Masks of Oriental Gods: Symbolism of Kundalini Yoga

Joseph Campbell

Joseph Campbell, “Masks of Oriental Gods: Symbolism of Kundalini Yoga,” in Literature of Belief: Sacred Scripture and Religious Experience, ed. Neal E. Lambert (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1981), 109–38.

Professor emeritus of literature at Sarah Lawrence College in New York, Joseph Campbell enjoyed a worldwide reputation as an authority in the field of comparative mythology. He has written and edited some twenty-five books on comparative religions and mythology including his influential interpretation of the hero myth, The Hero with a Thousand Faces, and his important four-volume study of world myths, The Masks of God. He is currently writing and compiling a two-volume historical atlas of world mythology.

In 1974, Professor Campbell published The Mythic Image, a lavishly illustrated presentation of some major visual motifs in comparative mythologies. His paper on Kundalini yoga is taken from this work. Because Professor Campbell’s presentation at the symposium was a slide lecture, and hence difficult to reproduce, the Religious Studies Center secured permission from Princeton University Press to reproduce the relevant portions of The Mythic Image, along with a few of its superb illustrations. This book was the hundredth and final title in the Bollingen Foundation’s “Bollingen” series, a landmark publishing effort with which Professor Campbell has been associated since its inception.

In his keynote presentation at the symposium, Professor Campbell laid some essential groundwork by wryly defining mythology as “other people’s religion” and then by giving a working definition of yoga as “the intentional stopping of the spontaneous activity of the mindstuff.” On this foundation he built a literate and visually attractive edifice which he invented his audience to enter. What he structured was a comprehensive and captivating introduction into one of the most ancient of spiritual disciplines—Kundalini yoga.

Our subject, the literature of belief, is of profound historical importance, since in its various forms it has played the decisive role in both the harmonization and the discord of religions. A distinction is to be made in the first place between belief in the literal nature of a revelation and in the experience of its symbolic reference. One of the great problems in dealing with religious imagery—in dealing with poetic imagery even—is to go past and through the historically conditioned image to its transcendental reference without losing the image and without losing appreciation for its historically conditioned special quality and sense.

I have a favorite definition of mythology: mythology is other people’s religion. We have a way of saying, “You worship God in your way, I worship God in his.” And my favorite definition of religion is: misunderstood mythology. The misunderstanding consists typically in interpreting spiritual symbols as though they referred finally to historical events and characters. The historical character or event is but the vehicle of a spiritual message, and if you stay with the event, you lose the message. Anything that can be named, anything that can be envisioned, is but a reference to what is absolutely transcendent, and that which absolutely transcends all reference, all naming, and imaging, is the essence not only of the universal mystery but also of your own being; so that that which transcends all is imminent within all and is not really named in any naming.

One of the very great systems for interpreting the stages in amplification of our understanding and experience of the reference of these signs and symbols is the Indian system that I am to talk about today, the Kundalini yoga. I do not practice yoga myself. I am a scholar; therefore I can talk about it. The great Indian saint of the last century, Ramakrishna, in Calcutta, was a virtuoso in the experience of the Kundalini transformations. When his disciples would ask him, “Oh Master, how is it when the Kundalini energy is of the first center? the second center? the third center? the fourth center?” he would tell them. But when he went above the fourth, he passed out. My advantage in being a scholar is that I am not going to pass out and shall take you right up the line of the Kundalini centers.

It is my belief that this concept of the Kundalini yoga is India’s greatest gift to us. I find it useful in relationship to symbolic and religious understanding and studies everywhere and anywhere; it relates to all the mythologies of the world. India’s long season of inward turning and experience has given a kind of power of interpretation to the Indian religious traditions that is unmatched anywhere else.

Now yoga is defined in the standard textbook of yoga, The Yoga Sutras of Patanjali, in the following way: “Yoga is the intentional stopping of the spontaneous activity of the mindstuff.” The notion is that there is within the gray matter—the physical matter or gross substance of the brain—a subtle substance that changes form very rapidly. This subtle matter takes the form of what is seen, heard, or felt, and so on. That is how what is outside is translated into an inside experience. Look around very fast and you will see how quickly this subtle matter changes form. The problem is that it never stops changing. It continues to move. Try to hold in your mind for a couple of seconds one idea or one image—of someone you love, let us say. You will find within a few seconds, if you are honest with yourself, that you are having associated thoughts and have not become fixed on a still point.

The first function, then, the first goal and the ultimate goal of yoga is to make the mind stand still. Now you may ask yourself, “Why should we want to make the mind stand still?” The answer is given in the way of an analogy. The analogy is of the mind as the surface of a pond that is rippled by a wind. All the images on that pond are changing form. They are flashing, they are coming, they are going, and they are broken. We identify ourselves with one of those flashing images on the surface of our pond, namely, the image that we call ourselves. It comes, it goes. You are born, you die. “Oh my, here I come, there I go!” Make the pond stand still. Turn to the first verse in the book of Genesis which records that the spirit (the wind) of God was brooding or blowing over the waters. That is the wind that brings on the creation of the world. If you can make the wind stand still, the pond then becomes a perfect mirror. In it is then seen one fixed image, the image of images, the image that was broken and changing all over the place. Also the waters have cleared and you can see down to the bottom, into the inwardness of your own being. That is the image that is ultimately you, not the you that was born, not the you that will die, not the you that your friends all love and that you take such nice care of. This familiar you is but the you in the flashing reflection of the mind. The ultimate you is one with all the other passing images, because we are all broken images of that which is seen when the mind stands still. These are now understood to be simply flashing, momentary references to that one, which is finally no image.

Some become so entranced in the still-standing mind that they stay there; and then, as they say in India, the body drops off. But that is only half the story. The other half is to come back, to open your eyes. Let the wind blow and see and recognize and take joy in the ever-changing forms.

And that is the wonderful ambiguity that is involved in the literature of belief—not to lose the joy of participation and appreciation for the image that is your own image, your own religion’s way of imaging this universal model, while at the same time pointing past it. What you will find is that you will not lose your religion in that context; it receives a new dimension of power and wonder. One can then remain in the world with the wisdom of the absolute and yet with joyful participation in the sorrows of the world. All life is sorrowful. Learn how to participate in this sorrow with joy.

And so now we come to the specifics of the Kundalini.*

It was during the centuries of the burgeoning of the various pagan, Jewish, and Christian Gnostic sects of Rome’s Near Eastern provinces (the first four centuries of the Christian Era) that in Hindu and Buddhist India the first signs of what is known as Tantric practice appeared. The backgrounds of both movements, the Gnostic and the Tantric, are obscure, as are their connections with each other. Rome at the time was in direct commerce with India. Buddhist monks were teaching in Alexandria, Christian missionaries in Kerala. The halo (a Persian, Zoroastrian motif) had appeared abruptly in the Christian art of the time as well as in the Buddhist art of India and China; and in contemporary writings evidences abound of what must have been a very lively two-way traffic.

The elder Pliny (A.D. 23–79) wrote, for example:

In no year does India drain us of less than 550,000,000 sesterces, giving back her own wares, which are sold among us at fully 100 times their first cost. . . . Our ladies glory in having pearls suspended from their fingers, or two or three of them dangling from their ears, delighted even with the rattling of the pearls as they knock against each other; and now, at the present day, even the poorer classes are affecting them, since people are in the habit of saying that “a pearl worn by a woman in public is as good as a lictor walking before her.” Nay, even more than this, they put them on their feet, and that not only on the laces of their sandals but all over the shoes; it is not enough to wear pearls, but they must tread upon them, and walk with them under foot as well.” [1]

Mircea Eliade, in his masterful Yoga: Immortality and Freedom, has suggested something of the obscurity and complexity of the problem of the origins and development of Tantric thought:

It is not easy to define tantrism. Among the many meanings of the word tantra (root tan, “extend,” “continue,” “multiply”), one concerns us particularly—that of “succession,” “unfolding,” “continuous process.” Tantra would be “what extends knowledge” (tanyate, vistaryate, jnanam anena iti tantram). In this acceptation, the term was already applied to certain philosophical systems (Nyaya-tantresu, etc.). We do not know why and under what circumstances it came to designate a great philosophical and religious movement, which, appearing as early as the fourth century of our era, assumed ine form of a pan-Indian vogue from the sixth century onward. For it was really a vogue; quite suddenly, tantrism becomes immensely popular, not only among the active practitioners of the religious life (ascetics, yogins, etc.), and its prestige also reaches the “popular” strata. In a comparatively short time, Indian philosophy, mysticism, ritual, ethics, iconography, and even literature are influenced by tantrism. It is a pan-Indian movement, for it is assimilated by all the great Indian religions and by all the “sectarian” schools. There is a Buddhist tantrism and a Hindu tantrism, both of considerable proportions. But Jainism too accepts certain tantric methods (never those of the “left hand”), and strong tantric influences can be seen in Kashmirian Shivaism, in the great Pancaratra movement (c. 550), in the Bhagavata Purana (c. 600), and in other Vishnuist devotional trends. [2]

It would be ridiculous to pretend that in a few pages, or even a considerable tome, anything more than a suggestion of the jewel tree—or rather, jewel jungle—of this truly astounding body of psychologized physiological and mythological lore might be offered. Even a glimpse will suffice to make the point, however, that there is evidence in this body of material of a highly developed psychological science: one, moreover, that has shaped and informed every significant development of Oriental doctrine—whether in India, Tibet, China, Korea, Japan, or Southeast Asia—from the first centuries of the Christian Era. And since there is evidence, furthermore, already in the earliest Upanishads—the Brihadaranyaka and Chhandogya—that something like an elementary foreview of the Tantric movement had been known to India long before the general vogue, we shall have to take into account the possibility that its sudden popularity, to which Professor Eliade alludes, represents not so much a novelty as a resurgence in freshly stated terms of principles long familiar to the pre-Aryan—or even, possibly, pre-Dravidian—populations of the timeless East. [3]

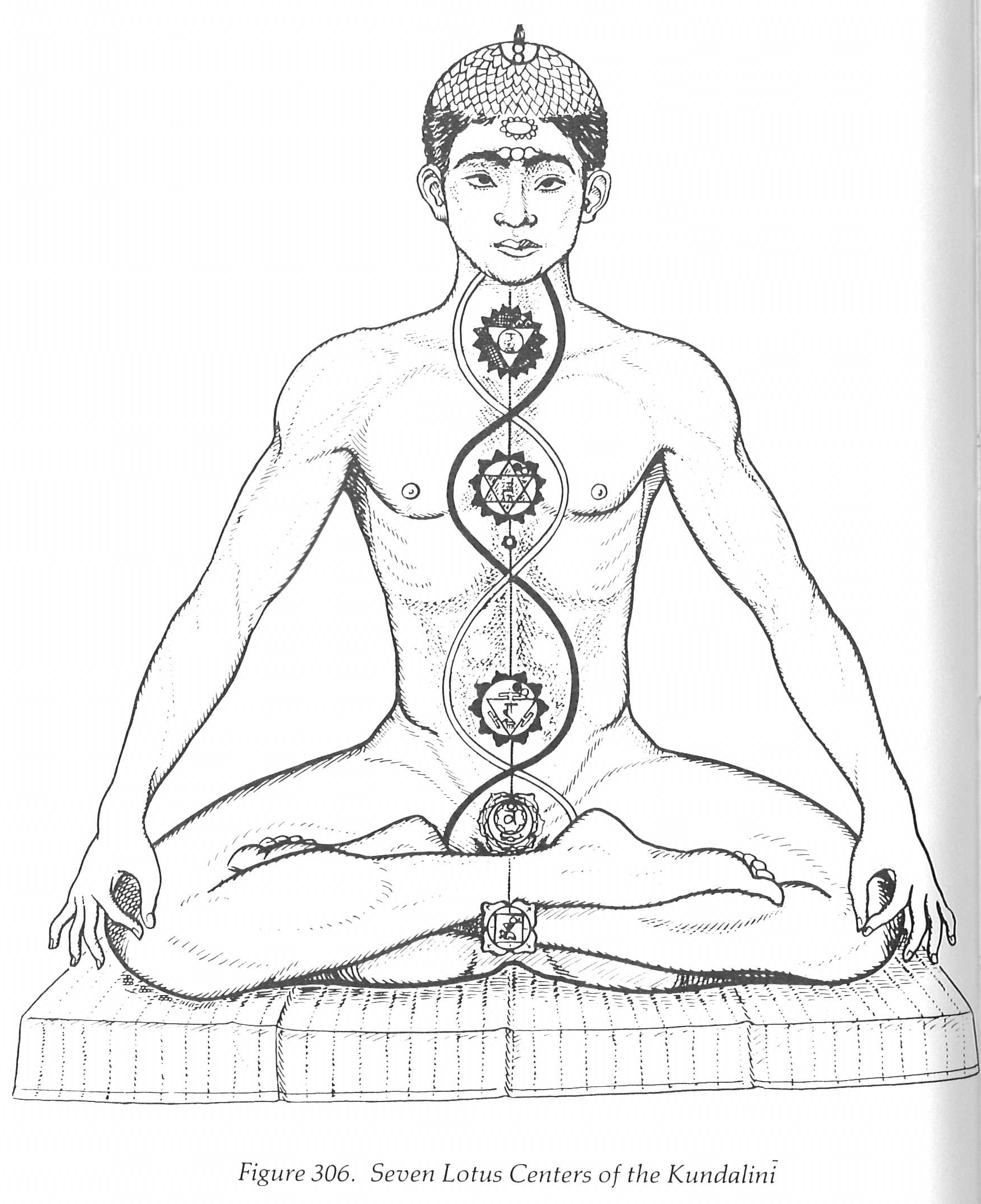

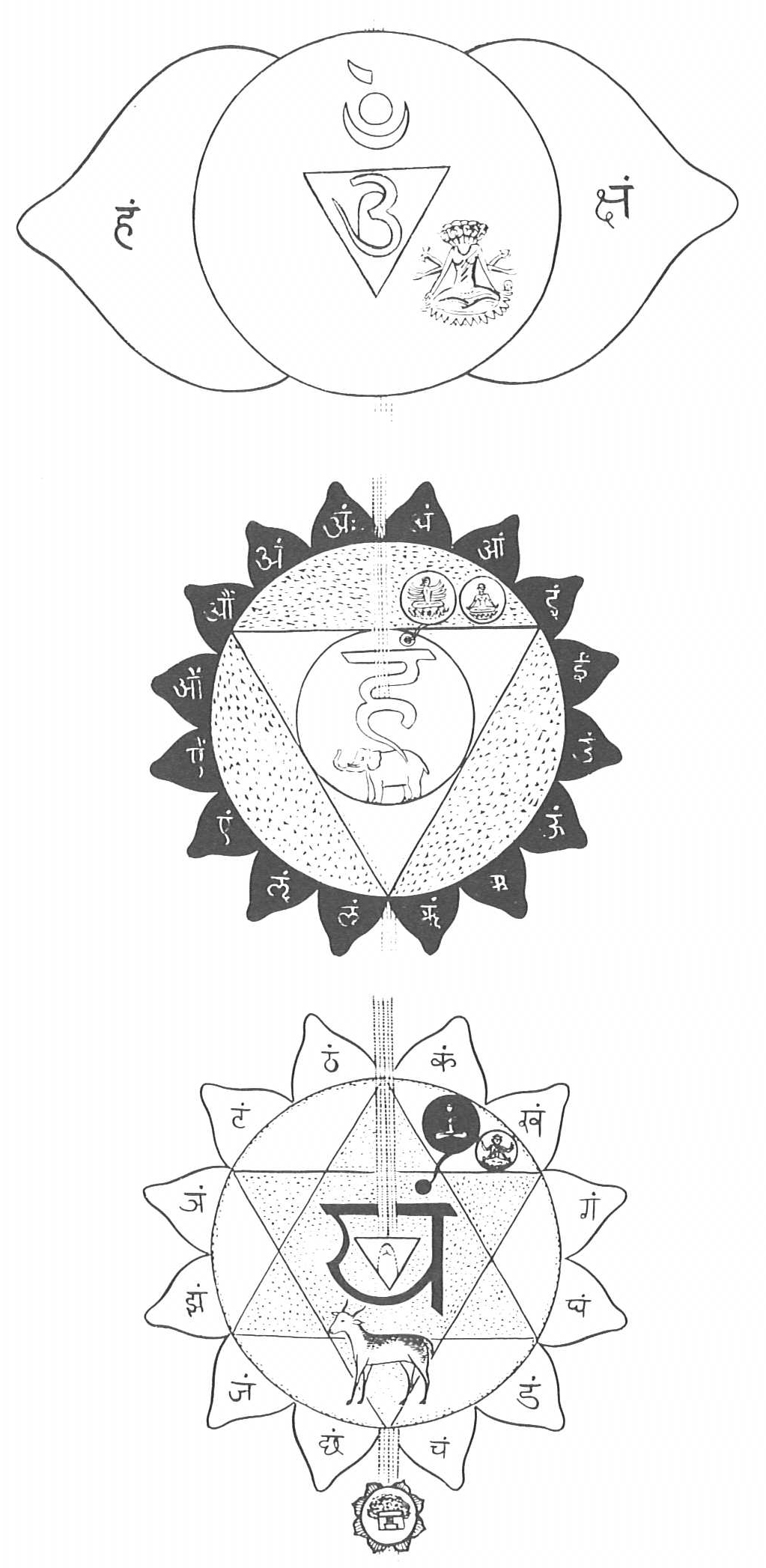

The essential alphabet of all Tantric lore is to be learned from the doctrine of the seven “circles” (chakras) or “lotuses” (padmas) of the kundalini system of yoga. (See fig. 306.) The long terminal i added to the Sanskrit adjective kundalin, meaning “circular, spiral, coiling, winding,” makes a feminine noun signifying “snake,” the reference in the present context being to the figure of a coiled female serpent—a serpent goddess not of “gross” but of “subtle” substance—which is to be thought of as residing in a torpid, slumbering state in a subtle center, the first of the seven, near the base of the spine: the aim of the yoga then being to rouse this serpent, lift her head, and bring her up a subtle nerve or channel of the spine to the so-called “thousandpetalled lotus” (sahasrara) at the crown of the head. This axial stem or channel, which is named sushumna (“rich in happiness, highly blessed”), is flanked and crossed by two others: a white, known as ida (meaning “refreshment, libation; stream or flow of praise and worship”), winding upward from the left testicle to right nostril and associated with the cool, ambrosial, “lunar” energies of the psyche; and a red, called pingala (“of a sunlike, tawny hue”), extending from the right testicle to left nostril, whose energy is “solar, fiery,” and, like the solar heat of the tropics, desiccating and destructive. [4] The first task of the yogi is to bring the energies of these contrary powers together at the base of his sushumna and then to carry them up the central stem, along with the uncoiling serpent queen. She, rising from the lowest to the highest lotus center, will pass through and wake the five between, and with each waking the psychology and personality of the practitioner will be altogether and fundamentally transformed.

Now there was in the last century a great Indian saint, Ramakrishna (1836–86), who in the practices of this yoga was a veritable virtuoso. “There are,” he once told his devotees, “five kinds of samadhi”; five kinds, that is to say, of spiritual rapture.

In these samadhis one feels the sensation of the Spiritual Current to be like the movement of an ant, a fish, a monkey, a bird, or a serpent.

Sometimes the Spiritual Current rises through the spine, crawling like an ant. Sometimes, in samadhi, the soul swims joyfully in the ocean of divine ecstasy, like a fish. Sometimes, when I lie down on my side, I feel the Spiritual Current pushing me like a monkey and playing with me joyfully. I remain still. That Current, like a monkey, suddenly with one jump reaches the Sahasrara. That is why you see me jump up with a start. Sometimes, again, the Spiritual Current rises like a bird hopping from one branch to another. The place where it rests feels like fire. . . . Sometimes the Spiritual Current moves up like a snake. Going in a zigzag way, at last it reaches the head and I go into samadhi. A man’s spiritual consciousness is not awakened unless his Kundalini is aroused.

He goes on to describe a certain experience:

Just before my attaining this state of mind, it had been revealed to me how the Kundalini is aroused, how the lotuses of the different centers blossom forth, and how all this culminates in samadhi. This is a very secret experience. I saw a boy twenty-two or twenty-three years old, exactly resembling me, enter the Sushumna nerve and commune with the lotuses, touching them with his tongue. He began with the first center at the anus, and passed through the centers at the sexual organ, navel, and so on. The different lotuses of those centers—fourpetalled, six-petalled, ten-petalled, and so forth—had been drooping. At his touch they stood erect.

When he reached the heart—I distinctly remember it—and communed with the lotus there, touching it with his tongue, the twelve-petalled lotus, which was hanging head down, stood erect and opened its petals. Then he came to the sixteen-petalled lotus in the throat and the two-petalled lotus in the forehead. And last of all, the thousand-petalled lotus in the head blossomed. Since then I have been in this state. [5]

The earliest serious studies in English of the principles of Tantra appeared during the first quarter of this century in the publications of Sir John Woodroffe (1865–1936), Supreme Court Judge at Calcutta, three of whose imposing volumes are indispensable to any Western reader seeking more than a passing knowledge of this learning: Principles of Tantra (Madras, 1914), Shakti and Shakta (Madras, 1928), and The Serpent Power (Madras, 3rd rev. ed., 1931). Add to these the more recent work by Dr. Shashibhusan Dasgupta, Obscure Religious Cults as Background of Bengali Literature (Calcutta, 1946), and the compendious handbook of Professor Eliade, already mentioned, and the patient student will be enabled to open to himself many hidden approaches to the interpretation of symbols and their relevance to his own interior life.

At the outset, however, two warnings are generally given: first, not to attempt to engage alone in the indicated exercises, since they activate unconscious centers, and improperly undertaken may lead to a psychosis; and second, not to overinterpret whatever signs of early success one may enjoy in the course of practice. Sir John Woodroffe explains:

There is one simple test whether the Shakti is actually aroused. When she is aroused intense heat is felt at that spot, but when she leaves a particular center the part so left becomes as cold and apparently lifeless as a corpse. The progress upwards may thus be externally verified by others. When the Shakti (Power) has reached the upper brain (Sahasrara) the whole body is cold and corpselike; except the top of the skull, where some warmth is felt, this being the place where the static and kinetic aspects of Consciousness unite. [6]

And so, to begin, then, at the beginning.

One is to sit in a posture of perfectly balanced repose, and in this so-called “lotus posture” to begin regulating the breath. The psychological theory underlying this primary exercise is that the mind or “mind power” (manas) and breathing or “breath power” (prana) interlock and are in fact the same. When one becomes angry, the breathing changes; also, when one is moved with erotic desire. In repose, it steadies down. Accordingly, control of the breath controls feeling and emotion, and can be made to serve as a mind-regulating factor. That is why in all serious Oriental mind-transforming enterprises the fundamental discipline is pranayama, “control of the breath.” Steadying the breath one correspondingly steadies the mind, and the resultant aeration of the blood, furthermore, sets going in the body certain chemical processes that produce predictable effects.

Now this breathing will seem a little strange. One is to inhale through the right nostril, imagining the air as pouring down the white or “lunar” spinal course, ida, cleaning it out, as it were. One is to hold the breath a certain number of counts and to breathe out, then, with the air coming up through pingala, the tawny “solar” nerve. Next: in through the left, and after a hold, out through the right; and so on, strictly according to counts, the mind in this way being steadied down, the whole nervous system clarified; until presently, one fine day, the serpent goddess will be felt to stir.

I have been told that certain yogis, on becoming aware of this movement, press their hands to the ground and, elevating themselves a little from their lotus seats, bang down, to give the coiled-up one a physical jolt to rouse her. The waking and elevation are described in the texts in terms altogether physical. The references are to that “subtle” physical matter already mentioned, however, not the gross matter to which the observations of our scientists are directed. As Alain Danièlou has remarked in his compact little volume, Yoga: The Method of Reintegration: “The Hindu will therefore speak indifferently of men or of subtle beings, he intermingles the geography of celestial worlds with that of terrestrial continents, and in this he sees no discontinuity but, on the contrary, a perfect coherence; for, to him, these worlds meet at many common points, and the passage from one to the other is easy for those who have the key.” [7] Much the same could be said of almost any of the mythologically structured, protoscientific traditions of the ancient past.

So now we have got the serpent started: let us follow her up the spinal staff, which in this yoga is regarded as the microcosmic counterpart of the macrocosmic universal axis, its lotus stages being thus equivalent to the platforms of the many-storied ziggurats, and its summit to the lofty marriage chamber of the lunar and solar lights.

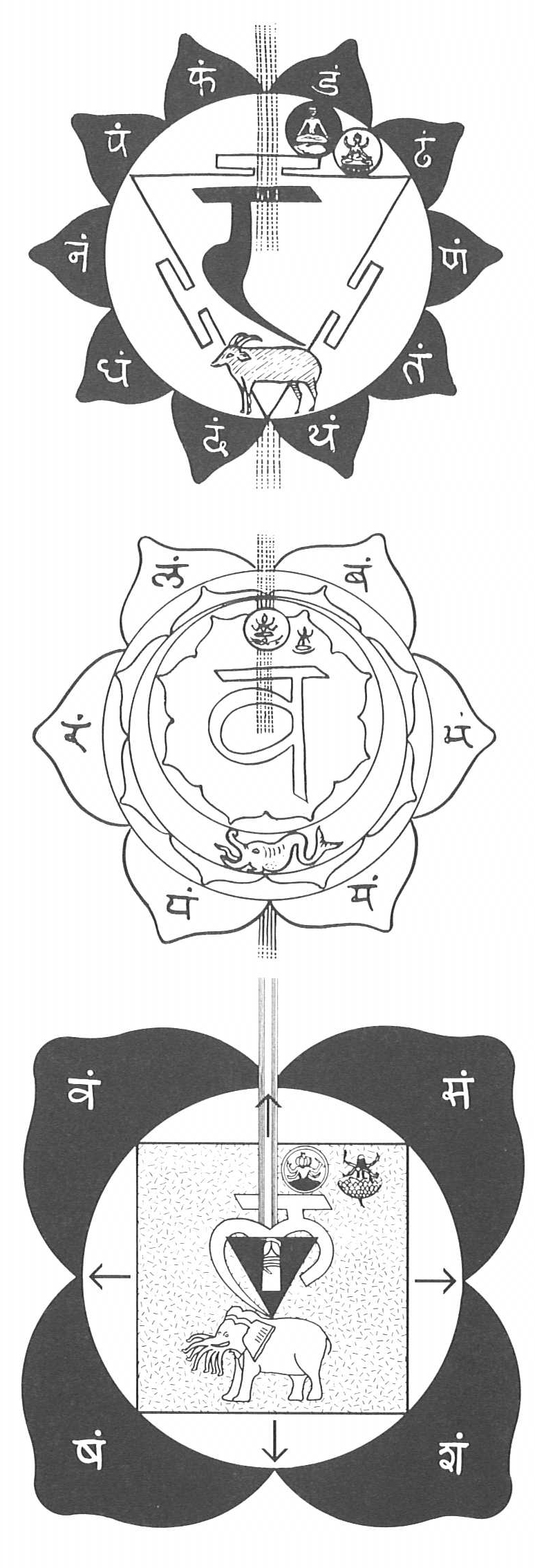

The lotus at the base of the sushumna, called the “Root Support” (Muladhara), is described as crimson in hue and having four petals, on each of which a Sanskrit syllable is inscribed (reading clockwise, from the upper right: vam, sam, sham, and sam). (See fig. 312.) These are to be understood as sound counterparts of the aspects of spiritual energy operative on this plane. In the white center is a yellow square symbolic of the element earth, wherein a white elephant stands waving seven trunks. This animal is Airavata, the mythic vehicle of Indra, the Vedic king of the gods, here supporting on its back the sign of the syllable lam, “which,” Woodroffe writes, “is said to be the expression in gross sound of the subtle sound made by the vibration of forces of this center.” [8] The elephant, he continues, is symbolic of the strength, firmness, and solidity of earth; but it is also a cloud condemned to walk upon the earth, so that if it could be released from this condition it would rise. The supervising deity made visible in this lowest center is the world creator Brahma, whose shakti, the goddess Savitri, is a personification of solar light. On the elephant’s back is a downwardpointing triangle symbolic of the womb (yoni) of the goddess mother of the universe, and within this “city of three sides,” this “figure of desire,” is seen the first or basal divine phallus (lingam) of the universal masculine principle, Shiva. The white serpent-goddess Kundalini, “fine as the fiber of a lotus-stalk,” is coiled three and a half times around this lingam, asleep, and covering with her head its Brahma door. [9]

Now to be exact, the precise locus of this center at the base of the human body is midway between the anus and the genitals, and the character of the spiritual energy at that point is of the lowest intensity. The world view is of uninspired materialism, governed by “hard facts”; the art, sentimental naturalism; and the psychology, adequately described in behavioristic terms, is reactive, not active. There is on this plane no zeal for life, no explicit impulse to expand. There is simply a lethargic avidity in hanging on to existence; and it is this grim grip that must finally be broken, so that the spirit may be quit of its dull zeal simply to be.

One may think of the Kundalini on this level as comparable to a dragon; for dragons, we are told by those who know, have a propensity to hoard and guard things; and their favorite things to hoard and guard are jewels and beautiful young girls. They are unable to make use of either, but just hang on, and so the values in their treasury are unrealized, lost to themselves and to the world. On this level, the serpent-queen Kundalini is held captive by her own dragon-lethargy. She neither knows nor can communicate to the life that she controls any joy, yet will not relax her hold and let go. Her key motto is a stubborn “Here I am, and here I stay.”

The first task of the yogi, then, must be to break at this level the cold dragon grip of his own spiritual lethargy and release the jewel-maid, his own shakti, for ascent to those higher spheres where she will become his spiritual teacher and guide to the bliss of an immortal life beyond sleep.

The second lotus of the series, called Svadhisthana, “Her Special Abode,” is at the level of the genitals. (See fig. 313.) It is a vermilion lotus of six petals, bearing the syllables bam, bham, mam, yam, ram, and lam. Water being the element of this center, its inner field is the shape of a crescent moon, within which a mythological water monster known as a makara is to be seen, supporting the sign of the water syllable vam. This is the seed sound of the Vedic god Varuna, lord of the rhythmic order of the universe. The presiding Hindu (as distinct from early Vedic) deity here is Vishnu in the pride of early youth, clothed in yellow and holding a noose in his hand. Beside him sits a wrathful form of his shakti, Rakini by name, of the color of a blue lotus, bearing in her four hands a lotus, a drum, a sharp battle ax, and a spear, her teeth showing fiercely, her three eyes blazing red, and her mind exalted from the drinking of ambrosia. [10]

Chakra 1: Muladahara (bottom);

Chakra 1: Muladahara (bottom);

Chakra 2: Svadisthana (center); Chakra 3: Manipura (top).

When the Kundalini is active at this level, the whole aim of life is in sex. Not only is every thought and act sexually motivated, either as a means toward sexual ends or as a compensating sublimation of frustrated sexual zeal, but everything seen and heard is interpreted compulsively, both consciously and unconsciously, as symbolic of sexual themes. Psychic energy, that is to say, has the character here of the Freudian libido. Myths, deities, and religious rites are understood and experienced in sexual terms.

Now of course there are in fact a great many myths and rites directly addressed to the concerns of this important center of life—fertility rites, marriage rites, orgiastic festivals, and so on—and a Freudian approach to the reading and explanation of these may not be altogether inappropriate. However, according to Tantric learning, even though the obsession of the life-energies functioning from this psychological center is sexual, sexuality is not the primal ground, end, or even sole motivation of life. Any fixation at this level is consequently pathological. Everything then reminds the blocked and tortured victim of sex. But if it also reminds his doctor of sex, what is the likelihood of a cure? The method of the Kundalini is rather to recognize affirmatively the force and importance of this center and let the energies pass on through it, to become naturally transformed to other aims at the higher centers of the “rich in happiness” sushumna.

Chakra three, at the level of the navel, is called Manipura, “City of the Shining Jewel,” for its fiery heat and light. (See fig. 314.) Here the energy turns to violence and its aim is to consume, to master, to turn the world into oneself and one’s own. The appropriate Occidental psychology would be the Adlerian of the “will to power”; for now even sex becomes an occasion, not of erotic experience, but of achievement, conquest, selfreassurance, and frequently, also, revenge. The lotus has ten petals, dark as thunderheads heavy laden, bearing the seed syllables dam, dham, nam, tarn, tham, dam, dham, nam, pam, and pham. Its central triangle, in a white field, is the sign of the element fire, shining like the rising sun, with swastika marks on its sides. The ram, its symbolic animal, is the vehicle of Agni, Vedic god of the sacrificial fire, bearing on its back the syllable ram, which is the seed syllable or sound form of this god and his fiery element. The presiding Hindu (as distinct from Vedic) deity is Shiva in his terrible guise as an ascetic smeared with the ashes of funeral pyres, seated on his white bull Nandi. And at his side is his goddess shakti, enthroned on a ruby lotus in her hideous character of Lakini. Lakini is blue, with three faces, three eyes to each; fierce of aspect, with protruding teeth. She is fond of meat: her breast is smeared with grease and blood that have dripped from her ravenous jaws; yet she is radiant, elegant with ornaments, and exalted from the drinking of ambrosia. She is the goddess who presides over all rites of human sacrifice and over the battlefields of mankind, terrible as death to behold, though to her devotees gracious, beautiful, and sweet as life.

Now all three of these lower chakras are of the modes of man’s living in the world in his naive state, outward turned: the modes of the lovers, the fighters, the builders, the accomplishers. Joys and sorrows on these levels are functions of achievements in the world “out there”: what people think of one, what has been gained, what lost. And throughout the history of our species, people functioning only on these levels (who, of course, have been in the majority) have had to be tamed and brought to heel through the inculcation of a controlling sense of social duty and shared social values, enforced not only by secular authority but also by all those grandiose myths of an unchallengeable divine authority to which every social order—each in its own way—has had to lay claim. Wherever motivations of these kinds are not checked effectively, men, as the old texts say, “become wolves unto men.”

However, it is obvious that a religion operating only on these levels, having little or nothing to do with the fostering of inward, mystical realizations, would hardly merit the name of religion at all. It would be little more than an adjunct to police authority, offering in addition to ethical rules and advice intangible consolations for life’s losses and a promise of future rewards for social duties fulfilled. Hence, to interpret the imagery, powers, and values of the higher chakras in terms of the values of these lower systems is to mistranslate them miserably, and to lose contact in oneself, thereby, with the whole history and heritage of mankind’s life in the spirit.

And so we ascend to chakra four, at the level of the heart, where what Dante called La Vita Nuova, “The New Life,” begins. And the name of this center is Anahata, “Not Struck”; for it is the place where the sound is heard “that is not made by any two things striking together.” (See fig. 332.)

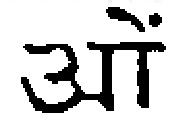

Every sound normally heard is of two things striking together; that of the voice, for example, being the sound of the breath striking our vocal cords. The only sound not so made is that of the creative energy of the universe, the hum, so to speak, of the void, which is antecedent to things, and of which things are precipitations. This, they say, is heard as from within, within oneself and simultaneously within space. It is the sound beyond silence, heard as om (very deeply intoned, I am told, somewhere about C below low C). “The word om,” said Ramakrishna to his friends, “is Brahman. Following the trail of om, one attains to Brahman.” [11]

In the Sanskrit Devanagari script om is written either as or as , and in the posture of the dancing Shiva image the pose of the head, hands, and lifted foot suggests the outline of this sign—which makes the point that in the appearance of this god the sound resounds of the wonder of existence. Om is interpreted as the seed sound, the energy sound, the shakti, of all being, and in that sense analyzed in the following way by the seers and teachers of the Upanishads.

Firstly, since the vowel o in Sanskrit is regarded as a fusion of a and u, the syllable om can be written also as aum——and in that augmented form is called the syllable of four elements; namely, a, u, m, and the silence that is before, after, and around it, out of which it rises and back into which it falls—as the universe, out of and back into the void.

The a is announced with open throat; the u carries the sound-mass forward; and the m, then, somewhat nasalized, brings all to a close at the lips. So pronounced, the utterance will have filled the whole mouth with sound and so have contained (as they say) all the vowels. Moreover, since consonants are regarded in this thinking as interruptions of vowel sounds, the seeds of all words will have been contained in this enunciation of aum, and in these, the seed sounds of all things. Thus words, they say, are but fragments or particles of aum, as all forms are particles of that one Form of forms that is beheld when the rippling surface of the mind is stilled in yoga. And accordingly, aum is the one sound spelled in all possible inflections on the petals of the Kundalini series.

Allegorically, the initial a of aum is said to represent the field and state of Waking Consciousness, where objects are of “gross matter” (sthula) and are separate both from each other and from the consciousness beholding them. On this plane of experience, I am not you, nor is this that; A is not not-A; cause and effect, God and his world, are not the same, and all mystical statements are absurd. Moreover, the gross objects of this daylight sphere, to be seen, must be illuminated from without. They are not self-luminous, except, of course, in the instances of fire, lightning, stars, and the sun, which suggest gates to another order of existence. Anything perceived by the waking senses, furthermore, must already have come into being, and so is already a thing of the past. Science, the wisdom of the mind awake, and of “hard facts,” can consequently be a knowledge only of what has already become, or of what in the future is to repeat and continue the past. The unpredictably creative, immediate present is inaccessible to its light.

And so we come to the letter u, which is said to represent the field and state of Dream Consciousness, where, although subject and object may appear to be different and separate from each other, they are actually one and the same. A dreamer is surprised, even threatened, by his dream, not knowing what it means; yet even while dreaming he is himself inventing it; so that two aspects of the one subject are here playing hide-and-seek: one in creative action, the other in half-ignorance. And the objects of this world of dream, furthermore, being of “subtle matter” (sukshma), shine of themselves, rapidly changing shape, and therefore are of the order of fire and the radiant nature of gods. In fact, the Indo-European verbal root div, from which the Latin divus and deus, Greek Zeus, and Old Irish dia as well as Sanskrit deva (all meaning “deity”) derive, signifies “to shine”; for the gods, like the figures of dream, shine of themselves. They are the macrocosmic counterparts of the images of dream, personifications of the same powers of nature that are manifest in dreams; so that on this plane the two worlds of the microcosm and macrocosm, interior and exterior, individual and collective, particular and general, are one. The individual dream opens to the universal myth, and gods in vision descend to the dreamer as returning aspects of himself.

Mythologies are in fact the public dreams that move and shape societies; and conversely, one’s own dreams are the little myths of the private gods, antigods, and guardian powers that are moving and shaping oneself: revelations of the actual fears, desires, aims, and values by which one’s life is subliminally ordered. On the level, therefore, of Dream Consciousness one is at the quick, the immediate initiating creative now, of one’s life, experiencing those activating forces that in due time will bring to pass unpredicted events on the plane of Waking Consciousness and be there observed and experienced as “facts.”

So then, if a is of Waking Consciousness, gross objects, and what has become (the past), and u of Dream Consciousness, subtle objects, and what is becoming (the present), m is of Deep Dreamless Sleep, where (as we say) we have “lost” consciousness, and the mind (as described in the Indian texts) is “an undifferentiated mass or continuum of consciousness unqualified,” lost in darkness. That which when awake is conscious only of what has become and in dream of what is becoming, is in Deep Dreamless Sleep dissociated from all commitments whatsoever, and so is returned to that primal, undifferentiated, and unspecified state of latency, chaos, or potentiality from which all that will ever be must in time arise. But alas! The mind that there contains all is lost in sleep. As the Chhandogya Upanishad describes it: “Just as those who do not know the spot might pass over a hidden treasure of gold again and again but not find it, even so do all creatures here go to that Brahma-world, day after day, in deep sleep, and not find it.” [12]

So also in C. G. Jung’s account: “The deeper ‘layers’ of the psyche lose their individual uniqueness as they retreat farther and farther into darkness. ‘Lower down,’ that is to say as they approach the autonomous functional systems, they become increasingly collective until they are universalized and extinguished in the body’s materiality, i.e., in chemical substances. The body’s carbon is simply carbon. Hence, ‘at bottom’ the psyche is simply ‘world.’” [13]

Briefly stated, then: the goal of every yoga is to go into that zone awake; to sink to where there is no longer any resting on this object or on that, whether of the waking world or of dream, but there is met the innate light that is called, in Buddhist lore, the Mother Light. And this then, this inconceivable sphere of undifferentiated consciousness, experienced not as extinction but as light unmitigated, is the reference of the fourth element of AUM: the Silence that is before, after, within, and around the sounding syllable. It is silent because words, which do not reach it, refer only to the names, forms, and relationships of objects either of the daylight world or of dream.

The sound aum, then, “not made by any two things striking together,” and floating as it were in a setting of silence, is the seed sound of creation, heard when the rising Kundalini reaches the level of the heart. (See figure 332.) For there, as they say, the Great Self abides and portals open to the void. The lotus of twelve red petals, marked with the syllables kam, kham, gam, gham, ngam, cham, chham, jam, jham, nyam, tarn, and tham, is of the element air. In its bright red center is an interlocking double triangle, the color of smoke, signifying “juncture” and containing its seed syllable yam displayed above an antelope, which is the beast, swift as wind, of the Vedic wind-god Vayu. The female triangle within this letter holds a lingam like shining gold, and the patron Hindu deity is Shiva in a gentle, boon-bestowing aspect. His shakti, known here as Kakini, lifts a noose and a skull in two hands, while exhibiting with her other two the “boon-bestowing” and “fear-dispelling” gestures.

Just below this lotus of the heart there is pictured a lesser, uninscribed lotus, at about the level of the solar plexus, supporting on a jeweled altar an image of the Wish-Fulfilling Tree. For it is here that the first intimations are heard of the sound aum in the Silence, and that sound itself is the Wish-Fulfilling Tree. Once heard, it can be rediscovered everywhere and no longer do we have to seek our good. It is here—within—and through all things, all space. We can now give up our struggle for achievement, for love and power and the good, and may rest in peace.

Or so, at first, it will seem.

However, there is a new zeal, a new frenzy, now stirring in the blood. For, as Dante states at the opening of La Vita Nuova, describing the moment when he first beheld Beatrice:

At that moment, I say truly, the spirit of life, which dwells in the most secret chamber of the heart, began to tremble with such violence that it appeared fearfully in the least pulses, and, trembling, said these words: “Behold a god stronger than I, who coming shall rule over me.”

At that instant the spirit of the soul, which dwells in the high chamber to which all the spirits of the senses carry their perceptions, began to marvel greatly, and, speaking especially to the spirit of the sight, said these words: “Now has appeared your bliss.”

At that instant the natural spirit, which dwells in that part where our nourishment is supplied, began to weep, and, weeping, said these words: “Woe is me, wretched! because often from this time forth shall I be hindered.” [14]

Once the great mystery-sound has been heard, the whole desire of the heart will be to learn to know it more fully, to hear it, not through things and within during certain fortunate moments only, but immediately and forever. And the attainment of this end will be the project of the next chakra, the fifth, which is at the level of the larynx and is called Vishuddha, “Purified.” (See fig. 333.) “When the Kundalini reaches this plane,” said Ramakrishna, “the devotee longs to talk and to hear only of God.” [15]

Chakra 4: Anahata (bottom);

Chakra 4: Anahata (bottom);

Chakra 5: Vishudda (center); Chakra 6: Ajna (top).

The lotus has sixteen petals of a smoky purple hue, on each of which is engraved one of the sixteen Sanskrit vowels, namely, am, am, im, im, um, um, rm, rm, Irm, Irm, em, aim, om, aum, am, and ah. In the middle of its pure white central triangle is a white disk, the full moon, wherein the syllable ham, of the element space or ether, rests on the back of a pure white elephant. The patron of this center is Shiva in his hermaphroditic form known as Ardhanareshvara, “Half-Woman Lord,” five-faced, clothed in a tiger’s skin, and with ten radiant arms. One hand makes a “fear-dispelling” gesture and the rest are exhibiting his trident, battle-ax, sword, and thunderbolt, a fire, a snake-ring, a bell, a goad, and a noose, while beside him his goddess, here called Sakini, holds in her own four hands a bow, an arrow, a noose, and a goad. “This region,” we are told in a Tantric text, “is the gateway of the Great Liberation.” [16] It is the place variously represented in the myths and legends of the world as a threshold where the frightening Gate Guardians stand, the Sirens sing, the Clashing Rocks come together, and a ferry sets forth to the Land of No Return, the Land Below Waves, the Land of Eternal Youth. However, as told in the Katha Upanishad: “It is the sharpened edge of a razor, hard to traverse.” [17]

The yogi at the purgatorial fifth chakra, striving to clear his consciousness of the turbulence of secondary things and to experience unveiled the voice and light of the Lord that is the Being and Becoming of the universe, has at his command a number of means by which to achieve this aim. There is a discipline for instance, known as the yoga of heat or fire, formerly practiced in Tibet and known there as Dumo (gTum-Mo), which is a term denoting “a fierce woman who can destroy all desires and passions” [18]—and I wonder whether the classical legend of the Maenads beheading Orpheus, who had been brooding on his lost Euridice, may not have been a covert reference to some esoteric mystery of this kind. What this yoga first requires is the activation of the energy at the navel chakra, Manipura (chakra three), through a special type of breath control and the visualization of an increasing fire at the intersection (just below the navel) of all three spiritual channels:

At the start the blazing tongue of Dumo should not be visualized as more than the height of a finger’s breadth; then gradually it increases in height to two, three, and four fingers’ breadth. The blazing tongue of Dumo is thin and long, shaped like a twisted needle or the long hair of a hog; it also possesses all four characteristics of the Four Elements—the firmness of the earth, the wetness of water, the warmth of fire, and the mobility of air; but its outstanding quality still lies in its great heat—which can evaporate the life breaths (pranas) and produce the bliss. [19]

What is happening here is that the powers of the lower chakras are being activated and intensified, to force them to open and to release the energies they enclose; for these are the energies that in the higher chakras are to lead to sheerly spiritual fulfillments. In this introverted exercise, the aggressive fires of chakra three are being turned inward, against enemies that are not outside but within: to burn away obstructions to the Mother Light that are lodged within oneself. Thin as a needle, the Dumo fire is to be lengthened upward from the navel chakra to the higher centers of the head, to release from these an ambrosial seminal dew (as it is called), which is to be pictured as dripping, white, into the red Dumo fire. The white nerve ida is of this seminal dew, and the red, pingala, of the Dumo fire. The imagery is obviously sexual: the fire is female and the dew that it receives and consumes is male. Moreover, as the Tantric texts advise: “If these measures still fail to produce a Great Bliss, one may apply the Wisdom-Mother-Mudra by visualizing the sexual act with a Dakini, while using the breathing to incite the Dumo heat.” [20] Thus in this yoga the energies either of the sex instinct or of the will to power may be employed to assist in shattering and surpassing the limits of the lower instinct system itself.

A second type of exercise in this Tibetan series is known as “Illusory Body Yoga,” the aim of which is to realize in experience—not simply to be told to believe—that all appearances are void. One is to regard the reflection of one’s own body in a mirror and to consider (as the texts advise), “how this image is produced by a combination of various factors—the mirror, the body, light, space, etc.,—under certain conditions. It is an object of ‘dependent-arising’ (pratitya-samutpada) without any self-substance—appearing, yet void. . . .” One is then to consider how one’s own self, as one knows it, is equally an appearance.

Or one may practice in the same way a meditation on echoes. Go to some place where echoes abound. “Then shout loudly many pleasing and displeasing words to praise or malign yourself, and observe the reactions of pleasure and displeasure. Practicing thus, you will soon realize that all words, pleasant or unpleasant, are as illusory as the echoes themselves.” [21]

In a third yoga, known as the “Dream Yoga,” we immediately recognize a resemblance to certain modern psychotherapeutic techniques; for the yogi here is to cultivate and pay close attention to his dreams, analyzing them in relation to his feelings, thoughts, and other reactions. “When the yogi has a frightening dream, he should guard against unwarranted fear by saying, ‘This is a dream. How can fire burn me or water drown me in a dream? How can this animal or devil, etc., harm me?’ Keeping this awareness, he should trample on the fire, walk through the water, or transform himself into a great fireball and fly into the heart of the threatening devil or beast and burn it up.”

Next:

The yogi who can recognize dreams fairly well and steadily should proceed to practice the Transformation of Dreams. This is to say that in the Dream state, he should try to transform his body into a bird, a tiger, a lion, a Brahman, a king, a house, a rock, a forest. . . . or anything he likes. When this practice is stabilized, he should then transform himself into his Patron Buddha Body in various forms, sitting or standing, large or small, and so forth. Also, he should transform the things that he sees in dreams into different objects—for instance, an animal into a man, water into fire, earth into space, one into many, or many into one. . . . After this the yogi should practice the Journey to Buddha’s Lands.

Finally—and here the sense of it all becomes clear:

The Dream Yoga should be regarded as supplementary to the Illusory Body Yoga. . . . for in this way, the clinging-to-time manifested in the dichotomy of Dream and Waking states can eventually be conquered. [22]

Still another yoga of this series, going past the illusory forms of both waking and dream, is the “Light Yoga,” where one is to visualize one’s entire body as dissolving into the syllable of the heart center (in Tibet this syllable is hum) and this syllable itself, then, as dissolving into light. And there are four degrees of this light: (1) the Light of Revelation, (2) the Light of Augmentation, (3) the Light of Attainment, and (4) the Light of the Innate. Moreover, anyone able to do so should concentrate, just before going to sleep, on the fourth of these, the Innate Light, and holding to it even on passing into sleep, dissolve both dreams and darkness in that light. [23]

And with that, indeed, one will have passed into the state of Deep Dreamless Sleep awake.

When the tasks of the fifth chakra have been accomplished, two degrees of illumination become available to the perfected saint, that at the sixth, known as savikalpa samadhi, “conditioned rapture,” and finally, supremely, at the seventh chakra, nirvikalpa samadhi, “unconditioned rapture.” Ramakrishna used to ask those approaching him for instruction: “Do you like to speak of God with form or without?” [24] And we have the words of the great doctor ecstaticus Meister Eckhart, referring to the passage from six to seven: “Man’s last and highest leavetaking is the leaving of God for God.” [25]

The center of the first of these two ecstasies, known as the lotus of “Command,” Ajna, is above and between the brows. (See fig. 334.) The uraeus serpent in Egyptian portraits of the pharaohs appears exactly as though from this point of the forehead. The center is described as a lotus of two pure white petals, bearing the syllables ham and ksham. Seated on a white lotus near its heart is the radiant six-headed goddess Hakini, holding in four of her six hands a book, a drum, a rosary, and a skull, while the remaining two make the “fear-dispelling” and “boonbestowing” signs. Within the yoni-triangle is a Shiva lingam, shining “like a chain of lightning flashes,” [26] supporting the sign of the syllable om, of which the sound is here fully heard. And here, too, the form is seen of one’s ultimate vision of God, which is called in Sanskrit Saguna Brahman, “the Qualified Absolute.” As expounded by Ramakrishna:

When the mind reaches this plane, one witnesses divine revelations day and night. Yet even then there remains a slight consciousness of “I.” Having seen the unique manifestation man becomes mad with joy as it were and wishes to be one with the all-pervading Divine, but cannot do so. It is like the light of a lamp inside a glass case. One feels as if one could touch the light, but the glass intervenes and prevents it. [27]

For where there is a “Thou” there is an “I,” whereas the ultimate aim of the mystic, as Eckhart has declared, is identity: “God is love, and he who is in love is in God and God in him.” [28]

If we remove that glasslike barrier of which Ramakrishna spoke, both our God and ourselves will explode then into light, sheer light, one light, beyond names and forms, beyond thought and experience, beyond even the concepts “being” and “nonbeing.” “The soul in God,” Eckhart has said, “has naught in common with naught and is naught to aught.” [29] And again: “There is something in the soul so nearly kin to God that it is one and not united.” [30]

The Sanskrit term Nirguna Brahman, “the Unqualified Absolute,” refers to the realization of this chakra. Its lotus, Sahasrara, “thousand petalled,” hangs head downward, shedding nectarous rays more lustrous than the moon; while at its center, brilliant as a lightning flash, is the ultimate yoni-triangle, within which, well concealed and very difficult to approach, is the great shining void in secret served by all gods. [31] “Any flea as it is in God,” declared Eckhart, “is nobler than the highest of the angels in himself.” [32]

Notes

[1] Pliny, Natural History 6.26.101, 9.57.114, as quoted by Wilfred H. Schoff, The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea: Travel and Trade in the Indian Ocean by a Merchant of the First Century (New York: David McKay, 1916, 219, 240.

[2] Mircea Eliade, Yoga: Immortality and Freedom, Bollingen Series 56, 2nd ed. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1969), 200–1.

[3] I have discussed this matter at some length in The Masks of God: Oriental Mythology (New York: The Viking Press, 1962), 197–206. The critical texts are Brihadaranyaka Upanishad 2.1; Chhandogya Upanishad 5.3–10, 5.11–24, 7.1–25; and Kena Upanishad 3.1–4.2.

[4] Arthur Avalon (Sir John Woodroffe), The Serpent Power, 3rd rev. ed. (Madras: Ganesh, 1931),111, note 2.

[5] The Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna, trans. Swami Nikhilananda (New York: Ramakrishna-Vivekananda Center, 1942), 829–30.

[6] Avalon, Serpent Power, 21–22.

[7] Alain Danielou, Yoga: The Method of Reintegration (New York: University Books, 1955), 11.

[8] Avalon, Serpent Power, 117.

[9] Ibid., 115–18, 330–45, and plate 2.

[10] Ibid., 118–19, 355–63.

[11] Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna, 404.

[12] Chhandogya Upanishad 8.3.2.

[13] C. G. Jung, “The Psychology of the Child Archetype,” The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious, The Collected Works of C. G. Jung, trans. R. F. C. Hull, Bollingen Series 20, 17 vols. (Princeton: Princeton University Press; London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1960), 9.1. par. 291.

[14] Dante, La Vita Nuova, vol. 2, trans. Charles Eliot Norton, The New Life of Dante Alighieri (Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1867), 2.

[15] Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna, 499.

[16] Shatchakra Nirupana 30; Avalon, Serpent Power, 386.

[17] Katha Upanishad 3.14.

[18] Garma C. C. Chang, Teachings of Tibetan Yoga (New Hyde Park, NY: University Books, 1963), 73.

[19] “The Epitome of an Introduction to the Profound Path of the Six Yogas of Naropa,” trans. Chang, ibid., 63–64.

[20] Ibid., 68.

[21] Ibid., 82–83.

[22] Ibid., 92–94.

[23] Ibid., 96–101.

[24] Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna, 80, 148,180,191, 217, 370, 802, 868.

[25] Meister Eckhart, ed. Franz Pfeiffer, trans. C. de B. Evans (London: John M. Watkins, 1924–31), no. 96 (“Riddance”); 1:239.

[26] Shatchakra Nirupana 33; Avalon, Serpent Power, 395.

[27] Swami Yatiswarananda, “A Glimpse into Hindu Religious Symbology,” in Sri Ramakrishna Centenary Committee (ed.), Cultural Heritage of India, 3 vols. (Calcutta: Belur Math, 1937), 2:15.

[28] “The Soul Is One with God,” Meister Eckhart, 2:89.

[29] “Riddance,” ibid., 1:239.

[30] “The Soul Is One with God,” ibid., 2:89.

[31] Shatchakra Nirupana 40–41; Avalon, Serpent Power, 417–28.

[32] “The Soul Is One with God,” Meister Eckhart, 2:89.