The Prophetic Nature of the Family Proclamation

W. Justin Dyer and Michael A. Goodman

W. Justin Dyer and Michael A. Goodman, “The Prophetic Nature of the Family Proclamation,” in Latter-day Saints in Washington, DC: History, People, and Places, ed. Kenneth L. Alford, Lloyd D. Newell, and Alexander L. Baugh (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book), 135‒54.

W. Justin Dyer and Michael A. Goodman were associate professors of Church history and doctrine at Brigham Young University when this was written.

The Family: A Proclamation to the World. © Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

The Family: A Proclamation to the World. © Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

Within the restored gospel of Jesus Christ, “The Family: A Proclamation to the World” is arguably one of the most influential documents produced in the past hundred years. Since its inception twenty-four years ago, it has been cited more than 230 times in general conference, hung on the walls of Latter-day Saint homes throughout the world, and presented to leaders around the globe. Indeed, in the first ever meeting between a pope and a prophet of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, President Russell M. Nelson presented the pope with two items—a Christus statue and a copy of the family proclamation. Despite its central location within the teachings of the restored gospel of Jesus Christ, the purpose and place of the proclamation has been debated in many circles. Our purpose here is to provide clarity on both the cultural and political context and the prophetic nature of the family proclamation of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

The debates regarding the proclamation are particularly pointed in regard to the proclamation’s political implications and uses. Indeed, although “The Family: A Proclamation to the World” was given to help individuals avoid “deception concerning standards and values,” it was also explicitly designed to encourage “officers of government” to promote “measures designed to maintain and strengthen family as the fundamental unit of society.”[1] And while the personal application of the proclamation by individuals may be its most prominent feature, its public policy applications were immediate and are continuing. Indeed, Washington, DC, became a location central in efforts to promote the proclamation’s principles.

President Russell M. Nelson and Elder M. Russell Ballard visit with Pope Francis at the Vatican in Rome, Italy, 2019. Deseret News.

President Russell M. Nelson and Elder M. Russell Ballard visit with Pope Francis at the Vatican in Rome, Italy, 2019. Deseret News.

On 13 November 1995, less than two months after presenting “The Family: A Proclamation to the World” in the general Relief Society meeting, President Gordon B. Hinckley traveled to Washington, DC, where the proclamation would be central in his visits with leaders in the nation’s capital. President Hinckley gave a copy of the proclamation to U.S. president Bill Clinton in a meeting at the White House.[2] A prominent theme of the meeting was the “importance of promoting measures that maintain and strengthen the family as the fundamental unit of society.”[3] The night before this White House meeting, President Hinckley hosted an informal reception with several Latter-day Saint members of Congress, providing each with a copy of the proclamation.[4]

President Gordon B. Hinckley and Sister Marjorie Hinckley. Photo by Jeffrey D. Allred, Deseret News.

President Gordon B. Hinckley and Sister Marjorie Hinckley. Photo by Jeffrey D. Allred, Deseret News.

Four days after this meeting, Utah Congressman James Hansen read the proclamation into the congressional record of the House of Representatives. On December 15 of that same year, Utah senator Orrin Hatch read the proclamation on the floor of the Senate, stating, “I believe President Hinckley’s words have relevance for all Americans and will help each of us reaffirm our commitment to the primacy of the family as the basis for strong communities and to the sanctity of marriage as the foundation for healthy families.”[5] Before the year was out, the proclamation had gone from members of the Church to both houses of Congress and to the president of the United States. Later it would be included in an amicus brief to the U.S. Supreme Court, completing the proclamation’s formal presentation to all three branches of the U.S. federal government.

As these events unfolded and as the proclamation became a prominent feature of Church teachings and its public activism, individuals became divided on several of the proclamation’s statements. This generated some division on how the proclamation should be categorized within the theology of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints: Is it mainly political or religious in nature? Is the proclamation scripture? And does the proclamation declare changeable policies or immutable principles? This chapter will seek to bring greater clarity to these important questions.

The Context of the Family Proclamation’s Origins

Although family norms have shifted considerably over time, the past half century has seen the most rapid and fundamental changes to marriage law in U.S. history. During the 1960s and 1970s, an emphasis on the individual grew into “expressive individualism,”[6] which asserts that an individual’s desires are of primary moral concern. That is, within expressive individualism the highest “good” is the expression of oneself, however one chooses to define that self. Marriage laws and norms began to reflect these morals, and “individualistic marriages” began to rise in prominence in the 1960s, continuing to the present. Within an individualistic marriage, love is necessary to initiate the marriage, but the marriage was only seen as successful if it met “each partner’s innermost psychological needs.”[7] The rationale became “whatever an individual wants in a marriage is what they should be able to have, independent of any other considerations.” In other words, the most noble responsibility one had was to oneself.

President Gordon B. Hinckley. Photo by Chuck Wing, Deseret News.

President Gordon B. Hinckley. Photo by Chuck Wing, Deseret News.

These changes have been recognized as creating increased fragility in family relationships by both conservative and liberal scholars. Progressive scholar Stephanie Coontz concludes, “Everywhere marriage is becoming more optional and more fragile. Everywhere the once-predictable link between marriage and child rearing is fraying. And everywhere relations between men and women are undergoing rapid and at times traumatic transformation.”[8] Within this transformation the most fundamental shift of marriage law in U.S. history occurred: same-sex marriage. With individualistic marriage, societies began to view limits on the definition of marriage as nonsensical—despite the uniqueness of the male-female relationship that led virtually every society to define marriage as between a man and a woman. With the new moral groundwork of the individualistic marriage laid, in May 1970, the first same-sex couple in the U.S. applied for a marriage license.[9] The cultural tide that led to this attempt was not simply about same-sex marriage but a wholesale rethinking of family relationships. This tide coincided with other rapid changes including higher rates of divorce, cohabitation, and out-of-wedlock childbearing. These and other family-related issues were not simply cultural phenomena. Several of these family issues were featured in important Supreme Court rulings. [10] Within this background, we study the key cultural events, social trends, and Church responses in the two decades preceding the proclamation.

The Stonewall riots of 1969 led to national attention of homosexuality, and calls for protections and rights for homosexuals emerged. For instance, in the 1970s, three same-sex couples applied for, but were denied, marriage licenses.[11] Man-woman family arrangements were also undergoing substantial change. Compared to the 1960s, the 1970s showed a 50 percent increase in the divorce rate and a doubling of the rate of out-of-wedlock childbirths. From 1970 to 1980, the number of cohabitating couples more than tripled, the percentage of children born to unmarried women nearly doubled, the marriage rate dropped 15 percent, and the divorce rate increased by 52 percent.[12] Legislation and policies recognizing same-sex partnerships and marriages began to increase, and the Unitarian Universalist Association was the first major Protestant denomination to approve same-sex marriages.[13]

During this time of substantial family change, the Church’s emphasis on the family appeared to grow. According to the LDS General Conference Corpus,[14] the use of the word “family” in general conference doubled from the 1960s to the 1970s, with its usage increasing in nearly every decade since. The October 1970 general conference was the first time “family” was said to be under “attack.”[15] In 1970, the Church designated Monday nights as a night reserved for family home evening.[16] The Church began producing materials regarding homosexuality for ecclesiastical leaders and members alike. For example, in 1971 the Church produced a pamphlet authored by Spencer W. Kimball entitled New Horizons for Homosexuals.

While divorce rates tapered off from the 1980s to the 1990s (though still remaining high), the rate of out-of-wedlock births, cohabitation, and single-parent families continued to increase.[17] The 1990s were also a turning point in same-sex marriage. In December 1990, three same-sex couples applied for marriage licenses at the Hawaii Department of Health but were denied. A lawsuit ensued but was dismissed in October of 1991. The next month, the First Presidency issued a letter to all Church members that focused on standards of sexual purity, declaring—among other things—homosexual behavior as sinful and making a distinction between homosexual thoughts, feelings, and behaviors.[18]

The 1991 Hawaii lawsuit was appealed to the Hawaii Supreme Court, which ruled in 1993 that limiting marriage to the male-female couple was discrimination based on sex. The case went to lower courts, where the burden of proof was on the state to show a compelling interest for denying same-sex couples the right to marry. This was the first time in the U.S. that a court of last resort employed a constitutional principle as the basis for same-sex marriage.[19] Spurred by these and other events, lawmakers in Washington, DC were also active in the same-sex marriage debate, passing the Federal Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA) in 1996, an act that allowed states not to recognize same-sex marriages performed in other states. Even though Hawaii was one of the first states to seriously grapple with same-sex marriage legislation, the issue was spreading throughout the country. Eight of the first ten states or districts to legalize same sex marriage were on the east coast—Washington, DC, being one of them.[20]

During 1994, as the Hawaii case made its way through the courts, the Church was active on various fronts in supporting traditional marriage in Hawaii. This included a First Presidency letter sent to Church leaders throughout the world titled “Same Gender Marriages.” The letter stated that “the principles of the gospel and the sacred responsibilities given us request that The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints oppose any efforts to give legal authorization to marriages between persons of the same gender” and that “we encourage members to appeal to legislators, judges, and other government officials to preserve the purposes and sanctity of marriage between a man and a woman.”[21]

This same year was the UN’s International Year of the Family, which became pivotal in the creation of the proclamation. The Church sent representatives to a conference in Beijing, and Elder Boyd K. Packer asserted, “It was not pleasant what they [the representatives] heard.” Although not elaborating on this statement, Elder Packer noted that he read the proceedings of a subsequent UN family conference in Cairo (5–13 September 1994) in which “the word marriage was not mentioned. It was at a conference on the family, but marriage was not even mentioned.”[22] In New York, the UN Secretary General acknowledged initial conflict over even having a year of the family, stating, “At the time, there was no consensus. Some did not see the point of an International Year of the Family. . . . Some people argued that support for the family discriminates against those who prefer to live outside family units.”[23]

It was later announced that a conference on the family would occur in Salt Lake City. Referring to a recommendation by his fellow Apostles, Elder Packer said, “Some of us made the recommendation: ‘They are coming here. We had better proclaim our position.’” Elder Ballard similarly described the conference: “Various world conferences were held dealing either directly or indirectly with the family. In the midst of all that was stirring on this subject in the world, the First Presidency and the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles could see the importance of declaring to the world the revealed, true role of the family in the eternal plan of God.”[24]

The First Presidency: Thomas S. Monson, Henry B. Eyring, and Dieter F. Uchtdorf, 2008. © Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

The First Presidency: Thomas S. Monson, Henry B. Eyring, and Dieter F. Uchtdorf, 2008. © Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

The proclamation became the Church’s central document in defining its tenets on the family. Although primarily designed to aid individuals in their own family lives, it also called on government officials to “promote those measures designed to maintain and strengthen the family” and was given to government leaders in the U.S. and abroad. In June 2006, Elder Russell M. Nelson quoted from the proclamation at the U.S. Capitol Building in support of a constitutional amendment protecting marriage. As he later recounted, “Over the years, I’ve given copies of the proclamation to many governmental leaders not of our faith who’ve been grateful, telling them they were free to use it any way they might care to.”[25]

The Church again brought the proclamation to Washington, DC, with eighteen religious groups in an amicus brief to the U.S. Supreme Court regarding same-sex marriage. A portion of the brief reads, “Marriage is also fundamental to the doctrine of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. A formal doctrinal proclamation declares that ‘marriage between a man and a woman is ordained of God.’” Whether coincidental or not, several dissenting opinions about the brief reflect principles within the proclamation. For instance, Justice John Roberts notes that marriage is fundamentally about establishing a family pattern that involves (1) those who conceive children caring for them and (2) the promotion of a lifelong, sexually faithful union between a man and a woman.[26]

Three days after the Supreme Court’s decision legalizing same-sex marriage, the First Presidency (Thomas S. Monson, Henry B. Eyring, and Dieter F. Uchtdorf) referenced the proclamation and said, “Changes in the civil law do not, indeed cannot, change the moral law that God has established. . . . We invite all to review and understand the doctrine contained in ‘The Family: A Proclamation to the World.’”[27] The First Presidency directed local leaders to “meet with all adults, young men, and young women on either July 5 or July 12 in a setting other than sacrament meeting and read to them the entire statement.”[28] The Church continued using the proclamation in court cases around the world. For example, in 2016 a letter from the Church was read in all congregations in Mexico, citing the proclamation as reasoning for members to oppose same-sex marriage.

The Prophetic Nature of the Family Proclamation

On learning of the political and public context behind the family proclamation, some have questioned what role God and revelation played in its inception. How members view the family proclamation can have profound consequences on their testimony of the restored gospel, the role of prophets and apostles, and doctrines related to gender, sexuality, and the family. Though a clear majority of members express confidence in Church teachings overall,[29] on issues regarding gender, sexuality and the family, that confidence appears to be lessoning for a minority of members. Questions related to many of the teachings in the proclamation appear to be strongest among the younger generations.[30]

Current Member Understanding Regarding Gender, Sexuality, and the Family

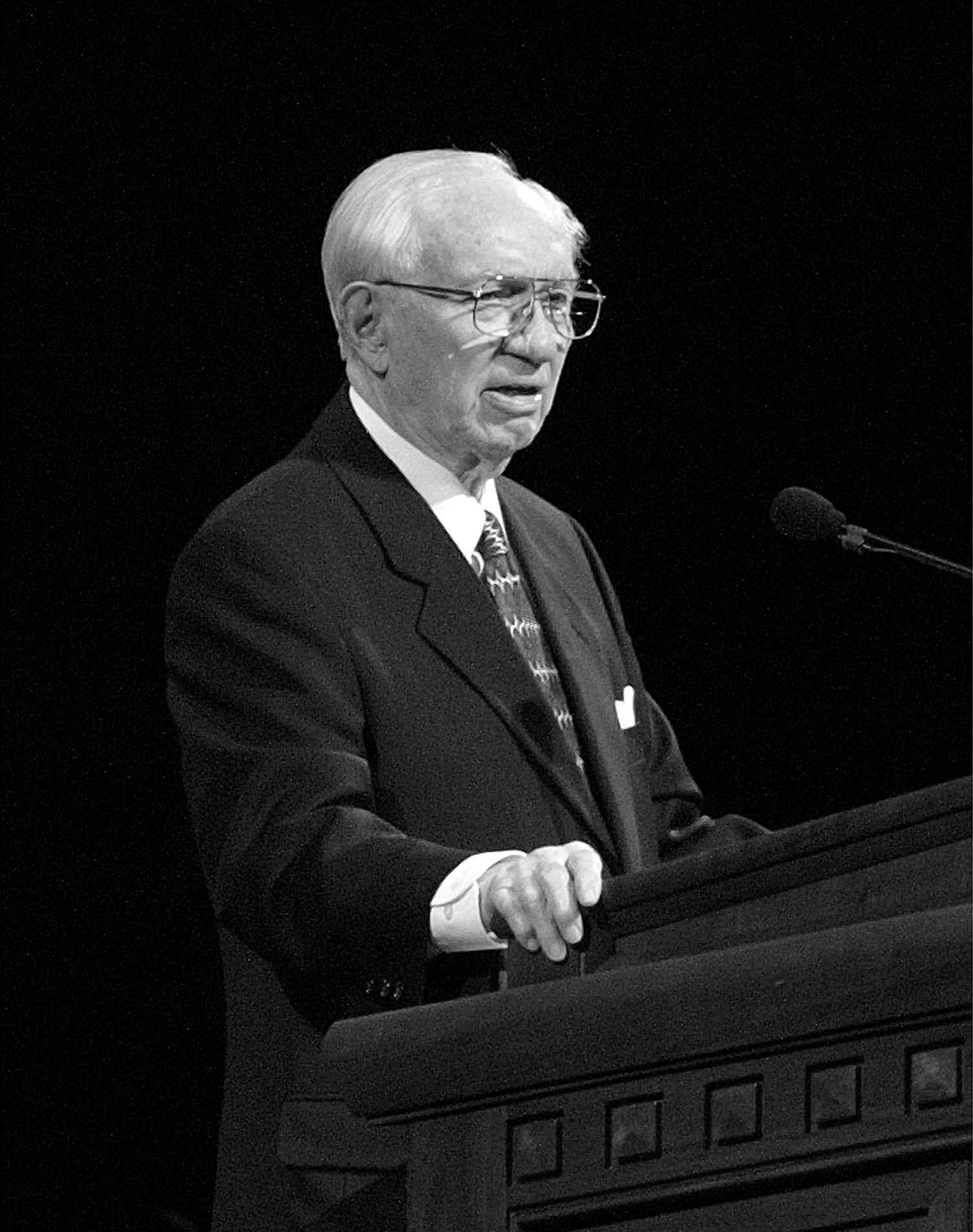

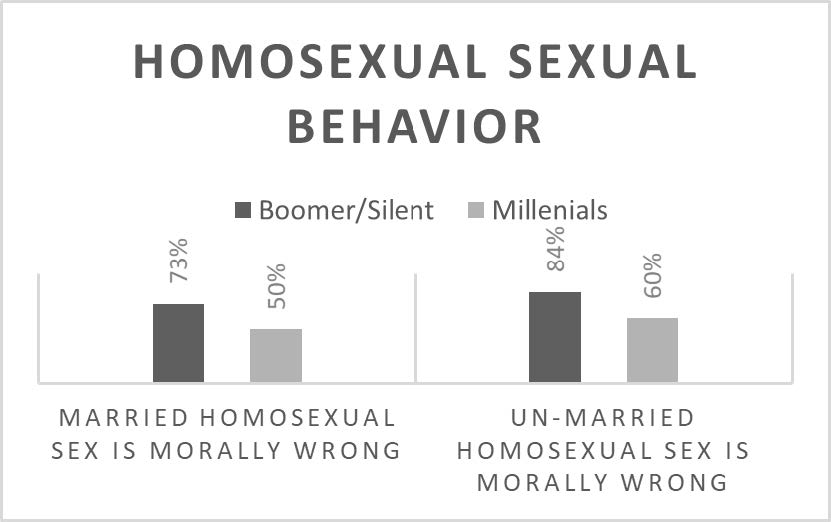

In her 2016 Next Mormons Survey (NMS), Jana Reiss asked a representative panel of Latter-day Saints about their views on issues related to gender, sexuality, and the family. The results indicate a moderate generational divide. Younger members appear to be less confident in Church teachings in general, especially teachings contained in the family proclamation. Figure 1 illustrates some of the NMS findings. The bars represent the percentage of members who consider each action to be morally wrong.

Similarly, when a PEW Research Center study asked whether homosexuality should be accepted by society, the number of Church members who agreed has risen from 24 percent in 2007 to 36 percent in 2014.[31] In the NMS study, that number was 48 percent in 2016. Between 50 and 60 percent of Latter-day Saint millennials agreed with the statement. When asked whether married or unmarried homosexual sex was morally wrong, 60 percent of millennials agreed that unmarried homosexual sex was immoral, while 50 percent agreed that married homosexual sex was immoral.

For some millennials, there appears to be a cultural disconnect from the teachings of the family proclamation, which state that the “powers of procreation are to be employed only between man and woman, lawfully wedded as husband and wife.” Such a disconnect fits with a popular narrative that the family proclamation is largely a statement of policy rather than a prophetic doctrinal pronouncement. However, that narrative is contrary to how the First Presidency and Quorum of Twelve have described and defined the document for over two decades.

Prophetic Definitions and Descriptions of the Family Proclamation

Figure 1. Reprinted from Jana Riess, The Next Mormons, 179.

Figure 1. Reprinted from Jana Riess, The Next Mormons, 179.

To get a more complete view of how the family proclamation has been defined and described by Church leaders, we studied every reference to the family proclamation in general conference since it was given on 23 September 1995. There have been more than 230 references to the family proclamation in general conference alone, with many more in the Church periodicals and curricular material. All members of the First Presidency and Quorum of Twelve who were coauthors of the document referred to it in general conference, most multiple times. This pattern continues today with almost all of the current First Presidency and Quorum of Twelve having referred to it numerous times in general conference.

Figure 2. Reprinted from Jana Riess, The Next Mormons, 182.

Figure 2. Reprinted from Jana Riess, The Next Mormons, 182.

An analysis of these statements reveals several repeated themes. When describing or defining the family proclamation, the most frequent themes were that the family proclamation was (1) inspired, (2) revealed, (3) eternal truth, (4) principles/

Inspired

Elder L. Tom Perry explained, “The inspired document ‘The Family: A Proclamation to the World’ states: ‘Husband and wife have a solemn responsibility to love and care for each other and for their children.”[32] Similarly, Elder Richard G. Scott taught, “Carefully study and use the proclamation of the First Presidency and the Twelve on the family. It was inspired of the Lord.”[33] Three years later Elder M. Russell Ballard warned that “to justify their rejection of God’s immutable laws that protect the family, . . . false prophets and false teachers even attack the inspired proclamation on the family.”[34]

Revealed/

Similarly, President Gordon B. Hinckley stressed that the teachings contained in the document come from prophets, seers, and revelators: “We of the First Presidency and the Council of the Twelve Apostles now issue a proclamation to the Church and to the world.”[35] Elder W. Eugene Hansen stated, “I leave you my witness that the proclamation on the family, which I referred to earlier, is modern-day revelation provided to us by the Lord through His latter-day prophets.”[36] Similarly, President Dallin H. Oaks bore his witness of the revelatory nature of the document when he proclaimed, “I testify of the truth and eternal importance of the family proclamation, revealed by the Lord Jesus Christ to His Apostles for the exaltation of the children of God.”[37]

Eternal Truth

Sister Bonnie Oscarson testified, “The proclamation on the family has become our benchmark for judging the philosophies of the world, and I testify that the principles set forth within this statement are as true today as they were when they were given to us by a prophet of God nearly 20 years ago.”[38] In a different conference, Elder Neil L. Anderson simply testified that “these are eternal truths.”[39] President Oaks also taught, “Modern revelation defines truth as a “knowledge of things as they are, and as they were, and as they are to come” (Doctrine and Covenants 93:24). That is a perfect definition for the plan of salvation and ‘The Family: A Proclamation to the World.’”[40]

Principles/

President Dieter F. Uchtdorf explained, “Procedures, programs, policies, and patterns of organization are helpful for our spiritual progress here on earth, but let’s not forget that they are subject to change. In contrast, the core of the gospel—the doctrine and the principles—will never change.”[41] When describing the teachings within the family proclamation, the general leadership of the Church almost always refers to those teachings as doctrines or principles. In 1996, Elder Robert D. Hales explained that [the family proclamation] “summarizes eternal gospel principles that have been taught since the beginning of recorded history and even before the earth was created.”[42] Elder L. Tom Perry exclaimed, “The doctrine of the family and the home was recently reiterated with great clarity and forcefulness in ‘The Family: A Proclamation to the World.”[43] Elder David B. Haight explained, “That marvelous document brings together the scriptural direction that we have received that has guided the lives of God’s children from the time of Adam and Eve and will continue to guide us until the final winding-up scene.”[44]

Prophets/

Since the proclamation was introduced, more than 30 of the 230 references in general conference have mentioned or emphasized the prophetic source and nature of the document, several of which have already been quoted. Elder Robert D. Hales explained that we should “watch, hear, read, study, and share the words of prophets to be forewarned and protected. For example, ‘The Family: A Proclamation to the World’ was given long before we experienced the challenges now facing the family.”[45] Elder M. Russell Ballard simply taught, “The proclamation is a prophetic document, not only because it was issued by prophets but because it was ahead of its time.”[46]

It is important to realize that even though the First Presidency and Quorum of Twelve have consistently spoken of the prophetic and revelatory basis of the family proclamation, it shouldn’t be thought that this means the doctrines contained therein are new. President Hinckley explicitly stated that the family proclamation is “a declaration and reaffirmation of standards, doctrines, and practices relative to the family which the prophets, seers, and revelators of this church have repeatedly stated throughout its history.”[47] This reality has been restated by several members of the First Presidency and Quorum of Twelve. Several sources have compiled lists that enumerate each doctrine contained in the family proclamation and when those doctrines were taught throughout the Church’s history.[48]

Prophetic Process

Until 2017 there were few statements from authoritative sources on the circumstances and processes which led to the family proclamation. That changed when President Dallin H. Oaks delivered his October 2017 general conference address, “The Plan and the Proclamation.” Another important source became available in 2019 when Sheri Dew published her memoir of President Russell M. Nelson: Insights from a Prophet’s Life: Russell M. Nelson. Combining both sources provides the best picture currently available of the circumstances and processes that led to the creation and publication of the family proclamation.

President Oaks explained that “the inspiration identifying the need for a proclamation on the family came to the leadership of the Church over 23 years ago.”[49] The decision was made to prepare a document, “perhaps even a proclamation,” and to present that document to the First Presidency for their consideration.[50] A committee consisting of Elders James E. Faust, Neal A. Maxwell, and Russell M. Nelson was appointed to create the first draft of the proposed document. The combined document was submitted to each member of the Quorum of the Twelve for reviewal and revision. [51] President Oaks explained, “Subjects were identified and discussed by members of the Quorum of the Twelve for nearly a year.”[52] Further, he explained that “language was proposed, reviewed, and revised. Prayerfully we continually pleaded with the Lord for His inspiration on what we should say and how we should say it. . . . During this revelatory process, a proposed text was presented to the First Presidency, who oversee and promulgate Church teachings and doctrine.”[53] The First Presidency made further changes before the united First Presidency and Quorum of Twelve formally ratified the final document under President Howard W. Hunter’s leadership just before he passed away in March 1995.[54]

Conclusion

The family proclamation was created in the context of secular and cultural realities that caused grave concerns among Church leaders regarding the family. These realities led the First Presidency and Quorum of Twelve to action. The overwhelming consensus of all statements by Church leaders since its inception is that the family proclamation is a prophetic document based on revealed eternal truth. Perhaps the most concise statement of this reality was given in the October 2017 general conference by President Oaks: “I testify that the proclamation on the family is a statement of eternal truth, the will of the Lord for His children who seek eternal life. It has been the basis of Church teaching and practice for the last 22 years and will continue so for the future. Consider it as such, teach it, live by it, and you will be blessed as you press forward toward eternal life. . . . I testify of the truth and eternal importance of the family proclamation, revealed by the Lord Jesus Christ to His Apostles for the exaltation of the children of God (see Doctrine and Covenants 131:1–4).”[55]

It is important to recognize that the Lord and his leaders love and care about all individuals, independent of how their lives may be progressing relative to the patterns within the family proclamation. As President Nelson recently stated, “Because we feel the depth of God’s love for His children, we care deeply about every child of God, regardless of age, personal circumstances, gender, sexual orientation, or other unique challenges.” [56]

A more accurate understanding of the cultural and political context that created the original need and the prophetic process by which the family proclamation was created can help members as they seek to gain their own testimony of this important proclamation to help us all understand the challenges inherent in our time and stand firm in that test.

Notes

[1] Gordon B Hinckley, “Stand Strong against the Wiles of the World,” Ensign, November 1995, 100.

[2] Jocelyn Mann Denyer and Michael R. Leonard, “President Hinckley Visits U.S. President, Others during Busy Period,” Ensign, February 1996.

[3] United States Congress, “Congressional Record—Extensions of Remarks,” 17 November 1995.

[4] Denyer and Leonard, “President Hinckley Visits U.S. President.”

[5] United States Congress, “Congressional Record—Senate,” 15 December 1995. S18674.

[6] Robert N. Bellah et al., Habits of the Heart: Individualism and Commitment in American Life (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1985).

[7] Paul R. Amato, “Institutional, Companionate, and Individualistic Marriages,” in Marriage at the Crossroads: Law, Policy, and the Brave New World of Twenty-First-Century Families, ed. Marsha Garrison and Elizabeth S. Scott (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2012), 110.

[8] Stephanie Coontz, Marriage, a History: How Love Conquered Marriage (New York: Penguin, 2006), 4.

[9] Daniel R. Pinello, America’s Struggle for Same-Sex Marriage (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2006).

[10] For example, Grisold v. Connecticut (1965) and Eisenstadt v. Baird (1972) legalizing contraceptives; Phillips v. Martin Marietta Corp (1971) on mothers’ employment; and, of course, Roe v. Wade (1973), legalizing abortion.

[11] Pinello, America’s Struggle, 22.

[12] The National Marriage Project, The State of Our Unions (Provo, UT: The Wheatley Institution and the School of Family Life, Brigham Young University, 2019) 15-30.

[13] Pew Research Center, “Religious Groups’ Official Positions on Same-Sex Marriage,” 7 December 2012.

[14] Mark Davies, LDS General Conference Corpus (website).

[15] Boyd K. Packer, in Conference Report, October 1970, 118.

[16] Michael A. Goodman, “Correlation: The Turning Point (1960s),” in Salt Lake City: The Place Which God Prepared, ed. Scott C. Esplin and Kenneth L. Alford (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Provo, UT: Deseret Book, 2011), 259–84.

[17] The National Marriage Project, The State of Our Unions, 15–30.

[18] See pertinent text in Dallin H. Oaks, “Same-Gender Attraction,” Ensign, October 1995, 8.

[19] Pinello, America’s Struggle, 25.

[20] See “A Timeline of the Legalization of Same-Sex Marriage in the U.S.,” A Brief History of Civil Rights in the United States, Georgetown Law Library (website).

[21] See Douglas Palmer, “3 LDS Officials Seek to Join Hawaii Suite,” Church News, 14 April 1995.

[22] Boyd K. Packer, “The Instrument of Your Mind and the Foundation of Your Character,” (Church Educational System Fireside for Young Adults, 2 February 2003).

[23] United Nations General Assembly Forty-ninth Session, 35th Meeting, 18 October 1994.

[24] M. Russell Ballard, “The Sacred Responsibilities of Parenthood” (address at Brigham Young University, 19 August 2003).

[25] Sheri L. Dew, Insights from a Prophet’s Life: Russell M. Nelson (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2019), 211–12.

[26] See also Justice Alito’s dissent in United States Supreme Court, Obergefell v. Hodges, No. 576 (United States Supreme Court October 2015).

[27] “Church Leaders Counsel Members after Supreme Court Same-Sex Marriage Decision,” 1 July 2015, Newsroom.org.

[28] “Church Leaders Counsel Members after Supreme Court Same-Sex Marriage Decision,” 1.

[29] Pew Research Center: Religion and Public Life. “Mormons in America—Certain in Their Beliefs, Uncertain of Their Place in Society,” 12 January 2012.

[30] Jana Riess, The Next Mormons: How Millennials Are Changing the LDS Church (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019), 15–18.

[31] Pew Research Center, “Most U.S. Christian Groups Grow More Accepting of Homosexuality,” 18 December 2015.

[32] L. Tom Perry, “Mothers Teaching Children in the Home,” Ensign, May 2010, 31.

[33] Richard G. Scott, “The Joy of Living the Great Plan of Happiness,” Ensign, November 1996, 75.

[34] M. Russell Ballard, “Beware of False Prophets and False Teachers,” Ensign, November 1999, 64.

[35] Hinckley, “Stand Strong,” 100.

[36] W. Eugene Hansen, “Children and the Family,” Ensign, May 1998, 63.

[37] Dallin H. Oaks, “The Plan and the Proclamation,” Ensign, November 2017, 31.

[38] Bonnie L. Oscarson, “Defenders of the Family Proclamation,” Ensign, November 2015, 14–15.

[39] Neil L. Andersen, “The Eye of Faith,” Ensign, May 2019, 34.

[40] Dallin H. Oaks, “Truth and the Plan,” Ensign, November 2018, 25.

[41] Dieter F. Uchtdorf, “Christlike Attributes—the Wind beneath Our Wings,” Ensign November 2005, 100.

[42] Robert D. Hales, “The Eternal Family,” Ensign, November 1996, 64.

[43] L. Tom Perry, “Obedience to Law Is Liberty,” Ensign, May 2013,88.

[44] David B. Haight, “Be a Strong Link,” Ensign, November 2000, 20.

[45] Robert D. Hales, “General Conference: Strengthening Faith and Testimony,” Ensign, November 2013, 7.

[46] M. Russell Ballard, “What Matters Most Is What Lasts Longest,” Ensign, November 2005, 41.

[47] Hinckley, “Stand Strong," 100.

[48] For example, see “Question: Have the Doctrines in the Mormon Document ‘The Family: A Proclamation to the World’ Long Been Taught in the Church?,” FairMormon (website).

[49] Oaks, “The Plan and the Proclamation,” 30.

[50] Dew, Insights from a Prophet’s Life, 208.

[51] Dew, Insights from a Prophet’s Life, 209.

[52] Oaks, “The Plan and the Proclamation,” 30.

[53] Oaks, “The Plan and the Proclamation,” 30.

[54] Dew, Insights from a Prophet’s Life, 209.

[55] Oaks, “The Plan and the Proclamation,” 30–31.

[56] Russell M. Nelson, “The Love and Laws of God” (address at Brigham Young University, 17 September 2019).