Migration- It's in Our Blood

Implications for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

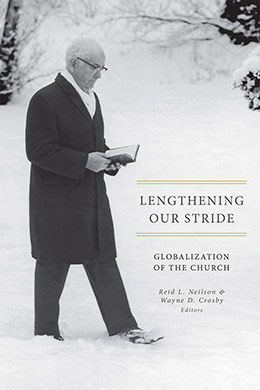

T. Edgar Lyon

Lyon, Ted E. “Migration—It’s in Our Blood: Implications for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.” In Lengthening Our Stride: Globalization of the Church, edited by Reid L. Neilson and Wayne D. Crosby, 257–268. Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2018.

Ted E. Lyon, then professor of Spanish at Brigham Young University, presented this essay at “‘The Perplexities of Nations’: Current Trends and the International Church,” the International Society’s eighteenth annual conference, April 2007, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah.

Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem. The geographical boundaries historically shared by the Islamic world and Christendom have led to multiple conflicts between the two civilizations.

Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem. The geographical boundaries historically shared by the Islamic world and Christendom have led to multiple conflicts between the two civilizations.

The genesis of this paper stems from simple observation—The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is sending Spanish-speaking missionaries to every state in the United States, including unlikely spots such as Alaska, North Dakota, and Tennessee. Many of the missions in Canada receive young missionaries who will teach and baptize in Spanish. Members of the largest Church units in Stockholm, Sweden, speak little Swedish; Spanish is the language of the ward, and most are displaced Chileans and other Latin American émigrés.[1] But Hispanics are not the only immigrants hearing the gospel and joining the Church outside their native countries. Many Africans hear the gospel in Germany or Portugal; Chinese travel to Singapore to find work and often find the missionaries as well. Lebanese and Iraqi refugees seek asylum in Denmark and not only discover peace but also the gospel. Spain and Italy, often unwillingly, host North Africans, who hear and respond to the message of the Restoration in those foreign countries. In developed areas of the world, a large percentage of Latter-day Saint baptisms occur among immigrants to those countries. The percentage is higher, usually much higher, than the total number of immigrants in that country. Immigrants are joining and contributing to the Church.

Based on this initial observation, I began asking questions and seeking to know just how many of our Latter-day Saint converts were immigrants to the country in which they were baptized. I consulted with the Church offices and was informed, kindly, that data relating to national origin of converts is “proprietary and confidential.”[2] I turned to Rodney Stark, a well- known sociologist of religion who has written a considerable amount on Latter-day Saints. I posed many detailed questions and explained my need for data on just who is being baptized into the Church. He wrote back immediately, stating, “Those are very interesting questions and I don’t know the answers [at all] nor where to find data. If you discover anything useful, I would very much like to know about it. Sorry.”[3] In short, he understood my research questions but had no data to share. For the above-noted reasons, my sources are limited to general fact books (the CIA World Factbook and other similar summaries), UN studies and documents on world migration, and scholarly studies dealing with immigration and religious conversion in general. I have also conducted interviews with Latter-day Saint mission presidents, missionaries, and recent converts in an attempt to establish a baseline percentage of how many converts are immigrants to the country in which they are baptized. These latter sources are both experiential and anecdotal.

Migration: A Worldwide Phenomenon

In the year 2007, the estimated world population stood at 6.5 billion people. A small percentage of this large number, approximately 3 percent, live outside their country of origin.[4] Yet, 3 percent means 191 million people, more than the total population of France, Germany, Spain, Austria, Belgium, Holland, and a few other smaller European countries. These are people on the move, displaced by desire, by hope for a better economic future, by political strife; in short, these are people who were not content with their status or the situation into which they were thrust or born. It is obvious that these displaced, upward-seeking human beings are often susceptible to a new message, a message of hope, of future, of a new beginning. Conversion to the Church is dramatically and disproportionately high among these modern-day immigrants.

A related factor to the concept of religious conversion among the newly arrived is internal migration, typically urbanization within one’s own country. This process of urbanization is occurring on every continent in the world. Philip Jenkins convincingly demonstrated the effect that urbanization has exerted on conversion to Christianity. “In its early days, African Christianity [for example] was conspicuously a youth movement, a token of vigor and fresh thinking,” composed mainly of ambitious young adults who would travel to large cities and ports seeking work, where they also found Christian missionaries.[5] Conversion to a Christian religion was filled with energy, as the rural workers often returned to their native villages carrying on the evangelization with friends and relatives.

While this paper cannot explore the effects of internal migration on Latter-day Saint conversion rates, nearly every missionary knows that as people displace themselves from the stability of a rural area, they often open up to new ideas. In Followers of the New Faith, Emilio Willems demonstrates the power of urbanization and conversion in Brazil and Chile.[6] The newly arrived have usually broken ties with old friends, tradition, family pressures, and their native-born religion and are seeking for something better. New friends in the new city mean new contacts and possibilities for employment. Foreign missionaries and established members often provide a model for what a newly arrived city-dweller hopes to achieve. The hundreds of excellent Church employment resource centers around the world could wisely target and recruit this group, encouraging them to participate in the very successful ten-hour-workshop training program. Unfortunately, I will not be able to pursue urbanization as a source for Latter-day Saint baptisms, but it is truly a fertile field and one that should be studied in depth.

Political and economic refugees are yet another source of displacement in the contemporary scene. In 2005, worldwide political refugees numbered approximately 9.2 million. These dislocated people, often victims of violence and frequently living in extreme poverty, may also be open to the preaching of the Restoration. However, their most urgent needs will likely be met first by the Church’s humanitarian services and other similar organizations. This paper cannot consider political refugees as a unique group—they, too, are migrants and exhibit even more spiritual and physical needs than do most other immigrants. They certainly make up a vital percentage of Latter-day Saint baptisms and contribute their unique experiences to their new church.

Neither can this paper discuss the problem of illegal immigration. A recent estimate calculates that each year in the world some four million people cross borders illegally to reside in another country.[7] The four million figure appears very low to me, based on the fact that most country borders are very porous, controls are generally inadequate, and counting illegal crossings is almost impossible. Reliable observers estimate that in the US alone there are now eleven to twelve million illegal immigrants. Of course this number represents a build-up from many years, but nevertheless, several million people a year cross into (and sometimes out of) the US. Latter-day Saint missionaries are instructed not to be concerned about the legality of their teaching contacts nor to pose such problematic questions during their lessons. In short, the problem exists for the host country but not for the missionaries nor for those who wish to join the Church.

In sum, worldwide migration is occurring at an increasing, not decreasing, rate. Migration should not be feared; it has been the lifeblood of many societies and nations. In 1776, the rebellious American colonies boasted three million people; today more than 300 million citizens call the US home, and legal immigration to the US continues to be the major source of growth, more than a rapidly expanding birthrate. For example, during the 1990s the nation’s population grew by nearly 33 million, the largest ten-year increase ever; the great majority of this increase was foreign born.[8]

Obviously, migration creates problems in the host country—often a change in the status quo of that nation—but it also deepens and broadens that host culture. A simplistic but obvious example is that there are now more pizza outlets and more taco sites than hamburger “joints” in the US. Music, the visual arts, entertainment, and so forth in the United States are all richer because of the millions of twentieth-century immigrants who have made this country a center of invention and innovation.

Most of the immigrants throughout the world make their way to a new country to find work and to create a better economic life for themselves and their families. Thirty market democracies in the world form the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). One-fourth of the workforce in Austria, Switzerland, and Luxembourg are foreign-born; nearly 12 percent in the US are foreign born, and certainly the number is much higher when illegal workers are factored in. South Korea, Ireland, Austria, and Finland experienced more than a 100-percent increase of foreign-born workers in ten years. Every one of these thirty countries has witnessed increases. These thirty countries also demonstrate a high percentage of foreign-born Latter-day Saint converts.

Migration Traditions and The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

Quite obviously, the first converts to the Restoration were family, friends, and neighbors of Joseph Smith. But as that pool exhausted itself and local opposition deepened, Joseph sent the Quorum of the Twelve and a few others first to Canada and then to Great Britain. Even in Joseph’s short lifetime, missionaries journeyed through Europe, to the Holy Land, to the Caribbean, and to the Pacific Islands. All of these early missionaries preached the doctrine of the gathering—emigrate or be damned. For sixty years, this doctrine infused life and new blood into Nauvoo, and later, into nearly three hundred developing communities in the Mountain West. By the early twentieth century, the doctrine changed, and members in foreign countries were encouraged to “stay home” and “build Zion” in their country of origin. Yet this preachment has not stopped the migration; each year, thousands of Latter-day Saint immigrants flow out of Africa, abandon Tonga and Samoa, and leave Argentina and Chile for good; they depart their homeland in Russia or the Ukraine and quit scores of other countries. Most of the Latter-day Saint immigrants come to the US if possible, and some go to Europe. They seek a better life, partially because they see new possibilities, new opportunities, and a chance to advance and make a better future for their children.

The migrating Latter-day Saints have scriptural precedent. The Book of Mormon is truly a story of migration. Lehi and his family were “called out” of the Old World to avoid impending violence and commanded to journey to a land of promise. Four hundred years later, Mosiah abandoned the comfortable old city of Nephi and made his way down to Zarahemla, where he found the descendants of another band of immigrants—the Mulekites. Alma had to escape the political oppression of his Lamanite tax masters and sought refuge in Zarahemla. In the next generation, the converted and immigrant people of Ammon so burdened the hospitality of the seven churches in Zarahemla that they were granted a nearby land of their own—Jershon. Zarahemla, which had been the haven to so many immigrant groups, soon became wicked, and the Church’s leaders moved on to Bountiful, bringing the faithful with them. After too brief a period of peace and prosperity, war again broke out, and Mormon and Moroni escaped northward, becoming refugees from the tragic violence that ends the book. Truly, there is spiritual precedent for migration to avoid violence and unite with larger spiritual units.

In the developed and generally peaceful OECD countries, Latter-day Saint missionaries are finding, teaching, and baptizing a large number of immigrants, a much higher number than their proportion in the new country, and generally a higher percentage than that of native-born citizens of that same country. One single cosmopolitan mission may have missionaries who teach in eight or ten languages. The New York New York South Mission boasts some fourteen foreign languages among its missionaries. In 1990, the population of New York City was 28 percent foreign born. By 2000, that proportion had increased to 40 percent, and it continued to climb to approximately 45 percent in 2007. At the present time, 52 percent of the foreign-born in the US come from Latin America.[9] And Latter-day Saint missionaries are finding these fields; they are finding them “white already to harvest.”[10]

The assistants to the mission president in Miami, Florida, reported to me that between 60 and 65 percent of their monthly baptisms come from the Hispanic population (not all of whom are foreign born, of course). My own son recently reported that in his mission in Anaheim, California, approximately half of the converts were Spanish-speaking and another 10–15 percent were from other foreign-language groups. Missionaries in the Utah Provo Mission inform me that 30 and 40 percent of their converts are natives of other countries; this includes many Asian students at BYU. Quite logically, 50 percent of the converts in the New York New York South Mission, with its multiple languages, are from abroad.

Similar statistics apply in many other developed countries in which the gospel is preached. Missionaries in one particular mission in Germany (Hamburg) baptized 118 new members in 2006. Of these 118 baptisms, 72 were native Germans, but the other 46 (39 percent) were foreign born. It is instructive to note that several of these baptisms come from China, Afghanistan, and Iran, countries in which there are currently no Latter-day Saint missionaries, nor an official Church presence. Others came from Ghana, Nigeria, Peru, the Philippines, Poland, and Romania. These types of international baptisms give the Church a worldwide flavor in most of the OECD countries.

Some might question Mexico’s placement among the OECDs (there are only three Western Hemisphere countries on the list), yet it too receives thousands of immigrant workers and refugees from Cuba and from Central and South American countries. Newspaper articles and editorials in Mexico often lament the uncontrolled influx of poor foreigners and call for tighter border controls and higher fences. The Latter-day Saint missionaries in Mexico often meet these immigrants, teach them, and baptize them.

Foreign-born university students in OECD countries are discovering the Church and Christianity in general. A recent study has shown that during their first year in the US as foreign students or visiting professors, “about one-third of People’s Republic of China students and scholars . . . had become Christian by the end of [their] research [year].”[11] The study’s author lists reasons why such a high percentage of Chinese students, usually raised with little or no religious background, seek out Christian churches in the US.

He says they feel “marginality, rootlessness, amnesia, anger, frustration, alienation, and helplessness” in their new setting, and may discover that a community of Christians does indeed help alleviate these negative feelings.[12] This study does not deal exclusively with Chinese students who join The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, but experiences on BYU campuses demonstrate that every year, scores of Chinese nationals prepare for and receive baptism in the Church. This paper postulates that, similar to the 33 percent of Chinese students who join Christian churches in the US, in most developed countries, between 30–40 percent of the Church’s baptisms occur among immigrants to that country.

A recent letter from a Latter-day Saint sister missionary serving in Macau details the conversion of a large family from China:

Last Saturday and Sunday we were so busy to teach eight people from mainland China. We taught them from 11:00 to 6:00; after that they had the interview. Then they could be baptized on next day. In Macau, I have many opportunities to teach the lesson[s] like that; we called Miracle Baptism, because they can’t stay here for a long time, and they can’t learn the lesson in China, so they come to H[ong] K[ong] or Macau to be baptized. [signed, Sister Lau; original grammar and spelling maintained][13]

Obviously, the teaching and baptisms had to be rushed—the family heard about the Church in China but had to leave that country to receive the formal missionary lessons and

apply for baptism.

This family of eight, similar to hundreds of Latter-day Saint Chinese baptized in the US, Hong Kong, Germany, and many other countries, has now returned to their homeland. They may find a local Church congregation with whom to meet, but they may also drift away to one of the many Christian gatherings in that country, or they may have to practice a simple form of Latter-day Saint worship in their own homes. In this way, the Church is spreading to areas of the world where formal preaching is not now possible.

What to Do with Migrants in the Church

Multiple factors explain why Latter-day Saint missionaries experience surprising success among immigrants. A first and obvious reason is that many immigrants find that in joining a new religion, they can escape the marginality and alienation mentioned in the study of Chinese students who have come to the US. The Church usually provides an instant community of friends and already integrated citizens for the foreign-born convert. He or she will likely find someone who “speaks my language” because so many returned missionaries do indeed speak a foreign language. Social identity with the new group adds legitimacy; the convert often perceives the new religion as providing upward mobility in a society that appears to be very rigidly structured. In short, the convert sees a chance for more personal progress in the new church. The foreigner has also likely left behind some family bonds that existed in the home country; unfettered, he or she is now open to new ideas and spiritual feelings and can more easily embrace a new religion. Further, the immigrant has likely come to the new country with a hope for economic improvement. He or she first notices and is taught by well-dressed Latter-day Saint missionaries, then attends a neatly groomed and well-cared-for chapel and associates with stable, employed Latter-day Saints. The immigrant can visualize achieving the same circumstances with the help of these new friends.

I do not want to diminish the role of the Holy Ghost in the conversion process; the factors mentioned in the previous paragraph generally work on the individual to then allow the Spirit to touch him or her. The new environment, removed from old family ties and a traditional religion, or no religion at all, allows the immigrant to feel the Spirit more deeply. The instructions in Preach My Gospel place a necessary emphasis on the missionary’s spiritual preparation so that he or she can guide the investigator to feel and properly respond to the powers of the Spirit. Based on the aforementioned reasons, immigrants in every country appear to experience and bask in this Spirit more easily than many nationals.

Foreign-born Latter-day Saint converts may create challenges for themselves as well as for the Church. How will they best be integrated to assure permanence and enduring to the end? What language will they speak for the first few years of their new membership? How will longstanding members relate to someone who represents a different culture? How does a mission president, stake president, or bishop provide leadership for a culture and language with which he is not familiar? How does the Church retain an Asian or African convert who returns to a homeland with no organized Church structure? What do we do about the many converts who are in the new country illegally? (As noted, Latter-day Saint missionaries do not inquire regarding the legal status of their contacts, nor is legal status a part of the baptismal interview, yet the fact that many illegal immigrants are baptized may bother or even shock long-term members.) Should foreign-speaking branches, in any country, strive for full linguistic and cultural integration, or should they maintain a separate identity in order to achieve a higher retention rate? Are we providing the proper support for diverse groups, or is it even possible to do so? Do members resent new converts who are often economically dependent on others and cannot meet their own needs? Mark Grover has shown that “in 1985, over 50 percent of the membership of the Church in Portugal had previously lived in Africa.”[14] These immigrant converts are often poor and lack the means of self-support. Will their economic status indeed change once they are baptized, or will they become a constant burden to Church resources? There are more questions than answers, and there are still many more questions.

For the present, Latter-day Saints worldwide must accept the fact that 30–40 percent of baptisms in OECD countries will be immigrants. It’s in our blood as descendants of past-- generation converts. It’s in our scriptures. It’s part of the reality of the contemporary world. Just as Mosiah’s people infused new spiritual life and a new language into the established culture of Zarahemla, and just as the converted people of Ammon set an example of nonviolence to the established Church, new foreign-born converts will also enrich the culture of the present-day Church.

Notes

[1] Reported openly to the Chilean ambassador to the United States in a conversation with President Thomas S. Monson, Salt Lake City, Utah, 17 April 2007.

[2] Phone conversation with Cyril Figuerres, 16 March 2007.

[3] Rodney Stark, email to author, 17 March 2007.

[4] “Factfile: Global Migration,” BBC News, 2009.

[5] Philip Jenkins, The Next Christendom: The Coming of Global Christianity (New York: Oxford University Press, 2002), 43.

[6] Emilio Willems, Followers of the New Faith: Cultural Change and the Rise of Protestantism in Brazil and Chile (Nashville, TN: Vanderbilt University Press, 1967), 83–92.

[7] UNFPA, “Meeting Development Goals,” 1.

[8] David J. Garrow, “Images of a Growing Nation, from Census to Census,” New York Times, 13 October 2004.

[9] Garrow, “Images of a Growing Nation, from Census to Census.”

[10] Doctrine and Covenants 4:4.

[11] Wang Yuting and Fenggang Yang, “More than Evangelical and Ethnic: The Ecological Factor in Chinese Conversion to Christianity in the United States,” Sociology of Religion 67, no. 32 (2006): 179.

[12] Yuting and Yang, “More than Evangelical and Ethnic,” 179.

[13] Wing Yi Lau, email to author, 28 March 2007.

[14] Mark Grover, “Migration, Social Change, and Mormonism in Portugal,” Journal of Mormon History 21, no. 1 (Spring 1995): 76.