Islam

Roger R. Keller, "Islam," Light and Truth: A Latter-day Saint Guide to World Religions (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2012), 268–87.

Both Islam and Mormonism are highly ethical and moral faiths. For each, prayer is central to understanding God's will. Each has a historically rooted tradition that takes persons into God's presence and allows them to covenant with God that they will change their lives.

Mosque of Muhammad Ali Pashan, Cairo, Egypt. Mosque means "place of prostration." Copyright Val Brinkerhoff.

Mosque of Muhammad Ali Pashan, Cairo, Egypt. Mosque means "place of prostration." Copyright Val Brinkerhoff.

Given all the inaccurate media attention Islam has received since 9/

Origins

Islam and Muslim

As we begin, we should clarify two terms: Islam and Muslim. Islam means “submission,” in this case submission to God. A Muslim is “one who submits.” Thus, Islam is the name of the faith, and Muslims are those who practice the faith. There are no “Islams,” only Muslims, although one may speak of the “Islamic faith” or of “Islamic institutions.”

Pre-Islamic Arabia

The origins of Islam lie in what is today Saudi Arabia. The heart of pre-Islamic Arabia was the oasis of Mecca, which held prominence for two reasons. First, it was a major caravan stopping point on the trade route which ran from present-day Syria in the north to Yemen in the south. It was therefore quite cosmopolitan, since persons of various nationalities and religions passed through it. Its inhabitants were also caravanners, so they too traveled and came into contact with Byzantines and Persians from the two dominant empires to the north.

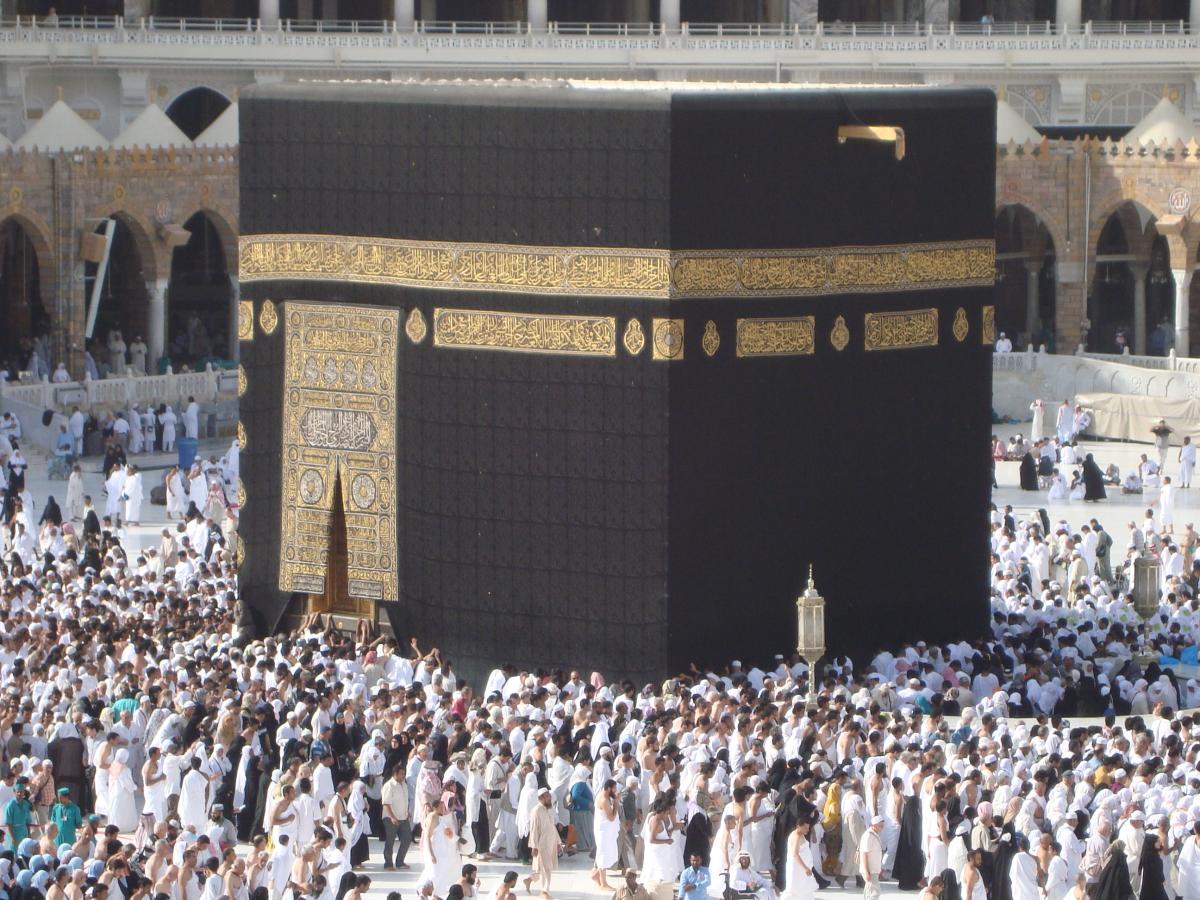

Mecca’s second claim to fame was that it was a religious pilgrimage center, for there was a shrine in the midst of it called the Ka’aba, a cube-shaped structure around and in which were statues of the multiplicity of gods that were worshiped on the Arabian peninsula. There was the high God known as Allah, which simply means “the God” in Arabic, but he was distant. Hence, his three daughters and other, nearer figures known as jinn—which were fairylike beings made from fire—were worshipped. [2] We meet one of these in the story of Aladdin and his lamp, for the English word for jinn is genie. These could be friendly or hostile. There were also ghouls, which were evil. Consequently, the world was filled with beings that needed to be appeased, and Mecca offered a center for the worship and control of all these beings. It was into this environment that Muhammad was born.

Muhammad

The Meccan years. Muhammad was born in 570 CE and died in 632 CE. His father died before he was born, and his mother died when he was six, leaving him an orphan. He lived briefly with his grandfather, but his primary caregiver was his uncle Abu Talib, who was respected but not particularly well-off financially. He was a caravanner, so Muhammad was able to travel with him as far north as Syria. In his travels, Muhammad met Christians and Jews. There is no evidence that he read their holy books, and Muslims make the point that Muhammad was illiterate and could not have created the Qur’an. Latter-day Saints often stress the marginal formal learning that Joseph Smith had to emphasize that he could not have created the Book of Mormon.

Muhammad had some concerns as he grew to adulthood. The polytheism and idolatry around him troubled him. He believed that there was one God. Also, the religious festivals in Mecca were often excuses for immoral behavior on the part of the participants. In addition, he was deeply troubled by the female infanticide that was too often practiced in his culture. The dowry laws required that the family of the bride pay a large dowry to the family of the groom. Many families of girls found this difficult, if not impossible, to do, so upon the birth of a daughter, they would simply take her out and bury her alive in the sand.

Muhammad followed the trade of his uncle and was hired to manage the caravans of a wealthy widow named Khadija. She became so impressed with Muhammad’s integrity and honesty that she proposed marriage to him when he was twenty-five and she was forty. They had six children, four daughters and two sons. Both of the sons died young, and only one daughter outlived Muhammad. It was a very happy marriage. Khadija was Muhammad’s friend and confidant as well as his wife.

Once married to Khadija, Muhammad had space in his life to pursue his religious interests. Annually he would go on a retreat to Mount Hira north of Mecca and there join other individuals seeking the one God. On one of these retreats when he was forty (610 CE), he received his call to be a prophet of God. While the Qur’an is not a biography of Muhammad, there are a few chapters which reflect some aspects of this early period. For example, in Sura 53 (chapter 53) of the Qur’an we read:

By the Star when it goes down,—your companion is neither astray nor being misled, nor does he say (aught) of (his own) desire. It is no less than inspiration sent down to him: he was taught by one mighty in power. Endued with wisdom: for he appeared (in stately form) while he was in the highest part of the horizon: then he approached and came closer, and was at a distance of but two bow-lengths or (even) nearer; so did (Allah) convey the inspiration to his servant—(conveyed) what he (meant) to convey. The (prophet’s) (mind and) heart in no way falsified that which he saw. (Sura 53:1–11) [3]

This sura reflects Muhammad’s call on the Night of Power. Just before dawn the angel Gabriel appeared on the horizon and drew within two bow shots (possibly two hundred yards) of Muhammad. He then called him to read or recite: “Proclaim! (or Read!) In the name of thy Lord and cherisher, who created—created man, out of a leech-like clot; Proclaim! And thy Lord is most bountiful,—he who taught (the use of) the Pen,—taught man that which he knew not” (Sura 96:1–5). Muhammad had no idea what he was supposed to proclaim or read and was terrified, so he fled down the mountain to Khadija. It was Khadija who assured Muhammad that this experience was from God. Once Muhammad accepted his call, he would receive revelations from God or Gabriel by either hearing them or receiving them in his mind. [4] Once he had memorized the message, he would repeat it to family and close friends and occasionally at the Ka’aba, the cubic shrine.

Muhammad’s message challenged idolatry, thereby endangering one of Mecca’s primary sources of income. In addition, his revelations called for social justice, including duties to the poor and the elevation of women in society. All this had the potential to undercut the social fabric of Mecca, so the ruling tribe, the Quraysh, aligned themselves against Muhammad and the handful of followers that had gathered around him. Even though he was supported by several influential persons in the community—Khadija, his uncle Abu Talib, and his future father-in-law, Abu Bakr—Muhammad was progressively marginalized, and his followers were persecuted. Problems became so great that Muhammad sent some Muslims to Abyssinia (current-day Ethiopia) to find religious freedom. They were followed by representatives of Mecca to try to convince the king of Abyssinia to send them back, but after a debate between representatives of the two groups, the king decided to permit the Muslims to stay and ejected the Meccans.

In 619 Khadija died, and shortly thereafter, Abu Talib, never a Muslim, died, removing two of Muhammad’s primary supporters. In addition, the persecution deepened as Muslims were not allowed to participate in Meccan trade, thereby removing their livelihood and bringing them down into poverty. Even Abu Bakr was shoved to the edges of the community. In 620, as Muhammad was mourning at the Ka’aba, Gabriel and other angels appeared to him, placed him on the back of a winged horse named Buraq, and flew him to Jerusalem. After leading prior prophets—Adam, Moses, Abraham, and Jesus, to name a few—in prayer, Muhammad ascended through the heavens into God’s presence, where he was commissioned as the seal of the prophets, meaning that he confirmed their messages and that he was the last prophet.

The persecutions in Mecca continued, and in 622, six men from the community of Yathrib, about two hundred miles to the north of Mecca, arrived for pilgrimage in Mecca. They had another objective, however, and that was to find a person to lead their community. They had heard of the Prophet, so they interviewed him and then offered him leadership of the community without conditions. Muhammad accepted and began to send his followers in small groups to Yathrib. Word spread that the Prophet was planning to leave, but the last thing the Meccans wanted was for him to be two hundred miles to the north, where he could cause real trouble. Consequently, a pact was made that one person from each clan would participate in the assassination of Muhammad, thereby preventing reprisal by one clan upon another. Word of the plot reached Muhammad, and he and Abu Bakr fled Mecca, arriving in Yathrib after eight days of travel. The trip to Yathrib is known as the Night Migration (Hijra) and marks a turning point in Muslim history, for from this point on, Muhammad could establish his own institutions within the faith. The year 622 CE is also the beginning of the Muslim calendar, which is lunar and therefore has a slightly shorter year than the solar year. Thus, 2011 is 1432 H., or 1432 lunar years after the Hijra.

The Medina years. Once Muhammad arrived in Yathrib, the name of the town was changed to Medina, meaning “city of the Prophet,” and it truly was that. Here he laid the foundation for the practices of Islam. He erected the first mosque in Medina. Mosque means “place of prostration,” which can be anywhere, but the first building used as a place of prostration or prayer was constructed in Medina. Prostration during prayer was begun with worshipers facing Jerusalem, the place from which Muhammad ascended to the presence of God. However, because many of the Jewish population in Medina were working with the Meccans behind the Prophet’s back, the direction of prayer was changed when a revelation came directing the worshipers to face Mecca. Weekly services were established on Friday, and the call to prayer was first given prior to those services. Shortly, the call was given before each prayer time. Finally, the taking up of alms for the poor and in support of the cause was instituted.

The Medina years for the most part were not years of peace. The Muslims understood themselves to be in a state of war with Mecca because they had been unjustly evicted solely because of their faith. Sura 22:39–40 states, “To those against whom war is made, permission is given (to fight), because they are wronged;—and verily, Allah is Most Powerful for their aid;—(They are) those who have been expelled from their homes in defiance of the right,—(for no cause) except that they say, ‘Our Lord is Allah.’”

As those who had been unjustly driven from Mecca, the Muslims had no compunction about raiding the Meccan caravans. This led to several battles with mixed results for both sides. In 628 CE, Muhammad and his unarmed followers went on pilgrimage to Mecca, placing the Meccans in a very difficult position because as guardians of the Ka’aba, they had to allow all pilgrims access to it. This forced the Meccans to negotiate with the Muslims on an equal footing. The result was a ten-year peace treaty in which the Muslims agreed not to enter Mecca that year, but every year hence they could go for three days, and the Meccans would allow them access to the shrine. In 630 CE, a tribe allied with the Meccans attacked a tribe allied with the Muslims, and the Muslims saw this as breaking the treaty. When the Muslims appeared ten thousand strong on the hilltop above Mecca, the Meccans capitulated. Many expected there to be a bloodbath because the Muslims had been so badly treated by the Meccans. The Prophet, however, simply issued a general amnesty except for anyone who attacked the Muslims. This amnesty should tell us a good deal about the character of the Prophet Muhammad as well as the nature of Islam.

After delivering the Qur’an and the foundational principles and practices of Islam, Muhammad died in 632 CE after a brief illness.

Without going into detail, Latter-day Saint Christians will see many parallels between Muhammad and Joseph Smith. Both received their call through a divine vision or encounter. Each was to deliver the final message from God. Each faced persecution and opposition, and each established his own city and center for the faith. The Muslims ultimately won over their enemies, partly through a show of power. The prophet of the Latter-day Saints, however, was assassinated, and the Saints then had to flee Nauvoo, the city of Joseph, into the wilderness. There they were still followed and hounded even to the degree that they stood ready to burn their homes and move on once again if the government chose to try to force them to live differently than they believed God called them to live.

Successors to the Prophet. Upon Muhammad’s death, there was no clarity concerning his successor. Most Muslims thought the senior companion, Abu Bakr, should be the successor, or Caliph. A small portion believed that the successor should be Ali, Muhammad’s cousin and son-in-law, since they thought succession should follow family lines. This discussion should be familiar to Latter-day Saints, since upon the death of Joseph Smith his successor was not clear. Most followed Brigham Young, the President of the Quorum of Twelve, while some believed that Joseph Smith III should succeed his father. In both religious traditions the majority prevailed, but a small minority group continued. In Islam the majority are known as Sunnis, while the minority are known as Shi’ites, or the “party of Ali.” Among Latter-day Saints, the majority is The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, while the minority was known as the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints and is known today as the Community of Christ.

The first three successors to the prophet were Sunnis—Abu Bakr, Omar, and Uthman. Finally, Ali became the fourth successor, but he was unable to heal the rift between the two groups, finally being assassinated. He was succeeded by his son, Hussan, who abdicated after a year, and then by another son, Husayn. Husayn and a small group of Shi’ites were massacred by a large group of Sunnis in 680 CE, and the Caliphate passed back to the Sunnis. However, the Shi’ites never believed that the first three Caliphs were legitimate and believed that only with Ali and his sons had the leadership passed into legitimate hands, with leaders known as Imams. The difference between a Caliph and an Imam is that the Caliph was primarily a political leader but not a religious leader of the community as was. The office of the Caliph ended with the fall of the Ottoman Empire in 1918. The Imam, on the other hand, had both a political and religious aura about him. He was not a prophet but was more than a political leader and carried religious authority. Hence, in Iran today, it is the religious head of the country, not its president, who is the true leader.

The Sunnis and the Shi’ites

Islam has numerous groups within it. It is not at all homogeneous, but the discussion above requires us to look further at the Sunnis and the Shi’ites. As we have seen, they arose out of the debate over who should succeed the Prophet. Eighty-five percent of the Muslim world is Sunni, and fifteen percent is Shi’ite. Most of the Shi’ite population live in Iran (95 percent Shi’ite) and Iraq (60 percent Shi’ite). Sunnis are widely dispersed around the world, with the largest Muslim country being Indonesia. Both groups claim to follow the traditions of the prophet and, therefore, practice much the same way. Shi’ism, however, has always seen itself as the true preserver of Islam but has felt marginalized in the Islamic world.

The uniqueness of the Shi’ites is that they do not believe that the succession of Imams ended with the death of the third Imam, Husayn. Most believe that the succession continued until the Twelfth Imam, who rather than dying went into hiding in 873 CE. He continued to communicate with the community through persons known as “gates,” or “Babs.” At a future date, he would return as the “restorer” to prepare the way for the return of Jesus, who Muslims believe did not die on the cross (someone else did), rather asserting that he was taken up to heaven and will return as he promised. When he returns, he will usher in a short period of peace, die, and be buried next to the Prophet Muhammad. At the time of the Resurrection, the two will rise together. Before the resurrection, the righteous and the wicked dwell in their graves. The graves of the righteous are spacious and light, and these people receive daily visions of the place awaiting them in heaven. The wicked are also in their graves, which are small and crush in on them. They too receive daily visions, but of their place in hell. At the time of the resurrection, the wicked and the righteous will rise and enter their final destiny—the joys of heaven or the pains of hell.

Sunnis also believe in a future restorer, but he is an unknown figure. He too will come to prepare the way for Jesus’ return, who when he comes will usher in the age of peace, die, be buried next to the Prophet, and then rise alongside him. Hence, the major difference between the two groups is over the identity of the future restorer. Is he unknown, or is he the Twelfth Imam who will return?

Muslim Thought and Practice

The Five Pillars of Islam

Statement of faith. Islam’s fundamental theology is captured in the faith statement, “There is no God but Allah, and Muhammad is his messenger,” and when persons say this with faith before two witnesses, they become Muslims. The first thing to notice about the confession is that God (Allah) is before all things. He is uncreated, all-knowing, and all-powerful. Nothing exists outside of him that he has not made. No greater sin exists than to try to put something in his place. It is this God who communicates with and gives commandments and guidance to the human race, whom he created. He sends his messages in three ways.

First, he sends prophets, and Muslims would agree wholeheartedly with the statement in Amos 3:7: “Surely the Lord God will do nothing, but he revealeth his secret unto his servants the prophets.” The first prophet was Adam, and later came Noah and Abraham. At Abraham there is a split in the tree of prophets, with Isaac being the forerunner of the Jewish and Christian side, which culminates in Jesus, and Ishmael being the precursor of the side that concludes with Muhammad. Through all the Jewish, Christian, and Islamic prophets, God has spoken to the human family. Some of them, like Jesus and Muhammad, have left texts and are known not only as prophets but also as “messengers,” while others have simply spoken God’s word in their day and time and are prophets. Given this, it is most proper to speak of Muhammad as a messenger.

Secondly, God communicates through angels who were created to live in the heavens and serve God. We have already met one of these in the person of Gabriel. It is probably wise to realize that there is a “dark side to the force.” When God created Adam, he required all the angels and jinn to bow down to him, but one jinn, Iblis, refused to do so, saying that he was a being of fire, while Adam was just a piece of dirt. He is the satanic figure in Islam. As in Christianity, he has no power of his own but can do only that which God permits.

Thirdly, God communicates fully and finally through the Qur’an, and if we are to understand Islam, we need to stop and consider the Qur’an more fully. The best way to understand its importance is to compare its place in Islam with the place of the Word of God in Christianity. In both Christianity and Islam, the Word of God exists with God. If we think of the incarnate Word in Christianity, it is Jesus Christ, and the Bible is what delivers him to us. Thus, to attack Jesus in any way is to attack the very heart of the Christian faith. In Islam, the Word of God becomes incarnate in a book, the Qur’an, and to be perceived as attacking it is to attack the heart of Islam. The Qur’an is delivered by Muhammad the messenger. Thus, what at a cursory glance seems like an equation of Jesus/

With the coming of the Qur’an, many reforms took place in Arabian life. The Qur’an prohibited the use of alcohol. It forbade gambling. It elevated women, which we will discuss later. It banned aggression while permitting defensive warfare. Thus, it changed the ethical climate of Arabia.

Prayer

Prayer is at the heart of the Muslim life. Perhaps another word for it might be “praise,” for Sunni Muslims stop five times each day to praise God and pray to him (Shi’ites pray three times). The call to prayer is given from mosques before each prayer time: before sunrise, midday, midafternoon, sundown, and nightfall. The prayer call gives a sense of the character of Muslim prayer, and the elements are generally repeated at least twice.

God is most great.

I witness that there is no God but Allah.

I witness that Muhammad is the messenger of Allah.

Come to prayer.

Come to salvation and prosperity.

God is most great.

There is no God but Allah.

There is a definite pattern of rituals that goes with these prayer times. The first rite is to wash the hands, mouth, nose, right arm, and left arm. The worshiper then wipes his or her hand over the head and then washes the right foot and then the left foot. Most of the washings are done three times as ritual purification prior to prayer. The prayers are led by the Imam or by a prayer leader, who may be any knowledgeable male. Later we will look at women’s piety. Women are not excluded from the mosque but are generally at the sides, at the back, or in a balcony. There are various postures assumed during the prayers, from standing to kneeling to prostration, and it is the latter position that is central to prayer, for it is a graphic demonstration of “submission.” Many Muslims, after a lifetime of prayer, will have the “mark of prostration” on their foreheads—a bruise from pressing their foreheads to the floor. Practicing Muslims stop five times a day for about twenty minutes to remember and praise God. What a wonderful way to establish a continuing religious presence in one’s life, for every act becomes informed by these regular prayer times. At the end of the prayers, the worshipers shake hands with those on either side of them to signify inclusion in the community.

Prayer tower (minaret), Abu Dhabi, UAE, from which the calls to prayer are announced. Prayers are at the heart of Muslim life and are led by an Imam or prayer leader. Public domain.

Prayer tower (minaret), Abu Dhabi, UAE, from which the calls to prayer are announced. Prayers are at the heart of Muslim life and are led by an Imam or prayer leader. Public domain.

Friday’s midday prayers are special services during which all men are expected to attend the mosque. Women, because of their family responsibilities, are excused from them but may come if they wish. The primary difference between the Friday midday prayer and those on other days is that there is a sermon delivered. The sermon can touch on many things, but it can at times be very highly political. In 2011 we saw the Friday prayers spill out into the streets of Algeria, Egypt, Syria, and other Middle Eastern countries as people voiced their desire for political freedom.

Almsgiving

Muslims are expected to give to charitable causes, and when they give alms, they purify their remaining resources for their own use. This is much like Latter-day Saints, who give 10 percent of their income and by doing so consecrate the other 90 percent for personal use. In Islam, the amount varies depending upon the kind of property that is involved. For example, persons give one-tenth of the produce of the land. However, from cash assets that have been held for over a year, people are to give 2.5 percent. Houses, furniture, personal possessions, and the things which a person uses to make a living are not assessed. But this is really only the base. Most Muslim countries do not have the social safety nets that Western countries do, so the care of the poor falls on the community. After Friday prayers, there will always be persons standing outside the mosques with their hands out for contributions. These are the poor, and this is the community’s way of caring for them, so almsgiving is an ongoing process.

The fast

During the month of Ramadan, the month in which Muhammad was called, Muslims are required to fast. Since Islam is on a lunar calendar that is not periodically corrected, it is impossible to tie Ramadan to the Western calendar. Ramadan moves through the entire calendar approximately every thirty-three Islamic years. The month is a time of personal self-examination, and usually Muslims read the Qur’an completely through. The fast lasts for thirty days. Fasting means that no one may eat, drink, smoke, or have sexual relations during the daylight hours. Fasting begins each morning when it becomes light enough to tell the difference between a black and a white thread and ends when that difference can no longer be distinguished. After sunset, the fast is traditionally broken with a few dates and some juice. Later in the evening, families gather for large meals, but they are to invite the poor to join them or provide food for the poor. Before early morning prayers, a meal is eaten, and then the fast begins again for the day as people remember the miracle of Muhammad’s call and his bringing of the Qur’an.

Pilgrimage (Hajj)

The pilgrimage to Mecca is expected once in the lifetime of each person who is physically and financially able to go. It has parallels with the endowment ceremony in that it is centered on scriptural characters and ultimately leads to a place that is considered to be in God’s presence. After completing their own pilgrimages, persons may then go on behalf of others who are unable to go, or they may go even for the dead, much as Latter-day Saints do vicarious work for the dead in the temples. The pilgrimage is held in the last month of the Islamic calendar year and, like the fast, moves over time through the year. The pilgrimage lasts for six days, beginning on the eighth day of the month. Persons can go to Mecca at other times of the year and do some of the rituals of the pilgrimage, but those visits do not count as a pilgrimage. It must be done with others at the defined time. Only Muslims are allowed in Mecca and Medina because these are sacred space to Muslims in the same way that temples are sacred space to Latter-day Saints. Nothing secret goes on in either case, but persons who are not Muslims or Latter-day Saints cannot attend the pilgrimage or the temple.

Persons arrive in Mecca ahead of the pilgrimage, and as they approach a line outside Mecca, males put on the ihram and take upon themselves the state of Ihram. The ihram as a garment is two pieces of white cloth, one which is wrapped around the waist and the another which is worn over the left shoulder. All men must wear this and remove all signs of rank or wealth. Women may wear a white garment but are not required to do so. Instead, they may wear their native dress. Thus, those persons dressed in white show the unity of Islam, while those women dressed in their native clothing highlight the diversity of Islam. The state of Ihram is a state of purity in which no sexual contact is permitted and nails and hair are not cut. Also, green trees may not be harmed or animals killed, except dangerous ones such as scorpions. As we examine the pilgrimage, we will highlight the major events, leaving out some of the lesser rituals.

Day one—the eighth day of the month. The first act of the pilgrimage is to walk around the Ka’aba, which Muslims believe Abraham and his son Ishmael built on a site where Adam had built an altar. This introduces the narrative that will be followed through the pilgrimage, which focuses on Abraham, Hagar, and Ishmael. When Sarah, Abraham’s wife, was unable to have a child, she offered her servant, Hagar, as a wife to Abraham, according to Islamic tradition. When Hagar had Ishmael, a jealous Sarah required Abraham to drive out Hagar and Ishmael, who eventually found themselves near the present site of Mecca. Hagar saw that Ishmael was rapidly dehydrating and so began a frantic search for water, running back and forth between two low hills. While she was doing this, Ishmael was lying under a bush kicking his heels in the sand. Suddenly, water appeared under his feet, and through God’s goodness they were both saved.

Ka'aba, Mecca, Saudi Arabia. The first act of pilgrimage is to walk around the Ka'aba. Courtesy of Aiman Titti.

Ka'aba, Mecca, Saudi Arabia. The first act of pilgrimage is to walk around the Ka'aba. Courtesy of Aiman Titti.

Thus, after circling the Ka’aba, the next major act is to walk rapidly back and forth between the two low hills, imitating Hagar’s search for water. Following this, the pilgrims drink from the well Zamzam, which is believed to have appeared in response to Ishmael’s and Hagar’s needs and which reminds the pilgrims that God will also meet their needs. Following these rituals, people begin to move out of Mecca toward the town of Mina, which is about four and a half miles away. There they perform the evening prayers and spend the night.

Day two—the ninth day of the month. The morning prayer is done in Mina, and then the pilgrims move another four and a half miles toward Arafat, where they must be by noon. Arafat is a broad plain with a volcanic cone in its center. It is at Arafat that the “standing ceremony” takes place, for this is where the worshipers are closest to God and where he is most ready to forgive. Worshipers may read the Qur’an, recite prayers, ask forgiveness, repent of their sins, or listen to impromptu sermons. Each Muslim stands alone before his or her God in the midst of two million other people. If one does not participate in the standing ceremony at Arafat, one has not done the pilgrimage. This is the celestial room of the pilgrimage. At sundown people leave Arafat quickly and return about a quarter of the way to Mecca, stopping at Muzdalifah for the night prayers.

Day three—the tenth day of the month. The morning prayer is said in Muzdalifah, and then the pilgrims move once again toward Mina. As they go, they pick up either 49 or 70 pebbles. Upon reaching Mina, the largest of the three pillars of Satan is stoned with seven stones. These pillars represent the three times that Satan appeared to Abraham and Ishmael as they were going to sacrifice Ishmael at God’s command. Each time Satan appeared and tried to dissuade them from performing the sacrifice, they drove him away by throwing stones at him. As the pilgrims stone the great pillar, they are stoning their own Satans and temptations and recommitting themselves to following God’s ways.

Notice that it is Ishmael who is to be sacrificed in Muslim thought, not Isaac as in Christian and Jewish belief. Muslims point out that even the Old Testament says that it was Abraham’s only son (Genesis 22:2) who was to be sacrificed, even though the text identifies that son as Isaac. However, according to Muslim thought, the son of Abraham, who was truly “the only son,” was Ishmael, and Isaac was never Abraham’s only son. He was his second son.

Following the stoning of the pillar of Satan, Muslims may offer a sheep, a goat, a cow, or a camel. In the past, pilgrims slaughtered the animal, but today one may buy a voucher which guarantees that an animal will be sacrificed in the pilgrim’s name and its meat packed and sent to the poor. This sacrifice recalls that God provided a substitute for Ishmael through the ram caught in the bush, and as the animal is sacrificed, persons should recall God’s providential care of them also.

After the sacrifice, the state of Ihram ends, and men have their heads shaved and women have a lock of their hair cut. Essentially, the constraints of the state of purity are lifted except the one banning sexual contact. Pilgrims return to Mecca to circumambulate the Ka’aba seven times as before, and then they return to Mina for a three-day festival. On each of the three following days, seven stones are thrown at each of the three pillars of Satan. People can leave after the twelfth or thirteenth day of the month. Whichever day they leave, they return to Mecca, walk around the Ka’aba seven times, and ask permission from God to end the pilgrimage. Some then go on to Medina, only two hundred miles to the north, and some even go on to Jerusalem, the third holiest city to Muslims. Trips to Medina and Jerusalem are not a part of the pilgrimage.

Jihad—A Sixth Pillar?

Some Muslims claim that jihad is the sixth pillar of Islam, but much hangs on how one translates the word. The literal meaning is “struggle” or “striving,” and so any struggle for the faith, such as reading the Qur’an, saying prayers, or participating in the fast or the pilgrimage could be jihad. The Prophet Muhammad, upon returning from a battle, once made the comment that they had completed the little jihad and now needed to continue with the great jihad. When asked what the latter was, he responded that it was the war against evil within oneself. Struggle for the faith may include its defense when threatened, and then jihad can be “holy war,” much as Captain Moroni’s war in defense of his family, faith, and nation was a holy war. In Islam, if one were to die in a true holy war, that person would go immediately to paradise to await the Resurrection. Unfortunately, the term jihad has been hijacked by Islamic extremists, who have used it as an excuse to entice many into suicide bombings and other acts of violence for political reasons, often killing their own people. In the Hadith, a collection of sayings originating with the Prophet, it is recorded, “It is related from Abdullah bin Omar, ‘The Apostle of God forbade the killing of women and children.’” [5] Unfortunately, it is women and children and other noncombatants that have suffered the most from supposed acts of jihad by Islamic radicals, which places the radicals far beyond the realm of true Islam. It is wrong to paint all of Islam with their brush.

Women

The treatment of women varies across the Islamic world not because the Qur’an is unclear about the place of women but because cultures are hard to change. The Qur’an makes it very clear that men and women are equal before God. Granted, they have their different roles, with the man being the provider and the woman being the one who manages the home and the children, but this does not make them unequal. The roles of the Muslim woman are very much like those of the Latter-day Saint woman. It has been said that Muslim women in the seventh century CE had more rights than did an English woman until late in the nineteenth century. Islam was far ahead of its time. Under the Qur’an, women could own and inherit property, they were to receive the dowry from their husband as an insurance policy against divorce or death, and they could run businesses.

Islam has spread rapidly across the world. Over a billion people accept its message, but sometimes cultures change slowly, and this is especially true of relationships between men and women in cultures that are male-dominated. Women have different roles and privileges dependent upon the country where they live. In Egypt and Jordan, women seem to choose to wear traditional Islamic dress or Western clothing, and sisters may choose differently. In Indonesia, women and men sit in the same college classes, but the women wear the long robe and the traditional head covering. In Saudi Arabia, women are required to wear the traditional robe and head covering and are generally separated from men, but they can become doctors. In Afghanistan, under the Taliban, girls were not permitted to get an education. Turkey is a secular society, and women are not permitted to wear the robes or the head coverings. The treatment of women by men varies just as widely from country to country and often depends on the cultural norms men have learned. In some countries, women are definitely demeaned, but that is not what Islam teaches about their place before God and all others.

Women also play a critical role in religious education. It is the women who teach the children the prayers and Islamic life at home. As noted, women may go to the mosque, and there are certain places in the mosque for them to pray. This is not because they are inferior but because of the positions people take during prayer. A woman in the position of prostration could well be a distraction to a man behind her, so the sexes are separated, much as men and women are separated in the Latter-day Saint temples. The separation prevents distractions. In Islam, female piety is usually expressed and practiced in the home, but women may also visit shrines, where they find socialization with other women as well as a quiet place to express their faith and prayers.

Conclusion

There is much that is common between Islam and The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Both believe in a succession of prophets beginning with Adam, but for Islam, Muhammad is the seal, and therefore the last, of the prophets. Latter-day Saints believe that there is a series of living prophets today, beginning with Joseph Smith and the Restoration. Both are highly ethical and moral faiths. For each, prayer is central to understanding God’s will. Each has a historically rooted tradition that takes persons into God’s presence and allows them to covenant with God that they will change their lives. Both ban alcohol and gambling. Both await Jesus’ return, although Muslims see him as a prophet and Latter-day Saints see him as the Son of God. Both believe in a general Resurrection of the dead, although they differ in whether the end is heaven or hell or whether there are various degrees of glory.

Unfortunately, because of some of the extremists within Islam, the Western press has tended to focus on the negative actions of some Muslims to the almost total exclusion of seeing the enormous good that Islam brings into the lives of average people. Hopefully, some of that good is reflected here.

Notes

[1] “Major Religions of the World Ranked by Number of Adherents,” Adherents.com, last modified August 9, 2007, http://

[2] Daniel C. Peterson, Muhammad: Prophet of God (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2007), 21.

[3] The Holy Qur’an: English Translation of the Meanings and Commentary, rev. and ed. the Presidency of Islamic Researches, IFTA, Call and Guidance (Medinah, Saudi Arabia: The Custodian of The Two Holy Mosques King Fahd Complex for The Printing of The Holy Qur’an).

[4] Peterson, Muhammad, 51.

[5] Robert E. Van Voorst, Anthology of World Scriptures, 6th ed. (Mason, OH: Cengage Learning, 2008), 324.