Bahá’í

Roger R. Keller, "Bahá'í," Light and Truth: A Latter-day Saint Guide to World Religions (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2012), 288–300.

Within the Bahá’í Faith is a concept of continuing revelation through which God addresses the human family. There is profound compassion for the human condition and a desire to better humankind.

Shrine to the Bab, Mount Carmel, Haifa, Israel. Here the remains of the Bab are enshrined. Courtesy of Tom Habibi.

Shrine to the Bab, Mount Carmel, Haifa, Israel. Here the remains of the Bab are enshrined. Courtesy of Tom Habibi.

The Bahá’í Faith (Bahá’í meaning “Follower of Splendor”) is the newest of the religions we will examine, arising almost at the same time as The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. The Bahá’í Faith has around seven million members, located in virtually every country of the world. [1] Bahá’ís have a strong sense of worldwide unity, not just among themselves but in their view of all races, religions, and peoples. They are inclusive of all persons and see God constantly working in this world through the various religious communities from the time of creation to the present and into the distant future. Theirs is a powerful message to a badly fragmented world which moves toward isolationism, not the direction that God would have the human family go. Bahá’ís have been and continue to be persecuted, primarily in the land of their birth—Iran. [2] Today their worldwide headquarters is in Haifa, Israel, located on a beautifully landscaped property on the slopes of Mount Carmel.

Origins

The Bab

The roots of the Bahá’í Faith lie in Shi’ite Islam, but the faith should never be considered a sect of Islam. It is its own religion. As stated in the Islam chapter, the Shi’ites believe that the Twelfth Imam went into hiding in 873 CE and that he was contacted thereafter through “gates,” or “Babs.” In the Bahá’í Faith, the concepts of the Hidden Imam and the Bab are brought together, for on May 23, 1844, Siyyid Ali-Muhammad (b. 1819) announced to one person that he was the one for whom people waited, meaning that he was the Twelfth Imam returned. On December 20, 1844, he made the same pronouncement to a group at the Ka’aba in Mecca. He became known as the Bab, and he saw himself preparing the way for one greater than he. He was a kind of John the Baptist.

His claim to be the returned Hidden Imam immediately met opposition from the Shi’ite clerics in Persia (today Iran). Clearly, such a claim threatened their position, and the persecution of the Babi community was launched with brutality so extreme that it almost defies description. The Bab proposed an entirely new society, much as did Muhammad or Joseph Smith, which would have challenged the existing views on economics, marriage, divorce, inheritance, and other issues. This idea of a new society challenged the status quo which kept the powerful in charge. The Bab was imprisoned, and then on July 9, 1850, he and a companion were brought out for execution by a firing squad made up of 750 Armenian Christian soldiers who did not want to execute him. They fired, and when the smoke had cleared, the Bab had disappeared, and his companion stood unhurt. A search for the Bab ensued, and he was found back in his cell completing a letter. He was brought out again, and a regiment of Muslim soldiers was marched out to perform the execution. This time both men were killed, but Bahá’ís see the first event as proof of God’s continuing involvement in human history by honoring the wishes of the Armenian Christians.

Baha’u’llah

One of the Bab’s earliest followers, declaring his faith in 1844, was a nobleman by the name of Mirza Husayn Ali (b. 1817). He carried on a constant correspondence with the Bab and became recognized in the Babi community as the best interpreter of the faith. As his stature and role increased within the community, he gave various sacred names to its members, taking upon himself the name Baha’u’llah, meaning “Glory to God.” His social standing kept him free of the persecution through which other members of the community were passing, but finally in 1852, he too was arrested. He was put in a dungeon in Tehran that had been a water cistern, and thus there was no outlet for sewage, making it a horrible place to be imprisoned. While there, he recounts the following experience:

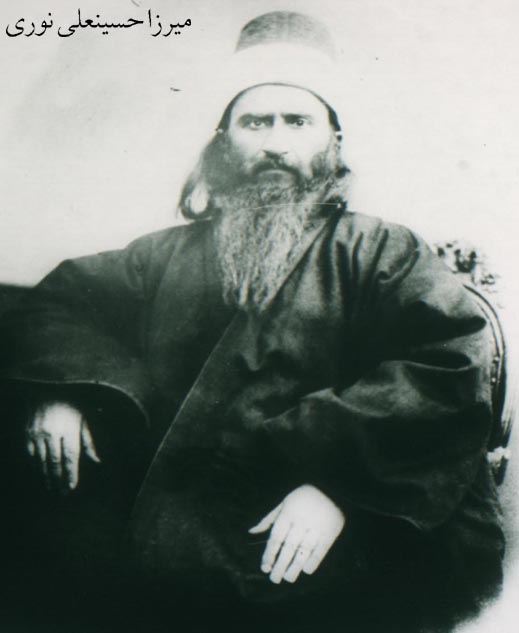

Baha'u'llah. Public domain.

Baha'u'llah. Public domain.

One night, in a dream, these exalted words were heard on every side: “Verily, We shall render Thee victorious by Thyself and by Thy pen. Grieve Thou not for that which hath befallen Thee, neither be Thou afraid, for Thou art in safety. Ere long will God raise up the treasures of the earth—men who will aid Thee through Thyself and through Thy Name, wherewith God hath revived the hearts of such as have recognized Him.” . . . During the days I lay in the prison of Tihrán [Tehran], though the galling weight of the chain and the stench-filled air allowed Me but little sleep, still in those infrequent moments of slumber I felt as if something flowed from the crown of My head over My breast, even as a mighty torrent that precipitateth itself upon the earth from the summit of a lofty mountain. Every limb of My body would, as a result, be set afire. At such moments My tongue recited what no man could bear to hear. [3]

Latter-day Saints reading this account cannot help but recall the Lord’s words to Joseph Smith as he languished in Liberty Jail in March of 1839.

My son, peace be unto thy soul; thine adversity and thine afflictions shall be but a small moment;

And then, if thou endure it well, God shall exalt thee on high; thou shalt triumph over all thy foes. . . .

And thy people shall never be turned against thee by the testimony of traitors.

And although their influence shall cast thee into trouble, and into bars and walls, thou shall be had in honor; and but for a small moment and thy voice shall be more terrible in the midst of thine enemies than the fierce lion, because of thy righteousness; and thy God shall stand by thee forever and ever. (D&C 121:7–8; 122:3–4)

Baha’u’llah’s experience in the dungeon confirmed to him that he was the one for whom the Bab was waiting, and there are indications that the Bab believed this before his death. After four months of imprisonment, Baha’u’llah, again in part because of his social standing, was released on the condition that he go into exile. He chose to go to Baghdad in present-day Iraq. His half brother, Mirza Yahya, challenged him for the leadership of the Babi community, and Baha’u’llah willingly gave up the leadership and retreated into the mountains. In 1856, the community begged him to return and assume leadership.

Even though Baha’u’llah was in exile, people constantly sought him out. His popularity began to trouble his enemies in Persia and, by extension, the Ottoman rulers of the area. In 1863, he was moved to Constantinople, but just before he left Baghdad, while he stood on an island named Ridvan (Paradise) in the middle of the Tigris river, he announced to a few of his closest associates that he was the one for whom they were waiting.

Even in Constantinople people flocked to see him, and the guards, impressed by his holiness and graciousness, continued to admit people into his presence. In December of 1863, he was moved again, this time to Adrianople, Turkey. As a result, Mirza Yahya tried again to take over leadership of the community, trying twice to have Baha’u’llah assassinated, but by 1864 the entire Bahá’í community had aligned itself with Baha’u’llah. In 1867, Baha’u’llah wrote a series of letters to the “kings of the earth” calling upon them to sublimate national interests to the well-being of all humankind. An excerpt reads as follows:

The time must come when the imperative necessity for the holding of a vast, an all-embracing assemblage of men will be universally realized. The rulers and kings of the earth must needs attend it, and, participating in its deliberations, must consider such ways and means as will lay the foundations of the world’s Great Peace amongst men. . . . It is not for him to pride himself who loveth his country, but rather for him who loveth the whole world. The earth is but one country, and mankind its citizens. [4]

His opponents used these letters as a sign of an international conspiracy, leading the Ottoman authorities to move Baha’u’llah in 1868 to one of the worst prisons in their empire—Acre, across the bay from Haifa, Israel—where they assumed he would die from the terrible conditions. It was said that if a bird flew over the prison, it would die in flight from the stench. Once again, the people were not to be denied, for they flocked to see this holy man, and once again, the guards let them in. Finally, in 1877, Baha’u’llah was moved to a country estate where he spent the remainder of his life under house arrest, but he at least had access to the people who wanted to see him. He died May 29, 1892.

Mansion of Bahif, Acre, Israel, where Baha'u'llah spent the last years of his life under house arrest. Courtesy of Arash Hashemi.

Mansion of Bahif, Acre, Israel, where Baha'u'llah spent the last years of his life under house arrest. Courtesy of Arash Hashemi.

The Successors

Baha’u’llah was succeeded by his eldest son, Abdu’l-Baha, who was recognized as the authoritative interpreter of the Bahá’í Faith and the perfect human example of how to live the faith. Abdu’l-Baha was responsible for spreading the faith to Europe and North America and bringing the Bab’s remains to the slopes of Mount Carmel in Haifa, Israel, where they now lie enshrined. He died in 1921.

Abdu’l-Baha was succeeded by his eldest grandson, Shoghi Effendi Rabbani, who went to university at Oxford in England. He was known as the Guardian of the Faith and its interpreter and guide. Under his leadership, the faith expanded worldwide, and it was he who made it possible for the Universal House of Justice to succeed him upon his unexpected death in 1957. Today the Bahá’ís are governed by the Universal House of Justice, which is composed of nine men elected for five-year terms. The decisions they make through prayer, study, and consultation are viewed as binding on the community.

The writings of the Bab and Baha’u’llah are foundational to the faith. Probably one of the most important writings is Baha’u’llah’s Kitab-I-Aqdas, which covers virtually every area of life. In addition to the writings of the two founders, the works of Abdu’l-Baha and Shoghi Effendi are also considered authoritative guides for the faithful.

Bahá’í Teachings

God

God in the Bahá’í Faith is much like God in the Muslim faith. There is only one God, who has created all things from nothing. He is the Unknowable Essence, but humans can know him through his works and his Manifestations.

The Greater and Lesser Covenants

God has made the Greater Covenant with the entire human family. He covenanted to send, approximately every one thousand years, a Manifestation to lead the human family to a higher plane. A Manifestation is a different kind of being than normal humans. He had a spiritual premortal life and is morally perfect. There is a very real sense of spiritual evolution within the Bahá’í Faith, with each Manifestation building on the work and teachings of the prior Manifestation. Thus, there is only one religion of God, and all the Manifestations teach it, but they give to the human family new aspects of that religion when they come. For example, Abraham taught the human family that there is one God. Moses taught the law of the one God. The Buddha taught that humans should be detached from themselves and the things of the world which will never bring them to God. Jesus taught that we are to love God and our fellow human beings because God loves us. Muhammad taught that we are not to be fragmented into clans and tribes but that we should be transcending these narrow boundaries and binding people together in nations. And now Baha’u’llah comes to teach us that even that is too narrow and that we should learn to see that humanity is all one family. He teaches that all our destinies are interlaced with one another and that there must be a unified government. No Manifestation is wrong; rather, each Manifestation stands on the shoulders of the predecessors and adds to what they have given the human family. Bahá’ís now look forward another thousand years to another Manifestation who will help humanity grow further, and they believe this succession will continue on forever. There is no concept of the end of time or history in Bahá’í thought.

The Lesser Covenant is that which is made between a Manifestation and his followers. Thus, Jewish people follow the Lesser Covenant between themselves and Moses. Christians follow the Lesser Covenant between themselves and Jesus, and Muslims follow the lesser covenant between themselves and Muhammad. If persons truly understand the Bahá’í message, they will know that with the arrival of a new Manifestation, they should add to the Lesser Covenant with the Manifestation they are currently following and establish a new covenant with the new Manifestation. Thus, the Bahá’í faith invites Buddhists, Jews, Christians, and Muslims to participate in the new covenant that has been revealed, but should they choose not to do so, they are still part of the one religion. If persons attend a Bahá’í meeting, no matter what their faith tradition, they may well be invited to pray in their accustomed way or to share a passage from their sacred scriptures, for we are all of one human family and of one religion.

Beliefs

Bahá’ís believe firmly that persons should be open to all truth wherever it is found. Humans should be open-minded and lay aside prejudice and superstition. Thus, science and religion are not antithetical to one another but rather are two ways of accessing knowledge that is complementary. Religion, for example, tells us who created, but not how. That is the province of science. Hence, there is no necessary conflict between science and religion, and when there is an apparent conflict it is usually because persons have limited knowledge in both fields. People should be humble before the two disciplines.

Men and women are completely equal in the Bahá’í Faith and may serve in all capacities in the faith, although it is an anachronism that only men twenty-one years or older may be elected to the Universal House of Justice. Bahá’ís feel that there needs to be more of a feminine influence in the world, with the ideals of relationality and love overriding the more confrontational male model. In line with this idea, members of the Bahá’í faith believe in universal education, but if that is not possible, they believe that women should be educated because they raise the next generation. Brigham Young of the Latter-day Saint faith made a similar assertion.

Bahá’ís feel that the extremes of wealth and poverty which exist in our modern world are wrong. They assert that a voluntary limit should be placed on what any one person makes and that persons should distribute their excess to the broader community, though they do believe in private ownership. Mutual assistance and helpfulness are the real watchwords of their economic policies. This sounds very much like the law of consecration found in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Its aim was to see that everyone had the necessities of life, but where there was excess, it was shared with those in need. Similar to the Bahá’ís, the church practiced private ownership under the law of consecration, but the goal was to limit inequities in economics.

Bahá’ís also believe that our international problems exist in part because we cannot communicate with one another. Thus, Bahá’ís believe that there should be a universal auxiliary language. Children would learn their native language from birth, but around the age of five or six, they would begin to learn the auxiliary language so that people around the world could communicate directly with one another. There is no language specified at this time, but English, Arabic, and Chinese could be contenders.

Bahá’ís abstain from the use of alcohol and drugs. They fast as do many religions, and their fast lasts nineteen days during the daylight hours from March 2 through 20. Marriage is both a social and a spiritual relationship, and it is not solely about two people. It must and does include the families of the couple. After a couple has freely chosen one another, permission to marry must come from the living parents of both partners, and if that permission is not forthcoming, the marriage cannot take place. It is expected that couples will practice chastity before marriage and will be committed solely to one another after marriage. Divorce is permitted, but it is expected that a couple contemplating divorce will practice patience by waiting a year, during which they will seek counseling and attempt to resolve their differences.

One of the most important concepts in the Bahá’í Faith is that of consultation. There may be a clash of opinions, but all speak their own truths. The goal is genuine group consensus, and this should be true especially in marriage. A decision of fifteen people with eight for an item and seven opposed to it is never a good decision because from the beginning, half the group is against the action. Thus, although it takes longer to reach genuine consensus, this is always the Bahá’í goal, for then everyone is headed in the same direction. Among Latter-day Saints, this is the way the Quorum of the Twelve come to decisions. There is debate, but until there is consensus, no decision is made. This concept of consultation leads to the Bahá’í abstention from involvement in politics, which by its very nature is divisive. Bahá’ís cannot run for office, post political signs in their front yards, or use bumper stickers supporting a candidate. They are encouraged to vote, and they may serve their communities through nonpolitical appointments, but, in harmony with Latter-day Saint doctrine, they believe that where there is contention, the Spirit cannot be present. Thus, they do not enter into confrontational settings of any sort.

If non-Bahá’í persons find the Bahá’í principles and practices attractive and want to contribute to the cause, they cannot, for that is the privilege of the Bahá’ís. Bahá’ís are expected at a minimum to tithe 19 percent of monies they have accumulated after expenses and debts are met.

In the end, life for Bahá’ís is a time of spiritual preparation for the soul’s progression toward God in the afterlife. Heaven and hell in the Bahá’í Faith are not places but stages of progression. The soul that is progressing toward God is experiencing a heavenly state, and that soul which is not progressing is distant from God and experiencing a kind of hell. As noted earlier, there is no last judgment or end of time in Bahá’í thought, but rather an ongoing process of endless progression, which sounds very much like the Latter-day Saint concept of eternal progression. However, according to Latter-day Saints, there are definitely a last judgment and final place to which the resurrected bodies and spirits of all persons finally go.

Practices

The Bahá’í calendar is composed of nineteen months, each of nineteen days and with four or five additional days to round out the solar year. Once a month, there is a Feast Day, similar to a Sabbath day in Christianity and Judaism. It is a day for worship, group business, and social interchange. There is the annual fast already mentioned, as well as nine other holy days during the year, during which work is suspended. There is a festival known as Ridvan from sunset of April 20 to sunset of May 2 which commemorates Baha’u’llah’s announcement on the island of Ridvan that he was the one for whom the community was waiting. Beyond this, the Bahá’í faith has few rituals. The one thing all Bahá’ís do is recite the daily obligatory prayer, which appears in short, medium, and long forms. The medium prayer is to be said three times a day—at morning, noon, and night. The short form gives a sense of Bahá’í piety:

I bear witness, O my God, that Thou hast created me to know Thee and to worship Thee. I testify, at this moment, to my powerlessness and to Thy might, to my poverty and to Thy wealth. There is none other God but Thee, the Help in Peril, and Self-Subsisting. [5]

The goal. The current Bahá’í administrative structure is a religious shadow of what Baha’u’llah has called the human family to create. We are one as a family, and, therefore, the goal is a one-world government brought about through spiritually changed hearts. The Bahá’í structure consists of the Universal House of Justice; National Spiritual Assemblies, each composed of nine members; and, at the local level, Spiritual Assemblies, once again composed of nine members, which support and guide the Bahá’ís in a local community. Bahá’ís spread the faith without pressure. If there is an area where no Baha’i is living, a family may move to that region to create a presence. As people hear the message, they may choose to join a growing and impressive faith community.

Universal House of Justice, Haifa, Israel. Public domain.

Universal House of Justice, Haifa, Israel. Public domain.

This structure is the precursor of a world commonwealth. The vision for this world order is that there would be a world executive, a world legislative body, a world court, and a world police force drawn from all nations. When confronted with despots and dictators who brutalize their people, the world community would remove them through consultation or, if absolutely necessary, through a united military force, thus creating a peaceful world. This world community will not happen overnight, however. There must first come a total social breakdown, which will lead to the Lesser Peace, meaning that there will be a complete cessation of war, since everyone will be exhausted by its brutalities. But it will create a political unity. Out of the Lesser Peace will arise the Greater Peace, which will be a spiritual unity, from which will emerge a new world order as people’s hearts are changed by God. This sounds very much like the progression of events that will lead up to the millennial reign of Christ, according to Latter-day Saints. The Bahá’í world order is brought about primarily through a spiritually changed human family, while the Millennium is brought about through the return of Jesus Christ.

Conclusion

There is much that is attractive within the Bahá’í faith. There is a concept of continuing revelation through which God addresses the human family, revelation that comes in blocks every thousand years and is then progressively unpacked by the Universal House of Justice until the coming of the next Manifestation. There is profound compassion for the human condition and a desire to better humankind. There are excellent moral standards and a commitment to improving the social order, but without confrontation and contention. Guided by God, people can make their world better, and all persons are welcome at the Bahá’í table, if they share similar goals. After all, we are all of the one religion, just following different Manifestations, all of whom God has sent to us.

Notes

[1] “Major Religions of the World Ranked by Number of Adherents,” Adherents.com, last modified August 9, 2007, http://

[2] Bahá’í International Community, “Persecution,” accessed November 11, 2011, http://

[3] Quoted in William S. Hatcher and J. Douglas Martin, The Bahá’í Faith: The Emerging Global Religion (Wilmette, IL: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1998), 34.

[4] Quoted in Hatcher and Martin, The Bahá’í Faith, 40.

[5] Robert E. Van Voorst, Anthology of World Scriptures, 6th ed. (Mason, OH: Cengage Learning, 2008), 338.