Editors' Preface

Reid L. Neilson and Wayne D. Crosby, "Editors' Preface," in Lengthening Our Stride, ed. Reid L. Neilson and Wayne D. Crosby (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2018), xv–xxiv.

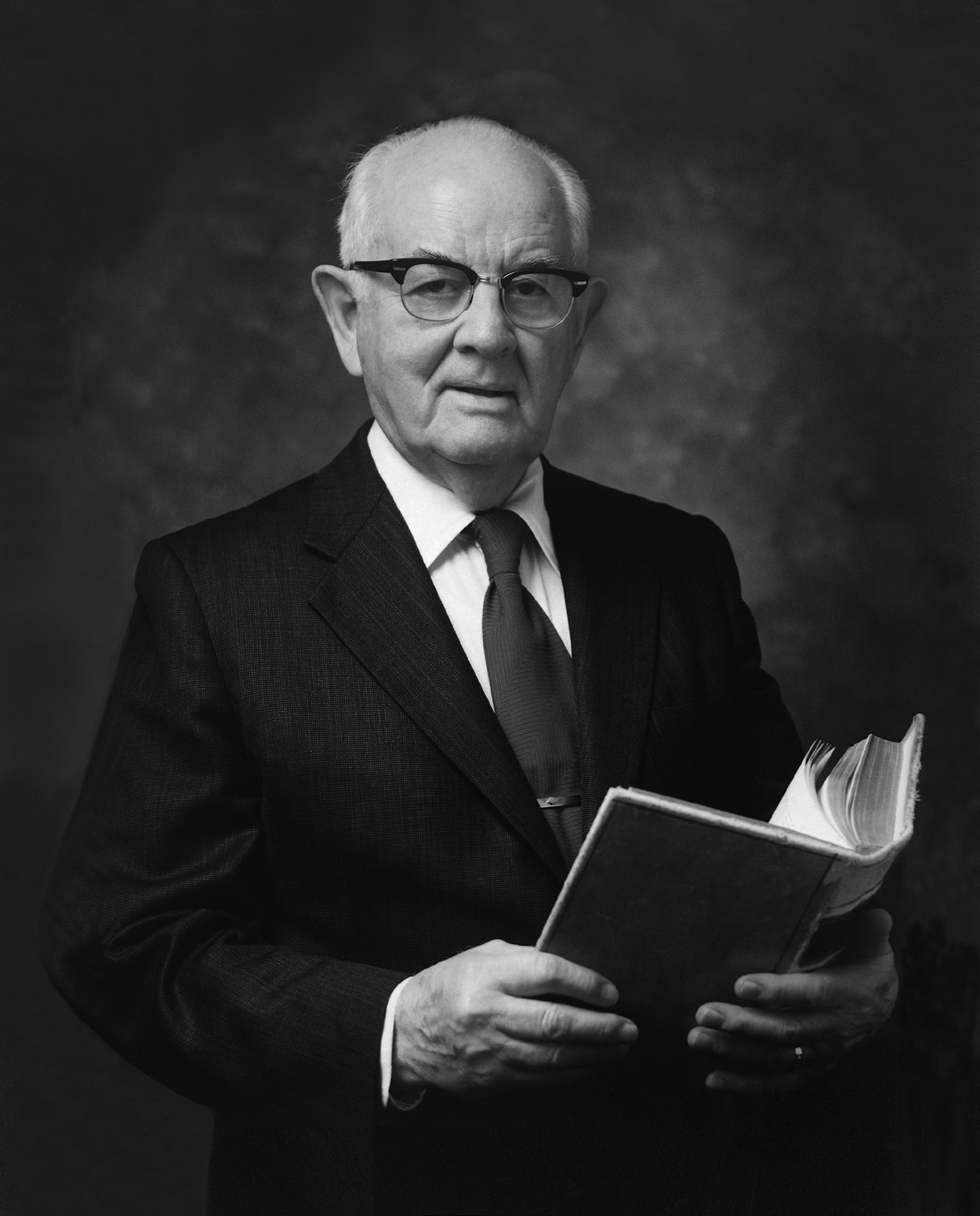

Spencer W. Kimball served as President of the Church from 7 July 1972 to 30 December 1973. (Courtesy of Intellectual Reserve, Inc.)

Spencer W. Kimball served as President of the Church from 7 July 1972 to 30 December 1973. (Courtesy of Intellectual Reserve, Inc.)

Thoughtful observers have noted that the doors of world history turn on small hinges. Likewise, when the Book of Mormon prophet Alma the Younger entrusted his son Helaman with the Nephite records in about 74 BC, he reminded Helaman “that by small and simple things are great things brought to pass; and small means in many instances doth confound the wise” (Alma 37:6). In our study of the sacred past of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints we have sought to identify and appreciate pivotal events—large and small—in the unfolding Restoration. One such moment occurred on 4 April 1974, when President Spencer W. Kimball delivered a landmark address on LDS proselytizing possibilities at a regional representatives seminar (see appendix 1).[1] He spoke on the future possibilities of the global Church for one hour and ten minutes—his sermon was marked by crescendo, not diminuendo! The small-in-stature, newly ordained prophet called for Latter-day Saints to “lengthen our stride.”

Among the General Authorities in attendance that day was Elder W. Grant Bangerter, who recalled being spiritually stimulated by President Kimball’s remarks. “He had not spoken very long when a new awareness seemed to fall on the congregation. We became alert to an astonishing spiritual presence, and we realized that we were listening to something unusual, powerful, different from any of our previous meetings. It was as if, spiritually speaking, our hair began to stand on end,” he later described. “Our minds were suddenly vibrant and marveling at the transcendent message that was coming to our ears. With a new perceptiveness we realized President Kimball was opening spiritual windows and beckoning to us to come and gaze with him on the plans of eternity.”[2] Another Latter-day Saint analyzing the apostolic rhetoric of President Kimball noted that his 1974 sermon “outlined in detail how the Savior’s command to take the gospel to all the world could be literally obeyed—and soon. The speech was not flamboyant in style nor did it announce any dramatic new program. It merely reviewed the clear commands of Christ to his former- and latter-day disciples.”[3]

The Church that President Kimball began to lead at the turn of 1974, which was still largely focused on the American Intermountain West, looked very different from the Church in 2015, a mere four decades later. At that time, the geopolitical world was still frozen by the Cold War. There were no Mormon missionaries proselyting behind the Iron Curtain in post-war Germany or in the nations of the Soviet Union, comprising a sixth of the world’s land surface. Similarly, the Church did not have congregations in mainland China, another communist nation covering much of Asia. Moreover, our religious representatives had barely penetrated the continent of sub-Saharan Africa. Four years later, in 1978, President Kimball would announce a revelation that opened the priesthood door to all worthy men regardless of race or color. “The long-promised day has come when every faithful, worthy man in the Church may receive the holy priesthood, with power to exercise its divine authority, and enjoy with his loved ones every blessing that flows therefrom, including the blessings of the temple,” the First Presidency announced that September.[4] Keeping his own counsel, President Kimball continually oiled the hinges of spiritual history and, in some cases, kicked down the temporal doors with prophetic authority.

The complexion and geographical distribution of the Church have spread and evolved since President Kimball’s clarion call for change in 1974. “That sermon helped transform the Church, releasing energies that almost doubled the missionary force in the next eight years, with similar increases in converts, new stakes organized, and total members. But the new energies were felt in a variety of other ways consistent with the humility and directness as well as sublimity of Spencer W. Kimball,” one scholar documented.[5] A cursory review of the Church’s numerical growth alone is illustrative. By the end of 1974, there were 3,385,909 members, 17,109 full-time missionaries, 675 stakes, 5,951 wards and branches, 113 missions, and just 16 temples around the world.[6] By year-end 1989 (the founding year of the LDS International Society), all of those numbers had more than doubled: 7,300,000 members, 39,739 full-time missionaries, 1,739 stakes, 17,305 wards and branches, 228 missions, and 43 temples.[7] By the end of 2015 (the last year represented by the society’s essays in this volume), those numbers had again nearly doubled in many cases: 15,634,199 members, 74,079 full-time missionaries, 3,174 stakes, 30,016 wards and branches, 418 missions, and 149 temples.[8]

Ongoing global growth continues to be one of the Church’s greatest opportunities (and challenges), just as President Kimball anticipated. Each year, hundreds of thousands of Latter-day Saints visit the reconstructed log cabin in Fayette, New York, where Joseph Smith organized the Church on 6 April 1830. Most are struck by its small size, given the magnitude of the twenty-first-century Church. “It took 117 years—until 1947—for the Church to grow from the initial six members to one million. Missionaries were a feature of the Church from its earliest days, fanning out to Native American lands, to Canada and, in 1837, beyond the North American continent to England,” an official Church resource notes. “The two-million-member mark was reached just 16 years later, in 1963, and the three-million mark in eight years more. This accelerating growth pattern has continued with about a million new members now being added every three years or less.”[9] Through convert baptisms and member births, there are now over fifteen million Latter-day Saints on the membership rolls of the Church.

Back in 1974, a modern-day prophet encouraged all Latter-day Saints to think in ways bigger, broader, and bolder about the ongoing globalization of the Church. In addition to the outreach of the leading quorums and the initiatives of official Church departments, many rank and file members have gathered on occasion to likewise share their best thinking about the past, present, and future of the global Church. The LDS International Society, founded in 1989, is one such group dedicated to thinking deeply about the kingdom of God in these latter days. The society is a collaboration between a number of entities at Brigham Young University, including the David M. Kennedy Center for International Studies, the J. Reuben Clark Law School, the Marriott School of Management, and the Alumni Association. Its stated mission is to foster “communication and contact among experts involved in international business, law, education, humanitarian service, and other professional activities; promotes shared interest and concerns of the society members; and provides support where possible for international programs of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and Brigham Young University.”[10] The women and men of the society include many of the most internationally minded Latter-day Saints who are anxious to help fulfill President Kimball’s earlier call to help all of Heavenly Father’s children enjoy the blessings of the plan of salvation. Most have lived many times in different places around the globe and are eyewitnesses to the growth of the Church.

Since 1990, the society’s primary vehicle and gathering place has been their annual conference held at Brigham Young University each spring. Hundreds of thoughtful Latter-day Saints and their friends meet for a full day of meetings on a global theme and a luncheon to honor one of their members who has made a significant difference on the international scene. Between 2006 and 2015, featured topics have included “International Challenges Facing the Church,” “Meet the Mormons: Public Perception and the Global Church,” “Challenges in Establishing the International Church,” “The Erosion of Religious Liberties—Impact on the International Church,” “The Church and International Diplomacy,” and “The Church and Humanitarian Assistance: In the Lord’s Way.”[11]

As regular attendees ourselves, we believe that some of the best thinking on the Mormon experience beyond North America occurs at the society’s annual gathering, which has resulted in our desire to make some of the best of these conference papers more available to the larger community of Saints and scholars. In a previously published volume for the International Society, Reid has advocated, “international LDS history is Church history. Church members need to realize that much of our most interesting history occurred abroad. We must remember that the ‘restoration’ of the gospel continues to occur every time a new country is dedicated by apostolic authority for proselyting.” He called for a “recommissioning” of Mormon scholars who need to “refocus their scholarly gaze from Palmyra, Kirtland, Nauvoo, and Salt Lake City to Tokyo, Santiago, Warsaw, Johannesburg, and Nairobi. In the coming years, these international cities and their histories will become increasingly important to our sacred history. We need to tell these non-North American stories with greater frequency and with better skill.”[12] This second volume of society speeches follows this called-for trajectory.

We have organized this book into five thematic sections, in which the essays are arranged chronologically by date presented. Part 1, “Poverty and Humanitarian Work,” focuses on the challenge poverty creates in many parts of the world and how the Church is responding to it. In the first essay, “Demographic and Gender-Related Trends: Their Effect on Nations, Regions, and the International System,” Valerie Hudson lays out a case linking declining birth rates and gendercide (female infanticide and female fetus abortion) to misogyny. She argues that the gospel of Jesus Christ holds the key to stopping this downward spiral. In their essay, Tim B. Heaton and Mallory J. Meyer demonstrate the terrible impact poverty has on society. After demonstrating how a growing portion of Church membership is being impacted by poverty, they advocate for Church members to be more supportive towards antipoverty efforts, both national programs and grassroots efforts. Bishop Gérald J. Caussé outlines five principles for helping those in need in his article, “Caring for the Poor and Needy in the Growing International Church.” He suggests the best and most lasting solution is found in living the gospel of Jesus Christ because this solution knows how to adapt to every horizon, every culture, and every political and economic system. In the final essay in this section, “Zion’s Fountains—International and Local,” Sharon Eubank explains that the power of our heritage and our love of God, together with the broad scope of the institutional Church and the individual acts of service performed by millions of members, combine to hasten the work of caring for the poor and the needy around the world today.

In part 2, “Public Perceptions and Relations,” Church leaders and scholars explore how the Church is attempting to position itself and how it is understood by others. Elder Lance B. Wickman, in “The Church in the Twenty-First Century: Public Perceptions and the ‘Man with the Stamp,’” shares examples from Slovakia, China, and Vietnam to illustrate how General Authorities, other Church representatives, and Latter-day Saint private citizens combine their respective efforts in cultivating a positive, public image of the Church with those that play a critical role in obtaining legal recognition. Warner P. Woodworth, in his essay, “Private Humanitarian Initiatives and International Perceptions of the Church,” describes the work of several organizations such as HELP International, Eagle Condor Humanitarian, Ouelessebougou-Utah Alliance, Enterprise Mentors International, and Unitus to illustrate the tremendous good individual acts of global consecration and stewardship can create. Elder Anthony D. Perkins poses the question, “Are we making any progress in Asia?” in his essay “Out of Obscurity: Perspectives from Asia.” He describes five institutional steps that are bringing the Church out of obscurity in Asia. He also gives a contemporary assessment of how the “Mormon Moment” in the US is transferring to Asia and compares how public perceptions have changed over the past sixty years in Taiwan. Lastly, in his article “In the Public Eye: How the Church Is Handling Increased Global Visibility,” Michael Otterson suggests the “Mormon Moment” is not a transitory moment but the latest phase of successive moments spanning the past 182 years. He describes seven categories of contributors.

“Peacemaking and Diplomacy,” part 3, describes efforts to establish the Church globally and to promote peace. In the first essay, “By Persuasion, Long-Suffering, Meekness, and Love: On Diplomacy,” Cory W. Leonard explores the notion of persuasion. He argues that when we combine the virtues of long-suffering, meekness, and love to our persuasive efforts we become better citizens, diplomats, and professionals. Elder Robert S. Wood, in his article “International Diplomacy and the Church,” addresses the challenge of establishing the kingdom of God on earth across various separate political boundaries, each having legal authority within their jurisdictions. He explains that the Church’s intent is to fulfill the Lord’s mandate to take the gospel to all nations while promoting harmony and understanding and not undermining the trust essential to civil society and public peace. In the next essay, “Women’s Weapons of Peace,” Bonnie Ballif-Spanvill outlines five methods which women are using to build a more peaceful world. She asserts that if we can get women to tell stories and do the activities that will develop peace-loving attributes in their children, this will empower them to be peaceful, and it will have a rippling effect through families, villages, and even countries. In the final offering in this section, Robert A. Rees and Gordon C. Thomasson discuss the responsibility we all have to “renounce war and proclaim peace.” In “Dialogue: Religion as Peacemaker,” they admonish all to choose peace, to become peacemakers, and to reject the argument that war is necessary for attaining peace.

In part 4, “Religious Freedom and Oppression,” four experienced professionals discuss the erosion of religious freedoms and how this impacts the Church. In the first essay, “Let Them Worship How, Where, or What They May,” William F. Atkin states that the most serious challenges to the Church in the United States and internationally are the attacks on religious liberty. He urges members of the Church to use their time, talents, and resources to promote and defend religious liberty and freedom of belief for all, particularly for those who are weak, disenfranchised, or otherwise defenseless. Cole Durham outlines several threats to religious liberties around the world in “Protection of Religious Liberties: Current Initiatives.” He then discusses how the International Center for Law and Religion Studies is attempting to promote religious freedoms. In the next essay, “Erosion of Religious Freedom: Impact on Churches,” Michael K. Young discusses disturbing trends within the United States that are eroding religious liberty. In order to stem this tide, he invites us to be attentive, seek allies, act for the right reason, and be vigilant. Hannah Clayson Smith closes this section with “Religious Liberty Initiatives: Preserving the ‘First Freedom’ at Home and Abroad.” She provides numerous examples, categorized under five—themes; religious autonomy, conscientious objection, defamation of religion, religion in the public square, and religious discrimination—to describe attacks on religious liberty within the United States.

In our final section, part 5, “Growth and Globalization,” stories demonstrate challenges and successes in growing the Church. Ted E. Lyon, in “Migration—It’s in Our Blood: Implications for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints,” details the worldwide phenomenon of migration and the way many displaced people are finding their way into The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. While this influx of refugees creates several challenges, Lyon maintains that we have always welcomed refugees and their inclusion enriches the culture of the Church. The next essay from Daniel C. Peterson, “Sources of Tension between the West and the Islamic World,” provides numerous examples that are fueling conflict. He offers a pessimistic view of the future and states there is no recipe for curing an inter-civilizational crisis that rests, to a very large degree, on mutual incomprehension. Elder Cree-L Kofford, drawing on his experiences in Asia, describes in “The Church and the Global Community” various ways the Church has adapted its programs to meet local circumstances. He urges leaders and members of the Church to be cautious when deciding how to implement programs outside the Wasatch Front. Elder Adesina J. Olukanni shares several challenges and successes from Africa in “‘Organize Yourselves According to the Laws of Man’ (D&C 44:4): Ethical Challenges in Establishing the International Church.” He outlines five fundamental principles which have been helpful in navigating the complex environment in Africa. Finally, in the last essay from Elder Dennis B. Neuenschwander, “Challenges, Opportunities, and the International Church,” he outlines his own five fundamental principles that he has found central to the process of expanding and establishing the Church in Eastern Europe.

Acknowledgments

To begin with, we are grateful to the leadership of the LDS International Society for their support of this publishing project of their created content. Many thanks are due to William M. “Mac” Epps, president; Thomas Edgar “Ted” Lyon, executive director; and Cory W. Leonard, assistant director. Board members William F. Atkin, Fred Axelgard, J. Michael Busenbark, John P. “Phil” Colton, Lew W. Cramer, Elizabeth Crook, Wayne D. Crosby, John Dinkelman, W. Cole Durham Jr., Derek Miller, Jeffrey R. Ringer, Robert Edward Snyder, and Jonathan Wood all favored the production of this volume. Both Reid and Wayne have served on the society’s board and have developed meaningful associations with their fellow members. Bill Atkin is to be thanked for his foreword, essay, and cheerleading of this volume.

We also appreciate the following Church leaders, administrators, and scholars for allowing us to reprint their conference papers in this collection of essays. Many thanks to William F. Atkin, Bonnie Ballif-Spanvill, Bishop Gérald J. Caussé, Cole Durham, Sharon Eubank, Timothy B. Heaton, Valerie Hudson, Elder Cree-L Kofford, Cory W. Leonard, Ted E. Lyon, Mallory Meyer, Elder Dennis B. Neuenschwander, Elder Adesina J. Olukanni, Michael Otterson, Elder Anthony D. Perkins, Daniel C. Peterson, Robert A. Rees, Hannah Clayson Smith, Gordon C. Thomasson, Elder Lance B. Wickman, Elder Robert S. Wood, Warner P. Woodworth, and Michael K. Young.

The Religious Studies Center’s leadership team and editorial staff continue to show their commitment to Mormon studies through their print publications and online offerings. In 2008, they published Global Mormonism in the 21st Century, a collection of choice presentations from the first fifteen years of the society’s annual conferences, this volume’s precursor. We appreciate the competence and goodness of publications director Thomas A. Wayment, executive editor R. Devan Jensen, production supervisor Brent R. Nordgren, publications coordinator Joany Pinegar, and the timely and professional assistance of their talented team of student editors: Kimball Gardner, Allyson Jones, Mandi Diaz, Emily Strong, Shannon Taylor, and Leah Emal. The RSC team is committed to excellence in both scholarship and production values, and it shows in their many publications.

Furthermore, we are also continually obliged for the support of the executive leadership of the Church History Department of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, including Elders Steven E. Snow and J. Devn Cornish. Our Church campus colleagues Katrina Cannon, Jo Lyn Curtis, Scott Marianno, R. Mark Melville, Melissa McQuarrie, Erin Steenblik Tanner, Tyler Thorsted, and Kelsi Walbeck each made important editorial contributions to the production of this volume. Moreover, the librarians and archivists of the Church History Library provided helpful guidance and access to needed sources along the way. Together with all of these named individuals, we have created a volume worth careful reading and thoughtful pondering on the global Church.

Finally, we are grateful to be both professional observers and personal participants in this latter-day work of salvation. “We thank thee, O God, for a prophet” like diminutive Spencer W. Kimball, who, as he assumed the presidency of the Church, humbly confided to a fellow Apostle: “I am such a little man for such a big responsibility!”[13] But as Alma taught his son Helaman, “By very small means the Lord doth confound the wise and bringeth about the salvation of many souls” (Alma 37:7). Just imagine what lies ahead for the global Church and President Kimball’s prophetic successors in the next forty years.

Reid L. Neilson

Assistant Church Historian and Recorder

Bountiful, Utah

Wayne D. Crosby

Syracuse, Utah

Notes

[1] Spencer W. Kimball, “When the World Will Be Converted,” Ensign, October 1974, 3–11. His sermon was reprinted (and shortened) as the First Presidency Message in the spring of 1984: “When the World Will Be Converted,” Ensign, April 1984, 3–6.

[2] W. Grant Bangerter, “A Special Moment in Church History,” Ensign, November 1977, 26.

[3] Eugene England, “A Small and Piercing Voice: The Sermons of Spencer W. Kimball,” BYU Studies 25, no. 4 (1985): 82.

[4] Doctrine & Covenants, Official Declaration 2.

[5] England, “A Small and Piercing Voice,” 82–83.

[6] In Conference Report, April 1975, 25; R. Lanier Britsch, “Mormon Missions: An Introduction to the Latter-day Saints Missionary System,” Occasional Bulletin of Missionary Research 3, no. 1 (January 1979): 22.

[7] In Conference Report, April 1990, 27.

[8] In Conference Report, April 2015, 37.

[9] “Growth of the Church,” Mormon Newsroom, http://

[10] LDS International Society brochure.

[11] For a complete list of the last twenty-five years of annual symposiums, see Appendix 2: Past LDS International Society Conferences, 1990–2015.

[12] Reid L. Neilson, “Introduction: A Recommissioning of Latter-day Saint Historians,” in Global Mormonism in the 21st Century, ed. Reid L. Neilson (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, 2008), xii–xv.

[13] Edward L. Kimball, Lengthen Your Stride: The Presidency of Spencer W. Kimball (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2005), 8.