Judaism

Roger R. Keller, "Judaism," Light and Truth: A Latter-day Saint Guide to World Religions (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2012), 206–29.

Judaism and Latter-day Saint Christianity are orthopraxic faiths, meaning that both focus more on how people practice their religion than on whether they know and understand all the theological intricacies.

Mount Sinai, Egypt. This is the traditional site where Moses received the oral and written Torah. Courtesy of Berthold Werner.

Mount Sinai, Egypt. This is the traditional site where Moses received the oral and written Torah. Courtesy of Berthold Werner.

Judaism is an ancient faith which shares strong ties with the other two great Abrahamic faiths—Christianity and Islam. There are fourteen million Jews in the world today, [1] with large concentrations in Israel and the United States. As we begin the study of Judaism, probably the most important thing to say to Christians is that they should forget most of what they think they know about Judaism, because their views are colored by reading the Jewish texts through the lens of Jesus’ life, death, and Resurrection. No Jew reads his or her texts the way Christians do. The same needs to be said for Latter-day Saint Christians because not only do they view Jewish texts through the lens of Jesus Christ but they also add an additional lens of the Restoration, thereby wearing bifocals. Hence, it is important that we permit the Jewish people to speak for themselves about their history, faith, and practice and not try to make them proto-Christians.

Origins

Abraham

The Jewish people trace their origins back to Abraham as the father of their faith. It was with Abraham, who probably lived around 1850 BCE, that God made a covenant in which he promised Abraham three things: that he would have numerous posterity, that this posterity would be a blessing to the nations, and that Abraham would receive a land:

Now the Lord had said unto Abram, Get thee out of thy country, and from thy kindred, and from thy father’s house, unto a land that I will shew thee:

And I will make of thee a great nation, and I will bless thee, and make thy name great; and thou shalt be a blessing:

And I will bless them that bless thee, and curse him that curseth thee: and in thee shall all families of the earth be blessed. (Genesis 12:1–3)

This covenant was the basis upon which Israel became God’s chosen people, through whom these promises would be fulfilled. “Chosenness” for the Jewish people means not that they hold a special status before God because they are better than others, but rather that they have a special vocation or calling. That vocation is to bless the world with the understanding that there is one God who cares about and guides its people. No faith is more singularly monotheistic than is Judaism, and this commitment to the one God is captured in what is known as the Shema, which is the Hebrew word for “hear.”

Hear, O Israel: The Lord our God is one Lord: and thou shalt love the Lord thy God with all thine heart, and with all thy soul, and with all thy might. (Deuteronomy 6:4–5)

It is this message that the Jews are to carry to the world both in word and in action. As the Jewish people faced persecution across the centuries, they tended to turn inward, isolating themselves from other peoples and nations simply to survive. For many Jewish people, that very persecution, however, affirmed that they were chosen for God’s service, because the evil in the world seemed to seek them out and try to destroy them. Where that much evil gathers, God’s people have to be present.

In addition to believing that they are to become a great people and bless the nations with their knowledge of the one God, the Jewish people also believe that God gave Abraham the land which is roughly equivalent to modern-day Israel. Thus, many Jewish persons see their claim to the land of the modern state of Israel as going back almost four millennia. Interestingly, it was only Abraham’s ancestors that finally claimed the land, for the only part that he owned was a cave in Hebron where he buried his wife Sarah and where he himself was finally buried. His primary role was to dedicate the land to God.

Part of the message of the one God was also that human beings were created in his image. No Jew believes that this means physical image, but the Latter-day Saint question would be, if not that, then what? In answer, there is more to the image of God than mere physical form, for with the attributes of deity, which is what Jews, Christians, and Muslims all understand to constitute the image, there does not need to be a form. A form, however, that does not have intelligence, rationality, relationality, compassion, mercy, and love is not created in the image of God. The Latter-day Saint understanding of the image of God is based on Joseph Smith’s First Vision, in which he saw the Father and the Son standing before him and seeing that both entities had physical form, which Latter-day Saints rightly stress. They sometimes forget, however, that those who hold that the image must include the attributes of God are also correct and that the complete understanding of “image of God” must include both form and attributes.

Moses

Abraham is the father of the Jewish people, but Moses is revered as the “Lawgiver.” It is Moses who ascended Mount Sinai and received both the Oral and Written Torah from the hand of God. The giving of the law was a sign to Israel of the Jewish people’s unique vocational standing before God, for the giving of the law was a sign of God’s favor. It was never a burden, and one of the Psalmists makes this very clear.

Blessed is the man that walketh not in the counsel of the ungodly, nor standeth in the way of sinners, nor sitteth in the seat of the scornful. But his delight is in the law of the Lord; and in his law doth he meditate day and night. (Psalm 1:1–2, emphasis added)

God gives the law to Israel, his chosen people, to keep them safe. When they walk within the boundaries of God has set for them, nothing can threaten Israel.

Sefer (handwritten) Torah raised during a bar mitzvah. The Torah is the most sacred part of the Tanak. Courtesy of Olivier Levy.

Sefer (handwritten) Torah raised during a bar mitzvah. The Torah is the most sacred part of the Tanak. Courtesy of Olivier Levy.

Many Jews believe that God gave Moses two things on Sinai—the Written Law and the Oral Law. The first is what Latter-day Saints would call the books of Moses (i.e., Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy). They are also known as the Pentateuch. In addition to these, Moses was also given the Oral Law, which was passed down from generation to generation and needed to be unpacked over time.

Moses received the Law from Sinai and committed it to Joshua, and Joshua to the elders, and the elders to the Prophets; and the prophets committed it to the men of the Great Synagogue (Mishnah, Aboth [The Fathers] 1:1). [2]

This means that according to the rabbis, everything after the books of Moses is an unpacking of the Oral Law. According to this view, when Isaiah says, “Thus says the Lord,” he does not mean that the Lord is speaking directly to him but rather that the Lord is inspiring him to say in his day and time what had been given to Moses on Sinai and passed down to him. Thus, a pronouncement today on cloning, for example, if accepted by the Jewish community, could be seen as liberating what was said at Sinai relevant to this issue.

Scripture

This is a good point to look at the Jewish conception of sacred writings, for they have several of them. The first collection of texts is the Jewish, or Hebrew, Bible. It has the same content, the same thirty-nine books, as the Latter-day Saint Old Testament but is in a slightly different order and is organized into three sections. Below are the sections arranged vertically, first with their Hebrew names and then the English translation of the names.

| T | N | K | L | P | W | |

| O | E | E | A | R | R | |

| R | V | T | W | O | I | |

| A | I | U | P | T | ||

| H | I | V | H | I | ||

| M | I | E | N | |||

| M | T | G | ||||

| S | S |

The Hebrew Bible is known as the Tanak, a word created by taking the first letter of each of the three sections of the Hebrew Bible (TNK) and putting a vowel between them—TaNaK. The most sacred portion of this is the Torah, or Law, which was given directly to Moses. The Law is read completely through every year in the synagogue. The major and minor Prophets and the Writings, such as Job, Psalms, Proverbs, and Ruth, are an unpacking of the Oral Law received by Moses and passed on to future generations. They augment the reading of the Law during the year in the synagogue.

The largest problem faced by rabbis, as interpreters of the Law, was that the Torah gave directions for life without telling people how to fulfill what was commanded. As a case in point, what does it mean to keep the Sabbath day holy? The rabbis answered this by limiting, for example, the distance persons could walk on the Sabbath, and today Orthodox Jews still live within walking distance of a synagogue. The rabbis also banned thirty-nine categories of work, which limits significantly what a person can do on the Sabbath so that the Sabbath truly became a day of rest.

The rabbis tried to help the Jewish people live an obedient life before God by defining rules for daily life under six headings: (1) agricultural laws, (2) regulations for various festivals, (3) laws of marriage and divorce and related topics, (4) civil and criminal laws, (5) temple laws, and (6) laws of purity. The discussions were extensive and contained rabbinic arguments on both sides of an issue. Around 200 CE, these discussions were finally written down as the Mishnah. Up to this point, the discussions had been preserved by persons who had exceptional memories, but even for them, the burden of memorization was immense. The English version of the Mishnah cited here has 789 pages. Imagine holding all that in memory.

The rabbinic discussions did not stop with the completion of the Mishnah. They continued as commentary on the Mishnah and were collected in a second group of writings known as the Gemara. However, there were two Gemaras—a Palestinian Gemara and a Babylonian Gemara. With the fall of Jerusalem and the Roman destruction of the temple in 70 CE, many Jews fled Palestine to many areas; including the largest Jewish community in the world, which was in Babylon. After the Bar Kochba rebellion in Palestine, which took place from 132 to 135 CE, the Romans were tired of this troublesome people and banned all Jews from approaching Jerusalem. Therefore, many more Jewish people migrated to Babylon, but some stayed and settled in Galilee, which was still permissible. The rabbis in this latter group produced the Palestinian Gemara, while those rabbis who were in Babylon produced the Babylonian Gemara. These were written down around 450 CE. The Palestinian Gemara covered more subjects than did the Babylonian, but not in as great a depth as the latter.

If we add the Mishnah and the Gemara together, we have the Talmud, but two of them—a Babylonian Talmud and a Palestinian Talmud. It is the former which is most authoritative for the Jewish community today. It is on the basis of the Talmud that rabbis, who are judges in Israel, make their legal decisions, which is their primary responsibility. They were never “pastors” as we understand that word today. They were scholars of the Talmud, and it was upon their scholarship that judgments were made as they brought these ancient opinions into contact with human issues.

There is one additional writing that informs Jewish life, and this is the Midrash. While the Talmud deals with primarily legal material, the Midrash is based on the biblical text and contains sermon-like material and commentaries on the biblical texts. Often the material is very practical concerning how one should live a Jewish life and contains stories of people who have lived as they should. Probably the closest thing to the Midrash among Latter-day Saints would be the Ensign, by which they are inspired to live a Latter-day Saint life through stories of fellow Saints doing so. Thus, the Tanak, Talmud, and Midrash constitute the “standard works” for the Jewish people.

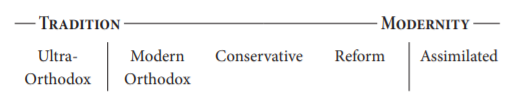

The People

The Jewish people are defined not so much by what they believe as by how they practice their faith on a daily basis. There are two words between which we need to distinguish: orthodoxy and orthopraxy. Orthodoxy means that people believe the right things. Orthopraxy means that people do the right things. The reason that many Christian denominations claim that Latter-day Saints are not Christians is because they are not “orthodox”—they don’t believe the right things. Within Judaism there is great latitude in what persons can believe. What is more important is whether Jewish people do the right things—“orthopraxy.” Thus, the degree to which Jewish persons’ lives adhere to “tradition” determines in large measure where they fall on the spectrum between “tradition” and “modernity.” Thus, the diversity of Jewish groups within American Judaism looks like the following.

Most Jewish persons live in the creative tension between tradition and modernity. Some, however, want nothing to do with the modern world. They have frozen time in response to the Enlightenment and thus still wear the clothing of seventeenth-century Eastern Europe. Their commitment is to keeping the traditions of Judaism while staying away from the enticements of the world. There is a tendency for Ultra-Orthodox Jewish people to live in enclaves where they can be separated from the broader community. They will live within walking distance of the synagogue, will keep a kosher kitchen (which we will explain later) and obey the kosher rules, separate men and women in the synagogue, have no women rabbis, and will not call a girl up to read from the Torah.

On the other end of the spectrum are people who have become so assimilated into the broader culture that they no longer see themselves as Jewish. They see themselves as British, American, or Canadian. Their identity lies outside Judaism, and they want no part in the traditions and practices.

Most Jewish people, however, live between the two poles of tradition and modernity. The Modern Orthodox Jews try to keep all the laws that are not related to the destroyed temple. Like the Ultra-Orthodox, they would live within walking distance of the synagogue, would separate men and women in synagogue, would keep a kosher kitchen and obey the kosher rules, would have no women rabbis, and would not invite girls up to read from the Torah.

Conservative Jews keep most of the traditional laws, but they see some of them as no longer relevant to the modern world. Conservative Jews would drive to synagogue, would probably not separate men and women in synagogue, and would keep the kosher laws and keep a kosher kitchen. Conservative Jews admitted women to the rabbinate in the mid 1980s, so both boys and girls may be called up to read from the Torah.

Reform Jews feel that the traditions were appropriate for the time in which they were instituted but that many traditions are no longer relevant to the modern world. For example, Reform Judaism has had female rabbis since the 1970s. Similarly, girls as well as boys are called up to read from the Torah when they reach the age of maturity. Families sit together in synagogue, and most Reform Jews would not keep a kosher kitchen and would not be fully bound by the dietary laws. Hence, there is wide diversity within American Judaism in the way Jewish people practice their faith.

Jewish Theology

As mentioned earlier, there is great diversity in Jewish thought. The one central belief is that there is one God in whose image human beings are created. Beyond this, most Jewish persons would hold that humans have two inclinations: a good inclination and an evil one. Having been endowed with free will, or agency, the Jewish people are to make decisions between good and evil as defined by God in the Law. Because of the inclinations within them, they can be drawn toward good or evil, and the environment in which they live has much to do with this. The Law is to help them create a positive environment and make appropriate choices—they are to be obedient to God’s commands. Because God has delivered the Jewish people from bondage in Egypt and continues to work in their midst, Jews should stand before him in awe and love. These are the motivating factors that lead to obedience. Beyond these basic principles, there is great variation in what Jews may believe because they are not defined by their beliefs (orthodoxy) but by their practice (orthopraxy).

Latter-day Saints will find much in these thoughts familiar. They understand agency or free will to be an eternal principle that cannot be abrogated. Even though human beings live in a fallen world, they still have their agency and can respond to God as he approaches them. Yes, there is an internal tension between what Latter-day Saints call the “natural man” and their better selves that know what God would have them do. They desire to do God’s will because they know he first loved them in Jesus Christ. As John states, “For God so loved the world, that he gave his only begotten Son, that whosoever believeth in him should not perish, but have everlasting life” (John 3:16). To that love Latter-day Saints respond in love. Out of that love Latter-day Saints act, and if their obedience is not rooted in their love for God, then their obedience is slavery.

Jewish Practices

Festivals

In the Jewish, Christian, and Islamic faiths, God works in history. He is not an absent deity but involves himself in the very fabric of human life. Therefore, most of the Jewish festivals remember God’s workings in particular events in Israel’s history. It is around these events that Jewish life revolves, creating a spiritual rhythm throughout the year. Below we will exam some of the principal festivals of the Jewish calendar.

Sabbath. Sabbath is the weekly festival that held Judaism together through its many difficult times across the centuries. Life revolves around the Sabbath, for beginning about the middle of the week, persons look forward to it and draw strength from it in expectation. In the first part of the week they look back on it, drawing strength from it in retrospect. The Sabbath celebrates two acts of God’s creative work: (1) the creation of the world and its people and (2) the creation of Israel through God’s deliverance of the people from Egypt.

Sabbath celebrations begin in the home just before sundown on Friday and extend through Saturday until three stars are visible in the evening sky. Just prior to Friday sundown, the woman of the house lights two candles and says a blessing over them. This ritual must be done prior to the actual Sabbath because one of the forbidden categories of work is lighting a fire. Following this, hands are laid on the children’s heads, and they are given a blessing. Sabbath begins with a synagogue service following which the family returns for the Sabbath meal at which there are two loaves of Sabbath bread and wine in addition to the meal. A Jew may be on the low end of the social structure during the week, but on Sabbath he or she is a king or a queen before God. Sabbath is a day of joy, and this is underlined by the double portion of light (two candles) and bread (two loaves) and the presence of wine.

Just as God rested on the seventh day, so also are the Jewish people to rest, and not only they but anyone else in the house. Thus, visitors, hired help, slaves, and animals are all to rest. According to early Rabbis there were thirty-nine categories of work which were not to be done. Worshiping, reading, praying, napping, walking a limited distance outside, and spending time with the family are all approved activities. However, in the modern world, cooking, telephoning, playing an instrument, driving (for Orthodox Jews), sewing, writing letters, text messaging, and using a computer are all forbidden. For them the Sabbath is truly a day of rest, and perhaps Latter-day Saints could learn something, since Sundays seem to be just another day of work, albeit oriented toward God’s work. However, even God rested on the seventh day, according to Genesis. “Can his children do less?” would be the Jewish question.

Rosh Hashanah. The Hebrew words "Rosh Hashanah" mean “head of the year.” In other words, this is a New Year’s Day which occurs in late September or early October, but it has far different connotations for the Jewish people than it does for most other peoples. When most people think of New Year’s Day, they think of celebrations and noisemakers and parties. However, Rosh Hashanah ushers in the Ten Days of Awe, which culminate in Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement. These are the most sacred days of the Jewish calendar. The symbol of Rosh Hashanah is the shofar, or ram’s horn, which is blown one hundred times during the day. The shofar has always been a horn of warning, in this case warning the Jewish people that in ten days God will sit down on his throne and determine what will happen in the next year. Thus, the Ten Days of Awe are a time of introspection during which people examine their lives, ask God for forgiveness for the things they have done against him, and ask their family and friends to forgive them for things they have done to harm them, since God cannot forgive these sins. They were not done against him.

Yom Kippur. As noted above, Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement, is the culmination of the Days of Awe. The people fast for twenty-five hours, dress in white as a symbol of purity, and focus on repentance for sins committed in the past year. All work is prohibited. At the end of the day, there is a service in the synagogue which ends on a note of hope, since all things now lie in God’s hands. Following the service people go home and break the fast as a family and begin the New Year.

Succoth. The Festival of Succoth, or Tabernacles, occurs five days after Yom Kippur. Originally a harvest festival, Succoth recalls the forty years of wandering in the wilderness following the Exodus from Egypt. Dependent upon which part of the Hebrew Bible one reads, the wandering had one of two meanings. The first, found in the book of Numbers, was punishment for Israel’s complaining and disobedience in the wilderness. Israel wandered for forty years until the entire generation that had come out of Egypt died. Even Moses and Aaron did not enter the promised land. The only exceptions were Joshua and Caleb, who believed God could have led them to victory in Canaan shortly after the Exodus. Because others did not have this degree of faith, they wandered until they were extinct.

The second view of the wanderings is found in Hosea. Here the period of wandering is viewed as the honeymoon between God and Israel. During these years, Israel was wholly dependent upon God for everything, and anyone who has ever been in the Sinai desert knows that Israel’s survival could have occurred only with God’s care. It is this view that Succoth underlines. It celebrates God’s providential care of his people.

The central symbol of Succoth is the Sukkah (the booth, or tabernacle). In the desert, people did not need shelter from rain but rather from the sun, so they built shelters. These are replicated during Succoth by building a booth on one’s balcony or in the backyard. The booth must have three sides and a roof through which one can see the stars. Thus, the roof is often made from palm leaves. Since Jewish festivals involve families and are tailored to interest children, the children get to decorate the Sukkah. Hence, their artwork and other things are put on the walls. The family is expected to take their meals in the Sukkah, and if the parents can be convinced to do so, they will all sleep in it, weather permitting. If a family has no place to build a booth, the synagogue builds one, and the family may go there to take their meals. Thus, Succoth is a time to remember God’s providential care of Israel, not just in the wilderness but always.

A two-story Sukkah made with palm leaves and a roof through which one can see the stars. Courtesy of Ori229.

A two-story Sukkah made with palm leaves and a roof through which one can see the stars. Courtesy of Ori229.

Passover and unleavened bread. Passover and the Festival of Unleavened Bread are the most sacred holidays in the Jewish calendar after the Days of Awe. Passover is a spring festival that occurs in March or April. The very name defines the festival, for it celebrates the angel of death passing over the homes of the Israelites in Egypt (Exodus 12:21–30). As the Jewish people celebrate the Passover, they “remember” what the Lord has done for them, but remembering in the Jewish context is not merely a mental exercise. Rather, it is participation in the event remembered. We see this in Deuteronomy 26:5–6. As the Israelites were on the verge of entering the land of Canaan, they were commanded to bring offerings to the Lord once they entered the land. The reason is articulated in the Deuteronomic passage as cited below.

And you shall make response before the Lord your God, “A wandering Aramean was my father; and he went down into Egypt and sojourned there, few in number; and there he became a nation, great, mighty, and populous. And the Egyptians treated us harshly, and afflicted us, and laid upon us hard bondage.” (RSV).

At the beginning of this passage, the people of Israel are recalling their history. The wandering Aramean was Jacob, or Israel. He went down into Egypt to escape the famine in his day, and then years later, his descendants were enslaved by the Egyptians. In this first part of the passage, the Israelites are in a sense standing outside the story. But suddenly things change! The Egyptians treat “us” harshly. No longer is this a remembered event. Now “we” are in the story. It is “we” that are in Egypt and suffering! So it is with the Passover festival. The Israelites are once again coming out of Egypt and being delivered by the Lord as they participate in the Passover meal. Once again, “we” are in Egypt. This is what true remembrance is. So also, as Latter-day Saints “remember” Christ in the sacrament, it should be more than a mere historical backward look. They take upon themselves Jesus’ life, suffering, death, and resurrection. They are there with him, and because they reparticipate in his atoning work, they leave the sacrament table as clean and pure as they were on the day of their baptism.

The Passover meal centers on four questions, [3] each asked by a child. As with most Jewish festivals, the next generation, the children, is always involved so that Jewish historical events become their events, too. The four questions are as follows, and each gives an opportunity to explain what God did for Israel at the time of the Exodus from Egypt.

1. Why is it that on all other nights during the year we eat either bread or matzoh, but on this night we eat only matzoh?

This festival is known as Passover and the Feast of Unleavened Bread (matzoh), also pronounced matzah. Passover lasts seven or eight days. The Israelites had to leave Egypt in such haste that the bread did not have time to rise, and so unleavened bread is a reminder of the pressure of exiting Egypt. Matzoh is like a cracker without a great deal of taste. Before Passover, every bit of leaven has to be removed from homes. Parents will plant rolls or other leavened items around the house for the children to find so that it can be removed. Matzoh is eaten all through the eight-day period. A serious event becomes an opportunity for children to participate and to begin to “remember.”

2. Why is it that on all other nights we eat all kinds of herbs, but on this night we eat only bitter herbs?

As should be evident most of the Passover ritual (Seder) is symbolic. Here the bitter herbs signify the bitterness of bondage and slavery. The bitter herbs are normally carrot stick–like pieces of horseradish. As one eats one of these, tears stream down the face, sinuses burn, and one definitely remembers the pain of forced labor. It gives a wonderful opportunity to explain what slavery meant for the Jewish people in Egypt and invites all participants, including children, into the events of Jewish enslavement in Egypt.

3. Why is it that on all other nights we do not dip our herbs even once, but on this night we dip them twice?

Before the meal, there is an appetizer usually consisting of lettuce leaves or celery stalks. The lettuce or celery is dipped into salt water, clearly a symbol of the tears of the enslaved. There is also a mixture of fruits and wine that is smeared on a piece of unleavened bread. On this are placed a couple of pieces of the bitter herbs, and then it is topped off with another piece of unleavened bread. This “sandwich” is then eaten. The fruit mixture recalls the mortar that the Israelites had to make to construct bricks while under the lash of their Egyptian task masters. Again, this is an opportunity to expand on the Exodus story, not only for the children but also for all gathered around the table.

4. Why is it that on all other nights we eat either sitting or reclining, but on this night we eat in a reclining position?

Most all the pictures of Jesus and his disciples show them seated at a traditional table on chairs while eating. One has to wonder how at Bethany Mary was able to anoint Jesus’ feet if this were the case (John 12:1–8). Did she just crawl under the table? Hardly, because Jesus and his disciples were reclining at the table at the Last Supper and undoubtedly at other meals. Many people of Jesus’ day ate at a table called a "triclinium." This was a table in a U shape, but it was only about a foot high. Servants could work in the "U" while the participants lay on their left sides on cushions around the outside of the table. Thus, Jesus’ feet were extended out from the table where Mary could have easy access to them. Likewise, we read in John that when Jesus announced that one of the disciples would betray him, Peter indicated to John to find out who it was. John tells us that the beloved disciple “then lying on Jesus’ breast saith unto him, Lord, who is it?” (John 13:25). John was reclining on the right of the Savior and simply leaned back and asked his question.

Clearly, this is not the usual table arrangement today. Thus, Jewish people, each time they drink one of the four cups of wine that are part of the Passover meal, lean to the left as they drink, simulating reclining at a table as in days of old. This entire festival represents their chosenness, their vocational position before God, and their ultimate victory over slavery and the powers of evil. Hence, Passover and the Festival of Unleavened Bread are celebrations of God’s liberating power.

The obvious parallels to Passover and Succoth among Latter-day Saints are the various persecutions and “exoduses” that they experienced as part of the church’s early history. Latter-day Saints had to flee from persecution in Missouri and Nauvoo, Illinois. The flight in 1846 and 1847 which led the Saints across the western plains to the promised land of the Great Basin is annually commemorated with Pioneer Day celebrations on July 24. For the most part, these are more like a Fourth of July event than a religious worship service. But there is an underlying thankfulness to God for his providential care during the great trek. This element is best captured in the great hymn “Come, Come Ye Saints.” The third verse is the Latter-day Saint hymn of the exodus.

We’ll find the place which God for us prepared,

Far away in the West,

Where none shall come to hurt or make afraid;

There the Saints will be blessed.

We’ll make the air with music ring,

Shout praises to our God and King;

Above the rest these words we’ll tell—

All is well! All is well! [4]

Once the Saints arrived in the Salt Lake Valley, the significance of the geography was not lost on them. There was a freshwater lake which drained into a salt lake after flowing through a forty-mile-long river which they named the River Jordan. The only real surprise is that they did not name Utah Lake the Lake of Galilee. Just as Passover and Succoth recognize God’s preservation of the Israelite people from the plagues of Egypt and terrors of the desert, so Pioneer Day recognizes God’s providential preservation of the Saints as they found their promised land in the West of the United States.

Purim. A popular festival is Purim, which remembers the story of Esther. King Xerxes ruled Persia from 486 to 465 BCE (he is presumed to be the King of Ahaserus mentioned in the book of Esther). At a banquet given for his nobles, Xerxes called for his wife, Queen Vashti, to come and let all his guests see how beautiful she was. Vashti, however, refused to come apparently because by this time, most everyone was quite drunk. As a result, Xerxes banished her from his presence because of the precedent that would be set for the wives of his nobility if the queen could refuse the order of the king without consequence. This, of course, meant that a new queen had to be found to fill her place, and ultimately the beautiful Esther was enthroned. Nobody, however, knew that she was Jewish.

Because of the animosity that existed between Esther’s uncle, Mordecai, and Haman, the king’s second in command, an edict was issued by the king at Haman’s instigation that all the Jews in the kingdom were to be destroyed in eleven months. Mordecai went to Esther and asked her to intercede with the king on behalf of the Jews. Because anyone entering the presence of the king without invitation would be killed on the spot unless the king extended his scepter toward that person, Esther asked Mordecai and the whole Jewish community to fast with her and her maidservants for three days. At the end of the fast, she entered the throne room, and Xerxes extended his scepter toward her and asked what she wanted. In response, she invited the king and Haman to dinner that night. When asked again what she desired, she invited the two to return to dinner the next evening, at which time she would lay her request before the king. That night, however, the king could not sleep, and so he read some of the recent chronicles of the kingdom, only to discover that Mordecai had saved the king’s life and had never been rewarded. Haman happened to be in the next room, and the king asked him how a person should be rewarded who had done a great service for the king but had never been recognized. Thinking that the king was referring to him, Haman suggested that the person should be clothed in robes the king had worn, placed on a horse the king had ridden, and then led through the streets by a high noble so that the people could all honor this person. The king told Haman to do for Mordecai what he had just suggested. That night, the king and Haman returned to dine with Esther. She disclosed Haman’s plot to destroy Mordecai and all the Jews for personal vengeance. The king had Haman hanged on the very gallows that Haman had built for Mordecai and issued an edict permitting the Jewish people to defend themselves when people sought to fulfill the first edict the king had issued, which could not be rescinded.

It is this story upon which the festival of Purim is based. Purim is a regular work day, but in the evening, all the children dress up as Xerxes, Esther, or Mordecai and go to the synagogue. They take with them noisemakers, and then the story of Esther is read. Each time the name Haman is pronounced, the room explodes in whistles, catcalls, and other noise. The person reading pretends to be upset, since he cannot read until the noise diminishes. As one approaches the end of the book of Esther, the name Haman is mentioned more and more frequently, and thus the decibel level rises progressively. It is an evening of good fun with a very serious message to proclaim about Jewish persecution and the way God protects his people.

Hanukkah. Hanukkah, like Purim, is a minor festival. Life continues as usual during it, but, Hanukkah resembles Purim in that it too remembers the persecution of the Jewish people and their deliverance. In this case, the persecutor was Antiochus IV of Syria, who had become enamored of Hellenistic (Greek) life. According to 1 Maccabees, he issued an edict in 167 BCE that all practices not in harmony with Greek ways were to be abandoned. What this meant for the Jewish people was that their Torah scrolls were to be destroyed, circumcision no longer practiced, the kosher laws ignored, and so on. In addition, the Syrians offered a pig on the altar of the temple, thereby polluting it. When one of Antiochus’s officials went to Modin, the hometown of the Maccabees, to gain compliance with the edict, he was unceremoniously killed by a Jewish priest named Mattathias. Mattathias and his five sons fled into the hills, where they gathered followers to oppose the Syrian forces. Judas, son of Mattathias, became the first leader of the Jewish forces. His additional name Maccabeus, which probably means “hammer,” was later applied to his whole family. Three years after Antiochus’s decree, the Jews took control of Jerusalem, enabling the cleansing and rededication of the temple. This became the basis for the eight-day long holiday of Hanukkah (“dedication”). According to a later Talmudic claim, part of that rededication was the relighting of the temple lamp, the menorah, but there was only enough pure oil to burn for one day. The miracle of Hanukkah, sometimes called the Feast of Lights, is that this limited supply of oil lasted for eight days until a new supply could be prepared. Thus, the central symbol of Hanukkah is a nine-branched menorah (distinct from the temple menorah with its seven lamps). Eight of the candles sit in a row, and a ninth candle sits above or behind the others. This last is known as the helper candle and is lit each night and then used to light the candles for that day (one on the first day, two on the second day, and so on). Once again, we have a festival remembering a persecution lifted by God’s hand.

Rites of Passage

There are two principal rites of passage in Judaism—circumcision and bar or bat mitzvah. Circumcision is performed on a male child on the eighth day following birth and is the ritual practice of removing the foreskin on the penis as a mark of the covenant between God and Israel. Today, virtually all males born in the United States are circumcised, but that is not the case in Europe. Thus, during the Nazi persecutions of the Jewish people, it was a relatively simple matter to identify Jewish men.

Bar mitzvah is performed in every form of Judaism. At the age of thirteen, a boy is called up to read the Torah lesson for the day, having studied Hebrew after school since first grade. He becomes a “son of the commandment,” which is what bar mitzvah means. He is now responsible for keeping the whole law. He has reached the age of accountability. Bat mitzvah commits a girl to the same standard of keeping the law, since bat mitzvah means “daughter of the commandment.” A girl who is a Conservative or Reform Jew studies Hebrew just like the boys and is called up at age twelve to read from the Torah. It is this reading that is the actual bar or bat mitzvah. The party afterward is completely secondary and unnecessary to the religious aspect of the rite.

Bar and bat mitzvah play a role similar to the baptism of boys and girls at age eight in the Latter-day Saint community. Baptism and confirmation recognize that at this age, young persons can now be held accountable for their decisions. Latter-day Saints are now to lead a life reflective of their life in Christ in the same way that a Jewish young person is to lead a Jewish life by following the commandments of God.

Bar Mitzvah at the Western Wall in Jerusalem. It is during this rite of passage that a young man becomes a "son of the commandment." Courtesy of Alwyn Loh.

Bar Mitzvah at the Western Wall in Jerusalem. It is during this rite of passage that a young man becomes a "son of the commandment." Courtesy of Alwyn Loh.

Purity

The center of ritual purity has always been the mikveh throughout Jewish history. In the excavated remains under the Wohl Museum in Jerusalem are the houses of priestly families. In every house there is a mikveh, which was a bath of “living water” with water running in and out of the bath. Before serving in the temple, the priests would immerse themselves in the mikveh, thereby removing ritual impurities which can be produced by any emission from the body. Today the mikveh is used primarily by Ultra-Orthodox and Modern Orthodox women.

At the beginning of a Jewish Orthodox woman’s menstrual period, sexual relations between husband and wife cease for fourteen days. At the end of those fourteen days, the woman dips herself in the mikveh at the synagogue and becomes ritually pure once again. Therefore, she and her husband can once again resume sexual relations. This timing also guaranteed larger families, as the fourteenth day of a woman’s menstrual cycle is usually near the day of ovulation. Rabbi Rosen, who taught in the Brigham Young University Jerusalem Center for Near Eastern Studies, felt that this ebb and flow of sexual relations between husband and wife kept a vitality in the Jewish marriage that was sometimes missing from the marriages in other traditions.

Prayer

Prayer is an important part of Jewish life and is usually considered a group process. Historically, ten men (a quorum) were required to hold these group prayers and are still required in Orthodox Judaism. However, Conservative Judaism allows women to be counted in the quorum if the rabbi of the synagogue permits them to be counted. Reform Judaism believes in complete egalitarianism between men and women, so women may always be part of the quorum.

During prayer, a prayer shawl is worn and a leather box is tied to the forehead and another box the left or right arm, depending on whether a person is left- or right-handed. A right-handed person, for example, would wear the small box on the left arm so that he or she could wind the strap with the right hand. During prayer, the head is covered with the prayer shawl, symbolizing that the wearer is wrapped in the responsibility of keeping God’s commandments. The leather boxes, known as tefillin or phylacteries, contain sections of scripture from Deuteronomy 6:4–9; 11:13–20; Exodus 13:1–10; and 13:11–16, all of which command that God’s word should be kept near one’s head and hand. [5] Both the boxes and the prayer shawl are physical reminders of the Jewish people’s obligations before God.

Kosher

The word kosher means “fit,” particularly fit to eat, as discussed in Leviticus 11:2–3, 9, and 13ff. This passage says:

These are the beasts which ye shall eat among all the beasts that are on the earth. Whatsoever parteth the hoof, and is clovenfooted, and cheweth the cud, among the beasts, that shall ye eat. . . . These shall ye eat of all that are in the waters: whatsoever hath fins and scales in the waters, in the seas, and in the rivers, them shall ye eat. . . . And these are they which they shall have in abomination among the fowls; they shall not be eaten, they are an abomination.

What this means for the Jewish diet is that they may eat cattle, sheep, and goats, all of which have a split hoof and chew their cud. They may not, however, eat camels, which do chew their cud but do not have split hooves. Likewise, the pig is off the menu, for although it has a split hoof, it does not chew cud. As far as life from fresh- or salt water, only those life forms that have fins and scales may be eaten, so this would mean most fish like salmon, trout, blue gills, and cod are permitted. However, eels, lobsters, shrimp, and oysters would all be forbidden. Most birds are not kosher because they live off carrion, which is unclean. Chickens and turkeys are, however, permitted.

Jewish people are always to live before God in constant awareness of his sovereignty over them. Every time Jewish people sit down to eat, they are reminded of the commandments of God because of the kosher rules. The author is convinced that a large reason for the kosher regulations is to bring discipline into the Jewish life, and discipline in one area—food—spills over into discipline in other areas.

There is another passage in the Hebrew Bible that has had a significant effect on Jewish kosher practice, and that is Exodus 23:19. The last part of the verse, almost in passing, states, “Thou shalt not seethe a kid in his mother’s milk.” Apparently, this was originally a pagan cultic practice, but as one thinks about it, it also seems to add insult to injury. A person takes a young goat from its mother, prepares it for cooking, and then milks the mother so that the young goat can be cooked in its mother’s milk. Something is wrong with this scenario! Be that as it may, what these verses have come to mean to Judaism is that milk and meat products should not be mixed. Thus, if persons go to a Jewish restaurant, they will be asked whether they wish to sit on the meat or milk side. Common things that most non-Jewish people eat which would be banned are cheeseburgers or pizza with pepperoni and cheese, for example. The ban of mixing meat and milk extends to the contents of a kitchen. A truly kosher kitchen would have two sets of plates, two sets of silverware, two sets of pots and pans, and perhaps even two sinks or two dishwashers. Each set would be fully dedicated to either meat or milk. Orthodox and Conservative Jewish people will generally keep kosher kitchens, while Reform Jews probably would not. Once again, we see the discipline in daily life that is required of practicing Jewish persons. Such discipline is a constant reminder that we always live before God.

Latter-day Saints also have their dietary rules, but they are not as all-encompassing as are the Jewish ones. The Word of Wisdom, found in D&C 89, addresses diet, and we have already examined these rules when we talked about vegetarianism in Jainism.

Women

Jewish and Latter-day Saint women have much in common. The focus for traditional women in both religions is the home and the children. Thus, their roles are different from those of men, but this does not mean that they are not equal to men, for they are. Both male and female are created in the image of God. Interestingly, Jews believe that God endows women “intuition” than men, and most Latter-day Saints would probably affirm that this is true. In traditional Judaism, women could be involved in commercial activities including buying and selling property. Seven of the fifty-five prophets mentioned in the bible were women (i.e., Sarah, Miriam, Deborah, Hannah, Abigail, Hulda, and Esther). [6] It is true that men and women are separated in traditional synagogues for prayer, but this is so that both will focus on their reason for being there, although women are considered to have the greater power of concentration. This is very similar to the Latter-day Saint practice of separating men and women in the temple so that both focus on the endowment ceremony. In Conservative and Reform Judaism, women’s roles have been enhanced, with women serving as rabbis and leading congregations. Latter-day Saint women also lead at virtually all levels of the Church but lead in relation to women and children, while men hold roles that require priesthood authority and thus serve as bishops, stake presidents, Seventies, Apostles, and members of the First Presidency. Having served in congregations outside the Latter-day Saint context, the author believes that these unique roles give men in the Latter-day Saint communion an identity and a function that they do not have in Protestant Christianity. For example, in the congregations where the author has served, women were often the stalwarts of the church, and the men were often unclear about the role they played. Priesthood clarifies this uncertainty.

Conclusion

There is much that is shared between Judaism and Latter-day Saint Christianity. Both are orthopraxic faiths, meaning that both focus more on how people practice their religion than on whether they know and understand all the theological intricacies. They are ways of life, with one faith group looking forward to the coming of the Messiah and the other looking back and claiming that he has come.

Notes

[1] “Major Religions of the World Ranked by Number of Adherents,” Adherents.com, last modified August 9, 2007, http://

[2] The Mishnah, translated from Hebrew with introduction and notes by Herbert Danby (London: Lowe & Brydone, 1967), 446.

[3] “Kosher4Passover,” Factor, LLC., http://

[4] William Clayton, “Come, Come, Ye Saints,” Hymns (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1985), no. 30.

[5] Leo Trepp, Judaism: Development and Life, 3rd ed. (Belmont, CA: Wadsworth, 1982), 273–75.

[6] Tracey R. Rich, “Prophets and Prophecy,” Judaism 101, http://