From the Great Basin Kingdom to the Kingdom of Sardinia, 1849-51

James A. Toronto, Eric R Dursteler, and Michael W. Homer, "From the Great Basin Kingdom to the Kingdom of Sardinia, 1849-51," in Mormons in the Piazza: History of the Latter-Day Saints in Italy, James A. Toronto, Eric R. Dursteler, and Michael W. Homer (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2017), 1-44.

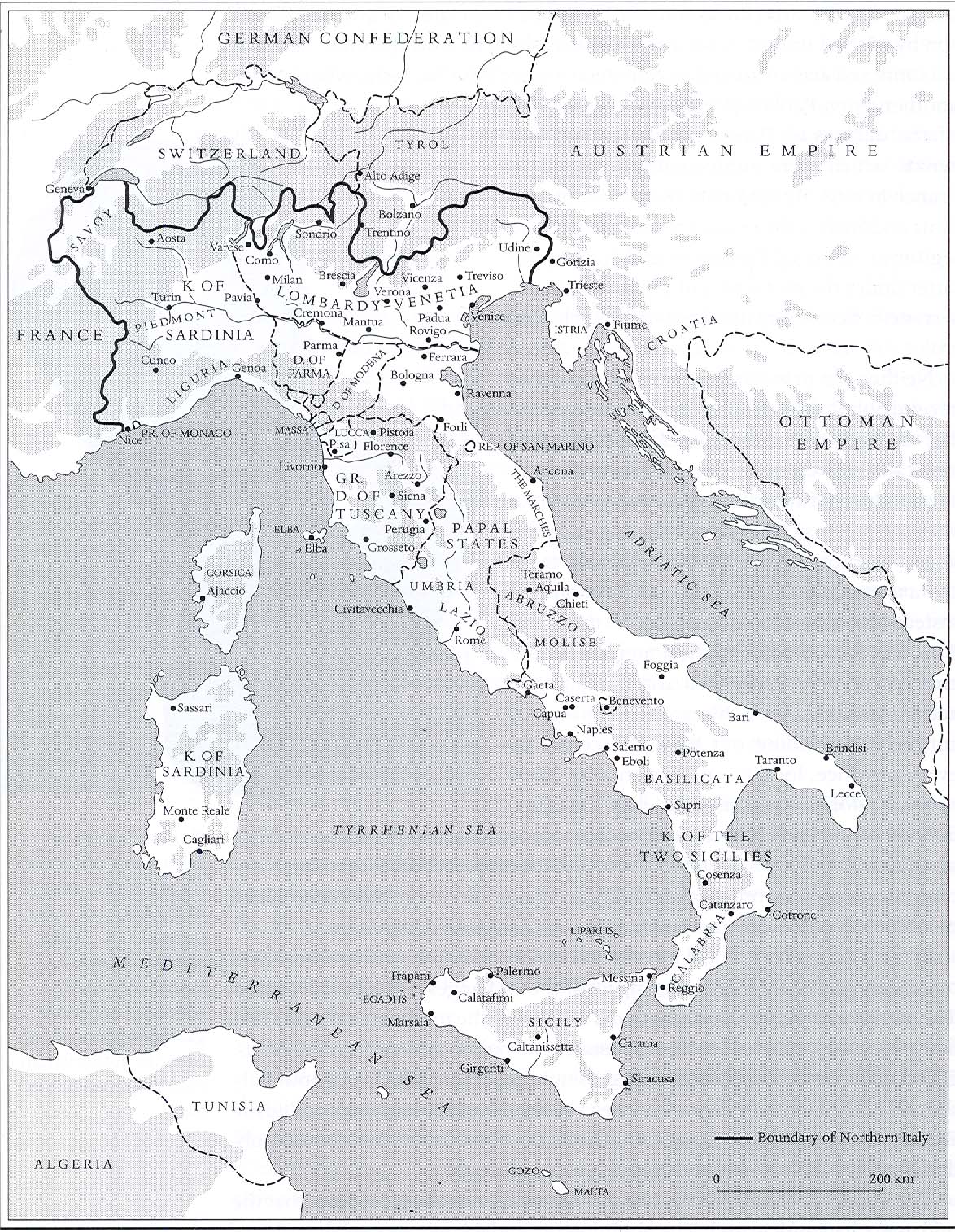

Italy in 1815. Reprinted form George Homes, ed., The Oxford History of Italy (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997), 182.

Italy in 1815. Reprinted form George Homes, ed., The Oxford History of Italy (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997), 182.

Lorenzo Snow opened the Italian Mission in the Kingdom of Sardinia in 1850 because he sensed that the Waldensians—a small group of Protestants with settlements in Piedmont who many believed had ancient origins reaching back to the primitive church—might be receptive to Mormon proselytizing.[1] Elder Snow was attracted to the Waldensians after the “liberal springtime” which swept across Europe and the Italian peninsula in 1848 and brought historic changes affecting personal liberties and freedom of conscience. Snow organized a proselytizing mission in the Waldensian Valleys and in Turin that soon attracted the attention of Protestants, Catholics, and secular authorities. Thereafter, the Mormon mission became an important ingredient in the tense debates concerning the boundaries between church and state.

Winds of Change in Piedmont

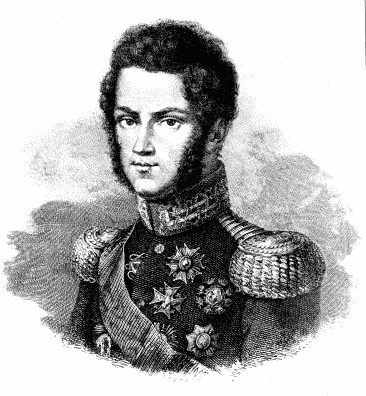

On the evening of 17 February 1848, two couriers on horseback galloped into the mountain town of Torre Pellice bearing momentous news from Turin, the capital of the Kingdom of Sardinia in northwest Italy.[2] Earlier that day, King Carlo Alberto had issued an Edict of Emancipation granting equal rights to Jews and Waldensians, who for centuries had been persecuted for their religious beliefs, confined to ghettoes, prohibited from attending universities, and forbidden to practice a profession or purchase land. Now, under pressure from Italian liberals in the Sardinian government, the ban was lifted and all citizens would enjoy equal standing in civil and political liberties.

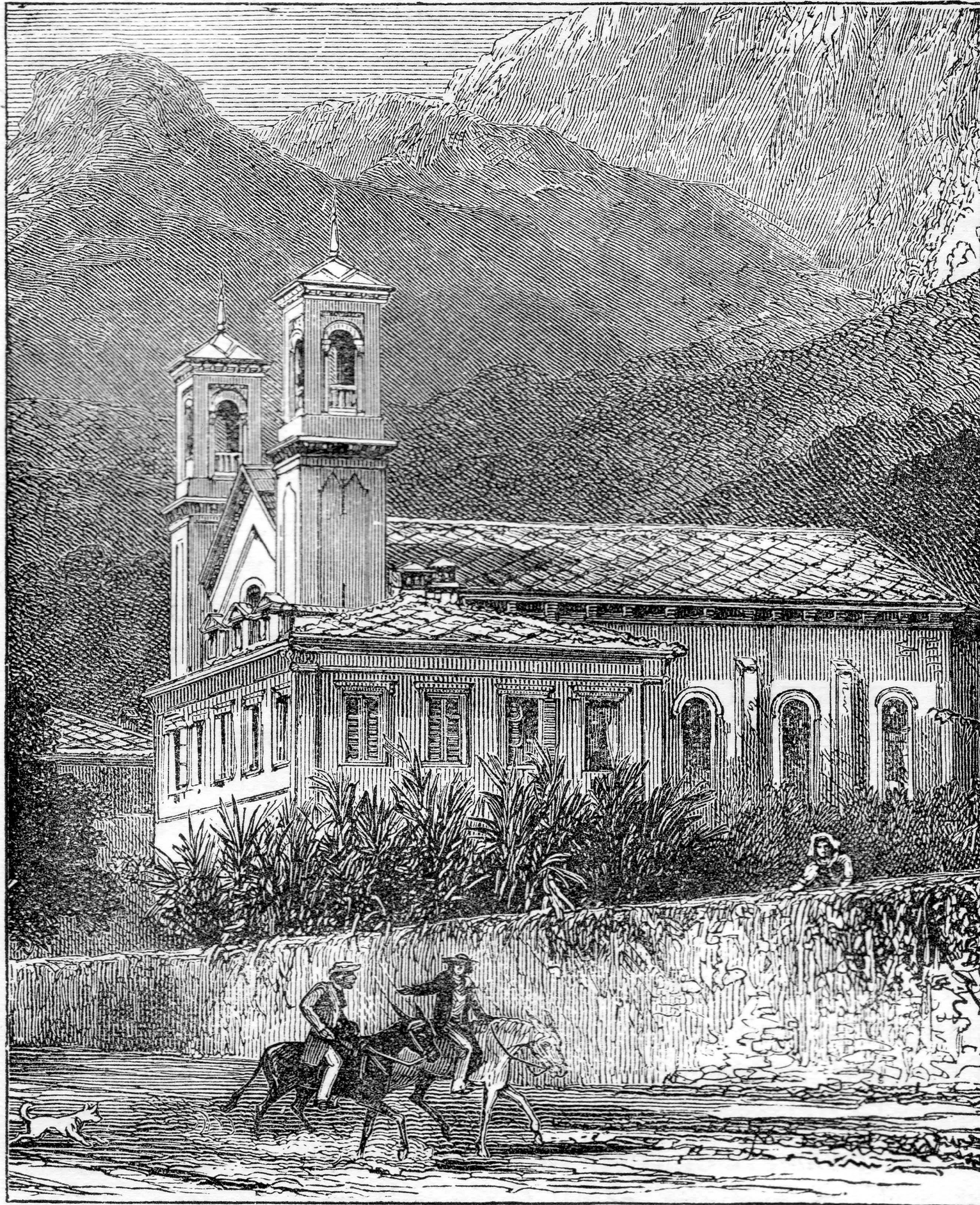

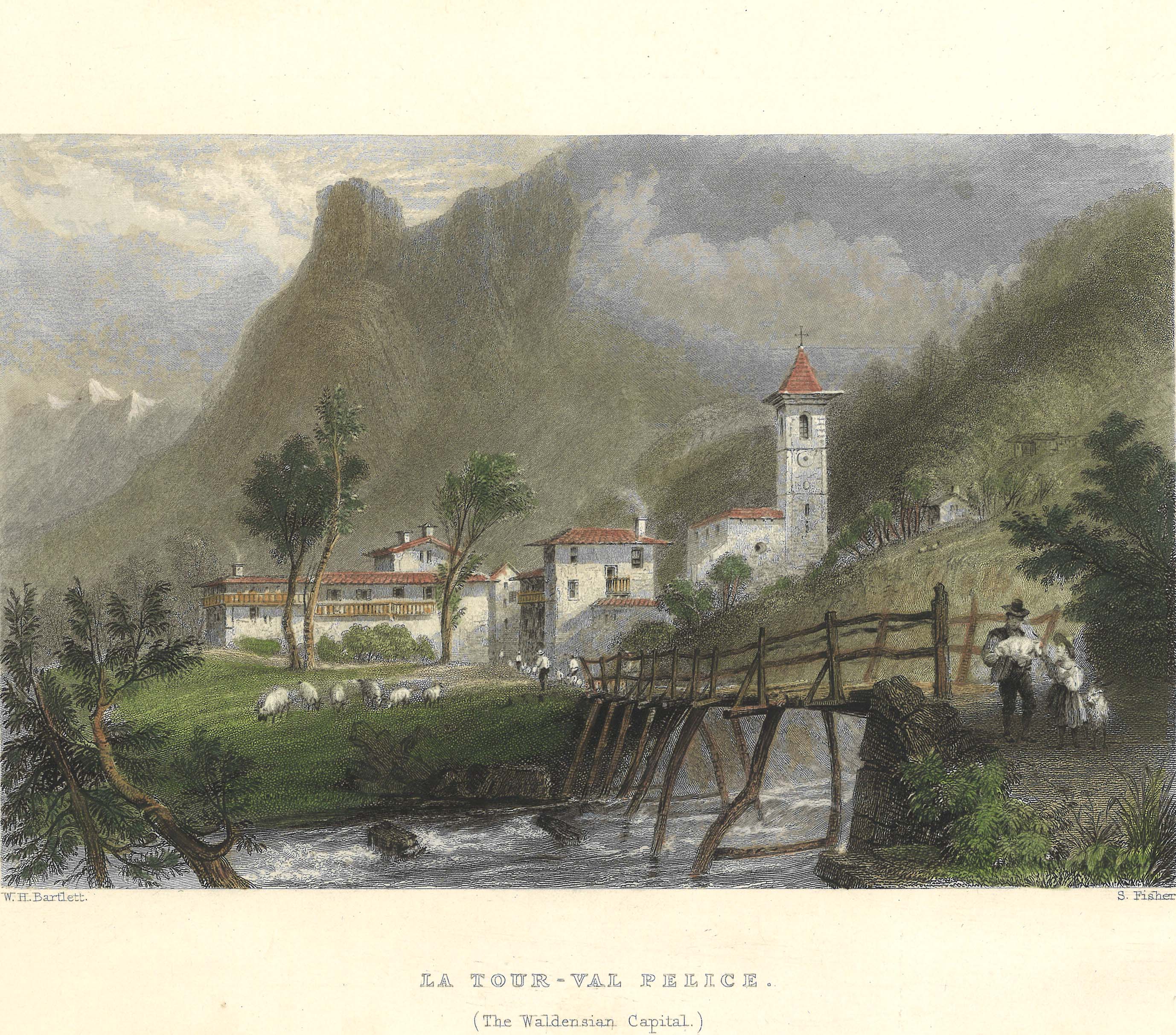

The news spread quickly from one alpine borgata (hamlet) to another until it reached every corner of the four Waldensian valleys: Val Pellice, Val Angrogna, Val Chisone, and Val Germanasca. Many people spontaneously assembled in their churches to sing hymns, offer prayers of gratitude, and give speeches praising the king. Torches were placed on windows and porches and traditional bonfires (called falò in the local dialect) lit on nearly every hilltop to celebrate the historic event. It was reported that more than one hundred such bonfires illuminated the majestic heights of Mount Castelluzzo and Mount Vandalino above Torre Pellice (also called La Tour at the time). In the new spirit of ecumenism, a festive banquet was served in the courtyard of the Hôtel de l’Ours with fifteen Catholic priests and more than three hundred local Waldensian dignitaries participating.

The Waldensian Temple Built in 1852 in Torre Pellice, with Mount Castelluzzo in the background. Reprinted from J. A. Wylie, History of the Waldenses, 4th ed. (London: Cassell & Company, 1889), 8.

The Waldensian Temple Built in 1852 in Torre Pellice, with Mount Castelluzzo in the background. Reprinted from J. A. Wylie, History of the Waldenses, 4th ed. (London: Cassell & Company, 1889), 8.

Thirteen-year-old Stephen Malan, who lived a few kilometers from Torre Pellice in Val Angrogna, described the ensuing celebrations as “the greatest demonstrations of joy, gladness, and thanksgiving that was ever beheld in those secluded valleys. . . . Firing of guns and mortars, gorgeous displays of military parades, and thousands of mottoes written upon the walls facing the streets of the towns, with every shade of fantastic lights for illumination: fireworks in full display, discharges of artillery that shook the earth. All things combined to make a nation’s festival, such as is not often witnessed, and which shall never be forgotten by the Waldenses.”[3]

Marie Cardon, a fourteen-year-old from Prarostino just over the hill from the Malans, reported that after the proclamation “the king prepared a grand feast for all the people in his kingdom or dominion, both rich and poor . . . which lasted three days and three nights.” She also recalled that “bells were ringing and great speeches were made in behalf of our people” and that her parents took advantage of their new freedom by moving from the mountains down into the plains of Piedmont, where economic opportunities were more abundant.[4]

The public rejoicings for the king’s edict were not confined to the Waldensian valleys. On Sunday, 27 February, an enormous festival was held in the capital city, Turin, to celebrate both the new edict as well as the promulgation of a more liberal constitution, called the Statuto, which would take effect on 4 March. The streets were festooned with tapestries, garlands, inscriptions, and banners. Many people wore the blue cockade[5] and sang songs of liberty and praise to Carlo Alberto. The crowds positioned themselves along the city streets, in windows, on balconies and rooftops, and even on the towers of the old castle to witness the grand parade of official delegations from every region of the kingdom—Liguria, Sardinia, Nice, Savoy, and the provinces of Piedmont. As the procession slowly wound its way toward Piazza Castello, where the king and queen and their retinue waited in front of the palace, bands played martial music and the crowds shouted “Hurrah for the emancipation of the Waldenses!” and “Long live liberty of conscience!” The Waldensian delegation, about six hundred strong, was given an honored place at the front of the procession carrying a blue banner with the inscription: “To Carlo Alberto from the grateful Waldenses.”

Cavalry and citizens of the Kingdom of Sardinia parade through the streets of Turin. Reprinted form C. Bossoli and R. M. Bryson, Torino, Cavalleria sarda [1859], Turin: Collezione Lucarelli. In Franco Paloscia, ed., I1 Piemonte dei grandi viaggiatori (Rome: Abete, 1991), 10.

Cavalry and citizens of the Kingdom of Sardinia parade through the streets of Turin. Reprinted form C. Bossoli and R. M. Bryson, Torino, Cavalleria sarda [1859], Turin: Collezione Lucarelli. In Franco Paloscia, ed., I1 Piemonte dei grandi viaggiatori (Rome: Abete, 1991), 10.

One Waldensian observer captured the day’s significance in these words: “An immense spectacle, grand, indescribable! Those who saw it have never forgotten it and never will. . . . Who could tell what emotion the six hundred [Waldensians] felt when, reaching the balcony of the Palace, they found themselves suddenly in the presence of the magnanimous Prince, who, breaking in sunder the chains of their ancient servitude, had called them and their children into the enjoyment of a new existence?”[6] Such was the spirit of the turbulent times in Italy, with 1848—the “annus mirabilis of revolution”—marking a historical and political watershed throughout Europe.[7]

The Choice of Italy as a Mission Field

Meanwhile, eight thousand miles away, the Mormon pioneers were barely settling into their new homes in the valley of the Great Salt Lake in the Rocky Mountains. They had arrived the previous July, when church leaders began making plans that would bring about significant social change in the fledgling community: sending missionaries to Continental Europe. On 29 April 1849, President Brigham Young told his counselors and the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles of his intention “to send brother Joseph Toronto to his native country (Italy) and with him someone to start the work of gathering from that nation.”[8] During general conference that October, Young followed through and called the first missionaries to begin preaching the gospel in Italy, France, and Scandinavia. Heber C. Kimball of the First Presidency gave an impassioned sermon setting out the theological premise for widening the scope of missionary work: “We are all of the same family; we have one God and one Savior, therefore the business interests everyone. . . . We want to feel for the welfare, not only of this people, but all of the inhabitants of the earth. . . . We want this people to take an interest with us in bearing off the Kingdom [to] all the nations of the earth. The time is come when some of the Twelve, and others of the Elders will have to go.”[9]

A motion was made that three members of the Quorum of Twelve Apostles lead new missions to Europe: Lorenzo Snow to Italy, accompanied by Joseph Toronto; Erastus Snow to Denmark, helped by Peter Hansen; and John Taylor to France, with Curtis Bolton. The motion carried unanimously, and less than two weeks later, on 19 October, a party of thirty-two, including the missionaries bound for Europe, gathered at the mouth of Emigration Canyon and departed for the journey east.

In some ways, the choice of Italy as one of the first non-English-speaking mission fields is surprising. Italy at the time was not yet a unified nation but a mosaic of kingdoms and duchies, and the progressive ideas of Enlightenment reformers that were bearing fruit in other European countries—notions of religious liberty, freedom of speech and of the press, universal education, and political pluralism—had not yet taken root. Piedmont, however, where the missionaries would begin their labors, was passing through a decisive period of political and social upheaval.

King Carlo Alberto, House of Savoy. Courtesy of Michael Homer, personal collection.

King Carlo Alberto, House of Savoy. Courtesy of Michael Homer, personal collection.

The documentary sources reveal a number of motives and strategies that help explain the unlikely choice of Italy as an early mission field. The first motive is reflected in Brigham Young’s 29 April comment concerning the doctrine of the election and gathering of Israel—viewed at that time, but less so today, as a core tenet of Latter-day Saint theology.[10] Young apparently felt, based at least in part on his close association with the Italian convert, Toronto, that Italy would be a fruitful field in which to harvest other souls possessing the blood of Israel. Thus his decision “to start the work of gathering from that nation” seemed a plausible one from a theological perspective.

The hope of finding many of the seed of Israel in Italy was one of the missionaries’ central motives as demonstrated by many references to this doctrine in their personal writings. Lorenzo Snow chose to begin missionary work in Italy among the Waldensians when he “felt assured that the Lord had directed us to a branch of the House of Israel,” and he expressed his confidence that the church would “increase and multiply, and continue its existence in Italy till that portion of Israel dwelling in these countries shall have heard and received the fullness of the Gospel.”[11] Apparently his strategy for opening new areas to missionary work was based in part on consideration of possible Israelite connections: “[Malta] will be an important field of labour not only for Italy, but also for Greece, where, according to ancient tradition, a branch of the House of Israel has long remained.”[12]

Jabez Woodard, who later joined Snow and Toronto, wrote in a letter to Snow: “I confess that when I found you laid upon me the solemn charge to gather Israel from among these nations, I felt the weight of the office, and at the same time new courage and new patience.”[13] A report on the East India Mission in the Millennial Star evinces the zeal of the early missionaries to gather Israel: “Thus are the glad tidings of salvation wending their way in the dark regions of the earth; the energy of the Elders of Israel is rapidly causing Zion’s glorious standard to be lifted up among the nations, whilst the Holy Spirit of God inspires the scattered sons and daughters of Israel to flee to the hope set before them.”[14]

George Keaton, another early missionary, spoke of his earnest expectation “to see the Church spread abroad until it has crushed, beneath its universal prevalence, everything that opposes, for the Lord will carry on His work until all Israel are saved.”[15] Finally, T. B. H. Stenhouse prayed that God would conduct Elder Woodard and the emigrating Italian saints “in peace and gladness to the Valleys of Ephraim.”[16] The imagery and rhetoric that permeate these early accounts indicate how deeply motivated church leaders and missionaries were to find the blood of Israel in Italy and bring them to Zion.

Italy’s prominent role in Europe’s religious and cultural history was a second important reason for the decision to make it one of the first European mission fields. Clearly, the prospect of proclaiming Mormonism in the birthplace of the Roman Empire, the Renaissance, and especially the Roman Catholic Church, was one that captivated church leaders and missionaries. Their views are typically Victorian in their romantic, idealized infatuation with Italy’s natural beauty and glorious past. Snow described sitting on a high mountain gazing at the valleys below: “Ancient and far-famed Italy, the scene of our mission, was spread out like a vision before our enchanted eyes.”[17] On other occasions he marveled at the scenery and monuments of Genoa: “Its palaces, numerous cathedrals, churches, high-built promenades, and antique buildings form altogether a very singular and magnificent appearance. At a little distance from the city, I have the fascinating scenery of Italy’s picturesque mountains. . . . My eyes are filled with tears while attempting to picture the glorious view. . . . The design and execution of these monuments of departed worth elicited our admiration. . . . Our minds were absorbed in the contemplation of the beauty and richness of art.”[18]

Alongside the sense of awe for Italy’s historical legacy, the missionaries also exhibited a spirit of indignation and sorrow for Italy’s contemporary status, continually lamenting what they perceived as the moral corruption, deep-rooted traditions, and religious indifference found among the Italians, and predicting a new and brighter day that the gospel would bring.[19] The missionaries often used pejorative terms such as “despotic,” “dark,” and “benighted” when speaking of the spiritual environment in Italy.[20] This duality of both fascination and revulsion is apparent in Lorenzo Snow’s missionary record in which he recalled that “amid the loveliness of nature I found the soul of man like a wilderness. From the palace of the King, to the lone cottage on the mountain, all was shrouded in spiritual darkness.” He then lamented: “O Italy! thou birth-place and burial-ground of the proud Caesars, who swayedst the sceptre of this mundane creation—land of literature and arts, and once the centre of the world’s civilization—who shall tell all the greatness which breathes in the story of thy past? and who, oh! who shall tell all the corruption which broods on thy bosom now?”[21]

Italy’s vital geographical location as a nexus between Europe, Asia, and Africa is a third factor that weighed heavily in the decision to open a mission there. It is not certain whether this was part of a specific plan that was already in place when the first missionaries were called in 1849, or whether the idea evolved as missionary work progressed. But Snow and the other missionaries eventually viewed the Italian Mission as the essential cog in a broad strategy for taking the gospel to countries of the Mediterranean littoral—and beyond. As an Apostle, Snow was responsible for introducing the church into unreached areas under his jurisdiction, and he envisioned Italy as a base and jumping-off point for preaching the gospel in Switzerland, Malta, Spain, Gibraltar, Egypt, Greece, Turkey, Russia, and India. The basic premise of this grand strategy was that, given Italy’s proximity to three continents, its extensive commercial relations, and the ability of its seafaring people to speak several languages, even a few converts made in Italy would provide a seedbed from which the gospel would be transplanted, take root, and grow to maturity in surrounding areas.

This strategy was a recurring theme among the early missionaries. At the dedication of Italy in September 1850, Jabez Woodard prophesied that “the Work of God will at length go from this land to other nations of the earth.”[22] Later, while serving as mission president, he wrote to Snow: “The great thought which now occupies my mind is to put the leaven at work, as you say. . . . I cast many longing looks and anxious reflections however towards other localities. Turin does not present any opening, but towards the Mediterranean it seems that amid the goings and comings of commerce, some of the seeds might travel far.”[23]

The metaphor of a small amount of leaven slowly expanding its influence was a favorite of the missionaries, especially Snow. He explained his strategy for spreading the gospel from Italy: “Nor will the importance of this mission be limited to Italy; the way will open from hence to other parts of the world. There has long been an intimate connexion between the Protestants here and in Switzerland. I intend to avail myself of this circumstance, that the gospel may be established in both places.”[24] In another letter he elaborated on his expansive vision, explaining that he hoped to reach other parts of southern Europe and Asia, including Greece, Egypt, the Russian and Turkish empires, and “the burning climes of India”:

The Waldenses were the first to receive the Gospel, but by the press and the exertions of the Elders, it will be rolled forth far beyond their mountain regions. . . . Italian States are well known as being among the most hostile upon earth to the introduction of religious truth, but as their subjects are in constant communication with many countries that are washed by the Mediterranean, they will have facilities for hearing the Gospel as we come into connection with their maritime relations; and being acquainted with all the languages around that Central Sea, the thousands of Italians who do business upon its waters, will furnish some faithful men to speed on the kingdom of God through the south and east of Europe.[25]

The same philosophy informed his decision to open missionary work in Malta: “The organization of a branch of our Church here [Malta] would loosen the spiritual fetters of many nations, as the Maltese in their commercial relations, are spread along the shores of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Nearly all speak the Italian, and at the same time, by the peculiarities of their native dialect, they make themselves easily understood by those using the Arabic and Syriac, which are exceedingly difficult for most other Europeans.”[26]

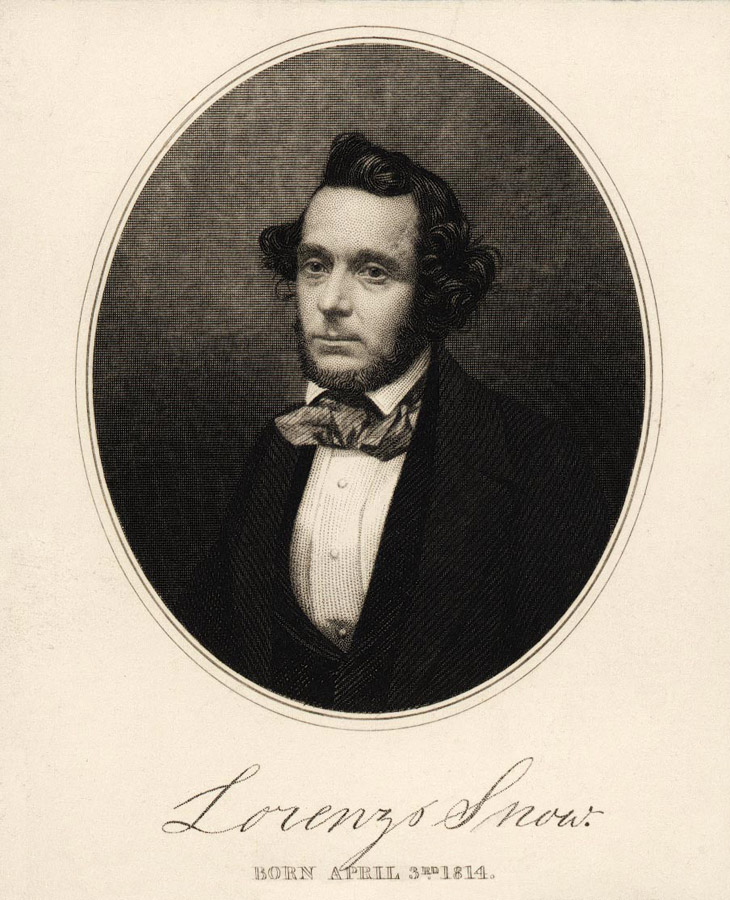

Lorenzo Snow, age thirty-nine, just after returning from his mission to Italy. Courtesy of Utah State Historical Society

Lorenzo Snow, age thirty-nine, just after returning from his mission to Italy. Courtesy of Utah State Historical Society

A fourth reason for the attention accorded Italy by early church leaders is the idea of the continuity of gospel dispensations in Latter-day Saint theology. Church leaders and missionaries viewed Italy as a land sanctified by the presence of some of Christ’s original Apostles and wished to establish the restored church in the land where the ancient church once flourished. There was significance attached to the idea of modern-day Apostles taking up the work in the same physical location where the ancient Apostles had left off.

This sense of connection to a previous apostolic legacy is evident in an editorial in the Millennial Star: The elders laboring in Italy have carried out “a work so great as that which was once committed to a Peter, James, and John, or a Paul,” laboring “in countries which were once under [the ancient Apostles’] immediate supervision by virtue of a commission direct from the Son of God. . . . Now we hear the joyful tidings of flourishing Churches being established in those lands, which possess the same faith, and enjoy the same blessings that those holy men of old declared were necessary to salvation.” The editorial includes a prayer that the saints in Italy and Malta “will honour the footsteps of the ancient Apostles, and the counsel of modern ones.”[27]

Ultimately, the LDS Church’s choice of Italy as one of its first non-English-speaking mission fields had more to do with theology, history, and global strategy than with considerations of its contemporary political, economic, or spiritual conditions. As the missionaries discovered soon after their arrival, Italy presented many serious obstacles and challenges that prevented the kind of proselytizing success that Elder Snow and other missionaries had enjoyed in Great Britain.

By Land and Sea to Liverpool

The group of thirty-two travelers that departed Salt Lake City in October 1849 included missionaries bound for England and Continental Europe as well as some individuals on their way to the eastern United States to conduct business.[28] Among the group were four members of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles—Lorenzo Snow, Erastus Snow, and John Taylor—who had been assigned to open missions in Italy, Denmark, and France, and Franklin Richards who was headed to Liverpool to succeed Orson Pratt as president of the British Mission.[29]

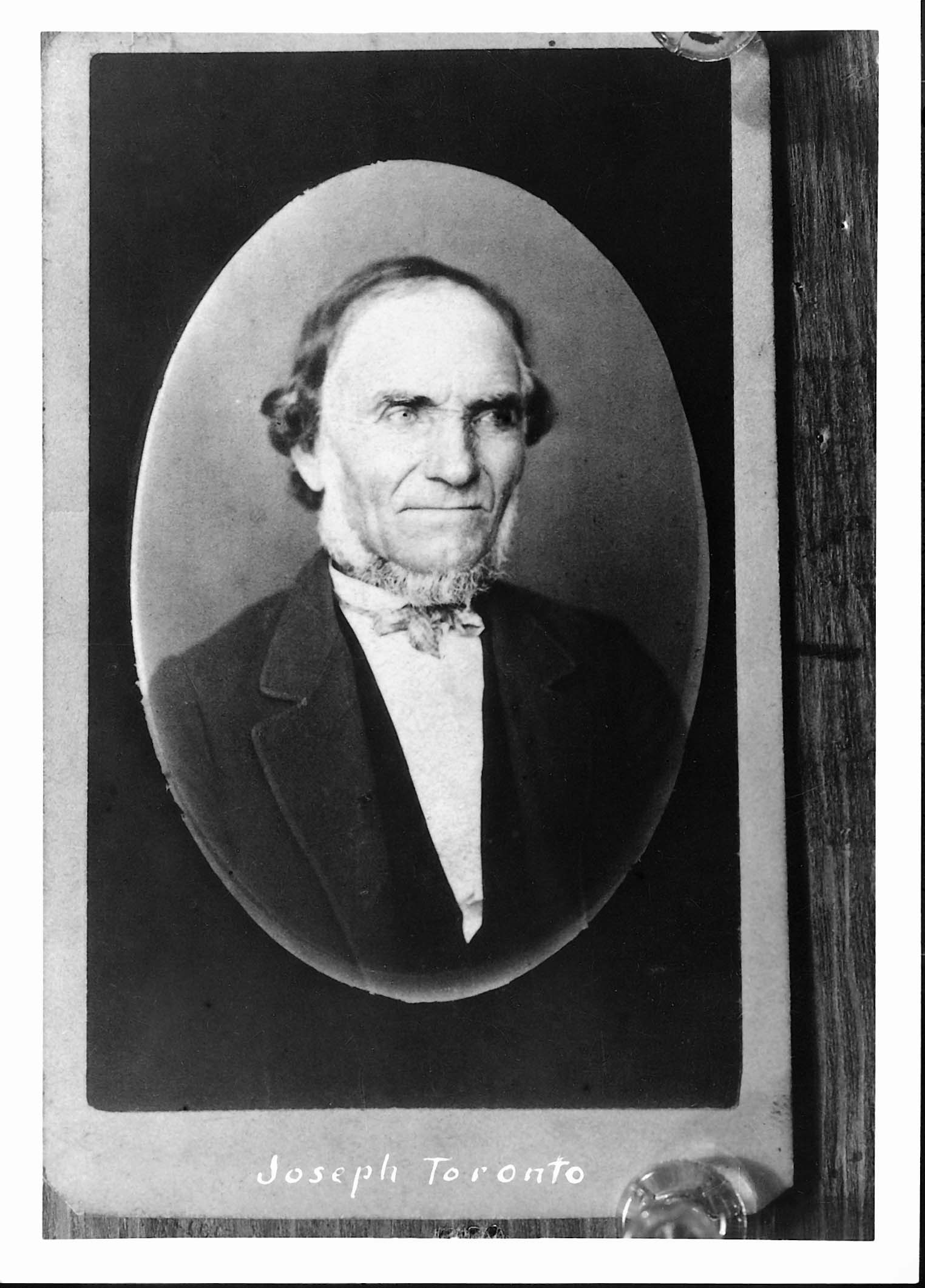

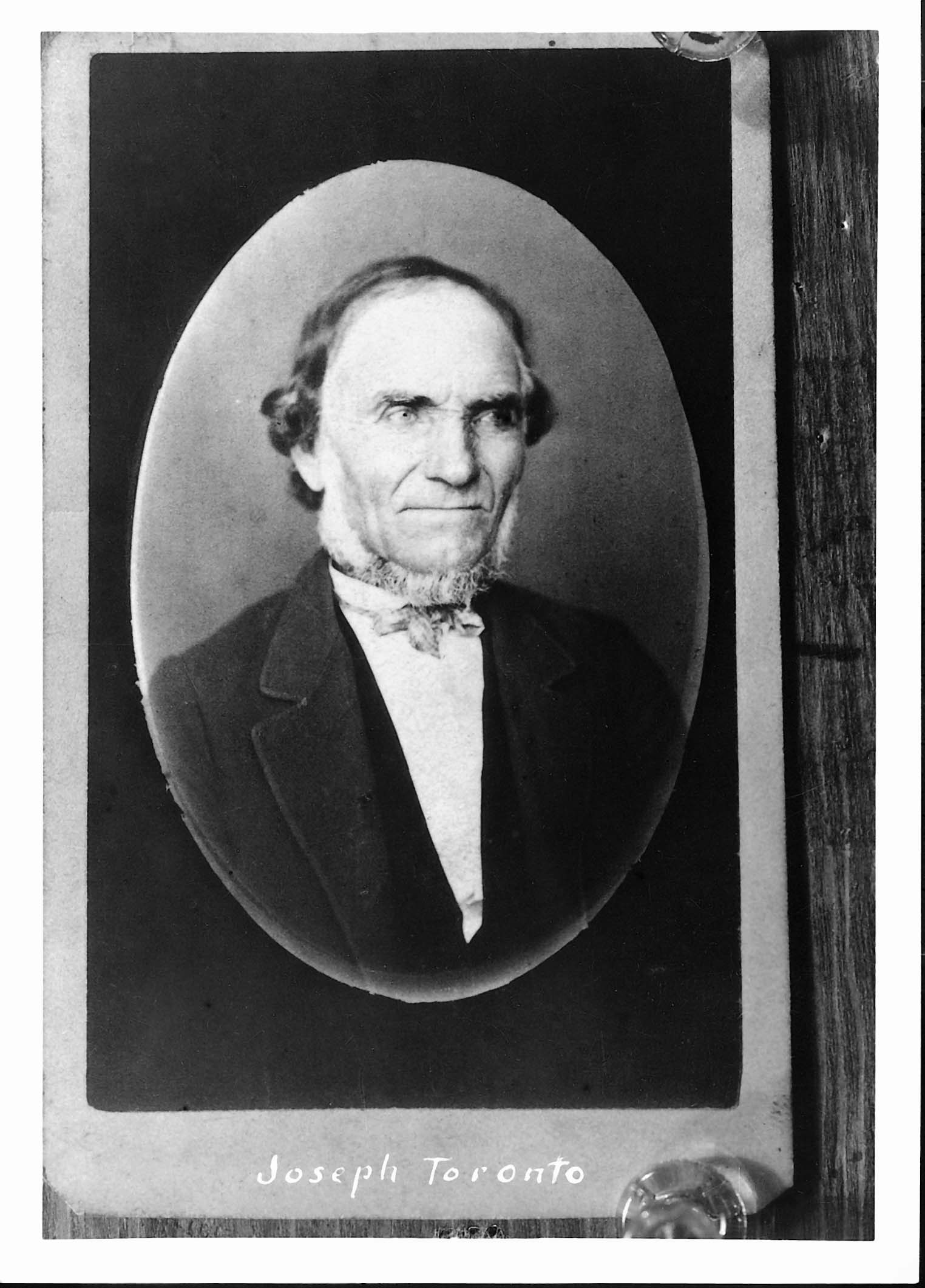

Photo of Giuseppe Efisio Taranto, also known as Joseph Toronto, taken later in his life. Courtesy of James Toronto.

Photo of Giuseppe Efisio Taranto, also known as Joseph Toronto, taken later in his life. Courtesy of James Toronto.

Lorenzo Snow, age thirty-five, like many early church missionaries, was well educated and already married when called to missionary service. He later wrote to his sister, Eliza, recalling the bittersweet experience of leaving the familiar comforts of home to face an uncertain future: “In solemn silence I left what, next to God, was dearest to my heart—my friends, my loving wife, and little children. . . . We were hastening further and still further from the mighty magnet—HOME! but we knew that the work in which we were engaged was to carry light to those who sat in darkness, and in the Valley of the Shadow of Death, and our bosoms glowed with love, and our tears were wiped away.[30]

By contrast, Snow’s fellow missionary Joseph Toronto, age thirty-three, was unmarried and unlettered, an immigrant who was likely the first Italian to join the church. Having been away from his home town of Palermo for several years, he started the long journey eastward with different feelings—not a tug backward, but a pull forward—the anticipation of seeing his family and friends again in Sicily and sharing with them the new religion he had embraced in America.[31]

Several members of the group wrote careful accounts of the long, arduous trek across the mountains, rivers, and plains of the western frontier, recording everyday events that both challenged their ingenuity and confirmed their faith. While stopped for lunch one day on the banks of the Platte River near Fort Laramie, an alarming shout was raised: “To arms! To arms! The Indians are upon us!” A band of about two hundred Cheyennes, dressed in war paint and feathers, were riding at full gallop toward them, readying their guns and bows for combat. The Mormons quickly secured their livestock and wagons and took a defensive posture, but just as the Indians drew within shooting distance, they suddenly pulled their horses up short and the chief made gestures of peace. A rudimentary form of communication in French was established, and the hostile scene soon changed to a more amicable one as the Mormons shared their lunch of crackers, dried meat, and other “dainties” with the Indians and provided some tobacco and flour as gifts.[32] To reciprocate, the Cheyenne chiefs invited several missionaries, including Lorenzo Snow and John Taylor, to visit their camp where they dined on buffalo meat and engaged in conversation until nightfall.[33]

Snow noted “many incidents,” including the tempering of the natural elements, that he interpreted as evidence of divine support for their mission: “When the snows began to fall, winds swept our pathway, and enabled us to pass without difficulty, while, on our right and left, the country was deeply covered for hundreds of miles. . . . When we arrived on the banks of the great Missouri, her waters immediately congealed for the first time during the season, thus forming a bridge over which we passed to the other side: this was no sooner accomplished than the torrent ran as before.” He concluded that “in our past experience, the hand of the Lord had never been more visibly manifested.”[34]

Upon their arrival in the Mormon settlement of Kanesville (Council Bluffs), Iowa, the travelers “were saluted with shoutings, firing of cannons, songs of rejoicing, and other demonstrations of welcome.”[35] Shortly thereafter they split into smaller groups to continue the journey to St. Louis, with two groups departing by wagon on 29 December. This was in part for their safety, according to Job Smith, as anti-Mormon sentiment and “a spirit of mobocracy” were still strong in some communities in Missouri. For this reason they also avoided telling people where they came from and, at times, wore disguises to conceal their identity.[36]

The journey to St. Louis took about two weeks, and for Erastus Snow’s group, the last 150 miles were especially slow and tedious because they were forced to walk most of the way “as there was a thaw and the mud was hub deep in the lanes.” But Snow also reported that, in spite of the constant threat from mobs and the drudgery of harsh weather conditions, there was time for pleasantries and warm associations along the way. Their visits with Latter-day Saint families were gratifying as were the friendships spontaneously struck up with other travelers, including “a French gentleman with whom we took a glass of wine” and who “was delighted with our company.”[37]

Lorenzo Snow and his group traveled to St. Louis through Mount Pisgah and Garden Grove (Mormon outfitting locations) where he enjoyed visiting with old acquaintances. They also traveled through Nauvoo and Carthage, Illinois, two cities that evoked painful memories and feelings. Snow wrote that his heart “sickened” as he contemplated the deterioration of Nauvoo and viewed the burned-out shell of the temple. Passing through Carthage, “that guilty place,” he became deeply agitated as he thought about the murder of his friends, Joseph and Hyrum Smith, in 1844. Even though he was hungry and tired, “nothing could induce me to eat or drink among that accursed and polluted people.”[38] When he reached St. Louis, Snow and his travel companions were delighted to find a large, well-organized branch of nearly four thousand members who had constructed a spacious meeting hall.

The missionaries took time in St. Louis to rest and replenish their supplies in preparation for the next leg of their journey. Snow traveled from St. Louis to New York City, then departed from there on 25 March 1850 on board the Shannon, arriving in Liverpool, England, four weeks later on 19 April. Toronto left St. Louis in company with one other elder, Peter Hansen, traveling by steamer down the Mississippi River and arriving in New Orleans on 17 February. There they rejoined six other elders who had left Salt Lake City the previous October, and after a fund-raising effort among the members, enough money was collected for the missionaries to secure passage and purchase supplies for the ocean voyage.[39]

On 26 February 1850, Toronto and the other seven missionaries set sail from New Orleans on board the ship Maine, and on 28 February their ship was dragged over the sand bar at the mouth of the Mississippi River into the open waters of the Gulf of Mexico by two steam-powered tugboats. Despite some extremely rough weather and heavy winds that broke the main topsail, the missionaries enjoyed good health during the six-week voyage, landing on 8 April in Liverpool, where they were warmly received by church leaders and members.

A Welcome Hiatus in England

During the two-month stopover in England, where he had served as a missionary eight years earlier, Snow busied himself with the duties of his apostolic office: taking care of administrative matters, preaching the gospel, and strengthening the Saints. After spending some time with fellow apostles Erastus Snow and Franklin Richards at the headquarters of the British Mission in Liverpool, he traveled inland to visit the conferences of the church: Manchester, Macclesfield, Birmingham, Cheltenham, South Conference, London, and Southampton. He clearly relished the opportunity to associate with those in his old mission field whom he had previously taught and baptized, his “children in the Gospel” as he called them. He noted that, in contrast to his first mission when he was “a lonely foreigner, unacquainted with the manners, laws, customs, and institutions of the country,” he now felt “comparatively at home.”[40]

Thomas Brown Holmes (T. B. H.) Stenhouse. Courtesy of Utah State Historical Society.

Thomas Brown Holmes (T. B. H.) Stenhouse. Courtesy of Utah State Historical Society.

One of the most pressing tasks facing the missionaries was acquiring the financial support to cover travel, food, lodging, publication of church literature, and other costs incidental to missionary labor. The system of mission finance at the time provided little assistance from general church funds, and the missionaries themselves contributed their own means to the extent possible. But missionary records indicate that they depended heavily on donations from local members, either in cash or in kind, to supply their financial needs. Erastus Snow wrote that, while traveling from Kanesville to St. Louis, their “means increased by gifts from the brethren.”[41] After arriving in St. Louis, Job Smith reported that “subscriptions were made in the meetings of the St. Louis branch of the church for money to bear our expenses to England,” but that they received only enough to buy tickets for the steamboat to New Orleans. Once there, another “subscription” was taken up and $150 collected—just enough to secure passage for nine or ten missionaries to Liverpool. Smith expressed his admiration for the generosity of the church members, many of whom were also facing financial duress: “I must say that the Saints who resided in New Orleans acted upon as liberal principles as I ever saw among any people. . . . Most of the Saints in New Orleans were poor and were stopping there temporarily earning means wherewith to prosecute their journey to the [Salt Lake] Valley.”[42] In England, Lorenzo Snow noted that many church members, even some in Wales whom he had not visited, sent him donations and “contributed liberally towards my mission . . . with all that nobleness of soul which gives unasked.”[43]

Massacre of teh Waldensians of Merindol in 1545, by Gutave Dore (1832-83). Courtesy of Michael W. Homer.

Massacre of teh Waldensians of Merindol in 1545, by Gutave Dore (1832-83). Courtesy of Michael W. Homer.

Another reason Snow visited the various conferences in England was to recruit more missionaries to assist in opening the new mission, and while meeting with the members in Southampton, he felt inspired to call Thomas Brown Holmes (T. B. H.) Stenhouse to accompany him and Toronto to Italy.[44] He also met Jabez Woodard, age twenty-nine, who had converted to the church less than a year earlier but was already serving as president of the Kent Road Branch of the London Conference. Woodard was a keen student of history and languages who had studied Latin and French and had learned enough German, Greek, Spanish, and Italian to read the Bible in those languages. During their conversation, Snow no doubt became aware of Woodard’s linguistic abilities and, recognizing their value in the mission field, called him as a missionary on the spot. Woodard simply recorded that during their meeting “Brother Lorenzo . . . ordered me to follow him to Italy. He went on with Brother Stenhouse and Toronto. I was left to arrange my affairs but how to make provisions for my wife and 2 girls I could not tell.”[45] During these visits Snow also met other church members who would eventually be called to the Italian mission, including Thomas Margetts and Samuel Francis.

During this period, Snow considered where to begin their missionary labors in Italy. He was drawn to the history of the Waldensians, a Protestant religious community in the northwest Piedmont region of the peninsula.[46] Snow knew that the Waldensians, like the Mormons, had bravely suffered religious persecution, and he was also aware that two years previous, the Sardinian government had granted them a greater degree of political and social freedom. He concluded that “no other portion of Italy is governed by such favourable laws.” He recorded that “a flood of light seemed to burst upon my mind when I thought upon the subject” and that he began to think of this Protestant people “like the rose in the wilderness, or the bow in the cloud.”[47]

The Waldensians were descended from a Catholic reform movement that a merchant named Valdès or Waldesius organized during the late twelfth century in Lyon, France.[48] Valdès, and his “poor of Lyon,” believed that the Roman Catholic clergy had become worldly and sinful, and he urged lay parishioners to set a better example for the church by living in poverty and preaching repentance, even though they were not ordained and they had not received permission to preach from their bishop. Valdès initially believed in the doctrines and sacraments of the Roman Catholic Church—he signed a statement of faith in 1180—but the clergy resented the “Poor Men” not only because they were uneducated but also because they seemed to usurp priestly prerogatives.

In 1184, Valdès and his followers were excommunicated when they refused to cease preaching, and the movement was thereafter included in a list of schisms. Expelled from Lyon, they eventually established communities in Piedmont, Lombardy, Puglia, Calabria, Provence, Languedoc, and Bohemia. For the next three hundred years, they lived in isolated rural communities in Italy, France, and Germany where they attended mass publicly but practiced their true religious convictions surreptitiously. Although they were occasionally subjected to religious persecution, they were for the most part left alone and targeted for political and religious persecution only when they aligned themselves with Swiss reformers. Such an alignment, which naturally required the modification of many beliefs, practices and organization, took years to implement.[49]

When Snow visited a public library in Liverpool to obtain more information on the Waldensians, he had a singular experience that reinforced his already positive feelings: “The librarian to whom I applied informed me he had a work of the description I required, but it had just been taken. He had scarcely finished the sentence when a lady entered with the book. ‘Oh,’ said he, ‘this is a remarkable circumstance, this gentleman has just called for that book.’ I was soon convinced that this people were worthy to receive the first proclamation of the Gospel in Italy.”[50] The volume Snow sought, Sketches of the Waldenses,[51] drew heavily on an 1834 book by Alexis Muston, a Waldensian pastor, who advanced an ancient origins thesis that the Waldensians were a remnant of the primitive Christian Church rather than the descendants of twelfth century church heretics.[52] Muston wrote that the “Waldenses have been the means of preserving the doctrines of the gospel in their primitive simplicity. . . . They were doubtless designed to preserve the germ of another spring, through the winter of the middle ages; like the leaven hid in three measures of meal, or the precious seed set aside by the husbandman to produce a future harvest.”[53]

This tract reflected the belief of many Protestants that the Waldensians provided a “chain by which our Reformed Churches are connected with the first disciples of Christ” and that they were “preserved for a special purpose in the Divine Counsels; destined to fulfill a most important mission in the Evangelization of Italy.”[54] According to this ancient origins thesis, the Waldensians did not accept the changes instituted by the Catholic Church but had instead “remained on the old ground” and were entitled to “the indisputably valid title of the True Church.”[55] They were “the remnant of the early apostolic Church of Italy,” and “their traditions invariably point to an unbroken descent from the earliest times, as regards their religious belief.”[56] As the LDS mission to Italy was opening, most Protestants continued to believe that the Waldensians originated much earlier than the twelfth century when Valdès and his followers were excommunicated by the Catholic hierarchy.[57]

But Snow was not the first Mormon to marvel at the Waldensians’ claims to have ancient origins and their history of persecution. Brigham Young and other church leaders were aware of the Waldensians and saw parallels to Mormon experience in their persecutions, migrations, and claims of ancient roots in the primitive Christian Church. In 1834, Sidney Rigdon commented on William Jones’ History of the Waldenses and noted that they “were doubtless the remains of the apostolic church.” Rigdon also noted the similarity between the “persecutions” and “outlandish falsehoods” that had been perpetrated against the Waldensians and the Mormons.[58] Other Mormon leaders, including Brigham Young and John Taylor, also compared Mormon persecutions with those of the Waldensians.[59] Another prominent church leader, John C. Bennett, claimed that the persecutions of the Mormons were much worse than those experienced by the Waldensians.[60] Other Mormon leaders compared the teachings of the Waldensian Church, particularly those they believed were preserved from the primitive church, with their own doctrine.[61]

Snow came to the same conclusion as these early church leaders that the Waldensians were better candidates for conversion than the Catholics. He was convinced that they shared many perspectives concerning church doctrine and practices, including a belief that the Catholic Church had fallen into apostasy and that many characteristics of the “primitive Church” had been preserved in their mountain valleys. Some Waldensians also believed in spiritual gifts, including miracles, visions, and gifts of tongues.[62]

The Beginning of Missionary Work in the Waldensian Valleys

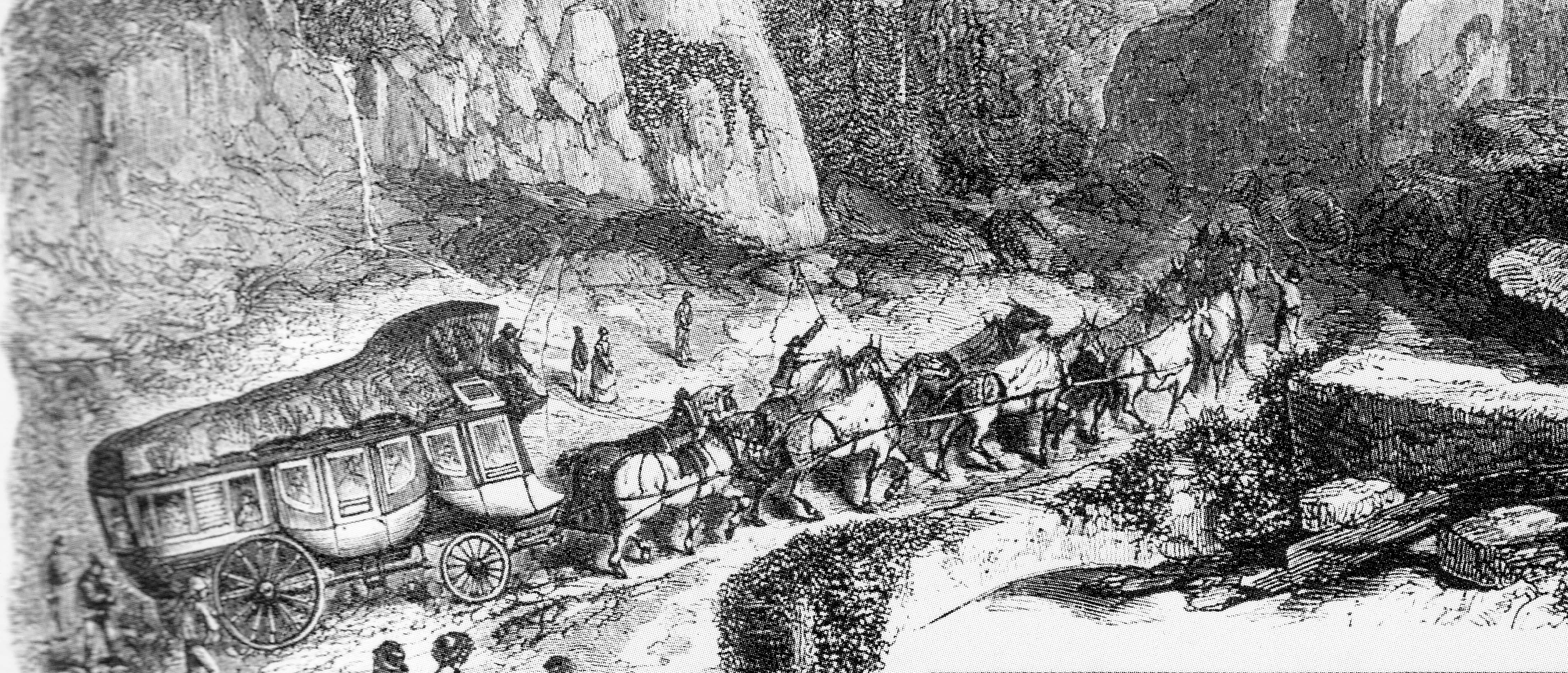

The three missionaries—Snow, Toronto, and Stenhouse—left Southampton on 15 June 1850 on board the steamboat Wonder, crossed the English Channel to Havre de Grace, France, and continued overland to Paris. They proceeded through the picturesque farmlands of southern France, passing through Lyon and arriving at the seaport of Marseille after a four-day journey. To avoid a six-day quarantine in the harbor at Genoa, they decided to sail from Marseille to Antibes, then travel along the Mediterranean coastline by horse-drawn carriage, or diligence,[63] to Nice, which was at the time a part of the Kingdom of Sardinia.[64] Continuing along the Ligurian coast, they arrived in Genoa on 25 June 1850, having completed the journey from Utah to Italy in about eight months.

After arriving in Genoa, the Mormon missionaries took a few days to become acquainted with their new surroundings. Snow was intrigued by the great number of Catholic priests, images of the Virgin Mary, and armed men roaming the city. He observed that commerce seemed to be languishing since the revolution in the Sardinian government a few years earlier. A visit to the great cathedral of San Lorenzo—“the most superb and richly decorated interior of any building I had ever seen”—left Snow awe-struck by the excellence of Italian art and architecture. Listening to the Catholic mass there evoked mixed feelings: “Our minds were absorbed in the contemplation of the beauty and richness of art, the power of unity, and the darkness of human understanding.”[65]

Snow dispatched Toronto and Stenhouse to the Waldensian valleys of Piedmont to survey conditions there. After receiving an encouraging letter from them three weeks later, he wrote to Franklin Richards in Liverpool confirming his intention to move forward as planned: “I have felt an intense desire to know the state of that province to which I had given [Toronto and Stenhouse] an appointment, as I felt assured it would be the field of my mission. Now, with a heart full of gratitude, I find that an opening is presented in the valleys of the Piedmont, when all other parts of Italy are closed against our efforts. I believe that the Lord has there hidden up a people amid the Alpine mountains, and it is the voice of the Spirit that I shall commence something of importance in that part of this dark nation.”[66]

The diligence was a large horse-drawn carriage used for public transport, often across long distances. Reprinted from E. Riow, Passaggio del Moncinesio (circa 1860). Reprinted from Franco Paloscia, ed., I1 Piemonte dei Grandi Viaggiatoir (Rome: Abete, 1991), 42-43.

The diligence was a large horse-drawn carriage used for public transport, often across long distances. Reprinted from E. Riow, Passaggio del Moncinesio (circa 1860). Reprinted from Franco Paloscia, ed., I1 Piemonte dei Grandi Viaggiatoir (Rome: Abete, 1991), 42-43.

Snow left Genoa on 23 July traveling north to Turin, then continuing southwest another forty kilometers to Torre Pellice, the principal town of the Waldensian community in the foothills of the Cottian Alps. Torre Pellice in 1850 was a bustling town of about 3,000 inhabitants, well on its way to becoming church headquarters of the Waldensian community. Situated on a strategic valley passage at the confluence of the Angrogna and Pellice rivers, its origins can be traced as far back as the eleventh century AD when castles and towers were constructed for protection throughout the region following the Arab invasions. It was from a fortified tower (Italian, torre) located at this site in the Pellice valley from which the name “Torre Pellice” derived.[67]

Just one year before Snow’s arrival, the Pellice Valley elected Joseph Malan as its first representative to the Subalpine Parliament of the Savoy government in Turin following the historic political reforms of 1848. The growth of hydro-powered industries along the two rivers, the foundation of newspapers and printing presses, and the creation of important institutions such as a hospital (1824), teacher’s college (il Collegio, 1831), literary society (il Circolo Letterario, 1852), and a worker’s guild (la Società Operaia, 1852) all helped establish Torre Pellice as the economic, educational, and intellectual capital of the Waldensian valleys. During the same period it also gradually became the headquarters of the Waldensian Church, with the convening of the annual churchwide Synod there and plans for the construction of the theological school (la Facoltà Valdese di Teologia, 1855–60) and the main offices of the church (la Casa Valdese, 1889, including a museum and library). Another sign of Torre Pellice’s emerging importance was the opening of a caffè chantant, a restaurant with musical entertainment that was all the rage in Europe at the time—an event that scandalized the more pious elements of this conservative mountain district.[68] Before 1860 there was only one main street that ran from one end of town to the other, but the steady development of industrial and social enterprises gave rise to significant immigration.

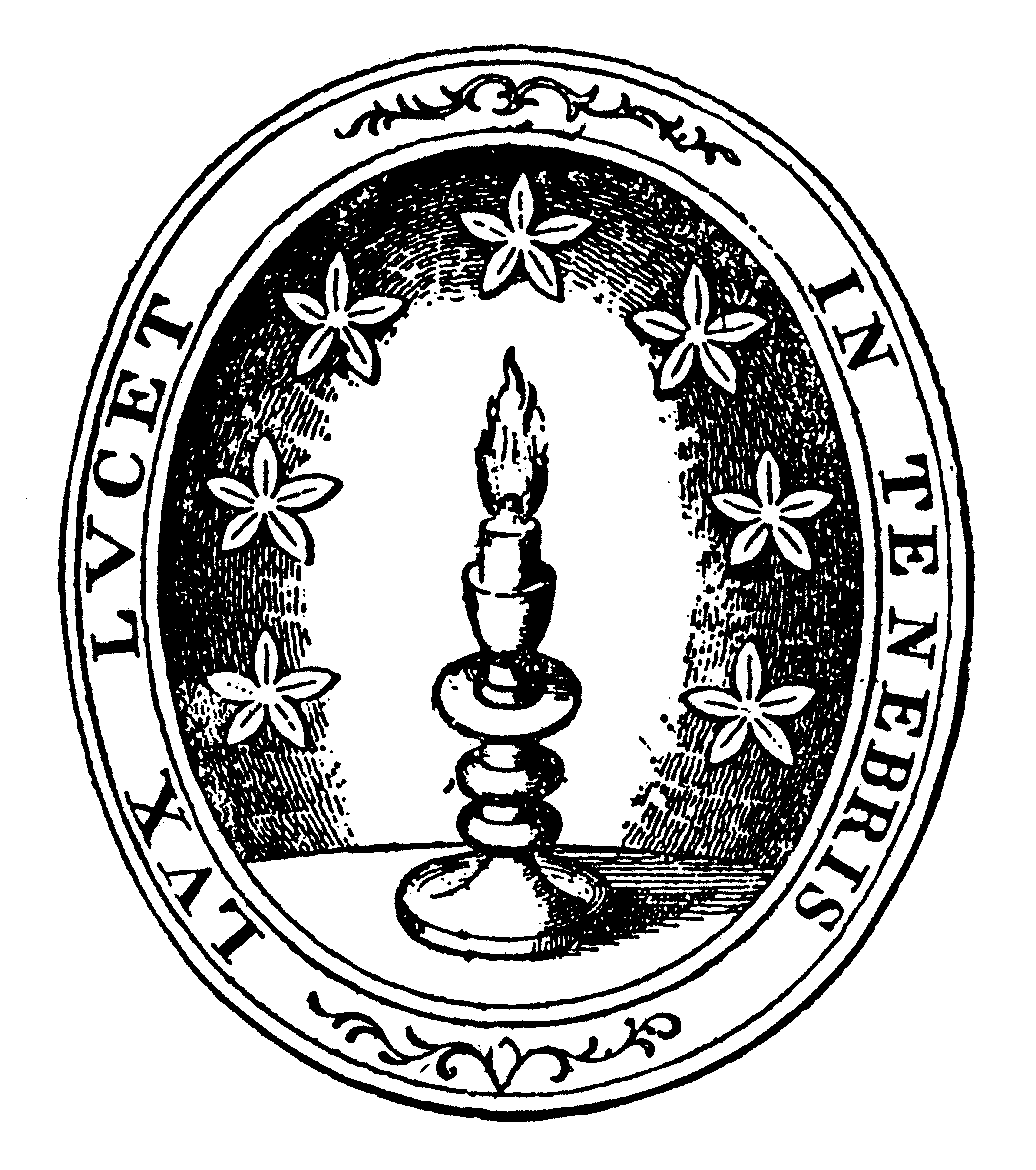

The official symbol of the Waldensian Church: a candlestick (often positioned on a bible) with seven surrounding stars and the caption in Latin "Lux Lucet in Tenebris" (A Light Shining in the Darkness. This symbol and motto signify the history of the Waldensian people who suffered centuries of persecution for their religious beliefs.

The official symbol of the Waldensian Church: a candlestick (often positioned on a bible) with seven surrounding stars and the caption in Latin "Lux Lucet in Tenebris" (A Light Shining in the Darkness. This symbol and motto signify the history of the Waldensian people who suffered centuries of persecution for their religious beliefs.

When Snow and his missionary companions reached Torre Pellice, they rented a room in the Hôtel de l’Ours (Albergo dell’Orso in Italian) which was located in the town’s central piazza, Place de la Tour (Piazza della Libertà).[69] It was the oldest hotel in Torre Pellice, where many foreign visitors stayed during the nineteenth century.[70] Once settled, the missionaries began to consider how best to go about the task of introducing a new faith to a religious community whose devotion to their traditions had been forged by hundreds of years of persecution and isolation.

Snow found hope in similarities he noted between the geography and people of Pellice Valley and Great Salt Lake Valley which, he reported to Brigham Young, bear “a striking resemblance.” He was impressed by the stunning natural beauty of the forested cliffs and ravines lying at the foot of the Alps, often shrouded in clouds and covered with snow. He was also delighted to find that many of the inhabitants of the Waldensian valleys, estimated by him at about twenty-one thousand Protestants and five thousand Catholics, were fair-haired, had light complexions, and reminded him of his own people in the valleys of the West. Based on these physical characteristics and their association in early Mormon doctrine with the high incidence of “believing blood” among northern European peoples, Snow felt reassured that “the Lord had directed us to a branch of the House of Israel.”[71]

Though encouraged by these first impressions, the missionaries felt “it was the mind of the Spirit that we should proceed at first by slow and cautious steps,” probably a result of their growing awareness of the religious restrictions imposed by the Sardinian government, including a ban on public preaching, selling Bibles, or publishing works that attacked Catholicism. While it tested their patience to refrain from discussing their religion publicly, they decided to lay the groundwork first by “preparing the minds of the people for the reception of the Gospel, by cultivating friendly feelings in the bosoms of those by whom we were surrounded.” Snow later reported that their low-key approach had been successful in keeping them “from being entangled in the meshes of the law” and that “all the jealous policy of Italy has been hushed into repose by the comparative silence” of the missionaries’ activities. “At the same time,” he pointed out, the three Mormon elders kept busy, “always engaged in forming some new acquaintance, or breaking down some ancient barrier of prejudice.”[72]

A postcard showing Hotel de I'Ours (also known as Albergo dell'orso), which was the oldest and most popluar hotel in Torre Pellice when the first Mormon missionaries resided there in 1850. Courtesy of Archivio Fotografico del Centro Culturale Valdese (Torre Pellice), Editrice Claudiana and Gabriella Ballesio.

A postcard showing Hotel de I'Ours (also known as Albergo dell'orso), which was the oldest and most popluar hotel in Torre Pellice when the first Mormon missionaries resided there in 1850. Courtesy of Archivio Fotografico del Centro Culturale Valdese (Torre Pellice), Editrice Claudiana and Gabriella Ballesio.

During this period of “cultivation,” Snow reported that the missionaries were able to communicate with the local people only in rudimentary fashion—“as much, perhaps, by signs as by the few words of their language which we had acquired”—and that “the enemies of truth” were disseminating negative publicity about the Mormons.[73] Yet he also noted that even in this far flung region such anti-Mormon literature was circulating. “In this country,” Snow wrote, “a ‘History of the Mormons’ is widely spread. . . . I need scarcely say that, the sketches of the artist, and the tale of the historian, are in perfect harmony, and both as near the truth as the east is to the west.”[74]

One event in particular, which occurred in September 1850, marked a turning point in Snow’s thinking about mission strategy, and in his report to Brigham Young he took pains to copy the account of it verbatim from his journal.[75] During his seven months in Italy, Snow stayed in Torre Pellice at the Hôtel de l’Ours that was owned by Giovanni Giacomo Peyrot. One of Peyrot’s daughters, Caroline, was married to Joseph Malan who was a member of the Italian Chamber of Deputies and the godfather of Joseph Gay, the three-year-old son of Jean Pierre Gay and Henriette Coucourde who were the hotel’s managers.[76] Snow became aware that Joseph Gay was very ill, that his parents believed he would soon die, and that many family friends had already stopped by to pay their last respects.

After visiting the boy and reflecting on the situation, Snow’s mind became “fully awakened to a sense of our position.” The next morning he suggested to his companion, Stenhouse, that they retreat to the mountains to fast and pray. As they left the hotel they stopped to see the sick child and found “the cold perspiration of death covered his body” and the women of the house sobbing. The boy’s father whispered to them, “Il meurt! Il meurt!” (He dies! He dies!). After several hours of solemn prayer on the mountain, the two missionaries returned to town convinced that God had provided an opportunity to make a breakthrough in introducing Mormonism in Italy. Snow later wrote that “I regarded this circumstance as one of vast importance. I know not of any sacrifice which I could possibly make, that I was not willing to offer, that the Lord might grant our requests.”[77]

Joseph Malan (1810-86), the first Waldensian elected to the House of Deputies of the Kingdom of Sardinia in 1848, corresponded with the Waldensian leadership concerning Mormon proselytism in the valleys. Courtesy of Archiio Fotographico del centro Culturale Valdese(Torre Pelllice), Editrice Claudiana and Gabriella Ballesio.

Joseph Malan (1810-86), the first Waldensian elected to the House of Deputies of the Kingdom of Sardinia in 1848, corresponded with the Waldensian leadership concerning Mormon proselytism in the valleys. Courtesy of Archiio Fotographico del centro Culturale Valdese(Torre Pelllice), Editrice Claudiana and Gabriella Ballesio.

While visiting the Gay family that afternoon, Snow consecrated some olive oil, anointed his own hand with the oil, placed it upon the head of young Joseph, and the two missionaries silently prayed that God would spare his life. Several hours later his father reported that the boy’s health was much improved, and the following day, 8 September, the elders learned that the boy was well enough for the parents to leave him to get some rest and go about their daily business again. When Mrs. Gay expressed her happiness at her son’s recovery, Snow remarked in Italian, “Il Dio di cielo ha fatto questa per voi” (The God of heaven has done this for you).[78]

Snow does not mention whether relatives and neighbors of the Gay family in the close-knit Waldensian community reacted to the news of Joseph’s remarkable recovery or whether there was any marked increase in religious discussions with the people. It is possible, however, that word of it reached young Joseph Gay’s godfather. Joseph Malan was the only Waldensian member in the Kingdom of Sardinia’s House of Deputies, elected in the first election following King Carlo Alberto’s Edict of Emancipation. Although Malan lived in Turin, where he was a banker, he had many friends and relatives in the valleys. Because of these connections, Malan may have been aware, as early as 1850, that Mormon missionaries were proselytizing in the Waldensian valleys and that Snow and his companions blessed his dying godson. Malan’s knowledge of the Mormon elders’ kindness to the Gay family may have aided the missionaries’ cause later when the Sardinian government, through Malan, had discussions with the Waldensian leadership concerning the Mormon “problem.”

The Transition to “Public Business”

An artist's stylized rendering of Torre Pellice (or La Tour in French). The drawing includes the Angrogna River, where initial Mormon converts were baptized in 1850-51. It also shows two mountains (Castelluzzo and Vandalino) which Snow climbed and renamed "The Rock of Prophecy" and "Mount Brigham" when he organized the Italian Mission. This image is from a steel engraving made form a drawing by William Henry Barlett (1809-54), a prominent nineteenth-century artist. The engraving first appeared in William Beattie's The Waldenses, or Protestant Valleys of Piedmont, Dauphiny, and the Ban de la Roche (London: G. Virtue, 1838).

An artist's stylized rendering of Torre Pellice (or La Tour in French). The drawing includes the Angrogna River, where initial Mormon converts were baptized in 1850-51. It also shows two mountains (Castelluzzo and Vandalino) which Snow climbed and renamed "The Rock of Prophecy" and "Mount Brigham" when he organized the Italian Mission. This image is from a steel engraving made form a drawing by William Henry Barlett (1809-54), a prominent nineteenth-century artist. The engraving first appeared in William Beattie's The Waldenses, or Protestant Valleys of Piedmont, Dauphiny, and the Ban de la Roche (London: G. Virtue, 1838).

While the Joseph Gay blessing did not produce any immediate or discernible benefits for evangelizing the Waldensians, it clearly had a galvanizing effect on the missionaries’ thinking and helped set the stage for a significant change in strategy. About the time of the blessing Snow concluded that circumstances were “as favourable as could be expected” and decided to send for Elder Jabez Woodard,[79] whom he had met in London several months earlier. On 19 September 1850, one day after Woodard arrived in Torre Pellice, Snow proposed that the missionaries “should commence [their] public business,” or in other words, shift their approach from one of quietly fostering goodwill to one of openly preaching Mormonism.[80]

To initiate this change, Snow, Stenhouse, and Woodard ascended a high mountain near Torre Pellice, and there on a projecting rock formation, Snow offered a prayer dedicating Italy to the preaching of the gospel and imploring God to prepare the hearts and minds of the Italian people to hear the message of his servants.[81] The elders then motioned to formally organize the Church in Italy, with Snow as president and Stenhouse as secretary. The missionaries then sang hymns and took turns praying and prophesying about the future of the Italian Mission. Finally, Snow laid his hands on Stenhouse and Woodard to give them blessings, praying in particular that Woodard, with his knowledge of Italian and French, “might act as Aaron for us, and speak unto the people by the power of God.”[82]

When they had completed their business, they were reluctant to leave a place of such great natural beauty and rich spiritual outpouring. Snow proposed that, in honor of the momentous occasion, they call the mountain “Mount Brigham” and the bold projecting rock on which they stood the “Rock of Prophecy.”[83] The missionaries descended the steep slopes of the mountain, reaching Torre Pellice at dusk after a physically exhausting but spiritually exhilarating day. Thereafter a new chapter opened in the Italian mission, and Snow took care to mark the transition from a private to a public posture with a symbolic act: “As a sign to all who might visit us, we nailed to the wall of my chamber the likenesses of Joseph and Hyrum Smith. From that day opportunities began to occur for proclaiming our message.”[84]

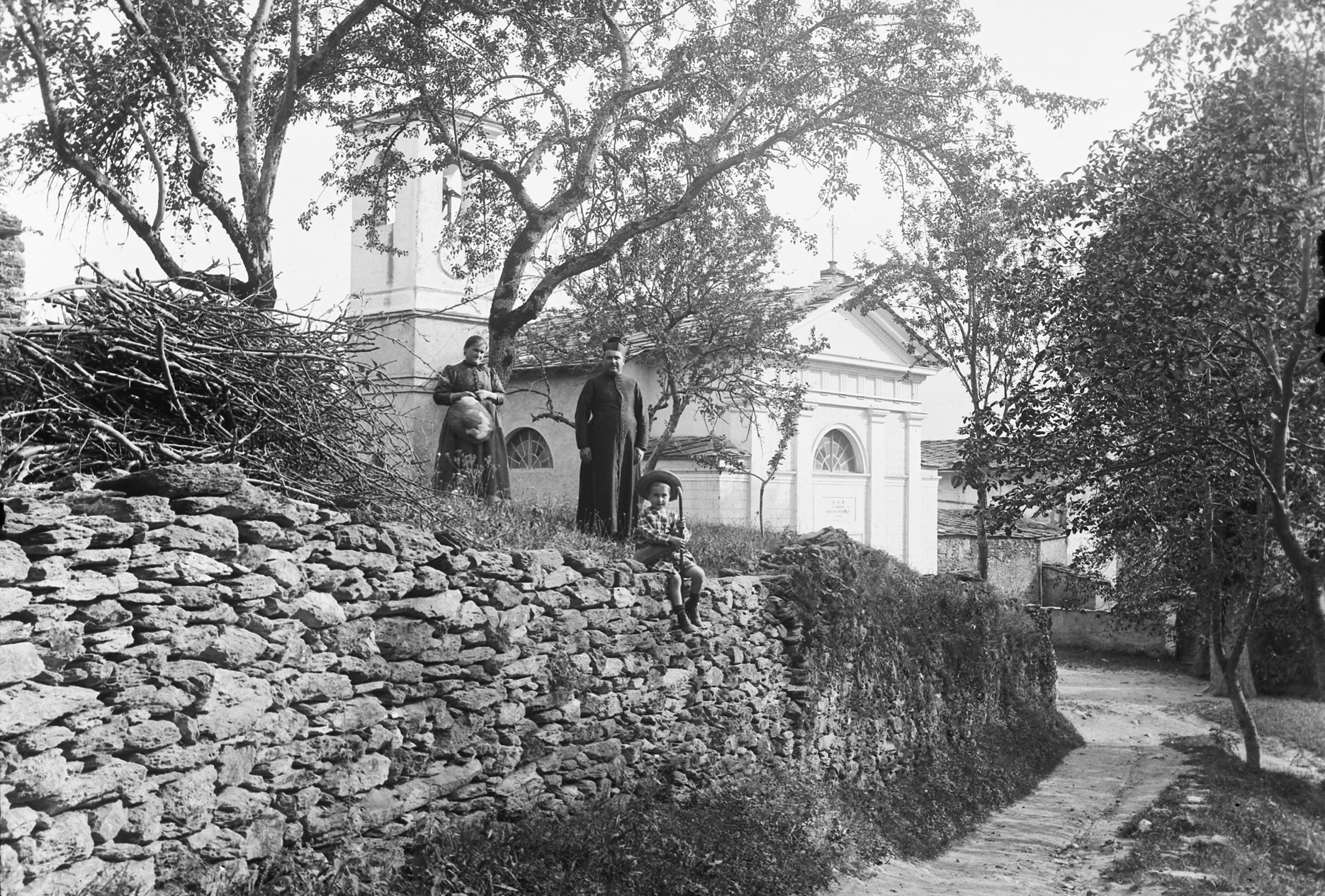

The Chapel of San Lorenzo was the parish church located in the Waldensian valleys where Lorenzo Snow had a friendly encounter with a Catholic priest in 1850. Courtesy of Archivio Fotografico del Centro Culturale Valdese (Torre Pellice), Editrice Claudiana and Gabriella Ballesio.

The Chapel of San Lorenzo was the parish church located in the Waldensian valleys where Lorenzo Snow had a friendly encounter with a Catholic priest in 1850. Courtesy of Archivio Fotografico del Centro Culturale Valdese (Torre Pellice), Editrice Claudiana and Gabriella Ballesio.

Despite this promising start, political tensions in the Kingdom of Sardinia and socioreligious constraints in the Waldensian valleys challenged the mission’s transition to a more traditional missionary approach. Public preaching by non-Catholics was prohibited throughout the kingdom, as Snow noted: “Our presence in this land is only just tolerated and not recognized as any right, founded upon established laws. Liberty is only as yet in the bud.” Deeply rooted traditions and loyalties also presented “formidable opposition to the progress of the Gospel.” The Waldensians, he said, regarded new religious ideas as “an attempt to drag them from the banner of their martyred ancestry,” and the Catholics were suffused “with their proud pretensions to a priesthood of apostolic origin.” Whether Catholic or Protestant, “every man holds a creed which has been transmitted from sire to son for a thousand years, . . . and often he will lay his hand on his heart and swear by the faith of his forefathers, that he will live, and die, as they have lived and died.”[85] These political and social obstacles impelled the missionaries to scale back their plans for open proselytism and to adopt more discreet means of publicizing their message, primarily conversations with individuals and meetings with groups in private homes.

In his effort to raise the profile of the LDS Church in the valleys, Snow managed to meet and become well acquainted with two prominent local leaders. One of these was Giovanni Battista Costa, a Catholic parish priest who extended an invitation for the missionaries to visit him in his offices at the Chiesa di San Lorenzo in the Angrogna Valley. The eighteenth-century church, which was the earliest and one of the largest Catholic churches constructed in the valleys, was built on a hill overlooking the first Waldensian temple built in the valleys in 1555, which Snow observed had “crumbled into ruins.” Snow was pleased that he and his companions had “received every attention from our host” and that Costa served the missionaries the best meal they had experienced in Italy. Snow “took the opportunity of presenting the Truths of the Gospel” and noted that Costa “listened with great attention, and proposed many interesting questions with regard to modern revelation.” Costa then invited Snow to retire for the evening in the living quarters of the former convent. The next morning the prelate presented Snow with an inscribed book of Italian grammar and, after serving the missionaries “an early breakfast, accompanied us some miles on the way” back to Torre Pellice.[86] This brief encounter suggests both the personal kindness of Costa and that the Catholic hierarchy, despite its own political problems, was not overly concerned about the threat of Mormonism among Catholics in the Waldensian valleys.

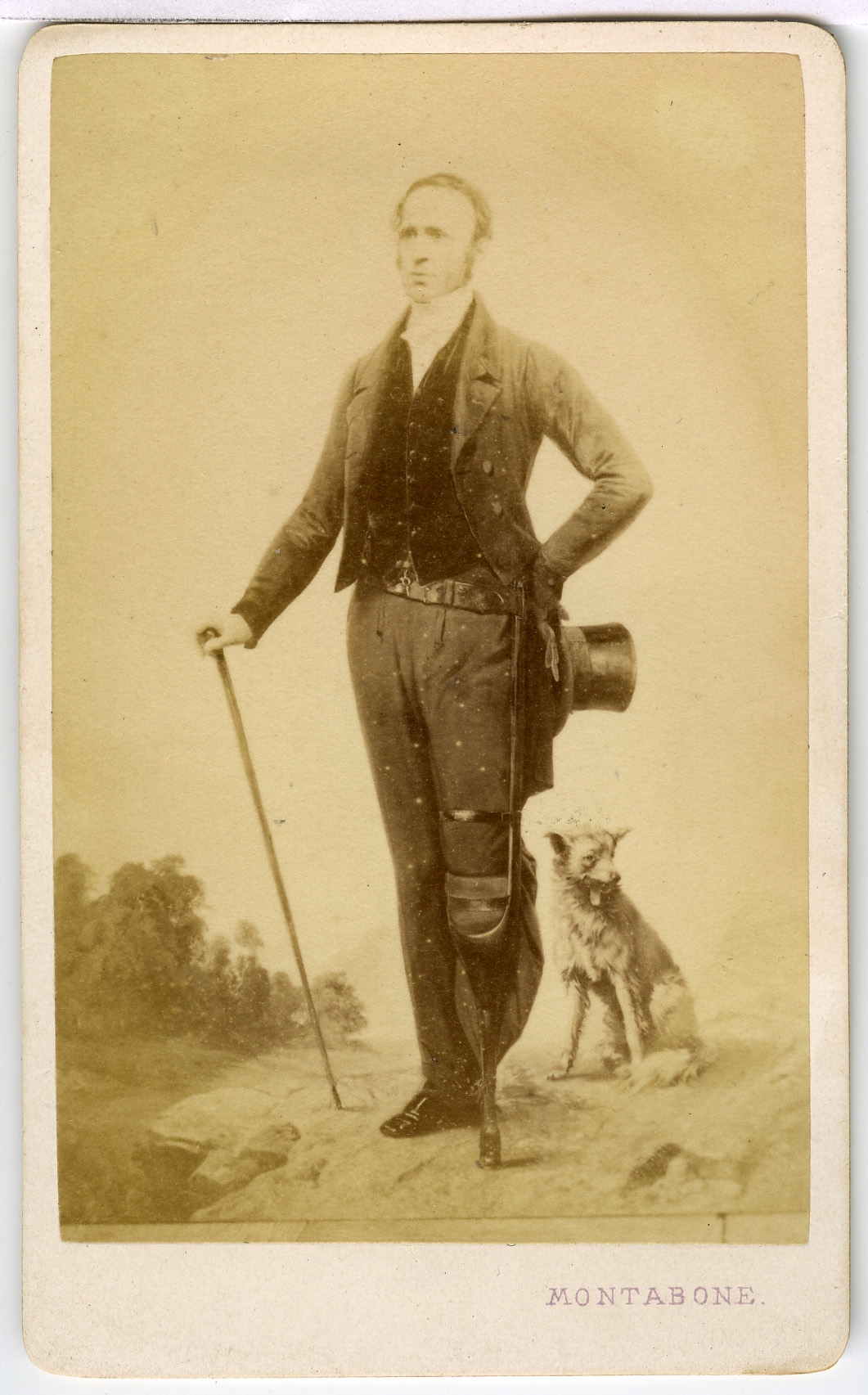

A portrait of Charles Beckwith (1789-1862), who lost a leg in the Battle of Waterloo in 1815 and later settled in the Waldensian Valleys of northern Italy, where he devoted his life to missionary and educational activities. He met several times with Lorenzo Snow in 1850. Courtesy of Archivio Fotografico del Centro Culturale Valdese (Torre Pellice), Editrice Claudiana and Gabriella Ballesio.

A portrait of Charles Beckwith (1789-1862), who lost a leg in the Battle of Waterloo in 1815 and later settled in the Waldensian Valleys of northern Italy, where he devoted his life to missionary and educational activities. He met several times with Lorenzo Snow in 1850. Courtesy of Archivio Fotografico del Centro Culturale Valdese (Torre Pellice), Editrice Claudiana and Gabriella Ballesio.

The Hôtel de l’Ours, where the missionaries resided, was located across the city’s central piazza from Palazzo Virtù, the residence of Charles Beckwith, an English gentleman and the Waldensians’ “great benefactor,” whose name, Snow reported to Brigham Young, “has an almost magical effect among the Protestants.” Snow presented Young’s letter of introduction to Beckwith shortly after arriving in Torre Pellice and procured “a ready and cheerful introduction to this gentleman, which resulted in several interviews.” [87] Although it is unlikely that Beckwith was familiar with the beliefs and claims of Mormonism, he would have been interested in the Mormons’ views on personal religious experience as well as their history of renewal, persecution, and proselytism. Beckwith, who believed that the Waldensians had deviated from the primitive church and apostolic life and attempted to synthesize tradition and renewal among the Waldensians, was apparently not apprehensive about the possibility that Mormon missionaries would knock on the doors of his Waldensian friends. He may have hoped that such social intercourse would encourage the Waldensians to return to their historical roots of witnessing to Catholics. Ultimately, Beckwith told the Mormon Apostle: “You shall receive no opposition on my part: and if you preach the Gospel as faithfully to all in these valleys as to me, you need fear no reproach in the ‘Day of Judgment.’”[88]

Because of Beckwith’s benign reaction, Snow and his companions were initially able to mingle freely among the Waldensian community. Snow reported that they were “treated with respect” by the clergy and that they attended and were sometimes permitted to speak at small religious meetings—called “Re-unions”—held in private homes.[89] All of these activities occurred before the pastors knew anything about the church. After a few of these meetings, the Mormon message “produced some little stir among the officials,” and in October 1850 the missionaries “received an invitation to attend a public meeting, and answer some questions relative to our mission. We did so, and found some of the most talented ministers present, with an evident desire to crush our efforts.”[90]

After a three-hour discussion on the principles of Mormonism, and building on “the favourable influence previously created among the people,” at least one man in the congregation, Jean Antoine Bose, left the meeting convinced that the missionaries had spoken the truth. Shortly thereafter, on 27 October, while the missionaries were attending Sunday services in a Waldensian Church, the minister “looked piteously upon us, and then at the congregation, to whom he said, in tones mournfully low, ‘Do not leave that dear church which is consecrated by so many glorious remembrances, and for which your fathers have died.’”

A few hours later Bose, who was in attendance at the same service, requested baptism and Snow happily obliged: “It was, therefore, with no small degree of pleasure I went down to the river-side to attend to this ordinance. . . . I rejoiced that the Lord had thus far blessed our efforts, and enabled me to open the door of the Kingdom in dark and benighted Italy. My brethren [Stenhouse and Woodard] stood on the river bank—the only human witnesses of this interesting scene. Having long desired this eventful time, sweet to us all were the soft sounds of the Italian, as I administered, and opened a door which no man can shut.” Snow added in his report of this event that “others have expressed their determination” to be baptized soon.[91]

Rethinking and Reorganizing the Work in Italy

Despite the avowed intentions of other Waldensians to follow Bose into the church, mission records show that very few actually did so in the period immediately following his baptism. The paucity of conversions in this early period puzzled the missionaries, imbued as they were with conviction of Mormonism’s veracity and superiority and with vivid memories of the rich harvest of souls reaped in England only a few years before. Their correspondence and journals reflect an ongoing process of introspection to understand and explain the underlying reasons for their relative lack of success. They identified repression of religious rights and intense loyalty to tradition as two obstacles to progress in missionary work. As they became more familiar with local conditions, the missionaries discerned two more factors: provincialism and poverty. To Snow’s mind, the geographical and political isolation of the Waldensians limited their thinking and made it difficult for them to fully grasp a message as profound as Mormonism: “They have had so little intercourse with other parts of the earth—so little knowledge of any thing beyond their own scenes of pastoral life, that it is difficult for them to contemplate the great principles of temporal and eternal salvation.”[92]

Although the missionaries had an occasional introductory chat with a leading citizen or a public debate with a local minister, they spent most of their time with the rural poor who invited them into their homes. In a letter to a fellow apostle, Snow attempted to dispel romantic stereotypes about Italy in order that church leaders might more clearly grasp the reality of their situation: “Think not, dear Franklin, that we are amid the marble palaces, nor surrounded by the choice productions of art which adorn many portions of this wondrous land. Here, a man must preach from house to house, and from hovel to hovel.” Many of these peasant homes, he added, lacked glass in the windows and fire in the fireplace due to scarcity of fuel. He implied in a later report that the stark poverty and subsistence lifestyle of the local people formed a great impediment to missionary work by diverting the attention of both men and women to material rather than spiritual concerns. “One long round of almost unremitting toil is the portion of both sexes,” he noted. “The woman who is venerable with grey hairs is seen laden with wood, or heavy baskets of manure, while travelling the rugged paths of the mountains. No drudgery here but what must be shared by the delicate female frame.”[93]

A photo of Torre Pellice in the 1880s after it became the political, religious, and industrial center of the Waldensian valleys. Clearly seen dominating the skyline in the background are Monte Vandalino and the prominent rock protrusion called Monte Castelluzzo on its left slope. Reprinted form Carlo Papini, ed., Come Vivevano:Val Pellice, Valli D'Angrongna e di Luserna fin de siecle (1870-1910) (Turin: Claudiana, 1980, 1998), image 54.

A photo of Torre Pellice in the 1880s after it became the political, religious, and industrial center of the Waldensian valleys. Clearly seen dominating the skyline in the background are Monte Vandalino and the prominent rock protrusion called Monte Castelluzzo on its left slope. Reprinted form Carlo Papini, ed., Come Vivevano:Val Pellice, Valli D'Angrongna e di Luserna fin de siecle (1870-1910) (Turin: Claudiana, 1980, 1998), image 54.

By mid-November 1850, only a few weeks after baptizing Bose, the Mormon missionaries began to reevaluate their strategy. Snow, acting in accordance with “the mind of the Spirit” (a phrase commonly used by the missionaries), decided to reorganize their activities. On Sunday, 24 November 1850, the three missionaries once again made the “tedious ascent”[94] up the slopes of Vandalino (“Mount Brigham”) to the same spot where they had organized the church two months earlier. Again hymns were sung and prayers offered, and Snow, “knowing the formidable character of the difficulties with which they must struggle,” ordained his two companions to the office of high priest. He designated Woodard “to watch over the Church in Italy” and prayed that Stenhouse’s way “might be opened in Switzerland for carrying forth the work of the Lord in that interesting country.”[95] A few days later, Stenhouse was on his way to Geneva to preside over the new Swiss Mission, while Woodard stayed in Torre Pellice to assume the presidency of the Italian Mission after Snow’s departure.[96]

In January 1851, while Snow was in Turin on his way to Geneva, he wrote Orson Hyde reflecting on his seven months’ residence in Italy. The overriding tone is one of ambivalence: on the one hand, admiration for the natural and man-made beauty that surrounded him physically, but on the other hand, disappointment at the tepid response and the meager results experienced by him spiritually. He captured the essence of the dilemma with terse eloquence: “Amid the loveliness of nature I found the soul of man like a wilderness.” He again delineated the multifaceted problems of poverty, parochialism, sectarian strife, and political oppression that diminished the elders’ capacity to win converts to their cause.

Yet, despite the general sense of melancholy, Snow expressed guarded optimism about the future of Italy as a country and of Mormon missionary efforts there. “O, Italy! hath an eternal winter followed the summer of thy fame . . . ? No! the future of thy story shall outshine the past, and thy children shall yet be more renowned than in the ages of old.” Confident that “Truth shall yet be victorious,” he predicts that “there is yet the blood of heaven’s nobility within the hearts of many” of Italy’s sons and daughters who will embrace “the tidings of Eternal Truth.” However, compared to his letters written just before and after arriving in Italy, one detects subtle and telling differences: the language is less exuberant, more cautious and measured, more tempered by the experience of the past seven months. The predicted growth of the church will occur, not immediately or dramatically, but “one day,” according to the “sure, though tardy working of the Gospel.”[97] Snow’s imagery conveys a sense of reduced though more realistic expectations for missionary work in Italy, emphasizing the substance rather than the amount of work accomplished, and the quality rather than the quantity of converts won.

While Snow was in Turin he arranged for the printing of two pamphlets after “much difficulty and vexation” due to the Sardinian government’s restrictions against public preaching and distribution of religious literature. The pamphlets were La voix de Joseph [The Voice of Joseph], which he began writing soon after his arrival in the valleys and which the British Mission made arrangements to have translated into French by a Professor from the University of Paris, and Exposition des premiers principes de la Doctrine de L’Eglise de Jesus Christ des Saints des Derniers Jours, a translation of his The Only Way to be Saved (originally published in 1841) which was completed through the “politeness of the French Mission.” He referred to the later pamphlet as The Ancient Gospel Restored in a letter to Orson Hyde but the pamphlet published in Turin was entitled Examination of the First Principles.[98] These pamphlets were eventually circulated in Piedmont and in the Swiss Cantons because of the “intimate connection between the Protestants here and in Switzerland.”[99]

Snow finished writing his letter to Hyde on 6 February 1851 when he arrived in Geneva. In the middle of a snowstorm, “scarcely knowing whether I was dead or alive,” he had crossed the Alps from Turin to Geneva with copies of the two missionary tracts stuffed in his trunk, pockets, and hat. He had stopped in Switzerland for a time to work with Elder Stenhouse and to arrange for the publication in Geneva (in order to avoid any further dealings with the Sardinian bureaucracy) of a second French edition of Exposition des premiers principes de la Doctrine de L’Église.[100] He was on his way to England to supervise the translation and publication of the Book of Mormon in Italian. After months of pent-up frustration stemming from the strictures of religious life in Italy, Snow could barely contain his feelings of relief and optimism upon arriving in Geneva: “I feel free, and in a free atmosphere and to prophecy good of switzerland.”[101]

Meanwhile Woodard, who was still living in the Hôtel de l’Ours in Torre Pellice and solely responsible for the missionary work in Italy, began pondering how he might better acquaint himself with the local people and thus be more effective in preaching to them. “I do not see an opening at the present moment,” he observed, “but I believe the Lord will enable me to be independent of the Hotel, and by that means I shall know more as to the true character of the inhabitants.”[102] At the same time, on the mountainsides surrounding Torre Pellice, the roots of the tree planted by the missionaries—to use Snow’s metaphor—were beginning to take hold in the alpine soil and would soon yield the first sizable harvest of the Mormons’ proselytizing campaign.

Notes

[1] Previous scholarly studies of the Italian Mission include Michael W. Homer, “‘Like the Rose in the Wilderness': The Mormon Mission in the Kingdom of Sardinia,” Mormon Historical Studies 1, no. 2 (Fall 2000): 25–62; Homer, “The Italian Mission, 1850–1867,” Sunstone 7 (May–June 1982): 16–21; James A. Toronto, “‘A Continual War, Not of Arguments, but of Bread and Cheese’: Opening the First LDS Mission in Italy, 1849–1867,” Journal of Mormon History 31, no. 2 (Summer 2005): 188–23; Diane Stokoe, “The Mormon Waldensians” (master’s thesis, Brigham Young University, December 1985); and Flora Ferrero, “L’emigrazione valdese nello Utah nella seconda metà dell’800” (Tesi di Laurea: Università di Torino, 1999).

[2] This account of the issuing of the 17 February 1848 proclamation and its impact in the Waldensian valleys and beyond is derived from the following sources: Augusto Armand Hugon, Torre Pellice: Dieci Secoli di Storia e di Vicende (Torre Pellice: Società di Studi Valdesi, 1980); Giorgio Tourn, Giorgio Bouchard, Roger Geymonat, and Giorgio Spini, You Are My Witnesses: The Waldensians across 800 Years (Turin: Claudiana, 1989), 165–67; Stephen Malan, “Autobiography and Family Record, 1893,” MS 5136, Church History Library, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (hereafter cited as Church History Library), Salt Lake City; Marie Madaline Cardon, autobiography, typescript, Family History Library, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (hereafter cited as Family History Library), Salt Lake City; Giovanni Luzzi, The Waldensian Church and the Edict of Her Emancipation, 1848–1898, Freemason’s Hall, (Turin: Claudiana, 1998).

[3] Malan, “Autobiography and Family Record, 1893,” Church History Library.

[4] Cardon, autobiography, Family History Library.

[5] Coccarda in Italian, a rosette made of ribbon and worn on the chest or hat.

[6] Luzzi, “The Waldensian Church and the Edict of Her Emancipation,” 23, 25.

[7] Roger Absalom, Italy Since 1800: A Nation in the Balance? (London: Longman, 1995), 25.

[8] Journal History of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (chronological scrapbook of typed entries and newspaper clippings, 1830–present, hereafter cited as Journal History), 29 April 1849, 2, Church History Library (from History of Brigham Young 849:71). See also Manuscript History of Brigham Young, 1847–1850, ed. William S. Harwell (Salt Lake City: Collier’s, 1997), 197.

[9] Journal History, 6 October 1849, 1.

[10] On this, see Armand L. Mauss, “In Search of Ephraim: Traditional Conceptions of Lineage and Race,” Journal of Mormon History (Spring 1999): 131–73; and Arnold H. Green, “Gathering and Election: Israelite Descent and Universalism in Mormon Discourse,” Journal of Mormon History (Spring 1999): 195–228.

[11] Lorenzo Snow, The Italian Mission (London: W. Aubrey, 1851): 14, 16.

[12] Millennial Star, 1 April 1852, 107–8. The Millennial Star was published by the Mormon Church in Liverpool and served the European members.

[13] Millennial Star, 1 October 1851, 301.

[14] Millennial Star, 1 May 1852, 153.

[15] Millennial Star, 1 April 1854, 206.

[16] Millennial Star, 25 March 1854, 191.

[17] Snow, The Italian Mission, 24.

[18] Snow, The Italian Mission, 8, 12.

[19] See, for example, Elder Thomas Margetts’ account of his efforts to proselytize among the Catholics in Genoa and the stiff opposition of local priests. Millennial Star, 20 August 1853, 555–58.

[20] Snow, The Italian Mission, 6, 7, 13, 17, 26; see also the observations of Woodard in Millennial Star, 19 February 1853, 127 and of Keaton in Millennial Star, 1 April 1854, 204–6.

[21] Snow, The Italian Mission, 20, 24–25.

[22] Snow, The Italian Mission, 16.

[23] Millennial Star, 1 October 1851, 302.

[24] Millennial Star, 15 January 1851, 26.

[25] Millennial Star, 1 April 1852, 107–8.

[26] Millennial Star, 24 April 1852, 142.

[27] Millennial Star, 13 November 1852, 602–3.

[28] The account of the missionaries’ travel to Italy is drawn from the following sources: Journal History, Church History Library; Snow, The Italian Mission; Eliza R. Snow Smith, Biography and Family Record of Lorenzo Snow, One of the Twelve Apostles of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Salt Lake City: Deseret News Co., 1884); chapter 11 of Franklin L. West, Life of Franklin D. Richards (Salt Lake City: Deseret News Press, 1924); and Peter “Ole” Olsen Hansen, Journal, typescript copy in author’s possession, courtesy of Fred Robinson Hansen.

[29] West, Life of Franklin D. Richards, 112–13.

[30] Snow, The Italian Mission, 5.

[31] Toronto, whose Italian name was Giuseppe Efisio Taranto, was a merchant seaman from Palermo, Sicily, who was baptized in 1843 in Boston. In 1845 he ingratiated himself to Brigham Young by contributing $2,600 in gold to the building of the Nauvoo Temple at a time when church funds were nearly depleted. Three years later, he helped drive Young’s cattle across the plains. In 1852, when Toronto returned to Utah from his mission to Italy, he lived with Young and even became known as “Joseph Young” until he married a Welsh convert and built his own home on First Avenue. His residence thereafter became a halfway house for many newly arrived immigrants. Toronto, like many immigrants of the time from Italy, was illiterate, and we therefore have only limited information about his family life and missionary experiences. Concerning Joseph Toronto, see James A. Toronto, “Giuseppe Efisio Taranto: Odyssey from Sicily to Salt Lake City,” in Pioneers in Every Land, ed. Bruce A. Van Orden, D. Brent Smith, and Everett Smith Jr. (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1997), 125–47; Toronto Family Organization, comp., Joseph Toronto: Italian Pioneer and Patriarch (Farmington, UT: Toronto Family Organization, 1983).

[32] Snow, The Italian Mission, 5; West, Life of Franklin D. Richards, 113–14; Hansen, Journal, 69.

[33] Hansen, Journal, 69.

[34] Snow, The Italian Mission, 5, 6.

[35] Snow, The Italian Mission, 6.

[36] Job Smith, Journal History, 29 December 1849, 2.

[37] Erastus Snow, Journal History, 29 December 1849, 2.

[38] Snow, The Italian Mission, 6.