Christianity

Roger R. Keller, "Christianity," Light and Truth: A Latter-day Saint Guide to World Religions (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2012), 230–67.

As diverse as Christianity is, its central focus is always on Jesus Christ. Every tradition, be it Eastern Orthodox, Roman Catholic, Protestant, or Latter-day Saint, is seeking to explain what it has heard God saying to it through his revelation of himself in Jesus of Nazareth.

Because the aim of this chapter is to deal with certain aspects of the Christian faith that have perhaps not been fully understood by Latter-day Saints, it is a bit different in character from the other chapters. Issues of worship, symbols, and practices are woven throughout the doctrinal sections. There is no section on women because the role of women differs so much within various Christian traditions that there is no way to deal with it in short compass. Given these constraints, I hope that all will better appreciate and understand their Christian neighbors of whatever denomination.

Christianity is the largest religion on the face of the earth, with 2.1 billion adherents, meaning that slightly over one-quarter of all the peoples of the world are Christians. [1] Christianity is very diverse in practice and even in theology. There are common theological threads, however, that run through most Christian denominations, including Latter-day Saints, and it is these that we will explore in this chapter. As we do so, we will hold a dialogue between Latter-day Saint Christians and members of the other denominations within the Christian family. As we carry out this enterprise, we will discover a vast arena of commonality as well as points of difference that exist between Restoration Christianity and the traditional Eastern Orthodox, Roman Catholic, and Protestant forms of Christian belief and practice. Protestants come from various roots, but they are represented by various adherents like Methodists, Presbyterians, Baptists, and Lutherans. The important issue is that all parties to this dialogue be represented properly.

Origins

Christianity is rooted deeply in Judaism. Its founder, Jesus, was a Jew and was a teacher within that context. Some Jews began to see Jesus as the long-awaited Messiah, but they did not fully understand what that meant. For most Jews, the Messiah was to be a king like David who would deliver Israel from her enemies, and in Jesus’ day, the enemy was Rome. Only gradually did Jesus’ followers, or disciples, discover that he was not at all what they had expected. He was the Messiah, who would give his life for the sins of the world, a truth they understood only after his crucifixion and resurrection. That knowledge so altered them that they went out and turned the world upside down with their message that God had come down among human beings in the man Jesus of Nazareth, who was now known as the “Christ,” the Greek word for Messiah. For the current audience, there is no need to explore the particulars of Jesus’ life and ministry, for they are well known. The Christian community continues to this day to try to understand more fully him and his work, and it is to this struggle for understanding that we now turn.

For Christians of the traditional denominations, the source book for their theology is the Bible, which contains the Hebrew scriptures, or what Christians call the Old Testament. In addition, there is the New Testament, which contains the four Gospel accounts of Jesus’ ministry along with the book of Acts, which tells the story of how the early Christian Church spread through the Mediterranean world. Furthermore, there are letters from Paul the Apostle to the Gentiles, as well as other pastoral letters from leaders of the early Christian Church. All this culminates with the book of Revelation, which assures the early Christians that God will conquer all opposition in the end. Catholic Christians, both Roman and Orthodox, include as canonical the Apocrypha, which contains writings from the period between the Old and New Testaments. Latter-day Saint Christians add three other volumes of scripture to their canon (the Book of Mormon, the Doctrine and Covenants, and the Pearl of Great Price).

Image of Christ from Hagia Sophia, Istanbul, Turkey.

Image of Christ from Hagia Sophia, Istanbul, Turkey.

Christian Thought

Jesus and Revelation

I have had both Catholic and Protestant friends tell me that they do not believe in continuing revelation. My usual response is to ask them if they pray, for I am convinced that anyone who prays expects an answer. For Latter-day Saints, that answer is part of what they would call continuing revelation, and when put in those terms, my friends of other Christian traditions readily agree that they too believe God continues to speak to them personally, not only through prayer but also through the Spirit and through the scriptures. They add, however, a caveat that Jesus is THE revelation of God; and if God stood in our midst in the person of the man Jesus of Nazareth, and if scripture bears witness to that one revelation, then there is no more that needs to be said. Nothing can be added to that revelation, for it is complete in and of itself.

Latter-days Saints too hold that THE revelation of God occurred in Jesus Christ, who said that whoever sees him also sees the Father. He is that one glorious revelation of God. Latter-day Saints also say, however, that God continues to tell the human family things about himself, his world, and his church that are not clear or even present either in the self-revelation of God in Christ or in the scriptural witness about him. This too is continuing revelation, but revelation that comes through prophets and apostles, not merely individuals. Thus, Latter-day Saints hold that God has more to say to his church than is contained in any of the canonical texts, and this “more” comes through his living prophet and apostles of the modern church.

Scripture, Tradition, and Creeds

The term Magisterium refers to an authoritative place to which persons can turn for definitive answers on faith and morals. Catholics have this in the pope and the cardinals, who reside in Rome. Latter-day Saints have it in the prophet and apostles. Protestants claim it exists within the pages of the Bible. Because people choose to follow the pope or the prophet, their statements become normative for most Roman Catholics and Latter-day Saints. However, when scripture becomes the only norm, differences exist in how the texts are interpreted, and this has led to a wide variety of denominations in the Protestant world. These denominations often arise from differing interpretations of biblical texts. Given that, there can be no doubt within the Protestant world that “scripture alone” as read with the aid of the Holy Spirit is the source of doctrine and practice.

Roman Catholics, however, add another dimension to their source of theology. It is “tradition.” In John 21:25 it says, “And there are also many other things which Jesus did, the which, if they should be written every one, I suppose that even the world itself could not contain the books that should be written.” Canonical scripture is not the only source of knowledge about Jesus’ works and words. What Jesus said and did was passed to the Apostles, who then passed it on to the church fathers, who passed it to the church. This is “tradition.” Therefore, the Roman Church guided by tradition, not the individual, becomes the authoritative interpreter of the scriptures. The Roman Catholic Church tells its members what they should see in the scriptural witness. Latter-day Saints do something similar. While scripture may be read for personal edification, in the end it is the church leaders, meaning the prophet and apostles, who ultimately tell Latter-day Saints what they should be seeing in the canonical texts.

Creeds also play a major role in Protestant, Roman Catholic, and Eastern Orthodox Christianity. These arise as the result of questions that surface in a church over issues of doctrine. One of the earliest of these was the Apostles’ Creed which states the following:

I believe in God the Father Almighty, Maker of heaven and earth;

And in Jesus Christ His only Son our Lord; Who was conceived by the Holy Ghost; Born of the Virgin Mary; Suffered under Pontius Pilate; Was crucified, dead, and buried; The third day He rose again from the dead; He ascended into heaven; And sitteth on the right hand of God the Father Almighty; From thence He shall come to judge the quick and the dead.

I believe in the Holy Ghost; The Holy catholic church; The communion of Saints; The Forgiveness of sins; The Resurrection of the body; and the Life everlasting. Amen. [2]

This is a good general summary of the Christian gospel. A couple of items should perhaps be clarified for Latter-day Saint readers. Firstly, the Holy Ghost is not the parent of Jesus, but rather the agent of conception. Secondly, the word Catholic means universal and does not mean “Roman Catholic Church”. Thirdly, the “communion of saints” is the Christian Church both visible on earth and invisible on the other side of the veil. After this came other creeds, some of which contain propositions that Latter-day Saints might question from their particular faith perspective. However, the main point is that creeds attempt to answer issues and problems that have arisen in a church by calling councils and having them resolve the problems.

Creeds have often been looked at rather negatively by Latter-day Saints because of what Jesus told Joseph Smith in the First Vision. After he asked his question concerning which church he should join, Joseph says, “I was answered that I must join none of them, for they were all wrong; and the Personage who addressed me said that all their creeds were an abomination in his sight; that those professors were all corrupt; that: ‘they draw near to me with their lips, but their hearts are far from me, they teach for doctrines the commandments of men, having a form of godliness, but they deny the power thereof’ ” (Joseph Smith—History 1:19).

Clearly the Lord did not want Joseph to be in doubt about the churches of his day. There were concerns not only with certain doctrinal issues but especially with the religious climate of Joseph’s day. Their members professed to love the Lord, but when they started going off to different denominations, Joseph reports, “It was seen that the seemingly good feelings of both the priests and the converts were more pretended than real; for a scene of great confusion and bad feeling ensued—priest contending against priest, and convert against convert; so that all their good feelings one for another, if they ever had any, were entirely lost in a strife of words and a contest about opinions” (Joseph Smith—History 1:6). People could not claim to love Jesus and denigrate their denominationally different neighbor. If we love the Lord, we will love our neighbor. Otherwise our “creeds” or professions of faith are a lie.

D&C 10:52–55 (emphasis added) explains the value that the Lord places on churches outside the Latter-day Saint sphere:

And now, behold, according to their [Book of Mormon prophets’ and disciples’] faith in their prayers will I bring this part of my gospel to the knowledge of my people. Behold, I do not bring it to destroy that which they have received, but to build it up.

And for this cause have I said: If this generation harden not their hearts, I will establish my church among them.

Now I do not say this to destroy my church, but I say this to build up my church;

Therefore, whosoever belongeth to my church need not fear, for such shall inherit the kingdom of heaven.

The question here is, “What church is he not going to destroy but rather build up?” This revelation was given in the summer of 1828, almost two years before the establishment of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. In the author’s opinion, the church referred to here was the Christian churches that paved the way for the Restoration and still do. These other Christians are our fellow travelers on our way back to our Heavenly Father. Joseph Smith put this in proper perspective when he said, “[I]f I esteem mankind to be in error shall I bear them down? No! I will lift them up. & [each] in his own way if I cannot persuade him my way is better! & I will ask no man to believe as I do. Do you believe in Jesus Christ &c? So do I. Christians should cultivate the friendship with others & will do it.” [3]

God works in many ways and through many channels. If persons find God in different ways than we do, we should, according to Joseph, support them in that faith and help them grow spiritually in their own way—be that through the Latter-day Saint way, the Presbyterian way, or the Baptist way.

The Trinity

As we approach the doctrine of the Trinity, we should be aware that any competent Catholic or Protestant theologian will say that this is the mystery of God and cannot be fully understood. It can only be accepted, because it is ultimately beyond human understanding. Having said this, part of the definition of the Trinity is very straightforward. It simply says that there are three simultaneously coexisting persons in the Godhead, a statement with which Latter-day Saints should have no trouble. The most obvious difference between the traditional Christian view and that of Latter-day Saint Christians is that the Father is embodied. There is full equality between the three members of the Godhead in traditional Christian thought while there is a slight subordination of the Son and the Holy Ghost before the Father in Latter-day Saint thought. Eastern Orthodoxy also has a sense of this subordination with which Latter-day Saints would feel at home.

When the Son becomes incarnate in Trinitarian thought, the Godhead merely stretches. All three members are still fully God, but the Son is embodied, having taken on human life. The same holds true for Latter-day Saints, but there are two embodied beings in the Godhead.

Latter-day Saints often like to ask persons who believe in the doctrine of the Trinity who the Son was praying to in the Garden of Gethsemane. For a person who understands the Trinitarian doctrine, that is a nonsensical question, for they know well the passage at the beginning of Matthew which states that Jesus was in the water, the Father’s voice spoke from heaven, and the Spirit descended as a dove. The Son was praying to his Father in Gethsemane regardless of whether one is a Trinitarian or a Latter-day Saint.

There are, however, people known as “modalists,” who hold that there is one God who wears different masks. Sometimes he wears the mask of the Father, but when he does, the Son and the Holy Spirit do not exist. Likewise, when he wears the mask of the Son, the Father and the Holy Ghost do not exist. Thus, the question, “Who was the Son praying to in the Garden?” makes perfect for modalist position because the answer is no one. Nobody is out there. All too often many Christians hold the modalist view when they think they are articulating the doctrine of the Trinity, but that view was declared a heresy in the third or fourth century CE.

What happens when the Son ascends to the presence of the Father? The Son is a fully embodied resurrected person who is wholly God and wholly human in both traditional and Latter-day Saint Christianity.

Whether before, during, or after the incarnation, there are always three simultaneously coexisting persons in the Godhead, whether one is a traditional Christian or a Latter-day Saint Christian. So the issue is not whether there are three persons in the Godhead. There are. This is the doctrine not of the “One-nity” but of the “Tri-nity.” Rather, the real issue between traditional Christians and Latter-day Saint Christians is the question, “How are they one?”

For traditional Christians, they are one in “essence” or “nature,” and as we have already seen competent theologians say, this is ultimately inexplicable and is the mystery of God. They just accept the doctrine. Latter-day Saint Christians, however, see the oneness as a unity of love, will, purpose, and action. Interestingly, the New Testament talks only about what the three members of the Godhead do. It is not until the Christian message moves out into the Greek influenced world that the question switches to, “What is the Godhead like?” It is at that point that the philosophical answer of the “one essence” is put forward and accepted at the Council of Nicaea in 325 CE.

But how did we get to the point of viewing the Godhead through the “one essence” lens? It was because the church was trying to hold two things together that did not necessarily have to be held together. The Old Testament tells us there is one God. In the New Testament, we find three persons—Father, Son, and Holy Ghost—who are recognized as divine. How can both be true? The traditional answer was and is that the one God had three persons within him who were composed of one divine essence.

Is there a possibility, however, that in the New Testament one might learn something new? Regardless of whether persons are traditional Christians or Latter-day Saint Christians, in the incarnation of the second person of the Godhead, we learn something we did not know before. Traditional Christians learn that the God of the Old Testament, whom they know as Jehovah, has a Son—Jesus. Latter-day Saint Christians learn that when Jehovah, the God of the Old Testament, becomes incarnate as Jesus, he reveals that he has a Father. In either case, we know something that we did not know before. We learn that there are actually three members of the Godhead—Father and Son and Holy Ghost.

Latter-day Saint Christianity has additional information beyond that supplied in the Old and New Testaments. They root their knowledge of the nature of God in Joseph Smith’s First Vision, in which the Father and the Son together appeared to Joseph, thereby negating in the minds of Latter-day Saints the doctrine of God being one inexplicable mystical essence of three persons. There are simply three distinct persons bound together in love, will, and purpose.

The Fall

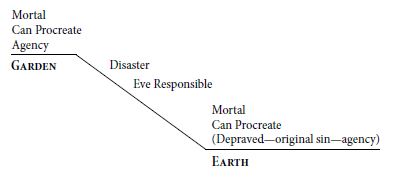

The doctrine of the Fall is pivotal theologically for both traditional Christians and Latter-day Saint Christians, but both understand it in quite different terms. Therefore, we will contrast the approaches. In traditional Christian thought, God places Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden, where they are mortal, fully able to procreate, and have agency, and where they are to live until they die to be immediately resurrected. The garden is viewed much as Latter-day Saints view the Millennium, in which people will be born, live to a certain age, die, and in the twinkling of an eye be resurrected. In traditional thought, Eve chose to try to become like God, therefore causing her and Adam to be ejected from the garden to the earth where they were still mortal, could still procreate, and may or may not have agency, dependent upon the particular denomination which one consults. Some persons would hold that Adam and Eve, and thus we, are so fallen that we have no ability to respond to God, and therefore God does everything, if we are to be redeemed (Calvinist traditions). Others hold that we have contracted original sin (usually pride) from Adam and Eve, which must be removed before we can make choices (Roman Catholic). Others would say that although fallen, people still have their agency, and Eastern Orthodox, Methodists, and Latter-day Saints would fall into this category. We can schematize the traditional view of the Fall as follows:

In this scenario, the Fall is a disaster, and Eve is the one who caused it. Granted, Adam followed along, but Eve was the real culprit.

In Latter-day Saint thought, in Moses 2:27–28 we see that God in the premortal existence created male and female in his image and then commanded them to “be fruitful, and multiply, and replenish the earth.” Immediately there is a tension between the coming garden and earth, for we know that Adam and Eve are not intended to live in the garden but rather on the earth, which they are to replenish. God, however, places them in the garden, where they are immortal and cannot procreate but do have agency. Then he gives them a command that too often is considered to be a contradictory command to the first. That command is, “And I, the Lord God, commanded the man, saying: Of every tree of the garden thou mayest freely eat, but of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, thou shalt not eat of it, nevertheless, thou mayest choose for thyself, for it is given unto thee; but, remember that I forbid it, for in the day thou eatest thereof thou shalt surely die” (Moses 3:16–17; emphasis added).

The problem with considering this a contradictory command is that God does not give contradictory commands, so something else must be happening here. In law, there is moral law and statutory law. The first implies that something is inherently wrong, while the second establishes a standard for a particular place and time. For example, a statutory law is one that a city might institute, like defining a speed limit on a main street. If persons violate this, they have broken not a moral law but simply a law established by a particular municipality for that particular street. This is the kind of law given to Adam and Eve in the garden when they are told not to eat of the tree of knowledge. [4] In reality, God is giving them information, and note that they may choose for themselves. There are definitely consequences if they choose to partake of the fruit, but still they may choose. To put this in colloquial language, God is saying to them something like, “If you want to stay comfortable and unchallenged here in the garden, don’t eat of that tree over there. But if you want to grow, you are going to have to do what I told you in the premortal life and go out and replenish the earth. It is up to you.” At this point, Satan appears on the scene. In reality, he is the tragic/

[Adam said,] Blessed be the name of God, for because of my transgression my eyes are opened, and in this life I shall have joy, and again in the flesh I shall see God.

And Eve, his wife, heard all these things and was glad, saying: Were it not for our transgression we never should have had seed, and never should have known good and evil, and the joy of our redemption, and the eternal life which God giveth unto all the obedient. (Moses 5:10–11; emphasis added)

Both rejoiced in the choice they had made to leave the garden, but Eve subtly reminded Adam by saying “our” transgression, that he would have remained in the garden had it not been for her insight. Thus, by their choice, Adam and Eve opened the future for the entire human family. For Latter-day Saints, the Fall is a fortunate Fall, and Eve is the heroine of the story. Schematically, the Fall looks like this:

Here the tension between the garden and the earth is clear. The Garden is a temporary stopping point for Adam and Eve which enables them to make their own choices concerning their willingness to confront the trials of earth life and ultimately death. In this case, the Fall is upward—a fortunate Fall—and Eve is the heroine. She opens the door to eternal progression for the human family by her choice!

The Atonement of Jesus Christ

For all Christians, the Atonement is the antidote God provides for the effects of the Fall. Not all agree on how it works because in truth, that is a mystery. However, no active Christian doubts that the Atonement has rebuilt the bridge to God that was broken in the Fall.

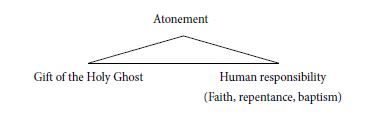

There is a debate among Christians, however, whether the Atonement is “unconditional,” meaning that one gets the effects of it whether or not one wants them; or whether it is “conditional,” meaning that one has to do something for the effects to take place. As we will see below, Latter-day Saints believe that both concepts hold, and so we will examine this doctrine by looking at the Latter-day Saint perspective and comparing that to the traditional models of the Atonement.

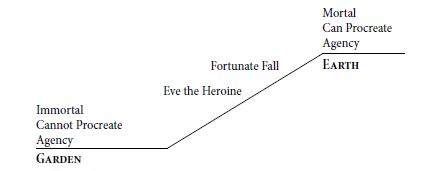

Unconditional effects

According to Latter-day Saint thought, the Atonement covers unconditionally the effects of the Fall brought about by Adam and Eve’s choice to leave the Garden. By this choice, Adam and Eve blessed the human race unconditionally with two things—temporal death and spiritual death. The latter means that from the time of the Fall, the human family has been separated from the Father and has experienced God’s workings through the Son (Jehovah) and the Holy Ghost. The question is whether either of these effects is broken unconditionally by the Atonement; of course, the answer is yes. Christ’s Resurrection ensures that the entire human race will be resurrected due to his victory over death. But what about our separation from God? Will we all unconditionally return to his presence? I often get a mixed answer to that question when I ask it in class, but there are two things to be considered here. The first is the second article of faith (emphasis added): “We believe that men will be punished for their own sins, and not for Adam’s transgression.” If all the human family is not returned to God’s presence, then at least some persons are suffering for something they did not do themselves. This runs contrary to the second article of faith. Secondly, we need to consider Alma 11:44:

Now, this restoration shall come to all, both old and young, both bond and free, both male and female, both the wicked and the righteous; and even there shall not so much as a hair of their heads be lost; but every thing shall be restored to its perfect frame, as it is now, or in the body, and shall be brought and be arraigned before the bar of Christ the Son, and God the Father, and the Holy Spirit, which is one Eternal God, to be judged according to their works, whether they be good or whether they be evil.

The scriptures teach that because of the unconditional effects of the Atonement, all persons return to the presence of the resurrected Lord to be judged. This author believes, based on Alma 11:44, that all members of the Godhead will be at the judgment bar, with the Son judging on behalf of them all. The unconditional effects of the Atonement may be diagrammed as follows.

The question now is whether, once in the presence of the God, persons get to stay there. That will depend on their relationship with Christ, because what is not covered in the unconditional effects of the Atonement are persons’ individual sins. These have nothing to do with Adam and Eve but are the sins we have committed ourselves. These sins are removed by the conditional aspects of the Atonement: “if…”! And what is the “if”? It refers to whether we have let Christ have our sins or whether we are still carrying them.

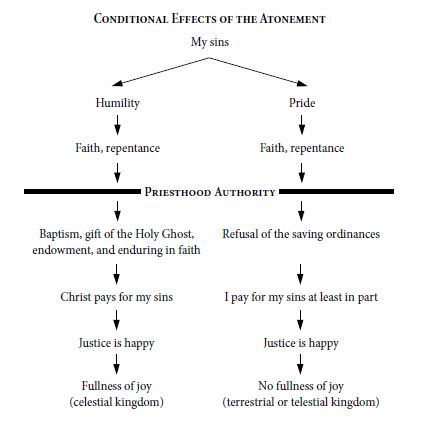

Conditional effects arising from humility

The only thing that can save us from our sins is the Atonement of Jesus Christ meaning his suffering, death, and Resurrection. Nothing in this world or any other world can do this for us. Hence, the question becomes, how do we access the power of the Atonement? The simple answer is that we do things God’s way, which requires that we stand in humility before him. If we do, we will permit Jesus Christ to encounter or meet us. This is what faith is all about. Faith is a relationship—a relationship or encounter with Jesus—just like marriage is a relationship between a man and a woman. When we meet Christ, he holds up a mirror to us, and we see ourselves as we truly are (sinners in need of repentance and a Savior). Isaiah realized this when he encountered Jehovah in the temple in Isaiah 6. His first reaction was not, “Wow, I’ve seen God,” but rather, “Woe is me! for I am undone; because I am a man of unclean lips, and I dwell in the midst of a people of unclean lips: for mine eyes have seen the King, the Lord of hosts” (Isaiah 6:5). Even the great Isaiah saw himself for what he was when confronted with his Lord and God. So it was with Peter, who met the same person, but in his case, it was the incarnate Jehovah—Jesus. In Luke 5 we read about a great catch of fish that had occurred at Jesus’ direction. “When Simon Peter saw it, he fell down at Jesus’ knees, saying, Depart from me; for I am a sinful man, O Lord” (Luke 5:8). In the cases of both Isaiah and Peter, the relationship or encounter with the Lord led to a realization of how far they were from being what he would have them be. That is why faith is the first principle of the gospel. Without an encounter with Jesus, we do not know who we are, and we do not know that we need to change. We can open ourselves to such an encounter by reading the four Gospels, the Book of Mormon, and other scriptures prayerfully and by attending the temple, thereby letting the Spirit direct us to Jesus.

Meeting Jesus leads to the second principle of the gospel—repentance. We realize our need to change. This is the experience of all Christians, be they traditional Christians or Latter-day Saint Christians. At this point, most traditional Christians would say that they have done what God has asked of them to make use of the Atonement of Jesus Christ. They have faith, have repented of their sins, and now intend to lead a disciple’s life. Latter-day Saints, however, believe that God has given them additional ways to access the Atonement, and this is what separates them from Christians of all other traditions. Latter-day Saints hold that there are required sacramental acts or ordinances administered by the Latter-day Saint priesthood which God asks of them if they are serious about coming fully to Christ. Following faith and repentance, Latter-day Saints understand baptism to be a required saving ordinance that opens the way for return to the presence of God. It must be by full immersion and administered by an authorized person holding the priesthood of God. It is viewed as so essential that it is done in the temples of the church by proxy for those who are dead and who had not been baptized by priesthood authority.

There is a passage in the Book of Mormon that says, “For we know that it is by grace that we are saved, after all we can do” (2 Nephi 25:23). The problem with this statement is that too many Latter-day Saints wonder what they have to do or how many laws they have to keep before grace begins. Latter-day Saints believe, as do Eastern Orthodox Christians, that human beings are expected to make a contribution toward their salvation, since the Fall never destroyed their agency. But contribute what and how much? The answer is that humans are asked to contribute the first three principles of the gospel: faith in Jesus Christ, repentance, and submission to baptism. If they do that, they are in the kingdom of God, as Stephen E. Robinson says. [5] To prove this, God gives each person a gift—the gift of the Holy Ghost through the laying on of hands by priesthood holders. This does not mean that one has reached perfection or that the Holy Ghost will not push us to grow, but it does mean that if the Spirit is in our lives, we can be assured that we stand approved before God, for we stand before him, clothed in Christ. Below is a diagram showing the relationship between our human responsibility, the gift of the Holy Ghost, and the Atonement.

Many Christians hold that humans are so warped by the Fall that they are incapable of responding to God, and therefore God has to do everything. There can be no human responsibility or cooperation with God. Some Latter-day Saints, on the other hand, believe they have to do it all. From this author’s perspective, both of these positions are wrong. Latter-day Saints are expected by God to contribute their faith in Christ and repent and submit to baptism. That is their contribution. God then gives them the gift of the Holy Ghost, which makes the Atonement present every day of their lives, for we all need it daily because we still sin. In addition to being a witness of God’s approval of us, the Holy Ghost is also the power pack that enables us to live the life of a disciple that God asks of us. Our works flow out of our relationship with Jesus. Works do not create a relationship with Jesus because Jesus comes to us first.

In addition to the ordinances of baptism and the gift of the Holy Ghost, Latter-day Saints believe they have access to other saving ordinances in the temple, such as the washings and anointings, the endowment, and the sealing ordinances. All of these—faith in Christ, repentance, baptism (renewed weekly by the sacrament, or “Lord’s Supper”), the gift of the Holy Ghost, and temple ordinances—are channels of grace which attach persons to the Atonement and Resurrection of Jesus Christ.

In all these things, Latter-day Saints are admonished to “endure to the end,” a phrase found often in the Book of Mormon. But endure in what? In four places in the Doctrine and Covenants, this question is answered. [6] We are to “endure in faith” to the end, and this drives us daily back to the first principles and ordinances of the gospel: faith in Christ, repentance, baptism (or sacrament), and the gift of the Holy Ghost. We are not just to “hang in there” but rather are to “hang on to Christ in faith.”

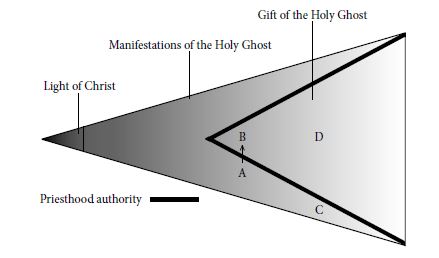

What about Christians who are not Latter-day Saints? Can they, as a response to their faith and repentance, have the Holy Ghost in their lives? Most assuredly, for the Holy Ghost that my wife and I knew before we were Latter-day Saints is the same Holy Ghost that we know as Latter-day Saints. There is a spectrum of divine power that influences the human family beginning with the Light of Christ, which is then followed by manifestations of the Holy Ghost, which are available to persons of any faith, and then culminates in the gift of the Holy Ghost, which is available to Latter-day Saints. [7]

The Light of Christ is something that everyone brings into the world with him or her, and it gives each individual a basic moral guideline for which each is accountable. Many have called it the “conscience.” There is little real doctrinal content in the Light of Christ. If that is desired, then persons have to let the Holy Ghost into their lives, and when they do, they receive manifestations of the Holy Ghost, which may be sporadic or virtually constant, depending on their spiritual maturity. However, to have the gift of the Holy Ghost, which leads to all that God has in store for his family, one must receive it from authorized Priesthood holders. As a convert, I know that the experiences of manifestations of the Holy Ghost and the gift of the Holy Ghost feel the same because the source is the same Holy Ghost. But the meaning is radically different, for manifestations are available to anyone of any faith who seeks God’s will for them. The gift of the Holy Ghost, however, comes only in response to the prior priesthood ordinance of baptism, thus being available, from a Latter-day Saint perspective, only to those who have submitted themselves to the priesthood of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. We might draw the divine influence as follows:

Note that when one crosses the priesthood line from manifestations to gifts (A to B), persons do not get more of the Holy Ghost. Rather, they move into a realm where they can receive the saving ordinances of the gospel, and it is the issue of priesthood authority that separates Latter-day Saint Christians from Christians of other traditions. Similarly, persons like John Wesley, Mother Teresa, or Mahatma Gandhi may have lived so closely to God that they may have had manifestations of the Holy Ghost virtually constantly (C), similar to the Holy Ghost’s influence on the most spiritually advanced Latter-day Saints (D). The latter, however, have access to the saving ordinances of the gospel, which may not be accessible to the others until they pass through the veil. There is little doubt, however, that great souls like the ones mentioned above will accept the ordinances done for them by proxy.

Turning back a bit and remembering that the only thing that saves us from our sins is Jesus’ Atonement, what are the roles of faith in Christ, repentance, baptism, the gift of the Holy Ghost, and the ordinances of the temple? Once again, they are the channels of grace that tie us into Christ’s Atonement. These are the places where God has assured us that we can meet him in Jesus Christ and the Holy Ghost and where we can find the cleansing power of Jesus that sets us free from our sins.

The question now is whether justice is happy, for mercy cannot rob justice. But justice does not care who pays for our sins. It just must be paid because God’s commandments cannot be broken without payment. If Jesus pays for my sins, that is fine, just as it is fine if I wish to pay for them. Since Jesus pays the price, mercy has not robbed justice, and justice is happy with the payment. This enables persons who have walked God’s path to receive the fullness of joy, or what Latter-day Saints term “the celestial kingdom.”

Conditional effects arising from pride

The alternative to standing before God in humility is to stand in pride. We will do things our way instead of God’s way. What would the consequences of this decision be? First, even though persons may have faith in Jesus Christ and have repented of their sins, they will limit the number of channels of grace that are operative to acquire the full benefits of the Atonement. They will turn away from the need for saving ordinances, thereby requiring that they pay at least part of the price for their sins. As long as they refuse the saving ordinances, they will continue to separate themselves from God’s path. Justice will be happy because those who refuse the saving ordinances will be paying the price for their decisions. The fullness of joy, however, will not be open to them. Instead, they will receive a lesser joy defined by Latter-day Saints as terrestrial or telestial glory. The effects of standing before God with either humility or pride can be diagrammed as below:

Note that the horizontal line is priesthood authority. Most Christians hold that faith and repentance are all that God asks of us, but Latter-day Saint Christians affirm that saving ordinances administered by the priesthood are required to demonstrate to God that we will do things his way.

Sacraments

Sacraments are events within a church where people encounter God through Jesus Christ and the Holy Ghost. Both the Roman Catholic Church and the Eastern Orthodox Church have seven sacraments. As we discuss these, we will note where these two traditions differ from one another.

Sacraments of Initiation

Baptism

Baptism is the sacrament of initiation into a Christian church. In Roman Catholicism, baptism removes original sin, enabling persons to begin with a clean slate and to be responsible for the decisions they make. According to Timothy Ware, “Most Orthodox theologians reject the idea of ‘original guilt’ [or sin]. . . . Humans (Orthodox usually teach) automatically inherit Adam’s corruption and mortality, but not his guilt.” [8] So there is nothing of which a person needs to be cleansed except the sins they themselves have committed. In both Roman Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy, infants are baptized, but the Orthodox practice signifies God’s claim on the child before the infant is aware of God and has nothing to do with original sin, although there is a concept of “emergency baptism” which seems to create a middle position. In Orthodoxy, infant baptism would be similar to the Latter-day Saint practice of blessing an infant shortly after birth. Roman Catholic baptism is usually done by pouring water on an infant’s head three times, while in Orthodox traditions, the child is fully immersed three times, symbolizing a mystical burial and resurrection with Christ. Both baptisms are done in the name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost. Because baptism marks the soul, it is a non-repeatable sacrament in both traditions.

Orthodox infant baptism by immersion. Courtesy of Shustov.

Orthodox infant baptism by immersion. Courtesy of Shustov.

Among Protestants, baptism is one of the two sacraments they celebrate. It may be done in a variety of ways from full immersion of a believing adult to sprinkling an infant. Latter-day Saint baptism is a “believer baptism” normally done at the age of eight by complete immersion under the hands of a priesthood holder.

Confirmation or chrismation

In the Roman Catholic Church, confirmation is when young persons confirm their faith for themselves and become full, active members of that church. They are confirmed by a bishop through the laying on of hands for the gift of the Holy Ghost. Since Catholics normally baptize infants, confirmation occurs quite a bit later, usually when a young person is between the ages of twelve and fifteen. Like baptism, this sacrament marks the soul, so it is non-repeatable.

Among Orthodox Christians, baptism and chrismation (their word for confirmation) are done one right after the other. This is the time when a person, even an infant, receives the gift of the Holy Ghost, becomes a full member of the people of God, becomes a prophet, and receives a share in Christ’s royal priesthood. The ritual is carried out with an oil called chrism, which is administered to various parts of the body with the sign of the cross (to the forehead, eyes, nostrils, mouth, ears, breast, hands, and feet) while the priest says, “The Seal of the gift of the Holy Spirit.” Endowed members of the Latter-day Saint community will recognize that there are similarities between the Orthodox chrismation and the washings and anointings which take place in the Latter-day Saint temples. Chrismation is the sacrament of reconciliation for Eastern Orthodox Christians when a member has left the church or been excommunicated.

Among Latter-day Saints, baptism and confirmation take place in close proximity to one another, often on the same day. The confirmation is done by a holder of the Melchizedek Priesthood who lays his hands on the head of the newly baptized member and commands him or her to receive the Holy Ghost and then gives a blessing. Should a Latter-day Saint be excommunicated, he or she would need to be re-baptized and reconfirmed.

Eucharist

In the Roman Catholic Church, the normal order of initiatory sacraments for new adult members would be baptism, then confirmation, followed by the Eucharist, which is what Latter-day Saints call “the sacrament.” It is the celebration of the Lord’s Supper. Because there is, however, such a gap in time between baptism and confirmation in the Roman Catholic Church, young people born in the Church will first take communion when they are seven or eight. In Eastern Orthodoxy, the Eucharist is received even by infants. Among Latter-day Saints, quite young children, at the discretion of parents, receive the bread and water of the sacrament. In all traditions, this is a repeatable sacrament, and the one through which people most often encounter Christ. The Eucharist, or Holy Communion, is also the second sacrament accepted by Protestants. For Protestants, a sacrament must have been either administered to Jesus (baptism) or initiated by him (the Lord’s Supper, or communion). Thus, there are only two sacraments in Protestantism.

Sacraments of Healing

Penance and reconciliation

This sacrament in Roman Catholicism is often known as “confession,” but that is only a part of penance. Penance begins with a deep self-examination both spiritually and behaviorally. One then goes to the confessional, which traditionally has permitted the penitent to be anonymous, although recently confession has been face to face with the priest. This can lead to follow-up and pastoral care, which has always been the practice in Eastern Orthodoxy. Once in the confessional, penitents tell the priest how long it has been since their last confession and whether it was a “good confession,” meaning, did they say what they should have said, and did they mean it? Too often people view Catholic confession as an act that just wipes away sins without any real need for change. This is absolutely not true, any more than Latter-day Saint youths can “sow their wild oats,” confess to the bishop, and automatically go on their missions. Following the confession, the priest will give the person penance to perform and then pronounce an absolution for their sins. The latter is effective only if the penance is performed with faithfulness and true repentance. For example, if a person were to confess to theft, the penance might be to make restitution and to turn himself or herself in to the authorities. However, if the penitent is an eight-year-old who confesses to bullying his sister, the priest might tell him to stop the practice and to say two “Our Fathers” (the Lord’s Prayer) or three “Hail Marys.” Since Mary is the mother of Jesus, many Catholics ask her to intercede for them with her son, and the Hail Mary expresses that wish.

Hail Mary,

Full of Grace,

The Lord is with thee.

Blessed art thou among women,

and blessed is the fruit

of thy womb, Jesus.

Holy Mary,

Mother of God,

pray for us sinners now,

and at the hour of death.

Amen.

It should be noted here that confession is the sacrament of reconciliation in the Roman Catholic Church if a person has been excommunicated. Confession in the Eastern Orthodox tradition has always been face-to-face with the priest, as stated above. The confession is actually given to God with the priest as a witness. At the end of it, the Orthodox priest will give a penance and absolution, but he also has always had the ability to give pastoral care and follow-up with his parishioners because he knows their struggles.

Anointing

Anointing is the second sacrament of healing and deals with both the physical and spiritual dimensions of human life. In past years, anointing in Roman Catholicism was used primarily at the time of death. Since the Second Vatican Council (1962–65), it has been used much as Latter-day Saints use the ordinance of anointing. It is a sacrament to bring about healing and is carried out by anointing with consecrated oil, usually once per illness. But as Eastern Orthodoxy stresses, it may have two faces—one toward health and healing and the other toward release and death.

Sacraments in the Service of the Community

Holy Orders

Taking Holy Orders means that a man or woman has taken the religious life as a full-time vocation. Women can become nuns, and men can become brothers (lay members of a religious order) or priests or both. Taking Holy Orders involves vows of celibacy, obedience, and possibly poverty. Like baptism and confirmation, assumption of these roles marks the soul, and a person wishing to be freed from Holy Orders usually has to be released by Rome. Clearly, those assuming Holy Orders serve the Roman Catholic Church by being able, as unmarried persons, to go where they are needed and to do what they are asked to do by their superiors.

Major orders are bishops, priests, and deacons in both Roman Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy. Bishops ordain people to all of the above offices. The primary difference between Roman Catholicism and Orthodoxy is that priests in the latter tradition may be either married or unmarried and celibate. If one chooses to be married clergy, the choice and the marriage must take place before ordination. If a spouse dies, the priest is not permitted to remarry. Bishops are celibate and must be drawn from the unmarried clergy. Vatican II in the Roman Catholic Church (1962–65) declared Holy Orders and marriage to be equally valid vocations, and since that time, the recruitment of priests and nuns has been more difficult.

Marriage

Marriage serves the Catholic community by providing new members raised in strong Catholic families. The soul is also marked by marriage, and this is one of the reasons that divorce is not permitted in the Roman Catholic Church, in addition to Jesus’ statement that what God has joined together, no one should put asunder.

Eastern Orthodoxy holds marriage in high esteem. Human beings are meant to live in relationships unless God gives someone the special grace of living a celibate life. However, divorce is permitted, and Eastern Orthodoxy recognizes that sometimes, though sad, it is healthier for a couple to separate than to stay together. In Roman Catholicism, in Eastern Orthodoxy, and among Latter-day Saints, sexual relations should exist only within marriage. In Roman Catholicism, use of contraception is banned, since sexual relations are for bringing children into the world. Eastern Orthodoxy, however, permits the use of artificial birth control methods, as do Latter-day Saints, since sexual relations also bind couples together in a special, intimate way. All traditions condemn abortions.

Having looked at the seven sacraments of the Catholic communion and the two sacraments of the Protestant churches, it is clear that Latter-day Saints are far more like the Catholics sacramentally than they are like Protestants, as the following chart shows.

Catholics Sacraments Baptism Confirmation or chrismation Eucharist Penance Anointing Holy Orders Marriage | Latter-day Saints Ordinances Baptism Confirmation “The sacrament” (Not an ordinance) Anointing Ordination to the priesthood Marriage |

Latter-day Saints are a very ordinance-oriented church. In the ordinances, people meet Christ in special ways, and this becomes true also with the ordinances of the temple. In actuality, Latter-day Saints have more ordinances than Catholics do sacraments.

The Mass

To many who are not Catholic, the Mass is a bit of a mystery because they do not know what is transpiring, even though the service is now in the language of the people rather than in Latin. Sadly, this lack of understanding prevents non-Catholics from appreciating the beauty and spiritual power of the Mass. Yet, anyone who has sung in a high school or university choir more than likely has sung portions of the Mass, if not a full Mass. Here we will look at the portions of the mass that are used every Sunday in the Roman Catholic Church and which are the clothesline on which other elements of the worship service are hung, such as hymns, prayers, scripture readings, and sermons. The Greek and Latin words will be used for their titles, and then these will be translated, since most people have probably sung the Mass in its original languages.

Kyrie (Lord)

Lord, have mercy.

Christ, have mercy.

Lord, have mercy.

The Kyrie is the beginning of the mass. The worshipers come as sinners in need of forgiveness, and they come calling on the one, Christ, who can forgive.

Gloria (Glory)

Glory to God in the highest,

and peace to his people on earth.

Lord God, heavenly King,

almighty God and Father,

we worship you, we give you thanks,

we praise you for your glory.

Lord Jesus Christ, only Son of the Father,

Lord God, Lamb of God,

you take away the sin of the world:

have mercy on us;

you are seated at the right hand of the Father:

receive our prayer.

For you alone are the Holy One,

you alone are the Lord,

you alone are the Most High,

Jesus Christ,

with the Holy spirit,

in the glory of God the Father. Amen.

This next element of the mass is an act of praise. It begins with the words the angels sang at the time of Jesus’ birth and then continues with acts of praise to all three members of the Godhead. The central figure, however, is Jesus Christ, the Lamb of God, the one who can have mercy, the one who takes away the sins of the world and thus the sins of the worshipers.

Credo (We believe)

We believe in one God,

the Father, the almighty,

maker of heaven and earth,

of all that is seen and unseen.

We believe in one Lord, Jesus Christ,

The only Son of God, eternally begotten of the Father,

God from God, Light from Light,

true God from true God,

begotten, not made, one in Being with the Father.

Through him all things were made.

For us men and for our salvation

he came down from heaven:

by the power of the Holy Spirit

he was born of the Virgin Mary, and became man.

For our sake he was crucified under Pontius Pilate;

he suffered, died, and was buried.

On the third day he rose again

in the fulfillment of the Scriptures;

he ascended into heaven

and is seated at the right hand of the Father.

He will come again in glory to judge the living and the dead,

and his kingdom will have no end.

We believe in the Holy Spirit, the Lord, the giver of life,

who proceeds from the Father and the Son.

With the Father and the Son he is worshiped and glorified.

He has spoken through the Prophets.

We believe in one holy catholic and apostolic Church.

We acknowledge one baptism for the forgiveness of sins.

We look for the resurrection of the dead,

and the life of the world to come. Amen.

This is the Nicene Creed which is used in worship services around the world in both Catholic and Protestant churches. This third element of the mass is a statement of the worshipers’ beliefs and sketches the broad outlines of Christian doctrine. Note that it is divided into three sections, the first dealing with the Father and his work, the second with Jesus’ work, and the last with the work of the Holy Spirit, or Holy Ghost. Most of the creed could be said by Latter-day Saint Christians, but with reservations concerning certain statements about the Son, particularly the phrase “one in Being with the Father.” There might also be some question about the word “catholic,” but we should remember that it simply means “universal.” Further, Latter-day Saints would be concerned about how the apostolic authority is passed from one generation to the next, as would a Roman Catholic, an Eastern Orthodox, an Anglican, a Presbyterian, or a Methodist. Thus, having come as sinners in need of help, having praised the members of the Godhead who can and do help, the worshipers through the creed now say what they believe.

Sanctus (Holy)

Holy, Holy, Holy Lord, God of power and might,

heaven and earth are full of your glory.

Hosanna in the highest.

Blessed is he who comes in the name of the Lord.

Hosanna in the highest.

The fourth element of the Mass is again an act of praise with Christ at its center. The first part of the Sanctus comes from Isaiah 6 as Isaiah encounters Jehovah in the temple and the seraphim say the first two lines to one another. The Hosanna portion of this is taken from Psalm 118:25–26 and are the words the crowds shouted as Jesus entered Jerusalem on the Sunday before his crucifixion. Thus, we have two Old Testament passages used in praise of Jesus.

At this point, the Mass transitions into the portion focused on the Eucharist. There are several prayers, all of which stress Christ’s victory over death and his future coming in glory. Just prior to the taking of the Eucharist, the final piece of the Mass is said or sung.

Agnus Dei (Lamb of God)

Lamb of God, you take away the sins of the world:

have mercy on us.

Lamb of God, you take away the sins of the world:

have mercy on us.

Lamb of God, you take away the sins of the world:

grant us peace.

Essentially, the Agnus Dei (Lamb of God) is a prayer directed to Jesus Christ, who does in fact remove sin and thereby grants peace to those who come to him.

Items used during the Eucharist. Copyright Jorge Royan, http://

Items used during the Eucharist. Copyright Jorge Royan, http://

Eucharist

The Eucharist, or Holy Communion, is the culminating act of the Mass. Catholics believe that the bread and the wine literally become the body and blood of Christ, based on Christ’s statements at the Last Supper that “this is my body” and “this is my blood.” Thus, when Catholics take the bread and the wine, they have truly come into the presence of Christ and participate in the sacrifice that removes their sins. For Latter-day Saints, Christ is also present in the elements of the sacrament, but he is present spiritually. When Latter-day Saints take the bread and water, they take Christ upon themselves and thereby are momentarily as clean and pure as they were on the day of their baptism. Very quickly this cleanliness is marred by sinful thoughts, words, or actions, but the communicant was clean momentarily because of Christ’s presence.

Looking back, let us see the path we have traveled in the Mass. The participants begin with a statement of their need for Christ because of their sin (Kyrie). Next, they praise the members of the Godhead, but with special reference to Christ, who removes sin (Gloria). They then together profess their faith in the work of the members of the Godhead, once again with special emphasis on the work of Jesus (Credo). Another act of praise occurs (Sanctus) with Christ as the focal point. Just prior to taking the Eucharist, Christ is petitioned to remove the sins of the worshipers’ and to give them peace (Agnus Dei). The worshipers then enter the presence of Christ as they partake of the Eucharist. Theologically, this sequence makes great sense and is beautifully augmented with the other changeable elements of the Mass. In reality, the Mass shares a parallel with the endowment ceremony, in which persons move progressively toward the presence of God, which is finally realized in the celestial room of the temple.

Mary

Mary holds a very high place in Roman Catholicism, and there are four doctrines that are useful to understand. Because Mary is Jesus’ mother, Roman Catholics believe that she can intercede in a special way with her son on their behalf. Thus, she is chief of the saints, and the following doctrines have risen around her as the Roman Catholic church has contemplated her place in God’s work. Latter-day Saints have one doctrine comparable to these.

Immaculate conception

This is a doctrine about Mary, not about Jesus. Roman Catholics believe that all human beings inherit original sin from Adam, and that would include Mary. If, however, Mary is to be a pure vessel that would not pass such sin on to Jesus, thereby making him unfit to be the perfect sacrifice that he had to be, her original sin had to be removed. According to this doctrine, that is precisely what happened. At the moment of Mary’s conception in the womb of her mother, Anna, Jesus applied the Atonement to her, thereby enabling her to be born without sin. She was, therefore, a pure vessel into which Jesus could enter.

Virgin birth

The doctrine of the virgin birth states that Mary conceived through the power of the Holy Ghost. This does not make the Spirit the parent of Jesus, but rather it is just the agent of conception while the Father is the parent. This is the doctrine that Latter-day Saints share in common with Roman Catholics, for this is what both Luke 1 and Alma 7 affirm.

Perpetual virginity

Not only do Catholics believe that Mary was a virgin when she conceived, but they also believe that she remained a virgin for the rest of her life. Persons with different views point out that the scriptures speak of Jesus’ brothers and sisters and “James the Lord’s brother.” Catholics respond that these may be children of Joseph before he married Mary or that the terms could include cousins in Jesus’ day. This doctrine underlines the absolute purity of Mary as the mother of God.

Bodily assumption

The doctrine of Mary’s bodily assumption into heaven at the time of her death is the most recent of the above doctrines and was canonized in 1950. The Roman Catholic Church determined that it did not make sense for Jesus to let his mother deteriorate in a grave, so logically, he must have taken her immediately to himself. As the author, I have little problem with this doctrine, for the God I know can do things like send a flaming chariot to pick up Elijah. Such an act would certainly be within the realm of God’s love and his power.

The Cross

The cross is a universal symbol of Christianity which Latter-day Saints have chosen not to adopt in order to distinguish Restoration Christianity from historical Christianity. Having said that, it is important that Latter-day Saints understand what the cross symbolizes for most Christians. There are actually three basic crosses among Christians (the Roman Catholic crucifix, the empty cross of Protestantism, and the crucifix of Eastern Orthodoxy). Each is a profound symbol defining Christ’s atoning work.

The Roman Catholic crucifix shows Christ hanging on the cross, head down in death. Some have suggested that Roman Catholics worship a dead Christ, but this is utterly wrong, as one would know by attending a mass and observing the emphasis on the risen Christ. But what the dead Christ does show is the price that Jesus paid for our sins. He gave himself so fully to us that he was willing to die for us while we were still sinners. Thus, this crucifix shows the extent to which God is willing to go to save us.

The Protestant cross is an empty cross. As a cross, it proclaims the Atonement and, like the Roman Catholic crucifix, the extent to which God was willing to go to free us from sin. It is, however, an empty cross, and in its emptiness, it proclaims that Christ is no longer dead but is risen. So the Protestant cross stresses both Christ’s sacrificial death and his Resurrection.

The Eastern Orthodox crucifix is perhaps the most complete symbol of them all. This symbol shows Christ crucified on the cross, but often his head is raised in triumph. What the Orthodox cross has done is combine Jesus’ suffering and death, by showing Christ crucified, with his Resurrection, by displaying the risen Christ on the cross. Of all the symbols, it best reflects the Gospel of John’s emphasis on “Christ’s hour,” which is both his death and Resurrection.

There is nothing in any of these symbols that contradicts Latter-day Saint thought, and it is important that Latter-day Saints respect these sacred symbols and understand them for what they are—profound portrayals of what Jesus has done for the human family in his triumphant overcoming of all that separates humanity from God.

The Reformation

Protestant Christianity has many of its roots in the Reformation, which is normally dated from October 31, 1517, when Martin Luther (1482–1546) nailed his Ninety-Five Theses to the church door in Wittenberg, Germany. In the theses, he challenged the Catholic practice of selling indulgences to release persons from purgatory to raise money for the renovation of churches in Rome. Luther never intended to start a new denomination. He simply wanted to discuss in an academic setting a practice that he felt was at variance with the scriptures. He ultimately defended himself before the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V, and was excommunicated, forcing his followers to kidnap him and hide him away for two years. Out of his activity grew the Lutheran Church, which is especially prominent in Germany, Denmark, Norway, Sweden, and Finland.

Martin Luther

Martin Luther

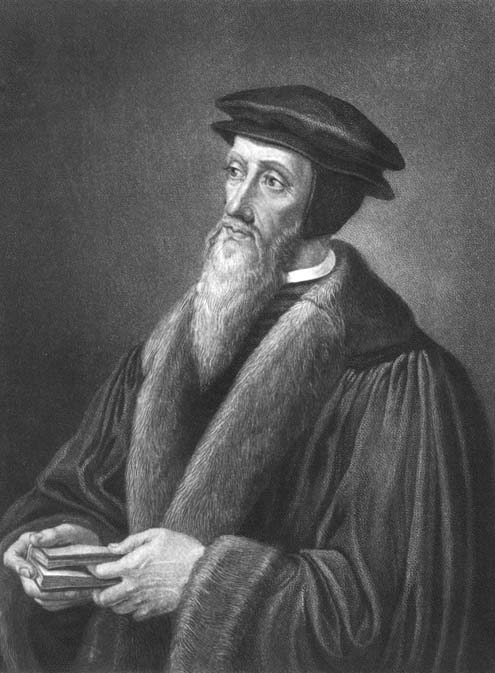

John Calvin, another Reformer (1509–64) was a French Catholic who had been studying law and became converted to the Reformation way of thought. He went to Geneva, Switzerland, where he was given full authority to run the city by his theological principles. Both he and Luther wrote biblical commentaries on virtually every book of the Bible, but Calvin was also very systematic in his thought, so he became the theologian of the Reformation. His major work is The Institutes of the Christian Religion, which any Protestant writing theology today still has to take into consideration. The Calvinist tradition gave rise to the Dutch Reformed Church and to the Presbyterian Church, which arose in Scotland under the guidance of John Knox (1514–72).

John Calvin

John Calvin

The Reformation currents affected England just at the time that Henry VIII (1491–1547) wanted to divorce Catherine of Aragon and marry Anne Boleyn. When the Pope refused to grant the divorce, Henry returned to an ecclesiastical model that diminished Rome’s influence on England. Before 600 CE, the English church traced its apostolic lineage to St. Andrew. At that time, the king was head of the church and approved the appointment of bishops and other high ecclesiastical authorities, so this became Henry’s model. He denied Rome’s authority and was excommunicated from the Roman Catholic Church. In response, he became head of the Church of England; confiscated all Catholic monasteries and estates, thereby increasing the Crown’s wealth; and organized clergy under his direction, once again approving bishops. He changed almost nothing, however, in the worship practices of the Mass. Later persons arose who challenged the formalism of the Church of England, some wanting to “purify” the church and others wanting to separate from it and create their own Calvinist tradition. Some of this latter group came to the New World on the Mayflower and established Plymouth Colony in 1620, and some of the former group sailed to the New World in 1630 and established Massachusetts Bay Colony. Essentially, the two colonies held the same theological views, and out of them came the Congregational Church.

On the continent of Europe, a group arose espousing “believer baptism,” and they became known as Anabaptists, meaning “to baptize again.” Virtually all children were baptized in Europe as infants. Thus, when the Anabaptists rebaptized people as adult believers, they were saying that the Catholic and the general Protestant baptisms were not effective. This led to persecution from both Catholics and Protestants. Probably the best-known Anabaptist was the Dutch Menno Simons (1496–1561), who founded the Mennonites, out of which grew the Amish. One of the English separatists who was influenced by the practice of believer baptism was John Smythe (1570–1612). He became recognized as the father of the Baptist tradition, which Roger Williams (c. 1603–83) followed when he was exiled to Providence, Rhode Island.

In eighteenth-century England, a group of students gathered regularly at Oxford to study the scriptures and to live a disciplined Christian life. Their lives were so methodical that they became known as “Methodists.” The best-known of this group is John Wesley (1703–91). Once ordained in the Church of England, he came to the colony of Georgia in the New World to convert the Native Americans and the frontiersmen to Christianity as he understood it. He was so rigid, however, that he ended up leaving the colony, having failed in his endeavor. Upon returning to England, he was one night attending a meeting in a hall on Aldersgate Street in London. A person was reading from the Preface of Luther’s commentary on the book of Romans, and Wesley reported that he “felt his heart strangely warmed.” This was the beginning of the experiential Christianity which became known as the Methodist Church. Wesley traveled all over England, preaching wherever he could, often outside because he was banned from preaching in Church of England buildings. In 1784, even though he was not a bishop, Wesley ordained Thomas Coke to be the superintendent of the Methodist Church in America. It and the Baptist Church soon became the churches of the frontier because neither required trained clergy as did the Presbyterian or Congregational Churches.

The roots of all Protestant denominations in the United States reach back to these early beginnings. Their theologies are informed by the theological principles we have examined throughout this chapter, although there are different emphases that mark them.

Conclusion

As diverse as Christianity is, its central focus is always on Jesus Christ. Every tradition, be it Eastern Orthodox, Roman Catholic, Protestant, or Latter-day Saint, is seeking to explain what it has heard God saying to it through his revelation of himself in Jesus of Nazareth. Undoubtedly, the differences between the faiths occur because the work of God is far too magnificent and grand for our small human minds to fully comprehend it. If we return to the idea in Jainism that each of us sees truth from different perspectives, then the true God, who reveals himself in Jesus Christ, may best be seen as a composite of all of our insights into who and what Jesus is and does. Perhaps instead of drawing artificial lines in the sand between one another, we should be willing to listen to what each has heard of the Emmanuel, the God with us in Jesus Christ. Perhaps we should see if others’ insights may not highlight something in our own traditions that we would have otherwise missed. It would be wise to remember that God is infinitely greater than we are. Thus, he must “babble like a baby” for us to understand him. He even speaks our language so fully that he, Jehovah, was willing to enter our world as a mere mortal, laying aside his glory, that he might suffer, die, and be raised on behalf of sinful and imperfect human beings like ourselves.

Notes

[1] “Major Religions of the World Ranked by Number of Adherents,” Adherents.com, last modified August 9, 2007, http://

[2] Front inside cover of Henry Van Dyke, The Book of Common Worship (Philadelphia: General Division of the Publication of the Board of Christian Education of the United Presbyterian Church in the United States of America, 1964).

[3] Andrew F. Ehat and Lyndon W. Cook, eds., The Words of Joseph Smith (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1980), 229; emphasis added.

[4] See Dallin H. Oaks, in Conference Report, October 1993, 98.

[5] Stephen E. Robinson, Believing Christ (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1992), 25–26.

[6] Doctrine and Covenants 20:25, 29; 63:20; 101:35.

[7] Dallin H. Oaks, “Always Have His Spirit,” Ensign, November 1996, 78–82.

[8] Timothy Ware, The Orthodox Church, new ed. (New York: Penguin Books, 1997), 224.