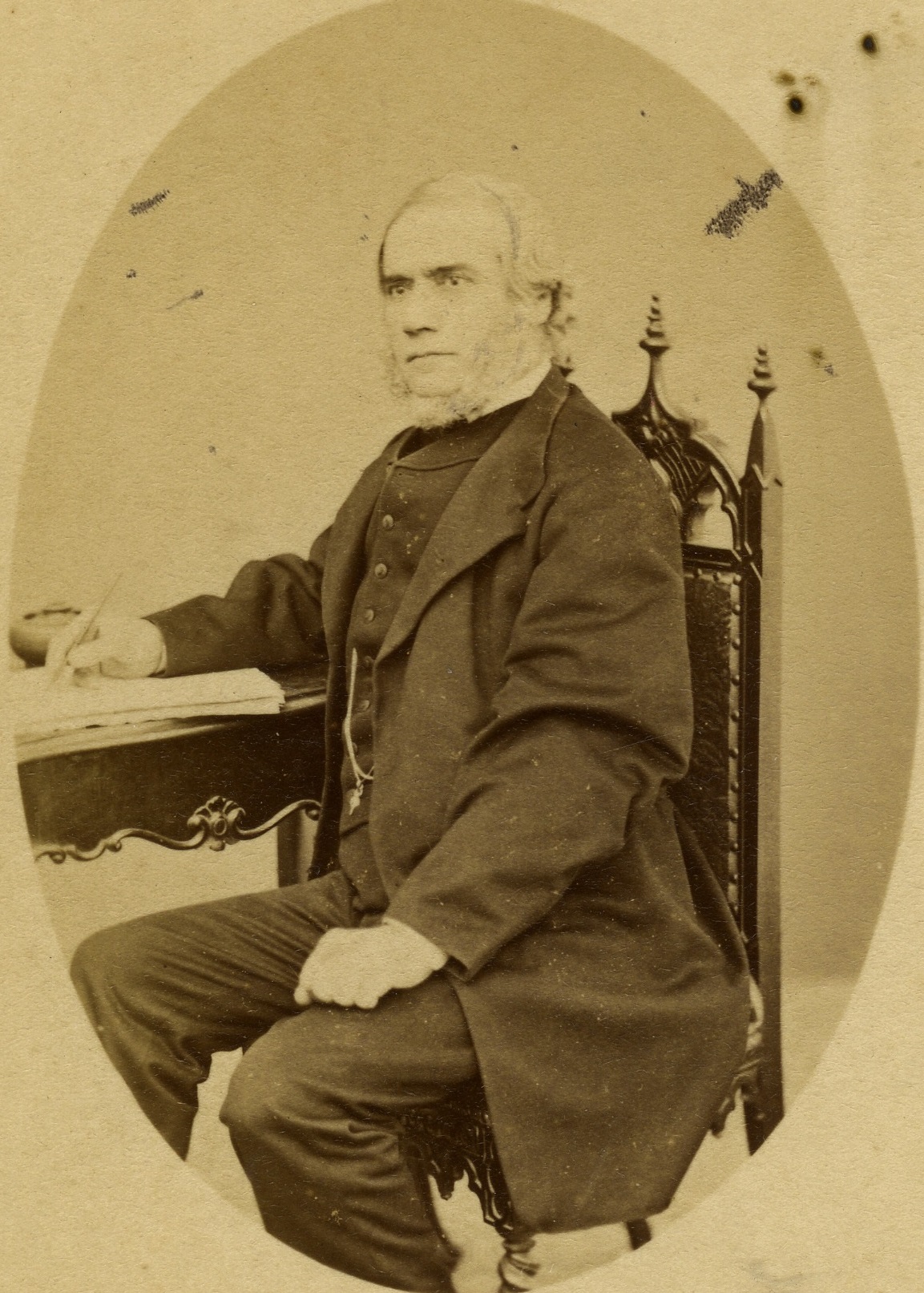

These less-than-subtle efforts to make converts and to distribute literature criticizing the religious status quo aroused the ire of the Protestant clergy. On several occasions Francis attended the meetings of the Italian Evangelical Church and sent pamphlets and letters to its pastor, Luigi Desanctis—a former Catholic priest and theologian.[23] After Francis passed out copies of the tract La Restaurazione dell’Evangelico to Desanctis’s congregation as they were leaving his church, the pastor “came to my room to know why I had distributed my blasphemous tracts among his members, said I had insulted his members by giving them such books.” Francis responded that “he was a false teacher and leading the people astray, and that God had sent me there to preach the gospel and open the people’s eyes to his false position and deceptions.” Desanctis rebutted these charges and denounced Joseph Smith and Mormon teachings about polygamy. When the pastor proposed a public debate in Italian, Francis replied that he did not know Italian well enough to do this, but if he agreed to speak French, “I would meet him any time or in any place.” Before Desanctis left, Francis bore his testimony to him and “gave him le bon jour.”[24]

The Mormon presence in Turin also attracted the attention of the city’s leading newspaper, Il Risorgimento, which announced on 28 July that the heads of the Protestant and Mormon churches were planning to hold a meeting to discuss reconciling the subject of polygamy with the laws of Piedmont. This announcement elicited an angry retort from the Waldensian newspaper La Buona Novella disclaiming any connection to the Mormons because of their teachings on polygamy. Francis prepared an article in response to both newspapers, but his friends persuaded him not to publish it “as it might cause a little excitement, and result in the authorities requesting me to leave.”[25]

Complications with Weisbrodts and Church Members

While the missionary work in Turin was seeking a foothold, the church back in the valleys was experiencing a bona fide crisis, and as a result, Francis would suffer through a dark period of personal turmoil. Throughout his sojourn in Turin, Francis continued to visit the church branches in the valleys on a regular basis. He happily noted that his Italian tutor, Miss Esther Weisbrodt, began to attend church services during one of his visits, but a few days later he learned that the headmaster of her school had invited her to a private meeting to discuss her connection with the Mormons.

Luigi Desanctis (1808-69) was a Catholic Priest and Waldensian pastor before he became a minister of the Societa Evangelica. Courtesy of Archivio Fotografico del Centro Culturale Valdese (Torre Pellice), Editrice Claudiana, and Gabriella Ballesio, archivist.

Luigi Desanctis (1808-69) was a Catholic Priest and Waldensian pastor before he became a minister of the Societa Evangelica. Courtesy of Archivio Fotografico del Centro Culturale Valdese (Torre Pellice), Editrice Claudiana, and Gabriella Ballesio, archivist.

Before the meeting, she sought Francis’ advice: “I told her not to be afraid, that if she was convinced of the truth of our principles to tell him so, and that she was to put her confidence in God, who would protect her, that Mr. Canton could but take the school away from her. I told her not to deny, by any means, the convictions the Holy Spirit had made upon her mind.” Apparently she heeded his advice and followed her conscience because shortly thereafter the headmaster, Canton, and the local magistrate convened a council and summoned Weisbrodt to attend. According to Francis, “Canton insulted her in every possible manner. She was ejected from the school and they tried to rob her of all her money they owed her.” On 26 July 1856, a few days after being dismissed from her teaching position, Weisbrodt was baptized by Elder Ruban and confirmed the next day by Francis.

Weisbrodt’s conversion, though undoubtedly a joyous occasion for the members and missionaries in a year when baptisms were scarce, ushered in a series of contentious events that fostered division and sorrow in the church. The Waldensians, who placed a high value on education, were, according to Francis, “enraged against the saints because we had baptized one of the school governesses.” A new round of anti-Mormon invective ensued, incited by Canton’s fiery speeches denouncing the church and its teachings.

To make matters worse, Charles Weisbrodt, who was Esthers father and a diplomat at the German embassy in Turin, decided to step in and save his daughter from her folly.[26] He went to the valleys and accompanied her back to Turin, but a few days later she returned to Prarostino. Weisbrodt then came to Francis’ apartment in Turin, demanding to know his daughter’s whereabouts and attempting to intimidate him by claiming he had been sent by the German ambassador. This proved to be untrue, as Francis learned when the two men visited the ambassador, who engaged them in a cordial discussion of Mormonism and promised to read several items Francis offered him. Weisbrodt’s father was not dissuaded from his impulse to rescue his daughter from the clutches of the Mormons. Having failed in his ruse to intimidate his daughter and Francis, he appealed to legal authority, and on 12 September Francis was summoned to appear before a judicial board in Turin. “I went and found that Sister W’s father had been [there] and complained against me saying that I had stolen his daughter, etc. I told the authorities the truth of the matter and they believed me and said it was all right.”[27]

While trying to deal simultaneously with mounting clerical hostility in Turin and the valleys and with the Weisbrodt family’s efforts to reclaim their daughter, Francis found himself facing a major crisis in the church itself. He learned during his trips to the valleys that there had been “some unpleasantness” between Elder Ruban and some of the members. He admonished Ruban about the importance of not staying in one place, but moving about the valleys to visit all the members. The problem intensified when both missionaries became enamored of the new convert, Weisbrodt, and a rivalry for her affection ensued.

Francis, as the presiding church authority, chastised Ruban for having made promises to marry Weisbrodt and another young woman in the valley, as well as being negligent in his missionary duties and unreliable in keeping confidences. “I loved Sister W. and had confessed my little weakness of my life to her, and Ruban had drew these things from her.” Ruban, in turn, began to spread rumors among the members that Francis was no longer worthy of his leadership position because he was “a whoremonger, tippler, and tyrant.”[28] The controversy was addressed by convening a council of church leaders on Sunday, 31 August, to hear the arguments, an event that turned out to be, in Francis’ view, raucous and depressing: “At 9 o’clock the council commenced and I laid several charges against Ruban. He kept barking all the time that I could not speak to the brethren. He called me a liar and everything else, but a man of God. Betrayed me and Sister W. by telling things that had been told him in private and that had no bearing upon the case and that had transpired in other countries. We could settle nothing for there was too much confusion.” Francis reported that after the meeting Ruban “called some of the brethren together secretly and belied my character awfully. Told the brethren I spent my time drinking in public houses with depraved men, yes with drunkards and whoremongers, and said that I was nothing better than such society. In the afternoon the council reassembled, but owing to the things that Elder R. had said against me, I could not persuade the council to act, neither for me or against me.”

The next day Francis wrote that he “was very unhappy and much troubled in spirit. I do not know that I was ever so much grieved in my life before. I wrestled with the Almighty to strengthen me and give me his Holy Spirit.” He also wrote a long letter to John Smith in Geneva detailing the divisive issues and events that had beset the church during this difficult season. A week later a letter arrived from Smith recalling Ruban from his mission in Italy. While passing through Turin on his way back to Geneva, Ruban met several times with Francis in a spirit of reconciliation. Francis recorded that “Elder R. partially confessed his wrongs and I forgave him and wrote a letter to Pres. Smith to that effect and asked him to give Elder R. another field of labor if possible.”[29] This rapprochement between the two missionaries in mid-September 1856, together with a few later meetings with church members in the valleys, brought resolution to these issues and a conclusion to this difficult chapter. But the fallout from this traumatic period lingered, exerting a dampening effect on church growth and coloring the perceptions of church leaders about the viability of the missionary enterprise in Italy.

Francis persevered in Turin for three more months, dividing his time between the capital city and the valleys. He remained upbeat and purposeful during his remaining time in Italy, conversing about the gospel with callers to his apartment, passing out pamphlets with Jacob Rivoir (a traveling elder from San Germano) along the streets of Turin, administering to the sick, preaching to small groups during the evening veglia in stables around the valleys, and reinforcing the members’ knowledge of Latter-day Saint doctrine. He notes, for example, preaching to the Saints about the premortal existence of spirits one Sunday morning and in the afternoon reading to them from the French translation of Apostle Parley P. Pratt’s tract on polygamy, Mariage et moeurs à Utah (Marriage and Morals in Utah), which was evidence of the ongoing debate over polygamy.[30] By instruction from President Smith, he commenced teaching about the law of tithing and translated material from the Millennial Star into Italian and French to assist him. In mid-November he was constrained to leave Turin and return to live with the members in the valleys for a while when his funds ran out, but the members raised money to buy him new shoes and to help him return to his missionary labors in the capital city.

Francis’s short mission in Turin illustrates the precarious nature of doing missionary work “without purse, and scrip.”[31] Rooted in scriptural precedent but necessitated by a lack of financial resources in the church, this practice placed missionaries at the mercy of local members and rendered them vulnerable to the vicissitudes of economic and political events. As a result, their meals were sporadic and modest, their sleeping arrangements uncertain and spartan, and their clothing inadequate for the rigors of missionary life. From time to time, money was received in a small container called a paquet d’argent, sent from the mission home or from members in other countries to support the work in Italy and to contribute to the emigration effort.

Normally, however, the early missionaries depended on the church members for their food, clothing, and accommodations. Records contain many examples showing the largesse of the members in sharing meals; in donating money to buy trousers, shoes, or coats or taking time to make them; and in providing sleeping accommodations. Members who sold off family assets to obtain funds for emigration to Utah were often expected to share the proceeds with the missionaries. Inevitably, the economic dependency of the “no purse nor scrip” system—especially at a time of severe poverty—led to some misunderstandings and conflicts. One family claimed that the missionaries had encouraged them to sell their property to prepare for emigration but then took the revenue and used it to pay missionary expenses.

Back to the Valleys and Beyond

On 11 December 1856, “finding nothing new” and his prospects “becoming darker instead of brighter,” and having received a letter from Smith “to return to the valleys to pass the winter there,” Francis packed his belongings and left Turin for San Germano.[32] Girardi, his Italian tutor and friend, accompanied him to the station to say farewell. He was “the only companion I had in Turin. He was a very quiet and good man, but did not care anything about religion, at the time he respected mine.” Francis offered this assessment of his experience among the Catholics of the Sardinian capital during the past six months: “It was with great reluctancy that I left him [Girardi] and my mission at Turin. I had done a great deal of tract distributing and private preaching and discussion but none had obeyed my voice. A great deal of my time I spent studying the Italian language, but as yet I was not prepared to speak publicly and it was with much difficulty that I could keep up a conversation. I thought that perhaps next spring I should be better provided in every respect and with the hope of returning at a future time I was comforted.”[33]

Francis would remain in Italy just two more months. It was the height of the winter season when proselytizing was difficult because of the deep mountain snows, so he was absorbed primarily in attending to church business and resolving issues with the members who were suffering greatly from poverty and severe cold. Shortly after returning to San Germano, a new proselytizing approach was attempted. Francis organized a tract society in collaboration with members to circulate Mormon teachings. Some members were hoping still to emigrate to Utah, some were excommunicated for apostasy or negligence, and others needed counseling about family and financial matters. Francis’s journal entry on the eve of the new year, 1857, captures his mood: “Adieu 1856. I don’t want to see thee over again.”[34]

On 6 February 1857, Francis was invited to return to Geneva to work in the mission office and “to give me an opportunity to refresh my spirits and by a change of living to recruit my health and thoughts.” After considering the offer, he reluctantly decided to accept, and the announcement of his decision to the members was traumatic: “It was with mingled feelings of joy and sorrow I decided to go. For the saints were so poor and ignorant, and needed so much visiting and comforting, I felt it to leave them. As I announced to them the contents of the letter they became pale and cried. We had rejoiced and wept together, we had been hungry and cold together, we had been persecuted and blessed together, and so many things had conspired to unite us together and we felt as one. They looked upon me as their savior and comforter and I looked upon them as the treasures of the Almighty confided to my keeping. We passed the rest of the day very sorrowful. They were afraid that if I parted I should not return.”[35]

The next week, Francis attempted to put church affairs in order and prepared members for the departure of their president. In keeping with instruction given by Franklin Richards during his visit in September 1855, and reflecting the broader forces of the so-called Mormon Reformation, Francis directed that all the members come to San Germano to be rebaptized and reconfirmed.

The early Latter-day Saint practice of rebaptism and reconfirmation is well attested in the documentary records of the Italian Mission. Numerous examples are cited of members being rebaptized as a means of renewal following a spiritual crisis or of healing for a physical ailment. Francis and Ruban had previously been rebaptized on 31 October 1855 “in accordance with the counsel of Pres. F. D. Richards,” who had just toured the mission. In September 1856, after the internal strife that threatened to destroy church unity, many church members were rebaptized. Weisbrodt, after moving to Geneva and marrying Francis, was rebaptized and reconfirmed for her health. With the advent of the Mormon Reformation in 1855–57, rebaptism became a requirement for all church members as a sign of their renewed commitment to God and the church.[36] In January 1857, just a month before Francis left Italy, Orson Pratt received instruction from Brigham Young to institute the Reformation in the European missions.[37] With the news of his imminent departure, Francis undoubtedly felt some urgency to comply with this mandate when he directed, in the dead of winter, that the church members remaining in the valleys be rebaptized and reconfirmed.

When the new round of rebaptisms took place, the weather was bitterly cold and the snow deep as the Saints made their way from the mountainsides to the lower river valley, and a melancholy spirit permeated the gathering: “It was very cold, I never felt the weather so cold before in my life. I had pieces of ice on my hair. On my arrival the saints could not speak to me, their hearts were so full of sorrow about my departure.” In the icy waters of the Chisone, Francis rebaptized six members from San Germano and Esther Weisbrodt from San Bartolomeo, and then Jacob Rivoir rebaptized Francis. The next day, the members from Buole Coste were rebaptized, and then all were reconfirmed. Francis observed: “The Holy Spirit was poured out upon us. I prophesied many good things for the saints and blessed them in the name of Jesus Christ. The saints went away with their hearts full of joy and the Holy Spirit.”[38]

On 12 February 1857, after settling an unpleasant property dispute and bidding the members farewell, Francis left San Germano for Pinerolo on the first leg of his journey to Geneva. As he was leaving San Germano, he experienced the sting of religious animosity one last time. A former church member, Jean Rostan, who had been excommunicated one month earlier, struck him with the handle of an axe and threatened to take his life. When the assailant, a butcher by trade, began looking for a carving knife, Francis “walked quietly away thanking him and wishing him good day.” He was accompanied him to Turin by his fiancée, Esther Weisbrodt, and sfter presenting her with his picture, attending a show in Teatro Garbino, and visiting his old friend Girardi, he departed for Switzerland.

Upon his arrival in Geneva, Francis wrote a lengthy report on the state of the church in Italy and prospects for future growth. He acknowledged that “our numbers are very small there at present; some of the strongest have been obliged to go to France in search of employment, and some have returned to the Waldensian Church, in their poverty, for the loaves of bread, while others have desire to be cut off because they have not been immigrated. The few that are left, with one or two exceptions, are those that had been in the church a long time, and whom we can term the faithful.” Nevertheless, he observed, the members

were zealous in the work of God, attend their meetings regularly, and are very obedient to the Councils and instructions of the servants of God. They are very hospitable according to their means. While among them, I have always the offer of the warmest room and the best bed, the easiest stool, and the nearest place to fire, indeed, they do everything they can to make me comfortable. Our prospects there are not very bright for the moment, nevertheless we do not despair, for we have seen the sun hide his face before, and sometimes for a long time.[39]

“Retrenchment Is the Order of the Day”

The members’ concern that Francis would not come back to the valleys turned out to be well founded. Continuing difficulties among the few remaining church members in Italy and political and financial pressures afflicting the church in general prevented his return. He assumed his new clerical duties in the mission home and presided at the same time over both the Geneva and the Italian conferences, regulating the affairs of the church in Piedmont by correspondence. A new missionary, Eugene Herail, was set apart for a mission to Turin and left Geneva on 28 February. He proved unreliable, however, and left the mission for France after being discharged in June. In April, Francis received word from President Smith that Orson Pratt, president of the European Mission in Liverpool, had decided that Francis should remain in Geneva instead of returning to Piedmont.

At Francis’s invitation, Esther Weisbrodt arrived in Geneva on 9 June, and three weeks later, on 1 July 1857, they were married by the English Consul. One month later, 2 August, they were married again by President Smith “according to the order of the Church,” meaning that they were sealed for eternity. The newlyweds remained in Switzerland working together in the mission home until 17 April 1858, when they were transferred to the headquarters of the European Mission in Liverpool. Before leaving Geneva, Francis wrote a letter to Jacob Rivoir in San Germano appointing him president of the Italian conference. Francis never returned to Italy, serving in England until his release in 1860 after a decade of missionary service and migrating in 1861 to Morgan, Utah.[40]

Francis’s transfer was part of the larger retrenchment movement in the LDS Church that arose starting in 1857 in response to escalating tensions between the church and the US government. Mormon leaders launched a decade-long effort to weather the crisis by promoting communal solidarity, self-sufficiency, and a renewed religious commitment.[41] The retrenchment led to a significant reduction in the missionary force, from 144 in 1856, to 96 the next year, to just 18 in 1859. Throughout the following decade of crisis the average number of missionaries serving each year was only forty-four.[42]

The developments in Utah were reported by the press in Turin. In September 1857, the Waldensian newspaper La Buona Novella reported that the United States government had sent troops to Utah territory.[43] The Catholic newspaper in Turin, L’Armonia, also reported that trouble was brewing between the federal government and the Mormons in Utah. In January 1858, it noted, “The Mormons are finally in open rebellion: Brigham Young, their Prophet, has proclaimed war against the United States. The result of this contest is not in doubt; the power of the Mormons cannot be compared with that of the Government; . . . the institutions of Mormonism are directly opposite to the spirit and practice of the Government, . . . but Brigham Young wants to resist the Government with the help of the Indians.”[44]

Later that month L’Armonia reported that “Mr. Buchanan is resolved to finish off the Mormons, increasing the number of soldiers sent to overcome them. . . . [He has] decided to finish with the Mormons, purging the American Republic of these pests.”[45] In March the newspaper gleefully reported that the women of Mormonism had revolted upon the approach of the soldiers: “The Mormon women, as the Federal troops approached Utah, had begun to manifest a spirit which is not hostile to the enemy soldiers. One could say that the Amazons in whom the Patriarch Brigham Young placed such faith for the defense of the sacred soul, have the intention of changing husbands and passing to the camp of General Johnston with their arms and baggage.”[46] After the conflict had ended, L’Armonia observed, “The [Mormons] are now under the authority of the Government, and it is no longer necessary to obligate them to renounce their moral principles and strange religious beliefs.”[47]

L’Armonia’s occasional references to the United States government’s challenges to the Mormon hierarchy during the Utah War may have prompted Italian writers to criticize the Mormons. These included Giacomo Margotti’s (the editor of L’Armonia) discussion of Mormons in London (1858), Francesco Cavalleri’s reference to Mormon plural marriage (1864), and Luigi Rendu’s mention of the Mormon practice of baptism for the dead (1865).[48] Others published even more detailed accounts and criticisms. In 1860 La Civiltà Cattolica, a journal with strong ties to the Vatican, published a speech delivered by Cardinal Karl August von Reisach, a Bavarian prelate, to the Accademia di Religione Cattolica entitled “Mormonism in Connection with Modern Protestantism” in which he both contrasted Mormonism to the Protestants and compared them with Catholics.[49] During the same decade Giuseppe Fovel wrote an article entitled “Mormonism and the Woman” (1864) in which he relied heavily on French sources including Jules Remy’s travel account of his visit to Utah.[50] These accounts may have encouraged later Italian travelers to visit Utah and to publish their own memoirs.[51]

At least three publications were distributed during this same period that specifically referenced and ridiculed the LDS Italian mission. In 1862 Giacomo Perrone, a prominent Catholic theologian, included a forty-five page appendiz about Mormonism in a book comparing Catholicism and Protestantism.[52] Three years later William J. Conybeare’s article concerning Mormonism, originally published in Endinburgh, appeared in Italian in Milan,[53] and in 1869Luigi Stefanoni, who had been a colleague of Giuseppe Mazzini and was fiercely anticlerical, wrote Storia Critica della Superstizione, in which he attacked the claims of virtually all religions including Waldensians, Mormons and even spiritualism.[54] Stefanoni devoted a chapter of this book to the Mormons and mentioned that they “pretended to have a church [in Italy], of which none of us had ever heard about.” He also observed that the “Italian mission included four individuals, an American, an Englishman and a Scott, directed by Lorenzo Snow, apostle of the Church,” that they elected to go the Kingdom of Sardinia and “assembled on top of a hill in the Waldensian valleys, which they named Mount Brigham” and from there organized the church in Italy. But he surmised that “the number of faithful in this church has never surpassed the number of its four founders even as we Italians are forced to draw on these particulars from outside sources.”[55]

During this difficult period of conflict and retrenchment, Brigham Young called Jean Daniel Malan Sr. and Jabez Woodard in April 1857 to return to Europe as missionaries in the Swiss and Italian Mission. Both missionaries and members considered Malan as the spiritual leader of the Waldensian converts and was the first in a series of converts to return to his homeland as a missionary. Malan also received a special assignment to gather information on Italian sericulture to assist in Mormon efforts to establish the industry as part of the economic base in Utah. Woodard was probably called to return to lead the mission because he was in charge when most of the Waldensians had joined the church.

Anticipating their arrival, John L. Smith and Samuel Francis wrote to Orson Pratt that “the Italian conference is in a good condition, the Saints are few in number, and very poor in regards the things of the world, but the majority of them are united and faithful, as well as obedient to the servants of God.” Francis noted that “I have been absent from them seven months, but as far as I have had opportunities to learn through letters from Elder Rivoir, the prospects are good for an increase in that conference; and I have no doubt but that the arrival of Elder Malan from Zion will do the Saints much good; as well as cause many to inquire after the truth, he being one of their own countrymen.”[56]

In June 1857, Francis instructed Rivoir to take the presidency of the San Germano Branch from Pierre Rochon (who was a resident of Inverso Pinasca). In August, Woodard arrived in mission headquarters in Geneva and replaced John Smith as mission president. While J. D. Malan Sr. and Frederick Roulet were assigned to the Waldensian valleys.[57] After his arrival, Malan began to experience problems with Rivoir, and Francis attempted to resolve the conflict and provide instruction through a steady exchange of letters. Nevertheless, Malan achieved virtually no success, and the following January, he and Roulet were released as missionaries. Jacob Rivoir remained in the valleys, where he continued to report to the mission.[58]

Mormonism in the Italian Press

The developments in Utah were reported by the press in Turin. In September 1857, the Waldensian newspaper La Buona Novella reported that the United States government had sent troops to Utah territory. A Catholic newspaper in Turin, L'Armonia, also reported that trouble was brewing between the federal government and the Mormons in Utah. In January 1858, it noted, "the Mormons are finally in open rebellion: Brigham Young, their Prophet, has proclaimed war against the United States. The result of this contest is not in doubt; the power of the Mormons cannot be compared with that of the Government; . . . the institutions of Mormonism are directly opposite to the spirit and practice of the Government, . . . but Brigham Young wants to resist the Government with the help of the Indians."

Later that month L'Armonia reported that "Mr. Buchanan is resolved to finish off the Mormons, increasing the number of soldiers sent to overcome them. . . . [He has] decided to finish with the Mormons, purging the American Republic of these pests." In March the newspaper gleefully reported that the women of Mormonism had revolted upon the approach of the soldiers: "The Mormon women, as the Federal troops approahced Utah, had begun to manifest a spirit which is not hostile to the enemy soldiers. One could say that the Amazons in whom the Patriarch Brigham Young placed such faith for the defense of the sacred soul, have the intention of changing husbands and passing to the camp of General Johnston with their arms and baggage." After the conflict had ended, L'Armonia observed, "The [Mormons] are now under the authority of the Government, and it is not longer necessary to obligate them to renounce their moral principles and strange religious beliefs."

L'Armonia's occasional references to the United States government's challenges to the Mormon hierarchy during the Utah War may have prompted Italian writers to criticize the Mormons. These included Giacomo Margotti's (the editor of L'Armonia) discussion of Mormons in London (1858), Francesco Cavalleri's reference to Mormon plural marriage (1864), and Luigi Rendu's mention of the Mormon practice of baptism for the dead (1865).

Others published even more detailed accounts and criticisms. In 1860 La Civilta Cattolica, a journal with strong ties to the Vatican, published a speech delivered by Cardinal Karl August von Reisach, a Bavarian prelate, to the Acacdemia di Religione Cattolica entitled "Mormonism in Connection with Modern Protestantism" in which he both contrasted Mormonism to Protestantism and compared them with Catholicism. During the same decade, Giuseppe Fovel wrote an article entitled "Mormonism and the Women" (1864), in which he relied heavily on French sources included Jules Remy's travel account of his visit to Utah. These accounts may have encouraged later Italian travelers to visit Utah and to publish their own memoirs.

L'Armonia's articles and Reisach's speech also undoubtedly prompted additional high-profile references to Mormonism that specifically mentioned the Italian Mission even though Church membership was negligible. In 1862 Giacomo Perrone, a prominent Catholic theologian, included a forty-five-page appendix about Mormonism in a book comparing Catholicism and Protestanism. Three years later, William J. Conybeare's article concerning Mormonism (originally published in Edinburgh) appeared in Milan, and in 1869 Luigi Stefanoni, a former colleague of Giuseppe Mazzini who was fiercely anticlerical, wrote Storia Critica della Superstizione, in which he attacked the claims of virtually all religions including Waldensians, Mormons and even spiritualism. Stefanoni devoted a chapter of this book to the Mormons and mentioned that they "pretended to have a church [in Italy], of which none of us had ever heard about." He also observed that the "Italian mission included four individuals, an American, an Englishman and a Scot, directed by Lorenzo snow, apostle of the Church," that they elected to go the Kingdom of Sardinia and "assembled on top of a hill in the Waldensian valleys, which they named Mount Brigham" and from there organized the church in Italy. But he surmised that "the number of faithful in this church has never surpassed the number of its four founders even as we Italians are foced to draw on these particulars from outside sources."

The Last Decade

In the decade following the departure of Francis and Malan, the work in Italy entered its denouement. The years 1858–67 marked a period of attrition during which several factors—the ongoing necessity of cutting off disaffected members, the lack of missionary activity and conversions, the continual trickle of Saints emigrating to other areas, and the church’s emphasis on retrenchment—would combine to deplete the already thin ranks of the Italian Latter-day Saint community. In the decade after the third large emigration in November 1855, eight church members managed to leave the valleys for Utah.[59] Jacob Rivoir, who continued as president of the Italian conference (which had dwindled to one branch), reported in 1861 that “the work in Italy has been at a stand-still for a long time.”[60] Fewer than ten converts joined the church during this period, and after Malan’s unceremonious departure in 1858 only one missionary was assigned to serve in the valleys.

Elder Guglielmo Sangiovanni of St. George, Utah, arrived in San Germano in September 1864 and spent eleven months preaching among the Waldensians and seeking to strengthen the few church members that remained.[61] From Sangiovanni’s correspondence to his mother, we learn that another missionary, George B. Spencer, had been assigned to join him in Italy in the spring of 1865, but Spencer contracted smallpox while in Geneva to study French and was unable to continue on to Italy.[62] Sangiovanni spent the first three months after his arrival studying Italian even though “the language generally spoken here is the Patwah and French. . . . The Italian proper is spoken but very little here in these parts which has made it very difficult for me to learn.”

While struggling to learn Italian and French, which he considered more exhausting than doing manual labor, he enjoyed taking long walks in the mountains to mingle with the people and to pass out tracts. “I have been out in the mountains bearing my testimony, not in preaching in public, but by calling at the houses of the people, also go into the fields where they are to work, and tell the news I have for them. They listen to me very attentively and thank me telling me they have their ministers to preach to them.”

Sangiovanni also made an effort to visit former members who had been excommunicated in hopes of reviving their faith in the church, but he found that in some cases they still harbored resentful feelings. One such family in San Bartolomeo had relatives who had emigrated to Utah and who later sent money through a Mormon missionary in Geneva named Moosman to help them emigrate. When Moosman arrived in San Bartolomeo to deliver the money, the family “chased him off a throwing rocks at him every jump. . . . Since that time they have repented, and have a desire to come back into the church.”

Sangiovanni became a familiar figure as he strolled through the fields introducing himself and his message. “I am well known all over these parts,” he wrote, “as they call me le Pasteur des Mormons!!!” Because he was viewed as the “Mormon pastor,” the people assumed he was wealthy and highly educated like all other ministers in the valleys, and they refused to believe him when he insisted that he was “nothing but one of the Peasantry of our country [the United States] and work for a living when I am to home.” The hospitality and politeness of the people impressed Sangiovanni whose letters report no acrimonious encounters but reflect an obvious pleasure in the simple traditions of Waldensian culture, like the veglia.

Despite the generally positive interaction he enjoyed with the common folk, he was exasperated by the “great many curious stories” and rumors about the Mormons that circulated in the valleys: “A woman whom I was talking with the other day on the principles of the Gospel, said she did not wish to offend me but she would like to ask me one question, and that was if we took the people from Europe for the purpose of eating them! For I have been told, said the poor ignorant woman, that they eat the people after they get them to Utah!!!!!” Other church members reported similar experiences.

The European Mission went through numerous organizational changes during the decade from 1858 to 1867, none of which impacted the church’s growth in Italy. In January 1861, the Swiss and Italian Mission was renamed the Swiss, Italian, and German Mission, further evidence of the church’s campaign of retrenchment and consolidation.

On 22 July 1865, Sangiovanni bade farewell to Italy, describing it as the “garden of the world” but expressing hope that he would never again “be under the necessity of going there to preach the Gospel.” After almost a year of solitary and discouraging labor in the Waldensian valleys, during which he had no visits from mission leaders and made no new converts, such an assessment from a young missionary is hardly surprising. Back at mission headquarters in Geneva, freed from the loneliness and isolation he felt in the mountain valleys of Piedmont, Sangiovanni felt almost giddy with relief: “Excuse me if I joke a little,” he wrote to his family, “for I feel as though I was just let out of prison.” He was subsequently assigned to work in Berne using the French language, and although he reported that “Italy is given up for the present”—implying that his return there might be a possibility—he would have the distinction of being the final missionary to serve under the aegis of the first Italian mission.

In 1863, Paul A. Schettler reported that only ten members would remain in Italy after the expected departure of three emigrants to Zion.[63] In June 1863, Chauncey W. West, acting president of the British Mission, toured the various European missions, including Italy, and stopped in Turin to visit with the remnant of church members from the Waldensian valleys.[64] Elder Sangiovanni noted at the end of 1864 that the total number of church members in Italy had dropped to seven. With his transfer to Geneva in July 1865, the mission saw the last of its full-time missionaries, and with the emigration of Jacob Rivoir in April 1866, the church lost its only experienced leader remaining in the valleys. A report in May 1867 indicated that the Italian Branch consisted of one family, the Justets, six persons in all.[65] On 1 January 1868, the Swiss and German Mission was formed, dropping Italian from the title and effectively closing the chapter on the first mission to Italy.[66]

A Small but Extraordinary Haul

Initially, church leaders selected Italy as one of the church’s first foreign-language missions because of its potential for finding Israelite lineage, its pivotal cultural and historical role in Europe, its connection to apostolic Christian history, and its strategic geographic location in the Mediterranean basin. For all these reasons, hopes were high for a bounteous harvest of souls, but missionaries encountered a daunting array of political, economic, and social obstacles that frustrated these expectations and limited the actual number of conversions to fewer than 200, only one-third of whom eventually gathered with the Saints in Utah. These challenges included political tensions in the Kingdom of Sardinia related to the Italian independence movement, or Risorgimento, in full swing as the missionaries arrived; lack of religious liberties for non-Catholic groups, especially in urban areas; intense poverty and a harsh economic and physical environment; strong opposition of the Protestant clergy; and fierce communal loyalty among Waldensians to their ancestral traditions.

The few Waldensians who joined the church were attracted by Mormonism’s emphasis on charismatic spiritual gifts, apostolic priesthood authority, and theological arguments, as well as the prospect of economic and social improvement through emigration to America. Waldensian society was passing through a period of internal social, educational, and religious reform that coincided with the advent of Mormonism and that provided the missionaries greater opportunity for proselytizing than could be found elsewhere in Italy. The Waldensian scholar, Giorgio Tourn, has concluded that the missionaries’ success was not so much “a response to Mormon theology, but a response to the ‘radical’ spiritual needs of the 1800s that the [Waldensian] Church did not adequately address or satisfy. . . . Mormon missionaries and others were able to take advantage of this situation. Also, when people are hungry, they will listen to people who offer bread. Later, in the 1880s, the [Waldensian] Church responded to this problem and resolved the crisis. Had this happened earlier, the missionaries would not have had such success.”[67]

In addition to the most obvious factors that led to the closing of the Italian mission—a minimal number of new converts, attrition through excommunication and emigration, and the church policy of retrenchment—there was a growing sense among some church leaders who held a millenarian view of history that the blood of Israel in Italy, and indeed all of Europe, had been mostly harvested. When Franklin D. Richards became president of the European Mission for the third time in July 1867, “it was believed by many that the British Mission was in its decline. It was thought that nearly all of the seed of Israel had been ‘gathered out,’ and that only a remnant of the Saints remained to be emigrated. . . . The closing of the British Mission, for a season at least, seemed imminent.” As Richards wrote in the Millennial Star, “Our former labors in this mission were performed at times of sowing the Gospel seed, and of abundant reaping of the harvest of souls; but the spirit of the times seems to suggest that today is a period for the gathering of the sheaves into the garner of the Lord. Our earnest desire is to move with the spirit of the present, and to use our utmost influence to urge upon the Saints the necessity of gathering up to the mountain of the Lord’s house.”[68] In other words, the time for “sweeping the nations” for the blood of Israel had concluded and a season of gathering and strengthening Zion had arrived.

With time and greater experience in the challenging political, economic, religious, and linguistic environment in which they worked, the missionaries and church leaders abandoned their expectations of a spectacular harvest of souls and became more philosophical about the relatively small number of converts they actually made. Later documents frequently use metaphors that connote the eventual development of something great from that which initially seems small and unremarkable. Snow wrote to Orson Hyde that he looked forward “to the day when the stability and grandeur of our building will be an ample reward for those months of labour which may not have been attended with anything extraordinary in the eyes of those who judge merely by the external appearance of the moment.” In the same letter, he also recorded in detail a dream that “presented a theme for meditation” related to missionary work in Italy. In the dream he caught a fish while on a fishing excursion but was “surprised and mortified at the smallness of my prize. I thought it very strange that, among such a vast multitude of noble, superior-looking fish, I should have made so small a haul. But all my disappointments vanished when I came to discover that its qualities were of a very extraordinary character.”[69] Other missionaries similarly commented on the small number of converts but the exceptional quality of their faith, commitment, and hospitality.[70]

In sum, Snow’s metaphor of a small fish but of exceptional quality seems apropos. Although only about seventy Waldensian converts emigrated and settled in Utah, many prominent Latter-day Saint families—Beus, Cardon, Malan, Rivoir, Justet, Stale, Bertoch, Pons, and Chatelain—are descendants of these Italian pioneers. As the next chapter demonstrates, they added their unique cultural thread to the tapestry of the early church and made significant contributions to the communities in which they live.[71]

Notes

[1] Millennial Star, 25 August 1855, 538.

[2] Journal of Samuel Francis (June-July 1855), 79.

[3] Daniel Tyler, “Diaries 1853–1855,” 1–2.

[4] Francis, journal, 18 September 1855, original spellings preserved.

[5] Tyler, “Diaries 1853–1855,” 1–2.

[6] Francis, journal, 20 September 1855.

[7] Tyler, “Diaries 1853–1855,” 1–2; and Francis, journal, 20 September 1855.

[8] Francis, journal, 21–24 September 1855.

[9] Francis, journal, 18 November 1855.

[10] Millennial Star, 8 March 1856, 157; Francis, journal, 15 February 1856.

[11] Francis, journal, 6 April 1856.

[12] Francis, journal, 11, 14 April, 5 May 1856.

[13] Millennial Star, 2 August 1856, 491.

[14] On Weisbrodt, see “Our Heritage” (Morgan, UT: Samuel and Esther Francis Family Organization, 1984), 29–31.

[15] Millennial Star, 4 April 1857, 218.

[16] Viale Belvedere (now named Via Fratelli Calandra) was located near the flat utilized by Jabez Woodard and Francis Combe on Via della Chiesa in 1852.

[17] Francis, journal, 2 July 1856.

[18] Francis, journal, 6 July 1856.

[19] Francis, journal, 14–15, 28–30 July and 1–9 August 1856.

[20] Apparently Francis encountered Ludovico Gazzoli who, although eighty-two at the time, was still a member of the College of Cardinals until his death in 1858. The Protestant minister was Amedeo Bert, a Waldensian Pastor who preached to the legations of Protestant denominations in Turin. Bert was particularly noted for advancing the thesis that Waldensians had ancient origins that stretched back to the primitive church and for aggressively challenging the prerogatives of the Catholic Church in Piedmont. See, e.g., “An Account of the Trial of Signor Amedeo Bert, Vaudois Pastor of Turin” in 1851 in the Catholic Layman [Dublin, Ireland] 1, no. 8 (August 1852).

[21] Francis, journal, 6 July 1856.

[22] Millennial Star, 4 April 1857, 218–19; Francis, journal, 24 September 1856.

[23] Alessandro Gavazzi, Cenni biografici del dottore L. Desanctis (Ebd. 1870).

[24] Francis, journal, 6 September 1856. Desanctis eventually published without attribution an article in the Waldensian press concerning Mormonism. See [Luigi Desanctis], “I Mormoni,” L’Amico di Casa, IV, 1857 Almanac (Torino: Claudiana, 1856), 109–22. Ironically, Costantino Reta, who four years earlier complimented Lorenzo Snow concerning the Italian translation of the Book of Mormon, recommended that the article be published. In fact, Reta claimed in a letter to Desanctis that he did not know that Mormons were in Italy and that they should be expelled. See Letter from Costantino Reta to Luigi Desanctis, September 1856, MS Comba, Archives, Facoltà di Teologia Valdese a Roma.

[25] Francis, journal, 1 August 1856; This episode was also recorded in Il Risorgimento, 28 July 1856; “Torino—Il Risorgimento, giornale,” La Buona Novella, 1 August 1856; “La Buona Novella e i Mormoniti,” L’Armonia, 15 August 1856, 729.

[26] Charles Weisbrodt, who was from Canton Berne, Switzerland, lived in Turin as early as 1830 because his marriage was blessed on 3 June of that year by Pastor J. P. Bonjour in the Chapelle Prussienne, where the Waldenses and all Protestants met in Turin. Charles Weisbrod (as it is written in the church record in Turin) and his wife, Emilie, were Protestants, and their daughter Esther attended the Waldensian school in Turin. (The authors are grateful to Flora Ferrero for providing this information.) Note that historical records show variant spellings of the family name “Weisbrodt,” and the Francis family history lists the father’s first name as David, not Charles. See “Our Heritage,” 29–31.

[27] Francis, Journal, 12 September 1856.

[28] Francis, journal, 30 August, 15–16 September 1856.

[29] Francis, journal, 1, 6–11 September, 1856. Ruban was allowed to continue his missionary service in Switzerland. He eventually emigrated to the United States, where he continued to have contact with the church. President Smith stayed in Ruban’s home in New York while en route to his second mission in Europe in September 1860. John Lyman Smith, 1828–98, “Diaries 1859–1880,” Church History Library.

[30] See Parley P. Pratt, Mariage et moeurs à Utah (Genève, Switzerland: J. L. Smith, 1857).

[31] Luke 22:35.

[32] Millennial Star, 4 April 1857, 219; and Francis, journal, 11 December 1856.

[33] Francis, journal, 11 December 1856.

[34] Millennial Star, 4 April 1857, 219; and Francis, journal, 31 December 1856.

[35] Francis, Journal, 6 February 1857.

[36] On this, see B. H. Roberts, A Comprehensive History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 6 vols. (Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Press, 1965), 4:119; Thomas G. Alexander, “Wilford Woodruff and the Mormon Reformation of 1855–1857,” Dialogue 25 (Summer 1992): 26, 28; Gustive O. Larson, “The Mormon Reformation,” Utah Historical Quarterly 26 (January 1958): 44–63; and Paul H. Peterson, “The Mormon Reformation of 1856–1857: The Rhetoric and the Reality,” Journal of Mormon History 15 (1989): 59–87.

[37] Millennial Star, 28 February 1857, 129–34; and Letter from Brigham Young to Orson Pratt, 30 October 1856, Brigham Young Letterbooks, Church History Library, cited in Peterson, “The Mormon Reformation” (PhD diss., Brigham Young University, 1981).

[38] Francis, journal, 8–10 February 1857.

[39] Millennial Star, 4 April 1857, 219

[40] Francis journal, 29 January 1858; and Our Heritage.

[41] See Leonard J. Arrington and Davis Bitton, The Mormon Experience: A History of the Latter-day Saints (New York: Random House, 1980), 164–84; and Arrington, Great Basin Kingdom: An Economic History of the Latter-day Saints, 1830–1900 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1958), 245–56.

[42] David J. Whitaker, “Brigham Young and the Missionary Enterprise,” Lion of the Lord: Essays on the Life and Service of Brigham Young, ed. Susan Easton Black and Larry C. Porter (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1995), 89.

[43] La Buona Novella 17 (16 September 1857), 279.

[44] L’Armonia 1 (1 January 1858), 3.

[45] L’Armonia 18 (25 January 1858), 1.

[46] L’Armonia 64 (19 March 1858).

[47] L’Armonia 200 (2 September 1858).

[48] Giacomo Margotti, Roma e Londra Confronta (Torino: Fory e Dalmazzo, 1858), 225–26; Francesco Cavalleri, La religione Cattolica e la società (Torino: Giacinto Marietti, 1864); Luigi Rendu, Il Proselitismo Protestante in Europa (Firenze, 1865). See also Anon., Popolo all’Erta: un Valdese Ti Uccella! (Livorno: Tip. Fabbreschi e C., 1861) in which the author compared the heresy of Protestants (including Waldensians) to Mormons.

[49] [Karl August von Reisach], “Il Mormonismo nelle sue attinenze col moderno Protestantismo, La Civiltà Cattolica, 4th ser., 6 (3 May 1860), 391–413. Von Reisach relied on Josef Edmund Joerg [Jӧrg], Geschichte des Protestantismus in Seiner neuesten Entwick lung, 2 Bände (Freiburg, Br., 1858). For a translation and discussion of von Reisach’s article, see Mark A. Noll, “A Jesuit Interpretation of Mid-Nineteenth-Century America: ‘Mormonism in Connection with Modern Protestantism,’” BYU Studies 45, no. 3 (2006): 39–74. For a discussion of the appearance of this essay in chronological context, see Michael W. Homer, “The Church’s Image in Italy from the 1840s to 1946: A Bibliographic Essay,” BYU Studies 31, no. 2 (Spring 1991), 83–114.

[50] Giuseppe Fovel, Il Mormonismo e la donna (Firenze: Galileiana di M. Cellini, 1864). Jules Rémy, a French botanist and geologist, visited Salt Lake City in 1855 and five years later published Voyage au pays des Mormons: Relations, géographie, histoire naturelle, histoire, théologie, mœurs et coutumes, 2 vols. Paris: E. Dentu, 1860. For several decades Rémy’s book, which was also translated in English, was a major source on Mormonism for many European travelers. The other French writers cited by Fovel included L. A. Meunier, Frédéric Passy, C. De Sault, Paul Janet, and H. Taine.

[51] The earliest Italian traveler who encountered Mormons was Samuele Mazzuchelli, a Dominican priest, who met Joseph Smith in Nauvoo, Illinois (1842). After the Mormons settled in Utah and opened the Italian Mission, Leonetto Cipriani (1853), Enrico Besana (1868), Francesco Vavaro Pojero (1876), Francesco Carega di Muricee (1872), Giovanni Vigna dal Ferro (1881), Carlo Gardini (1883), Augusto Torlonio (1887), and many other Italian visitors traveled to Mormon settlements and wrote accounts of their encounters. See Michael W. Homer, “The Church’s Image in Italy from the 1840s to 1946: A Bibliographic Essay, BYU Studies 31, no. 2 (Spring 1991): 83–114. See also Michael W. Homer, On the Way to Somewhere Else, concerning the accounts written by Mazzuchelli, Cipriani, Besana, Vavaro Pojero, Gardini, and Vigna dal Ferro.

[52] Giovanni Perrone, L’Apostolato Cattolico e il Proselismo Protestante (Genova: Dario Giuseppe Rossi, 1862), 587–632. Perrone, like karl August von Reisauh, relied heavily on Joseph Edmund Joerg [Jörg]. Perrone also mentioned Mormons in his Il Protestantismo e la regola di fode, 3 voll. [Roma: Civilta Catlolica, 1853), 3:281; De Matrimonia Christiano (Leodii: H. Dessain, 1861) 216–218; Lide Christiano della Chiesa distrutti nel Protestantismo (Genova: Dario Giuseppo Rossi, 1812), 152; and Praelectiones Thelogicae del virtutibus, Fidel, spel, caritatis (Ratisbonae, sumptibis, Chartis et Typis Frideric, Pustet, 1865), 159.

[53] William J. Conybeare, “Il Mormonismo dall’ Edinburgh Review,” in Origini Europee—religioni-viaggi-studi etnografici, vol. 5 of Saggi e riviste (Milano: G. Daelli e C., 1865), 159–239.

[54] Luigi Stefanoni, Storia Critica della Superstizione (Milano: Presso Gaetano Brigola, 1869), 344–75.

[55] Stefanoni, Storia Critica della Superstizione, 372.

[56] Millennial Star, 3 October 1857, 634–35.

[57] Millennial Star, 3 October 1857, 634.

[58] Millennial Star, 29 May 1858, 346–47.

[59] The eight were Bartholomew Bonnett (1856), Marie Louise Chatelain and Marthe Rostan (1860), Marie Justet and Anne Rivoir (1861), Lydie and Catherine Chatelain (1863), and finally Jacob Rivoir, the president of the Italian conference (1866). See Michael W. Homer, “‘For the Strength of the Hills We Bless Thee’: Italian Mormons Come to Utah,” unpublished paper, Church History Library, 71–72.

[60] Millennial Star, 10 August 1861, 510.

[61] Guglielmo Giosue Rossetti Sangiovanni (1855–1915) was the son of Benedetto Sangiovanni and Susannah Rogers, who were married in New York in 1833. Apparently the couple lived in London after their marriage. Benedetto was an Italian artist skilled in the fine art of miniature models of humans and animals. The family (at least the mother and two sons) emigrated to Utah. “Sangiovanni, Susanna Mehitable Rogers, 1813–1905, Collection 1825–1905,” MS 2986, Church History Library. Unless otherwise noted, all subsequent quotations and material dealing with Sangiovanni’s experience are found in this source.

[62] Letter dated 21 December 1864, St. Germain (San Germano), Italy. “Sangiovanni, Susanna Mehitable Rogers, 1813–1905, Collection 1825–1905.”

[63] Millennial Star, 4 April 1863, 222.

[64] Chauncey W. West, “Letter to Lorin Farr,” in Papers of Lorin Farr, MSS 2952, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT. We are indebted to David J. Whitaker for this reference.

[65] Millennial Star, 8 June 1867, 364.

[66] “Manuscript History and Historical Reports, Switzerland Zurich Mission,” LR 8884 2, vol. 4, Index to Swiss, Italian, and German Mission, 1861–67 and reports.

[67] Giorgio Tourn, interview with James Toronto, 4 May 1999, Torre Pellice, Italy.

[68] Franklin L. West, Life of Franklin D. Richards (Salt Lake City: Deseret News Press, 1924), 152–57; see also Grant Underwood, The Millenarian World of Early Mormonism (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1993), 43, 50–51.

[69] Snow, The Italian Mission, 23.

[70] Millennial Star, 11 November 1854, 706, and 4 April 1857, 219. Even though the number of converts totaled fewer than two hundred during the seventeen years of missionary work in Italy, this number is substantial when one considers that it represents “almost 1 percent of the small Protestant group that Snow initially targeted for conversion in the Kingdom of Sardinia.” Homer, “Like the Rose in the Wilderness,” 34.

[71] One example of Waldensian influence is the popular Latter-day Saint hymn “For the Strength of the Hills.” It is based on a poem written in 1835 by the English poet Felicia Hemans, entitled “Hymn of the Vaudois Mountaineers in Times of Persecution.” Lorenzo Snow copied the poem into a letter written to Orson Hyde in January 1851 (Snow, Italian Mission, 21–22), and it was later adapted by Mormon journalist Edward L. Sloan for inclusion in the Latter-day Saint hymnal. See Karen Lynn Davidson, Our Latter-day Hymns: The Stories and the Messages (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1988).