Hot Shoppes, Hotels, and Influence: The Marriotts in Washington

Dale Van Atta

Dale Van Atta, “Hot Shoppes, Hotels, and Influence: The Marriotts in Washington,” in Latter-day Saints in Washington, DC: History, People, and Places, ed. Kenneth L. Alford, Lloyd D. Newell, and Alexander L. Baugh (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book), 261‒82.

Dale Van Atta is a New York Times best-selling author and journalist who coauthored the world’s most widely syndicated news column with Jack Anderson.[1]

The J.W. and Alice Marriott family, ca. 1950. All photos in this chapter courtesy of Deseret Book. © Marriott International.

The J.W. and Alice Marriott family, ca. 1950. All photos in this chapter courtesy of Deseret Book. © Marriott International.

John Willard Marriott, the son of a sheepherder, stepped off a train in Washington’s Union Station on his twenty-first birthday, 17 September 1921.[1] Fresh from his Latter-day Saint mission to New England, J.W. was dressed in a new tailor-made suit—a splurge of $47.50 for the near-penniless missionary. His parents wanted him home to work their farm north of Ogden, Utah, but first J.W.[2] wanted to see his nation’s capital. He never expected to return to the East Coast, so this would likely be his only opportunity.[3]

J.W. hopped on a tour bus that took him past the White House, Arlington Cemetery, and the monuments and the homes of some of Washington’s notables, including Utah’s controversial Senator Reed Smoot.[4] The senator had received a cold welcome in Washington in 1903 because of the polygamist heritage of his home state. Although his own monogamist marriage had been well established, Smoot was still the butt of local humor. The tour bus guide brought laughter when he pointed out that the senator’s house had only one entrance because “he can only have one wife here.”[5]

J.W. had no inkling at the time that he would someday make his home in Washington, DC, that he would found a restaurant and hotel empire there, or that his future mother-in-law would one day marry the widowed Senator Smoot—nor that he and his two sons would be able to use their prominent position in the nation’s capital to significantly advance the cause of the Lord’s restored church, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

While in Washington as a recently released missionary, J.W. spent an afternoon with Utah congressman Don Colton, whose son Hugh was one of J.W.’s best friends and a previous mission companion. Despite the buzz of the capital and the distinguished company, the one sight that remained in J.W.’s mind as he boarded the train for Utah was the hardworking street vendor selling ice cream, lemonade, and sodas to the sweltering tourists. If a man wanted to go into the food and beverage business, he thought, this would be the place to do it.[6]

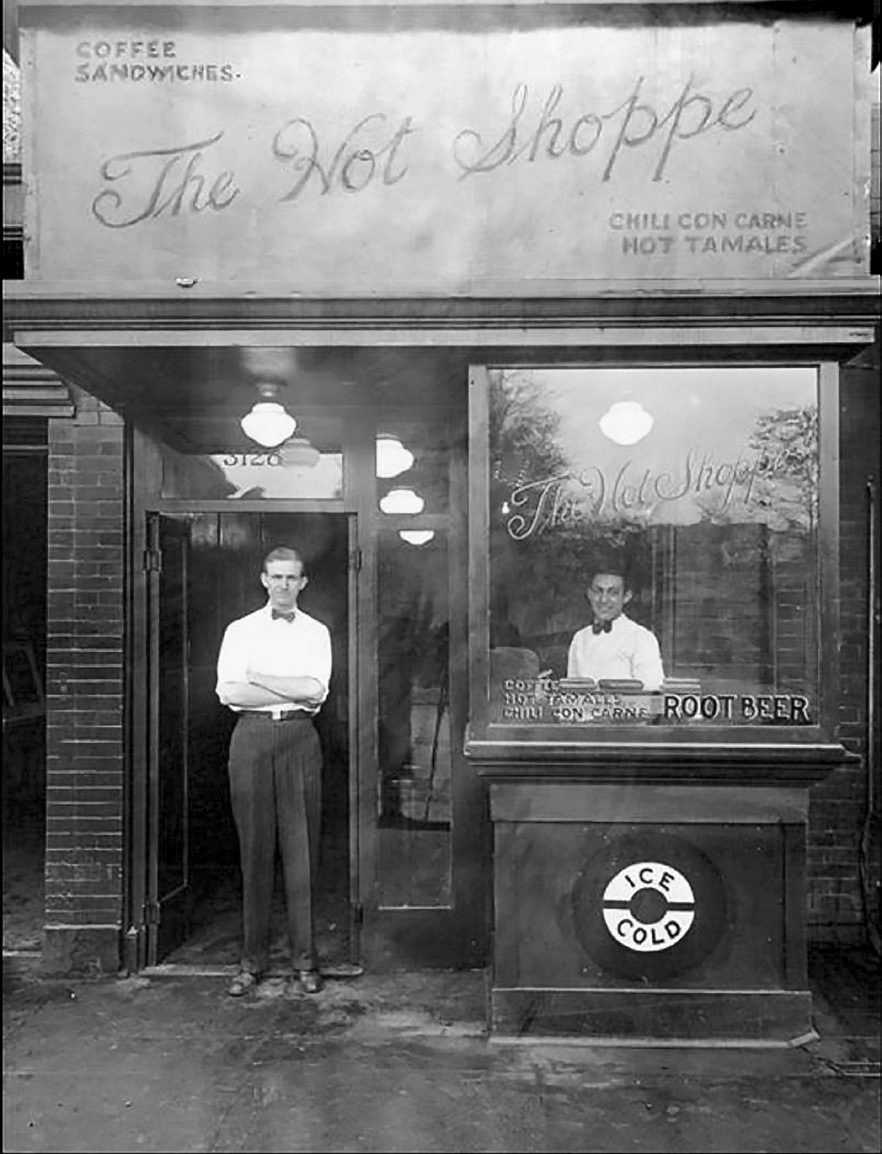

Six years later, in the spring of 1927, J.W. left his family’s farm behind and settled in Washington with his new wife, Alice (Allie) Sheets, his new business partner Hugh Colton, and a franchise agreement to build the first A&W Root Beer stand on the East Coast. J.W. and Colton’s first tiny storefront operation opened downtown on Fourteenth Street, the same day that Charles Lindbergh took off for his solo flight across the Atlantic. J.W. rushed out that morning to buy a portable radio so customers would be lured into the shop to listen to news of Lindy’s progress. Many years later when J.W. and Allie shared a dinner table at the White House with Lindbergh, J.W. joked, “You know, we went into business on the same day, but you got all the publicity!”[7]

The Hot Shoppe, 1927. J.W. is standing in the door.

The Hot Shoppe, 1927. J.W. is standing in the door.

Colton soon sold his share in the franchise and returned to Utah, leaving J.W. and Allie to turn the pop stand into a food operation. Allie collected recipes from her own Western upbringing and visited the Mexican Embassy to borrow ideas for Tex-Mex dishes. The popularity of the menu spread, and people began asking when they would open another “hot shop.” The title stuck, and the couple rebranded from a root beer stand to sit-down restaurants they called Hot Shoppes, which were soon popping up all over Washington. The Hot Shoppe on Georgia Avenue was the first drive-in restaurant east of the Rocky Mountains.[8]

As the first waves of the Great Depression were felt across the country, the Marriotts forged ahead with their Hot Shoppes chain. They opened their fifth restaurant on Connecticut Avenue on 2 July 1930, the same day Allie’s widowed mother, Alice Sheets, married widower, Apostle, and senator Reed Smoot. The couple had met at church when Alice visited Washington, and their courtship was chronicled in the Washington newspapers. They planned to honeymoon in Hawaii, but President Herbert Hoover prevailed upon Senator Smoot to stay in town for an important vote. As consolation, Hoover invited the newlyweds to honeymoon for two weeks at the White House.[9]

J.W. and Allie Marriott in DC.

J.W. and Allie Marriott in DC.

Two years later, Smoot lost his reelection bid for a sixth term. He asked the Marriotts to move into his French provincial mansion on Garfield Street as caretakers (later buyers) so the Smoots could go back to Utah. J.W. and Allie moved in, along with their first child, John Willard Marriott Jr., born in 1932. He was called Billy, and later Bill.

The Marriotts found their community of friends in the small Latter-day Saint branch, filled mostly with government workers drawn from Utah by Senator Smoot. One of their Sunday School teachers was the brilliant lawyer J. Reuben Clark Jr., undersecretary of state in the Coolidge administration and later an apostle. Another was the Church’s most legendary FBI agent, Sam Cowley. It was Cowley who headed up the team that finally brought down America’s “Public Enemy #1,” John Dillinger, in July 1934. Four months later in a rural Illinois farm field, Cowley faced down George “Baby Face” Nelson in a submachine-gun battle, which ended in both their deaths.[10]

Washington D.C. Branch meetings at the time were held in an upstairs room of the Washington Auditorium at New York Avenue and E Street. In 1924, with help from Senator Smoot, the Church purchased land in the Embassy District on Sixteenth Street and Columbia Road, and construction began on a chapel. The Marriotts donated twenty-five hundred dollars to the building fund—a considerable sum at the time—and the chapel was dedicated by President Heber J. Grant in 1933 with more than a thousand people attending three separate dedication services.[11]

The dedication was a high point for the Marriotts in a year that brought troubling news. J.W. was diagnosed with Hodgkin’s lymphoma—a conclusion confirmed by five doctors—and was told he had a year to live. Resigned to the news, the Marriotts took a long vacation along the East Coast. While visiting his former mission sites, it occurred to J.W. that the illness might be a test of his faith—a test that he was failing by giving up. Back in Washington, he called Edgar Brossard, a member of the U.S. Tariff Commission, and federal judge Gustave Iverson, both Church elders. They came to his house and gave him a priesthood blessing: “As elders of the church, we promise you in the name of the Lord that you will be healed. We rebuke this disease. We believe, and we ask you to believe with us, in your mission of service to your fellow man and to your church, and we promise that you will live to perform this mission.” In a few weeks, J.W.’s symptoms were gone, thus ensuring the subsequent birth of his second son Richard (Dick) in 1939 and the future conversion from a restaurant to a hotel empire by his first son, Bill.[12]

Dick, J.W., and Bill in the office, ca. 1965.

Dick, J.W., and Bill in the office, ca. 1965.

In the 1930s and 1940s, the Washington community of Latter-day Saints was relatively small, so it was a natural thing that the Marriotts became very close with, among others, Ezra Taft Benson, before and after he was an Apostle and secretary of agriculture for President Dwight D. Eisenhower[13]; Mervyn Bennion, the captain of the USS West Virginia who went down with his ship in Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941, becoming one of that war’s first Medal of Honor winners[14]; Russell M. Nelson, who came to DC as a young lieutenant and doctor at Walter Reed Army Medical Center (1951–53);[15] and George Romney, president of American Motors, future presidential candidate, and governor of Michigan, who considered J.W. his closest friend[16]—so close, in fact, that he named his second son Willard Mitt, who would be known by his middle name.

Even though the Marriotts’ wealth, connections, and reputation grew on the East Coast, when Bill went to the University of Utah as a freshman in the early 1950s, the Marriott name was still relatively unknown in the West. Donna Garff returned from a dinner date with Bill to meet his parents for the first time, and her sorority sisters filled her in. “Don’t you know that they have a lot of money with all these Hot Shoppes back East?” they buzzed. “I didn’t know anything about it, nor did I care,” Donna recalled. “I just thought they [J.W. and Allie] were wonderful, down-to-earth people.”[17]

After graduation, Bill joined the U.S. Navy—a brief career that J.W. tried to manage with his Washington connections. J.W. wanted Bill stationed in the capital, close to home. But Bill refused all special treatment and instead did a tour on the USS Randolph aircraft carrier. By telephone, he proposed to Donna and invited her to spend December of 1954 with him and his family at the Marriott getaway—Fairfield Farm in Hume, Virginia. Elder Benson had invited another guest, President Eisenhower, to come to the farm at the same time for bird hunting.

Donna was now starstruck by her future in-laws, and Bill, the navy ensign, was stunned to be in the company of his commander-in-chief. When the temperatures outside dropped below freezing, the hosts asked Eisenhower if he still wanted to go hunting. The president turned to Ensign Marriott and said, “What do you think we should do?” Bill remembered the moment as an early lesson in leadership. “I was just the lowest form of life in the navy, and he was asking me what I wanted to do.”

Bill recovered his composure and said, “I think we should stay inside by the fire.” The president replied with his big signature grin. “I think your suggestion is great. Let’s do that.” The guests settled down for dinner, followed by a “typical Latter‑day Saint family home evening” led by Elder Benson, his wife Flora, and their children.[18]

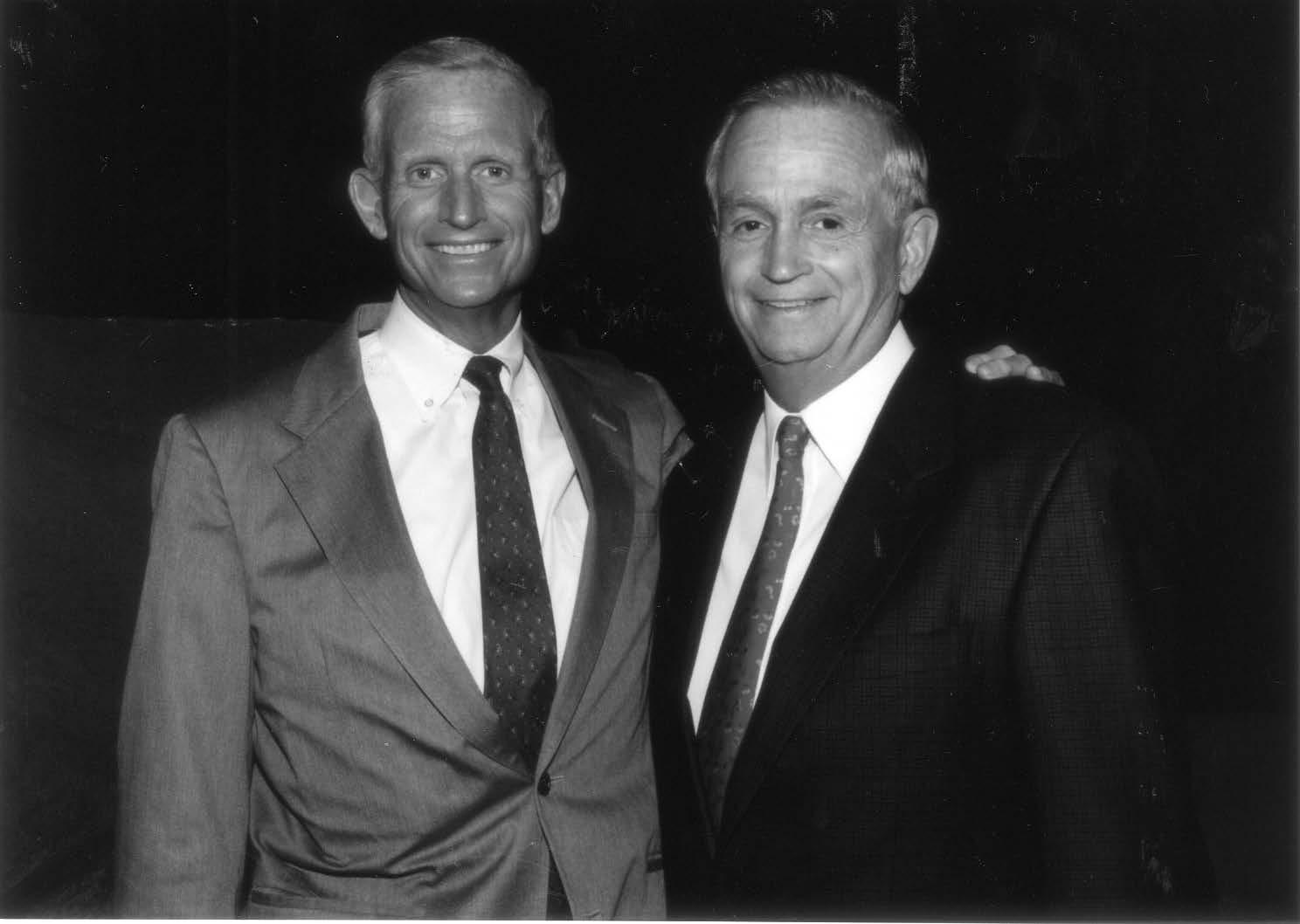

Dick and Bill Marriott at Camelback for Bill’s birthday party, 1997.

Dick and Bill Marriott at Camelback for Bill’s birthday party, 1997.

Bill married Donna in the Salt Lake Temple in 1954, finished his obligation to the navy, and returned home to Washington, DC, to join the family restaurant business, which he quickly expanded by adding hotels. J.W. took some time to get on board with the idea, but when he did, he wanted to build grand lodgings—a hybrid between elegant downtown hotels of the day and mom-and-pop motor hotels that were the common suburban and highway fare. The first was the Twin Bridges Marriott on the Virginia side of the Fourteenth Street Bridge leading into Washington. Bill quickly proved proficient at running hotels. The Twin Bridges Marriott was a pioneer of many upscale motor-hotel features including room service, a reservation system, meeting rooms, ballrooms, restaurants, and a swimming pool that doubled as an ice skating rink in the winter. Special guests one Christmas Eve included Elder Benson, who took a fall on the ice and dislocated his shoulder.[19]

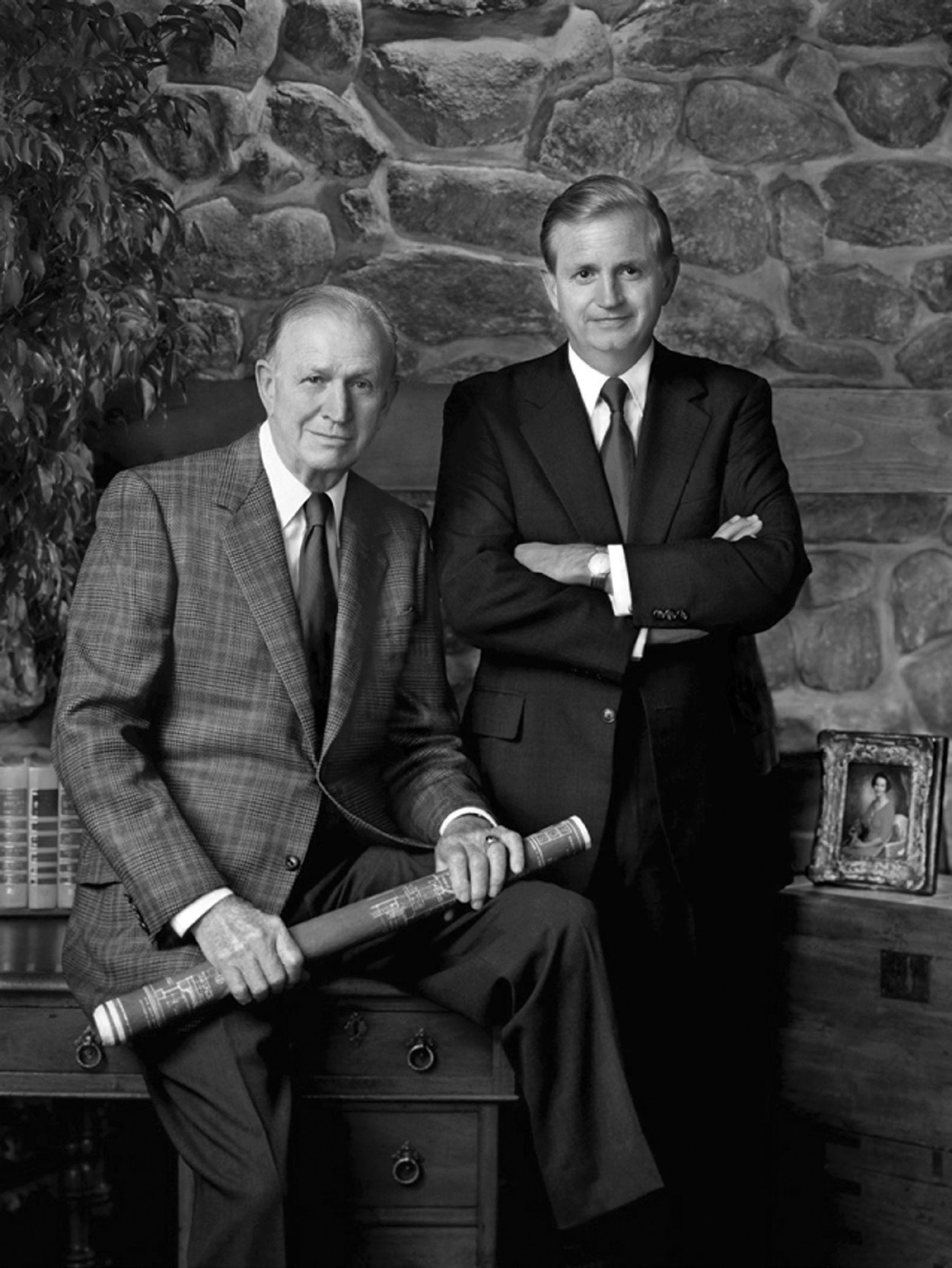

J.W. and Bill Marriott

J.W. and Bill Marriott

Uncertain about the long-term viability of the Hot Shoppes chain, Bill grew the hotel division, moving on to the Key Bridge Marriott in the DC suburb of Rosslyn, Virginia. The third Marriott—and the first outside of Washington, DC—was in Dallas. The first outside the United States was in Acapulco, Mexico. Eventually the company expanded into airline catering, industrial cafeterias, theme parks, cruise lines, fast food restaurant chains, fine-dining restaurants, full‑service vacation resorts, and senior living facilities. The number of hotels grew from the hundreds to thousands as Marriott acquired other chains and applied its brand to existing hotels around the world.

Bill eschewed political entanglements, but his parents were drawn to them. Allie served as the first female treasurer of the Republican National Convention in 1964 and held the job again in 1968 and 1972. She rose to become vice chair of the Republican National Committee during the Nixon administration.[20] In 1966 J.W. joined the campaign advisory staff for George Romney’s run for president until the stress of that highly charged campaign triggered a near-fatal heart attack for J.W. in 1967.[21]

Richard Nixon won that 1968 election and asked J.W. to chair the inaugural events. Allie and J.W. sat behind the Nixons at the inauguration and then led the inaugural parade to the White House in a convertible, with the Mormon Tabernacle Choir not far behind—an important appearance J.W. had arranged. Four years later, J.W. reluctantly chaired Nixon’s second inaugural events in 1973. J.W. arranged for a thirty‑member contingent from the Tabernacle Choir to perform at the White House church service before the inauguration. The choir brought the distinguished members of the audience to their feet with a rendition of the “Battle Hymn of the Republic.”[22]

The balance of business and church was a demanding side of life for the Marriott family. But J.W. never forgot (and often passed along) the words his mother, Ellen, often said to her children: “I’d rather have a stone tied around your necks and have you cast into the ocean than to have you forget your religion and not live it every day of your lives.” When J.W. had to make business decisions that involved his religious tenets, he was not shy about picking up the phone and calling an apostle or even a prophet for advice. In 1961 a prime opportunity arose to build a Marriott hotel in Philadelphia. The company’s first three hotels had been in Virginia and Texas—both dry states that prohibited alcohol sales in hotels. But Pennsylvania was a wet state. Bill hired a consulting firm to give the bottom line on potential profits from the Philadelphia hotel; liquor sales in the restaurants would be key to the success of the venture, the consultants advised.[23] “Having a real struggle to expand and hold market without liquor. Must put in hotels. Will get a lot of criticism. I hate it,” J.W. wrote in his journal.[24] He continued to agonize over the decision until he finally visited with President David O. McKay, who turned out to be surprisingly pragmatic.

“I will ask you as one brother to another,” the eighty-seven-year-old prophet began, “suppose a sheepman, like you were, goes into a grocery store owned by a Mormon to buy supplies, and he wants cigarettes for his [non-LDS] men. If the storekeeper says, ‘Sorry, we don’t carry tobacco in any form because it’s against our religion,’ why, the customer won’t come back the next time. If he wants coffee for his men and the storekeeper says, ‘We disapprove of it, and we don’t want your men to drink it either,’ he won’t come back again. He’ll go to the store down the street not only for his tobacco and coffee, but for everything else he needs. In the long run, this could put the storekeeper out of business, don’t you agree?” J.W. agreed, and President McKay continued. “As I see it, Brother Marriott, if you don’t satisfy your customers’ wants and needs, you could be running the same risk. If liquor today is an essential part of the service that the hotel and restaurant industry offers to its patrons, it seems to me that you’re obliged to sell it to them. To sell it to them doesn’t mean that we approve of drinking, any more than to sell a gun means approval of using that gun to commit a crime. The patron who believes as we do is not compelled to buy liquor, nor, indeed, is anyone. But it is the patron’s life, his money, his right to decide for himself, not ours.”[25]

President McKay ended with a caution to J.W. against serving liquor in most of his other enterprises—particularly the family-oriented Hot Shoppes or any company eateries where children were regular customers. J.W. went back to Washington, DC, with a decision to allow liquor sales in his upscale hotel restaurants and lounges.

Gambling in Marriott hotels was a different matter. Bill and J.W. briefly considered a contract to manage a Las Vegas hotel-casino in 1972, but both were troubled by the moral and ethical repercussions, which at the time occasionally involved perks such as prostitutes and drugs for high rollers. Bill and J.W. passed on the deal.[26] In 1976, Bill toyed with the idea of buying part of the Del Webb Company. He wanted only the lodging portion of the company, excluding their four Nevada hotel-casinos. When rumors circulated that Marriott wanted all the Del Webb assets, Bill got a call from Church President Spencer W. Kimball. “I can’t tell you how to run your business,” the prophet carefully said, “but I would like to strongly suggest that you not get into gambling, that you not go into Las Vegas.” He recounted his own sad experience with friends from his hometown in Arizona who had lost their meager fortunes to the lure of what some called “Sin City.” Bill didn’t need much convincing, and when he took the issue to the Marriott board, the board members agreed that gambling could tarnish the image of the company.[27]

The Marriotts’ prominence and busy, globe‑trotting schedules did not exempt them from serving in the trenches of the Church. When Benson became the first Washington D.C. Stake president in 1940, he called J.W. to serve on the high council. Eight years later, in 1948, J.W. himself was called as stake president. Near the end of his nine-year service, on 30 October 1957, during a breakfast with Elder Harold B. Lee, J.W. was shocked to learn that the First Presidency wanted to consider him as a potential General Authority—most likely as an apostle. According to J.W.’s journal, Lee said “there was no one outside the council as close to the brethren as I am. I should get my affairs in order as Chairman of (Marriott Corporation) Board so I could get away & take a church job (in Salt Lake City). This was quite a shock especially to Allie who feels we are now destined to a life-time job in the church.” J.W. respectfully sent word back to President McKay that he felt he was of better use and influence for the Church in Washington, and the prophet agreed.[28]

Three years before his release, J.W. officially launched (with a letter) an intense lobbying campaign to persuade the First Presidency to authorize construction of a temple in the nation’s capital, the first one east of the Mississippi River since the Nauvoo Temple burned down nearly a century before. Marriott and two others—prominent Latter-day Saint lawyer Robert Barker and successor stake president Milan Smith—were ultimately the local triumvirate most responsible for the acquisition of the site in 1962 and the subsequent 1968 decision to build the temple. But they would never have succeeded without the untiring advocacy of President Hugh B. Brown, first counselor in David O. McKay’s First Presidency.[29]

J.W. Marriott’s seventy-eighth birthday. Left to right: Bill, Donna, J.W., Allie, Nancy, and Dick Marriott.

J.W. Marriott’s seventy-eighth birthday. Left to right: Bill, Donna, J.W., Allie, Nancy, and Dick Marriott.

When Bill was called to the Washington D.C. Stake’s high council in 1974, his first assignment was to decide what to do with the aging Latter‑day Saint chapel on Sixteenth Street—once a showplace with a statue of the angel Moroni on top of it. By the 1970s, however, it was a structural liability whose iconic status was now moot given the near-completion of the monumental temple in Kensington, Maryland. The following summer, in 1975, to everyone’s surprise, Bill was called to be bishop of the Chevy Chase Ward. J.W. responded by doing something almost unheard of in the Church—he phoned President Kimball and asked him to cancel the calling because Bill was too busy running Marriott Corporation. The prophet responded, “This calling was approved by our First Presidency and we’re not going to reverse it.”

Bill’s acceptance of the call may have been his greatest act of faith. He was CEO of a $732-million company in the middle of a recession, and now he had another full-time “job” overseeing a large congregation. Bill coped by managing his ward as he did his business, but with a liberal dose of compassionate care. He scoured the ward to personally seek out the less-active members. He presided over worship services, weddings, funerals, social events, and—perhaps the most challenging—ward campouts. He dreaded camping, and he would outfit his station wagon with a mattress to avoid having to sleep in a tent. When a Hispanic congregation in the stake was disbanded, he absorbed the members into his largely Anglo and affluent Chevy Chase Ward, creating a translation booth and distributing headphones to Spanish speakers so they could participate in worship services. He was often one of the last to leave the church building after an activity and could be found doing dishes and mopping floors in the church kitchen.

Donna summed up her husband’s life during that period: “First there were church meetings, and then he’d stay after church to counsel with people in his church office. After that, he’d make hospital visits or go to the members’ homes to talk with them. Then he’d go to work Monday morning just wrung out. People couldn’t understand why he was so tired on Monday. They’d all been out playing golf.”

Bill was bishop for just two years before he was called as first counselor in the Washington D.C. Stake presidency, serving for five years. Then, in 1982, he was called to be the eighth president of the Washington D.C. Stake, a position he held for eight years during a period of the most unprecedented expansion of his hotel empire. Twice a year he flew to Salt Lake City to attend general conference. One year he formed a new friendship with a stake president from Germany, Dieter Uchtdorf, who would later become an apostle. Bill had met Uchtdorf first on business when Uchtdorf was chief pilot and senior vice president of Lufthansa Airlines, with responsibilities over airline catering, which was one Marriott sideline. Even before the two became friends, Uchtdorf strategically dropped Bill’s name into curious or potentially hostile conversations in European business meetings about the Church. Once Uchtdorf mentioned Bill was a Mormon, conversations with associates about the Church turned positive. “He represented what the church stood for in a perfect, humble way, so there was never a risk of embarrassment using Bill as the example of Mormon values,” Uchtdorf said.[30]

Dick, Allie, and Bill at the annual meeting following J.W.’s death, 1986.

Dick, Allie, and Bill at the annual meeting following J.W.’s death, 1986.

As stake president, Bill presided over the funeral of his father, who died in 1985. J.W.’s funeral was the closest thing to a state funeral ever hosted at a Latter-day Saint chapel, with speakers including not only apostles such as Ezra Taft Benson, Gordon B. Hinckley, and Boyd K. Packer but also former President Richard Nixon and the world’s foremost Christian evangelist, the Reverend Billy Graham. The Washington Post devoted an editorial to the local hero’s passing, casting it as the end of an era: “Pardon us for taking a slightly parochial view of J. Willard Marriott when we point out that with him died another bit of small-town Washington. A community’s merchants give it much of its character. And the quality of its individual businesses reflects the quality of those who are responsible for them. [The city’s] warm recollection of the Hot Shoppes institution is a tribute to Marriott. For many years, his little chain of restaurants helped give this capital something of the flavor of a courteous, pleasant, overgrown village before he became a towering business figure and the city also went on to bigger things.”[31]

After the funeral, the Marriott family went to their Lake Winnipesaukee vacation homes in New Hampshire along with Elder Packer, who was to dedicate the small Latter-day Saint chapel in nearby Wolfeboro that Sunday. On Saturday morning, Bill was alone refueling his boat to give Elder Packer a ride on the lake, when a gas leak exploded into flames and engulfed him. Bill plunged into the lake, and his family dragged him to the beach. At the hospital, Elder Packer gave Bill a priesthood blessing, promising there would be no long-term repercussions from the severe burns that covered most of his body. He spent sixteen days in a hospital burn unit and endured months of skin-graft surgeries and rehabilitation, returning to work five months later. All the while, he retained his calling as stake president.

At the same time, he and his only sibling—younger brother Dick—had been depended upon by church leadership for not-so-well-known service. For example, serving under Elder Marvin J. Ashton, Bill became a key member of the board of the Polynesian Cultural Center in Laie, Hawaii, for eleven years (1977–88). Elder Dallin H. Oaks subsequently asked Dick to join the PCC board. Dick served eighteen years (1995–2013) in the voluntary position, the last four as chair.

Three decades after Bill was bishop, Dick was called—at age sixty-six—to the same position by then stake president Nolan Archibald, longtime CEO of Black & Decker. “I admire Nolan for doing it,” recounted Elder Jeffrey R. Holland. “It probably would have been easy not to do it, to be fearful that ‘you’re just calling a Marriott again.’ But what a tragedy it would have been for the Saints not to have had a bishop like Dick, and what a marvelous blessing it was for him. For six years, he was devoted to a fare-thee-well—an exemplary bishop.”[32] President Russell M. Nelson agreed: “Can you imagine being called as the bishop at age sixty-six? I had nothing to do with that, of course. That was President Archibald. Bishop Marriott was faithful to every responsibility he had as bishop, even though it meant he had to give up a lot of his traveling. He never sloughed his responsibilities as a bishop.”[33]

In part because the capital is home to more than 140 foreign embassies and international organizations, both Bill and Dick and their wives, Donna and Nancy, respectively, have been influential ambassadors for the Church for decades. President Nelson attributed a number of international goodwill successes for the Church to Bill, particularly in Eastern Europe before and after the Berlin Wall fell in 1989. “The Marriott name carried so much weight with these people,” Elder Nelson said in a 2013 interview.[34] “They were doing cartwheels to get Marriott hotels in their countries, so when Bill hosted an activity, lending his good name and his great faith to the Lord’s work, they came and they listened.” President Nelson has specifically singled out Bill’s assistance in making entrée for the Church in the Soviet Union (and now Russia), Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, the former Yugoslavia, and Poland, where the pioneering Warsaw Marriott (completed in 1989) was the safe meeting place for the Warsaw Saints.[35]

“It is always a joy to be able to accomplish something of unusual worth for the Church—and you have opened important doors, making it possible for us to walk through in the best possible light,” seconded Beverly Campbell in a letter to Bill.[36] Campbell was the first director (1985–97) of the Church’s key international affairs office in Washington, followed by directors Ann Santini (1997–2016) and Mauri Earl (2016–present). All three have gratefully engaged the Marriotts to host their primary international outreach events—the Christmas holiday Festival of Lights; the Western Family Picnic at the Marriott Ranch in Hume, Virginia; and the annual luncheon for the wives of diplomats, which Donna Marriott hosted at least fifteen times (between 1994 and 2014) in her home, occasionally featuring a private tour of Bill’s extensive antique auto collection.[37]

Because ambassadors could bring their wives and children to experience an unforgettable piece of Americana at the annual fall picnic in the beautiful Virginia hills at the Marriott Ranch, the Western Family Picnic has been particularly popular among diplomats since 1991, when Dick and Nancy Marriott first began hosting the event. Barbecue, Native American dancers (from Brigham Young University), a short talk by a visiting General Authority, and various areas set up for western crafts and displays are often featured. “It was a lot of fun with a lot of things they could do there,” recalled Santini. It’s a “beautiful place” their families can enjoy, and “to meet Dick and Nancy Marriott is a big deal.”[38]

The Festival of Lights began in December 1978, and dozens of diplomats are invited each year for the opening night when the dazzling display of four hundred thousand lights in the trees illuminates the Washington D.C. Temple grounds.[39] Bill has cohosted the popular Christmas event since it began, helping to select an ambassador to be honored each year. “Believe me, it has made a difference that Bill Marriott is at the top of the invitation and opens the program for us,” said Santini.[40]

When Bill travels abroad to open a hotel, he routinely invites the area’s mission president to be introduced to the country’s leaders. Elder D. Todd Christofferson never forgot what a difference it made for Mexican government-Church relations when Bill introduced him to President Ernesto Zedillo at the opening of a Mexico City Marriott. “I don’t know how Bill knew Zedillo—he seems to know everybody in the world—but he was just so up front about the Church. Bill was not in the least reticent or embarrassed in any way about his membership and bringing it to the forefront.” Elder Christofferson credited the introduction with helping to smooth over some visa issues regarding Latter-day Saint missionaries in Mexico. “I always appreciated Bill was upfront about the Church, and would so energetically use his influence on behalf of the Church.”[41]

For many years, Latter-day Saint missionaries were banned from Thailand after an infamous photo of a missionary sitting on a Buddha was circulated. When Bill opened the JW Marriott in Bangkok in 1994 and was granted an audience with the king, he saw a chance to strengthen Church relations in the country. Son-in-law Ron Harrison was on hand for the visit. “He brought the mission president to that meeting, and it was a big deal. In the meeting, the king mentioned the incident from decades before, but became friendly in discussing future relations. . . . This is the kind of bridge building that Bill Marriott can do because he has these kinds of avenues to government leaders which enhance and accentuate the cause of building Zion.”[42]

Finally, there is the placement of more than a million copies of the Book of Mormon in individual Marriott Hotel rooms around the world that has occurred for more than a half century—a major missionary effort by the Marriott family. Even though Marriott International owns few hotels—being primarily a hotel-management company—Bill mandates in a signed agreement that every owner will place a Book of Mormon in every hotel room, though the owners do not have to pay for them. The Marriott family foundation, headed by Dick Marriott since 1988, covers the cost of distribution and replacement of the scriptures, the latter being a substantial enterprise because the books are often borrowed by guests. When the satirical Book of Mormon musical ran on Broadway, so many guests were taking the book home from the New York Marriott Marquis hotel rooms to “learn the truth” that Dick’s foundation could barely keep the books in stock, according to the late Elder Robert D. Hales.[43] Since 2016 the scriptures in the hotel rooms are embossed with the invitation “Please Accept with Our Compliments.”[44]

In a letter to Bill and Dick in 1999, Elder David B. Haight wrote, “I remember when your father started this project many years ago, and how President David O. McKay heralded this unique and generous demonstration of the faith and devotion of the Marriott family.” As the then chair of the Church’s Missionary Executive Council, Elder Haight added, “We will never know the amount of good that is accomplished through your continuing [of] this [program].”[45] Bill and Dick have received numerous letters from converts who initially learned about the Church from the Book of Mormon in their hotel room, but the letter from President Thomas S. Monson in 2000 was particularly moving. He wrote: “I had the privilege this past weekend to dedicate the Louisville Kentucky Temple. Featured in one of the dedication sessions was the testimony of Richard B. Vivian, second counselor in the temple presidency, a capable and sweet-spirited man. He spoke of his conversion and said that it commenced when he read from a copy of the Book of Mormon he found in a dresser drawer in his room in a Marriott hotel. As I listened to this outstanding leader speaking at the microphone in the celestial room of the temple, I thought of you [Bill] and Dick and your parents and of your untiring efforts and unswerving loyalty in behalf of the Church in all that you have done.”[46]

Notes

[1] This article is adapted and expanded from Dale Van Atta, Bill Marriott: Success Is Never Final; His Life and the Decisions That Built a Hotel Empire (Salt Lake City: Shadow Mountain, 2019).

[2] . Though some called him J.W. or Willard, for most of his life he was known as Bill. For easier reading, the author has chosen to refer to the patriarch as J.W. and his son as Bill.

[3] . J.W. kept a journal for decades, beginning with his mission journal. This citation is from the September 17, 1921, entry. The journal, which will be referred to as JWM Journal, is kept in the archive room at Marriott International’s Bethesda, MD, headquarters.

[4] See chapter 11 herein, “The Seating of Senator Reed Smoot,” by Casey Paul Griffiths.

[5] . JWM Journal, 18 September 1921.

[6] . JWM Journal, 19 September 1921; for Congressperson Colton’s earlier visits to J.W.’s mission area, see JWM Journal of 1921: March 26 to 27 and August 14 to 15. Regarding the personal and business relationship between J.W. and Hugh Colton, see Lee Roderick, Bridge Builder: Hugh Colton, from Country Lawyer to Combat Hero (Washington, DC: Probitas Press, 2010).

[7] . JWM Journal, 28 January 1972.

[8] . “Connecticut Ave. Hot Shoppe Started the Marriott Empire,” Washington Post, 14 June 1959; Sterling Slappey, “How Big Tamale Became J. Willard Marriott and Made Hard Work Pay and Pay,” Washingtonian, January 1972, A18.

[9] . Robert O’Brien, Marriott: The J. Willard Marriott Story (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1977), 142–47.

[10] . Bill Marriott, remarks, Washington D.C. Stake conference, 27 April 1986; Richard Emery, Sam Cowley: Legendary Lawman (Springville, UT: Cedar Fort, 2004); Steven Nickel and William J. Helmer, Baby Face Nelson: Portrait of a Public Enemy (Nashville: Cumberland House, 2002). J. Edgar Hoover repeatedly called Cowley the “bravest man I ever knew.” The FBI director’s most eloquent tribute to Cowley came two decades after the latter’s death in a 7 May 1958 letter to J.W., with a seven-page attachment. Three decades later, Bill proudly delivered the tribute to President Gordon B. Hinckley, who gratefully acknowledged receipt in an 8 April 1986 letter.

[11] See chapter 18 herein, “The Washington Chapel: An Elias to the Washington D.C. Temple,” by Alonzo L. Gaskill and Seth Soha.

[12] . O’Brien, Marriott, 159–62. Brossard was the second president of the Washington D.C. Stake (after Benson), and J.W. was the third.

[13] . “No man ever had a better friend than J. Willard Marriott,” Benson affirmed. Sheri L. Dew, Ezra Taft Benson: A Biography (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1987), 158 and 164.

[14] . Howard S. Bennion (Mervyn’s brother), “One of the Lord’s Noblemen: Mervyn Sharp Bennion Captain, USS West Virginia, United States Navy” (unpublished manuscript, July 1943); Julian C. Lowe, “The Beginnings of Church Organization and Growth,” History of the Mormons in the Greater Washington Area (Washington, DC: Community Printing Services, 1991), 30.

[15] . Elder Russell M. Nelson interview with author, 15 August 2013. As stake president, J.W. interviewed the young lieutenant and called him to be second counselor in the Washington Ward bishopric, which was “a very important part of my spiritual development.” In fact, after J.W. died, Elder Nelson related to Bill in a 14 August 1985 letter that it was J.W. who gave him and his wife Dantzel “the opportunity, along with the encouragement and example, to seek first the kingdom of God knowing that all else would be appropriately taken care of.”

[16] . When Romney returned home after his participation in J.W.’s 1985 funeral service, including offering the dedication of his grave, he wrote Bill on 19 August: “As you probably know while your father had many close personal friends I had only one and none really close now that he has departed temporarily.”

[17] . Donna Marriott, interviews with author, 29 April 1982 and 18 April 2012.

[18] . “Elder Benson Family Plays Host: LDS Home Night Demonstrated to President and Mrs. Eisenhower,” Deseret News, Church Section, 12 February 1955; Bill Marriott stake conference address, “A Sensitive Leader: Priesthood Leadership in Church and Home,” 25 October 1981; Bill Marriott interviews with author, 19 December 2012 and 21 May 2013; Donna Marriott interview with author, 18 April 2012.

[19] . Bill Marriott interview about Christmas Eve 1957 incident with author, 30 April 2013; Dew, Ezra Taft Benson, 333.

[20] . Louie Estrada, “Alice Sheets Marriott Dies; Matriarch of Hotel Chain Was Active in Politics, Charities,” Washington Post, 19 April 2000, B05.

[21] . O’Brien, Marriott, 279–81.

[22] . See chapter 6 herein, “‘Make the Air with Music Ring’: A Personal Perspective on the Tabernacle Choir at Temple Square,” by Lloyd D. Newell.

[23] . J.W. Marriott to Milton A. Barlow, (Bill) Marriott, John S. Daniels, Frank Kimball, Wayne McAllister, Foster Kunz, and Alden Bowers, memorandum, 7 May 1959.

[24] . JWM Journal, 27 April 1959.

[25] . JWM Journal, 10 June 1961.

[26] . Minutes of Marriott Executive Committee Meeting, “Discussion of Las Vegas Hotel Proposal,” 4 September 1972.

[27] . Bill Marriott, interview by Kathi Ann Brown, 17 October 1996; Bill Marriott, interview with author, 9 July 2013.

[28] . JWM Journal, 30 October 1957. Eleven years later, President McKay strongly approached J.W. about a General Authority position in June 1968. J.W. recounted, “Milan Smith—Pres. of (Washington D.C.) Stake—came to breakfast. The First Presidency asked him to check on me to see if my health would permit a ‘big job’ in the church. I told him I couldn’t handle (such a) job with responsibility because of my heart trouble.” JWM Journal, 13 June 1968.

[29] . See chapter 19 herein, “The Washington D.C. Temple: Mr. Smith’s Church Goes to Washington,” by Maclane E. Heward.

[30] . Dieter F. Uchtdorf, interview with author, 5 September 2012.

[31] . “J. Willard Marriott,” Washington Post, 17 August 1985, A18.

[32] . Jeffrey R. Holland, interview with author, 26 June 2019.

[33] . Russell M. Nelson, interview with author, 26 June 2019.

[34] . Russell M. Nelson, interview with author, 15 August 2013.

[35] . Russell M. Nelson to Bill Marriott, 26 June 1990.

[36] . Beverly Campbell to Bill Marriott, 27 June 1990.

[37] . Beverly Campbell to Donna Marriott, 21 May 1996; 2006 “Invitation to the Ambassadorial & Congressional Dinner and Private Tour of His Premier Automobile Collection.”

[38] . Ann Santini, interview by David Brent and Enid Smith for the North America Northeast Area, 11 October 2017.

[39] . Many Deseret News and Church News accounts, including Lee Davidson, “Temple Lights Up with Call for Peace: French Envoy Is Honored by LDS at Rites in D.C.,” Deseret News, 4 December 2003 (online).

[40] . Santini, interview.

[41] . D. Todd Christofferson, interview with author, 9 August 2013; D. Todd Christofferson to Bill Marriott, 3 October 1996.

[42] . Ron Harrison (who served as Washington D.C. Stake president), interview with author, 2 August 2013. Bill has also been particularly helpful to Church relations with India and China, where, for example, he befriended Chinese ambassador Yang Jiechi, who was promoted to be China’s tenth foreign minister from 2006 to 2013. Edward Cody, “China Names New Foreign Minister,” Washington Post, 28 April 2007, A14.

[43] . Robert D. Hales, interview with author, 29 May 2012.

[44] . Mieka F. Wick (executive director, J. Willard and Alice S. Marriott Foundation) to author, email, 29 June 2020.

[45] . David B. Haight to Bill and Dick Marriott, 26 October 1999.

[46] . Thomas S. Monson to Bill Marriott, 21 March 2000.