Emigrating to the "Land of Ephraim"

James A. Toronto, Eric R Dursteler, and Michael W. Homer, "Emigrating to the 'Land of Ephraim,'" in Mormons in the Piazza: History of the Latter-Day Saints in Italy, James A. Toronto, Eric R. Dursteler, and Michael W. Homer (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2017), 137-176.

During a twenty-one month stretch from February 1854 to November 1855, seventy-three Waldensians who had converted to Mormonism left Piedmont in three separate groups for Utah. Branch records indicate that during the life of the mission, seventy individuals were excommunicated for a variety of reasons, including negligence, bad conduct, infidelity, evilness, immorality, apostasy, unbelief, criticism, nonchalance, cowardice, lying, deceit, and “at [the member’s] own request.”[1] Emigration and excommunication eventually reduced Mormon membership by almost 85 percent. While this development sapped the strength of the church in Italy, the immigrants contributed to the building of the increasingly multinational church in Utah.

Mormon emigration from the valleys was certainly not unique. The overpopulation, grape disease, and potato rot in the valleys had produced by the mid-nineteenth century a “noteworthy flux of emigration.”[2] While the Mormon missionaries were preaching the “gathering” and baptizing but also excommunicating converts, more than 450 persons were abandoning the valleys each year for France, Switzerland, and the Near East. Despite these drastic conditions, the Waldensian Church moderator vehemently opposed sponsoring a program of emigration because he feared that its members would abandon their cultural and ethnic heritage if they left the valleys.[3]

This void provided the Mormon missionaries with an opportunity to teach the Waldensians not only about the restored gospel but also instruct them concerning the advantages of emigration and living in Utah. The confluence of the nineteenth-century Mormon doctrine of gathering and the economic crisis created both opportunities and problems for missionary efforts: it increased the “spirit of inquiry” in the valleys about Mormonism and brought in new converts, but it also generated shallow conversions rooted in emigration fever rather than spiritual experience. Those who joined the church for the “loaves and fishes” often became disgruntled with Mormon emigration policies, and many eventually left the church or were excommunicated for apostasy when their plans to leave for America could not be realized.

Mormon Program of Emigration

The Mormon program of emigration was one of the central themes of Lorenzo Snow’s pamphlet La Voix de Joseph.[4] It contained glowing accounts of Utah as a spiritual, social, and economic utopia. The pamphlet intones with Victorian flourish that in July 1847 the pioneers found “a beautiful valley” where “all is stillness. No elections, no police reports, no murders, no wars in our little world. How quiet, how still, how peaceful, how happy, . . . Oh, what a life we live! It is the dream of the poets actually fulfilled in real life. Here we can cultivate the mind, renew the spirits, invigorate the body, cheer the heart, and ennoble the soul of man. . . . Here, too, we all are rich—there is no real poverty.” Snow added that the church had established a “Perpetual Emigrating Fund” for the emigration of the poor: “Many thousand dollars have already been donated for this purpose, . . . [and] this Fund has been so arranged as to be increased to millions, by which the poor and virtuous among men can be assisted, and with perfect assurance lift up their head and rejoice, for the hour of their deliverance is nigh!”[5]

Snow’s description was reinforced when the First Presidency published its Ninth General Epistle in April 1853, instructing all church members to gather to Utah. Leaders emphasized that the “Perpetual Emigrating Funds are in a prosperous condition,” although “but a small portion is available for use this season.” It also encouraged members to contribute to the fund to help “the Saints to come home. And let all who can, come without delay, and not wait to be helped by these funds, but leave them to help those who cannot help themselves.”[6]

In addition, the writings of other missionaries make it clear that this idealized view of Zion and the importance of emigration were continually propagated. The first public announcements of Mormonism posted by the missionaries in Turin contained information about emigration to America. John L. Smith wrote, “I feel to rejoice with the prospects of returning to Zion, the only place on earth where righteousness and peace are to be found.”[7] Jabez Woodard, after recounting scenes of persecution and oppression, stated, “I tell the Saints to make every preparation to flee as soon as the way opens.”[8] Woodard recorded in his journal that during a meeting of the Saints in Switzerland he “spoke upon the journey across the plains and the progress of a faithful saint from year to year. I told them that in 20 years I would be richer than the richest inhabitant that would then be found in Geneva.”[9] Keaton noted the sense of anticipation and hope that these teachings instilled in the members: “The Saints are increasing in faith and knowledge, and they rejoice in the glorious hope of one day assembling with the body of the Church in Zion.”[10]

This message resonated with many Waldensians, who were anxious to emigrate and had an “ardent desire to shed their old world identity and be reborn to a new life. . . . They craved a new identity and a new life.”[11] Daniel Tyler noted that “the emigration of the poor from that place [Piedmont] has awakened a spirit of inquiry, and the Spirit of the Lord is moving upon the minds of the people in some places, and Elder Francis expresses himself as having a strong hope of doing a good work the coming season.”[12] Nevertheless, given the surrounding socioeconomic reality in the valleys, the problem of emigration fever was sometimes exacerbated by the missionaries’ often zealous promotion of the doctrine of gathering based on a quixotic view of Zion in the American West.

Managing Unreasonable Expectations

While it is true that the church’s policy at the time was to bring the elect of Israel from throughout the world to the “Valleys of Ephraim” in Utah, it was also the case that the missionaries created problems for themselves by fostering unrealistic expectations for emigration, thereby attracting those Waldensians with material concerns. Sometimes the missionaries promoted the idea of emigration to Zion as a means of eliciting interest in Mormonism and showing its superiority to other religions. But missionaries and church leaders eventually realized that such an approach had inherent flaws, and they were obliged to take measures to address them.

One of the main difficulties was that the Perpetual Emigrating Fund did not have sufficient money to bring all the poor Saints to Zion, and therefore clarifications about the purpose and conditions of emigration had to be made. Tyler, commenting on those who sought baptism as a means to emigrate to America, stated that “when they were told that they could not be received on such terms, and that we wanted none except those who wished to serve God, and build up His kingdom, and were ‘willing to toil’ for its advancement, as well as their own, they went away sorrowful.”[13] Francis summarized the dilemmas of poverty and emigration:

Our numbers are very small there [Italy] at present; some of the strongest have been obliged to go to France in search of employment, and some have returned to the Waldensian Church, in their poverty, for the loaves and fishes, while others have desired to be cut off because they have not been emigrated. The few that are left . . . earnestly pray for their deliverance, and often say they would be willing to walk all the way to Liverpool (excepting the crossing of the channel) if the servants of the Lord could furnish them the means to cross the ocean, to go to Zion.[14]

The mission records noted a widespread impulse to seek economic and social advancement outside of Italy: the traditional problem of converts attracted by economic opportunity. The missionaries reported that in the Waldensian valleys there were “a great many lovers of emigration [who] join the church expecting to get free emigration to America.” They also noted that Protestant ministers, thinking that we tempt the people to join our Church with emigration to the Valley, have opened emigration to Algiers, to oppose us, and this winter, the ministers have offered several families of the Saints a free passage there to leave the Church.”[15]

Francis eventually “cut off” six members who, he discovered, had converted only for emigration: “One of these customers told me plain, that if he thought we should not emigrate him, he would never come to meeting again.”[16] Daniel Tyler observed that emigration fever was also endemic in Switzerland: “I found that the spirit of emigration exceeded any thing I ever had witnessed, some having found their way into the Church with no other view than to get to America. . . . Many of the peasantry, thinking that our only desire was to swell our numbers, came and offered themselves for baptism; stating that, as they had no property to detain them, they could be ready to emigrate at a week’s or day’s notice.”[17]

This issue was certainly not unique to Waldensian converts. In the April 1855 general conference, Brigham Young spoke at length about those who “embrace the Gospel for the sake of the loaves and fishes.” His opinion was that “a great many” converts came into the church solely “to be free from the iron hand” of political and economic oppression: “Many embrace the Gospel, actuated by no other motive than to have the privilege of being removed from their oppressed condition to where they will not suffer. They will embrace any doctrine under the heavens if you will only take them from their present condition.”[18] Later that year he wrote to Orson Pratt, president of the European Mission in Liverpool, expressing concern about the number of emigrants who left the church after their arrival in Utah.[19]

Eventually, church leaders in Italy and Switzerland began to take a more cautious approach, acknowledging that problems existed and tempering their rhetoric about the doctrine of gathering. Daniel Tyler stated that his “short experience on the Continent has taught me that the spirit of emigration prevails to a great extent, both in and out of the Church, and I wish the brethren to instruct the Saints, that they should not emigrate without counsel from proper authority.”[20] The economic havoc that descended on the valleys in the mid-1850s served to galvanize the emigration efforts, impelling members to hasten their preparations for departure and fanning the flames of the heated debate in Waldensian society over emigration.

The Waldensian clergy was well aware that these new converts intended to emigrate from the valleys. In the spring of 1853, Pastor Jean Jacques Vinçon of Pramollo parish reported that “there have been meetings of Mormons held in Pramollo this winter. But only one head of household has declared himself for the sect, and if he goes to California everyone would be happy since that man is the son of a father who did not have a good reputation of his living and the brother of a man who was for many years incarcerated in prison in particular in Sassari for ten years.”[21] On 28 October, La Buona Novella republished an article, which first appeared in a Paris newspaper, which observed there were Mormon missionaries in Piedmont “to take people to America. We love religious liberty for all; but if it is true that the Mormons teach immorality and polygamy, we do not believe that they have the right to be tolerated.”[22]

1854 Emigration

After Lorenzo Snow’s departure from the Waldensian valleys, Jabez Woodard directed the affairs of the Church and eventually recommended to Church leaders in Liverpool which families he believed were prepared to immigrate. When Church agents in Liverpool received sufficient applications, they chartered a vessel and the agent notified passengers (through their leaders) concerning when they should arrive in Liverpool and the cost of their passage.

While some members were extremely poor, it would be a mistake to conclude that all converts were without means or that emigration was their primary motivation for joining the church. In fact, one historian has described Mormon converts in Italy as “economically better off than the average Waldensian of the day and none were in dire poverty.”[23] They included landowners in the narrow mountain valleys where land was scarce and some families had occupied the same property for centuries. Thus the prospect of having access to property in a new land with more economic opportunities must have been enticing. They also understood that land sales would help them underwrite their own journeys to the United States as well as assist the church to maintain branches in their valleys after they left.

Within a few months of their conversions, these converts began preparations to leave their overcrowded valleys in Piedmont and to emigrate to Utah. Woodard noted that one convert “sold all he possessed, to prepare for Zion, but I need not say how immensely the value of his property was diminished, while others of the brethren who were dependent upon daily labor, no longer find employ where the crops fail on all sides.”[24] The recollections of some family members, recorded many years after arriving in Utah, that they were unable to sell their family property before leaving may have some factual basis.[25] But Italian land records indicate that the first families who emigrated in 1854–55 were able to sell their lands prior to leaving Piedmont.[26]

On 22 December 1852, Barthélemy Pons sold his home and pasture in Angrogna (Borgata Pons) for 7,000 lire; in September 1853, Philippe Cardon sold his home in Prarostino (which he had purchased in 1838) for 5,000 lire; Jean Daniel Malan sold his home and pasture in Angrogna for 500 lire. And in December 1853, Jean Bertoch sold his family’s two-story home (which was also designed to shelter livestock) and adjoining cropland, located on steep mountainsides above San Germano Chisone in Borgata Gondini to Gioanna Bertalot, for 2,200 lire.[27] In January 1854, Bertoch also sold a field he used for farming located farther up Val Chisone, in Pomaretto, for 300 lire.[28] In addition, Jean Pierre Stalle, Jean Michel Rostan, David Roman, and Michael Beus sold their properties before departing their villages.

It is not surprising that these families, who were able to dispose of their properties, were selected by Woodard to emigrate first. Nevertheless, many emigrants were assisted by the Perpetual Emigrating Fund, even though they had previously contributed funds to the church. But many more people applied for church assistance than were actually selected for emigration. Most of the Waldensian converts lacked the professional skills needed to help build Zion.[29] In addition, members in each of the mission’s three branches received assistance from the Perpetual Emigrating Fund, so that no single branch would be favored over another and, perhaps most important, to ensure that the membership of no single branch would be immediately depleted by emigration.

Besides disposing of their properties, these families had to make other preparations. Although it has been suggested that the Waldensians considered themselves more aligned with France than with Italy, they had effectively no ties to France.[30] The Waldensians felt a great allegiance to the Kingdom of Sardinia, particularly Carlo Alberto, who erected a monument in Torre Pellice to thank the Waldensians for their allegiance, and four years later he granted them civil and political liberties. As subjects of Sardinia (and after 1861, of unified Italy), the Waldensian converts understood that they had to obtain permission and a passport to leave their homeland, and that their sons were subject to military service and could not leave the kingdom without a deferment, which could be purchased in cases of hardship.

In October, Jean Bertoch paid two hundred lire to secure a military deferment for his eighteen-year-old son, Daniel. Without this, he would have been required to enlist in the army and would not have been permitted to leave Italy for at least two years.[31] Two other families had at least one son of military age: Jean Daniel Malan Jr., who went to Switzerland in December 1853 and was one of the first Waldensian converts to leave the valleys; and Daniel Gaudin, who was in the military just prior to his departure in November 1855.[32]

These families had to apply for passports to allow free passage out of the kingdom before their children fulfilled their military obligations. In October 1853, Jean Bertoch committed to pay for the passport of his son, Daniel, to France; Jean Daniel Malan committed to pay for a passport for Barthélemy Pons Jr. and for his son, Etienne Malan, both of whom were traveling to London. During the same month, David Roman obligated himself to pay for the passport of Jacques J. Bonnet to London.[33]

Shortly after these converts sold their properties and satisfied other legal obligations, they began preparing to leave Piedmont and take their long journey to Utah. Nevertheless, the families did not always have exclusive use of the proceeds to move their families. Although Jean Bertoch wanted to emigrate with his children, Jabez Woodard asked him to remain in Italy to preside over a third church branch, which was organized in San Germano on 7 January 1854.[34] Jean could have paid for his children’s trip by using the money he received when he sold his land, but he donated a portion of the proceeds to the church to sustain the Italian Mission. Likewise, when Jean Daniel Malan and his family were about to depart from Turin in February 1855, Samuel Francis requested that Malan contribute funds from the proceeds of the sale of their property to help sustain the church in Piedmont.[35]

The first group of Italian emigrants, consisting of twenty converts, included Barthélemy and Marianne Pons and their three children (representing the Angrogna Branch); Philippe and Marie Cardon and their six children (representing the Saint Barthélemy); and the children of Jean Bertoch: Jean, age twenty-six; Antoinette, twenty-three; Marguerite, twenty-one; Daniel, eighteen; and Jacques, fifteen (representing the San Germano Branch). Since Jabez Woodard planned to accompany the converts to England, meet his wife and three children there, and then continue to America,[36] Bertoch was confident that his children would be safely escorted to their new home in Utah. He sent them with the partial assistance of the Perpetual Emigrating Fund and promised them that he would join them in their new homeland the following year.

On 8 February 1854, the converts met in Torre Pellice to begin their long journey to the Salt Lake Valley. Undoubtedly, the Waldensians were somewhat prepared for the Spartan conditions they would endure during the next ten months by the hardships they had faced in their own valleys. In Torre Pellice they boarded coaches that took them to Susa, a historic village at the foot of the Alps. There they hired diligences (coaches), which were placed on skids and drawn by mules, to carry them up the steep Mount Cenis Pass and across the Alps to France. After the converts had successfully crossed the Alps, the diligences were placed on wooden wheels and the group continued to Lyon, where they caught a train to Paris, and from there to Calais. In Calais they boarded a steamer that transported them to the British coast, where they took trains to London and then to Liverpool.

The passengers normally boarded the ship within a day or two of their arrival in Liverpool, to avoid additional lodging expenses or potential problems, such as robbery. On 12 March the Italian converts boarded the John M. Wood, joining 397 Mormon converts from England, Denmark, and France.[37] The president of the British Conference selected a president and two counselors to preside over the Mormon converts on the ship, who then divided the converts into branches (usually along national lines), and each of these branches had a presiding elder. The center of the ship was reserved for married couples and families; single men were placed in the bow, and the single women in the stern.

After a journey of forty-eight days, the John M. Wood arrived in New Orleans on 2 May 1854. It was met by a church agent who had booked passage for the converts on the steamboat Josiah Lawrence, which transported them up the Mississippi to St. Louis. On 14 May, shortly before arriving in St. Louis, most of the Church members were detained on Arsenal Island, which in 1849 had become an inspection site and a quarantined area where immigrants were examined for cholera. On the morning the Josiah Lawrence arrived in quarantine, the Waldensian converts suffered their first death. Marguerite Bertoch, who had celebrated her twenty-first birthday shortly before leaving Italy, died of cholera in the arms of Philippe Cardon’s daughters. Eleven other Mormon converts died within a few hours and were buried with Marguerite on the island. Daniel Bertoch later called her death “one of [the] first hard trial[s] that I had to pass through.”[38] Eventually, a total of ten Italian converts died before reaching Utah.

After their release from quarantine, the Mormons boarded steamships that conveyed them up the Missouri River to Westport, Missouri, where they were met by another church agent who purchased wagons in either Cincinnati or St. Louis, as well as oxen, cows, tents, and food. Passengers normally supplied their own bedding and cooking utensils. They camped at a staging area at Prairie Camp, where they prepared for the difficult overland journey across the Great Plains. When a sufficient number of converts arrived at these camps, and provisions were ready, the converts were placed in companies of several hundred wagons.

Each company had ten captains who were responsible for approximately ten wagons each. Each wagon had ten converts, two milk cows, and one tent. The converts remained at the staging area for several months before starting their trek to Utah. During this time, Daniel Bertoch took lessons “in breaking whiled fatt steers never befor having had any expirians with any kattle.”[39] Tragedy struck again when Barthélemy Pons, the father of three small children, died of cholera. During the third week in July, the Waldensian converts were assigned to the Robert L. Campbell and William A. Empey companies.[40]

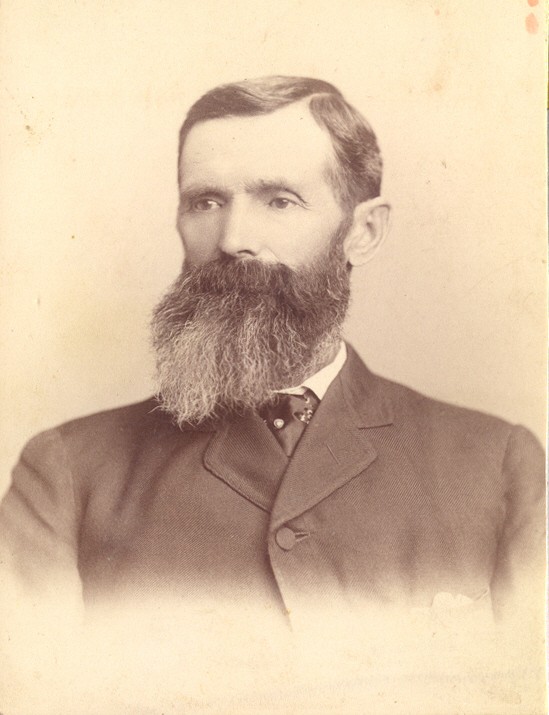

Antoinette Bertoch. Courtesy of Michael W. Homer and the Utah State Historical Society.

Antoinette Bertoch. Courtesy of Michael W. Homer and the Utah State Historical Society.

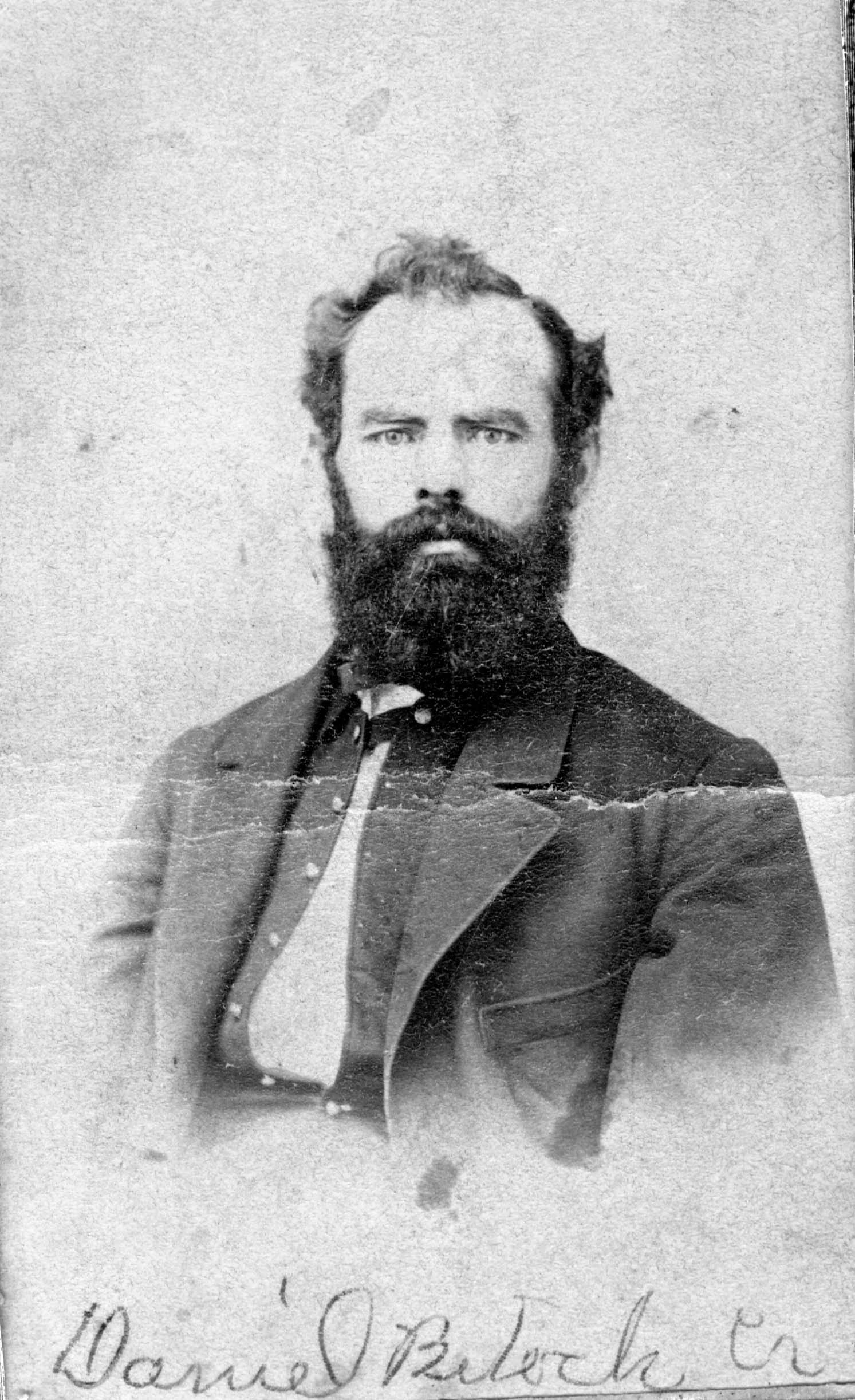

Daniel Bertoch and his sister Antoinette emigrated to Utah with her brother, James, in 1854. Courtesy of Michael W. Homer and the Utah State Historical Society.

Daniel Bertoch and his sister Antoinette emigrated to Utah with her brother, James, in 1854. Courtesy of Michael W. Homer and the Utah State Historical Society.

The companies traveled about thirteen miles per day during their westward trek. Although they banded their 150 wagons together when they saw Native Americans while crossing the Great Plains, they encountered other dangers as well. Daniel remembered that “our cattle never unyoked until we were out of buffalo country. We would camp early enough to feed the cattle before dark. . . . One night we had a stampede. The whole plain trembled and shook under the weight of 125 yoke of cattle running madly over the plains. In the morning we found them two or three miles from the camp. They were all together and we did not lose one.”

Although they successfully recovered cattle, they lost additional converts. Around the third week of August, while camping near Fort Kearny, Nebraska Territory, the converts were again stunned when Jean Bertoch died of pneumonia.[41] There were other close calls for the surviving Bertoch siblings. In mid-September, near Fort Laramie, Jacques fell from a wagon and the wheels ran over his legs. Although the boy recovered, he and his sister entered the Salt Lake Valley on 26 October, two days after their company’s forty-three wagons arrived, because they had wandered away from the company and become lost in the mountains.[42] Daniel’s company entered the valley on 28 October. It had taken the first group of Italian immigrants nine and one-half months after leaving Torre Pellice to reach Salt Lake City.

1855 Emigrations

Back in Italy, interest in emigration remained high. Shortly after the departure of the first group of emigrants, George Keaton wrote that “the Saints are increasing in faith and knowledge, and they rejoice in the glorious hope of one day assembling with the body of the Church in Zion, but they are determined to wait patiently until the day of deliverance comes.”[43] The year 1855 marked a turning point for the church in Italy. The continuing economic crisis, compounded by severe weather conditions and the buildup to the Crimean War, created abysmal living conditions in the Waldensian valleys and greatly obstructed the work of the missionaries. It is little wonder, then, that two of the three major migrations of the Saints to Utah occurred during this year, in March and November, comprising almost 60 percent (forty-five out of seventy-seven) of the total number of emigrants during the life of the mission.

Government officials were also interested in what was happening: On 4 July 1854, the mayor of Prarostino reported to the administrator [It., intendente] of the Pinerolo province “that Mormon agents through ‘flattery and promises’ had convinced several families, some Waldensians others not, to emigrate to that faraway region.” On 28 August, after receiving this report, the administrator advised the minister of the interior about the mayor’s report. During this period the provincial office [intendenza] in Pinerolo began keeping records of the number of people emigrating from the valleys.` [44]

Then, on 29 August, Joseph Malan of the House of Deputies (the godfather of Joseph Gay, whom Lorenzo Snow had blessed five years earlier), wrote a letter to the Waldensian moderator Jean Pierre Revel, in which he inquired whether Mormon missionaries were attempting to “seduce the people” and whether “it should not be difficult to repeat the same compliment that was given two years previous, to drive them out immediately.”[45] Malan was undoubtedly referring to the expulsion of Woodard and Combe from Turin two years previously. This suggests that the decision to expel Woodard may have occurred at a high government level and that the Waldensians remained concerned about the emigration of Mormon converts to Utah. The following month, Malan wondered whether the government should “apply the principle of freedom of conscience” or take a position that does not “completely approve the decision to expel them, a role that I would personally prefer, rather than . . . adopt coercive measures.”[46]

After Samuel Francis arrived in Italy, he was responsible for recommending which of the converts were the most deserving of church support for their emigration based on criteria provided by Daniel Tyler. In February 1855, Francis received a letter from Tyler granting permission for the Malan family and Elder Bertoch to emigrate, and the news was received with elation. “It was worth I don’t know how much,” Francis recorded, “to see the joy and mirth of the Malan family on hearing the news of their deliverance.”[47] Francis then appointed his missionary colleague, Ruban, as president of both the Angrogna and San Germano branches, replacing Malan and Bertoch.

The second group of Waldensian converts consisted of fifteen people: Jean Daniel Malan and his family (including his married daughter Marie Catherine); seventeen-year-old Jean Jacques Bonnet; David Roman, widower and brother-in-law of J. D. Malan Sr.; and his four-year-old son, Daniel—all from the Angrogna Branch—and Jean Bertoch of the San Germano Branch.[48]

On 7 March, Francis accompanied the group to Turin where they stayed at the Albergo Commercio, and while there David Roman confessed that he had acted improperly toward Malan’s daughters. The Malans forgave him, and he was rebaptized. In addition Malan gave a sizeable donation to the church (ninety francs out of the eight hundred he had obtained from the sale of the family property), some of which was used to contribute toward the cost of Roman’s passage.[49]

This group followed the same route used by the first group one year earlier, though they did travel to Susa in a little more comfort because of the completion of the rail line from Pinerolo to Turin and from Turin to Susa in 1854.[50] In Lyon, the converts were met by Antoine Gaydou, son-in-law of Jean Daniel Malan and husband of Marie Catherine Malan, and his friend Dominic Brodrero. Although neither Gaydou nor Brodrero were Mormons, they planned an encounter with the group and threatened to prevent Marie Catherine from leaving Europe unless her father agreed to pay their passage to America. Although it is unclear precisely what happened, they did join the group and continued with them to Liverpool, and on 20 March both Gaydou and Brodrero were baptized.

They departed Liverpool aboard the Juventa on 31 March 1855 and arrived in Philadelphia thirty-five days later on 5 May 1855. In contrast to the first immigrants, this group arrived without suffering any losses. The Latter-day Saint hierarchy had selected Philadelphia as the point of entry to save both the time and the lives that were often lost due to cholera when converts arrived in New Orleans. In Philadelphia, John Taylor helped arrange the divorce of Marie Catherine and Gaydou, who thereafter separated himself from the Mormon company and did not continue to Utah.

From Philadelphia, the Italians traveled by rail as far as Pittsburgh, where they boarded steamboats that transported them to St. Louis. There they changed boats, went up the Missouri River to Atchison, Kansas, and outfitted in Mormon Grove, where they prepared for the westward trek. Unfortunately, many Mormon immigrants, including Jean Bertoch, died of cholera in Mormon Grove and were buried in unmarked graves near the campground. During the spring and summer of 1855 “nearly 2,000 Latter-day Saints with 337 wagons” left Mormon Grove for the Great Basin. After remaining in Mormon Grove for nearly two months, the Italian converts departed on 25 July with the Charles A. Harper company, which arrived in Salt Lake City on 26 September 1855. [51]

Back in Italy, Antoine Blanc, the mayor of Torre Pellice, noted in late 1855 that Mormon missionaries (mentioning Francis) continued to seek converts through encouraging emigration. By this time the Mormons had become a much greater concern since family members were leaving the valleys.[52] Then, on 28 November 1855, a third group of thirty Waldensian converts departed the mission. Most of the members of this party were entirely subsidized by the Perpetual Emigrating Fund and included Michael Beus, his wife and ten children; Michel Rochon, his wife and four children; Pierre Lazald[53] and his two teenage children; Pierre Lazald’s siblings Pierre and Henriette Chatelain, all from the San Germano Branch; Jean Pierre Stalle, his wife and five children, and Madeleine Malan, all from the Angrogna Branch; and Marie Ann Gardiol, and Suzanne and Catherine Gaudin, from the San Bartolomeo Branch.

This group left Liverpool aboard the ship John J. Boyd on 12 December and arrived in New York City on 15 February 1856. In New York two children (Elizabeth Rochon and Catherine Lazald) disappeared in circumstances that are not clear. The group traveled from New York to St. Louis, where Pierre Chatelain married Madeleine Malan, the first of many marriages between Waldensian converts. From St. Louis they traveled to Iowa City, where they joined up with handcart companies. Sixty-pound carts were constructed in Iowa City and loaded with up to one hundred pounds of provisions, and converts were expected to walk the entire distance to the Salt Lake Valley. On 17 August, Jean Pierre Stalle died on the Platte River while traveling westward from Iowa City. Most of the Italian converts arrived in Salt Lake City either in September with the Edmund Ellsworth company or in November with the Edward Martin Company.[54]

The following year Pastor Jean Jacques Vinçon of Pramollo noted in his annual report to the Table that “the Mormon family that I reported to you about last year have left the parish to go to California.” He had earlier reported to the Table that the only “separatists” in his parish consisted of “one Mormon family.”[55] But after the departure of the third group of converts, only a few families of active members remained in the valleys. They included the Justet family, Jacob Rivoir, and Francis Combe. Although they remained committed to Mormonism, they were also extremely anxious to escape the poor economic conditions of their valleys. But only one member, Bartholomew Bonnet, who emigrated in 1856, succeeded in leaving during the remainder of the decade. The following year Pastor Jean Jacques Bonjour of the San Germano Parish reported that, while some Parish members had departed with the Mormons, no additional Parish members had converted to Mormonism.[56]

After 1855, the Perpetual Emigrating Fund became increasingly strained and the church became “more selective with respect to the type of migrants it assisted.”[57] Thereafter unskilled converts found it increasingly difficult to leave for America, and some converts who may have joined largely in hopes of receiving immigration assistance began leaving the church and returning to their Waldensian roots. In addition, the number of convert baptisms declined sharply following the third and final migration in November 1855. The numbers speak for themselves: there were fifty-eight baptisms in 1853, twenty-seven in 1854, twenty-six in 1855, eight in 1856, and none in 1857 or 1858.

But the members who did remain in Piedmont received an occasional communication from those who had left the valleys. In June 1855, Samuel Francis reported that the Cardon family, who had left Italy in February 1854, sent a letter giving details of their new lives in Utah, and Francis noted in his journal that this “did much good to the Saints, also to the world.” In July 1855 a letter arrived from Stephen Malan, who had departed with the second emigration in March, providing an update on the Italian emigrants and bearing sad news of the death of Elder Bertoch, formerly president of the San Germano Branch, while en route to Utah.[58] Francis also reported to Franklin D. Richards that Philippe Cardon sent a letter to his daughter, who was not a church member and remained in the valleys, and that this communication “seems to restrain the prejudices of the people, for a little time.”[59]

During this same period, the Waldensian Church began to formulate its own program of emigration. Emigration was an extremely sensitive subject for the Waldensian clergy. In 1856 the Tavola published a list of eleven Waldensian families who wished to emigrate. This list included the names of the David Justet family of Inverso Pinasca. Justet had been baptized into the church on 17 April 1851, but his family did not take part in any of the three groups that emigrated in 1854–55. Thereafter the Waldensians organized their own emigration program and established Waldensian communities in North and South America.[60] In November 1856, three families left the valleys and emigrated to Montevideo, Uruguay. After their arrival in February 1857, they wrote to others in the valleys and encouraged them to join.[61] In June 1857, sixty-seven additional Waldensians departed for South America. All but one family went to Uruguay. In December, a third contingent of twenty-seven families (136 people) left the valleys for Uruguay.[62]

Later Emigration

During the 1860s an additional twelve Waldensian converts emigrated to Utah. In 1860 Jean Michele Rostan and his wife, as well as Marie Louis Chatelain, arrived in Utah with the Oscar O. Stoddard handcart company; in 1861 Anna Rivoir and Marie Justet accompanied Jabez Woodard back to Utah after he had completed his second mission for the church in Switzerland; and in 1863 Marie Chatelain (the sister of Pierre and Henriette who emigrated in 1855), their cousins Catherine, Louise, and Lydia Chatelain, as well as Jean Avondet, his wife Marie Defoury, and their son Jean also left the valleys.

During the last five years of the decade, nine more longtime members also emigrated: in 1866, Jacob Rivoir, of San Germano left the valleys; and two years later Daniel Justet, his wife, and six children finally emigrated. Both Jacob Rivoir and Daniel Justet had also served as missionaries for the church before their departures. The last Mormon convert from the first Italian mission emigrated in 1871. In September Catherine Jouve (who is listed as Katherine Youve in Mormon immigration indexes) left Liverpool. The journey from the Waldensian valleys to the Salt Lake Valley took about nine to ten months. Less than 6 percent of the Waldensian converts died while traveling to Utah, but these included the fathers of five families, which made the lives of their children much more difficult. In addition, at least one convert abandoned the church in Philadelphia (Antoine Gaydou), and two disappeared in New York (Elizabeth Rochon and Catherine Lazald).

Settling in Utah

Some of the immigrants were stunned by what they saw when they arrived in the valleys. For example, many years after his arrival Stephen Malan recalled that he “had been raised in those fair valleys of Piedmont where nature exhibited so many gifts where one would inhale the sweet fragrance of the thousands of variegated flowers which the evergreen meadows produced so exhilarating to the senses.” He could therefore “not sense the descriptions given while in my native land, of the flowery border of the River Jordan, nor of the virgin prairies of the valleys of Deseret, nor of the dense forest, and shrubs of its mountain dales and limpid water brooks, and salubrity of its climate.” Nevertheless, he “conjectured something of a similarity to my country’s nature’s gifts.”

When Malan finally approached the Salt Lake valley he “arrived with perspiration and almost breathless; upon a slight elevation at the mouth of the canyon, my eyes surveyed the whole landscape from the spot upon which I stood; nothing but desert was visible; from the East to West mountains, I could not perceive anything indicative of anticipation. Seeing some teamsters on their way up the canyon I actually inquired of them where was that great valley of Salt Lake and where was the city located.” He wrote that they responded “with a burst of laughter. They asked me if I was deprived on my eyesight. . . . The contemplation not only dimmed my eyes [but] actual tears rolled down my cheeks. Was it joy to be gazing upon Zion’s hills that produced the agitation? No! It was disappointment that was conceived through my ignorance of the aspect which I was to witness and the abortiveness of my sanguine anticipations.”

But like many converts who had gone through this test and persevered he was pleased to record: “The test was a severe one but it was momentary. As I walked along the road the fragrance of the sage was beginning to cause a cogitation upon my mind that this indigene plant growing so profusely could be changed into a fruitful orchard, and gardens by man’s industry, and that the whole valley could eventually be converted into that condition which I had anticipated. It is now so to a great extent.”[63]

When converts arrived in Salt Lake, they normally congregated at the Tithing House where they were met by friends and family and taken to their new settlements, but widows and orphans were placed with patrons. For example, the Pons and Cardon families, who traveled with the first group, were sent to Mound Fort in Weber County, which was one of four forts built during the 1850s in the Ogden area.[64] and a thriving farming community which needed unskilled laborers, while the Bertoch children were placed in the care of Joseph Toronto to work on his ranch in Salt Lake County.

In December 1854, Wilford Woodruff visited Bingham’s Fort and reported in his journal: “Farming land good & abundant. Their present population is 100 families. Much wheat raised.” Concerning settlements in Ogden and Weber County, he also noted that in Ogden Hole “their soil vary rich & water abundant.”[65] The second group of Italian converts (J. D. Malan, Bonnet, Brodrero, Roman) also settled in Mound Fort. The first winter for these new immigrants was very difficult because they had to work hard to merely survive.[66] Food was hard to come by for many of the early years. Pauline Combe Malan recalled that, upon arriving in Ogden, their family found

Zion, a desert, but with patient industry, perseverance, and God’s blessing, we have noticed it gradually transform from our forbidding desert to a fruitful and most desirable land to dwell on. As we came in the year of the grass-hopper war, bread stuff was very scarce and a hard winter followed. We suffered much hunger and cold. In the spring of ’56, we subsisted mostly on wheat and bran. Fish were quite prolific in the Ogden River, so father made traps with willow twigs to catch fish. In the fall, we cleaned our bread stuff. We thrashed and separated the wheat from the shaft by hand.[67]

Because of these harsh conditions, Madeleine Malan was sent to work at the Toronto home during several months in 1856. Most members in the third group (including the Stalle and Beus families as well as Peter Chatelain and his new wife) also settled in the Ogden area.

When Jacques (who eventually was known as both Jack and James) and Antoinette Bertoch arrived in Salt Lake, they were introduced to Joseph Toronto, who took them to his residence on First Avenue to wait for Daniel. Daniel spent his first night in the city in a shelter “made back of a dirt wall, just north of John Sharp’s dwelling.” The next day Daniel met Toronto, who “took me [Daniel] to his house where I met my brother and sister.”[68] Brigham Young asked Toronto to supervise the Bertoch children because they were not accompanied by their father. The siblings were relatively young, did not speak English, and shared an Italian connection with Toronto. Even though Toronto did not speak the local dialect or French, which were widely used in the Waldensian valleys, he could speak Italian, which was another language the children could speak.

Young also assigned Toronto the task of caring for his cattle herd on the Great Salt Lake’s Antelope Island, and the three Bertoch children went “to Antelope Island to work for President Young, under the direction of Mr. Toronto.” [69] Those who had borrowed from the Perpetual Emigrating Fund often repaid the church by working on public works projects, and the young Bertochs were expected to labor in “redemption servitude” to repay their loan while they waited for their father.[70] The three did not reside at Fielding Garr’s ranch but lived in a rustic shelter built by Toronto.

The boys had the duty of walking around the island every day to check the location of cattle while Antoinette remained at the cabin to perform domestic chores. Toronto brought supplies every two weeks. The three survived on flour, bran, cornmeal, squash, and “bunch grass to chew on.” Daniel reminisced, “I had to go to the canyon every day for wood, which resulted in wet feet. For my shoes were so bad that I was obliged to tie them on with strings.” He also remembered, in a letter to Jacques, “our early days in Utah especially on the Church Island when we eat that big Ox. . . . Toronto said the Grando Bovo will Die we better kill him and eat him oh how toff he was I would had good teeth yet if it hadn’t been for eating of that Ox and—many other things we did eat makes me sick to think about it now.”[71]

Daniel wrote that in the spring of 1855:

Toronto and myself started for Salt Lake with a piece of bran bread in our pockets. We were trying to find the head of the Jordan River. We came across a large flat boat filled with water, we stayed to empty it, but before our task was done it began to get dark, so we started for the nearest light. We stayed with Mr. Keits at K’s Creek. At breakfast I was seated next to a young lady about eighteen years old, dressed in a clean calico dress. Imagine my humiliation, for I was dressed in a greasy canvas, that Toronto brought from New Orleans. Next day we went back to complete our task and a terrible storm came making it impossible.[72]

This storm put Daniel and his companions “in danger of our lives. . . . Toronto called to us to come into the boat, and we began to pray in English. When we finished he called on a Danish boy, and he prayed in Danish; then he asked me. I prayed in French for the first time without my prayer book. It wasn’t very long before the storm quieted down and we got away safely.” These experiences, which Daniel remembered throughout his life, persuaded him to leave Antelope Island. “The next day we started in quest of the Jordan River, we found it in the late afternoon. We got in our boat and traveled up the river, we camped that night at Bakers. The next day we arrived in Salt Lake and went to Toronto’s. I stayed with him long enough to get a pair of shoes then I ran away.”[73]

Daniel found Salt Lake much busier than Antelope Island. When he realized the church was constructing a temple there, he decided that he would rather help dig its foundations than continue to live and work on the island. He labored at the temple block for about six weeks before John Sharp hired him to help dig a canal from Big Cottonwood Canyon to City Creek to transport granite for the construction of the temple. Sharp furnished Daniel and his fellow workers a weekly ration of “½ pounds of shorts [bran and other by-products of milling], 1½ pounds of flour and meat the size of a mans two fists.” In the fall Daniel “went to Sharp for [his] money, [Sharp] told [Daniel] there was no money, only what we ate.”[74]

Daniel was left penniless “and without a place to stay,” but he was even more distraught when he was told that same day, by a company of Mormon immigrants, that his father was dead and had been buried in Mormon Grove, Kansas. Daniel was stunned by his father’s death, which occurred about the same time he ran away from Antelope Island. He decided to swallow his pride and return to the island to rejoin Jacques and Antoinette: “My brother and sister were living on the island. I felt pretty blue and alone in the world. Having run away from Toronto I hated to go back, but I did and he took me back on the island in the fall of 1855.” [75]

During the summer of 1855, grasshoppers devastated the valley and the island even more severely than they had the previous year. The winter provided no relief. Daniel later wrote that “the winter of ’55 and ’56 was a hard one. The spring of 1856 was one of the hardest that the people had to pass through. Many a family had to sit down to the table and ask the blessing on the food and there was nothing but a dish of greens to be seen.”[76]

Antoinette and Jacques lived in virtual isolation from Mormon society on Antelope Island. Although Daniel worked for the church in Salt Lake City during the spring and summer of 1855, he also spent most of his time on the island. After spending two years on Antelope Island, Antoinette Bertoch married Louis Chapuis, a twenty-nine-year-old Swiss convert who lived in Nephi, whom the Bertoch children met two years earlier during their voyage from Liverpool. Her brothers cultivated relationships with surrogate fathers, closely connected to the church hierarchy, who promised them food and shelter in exchange for work.

In the fall of 1856, Daniel “started to work for George D. and Jedediah Grant” at Mound Fort, in Ogden. His patrons were at the center of the Mormon Reformation, and Daniel was rebaptized in the Ogden River. Jacques moved from Antelope Island to the Point of West Mountains (near Garfield) when his patron Joseph Toronto, seeing that grazing conditions were better near the shore of the lake, decided to relocate his personal ranch.[77]

In 1854, the territorial legislature had begun issuing grazing rights, not only on the islands of the Great Salt Lake but also on the lakeshore from Tooele to the mouth of the Jordan River. Good grazing lands were becoming increasingly scarce because of grasshoppers and severe weather. Jacques became the foreman of the new ranch and began using “Jack Toronto” as his nickname. He lived in a one-room rock building that he and Toronto constructed, and he used an oblong cavern known as Toronto’s Cave as an additional shelter and barn.[78]

Other converts from the first group also settled in Salt Lake because of the severe conditions. In September 1856, Lydia Pons, the daughter of Barthélemy Pons, worked in Salt Lake City for the Wells Chase family. John D. Malan Jr. also arrived in the Salt Lake Valley in the fall of 1854 and, like the Bertoch children, had no other family members in Utah. As such, Malan was sent to live with Lorenzo Snow, who had settled Box Elder County in October 1853. In the third group, Jean Lazald (“Lazald” being the anglicized form of Lageard), a nine-year-old orphan, settled in Salt Lake City with the Almon family, and Marie Ann Gardiol, a twenty-year-old single girl, became the plural wife of Jean Dalton in Salt Lake City four months after her arrival.[79]

The Utah War

In La Voix de Joseph, Snow had reassured the Waldensians that there was no “external, or internal danger” in Utah. But within a few years after the arrival of the first group of Italians in Utah, the United States Army began marching toward the territory to replace Brigham Young as governor.[80] Stephen A. Douglas noted at that time that “nine-tenths of the inhabitants are aliens by birth who have refused to become naturalized, or to take the oath of allegiance.”[81] During the summer and fall of 1857, various diplomatic efforts were undertaken to prevent a confrontation between the United States government and the church. On 15 September, Young declared martial law and ordered the Utah militia to establish defensive fortifications in Echo Canyon to prevent the US Army from entering the Salt Lake Valley. On 29 September, the militia, under the command of Daniel H. Wells, began construction of fortifications by digging trenches across the canyon and placing rocks on the precipices overlooking the canyon that could be toppled on the soldiers if they attempted to pass through the canyon.

During this period, Brigham Young wrote to mission leaders instructing them to advise missionaries to return to Utah to help with war preparations.[82] Missionary work ground to a halt as missionaries throughout the United States and Europe began preparing to return to Utah. On 16 November, after the Utah Army went into Winter Quarters at Camp Scott, diplomatic discussions were recommenced in an effort to avert bloodshed. In March, Young ordered settlers in Salt Lake City and in the northern settlements to abandon their homes and proceed to the river bottoms in Provo Canyon. In May, they complied with these instructions and only a few remained behind. Most of the elders from the missions in the United States and Europe arrived in Salt Lake City by June 1857. Shortly thereafter, the federal government and the church negotiated a peaceful resolution of the dispute, and on 26 June the US Army passed through Salt Lake City. Within a week, the First Presidency authorized settlers to return to Salt Lake City and northern settlements.

Brigham Young recognized the Waldensians during this very difficult period. On 18 October 1857, Young spoke in the Tabernacle about the heroic activity of the Waldensians during their own history.[83] Young saw striking similarities between Waldensian history and the situation in Utah Territory, and he reminded church members that the Waldensians had showed courage and perseverance in defending their valleys and he encouraged his followers to do likewise.[84] During the spring of 1858, when Young ordered members to the Provo River bottoms in Utah County because of the oncoming federal troops, the Waldensian community in Ogden joined the general exodus to the river bottoms in Provo. They remained there for two months while the army passed through Salt Lake City.

Like many Mormons, Daniel and Jacques Bertoch were seized by the events that briefly disrupted the territory during the winter of 1857–58. During that fall, the Utah Militia was ordered to protect Echo Canyon from invasion. Jacques Bertoch accompanied Joseph Toronto to the canyon where, like his ancestors, he helped prepare his church’s resistance to government troops. With more than two thousand other volunteers, he dug trenches across Echo Canyon and on the hills overlooking the canyon he loosened rocks that could be hurled down at the soldiers.

Assimilation into Mormon society

The Mormon converts who left Piedmont during the 1860s followed the pattern set in the previous decade and settled in Weber County. There were some exceptions. Marie Justet, who immigrated to Utah in 1861, married Christian Mooseman and moved to Washington County. When her father, Daniel Justet, and his family emigrated to Utah in 1869, they also settled in Washington County. After the Utah War, some Waldensian families, who had initially settled in Weber County, migrated to other areas in the territory. Jean James Bonnet and Charles David Roman remained in Provo following the war while Philippe Cardon moved his family to Logan in 1859.[85]

Philippe’s son Thomas B. Cardon enlisted in the US Army at Camp Floyd on 1 September 1858 and spent the Civil War in the eastern United States. Daniel Bertoch returned to Ogden with George D. Grant, but shortly thereafter he moved with him to a ranch located near Littleton, in Morgan County. Eighteen-year-old Jacques Bertoch returned to the Point of West Mountains and resumed his duties as ranch foreman for Joseph Toronto.

The Malan family stayed in Weber County. Richard Sadler and Richard Roberts have noted that “the Malan family presents an example of how some pioneer families moved to different areas of the country as communities developed. The Malan family first homesteaded in the River-bottom area at 12th Street and later moved to develop bench land at 24th Street in Monroe Avenue, where they found rattle snakes around their cabins. . . . By 1894, they had moved to the Knob Hill area of East Capital Street and at the same time acquired the Malan’s Heights land which ran from the base of the mountains to Malan’s Peak. In less than half a century, they had moved across the developing areas of Ogden City.”[86]

Assimilating in Zion and in America

The experiences of these Italian converts demonstrate that it was sometimes easier to assimilate into Mormon society than it was to integrate into the American economic system. Following their settlement in Utah, the Italian converts had to create a new life. Their “break with the Old World” was “a compound fracture: a break with the old church and with the old country.”[87] It took time for these fractures to heal. In order to heal their break with the old church, they had to overcome language, cultural, and religious differences. When the Waldensians left their villages, separated in Salt Lake, and gradually began losing their cultural distinctiveness, their eventual assimilation into Mormon society was assured. They no longer had daily association with persons who shared their language and customs. They began to associate with other church members and eventually married converts from other nationalities and cultures. They raised English-speaking children, became parishioners in multicultural church meetings, and were called to church positions.

Diane Stokoe has demonstrated that a high percentage of the Waldensian converts accepted polygamy. Of the sixty-seven Waldensians who immigrated to Utah, 100 percent married, one-third entered into polygamy, two-thirds entered into monogamy, and five were divorced. Each Waldensian emigrant had an average of seven children. In addition, a surprising number of Waldensians married other Waldensians, perhaps because of settlement patterns. Fifteen of the thirty-eight monogamous marriages contracted by the Waldensians were within their group, and eleven of the twenty-four polygamous marriages were also endogamous (that is, between Waldensian converts).[88]

Italian converts contributed their experience and knowledge to the development of the silk industry (or sericulture), which became an important component of Utah's economy in the latter half of the nineteenth centruy. This photo shows a group of women processing mulberry plants used for cultivating silkworms. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Italian converts contributed their experience and knowledge to the development of the silk industry (or sericulture), which became an important component of Utah's economy in the latter half of the nineteenth centruy. This photo shows a group of women processing mulberry plants used for cultivating silkworms. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Some women obtained protection and patronage by marrying after being widowed or arriving in Utah without family. For example, Marie Ann Gardiol, one of eleven children of James Gardiol and Catherine Gardiol, was the only member of her family who emigrated. She settled with John Dalton and became his plural wife; Marie Stalle, who was widowed during the trip to Utah, married Philippe Cardon six years after her arrival; Susanne Stalle settled with the Cardons and eventually became the plural wife of Louis Philippe Cardon in September, 1856; and Marie Louise Chatelain became the plural wife of J. D. Malan, Sr., three and a half months after her arrival in the valleys. The Waldensians who married soon after their arrival included Susanne Rochon, who was widowed in 1856; and Antoinette Bertoch, who was orphaned in 1855, left Antelope Island in February 1856, and married Louis Chapuis.

But the assimilation of the Waldensian converts into Mormon society did not result in their automatic integration into American society, the object of virtually every convert from Europe. Some Waldensian converts pursued new trades after they arrived in Utah. In 1856, Michel Beus manufactured charcoal; Jean Cardon established a mill in Weber County; Pierre Chatelain was a miller; Jean Justet, Sr., was a rock mason; and Jean James Bonnet was a translator in court cases and business transactions. A few Waldensians were selected to assist in the creation of an economic enterprise. In April 1857, J. D. Malan, Sr., who was a mechanic and carpenter and established a saw mill in Ogden Canyon, was called to gather information concerning the silkworm industry. The following decade, Paul Cardon was sent to France for mulberry seeds that were planted in Cache County. Susanne Gaudin Cardon was called on a mission to teach women how to spin silk. Michel and Marianne Combe Beus were among the first to raise and spin silk in Utah County. David Roman grew mulberry trees and eventually had over six thousand trees under cultivation. Lydia Pons and Marianne Pons also raised silk, and Marianne Pons was on a committee to set aside land for the silk culture.

But the process of assimilation was more difficult for converts who, like most Waldensians, were farmers and ranchers and were not skilled in any trade. These immigrants “faced years of hard work in order to save enough money to buy improved land or a going business.”[89] In fact, many immigrants did not successfully assimilate economically until Utah began its own gradual integration into the national economy. This process was accelerated after the Homestead Act was passed in 1862 and a United States Land office was established in Utah in 1869 after the completion of the transcontinental railroad. This legislation empowered settlers who had no economic resources to obtain free land. New immigrants, as well as the children of landowners, could apply for patents—legal titles—for as much as 160 acres of surveyed land. Applications would be approved if homesteaders could demonstrate that they had improved the land, plowed, raised crops, put up fences, dug wells, constructed ditches, built homes, and lived there for at least five years.

James Bertoch, 1838-1924. Courtesy of Michael W. Homer.

James Bertoch, 1838-1924. Courtesy of Michael W. Homer.

The experiences of Daniel and Jacques Bertoch provide good examples of how Waldensian immigrants gradually assimilated into American society. The Bertoch brothers learned to speak English, worked for their patrons, attended church, and married young British converts who had recently arrived in the territory. In 1866 Daniel married seventeen-year-old Elva Hampton, who gave birth to four children before she died in 1874. Following her death, he married another British convert, eighteen-year-old Sarah Ann Richards, who bore him five more children. In 1866, Jack, who by this time preferred the name James, married nineteen-year-old Ann Cutcliffe.[90] She eventually gave birth to thirteen children.

After Daniel and James Bertoch each married and began raising children, they continued to work for their patrons in exchange for subsistence in kind. Although they wanted to own their own farms, they could not afford to purchase property because their patrons did not pay wages. As long as they continued to work for room and board, they did not have any realistic prospect of achieving economic independence or of enjoying “access to the soil, the pasture, the timber, the water power, and all the elements of wealth,” as promised in La Voix de Joseph.

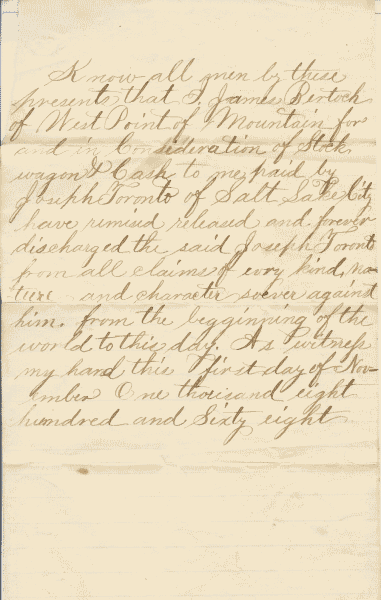

In 1868, Joseph Toronto and James Bertoch entered into an agreement under which Toronto transferred some of his assets to Bertoch to assist him in the transition from an indentured servant to an owner and operator of his own ranch. The agreement (in Bertoch’s handwriting) was entered into after Bertoch and his wife had already produced two children. It provided that in exchange for “Stock, wagon & Cash” Bertoch would release Toronto from “all claims of any kind, nature and character . . . from the beginning of the world to this day.”

Toronto had been Bertoch’s patron and surrogate father for fourteen years when the men entered into this agreement that provided a pathway for Bertoch to become a participant in Utah Territory’s agrarian economy. This development demonstrates that the men had developed a strong familial bond and that Toronto recognized Bertoch’s contribution to his family’s estate and knew that he needed some help to build a solid foundation for his growing family. But the Bertoch brothers’ patrons could not convey real property to them, even though some local church leaders had distributed land to some families, since these distributions were not recognized as legal conveyances until the United States Land Office confirmed them.

Agreement dated 1 November 1868 between Joseph Toronto and James Bertoch releasing Toronto from any further claims "from the beginning of the world to this day" in exchange for "Stock, wagon & Cash." Courtesy of the Joseph Toronto Family Organization and J. Willard Marriott Library Special Collections, University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

Agreement dated 1 November 1868 between Joseph Toronto and James Bertoch releasing Toronto from any further claims "from the beginning of the world to this day" in exchange for "Stock, wagon & Cash." Courtesy of the Joseph Toronto Family Organization and J. Willard Marriott Library Special Collections, University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

Because of this, both Daniel and James had to wait to apply for homesteads on land where they had labored for patrons all of their adult lives until after the Land Office was established in Utah Territory. Daniel filed an application for a homestead of eighty acres located in the vicinity of Littleton, Morgan County. Daniel had lived and worked in Morgan County for the Grant family since 1860. In his application he noted that he had made improvements to the land since 1862. James filed his application for a homestead of 79.8 acres on 20 June 1874. His homestead was located near the Toronto ranch in the Point of West Mountains, also called Pleasant Green. He had worked there since 1856, and he had lived there with his wife and children for eight years. James built a house and planted crops and fruit trees on the gentle slope of the mountain that rose above the highway that ran from Salt Lake City to Tooele.

This final step in the brothers’ assimilation into the Utah economy was also a catalyst for their becoming United States citizens since the Homestead Act required all applicants for land patents to be naturalized. The United States Land Office granted Daniel title to his homestead on 1 October 1879, and to James on 30 March 1881, after it approved the final proofs that confirmed they had complied with all of the requirements of the Homestead Act, including citizenship.[91] Many other Waldensian converts who settled in Utah followed this same pathway of assimilation.

The Second Wave of Waldensian Immigrants

Eventually some of these Waldensian converts returned to Italy and encouraged family members and former neighbors to immigrate to Utah. This stimulated a second wave [It., seconda ondata] of Waldensian immigration to Utah.[92] But most of the Waldensians who participated in this new wave did not convert to Mormonism and continued to associate with Protestant congregations.

The second wave began when Jacob Rivoir returned as a missionary to the valleys in 1879 and departed the following year with family members. Two years later, James Beus visited Italy after serving an LDS mission in Switzerland. He encountered (but did not convert) Joseph Combe in the valleys, and Combe later emigrated to Utah (followed several years later by his family) where he became a deacon member of the Presbyterian Church in Ogden. James Bertoch also served a portion of his mission in San Germano in 1892–93, and some of those he encountered also eventually settled in Utah.

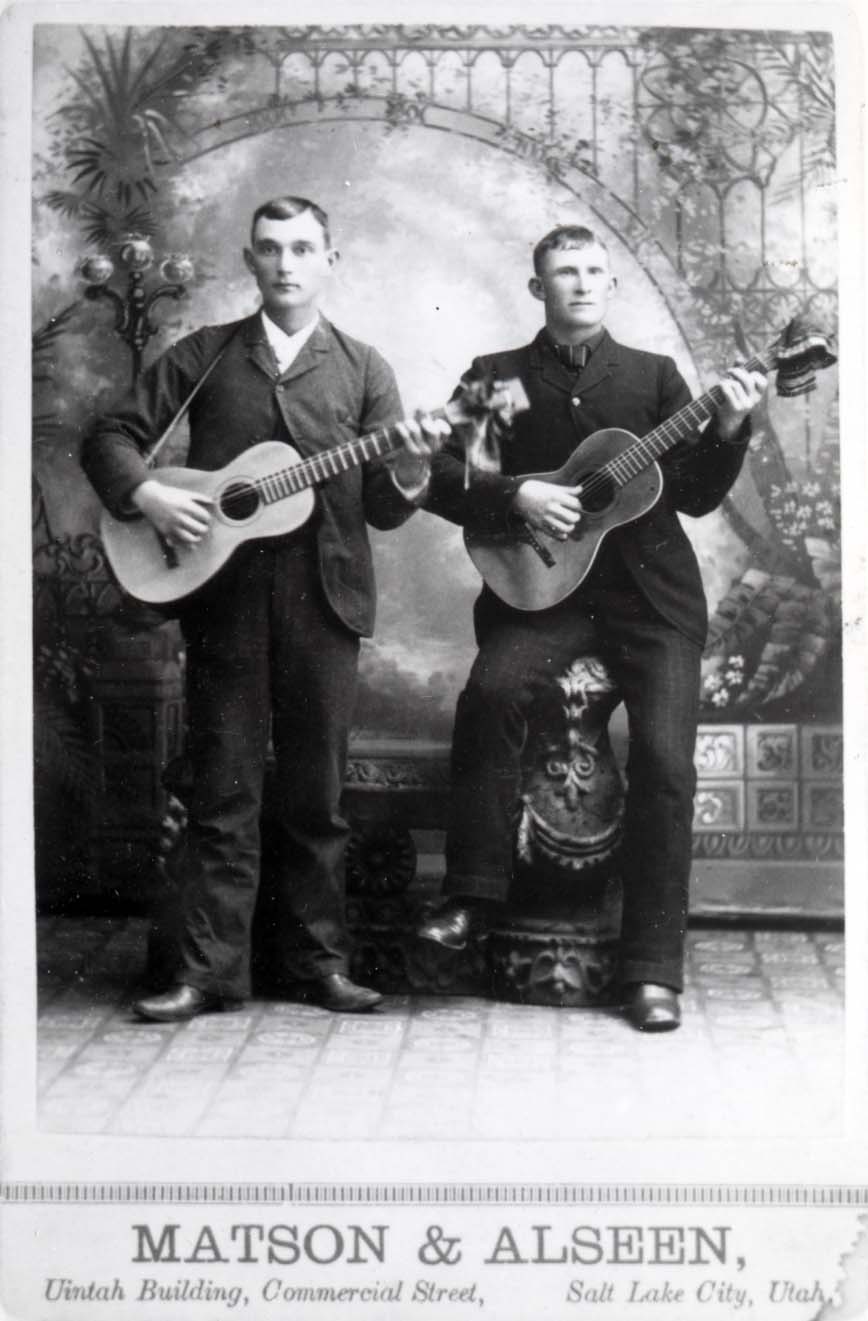

Waldensian musicians in nineteenth-century Italy pose with family members and friends for a photo. Italian LDS emigrants brought their culture and talents to contribute to Utah community life. Reprinted from Papini, Come Vivevano.

Waldensian musicians in nineteenth-century Italy pose with family members and friends for a photo. Italian LDS emigrants brought their culture and talents to contribute to Utah community life. Reprinted from Papini, Come Vivevano.

During this second wave, which continued for more than three decades (1879–1910), twenty-five families and at least eighty-eight immigrants came to Utah, which was greater than the number of Mormon converts who immigrated decades earlier. One reason the wave continued was that new immigrants kept in touch with cousins and friends in the valleys. La Sentinella Valdese, a newspaper edited by Pastor Carlo Alberto Tron in San Germano Chisone (who accompanied the Waldensians who settled Valdese, North Carolina, located at the foot of the Appalachian Mountains in the Piedmont region of the state), published letters written by Waldensians living in both Valdese and in Provo, Utah. These immigrants shared exciting news about developments in America and even donated funds to help support l’Asilio dei Vecchi [old folks home] in San Germano.[93] Over time, some emigrants moved to North Carolina transferred to Utah, and a few who originally settled in Utah relocated in North Carolina. In addition, some of the Waldensians who moved to Utah eventually converted to Mormonism or married into Mormon families.

In 1913, after the second wave had concluded, David Bosio, a newly consecrated Waldensian pastor from San Germano Chisone, met with many of these immigrant families when he visited Utah and preached at the Ogden Presbyterian Church. He recorded that the Waldensians who settled in Utah during the 1850s as Mormon converts “still have deeply religious feelings,” whereas those who came later “were not attracted by the Mormon religion,” and he calculated that the later wave included “fifteen families who either came directly from the Valleys or from the colony of North Carolina; but if we also include the families of our brothers, their sons and grandsons, the number becomes much larger.” Bosio concluded his report by inviting “the church of the Valleys to remember these faraway children, who still look to her with loving memories, in their prayers.”[94]

The two musicians above include a grandson of Jean Bertoch. Courtesy of Church History Library.

The two musicians above include a grandson of Jean Bertoch. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Many of these Waldensians, both Mormon and non-Mormon, welcomed Bosio into their homes and expressed great pride in their heritage. Following his visit, no additional Waldensians immigrated to Utah during the Mormon interregnum of missionizing.

Despite the influx of more than 170 Waldensians into Utah from 1854 to 1910, they were seldom identified as Italians. The Kingdom of Italy was not created until 1861 (after most of the Mormon converts arrived), and many preferred to identify with France because of their family names and their preference for the French language rather than Italian. Thus there were few traces of the Italian Mission until the church reestablished a new mission during the 1960s that focused its efforts among the Italian population that lived in the large urban areas of Turn, Genoa, Florence, and Rome. This second mission (discussed later in this volume) was much more successful and encouraged its convers to remain in Italy rather than emigrating to the “land of Ephraim.”

Notes

[1]“Appendix to Italian Mission,” in Richards, The Scriptural Allegory, 297–312. For more information on conversion and retention of nineteenth-century Mormon converts, see Jared M. Halverson, “‘To Make Ready a People Prepared for the Lord’: Italy’s Waldensian Saints as a Case Study on Conversion” (Master’s thesis, Brigham Young University, August 2005).

[2] Fiorella Massel, “Contributo alla Storia del Giornalismo Valdese,” Tesi di Laurea in Storia del Risorgimento (Turin: Università degli Studi di Torino, Facoltà di Lettere e Filosofia, 1980–81), 20.

[3] Tourn, Viaggiatori Britannici alle Valli Valdesi, 235–37.

[4] Lorenzo Snow, La Voix de Joseph (Turin: Ferrero et Franco, 1851), 73–74. This pamphlet was published in English, in abbreviated form, the following year; see Lorenzo Snow, The Voice of Joseph (Malta: n.p., 1852), 18.

[5] Lorenzo Snow, La Voix de Joseph, 74–75. See also Snow, The Voice of Joseph (1852), 15-16.

[6] Millennial Star, 9 July1853, 436–41.

[7] Millennial Star, 3 October 1857, 634.

[8] Millennial Star, 29 May 1858, 347.

[9] Woodard, “Diaries, 1852–57,” 30 September 1857.

[10] Millennial Star, 1 April 1854, 205.

[11] Eric Hoffer, The True Believer (New York: Harper Collins, 1964), 95–96.

[12] Millennial Star, 8 March 1856, 156.

[13] Millennial Star, 8 March 1856, 154.

[14] Millennial Star, 4 April 1857, 219.

[15] Millennial Star, 21 July 1855, 454.

[16] Millennial Star, 21 July 1855, 454.

[17] Millennial Star, 8 March 1856, 154.

[18] Brigham Young, in Journal of Discourses, 2:251–52.

[19] Brigham Young to Orson Pratt, 30 August 1855, Brigham Young letterbooks, Church History Library. Cited in Paul H. Peterson, “The Mormon Reformation” (PhD diss., Brigham Young University, 1981), 34.

[20] Millennial Star, 11 November 1854, 708.

[21] “Rapport Annuel,” Deliberations du consistoire 1824–57, Pramol (1853).

[22] “Notiste Religiose,” 28 October 1853, La Buona Novella, 823–24.

[23] Stokoe, “The Mormon Waldensians,” 57.

[24] Stokoe, “The Mormon Waldensians,” 59 (citing Millennial Star, 8 October 1853, 671).

[25] Stokoe, “The Mormon Waldensians,” 58–62.

[26] Ferrero, “L’emigrazione,” 95–97.

[27] Archivio di Stato di Torino, Registro delle Insinuazioni di Pinerolo, 1854, vol. 1049, 477–78.

[28] Archivio di Stato di Torino, Registro delle Insinuazioni di San Secondo, 1854, vol. 562, 157–59.

[29] Stokoe, “The Mormon Waldensians,” 59–60.

[30] See Stokoe, “The Mormon Waldensians,” 112–14.

[31] Archivio di Stato di Torino, Registro delle Insinuazioni di Pinerolo, 1853, vol. 1046, 425–26.

[32] Stokoe, “The Mormon Waldensian,” 57–80.

[33] Insinuasioni di San Secondo, 1854, vol. 562, 157–59.

[34] Millennial Star, 28 January 1854, 61–62.

[35] Francis, Journal, 11 February 1855, 77.

[36] Millennial Star, 28 January 1854, 62.

[37] Millennial Star, 25 March 1854, 191.

[38] Autobiography of Daniel Bertoch (c. 1919), Utah State Historical Society, Salt Lake City. See also Michael W. Homer, On the Way to Somewhere Else: European Sojourners in the Mormon West, 1834–1930 (Spokane, WA: Arthur H. Clark, 2006), 90–94; Michael W. Homer, “An Immigrant Story: Three Orphaned Italians in Early Utah Territory,” Utah Historical Quarterly 70, no. 3 (Summer 2002): 196–214.

[39] Autobiography of Daniel Bertoch (c. 1919), Utah State Historical Society.

[40] Robert L. Campbell was a twenty-nine-year-old Scottish convert from Glasgow. He was also the president of the company of Latter-day Saint emigrants aboard the John M. Wood.

[41] Autobiography of Daniel Bertoch.

[42] Andrew Jenson, Latter-day Saints Biographical Encyclopedia, 4 vols. (Salt Lake City: Andrew Jenson History Company, 1901–36), 2:462.

[43] Millennial Star, 1 April 1854, 205.

[44] Domenico Maselli, Tra Risveglio e Millennio. Storia delle Chiese Cristiane dei Fratelli, 1836–1886, vol. 3 of Storia del Movimento Evangelico in Italia (Torino: Claudiana, 1974), 89–90, n. 38b.

[45] Joseph Malan to Jean Pierre Revel, 29 August 1854, Lettres de M. Joseph Malan, 1850–1859, Archivio della Tavola Valdese, Lettera, n. 67.

[46] Joseph Malan to Jean Pierre Revel, 18 September 1854, Lettres de M. Joseph Malan, 1850–1859, Archivio della Tavola Valdese, Lettera, n. 69.

[47] Fancis, Journal, 11 February 1855, 77.

[48] See “Emigration Records and Ship Roster,” Church History Library.

[49] Journal of Samuel Francis, 7 March–9 March 1855, Church History Library.

[50] Luigi Ballatore, Storia delle ferrovie in Piemonte, dalle origini alla vigilia della seconda guerra mondiale (Turin: Biblioteca Economia, 1996), 27–37, 101–3.

[51] Stanley B. Kimball, Historic Sites and Markers along the Mormon and Other Great Western Trails (Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1988), 131–32.

[52] “Comunicazioni con l’estero, 1836–1899,” Faldone 1562, Archivio Storico del Comune, Torre Pellice.

[53] The original spelling of this name was Lageard, but in church records it appears as Lazald.

[54] Richards, The Scriptural Allegory, 297–310; Stokoe, “The Mormon Waldensian,” 74.

[55] “Rapport de 1856 sur l’Estat de l’Eglise des Ecoles et des Pauvres, `a l’usage de la Table,” anno 1855, fatto dal Pastore Jean Jacques Vinçon, 2 May 1856, in Délibérations du consistoire 1824–1857, vol. 98, Archivio della Tavola Valdese.

[56] Lettere ricevute dalla Tavola, Cartella 48, anno 1857, lettera 93, Fatto dal Pastore Jean Jacques Bonjour, Archivio della Tavola Valdese.

[57] Scott Alan Carson, “The Perpetual Emigrating Fund: Redemption Servitude and Subsidized Migration in America’s Great Basin” (PhD diss., University of Utah, 1998), 448.

[58] Francis, journal, 17 June and 19 July 1855, Church History Library.

[59] Millennial Star, 2 August 1856, 490.

[60] See George B. Watts, The Waldenses in the New World (Durham: Duke University Press, 1941). There were twenty-seven baptisms among the Waldensians in 1854, another twenty-six in 1855, and only eight in 1856; see “Record of the Italian Mission,” Church History Library.

[61] Watts, The Waldenses in the New World, 46.

[62] Watts, The Waldenses in the New World, 47.

[63] Stephen Malan Record, Malan Book of Remembrance, vol. 1, 101–2, Church History Library. See also Homer, On the Way to Somewhere Else, 86–90.

[64] Richard C. Roberts and Richard W. Sadler, A History of Weber County (Salt Lake City: Utah State Historical Society, 1997), 60.

[65] 3 December 1854, Wilford Woodruff’s Journal, 1833–1898 Typescript, ed. Scott G. Kenney (Midvale, UT: Signature Books, 1983), 4:292.

[66] Dale Morgan, The Great Salt Lake (New York: The Dobbs-Morrell Company, 1947), 254–55.

[67] Roberts and Sadler, A History of Weber County, 84–85.

[68] Homer, On the Way to Somewhere Else, 92.

[69] Homer, On the Way to Somewhere Else, 92.

[70] The Perpetual Emigrating Fund Ledger confirms that the Bertoch family was initially indebted “for the cost of transportation of family from Liverpool to Salt Lake City” in the amount of $296.50. This was reduced by “cash paid on a/

[71] Biography of James Bertoch (c. 1923), in the possession of Michael W. Homer; Autobiography of Daniel Bertoch (c. 1919), Utah State Historical Society; Daniel Bertoch to James Bertoch and Anne Cutcliff Bertoch, 14 February 1922, copy in possession of Michael W. Homer.

[72] Mulder, “Mormon Angles of Historical Vision,” 55; Autobiography of Daniel Bertoch (c. 1919), Utah State Historical Society. Large flat-bottomed boats were used to transfer stock between the mainland and the island.

[73] Homer, On the Way to Somewhere Else, 93.

[74] Homer, On the Way to Somewhere Else, 93.

[75] Homer, On the Way to Somewhere Else, 93.

[76] Homer, On the Way to Somewhere Else, 94.

[77] Homer, On the Way to Somewhere Else, 94.

[78] Morgan, The Great Salt Lake, 256; Francis A. Kirkham and Harold Lundstrom, eds., Tales of a Triumphant People: A History of Salt Lake County, Utah (Salt Lake City: Daughter of Utah Pioneers, 1947), 271–72; Joseph Toronto: Italian Pioneer and Patriarch, 23.

[79] Stokoe, “The Mormon Waldensians,” 81–103.

[80] For a documentary history of the Utah war, see William P. McKinnon, At Sword’s Point, Parts I and IIm A Documentary History of the Utah War (Norman, OK: Arthur H. Clark, 2008, 2116).

[81] Mulder, “Mormon Angles of Historical Vision,” 275.

[82] Brigham Young to Orson Pratt, 12 August 1857, and Samuel W. Richards to Henry Richards, 16 September 1857. Brigham Young Papers, Church History Library.