Peter in the House of Tabitha: Late Antique Sarcophagi and Christian Philanthropy

Catherine C. Taylor

Catherine C. Taylor, “Peter in the House of Tabitha: Late Antique Sarcophagi and Christian Philanthropy,” in The Ministry of Peter, the Chief Apostle, ed. Frank F. Judd Jr., Eric D. Huntsman, and Shon D. Hopkin (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2014), 191–209.

Catherine C. Taylor was adjunct faculty in the Department of Ancient Scripture at Brigham Young University when this was written.

In the Acts of the Apostles 9:36–41 are accounts of Peter’s miracles in Lydda and Joppa; namely, the healing of Aeneas and the raising of Tabitha prior to the conversion of Cornelius and the opening of the Gentile mission. Luke, the author of Acts, situates Peter’s journeys and miracles directly following the conversion of Saul and the subsequent Pauline ministry. Peter’s authority is the clear marker for the inauguration of the mission to the Gentile nations[1] and results in kindling faith in Christ and regional conversion. While these broad-ranging themes make the Petrine miracles coherent as a whole, there are very important individual themes that help illuminate early Christian reception of these accounts. The aim of this paper is not to address the overarching and even contextually divisive issue of Gentile conversion, but to focus instead on the single illustration of Peter in Tabitha’s house.

The similitude of the Apostle’s action to Jesus’ own raising of the daughter of Jairus by his command “Talitha cumi,”[2] “Damsel, . . . arise” (Mark 5:41), echoes in Peter’s familiar and imperative command “Tabitha, arise” (Acts 9:40). Peter’s interaction demonstrates the archetypal attentiveness and care for women that Jesus modeled for his followers. This same close attention and interaction was also demonstrated in the memorialization of the lives of late antique Christian women. With regard to this particular miracle, scriptural text and its earliest visual representations reveal how virtuous matronage of late antiquity was a force of public legitimization for the cause of Christianity and the elevation of its philanthropic profile. Latter-day Saint women today carry on this same heritage by relieving suffering wherever it is found and expanding hearts and minds through their spiritual gifts and humanitarian service.

As early as 1989, President Thomas S. Monson called attention to the account of Peter’s healing of Tabitha:

Now there was at Joppa a certain disciple named Tabitha, which by interpretation is called Dorcas: this woman was full of good works and almsdeeds which she did.

And it came to pass in those days, that she was sick, and died: whom when they had washed, they laid her in an upper chamber.

And forasmuch as Lydda was nigh to Joppa, and the disciples had heard that Peter was there, they sent unto him two men, desiring him that he would not delay to come to them.

Then Peter arose and went with them. When he was come, they brought him into the upper chamber: and all the widows stood by him weeping, and shewing the coats and garments which Dorcas made, while she was with them.

But Peter put them all forth, and kneeled down, and prayed; and turning him to the body said, Tabitha, arise. And she opened her eyes: and when she saw Peter, she sat up.

And he gave her his hand, and lifted her up, and when he had called the saints and widows, presented her alive.

And it was known throughout all Joppa; and many believed in the Lord. (Acts 9:36–42)

President Monson asked several poignant questions about the account of Peter and Tabitha that are applicable today: “Would it not be ever so sad if such a window to priesthood power, to faith, to healing, were to be restricted to Joppa alone? Are these sacred and moving accounts recorded only for our uplift and enlightenment? Can we not apply such mighty lessons to our daily lives?”[3] These questions of reception are prophetically the same today as they were for the earliest Christians. The particular focus of this paper remains on this query, “Are these sacred and moving accounts recorded only for our uplift and enlightenment?” The visual iconography and texts that were part of the early church provide us with a clear and didactic answer to that question. Not only was the account of Peter and Tabitha important as part of a larger narrative, it was used to underscore faithful female industriousness and the generosity of their Christian households.

The story of Peter in Tabitha’s house has traditionally been used to highlight widows’ experiences in the early church or to illustrate charitable love within early Christian communities.[4] However, little attention has been given to the reception of early Christian images and text that address the iconography of Peter and the household of Tabitha. It is worth looking closely at sarcophagi with Christian iconography, including that of Peter raising Tabitha from the dead, because they demonstrate the devotion of late antique Christians, whose faith “was so certain in the face of death that it admitted no doubts and no alternative thoughts and feelings.”[5]

One underlying factor that the textual account has in common with the visual representation of Peter raising Tabitha is the rhetorical nature of both. The viewer is asked, in the questioning context of text and image, something very striking about late antique reception of scripture. Namely, how and why were text and image used as points of commemoration and memorialization in the lives of Christian believers? While Peter is most frequently represented in art associated with his apostleship to the Lord Jesus Christ, the account of Peter raising Tabitha illuminates the Apostle’s ministry at the very cusp of Christianity’s unhindered spread.

Peter in Tabitha’s House

Peter’s interactions with Aeneas, Tabitha, and Cornelius can be seen as a series of culminating events in which Cornelius’s conversion marks that pinnacle moment when Peter establishes the blessings of Israel amongst all faithful Gentiles. For Peter, Cornelius, and the Gentile world, Jesus Christ becomes Lord of all. However, privileging the visit of Peter to Caesarea necessarily overshadows his visits to Lydda and Joppa, without regard for the fact that, literally and figuratively, Peter doesn’t make his way to Caesarea unless he traveled the road through Lydda and Joppa.

The second miracle of these three, described in Acts 9:39–41, finds Peter the chief Apostle in the city of Joppa, having been summoned to Tabitha’s house. According to Acts 9:31, which directly precedes the trilogy of healing and conversion events, it becomes clear that the churches in Galilee and Judea were established in relative peace, and Luke witnesses the progress of the church under the authority of Peter.[6] The deliberate choice of Peter’s journeying is not recorded according to happenstance or to merely provide fodder for his culminating interaction with Cornelius. The author of Acts has necessarily focused attention on this series of three Petrine interactions by specifically choosing to include them, perhaps over others. In a similar gesture, this study will examine Peter’s interaction with Tabitha at an interdisciplinary crossroad, where Acts 9 meets the earliest visual representations of Peter in Tabitha’s house.

Luke introduces Tabitha, whose Aramaic name translated into Greek is Dorkas, with both names meaning “gazelle.” Tabitha’s character has been associated with the gazelle as a symbol of a nurturer or life giver.[7] A commentary on the steady faith of the gazelle is found in 2 Samuel 22:34 and Psalm 18:3: “God has made my feet like gazelles and made me stand on my high places,” whereas the speed of the gazelle is noted in The Targum of Canticles 2:9 and 2:17 as Yahweh “runs like a gazelle” to save Egypt and Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob are “swift in worshiping Him, as a gazelle.”[8] It is easy to see how Peter’s attentions to Tabitha were useful in expanding Christianity’s borders beyond Jewish believers. His miracle was a symbol of love, compassion, service, and graciousness, demonstrated for Jewish Christians or proselytes to emulate as they interacted with new communities of Christian converts. Tabitha’s example of Christian acceptance is an important and underlying foundation to charitable acts during the earliest years of the church and its continued historicity during the fourth century.

Tabitha’s story is quintessentially the story of faithful women whose actions help establish a model of valiancy meant for emulation in the emerging Christian borderlands. Joppa or Jaffa was an ancient Philistine maritime city conquered by David and ruled over by Solomon. It was set in the Plain of Sharon and had long been associated as a Mediterranean seaport and hub of commerce.[9] Joppa was a crossroads, a borderland, but also a place specifically associated with materials used for the building of the temple. Joppa is twice used in the Old Testament to receive materials for the temple of Jerusalem: first as a port of landing for the cedars of Lebanon (see 2 Chronicles 2:16) and second during the reign of Cyrus, when it was also a landing port for materials intended for the reconstruction of the temple (see Ezra 3:7). During the first century, Joppa was home to Jews, Jewish Christians, and Gentiles. It was also home to Tabitha, whose tomb is still visited as part of Christian pilgrimage.[10] Luke seems to emphasize the geography of the Holy Land,[11] including Joppa, as a way of perhaps setting it apart or making it special from the rest of the world. Tabitha’s merit amongst her community is also associated with material goods: coats and garments or tunics and mantles, articles of material substance given to her household, the widows, and the poor are depicted in a series of three sarcophagi from the fourth century.

Art and Artifactual Data

Turning our attention to art, artifacts, and material culture has long been a practice for scholars of late antique Christianity. Art has been used to augment our understanding of the New Testament text with little-known insights occasionally coming to light through the historical reception of artistic representation. The study of sarcophagi has long focused on iconographic categories that aligned across the divide of pagan and Christian subjects. However, the understanding of each category can help illuminate the development of the other.

Elaborate and figural decorated sarcophagi from the end of the second century to the beginning of the fifth century represent a massive oeuvre numbering thousands with even tens of thousands of non-complex designed sarcophagi that remain from the period. These sarcophagi vary in richness and type. Many problems are inherent in the use of sarcophagi for historical reference, including issues of original site destruction and the loss or absence of epigraphic data. However, there is still much evidence toward visual reception that can be gleaned from patterns of iconography.

Sarcophagi were used, often for multiple family members, reused, and even reappropriated for saintly reliquaries or displayed as spolia decoration on the facades of later churches.[12] Sarcophagi were sometimes decorated to represent a type of micro-architectural box used to house one or more bodies of deceased persons,[13] often members of the same familial household. Despite the absence of an integrated context for most sarcophagi, it remains relevant that sarcophagi were meant to house and protect the deceased and were designed for view by the living.[14] Furthermore, sarcophagi provide us with our richest single source of late antique Christian iconography and immediately cross into the realm of the most personal and even private of contexts; death and the memorialization of life.

The space available for visual representation on sarcophagi is inherently limited and literally set in stone with images meant to be read and understood as messages, even for those without literary training. So, when Peter is featured on a sarcophagus in a singular role in a particular narrative, it becomes rather evident that the viewer is to read the story through the lens of its specificity. Peter’s association with Tabitha, underscored by his apostleship, legitimizes the Christian household for the late antique audience. His presence and the miracle wrought through the name of Jesus give attention, credence, and validity to the model of matronly virtue, borrowed from Roman social mores and adapted for Christian use.

Only recently have scholars started to revisit the patterns of iconography available on late antique sarcophagi, objects necessarily restricted in spatial field and with a relatively limited repertoire of iconographic types.[15] These types were, however, subject to the varied and creative license of the artisan in their execution. The sarcophagi discussed here are Roman in style and provenance with Christian themes, a dynamic that immediately calls our attention to the issues of the faithful demonstration of piety and Christian apology.

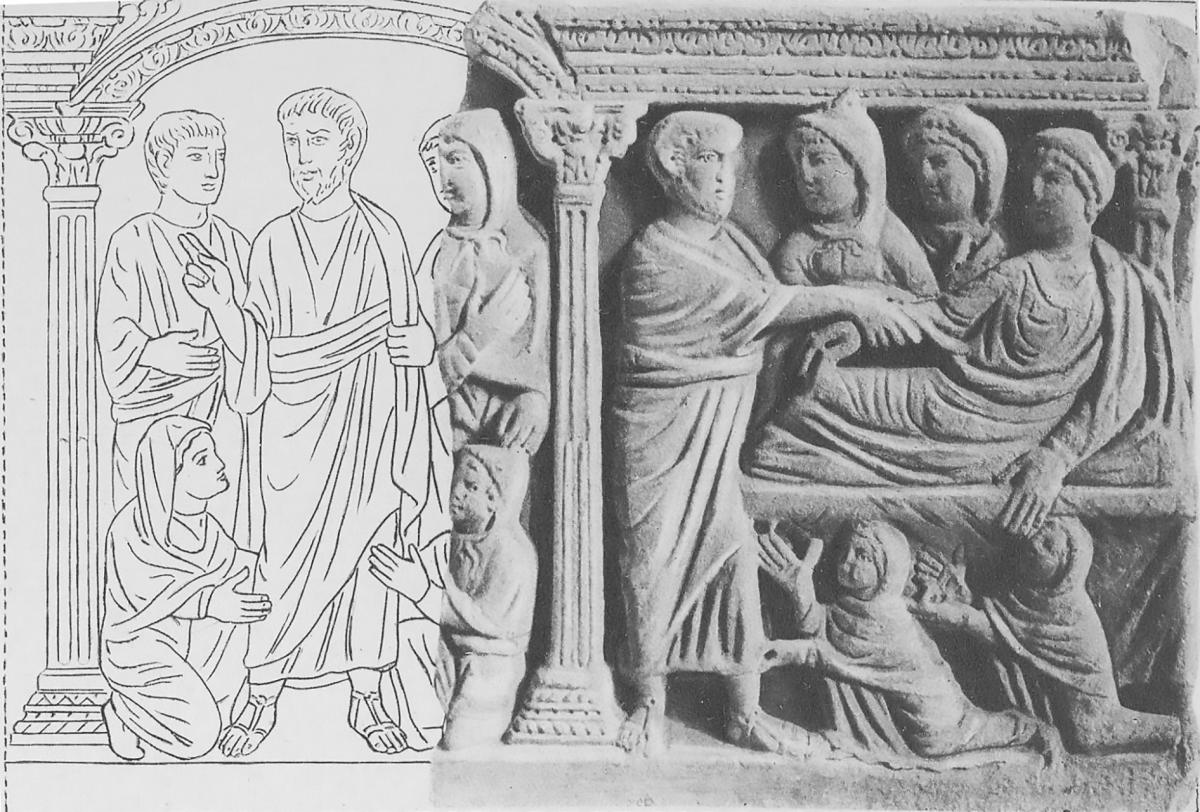

A fourth-century sarcophagus fragment, today in the Musée de L’Arles Antique (fig. 1), features two scenes divided by a fluted Corinthian column; the first scene includes two female figures, one kneeling and one standing. They are both wearing Phrygian-style snood caps, a phenomenon to be discussed later in this paper. In the scene below, the Apostle Peter is shown raising Tabitha from the dead. Her figure fills the picture plane and is elegantly positioned in a seated recline with Peter grasping her wrist with both hands to raise her. She is surrounded by four female figures; two stand behind Tabitha’s bed each wearing a snood. The other two wear a traditional palla and stola and are kneeling beneath the raised bed platform. The figures are scaled according to hierarchal proportion and eagerly gesture toward Peter. The woman nearest Peter touches the hem of his garment. The high-relief figures in the scene are framed with an architectural cornice and Corinthian columns. There is no background detail. The sarcophagus front is from Roman Gaul with a likely provenance in Arles prior to the reign of Honorius (AD 395–423).[16]

Fig1. Raising of Tabitha, sarcophaus fragment, Musee de La'Arles Antique, 4th century AD. Giuseppe Wilpert. Rome: Pontificio Istituto di Archeologia Cristiana, 1929. Plate CXLV, no 6.

Fig1. Raising of Tabitha, sarcophaus fragment, Musee de La'Arles Antique, 4th century AD. Giuseppe Wilpert. Rome: Pontificio Istituto di Archeologia Cristiana, 1929. Plate CXLV, no 6.

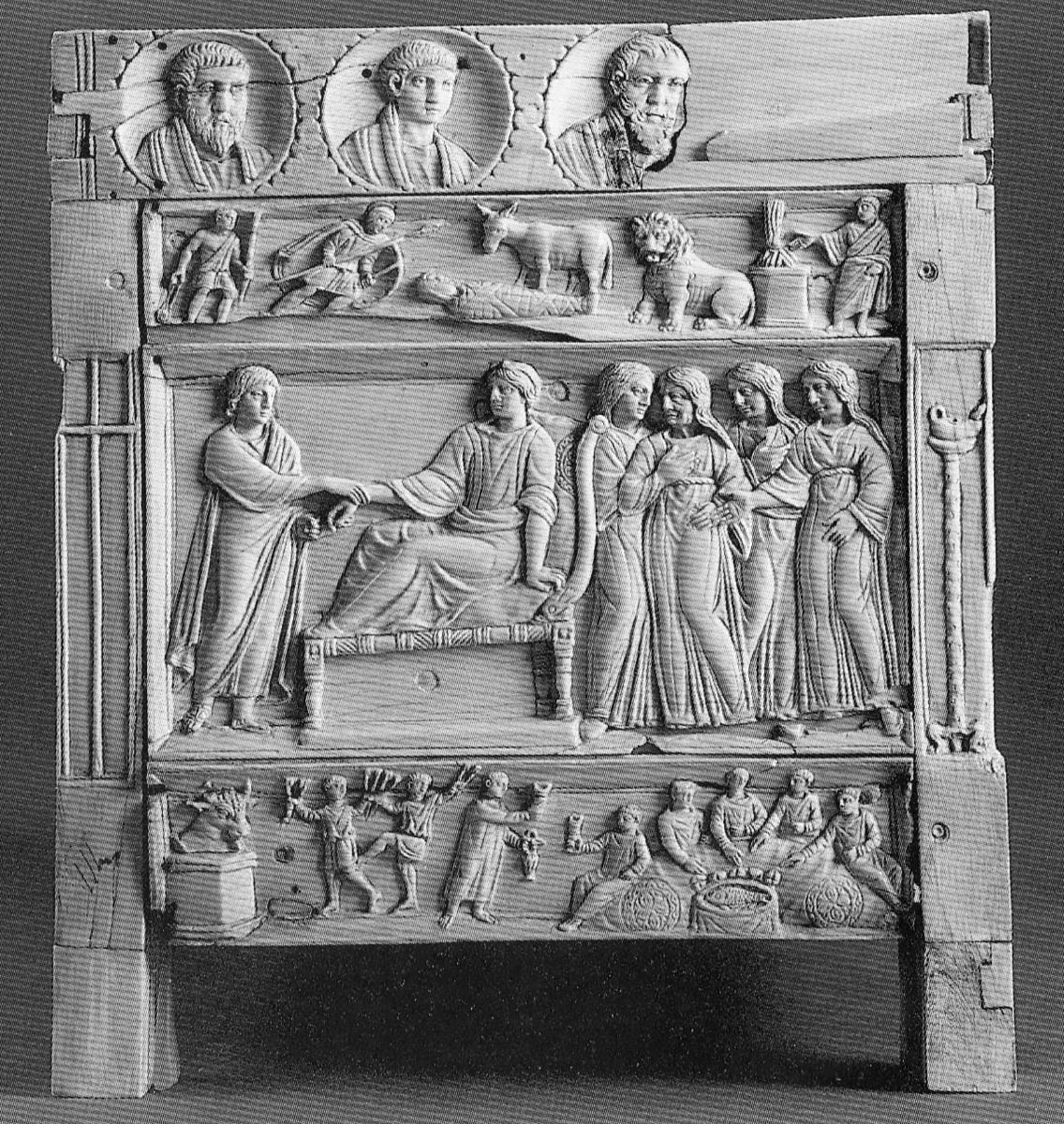

Another fourth-century sarcophagus (fig. 2), today at Assunta Cathedral in Fermo, Italy, shows a series of five scenes along its frontal frieze, all separated by a series of architectural pediments and arches supported by columns.[17] The central panel shows Christ flanked by Cain and Abel with their respective offerings of lamb and sheaf.

Fig. 2. Sarcophagus, Assunta Cathedral, Fermo, Italy, 4th century AD. Giuseppe Wilpert. Rome: Pontificio Istituto di Archeologia Cristina, 1929, Plate CXVI, no. 3.

Fig. 2. Sarcophagus, Assunta Cathedral, Fermo, Italy, 4th century AD. Giuseppe Wilpert. Rome: Pontificio Istituto di Archeologia Cristina, 1929, Plate CXVI, no. 3.

The vignettes above show a story continuum related to Peter. Each scene relates to the merits of individual offerings, including sacrificial offerings, good works, and the actual life of the Apostle. On the far left we find Peter standing between a disciple and a widow with another widow supplicating him at his feet, symbolic of the widows who show Peter the fruits of Tabitha’s generous offerings. The continuous narrative sees the story to its conclusion with Peter grasping Tabitha’s arm and raising her. Now on her feet, Tabitha is dressed as a traditional matron, while another male disciple stands witness to the miracle at Peter’s left. To the immediate right of Christ in the central panel, we find the narrative sequence describing Peter’s miraculous escape from prison as the fully armed soldiers are found sleeping in the fourth panel and Peter is being led away by a wingless angel in the fifth.

The most detailed of our three sarcophagi is the fourth-century Roman-style example today at the Church of Ste. Madeleine in Saint Maximin, France (fig. 3).[18] The columnar sarcophagus is large and elaborate with scenes depicting Christ healing the centurion’s servant, healing the man born blind, Christ’s Resurrection represented symbolically, Christ prophesying the denial of Peter, and the miracle of the woman with an issue of blood. All of these scenes are Christ-centered along the main frieze of the sarcophagus with the ends being significantly different in subject matter. It was not an uncommon practice for the short ends of a sarcophagus to be carved in lower-relief scenes, perhaps even specified or chosen by the patron. On the left end we find Peter raising Tabitha (fig. 4) in a well-appointed room, complete with draperies, a luxurious bed, an architectural column, and a pipe organ.

Fig. 3-4. Sarcophagus front and Raising Tabitha detail, Church of Ste. Madeleine, Saint Maximin, France, 4th century AD. Giuseppe Wilpert. Rome: Pontifcio Istituto di Archeologia Cristiana, 1929. Plate CXLV, nox. 5,7.

Fig. 3-4. Sarcophagus front and Raising Tabitha detail, Church of Ste. Madeleine, Saint Maximin, France, 4th century AD. Giuseppe Wilpert. Rome: Pontifcio Istituto di Archeologia Cristiana, 1929. Plate CXLV, nox. 5,7.

Tabitha is depicted here as a type of new philanthropic exemplar as demonstrated in the varied figures she is shown helping. Figures of the poor are diminutively small and kneel or sit near the side of the bed. Two women (widows) are standing behind Tabitha with their gaze and gestures directed toward her. Tabitha is proportionately large and fills the picture plane. Her dress is a simple stola without the traditional palla to veil her head. Her hair is neatly coiffed, perhaps covered, and prepared for burial. In addition to the two widows standing behind Tabitha’s bed, we find three smaller figures representing the poor in the foreground next to Tabitha’s bed. Indeed, they are small, according to the standards of hierarchy of scale, precisely because they are poor and are of a distinctively different social class when compared to Tabitha and the stately, matronly widows. Tabitha’s left hand rests on the head of the small female figure at her left who supports a seated, naked figure with her hands and right knee. The third kneeling figure is set apart from the others and reaches out to touch the hem of Peter’s garment: a gesture similar to that of the woman with an issue of blood touching Christ’s garment. This third figure wears a peculiar head covering like the female figures on the sarcophagus from Arles (fig.1). This pointed snood is akin to the Phrygian cap of the foreign magi who are often shown wearing similar hats in artistic representations of the Adoration of the Magi. The widows and the woman with the naked boy are easy to situate into the Levitical laws regarding the care of the widows and the fatherless.[19] However, the inclusion of the Phrygian capped figures indicates that Tabitha’s generosity was considered, within the fourth century, to include the foreign poor as well, a notion that coincides with the nature of diverse port cities like Joppa.

At the opposite end of the sarcophagus, we find an extraordinary depiction of the deceased as a female orant figure posed in a formalized portrait of prayer (fig. 5). She is dressed with matronly finesse and stands in a contrapposto pose between two trees with a large scrinium at her feet.

Fig. 5. Sarcophagus detail, Female Orant, Church of Ste. Madeleine, Saint Maximin, France, 4th century AD. Giuseppe Wilpert. Rome: Pontificio Istituto di Archeologia Cristiana, 1929. Plate CCXVII, no. 1.

Fig. 5. Sarcophagus detail, Female Orant, Church of Ste. Madeleine, Saint Maximin, France, 4th century AD. Giuseppe Wilpert. Rome: Pontificio Istituto di Archeologia Cristiana, 1929. Plate CCXVII, no. 1.

The choice of detail here may indicate that the deceased was a lettered woman, perhaps with resources to become educated.[20] We can relate the scenes on the ends of the sarcophagus to each other. Both display Christian women of some means, respectively represented for their good works and lauded for their piety. This visual connection between the textual past and the visual present became the new model for female Christian householders.

On the Ste. Maximin sarcophagus, Christian iconography was employed alongside scenes presenting the deceased as an orant, pious believer. This combination served to close the idealized gap between the character and meaning of the biblical scenes and the attributes, idealized though they may be, of the deceased, their associates, and the anonymous viewer. Deceased orant figures could be pictured praying on behalf of their spouse or kinsmen. It is equally valid to argue that she was praying for her own salvation, armed with the example of Tabitha as her guide. If the scene of the deceased is to be read as an individual interpretation, a more general image of devotion and salvific hope is in order. Nevertheless, evoking the notion that Christianity was connected with social status, at least where decorated sarcophagi were concerned, was a popular trend.

Clearly, one of the most divisive issues in the book of Acts was the status of Gentiles amongst Christian communities. By examining this series of fourth-century sarcophagi, produced with Roman provenance, we find that the iconography of Tabitha and her association with varied classes of people and with Peter takes on a particular agenda. It is not hard to imagine that these images moved beyond the mere illustration of Christian storylines to a decisive display of new legitimacy for new converts amongst Jewish communities, Gentiles, and foreigners alike, that aligned themselves with the respectable, honored, and sanctioned household of the faithful, even the household of faithful women.

Although we are only examining three sarcophagi here, they should not be dismissed, regardless of their initial singularity in image or scope. Scenes on sarcophagi act as points of historic reference whether they demonstrate actual events, idealized events, or even imaginary events; they give us insight into the paradigms of their day. These scenes reference real people, typologies of real people, and the ideals and values chosen to commemorate them in death.

Patristic Historicity and Fourth-Century Context

Peter’s association with Tabitha, perhaps a widow herself, and the widows within her care is directly related to fourth-century patristic language with regard to widows, their social status, and their official treatment within the early church. The status of unmarried women, widows in particular, seems to have changed over time. By the beginning of the second century, there was a body of Christian widows large enough to require official statements on how they should be cared for and their role in performing charitable works.[21] Additionally, there was some censure directed at the behavior of indiscreet widows in Polycarp’s Letter to the Philippians, in which he adjures them to “refrain from all slander, gossip, false witness, love of money.”[22] That there is some talk of the inappropriate behavior of widowed women in gossiping, idleness, and meddling would either indicate that it was indeed happening, or that it was perceived as happening by those writing about it, and that this behavior was seen as a threat.

In the third-century treatise Didascalia Apostolorum, widows are again censured not only as gossips and chatterers, but also as women who use their circumstances to unfairly profit by it; those who “are no widows, but wallets, and they care for nothing but to be making ready to receive” and “impatient to be running after gain.”[23] Widows with means and the ability to make money are addressed as a threat, perhaps without merit. However the tone of rhetoric towards women in the third century changes dramatically in the fourth century when those same women are lauded for their status as widowed, wealthy ascetic types that have dedicated their lives and fortunes to God. Women like Macrina the Younger and Melania the Elder are lauded as young widows who dispensed of their immense wealth among the poor.[24] One of the most notable women, also not forgotten, was Olympias of Constantinople, who, when widowed at twenty-one, dedicated her wealth to the patronage of a women’s community adjacent to Hagia Sophia.[25] The official tone of patristic rhetoric changes from condemnation to commemoration as John Chrysostom, Olympias’s friend, will comment on Tabitha’s material benevolence. Chrysostom acknowledges Tabitha’s house and indirectly comments on its wealth through counterpoint by describing how “it was not her house that proclaimed her wealth, nor the walls, nor the stones, nor the pillars, but the bodies of widows furnished with dress, and their tears that were shed, and death that played the runaway, and life that came back again.”[26]

Ambrose (AD 340–97) in his Concerning Widows, affirmed that widowhood is very close in status and esteem to that of virginity, and that both are to be preferred over the married state.[27] He uses examples of widows from the Old and New Testaments as bastions of social good and asserts that only idolaters condemn widows.[28] Without condemning second marriages outright, Ambrose encourages those under his stewardship to embrace widowhood as the highest good available to them. In chapter 1 of his commentary, he emphasizes the virtues of widowhood and specifically discusses the expectations of widows’ hospitality; that it should not be limited in its scope. To illustrate his point, he exemplifies the widow of Sarepta who gave all she had to Elijah, the prophet of God.[29] From its inception it was not uncommon for women, especially wealthy widows, to give their wealth to the church.[30]

In his praise of widows, Ambrose elevates the status of widows in a public way by associating them with heavenly honor and virtue. In fact, no more than a century following Ambrose, we find evidence that the Christian elite is being addressed in letters and household manuals, like the Liber ad Gregoriam in palatio, written specifically for the Christian Domina, who could be encouraged to distribute her independent wealth and property with the aid of her spiritual leaders.[31] There is a direct correlation between the language associated with widowhood and virginity that will ultimately undermine the power of familial social structures, estates, and inheritances through church acquisition of such properties.[32]

Classic acts of charity, providing for widows and orphans, were true religion in the early Christian world and were closely related to ideals of personal perfection. Female patrons had perhaps become so influential in the early Christian world that by the fourth century, the church took decisive action and established a formulaic ideal for female patronage as witnessed in Ambrose’s treatises. The church gladly acted as beneficiary to whom a large portion of property as well as liquid assets would eventually come. Ambrose is certainly influenced by the example of his own ascetically minded sister, Marcellina, to whom he dedicates Book III of his De Virginibus ad Marcellinam or On Virgins. Ambrose’s language in his theological treatises reads much like a coercive capital campaign speech directed at wealthy widows and was effective in underpinning Christian ideas regarding true charity and philanthropy.

The Philanthropy of Death and Women’s Households

Female family members, in particular widows, were known to be heads of household, a circumstance that was mitigated early by the church. Some of our best evidence for the influence of virtuous matrons whose resources impacted the spread of Christianity comes to us from the New Testament.[33] In a world where patronage was essential to maintaining social mores, it is revealing to find matrons who not only managed a household but also acted as benefactors beyond their immediate family in the pattern of Tabitha. Matronae in the early Christian tradition are evidenced in text and image. For example, Anicia Faltonia Proba clearly viewed Christianity as a legacy “to be handed down within families, rather than a call to abandon family life.”[34] Furthermore, there are late-fourth-century inscriptions lauding her role as familial matron: “Anicia Faltonia Proba, trustee of the ancient nobilitas, pride of the Anician family, a model of the preservation and teaching of wifely virtue, descendant of consuls, mother of consuls.”[35] Other women, not quite so conspicuous in their patronage, are visually represented for their charitable guidance toward pious matrons. For example, the Catacombs of Domitilla in Rome are home to a fourth-century lunette fresco depicting Saint Petronilla, the legendary daughter of Peter, leading Veneranda, a matron worthy of veneration for her Christian faith, toward paradise, in a scene complete with a large scrinium.[36]

While female patronage within households and within secular settings has not been adequately documented, we do have a number of sources that identify Imperial Christian women of the fourth century who follow in the footsteps of Constantine’s mother Helena in undertaking such a course for the church. Women like Aelia Flavia Flaccilla, Galla Placidia, Eudoxia, and Pulcheria are important examples because they were conspicuous in their patronage of the church—an example not lost on Christian women of various social classes.[37] It is clear that the influence of female householders during the fourth century was anything but an anomaly in late antique Christianity. Part of the reason they were so conspicuous and crucial to the cause of Christianity was precisely because of their ability to provide money, and the substantive resources of their household, if not a church.

Fig. 6. Brescia casket, Museo di Santa Diulia, Brescia, Italy, 4th century AD. Courtesy of Wikipedia Commons.

Fig. 6. Brescia casket, Museo di Santa Diulia, Brescia, Italy, 4th century AD. Courtesy of Wikipedia Commons.

Early Christian communities seem to have had some difficulties coming to terms with the complexities of Christian charity. Their primary actions seem to have an eschatological concern over the structures of charitable behavior.[38] Bluntly told, the admonition to “sell that thou hast, and give to the poor” in Matthew 19:21 smacks loudly of ascetic practice, privileging the sanctification of the donor over the benefit to the poor. The emphasis of giving money or goods was closely connected with good works, as was alleviating suffering of all kinds. As Christ had taught the practice, it was to be done in secret, yet the dichotomy remained in which individuals were recognized as charitable by their fruits. For the early Christians, Peter raising Tabitha was in imitation of Jesus’ raising the daughter of Jairus, as is evident in the similar iconographic scene from the late-fourth-century Brescia casket with ivory panels (fig. 6). Just as Jesus was concerned over the affairs of women, so Peter is shown administering to Tabitha in recognition of her piety and good works.

Early Christian piety mimicked traditional Jewish piety, functioning through liturgical prayer and good works or benevolent deeds in order to provoke God to gracious action towards the intended supplicant.[39] Peter in Charitable Tabitha’s house is a fine model of recognizing and empowering women in their capacity to provide for others, not just in physical ways, but also in spiritual ways. Although Peter’s interaction with Cornelius is lauded as the inauguration of spiritual rebirth for the Gentile nations, Peter raising Tabitha from the dead is also salvific precisely because her household had already drawn the attention, by love and many almsdeeds, of those who would seek out Peter as the authorized servant of Jesus Christ. For Christians, “good works had no value unless they were motivated by love and were generally subsumed into the normal pattern of daily existence rather than singled out.”[40] But here we do have a particular model singled out— the capable household. Again we are presented with an impossible dichotomy and contrasting attitude; charitable gifts are required acts of piety, but a barren household cannot give. In this dichotomy we find the kind of supplicant desired and demonstrated in the rhetorical arrangement of art and text. The sarcophagi discussed here are evidence that up through the third and fourth centuries, late antique Christians chose the story of Tabitha not only as a trope of salvific memorialization, but also as a model for the new Christian household.

The status of widow seems to alleviate some concerns over material needs; it even demands that this group of women be cared for according to Levitical law.[41] Additionally, widows were in a unique position to host the Christian community, visitors, and guests.[42] Widows become distinctive for their acts of service and charity, but also become the focus of some censure precisely because of their influence on their communities. Widows, or more precisely, moneyed and lettered widows of the fourth century, retained a kind of independence that was publicly visible, respectable, and legitimizing, with widowed mothers in particular enjoying full legal status as mistresses of their households.[43]

While it is common to focus on Peter’s raising Tabitha from the dead as a miracle with the convenient effect of conversion,[44] commentators have long hesitated in defining the role of Tabitha as a model for late antique Christian women to emulate in performing acts of charity and bestowing goods on the widowed and others less fortunate. There is some discussion that Tabitha was likely a widow herself, but one that had means to maintain her household and expand her philanthropic reach to her community.[45] That Peter goes to Tabitha’s house to raise her is not just to demonstrate her ability as a Jewish Christian proselyte to expand the cause of Christianity, but to also normalize a new type of patron within the early church, that of the Matrona. The Roman sarcophagus, today in Marseilles, bears out evidence that by the fourth century, Christians have visually interpreted Peter’s raising of the deceased Tabitha with the hand of fellowship to a certain type of proselyte: the wealthy, influential, networked matron.

Conclusion

So, what do Christian relief images mean for patrons and viewers of the fourth century? It should be noted that the iconographic themes that we find on sarcophagi are also represented in number on other objects like fresco paintings, mosaics, jewelry, and textiles. As much as Christians were using sculpted relief images on sarcophagi to commemorate the dead, they were also living with these images, making connections with the meaningful representations of scripture in ways that went beyond mere ornament or illustration of Bible stories. Like their pagan counterparts, who largely used myth as an allegorizing feature on their sarcophagi, Christians also use artistic symbolism to celebrate the character and values of the deceased within their communities. Unlike their pagan counterparts, sarcophagi of the late third- and fourth-century take on a kind of seriousness associated with death. The very crossroads of death and tomb, image and text demonstrate that the living were engaged in “assuring themselves of the order of their own world.”[46] Furthermore, they speak to hopes, fears, passions, and spiritual aspirations as much as they do to idealized qualities, intellectual values, or virtues.

Like Jonah, saved from the belly of the whale, a certain allusion to the hopes of the deceased in a miraculous resurrection, so too is Tabitha presented amongst scenes of deliverance and miracles in a way that expresses hope in personal salvation for late antique Christians.[47] Paul Zanker, in his discussion of Christian sarcophagi, states, “Gone is any evocation of the achievements and merits of the deceased in the form of mythological allegories.”[48] Respectfully, I disagree and counter that a new kind of allegory, a new kind of Christian household, is here introduced and legitimized, in the case of the Tabitha sarcophagi, by Peter himself. We find that just as allegorizing and mythological themes had been indicative of the pagan paradigms of life, so too were Christian sarcophagi concerned with this life, but also necessarily and inextricably tied to salvation in the next life.

This kind of analysis answers the call by President Monson to look further at the scriptural narrative, its representation, and reception; to understand it as more than just an uplifting scripture story or enlightening narrative. This paper contributes new material concerning the memorialization of the late antique Christian dead and focuses our attention on the image of Peter legitimizing the role of the Christian household on sarcophagus images produced during the fourth century. Social standing did not cease to be an important factor for Christian believers. Instead, it became a source of social legitimacy that reinforced the new world of Christian empire with the rule of Constantine.

In Acts, we find Peter and Paul as those authorized to establish communities of believers through priesthood power and the outpouring of the Holy Ghost. For the men of Joppa who seek Peter to come to Tabitha’s house after he has healed Aeneas in Lydda, it is necessary that Peter be present as he restores Tabitha to life. Peter will “present” Tabitha as a “living one” to the widows and saints gathered at her house. Peter Strelan has noted that the verb “presented” is used in the same sense that Jesus was presented to the Lord in the temple, with the same impression of dedication and consecration present in the language.[49] Additionally, the Greek translation of paristano includes to stand beside, to exhibit, or to recommend. I submit that these defining characteristics were also present in images of Tabitha produced during the fourth century, with special attention focused on Tabitha as a matrona type, an able householder of means dedicated and consecrated to the spread of Christianity in all the world. By associating Tabitha visually with widows, the poor, and the foreigner, Luke brings this honored type of female patronage to the fore, all falling under the ultimate sanction of Peter.

Notes

[1] Joseph A. Fitzmyer, The Acts of the Apostles (New York: Doubleday, 1998), 443.

[2] Peter was present when Jesus raised the daughter of Jairus, making the similar imperative language and circumstances even more compelling.

[3] Thomas S. Monson, “Windows,” Ensign, November 1989, 69.

[4] Rick Strelan, “Tabitha: The Gazelle of Joppa (Acts 9:36–41),” Biblical Theology Bulletin 39, no. 2: 77–86.

[5] Paul Zanker and Björn C. Ewald, Living with Myths: The Imagery of Roman Sarcophagi (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), 265.

[6] A. E. Harvey, The New English Bible Companion to the New Testament (Oxford: Oxford University Press; Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1970), 434. See Johannes Munck, The Acts of the Apostles, The Anchor Bible (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1967), 87–88.

[7] Asa Strandberg, “The Gazelle in Ancient Egyptian Art: Image and Meaning” (PhD diss., Uppsala University, 2009), 9, 25–32.

[8] Philip S. Alexander, The Targum of Canticles (Collegeville, MN: The Liturgical Press, 2003), 105, 114; see Strelan, “Tabitha,” 80.

[9] Joseph A. Fitzmyer, The Acts of the Apostles (New York: Doubleday, 1998), 445.

[10] Siméon Vailhé, “Jaffa,” The Catholic Encyclopedia, vol. 8 (New York: Robert Appleton, 1910), 268.

[11] Robert M. Grant, “Early Christian Geography,” Vigiliae Christianae 46, no. 2 (1992): 105.

[12] Ja’s Elsner, “Introduction,” in Life, Death and Representation: Some New Work on Roman Sarcophagi, ed. Ja’+s Elsner and Janet Huskinson (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2011), 4.

[13] Edmund Thomas, “‘Houses of the Dead’: Columnar Sarcophagi as ‘Micro-architecture,’” in Life, Death and Representation, 387–436.

[14] Elsner, “Introduction,” 4. Extant historical context is extremely limited and may only be applicable to a few hundred sarcophagi of the many thousand that survive.

[15] Ja’s Elsner, “Image and Rhetoric in Early Christian Sarcophagi: Reflections on Jesus’ Trial,” in Life, Death and Representation, 359.

[16] Fernand Benoit, Sarcophages Paléochrétiens d’Arles et de Marseille (Paris: Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, 1954), 39.

[17] Giovanna Maria Gabrielli, I Sarcophagi Paleocristiani e AltoMedioevali delle Marche (Ravenna: Edizioni Dante, 1961), 33–41.

[18] Brigitte Christern-Briesenick et al., Repertorium der Christlich-Antiken Sarkophage, vol. 3 (Mainz am Rhein: Verlag Philipp von Zabern, 2003), 233–35.

[19] See Exodus 22:22; Deuteronomy 10:18; Leviticus 19:9–10, 23:22.

[20] Jerome’s letters are especially rich sources for examples of Christian women who can read and write. Evidence to this end is Jerome’s letter to Laeta on the education of her daughter. Jerome, Epistle 107. See Women and Society in Greek and Roman Egypt:

A Sourcebook, ed. Jane Rowlandson (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998),

no. 58, 77–78.

[21] Patricia Cox Miller, Women in Early Christianity (Washington, DC: The Catholic University of America Press, 2005), 49.

[22] Polycarp, To the Philippians 4.3, in Miller, Women in Early Christianity, 50.

[23] Didascalia apostolorum 3.6, 3.7, in Miller, Women in Early Christianity, 54.

[24] Carolinne White, ed. and trans., Lives of Roman Christian Women (London: Penguin Books, 2010), 19–48.

[25] The Life of Olympias, Deaconess (Selections) in Miller, Women in Early Christianity, 228–36.

[26] John Chrysostom, Homily XIV on Romans. From Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, First Series, vol. 11, ed. Philip Schaff (Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans, 1956), 451.

[27] Ambrose, Concerning Widows 1.1, from Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, Second Series, vol. 10, ed. Philip Schaff and Henry Wace (Buffalo, NY: Christian Literature, 1896), 391.

[28] Ambrose, Concerning Widows, 1.3.

[29] Ambrose, Concerning Widows, 3.14, from Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, 393.

[30] See Luke 8:1–3.

[31] Kate Cooper, Fall of the Roman Household (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 101–11.

[32] Cooper, Fall of the Roman Household, 93–143.

[33] For example, Luke 8:1–3; Luke 10:38; John 12:2; Acts 16:14–15. See Kate Cooper, Band of Angels: The Forgotten World of Early Christian Women (New York: The Overlook Press, 2013).

[34] Cooper, Fall of the Roman Household, 66.

[35] CIL 6.1755, trans. in Brian Croke and Jill Harries, Religious Conflict in Fourth-Century Rome: A Documentary Study (Sydney: Sydney University Press, 1982), 116, amended by Kate Cooper.

[36] Nicola Denzey, The Bone Gatherers: The Lost World of Early Christian Women (Boston: Beacon Press, 2007), 125–29.

[37] Catherine Taylor, “Allotting the Scarlet and the Purple: Late Antique Images of the Virgin Annunciate Spinning” (PhD diss., University of Manchester, 2012), 206–15.

[38] Judith Herrin, Margins and Metropolis: Authority across the Byzantine Empire (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2013), 270–73.

[39] Harvey, The New English Bible Companion to the New Testament, 436.

[40] Herrin, Margins and Metropolis, 273.

[41] Herrin, Margins and Metropolis, 276; see Exodus 22:22; Deuteronomy 10:18; Leviticus 19:9–10, 23:22.

[42] Carolyn Osiek and Margaret Y. MacDonald, A Woman’s Place (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2006), 12, 13; see 1 Timothy 5:10.

[43] Osiek and MacDonald, A Woman’s Place, 230.

[44] See Fitzmyer, The Acts of the Apostles, 445; Munck, The Acts of the Apostles, 89.

[45] Bonnie Bowman Thurston, The Widows: A Women’s Ministry in the Early Church (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1989), 32–35.

[46] Paul Zanker and Björn C. Ewald, Living with Myths: The Imagery of Roman Sarcophagi (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), x.

[47] Zanker, Living with Myths, 264.

[48] Zanker, Living with Myths, 265.

[49] Strelan, “Tabitha,” 84.