The Revelatory Sources of Latter-day Saint Petitioning

Jordan T. Watkins

Jordan T. Watkins, “The Revelatory Sources of Early Latter-day Saint Petitioning,” in Latter-day Saints in Washington, DC: History, People, and Places, ed. Kenneth L. Alford, Lloyd D. Newell, and Alexander L. Baugh (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book), 29‒50.

Jordan T. Watkins was an assistant professor of Church history and doctrine at Brigham Young University when this was written.

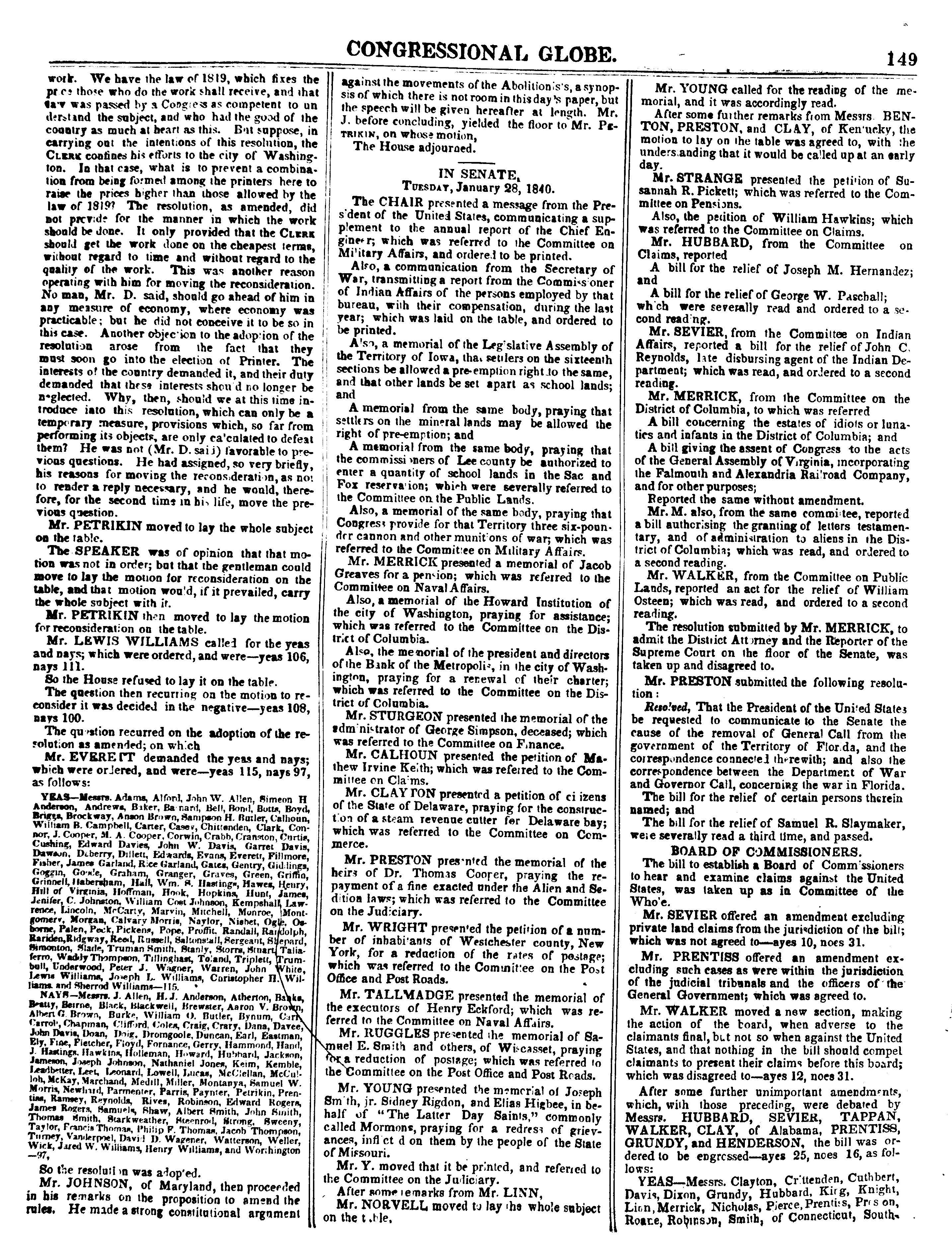

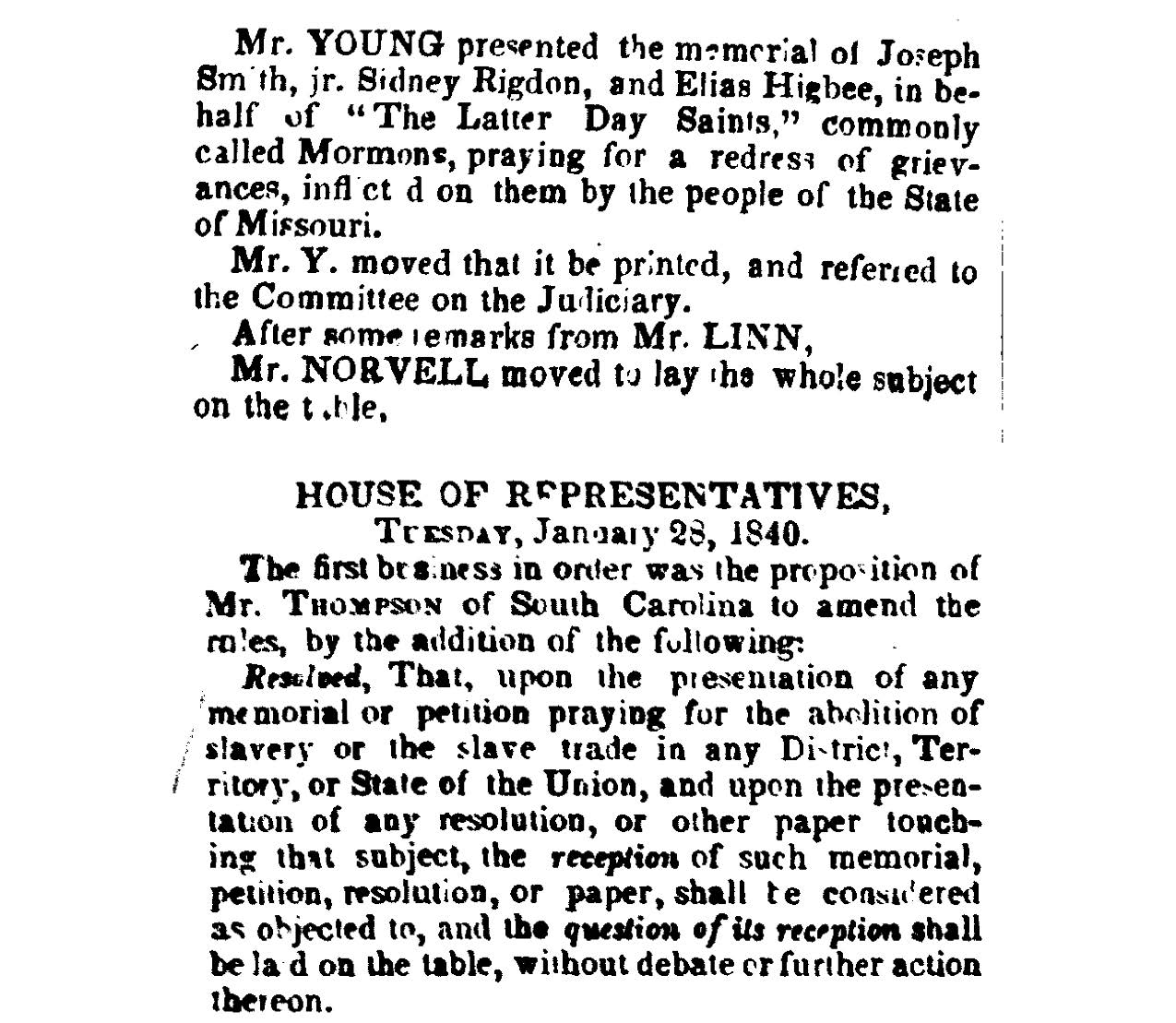

Coverage of congressional discussions about the Latter-day Saints memorial and abolition petitions in the Congressional Globe, 28 January 1840. Library of Congress.

Coverage of congressional discussions about the Latter-day Saints memorial and abolition petitions in the Congressional Globe, 28 January 1840. Library of Congress.

In December 1833, the Lord instructed members of the Church of Christ to petition government for assistance. This instruction came soon after Joseph Smith learned that mobs had driven members from their homes in Jackson County, Missouri. In commanding those members to seek governmental support, the Lord identified the Constitution as the inspired legal basis for their petition efforts. This revelation made sacred both the Constitution and the act of seeking redress.[1]

But if that act was sacred, it also was freighted with political meaning. While the revelation came as a direct response to the particular circumstances in Missouri, it also appeared in the midst of a charged national debate over slavery. The slavery issue overshadowed the era’s other political concerns, including congressional consideration of Church members’ petition efforts. During the mid-1830s, when abolitionists flooded Congress with petitions, anxious Southern politicians led a successful charge to stem the tide. Southern fears of federal meddling with their peculiar institution stood to undermine the prospect of federal intervention in Missouri and on behalf of the Missouri members.

The divine direction to petition seemed doomed by human failure, but Smith’s 1833 revelation anticipated governmental indifference and warned that the Lord would “come forth out of his <hiding> place & in his fury vex the nation.”[2] This checked the members’ reliance on government and even qualified their view of the Constitution as sacred. In other words, by promising godly retribution in the face of human failure, the same source that instructed members to cherish the Constitution and petition government discouraged them from fully trusting in those institutions.

In the pages that follow, I identify the divine origins of early Latter-day Saint petition efforts and outline the ways in which political debates over slavery undermined those efforts. I also track how the very revelation that sanctioned the members’ constitutionalism and commanded their petitioning directed them to look to God when those petition efforts failed. These developments occurred in relationship to the Missouri members’ experiences and the Saints’ petition efforts in the District of Columbia. The failure of these efforts encouraged a crucial change in approach. While members continued to petition the government throughout Smith’s life, in the 1840s he shifted their focus from human legislatures to the divine lawmaker. The members’ early acceptance of the revelatory command to petition anticipated this late development; in relying on the Lord’s direction about human government, Smith’s followers demonstrated their ultimate loyalty to God’s legislation.

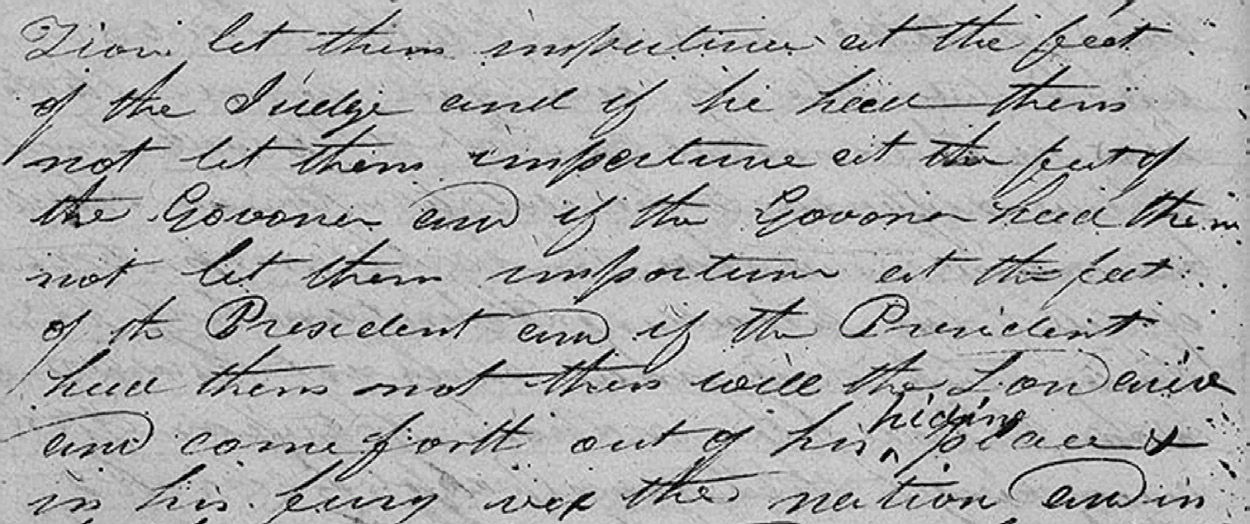

Revelation indicating that the Lord had established the Constitution and instructing the members to appeal to government for assistance, 16–17 December 1833, Revelation Book 2, Kirtland Revelation Book, Revelations Collection, ca. 1829–1876. Church History Library

Revelation indicating that the Lord had established the Constitution and instructing the members to appeal to government for assistance, 16–17 December 1833, Revelation Book 2, Kirtland Revelation Book, Revelations Collection, ca. 1829–1876. Church History Library

In the 1830s, members sacralized the Constitution. The process by which they envisioned the Constitution as sacred both corresponded to and diverged from broader developments. The nation’s founding legal document was not born as the Constitution. At the time of its ratification, James Madison thought of the document less as a complete legal text and more as an imperfect system of government. However, over the course of the next decade, congressional debate recast the document as fixed, static, and even sacred.[3] The generation that followed the Founders adopted and advanced this view. Indeed, the passage of time and the passing of the founding generation bestowed a new sacredness on the Constitution.

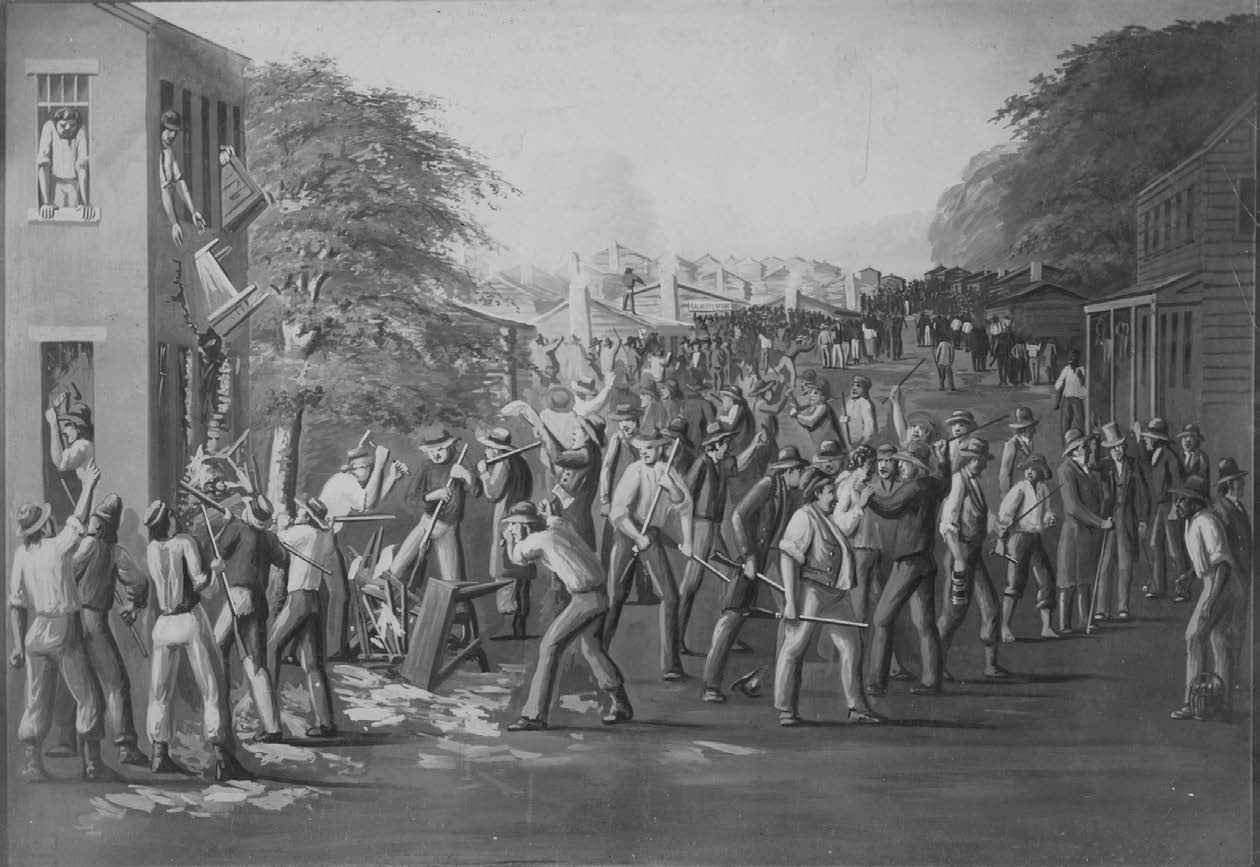

Church members sacralized the Constitution while falling victim to some Southerners’ insecurities about their slave property. Although the Missouri members who opposed slavery did little to publicize their views, in the summer of 1833 a Jackson County mob cited perceived antislavery sentiment in order to justify the destruction of the Church’s press and the tarring and feathering of Bishop Edward Partridge and Church member Charles Allen. News of rising tensions troubled Smith, whose revelations had promised the establishment of a millennial Zion.[4] In response to his concerned cries, the Lord directed Missouri members to uphold “constitutional” law.[5] A few weeks later Smith wrote from Kirtland, urging members to remain in Jackson County. He also prophesied that “god will send Embasadors to the authorities of the government and sue for protection and redress.”[6]

C. C. A. Christensen, Mobbers Raiding Printing Property Store at Independence, Mo., July 20, 1833. Church History Library.

C. C. A. Christensen, Mobbers Raiding Printing Property Store at Independence, Mo., July 20, 1833. Church History Library.

Smith’s followers recognized that prophetic success required human effort. In September, Missouri Church leaders petitioned Governor Daniel Dunklin. Introducing themselves as “citizens of the republic . . . residents of Jackson county” and “members of the church of Christ,” they laid claim to “rights, privileges, immunities and religion, according to the Constitution.” The petitioners informed Dunklin that, based on the perceived threat of losing land and slaves, Jackson County residents had destroyed the petitioners’ property and warned them that any effort to obtain redress would be met with violence. The members argued that such intimidation jeopardized the republic as a whole, noting that when “the poorest citizen’s person, property or rights and privileges, shall be trampled upon by a lawless mob with impunity, that moment a dagger is plunged into the heart of the Constitution.” They then petitioned Dunklin to raise troops to help them defend their rights, sue for damages, and try the mob “for treason.”[7] This marked the beginning of a Latter-day Saint constitutionalism forged in the fires of religious persecution.

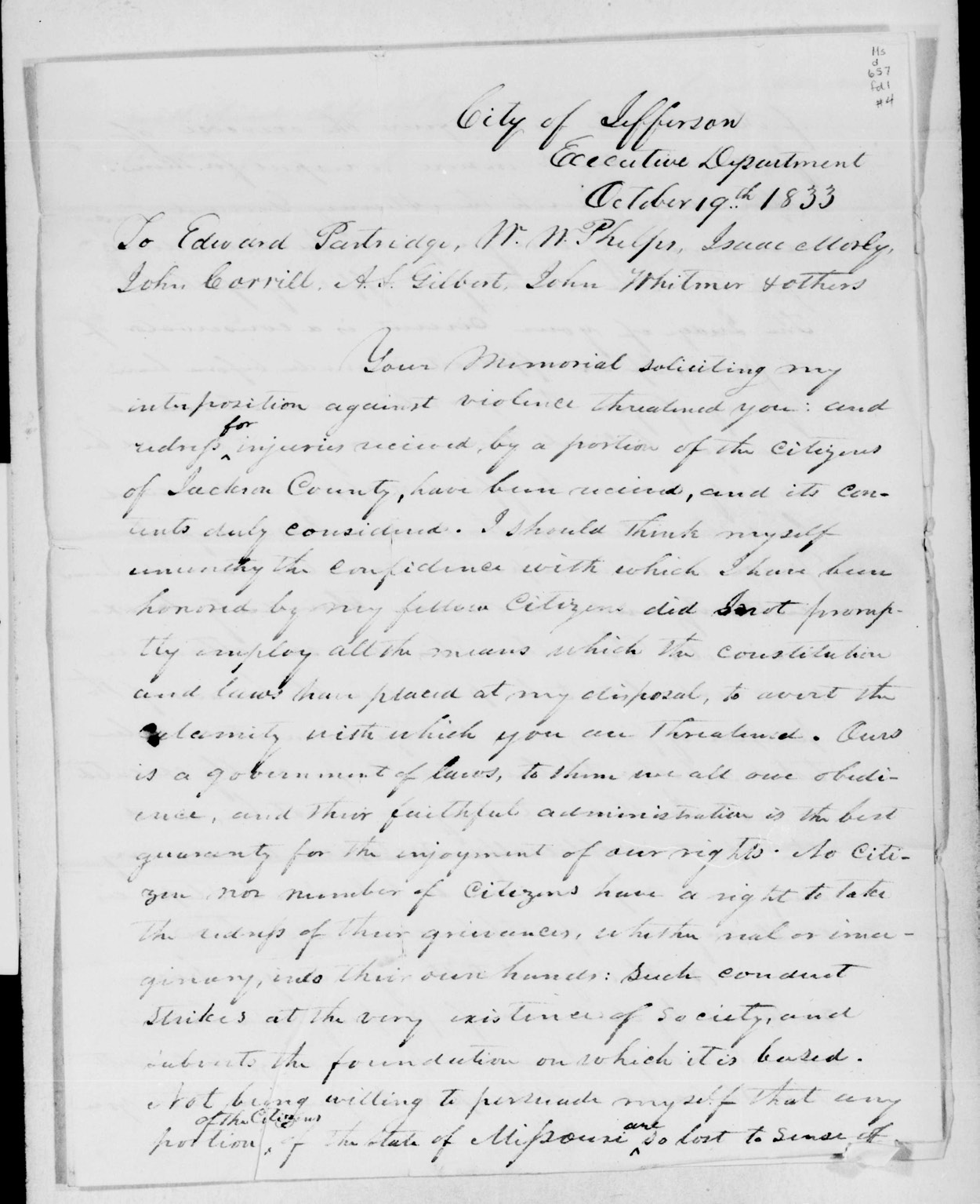

Church members had no reason to believe that their petition would fail. In his response, Dunklin wrote, “I should think myself unworthy the confidence with which I have been honored by my fellow citizens did I not promptly employ all the means which the Constitution and laws have placed at my disposal, to avert the calamity with which you are threatened.” After referencing what seemed to be wide-ranging executive powers, Dunklin proceeded to encourage a narrow judicial solution. He advised the downtrodden members to take their case before the local circuit judge. If that course failed, he explained, then “my duty will require me to take such steps as will enforce a faithful execution” of the laws.[8]

Letter from Governor Daniel Dunklin to Church leaders in Missouri, 19 October 1833. W. W. Phelps Collection of Missouri Documents, 1833–1837, Church History Library

Letter from Governor Daniel Dunklin to Church leaders in Missouri, 19 October 1833. W. W. Phelps Collection of Missouri Documents, 1833–1837, Church History Library

Church leaders immediately hired four lawyers, which infuriated local residents who then renewed attacks on Church properties and drove members from their homes.[9] In early December 1833, Church leaders again petitioned Dunklin, asking him to help them secure assistance from “the militia of the State, if legal, or . . . a detachment of the United States Rangers.”[10]

While Missouri members sent off another petition, news of the mob’s renewed attacks arrived in Kirtland. The distraught Smith again instructed members to retain their lands and use every “lawful means to obtain redress.”[11] Writing first descriptively and then prophetically, he noted, “When the Judge fails you, appeal unto the Executive, and when the Executive fails you, appeal unto the President, and when the President fails you . . . continue to weary” God, who “will not fail to exicute Judgment upon your enemies.”[12] Smith was encouraging members to exhaust all legal means, but he was also reminding them to place their ultimate trust in God.

In less than a week, Smith’s instruction gained the backing of a revelation. The Lord explained that his people “had been afflicted and persecuted” because of their “jar[r]ings and contentions.”[13] Even still, he offered them mercy and promised vengeance.[14] The Lord explained that the members had a role to play in the divine calculus; they had to use the right of petition to secure the nation’s condemnation. While giving this instruction, the Lord identified himself as the source of the Constitution. In urging members to “continue to importune for redress and redemption by the hand of those who are placed as rulers and are in authority over you,” the Lord explained that he had “established the constitution . . . by the hands of wise men whom” he had “raised up unto this very purpose.”[15] While an earlier revelation had commanded obedience to constitutional law, this revelation traced the origins of the Constitution to a divine source. This encouraged a shift among members from constitutional adherence to constitutional reverence.

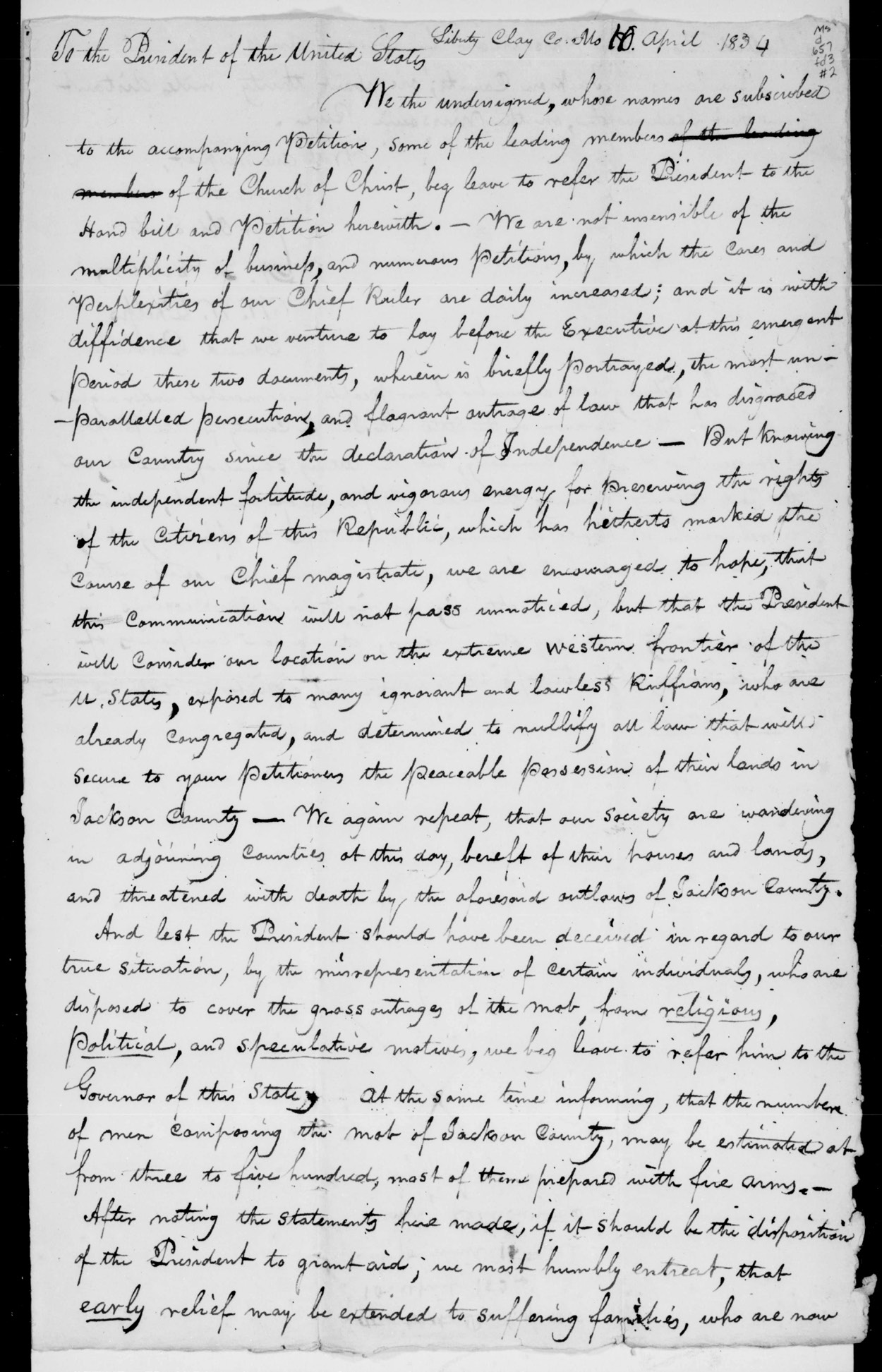

Petition to President Andrew Jackson, 10 April 1834. W. W. Phelps Collection of Missouri Documents, 1833–1837, Church History Library

Petition to President Andrew Jackson, 10 April 1834. W. W. Phelps Collection of Missouri Documents, 1833–1837, Church History Library

However, the same revelation anticipated the failure of the members’ petition efforts and signaled the limits of the Constitution. Comparing “the children of Zion” to the woman who petitioned the unjust judge, as recorded in Luke,[16] the Lord instructed the members to seek redress “at the feet of the judge if he heed them not let them impertune at the feet of the Govoner and if the Govoner heed them not let them importune at the feet of the President.” As in Smith’s letter, the revelation anticipated government inaction and promised godly retribution: “And if the President heed them not then will the Lord arise and come forth out of his <hiding> place & in his fury vex the nation.”[17] The very revelation that gave divine sanction to the members’ constitutionalism reminded them that God was the supreme source of justice. It implied that they should not let inspired writings and rights take the place of the actual source of inspiration.

Smith’s revelation proved prophetic. In February 1834, Dunklin responded to the Missouri members’ new petition and again told them that he would “do every thing in [his] power, consistent with a legal exercise of them, to afford your society” redress. His qualification mattered more than what it qualified; as governor, Dunklin explained, he could not send a militia to protect them. While state laws allowed him to summon a militia in emergencies, he did not believe the members’ situation met the legal requirements, and though the President of the United States could call upon him to send forth a militia, no such request had been made.[18] The governor’s letter must have frustrated the Missouri members, but Smith’s revelation had prepared them for the disappointment and instructed them about how to proceed.

A few months later, in April, “members of the Church of Christ” followed divine instruction by petitioning President Andrew Jackson. They explained that although they were “almost wholly native born Citizens,” they had been deprived of “those sacred rights guaranteed to every religious sect.” Borrowing and highlighting a term Governor Dunklin had used, they argued that the hostilities had created an “unprecedented emergency in the history of our Country.” The petitioners then observed that “the powers vested in the Executive of this State appear to be inadequate,” and asked the president to call on the governor to provide a protective force.[19]

The petitioners had reason to hope Jackson would help. In different ways, the Indian Removal Act of 1830 (which authorized the forced dislocation of American Indian tribes from their homelands in the southeast) and the Force Bill of 1833 (which empowered the president to ensure compliance with federal tariffs in South Carolina) had demonstrated Jackson’s willingness to use federal power, including military might, to enforce federal legislation. But that overreach had been the result of political calculations and had come at a high political cost; although other Southern states condemned South Carolina’s confrontation with the federal government, many slaveholders began to view all federal interventions as a threat to slavery. In this context, lending national aid to a marginalized people in the slave state of Missouri promised little and risked much.

T. B. Welch engraving from drawing by J. B. Longacre, 1833 portrait of Lewis Cass, the secretary of war who responded to the members’ petition on behalf of President Andrew Jackson. Library of Congress.

T. B. Welch engraving from drawing by J. B. Longacre, 1833 portrait of Lewis Cass, the secretary of war who responded to the members’ petition on behalf of President Andrew Jackson. Library of Congress.

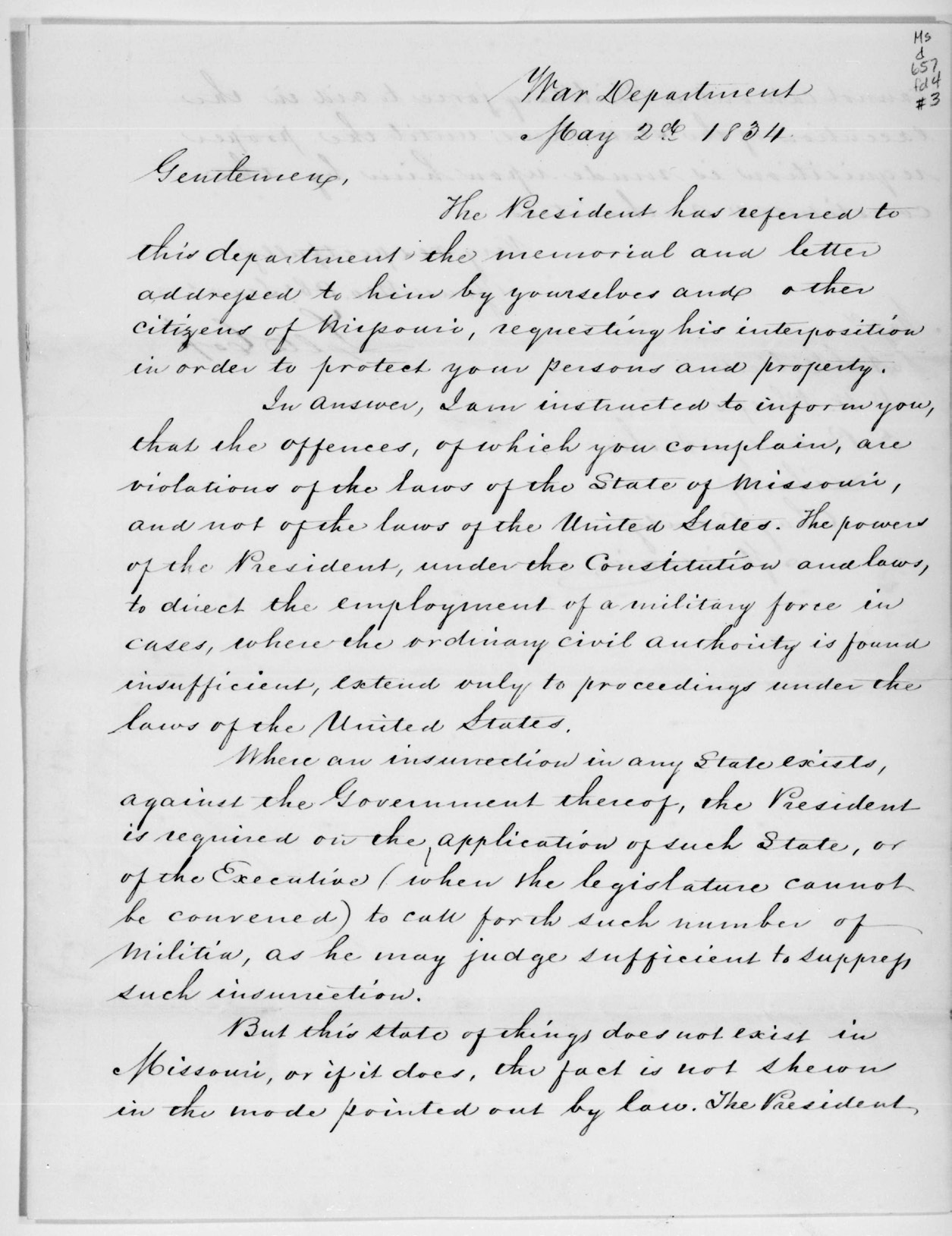

Church members could not have known the full scope of this background when Lewis Cass, Jackson’s secretary of war, responded to their petition in May 1834.[20] Cass informed the members that “the offences . . . are violations of the laws of the State of Missouri” and that “the powers of the President . . . to direct the employment of a military force . . . extend only to proceedings under the laws of the United States.” Cass noted that when a governor requests support to suppress an insurrection or execute state laws, the president can call forth a militia, but Cass did not believe these allowances applied to the petitioners’ case. Dunklin had referred them to the president, and now Cass directed them back to the governor. It appeared that neither office was willing to assist the “Latter Day Saints.”[21] The members continued to craft new petitions that aligned with their evolving grasp of the law, but political forces beyond their control undercut these efforts.

In particular, the anxious proslavery political response to the rise of radical abolitionism enervated the Saints’ calls for redress. In the mid-1830s, abolitionists directed a mail campaign meant to flood the nation with antislavery literature and inundated Congress with petitions to abolish slavery in DC, suppress the domestic slave trade, and refuse to admit new slave states.[22] Southerners united in their condemnation of these efforts and, during the same period, anti-abolitionist violence spread in the North.[23] In light of these developments and their own experiences, Church leaders in both Missouri and Ohio tried to distance themselves from abolitionists.[24] And yet, their petition efforts were inextricable from the debate over slavery. In 1836 the Senate informally tabled all antislavery petitions and the House adopted a formal gag rule on the same, actions that threatened other petitions—including those submitted by the Saints.[25]

Letter from secretary of war Lewis Cass, 2 May 1834. W. W. Phelps Collection of Missouri Documents, 1833–1837, Church History Library.

Letter from secretary of war Lewis Cass, 2 May 1834. W. W. Phelps Collection of Missouri Documents, 1833–1837, Church History Library.

During the late 1830s, unwitting Church members broadened their petition efforts. In 1838, months after Smith had arrived in Missouri, new hostilities broke out, culminating in the Saints’ removal from the state and Smith’s own imprisonment. While languishing in jail in March 1839, he instructed members to document their “suffering and abuses.”[26] He intended to present the resulting record “to the heads of the government in all there dark and hellish” hue in order to “claim that promise which shall call [God] forth from his hiding place and . . . the whole nation may be left without excuse.”[27] In the revealed framework of petitioning, the Saints’ continued efforts to obtain governmental remuneration further justified the nation’s destruction.[28]

After Smith and his fellow prisoners were allowed to escape in April, he prepared to petition President Martin Van Buren.[29] During the next few months, members gathered affidavits and approved a delegation to travel to DC.[30] In October the delegation—comprised of Smith, Sidney Rigdon, and Elias Higbee—set off for the nation’s capital. Along the way, Rigdon fell ill and rested while Smith and Higbee pushed on to DC, where they arrived on 28 November. The next day, they petitioned at “the feet of the President.”[31] Records do not indicate what, exactly, they wanted the president to do, but whatever their request, he responded: “I can do nothing for you,— if I do any thing, I shall come in contact with the whole State of Missouri.” As a renowned defender of states’ rights, Van Buren needed no time to weigh the political costs of assisting the marginalized Saints for wrongs suffered in a slave state.

This meeting fulfilled a major requirement of the 1833 revelation, but the central purpose of the trip was to present the Saints’ memorial to Congress. This, too, was part of the logic of divine retribution. Writing from DC to Church leaders in Commerce, IL, Smith noted, “we believe our case will be brought before the house, and we will leave the event with God— he is our Judge and the avenger of our wrongs.”[32] Each petition was part of an apocalyptic equation that hastened God’s calculated justice. With that understanding in mind, the delegates met with Illinois congressmen to finalize the memorial.

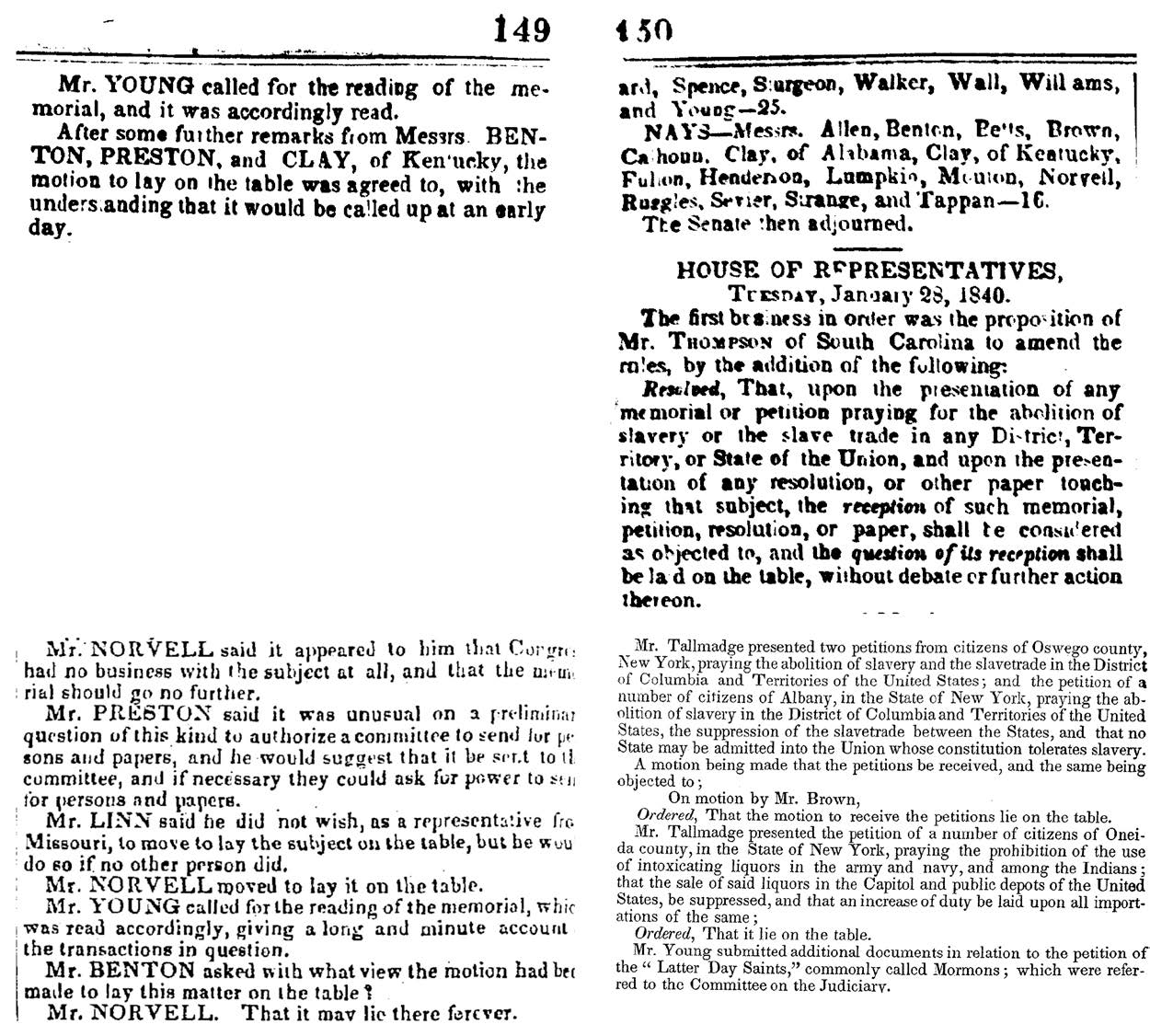

Senator Richard M. Young.

Senator Richard M. Young.

The memorial outlined the Saints’ losses in Missouri and laid claim to their constitutional “rights and immunities,” including “religious freedom.” The petitioners noted that if this “last appeal” failed, they would wait “until the Great Disposer of all human events shall in his own good time remove us from these persecutions to that promised land” of rest.[33]

While the Saints fulfilled their role in the divine drama, earthly factors shaped the more immediate outcome of their efforts. On 28 January 1840, the very day that Senator Richard M. Young presented the Saints’ memorial, the House passed a rule prescribing that each abolition petition “shall be considered as objected to, and the question of its reception shall be laid on the table.”[34] This created an extra barrier to the House’s consideration of abolition petitions.

As recorded in the Congressional Globe, Senator Richard Young introduced the Latter-day Saints’ memorial. That same day, the House of Representatives made it even more difficult to consider abolition petitions. Congressional Globe, 28 January 1840, 149, 150. Library of Congress.

As recorded in the Congressional Globe, Senator Richard Young introduced the Latter-day Saints’ memorial. That same day, the House of Representatives made it even more difficult to consider abolition petitions. Congressional Globe, 28 January 1840, 149, 150. Library of Congress.

Meanwhile, Senator Young presented the Saints’ memorial on the Senate floor and moved that it be referred to the Committee on the Judiciary. Missouri’s Lewis F. Linn protested, “A sovereign State seemed about to be put on trial before the Senate . . . and he was entirely opposed to the jurisdiction.” John Norvell of Michigan agreed, saying, “It appeared to him that Congress had no business with the subject at all.” Proslavery politics had nurtured the federalism reflected in these statements. In other words, the forces supporting the right to slave property had developed the convincing constitutional argument that the status of slavery fell entirely outside federal jurisdiction—but completely inside state jurisdiction. Linn knew it would be awkward if he moved “to lay the subject on the table, but he would do so if no other person did.” Norvell obliged him. But before the vote, Young succeeded in having the memorial read. After the reading, Missouri’s Thomas Hart Benton asked about the intention to table the memorial, to which Norvell replied, “That it may lie there forever.”[35] Norvell’s proposal recalled the gag rule on antislavery petitions.

To be clear, those petitions and the Saints’ memorial were different. The former seemed to threaten direct federal involvement in the Southern states, while the latter requested federal support for a people living in the North. And yet, while the decision to table antislavery petitions did not dictate Congress’s determination regarding the Saints’ memorial, debates over slavery demanded that politicians give constant consideration to state sovereignty and federal power. This is evident in a concluding suggestion made by the prominent senator from Kentucky, Henry Clay. He proposed that “inquiry should be made by the committee whether” the Saints’ memorial “is a matter of grievance, and, if it is, whether Congress has any power of redress.”[36] After Clay’s proposal, the Senate agreed to lay the Saints’ petition “on the table . . . with the understanding that it would be called up at an early day.”[37]

A few weeks later, the Senate moved to refer the Saints’ memorial to the Judiciary Committee.[38] The next day, the senators engaged in a protracted debate over abolition petitions and the right to petition itself. While Clay and Daniel Webster championed “the right,” Calhoun demurred, insisting that “it was among the least important.” Calhoun asserted that “there could be no local grievance but what could be reached by” suffrage and the right of instruction, by which a state legislature could direct their senator to vote a certain way.[39] New Hampshire’s Henry Hubbard described the issue as one of jurisdiction, noting that “it seldom occurs (and perhaps has never occurred) that a petition is presented here which so mistakes its proper direction as to ask relief of this Government in matters respecting which the petitioner’s State Government alone possessed the power to grant relief.” Consequently, he explained, the “right of petition is the most limited of popular and political righ[t]s.”[40] This discussion bore the marks of proslavery politics, which had placed severe restraints on the right to petition.

On 17 February, the Saints’ petition again shared space with abolition petitions on the Senate floor. After the Senate tabled the latter, Young “submitted additional documents in relation” to the Saints’ petition.[41] A few days later, the Judiciary Committee heard testimony from Elias Higbee, Senator Linn, and others; a few weeks later, on 4 March, the members of the committee issued their opinion.[42] They determined “that the case presented . . . is not such a one as will justify or authorize any interposition by this Government.” They instructed the petitioners to “apply to the justice and magnanimity of . . . Missouri. . . . It can never be presumed,” the committee continued, “that a State either wants the power, or lacks the disposition, to redress the wrongs of its own citizens.”[43] These statements, which aligned perfectly with those made by Senator Hubbard, show that debates over slavery shaped the questions asked about the Saints’ petition and furnished politicians with the language to argue that the Saints’ case fell outside the realm of federal jurisdiction. Weeks later, the Senate approved the committee’s resolution.[44]

Reports printed in the Congressional Globe, the Daily Intelligencer, and the Journal of the Senate indicate that Senator Richard Young introduced the Latter-day Saints’ memorial in the midst of a congressional debate about abolition petitions.

Reports printed in the Congressional Globe, the Daily Intelligencer, and the Journal of the Senate indicate that Senator Richard Young introduced the Latter-day Saints’ memorial in the midst of a congressional debate about abolition petitions.

When Higbee learned of the decision, he passed it on to Smith, who had returned to Illinois. “We have made our last appeal to all earthly tribunals,” Higbee wrote, and we “have a right now which we could not heretofore so fully claim— That is of asking God for redress & redemption.”[45] Days before Higbee’s letter arrived, Smith publicly reported on his DC trip and warned of the justice that would befall the nation if it failed to offer redress.[46] News of the Senate’s decision fueled his contempt.[47] During an April conference, the Saints agreed that in “turning a deaf ear,” Congress called “down upon their heads, the righteous judgments of an offended God.”[48] In a discourse given a few months later, Smith presented an apocalyptic vision in which God would “cast a vot[e] against van buren” and the nation.[49] When forces beyond his control mitigated efforts to obtain redress, Smith added them to the revealed reckoning of God’s justice. The human effort to prepare the land for the Lord’s harvest had neared completion.

During the 1840s, the Saints continued to petition for redress.[50] In November 1843 (the same month another doomed memorial was written to Congress), Smith wrote to five prospective presidential candidates, including Calhoun, asking whether they would provide redress if they were elected.[51] In his response, Calhoun wrote that the question “does not come within the Jurisdiction of the Federal Government.”[52] A month later, Smith fired back. Mocking the champion of state sovereignty, he asked, “What think ye of imperium in imperio?” Showing little compunction at this stage, Smith warned that if the federal government lacked restorative power, “God will come out of his hiding place and vex this nation with a sore vexation.”[53]

Most immediately, the Saints’ failure to obtain redress generated Smith’s 1844 presidential campaign, but the failed petitioning also shaped the simultaneous move to form a new government and a new constitution.[54] On 11 March, Smith organized the Council of Fifty, understood to be the political kingdom of God, and the council began discussing the creation of “a constitution.”[55] Smith’s faith in government had long since expired and his belief in the sacralized right to petition had been all but extinguished. Now his faith in the Founders’ Constitution waned. The nature of the Saints’ constitutionalism allowed for this development. The fact that their constitutional reverence rested on a revelation implied that their ultimate faith in law and justice went beyond the document produced by inspiration to the source of the inspiration itself. The Saints had adopted and advanced a view of the Constitution as a sacred text, but their understanding of inspiration and revelation as continual freed them from seeing the Constitution as a final legal arbiter. This version of constitutional reverence allowed Smith to set the Constitution aside when it proved insufficient.

On 18 April, Willard Richards presented the draft of a new constitution. The first line echoed the United States Constitution before making a quick departure: “We, the people of the Kingdom of God, knowing that all power emanates from God.”[56] This reflected the council’s belief that the time had come when “the supreme law of the land shall be the word of Jehovah.”[57] The new constitution also described the prophet as the Lord’s mouthpiece. This emphasis anticipated Smith’s instruction, given just a week later, to “let the constitution alone.” In the voice of the Lord, Smith told the council, “yea are my constitution.”[58] The same source that had encouraged constitutional reverence now interrupted the council’s efforts to create a new constitution; all of these events indicated the Saints’ ultimate allegiance to God.

On the surface, the developments during the spring of 1844 seemed to be a clear departure from the earlier emphasis on constitutional appeals. But the move to petition God himself had been commanded in the very revelation that sacralized that right. Indeed, the turn to God as ultimate legislator had been anticipated even before 1833. In a January 1831 revelation, the Lord had stated, “In time ye shall have no King nor Ruler for I will be your King . . . & ye shall be a free People & ye shall have no laws but my laws for I am your Law giver.”[59] By March 1844, it seemed that the time had arrived for the Lord to fulfill this millennial promise.

Notes

[1] Revelation, 16–17 December 1833 [D&C 101], in Gerrit J. Dirkmaat, Brent M. Rogers, Grant Underwood, Robert J. Woodford, and William G. Hartley, eds., Documents, Volume 3: February 1833–March 1834, vol. 3 of the Documents series of The Joseph Smith Papers, ed. Ronald K. Esplin and Matthew J. Grow (Salt Lake City: Church Historian’s Press, 2014), 386–97.

[2] JSP, D3:396.

[3] Jonathan Gienapp, The Second Creation: Fixing the American Constitution in the Founding Era (Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2018).

[4] See, for example, Revelation, 20 July 1831 [D&C 57], in Matthew C. Godfrey, Mark Ashurst-McGee, Grant Underwood, Robert J. Woodford, and William G. Hartley, eds., Documents, Volume 2: July 1831–January 1833, vol. 2 of the Documents series of The Joseph Smith Papers, ed. Dean C. Jessee, Ronald K. Esplin, and Richard Lyman Bushman (Salt Lake City: Church Historian’s Press, 2013), 5–12.

[5] Revelation, 6 August 1833 [D&C 98:5], in JSP, D3:224.

[6] Joseph Smith to Church Leaders in Jackson County, Missouri, 18 August 1833, in JSP, D3:267.

[7] “To His Excellency, Daniel Dunklin,” Evening and Morning Star 2 (December 1833): 114–15.

[8] Daniel Dunklin, Jefferson City, MO, to W. W. Phelps et al., Independence, MO, 19 October 1833, William W. Phelps, Collection of Missouri Documents, CHL.

[9] See W. T. Wood et al., Independence, MO, to W. W. Phelps, et al., 28 October 1833, William W. Phelps, Collection of Missouri Documents, CHL; and W. W. Phelps, to Mssrs. Wood, Rees, Doniphan, and Atchison, 30 October 1833, William W. Phelps, Collection of Missouri Documents, CHL.

[10] William W. Phelps et al., Clay Co., MO, to Daniel Dunklin, 6 December 1833, copy, William W. Phelps, Collection of Missouri Documents, CHL.

[11] Joseph Smith to Edward Partridge, 10 December 1833, in JSP, D3:372.

[12] Joseph Smith to Edward Partridge, 10 December 1833, in JSP, D3:379.

[13] Revelation, 16–17 December 1833, in JSP, D3:389 [D&C 101:1–6].

[14] Revelation, 16–17 December 1833, in JSP, D3:390 [D&C 101:1–6].

[15] Revelation, 16–17 December 1833, in JSP, D3:395 [D&C 101:76–80].

[16] See Luke 18:1–8.

[17] Revelation, 16–17 December 1833, in JSP, D3:395–96, [D&C 101:81–89].

[18] Daniel Dunklin, Jefferson City, MO, to W. W. Phelps et al., 4 February 1834, William W. Phelps, Collection of Missouri Documents, CHL.

[19] Edward Partridge et al., Petition to Andrew Jackson, 10 April 1834, William W. Phelps, Collection of Missouri Documents, CHL. Phelps sent the same petition to Missouri Senator Thomas Hart Benton. W. W. Phelps to Thomas H. Benton, 10 April 1834, William W. Phelps, Collection of Missouri Documents, CHL.

[20] Lewis Cass to A. S. Gilbert et al., 2 May 1834, William W. Phelps, Collection of Missouri Documents, CHL.

[21] “Communicated,” The Evening and the Morning Star 2 (May 1834), 160.

[22] Bertram Wyatt-Brown, “The Abolitionists’ Postal Campaign of 1835,” Journal of Negro History 50 (October 1965): 227–38.

[23] Susan Wyly-Jones, “The 1835 Anti-Abolition Meetings in the South: A New Look at the Controversy over the Abolition Postal Campaign,” Civil War History 47, no. 4 (2001): 289–309. On the Southern response, see Stephen M. Feldman, Free Expression and Democracy in America: A History (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008), 129–32.

[24] See, for example, “The Outrage in Jackson County, Missouri,” Evening and Morning Star 2 (January 1834), 241–44; Declaration on Government and Law, circa August 1835 [D&C 134:12], in Matthew C. Godfrey, Brenden W. Rensink, Alex D. Smith, Max H Parkin, and Alexander L. Baugh, eds., Documents, Volume 4: April 1834–September 1835, vol. 4 of the Documents series of The Joseph Smith Papers, ed. Ronald K. Esplin and Matthew J. Grow (Salt Lake City: Church Historian’s Press, 2016), 484 [D&C 134:12]; [Oliver Cowdery,] “Abolition,” Northern Times, 9 October 1835, 2; Joseph Smith to Oliver Cowdery, circa 9 April 1836, in Brent M. Rogers, Elizabeth A. Kuehn, Christian K. Heimburger, Max H Parkin, Alexander L. Baugh, and Steven C. Harper, eds., Documents, Volume 5: October 1835–January 1838, vol. 5 of the Documents series of The Joseph Smith Papers, ed. Ronald K. Esplin, Matthew J. Grow, and Matthew C. Godfrey (Salt Lake City: Church Historian’s Press, 2017), 231–43; Warren Parrish, “For the Messenger and Advocate,” LDS Messenger and Advocate, April 1836, 2:295–96; and “The Abolitionists,” Messenger and Advocate, April 1836, 2:299–301. On the broader context and racial implications of these publications, see W. Paul Reeve, Religion of a Different Color: Race and the Mormon Struggle for Whiteness (New York: Oxford University Press, 2015), 122–26. On Latter-day Saint antislavery and anti-abolitionism, see Newell G. Bringhurst, Saints, Slaves, and Blacks: The Changing Place of Black People Within Mormonism (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1981), 15–22.

[25] See William Lee Miller, Arguing about Slavery: The Great Battle in the United States Congress (New York: Knopf, 1995); and Stephen M. Feldman, Free Expression and Democracy, 133–39.

[26] Joseph Smith to Edward Partridge and the Church, circa 22 March 1839, in Mark Ashurst-McGee, David W. Grua, Elizabeth Kuehn, Alexander L. Baugh, and Brenden W. Rensink, eds., Documents, Volume 6: February 1838–August 1839, vol. 6 of the Documents series of The Joseph Smith Papers, ed. Ronald K. Esplin, Matthew J. Grow, and Matthew C. Godfrey (Salt Lake City: Church Historian’s Press, 2017), 343. See also Joseph Smith to Emma Smith, 21 March 1839, in JSP, D6:323.

[27] Smith to Partridge and the Church, in JSP, D6:343.

[28] Smith to Partridge and the Church, in JSP, D6:345.

[29] See Historical Introduction to Promissory Note to John Brassfield, 16 April 1839, in JSP, D6:366–67.

[30] See Minutes, 4–5 May 1839, in JSP, D6:383–88; and Joseph Smith, Bill of Damages, 4 June 1839, in JSP, D6:436.

[31] For an overview of the trip, see Volume Introduction, in Matthew C. Godfrey, Spencer W. McBride, Alex D. Smith, and Christopher James Blythe, eds., Documents, Volume 7: September 1839–January 1841, vol. 7 of the Documents series of The Joseph Smith Papers, ed. Ronald K. Esplin, Matthew J. Grow, and Matthew C. Godfrey (Salt Lake City: Church Historian’s Press, 2018), xxiv–xxviii.

[32] Letter to Hyrum Smith and Nauvoo High Council, 5 December 1839, in JSP, D7:70.

[33] Memorial to the United States Senate and House of Representatives, circa 30 October 1839–27 January 1840, in JSP, D7:138–74.

[34] Cong. Globe, 26th Cong., 1st Sess. 150–51 (1840).

[35] “Twenty-Sixth Congress,” Daily National Intelligencer, 29 January 1840, 2.

[36] “Twenty-Sixth Congress,” 2.

[37] Cong. Globe, 26th Cong., 1st Sess., 149.

[38] Cong. Globe, 26th Cong., 1st Sess., 149, 185.

[39] Cong. Globe, 26th Cong., 1st Sess., 149, 186–87.

[40] Cong. Globe, 26th Cong., 1st Sess., 149, 195–96; emphasis in original.

[41] Senate Journal, 26th Cong., 1st Sess., 179 (17 February 1840).

[42] Cong. Globe, 26th Cong., 1st Sess., 232.

[43] Appendix: Report of the United States Senate Committee on the Judiciary, 4 March 1840, in JSP, D7:543.

[44] Senate Journal, 26th Cong., 1st Sess., 23 March 1840, 259–60.

[45] Letter from Elias Higbee, 26 February 1840, in JSP, D7:199–200.

[46] See Historical Introduction to Discourse, 1 March 1840, in JSP, D7:201.

[47] Letter from Elias Higbee, 24 March 1840, in JSP, D7:232–34.

[48] Minutes and Discourse, 6–8 April 1840, in JSP, D7:246–50.

[49] Discourse, circa 19 July 1840, in JSP, D7:337.

[50] The Saints sent three more redress petitions to Congress, one in 1840, another in 1842, and one more in 1844. All of these petitions failed. See Clark V. Johnson, ed., Mormon Redress Petitions: Documents of the 1833–1838 Missouri Conflict (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1992), 393–614.

[51] Letter to Martin Van Buren, Henry Clay et al., 4 November 1843, Joseph Smith Collection, CHL. Smith also wrote Richard M. Johnson, who had served as Van Buren’s vice president.

[52] John C. Calhoun to Joseph Smith, 2 December 1843, Joseph Smith Collection, CHL. See also Lewis Cass to Joseph Smith, 9 December 1843, Joseph Smith Collection, CHL; and Henry Clay to Joseph Smith, 15 November 1843, Joseph Smith Collection, CHL.

[53] Joseph Smith to John C. Calhoun, 2 January 1844, Joseph Smith Collection, CHL. On this interaction, see James B. Allen, “Joseph Smith vs. John C. Calhoun: The States’ Right Dilemma and Early Mormon History,” in Joseph Smith Jr.: Reappraisals after Two Centuries, ed. Reid L. Neilson and Terryl L. Givens (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009), 73–90. See also Brent M. Rogers, Unpopular Sovereignty: Mormons and the Federal Management of Early Utah Territory (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2017), 25–28.

[54] General Smith’s Views of the Powers and Policy of the Government of the United States (Nauvoo, IL: John Taylor, printer, 1844).

[55] Council of Fifty, “Record,” 11 March 1844, in Matthew J. Grow, Ronald K. Esplin, Mark Ashurst-McGee, Gerrit J. Dirkmaat, and Jeffrey D. Mahas, eds., Administrative Records, Volume 1: Council of Fifty Minutes, March 1844–January 1846, vol. 1 of the Administrative Record series of The Joseph Smith Papers, ed. Roland K. Esplin, Matthew J. Grow, and Matthew C. Godfrey (Salt Lake City: Church Historian’s Press, 2016), 40, 42.

[56] Council of Fifty, “Record,” 18 April 1844, in JSP, CFM:110.

[57] Council of Fifty, “Record,” 18 April 1844, in JSP, CFM:112.

[58] Council of Fifty, “Record,” 25 April 1844, in JSP, CFM:136, 137.

[59] Revelation, 2 January 1831 [D&C 38], in Michael Hubbard MacKay, Gerrit J. Dirkmaat, Grant Underwood, Robert J. Woodford, and William G. Hartley, eds., Documents, Volume 1: July 1828–June 1831, vol. 1 of the Documents series of The Joseph Smith Papers, ed. Dean C. Jessee, Ronald K. Esplin, Richard Lyman Bushman, and Matthew J. Grow (Salt Lake City: Church Historian’s Press, 2013), 231–32.