Ezra Taft Benson’s Influence on Washington

Mark D. Ogletree

Mark D. Ogletree, “Ezra Taft Benson's Influence on Washington,” in Latter-day Saints in Washington, DC: History, People, and Places, ed. Kenneth L. Alford, Lloyd D. Newell, and Alexander L. Baugh (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book), 241‒60.

Mark D. Ogletree was an associate professor of Church history and doctrine at Brigham Young University when this was published.

The family is the rock foundation, the cornerstone, of civilization.

The Church will never be stronger than its families,

and this nation will never rise above its home and families.

—Elder Ezra Taft Benson[1]

Ezra Taft Benson, February 1953, newly appointed secretary of agriculture. Utah State Historical Society.

Ezra Taft Benson, February 1953, newly appointed secretary of agriculture. Utah State Historical Society.

Ezra Taft Benson and his wife, Flora, were devoted to raising a righteous posterity. They spent many hours with their children by teaching them the gospel, working side by side with them, and recreating with them. Both Ezra and Flora Benson were raised in strong families. Consequently, family life was the core of their existence, and that practice continued through their lives. When President Benson spoke in Seattle, Washington, in 1976 at a National Family Night program, he stated, “Some of the sweetest, most soul-satisfying impressions and experiences of our lives are those associated with home, family, children, brothers, and sisters.”[2] President Benson went on to explain that he and his wife had hoped to have twelve children—they had six instead. Flora quipped, “If we could have just had twins each time we would have made it.”[3]

The Preparatory Years: Boise and Washington, DC (1930–43)

In the fall of 1930, Ezra was appointed to the Idaho State University Extension Service, headquartered in Boise. By 1931, he became executive secretary of the Idaho Cooperative Council for farmers. During the 1930s, Ezra began a climb to prominence, becoming notable in the agriculture industry not just locally but also nationally. Many leaders in national organizations viewed him as a man with great leadership potential.

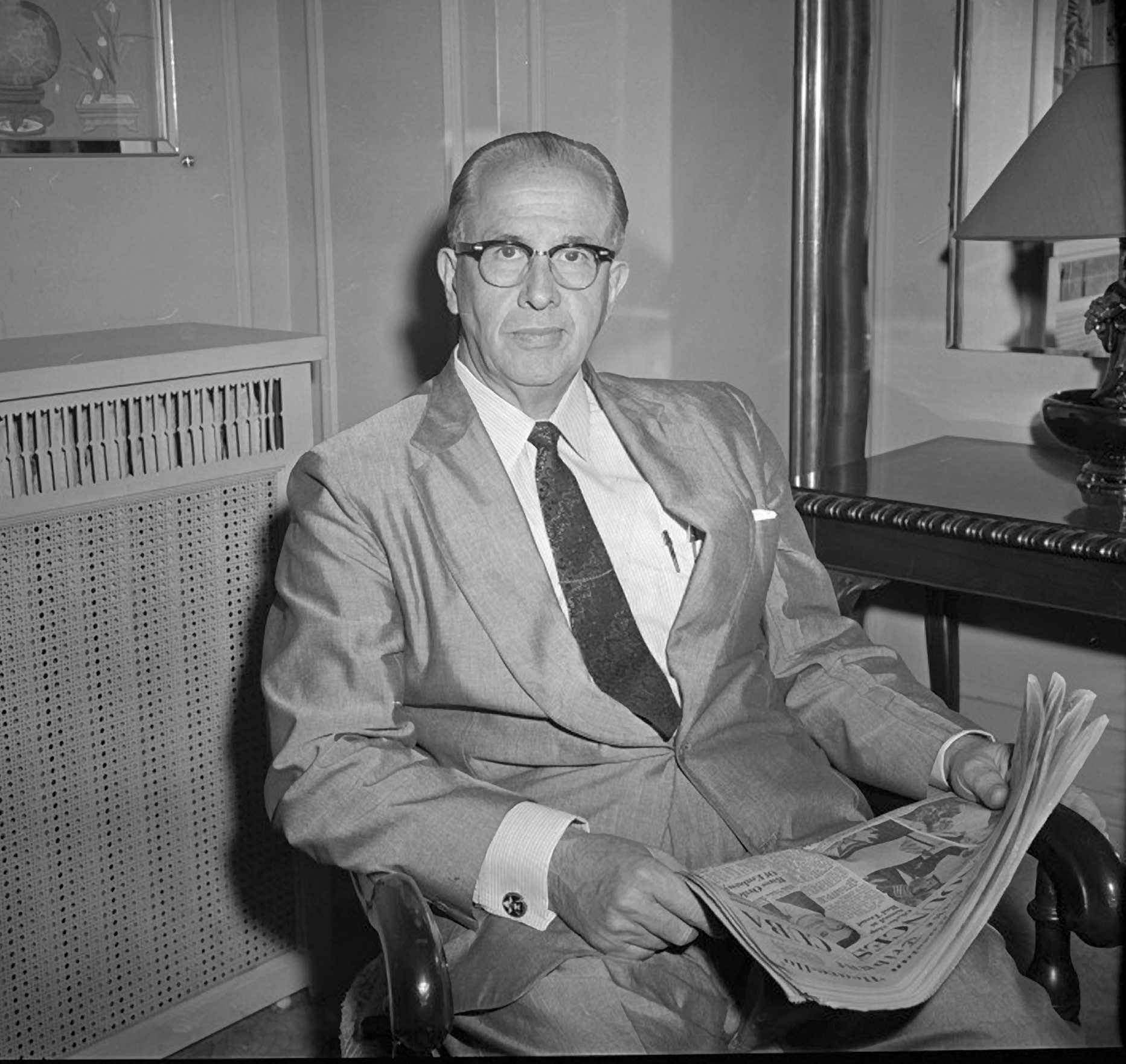

Secretary Ezra Taft Benson, September 1960, taking time to catch up on the news. Utah State Historical Society

Secretary Ezra Taft Benson, September 1960, taking time to catch up on the news. Utah State Historical Society

While living in Idaho and serving in the stake presidency, Ezra took a short leave of absence to work on a doctorate at the University of California, Berkeley.[4] He and his family lived in California for nine months while Ezra worked feverishly on his graduate work. Although he never finished his degree, studying at Berkeley raised his visibility within the agricultural field.[5] In 1938 Ezra spoke at the annual National Council of Farmer Cooperatives conference in Washington, DC.[6] When the National Council looked for a new executive secretary, Ezra’s name rose to the top. The National Council of Farmer Cooperatives was a large federation, comprising 4,600 farmers market organizations.[7] Although Ezra had little interest in the job, the National Council remained interested in him. Still needing persuading, Ezra counseled with President David O. McKay, who helped him understand that the Church needed people in key positions in the nation’s capital.[8] Ezra accepted the position in March of 1939 and soon moved his family to Washington, DC.

The Bensons immersed themselves in the Church and the community. The family frequently hosted dances, parlor games, ping-pong, and other activities in their home.[9] Holidays became a special time to gather—especially for those who did not have family nearby. Reminiscing on those early days in Washington, President Benson explained, “Almost every year we held a Christmas fireside in our home. Sometimes over a hundred young people crowded inside and sat on the floor, steps, anywhere they could find a place. My wife and our daughters prepared wonderful refreshments for everyone, and I was honored to talk about the Savior and His mission. It was some of these simple occasions that brought greatest satisfaction.”[10]

Mr. Benson Goes to Washington—Again (1953–61)

The Bensons left Washington in 1943 when Ezra was called to serve in the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, and from 1943 to 1952 he was fully engaged in apostolic duties. After World War II, he spent a substantial amount of time in Europe, where he served as mission president and helped distribute welfare supplies to many in need. For the Bensons, life changed significantly after 4 November 1952 when Dwight D. Eisenhower won the presidency and appointed Ezra Taft Benson as secretary of agriculture. Ezra had no desire to serve in the president’s cabinet.[11] However, with President McKay’s support and encouragement,[12] Ezra finally accepted the appointment, and the Benson family returned to Washington, DC. Elder Benson became the first member of a clergy to serve in the cabinet in over a century.[13]

Secretary Ezra Taft Benson, his wife, Flora, and their youngest daughter, Flora Beth, traveling together in the spring of 1955. Library of Congress.

Secretary Ezra Taft Benson, his wife, Flora, and their youngest daughter, Flora Beth, traveling together in the spring of 1955. Library of Congress.

Many agricultural leaders cheered his appointment. Victor Emanuel, an industrial leader, said, “I have known Ezra Taft Benson for many years, and I cannot think of a wiser selection for the post of Secretary of Agriculture. Ezra Benson combines the practical outlook of farmers and agriculture with spiritual qualities of the highest degree. . . . I predict that Ezra Taft Benson . . . will be one of the great secretaries of all time.”[14] Edward R. Eastman, editor of the American Agriculturist, declared Ezra’s appointment was “the best news farmers of America have had in years.”[15] J. A. McConnell, executive vice president of the Grange Lee Federation (one of America’s largest farming cooperatives), predicted that “Benson’s high character will make him one of the great, if not the greatest, agricultural secretaries since the establishment of an agricultural department in the executive branch of our government. He will be completely fair, will listen to the proponents of ideas from every section of the country and from every segment of agriculture, and will make his decisions based on an honest and intelligent appraisal of the facts.”[16]

Ezra did not waste time making his presence known as he urged President Eisenhower to begin cabinet meetings with prayer. President Eisenhower accepted the invitation, and the practice was instituted—with Ezra offering the first prayer.[17] A Time magazine story titled “Apostle at Work” mentioned that department meetings commenced with prayer,[18] and coworkers were never surprised when they walked in on the secretary to find him praying. One colleague quipped, “‘He spends as much time on his knees as he does on his feet.’ For the tireless Benson machine, prayer is the basic fuel.”[19]

Walking into a Minefield

A 1954 Herblock Cartoon, © The Herb Block Foundation.

A 1954 Herblock Cartoon, © The Herb Block Foundation.

Although many Church members—including President David O. McKay—were excited for his appointment, Ezra understood he was walking into a minefield. On 1 December 1952, a month prior to Eisenhower’s inauguration, he told students at Brigham Young University, “I didn’t want to be Secretary of Agriculture. I can’t imagine anyone in his right mind wanting it.”[20] He further explained, “Because I know something of what it entails, I know something of the crossfires, the pressures, the problems, the difficulties.”[21]

Ezra’s concerns about becoming secretary were well founded. One month into the new administration, Barron’s National Business and Financial Weekly reported, “Because of the current decline in farm prices—down 11% from a year ago—Mr. Benson finds himself sitting on the hottest of seats as boss of one of Washington’s largest Cabinet empires.”[22] He quickly became a favorite target of the press, politicians, and farmers. There was no honeymoon period. Many pundits predicted he would be the first cabinet member to resign.[23] Historian Francis M. Gibbons observed that the press, hostile opponents, and even the farming community were quick to attack. “This controversy,” Gibbons wrote, “at the threshold of his administration robbed Secretary Benson of the usual period of grace accorded to new officeholders in Washington. His opponents lost no time in attacking him in Congress and in the media. He was put on the defensive immediately. His opponents scrutinized his statements intently, looking for hooks on which to hang their criticisms.”[24] The Farm Journal reported, “Ezra Benson is going to shock Washington. He’s in the habit of deciding everything on principle.”[25] Many felt he was too outspoken and passionate about his beliefs. He believed that “to sit in silence when the truth should be told makes cowards of men.”[26]

A 1957 Herblock Cartoon, © The Herb Block Foundation.

A 1957 Herblock Cartoon, © The Herb Block Foundation.

Ezra did not waste any time clearing, purging, and reorganizing the Department of Agriculture. He felt the department was a bureaucracy draining taxpayer money. He reorganized the department’s twenty agencies into four divisions. “Some agencies were combined; some transferred to other departments; and some eliminated.”[27] Heated criticism was directed toward Secretary Benson as he shuffled the department in seemingly partisan ways by ousting Democrats M. L. Wilson, Louis Bean, and Claude Wickard. Some claimed the “purge constituted an example of pure ideological zealotry.”[28]

One of his first department memorandums outlined his expectations. “The people of this country,” he wrote, “have a right to expect that every one of us will give a full day’s work for a day’s pay.”[29] Many employees took offense, feeling the remark implied that “all bureaucrats were inherently lazy, especially those hired by Democrats.”[30] The press had a heyday with the memorandum.

Ezra’s first speech as secretary—addressing the Central Livestock Association in St. Paul, Minnesota, in February 1953—landed like a lead balloon as he pleaded with cattle ranchers to shut government beef bounties, condemned price supports, and urged a “return to the fundamental virtues which have made this nation great.”[31] He was widely criticized for the speech. During the next eight years, the scrutiny and criticism only intensified. His critics were relentless. By the time the Eisenhower administration completed their tenure in 1961, Ezra would be one of only two cabinet members who served the entire eight years. Secretary Benson would be in the spotlight during the entire administration, being viewed “as one of the most active and controversial figures of the administration and the national Republican party. Fierce critiques and frequent calls for his resignation were matched by an equal outpouring of accolades and genuine respect.”[32]

While serving in the cabinet, Secretary Benson developed into a strong and opinionated leader. Historian Patrick Q. Mason argued that Ezra Taft Benson “took clear and often controversially conservative positions on the many of the ‘historic conflicts of our time,’ including anticommunism, the proper role of government, civil rights, church and state, the women’s movement, international and domestic conflicts, and the culture wars. Due to his prominence both internally and externally, Benson thus [became] a prism through which the American public and the media perceived Latter-day Saints and their religion.”[33]

Perhaps at the heart of all controversy was Secretary Benson’s strong views against socialism and communism. He believed our nation was at war with international communism.[34] He viewed communism as a significant threat to American freedoms. Communism “is a total philosophy of life, atheistic and utterly opposed to all we hold dear,” he said.[35] On other occasions he remarked, “I’d rather be dead than lose my liberty”[36] and observed that communism offered “the death knell of freedom and all we hold dear.”[37] He felt that American agriculture was drifting toward socialism—evidenced by government bailouts, subsidies, and federal meddling.

Ezra supported government-funded agricultural research and marketing but held that government assistance should come only in times of emergency.[38] It was Ezra’s position that stored food and commodities were a drain on taxpayers and “a threat to the farmer’s opportunity to obtain a fair portion of the prosperity being enjoyed all around him.”[39] Shortly after taking office, he crafted a 1,200-word “General Statement” on farming, which declared, “It is impossible to help people permanently by doing for them what they could and should do for themselves. It is a philosophy that believes in the supreme worth of the individual as a free man, as a child of God, that believes in the dignity of labor and the conviction that you cannot build character by taking away man’s initiative and independence.”[40]

Ezra believed strongly that the government should never do for individuals what they could do for themselves. He worried too many American farmers were becoming dependent on the federal government. He likened the situation to “a political fairy that will wave a wand and all vexations and anxieties will disappear.”[41] He stated, “It is doubtful if any man can be politically free who depends upon the state for sustenance. A completely planned and subsidized economy weakens initiative, discourages industry, destroys character, and demoralizes the people.”[42]

Secretary Ezra Taft Benson, March 1955, on his way to another meeting. Utah State Historical Society.

Secretary Ezra Taft Benson, March 1955, on his way to another meeting. Utah State Historical Society.

President Eisenhower was in favor of agricultural price support—at least initially, which Ezra believed to be misguided.[43] Ezra agreed, though, to abide by the president’s pledge to farmers to continue price supports for a short time.[44] Nevertheless, Secretary Benson became the most criticized member of Eisenhower’s cabinet. Time magazine reported, “Of all the storms that rage about the heads of Washington officials, none matches in intensity and duration the high, fine gale that whistles about Secretary of Agriculture Ezra Taft Benson.”[45]

Eisenhower was “constantly urged by others to drop the Secretary from his Cabinet.”[46] Walter Judd and Arthur Miller, members of congress from Minnesota and Nebraska respectively, met with Secretary Benson and urged him to resign. They predicted that if he did not step down, their party would lose 20–25 seats in the next election. Secretary Benson replied that he would not quit but would “continue to pursue a course which I believe is best for our farmers.”[47] South Dakota senator Karl Mundt cautioned, “I am writing to tell you candidly . . . we cannot come close to electing a Republican House of Representatives or a Republican Senate in 1958 unless Secretary of Agriculture Benson is replaced by somebody who is personally acceptable to the farmers of this country.”[48]

Eisenhower was reelected in November 1956; however, during the mid-term elections in 1958, Republicans lost forty-seven seats in the House of Representatives and thirteen seats in the Senate. The Midwestern farm belt experienced the greatest losses. Catholic University political scientist Norman Ornstein called Ezra Taft Benson the “Achilles heel” of the Eisenhower administration, placing the Republican losses squarely on his shoulders.[49] Yet Secretary Benson remained unflappable. “Resign? I am resigned to one thing—to do my duty as I see it, to continue my flight for a prosperous, expanding, and free agriculture.”[50] He told Senator Kenneth B. Keating, “I’m not in the habit of running away from a fight—a tough job . . . I didn’t ask for this job and I’m very busy trying to do it the best way I can.”[51]

Importantly, Eisenhower remained loyal to his agriculture secretary. “The only way ‘you can get Ezra discharged from the Cabinet . . . is to ask for my resignation as President. If you want that, then you can get Ezra. It’s just that simple.’”[52] Ezra initially pledged he would serve two years because he longed to return to Utah. Informing the president that he considered resigning, Eisenhower retorted, “If you quit, I quit.”[53]

Despite the criticism and ridicule Secretary Benson received, he conducted himself as a disciple of Jesus Christ. A U.S. News & World Report article observed, “As secretary of agriculture, Mr. Benson has encountered little but frustration and criticism. . . . [He] has taken the criticisms and frustrations placidly. No one has seen him angered. His manner is warm and friendly, his smile habitual. He speaks quickly, but earnestly.”[54] Historian Francis M. Gibbons believed poise and self-control were two of Ezra’s most salient characteristics. He wrote, “In more than twenty years of personal association with him, in conversations with others who knew him well, and in reviewing voluminous documents about his life while writing his biography, I found or learned of no instance when he allowed his temper or anger to dominate his conduct. I know of many instances when he was heavily provoked, but in no case did he ever lose his temper. He was always in control of himself. His feelings were kept in check.[55]

The Benson Family’s Influence

With all of the opposition Ezra faced, his family became his refuge, and his home was his sanctuary. Many individuals in Washington, DC, admired the Benson family. They were inclusive, always inviting others to become part of what made them happy—the gospel of Jesus Christ. No matter how strongly the pressure intensified, the Bensons did not compromise their standards. “As the embodiment of family, home, and the American way, the Bensons were the focus of perhaps the most positive attention the Church had ever received throughout the country.”[56]

Newly appointed secretary of agriculture Ezra Taft Benson with his wife, Flora, and their four daughters, spending time together as a family, February 1953. Utah State Historical Society.

Newly appointed secretary of agriculture Ezra Taft Benson with his wife, Flora, and their four daughters, spending time together as a family, February 1953. Utah State Historical Society.

Consequently, many people grew to respect their morals and religious principles. For instance, at the annual convention of the World Food and Agriculture Organization in Rome, Italy, “The customary cocktail hour was replaced with a soft drink and fruit juice reception in honor of Elder Benson’s Word of Wisdom standards.”[57] Patrick Q. Mason summarized the Benson’s influence this way: “The entire Benson family came to represent Mormon normality by way of exemplifying the ideals of postwar American domestic life. Time [magazine] gave its readers a peek into the Benson household, which showed the family praying, reading scriptures, doing chores, dancing around the jukebox, and together deciding curfews and how much television the kids could watch. . . . Together the family plans the week’s meals and shopping. . . . In the late 1950s, Leave it to Beaver could have been set in the Benson home—with troublemaking Eddie Haskell nowhere to be found.”[58]

Flora’s Influence

During the Eisenhower administration, Ezra and Flora enjoyed their relationship with members of the cabinet and their spouses. The wives of cabinet members often gathered for luncheons and other social activities. Sometimes they would gather at the White House; sometimes in their homes. Ezra wrote, “Another family joy was to have guests in our home. At such times we always tried to arrange to have the children at the table also, to participate in the delightful conversation of the evening.”[59]

In May 1954 the Bensons hosted a luncheon. Attendees included Mamie Eisenhower, Pat Nixon, Rachel Adams, the cabinet wives, and Oveta Hobby (the first secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare). Flora and her children catered the entire event themselves, spending weeks “carefully planning a menu, cleaning their home, preparing entertainment, and brushing up on etiquette and protocol. As was common practice in the Benson household, no outside help was hired for the affair.”[60] When Ezra saw how much work Flora was putting into the party, he expressed his concern. Flora countered, “This isn’t just a luncheon to me. It’s something more than that. I want to show that it’s possible to uphold the standards of the Church and have a wonderful time, too.”[61]

The day of the luncheon, Flora greeted her guests by saying, “‘You’ll find things a bit different in our home. We don’t serve cocktails, or play cards, there is no smoking and no tea or coffee—but we’ll try to make it up to you in our own way, and we hope you enjoy our home.”[62] Instead of cocktails, the Bensons served ginger ale and home-bottled apricot juice—which was a big hit.[63] They served a delicious meal and provided a wonderful family program of music, poetry, and ballet. The BYU Madrigal singers also performed, and their daughter Barbara was one of the soloists. Their son Reed delivered Wordsworth’s poem “Happy Warrior,” dedicating it to President Eisenhower. Mamie Eisenhower was so impressed that she invited all twenty-eight Madrigal singers for a White House tour. Flora said, “The most exciting part was the beautiful letters we received afterward from women telling us what a thrill it was to experience a touch of ‘Mormonism’ and family cooperation and what wonderful youth the BYU singers were.”[64]

Throughout the Eisenhower administration, the Bensons continued to have a positive effect on the cabinet and their families. After Ezra shared passages from the Book of Mormon with the president, he received a personal note thanking him “for drawing on your wide knowledge of the Book of Mormon to send me certain prophecies and revelations. The quotations I have read with great interest . . .”[65] On another occasion, the Bensons invited the Eisenhower’s for Family Home Evening in their home.[66] The President and First Lady remained friends with Ezra and Flora after Eisenhower’s presidency.

The Edward R. Murrow Experience

Senator Arthur Watkins, left, secretary of agriculture Ezra Taft Benson, center, and President Dwight D. Eisenhower, right, greet an unidentified woman at a speaking engagement, September 1958. Utah State Historical Society.

Senator Arthur Watkins, left, secretary of agriculture Ezra Taft Benson, center, and President Dwight D. Eisenhower, right, greet an unidentified woman at a speaking engagement, September 1958. Utah State Historical Society.

Edward R. Murrow hosted the popular television program Person to Person from 1953 to 1961—interviewing professional athletes, politicians, and celebrities, including Senator John F. Kennedy, Elizabeth Taylor, Roy Campanella, Dean Martin, Jerry Lewis, Frank Sinatra, Harry Truman, and John Steinbeck. In 1954 Murrow asked to interview the Benson family. When Ezra mentioned the invitation to Flora, she strongly opposed the idea. She felt their children had been exposed too often to the public eye. Ezra initially agreed and dropped it. Their son Reed, though, was a returned missionary and college student who believed appearing on the show was an opportunity the family should not pass up. He suggested they could model a family home evening and emphasize the importance of family unity, prayers, and recreation. For a time, Flora remained opposed, stating, “If you insist on the show, have it down at your office. Leave the children out of it.” Nevertheless, Reed persisted. He felt that his family could model a good American home life on prime-time television. Eventually, Flora not only agreed to the program but also put her energy into making the experience something special. Arrangements were made to record and air the program on Friday, 24 September 1954. Recalling the experience later, Ezra remembered, “Not only the family but, to a great extent, the Church would be on trial before the people.”[67] On the day of the broadcast, the family prayed and fasted that everything would run smoothly and that they would represent the Church appropriately. Ezra reported,

The show itself went off very satisfactorily. We ran through it once in a general way beforehand for timing; otherwise, there was no rehearsal. The children seemed very relaxed and Flora did an excellent job in talking about home and family. The girls’ quartet sang, Barbara did a solo with Beverly at the piano and little Beth tap-danced. To make her tapping audible, we took my desk chair mat from my study. Reed and Mark explained our missionary work and Church program. We felt good when it was over, grateful to have had the opportunity.[68]

After the show, Murrow called Ezra from his offices in New York, letting him know that it was the best show he had ever done. Later, the United Press reported that Murrow’s Person to Person program featuring the Bensons brought in more fan mail than any other show. Hundreds of letters also flowed into the Department of Agriculture and to the Benson home from across the country—from parents, clergy members, corporate personnel, and even children. The letters were positive and encouraging, leading President Eisenhower to say, “Ezra, besides all the rest of it, it was the best political show you could have put on.”[69]

Perhaps President Eisenhower felt the conservative Christian values and the strong family ties the Bensons demonstrated were something our country needed to see and hear. Biographer Sheri L. Dew concluded, “The Murrow show brought the Bensons in front and center as spokesman for conservative religious thought.”[70] Years later, President Thomas S. Monson remembered, “The entire Church found justifiable pride in the Edward R. Murrow telecast which featured the Ezra Taft Benson family at home. . . . America was starved to see a righteous family learning and living as a family should.”[71] The Benson family had represented the Church and their family with dignity. Many people were positively influenced by their strong family values, unity, and love.

The Bensons continued their work of influencing many others throughout their time in Washington, DC. No matter where Elder Benson traveled, he was an ambassador of the gospel of Jesus Christ. Gibbons noted that Elder Benson’s influence stretched far and wide:

While in Washington, President Benson made hundreds of contacts, including contacts with foreign heads of state, which would ultimately be of great help to the Church in years to come. President Benson was aware of his influence, and he used it carefully for the blessing of the work. He knew that politics and influence could open doors for the Church. . . . He was a celebrity, both in and out of the Church, and he knew very well how to make good use of his celebrity. He seemed determined to use his experiences and status as a former Cabinet member for the good of the Church. For example, he was always ready to use that card to open doors to people of significance who might help the cause of the Church.[72]

As secretary of agriculture, Ezra Taft Benson made the cover of Time magazine twice, and his photograph appeared on the front covers of some of the most prolific news publications in the country, such as U.S. News & World Report, Newsweek, and the New York Times Magazine.[73] Even though Ezra Taft Benson was hounded and ridiculed, he did not react to the jeers. By the end of the Eisenhower administration, Ezra had become one of the most respected men in the cabinet. As the Washington Star reported, “Benson is regarded as the strongest member of the White House’s inner circle. Undoubtedly, he is the most respected.”[74] Columnist Rosco Drummond wrote, “Mr. Benson has emerged as the most influential member of the Eisenhower Cabinet, as the most secure figure in the Eisenhower administration.”[75] Noted radio broadcaster Paul Harvey concluded, “Ezra Benson is a rare man in politics, thoroughly sincere, uncompromising, and above all, a good man.”[76] Reed wrote that his father’s “fine example and principled stand in a very controversial political role resulted in widespread favorable media coverage. That coverage blessed the Church as well as the nation and had worldwide ramifications for good. His influence touched the lives of many he met, including the heads of state, and prepared a way for missionary work on a broad scale.”[77]

Ezra and his family had a profound influence on not only the individuals and families in their social circles, wards, branches, and neighborhoods but also on the elite of Washington, DC. Very few families, in or out of the Church, have been scrutinized like the Bensons. Even fewer families have had such a positive and lasting influence on those who knew them. Never has a Latter-day Saint been more influential on an American president than Ezra Taft Benson was on Dwight D. Eisenhower. Both men shared faith in God, love for family, and loyalty to the United States of America. As a presidential aide summarized, “The Boss [President Eisenhower] and Ezra have the same ability to stand up to an answer dictated by conscience and faith; no other men in the Cabinet are their equals in that respect.”[78]

Notes

[1] Ezra Taft Benson, God, Family, Country: Our Three Great Loyalties (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1974), 186.

[2] Ezra Taft Benson, Teachings of Ezra Taft Benson (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1988), 489.

[3] Benson, Teachings of Ezra Taft Benson, 489.

[4] Francis M. Gibbons, Ezra Taft Benson: Statesman, Patriot, Prophet of God (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1996), 102–4.

[5] Ezra only lacked a few months to complete his doctorate, but the University of Idaho—his employer—denied him adequate leave of absence to complete his degree.

[6] Sheri L. Dew, Ezra Taft Benson: A Biography (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1987), 123.

[7] Oral History, Ezra Taft Benson, Part 1, 13, Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

[8] Lydia Clawson Hoopes, “Ezra Taft Benson of the Council of the Twelve,” Improvement Era, October 1943, 635.

[9] Jay Richter, “Benson: Prayer, Persuasion, and Parity,” New York Times, 14 June 1953, 58.

[10] Ezra Taft Benson, Ezra Taft Benson Remembers the Joy of Christmas (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1988), 8.

[11] Oral History, Ezra Taft Benson, Part 1, 13, Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

[12] Jerry P. Cahill, President Ezra Taft Benson: A Biographical Sketch, UA 5395, Series 2, Subseries 5, carton 19, folder 1, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT.

[13] Reverend Edward Everett, pastor of the Brattle Street Unitarian Church in Boston, was secretary of state under President Millard Fillmore from 1852 to 1853. Elder Benson surmised, “So far as I know, Dr. Everett and I are the only clergymen ever to serve in presidential Cabinets.” Quoted in Ezra Taft Benson, Cross Fire: The Eight Years with Eisenhower (Garden City, NY: Doubleday & Company, 1962), 346.

[14] David W. Evans, “Ezra Taft Benson—Agricultural Statesman,” Improvement Era, January 1953, 28.

[15] Evans, Improvement Era, “Agricultural Statesman,” 28.

[16] As cited in Evans, “Agricultural Statesman,” 28.

[17] Reed A. Benson, “Ezra Taft Benson: The Eisenhower Years,” in Out of Obscurity: The LDS Church in the Twentieth Century (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2000), 54.

[18] Wesley McCune, Ezra Taft Benson: Man with a Mission (Washington, DC: Public Affairs Press, 1958), 13.

[19] “Apostle at Work,” Time, 13 April 1953, 27.

[20] Dew, Ezra Taft Benson, 258.

[21] Ezra Taft Benson, “The L.D.S. Church and Politics,” as cited in Reed A. Benson, . . . So Shall Ye Reap (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1960), 234.

[22] “Bravo, Cousin Ezra! He Promises a Sane New Day for Agriculture,” Barron’s National Business and Financial Weekly, 16 February 1953, 1.

[23] “Mr. Benson Called the Turn on the ‘Farm Vote,” Saturday Evening Post, 8 January 1955, 10.

[24] Gibbons, Ezra Taft Benson, 186.

[25] Dew, Ezra Taft Benson, 259.

[26] Reed A. Benson, “Eisenhower Years,” 55.

[27] Gary James Bergera, “‘Rising Above Principle’: Ezra Taft Benson as U.S. Secretary of Agriculture, 1953–1961, Part 1,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 41, no. 3 (2008): 88.

[28] Edward L. Schapsmeier and Frederick H. Schapsmeier, “Eisenhower and Ezra Taft Benson: Farm Policy in the 1950s,” Agricultural History 44, no. 4 (October 1970): 371.

[29] Benson, Cross Fire, 53.

[30] Schapsmeier and Schapsmeier, “Farm Policy,” 371.

[31] “Apostle at Work,” Time, 13 April 1953, 25–28; see also Dew, Ezra Taft Benson, 272.

[32] Patrick Q. Mason, “The Historic Conflicts of Our Time: Ezra Taft Benson and Twentieth-Century Media Representations of Latter-day Saints,” in Contingent Citizens: Shifting Perceptions of Latter-day Saints in American Political Culture (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2020), 208–9.

[33] Mason, “Historic Conflicts of Our Time,” 209.

[34] Benson, God, Family, Country, 300.

[35] Ezra Taft Benson, “Concerning Principles and Standards” (BYU commencement address, 4 June 1947), Church News, 14 June 1947, 5.

[36] As cited in Bergera, “‘Rising Above Principle,’” 86.

[37] Elder Ezra Taft Benson, “A Witness and a Warning,” Ensign, November 1979, 32.

[38] “Ezra Taft Benson—He Beat the Farm Bloc,” U.S. News & World Report, 27 April 1956, 74.

[39] Ezra Taft Benson, “Farmers Can Prosper and Be Free,” Nation’s Business, January 1956, 1, 39, 44.

[40] Bergera, “‘Rising Above Principle,’” 94, as cited in Benson, “America: A Choice Land” (an address to the National Conference of Christians and Jews, May 11, 1953), 14, copy in Ernest L. Wilkinson Papers, Perry Special Collections.

[41] Ezra Taft Benson, “Farmers Can Prosper and Be Free,” Nation’s Business, January 1956, 39.

[42] Schapsmeier and Schapsmeier, “Farm Policy,” 370.

[43] Oral History, 21.

[44] Bergera, “‘Rising Above Principle,’” 93.

[45] “Benson Baiters,” Time, 4 November 1957, 18.

[46] Schapsmeier and Schapsmeier, 377.

[47] “Ezra & the Farm Vote,” Time, 3 March 1958, 13.

[48] Schapsmeier and Schapsmeier, “Farm Policy,” 377.

[49] Norman J. Ornstein, “Echoes of Benson’s and Ike’s Farm Debacle,” Christian Science Monitor, March 11, 1985, 14.

[50] “Benson Declares He Won’t Resign,” New York Times, 15 December 1959, 1, 44.

[51] “Benson to Remain in Post Remainder of Ike Term,” Salt Lake Tribune, 9 February 1959, 3.

[52] Benson, Cross Fire, 328.

[53] In 1957 Ezra was ready to quit again. The pressure was strong for him to resign. He told President Eisenhower that maybe it would be better if he stepped down. Eisenhower stated, “If I have to, I’ll go to Salt Lake City and appeal to President McKay to have you stay on with me.” Benson, Cross Fire, 221, 359.

[54] “Ezra Taft Benson—He Beat the Farm Bloc,” 77.

[55] Francis M. Gibbons, Remembering Seven Prophets: Ezra Taft Benson (Holladay, UT: Sixteen Stones Press, 2015), 63.

[56] Dew, Ezra Taft Benson, 292.

[57] “President Ezra Taft Benson: A Faithful Servant,” New Era, January 1986, 7.

[58] Mason, “Historic Conflicts of Our Time,” 214.

[59] Benson, God, Family, Country, 175.

[60] Derin Head Rodriguez, “Flora Amussen Benson: Handmaiden of the Lord, Helpmeet of a Prophet, Mother in Zion,” Ensign, March 1987, 18.

[61] Benson, Cross Fire, 199.

[62] Benson, Cross Fire, 199.

[63] Rodriguez, “Flora Amussen Benson,” 18.

[64] Rodriguez, “Flora Amussen Benson,” 19. For one such example, see Benson, Cross Fire, 200–201.

[65] Ezra Taft Benson, “Benson Family Papers, 1954–1957,” Church History Library.

[66] “Eisenhowers for Family Home Evening,” Church News, 12 February 1955, 6.

[67] Benson, God, Family, Country, 176.

[68] Benson, Cross Fire, 215.

[69] Benson, Cross Fire, 215.

[70] Dew, Ezra Taft Benson, 299.

[71] R. Scott Lloyd, “Happy Birthday: Televised Tribute Celebrates Rich Life of Service,” Church News, 5 August 1989, 3.

[72] Gibbons, Remembering Seven Prophets, 42–44.

[73] Reed A. Benson, “Eisenhower Years,” 56–57.

[74] McCune, Ezra Taft Benson, 81–82.

[75] Benson, Cross Fire, 405.

[76] Dew, Ezra Taft Benson, 295–96, 528.

[77] Reed A. Benson, “Eisenhower Years,” 54.

[78] Benson, Cross Fire, 317.