Senator Elbert D. Thomas: Advocate for the World

R. Devan Jensen and Petra Javadi-Evans

R. Devan Jensen and Petra Javadi-Evans, “Senator Elbert D. Thomas: Advocate for the World,” in Latter-day Saints in Washington, DC: History, People, and Places, ed. Kenneth L. Alford, Lloyd D. Newell, and Alexander L. Baugh (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book), 223‒40.

R. Devan Jensen was the executive editor at the Religious Studies Center at Brigham Young University when this was published.

Petra Javadi-Evans was an assistant editor at the Joseph Smith Papers Project.

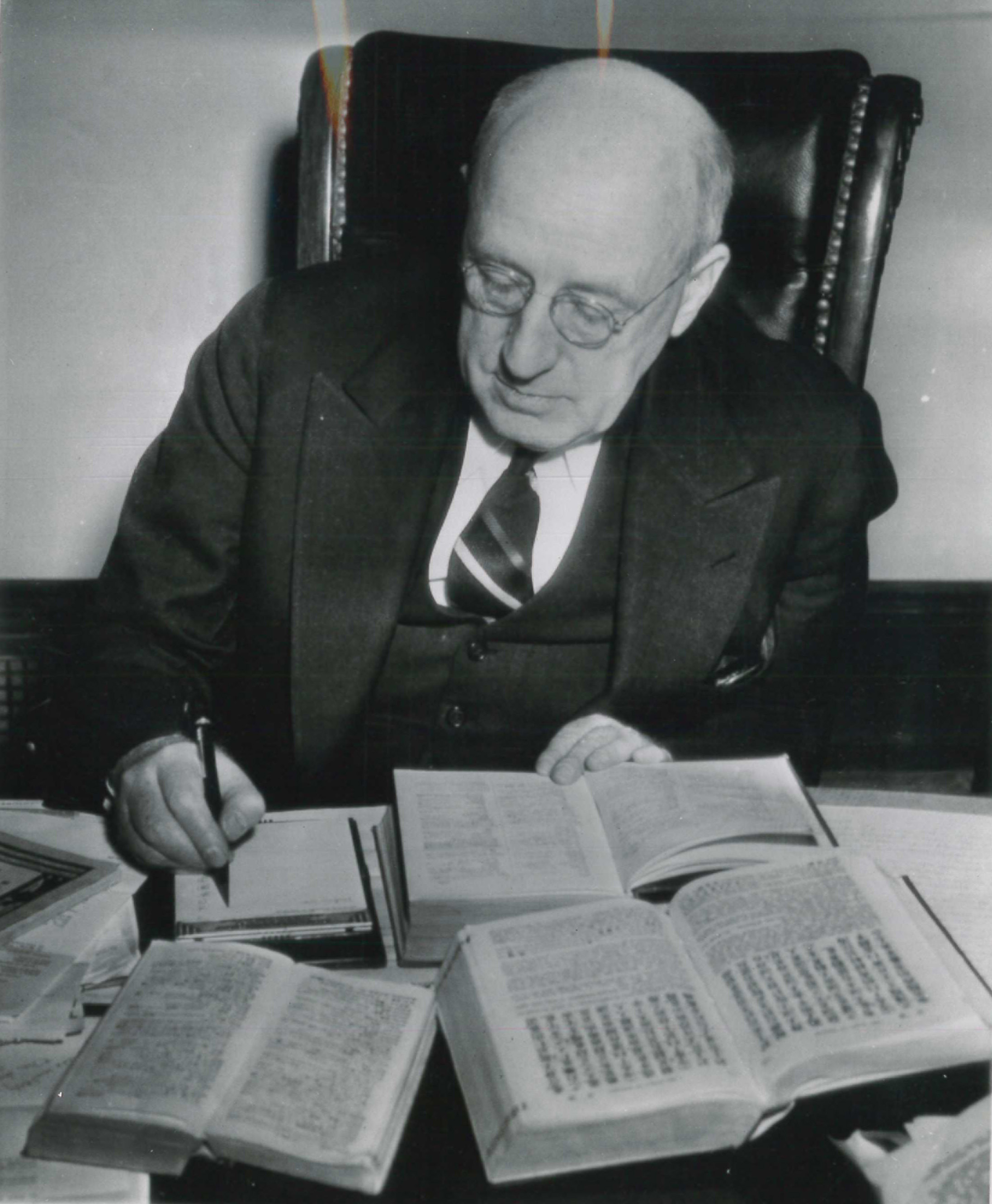

Senator Elbert Thomas, a former missionary to Japan, working on the translation of a script for a shortwave radio broadcast in Japanese beamed from the Pacific Coast to Japan, 11 January 1942. Before him on the desk is an English-Japanese dictionary and other reference books. AP Wire Photo.

Senator Elbert Thomas, a former missionary to Japan, working on the translation of a script for a shortwave radio broadcast in Japanese beamed from the Pacific Coast to Japan, 11 January 1942. Before him on the desk is an English-Japanese dictionary and other reference books. AP Wire Photo.

Utah governor Jon M. Huntsman Jr. designated 8 April 2005 as Elbert Thomas Day to honor the late senator’s role in Washington, DC, during a crucial time in U.S. history.[1] Thomas, a three-term U.S. senator (1933–51), served through much of the Great Depression and through World War II, but by 2005 he was a surprisingly forgotten figure. In addition to his many contributions for U.S. citizens, particularly during World War II, Senator Thomas was an advocate for Jewish refugees, Japanese nationals, and American GIs.[2] His service to his country and to the world should be remembered and honored. This chapter tells the important but overlooked story of Elbert D. Thomas, a Democratic senator who served as a statesman and an effective advocate for world citizens.

Seeds of Advocacy

Elbert Thomas’s advocacy emerged from his membership in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. He grew up in Salt Lake City in the late 1800s, a time of intense persecution and prosecution toward those of his faith because of the Church’s practice of plural marriage. Elbert wrote, “I saw the confiscation of Mormon property and the Mormon leaders disfranchised by the Federal Government.”[3] These experiences spurred him to spend much of his life as a labor advocate and mediator, ensuring that individuals received just and humane treatment from corporations and the federal government.

Elbert was the fifth of twelve children born to Richard and Caroline Thomas, British converts who moved to the United States in 1863.[4] His parents loved the arts, especially the theater. They built a barn and children’s playhouse combination that they called the Barnacle. Elbert was involved in many plays held for the public there. His father hosted conventions and political rallies in the Barnacle as well. Elbert wrote, “My father was always a leading businessman. He was a ‘Sagebrush’ Democrat in that he became a Democrat when the state divided on party lines.”[5] In that era, Democrats and Republicans were both fairly evenly represented in Utah, and Elbert adopted his parents’ party, believing that the federal government could become a powerful force for good to promote the rights and well-being of its citizens.

In 1906 Elbert was commissioned as a second lieutenant in the Utah National Guard. That year his parents moved to a large, beautiful home at 137 North West Temple Street.[6] (That home still stands just west of today’s Conference Center and is on the National Historical Landmark Registry.)

Senator Thomas, who succeeded the veteran U.S. senator Reed Smoot, with his wife, Edna, and daughter, Esther, 13 March 1933. Harris & Ewing Photographic News Service.

Senator Thomas, who succeeded the veteran U.S. senator Reed Smoot, with his wife, Edna, and daughter, Esther, 13 March 1933. Harris & Ewing Photographic News Service.

While attending the University of Utah, Elbert helped found the Amici Fidissimi Society, an organization later affiliated with the Phi Delta Theta fraternity. He participated in the Utah Dramatic Club and began dating Edna Harker, daughter of Benjamin E. and Harriet Bennion Harker. Edna was a popular actress who performed at the Salt Lake Theatre.[7] Later, after graduation, she taught physical education.[8]

Elbert and Edna courted and became engaged, and the two were called on a five-year mission to Japan. After marrying on 25 June 1907, Elbert was set apart by Latter-day Saint Apostles Heber J. Grant and George Albert Smith. Elbert first served as mission secretary, and then in 1910 he began serving as mission president.[9] As he and Edna served, each became fluent in the Japanese language, grew to love the people of Japan, and developed a fascination with international affairs, particularly regarding Asian cultures.[10] There Edna gave birth to their first daughter, Chiyo, who was well-loved by the new parents and fellow missionaries. After returning to the States, Edna gave birth to two more daughters.

The Thomases returned to Utah in 1912. On their way home, they traveled through Europe and visited Turkish-occupied Palestine. There Elbert and Edna pondered the plight of the Jews and the loss of their temple, feeling a spiritual connection with them. Elbert wrote this of their experience:

The evening that Palestine impressed me most was when Mrs. Thomas and I sat on the Mount of Olives and looked across the valley to the place of the temple and the Mosque of Omar. While our baby gathered pebbles, we read the dedicatorial prayer offered by Orson Hyde on October 21, 1841, when the land of Palestine was dedicated by a Mormon elder sent by the Prophet Joseph Smith to dedicate Palestine for the return of the Jews. Here again deep, meaningful, long range spiritual understanding entered my soul. At the time I read the prayer, just twenty years after the dedication of our own temple, a few Jews were returning to Palestine to be buried near Jerusalem. Tel-Aviv was a doubtful venture, for in all there were only sixty or seventy thousand Jews in the Holy Land. Belief in the restoration of Jerusalem is part of my religion.[11]

Back in Utah, Elbert became an instructor of Greek and Latin at the University of Utah and simultaneously worked as the school’s secretary and registrar.[12] He took a leave of absence to attend UCLA, where he earned a PhD in government. Returning to work as a professor at the University of Utah, he taught political science, history, and Asian languages.[13] In 1926 Dr. Thomas, along with other professors, traveled to Europe to study international law and relations at the seat of the World Court in The Hague, Geneva, and Paris. There he delivered a speech titled “World Unity through the Study of History,” arguing that conflicting national interests gave rise to wars, revolts, disease, and famine. He argued that whenever trade is free, peace is inevitable. Biographer Linda Zabriskie noted that, while Dr. Thomas continued to teach at the University of Utah, his “thesis was published as a monograph by the Carnegie Institute and he was accepted as an advanced theorist by academics in international law. Four times the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace recognized Dr. Thomas’s ability and conferred on him the responsibility of teaching courses related to the Far East and Latin America.”[14] His reputation as an international scholar continued to grow when he published his book Chinese Political Thought in 1927.

Having witnessed the start of the Great Depression in 1929, Dr. Thomas argued for greater cooperation between state and federal interests.[15] At that time, Apostle Reed Smoot was serving as a powerful, high-profile Republican U.S. senator from Utah, and he was popular among Church members. In 1930 Senator Smoot cosponsored the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act, increasing duties on almost nine hundred imports. That act triggered retaliatory tariffs from other nations, which unfortunately exacerbated the effects of the Great Depression. Dr. Thomas disagreed with the tariff act and promised his political science students that Senator Smoot could “be defeated.”[16] Dr. Thomas made good on his promise by running for office and defeating Senator Smoot in 1932.

Early Contributions

Elected at the same time as President Franklin D. Roosevelt, during the Great Depression when millions were deprived of work, Senator Thomas moved to Washington, DC. There his family worshipped with fellow Saints at the Washington Chapel on Sixteenth Street. In his spiritual autobiography, he mentioned being inspired by its statue of the angel Moroni as a symbol for taking the gospel of Jesus Christ to the world (after the building was sold, the statue was removed).

Senator Thomas became immersed in New Deal advocacy for U.S. citizens. As chair of the Senate Committee on Education and Labor, he worked to establish the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), a Depression-era work relief program employing millions of young men in environmental projects and national parks.[17] Utah had 116 CCC camps with about two hundred men each, including three camps in Zion National Park that “built and improved many of the Zion Canyon’s trails, created parking areas, fought fires, helped build campgrounds, built park buildings and reduced flooding of the Virgin River.”[18] He coauthored the Fair Labor Standards Act in 1938, which established maximum hours of labor per week, overtime pay, and a minimum wage. He moderated negotiations that resolved a nationwide strike led by the mining industry. And he “helped create the Department of Education and Social Services, the National Science Foundation, and other agencies.”[19] Though his goals often aligned with Roosevelt’s, Thomas sometimes found himself in disagreement with the president.

Advocate for Jewish Refugees

After Adolf Hitler was appointed chancellor of Germany on 30 January 1933, he began oppressing religious minorities in Germany, including Jews and Christians from smaller sects. Early in 1934 President Roosevelt asked Senator Thomas, “Elbert, won’t you tell me what to do in these cases?”[20] In a major address titled “World Unity as Recorded in History” and given in February 1934, Thomas argued for world peace and recognized that Hitler’s hatred of the Jews might threaten that peace: “Hitler and his attack on the Jews is viewed by most as a purely local or national problem. Is it only that? Hitlerism may be classified . . . as a new religion, contesting with the old order. . . . Hitlerism, viewed as a spiritual movement, must of necessity be anti-Jewish.”[21] Within a year, Senator Thomas traveled to Germany with funds from the Oberlander Award in German-American relations.[22] There he met Rudolf Hess, Hitler’s Deputy Führer,[23] and concluded “that the Nazis intended to rule the world.”[24] Returning to Washington, he at first argued for neutrality. In a 1935 National Radio Forum address about the ongoing aggression in Europe, Senator Thomas argued that America “must stay out of war.”[25] However, he transitioned from neutrality to intervention when he learned how the State Department had minimized the gravity of the refugees’ plight. Following the leadership of assistant secretary of state Breckinridge Long, the State Department staunched the flow of European refugees and expressed concerns about spies entering the United States. Because of these concerns, the State Department chose not to fill immigration quotas and tried to stop intelligence about mass murders in Europe from reaching the public.[26] When news about human rights violations finally trickled out in February 1939, Senator Thomas decided to intervene for European refugees by introducing Senate Joint Resolution 67, which would have aided “victims of aggression, sending a clear message to allies while giving aggressors reasons to reconsider their ambitions for territorial conquest.”[27] That resolution failed because of American reluctance to trigger retaliation.

U.S. citizens initially disbelieved accounts of Nazi atrocities toward the Jews, only later coming to understand the seriousness of the situation. “Between June 1941 and May 1945, five to six million Jews perished at the hands of the Nazis and their collaborators,” wrote David S. Wyman. “Germany’s control over much of Europe meant that even a determined Allied rescue campaign probably could not have saved as many as a third of those who died. But a substantial commitment to rescue almost certainly could have saved several hundred thousand of them, and done so without compromising the war effort.”[28] Unfortunately, the U.S. State Department and British Foreign Office chose not to rescue large numbers of European Jews or open Palestine for further Jewish immigration.[29]

Senator Thomas was an avid Zionist and argued throughout his life for the establishment of Palestine as a gathering place for the Jews.[30] On 1 November 1942, on the twenty-fifth anniversary of the Balfour Declaration, Thomas spoke in Carnegie Hall, urging the United States to establish “a Jewish commonwealth in Palestine as one of our war aims and peace aims.”[31]

During the war, Senator Thomas became one of the nation’s most vocal advocates to save Jewish refugees from Nazi-controlled Europe. He found himself in disagreement with President Roosevelt, who wanted to focus on the war effort rather than intervene on behalf of refugees. Dr. Rafael Medoff, founding director of the David Wyman Institute for Holocaust Studies, wrote that Thomas worked closely with “a lobbying group led by Jewish activist Peter Bergson [Hillel Kook]. Thomas signed on to its full-page newspaper ads criticizing the Allies for abandoning European Jewry. He also cochaired Bergson’s 1943 conference on the rescue of Jews, which challenged President Roosevelt’s claim that nothing could be done to help except win the war.”[32]

Senator Thomas then helped advance the Gillette-Rogers congressional resolution by calling for the creation of a government agency to rescue Jews from the Nazis. Senator Tom Connally, the aging chair of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, initially blocked the resolution, and Senator Thomas said, “Wait, one day I’ll preside and it will pass unanimously.”[33] When Connally became ill, Thomas introduced the measure, and it did pass unanimously. Bergson noted that Thomas “was a very much admired man in the Senate. . . . He was a very religious man, he was a real Mormon—a real practicing religious man. . . . And the fact that he stood, and Johnson stood, and Gillette, made a small but very strong core.”[34]

That effort snowballed into success. In January 1944, after Treasury secretary Henry Morgenthau Jr. learned that State Department officials had hindered chances to rescue Jewish refugees, Morgenthau and his staff approached President Roosevelt with a report that the State Department had concealed news of the European refugee crisis. Morgenthau told the president, “You have either got to move very fast, or the Congress of the United States will do it for you.”[35] With just days to go before the full Senate would act on the resolution, Roosevelt used executive authority to form the agency they had demanded—the War Refugee Board.

Dr. Medoff later summed up the contributions of this board: “Although understaffed and underfunded, the board agents persuaded a young Swede, Raoul Wallenberg, to go to German-occupied Budapest in 1944, playing a major role in saving more than 200,000 Jews during the final fifteen months of the war.”[36] Dr. Medoff wrote of Thomas, “At a time when too many people and governments turned their backs on Hitler’s Jewish victims, Senator Elbert D. Thomas was a voice of courage and humanitarianism on Capitol Hill. He played a major role in the campaign leading to the creation of the War Refugee Board, a U.S. government agency that helped rescue over 200,000 Jews from the Holocaust. Every resident of Utah can take special pride in the knowledge that their Senator spoke out when others were silent.”[37]

Advocate for the War Effort in Utah

U.S. indifference toward the war transformed into anger and retribution when Japan attacked U.S. forces at Hawaii’s Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941. Based on his visit to Germany and firsthand witness of German aggressions, Senator Thomas had already begun war preparations and had continued those efforts. In 1935, with Thomas’s support, Congress had passed the Wilcox-Wilson Bill authorizing a permanent air corps station in the Rocky Mountains.[38] Thomas promoted a Works Progress Administration project to rebuild the Ogden Arsenal in Sunset, Utah, expanding it to include several new structures. By the time the United States entered the war in 1941, the arsenal had grown to be a vital storage site for military vehicles and ammunition.[39] With Thomas’s support, the military built or enhanced more installations in Utah such as the Hill Field Air Depot in Davis County, Utah General Depot in Ogden, Wendover Army Air Base, Kearns Army Air Base, Dugway Proving Ground, Tooele Army Depot, Deseret Chemical Depot near Tooele, Bushnell General Military Hospital in Brigham City, and Clearfield Naval Supply Depot.[40] Geneva Steel Mill in Utah County was also part of the war effort, and Thomas persuaded administrators to complete the project.[41] These military installations boosted the war effort and Utah’s booming wartime economy.

Advocate for Japanese Nationals

Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor had launched a wave of anger and fear toward people of Japanese heritage. Because of Thomas’s fluency in Japanese and his extensive knowledge of Japanese politics and culture, the Office of War Information invited him to broadcast monthly radio addresses across the United States and to Japan.[42] On the seventh of each month, from December 1941 until the end of the war, Thomas broadcast messages to Japan urging citizens to overthrow their imperialist leaders. Of those messages, he said,

I had but one theme, and that was that Japan was ruining herself, because she had turned apostate to the best ideals that Japanese civilization had developed. I knew how the Japanese constitution worked. I knew that the generals in the field were absolute. They could not be controlled by the home government. I knew, therefore, that we had to have a constitutional surrender under the auspices of the Emperor. . . . The opposition to my ideas by those who wanted to destroy and bring anarchy in Japan, hurt me in much the same way all prejudicial opposition has hurt me. But in this activity, as in my religious activity, I was sustained by a sense of knowing that I was right.[43]

Senator Thomas appealed to Japanese nationals with clear, logical, and passionate arguments, urging them to overthrow their tyrannical military. His monthly messages prompted Japanese wartime leaders to identify Senator Thomas as a public enemy, but today’s Japanese scholars honor his role in promoting peace and understanding.[44]

In his messages to U.S. citizens, Senator Thomas sought to promote understanding of Japanese culture and politics,[45] but fear and mistrust of the Japanese continued to grow until February 1942, when President Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, which forced 110,000 people of Japanese ancestry to relocate to ten internment camps based on their race, not on an accusation of a crime.[46] In this area, Roosevelt overruled Thomas’s objections. Historian Nancy J. Taniguchi described this troubling time in Utah:

Voluntary exclusion from the West Coast remained open until March 30, 1942, allowing Oakland resident Fred Isamu Wada, whose wife Masako was from Ogden, to negotiate a lease of almost 4,000 acres near Keetley, Wasatch County. Soon ninety relocated American Japanese grew food there for the war effort. Another group of forty families leased 1,500 acres to raise sugar beets near Green River despite anti-Japanese protests by Emery County residents.

Some businesses welcomed American Japanese employees; others were fired and some had radios, cameras, and hunting rifles confiscated by municipal authorities. Senator Thomas, a mentor to Mike Masaoka [national secretary of the Japanese Americans Citizens League], tried to mitigate the effects of wartime hysteria.[47]

The U.S. created a relocation center near Delta, Utah, called the Topaz War Relocation Center, also known as the Central Utah Relocation Center (Topaz). Living conditions there were difficult, with both extreme hot and cold temperatures in the uninsulated barracks. Contrary to the overall U.S. position, Senator Thomas argued for more humane treatment and understanding of Japanese people at home and overseas, but the tide of popular opinion had turned, and Thomas was largely powerless in this area.[48]

Advocate for the End of the War

Informal photo of Elbert D. Thomas at Washington, DC, 7 June 1940. Harris Ewing Photographic News Service.

Informal photo of Elbert D. Thomas at Washington, DC, 7 June 1940. Harris Ewing Photographic News Service.

As a member of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, Thomas was aware of the development of the atomic bomb. He wrote about this project in his autobiography: “I could never rid myself of the idea that ultimate victory can only come through a change in men’s hearts and ideas. More with that zeal than the idea to destroy I supported the experimentation which resulted in the atom bomb.”[49] President Roosevelt died while U.S. troops were advancing on Japan, and President Harry S. Truman authorized the use of atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Senator Thomas was horrified with the devastation. Historian Haruo Iguchi summarized Thomas’s efforts during this crucial period:

Thomas made 44 monthly broadcasts to Japan during wartime, in addition to his weekly commentaries shortly before Japan’s surrender. His senatorial colleagues, impressed by his activities, urged him to insert some of his messages in the Congressional Record. . . . In his August 7 [1945] broadcast Thomas urged the Japanese to overcome the resistance of the Japanese militarists to accept the Potsdam Declaration or face another destruction such as that which befell Hiroshima; Thomas cited some potential cities that could suffer from future nuclear destruction if Japan did not immediately surrender. Thomas urged Japanese listeners to stay away from the cities cited as well as others that produced military goods and served as military installations, including Nagasaki. Thomas argued the U.S. had three “huge plants” capable of producing many atomic bombs that unleashed the same destructive energy as that emitted by the sun. Thomas emphasized that both the U.S. and the U.K. had no intention of enslaving the Japanese population and only the militarists stood in the way of Japan’s accepting the terms expressed in the Potsdam Declaration.[50]

Only days after the bomb was dropped on Nagasaki on 9 August, Emperor Hirohito announced Japan’s surrender on 15 August.

Advocate for American GIs

As a ranking member of the Senate’s Military Affairs Committee, Senator Thomas amended the Selective Service Act so that the jobs GIs had had before entering the armed forces would be kept open in anticipation of the GIs’ eventual return. He promoted the role of women in the U.S. Army by making the Women’s Army Corps an integral part of the army rather than an auxiliary. Toward the end of the war, he coauthored the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act, which commonly became known as the GI Bill. He wrote the education portion that helped thousands of soldiers attend colleges and universities after the war.[51] The bill offered veterans government-financed education, government-guaranteed loans, job-finding assistance, hospital benefits, and a year of unemployment compensation.[52] Many benefits secured by this bill continue to this day, assisting veterans to transition to civilian life—a lasting tribute to his advocacy for veterans.

Senator to High Commissioner

Ironically, Senator Thomas’s advocacy for world citizens led to his defeat. In 1944 Senator Thomas published a book titled The Four Fears that argued for global peace and against fear-based nationalism. In 1945 Senator Thomas became “a leader in bringing into being the United Nations.”[53] He advocated policies that favored global interests over purely national interests. These views made him unpopular with some during the “Red Scare” era of the 1950s. “In the early months of 1950,” wrote Richard Swanson, “Senator Joseph McCarthy of Wisconsin embarked on what may be recorded as a most energetic attempt to rid the United States of persons linked, even remotely, with Communist sympathies or associations.” He added, “Capitalizing on the prevalent mood of disgust with foreign policy failures, the junior senator offered the oversimplified explanation that Communists had infiltrated high-level State and Defense Department positions.”[54] Swanson wrote that “the use of slanderous insinuations to give the impression that a politician was pro-Communist was widespread and effective in Utah,” and “the first victim of this deluge of McCarthyism was the state’s senior senator, Democrat Elbert Thomas.”[55]

During the 1950 senatorial campaign, attack ads “accused [Thomas] of presiding at Communist meetings and of sponsoring leftist organizations. He was cartooned as a puppet of the Communists and the radical unionists,” and “the Republican candidate, Wallace Bennett, did nothing to deter the attacks,” wrote historian Richard D. Poll.[56] Fellow Utah senator Arthur Watkins also joined the attacks; ironically, he later chaired the Senate committee censuring McCarthy.[57] Even though Senator Thomas was not a Communist, his critics “publicized enough implicative insinuations and accusations” that Thomas was defeated in the election cycle of 1950.[58]

The following year, Elbert Thomas was appointed high commissioner of the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands, the highest civilian authority that presides over a vast stretch of the Pacific Ocean. While serving in that position, he supervised humanitarian aid and rebuilding efforts in Micronesia.[59] On 11 February 1953, he passed away in Honolulu, Hawaii, serving his country until the very end. His family received hundreds of letters of condolence from global leaders, including the U.S. president and members of Congress. They appropriately remembered and honored Elbert D. Thomas, an effective Washington statesman and advocate for world citizens.

Notes

[1] David S. Wyman Institute for Holocaust Studies, “Utah Senator Honored for Holocaust Rescue Efforts” (press release), 5 April 2005, Wyman Institute (website).

[2] Where did the term GI come from? In the early twentieth century, GI—meaning galvanized iron—was stamped on military trash cans and buckets often made from that material. During World War I, the term began to refer to all things Army related. GI was then reinterpreted as “government issue” or “general issue.” World War II soldiers began referring to themselves as GIs. Patricia T. O’Conner and Stewart Kellerman, Origins of the Specious: Myths and Misconceptions of the English Language (New York: Random House, 2009), 72.

[3] “Elbert D. Thomas,” in Thirteen Americans: Their Spiritual Autobiographies, ed. Louis Finkelstein (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1953), 144.

[4] Joyce S. Goldberg, “FDR, Elbert D. Thomas, and American Neutrality,” Mid-America 68 (January 1986): 35.

[5] Elbert D. Thomas to Frank Jonas, 13 September 1943, Elbert D. Thomas Papers, 1933–1950, MSS 129, box 1, 1, Utah State Historical Society. The Salt Lake Tribune coined the derisive term “Sagebrush Democracy” to refer to Utah’s efforts in the late 1880s to join with the national Democratic movement.

[6] Linda Muriel Zabriskie, “Resting in the Highest Good: The Conscience of a Utah Liberal” (PhD diss., University of Utah, 2014), 18.

[7] “Miss Edna Harker of the Washington,” Salt Lake Tribune, 18 January 1903; “Dramatic Club University of Utah,” Salt Lake Tribune, 14 February 1904; “The University Dramatic Club Is Booked for ‘Niobe,’” Truth (Salt Lake City), 24 March 1906, 6.

[8] “Mrs. Thomas’ Funeral Set for Tomorrow,” Washington Post, 1 May 1942.

[9] Zabriskie, “Resting in the Highest Good,” 19.

[10] Goldberg, “FDR, Elbert Thomas, and American Neutrality,” 36.

[11] “Elbert D. Thomas,” 138.

[12] Goldberg, “FDR, Elbert Thomas, and American Neutrality,” 36.

[13] Sharon Kay Smith, “Elbert D. Thomas and America’s Response to the Holocaust” (PhD diss., Brigham Young University, 1992), 72.

[14] Zabriskie, “Resting in the Highest Good,” 55–56.

[15] Thomas to Jonas, 23 September 1943, 1.

[16] Elbert D. Thomas, as quoted in Ralph Hann, Tomorrow and Thomas (pamphlet, n.d., reprinted from Reader’s Scope magazine), 1.

[17] John A. Salmond, “The Fight for Permanence,” chap. 9 of The Civilian Conservation Corps, 1933–1942: A New Deal Case Study (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1967).

[18] “Civilian Conservation Corps in Utah,” Mountain West Digital Library; “Civilian Conservation Corps,” National Park Service (website).

[19] “Helping Common People: Elbert Thomas (1883–1953),” Utah State History (website).

[20] “Elbert D. Thomas,” in Thirteen Americans, 151.

[21] Elbert D. Thomas, “World Unity as Recorded in History,” International Conciliation, no. 297 (February 1934): 40, 50.

[22] Zabriskie, “Resting in the Highest Good,” 56.

[23] Hann, Tomorrow and Thomas, 3.

[24] Smith, “Elbert D. Thomas,” 76.

[25] “Neutrality Plea Made by Thomas,” Evening Star (Washington, DC), 13 September 1935, A-6.

[26] “Breckinridge Long,” Holocaust Encyclopedia, https://

[27] Goldberg, “FDR, Elbert D. Thomas, and American Neutrality,” 35.

[28] David S. Wyman, The Abandonment of the Jews: America and the Holocaust, 1941–1945 (New York: Pantheon Books, 1984), ix.

[29] Wyman, Abandonment of the Jews, x.

[30] Rafael Medoff, “Senator Elbert D. Thomas: A Courageous Voice against the Holocaust” (Washington, DC: David S. Wyman Institute for Holocaust Studies, 2004), Wyman Institute (website). For more about the War Refugee Board, see Rebecca Erbelding, Rescue Board: The Untold Story of America’s Efforts to Save the Jews of Europe (New York: Anchor Books, 2018).

[31] Elbert D. Thomas, “The Hillsides and Valleys of Palestine Bloom Again,” Congressional Record: Proceedings and Debates of the 77th Congress, Second Session (1942), 1.

[32] Rafael Medoff, “A Mormon in the Holy Land,” Los Angeles Times, 29 July 2012.

[33] Rafael Medoff, Blowing the Whistle on Genocide: Joseph E. DuBois, Jr., and the Struggle for a U.S. Response to the Holocaust (West Lafayette, IN: Purdue University Press, 2009), 62.

[34] David S. Wyman, “The Bergson Group, America, and the Holocaust: A Previously Unpublished Interview with Hillel Kook/

[35] Medoff, Blowing the Whistle on Genocide, 63.

[36] Medoff, “Mormon in the Holy Land.”

[37] David S. Wyman Institute for Holocaust Studies, “Utah Senator Honored for Holocaust Rescue Efforts.”

[38] Thomas G. Alexander and Bob Folkman, “Utah’s Legacy of U.S. Military Installations,” Pioneer 65, no. 3 (2018): 50.

[39] Alexander and Folkman, “Utah’s Legacy of U.S. Military Installations,” 47–48.

[40] Alexander and Folkman, “Utah’s Legacy of U.S. Military Installations,” 50–55; “Legislative Record of Senator Elbert D. Thomas of Utah with Special Relation to America’s Position in the World Today,” Legislative Record, 1907–1912, 1932–1950, Elbert D. Thomas Papers, 1933–1950, MSS B 129, box 1, folder 1, Utah State Historical Society.

[41] “Industry and Utah,” Legislative Record, 1907–1912, 1932–1950, Elbert D. Thomas Papers, 1933–1950, MSS B 129, box 1, folder 1, Utah State Historical Society.

[42] Elbert D. Thomas to Frank H. Jonas, 13 September 1943, Elbert D. Thomas Papers, Utah State Historical Society.

[43] “Elbert D. Thomas,” in Thirteen Americans, 135–36.

[44] See, for example, Haruo Iguchi, “Elbert D. Thomas: Forgotten Internationalist Missionary, Scholar, New Deal Senator, Japanophile, and Visionary,” Nanzan Review of American Studies 29 (2007): 115–23; Haruo Iguchi, “Senator Elbert D. Thomas and Japan,” Journal of American & Canadian Studies 25 (March 2007): 75–104, http://

[45] “Ex-Senator Elbert D. Thomas, Pacific Commissioner, Dies,” Evening Star (Washington, DC), 12 February 1953, A-26, Elbert D. Thomas Papers, 1933–1950, MSS B 129, box 225, obits, 1953, Utah State Historical Society.

[46] Helen Z. Papanikolas and Alice Kasai, “Japanese Life in Utah,” in The Peoples of Utah, ed. Helen Z. Papanikolas (Salt Lake City: Utah State Historical Society, 1976), 352–53.

[47] Nancy J. Taniguchi, Discover Nikkei, 27 February 2008.

[48] Papanikolas and Kasai, “Japanese Life in Utah,” 358.

[49] Elbert D. Thomas, “Spiritual Autobiography of Elbert D. Thomas” (draft prepared for Rabbi Louis Finkelstein, Institute for Religious and Social Studies), spiritual autobiography and correspondence, 1949–1950, Elbert D. Thomas Papers, 1933–1950, MSS B 129, box 1, folder 2, Utah State Historical Society.

[50] Iguchi, “Senator Elbert D. Thomas and Japan,” 82–83.

[51] Smith, “Elbert D. Thomas,” 176.

[52] “Thomas and the Veterans,” in Elbert D. Thomas: Your United States Senator (pamphlet, 1944).

[53] “Memorial Addresses on the Floor of the United States Senate,” 13 February 1953, in H. L. Marshall, comp., A Memorial to Elbert Duncan Thomas: United States Senator from Utah, High Commissioner, Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands (Salt Lake City: n.p., 1956), 71, Church History Library.

[54] Richard Swanson, “McCarthyism in Utah” (master’s thesis, Brigham Young University, 1977), 1.

[55] Swanson, “McCarthyism in Utah,” 99.

[56] Richard D. Poll, David E. Miller, Eugene E. Campbell, and Thomas G. Alexander, eds., Utah’s History (Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Press, 1978), 518.

[57] Swanson, “McCarthyism in Utah,” 111.

[58] Swanson, “McCarthyism in Utah,” 101.

[59] R. Devan Jensen, “Micronesia’s Coming of Age: The Mormon Role in Returning Micronesia to Self-Rule,” Pacific Asia Inquiry 7, no. 1 (Fall 2016): 46.