Joseph Smith’s 1839–40 Visit to Washington

Byran B. Korth

Bryan B. Korth, “Images of Joseph Smith's 1839-40 Visit to Washington, DC,” in Latter-day Saints in Washington, DC: History, People, and Places, ed. Kenneth L. Alford, Lloyd D. Newell, and Alexander L. Baugh (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book), 1‒28.

Byran B. Korth was an associate professor of Church history and doctrine at Brigham Young University when this was published.

In the summer of 1839, Latter-day Saints began gathering in Commerce, Illinois, to regroup following their exile from Missouri. During the May and October conferences, they agreed to send a group of delegates to Washington, DC, “to importune the President and Congress of the United States for redress.”[1] With many members of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles serving missions, Joseph Smith Jr. (age thirty-four), Elias Higbee (age forty-four, a former Caldwell County, Missouri, judge), Sidney Rigdon (age forty-six, a counselor in the First Presidency), and Porter Rockwell (age twenty-five, Joseph’s friend and bodyguard) were called to take the cause of the Saints to Washington.

Sutcliffe Maudsley, Lt. General Joseph Smith, 1842. Church History Library.

Sutcliffe Maudsley, Lt. General Joseph Smith, 1842. Church History Library.

Much research has been done by historians and the Joseph Smith Papers Project regarding Joseph’s visit to Washington.[2] This essay contributes to this work by providing actual images of drawings, paintings, lithographs, and other artistic representations of the main locations at or near the time of his visit. A letter written upon their arrival by Elias Higbee to Hyrum Smith and the Nauvoo city council on 5 December 1839[3] will be a primary historical source for this chapter. By conducting historical and archival research with the Library of Congress to identify images pertaining to dates and locations referred to in Higbee’s letter, this chapter will focus on images that depict the overall layout of Washington and the National Mall in 1839–40 and the possible location of where Joseph and company boarded, as well as time-period images of the White House and Capitol Building that were central to their visit.

Historical Background of the Mission to Washington, DC

To appreciate the significance, purpose, and outcome of Joseph’s visit to Washington, DC, it is helpful to briefly highlight significant events of the suffering Saints leading up to the trip and to describe the circumstances that were demanding the attention of the government in the nation’s capital at that time. During 1838–39, the so-called Mormon War resulted in Saints being expelled from Missouri with an accompanying loss of life, land, and goods. From November 1838 to March 1839, Joseph and several other Church leaders were incarcerated in the Missouri cities of Independence, Richmond, and Liberty. By May 1839, many of the Saints had relocated to eastern Illinois and western Iowa. At Joseph’s direction, the struggling Saints gathered in the area of Commerce, Illinois, a bend in the Mississippi River that would later be named Nauvoo. Also during this time, the members of the Quorum of the Twelve were being called as missionaries to the British Isles.

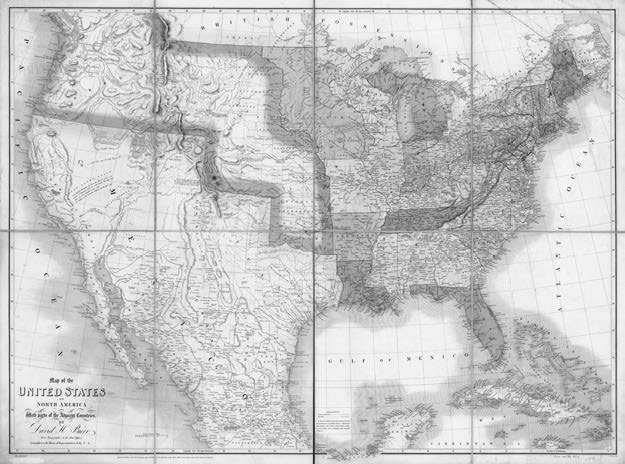

The nation’s capital was still in its infancy. In 1790, just fifty years before Joseph’s visit, the District of Columbia was created by an act of Congress to be “a meaningful expression of America’s new political and social order [giving] the country a governing structure symbolized in the location, construction, [and] design of government buildings.”[4] The city was very much a work in progress with about twenty-three thousand residents when Joseph arrived.[5] Figure 2 is a map of the United States around 1839.

Figure 2. John Arrowsmith and David H. Burr. Map of the United States of North America with Parts of the Adjacent Countries (London: John Arrowsmith, 1839). Library of Congress.

Figure 2. John Arrowsmith and David H. Burr. Map of the United States of North America with Parts of the Adjacent Countries (London: John Arrowsmith, 1839). Library of Congress.

The following are important events and government policies that were occupying the time and energy of the federal government in the United States during the late 1830s. “The weighty matters occupying America’s citizenry [during this time] subordinated the catastrophe consuming the Latter-day Saints in America’s westernmost state, Missouri.”[6]

- The president of the United States at the time of Joseph Smith’s visit was Martin Van Buren. He had succeeded Andrew Jackson in 1837 as the eighth president.

- The early Saints were not the only group who were dealing with the injustice of being forced from their homes and lands. In 1838, under the direction of the federal government, the Cherokee Indians were forced to leave their homes and land in Alabama, Georgia, North Carolina, and Tennessee and emigrate west to Indian Territory (modern-day Oklahoma).

- The United States and governmental officials were still dealing with the effects of the Panic of 1837, a financial crisis in the United States that touched off a major recession and lasted until the mid-1840s.

- As prelude to the Civil War (1861–65), the divisiveness of slavery could be felt and observed in the halls of Congress as early as the mid-1830s, with the first abolitionist elected to the House of Representatives in 1838.

Departure to and Arrival at Washington, DC

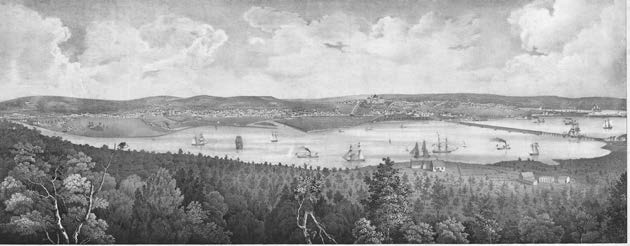

Figure 3. Philander Anderson and Fitz Henry Lane, View of the City of Washington, the Metropolis of the United States of America, Taken from Arlington House, the Residence of George Washington P. Custis Esq. (Boston: T. Moore’s Lithography, 1839). Library of Congress.

Figure 3. Philander Anderson and Fitz Henry Lane, View of the City of Washington, the Metropolis of the United States of America, Taken from Arlington House, the Residence of George Washington P. Custis Esq. (Boston: T. Moore’s Lithography, 1839). Library of Congress.

Joseph and the others departed from Commerce on 29 October 1839 (see table 1 on p. 25, which provides a list of significant dates and events regarding Joseph’s overall journey). In his history, Joseph wrote, “I left Nauvoo in a two horse carriage for the City of Washington to lay before the Congress of the United States, the grievances of the Saints in Missouri accompanied by Sidney Rigdon[7], Elias Higbee and Orin P. [Orrin Porter] Rockwell.”[8] As further evidence of the purpose and motivation to make this long journey in the late fall and winter to Washington, Joseph stated in a 9 November 1839 letter to his wife Emma, “But shall I see so many perish and <not> seek redress no I will try this once in the <name> of the Lord.”[9] Joseph and his companions arrived in Washington, DC, on 28 November 1839. The prophet stayed in the area for three weeks, primarily working with the Illinois delegation regarding his cause. Joseph then left to conduct a ministry tour in Pennsylvania and New Jersey, leaving Elias Higbee to continue seeking sympathy for the cause among members of Congress. Joseph returned to Washington for a time before returning to Nauvoo.[10]

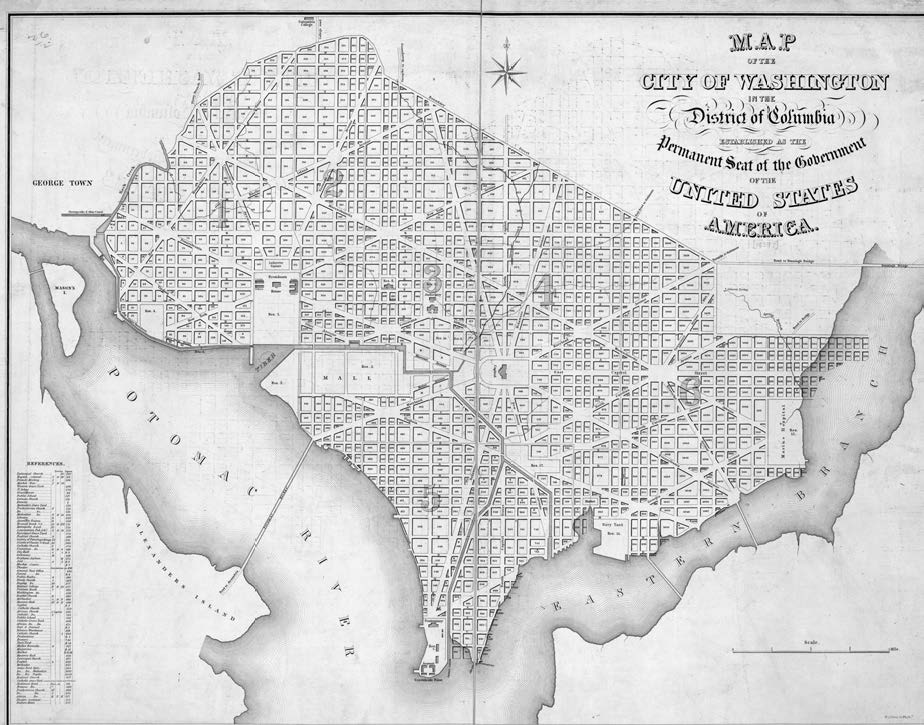

Figure 4. William James Stone, Map of the City of Washington in the District of Columbia: Established as the Permanent Seat of the Government of the United States of America (Washington?: n.p., 1839). Library of Congress.

Figure 4. William James Stone, Map of the City of Washington in the District of Columbia: Established as the Permanent Seat of the Government of the United States of America (Washington?: n.p., 1839). Library of Congress.

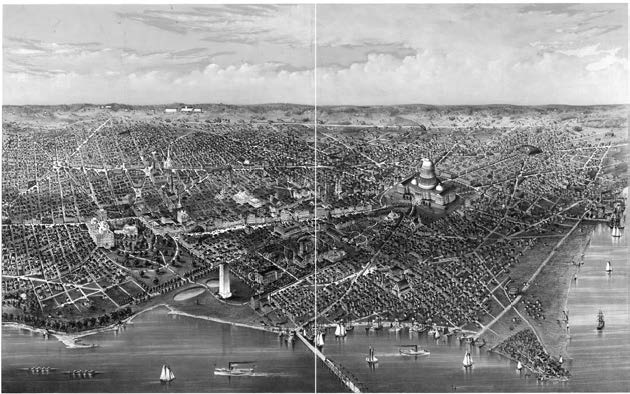

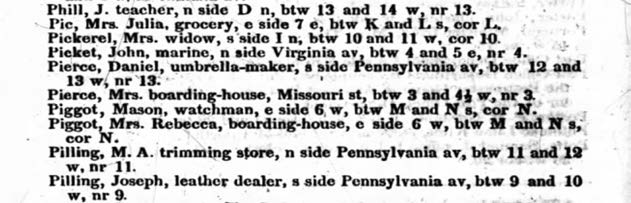

In his letter to Hyrum and the Nauvoo council, Higbee states, “We arrived in this City on the morning of the 28th of November.”[11] An 1838 artistic rendition of Washington from a distance provides a perspective of what Joseph might have seen as he drew near to the city on the other side of the Potomac River (see figure 3). [insert figure 3] This image emphasizes what Washington, DC, would have looked like to Joseph and company: a prominent city—with the monumental buildings of the White House and U.S. Capitol Building—that is still emerging from a largely country area.

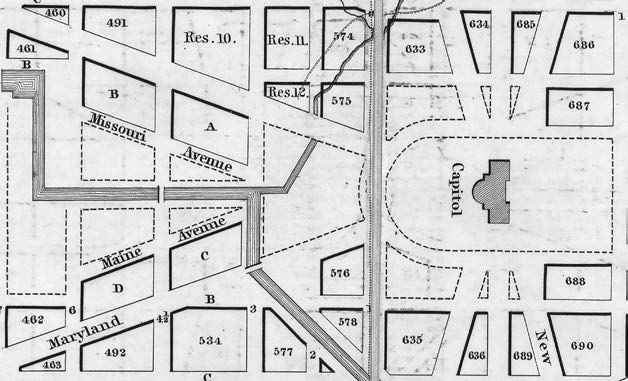

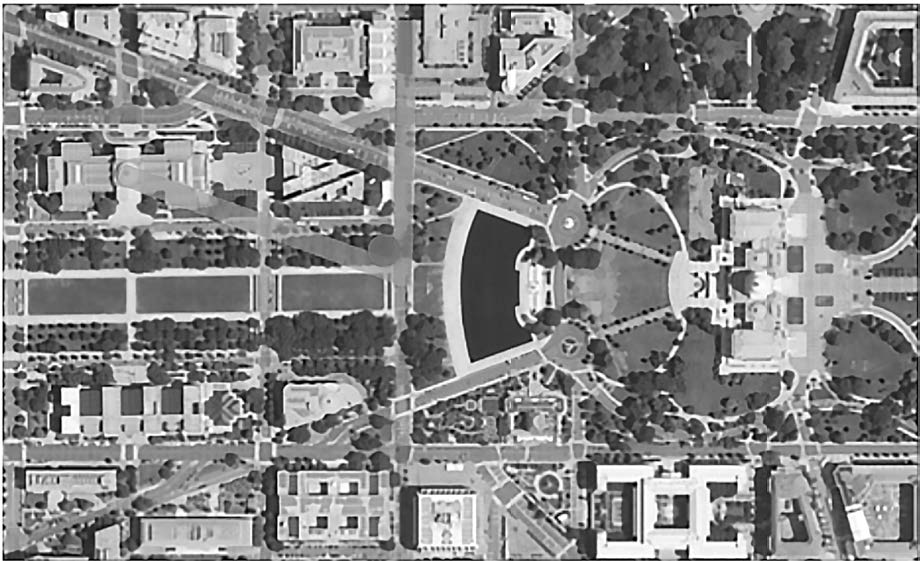

Figure 4 includes a circa 1839 map of the city of Washington, and figure 5 is a magnification of the 1839 map that overlays a current satellite image of the same location, focusing on the National Mall and various significant buildings. [insert figure 4] These figures further demonstrate how Washington, DC, would have been laid out in 1839 compared to today. The arrow line of figure 5 shows the approximate 1839 city border to the Potomac River, and the dotted line shows today’s border to the river. At the time of Joseph’s visit, the National Mall was a known location. The White House, U.S. Capitol Building, and Lockkeeper’s House were prominent buildings and locations of the time. Memorials that would not have existed during Joseph’s 1839 visit would have included the Washington Memorial (foundation stone laid in 1848 and completed in 1884), The Smithsonian Castle, the Lincoln Memorial, and the Jefferson Memorial (see large black squares in figure 5). In 1815 the Washington City Canal was built and was intended to be a grand avenue (shown by the striped line in figure 5. The entrance to the canal was managed by the Lockkeeper’s House, built in 1837, which regulated entry and traffic and collected tolls from those coming into the canal. It still stands today and is considered one of the oldest buildings on the National Mall. It is unknown where Joseph and his companions would have entered the city, but it is possible that they entered through the canal, passing the Lockkeeper’s House. The mudflats and marshland to the west of the 1839 National Mall were called the Potomac Flats for most of the 1800s. In 1870 the Army Corps of Engineers began dredging the Potomac to remove sediment and silt in order to deepen the canal’s ship channel so that Washington could be better accessed by water. Dredged material was dumped onto the tidal flats along the Washington waterfront. The work continued until 30 August 1911. After over forty years of dredging, more than twelve million cubic yards of material had been moved from the river to the waterfront, extending the National Mall to where the Lincoln Memorial (completed in 1922), the Jefferson Memorial (completed in 1943), and other national memorials and monuments stand today.

Figure 5. Overlay of 1839 map (see figure 4) and current satellite image of Washington, DC. Satellite image retrieved from maps.apple.com, 6 November 2019. Solid black circles indicate prominent locations that existed at the time of Joseph’s visit. Solid black squares indicate prominent locations that were built after Joseph’s visit. Striped line indicates the Washington City Canal. Arrow line indicates the approximate Washington, DC, border in 1839. Dotted line indicates the approximate border of modern-day Washington, DC.

Figure 5. Overlay of 1839 map (see figure 4) and current satellite image of Washington, DC. Satellite image retrieved from maps.apple.com, 6 November 2019. Solid black circles indicate prominent locations that existed at the time of Joseph’s visit. Solid black squares indicate prominent locations that were built after Joseph’s visit. Striped line indicates the Washington City Canal. Arrow line indicates the approximate Washington, DC, border in 1839. Dotted line indicates the approximate border of modern-day Washington, DC.

“Corner of Missouri & 3d Street”

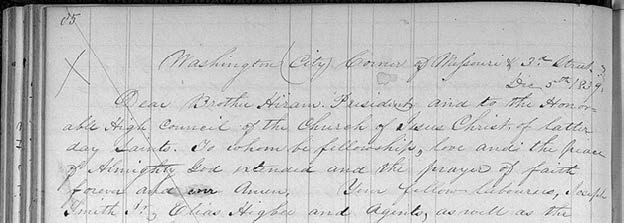

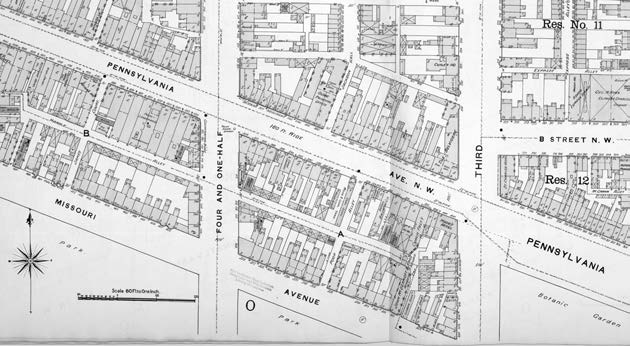

In Higbee’s 5 December 1839 letter, he states that upon their arrival to Washington, DC, they “spent the most of that day in looking up a boarding house which we succeeded in finding. We found as cheap boarding as can be had in this city.”[12] In the heading of his letter it indicates the location was “Washington City Corner of Missouri & 3d Street” (see figure 6).

Figure 6. Heading of Higbee Letter to Hyrum Smith, 5 December 1839. Joseph Smith and Elias Higbee, Letter, Washington, DC, to Hyrum Smith and Nauvoo High Council, Commerce, IL, 5 December 1839; in JS Letterbook 2, pp. 85–88; handwriting of Howard Coray; Church History Library

Magnifying the circa 1839 map of Washington in figure 4, we see the location of Missouri Avenue (gray diagonal) in relation to the Capitol Building and how Missouri Avenue parallels Pennsylvania Avenue (dashed diagonal) and intersects with Third Street (solid vertical line). This relationship of streets culminates with the “corner of Missouri & 3d Street” and is highlighted in red (see figure 7).

Figure 7. “Corner of Missouri & 3d Street” (indicated by star). Magnification of 1839 map (see figure 4). Striped line: Washington Canal; solid vertical line: 3rd Street; diagonal gray line: Missouri Avenue; diagonal dashed line: Pennsylvania Avenue.

Figure 7. “Corner of Missouri & 3d Street” (indicated by star). Magnification of 1839 map (see figure 4). Striped line: Washington Canal; solid vertical line: 3rd Street; diagonal gray line: Missouri Avenue; diagonal dashed line: Pennsylvania Avenue.

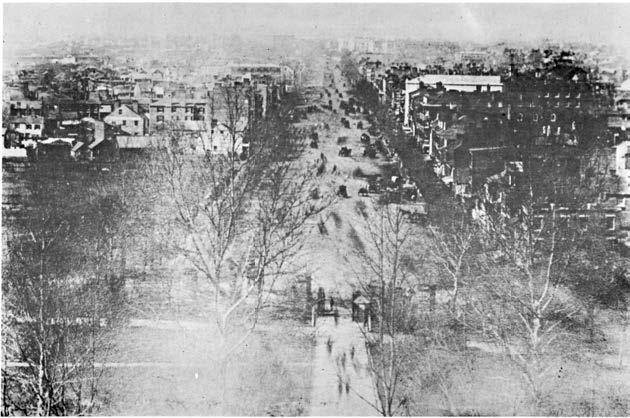

An 1843 city directory of Washington, DC,[13] describes Missouri Street as running “north of and near the canal, running from 3d to 6d street, west” (see Figure 7). It runs parallel with and is one block to the south of Pennsylvania Avenue, the main thoroughfare connecting the Capitol Building at First Street and the White House at Fifteenth Street. The National Park Service notes, “Much history transpired within the walls of private homes as well as in the hotels and boarding houses of the Pennsylvania Avenue district.”[14] According to city directories in the 1840s and 1850s and in line with other historical information about the avenue during this time period, Pennsylvania Avenue was a prime location for boardinghouses, hotels, restaurants, and entertainment. This was a place where government leaders and dignitaries resided while they conducted their public and political business at the Capitol Building and White House. Figure 8 is the earliest known photograph of Pennsylvania Avenue (1843) with boardinghouses and hotels in the foreground.[15]

Figure 8. 1843 image of Pennsylvania Avenue from Capitol Hill. Library of Congress.

Figure 8. 1843 image of Pennsylvania Avenue from Capitol Hill. Library of Congress.

There was a concentration of such establishments on Pennsylvania Avenue between Third and Sixth Street, given the close proximity to the Capitol Building. One such prominent hotel around in the 1830s and 1840s was The National, which was located on the corner of Sixth Street and Pennsylvania. Others prestigious hotels were located nearby, including The United States Hotel and The Indian Queen Hotel. Given the likely higher cost of boardinghouses and hotels on Pennsylvania Avenue, places which offered members of Congress easy access to the legislative halls, it is logical that Joseph and company desired to stay in the vicinity but found cheaper lodging on Missouri Avenue and off of the main artery (Pennsylvania Avenue) of Washington, DC.

Professor Kirk Savage has written extensively on public monuments within the larger theoretical context of collective memory and identity. In his book on the history of the Washington, DC, monuments, he explains the history of Missouri Avenue as follows:

A quasi memorial to Congress’s bargain with slavery emerged in the very center of the Mall near the Capitol. Completely unrecognized in histories of the city, this intervention in the landscape marked the outcome of the first of the grand bargains struck by Congress to solve the problems created by slavery’s expansion into new territories. The Compromise of 1820, or Missouri Compromise, admitted Maine as a free state and Missouri as a slave state, and prohibited slavery in the Louisiana Purchase everywhere north of the 36° 30¢ parallel, excepting Missouri. The memorial came in the form of two street names created after some Congressional wheeling and dealing to raise money for public works. Congress had authorized the city to sell off some of the public land at the east end of the Mall and create several large new residential blocks. The deal created two new diagonal avenues within the Mall, each one an inner spoke that shrank the boundaries of the Mall between Third and Sixth Streets. . . . In the 1820s the city council named the new avenues after the two new states that had been admitted to the Union by the 1820 Compromise: Missouri, the slave state, and Maine, the free state. For reasons unknown, the northern street was named Missouri and the southern street Maine. For more than a hundred years, this pair of radiating avenues framing the east entrance to the Mall marked the ultimately futile effort to contain the political crisis wrought by slavery.[16]

Figure 9. Today’s approximate location of the “Corner of Missouri & 3d Street” (indicated by star). Satellite image retrieved from maps.apple.com, 6 November 2019.

Figure 9. Today’s approximate location of the “Corner of Missouri & 3d Street” (indicated by star). Satellite image retrieved from maps.apple.com, 6 November 2019.

Given the history of the Saints, the purpose of Joseph’s visit, and the overarching politics of slavery, the irony of staying in a boardinghouse on Missouri Avenue cannot be left without acknowledgment. Although historical letters do not mention it, one can imagine Joseph and his companions conversing of this irony. Savage goes on to explain that “these diagonal streets and the resulting blocks of mostly residential buildings were all razed in the early 1930s.” The location of Missouri Avenue is now occupied by the National Gallery of Art on the National Mall (see figure 9).

Further historical and archival investigation reveals additional details of the possible area where Joseph and his companions stayed. An 1888 Sansborn Fire Insurance Map provides detail of the plat layout (see figure 10). Although created nearly fifty years later, the map gives an idea of how the residential area between Pennsylvania and Missouri Avenues looked with an alleyway between the two.

Figure 10. Sanborn Fire Insurance Map from Washington, District of Columbia (District of Columbia: Sanborn Map Company, 1888). Library of Congress. Corner of Missouri Avenue and Third Street indicated by star symbol.

Figure 10. Sanborn Fire Insurance Map from Washington, District of Columbia (District of Columbia: Sanborn Map Company, 1888). Library of Congress. Corner of Missouri Avenue and Third Street indicated by star symbol.

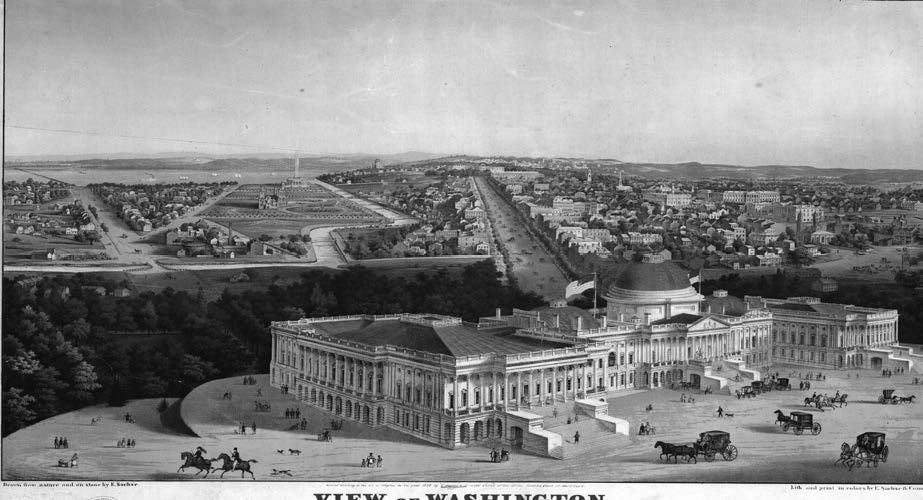

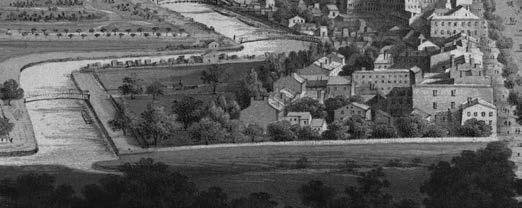

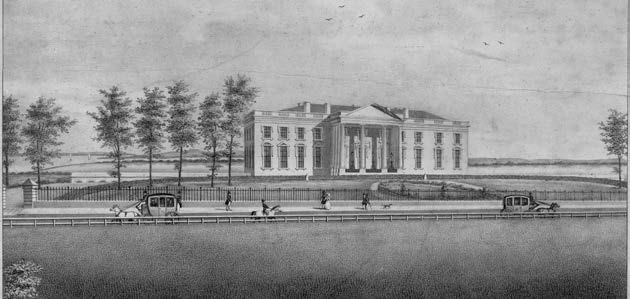

This layout is evident in earlier bird’s-eye view[17] renditions of Washington. In an 1880 bird’s-eye view from the Potomac looking north (see figure 11), we see additional detail depicted of this residential area west of the Capitol Building, including the corner of Missouri Avenue and Third Street (see figure 11 inset). An 1850s print showing a bird’s-eye view of the U.S. Capitol Building looking west gives additional insight into how the area may have looked closer to the time of 1839 (see figure 12). The most intriguing bird’s-eye artist rendition is a circa 1852 image looking west up Pennsylvania Avenue (see figure 13). Magnification of this image shows even more detail in relation to this residential area of Missouri Avenue (see inset of figure 13). Furthermore, an 1843 Washington Directory further indicates that the only boardinghouse listed in this area was “Mrs. Pierce, boarding-house, Missouri St, btw 3 and 4 and 1/

Figure 10. Sanborn Fire Insurance Map from Washington, District of Columbia (District of Columbia: Sanborn Map Company, 1888). Library of Congress. Corner of Missouri Avenue and Third Street indicated by star symbol.

Figure 10. Sanborn Fire Insurance Map from Washington, District of Columbia (District of Columbia: Sanborn Map Company, 1888). Library of Congress. Corner of Missouri Avenue and Third Street indicated by star symbol.

Figure 12. Robert Pearsall Smith. 1850 Bird’s-Eye View of the U.S. Capitol Building Looking West. View of Washington (ca. 1850). Library of Congress.

Figure 12. Robert Pearsall Smith. 1850 Bird’s-Eye View of the U.S. Capitol Building Looking West. View of Washington (ca. 1850). Library of Congress.

Figure 13. Edward Sachse. 1852 Bird’s-Eye View of Washington, DC, Looking West with the U.S. Capitol in the Foreground (Baltimore: E. Sachse & Co). Library of Congress. Inset: magnification showing the corner of Missouri Avenue and 3rd Street.

Figure 13. Edward Sachse. 1852 Bird’s-Eye View of Washington, DC, Looking West with the U.S. Capitol in the Foreground (Baltimore: E. Sachse & Co). Library of Congress. Inset: magnification showing the corner of Missouri Avenue and 3rd Street.

Figure 14. 1843 Washington Directory—“Pierce, Mrs. boarding-house.”

Figure 14. 1843 Washington Directory—“Pierce, Mrs. boarding-house.”

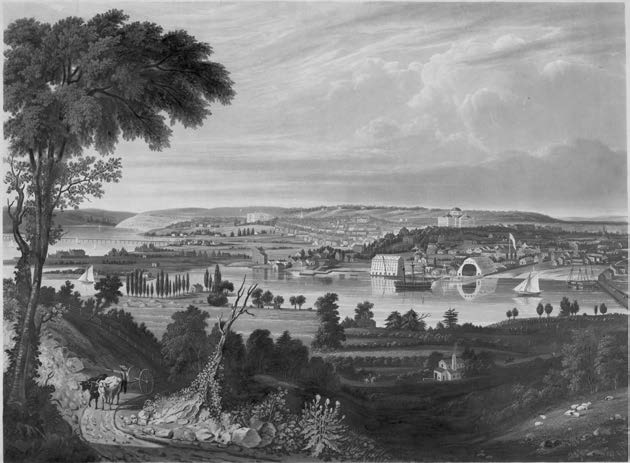

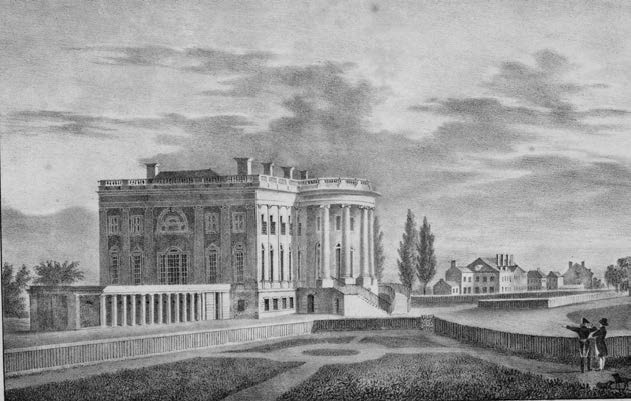

Visit to the White House

Higbee’s letter then indicates, “On Friday morning [November] 29th, [the day after they arrived] we proceeded <to> the house of the President—We found a very large and splendid palace, surrounded with a splendid enclosure decorated with all the fineries and elegancies of this world we went to the door and requested to see the President.”[19] Construction of the White House began in 1792, with John Adams being the first president to take residency there. Following a fire in 1814 (a result of the War of 1812), it was restored in 1817. North and south porticos were added in 1825 and 1829, with water and central heat being added in 1833 and 1837. Thus the White House was still new in its prominence when Joseph and Elias went to the door to see the president. A common image included in writings describing Joseph’s visit is an 1846 image showing the south side of the White House (see figure 15). However, paintings and drawings during the 1830s and 1840s give additional visual detail regarding the open landscape, proximity to waterways of the time, and accessibility to visitors and dignitaries because it was intended to be an impressive monument of the country. For example, figure 16 is an 1833 painting of Washington, DC, that looks northeast across the Anacostia River toward the Navy Yard with the Capitol Building in the center of the painting and the White House off to the left. Other etchings from the 1830s give additional perspectives (see figures 17–18).

Figure 15. John Plumbe, President’s House, ca. 1846. Library of Congress.

Figure 15. John Plumbe, President’s House, ca. 1846. Library of Congress.

Figure 16. W. J. Bennett and G. Cooke, View, probably 1833, from Anacostia, showing Navy Yard and Capitol in center, Arsenal and White House at left (New York: Lewis P. Clover). Library of Congress.

Figure 16. W. J. Bennett and G. Cooke, View, probably 1833, from Anacostia, showing Navy Yard and Capitol in center, Arsenal and White House at left (New York: Lewis P. Clover). Library of Congress.

Figure 17. 1830s view of White House. Library of Congress.

Figure 17. 1830s view of White House. Library of Congress.

Figure 18. 1830s north view of the President’s House with Potomac River directly behind. Library of Congress.

Figure 18. 1830s north view of the President’s House with Potomac River directly behind. Library of Congress.

The visit to the White House and the meeting with President Van Buren was discouraging, given the description by Elias Higbee in his 5 December letter. He first describes Van Buren as follows: “He is a small man, sandy complexion, and ordinary features; with frowning brow and considerable body but not well proportioned, as his arms and legs—and to use his own words is quite fat— . . . and in fine to come directly to the point, he so much a fop or a fool, (for he judged our cause before he knew it,) we could find no place to put truth into him.”[20] Common images of the president show him as an older man (see figure 19). Another image from an 1839 print possibly reflects how Van Buren looked at the time of Joseph and Elias’s meeting with him when he was fifty-seven (see figure 20). Of their visit, Higbee states, “We presented him with our Letters of introductions;—as soon as he had read one of them, he looked upon us with a kind of half frown and said, what can I do? I can do nothing for you,—if I do any thing, I shall come in contact with the whole State of Missouri—But we were not to be intimidated, and demanded a hearing and constitutional rights—Before we left him he promised to reconsider what he had said.”[21]

Figure 19. President Martin Van Buren, half-length portrait (photographed between 1840 and 1862). Library of Congress.

Figure 19. President Martin Van Buren, half-length portrait (photographed between 1840 and 1862). Library of Congress.

Figure 20. Charles Fenderich and Peter S. Duval. Martin Van Buren, President of the United States (Philadelphia: P. S. Duval, 1839). Library of Congress.

Figure 20. Charles Fenderich and Peter S. Duval. Martin Van Buren, President of the United States (Philadelphia: P. S. Duval, 1839). Library of Congress.

The U.S. Capitol Building

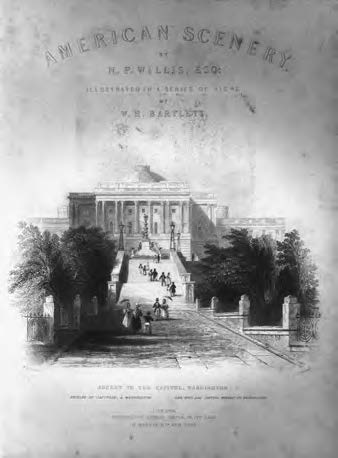

Figure 21. W. H. Bartlett, View of the Capitol at Washington. Nathaniel P. Willis, American Scenery, vol. 1 (London: Virtue, 1840), frontispiece. Library of Congress.

Figure 21. W. H. Bartlett, View of the Capitol at Washington. Nathaniel P. Willis, American Scenery, vol. 1 (London: Virtue, 1840), frontispiece. Library of Congress.

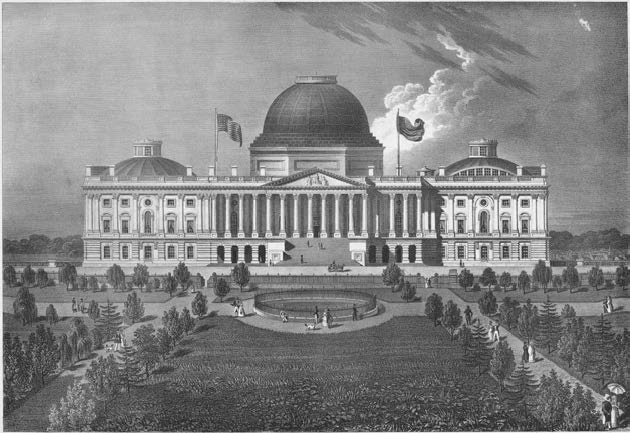

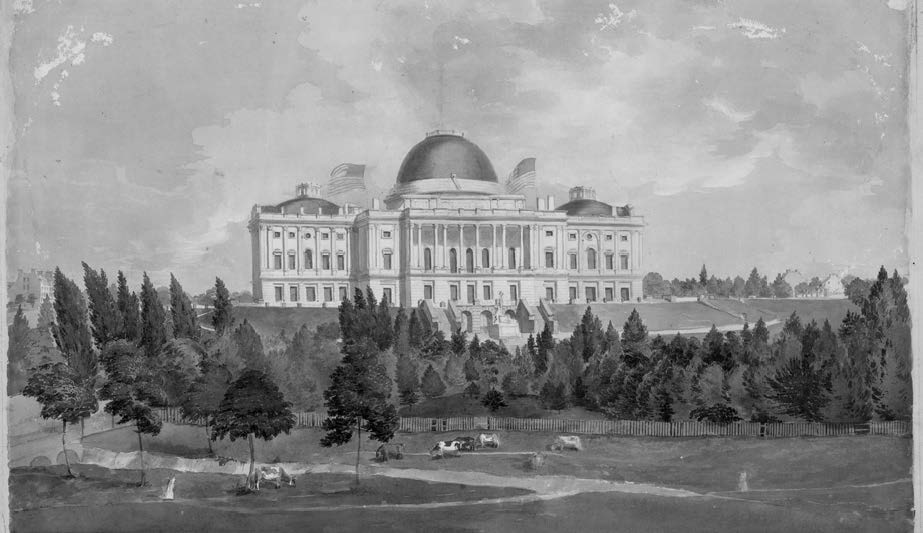

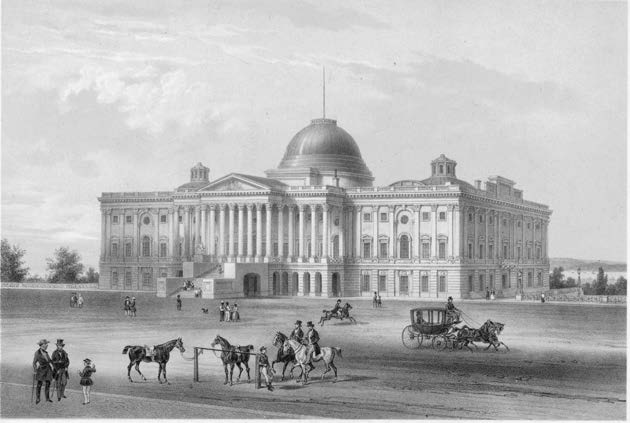

With the first congressional sessions being held in 1800, the Capitol Building quickly became a familiar icon throughout America. Numerous printings were included in travel accounts beginning in the 1810s, depicting an architecturally magnificent building that represented the vital and ambitious institutions it housed (see figures 21–23).[22] Architecture and construction were an intentional conveyance of political structure and social order, a symbol of power. Joseph and company likely had seen these images prior to their 1838 visit and anticipated viewing the building and were hopeful in participating in what it stood for.

Figure 22. Bandbox with Wallpaper View of the Capitol, ca. 1840. From J. and D. Louv, Mizzentop Farm Antiques. Library of Congress.

Figure 22. Bandbox with Wallpaper View of the Capitol, ca. 1840. From J. and D. Louv, Mizzentop Farm Antiques. Library of Congress.

As Joseph and the group approached Washington, DC, on the day of their arrival, they would have noticed the prominence of the U.S. Capitol Building both from a distance and up close. As they spent that first day searching for boarding just west of the Capitol, the building would have been impressive as they prepared to speak with government officials in the halls of Congress. An online exhibition by the Library of Congress titled “Temple of Liberty: Building a Capitol for a New Nation,” explains that the Capitol Building was meant to be a symbol, a symbol that Joseph may have interpreted as a hope for the liberty of his people. Artistic renditions from the 1830s and 1840s often captured the more popular west-side view from Pennsylvania Avenue showing “the newly planted trees that covered the grounds and provided a dark base upon which the white building seemed to float”[23] (see figures 24–25). Joseph and company would have spent much time here pleading their case in the hall and rooms of the Capitol,[24] portrayed as the “center and heart of America” (see figures 26–27).

Figure 23. William A. Pratt and Charles Fenderich, Elevation of the Eastern Front of the Capitol of the United States (Philadelphia: P. S. Duval, 1839). Library of Congress.

Figure 23. William A. Pratt and Charles Fenderich, Elevation of the Eastern Front of the Capitol of the United States (Philadelphia: P. S. Duval, 1839). Library of Congress.

Figure 24. John Rubens Smith, West Front of the Capitol with Cows in the Foreground (Washington, DC, ca. 1831). Library of Congress.

Figure 24. John Rubens Smith, West Front of the Capitol with Cows in the Foreground (Washington, DC, ca. 1831). Library of Congress.

Figure 25. West view of the Capitol from Pennsylvania. Alfred Jones, Capitol of the United States at Washington (New York: Burton, ca. 1846–1855). Library of Congress.

Figure 25. West view of the Capitol from Pennsylvania. Alfred Jones, Capitol of the United States at Washington (New York: Burton, ca. 1846–1855). Library of Congress.

Figure 26. Robert Brandard and W. H. Bartlett. Principal Front of the Capitol, Washington (Washington, DC, 1839). Library of Congress.

Figure 26. Robert Brandard and W. H. Bartlett. Principal Front of the Capitol, Washington (Washington, DC, 1839). Library of Congress.

Figure 27. August KÖllner. Washington—Capitol East View (New York & Paris: Goupil, Vibert & Co., 1848). Library of Congress.

Figure 27. August KÖllner. Washington—Capitol East View (New York & Paris: Goupil, Vibert & Co., 1848). Library of Congress.

Impact of the Washington, DC, Mission on Joseph and the City of Nauvoo

By providing actual images of paintings, sketches, lithographs, and other artistic representations of the main locations at or near the time of Joseph’s visit, this essay has enhanced our ability to visualize Joseph’s historic visit to Washington, DC, to seek redress for the suffering Saints. At the same time, it also opens up other possible connections and outcomes of his visit.

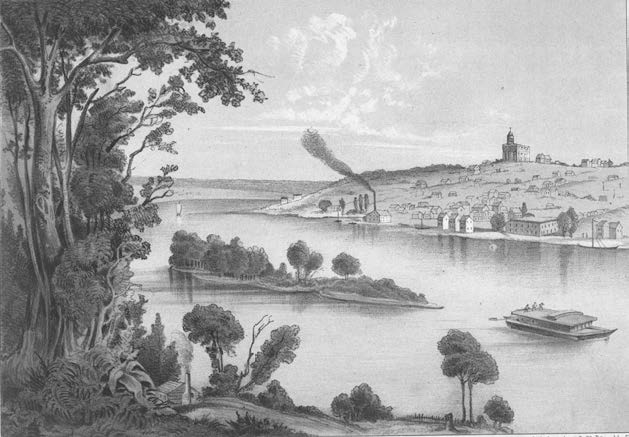

Figure 28. Nauvoo, Illinois (ca. 1855). Library of Congress.

Figure 28. Nauvoo, Illinois (ca. 1855). Library of Congress.

First, it is likely that the experiences of this trip planted and nurtured a seed for Joseph and the Saints to get involved in government and politics, including a presidential campaign. In response to his own presidential campaign, Joseph stated, “If I ever get in the presedental [presidential] chair— I will protect the people in their rights & libe[r]ties.”[25] On another occasion Joseph declared, “As to politics I care but little about the Presidential Chair, I would not give half as much for the office as I would for the one I now hold, but as the world have used the power of Government to oppress & persecute us, it is right for us to use it for the protection of our rights. when I got hold of the eastern paper & see how popular I am I am afraid myself that I shall be elected, But if I should be, I would not say that your cause is just & I could not do any thing for you.”[26] These statements allude to the response Joseph received from President Van Buren in response to Joseph’s plea for justice: “What can I do? I can do nothing for you,— if I do any thing, I shall come in contact with the whole State of Missouri.”[27]

Figure 29. Henry Lewis, Nauvoe, Illinois (1854). New York Public Library.

Figure 29. Henry Lewis, Nauvoe, Illinois (1854). New York Public Library.

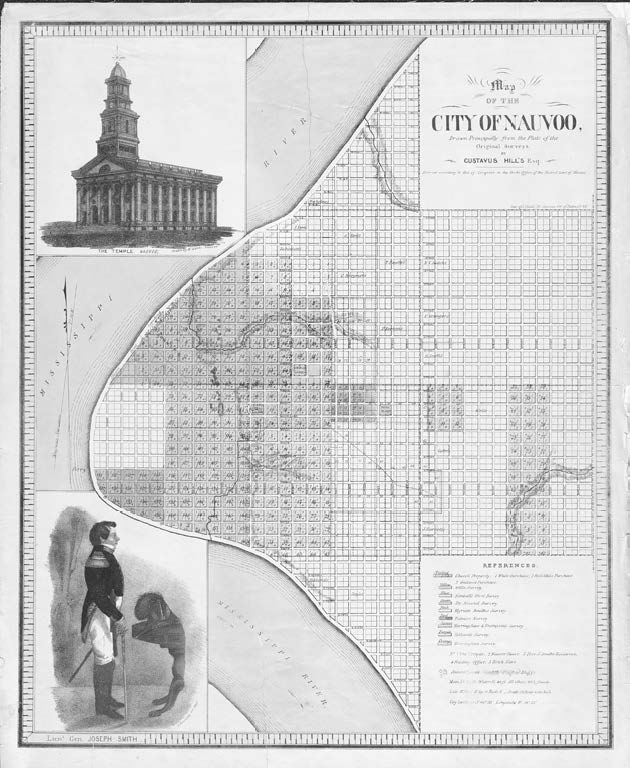

Second, given the purposeful visual expression of America’s governing structure symbolized in the location and design of the buildings and monuments of Washington, DC, a question that deserves further study is whether this experience influenced Joseph in his design and layout of the city of Nauvoo—namely, his purposeful placement and location of the city’s buildings. This includes the Nauvoo House as a place to welcome and host guests (similar to the purpose of the White House) and the location of the temple on the top of the hill where it could be seen from a distance by visitors as a symbol of the religious government that had been restored (similar to the symbolic placement of the Capitol Building). Joseph had prior experience in city planning with Kirtland. However, by comparing the consistent and unique patterns used in Kirtland and Nauvoo, it may be possible to identify the parallels between what Joseph saw in Washington and what he wanted to visually incorporate in the building of Nauvoo. Figures 28–30 support this possible connection.

Figure 30. Map of Nauvoo with profile of Joseph Smith (Lithograph, John Childs, 1844, from a plat by Gustavus Hills, 1842; inset of temple by William Weeks, 1842; inset of Joseph Smith by Sutcliffe Maudsley, 1842). Church History Library.

Figure 30. Map of Nauvoo with profile of Joseph Smith (Lithograph, John Childs, 1844, from a plat by Gustavus Hills, 1842; inset of temple by William Weeks, 1842; inset of Joseph Smith by Sutcliffe Maudsley, 1842). Church History Library.

Conclusion

After more than three months, Joseph’s party decided to end their mission to Washington, DC, and turn their attention to building their own monumental city, Nauvoo. In a letter to Joseph, Elias shared, “I feel now, as though that we have made our last appeal to all earthly tribunals; that we should now put our whole trust in the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob— We have a right now which we could not heretofore so fully claim— That is of asking God for redress and redemption; as they have been refused us by man.”[28] Disappointed and discouraged with the country that claimed to protect the freedoms for all, and despite the hope they had had in their government to provide justice for what had happened in Missouri, Elias’s letter shows the determination of Joseph and the Saints to once again put their reliance and trust in God.

Table 1. Significant dates and events regarding Joseph Smith’s visit to Washington, DC

Date | Event |

| May & October 1839 | Conferences appoint delegates to go to Washington, DC. |

| 29 October 1839 | Delegates depart Commerce, Illinois (in a carriage). |

| 8 November 1839 | In Springfield, Missouri, a physician joins group to care for Sidney Rigdon, who is suffering from malaria. |

| 18 November 1839 | Stop in Columbus, Ohio, to allow Sidney some relief. Group continues without Sidney. |

| 28 November 1839 | Arrive at Washington, DC, and spend the day looking for boarding. |

| 29 November 1839 | Visit White House and President Martin Van Buren. |

| End of November and early December 1839 | Meet with state representatives to prepare to bring case to the House of Representatives. |

| January 1840 | Joseph visits Saints in Pennsylvania and New Jersey while Elias remains in Washington, DC. |

| January-March 1840 | Case is made to government. |

| March 1840 | Joseph arrives back in Nauvoo. Elias concludes efforts in Washington, DC, and also returns to Nauvoo. |

| 7 April 1840 | Joseph reports at the general conference. |

Notes

[1] “History, 1838–1856, volume C-1 [2 November 1838–31 July 1842],” 972, The Joseph Smith Papers (website).

[2] See the following sources: Ronald O. Barney, “Joseph Smith Goes to Washington,” in Joseph Smith, the Prophet and Seer, ed. Richard Neitzel Holzapfel and Kent P. Jackson (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2010), 391–420; R. Scott Lloyd, “Joseph Smith’s Unsuccessful Visit to White House for Redress Still Inspiring, Editor Says,” Church News, 1 May 2018; Saints, vol. 1, Standard of Truth, 1815–1846 (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints), chap. 34; for letters and accounts, see The Joseph Smith Papers.

[3] “Letter to Hyrum Smith and Nauvoo, Illinois, High Council, 5 December 1839,” 85, The Joseph Smith Papers.

[4] “Temple of Liberty: Building the Capitol for a New Nation,” Exhibitions, Library of Congress (website).

[5] “1840 United States Census,” Wikipedia.

[6] Barney, “Joseph Smith Goes to Washington,” 391–420.

[7] Before their departure, Sidney was suffering from malaria. His condition worsened during the first part of the journey and thus was unable to continue with Joseph and company. See Barney, “Joseph Smith Goes to Washington,” 391–420.

[8] “History, 1838–1856, volume C-1 [2 November 1838–31 July 1842],” 972.

[9] “Letter to Emma Smith, 9 November 1839,” 1, The Joseph Smith Papers.

[10] Barney, “Joseph Smith Goes to Washington,” 391–420.

[11] “Letter to Hyrum Smith and Nauvoo, Illinois, High Council, 5 December 1839,” 85.

[12] “Letter to Hyrum Smith and Nauvoo, Illinois, High Council, 5 December 1839,” 85.

[13] “1843 Washington City Directory, A–K” DCGenWeb Project.

[14] National Park Service, The Pennsylvania Avenue District in the United States History: A Report on the National Significance of Pennsylvania Avenue and Historically Related Environs, Washington, D.C. (1965), 41.

[15] National Park Service, “Pennsylvania Avenue District,” 41.

[16] Kirk Savage, Monument Wars: Washington, D.C., the National Mall, and the Transformation of the Memorial Landscape (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011), 46–48.

[17] Between the mid-1800s and the early 1900s, panoramic or bird’s-eye-view maps of cities and towns captured the imagination of Americans because air flight was uncommon. These perspective drawings gave the view of a popular location from both ground level and high elevations.

[18] National Park Service, “Pennsylvania Avenue District,” 41.

[19] “Letter to Hyrum Smith and Nauvoo, Illinois, High Council, 5 December 1839,” 85.

[20] “Letter to Hyrum Smith and Nauvoo, Illinois, High Council, 5 December 1839,” 85–86.

[21] “Letter to Hyrum Smith and Nauvoo, Illinois, High Council, 5 December 1839,” 85.

[22] “Temple of Liberty: Building the Capitol for a New Nation.”

[23] “Temple of Liberty: Building the Capitol for a New Nation.”

[24] See Elias Higbee letters dated 5 December; 20, 21, 22, 26 February; 9, 24 March, josephsmithpapers.org.

[25] “Journal, December 1842–June 1844; Book 3, 15 July 1843–29 February 1844,” 248, The Joseph Smith Papers.

[26] “Discourse, 7 March 1844–B, as Reported by Wilford Woodruff,” 203, The Joseph Smith Papers.

[27] “Letter to Hyrum Smith and Nauvoo, Illinois, High Council, 5 December 1839,” 85.

[28] “History, 1838–1856, volume C-1 [2 November 1838–31 July 1842],” 1022, The Joseph Smith Papers.