The Golden Age of Church Expansion, 1971-85

James A. Toronto, Eric R Dursteler, and Michael W. Homer, "The Golden Age of Church Expansion, 1971-85," in Mormons in the Piazza: History of the Latter-Day Saints in Italy, James A. Toronto, Eric R. Dursteler, and Michael W. Homer (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2017), 351-382.

Following the division of the Italian Mission into two, the church in Italy continued gradually to consolidate its presence. The years 1971–85 marked a time of remarkable growth in church membership as social unrest and economic uncertainty impelled many Italians to question traditional values and seek new religious alternatives. As a result of this growth, Italian converts increasingly replaced foreign missionaries in leadership positions. At the same time, churchwide reforms brought about more regular interaction between General Authorities and local members, laying the foundation for expansion of church organization and infrastructure in Italy: the number of missions increased to four, construction of new chapels commenced, and the first two stakes were established.

“Anni di piombo, anni di battesimo” (Years of Lead, Years of Baptism)

The years between 1971 and 1985 were a tumultuous period when many Italians became increasingly disillusioned with the prevailing socioreligious norms, anxious for greater stability in their lives, and open to seeking reforms in the political arena and exploring options in the spiritual marketplace. Italy was in the throes of a rapid passage from less developed, rural society to one of Europe’s leading industrialized economies, and the resulting changes were deep, pervasive, and long-lasting: “The most recent history of Italian society is the unfolding . . . of a process of modernization that changed the social fabric so profoundly that it seems difficult to comprehend what the poor provincial Italy of the postwar period and the postmodern Italy of today might have in common.”[1] In the wake of industrialization, urbanization, and mass internal migration came widespread social unrest. The late 1960s, in fact, marked “the high season of collective action in the history of the Republic” as the militant student and labor protest movements posed a stiff challenge to Italy’s political and social structure, spreading “from the schools and universities into the factories, and then out again into society as a whole.”[2]

Compounding these problems, the early 1970s witnessed the worst economic downturn since 1929, bringing even greater hardship to Italians already struggling to make sense of a society seemingly turned upside down: “No sooner had Italy become one of the great industrial nations of the world than she found herself exposed to the icy winds of recession. The almost simultaneous occurrence of these two elements—transformation and crisis—had the most profound effect on the history of the Republic.”[3] The era’s indelible imprint on modern Italian society is evident in altered attitudes on divorce, abortion, and the role of women; on taboos about sexuality; on perceptions about political and religious authority; and on the nature of spirituality.

The 1970s also witnessed a surge of criminality that “without exaggeration can be defined as historic, reaching levels until then considered inaccessible,” with robberies reaching an unprecedented high in 1976 and homicides in 1982.[4] Hundreds of Italian citizens died as a result of violent crimes perpetrated by political extremists. Italians refer to this period of economic hardship, political strife, and social change as the anni di piombo—the “years of lead”—evoking the image of bullets and violence and the general tenor of upheaval and anxiety that characterized the times.

Turbulent forces in Italian society and geopolitical events in the international arena impacted the church’s evangelization in a number of ways. Mission records indicate that day-to-day proselytizing activities were often disrupted or abandoned as church members and missionaries were swept up in events beyond their control—eyewitnesses or victims of an array of crimes, confrontations, and physical violence during these years.

A small sampling of incidents recorded in the mission histories illustrates this. In 1972, President Jorgensen’s Alfa Romeo was stolen in Milan, so the mission decided to replace it with one that had “additional anti-theft devices.”[5] Later on, the windows on a new Fiat 127 driven by the assistants to the president were smashed and a spare tire taken, and two days later the car itself was stolen. At that point, the mission started parking all its vehicles in a commercial garage. But cars were not the only target of criminality: In Avellino, five men assaulted two missionaries, badly beating one of them, so the missionaries were instructed to go about their work in foursomes for a while.[6] In Rome, intruders suspected of having ties with extreme left-wing political groups broke into and ransacked the mission home on several occasions looking for money. Two members of the Rome Mission office staff were assaulted while leaving the bank with several thousand dollars in cash but were able to tackle the assailants and retrieve the money bag. On another occasion in Rome, two missionaries riding a bus were attacked and, in defending themselves, managed to overpower the thugs while being cheered on by other passengers.[7] In Milan, a shootout between a swarm of Italian police and two armed fur thieves broke out in front of the mission offices. Fortunately, there were no injuries to the office staff or president, “as everyone took to the floor.”[8]

The most notorious crime during the anni di piombo, and arguably in Italian history, occurred in the spring of 1978 when an Italian terrorist group, the Red Brigades, kidnapped and murdered former prime minister Aldo Moro. Police discovered his body in an area of Rome not far from the Trionfale LDS Branch meetinghouse. In the ensuing dragnet, Italian officers held two sister missionaries at gunpoint on two occasions while interrogating them and verifying their visas, a harrowing experience that left the young missionaries bewildered and badly shaken.[9]

On 2 August 1980, during the height of the vacation season in Italy, a neo-Fascist terrorist group set off a powerful bomb in the Bologna train station, killing eighty-five people and wounding hundreds more. Referred to in Italy as the strage di Bologna (Bologna Massacre), this attack also wounded three students from Brigham Young University who were touring Italy. President Felice Lotito of the Padova Mission went to Bologna immediately to coordinate the church’s participation with civil authorities, and missionaries and members in Bologna joined hundreds of other volunteers to help in the rescue and cleanup effort.[10]

Political banners during elections in Florence, May 1968. The Communist and Socialist Parties held powerful sway in Italian politics during the first few decades of LDS Church growth in Italy, creating difficulty at times for missionary work due to the church's American image and traditional opposition to leftist ideologies. Courtesy of Noel Zaugg.

Political banners during elections in Florence, May 1968. The Communist and Socialist Parties held powerful sway in Italian politics during the first few decades of LDS Church growth in Italy, creating difficulty at times for missionary work due to the church's American image and traditional opposition to leftist ideologies. Courtesy of Noel Zaugg.

Communism and Realpolitik: The Mormon Church’s Accommodation to Italian Politics

International tensions at times suffused and shaped the dynamics of church life, particularly those stemming from American efforts to thwart the worldwide expansion of communism. At a pragmatic level, the military draft in the United States during the Vietnam War affected the number of young men available for missionary service. Mission presidents in Switzerland and Italy reported that the draft brought about occasional reductions in their missionary force and that some cities had to be closed as a result. In addition, talk about politics was pervasive and passionate in Italy, and Mormon missionaries were often drawn into polemical encounters about US foreign policy and the church’s views on communism and the war in Vietnam.

For mission leaders, the problem of how to handle these volatile issues was complicated by the fact that sympathy for the Communist Party (the strongest in the Western bloc countries) was deeply rooted in Italian society and that many Italians saw no conflict between being both religious and communist.[11] In the early years of the mission, the policy was to ask potential converts, “Do you belong to the Communist Party?” If the answer was affirmative, then the missionaries would explain that the teachings of communism and the Mormon Church were incompatible.

American church leaders and missionaries in Italy, like most Americans during this time, viewed communism as a grave threat to religious and democratic values and feared that a shift of political power to the communists in Europe would bring an end to US influence, to religious freedom, and thus to Mormon missionary efforts. A 1978 report, with a hint of youthful hyperbole, captured the prevailing sentiment among missionaries: “Elections are today and supposedly the Communist Party has more possibilities than the others due to the ousting of the Christian Democratic candidate for corruption. If the Communist Party makes it in office, we can kiss Italy good-bye.”[12] Because Mormon missionaries proselytized extensively in cities like Bologna and Modena that were heavily communist, mission leaders were concerned that the church’s image as an American institution might make it an object of protests and demonstrations. But this kind of large-scale public opposition never materialized, due in part to the fact that church presence was still small and that the missionaries were counseled to stay away from rallies and parades.

As church leaders came to understand that Italian communism differed substantially from Soviet communism and that many Italians and other Europeans who professed allegiance to socialist ideals still believed in God, they changed the policy to allow for baptism of communists. European church leaders had begun expressing concerns about the writings and general conference talks of some Latter-day Saint General Authorities who had denounced socialism and called on church members to mobilize against its influence. During a general conference of the church in 1966, for example, President David O. McKay described communism as “the greatest Satanical threat to peace, prosperity, and the spread of God’s work among men that exists on the face of the earth.”[13] In 1968 a stake president in England wrote to church headquarters asking for clarification on the church’s position, noting that more than half of the members of his stake and many of the stake and ward leadership supported Socialist candidates and causes.[14] In response, the First Presidency and the Twelve, desiring to “make our hearers conscious of the fact that we are a universal church” and to teach the gospel “in a way that will not be offensive to other parts of the world,” decided that General Authorities should focus their remarks on basic principles of Mormon doctrine and avoid making “pointed attacks on politics” in their sermons.[15]

In other words, church leaders opted for political neutrality, deemphasizing ideological preferences in favor of a higher priority: church growth. They decided, according to one observer, that there was “more to lose by openly opposing the communists” than there was “to gain by maintaining what some leaders probably considered doctrinal purity.” Denouncing communism would “only have further identified [the church] as American—a profile greatly resented by many non-American members” in Italy and throughout Europe.[16] The church’s rethinking of its relationship with communism would prove in the long run to be beneficial for its integration in Italy and other European countries. A Latter-day Saint scholar of European history labeled this development a “breakthrough” that “paved the way for even more significant opportunities in the late 1980s”: winning respect from communist governments that subsequently allowed the church to make contact with members scattered throughout Czechoslovakia, to construct a temple in Freiberg, East Germany, and to commence missionary work for the first time in forty years in some areas of Eastern Europe.[17]

After this change in policy, mission presidents in Italy were instructed by the Quorum of the Twelve to avoid making statements criticizing communism,[18] and it became more common for Italians with communist sympathies or affiliation to join the church. For example, in 1968 during a street meeting in Bari, a tall young man named Felice Lotito, who was a semi-professional basketball player and a communist, confronted the Mormon missionaries and began to make derogatory remarks about American politics. The missionaries steered the conversation toward religion, challenging him to read the Book of Mormon and attend church, but he responded that he would go to their church only if they would attend a communist youth rally with him—and they did. Later the young man joined the church and eventually became one of the first Italian mission presidents and a director of the Church Educational System in Italy. Like many Italian and European church members, he continued even after his conversion to harbor personal concerns about US foreign policy and cultural hegemony. Not all communist converts to Mormonism fared so well, however. As they learned more of the harsh anti-communist statements that had been published by some church officials, some became disillusioned and left the church. But Lotito’s case illustrates the church’s historical pattern of confronting ideological dilemmas in the international arena and making adjustments when necessary to accommodate local realities in order to promote growth.

During the 1960s and 1970s, the uneasy rapport between Mormonism and Italian communism continued to impact mission policy and daily missionary life. As previously noted, the mission jettisoned Il Pioniere (The Pioneer) as the name of its newsletter when it was learned that it was also the name of a Communist Party newspaper. Bologna’s reputation (and the Emilia-Romagna region in general) as a communist stronghold influenced decision-making at several junctures in early mission history on issues such as where to hold conferences, the number and location of missionaries to place, and which cities to consider as headquarters for new missions (this played into the decision to select Padua instead of Bologna when a third new mission was formed in 1975).[19] Ivan Radman, a staunch anti-communist originally from Trieste who had emigrated to Australia before being called as Italy Milan mission president in 1974, received threatening notes from communists which “cut his mission one year short in Italy.” Due to concerns about his safety, Radman was reassigned to Christchurch, New Zealand, where he completed the final year of his three-year mission.[20]

On several occasions, mission activities were postponed or canceled to avoid potential confrontations with communists: for example, mission leaders called off the annual tradition of Christmas caroling at the Galleria in the center of Milan because of a communist rally in the adjacent Piazza Duomo. But some dangerous encounters inevitably occurred in the charged political atmosphere, including when two missionaries were reportedly beaten up, though not seriously hurt, “by a few unfriendly communists” in Sassari, Sardinia.[21]

Debate on politics and the church’s stance on communism naturally spilled over into relations among church members who often harbored sharply divergent views on these issues. A telling example of this debate appeared in a church report by an Italian clerk in Milan describing President Spencer W. Kimball’s August 1977 visit to Italy:

The historian of this district points out an error committed by the leaders of the Rome mission. Many daily newspapers [in Milan and Rome] reported the news that politicians, ministers, members of parliament, President Giovanni Leone, and even Catholic officials have been invited by letter to participate in the meeting with the Prophet on 18 August in Palazzo dei Congressi in EUR. “Only the communists,” one reads in the articles, “were excluded.” That exclusion constituted a grave error on the part of the leaders of the Rome mission since all men, no matter what political ideology they may espouse, have the right to receive the Gospel of Jesus Christ, as President Kimball stated during his discourse in Milan.[22]

The uproar in the media over the church’s affront to the communists led one church member to ask, “Why don’t we have mission leaders who understand our politics?” Another lamented that he was hard pressed “to explain the Church’s move to his work colleagues when he could not understand it himself.”[23] Taken together, these examples of the tension between religion and politics in emerging areas of the church outside the United States shed light on the ongoing struggle in the church to identify priorities and make course adjustments in an effort to internationalize its message, practices, and image.

An important trend in stabilizing LDS presence in Italy has been the "Italianization" of church leadership. By the 1980s, most of the church organizations were led by native Italian converts. This photo shows the teachers and leaders in the seminary program on the island of Sicily, circa 2006. Courtesy of James Toronto.

An important trend in stabilizing LDS presence in Italy has been the "Italianization" of church leadership. By the 1980s, most of the church organizations were led by native Italian converts. This photo shows the teachers and leaders in the seminary program on the island of Sicily, circa 2006. Courtesy of James Toronto.

An Era of Accelerated Church Growth

What significance do these historical developments hold in terms of how Mormonism and other new religious movements have emerged in Italy? As in the nineteenth century, sociopolitical ferment, exacerbated by economic hardship, created fertile ground for the Mormon Church to take root in Italy. Many church members noted in interviews that the anni di piombo marked a Golden Age in the new religion’s trajectory of growth when a large influx of individuals and young families embraced Mormonism. People from many walks of life—including spiritual seekers, students attending university, individuals and families who had emigrated to the North, young couples seeking clear spiritual guidance for marriage and child-rearing—cited a sense of societal drift, disillusionment with the religious status quo, and changing values in postwar Italy as key to their conversion.

Mission records provide abundant evidence of the heightened religious curiosity and—for new religious movements—opportunity of the times. The Rome Mission history includes the story of two missionaries who set out in 1976 for Agrigento in Sicily to find the leader of a twenty-five-member Pentecostal group that had broken away from the main congregation, found a Book of Mormon, and written to the mission home in Rome asking to be taught about Mormonism. During a harrowing journey the missionaries nearly ran out of gas, only to find that a power shortage had darkened the city. After purchasing some gasoline, they had a flat tire and, without a spare, were obliged to sleep in the car overnight and have the tire repaired the next morning. Upon their arrival in Agrigento, “they found the people open for the Gospel and especially the group that had written. Many were touched by the Spirit, and spiritual experiences were many. There will be members before too long in that city.” A short time later, two elders were transferred to Agrigento to open missionary work there, and a branch was subsequently established.[24]

Church statistics identify a surge in convert baptisms that bolstered membership rolls, particularly during the late 70s and early 80s, solidifying the church’s foundations in Italy and laying the groundwork for greater local autonomy. From 1965 to 1971, when the Italian Mission was divided after six years of proselytizing, total church membership reached approximately 1,500; during the following six-year period from 1971 to 1977, church membership quadrupled to more than seven thousand. In response to this growth, two new missions were created: Italy Padova in 1975, and Italy Catania in 1977. Starting with twenty-two missionaries in 1965, the church’s missionary force had grown to nearly six hundred full-time missionaries in 1978.

During the same year, Charles Didier, supervisor of the Europe West region, announced that the missions in Italy, and the Italy Padova Mission in particular, were leading Europe in convert baptisms. During the first three years of the Padova mission, nearly every branch doubled or tripled its membership, and with an eventual average of nearly fifty baptisms per month, the overall number of members increased from 915 to 1,961. Italians from the Padova Mission serving as full-time missionaries jumped from five to twelve, and construction or remodeling began on the first four chapels in the mission.

The Italy Milan and Italy Rome Missions (the names were changed from Italy North and Italy South in 1974) also reported accelerated levels of conversion during these years. In 1976, for example, Italy Milan recorded 408 baptisms, 150 more than the previous year. In a February 1977 zone conference (with “Fruitful February” as the theme), President John Halliday read a letter from the First Presidency congratulating the missionaries and members for their work done in 1976 and expressing concern that these baptisms be quality conversions, not just baptisms.[25] In 1977, Italy Rome reported that the average number of baptisms per month was higher than ever: 101 baptisms by the end of March compared to 43 during the same period the previous year, and 64 baptisms in April—a record-breaking month for the mission.[26]

Developments in local congregations. While turbulent economic and sociopolitical conditions set the stage for more interest in new religious movements in Italy, coinciding developments within the church itself, both locally and internationally, also contributed to this period of expansion. In many local congregations, the number of Italian converts reached a point of critical mass so that leadership roles increasingly devolved from young foreign missionaries to adult converts. Two positive effects flowed from this Italianization of local authority: members became increasingly involved in helping the full-time missionaries in recruiting their fellow citizens, and the public perception of the church as an American religion began to evolve toward a more Italian image and identity that contributed to greater acceptance in society.

Local branch records provide a detailed portrait of the optimistic spirit that characterized these halcyon days of church growth and the manner in which members and missionaries worked energetically and innovatively to promote conversions in emerging congregations.[27] In the Bari Branch of the Puglia District in southeastern Italy, annual histories from 1978 to 1983 document a steady flow of new converts, with baptismal services scheduled nearly every week for multiple individuals, including numerous entire families. Sunday sacrament meetings and district conferences—involving several branches in the Puglia region—had higher-than-ever attendance. The clerk noted a particularly momentous day in June 1979: the move from the old crowded meeting hall to a large, newly remodeled chapel with spacious grounds on Via Cancello Rotto. Attendance at sacrament meeting in following weeks was 120 persons, including many investigators, and participation by members in the weekly chapel cleaning duties was excellent. Now district conferences could be held in a church building rather than a hotel, and attendance reached nearly 250.

Collaboration between members and missionaries was thriving, and the response from non-Mormons reflected widespread curiosity and openness to alternative religious ideas in southern Italy. Many open houses and missionary activities were held with positive results. In March 1980, for example, “for the first time in Bari, the citizenship was invited to know the church. Every member brought an investigator. At the end of the evening, eighty investigators were counted—a great success.”[28]

In May 1980 the long-standing practice of holding worship services on both Sunday morning and afternoon was replaced with a consolidated three-hour meeting block. This was intended to reduce the amount of travel and meeting time to enable members to spend more time at home with their families. In Bari this resulted in “a large increase in attendance.”[29] The branch provided a rich variety of social activities each year, and church members engaged regularly in broader community causes by performing humanitarian service. In one case, the older children in the branch visited handicapped children in a hospital and gave them sweets prepared by their mothers.

Minutes of district conferences indicate that burgeoning growth led mission leaders, as early as September 1981, to encourage the members in Puglia to begin preparing to become a stake. But at the same conference, leaders also began to express open concern about the other side of the conversion coin—retention—that is necessary to sustain “real growth.” One church official admonished each member present to be a better example—“a true light”—and to reactivate within the next year at least one family who had left the church. This was an acknowledgement that retention problems were taking a heavy toll on church participation. In fact, the twin adversaries of church growth—low retention and high migration—prevented the church units in Puglia from becoming a stake until sixteen years later (1997) despite the dynamic growth in convert baptisms described here. The same pattern characterizes church-planting efforts in other areas of Italy as well.

The Vicenza Branch histories from 1977 to 1983 show another church unit, this time in northeastern Italy, undergoing a vibrant process of growth and change. The records provide a glimpse of branch members earnestly collaborating to promote missionary outreach and a spirit of unity and friendship in their religious community. They worked together to renovate a newly purchased and more spacious villa to accommodate a growing membership, and there was a full calendar of activities each year: visits to cultural sites and art museums, talent shows, poetry contests, dinners, dances, bocce competitions, soccer matches against the Verona Branch, and socials to celebrate Carnevale, 1 May (Labor Day), and other national and religious holidays. A Christmas dinner with the local American LDS branch, held at the nearby US Army base, became a pleasant annual tradition, despite language difficulties and the strangeness for the Italians, of a traditional American custom: the white elephant gift exchange. A note from March 1978 mentions the division of the Padova District into two, evidence of a maturing leadership base and commitment among church members in the region.

Branch leaders also organized some creative approaches for reactivating members who had dropped out and for recruiting new members. A branch library was established to lend Latter-day Saint books and literature donated by members, and in 1980 the branch began publishing a monthly newspaper to be sent to both active and less-active members as a means of addressing the problem of retention. Later that year, as a proselytizing activity, the branch sponsored a choir competition held outdoors on a Sunday evening in the popular Querini Park. The clerk recorded that “many people, attracted by the singing, stopped to listen. In this way the missionaries had an opportunity to talk with some persons and make some teaching appointments.”[30] On another occasion, a chess and checkers tournament was held in the church’s chapel, and members of the checkers club of the local Railroad Workers union were invited to participate. Afterwards, the investigators from the club, all of whom received a gift copy of the Book of Mormon and a ceramic picture inscribed with biblical verses, invited their new Mormon friends to visit them and continue the association.

But the Vicenza members—while pursuing a full agenda of family, church, and social activities—were not immune to the political winds swirling across Italy at the time. A note written in April 1980, at the height of the contentious national debate about abortion, records that a special meeting, open only to families in the LDS Church, was held “for the purpose of clarifying some ideas about birth control, sexuality, and related problems.”[31] Local church leaders generally refrained from giving official directions or trying to influence the voting of church members on these controversial sociopolitical questions. On an informal, ad hoc basis, as in the case of the Vicenza Branch cited here, meetings were sometimes convened to discuss contemporary issues like divorce and abortion. Two long-time Italian church leaders recalled: “Some members met and discussed those issues, privately and unofficially. In all circumstances the church proceeded very cautiously and, when requested, responded by citing the official statements written in the church handbook [which oppose abortion and divorce in general but allow for exceptions]. The members debated these issues and some of them did disagree among themselves, but they were normally not discussed within our regular church meetings.”[32] The position of the church in Italy at the time was that members should support the political process, engage in civic dialogue, and vote according to their individual conscience.

Increasing internationalization prompts organizational reform. Churchwide developments also impacted the mission in Italy during this time of accelerated growth. With rapid expansion into many new countries during the 1950s and 1960s came the gradual realization that “international Mormonism could not be merely a duplication of Great Basin [Utah] Mormonism.” David O. McKay traveled widely outside the United States and presided over the internationalization of the church. He noted the disparity that often existed between church practices rooted in American soil and the actual needs of church members from multiple cultures around the world: “The concepts we get from reality are entirely different than the concepts we have from reports received.”[33] Beginning with his administration, but gaining momentum under his successors, the First Presidency and the Twelve Apostles implemented organizational changes designed to bring senior church leadership into closer contact with the lives of church members and to narrow the gap between perceptions at church headquarters and realities in the field.

In 1965, twelve regions were organized throughout the world, each supervised by one of the Apostles, with help from an Assistant to the Twelve or a member of the First Council of the Seventy. In 1967, another cadre of leaders joined the ranks of church administration: Regional Representatives, who generally were former mission or stake presidents living their normal lives at home, assigned by the Twelve to conduct training in their local area (but sometimes further afield). One Regional Representative, Dean Larsen, described the task of developing a unified worldwide organization as “perhaps the greatest single challenge” that the church was facing. He noted that local leaders “come from an almost infinite variety of circumstances,” with varying levels of education and administrative experience, “yet they are expected to learn and to administer a code of inspired principles, procedures, and policies that are determined by the General Authorities of the Church.”[34]

To supplement the official handbook of instructions, authorities traveled more widely to train and become better acquainted with leaders and issues at the local level. Other major organizational changes designed to strengthen cohesion among an increasingly diverse membership base were the designation in 1984 of thirteen areas worldwide, each presided over by a three-member presidency who would live in the geographical area assigned to them, thus providing closer proximity and developing deeper rapport with local members; and in 1995, the creation of the position of Area Authority Seventy (the name changed to Area Seventy by 2005), replacing Regional Representatives and allowing Area Presidencies to delegate to indigenous leaders at the national level many duties that were formerly reserved for the Twelve Apostles.[35]

The effort to internationalize and decentralize administration in order to respond to realities rather than reports (as President McKay observed) had to be balanced with the need to maintain a degree of uniformity and consistency throughout the church. Over time, the tension inherent in this organizational balancing act produced both benefits and liabilities, facilitating growth in some ways but inhibiting it in others.

In Italy, the impact of these reforms became apparent in the increasing number of church representatives coming to the mission, especially during the 1960s and 1970s. Besides regular visits by members of the Twelve, Assistants to the Twelve, and Regional Representatives,[36] there was a steady stream of officials from Salt Lake City to help local leaders develop programs for children (Primary), youth (Mutual Improvement Association), and women (Relief Society), along with specialists to assist with public relations, financial procedures, and translation and publication of curriculum materials. In this early period of the church’s development the Patriarch of the church, Eldred G. Smith, made several tours of the missions in Italy as well as other countries around the world. Despite his advanced age he traveled incessantly, visiting many branches and giving patriarchal blessings to hundreds of Italian converts who otherwise would have had to postpone this important church rite until years later when the first Italian stake was established. During one week in August 1976, for example, he gave sixty patriarchal blessings in the Padova Mission alone.[37]

The convening of the church’s first area conferences in Europe—in Munich (1973) and Paris (1976)—brought Italian Mormons together with thousands of fellow European converts.[38] The conferences afforded members the desperately needed chance to become acquainted in a more personal way with leaders whom they knew only superficially through writings and speeches and to feel connected to a broader, international community that was impossible to envision in their small, struggling branches. At both conferences, along with cultural and social events featuring choirs and folk dance groups from throughout Europe, speeches focused on topics that reflected the contemporary concerns and priorities of the senior church hierarchy, who encouraged members to remain steadfast in the face of social isolation, widespread misinformation, and anti-Mormon sentiment.

During the Munich conference, held in the hall that hosted Olympic events the previous year and attended by fourteen thousand church members (“the largest group of Latter-day Saints ever assembled on continental Europe.” President Harold B. Lee warned members about splinter groups and cultists who “make spurious claims as to chain of authority” and who are working “to lead you astray.”[39] A frequent topic, intended to counteract the American image of Mormonism, was the universal nature of the church, which Lee said was “not confined to one nation, or to one people.”[40]

Gordon B. Hinckley, an Apostle, focused on the problem of retaining converts, acknowledging the loneliness that many of the assembled church members would feel again upon returning “to your homes, to your employment, to the small branches from which many of you come, to the association of those who do not see as you see and do not think as you think and who are prone to ridicule.” He reassured them that they were not alone, that “it was ever thus” for Christian disciples, and that “while there may be trouble and travail, there will be peace and comfort and strength.”[41]

Three years later, on 31 July and 1 August 1976, 4,200 members from France, Italy, Portugal, Spain, and French-speaking Switzerland and Belgium gathered for an area conference in Paris, the first of five area conferences held that summer throughout Europe. President Spencer W. Kimball exhorted church members to increase the number of full-time missionaries, to stay in their respective countries and strengthen the church there rather than emigrating to the US, and to devote themselves to becoming dedicated fathers and mothers in order to preserve the traditional family unit. Italian Latter-day Saints who attended these international conferences retained vivid memories of their long-term impact in invigorating the spiritual life of the church community and fostering a sense of pride in Latter-day Saint identity.

Official Visits Galvanize the Church

In addition to the impact of the area conferences, the personal visits of Lee and Kimball to Italy played a pivotal role in bolstering the morale and resolve of church members, improving the public image of Mormonism, and laying the foundation for organizational changes that would prove decisive in the Italianization of the LDS Church and its emerging presence in Italian life.

For members and missionaries in Italy, 22 September 1972, marked a milestone in church history: the first visit by a president of the church since its founding in 1830.[42] On that day, a large throng of church members and missionaries greeted President Harold B. Lee, Elder Gordon B. Hinckley, and their wives, Joan and Marjorie, as they arrived at the Rome airport on the last leg of a two-week tour to England, Greece, and the Holy Land. The grueling schedule of travel, discussions with government officials, press conferences, and church meetings had taken its toll on Lee. He arrived in Italy with his physical strength at “a serious low ebb” (in his words), suffering from severe back pain and exhaustion.[43] Health concerns notwithstanding, Lee and his entourage embarked on the next whirlwind round of public appearances.

Following a tour of Rome, they held a meeting for church members during which the two church authorities spoke to the male priesthood holders while their wives held a session for the women. The group traveled to Santa Severa, a resort on the Tyrrhenian coast near Rome, to address about three hundred Mormon youth gathered for a three-day conference. Later in the day they visited a branch meeting and then met with Italian-speaking missionaries. Subsequent stops on the Italy itinerary, during which they intermingled church meetings with visits to historical and cultural sites, included Florence and Pisa.

Lee and his travel companions arrived in Milan on Monday, 25 September, for the final events of their Italian sojourn. An evening press conference did not turn out as expected: a grand total of one journalist showed up to meet the Mormon prophet. He was Michele Straniero, a colorful and at times controversial figure, who was not only a writer for the Turin newspaper, La Stampa, but also a poet, songwriter, and historian of Italian folklore and religion. This may explain why, at this early stage when new religious movements like Mormonism were not widely known in Italy, he was the sole respondent to the church’s invitation to the press conference. He took full advantage of an extraordinarily intimate interview setting by questioning the two church authorities for an hour. In the years following his encounter with Lee and Hinckley, he published several articles and a book about the church’s theology and history.[44]

A meeting with church members and investigators from across northern Italy followed the press conference, and for many who attended, the up-close encounter with President Lee proved a galvanizing moment in their decision to become or remain a Latter-day Saint. A typical example is a church member’s reflection on the bracing impact that the Milan conference exerted on his spiritual journey to a new faith: “It was hard to leave the Catholic Church, but when I heard the gospel taught by the missionaries, it was as if I had known it for a long time. It was like a window of light opening up for me. My mother told me I was betraying my faith. But I was deeply touched and changed during a meeting with President Lee in 1972. I felt profoundly that he was a prophet, and this gave me great courage and hope.” Another church member, moved by the words of the church president, threw his cigarettes out the window on the train ride back to Padova and vowed to join the small local branch.

Throughout that night, dozens of missionaries from across the Italy North Mission began arriving at the Milan Centrale train station for an early-morning appointment with their church president. With no money for hotel rooms in their meager monthly budgets, they found make-do accommodations: some slept on the steps inside the station, some crowded together on the floors in missionary apartments, and when the space became too tight, one even managed to doze off in the bathtub with his overcoat on. Held in the Dow Chemical auditorium on Via Le Petite, the mission conference with President and Sister Jorgensen and 150 missionaries lasted one hour, from 7:30 to 8:30 a.m. Due to a pressing travel schedule, only Lee and Hinckley had time to speak.

Hinckley chose a timely topic for this audience: the discouragement that missionaries often experience in coming at a young age to a foreign culture, wrestling with the language, enduring rejection by the people, and coping with difficult living conditions. He recounted his own experience with discouragement as a young missionary in Preston, England, when his father advised him, “Forget yourself and go to work.” He then read Jesus’ words “He that loseth his life for my sake shall find it.” Missionaries must learn to be obedient, he noted, adding that “I just have one hope, that each of you will be the kind of missionary your mother thinks you are.”[45]

In his remarks, Lee emphasized broad themes, touching on the overall message of the church and addressing some of the thorny social issues in Italy. He urged missionaries to stay focused on teaching Christian principles and to avoid being drawn into discussions of peripheral issues, such as those that the Italian journalist Straniero inquired about, including gender roles and sexuality. Obviously aware of the social and political turmoil in Italy, Lee underscored the centrality of the traditional family in the church’s outreach efforts, explaining why proselytizing methods must continue to focus on Italians’ concerns about the growing threats to family life:

Here [in Italy] we have made great efforts as you folks know. We are now embodying that in your missionary plan as a door opener because most families today are struggling with problems. Families are being threatened: birth control, abortion, and population control by mandate of government to limit the number of children that any couple may have or to penalize them if they have more than a certain number of children. This is one of the most damnable things that can be done by Satan! They ask us in every interview, as they did last night, what our position is with regard to birth control, or with regard to abortion, or with regard to over-population. We must say always that the whole solution to these problems is to do as the Prophet Joseph Smith answered when asked in Nauvoo how he was able to control his 20,000 saints who were there. He said, “I teach them correct principles and they govern themselves.” Our job is to teach correct principles to our people. . . . That’s the message—not to try to condemn, nor try to limit by law, but to teach them the principles of self-control.[46]

This forthright Mormon emphasis on family life, articulated by Lee in Italy and a few years later under a brighter media spotlight by his successor, Spencer W. Kimball, resonated during the anni di piombo with many Italians who were deeply troubled by the disintegration of traditional family values. The message of family solidarity, bolstered by church programs such as family home evening, home teaching, and genealogy/

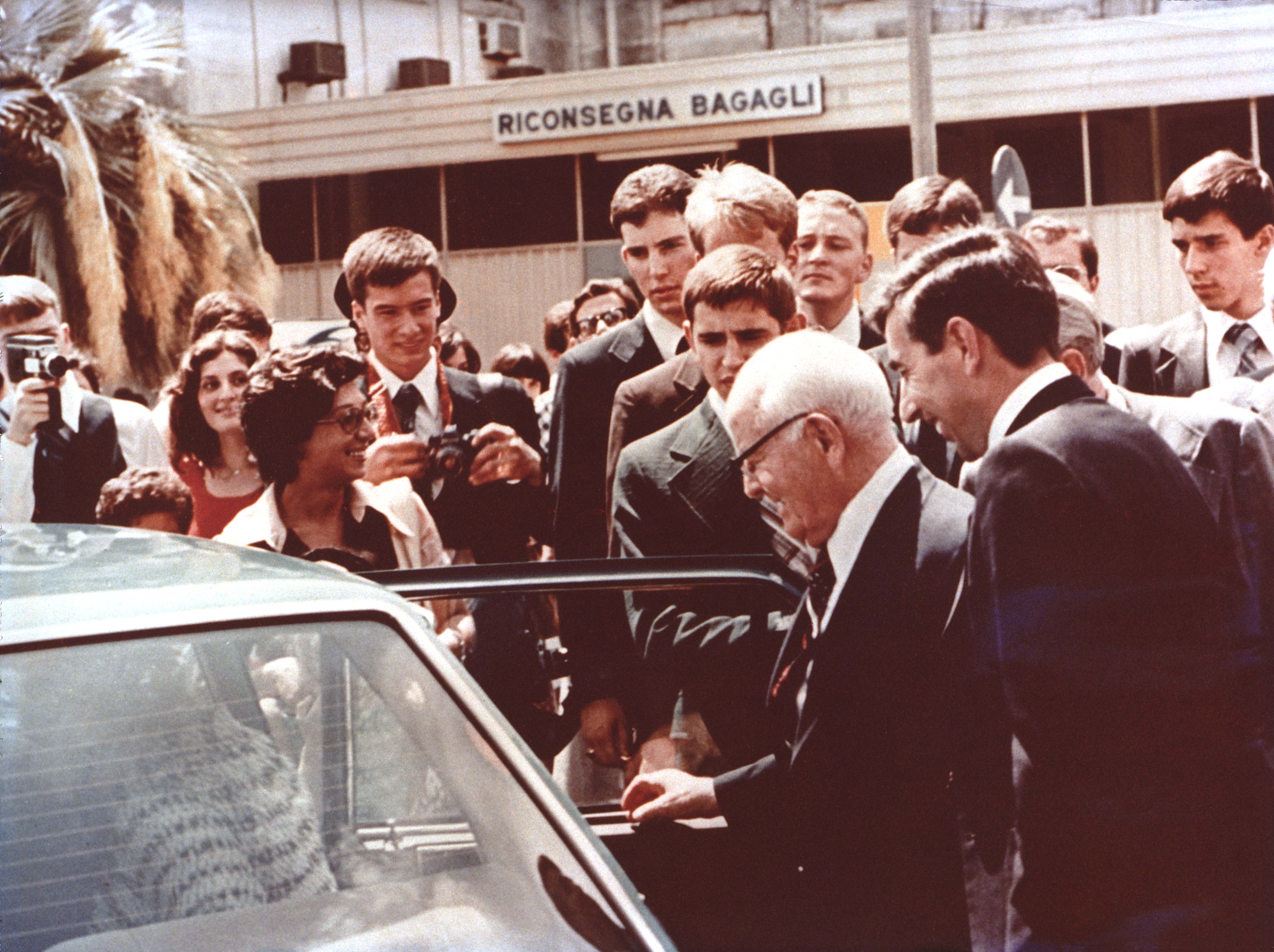

On 16 August 1977, five years after Harold B. Lee’s groundbreaking visit to Italy, his successor as church president, Spencer W. Kimball, flew into Milan’s Linate airport for a four-day, four-city mission tour, only one leg on a tour of seven European countries.[47] Accompanied by his wife, Camilla, Kimball was greeted at every airport arrival by sign-waving, ecstatic crowds of church members. Well-wishers pressed forward to experience the mystique of the Mormon prophet—to be near him, present him with gifts, and shake his hand. A lucky few managed to sneak in a baccetto—kissing his cheeks in the traditional Mediterranean greeting of affection and friendship.

During the five years between the two presidential visits, the church’s profile in Italy had undergone significant transformation. Perhaps most telling of this altered reality for the church were the size of the audiences for Kimball’s public appearances and the intensity of the press coverage. Total church membership had increased dramatically, a fact that did not go unnoticed: “I have been in Italy many times in my life,” Kimball told one conference gathering, “but this is the largest crowd of Latter-day Saints I have ever seen in Italy and it pleases me greatly.”[48] Increased media attention was due in large measure to recent organizational developments that created a more sophisticated capacity in the field of public relations.

The Public Affairs Department of the church was established during Lee’s brief tenure (1972–1973), with Gordon B. Hinckley leading the pioneering effort to communicate more effectively with an expanding membership and to manage more professionally the church’s image. Under the Kimball administration, the department dramatically expanded and diversified its electronic media activities. During the late 1970s and early 1980s, the church purchased numerous local and international broadcast facilities and set up one of the world’s largest television satellite networks to broadcast speeches and conferences directly to Latter-day Saint chapels worldwide.[49]

The intensive publicity and press coverage for Kimball’s tour of Italy was largely a product of this heightened emphasis on media relations. In contrast to the one journalist who attended Lee’s press conference five years earlier, many of the local and national media outlets reported on Kimball’s visit. The government-owned national television station, RAI, produced a documentary on the church and its presence in Italy and broadcasted it to an estimated ten million Italians during prime time. Two national magazines carried positive articles about Mormonism in Italy. As a result, the church conferences were well-attended and the words of the Mormon prophet widely disseminated. Church leaders in Italy reported that President Kimball was on national TV and radio and in the newspapers and that his visit stirred great interest.

President Spencer W. Kimball arrives at the Catania airport on a visit to the missions in Italy in 1977. Courtesy of James Toronto.

President Spencer W. Kimball arrives at the Catania airport on a visit to the missions in Italy in 1977. Courtesy of James Toronto.

In each city, Kimball’s schedule included two conferences per day in addition to the private meetings and press interviews: one open to the public, and one just with full-time missionaries. At the Milan conference, held in Hotel Michelangelo near the Stazione Centrale, about eight hundred members and investigators assembled to hear the president. The mission historian noted coverage by the Cronaca di Milano and other newspapers, calling it the “first fruits” of the new public communications department of the mission. The next evening’s conference, held at the Hotel Orologio in Abano near Padova, attracted a standing-room only crowd of over 1,100, fanning themselves with their printed programs to fend off the sultry August heat. The Palazzo dei Congressi in EUR was the site of the conference in Rome on 18 August, which attracted about one thousand people and media coverage by many print journalists and RAI.

Church leaders in Catania had just a little over two days to organize and publicize the conference in Sicily: it was not included on the original itinerary, but Kimball insisted on adding a fourth day of travel and meetings to allow him to visit the remotest church units as much as possible—a gesture deeply appreciated and long remembered by church members in southern Italy. Despite the short notice, about two hundred members and missionaries greeted the church dignitaries at the airport on 19 August, and an audience of 430 people gathered in the Cinema Odeon in downtown Catania to hear the Mormon prophet preach.

At every public appearance, speaking without notes for up to ninety minutes in his distinctive, raspy voice (the result of throat cancer surgery), the octogenarian president reiterated a simple message directed as much to the Italian media and society at large as to the growing but still fledgling Latter-day Saint community: the church is an international, not American, organization that encourages its members to be loyal, contributing citizens in their home countries. He counseled the members to “sustain and support the laws and authorities of the country where you live,” to seek after all good things, including music and the arts, and to contribute positively to civic life in the communities where they lived. He counseled full-time missionaries not to get involved in political discussions or politics of any type. “With these teachings in mind,” the president added, “we feel governments everywhere should open their doors to our missionaries.”[50] Kimball reiterated that strong traditional family ties form the foundation of the church and of productive societies and that missionary and genealogy work are vital to the church’s purpose. He pointedly addressed one of the contentious issues of the day in Italy, calling divorce “a horrible, terrible thing” and suggesting that if individuals married properly and followed Christ’s teachings, then divorce and its ill effects in society would diminish.[51]

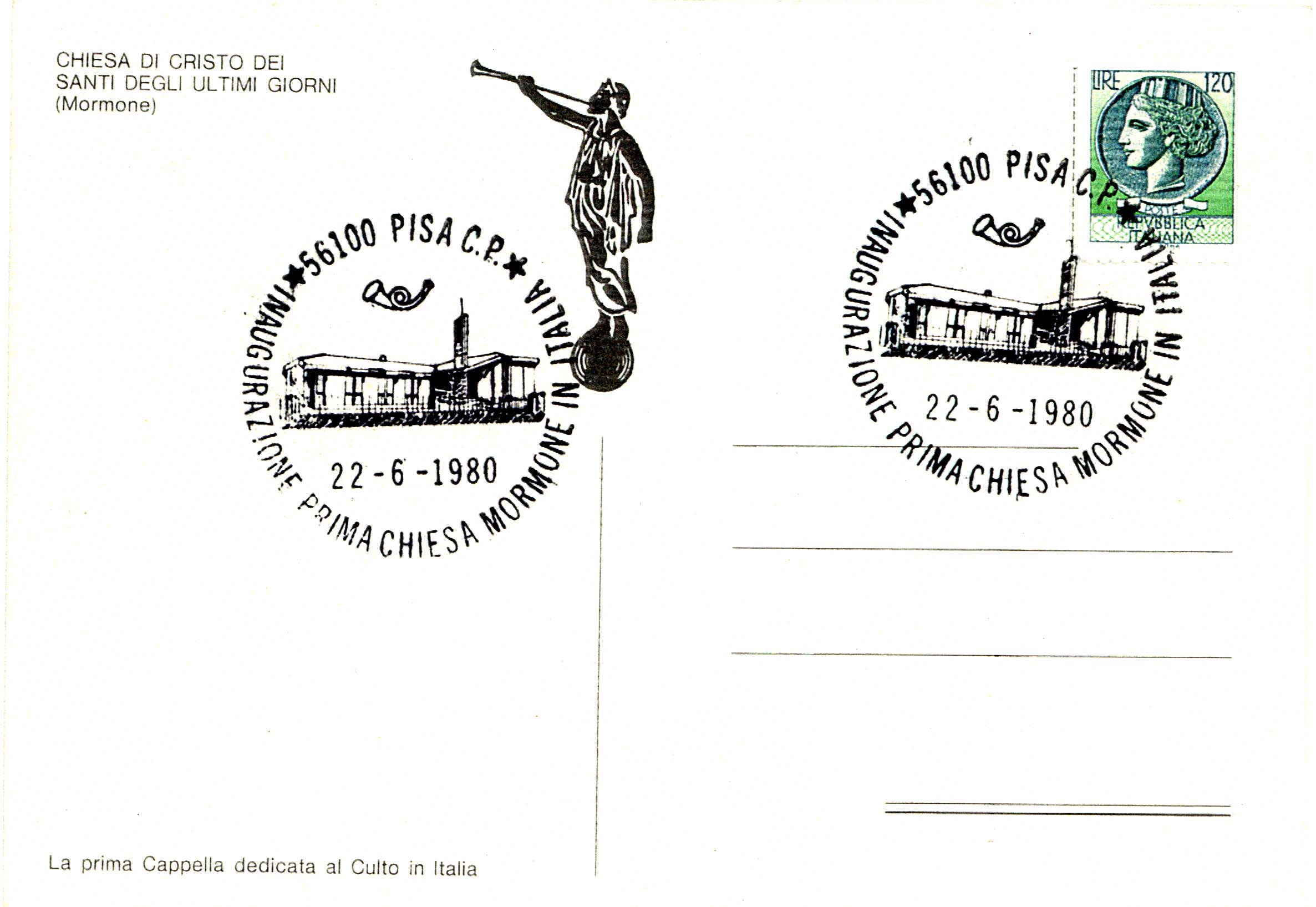

Postcard commemorating the June 1980 dedication of the LDS chapel in Pisa-the first one constructed in Italy after the reopening of the mission. On the reverse side, the stamp creating for the occasion by the Italian postal service. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Postcard commemorating the June 1980 dedication of the LDS chapel in Pisa-the first one constructed in Italy after the reopening of the mission. On the reverse side, the stamp creating for the occasion by the Italian postal service. Courtesy of Church History Library.

While Kimball’s eloquence in public speaking and his boldness in addressing sensitive social issue were noteworthy, perhaps the most enduring legacy of his visit to Italy flowed from the warmth and charisma of the man himself. Written and oral accounts of the time clearly show that observers were deeply moved by the self-effacing, down-to-earth, affable personality of the Mormon leader. He seemed to be indefatigable and irrepressibly optimistic in his efforts to promote the message of Mormonism and the establishment of the church worldwide. Many Italian church members recalled his trademark personal touch in dealing with individuals even while surrounded by the chaos of public celebrity. At Venice’s Marco Polo airport, about three hundred people showed up to welcome the Kimball party and then swarmed around him after he cleared customs. He slowly made his way through the crowd, accepting the small gifts offered him, pausing to oblige photo requests, and shaking the hand of nearly every person there. A member in Rome who met Kimball said, “I’ll remember that firm handshake and steadfast look into my eyes the rest of my life.”[52]

The benefits of Kimball’s sojourn in Italy began to accrue immediately and continued to reverberate in following years. The church’s emphasis on public relations during this period, especially electronic media, facilitated missionary outreach and church growth in Italy. Starting with the massive buildup to Kimball’s visit, mission leaders began putting together a more sophisticated organization that would reach out further to raise the church’s profile and address misconceptions about Mormons in Italian society. In addition to ongoing appearances by Mormon celebrities, performing groups, and athletic teams,[53] missionaries working with Italian members began to find increasing success in airing their message over local and national media outlets.

For example, in 1977 the Italy Catania Mission recorded that “Public Communications has been growing rapidly” and that they had been contacting television stations and sending news releases to newspapers in every city within the mission boundaries. Members and missionaries tried an innovative tactic—offering free advertising to radio stations in exchange for broadcasting daily spots about the church: “We stamp the radio and time of coverage on cards we pass out. . . . There will be a 5–15 minute presentation by the Church. We get radio coverage, and the station gets publicity, with its name going to over 500 people a week.” As a result of these efforts, the Ragusa branch secured weekly airtime on a local TV station, and the Catania branch obtained “14 minutes of prime time daily” on radio stations in the area (with Italian members responsible for preparing the programs).[54] President Leopoldo Larcher reported that the missionaries had set up a small studio in the mission home for creating audio and video recordings that were then distributed to radio and TV stations. These media programs, according to Larcher, had made the missionaries local celebrities and resulted in more teaching appointments and baptisms.[55]

The Rome Mission reported similar results from their public relations campaigns in Caserta, Pozzuoli, Naples, and Rome. In the latter city, the largest privately owned television station allotted thirty minutes each Wednesday to the Mormons for a call-in talk show that drew positive public response. During one segment on alternative religions the host, a missionary from Foggia named Giovanni Carlo Dicarolo, “talked about the role of the Church with the youth, and many people called in to ask questions. GBR has been very pleased with our participation on the show, so they asked the Church to prepare two 2-hour segments, one for Christmas, and the other for New Year, to be repeated during the day around those holidays.” Other public relations activities during this period included the distribution of professionally produced public service spots (part of the church’s Homefront series initiated in 1972) to 879 radio and 142 TV stations in Italy, the first broadcasts of LDS general conference sessions and Music and the Spoken Word on Italian radio and TV, and visits from representatives of the church’s media arm, Bonneville International, to advise mission leaders on how to work with ltalian media to broadcast LDS programming.[56]

The Milan Stake Center, one of approximately one hundred LDS Chapels that dot the Italian landscape today. Of these one hundred chapels, fifty are rented properties and fifty are church properties (30 contracted, 20 remodeled). Photo courtesy of James Toronto. Data courtesy of Centro Servizi, Milan.

The Milan Stake Center, one of approximately one hundred LDS Chapels that dot the Italian landscape today. Of these one hundred chapels, fifty are rented properties and fifty are church properties (30 contracted, 20 remodeled). Photo courtesy of James Toronto. Data courtesy of Centro Servizi, Milan.

Both church members and Kimball himself felt the impact of his time on Italian soil. Members began to notice greater awareness of Mormonism among their Italian neighbors. As one church leader observed: “Already because of the news coverage that we have received, many people have come to know the Mormon Church. The other night a policeman stopped us and his only reason for stopping us was to find out about the church. Then we went on a little further and another man asked us when our prophet was going to return to Italy.”[57] The expectations of an energized church membership were heightened, and efforts toward the creation of stakes and the construction of chapels and a temple intensified based on statements by Kimball and other senior church leaders. President John Grinceri of the Padova Mission, reflecting this enthusiasm, felt that the church in Italy would never be the same again after Kimball’s visit. Based on the average number of conversions in his mission each year and the development of strong Italian leadership, he predicted the creation of four stakes within five years. He cited for support Apostle Bruce R. McConkie’s assertion at a mission presidents’ seminar that “President Kimball’s visit will be the launching pad for a great acceleration of the work in this land.”[58]

On his part, Kimball was deeply moved—“astounded” was the term he used—by his Italian experience. He hinted about the prospect of a temple for Italy and predicted in one conference that the highest echelons of church leadership would eventually include Italians, both women and men: “I believe that the day will come when you will have leaders of the church from Italy, men and women in leadership positions of the church for all the world, not just for Italy. They are the people that you are going to find this month, next month, and you have already found.”[59]

A constellation of broad historical and institutional factors contributed to Mormonism’s accelerated growth during the period 1971–85: social and economic turmoil, changing attitudes in the religious economy, greater international awareness and outreach in church organization, and increasing Italianization of local leadership. It would be a mistake, however, to ignore the personal charisma of religious leaders at the grassroots level in shoring up human relationships, individual identity, and group solidarity—intangible factors that are crucial to the long-term viability of emerging religious communities.

While overly optimistic predictions about high rates of conversion and church growth—whether in 1850, or 1966, or 1977—have consistently foundered on the shoals of religious reality in Italy, it is also true that the 1970s and early 80s witnessed a noteworthy acceleration in convert baptisms and an expansion of church organization and infrastructure that laid the foundation for Mormonism’s increasing integration into Italian society. Challenges related to rapid growth became a pressing, albeit welcome, dilemma for the church, and it is no coincidence—given Kimball’s favorable impression of the Italian church and the demonstrated competence and commitment of a growing core of Italian members—that in the few months and years following his visit to Italy came significant developments in quick succession: construction of the first chapel in Italy (Pisa, 1980), the establishment of a regional office to supervise administrative affairs in the Mediterranean (Milan, 1980), the rapid expansion of youth programs such as the Church Educational System (CES) and Scouting, and the creation of the first two stakes (Milan, 1981, and Venice, 1985). The establishment of a stake is a benchmark in LDS Church planting—a tangible sign in Mormon life of the senior hierarchy’s confidence in local leaders and of the local church’s increasing maturity and self-sufficiency.

Notes

[1] Marino Livolsi, ed., L’Italia Che Cambia (Scandicci: La Nuova Italia, 1993), 3–4.

[2] Paul Ginsborg, A History of Contemporary Italy: Society and Politics 1943–1988 (London: Penguin Books, 1990), 298.

[3] Ginsborg, A History of Contemporary Italy, 351.

[4] Marzio Barbagli, quoted in Livia Turco, I Nuovi Italiani: L’immigrazione, i preguidizi, la convivenza (Milan: Mondadori, 2005), 20.

[5] Italy Milan Mission, Rapporto Storico del Italy North Mission, 1972, manuscript history and historical reports, 11 January 1972, LR 4141-2, Church History Library.

[6] Italy Rome Mission, Rapporto Storico, 1974, manuscript history and historical reports, 3 October 1974, LR 4142-2, Church History Library.

[7] Italy Rome Mission, Historical Events, 1978, manuscript history and historical reports, 3 June 1978, LR 4142-2, Church History Library.

[8] Italy Milan Mission, Rapporto Storico, 1976, manuscript history and historical reports, 19 February 1976, LR 4141-2, Church History Library.

[9] Italy Rome Mission, Historical Events, 1978, manuscript history and historical reports, 3 June 1978, LR 4142-2, Church History Library.

[10] Italy Padova Mission, Historical Events, 1980, manuscript history and historical reports, 2 August 1980, LR 15015-3, Folder 1, Church History Library; Lynne Hollstein Hansen, “Growth, Blessings Come to Italy Padova Mission,” Church News, 17 January 1981, 13.

[11] On communism in Italy in this period, see Giuseppe Mammarella, L’Italia contemporanea: 1943–1998 (Bologna: il Mulino, nuova edizione 2000), 1–2, 437–38; Ginsborg, A History of Contemporary Italy, 290–91; and Silvio Lanaro, Storia dell’Italia repubblicana (Venezia: Marsilio, 1992), 414–35.

[12] Italy Rome Mission History, manuscript histories and historical reports, 16 June 1978, Church History Library.

[13] David O. McKay, in Conference Report, April 1966, 109. For a detailed discussion of Mormonism’s evolving stance on communism, see Gregory Prince and William Wright, “Confrontation with Communism,” in David O. McKay and the Rise of Modern Mormonism (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2005).

[14] Similarly, a study by LDS scholar Wilfried Decoo found that the majority of Belgian church members baptized in the 1960s and 70s had socialist backgrounds and left-leaning political views. For details see Wilfried Decoo, “Mormonism in a European Catholic Region: Contribution to the Social Psychology of LDS Converts,” BYU Studies, 24, no. 1 (1984), 61–77.

[15] Prince and Wright, David O. McKay and the Rise of Modern Mormonism, 375–77.

[16] J. Michael Cleverly, “The Church and la Politica Italiana,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 13, no. 1 (Spring 1980): 107.

[17] Douglas F. Tobler, “Church in Europe: 20th Century,” http://

[18] Cleverly, “The Church and la Politica Italiana,” 107.

[19] The new mission was originally announced as the Bologna Mission, then subsequently changed to the Padova Mission (see Church News, 22 March 1975, 6, and 5 April 1975, 15); also John Grinceri to James Toronto, e-mail, 9 July 2012.

[20] John R. Halliday, oral history, 1983–84, interviewed 29 August 1983 by Alma Heaton. BYU Archives, BYU Alumni Association Emeritus Club, 7. UA OH 113; and Grinceri to James Toronto, e-mail, 9 July 2012.

[21] Italy Rome Mission, 29 December 1977, Historical Record, 1977, manuscript history and historical reports, LR 4142-2, Church History Library.

[22] Italy Milan Mission History, manuscript histories and historical reports, 16 August 1977, Church History Library.

[23] Cleverly, “The Church and la Politica Italiana,” 107.

[24] “Eventi Storici,” Italy Rome Mission History, 11 December 1976, Church History Library.

[25] Italy Milan Mission, Rapporto Storico, 1977, manuscript history and historical reports, 14 February 1977, LR 4141-2, Church History Library.

[26] Italy Rome Mission, Historical Events, 1977, manuscript history and historical reports, LR 4142-2, Church History Library.

[27] The material that follows is drawn from two sources: Registro Storico, Historical records and minutes, Bari Branch, Italy Catania Mission, Church History Library, LR 18375-3, and Registro Storico, manuscript history and historical reports, Vicenza Branch, Italy Padova Mission, Church History Library, LR 15310-2.

[28] Registro Storico, Historical records and minutes, Bari Branch, Italy Catania Mission, 29 March 1980, LR 18375-3, Church History Library.

[29] Registro Storico Historical records and minutes, Bari Branch, Italy Catania Mission, 27 May 1980, LR 18375-3, Church History Library.

[30] Registro Storico, manuscript history and historical reports, Vicenza Branch, Italy Padova Mission, 25 May 1980, LR 15310-2, Church History Library.

[31] Registro Storico, manuscript history and historical reports, Vicenza Branch, Italy Padova Mission, 19 April 1980, LR 15310-2, Church History Library.

[32] Names withheld, Email to James Toronto, 9 July 2012.

[33] Prince and Wright, David O. McKay and the Rise of Modern Mormonism, 372, 374.

[34] Richard O. Cowan, “The Seventies’ Role in Worldwide Church Administration,” in A Firm Foundation: Church Organization and Administration, ed. David J. Whitaker and Arnold K. Garr (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2011), 579.

[35] Cowan, “The Seventies’ Role in Worldwide Church Administration,” 578–86.

[36] See Italy Rome Mission, manuscript history and historical reports, LR 4142-2, Church History Library.

[37] Italy South Mission, manuscript history and historical reports, 14 December 1972, LR 4142-2, Church History Library; and Italy Padova Mission, manuscript history and historical reports, 21 and 28 August 1976, LR 150152, folder 1 (Italy Padova Mission, 1975–1977), Church History Library.

[38] The discussion on the European area conferences is derived from “News of the Church,” Ensign, November 1973 and October 1976. Other area conferences were held between 31 July and 8 August 1976 in Helsinki, Copenhagen, Dortmund, and Amsterdam.

[39] This was a fairly common problem in some areas with newly emerging church units, where records reveal numerous instances in which Church leaders excommunicated individuals who sought to arrogate leadership authority and to win the loyalty of church members.

[40] Doyle L. Green, “Meeting in Munich: An Experience in Love and Brotherhood,” Ensign, November 1973, 83.

[41] Green, “Meeting in Munich,” 79–80.

[42] The material on President Lee’s visit to Italy is based on the following sources: Italy South and Italy North Missions, manuscript histories and historical reports, Church History Library; Florence Branch, historical records and minutes, LR 28702, Church History Library; Francis M. Gibbons, Harold B. Lee: Man of Vision, Prophet of God (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1993); Sheri L. Dew, Go Forward with Faith: The Biography of Gordon B. Hinckley (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1996); “Italy, Italia,” Ensign, August 1973, 27–29; and the website of the Italy Milan Mission, www.italymilanmission.com. A discrepancy exists in the historical record concerning the date of Lee’s arrival in Rome: some sources report it as 22 September, others as 23. We have cited the date provided in the primary source material, the Rome Mission history.

[43] Francis M. Gibbons, Harold B. Lee: Man of Vision, Prophet of God (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1993), 466.

[44] Michele Straniero, I Mormoni. Leggenda e Storia, Liturgia e Teologia dei Santi degli Ultimi Giorni (Milano: Mondadori, 1990).

[45] Italy Milan Mission, Rapporto Storico del Italy North Mission, 1972, manuscript history and historical reports, 25 September 1972, LR 4141-2, Church History Library.

[46] Italy Milan Mission, Rapporto Storico del Italy North Mission, 1972, manuscript history and historical reports, 25 September 1972, LR 4141-2, Church History Library.

[47] On Kimball’s Italy tour, see mission manuscript histories and historical reports, Church History Library, for the Catania, Padova, Rome, and Milan missions; LaVarr G. Webb, “Pres. Kimball Ends Tour of 7 Countries,” Church News, 3 September 1977, 3; “Prophet Is a Main Attraction in Italy,” Church News, 17 September 1977, 5; and John Grinceri Papers, Church History Library.

[48] “Prophet Is a Main Attraction in Italy,” Church News, 17 September 1977, 5.

[49] James B. Allen, “Technology and the Church: A Steady Revolution,” Deseret Morning News 2007 Church Almanac (Salt Lake City: Deseret Morning News), 120; Sherry Pack Baker and Elizabeth Mott, “From Radio to the Internet: Church Use of Electronic Media in the Twentieth Century,” in A Firm Foundation: Church Organization and Administration, 339–60; and Dew, Go Forward with Faith, 318.

[50] LaVarr G. Webb, “Pres. Kimball Ends Tour of 7 Countries,” Church News, 3 September 1977, 3.

[51] LaVarr G. Webb, “Pres. Kimball Ends Tour of 7 Countries,” Church News, 3 September 1977, 3.

[52] Lavarr G. Webb, “Pres. Kimball Ends Tour of 7 Countries,” Church News, 3 September 1977, 3.

[53] See, for example, “Soccer Team Aids Missionary Work,” Church News, 31 August 1974, 5; Hack Miller, “Baseball Fever Is Aid to Missionary Efforts,” Church News, 31 August 1974, 5.

[54] Italy Catania Mission, manuscript history and historical reports, 2 August 1977, LR 16847-3, Church History Library.

[55] John A. Forster, “Church Enjoys Steady Growth in Italy,” Church News, 5 August 1978, 5.

[56] See Italy Rome Mission, manuscript history and historical reports, 5 May and 30 October 1978, and 14 October and 19 November 1980, LR 4142-3, Church History Library; and Italy Catania Mission, manuscript history and historical reports, 19 June and 20 October 1978, and 18 January 1981.

[57] Italy Padova Mission, 20 August 1977, historical events, 1977, manuscript history and historical reports, LR 15015-2, Folder 1, Church History Library.

[58] John Antony Grinceri, Report of Mission to the First Presidency, Papers, MS 19022, Church History Library; Italy Padova Mission, Historical Events, 1977, manuscript history and historical reports, 20 August 1977, LR 15015-2, Folder 1, Church History Library.

[59] Grinceri, “A Mission President from Down Under,” 61, and Report of Mission to the First Presidency, Papers, MS 19022, Church History Library.