Latter-day Saints in the National Consciousness: The Seating of Senator Reed Smoot

Casey Paul Griffiths

Casey Paul Griffiths, “Latter-day Saints in the National Consciousness: The Seating of Senator Reed Smoot,” in Latter-day Saints in Washington, DC: History, People, and Places, ed. Kenneth L. Alford, Lloyd D. Newell, and Alexander L. Baugh (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book), 181‒204.

Casey Paul Griffiths was an assistant teaching professor of Church history and doctrine at Brigham Young University when this was published.

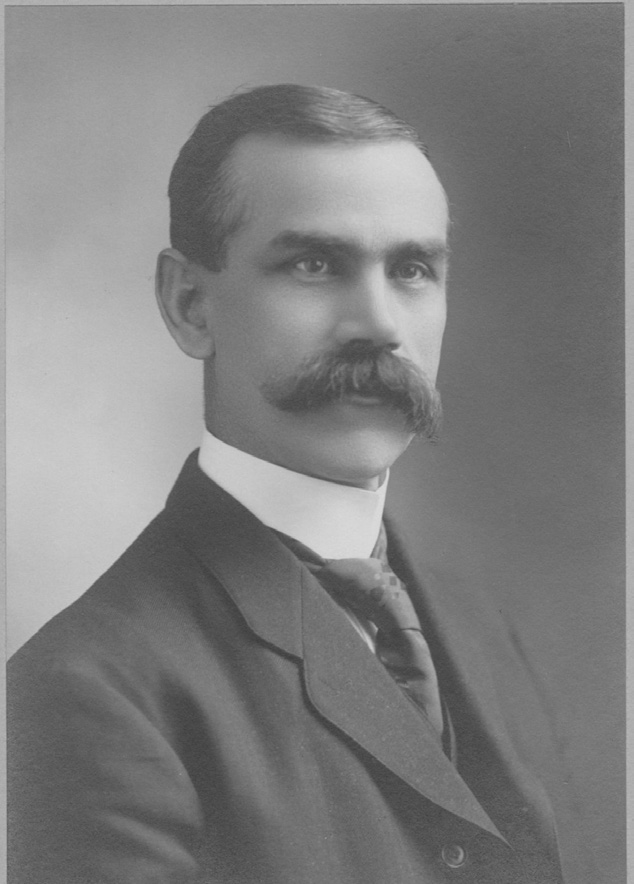

Senator Reed Smoot. Reed Smoot Papers, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University.

Senator Reed Smoot. Reed Smoot Papers, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University.

Reed Smoot burst onto the national scene in the middle of a crucial transformation for the Latter-day Saints.[1] The Manifesto of 1890 had begun the gradual end of plural marriage in the Church, moving the Saints closer to mainstream American life. The 1896 entry of Utah into the Union further pushed the Saints into the national spotlight. Following the inauguration of statehood for Utah, Latter-day Saint soldiers fought alongside compatriots in the Spanish-American War.[2] In the early 1900s, the Saints’ isolation seemed to have ended, and Latter-day Saints occupied positions in local and state governments throughout the West. However, a crucial question remained: Could a believing Latter-day Saint occupy a position in the federal government of the United States?

Reed Smoot sought to answer this question with his candidacy for a seat in the U.S. Senate. His eventual election led to national uproar and a series of hearings during which Smoot’s involvement with the Church was questioned. The heated nature of the Smoot hearings cast the Church into an intense crucible of public examination. Plural marriage, Church finance, and even the sacred ordinances of the temple were thrust into the public spotlight. Church leaders responded to the controversy by working to clarify Church teachings and by bringing Church membership into line with official Church positions. As a result, the transformation in the Church started by the 1890 Manifesto intensified, and, in the end, the Church found greater acceptance in the eyes of many Americans. Though the Saints’ isolation from mainstream America effectively started to diminish with the dissolution of plural marriage, the Smoot hearings accelerated the process by intensely involving the public eye in the internal processes of the Church.

Reed Smoot around the time of the Senate hearings. Reed Smoot Papers, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University.

Reed Smoot around the time of the Senate hearings. Reed Smoot Papers, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University.

The hearings, spread out over four years, created a 3,500-page record of the testimonies of one hundred witnesses on every facet of the Latter-day Saints’ lives, practices, and beliefs. At the peak of the hearings, some senators received a thousand letters a day from outraged citizens. The record of these public petitions today fills eleven feet of shelf space in the National Archives, the largest collection of its kind.[3] The hearings were also well documented by Reed Smoot himself, who kept a detailed scrapbook of many of the public articles supporting, opposing, and documenting his seating in the U.S. Senate. A full review of all the material related to the hearings is not possible in this format. Despite the overwhelming amount of material, a brief review of the events of the Smoot hearings is vital in understanding this important episode in the development of the national identity of the Latter-day Saints.

Latter-day Saints and the United States Government

Reed Smoot was not the first active Latter-day Saint elected to a position in the federal government. Frank J. Cannon,[4] who later became a Church antagonist, was an active Church member at the time of his election to the U.S. Senate (1896). He was seated in the Senate without much controversy. W. H. King, another active Latter-day Saint, served one term and part of another in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1896 to 1898.[5] However, trouble began brewing with the election of B. H. Roberts to the House of Representatives in 1898. Roberts was denied his seat because he was married to three women, one of whom he married after the 1890 Manifesto. A petition bearing seven million signatures was delivered to Congress—the greatest number of Americans to ever seek congressional action—demanding the denial of Roberts’s place in the House. Roberts eloquently defended his place in the government; visiting British writer H. G. Wells even noted, “Mr. Roberts stood like a giant and defended himself and his Church. I never heard a more eloquent or cogent speaker in all my travels.”[6] Unfortunately, the public’s pressure was too much, and congressional leaders barred him from serving.[7] The controversy surrounding Roberts was linked to his identity as a polygamist and his place in Church hierarchy, where he served as a member of the First Council of the Seventy. Roberts also did not seek the approval of Church leadership before he ran for office, a move that led Church leaders to provide him with only lukewarm support.[8] When he fought the might of the U.S. government, he fought alone.

Senator Smoot (left) in front of the United States Capitol. Reed Smoot Papers, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University

Senator Smoot (left) in front of the United States Capitol. Reed Smoot Papers, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University

When Reed Smoot announced his candidacy in 1902, questions swirled around his chance of taking a seat in the Senate. Like Roberts, Smoot was a leader in the Church. He was called to serve in the Quorum of the Twelve in April 1900. Unlike Roberts, however, Smoot was a monogamist, married to Alpha Mae Eldredge in 1884. Smoot also went to great lengths to secure the approval and support of Church President Joseph F. Smith in Smoot’s run for office. President Smith felt strongly that Smoot’s senatorial service would serve to further the purposes of the Church. At the height of the Smoot controversy, Charles W. Nibley, a close friend of President Smith, attempted to persuade the Church President to withdraw his support. Nibley recalled that President Smith brought down his fist and declared, “If I have ever had the inspiration of the spirit of the Lord given to me forcefully and clearly it has been on this one point concerning Reed Smoot, and that is that instead of his being retired, he should be continued in the United States Senate.”[9] Reed Smoot would serve in the Senate with the full support of Church leadership, which was certainly needed. Almost immediately after his election in 1902, the battle began.

Early Attacks on Senator Smoot

The campaign against Smoot began with a meeting of the Salt Lake Ministerial Association, held on 24 November 1902. At the meeting, fifteen ministers representing several Protestant churches in Salt Lake City passed a resolution opposing Smoot’s election. A few weeks later, the Reverend J. L. Leilich, head of Methodist missions in Utah, accused Smoot of secretly being a polygamist. Leilich refused to provide the name of Smoot’s supposed plural wife but publicly accused the Church of performing the plural marriage and holding a “secret record [that] is in exclusive custody and control of the First Presidency and the quorum of the Twelve Apostles.”[10] Joseph F. Smith quickly responded “that there is not one word of truth in the assertion that Reed Smoot is or has been a polygamist, or that he has married a plural wife either since or before Utah became a state.”[11]

Leilich’s charge was a blatant untruth, but it raised the specter of polygamy and brought up a significant number of charges in the Senate. Smoot was quick to recognize the stakes of the protest. In a letter to the president of the Eastern States Mission, he wrote,

The Ministers will have to show their hand to get anywhere and then the people of the United States will know and realize that it is not a fight against Reed Smoot, but that it is a fight against the authority of God on earth and against the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. . . . If this gang wins in this fight you can depend upon it that it will be only a stepping stone to disbar every Mormon from the halls of Congress. If they can expel me from the Senate of the United States they can expel any man who claims to be a Mormon.[12]

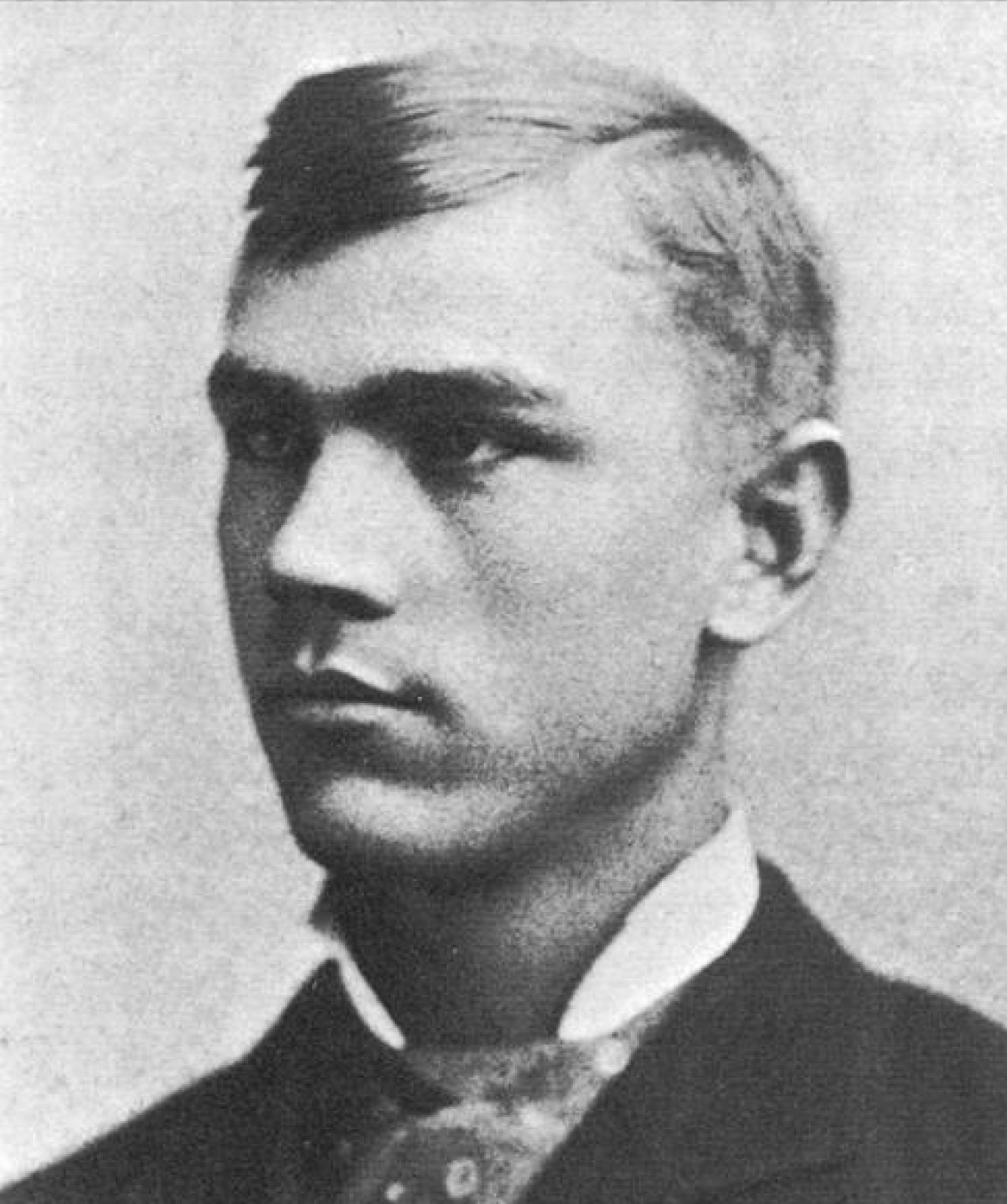

Young Reed Smoot. The Smoot trials included an extensive airing of the Latterday Saint temple rituals. Reed Smoot Papers, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University.

Young Reed Smoot. The Smoot trials included an extensive airing of the Latterday Saint temple rituals. Reed Smoot Papers, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University.

Within a year, more than thirty-one hundred petitions had arrived in Washington, DC, requesting Reed Smoot’s removal from the Senate. During the summer of 1903, articles and editorials appeared throughout the country making similar calls for Smoot’s ouster. The New York Sun declared a “War on Senator Smoot” and quoted the leader of an interdenominational women’s club who said, “We will fight Apostle Smoot and defeat him. It is remarkable how easy it is to touch public feeling on the subject. . . . An Eastern audience today is like a bundle of combustible material, and the question of polygamy is like a lighted match.”[13] The Pittsburgh Gazette declared “Smoot’s Toga is in Danger” and painted Smoot’s senatorial service as part of a conspiracy to reinstitute plural marriage. An editorial in the paper charged, “The reason for the contest is that the Mormon church is using its tremendous power and influence to gain political control, not only in Utah, but in all the Western States where it has a following. . . . Christian people firmly believe that the Mormons are only waiting until they are strongly in power to again preach the doctrine of plural marriages.”[14]

The revival of sentiment against the Church eventually led to the launch of a series of Senate hearings lasting from 1904 to 1907 that called into question nearly every practice and teaching of the Church. Historian Harvard S. Heath summarized the aim of the hearings: “The prosecution focused on two issues: Smoot’s alleged polygamy and his expected allegiance to the Church and its ruling hierarchy, which, it was claimed, would make it impossible for him to execute his oath as a United States senator. Though the proceedings focused on senator-elect Smoot, it soon became apparent that it was the Church that was on trial.”[15] Historians and even Smoot himself have agreed that the hearings were aimed at the Church and not at Smoot; Smoot was told this directly. In a letter to a friend, Smoot wrote, “Chairman [Julius C.] Burrows today very frankly told me, and has done so on several occasions, that I was not on trial, but that they were going to investigate the Mormon Church.”[16]

Investigating Plural Marriage

Because the hearings seemed to probe Latter-day Saints broadly instead of just Smoot himself, it makes sense that the first witness called to the stand during the hearings, and the one who created the greatest sensation in the national media, was Joseph F. Smith, the President of the Church. Over the course of six days, President Smith was interrogated about the finances, doctrines, and practices of the Church. A memorable exchange took place when Massachusetts senator Joseph Hoar questioned President Smith about the scriptural basis for plural marriage:

Senator Hoar: Now I will illustrate what I mean by the injunction of our scripture—what we call the New Testament.

Mr. Smith: Which is our scripture also.

Senator Hoar: Which is your scripture also?

Mr. Smith: Yes sir.

Senator Hoar: The apostle says that a bishop must be sober and be the husband of one wife.

Mr. Smith: At least.[17]

Putting humor aside, President Smith staunchly defended the sincerity of the Manifesto, telling the prosecutors, “It has been the continuous and conscientious practice and rule of the church ever since the manifesto to observe that manifesto with plural marriages.”[18]

More than a decade after the Manifesto was issued, the Reed Smoot trials sensationalized the practice of plural marriage. Reed Smoot Papers, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University.

More than a decade after the Manifesto was issued, the Reed Smoot trials sensationalized the practice of plural marriage. Reed Smoot Papers, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University.

The most dramatic moment of Smith’s testimony—and perhaps of the entire hearings—took place when President Smith was asked about his own families. He told the audience that he still lived with and took care of his polygamous wives and the children from their unions. President Smith felt that marriages carried out before the Manifesto were still legitimate, and therefore he acted in opposition to the law. He told the prosecutors, “I simply took my chances preferring to meet the consequences of the law rather than to abandon my children and their mothers; and I have cohabited with my wives, not . . . in a manner that I thought would be offensive to my neighbors—but I have acknowledged them; I have visited them. They have borne me [eleven] children since 1890, and I have done it, knowing the responsibility and knowing that I was amenable to the law.”[19] In other testimonies given in the hearings, other Church leaders, including Francis M. Lyman, Clara M. B. Kennedy, and Charles E. Merrill, admitted to continued cohabitation after the Manifesto.[20]

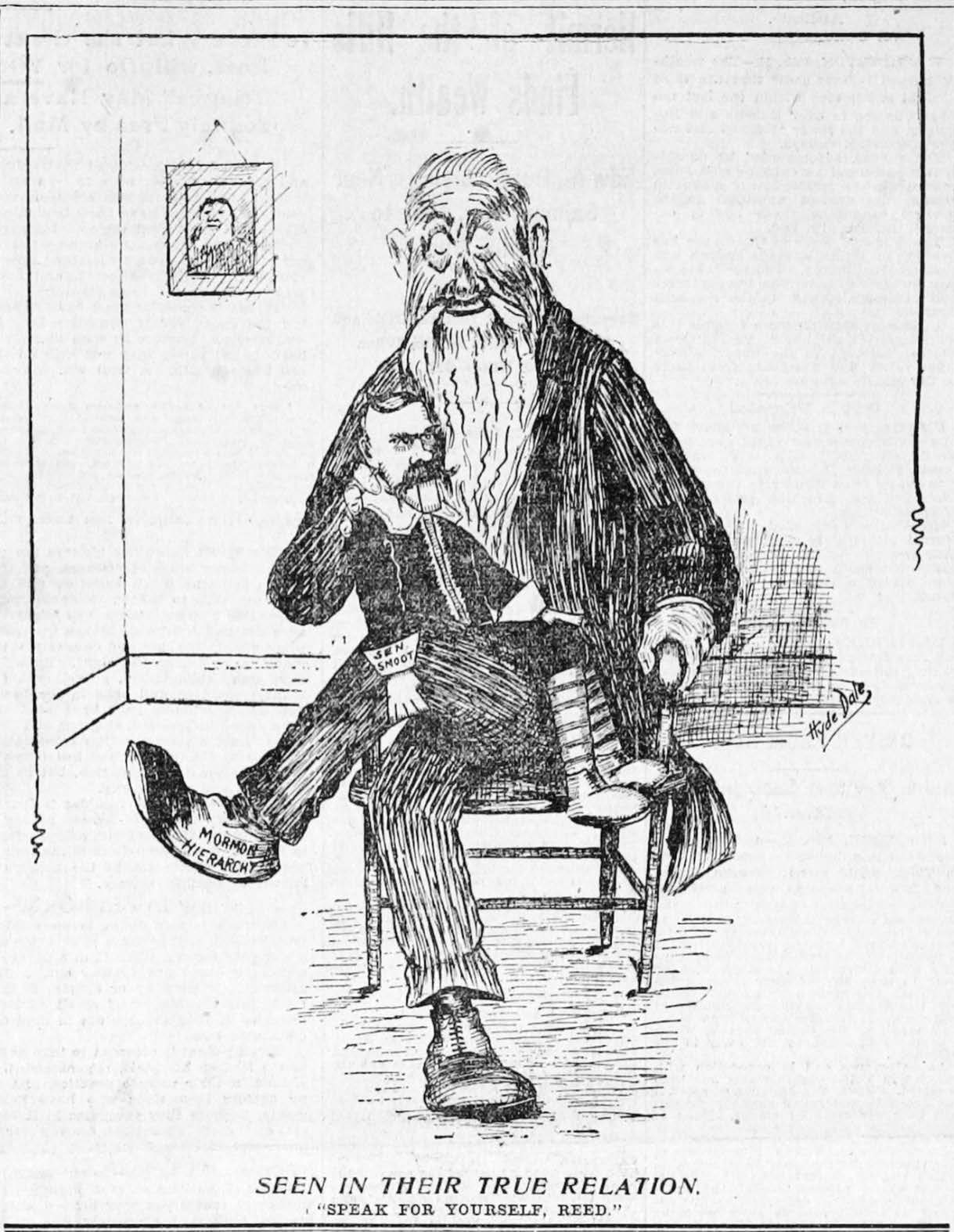

The admissions caused a firestorm of controversy throughout the country. President Smith was caricatured in the national media as a sinister manipulator of Smoot and the locus of all negative charges fixed on the Church. In a cartoon appearing in Collier’s Weekly, President Smith was depicted in a striped prison outfit with a ball and chain attached to his foot, portraying him as “a dissipated and convicted criminal.”[21] Even Smoot acknowledged how devastating President Smith’s testimony was to the public image of the Church. “The testimony of Joseph F. Smith has startled the nation,” he wrote to a friend, “and the papers are having a great deal to say about the lack of faith on the part of the Mormon people with the government of the United States.”[22]

The hearings highlighted the difficulty in ending the practice of plural marriage within the Church. The ambiguity of the 1890 Manifesto caused confusion on the part of some Church members. It did not address the subject of continued cohabitation of pre-Manifesto marriages or the provision of emotional and financial support for plural families. In a closed-door meeting after the Manifesto was given, President Wilford Woodruff advised, “I did not, could not, and would not promise that you would desert your wives and children. This you cannot do in honor.”[23] While concern for the care of pre-Manifesto plural families was understandable, church members also struggled to give up the concept of polygamy after the Manifesto. There is significant evidence that a number of post-Manifesto plural marriages took place. A ledger of “marriages and sealings performed outside the temple” lists 315 marriages performed between 17 October 1890, and 8 September 1903. Of the 315 marriages recorded, 25 (7.9 percent) were plural marriages and 290 were monogamous (92.1 percent). Eighteen of the plural marriages from this time took place in Mexico, though there were also three in Arizona, two in Utah, and one in Colorado, along with one on a boat in the Pacific Ocean.[24] These marriages exhibit the struggle for individual Latter-day Saints at this time to conform to the teachings within the Manifesto.

The furor caused by the discussions of plural marriage in the Smoot hearings led to direct action in the Church. Realizing their approach to the end of plural marriage needed a more forceful method of enforcement, President Smith issued the “Second Manifesto,” making new plural marriages an excommunicable offense. In a general conference address, President Smith declared, “I hereby announce that all such [plural] marriages are prohibited, and if any officer or member of the Church shall assume to solemnize or enter into any such marriage, he will be deemed in transgression against the Church, and will be liable to be dealt with according to the rules and regulations thereof and excommunicated therefrom.”[25] This exchange eventually led to the removal of two members of the Quorum of the Twelve, John W. Taylor and Matthias Cowley, who admitted they had performed post-Manifesto plural marriages.[26]

While the Church tried to bring membership into accordance with the Manifesto’s teachings, the hearings continued. Reed Smoot never practiced plural marriage and, because of this, was somewhat insulated against the charges regarding plural marriage. During one exchange in the hearings, Senator Boies Penrose of Pennsylvania glared at some of his philandering colleagues impugning Smoot’s integrity and then quipped, “As for me, I would rather have seated beside me in this chamber a polygamist who doesn’t polyg than a monogamist who doesn’t monog.”[27] Senator Albert Hopkins of Illinois brought up questions about the dangerous precedent that might be set by denying an elected representative based on his religion. He declared, “Never before in the history of the government has the previous life or career of a Senator been called into question to determine whether or not he should remain in the Senate. . . . If members of any Christian Church were to be charged with all of the crimes that have been committed in its name where is the Christian gentleman who would be safe in his seat?”[28] In another essay written in Smoot’s defense, Senator Hopkins added, “The people of Utah have the same right to elect their Senator from the Mormon faith that the people of another State have to elect their Senator who is a member of the Methodist, Presbyterian, or Catholic Church.”[29]

Temple Ceremonies and Allegiance to the Church Hierarchy

In this cartoon appearing in the Salt Lake Tribune, 12 February 1905, Smoot is depicted as a puppet being manipulated by the Church hierarchy, caricatured here as President Joseph F. Smith. Utah Digital Papers.

In this cartoon appearing in the Salt Lake Tribune, 12 February 1905, Smoot is depicted as a puppet being manipulated by the Church hierarchy, caricatured here as President Joseph F. Smith. Utah Digital Papers.

Despite Smoot’s innocence on the charge of polygamy, his Church membership alone was reason enough to bar him from the Senate according to some people. In January 1905 the New York Press listed eight senators who deserved to have their place in the legislature removed. A picture of each of the accused lawmakers was shown with their crime listed below. Three of the senators were listed as “indicted.” Other charges included “accused of fraud,” “expulsion asked for,” and “financially embarrassed through trying to elect notorious addicks [sic] to the Senate.” The charge below Reed Smoot simply read “Mormon.”[30]

Perhaps knowing the practice of plural marriage was on the decline, Smoot’s opponents also centered on a more universal charge with far-reaching consequences. They began to make accusations that a Latter-day Saint who entered into the covenants of the temple was automatically guilty of sedition against the U.S. government. One article charged, “It is generally admitted in Utah that the priesthood, and all the leading spirits of the Mormon church are members of a secret oath-bound fraternity, whose chief meeting place is in the Temple at Salt Lake City. This massive stone edifice, sacred in the eyes of the followers of the ‘Prophet’ Joseph Smith, and it is the one building in Utah within which no Gentile may enter.”[31] An editorial appearing in the Salt Lake Tribune demanded Smoot answer a number of questions, including, “Have you taken an oath to avenge the blood of Joseph Smith upon this nation? Have you taken the endowment in the temple of the Mormon church or elsewhere? Have you taken the obligations which are given all who go through the endowment house?”[32] The implications of this line of questioning came with a more sinister motive. Where earlier attacks questioned the endurance of plural marriage, now the opposition was unmistakably implying that no temple-endowed Latter-day Saint could loyally serve the U.S. government.

The exploitation of temple liturgy in the Smoot hearings and the national media produced great discomfort among the Saints. A New York newspaper blared sensational headlines about “Death Penalties in Mormon Oath” and “Dead Married to Living” without attempting to explain or contextualize the temple ordinances.[33] In two major newspapers in California, photographs depicting temple clothing, oaths, and rites were splashed across whole pages.[34] A particularly difficult moment for Church supporters came late in the hearings when Walter W. Wolfe, a former teacher at Brigham Young College in Logan who left the Church in 1906, was called to the stand. Only two years earlier, Wolfe wrote a defense of Reed Smoot’s right to serve in the Senate, which appeared in the Church periodical the Millennial Star. But now Wolfe took the opportunity to speak out on temple covenants. Though Wolfe called the endowment “a very impressive ceremony,” he also declared his feelings that “in [the] covenant the seed of treason is planted.”[35]

During the hearings when Smoot was asked about the endowment oath, he downplayed his involvement in it. He mentioned receiving his endowment when he was eighteen, stating, “My father was going to visit the Sandwich [Hawaiian] Islands for his health, and he asked me to go with him.” He continued, “I of course was very pleased, indeed to accept the invitation, and before going my father asked me if I would go to the endowment house and take my endowments. I did not particularly care about it. He stated to me that it certainly would not hurt me if it did not do me any good, and that, as my father, he would like very much to have me take the endowments before I crossed the water or went away from the United States.”[36] When Smoot was asked directly what he would do if the laws of God conflicted with the laws of the land, he replied, “If the revelation were given to me, and I knew it was from God, that; that law of God would be more binding upon me, possibly than a law of the land, and I would do what God told me, if I were a Christian. . . . And I would further state this, that if it conflicted with the law of my country in which I live, I would go to some other country where it would not conflict.”[37]

When the hearings wrapped up in the spring of 1906, many news outlets crowed over the harsh exposure given to the Saints, their history, and their doctrine. The Baltimore Herald declared, “Morman Church Flayed; Smoot Report Goes In.”[38] The Salt Lake Tribune reveled in the scourging of the Church in the national scene, gleefully adding, “Reed Smoot’s ambition has brought more suffering to his people than the work of every opponent of the church in the land, . . . the destructive force of which, was never equaled by the ambition of any man in the history of the Republic.”[39] Smoot himself wondered if his ambition had wrought too heavy a price for the Church to pay. In a pleading letter written at the height of the hearings, Smoot wrote to Joseph F. Smith, “I would also like to suggest that the General Authorities of the church; meaning the Presidency, Apostles, First Presidents of Seventy, Patriarch, and Bishopric meet a day in the near future for fasting and prayer. I am sure it can do no harm and I fully believe it will do some good.” He expressed remorse over the role he played in the controversy, continuing, “If they think it is my ambition that has brought this trouble upon the church, I think they ought to have charity enough to ask God to forgive me.” At the same time, he added, “But I would like to impress upon them the fact that it is not me that is in danger, but the church.” He also asked Church leaders to pray to “prevent another crusade against her people; to save the liberties of our people.”[40]

While Smoot worried about the impact of his trial on the Church, he was not without defenders in the Senate. Illinois senator Albert Hopkins gave an impassioned defense of Smoot during the hearing. “It is conceded by the chairman of the committee on privileges and elections that Senator Smoot possesses all of the qualifications spoke of in the Constitution itself,” he argued. “It also conceded that he has never married a plural wife, and has never practiced polygamy. . . . Why then, should he be dispelled from this body, disgraced and dishonored for life, a stigma placed upon his children, his own life wrecked, and the happiness of his wife destroyed?” He concluded, “He is a Christian gentleman, and his religious belief has taken him into the Mormon church.”[41]

Outcome and Impact of the Smoot Hearings

The day of reckoning came at last on 20 February 1907. Final arguments were made in the Senate and a vote taken around four o’clock in the afternoon. When the votes were tallied, Smoot was allowed to retain his seat since his opponents failed to reach the necessary two-thirds majority to remove him from the Senate. In the end, thirty-nine Republican and three Democratic senators voted for Smoot to retain his seat.[42] Though a number of political factors affected the outcome, one of the most important elements in Smoot’s victory was his personal character. The hearings, drawn out over nearly three years, took place concurrent to Smoot’s service in the Senate. During that time, Smoot developed important relationships with party leaders, fellow senators, and President Theodore Roosevelt. Even Michigan senator Julius Burrows, one of Smoot’s primary antagonists, conceded that “the Senator [Smoot] stands before the Senate in personal character and bearing above criticism and beyond reproach.”[43] Senator Albert Hopkins, a Smoot advocate, stated, “Reed Smoot himself has never had but one wife. He is a model husband and father, an honest and upright citizen in every respect, and has made an honest, painstaking and conscientious official as a representative from his State in the Senate of the United States.”[44]

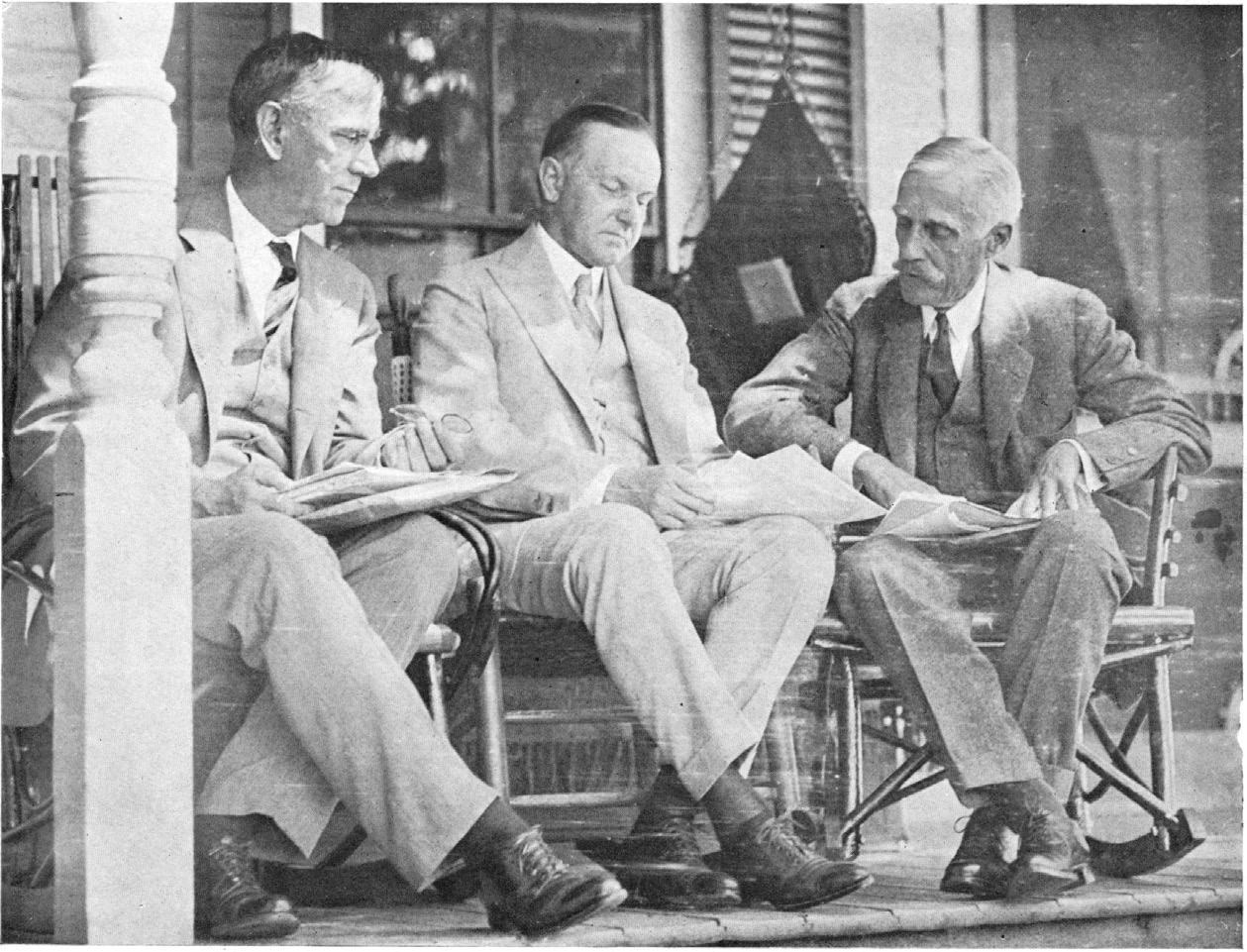

Senator Smoot (right) with President Calvin Coolidge (center). After a rocky start in his senatorial career, Reed Smoot became one of the most influential senators in Washington, DC. Reed Smoot Papers, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University.

Senator Smoot (right) with President Calvin Coolidge (center). After a rocky start in his senatorial career, Reed Smoot became one of the most influential senators in Washington, DC. Reed Smoot Papers, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University.

The crucible of the Smoot hearings brought pain and embarrassment to Church leaders and the general membership, but it also hastened the transformation of the Latter-day Saints started by the 1890 Manifesto and the entry of Utah into the Union in 1896. The Smoot hearings publicly purged Church leadership of outspoken proponents of plural marriage. The Second Manifesto, issued in 1904, gave Church leaders a method to enforce the end of plural marriage and hasten its demise in the Church.[45] A watershed moment came at the April 1906 general conference when three strong proponents of plural marriage in the Quorum of the Twelve—Marriner W. Merrill, John W. Taylor, and Matthias F. Cowley—were replaced by three new Apostles: George F. Richards, Orson F. Whitney, and David O. McKay. Merrill had passed away two months before in February, while Taylor and Cowley had both resigned from the Quorum of the Twelve a year earlier because of their involvement in post-Manifesto plural marriages.[46] Five years later, Taylor was excommunicated from the Church, and Cowley was disfellowshipped two months after Taylor’s excommunication.[47] Their replacements—Richards, Whitney, and McKay—were all monogamists and influential leaders later in the Church.[48]

Smoot went on to serve five more terms in the Senate until his eventual defeat in the Democratic wave of 1933, which was caused by the Great Depression. Along the way, he worked closely with presidents such as William Howard Taft, Calvin Coolidge, and Herbert Hoover. Was his service worth the sacrifice? Even though the Church had to deal with extremely negative press and address internal membership issues during the Smoot Hearings, Smoot’s affiliation with the Church provided valuable exposure. Jan Shipps, a Methodist historian, conducted a study on Smoot’s identification with the image of the Church and found that in the early period of Smoot’s service, his identification with the Church was almost overwhelming. During his first Senate term, 94 percent of the articles about Smoot mentioned his Church membership. While these numbers declined to around 20 percent in the 1920s, it is indisputable that Smoot’s senatorial tenure brought visibility to the Church and hastened its integration into the fabric of American culture.[49] “No person did more, during the first third of the twentieth century, to promote a positive image for the state of Utah than Reed Smoot,” one team of historians concluded. They continued, “Reed Smoot led Utah’s march into the national mainstream, both he and the state found rapid acceptance. This was a class moment in Utah history; the right personality and the right circumstance interacting to consummate a great change.”[50]

Even after the hearings ended, Smoot continued to be an ambassador for the Church. While his hesitance in his senatorial testimony may have caused some to question the sincerity of his connection to his faith, his actions throughout his time in Washington, DC, told a different story. The Smoot home became a hub of activity for Latter-day Saints in the DC area. Sacrament meetings were held biweekly in the Smoot home, with his family putting up enough folding chairs to accommodate the entire Latter-day Saint community in the area. When his senatorial duties allowed, Smoot was also diligent in carrying out his apostolic duties. A quick review of his journals lists his attendance at dozens of meetings and prayer circles in the Salt Lake Temple and with the First Presidency and Quorum of the Twelve.[51] When Smoot’s senatorial duties forced him to miss the April 1918 general conference, President Smith wrote to Smoot, “While you were missed, we all felt that the work you are engaged in was in the line of your duty and in harmony with this great work in which we are engaged.”[52]

Given the heavy weight of his senatorial duties, his record of Church service becomes even more outstanding. At times the two roles overlapped, providing Senator Smoot with opportunities to not only preach but demonstrate the power of his religion. On one occasion, President Warren G. Harding telephoned Smoot late at night. The first lady, Florence Harding, was very ill. President Harding recalled Smoot’s description of a priesthood blessing and asked the senator to come to the White House and perform the rite for his sick wife. Smoot immediately went to the executive mansion carrying a vial of consecrated oil and gave a priesthood blessing to Mrs. Harding.[53] This was only one of dozens of unique opportunities given to Senator Smoot because of his closeness to the leaders of the nation. During his time in Washington he worked with nearly every prominent politician of the age. Due to his prominence in the Republican Party, he was particularly close to presidents William Howard Taft, Warren G. Harding, Calvin Coolidge, and Herbert Hoover.

One historian commenting on Smoot’s record wrote, “There was little political glamor surrounding Reed Smoot. He was no orator. He shunned peccadilloes of his fellows; he staged no rebellions; he coined no phrases; he offered no intriguing new ideas. He merely worked without stint or respite and continued to win elections.”[54] Another major impact of Smoot’s lengthy senatorial career was borne out in the number of fellow Westerners he helped bring to the nation’s capital. Materials from one of his senate campaigns noted, “Not only has Senator Smoot become a household figure throughout the nation, but he has become successful in placing many Utahans in positions of national prominence where they, too, have brought honor and credit to the state of Utah.”[55]

But his primary benefit to the Church during his time in Washington, DC, came in his role of breaking down barriers of misunderstanding and prejudice toward the Saints. Though he was not the first Latter-day Saint to serve in Congress, Smoot’s trials opened the door for many of the Latter-day Saints who also served in the Senate, including William H. King (1917–41), and Elbert D. Thomas, who defeated Smoot in 1933 and then served until 1951. In the latter half of the twentieth century, the Senate included such notable Latter-day Saints as Frank Moss (1959–77), Jake Garn (1973–93), Paula Hawkins (1981–87), Harry Reid (1987–2017), and Orrin Hatch (1977–2019), to name only a sampling.[56] Recently the Washington Post has noted the unusually high number of Latter-day Saints in Congress, noting that Latter-day Saints “represent 1.6 percent of the country’s population, but the [Latter-day Saint] Church has long had a disproportionately large number of high profile leaders in Washington, both in Congress and in the federal government, which some attribute to the faith’s emphasis on public service. [Latter-day Saints] make up 6 percent of the Senate and 2 percent of the House.”[57] Every Latter-day Saint serving in government today is a part of the legacy of Senator Smoot.

When Smoot left the Senate in 1933, the Deseret News editorialized that he had “added more luster to the name of Utah than any man . . . since the days of its founder.”[58] A more personal tribute came from President Joseph F. Smith, who remained one of Smoot’s greatest advocates. Only a few months before President Smith’s death, he wrote to Senator Smoot, “I cannot understand how anyone, not even your bitterest opponents, can fail to see the handwriting of an overruling providence in the success and honor you have won and achieved at the seat of government. Surely the Lord has magnified his servant.”[59]

Notes

[1] Major sources for this study include the Reed Smoot Papers, found in the L. Tom Perry Special Collections of the Harold B. Lee Library at Brigham Young University, Utah. Smoot kept a detailed scrapbook of newspaper articles written about the controversy, which are found in boxes 111–12 of the Smoot Papers. Many of these articles are also found in the Journal History of the Church, available online. The most thorough treatment of Smoot’s life and accomplishments is found in Milton R. Merrill, Reed Smoot: Apostle in Politics (Logan: Utah State University Press, 1990). Studies of the Smoot hearings are numerous, but among the most useful is Kathleen Flake, The Politics of American Religious Identity: The Seating of Senator Reed Smoot, Mormon Apostle (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2004). Other significant studies include Harvard S. Heath, “The Reed Smoot Hearings: A Quest for Legitimacy,” Journal of Mormon History 33, no. 2 (2007): 1–80 and Konden R. Smith, “The Reed Smoot Hearings and the Theology of Politics: Perceiving an ‘American’ Identity,” Journal of Mormon History 35, no. 3 (2009): 118–62. To access the text of the hearings, see Michael Harold Paolos, ed., The Mormon Church on Trial: Transcripts of the Reed Smoot Hearings (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 2008). The diaries of Reed Smoot are available and have been published but unfortunately do not cover the period of the Smoot hearings. See Harvard S. Heath, ed., In the World: The Diaries of Reed Smoot, ed. (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1997).

[2] See James I. Mangum, “The Spanish-American and Philippine Wars,” in Nineteenth-Century Saints at War, ed. Robert C. Freeman (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2006), 151-92.

[3] Flake, The Politics of American Religious Identity, 5.

[4] Frank Cannon was one of the more colorful figures in Latter-day Saint political history. The eldest son of George Q. Cannon, he was elected as a Republican in 1896 as Utah’s first U.S. senator and served in the Senate from 1896 to 1899. He lost his reelection bid in part because of his determined support of free silver and a loss of institutional support from the Church. He later became head of the Utah Democratic Party and an ardent critic of the Church. At one point President Joseph F. Smith branded him a “furious Judas.” See Kenneth Godfrey, “Frank J. Cannon,” Utah History Encyclopedia, ed. Allen Kent Powell (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1994), 70. See also Richard S. Van Wagoner and Steven C. Walker, eds., A Book of Mormons (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1982), 44–48.

[5] Merrill, Reed Smoot, 31.

[6] Truman G. Madsen, Defender of the Faith: The B. H. Roberts Story (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1980), 261.

[7] See Davis Bitton, “The Exclusion of B. H. Roberts from Congress,” in The Ritualization of Mormon History and Other Essays (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1994), 150–70; Madsen, Defender of the Faith, 245. See also “The Manifesto and the End of Plural Marriage,” Gospel Topics Essay.

[8] Madsen, Defender of the Faith, 245–246.

[9] Charles W. Nibley, “Reminiscences of Charles W. Nibley,” MS, Church History Library, Salt Lake City; see Merrill, Reed Smoot, 25.

[10] “Smoot Charged with Polygamy,” Deseret News, 26 February 1903, copy in Smoot Newspaper Scrapbooks, Smoot Papers.

[11] “President Smith Makes Unqualified Denial; Smoot Is Not and Never Was a Polygamist,” Deseret News, 26 February 1903, Smoot Papers.

[12] Reed Smoot to John G. McQuarrie, 16 December 1902, Smoot Papers, box 27a; see Merrill, Reed Smoot, 31.

[13] “War on Senator Smoot,” New York Sun, 13 May 1901, Smoot Papers.

[14] “Smoot’s Toga is in Danger,” Pittsburgh Gazette, 15 May 1903, Smoot Papers.

[15] Harvard S. Heath, “Smoot Hearings,” in Encyclopedia of Mormonism, ed. Daniel H. Ludlow (New York: Macmillan, 1992), 3:1363.

[16] Reed Smoot to C. E. Loose, 26 January 1904, Smoot Papers, box 27a.

[17] Paolos, Mormon Church on Trial, 95.

[18] Paolos, Mormon Church on Trial, 51–52.

[19] Committee on Privileges and Elections, S. Rep. No. 486-1 at 129–31; see also Paolos, Mormon Church on Trial, 52–53.

[20] Merrill, Reed Smoot, 48.

[21] Flake, Politics of American Religious Identity, 69.

[22] Reed Smoot to James H. Anderson, 18 March 1904, Smoot Papers, box 27; cited in Heath, “Reed Smoot Hearings,” 29.

[23] Abraham H. Cannon, Diary, 7 October 1890 and 12 November 1891; see “Manifesto and the End of Plural Marriage,” 2019.

[24] “Manifesto and the End of Plural Marriage,” 2019.

[25] Joseph F. Smith, in Conference Report, April 1904, 75.

[26] “Manifesto and the End of Plural Marriage,” 2019.

[27] Paul B. Beers, Pennsylvania Politics Today and Yesterday: The Tolerable Accommodation (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1980), 51.

[28] “Hopkins Lauds Smoot,” Chicago Record Journal, 12 January 1907, Smoot Papers.

[29] Albert J. Hopkins, “The Case of Senator Smoot,” Independent 62 (24 January 1907): 207.

[30] “If There Should Be a House Cleaning in the Senate,” New York Press, 19 February 1905, Smoot Papers.

[31] “Mul’s Letter,” Citizen (Brooklyn), 8 March 1903, Smoot Papers. The author fails to mention the St. George, Logan, and Manti Temples as other places in Utah where those of other faiths were not allowed to enter.

[32] A. F. Phillips, “Smoot Must Answer Specific Questions for His Church or His Country,” Salt Lake Tribune, December 16, 1904, Smoot Papers.

[33] “Death Penalties in Mormon Oath,” Herald (New York), December 14, 1904, Smoot Papers.

[34] Express (Los Angeles), 20 December 1904, Smoot Papers; Enquirer (Oakland), 19 December 1904, Smoot Papers.

[35] Paolos, Mormon Church on Trial, 640–41n63; see Harvard S. Heath, “Reed Smoot: First Modern Mormon” (PhD diss., Brigham Young University, 1990), 174.

[36] Paolos, Mormon Church on Trial, 526–27.

[37] Paolos, Mormon Church on Trial, 526–27.

[38] “Morman Church Flayed; Smoot Report Goes In,” Baltimore Herald, 11 June 1906; spelling in original.

[39] “Remarkable Career of Reed Smoot,” Salt Lake Tribune, 18 December 1904, 7, Smoot Papers; spelling kept as shown in the original.

[40] Reed Smoot to Joseph F. Smith, 21 January 21, 1906, Smoot Papers, box 50, folder 5.

[41] “Hopkins Lauds Smoot,” Chicago Record Herald, 12 January 1907, Smoot Papers.

[42] Merrill, Reed Smoot, 80.

[43] Flake, Politics of American Religious Identity, 138.

[44] Albert J. Hopkins, “The Case of Senator Smoot,” Independent 62 ( 24 January, 1907): 204–6.

[45] See Brian C. Hales, Modern Polygamy and Mormon Fundamentalism: The Generations after the Manifesto (Salt Lake City: Greg Kofford Books, 2006), 102–4.

[46] The resignation letters of John W. Taylor and Matthias F. Cowley are both found in the Smoot Papers, box 50.

[47] Thomas G. Alexander, Mormonism in Transition (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1986), 70.

[48] Calling three new Apostles simultaneously would not happen again until over a century later, when in October 2015 Elders Ronald A. Rasband, Gary E. Stevenson, and Dale G. Renlund were called to fill the vacancies left by Boyd K. Packer, L. Tom Perry, and Richard G. Scott. “The Sustaining of Church Officers,” October 2015, churchofjesuschrist.org.

[49] Jan Shipps, “The Public Image of Reed Smoot, 1902–32,” Utah Historical Quarterly 45, no. 4 (Fall 1977): 382.

[50] “In This Issue,” Utah Historical Quarterly 45, no. 4 (Fall 1977): 324.

[51] See Heath, In the World.

[52] Joseph F. Smith to Reed Smoot, 7 May, 1918, cited in Merrill, Reed Smoot, 129.

[53] Merrill, Reed Smoot, 155.

[54] Milton R. Merrill, Reed Smoot: Utah Politician (Logan: Utah State Agricultural College Monograph Series, 1953), 5.

[55] Campaign document, What Has Senator Smoot Done for Utah? (Salt Lake City, Smoot Campaign, 1932), quoted in Merrill, Reed Smoot: Utah Politician, 53.

[56] Latter-day Saints who have served in the U.S. Senate and their terms of service include Reed Smoot (R-Utah, 1903–33), William H. King (R-Utah, 1917–41), Elbert Thomas (D-Utah, 1933–51), Berkeley L. Bunker (D-Nevada, 1940–42), Orrice Abraham Murdock (D-Utah, 1941–47), Arthur V. Watkins (R-Utah, 1947–59), Wallace F. Bennett (R-Utah, 1951–74), Howard W. Cannon (D-Nevada, 1959–83), Frank E. Moss (D-Utah, 1959–77), Edwin Jacob “Jake” Garn (R-Utah, 1974–93), Orrin G. Hatch (R-Utah, 1977–2019), Paula F. Hawkins (R-Florida, 1981–87), Harry M. Reid (D-Nevada, 1987–2017), Robert F. Bennett (R-Utah, 1993–2011), Gordon Smith (R-Oregon, 1997–2009), Michael Crapo (R-Idaho, 1998–present), Thomas S. Udall (D-New Mexico, 2008–present), Michael S. Lee (R-Utah, 2011–present), Jeffrey L. Flake (R-Arizona, 2013–19), Willard Mitt Romney (R-Utah, 2019–present). This list takes into account politicians who openly identified as Latter-day Saints when they served in the Senate. There are a number of senators such as Frank J. Cannon (R-Utah, 1896–99) and Kyrsten Sinema (D-Arizona, 2019–present) who came from Latter-day Saint backgrounds. See Robert R. King and Kay Atkinson King, “Mormons in Congress, 1851–2000,” Journal of Mormon History 26, no. 2 (Fall 2000): 11, 13. See also Manuel Roig-Franzia, “Congress’ First Openly Bisexual Member Grew Up Mormon, Graduated from BYU,” Standard Examiner, 3 January 2013; Jason Swensen, “U.S. Congress Includes 10 Latter-day Saints—the Fewest Number in a Decade,” Church News, 28 January 2019.

[57] Sarah Pulliam Bailey, “Romney Is Running for Senate. Even If He Wins, the Mormon Church Has Already Lost Powerful Status in D.C.,” Washington Post, 16 February 2018.

[58] Deseret News, 13 March 1933, quoted in Shipps, “Public Image of Reed Smoot,” 382.

[59] Joseph F. Smith to Reed Smoot, 5 January 1918, in Harvard S. Heath, “The Reed Smoot Hearings: A Quest for Legitimacy,” Journal of Mormon History 33, no. 2 (2007): 77.