“Obliterated from the Face of the Earth”: Latter‐day Saint Flight and Expulsion

Gerrit J. Dirkmaat

Gerrit Dirkmaat, “'Obliterated from the Face of the Earth': Latter-day Saint Flight and Expulsion,” in Latter-day Saints in Washington, DC: History, People, and Places, ed. Kenneth L. Alford, Lloyd D. Newell, and Alexander L. Baugh (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book), 51‒66.

Gerrit Dirkmaat was an associate professor of Church history and doctrine at Brigham Young University when this was published.

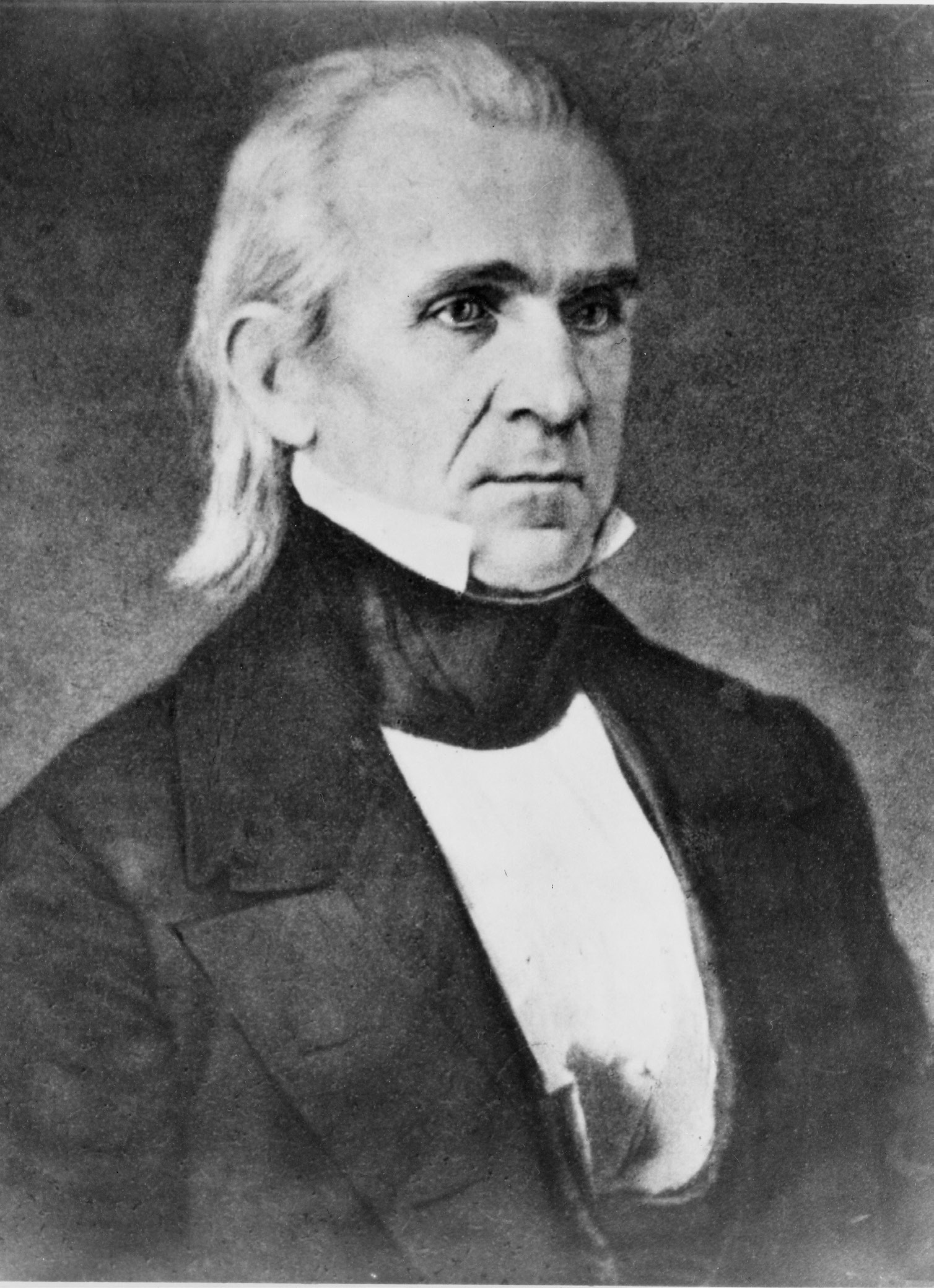

President James K. Polk (1795–1849). Library of Congress.

President James K. Polk (1795–1849). Library of Congress.

As President James Polk waited for his next visitor on 3 June 1846, the White House was abuzz with activity. Only three weeks earlier, the United States had declared war on the vast, sprawling nation of Mexico, and Polk had held nearly constant meetings with his cabinet, generals, politicians, and office seekers. While many expansionists hailed the outbreak of the war, critics of the jingoistic decisions that led to the outbreak abounded. Nevertheless, a week earlier Polk had made the decision to make Northern Mexico the primary objective for the first stages of the war and was deep into planning the expedition that would invade the enormous territory. It was an audacious gamble, fraught with logistical and political difficulties. Thus President Polk had determined to meet with his next visitor, although their obscure meeting has generally been lost to history.[1]

Polk was meeting with Jesse Little, an elder from The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints who presided over the missionary work for the Church in the eastern United States. Stationed as he was in Washington, DC, Little was also the de facto liaison for the Church with the U.S. government. Brigham Young sent Little instructions to meet with federal officials over various matters and to secure some kind of aid for the suffering Saints, if possible. For his part, Little—like his predecessor Samuel Brannan—not only kept Young apprised of missionary and public sentiment efforts in the nation’s capital and the East Coast generally, but also provided a watchful eye on the actions of the federal government and its officials in relation to the Latter-day Saints.

The actions of federal officials in Washington, including senators, cabinet members, members of the House of Representatives, and President James Polk himself, played a central role in the Latter-day Saint expulsion from the United States and in the creation of Latter-day Saint feelings of animosity toward the federal government for decades afterward. The federal government was often regarded as being apathetic and uninterested in the Latter-day Saint plight since mobs continued to commit acts of violence and local Illinois residents and newspapers demanded the “extermination” of the Saints from the state, even after the murders of Joseph and Hyrum Smith. Thus the federal story in the expulsion of the Saints—one of assumed inaction—is rarely considered, much less examined and told. It is often believed that the Saints were fleeing localized, though indefatigable and cruel, persecution. In reality, American foreign policy emanating from the nation’s capital looms large over the actions of both the Latter-day Saints and the United States government.

Jesse Little’s meeting with President Polk just after the outbreak of war could not have been more impactful on the relationship between the nation and the Saints. After assuring Little that he believed the Latter-day Saints now fleeing the United States were “true American citizens,” President Polk asked if “500 or more of the Mormons now on their way to [Mexican] California would be willing” to volunteer to fight for the United States.[2]

President James K. Polk in 1844. Library of Congress.

President James K. Polk in 1844. Library of Congress.

For Little, the presidential request was a sweet vindication long in coming. After years of ignoring Latter-day Saint persecution and dismissing the Saints’ petitions for redress for the personal and property crimes perpetrated against them in Missouri, after the lack of federal intervention in the decision to drive the Saints from Illinois, and after reports that the U.S. Army would in fact attempt to prevent them from leaving the nation to Mexico, Little thought the president was now expressing regret for the wrongs committed against the Saints.

In actuality, President Polk’s request for the Mormon Battalion was not an admission of past wrongdoing on the part of the nation but a culmination of the national political machinations that had driven the Saints from the country in the first place. While Little wrote an elated letter to Brigham Young explaining that the Latter-day Saints had finally received federal protection and acceptance, James Polk wrote his true feelings in his diary. He did not trust the Latter-day Saints at all. He had only met with Little and proposed the battalion to “prevent them from assuming a hostile attitude toward the U.S. after their arrival in [Mexican] California.” Making the point more clear, Polk wrote, “It was with the view to prevent this singular sect from becoming hostile to the U.S. that I held the conference with Mr. Little, and with the same view I am to see him again tomorrow.”[3]

Polk’s duplicity, misrepresenting his purposes for calling hundreds of men into the war wholly apart from military necessity, did not occur in a vacuum. For the Latter-day Saints, years of persecution and political ineptitude culminated in their decision to abandon the United States.

For a few years after the establishment of Nauvoo, Joseph Smith continued to hope that Americans would come to at least tolerate the Latter-day Saints. The Nauvoo Charter granted liberal municipal powers, including a city militia, that helped the Saints to feel safer from the type of lawless abuses of power that had led to so much blood and terror in Missouri. Yet by late 1843, darkening clouds of antagonism in the press and the public portended a trajectory that could only end negatively. While political considerations fueled conflict from the external community, Joseph’s revelations and teachings in Nauvoo also drove internal conflict that led some members to leave the faith. Foremost among those controversial doctrines was the secret practice of plural marriage by Joseph and many of his closest associates. Anathema as polygamy was to American Christianity and social tradition, even some previously devoted believers could not accept the radical new teaching and apostatized from the faith.

Before these controversies, however—even as early as 1841, when the Saints were enjoying relative quiet, peace, and even general political support in Illinois—Joseph Smith was already expressing the fear of a future violent attack on the Saints by their enemies, even using the massacre at Hawn’s Mill to explain a revelation from the Lord that had called the Saints to move to communities in the immediate vicinity of Nauvoo to prevent such attacks on far-flung and isolated settlements.[4]

As the 1844 presidential election approached, Joseph Smith sent letters to all of the politicians thought most likely to stand for the presidency at their respective party conventions. The letters were direct:

As the Latter Day Saints . . . have been robbed of an immense amount of property, and endured nameless sufferings by the State of Missouri, and from her borders have been driven by force of arms, contrary to our National Covenants; and as in vain, we have sought redress by all Constitutional, legal and honorable means, in her Courts, her Executive councils, and her Legislative Halls; and as we have petitioned Congress to take cognizance of our sufferings without effect; we have judged it wisdom to address you this communication, and solicit an immediate, specific & candid reply To what will be your rule of action relative to us, as a people.[5]

Senators John C. Calhoun, Lewis Cass, and Henry Clay all replied that while they sympathized with the suffering the Latter-day Saints had experienced, they could not commit to help the Latter-day Saints if they were to become president. Henry Clay’s letter stung Joseph most of all, as Joseph had already gone on record in an interview a few months earlier that he intended to vote for the Kentucky senator.[6] While Clay expressed regret for the Latter-day Saint difficulties, he flatly stated, “I can enter into no engagements, make no promises, give no pledges, to any particular portion of the people of the U. States.”[7]

With most of the potential future presidents’ on-record refusals to help the Saints in their decade-long quest for redress of grievances for stolen land, vicious assaults, and outright murders in Missouri, Joseph Smith made two fateful decisions. First, he declared his own presidential candidacy, adopting a platform that attempted to bridge the partisan chasm between Democrats and Whigs on several issues. While much of his platform was practical, moderate, and widely appealing, other positions were radical in the political world of the 1840s. Having had personal experience with the horrendous conditions of prisoners in the hellish purgatory of Liberty Jail, Joseph advocated for prison reform, urging Americans, “Petition your state legislatures to pardon every convict in their several penitentiaries: blessing them as they go, and saying to them in the name of the Lord, go thy way and sin no more.”[8]

More radical still were the opening lines of his presidential platform. In a day and age when both major parties avoided the topic of slavery and its expansion as much as possible, Joseph Smith threw down the gauntlet. He mocked the fact that the United States was supposedly a land patterned after the Declaration of Independence, in which “all men are created equal . . . but at the same time, some two or three millions of people are held as slaves for life, because the spirit in them is covered with a darker skin than ours.” He proceeded to argue that the government should speedily purchase every slave from their masters so the dreadful institution would be defunct in six years.[9]

While Joseph Smith hoped his candidacy would bring attention to the Latter-day Saint cause and to the deficiencies of the federal government when it came to protecting minority rights, he had also begun to prepare for a much more practical and long-term solution to the incessant injustice they believed had been visited upon them by local, state, and federal politicians. By early 1844, Joseph had made the decision that the Latter-day Saints would need to abandon the United States.

Shortly after announcing his candidacy, Joseph Smith’s diary recorded, “I instructed the 12 to send out a delegation & investigate the locations of California and Oregon to find a good location where we can remove after the Temple is completed & build a city in a day and have a government of our own.” While publicly he was campaigning to become the chief executive of the United States, privately he was preparing to leave the United States altogether, convinced that the rights of his despised religious minority could not be protected in the face of overwhelming persecution and political pusillanimity and corruption.[10]

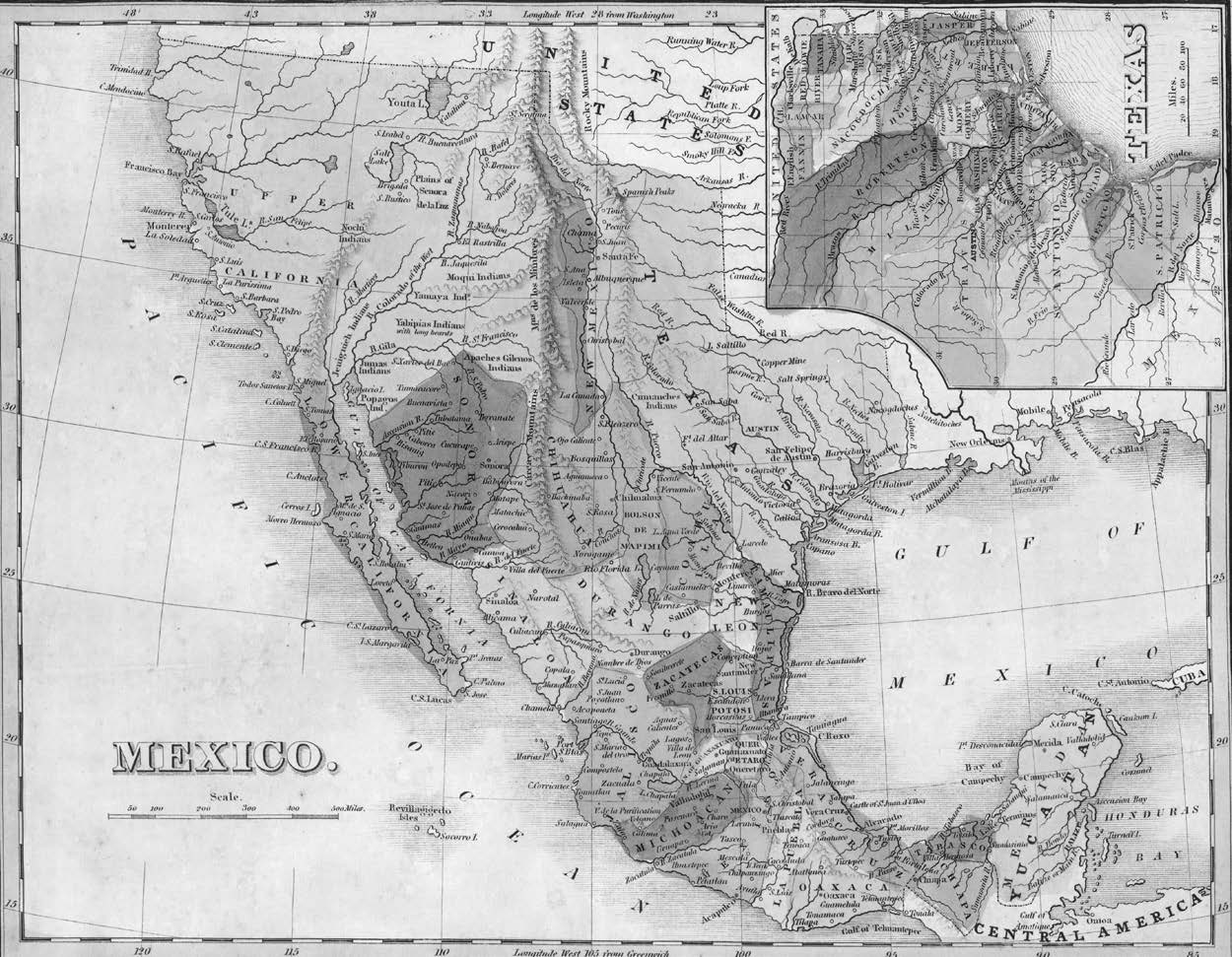

Map of Mexico and Texas, 1844. David Rumsey Map Collection.

Map of Mexico and Texas, 1844. David Rumsey Map Collection.

As his journal entry indicated, Joseph was strongly contemplating a move to the vast reaches of Mexican California, which in 1844 included all of the present states of California, Nevada, Utah, Arizona, and parts of Colorado and Wyoming. Some followers suggested that the Saints move to the Republic of Texas, which had won its independence from Mexico nearly a decade earlier. Texas had maintained a tenuous existence in the face of Mexican refusal to honor Texan independence, culminating in multiple invasions of Texas by Mexican forces in the early 1840s. While Texas president Sam Houston was fervently trying to secure American annexation of Texas to stave off an eventual Mexican reassertion of control, his efforts had thus far been met with marked political opposition, both from those who refused to expand the slaveholding territory of the United States, and others who held no moral compunctions about slavery but understood that the annexation of Texas (which Mexico still claimed as part of its own nation) would surely lead to war.[11]

In March 1844, Joseph Smith formed a secretive council that would come to be known as the Council of Fifty. Its purpose was to seek out a place—in either Texas, Mexico, or the Oregon Territory—for the Saints to escape the persecuting sovereignty of the United States and establish their own nation where they were free to practice their religion. The council “agreed to look to some place where we can go and establish a Theocracy either in Texas or Oregon or somewhere in California.”[12]

The council dispatched Lucian Woodworth to travel the nearly one thousand miles to the Republic of Texas to negotiate with President Sam Houston.[13] Surprisingly, though he was initially hesitant, Houston embraced the idea of Latter-day Saint settlement in the disputed territory between Texas and their archnemesis, Mexico. Indeed, he would write to prominent Latter-day Saint and former U.S. Army officer James Arlington Bennet to persuade the Saints to move to Texas. Understanding both the tortured past of the Latter-day Saints in the United States and their resultant fears of unprincipled or ineffective sovereignty, Houston insisted that “if the Saints were in Texas then their religious & Civil rights should have the most ample protection.” While antagonists decried the specter of Latter-day Saint military power embodied in the Nauvoo Legion, Houston explained that “he would receive the ‘Mormon Legion’ in Texas as armed Emigrants with open Arms.” Determined to eliminate the fear of continued religious persecution and oppression, Houston flatly asserted, “I am no bigot.”[14]

While the option of moving to the Republic of Texas was taken very seriously, the men in the Council of Fifty simultaneously discussed and prepared for the possibility of moving to move to the Mexican lands containing the Rocky Mountains. Part of their efforts were directed at drafting a new constitution to govern them in the kingdom they intended to set up wherever they eventually went. The daunting task of drafting a constitution for the kingdom of God weighed heavily on them, and Joseph Smith counseled them to “get knowledge, search the laws of nations and get all the information they can.” They were indeed planning to set up a special type of theocracy, one in which the “people get the voice of God and then acknowledge it, and see it executed.”[15]

Though it would be the kingdom of God, this theocracy would have religious freedom as a fundamental component—unlike the failed protections proffered by U.S. law. Joseph Smith told the men of the council, “We act upon the broad and liberal principal that all men have equal rights, and ought to be respected, and that every man has the privilege in this organization of choosing for himself voluntarily his God, and what he pleases for his religion.” Joseph reaffirmed a belief that he had expressed on several occasions previously: he was not afraid of people being drawn away to another religious truth because the Church had the greatest light and “every man will embrace the greatest light.” He continued, “God cannot save or damn a man only on the principle that every man acts, chooses and worships for himself; hence the importance of thrusting from us every spirit of bigotry and intollerance towards a mans religious sentiments, that spirit which has drenched the earth with blood.” Indeed, Joseph asserted that it was “the inalienable fight of man” to think and worship as he pleases. Thoughtfully, he taught, “We must not despise a man on account of infirmity. We ought to love a man more for his infirmity.”[16]

Joseph Smith wanted the Council of Fifty to understand that as they undertook the task of creating a new nation, their love for others was not to be constrained on the basis of whether or not someone embraced the Church and joined it. “Let us from henceforth drive from us every species of intollerance,” Joseph declared, “When I have used every means in my power to exalt a mans mind, and have taught him righteous principles to no effect [and] he is still inclined in his darkness, yet the same principles of liberty and charity would ever be manifested by me as though he embraced [the gospel].” Joseph insisted that any man that will “stand by his friends, he is my friend.” And with a dark allusion to his own rapidly approaching death, he added, “The only thing I am afraid of is, that I will not live long enough to enjoy the society of these my friends as long as I want to.”[17]

Whatever Joseph Smith’s detractors thought of him, on the point that his death was rapidly approaching, Joseph did indeed prove to be prophetic. As plans to leave the country continued to unfold, events rapidly spiraled out of control. Several opponents had rejected his more radical teachings on plural marriage and the idea that God had progressed to become God and aired their grievances, mincing no words, in the Nauvoo Expositor. Joseph Smith acted on an order from the Nauvoo city council to have the paper destroyed, declaring it a public nuisance. The Saints’ brazen destruction of the Expositor caused long-simmering antagonisms directed at the Saints to explode violently into a public crisis.

As demands were made for Joseph and Hyrum Smith to surrender themselves to be tried outside of Nauvoo, Joseph Smith made one last appeal to the president of the United States, John Tyler. “Sir,” Joseph appealed, “I am sorry to say that the State of Missouri, not contented with robbing, driving, and murdering many of the Latter day Saints, are now joining the mob of this state for the purpose of the ‘utter extermination of the Mormons.” Joseph implored of Tyler, “Will you render that protection which the constitution guarantees . . . and save the innocent and oppressed from such horrid persecution?”[18] What issued from Washington on this occasion, as with Joseph Smith’s previous appeals, was a deafening silence.

Two days later, preparing to surrender himself to the governor’s forces despite his premonitions that he and the others could not be protected by them, Joseph Smith reportedly gave his last public sermon, blessing the Nauvoo Legion and declaring, “You will gather many people into the fastness of the Rocky Mountains.”[19]

The murder of the Smiths in the mob attack on Carthage Jail five days later devastated the Latter-day Saints. In their grief, and with even more evidence that neither the state of Illinois nor the U.S. government would or could intervene to protect them from the growing calls for mob violence and outright murder, Church leaders planned to bring Joseph Smith’s intended abandonment of the United States to fruition. The new leader of the Church, Brigham Young, the President of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, responded indignantly to the continued persecution of the Saints, declaring, “The nation has severed us from them in every respect, and made us a distinct nation just as much as the Lamanites, and it is my prayer that we may soon find a place where we can have a home and live in peace according to the Law of God.”[20] A few months later, as the Council of Fifty continued to prepare for an exodus from the United States, Young further explained, “The gentiles have rejected the gospel; they have killed the prophets, and those who have not taken an active part in the murder all rejoice in it and say amen to it, and that is saying that they are willing the blood of the prophets should be shed. The gentiles have rejected the gospel, and where shall we go to preach. We cannot go any where but to the house of Israel. We cant get salvation without it. We cant get salvation any where else.”[21] In their view, the institutions of the United States had spectacularly failed the Saints, a conclusion that the increasing hostility and mob violence of 1845, combined with the repeal of the Nauvoo City Charter, further reinforced. The Saints, Young asserted, needed to “get out of the jurisdiction of the United States.”[22]

Increasingly, the U.S. government was coming to be seen by the Saints as not just an incompetent steward, clumsily inept at protecting its citizens from lawlessness, but rather as an active participant in persecuting the Saints and driving them from the nation. By March 1845, Brigham Young concluded, “If we can get one hundred miles beyond the jurisdiction of the United States we are safe, for the present, and that is all we ask, . . . we want to get between some of those Mountains where we can fortify ourselves and erect the standard of liberty on one of the highest mountains we can find.” Paradoxically for this native-born American, liberty could only be found outside of the “Land of the Free.”[23]

Apostle John Taylor, his body permanently scarified by the mobocratic bullets that had nearly killed him in Carthage Jail as Joseph and Hyrum Smith were murdered, had no more patience with the supposedly just political institutions of the United States, “We know we have no more justice here . . . than we could get at the gates of hell.” The Saints had been “excluded from all our rights as other citizens” and Taylor, like Young, wanted to leave the nation and find a place where they could “dwell in peace, and have our own laws.”[24]

The annexation of the Republic of Texas to the United States in early 1845 ended Latter-day Saint contemplations of a possible removal there. The Saints had already learned by sad experience that their rights could not be protected inside the sovereignty of the United States. If they were to have freedom, they would need to leave the United States.

Throughout 1845, while Brigham Young was dealing with the realities of real or threatened mob violence in Illinois, he was also continually receiving reports from Washington that the federal government would intervene on the side of their enemies, prevent them from leaving the nation, and arrest the leaders of the Church for various purported crimes. One chilling report in particular from the president of the Eastern States Mission and Jesse Little’s predecessor, Samuel Brannan, spurred this belief. Brannan had written to Young from Washington, DC, to explain that the “secretary of war and other members of the cabinet were laying plans” to stop the Latter-day Saints from moving to the Rocky Mountains of Mexican California. “They say,” Brannan gravely wrote, “it will not do to let the Mormons go to California nor Oregon, neither will it do to let them tarry in the states, and they must be obliterated from the face of the earth.”[25]

The Latter-day Saints demonstrated their displeasure at the apparently bigoted treatment they continued to receive in the Land of Liberty by boycotting the Fourth of July in 1845. Irene Haskell, a young married Latter-day Saint in Nauvoo, bitterly reflected to her parents her personal protest, “The fourth of July is just past. I suppose there were balls, teaparties and the like in the east, but here there were nothing of the kind. The Mormons think the liberty and independence of the Unites States has been too long trampled upon to be celebrated.”[26] Such attempts to express frustration at the injustice inflicted upon them seemed to only bolster the negative opinions that antagonists already held against the Latter-day Saints. One Pennsylvania newspaper took this as proof of Latter-day Saint perfidy, writing that in Nauvoo, “that city of fanatics . . . no notice was taken” of the Fourth of July at all. The writer failed to inform his readers that the Latter-day Saints had boisterously celebrated the holiday in previous years in Nauvoo.[27]

By October 1845, violence was no longer threatened but had become reality. One journalist explained that the local mobs had been “out burning the Mormon houses, barns, stacks, etc. In this war of extermination, they include not only the Mormons, but all who are suspected of favoring the Mormon cause or harboring Mormons about them.” Indeed, these American citizens had “determined to drive the Mormons out of the county” whether or not they were individually guilty of any crimes in a type of ethnic cleansing the Saints had already experienced in Missouri.[28] This renewed violence even resulted in the murder of Edmund Durfee, a Latter-day Saint living in the Yelrome (Morely) settlement. In 1831 Durfee had become one of the earliest converts to the Church and had persisted through the apostasies of Kirtland and the mobs and murders in Missouri only to be slaughtered in the Latter-day Saint settlement not far from Nauvoo, just months before the Saints had intended to leave. Durfee’s story after joining the religion—persecution culminating in murder—seemed a fitting representation of the wider story arc of Latter-day Saints in the United States.

The end of the Saints’ stay in Nauvoo came faster than Brigham Young had anticipated. They had agreed with local antagonists and state leaders to leave Nauvoo in the spring and to try to maintain a fragile and one-sided peace. But Governor Thomas Ford of Illinois, attempting to hasten the Latter-day Saint exodus, fabricated a lie so powerful in its implications that hundreds would indirectly die as a result. Ford indicated to Latter-day Saint leaders that he had learned that U.S. government forces were headed for Nauvoo with the intent of preventing the Saints from leaving the United States for the Mexican territory that they had determined to settle in. An army was indeed en route, he claimed. It awaited only the breakup of the ice on the Mississippi River so that it could steam upstream from Saint Louis and intercept the Saints.[29] In his later book, Ford boasted about the duplicity that would send women and children streaming across a frozen river and into the Iowa wilderness, not wholly prepared, as all of the Latter-day Saints feared a repeat of the assaults, murders, and atrocities that had accompanied military intervention in Missouri. Thinking history would view him favorably for his sagacious plan, Ford claimed his blood-stained credit: “With a view to hasten their removal they were made to believe that the President would order the regular army to Nauvoo as soon as the navigation opened in the spring. This had the desired effect; the twelve, with about two thousand of their followers immediately crossed the Mississippi before the breaking up of the ice.”[30]

Thus, as the Latter-day Saints struggled across Iowa while burying dozens along the way, they believed not only that their nation had refused to intervene on their behalf as Joseph Smith had so often begged but that their erstwhile nation was also actively taking a part in their attempted extermination. They believed that the halls of Washington were not just silent but were thundering with even greater threats of violence and persecution.

While President James K. Polk was not guilty of the actions Ford had dishonestly imputed to him, he did indeed see the Saints as less-than-American citizens and as a possible impediment to his planned invasion of Northern Mexico. His meetings with Jesse Little in early June 1846 and the subsequent enlistment of the Mormon Battalion were indeed part of wider duplicitous political machinations directed against the Latter-day Saints. Although the Saints would reach their new mountain home in the desert high places of Mexico, temporarily free of the corrupt political institutions that had driven them there, their respite was to be short-lived. American imperialism and sovereignty expanded faster than the Latter-day Saints could run from it. Throughout the remainder of the nineteenth century, clashes between the Latter-day Saints and the federal government over issues of individual liberty, voting rights, and religious freedom and sovereignty would characterize a difficult and painful interaction.[31] The hoped-for kingdom of God—a popular Latter-day Saint theocracy—was not realized, and Saints had to look forward to a day when they believed political conflicts, like all other conflicts, would cease with the promised return of the Messiah.

Notes

[1] For an excellent historical investigation of the events and politics surrounding the conflict, see Amy Greenberg, A Wicked War: Polk, Clay, Lincoln, and the 1845 Invasion of Mexico (New York: Knopf, 2012).

[2] James K. Polk Papers, Diary, no. 4, 3 June 1846, Library of Congress; and Report of Jesse Carter Little to President Brigham Young and the Council of the Twelve Apostles, 6 July 1846, 22, Manuscript History of the Church (MHC), Church History Library (CHL).

[3] Polk, Diary, 3 June 1846, Library of Congress.

[4] Brent M. Rogers, Mason K. Allred, Gerrit J. Dirkmaat, and Brett D. Dowdle, eds., Documents, Volume 8: February–November 1841, vol. 8 of the Documents series of The Joseph Smith Papers, ed. Ronald K. Esplin, Matthew J. Grow, Matthew C. Godfrey, and R. Eric Smith (Salt Lake City: Church Historian’s Press, 2019) 70.

[5] Joseph Smith to Presidential Candidates, 4 November 1843, MS 155, CHL.

[6] “The Prairies, Nauvoo, Joe Smith, the Temple, the Mormons &c.,” Pittsburgh Weekly Gazette, 30 August 1845.

[7] Henry Clay to Joseph Smith, 15 November 1843, CHL.

[8] Joseph Smith, General Smith’s Views of the Powers and Policy of the Government of the United States (Nauvoo: John Taylor, 1844), 6.

[9] Smith, General Smith’s Views, 1 and 7.

[10] Joseph Smith, Journal, 20 February 1844, MS 155, CHL.

[11] For a detailed examination of the events leading up to the annexation of the Republic of Texas, see Joel H. Sibley, Storm Over Texas: The Annexation Controversy and the Road to the Civil War (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005).

[12] Council of Fifty record books 1844–1846 (COFRB), 11 March 1844, MS 30055, box 1, folder 1, CHL. These records have also been published in Matthew J., Grow, Ronald K. Esplin, Mark Ashurst-McGee, Gerrit J. Dirkmaat, and Jeffrey D. Mahas, eds., Council of Fifty, Minutes, March 1844–January 1846, vol. 1 of the Administrative Records series of The Joseph Smith Papers, ed. Ronald K. Esplin, Matthew J. Grow, and Matthew C. Godfrey (Salt Lake City: Church Historian’s Press, 2016).

[13] For more detail surrounding the Latter-day Saint negotiations with Texas and other areas debated by the Council of Fifty, see “Safely ‘Beyond the Limits of the United States’: The Mormon Expulsion and US Expansion,” in Inventing Destiny: Cultural Explorations of US Expansion, ed. Jimmy Bryan (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, September 2019).

[14] James Arlington Bennet to Willard Richards and Brigham Young, 4 June 1845, Willard Richards Papers, MS 1490, CHL.

[15] COFRB, 11 April 1844.

[16] COFRB, 11 April 1844.

[17] COFRB, 11 April 1844.

[18] Joseph Smith to John Tyler, 20 June 1844, CHL.

[19] Joseph Smith, Discourse, 22 June 1844, reported by Alfred Bell and copied into the William Pace notebook, William Pace Papers, CHL.

[20] William Clayton, Journal, 26 January 1845, as cited in JSP, CFM:258.

[21] COFRB, 1 March 1845. Young’s reference to the House of Israel is a reflection of his belief that American Indians were decedents of ancient Israelites.

[22] COFRB, 11 March 1845.

[23] COFRB, 18 March 1845.

[24] COFRB, 1 March 1845.

[25] Samuel Brannan to Brigham Young, 11 December 1845, MHC, CHL.

[26] Irene Haskell, Letter to Parents, 6 July 1845, Irene Haskell Papers, Library of Congress.

[27] “Fourth of July in Nauvoo,” Pittsburgh Weekly Gazette, 16 July 1845.

[28] “Mormon War,” Indiana Palladium (Richmond), 4 October 1845.

[29] Thomas Ford to Sheriff J. B. Backenstos, 29 December 1845, CR 1234 1, CHL.

[30] Ford, History of Illinois, 291.

[31] For an excellent historical work describing some of these interactions, see Brent M. Rogers, Unpopular Sovereignty: Mormons and the Federal Management of Early Utah Territory (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2017).