Increasing Maturation and Acceptance in Public Life, 1985-2012

James A. Toronto, Eric R Dursteler, and Michael W. Homer, "Increasing Maturation and Acceptance in Public Life, 1985-2012," in Mormons in the Piazza: History of the Latter-Day Saints in Italy, James A. Toronto, Eric R. Dursteler, and Michael W. Homer (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2017), 383-422.

The era of expansive church growth in the 1970s and early 1980s was followed by a period in which the church experienced challenges with slower growth rates, changing demographics among its membership, and high rates of inactivity. But this period also witnessed maturation of the Italian membership, more sophisticated use of mass media to improve the image of Mormonism, regular involvement at the local level in nonproselytizing civic activities (such as humanitarian and interfaith outreach), and increasing political and social integration of the church in Italian life.

The Shifting Sands of Italy’s Religious Landscape

Currents of change set in motion during the anni di piombo profoundly reshaped attitudes toward spirituality and individual choices in the religious marketplace in Italy during the 1980s and beyond. One study described the shifting landscape as “a breaking down of a cultural universe, somewhat homogeneous, largely informed by religious values” that contributed to diminishing “the influence of religion on the condition of life of many sectors of the population.”[1] A recurrent theme of scholarship during the 1970s and early 1980s postulated an irreversible process of de-Christianization and of an eclipse or even extinction of religion. Some Italians welcomed these changes as progress toward liberalization and liberation from the fetters of tradition, while religious voices denounced them as evidence of a spiritual and moral vacuum created by consumerism, alienation, and lack of direction in Italian society.[2]

But more than secularism or declining belief in transcendent powers, growing sentiments of apathy and antipathy toward organized religion influenced religiosity in Italy. A greater emphasis on individual rather than institutional pursuit of spiritual fulfillment became the trend—described by religious scholars in terms such as “spiritualità fai da te” (do-it-yourself spirituality) or “credere senza appartenere” (believing without belonging). One study concluded that the public rejection of the Roman Catholic Church’s position on the divorce referendum in 1974 and the abortion referendum in 1981 painted “a clear picture of the post-war generation’s widespread loss of faith in the religious institution”:

What we see emerging is a decline of active church participation in favor of an individual and inner spirituality. The true detachment of this generation is not from the religious beliefs but from the institutions representing them: it is not a decline of the sacred as much as a decline of the church’s authority as a moral guide. . . . Ultimately, the overall cultural development of the post-war generation marks the affirmation of individualism, which is the heart of modernity, more than of secularization. While belief in the sacred is still plausible it is evident that the ecclesiastical institutions have lost authority in the domain of private life.[3]

The emphasis on individual and inner spirituality, far from bringing about the decline of religion, helped fuel a “return of the sacred” in societies worldwide and opened the door to greater pluralism and relativism in religious matters. Survey data indicated that the number of atheists and agnostics began to wane, while the percentage of those who believed in higher spiritual powers, prayer, meditation, and afterlife began to wax—to about 80 percent in most countries.[4] In Italy, survey data indicated that about 20–32 percent of the population attended religious services on a regular or semiregular basis. A major trend is located outside of the major religions and the historic churches in the more than 40 percent of Italians who “believe without belonging” to a religious organization and in the growing adherence—about 2.5 percent of Italian citizens—to new religious movements and minority (non-Catholic) religions.[5]

The impact of these trends on the religious landscape in Italy became apparent by the late 1980s. Massimo Introvigne suggested that, due to shifting attitudes about the role of religion and waves of immigration from non-Catholic countries, more and more Italians were persuaded “that theirs was now a multi-religious society. . . . Italian religious economy was becoming fully deregulated.” Although this expansion of religious pluralism was “more apparent than real, . . . the perception of pluralism changed dramatically.”[6] A Protestant scholar noted the transition of Italy from “mono-confessionalism” to pluralism, “from the religion of the Italians [i.e., Catholicism] to Italy of the religions” but also cautioned that “the time has not yet arrived of full pluralism in the framework of a secular society.”[7] A 1991 study corroborated the need for caution, indicating that fewer than one million individuals belonged to non-Catholic religious movements and hypothesizing that, unlike many other Western countries, “Italy is not yet a land that inclines to religious pluralism, that is open to a variety of religious confessions and expressions. That would suggest why non-Catholic religions may have difficulty in making converts and in enlarging their sphere of influence in Italy.” The study concluded that religious minorities would likely remain small, but important, in the future of Italian society.[8]

Along with an emerging pluralism, Italy’s religious attitudes began to reflect less dogmatism. The Garelli survey found that during the 1980s, 87 percent of Italians viewed faith as “a great force in life” but that only 37 percent believed that there was one true church. More than 60 percent believed in a “relative” conception of religion: that no religion has absolute truth and that all have partial truths. “The cultural implications connected to such a conception of religion are evident,” the authors concluded. “A religious reference detached from the idea of truth is less stringent and seems destined to have minor influence on the cultural orientation and life conditions of the people.”[9]

In the 1980s, while religious attitudes were undergoing transition, economic conditions were improving dramatically, signaling a “second economic miracle” after more than a decade of deprivation. While the first “miracle” of the ’50s and ’60s had occurred primarily in urban rather than rural areas and in the North more than the South, the upswing of the ’80s brought greater affluence to all social groups and all geographic areas in Italy. In effect, one historian observed, the economic boom marked the “beginning of the end of the mass society of the nineteenth century” and Italy’s transformation into a modern nation centered on individualism, consumerism, and increasing religious and political pluralism.[10]

The political landscape underwent radical change as well. The Italian State launched investigations in the early 1990s of corruption among political elites. Dubbed the “Clean Hands” campaign, the investigation uncovered a broad and deeply rooted system of bribes, kickbacks, and extortion, connected in some cases to organized crime. Convictions led to the downfall of many influential politicians and the demise of parties like the Christian Democrats (allied closely to the Catholic Church) that had dominated political life for nearly half a century. This scandal, referred to as “Tangentopoli” (from the Italian tangente, kickback or bribe), deepened Italians’ already profound cynicism about their politicians. A major evolution of Italian political life occurred in 1994 when the first national elections were held following the collapse of the old political order, leading to the creation of many new or realigned parties.

Taken together, these factors—growing disdain for institutional worship, ambivalence about religious truth, economic affluence and consumption, and despair about the efficacy of civil life—left an enduring mark on Italian society. Sociologist Marino Livolsi summed up the enduring changes wrought by these developments during the last decade of the twentieth century:

In the past few years, after periods of well-being in the 80s, we see the obscure but strong sensation of living badly in a context without values or norms [and] of the complexity of social life perceived as ever more threatening and without meaning. . . . Pessimism and insecurities mix together giving place to disaffection with social life in a scenario where economic and political crises loom on the horizon. Italy, which has never been a nation, is trying hard today to find common values upon which to remake itself.[11]

A Slowdown in Conversions and Establishment of Stakes

These social and religious changes in Italian society are among a constellation of factors that accompanied a decline in conversion and retention rates in the church. The annual number of converts began to drop beginning in the mid-1980s even while Italian church members shouldered more leadership positions, church infrastructure improved, and efforts to improve the church’s image in Italy accelerated.

While the decline in growth was associated with external factors in Italy, it stemmed more obviously from internal issues within the church. Between 1981 and 1984, the number of full-time foreign missionaries fell sharply due to new visa regulations issued by the Italian government and to the church’s policy that reduced missionary service to eighteen months instead of two years. Because of the long delays required to obtain visas and stricter enforcement in renewing them in-country, some missionaries were required to leave Italy and were assigned to other missions. A dwindling pool of replacements for those going home diminished the missionary force. The number of missions in Italy was reduced from four to three in June 1982 with the closure of the Padova Mission, and numerous cities were closed to missionary work, including Lucca, Udine, Parma, and Reggio Emilia.[12]

The emergence of multigenerational convert families has boosted church stability and maturity of church leadership. This photo shows for generations of the Panebianco family in Rome. From left to right, Maria Panebianco, Cecilia Panebianco Squarcia, Sara Squarcia Dini Ciacci, and Rebecca Dini Ciacci (the babe in arms). Courtesy of Alessandro Dini Ciacci and Dale Boman.

The emergence of multigenerational convert families has boosted church stability and maturity of church leadership. This photo shows for generations of the Panebianco family in Rome. From left to right, Maria Panebianco, Cecilia Panebianco Squarcia, Sara Squarcia Dini Ciacci, and Rebecca Dini Ciacci (the babe in arms). Courtesy of Alessandro Dini Ciacci and Dale Boman.

It was a period of retrenchment within Mormon congregations too, as leaders proactively sought to “prune” by excommunicating members who were rebellious or nonobservant.[13] In March 1984, for example, President Turner of the Catania Mission “went to Palermo to preside at a Church court for twelve people.” In the previous months, over forty people had been removed from the church. Turner found that many had been baptized without adequate knowledge of the church and “went inactive immediately.” He also believed that the weakness of the home teaching program made it “nearly impossible to keep anyone in the church without a strong testimony.”[14]

The change from missionary to Italian leadership adversely affected growth initially, but over time brought greater strength and stability to the Mormon community. One church leader stated that in the late 70s and early 80s, “the Italian members began taking over the leadership of the church, replacing the missionaries who had done everything at first. This was a traumatic change in some areas—a period of transition that caused more turnover of members because of inexperienced leadership.” He added that now, with the rise of a second generation of Italian members, the quality of leadership had greatly improved. His wife, also a longtime member, spoke about “the early days, when the missionaries had a greater role” in running the branches: “We all felt ownership and responsibility for the church. But this is not so today. Today we leave the work for the leaders. On the other hand, now there is a stronger feeling of security—a stronger foundation. We have entered a phase of maturation. We might miss the fervor of the early days, but today there is more maturity and experience in the church.”

These factors produced a period of slower growth but, in the longer term, fostered increasing maturity and strength in Italian Latter-day Saint congregations. In the wake of President Kimball’s 1977 tour of Italy and in the midst of robust growth, church leaders began making plans for the imminent creation of stakes throughout Italy. But with the downturn in numbers of missionaries, numbers of convert baptisms, and activity rates in the 1980s, requests to create stakes were routinely rejected by church headquarters due to insufficient active membership. As a consequence, some church members became discouraged when efforts over many years to become a stake fell short. In Rome, for example, plans for a stake were first discussed in 1977, but records show that not until twenty years later were organizational changes made and a petition prepared to create a stake, even though baptismal rates were still low.[15] Permission was again denied, and the Rome stake was not created until 2005.

The Impact of Migration on Church Growth

Beginning in the latter half of the nineteenth century and continuing into the twentieth, mass movements of people across geographical space and national boundaries have marked one of the watershed changes in human history. Unprecedented in their scale and frequency, these migrations brought about a mingling of racial, ethnic, and religious groups—a “marbling of civilizations and peoples” that created “a new georeligious reality,” as one scholar aptly observed—generating conflict in the public arena and inducing new debates about national identity, human rights, and the nature of civil society.[16] Following World War II, the countries of Western Europe witnessed an influx of non-European immigrants from newly-liberated colonies in Africa, the Middle East, and South Asia and from Eastern European countries after the collapse of the Soviet Union.

By the late 1980s, with one of Europe’s strongest economies, Italy “ceased to be a net exporter of labour” and became a destination for large numbers of extracomunitari—immigrants not belonging to the European community.[17] In 1991, the number of legal and illegal immigrants was estimated at about 800,000 or 1.4 percent of the population, and the numbers continued to climb exponentially.[18] By 2007, there were approximately 3.7 million immigrants from more than 180 nationalities, of which 1.8 million (49.6 percent) were from Europe (41 percent from central and eastern Europe), 800,000 (22.3 percent) from Africa, 663,000 (18 percent) from Asia, and 356,000 (9.7 percent) from the Americas (8.2 percent from South America). The relative strength of local and regional economies determined the geographical distribution of these immigrant populations—33.7 percent in the northwest, 25.9 percent in the northeast, 26.7 percent in the central, 10.2 percent in the south, and 1.1 percent on the islands—facts that significantly influenced patterns of conversion and growth for the Mormon Church.[19]

As a result of these unprecedented demographic shifts, Italy “fully embarked on a historic, long-term process of change.” Immigration was no longer a “transitory fact” but “a lasting consequence” of the country’s social and economic development.[20] Initially, as with other destination countries in Europe and North America, the rapid insertion of foreign populations created new realities and conflicts in the public square. Italy had always been a relatively homogeneous nation and was therefore ill-prepared to accommodate a multiethnic society. To a greater degree than the southern migrants seeking employment in the northern regions of Italy and Europe in the 1950s and ’60s, the new generation of migrants had difficulty finding adequate work and other productive means of integrating into society. Packed into squalid makeshift camps, sleeping in train stations, loitering in streets and parks, and held responsible for a rising crime rate, the immigrant newcomers elicited hostility—“they were true outsiders, viewed with suspicion and horror.”[21]

But with time and greater familiarity with their new immigrant neighbors, Italians softened their attitudes somewhat. More open-minded and tolerant views about integration of minorities gradually began to take hold. According to a comprehensive study in 2000, for example, only 17 percent of Italians said that they would object to having an immigrant as a neighbor (although the figure rises to 28 percent in the conservative Northeast); 69 percent supported laws to make it easier for foreigners born in Italy to acquire citizenship; 73 percent were in favor of legalizing immigrants who have jobs; and a vast majority (84 percent) believed that minorities should not feel obligated to abandon their culture in order to be accepted in Italian society. On the economic front, the report found that, overall, “immigrant labor appears to serve a complementary rather than a competitive role in relation to native Italian labor,” and is “becoming crucial to the survival of [the Italian] economy.”[22] During that same year, a poll conducted by the European Commission concluded that, of all the countries in the European Union, Italy ranked near the top in the number of citizens who did not blame immigrants for high unemployment rates or welfare costs.[23] A study carried out in May 2006 in eight Western countries found that Italian public opinion on immigration had improved over the past decade, with nearly half of those polled (45 percent) viewing immigrants as a positive presence in society.[24] However, this trend toward greater tolerance of immigration has slowed recently due to the waves of migrants arriving in southern Europe since the so-called Arab Spring uprisings that began in 2010. Anti-immigrant sentiment and right-wing parties have been increasing.

These economic and social forces that produced large-scale migration of populations exerted both positive and negative impact on the growth of the church in Italy. One trend that adversely affected the stability of local congregations was noted earlier: emigration of members from Italy to other countries in Europe and South America and to the United States. Another important development brought about a shift in the demography of church membership: while the number of conversions among native Italians began to decline in the mid-1980s, an increasing percentage of converts came from the immigrant communities that were beginning to form in Italian society. By 2007, about 60 percent of all convert baptisms in the Europe West Area were immigrants, and as of 2012, 20 percent of the approximately 25,000 church members in Italy were immigrants.[25]

The geographic distribution of church membership (see graph) reflects the impact of migration, both international and domestic. The vast majority of Italian church members are located in the central and northern regions of Italy where economic growth has historically been more robust and sustained: 71 percent (52 percent in the north and 19 percent in the central), as opposed to 29 percent in the south. In 2012, six of the eight stakes in Italy were located in the northern and central regions.

This concentration is due to two factors. First, as noted above, nearly 90 percent of Italy’s immigrant population—the primary pool of potential converts in Western Europe—resides in the north or central areas of the peninsula where economic opportunities are more abundant. This fact helps explain why, since the late 1970s, the missions located in Milan and Padua have had greater success finding converts than the missions further south in Rome and Catania. While hundreds of immigrants disembark on the shores of southern Italy each year from the Balkans, the Middle East, and Africa, the vast majority make their way to points farther north where they are more likely to find work, settle down, and embrace a new religion that can aid their quest for meaning, security, and integration in society. Church statistics in Italy corroborate this trend: in northern and central regions (Turin, Lombardy, Venice, Rome), two out of three convert baptisms (67 percent) are immigrants, while in southern areas (Sicily, Calabria, and Puglia) only one in four converts (25 percent) is an immigrant.[26]

A second factor contributing to a concentration of church membership in northern Italy is the long-standing pattern of internal migration of Italian citizens from south to north due to the perpetually harmful effects of high unemployment, slow economic growth, and organized crime in the mezzogiorno.[27] In the earliest years after the reopening of missionary work, cities in southern Italy often led the way in convert baptisms, only to see a steady stream of Saints migrate to the north—college students, church leaders, returned missionaries, and entire families—severely depleting congregations. A senior church leader in Bari observed that there would be two stakes rather than one in the Puglia region were it not for the continual northward migration of church members from the south. A similar trend has been observed by other researchers in Latter-day Saint missiology who noted the social and demographic “holes” created in church units by outmigration from rural to urban and suburban areas in Japan, and by emigration of Germans to the United States.[28]

As the immigrant presence in congregations grew in the late 1980s and beyond, church leaders faced new challenges to the growth and stability of congregations. Communication between Italian members and immigrant converts was often problematic because of cultural and linguistic differences. To address this problem, some congregations began offering Italian classes to help immigrant church members adjust more quickly and to attract immigrant investigators. In some larger cities such as Palermo, Rome, and Milan, the number of immigrant converts reached a critical mass that led to a decision to form international branches for non-Italian members. Typically these services were held in English, aided by full-time missionaries and expatriate LDS families. But by the 1990s, Spanish-speaking branches and wards were operating in Rome and Milan to accommodate the influx of immigrant members from Central and South America.

The socioeconomic gap between immigrant converts, who often lived in extremely indigent circumstances, and Italian members, whose material circumstances were far more favorable, created some tensions. Attitudes in Italian society occasionally colored relations in local congregations as church members found themselves on the horns of a dilemma: wanting to assist their new immigrant brothers and sisters but also harboring some of the same fears and reservations about the “other” that characterized the times in Europe.[29] In some instances missionaries reported feelings of frustration due to a perceived lack of enthusiasm on the part of Italian members in welcoming immigrant converts, and immigrants at times felt marginalized in their congregations and drifted away from church activity.

Factors other than simply cultural intolerance or ethnic bias must be taken into account, however, in order to understand this attitude of caution in accepting immigrant converts. With the influx of immigrants into local congregations, church officials began issuing guidelines to local leaders and missionaries that mandated closer scrutiny before baptizing refugees, immigrants, and asylum seekers. The new policies were intended to address “concerns about true conversion, legality, safety, and family unity” and grew out of “political situations and peculiar problems” which the church was facing during this time. These included the issue of Muslim converts who might face severe backlash from their family members or religious community, and the problem of “religious tourists” who join the church or move from one church to another for economic gain.[30]

The problem of integration of immigrant converts must also be viewed in the context of emerging congregations and new church members who, despite their best intentions, sometimes felt overwhelmed by the enormity of the legal, financial, and health needs of immigrants. The history of local congregations “shows a very small group of leaders, sometimes inexperienced and struggling with problems of their own, trying to solve the continuous serious problems of individual members. Many of these leaders burn out in the process. In that context, it is understandable, though not justifiable, that they find it difficult to wholeheartedly welcome yet more people with pressing problems. . . . Such regrettable reserve stems not from intolerance but from feelings of powerlessness and even despair because we cannot properly help them.”[31] Our research confirmed that feelings of inadequacy and “burn out” contributed to high inactivity and dropout rates among church members in Italy.

Immigrant converts have dramatically altered church demographics in Italy and elsewhere in Europe. For example, young single adults who attend LDS institute classes in Rome, like the one shown here, come from many countries including Moldavia, Nigeria, Peru, El Salvador, Argentina, Uruguay, Brazil, and the Philippines. Courtesy of Ugo Perego, Rome.

Immigrant converts have dramatically altered church demographics in Italy and elsewhere in Europe. For example, young single adults who attend LDS institute classes in Rome, like the one shown here, come from many countries including Moldavia, Nigeria, Peru, El Salvador, Argentina, Uruguay, Brazil, and the Philippines. Courtesy of Ugo Perego, Rome.

Despite these challenges stemming from the “marbling of civilizations” in Europe and some tensions at the local level, the trend of immigrant converts proved, on balance, a great boon to church growth in Italy. In most cases, immigrants were accepted warmly in their Italian congregations that benefitted, in turn, from the cultural diversity and spiritual strength of the newcomers and became more unified through working together to address humanitarian needs. Programs like LDS Social Services that provide an institutional support structure to church units in North America began only recently (2010) to be established in Italy. In the meantime, Italian church members stepped in to fill the void, contributing substantial time and means to arrange for language instruction, legal advice, employment, health care, transportation, and housing. Based on these activities throughout European church units, one historian concluded that “one of the finest elements of Mormon social history in Europe since 1970 is the unselfish humanitarian service offered to needy [immigrants] by a relatively small number of members with very limited resources.”[32]

A stake president in northern Italy, Maurizio Bellomo, described how immigrant converts from various backgrounds positively impacted church growth. In many cases, immigrants from Central and South America were already members of the church who had held responsible leadership positions in bishoprics, stake presidencies, and Relief Society presidencies in their home countries. They arrived in Italy and were immediately able to assume leadership roles and strengthen Italian congregations with their experience, confidence, and maturity. Converts from countries like Ukraine and the Philippines, on the other hand, had relatively little or no experience in church service but enriched their new religious communities, because they tended to be highly skilled and educated, often possessing college degrees and talents in music and teaching. Bellomo concluded that immigrant Mormons “are a great resource. Without this influx into the Church, we would not have been able to form as many stakes as we have” in the past ten years.[33] On balance, then, the infusion of immigrant converts with their talents and experiences, together with the increasing intermarriage of immigrant and Italian members, has represented a fortifying and unifying influence in church growth.

After 2005, with greater indigenous leadership capacity and an influx of immigrant converts, the creation of stakes began to accelerate. While only three stakes were formed in Italy in the first four decades of missionary work (Milan, 1981; Venice, 1985; and Puglia, 1997), seven stakes were created in a nine-year span from 2005 to 2014: Rome in 2005, Alessandria in 2007, Verona in 2008, Palermo in 2010, a second stake in Milan in 2012, a second stake in Rome in 2013, and Florence in 2014—a total of ten stakes.[34] There is also evidence of the maturation of local leadership in the calling of Italians to senior positions in the church hierarchy: seven mission presidents (Leopoldo Larcher, Felice Lotito, Vincenzo Conforte, Giuseppe Pasta, Mario Vaira, Giovanni Ascione, and Sebastiano Caruso), a Swiss temple president (Mario Vaira), and numerous regional representatives, area seventies, and stake presidents.

The evolution in Mormon congregations from homogeneity to cultural and ethnic heterogeneity will no doubt continue, if not accelerate, in years to come. Migration of immigrant converts into Italian church units, and of many Italian church members to Latter-day Saint units in Europe and North America, has already altered the growth patterns and face of Italian Mormonism, and there is little reason to expect that the trend will abate. On the contrary, this phenomenon is part of a megatrend worldwide, “one of the transforming moments in the history of religion,” according to Philip Jenkins. During the past century “the center of gravity in the Christian world has shifted inexorably” toward Africa, Asia, and Latin America: “Christianity should enjoy a worldwide boom in the new century, but the vast majority of believers will be neither white nor European.” Jenkins predicts that “by 2050, only about one-fifth of the world’s 3 billion Christians will be non-Hispanic whites.”[35] The same gradual but implacable forces of change are becoming increasingly evident in Mormonism too: in February 1996, church officials announced that the church “crossed a twentieth-century historic membership mark” with more members living outside the United States than inside.[36]

Church Public Affairs and the Evolving Image of Mormonism

One church member, echoing the concerns of many Italian Mormons about their image in society, stated that his greatest hope for the church was that it would “be recognized by the State and become better known so we’re not like Martians in the eyes of the public.” During the late 1980s and early 1990s, the church intensified its public relations activities in support of its goal to come “out of obscurity”[37] by achieving greater visibility in the public sphere and legal recognition from the Italian government. In Italy’s intesa system governing church-state relations (see chapter 14), factors such as public opinion, images conveyed in the media, and opposition by influential voices in the political arena carry great sway in government decisions about granting full religious status and rights to religious communities.

Church officials recognized that the public image of the church worked against their intesa and missionary efforts, mired as it was in Hollywood stereotypes about the mythic Old West of the nineteenth century. That media image had changed very little since the reestablishment of Mormon proselytizing in Italy in 1965, despite the church’s efforts to improve it through various public relations initiatives. These initiatives, however, had been ad hoc in nature, missionary focused, and loosely coordinated during the first two decades of church development. In the late 1980s the public affairs program took steps to tighten its organization in Italy and, staffed almost exclusively by Italian church members instead of foreign missionaries, began to carry out a more coordinated campaign to counteract anti-Mormon rhetoric and to raise the church’s profile through media, humanitarian, and interfaith activities.

Voices of opposition to the church’s presence in Italy continued to raise questions about its former practice of polygamy, whether it was truly a Christian faith, and if it was an American or an Italian organization. Although Catholicism ceased to be the official religion of Italy, and a monolithic Catholic voting bloc no longer existed, the national and local clergy still exerted significant impact on Catholic reaction to the message of Mormonism and other new religious movements. While the orientation of Mormonism, was generally less anti-Catholic than Jehovah’s Witnesses, Assemblies of God, and other Pentecostals, the Catholic Church resisted all efforts—hard-edged or not—to proselytize its members.[38] In addition, the pope—even a non-Italian one—continued to influence, to some extent, the political and religious climate in Italy.[39] Within the last four decades, the Italian press reported that the Pope criticized Jehovah’s Witnesses, Seventh-day Adventists, and Mormons because they were “religious sects which are not open to dialogue and are harmful to ecumenism.”[40] Some Catholic scholars suggested that Mormon proselytism was a major stumbling block to establishing good relations between Catholics and Mormons on an international scale.[41]

In addition to impact from the Catholic hierarchy, the image of Mormonism in Italy continued to be influenced by travel accounts and fiction by Italian authors.[42] As a result, while many Americans came to recognize that Mormonism had changed dramatically during the past one hundred years, a large number of Italians in the twentieth century continued to imagine Mormonism in its nineteenth-century environment. Many Italians associated Mormons with Utah and the practice of polygamy or confused it with other religions. In 1985 the notorious Aleister Crowley was identified as a Mormon because he advocated the practice of polygamy.[43] At least two Italian magazines confused the Amish in the film Witness with Latter-day Saints,[44] and Mormonism was frequently identified with “fundamentalist” groups that recognize Joseph Smith as a prophet and practice polygamy.[45] In 1993 the Council of Ministers approved the church’s application for government recognition, but one journalist emphasized that “Mormons do not like to talk about the old practice of polygamy which was abolished in 1890” and that “there are those who say they [the Mormons] are racists and are prejudiced against women.”[46] A sociological survey conducted in 1990 revealed that a significant number of Italians still believed that Mormons practiced polygamy, wore old-fashioned clothing, and dressed in black, and that Mormon men had long beards while their women covered their heads with bonnets.[47]

Most responses of Italian religious writers to LDS publications were sectarian and published by the Protestant churches (some with American roots but others rooted in the Waldensian Church), which had established a toehold in Italy and were apprehensive about Mormonism as a serious new competitor.[48] After Mormon membership had grown to approximately 10,000 beginning in the 1980s, two Catholic priests, Nicola Tornese and Pier Angelo Gramaglia, wrote polemical anti-Mormon works.[49] They were joined in 1987 by a conservative Catholic countercult organization, Gruppo di Ricerca e di Informazione sulle Sette (G.R.I.S.), which organized conferences and published materials attacking various new religious movements in Italy, including Mormonism.[50]

While fairly one-dimensional anti-Mormon articles continued to be written, more balanced perspectives on Mormonism also began to appear in Italy.[51] Massimo Introvigne and his Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR) have been at the forefront of this development.[52] Introvigne has written, presented, and published numerous papers about the church (in Italian, French, and English) and is the author of one of two books on Mormonism published by the Vatican Press,[53] which was favorably received by Latter-day Saint scholars.[54] He has also been active in debunking inaccurate depictions of Mormonism based on dated polemical paradigms in Catholic publications.[55]

In addition to the work of non-Mormon research organizations like CESNUR, the church’s public affairs program, coordinated by Italian church members, contributed significantly to improving the public image of Mormonism. In June 1988, the “grand opening” of the church’s Public Communications Office was held in Rome, and attendees at the press conference included reporters from various Italian news outlets, senior church officials from Italy, and the area offices in Frankfurt.[56] A restructured organization consisted of an area director in Frankfurt, Germany; a national director in Italy who coordinated the work of a national council of media specialists from various regions, all of whom reported to the senior leader (Area Seventy) in Italy; and a director or specialist in every church unit (stake, mission, district, ward, and branch) throughout Italy whose work was coordinated with the national organization and supervised by local priesthood leaders. Over the years various individuals served as national director: Giovanna Marino, Giancarlo Dicarolo, Giuseppe Galliano, Maurizio Ventura, Giuseppe Pasta, Tullio Deruvo, and Raimondo Castellani.

In order to combat negative press coverage and to heighten the church’s media profile, public affairs officials hired a company in Rome to provide a clipping service—monitoring daily press publications from throughout Italy and sending a copy of any article that discussed Mormonism. Members of the national council with expertise in journalism and media relations wrote well-reasoned responses to journalists who inaccurately reported facts or unfairly portrayed the church’s position on the issues. Often these rebuttals were published in the magazine or newspaper and led to opportunities for expanded coverage of the church in print or electronic formats. In 2006, to cite one example, an article published in the prominent daily newspaper Corriere della Sera alleged that the Mormon Church had blocked viewing in all theaters throughout Utah (“the state of the Mormons”) of the film Brokeback Mountain, a film depicting a romantic relationship between two men.[57] A few days later a letter to the editor sent to numerous newspapers throughout Italy accused the church of promoting bigotry, homophobia, and suppression of freedom of speech. The church’s public affairs council responded with a letter pointing out that the church supports the arts and was not involved in the decision of a few theaters to block the film. Latter-day Saint media specialists also sought opportunities to comment on positive developments in the media, contacting government ministries, politicians, and managers of national TV and radio stations to express support for their efforts to promote wholesome family values and to foster tolerant, pluralistic attitudes in society.[58]

High-visibility events continued to be a staple of the public affairs program (as they had been since the opening of the new Italian mission) but reached a crescendo beginning in the late 1980s. Coordinated with the area offices in Frankfurt and with public affairs officials at church headquarters in Salt Lake City, public appearances by Mormon leaders, scholars, celebrities, and performing groups were designed to attract maximum press coverage for the church in support of its missionary and legal recognition efforts and to emphasize the point that Mormons are normal people from many social and professional backgrounds.

Media coverage of Mormon-related stories occurred regularly at both the local and national levels. When the Italy Catania Mission celebrated its tenth anniversary in December 1987, public affairs officials organized a media event at the LDS chapel in Siracusa. The Italian Postal Service honored the church by introducing a new commemorative stamp in the presence of several Sicilian journalists and many local civic leaders including the mayor. City officials expressed appreciation for the contributions and exemplary conduct of the Mormon community.[59] In March 1988, the state-owned Rai Uno television station featured a presentation by BYU scientists about their recent discovery of the largest-known dinosaur pelvic bones.[60] At the National Library in Naples, another BYU scholar lectured on Multispectral Digitalization in the preservation of the Herculaneum papyri, and at other venues Mormon scientists have presented lectures and exhibits on the age of the earth, the Dead Sea Scrolls, and new religious movements in Italy.[61] Several national television stations devoted air time to the church’s growth in Italy, including the program Dieci minuti di . . . [Ten Minutes of . . .], which in the early 2000s sponsored a series of episodes in which Italian Mormons talked about their beliefs, family life, genealogy, education, and church programs for youth and children. These broadcasts reached a wide audience in Italy and elsewhere in Europe, eliciting many inquiries from the public and bolstering missionary work.[62]

To commemorate the 150th anniversary of the Mormon pioneers’ arrival in the Salt Lake Valley, a caravan of five horse-drawn wagons, accompanied by folk dancers and bluegrass musicians from church-owned Ricks College (now BYU–Idaho) and by Italian church members dressed as Mormon pioneers, paraded through the streets of Rome. An Italian film producer loaned the wagons to the Mormons, and the municipal police agreed to clear traffic for the event. While effective in attracting media attention, the incongruous spectacle of a Mormon wagon train on the cobblestone streets of the Eternal City drew some criticism from Italian church members who questioned whether this would only reinforce Mormon stereotypes and the church’s American image. One church leader observed that historical reenactments like these, while meaningful to Mormons, do not always transfer well to other contexts: “Pioneers of the western U.S. and the Mormon trail and handcarts don’t mean a lot to Italians.” Researchers have recorded similar sentiments in other areas of the church, like Japan, suggesting that celebrating the accomplishments of local Mormon pioneer converts might be more meaningful.[63] But the main goal of the activity, according to organizers, had less to do with publicity and more to do with church members’ making a statement about their own pioneering labors in Italy. It was their way of saying that Mormonism “is in Rome to stay” and constituted a “rallying cry” for creating a stake in Rome, the only major western European city without one.[64]

The high-water mark for public affairs during this period was unquestionably the Mormon Tabernacle Choir’s visit to Italy in June 1998. As part of a twenty-one-day tour of nine cities in seven European countries, the choir held concerts on 20 June in Turin at the Auditorium Agnelli del Lingotto and 22 June in Rome at the Accademia di Santa Cecilia. Press coverage of the choir, before and after its arrival, and of the church’s history, beliefs, and presence in Italy was distinguished by its scope and accuracy. Many of the nation’s major news outlets, both print and electronic, reported on the performance of the world’s most famous choir and noted its achievements: gold and platinum records, a Grammy award, many acclaimed international tours, and performances at several US presidential inaugurations. Italian reporters were impressed by the fact that choir members, while highly trained, were unpaid amateur musicians comprising many professions—teachers, office workers, engineers, business associates, farmers, homemakers, dentists—and that the purpose of their visit was, in part, charitable: to help raise money to support the Union of Italian Parents against infant cancer.[65]

Journalists interviewed Mormon Church leaders in Italy to obtain information, and the communist newspaper L’Unità sent a reporter to Utah to provide firsthand observations about Mormon life. These and other journalists debunked popular myths about Mormons—for example, the iconography of Hollywood films presents a “falsified image”—and accurately discussed the church’s practice and abolition of polygamy, genealogical and microfilming program, growing international profile, and “colossal” humanitarian effort to care for the poor locally and in underdeveloped countries.[66]

Italian music critics, while keenly aware of the choir’s blending of art and proselytizing (“301 Preachers,” according to one headline),[67] generally lauded the technical and artistic excellence of the choir’s performances and “the marvels of the musical life of the Mormons” that is appreciated worldwide.[68] Some, however, found fault with its oddly mixed repertoire (classical, sacred, and American traditional), musical interpretations, and well-intended but unevenly executed efforts to sing in Italian.[69] One journalist captured the ambivalent sense of appreciation and curiosity that characterized press reaction to the choir: “They come from another musical civilization, remote and mysterious to us, that appears deeply nourished by a moral dimension different and a thousand oceans away from ours.”[70]

LDS Church leaders meet with President Oscar Luigi Scalfaro at the Quirinale Palace in Rome, 1998. From left to right, Guiseppe Pasta, national director of public affairs; Raimondo Castellani, president of the Europe West Area; President Scalfaro, and Franco Messina, secretary to Scalfaro. Courtesy of LDS Public Affairs, Italy.

LDS Church leaders meet with President Oscar Luigi Scalfaro at the Quirinale Palace in Rome, 1998. From left to right, Guiseppe Pasta, national director of public affairs; Raimondo Castellani, president of the Europe West Area; President Scalfaro, and Franco Messina, secretary to Scalfaro. Courtesy of LDS Public Affairs, Italy.

From the church’s vantage point, the choir’s tour in Italy was a resounding success, achieving its goals of making friends with the people and increasing awareness and acceptance of Mormonism. While it is difficult to gauge precisely the effect of the choir’s performances and related press coverage on missionary work, church leaders in Europe predicted that they would have a lasting impact.[71] The choir’s influence did bear fruit subsequently in both obvious and subtle ways. Only a few months after the tour, Mormon leaders were hosted at the Quirinale Palace in Rome by Italian President Oscar Luigi Scalfaro. The meeting was arranged by Leone J. Flosi, president of the Rome Mission, and an adviser to Scalfaro who had attended the choir performance and VIP reception. Scalfaro—who had helped the church attain Ente Patrimoniale legal status in 1993—expressed his admiration for the church’s support of families and “showed every courtesy and helpful concern for the Church’s growth” in Italy.[72] These relationships with high-ranking Italian politicians also proved beneficial in the following decade as the church sought to conclude agreements for legal recognition and construction of a temple.

The church’s public affairs efforts yielded some positive results. Italian media began to consult more regularly scholarly material and information provided by Mormon public relations officials rather than relying solely on anti-Mormon, or at least badly informed, authors, as had been the case during most of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Balanced descriptions of Latter-day Saint temple work for the dead, its genealogical program, and the Church Family History Museum appeared in the Italian press.[73] In addition, more Italian journalists, scholars, politicians, business associates, and students visited Utah or, more importantly, encountered and interviewed Mormons in Italy. Much of this interaction was stimulated by the 2002 Winter Olympics in Utah and the sister-city relationship between Salt Lake City and Turin, host of the 2006 games.[74]

Studies exploring the impact of media and technology on religious change demonstrate that religious leaders “who worked out of their tradition to express their faith through innovative ways and means, idioms and technologies accessible and adapted to the times in which they lived” tend to be most successful in the religious marketplace.[75] The Mormon Church adopted emerging technologies to propagate its message quite effectively; however, its use of Internet in proselytizing, at least in Italy, lagged uncharacteristically behind the technology curve with damaging results for converts and investigators. Studies have found a strong correlation, if not causation, between internet use and religious disaffiliation.[76] Corroborating these findings, church leaders and missionaries in Italy reported, and participant observation confirmed, that the easy availability of anti-Mormon websites and the surprising dearth of Mormon-sponsored websites negatively impacted conversion and retention rates. In the Internet age, members and investigators commonly sought information about the church online, and many became disaffected with Mormonism when they were unable to find satisfactory responses to controversial issues about LDS history, doctrine, and practices.

However, one must not overstate the case about the role of media in Mormon missionary outreach, since recent studies by Italian scholars have cautioned against overestimating the impact that media actually exerts on public opinion and on the decisions that spiritual seekers make in Italy’s religious economy.[77]

The Grassroots Strategy: Community, Interfaith, and Humanitarian Outreach

While less visible than “bright light” media events, grassroots initiatives undertaken by Italian public affairs officials to promote interfaith dialogue, strengthen communities, and contribute in positive ways to Italian civic life were arguably more effective in the long term in helping the church emerge from obscurity. Public affairs reports and mission histories between 2003 and 2010 provide a snapshot of the variety of civic activities in which church members were regularly involved with fellow citizens in communities throughout Italy.

Mormons engaged in interfaith and civic activities, often sponsored by community organizations but sometimes by the church itself, to foster dialogue and cooperation.[78] These included joint Christmas concerts and celebrations with the evangelical church adjacent to the Mormon chapel in Catania, poetry recitals, musical performances, and conferences on contemporary topics (“The Modern Woman” one year) in Siracusa; an interfaith symposium on new religions in Salerno; a ceremony in Trieste to commemorate victims of Nazism; and a silent torchlight procession in Verona in memory of schoolchildren massacred in a terrorist attack in Beslan, Russia. On the eve of the Iraq War—a time of interreligious tension in Italy—representatives of nine religions, including Mormons, met in Verona to express a strong message of unity and mutual esteem, to pray together, and to cooperate in charitable works. Mormon youth of the Verona Ward held an interethnic dinner to promote trust and respect that was attended by 410 people. The church’s policy of granting open access to its approximately fifty genealogical centers located in chapels across Italy also brought heightened visibility for the Mormon community. According to the regional manager of FamilySearch in Italy, a high percentage of Italians who have frequented the centers to receive training and to conduct family research have been non-members who deeply appreciate this public service.[79]

In the field of humanitarian relief, Mormon congregations often teamed with other faith communities and municipal organizations to respond to natural disasters and other emergencies. In Como, Mormon musicians presented a classical music concert to raise money for a local charitable organization, SINDAH, which was building a maternity hospital in Senegal, and Mormon participation in an interfaith musical event in Verona helped raise almost five thousand euros to support tsunami victims at a children’s home in Thailand. The mayor of Verona awarded several religious groups, including The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, the “Premio Bontà” [Prize for Kindness] for raising funds to aid children in Kabul, Afghanistan, injured by land mines. Dozens of Mormon volunteers provided emergency aid after the L’Aquila earthquake in 2009 when nearly three hundred people were killed, assisting in the construction of tent camps for the thousands left homeless and providing materials and supplies for the ongoing relief effort. Later, 250 wheelchairs were donated to officials in Rome to help the disabled.[80]

The Mormon Helping Hands program, instituted in Italy in 2005, mobilized Church members to “support and improve communities” by sponsoring service projects in partnership with local government and nonprofit organizations.[81] Wearing distinctive vests and shirts, Mormon volunteers contributed significant time and manpower to community-level projects. For example, a national day of service sponsored by the Mormon Church in September 2005 included improving hiking trails for a Foster Children’s Association in Como; helping disabled children at the Il Giglio Institute in Trieste to assemble products for a fundraising campaign; repainting an elementary school in Catania; and cleaning up a forest on the Tirso River in central Sardinia, the Cavour public gardens in Turin, and a five hundred-meter-long section of a canal in downtown Terni. Another common Helping Hands project in Mormon congregations was conducting publicity campaigns and donating blood in support of local blood banks. These activities were generally carried out in collaboration with the mayor’s office, environmental groups, and service organizations such as the Lion’s Club.

On 1 February 2003, the two Mormon wards in Verona organized an interfaith dinner attended by more than 400 guests form various faiths including Muslims, Jews, Catholics, Buddhists and Mormons. The stated purpose of the event was "to go beyond tolerance and respect for diverse religious faiths and try to be friends." The youth of the wards served dinner to the guests. Courtesy of LDS Public Affairs, Italy.

On 1 February 2003, the two Mormon wards in Verona organized an interfaith dinner attended by more than 400 guests form various faiths including Muslims, Jews, Catholics, Buddhists and Mormons. The stated purpose of the event was "to go beyond tolerance and respect for diverse religious faiths and try to be friends." The youth of the wards served dinner to the guests. Courtesy of LDS Public Affairs, Italy.

The public affairs portrait would be incomplete without mentioning the systematic effort to cultivate positive relations with government officials at the local, regional, and national levels and to become better integrated in Italian political life. Regular “courtesy meetings” and “information dinners” were organized to allow Church leaders to meet government officials and journalists face-to-face, talk about church beliefs and community service programs, and dispel myths about Mormonism. Between 2003 and 2005, for example, local church leaders met with the prefect of Venice province and the governor of Turin region, and journalists in attendance wrote positive articles about the encounters. Several meetings were held with officials of the Turin Organizing Committee (TOROC) for the 2006 Winter Olympics to coordinate Mormon participation in volunteer and interfaith work. A church member working in the secretariat of a political party in Rome introduced Mormon officials to several influential Italian senators who promised to help the church in its campaign to attain legal recognition. To the same end, two courtesy visits were made to high-ranking officials in the Prime Minister’s office in Palazzo Chigi in Rome.

Gradually, if imperceptibly, this behind-the-scenes engagement in the civic life of the nation began to pay dividends as relationships with government officials and religious communities produced greater familiarity and mutual respect. Examples of changing attitudes and growing acceptance became more commonplace. After an information dinner in Pordenone, a city official complimented the church for the behavior of its members, noting also that Mormon missionaries have a reputation for being “well-mannered and not aggressive” in their proselytizing efforts.[82] At a special ceremony, the LDS branch in Mistretta, Sicily, was honored by the mayor, the city council, and many of the city residents. The mayor stated that the presence and good example of the Mormons in Mistretta “is important for the natives of this city.” He commended the members and missionaries for their service in local social organizations, such as rest homes for the elderly, which benefit others.[83]

The Helping Hands program, instituted in Italy in 2005, engaged Latter-day Saints in community and humanitarian service in cities across the country. The goodwill and relationships fostered by these kinds of grassroots activites proved to be pivotal in the church's efforts to achieve legal recognition from the Italian government. In these photos, LDS volunteers participate in helping clean the Cavour Gardens and the streets of the San Salcario neighborhood in Turin in September 2005. Courtesy of LDS Public Affairs, Italy.

The Helping Hands program, instituted in Italy in 2005, engaged Latter-day Saints in community and humanitarian service in cities across the country. The goodwill and relationships fostered by these kinds of grassroots activites proved to be pivotal in the church's efforts to achieve legal recognition from the Italian government. In these photos, LDS volunteers participate in helping clean the Cavour Gardens and the streets of the San Salcario neighborhood in Turin in September 2005. Courtesy of LDS Public Affairs, Italy.

Mormons, of course, were by no means the only faith group involved in community improvement and humanitarian outreach: during this time period associazionismo—voluntary work to promote solidarity, well-being, and pluralism—became “one of the most vivid elements of the new civil society” in Italy and Europe in general.[84] The point to be underscored here is that the Mormons’ embrace of grassroots community activism, emphasizing service in addition to proselytizing and finding common cause with neighbors more than organizing grand spectacles, was a pivotal development in contemporary Mormon history in Italy. While media-focused events produced some positive results, stereotypes about Mormons continued to persist in society, and Italians in general remained largely ignorant about the beliefs of Latter-day Saints.[85] But the Church’s ongoing engagement in interreligious cooperation and humanitarian outreach—year in and year out, over several decades, in nearly one hundred cities throughout Italy—slowly produced a reservoir of good will and political support for the Mormon community.

Catholic-Mormon Relations in Italy and in the United States

Relations between Catholics and Mormons, which were problematic throughout most of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, remain problematic.[86] Donald Westbrook noted that as of 2012 the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops “has not commenced a substantive and ongoing dialogue with the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.” Furthermore, the Vatican’s Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith issued a statement in 2001 in which “Mormon baptisms were declared invalid” and in 2008 directed “Catholic dioceses worldwide not to provide records to the Genealogical Society of Utah, because of doctrinal disagreement over the practice of baptizing deceased Catholics in temples.”[87] Furthermore, Pope John Paul II was very critical of new religions (including Mormonism) that he believed took advantage of the disorientation of immigrants, particularly in Latin America. Jorge Mario Bergoglio (while still a Cardinal in Argentina) made similar statements, and as Pope Francis is unlikely to change his opinion on this issue.[88]

Nevertheless, humanitarian outreach and interfaith collaboration in the political arena contributed to improving relations between Catholics and Mormons. Similar religious orientations of the two religions (focus on traditional values, resistance to ordaining women to the priesthood, upholding Church authority and teachings) and social and political agendas (opposition to same-sex marriage, abortion, pornography, state interference with religious practices, and collaboration in disaster and poverty relief efforts) made them natural allies in the public arena. This led to cooperation on moral issues between the Vatican and LDS authorities both in Italy and in the U.S.

Meetings between Latter-day Saint and Vatican officials began in the 1970s, but interaction and collaboration accelerated in the 1990s.[89] Michele Straniero (the same journalist who attended Harold B. Lee’s press conference in 1972) noted in 1992 that Mormons were “officially” invited to participate, with other religious groups, in an ecumenical alliance against pornography which was organized by the Vatican. Straniero noted that this invitation and subsequent participation were unique because of Mormonism’s traditional exegesis concerning Catholic history.[90] When Gordon B. Hinckley of the First Presidency visited Rome in 1992, he was “warmly received at the Vatican archives when he presented a set of the Encyclopedia of Mormonism to Leonard Boyle, prefect of the Vatican Library.[91] In December 1993, Vatican officials authorized a choir of Mormon missionaries to perform at a Christmas mass in St. Peter’s Basilica.[92]

The thawing relationship between Catholics and Mormons is evident in the wary but respectful tone of discourse during a series of meetings in 1995–96. Mormon officials met several times with Cardinal Edward Cassidy, President of the Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity, at the Vatican to discuss cooperation on antipornography legislation in Australia (the cardinal’s home country) and plans for the upcoming Mormon Tabernacle Choir visit to Italy. It was agreed that “irreconcilable doctrinal differences” should not preclude “working together for common moral and social” causes. While Catholic authorities were “not ready at this time” to have the choir perform at the Vatican, they wanted to be “helpful with arrangements to perform elsewhere in Rome.” (Two years later the choir performed at the National Academy of Saint Cecilia, one of the oldest musical institutions in Italy with close ties to the Catholic Church.) For their part, Mormon leaders were not willing “to officially invite high Catholic authorities to Church headquarters” but were “receptive to developing a closer relationship” on an informal basis.[93]

As the Church’s legal recognition and temple construction efforts gathered momentum, mutually beneficial contacts between Mormon and Catholic officials took place on a regular basis. Newspapers featured stories about Mormon collaboration with Catholics in humanitarian programs for immigrants, refugees, and natural disaster victims[94] and in social and political causes such as supporting Proposition 8 (banning same-sex marriage) in California and promoting religious freedom.[95] In Australia, the Mormon Church presented its erstwhile Vatican ally, Cardinal Cassidy, with an award “for heroic efforts to bring better understanding to the people of the world” through his advocacy of ecumenism and interreligious dialogue.[96] Mormon leaders’ concern for maintaining positive relations with the Catholic Church was evident in President Gordon B. Hinckley’s impromptu expression of condolences during general conference on learning of Pope John Paul II’s death in 2005. Hinckley lauded John Paul as “an extraordinary man of faith, vision and intellect, whose courageous actions have touched the world in ways that will be felt for generations to come.”[97] Church leaders decided to postpone publicity about the organization of the new Rome stake (which occurred one month later, in May) to avoid any appearance of celebration and to show respect for Catholic sensibilities during the mourning period after the Pontiff’s passing.

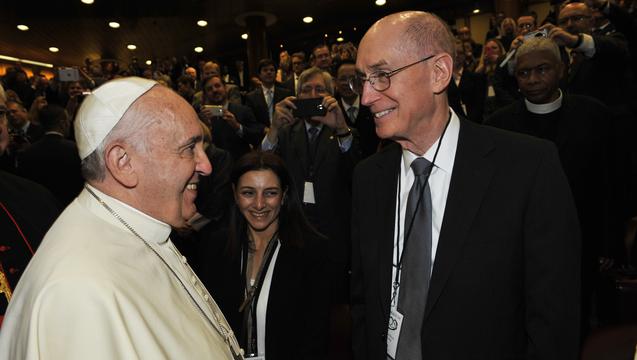

Pope Francis greets Elder Henry B. Eyring of the LDS Church's First Presidency on 17 November 2014 at a Vatican-spondored conference on marriage held in Rome. Courtesy of Salt Lake Tribune and the LDS Church

Pope Francis greets Elder Henry B. Eyring of the LDS Church's First Presidency on 17 November 2014 at a Vatican-spondored conference on marriage held in Rome. Courtesy of Salt Lake Tribune and the LDS Church

Such gestures from LDS leaders were not lost on Catholic officials in the US cardinal William Joseph Levada, who succeeded Pope Benedict as prefect of the congregation for the doctrine of the faith, visited Salt Lake City in August 2009 during the centennial celebration of the Cathedral of the Madeleine. Levada had previously served as the archbishop of San Francisco and was familiar with the friendly relations between Catholic and Mormon officials in Utah. During the ceremonies, Bishop John C. Wester of the Diocese of Salt Lake City and other Catholic speakers expressed appreciation for support from local government officials and from LDS Church leaders, including Elder Russell Ballard, for participating in the celebration.[98]

This encounter may have led to another meeting in Salt Lake City six months later (February 2010) when the First Presidency hosted Cardinal Francis George, archbishop of Chicago and president of the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops. Along with Bishop Wester, Cardinal George visited Mormon Church headquarters and gave a speech at Brigham Young University in which he “praised the LDS Church for its efforts alongside the Catholic Church to alleviate suffering of the poor, combat pornography, define marriage as the union of one man and one woman, and protect the rights of the unborn.” He expressed his personal gratitude for the fact that “after 180 years of living mostly apart from one another, Catholics and Latter-day Saints have begun to see each other as trustworthy partners in defense of shared moral principles.”[99]

Later in 2010 Ballard met with Levada at the Vatican, and in 2014 Elder Henry B. Eyring of the First Presidency encountered Pope Francis and had his picture taken with him in Rome during a Vatican-sponsored, interfaith colloquium on marriage and family life.[100] These events demonstrate that the LDS Church has worked hard to establish good relations at the highest levels of the Catholic hierarchy. [101]

This chapter has explored how external forces in Italy and internal factors in the Church influenced Mormon evangelization. Evolving social attitudes about institutionalized religion, a period of economic prosperity, and dramatic changes in the political landscape were contextual factors that accompanied a slowdown in overall growth. An unparalleled influx of immigrant converts interjected cultural, racial, and class diversity that both strengthened and challenged the communal life of the Saints. This was accompanied by a maturation of Church organization and leadership and increasing—though still relatively limited—recognition and consolidation of Mormonism’s place in Italy’s public life. New programs initiated by the Church to enhance its image, promote respect and trust at the community level through humanitarian and civic participation, and establish more positive relations with other faith communities, especially the Catholic Church, proved instrumental in this regard. These interfaith and interpersonal relationships at the local, regional, and international levels of public life would eventually prove crucial—especially for a comparatively small, recently imported religion like Mormonism—in achieving two historic milestones: legal recognition by the Italian State and construction of a new temple in Rome.

Notes

[1] Franco Garelli, Religione e Chiesa in Italia (Bologna: il Mulino, 1991), 34–35.

[2] Massimo Introvigne et al, Enciclopedia delle Religioni in Italia (Torino: Centro Studi sulle Nuove Religioni [CESNUR], 2001), 6; Garelli, Religione e Chiesa in Italia, 34–35.

[3] Salvatore Abbruzzese, “Religion and the Post-War Generation in Italy,” in The Post-War Generation and Establishment Religion: Cross-Cultural Perspectives, ed. Wade Clark Roof, Jackson W. Carroll, and David A. Roozen (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1995), 218, 220.

[4] In the US, for example,

“‘Nones’ on the Rise,” Pew Research Center’s Religion and Public Life Project, 9 October 2012, http://

[5] Introvigne et al., Enciclopedia delle Religioni in Italia (2001), 7–8; (2013), 7,18-19. Introvigne estimates that “a realistic figure of Italians attending religious services (including non-Catholic) is around 20 percent.” Introvigne, e-mail to James Toronto, 24 September 2013. For detailed statistics on religiosity in Italy and Europe in general, see Loek Halman and Veerle Draulans, “Religious Beliefs and Practices in Contemporary Europe,” in European Values at the Turn of the Millennium, ed. Wil Arts and Loek Halman (Leiden: Brill, 2004), 283–316, and other volumes in the European Values Studies series.

[6] Massimo Introvigne, “‘Praise God and Pay the Tax:’ The Italian Religious Economy—An Assessment,” paper presented at the Institute of World Religions, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, Beijing, China, 12 March 2002. Available at www.cesnur.org.

[7] Paolo Naso, Il Mosaico della Fede: Le Religioni degli Italiani (Milano: Baldini and Catoldi, 2000), 9, 21–22. On Italy’s emerging religious pluralism, see also Luigi Berzano, ed., Forme del pluralismo religioso (Torino: il Segnalibro, 1997), and Franco Garelli et al, Un singolare pluralismo: indagine sul pluralismo morale e religioso degli italiani (Bologna: il Mulino, 2003).

[8] Garelli, Religione e Chiesa in Italia, 13–15, 40–41.

[9] Garelli, Religione e Chiesa in Italia, 47, 66–67.

[10] Marco Gervasoni, Storia d’Italia degli anni ottanta (Venezia: Marsilio, 2010), 66; Giuseppe Mammarella, L’Italia Contemporanea, 1943–1998, 527–29.

[11] Marino Livolsi, ed., L’Italia che Cambia (Scandicci: La Nuova Italia, 1993), 4.

[12] Italy Padova Mission, manuscript history and historical reports, June, July 1981 and June 1982, LR 15015-2; Italy South Mission, manuscript history and historical reports, 8 April 1982, and 3, 16, 30 December 1982, LR 414222, Church History Library.

[13] This purge was apparently not limited to Italy. Decoo confirmed that at this time in some other countries in Europe, including the Netherlands and Belgium, church leaders also carried out mass excommunications of uninterested members. E-mail to James Toronto, 25 August 2014. For information on a similar movement in the 1960s, see Michael D. Quinn, “I-Thou vs. I-It Conversions: The Mormon ‘Baseball Baptism’ Era,” Sunstone (December 1993), 38–40.

[14] Italy Catania Mission, manuscript history and historical reports, March 1984, LR 16847, Church History Library.

[15] Italy Rome Mission, manuscript history and historical reports, 15 November 1977, LR 4142-2, and 23 January, 20 March, and 12 May 1996, LR 4142-3, Church History Library.

[16] Diana Eck, A New Religious America: How a “Christian Country” Has Become the World’s Most Religiously Diverse Nation (New York: HarperCollins, 2001), 4.

[17] Paul Ginsborg, Italy and Its Discontents: Family, Civil Society, State, 1980–2001 (London: Penguin, 2001), 62.

[18] L. Mauri and G. A. Micheli, “Flussi immigratori in Italia: una scheda documentaria,” in Mauri and Micheli, Le regole del gioco (Milan, 1992), 213nn., and L’Istituto nazionale di statistica (ISTAT), La presenza straniera in Italia, Rome, 1993, 33nn. in Ginsborg, Italy and Its Discontents, 380.

[19] Fabio Amato, ed., Atlante dell’immigrazione in Italia (Roma: Carocci, 2008), 23–24, and tables 3 and 4, 128–29.

[20] Asher Colombo and Giuseppe Sciortino, Gli immigrati in Italia (Bologna: Mulino, 2004), 15.

[21] Ginsborg, Italy and Its Discontents, 63–64.

[22] Giovanna Zincone, “A Model of ‘Reasonable Integration’: Summary of the First Report on the Integration of Immigrants in Italy,” International Migration Review 34, no. 3 (Fall 2000): 956–68. The reference for the complete Italian report is Primo rapporto sull’integrazione degli immigrati in Italia (Bologna: Società Editrice il Mulino, 2000).

[23] Colombo and Sciortino, Gli immigrati in Italia, 123.

[24] “Sondaggio Ap-Ipsos: per gli italiani gli immigrati sono gran lavoratori.” 6 giugno 2006, http://

[25] Interviews with various Mormon Church leaders. Notes and e-mails in James Toronto’s possession.

[26] Data from interview notes in James Toronto’s possession.

[27] See, for example, Silvio Lanaro, Storia dell’Italia repubblicana: L’economia, la politica, la cultura, la società del dopoguerra agli anni ’90 (Venezia: Marsilio, 1992), 177–90, 245–48; Guido Crainz, L’Italia repubblicana (Firenze: Giunti, 2000), 101–4; Geoff Andrews, Not a Normal Country: Italy After Berlusconi (London: Pluto Press, 2005), 107–9; and Ginsborg, A History of Contemporary Italy, 122–29.

[28] Jiro Numano, “Mormonism in Modern Japan,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought, vol. 29, no. 1 (Spring 1996), 226; and Jörg Dittberner,” One Hundred Eighteen Years of Attitude: The History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in the Free and Hanseatic City of Bremen,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 36, no. 1 (Spring 2003), 52.

[29] C. Gary Lobb, “Mormon Membership Trends in Europe among People of Color: Present and Future Assessment,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 33, no. 4 (Winter 2000): 63–67.

[30] “Policies Concerning Work with Refugees and Asylum Seekers,” Europe Area Presidency, letter to priesthood leaders, 27 June 1990. Cited in Wilfried Decoo, “Issues in Writing European History and in Building the Church in Europe,” Journal of Mormon History 23, no. 1 (Spring 1997): 161.

[31] Decoo, “Issues in Writing European History,” 162.

[32] Decoo, “Issues in Writing European History,” 160–61.

[33] Interview with Maurizio Bellomo, 23 June 2011, Vercelli, Italy.

[34] Deseret Morning News 2013 Church Almanac (Salt Lake City: Deseret News, 2013); Sarah Jane Weaver, “Elder Ballard, Elder Oaks Organize Stakes in Rome and Paris,” Church News, 2 October 2013, https://

[35] Philip Jenkins, The Next Christendom: The Coming of Global Christianity (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002), 2–3. Consistent with Jenkins’ research, this demographic shift in the Mormon Church stems primarily from growth in Africa and Latin America, not Europe.

[36] Jay M. Todd, “More Members Now outside U.S. Than inside U.S.,” Ensign, March 1996, 76.

[37] Doctrine and Covenants 1:30.

[38] For historical background on Catholic resistance to the Protestant missionary “threat” in Italy and its impact on Italian-US political relations, see Roy Palmer Domenico, “‘For the Cause of Christ Here in Italy’: America’s Protestant Challenge in Italy and the Cultural Ambiguity of the Cold War,” Diplomatic History 29, no. 4 (2005): 625–54.

[39] Charles Richards, The New Italians (London: Penguin Books, 1995), 126.

[40] Corriere della Sera, 7 February 1985, 4. The pope was quoted in 1990 as saying that there are false prophets in new religions which take particular advantage of the disorientation of immigrants (particularly in Latin America). No particular churches were identified, but proselytizing remained a very sensitive subject among the Catholic hierarchy. See John Paul II, “Una sapiente azione pastorale per salvaguadare i migranti del proselitismo religioso,” L’Osservatore Romano, 30 August 1990, 6; and “La Chiesa é chiamata ad illuminare secondo il vangelo tutti i campi della vita dell’uomo e della societá,” L’Osservatore Romano, 17 May 1990, 22–23.

[41] See, John Saliba, “Mormonism in the Twenty-first Century,” Studia Missionalia 41 (1992): 49–67; and Salt Lake Tribune, 20 November 1993, C2.

[42] For a comprehensive bibliography concerning the image of Mormonism in Italy, particularly during the nineteenth century, see Michael W. Homer, “The Church’s Image in Italy from the 1840s to 1946: A Bibliographic Essay,” BYU Studies 31, no. 2 (Spring 1991): 83–114; and On the Way to Somewhere Else: European Sojourners in the Mormon West, 1834–1930 (Spokane, WA: Arthur H. Clark, 2006).

[43] Pietro Saja, “Aleister Crowley e il suo soggiorno a Cefalù,” Il Corrierre della Madonie (October 1985), 6. For a description of Crowley’s residence in Cefalù, see John Symonds, The Great Beast, The Life of Aleister Crowley (London: Rider and Company, 1951), 149–215. For information concerning Crowley’s attitude toward Mormonism see Massimo Introvigne, “The Beast and the Prophet: Aleister Crowley’s Fascination for Joseph Smith,” unpublished paper delivered at the Mormon History Association conference, Claremont, California, 31 May 1991.

[44] “L’Animismo e le sette minori,” Oggi 15 (1988): 188–89; and Robert Walsh, “Mormoni variazioni sullo stesso tema,” La Presenza Cristiana 36 (10 November 1988): 27–28.

[45] On 26 July 1991, one of Italy’s largest circulating newspapers published an article about Alex Joseph in its magazine supplement, which claimed that “the Mormons in Utah—but not all—are among the fortunate religions” that allow men to have more than one wife. See “L’Harem di Papa Joseph,” Il Venerdì di Repubblica 181 (26 July 1991): 39–42. Occasionally newspaper articles appeared which made the distinction between fundamentalist (excommunicated) “Mormons” and their nineteenth-century counterparts. See Giuseppe Josca, “Il sindaco dà l’esempio: 5 moglie e 60 figli,” Corrierre della Sera, 25 September 1986, 3.

[46] Corriere della Sera, 6 February 1993, 15.

[47] Luigi Berzano and Massimo Introvigne, La sfida infinita: La nuova religiosità nella Sicilia centrale (Caltanissetta-Rome: Salvatore Sciascia Editore, 1994), 198.