Historic Sites in Washington, DC: A Photo Essay

Richard B. Crookston and R. Devan Jensen

Richard B. Crookston and R. Devan Jensen, “Historic Sites in Washington, DC: A Photo Essay,” in Latter-day Saints in Washington, DC: History, People, and Places, ed. Kenneth L. Alford, Lloyd D. Newell, and Alexander L. Baugh (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book), 465‒86.

Richard B. Crookston was the IT manager for Religious Education at Brigham Young University when this was published.

R. Devan Jensen was the executive editor for the Religious Studies Center at Brigham Young University when this was published.

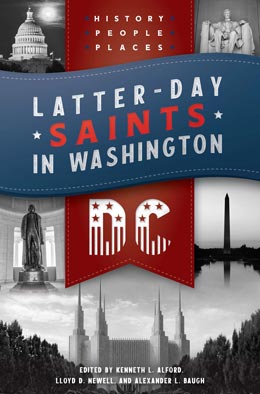

Dedicated in May 1922, the iconic Lincoln Memorial is a favored destination of visitors to the nation’s capital. This memorial has become a symbolic location for speeches on many important national issues, including Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech on race relations in August 1963. All photos by Richard B. Crookston unless otherwise noted.

Dedicated in May 1922, the iconic Lincoln Memorial is a favored destination of visitors to the nation’s capital. This memorial has become a symbolic location for speeches on many important national issues, including Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech on race relations in August 1963. All photos by Richard B. Crookston unless otherwise noted.

President George Washington laid the first cornerstone of the United States Capitol Building on 18 September 1793. Both wings were completed and connected by a wooden passageway in 1813. Although British troops set fire to the structure during the War of 1812, a rainstorm prevented its total destruction. During reconstruction in 1815, Benjamin Latrobe changed the interior design and introduced new materials, including marble from the Potomac.[1]

President George Washington laid the first cornerstone of the United States Capitol Building on 18 September 1793. Both wings were completed and connected by a wooden passageway in 1813. Although British troops set fire to the structure during the War of 1812, a rainstorm prevented its total destruction. During reconstruction in 1815, Benjamin Latrobe changed the interior design and introduced new materials, including marble from the Potomac.[1]

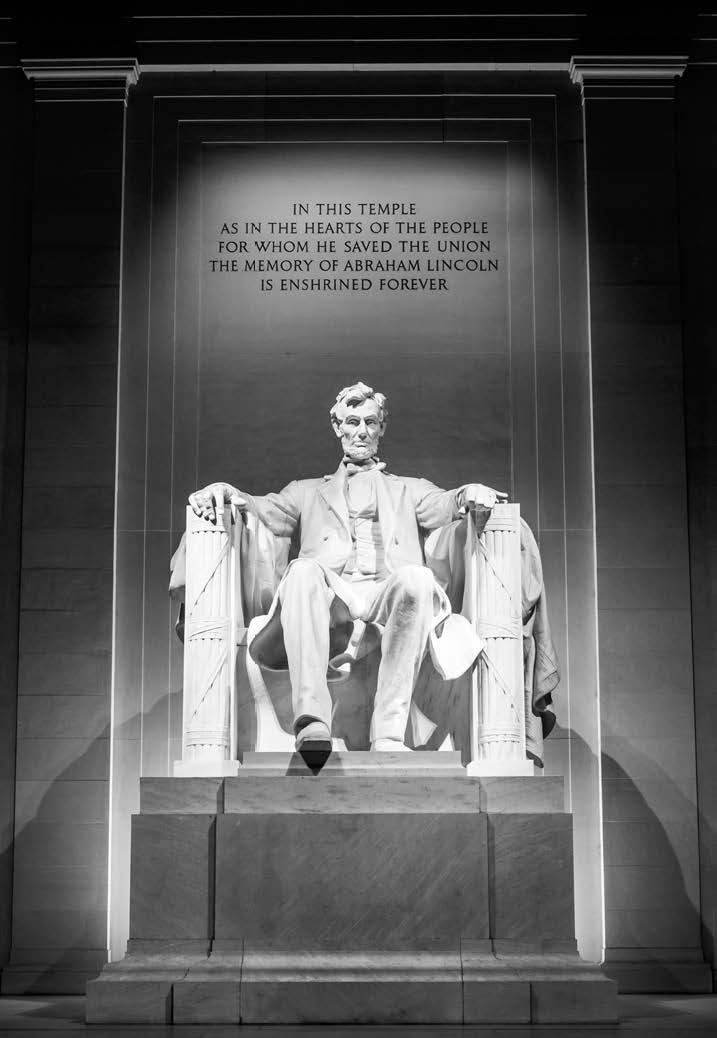

Boston architect Charles Bulfinch finished restoring the north and south wings and created chambers for the Supreme Court, the House, and the Senate by 1819. He completed updates to the central dome, landscaping, and decoration by 1826. Later Greek-Italian artist Constantino Brumidi painted The Apotheosis of Washington fresco.[2]

Boston architect Charles Bulfinch finished restoring the north and south wings and created chambers for the Supreme Court, the House, and the Senate by 1819. He completed updates to the central dome, landscaping, and decoration by 1826. Later Greek-Italian artist Constantino Brumidi painted The Apotheosis of Washington fresco.[2]

After Latter-day Saints were driven from the state of Missouri in 1838, they gathered in Illinois and decided in 1839 to send Sidney Rigdon to ask national leaders to gain redress for their losses. Judge Elias Higbee and Joseph Smith joined the expedition. Higbee reported in a letter to Hyrum Smith, “We arrived in this City on the morning of the 28th of November, and spent the most of that day in looking up a boarding house which we succeeded in finding. We found as cheap boarding as can be had in this city.” Smith and Higbee lodged just west of the U.S. Capitol Building on the corner of Missouri and 3rd Streets, a site that today would be located on Washington’s National Mall. Higbee recorded their visit to the White House thus: “[President Martin Van Buren] looked upon us with a kind of half frown and said, what can I do? I can do nothing for you,—if I do any thing, I shall come in contact with the whole State of Missouri.”[3] The Latter-day Saints, who were bitterly disappointed with his refusal to compensate their losses, eventually migrated to the Great Basin.

After Latter-day Saints were driven from the state of Missouri in 1838, they gathered in Illinois and decided in 1839 to send Sidney Rigdon to ask national leaders to gain redress for their losses. Judge Elias Higbee and Joseph Smith joined the expedition. Higbee reported in a letter to Hyrum Smith, “We arrived in this City on the morning of the 28th of November, and spent the most of that day in looking up a boarding house which we succeeded in finding. We found as cheap boarding as can be had in this city.” Smith and Higbee lodged just west of the U.S. Capitol Building on the corner of Missouri and 3rd Streets, a site that today would be located on Washington’s National Mall. Higbee recorded their visit to the White House thus: “[President Martin Van Buren] looked upon us with a kind of half frown and said, what can I do? I can do nothing for you,—if I do any thing, I shall come in contact with the whole State of Missouri.”[3] The Latter-day Saints, who were bitterly disappointed with his refusal to compensate their losses, eventually migrated to the Great Basin.

Latter-day Saints in the United States honor George Washington as one of the most important Founding Fathers. Mount Vernon is the former estate of George and Martha Washington and twenty other Washington family members. It overlooks the banks of the Potomac River in Fairfax County, Virginia. George Washington died at Mount Vernon on 14 December 1799. His last will provided for a new brick tomb to be constructed to replace his original tomb, which was already deteriorating.[4]

Latter-day Saints in the United States honor George Washington as one of the most important Founding Fathers. Mount Vernon is the former estate of George and Martha Washington and twenty other Washington family members. It overlooks the banks of the Potomac River in Fairfax County, Virginia. George Washington died at Mount Vernon on 14 December 1799. His last will provided for a new brick tomb to be constructed to replace his original tomb, which was already deteriorating.[4]

Arlington National Cemetery is built on the former plantation of George Washington Parke Custis, grandson of Martha Washington and step-grandson of President Washington. In 1857 Custis willed the property to his daughter, Mary Anna Randolph Custis, the wife of Robert E. Lee. The cemetery is the burial ground for more than four hundred thousand active-duty service members, veterans, and family members, including many Latter-day Saints.[5]

Arlington National Cemetery is built on the former plantation of George Washington Parke Custis, grandson of Martha Washington and step-grandson of President Washington. In 1857 Custis willed the property to his daughter, Mary Anna Randolph Custis, the wife of Robert E. Lee. The cemetery is the burial ground for more than four hundred thousand active-duty service members, veterans, and family members, including many Latter-day Saints.[5]

The Tomb of the Unknown Soldier or the Tomb of the Unknowns is dedicated to deceased U.S. service members whose remains have not been identified. Tomb guards are soldiers of the U.S. Army. The soldier “walking the mat” wears no rank insignia so as not to outrank the Unknowns.[6]

The Tomb of the Unknown Soldier or the Tomb of the Unknowns is dedicated to deceased U.S. service members whose remains have not been identified. Tomb guards are soldiers of the U.S. Army. The soldier “walking the mat” wears no rank insignia so as not to outrank the Unknowns.[6]

The Three Soldiers (also called The Three Servicemen) is a bronze statue by Frederick Hart. Installed a few feet from the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Wall at the National Mall, the sculpture was unveiled on Veterans Day, 11 November 1984, and portrays a Caucasian, an African American, and a Latino American.[7]

The Three Soldiers (also called The Three Servicemen) is a bronze statue by Frederick Hart. Installed a few feet from the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Wall at the National Mall, the sculpture was unveiled on Veterans Day, 11 November 1984, and portrays a Caucasian, an African American, and a Latino American.[7]

The Vietnam Veterans Memorial at night.

The Vietnam Veterans Memorial at night.

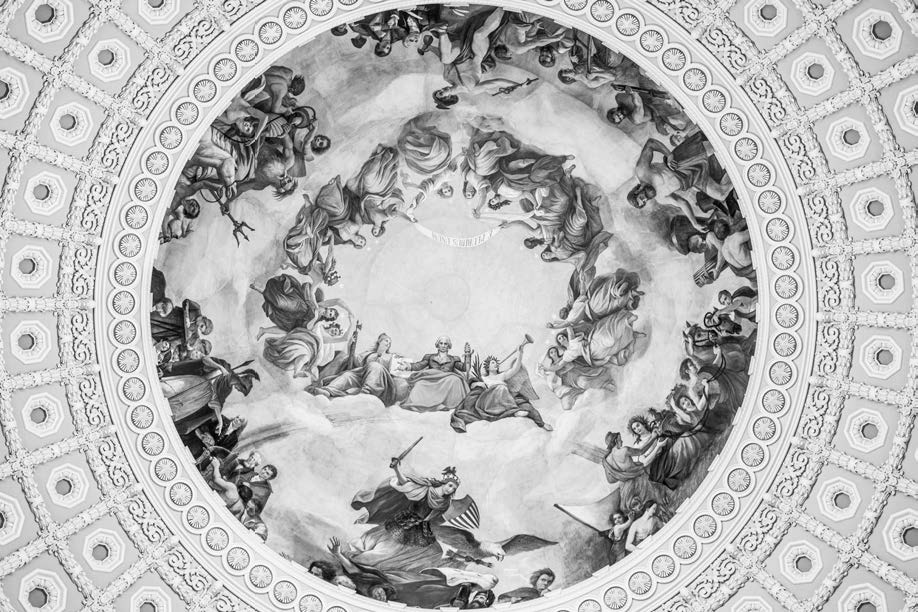

The Rare Books room in the Library of Congress’s Thomas Jefferson Building houses important Latter-day Saint publications, such as an 1830 Book of Mormon, an 1833 Book of Commandments, an 1851 Pearl of Great Price, and a Book of Mormon in the Deseret Alphabet (shown here). Additional important documents and publications from American history reside here—such as a copy of the Emancipation Proclamation signed by Abraham Lincoln, a handwritten letter by Abraham Lincoln, and the first Bible published in America—as well as other rare items from the Library of Congress’s extensive collections, including a life mask of Abraham Lincoln.

The Rare Books room in the Library of Congress’s Thomas Jefferson Building houses important Latter-day Saint publications, such as an 1830 Book of Mormon, an 1833 Book of Commandments, an 1851 Pearl of Great Price, and a Book of Mormon in the Deseret Alphabet (shown here). Additional important documents and publications from American history reside here—such as a copy of the Emancipation Proclamation signed by Abraham Lincoln, a handwritten letter by Abraham Lincoln, and the first Bible published in America—as well as other rare items from the Library of Congress’s extensive collections, including a life mask of Abraham Lincoln.

The Washington National Cathedral (officially titled the Cathedral Church of Saint Peter and Saint Paul in the City and Diocese of Washington), is the second-largest cathedral in the United States and the sixth-largest in the world.[8]

The Washington National Cathedral (officially titled the Cathedral Church of Saint Peter and Saint Paul in the City and Diocese of Washington), is the second-largest cathedral in the United States and the sixth-largest in the world.[8]

The Lincoln Bay of the Washington National Cathedral is an alcove with a massive bronze statue of President Abraham Lincoln, a gift from his great-grandson Lincoln Isham. The statue portrays the nation’s sixteenth president kneeling in prayer before leaving his home in Springfield, Illinois, on his way to the presidency.[9]

The Lincoln Bay of the Washington National Cathedral is an alcove with a massive bronze statue of President Abraham Lincoln, a gift from his great-grandson Lincoln Isham. The statue portrays the nation’s sixteenth president kneeling in prayer before leaving his home in Springfield, Illinois, on his way to the presidency.[9]

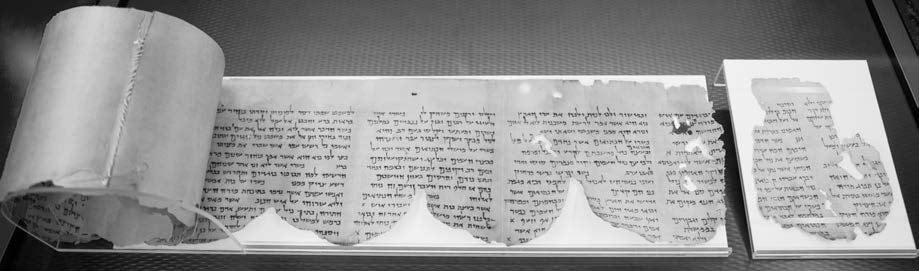

The Museum of the Bible houses ancient Hebrew artifacts such as a scroll containing commentary on the book of Habukkuk dating to 30 BC–AD 30. Such artifacts honor the ancient Hebrew origins of the Bible.

The Museum of the Bible houses ancient Hebrew artifacts such as a scroll containing commentary on the book of Habukkuk dating to 30 BC–AD 30. Such artifacts honor the ancient Hebrew origins of the Bible.

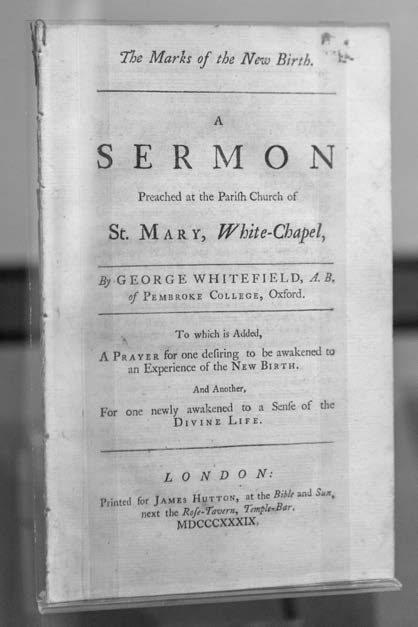

The museum offers a substantial gallery on the Great Awakening in America (1730s–1760s). The Great Awakening was a wave of religious fervor gripping the American colonies. Its most popular leader was the Anglican priest George Whitefield, who preached a message of new birth.

The museum offers a substantial gallery on the Great Awakening in America (1730s–1760s). The Great Awakening was a wave of religious fervor gripping the American colonies. Its most popular leader was the Anglican priest George Whitefield, who preached a message of new birth.

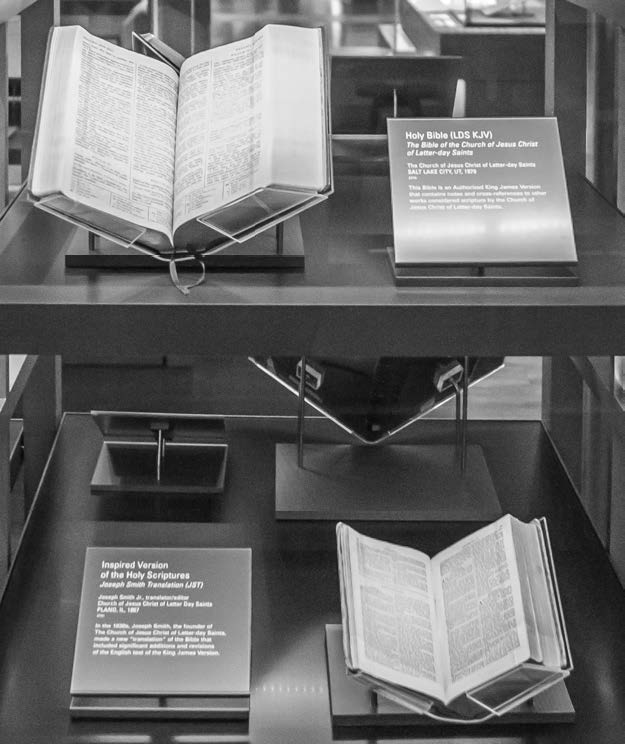

The Joseph Smith Translation and 1979 Latter-day Saint edition of the Bible appear on display as well.

The Joseph Smith Translation and 1979 Latter-day Saint edition of the Bible appear on display as well.

The Washington Chapel on Sixteenth Street was built to serve the original Washington D.C. Ward and was patterned after the Salt Lake Temple. A statue of the angel Moroni was originally on top of the 160-foot spire. The chapel is still standing, although it was sold to the Unification Church. A mosaic of the Sermon on the Mount still welcomes visitors at the entrance. Different floral depictions grace the windows, including the sego lily.

The Washington Chapel on Sixteenth Street was built to serve the original Washington D.C. Ward and was patterned after the Salt Lake Temple. A statue of the angel Moroni was originally on top of the 160-foot spire. The chapel is still standing, although it was sold to the Unification Church. A mosaic of the Sermon on the Mount still welcomes visitors at the entrance. Different floral depictions grace the windows, including the sego lily.

In the main room of the Washington Chapel, the east windows picture the North American continent, the Hill Cumorah, and the Rocky Mountains, where the Saints established themselves after their long persecutions. The south windows show the South American continent and an ancient temple, recalling the early history of the Western Hemisphere as told in the Book of Mormon. The north windows portray the continent of Europe, sailing vessels of the early immigrants, and the barren plains crossed by the pioneers, symbolic of the gathering of Saints to Zion.[10]

In the main room of the Washington Chapel, the east windows picture the North American continent, the Hill Cumorah, and the Rocky Mountains, where the Saints established themselves after their long persecutions. The south windows show the South American continent and an ancient temple, recalling the early history of the Western Hemisphere as told in the Book of Mormon. The north windows portray the continent of Europe, sailing vessels of the early immigrants, and the barren plains crossed by the pioneers, symbolic of the gathering of Saints to Zion.[10]

Auditorium of Daughters of the American Revolution Constitution Hall, 1934. Harris and Ewing photograph collection, Library of Congress. The Daughters of the American Revolution’s Constitution Hall accommodated stake conferences for the Washington Stake after the membership proved too large for the Washington Chapel and George Washington University’s Lisner Auditorium.

Auditorium of Daughters of the American Revolution Constitution Hall, 1934. Harris and Ewing photograph collection, Library of Congress. The Daughters of the American Revolution’s Constitution Hall accommodated stake conferences for the Washington Stake after the membership proved too large for the Washington Chapel and George Washington University’s Lisner Auditorium.

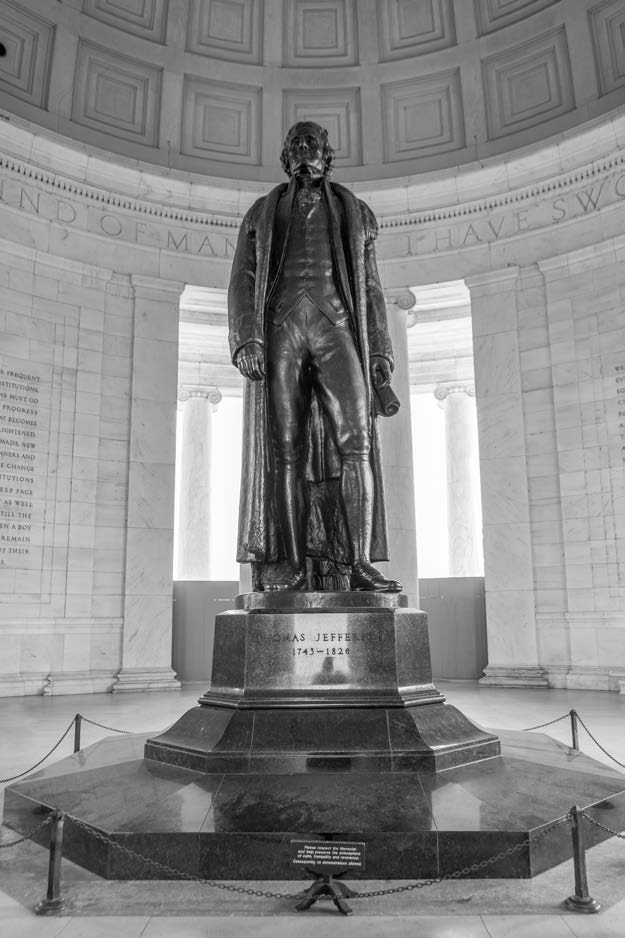

Elbert D. Thomas, a Latter-day Saint senator from Utah, was the chairman of the Thomas Jefferson Memorial Commission. He had a lifelong fascination with Jefferson and made lasting contributions toward the memorial. His research prompted him to write Thomas Jefferson: World Citizen (published in 1942), and he selected the quotes that graced the memorial wall in 1943. He became chair in 1944 and oversaw the final stages of the memorial, including the creation of the Jefferson statue.

Elbert D. Thomas, a Latter-day Saint senator from Utah, was the chairman of the Thomas Jefferson Memorial Commission. He had a lifelong fascination with Jefferson and made lasting contributions toward the memorial. His research prompted him to write Thomas Jefferson: World Citizen (published in 1942), and he selected the quotes that graced the memorial wall in 1943. He became chair in 1944 and oversaw the final stages of the memorial, including the creation of the Jefferson statue.

On panel 3, Thomas amalgamates four Jefferson sources into one quote, making it seem as if Jefferson were “a believer in emancipation, if not abolition, rather than a slave owner.”[11] To the left of the entrance is a carved inscription about the memorial with the name of Elbert D. Thomas listed as “CHAIRMAN 1944” (in small print to the right of his name).

On panel 3, Thomas amalgamates four Jefferson sources into one quote, making it seem as if Jefferson were “a believer in emancipation, if not abolition, rather than a slave owner.”[11] To the left of the entrance is a carved inscription about the memorial with the name of Elbert D. Thomas listed as “CHAIRMAN 1944” (in small print to the right of his name).

Washington D.C. Temple in Kensington, Maryland. Carol M. Highsmith Archive, Library of Congress.

Washington D.C. Temple in Kensington, Maryland. Carol M. Highsmith Archive, Library of Congress.

The Washington D.C. Temple is an important house of worship for Latter-day Saints in the DC area. This cutaway model in the visitors’ center shows the interior layout. At the time of the temple’s completion, its district included Church members in thirty-one U.S. states and the District of Columbia, seven Canadian provinces, Cuba, Haiti, Puerto Rico, the Bahamas, and the Dominican Republic. It is the Church’s third-largest temple and the tallest; its easternmost spire is 288 feet tall (88 meters).[12]

The Washington D.C. Temple is an important house of worship for Latter-day Saints in the DC area. This cutaway model in the visitors’ center shows the interior layout. At the time of the temple’s completion, its district included Church members in thirty-one U.S. states and the District of Columbia, seven Canadian provinces, Cuba, Haiti, Puerto Rico, the Bahamas, and the Dominican Republic. It is the Church’s third-largest temple and the tallest; its easternmost spire is 288 feet tall (88 meters).[12]

In May 1999, the Church bought a four-story, 1920s-era brick building that once housed offices of the nearby George Washington University Medical School. The Church then renovated and expanded the building, renaming it the Milton A. Barlow Center.[13] During the dedication ceremony in 2002, Kathleen B. Morgan, said that her father, Milton, dreamed of a “reverse migration” from the West and felt that creating a “Washington Center” could help in that goal.[14] The building is an important gathering place for DC-area Saints, housing the Church’s Office of International and Government Affairs, a chapel and other religious facilities for a church congregation, classes for an institute program for young adults, and apartments and classrooms for Washington Seminar interns from Brigham Young University.

In May 1999, the Church bought a four-story, 1920s-era brick building that once housed offices of the nearby George Washington University Medical School. The Church then renovated and expanded the building, renaming it the Milton A. Barlow Center.[13] During the dedication ceremony in 2002, Kathleen B. Morgan, said that her father, Milton, dreamed of a “reverse migration” from the West and felt that creating a “Washington Center” could help in that goal.[14] The building is an important gathering place for DC-area Saints, housing the Church’s Office of International and Government Affairs, a chapel and other religious facilities for a church congregation, classes for an institute program for young adults, and apartments and classrooms for Washington Seminar interns from Brigham Young University.

Notes

[1] “History of the U.S. Capitol Building,” Architect of the Capitol (website).

[2] “History of the U.S. Capitol Building,” Architect of the Capitol (website).

[3] Joseph Smith and Elias Higbee to Hyrum Smith, “Corner Missouri and 3d Street,” Letterbook 2:85–88, Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

[4] “Mount Vernon,” History.com.

[5] History.com editors, “Arlington National Cemetery,” History.com.

[6] “Tomb of the Unknown Soldier (Arlington),” Wikipedia.

[7] Frederick Hart, “Vietnam Veterans Memorial, Three Soldiers,” Histories of the National Mall, Mallhistory.org.

[8] “National Cathedral,” Sacred Destinations (website).

[9] “Lincoln Bay,” Cathedral.org.

[10] “Washington D.C. Ward,” Historic LDS Architecture (blog).

[11] Hahna Cho, Notes on the State: Jefferson Beyond Jefferson, 12 July 2008, https://

[12] “History of the Washington DC Temple,” https://

[13] Lee Davidson, “New D.C. Home for LDS Offices,” Deseret News, 13 April 2002.

[14] Mauri Earl, “Barlow Center Dedicated in Washington, D.C.,” Church News, 18 April 2002.