At the Crossroads: T. H. Bell’s Role in the Reagan Administration

Roger G. Christensen

Roger G. Christensen, “At the Crossroads: T. H. Bell's Role in the Reagan Administration,” in Latter-day Saints in Washington, DC: History, People, and Places, ed. Kenneth L. Alford, Lloyd D. Newell, and Alexander L. Baugh (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book), 283‒302.

Roger G. Christensen was an instructor of Church history and doctrine at Brigham Young University when this was published. Dr. Christensen worked for several years as assistant to the commissioner of the Church Educational System and as the secretary to the Church Board of Education and the Boards of Trustees of BYU, BYU–Hawaii, BYU–Idaho, and LDS Business College.

The United States Capitol, photo by Caleb Perez, Unsplash.

The United States Capitol, photo by Caleb Perez, Unsplash.

Several members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints have served in various governmental roles in the United States, both as elected and appointed officials. Only six have served as cabinet officers, officials who directly advise the president on important issues of the day. T. H. Bell, a devout Latter-day Saint, served as secretary of education during the first four years (1981–85) of the Reagan administration. His appointment to serve came at a critical time in the early history of the Department of Education. This brief narrative account provides a case in contrast between Bell, a lifelong educator and administrator who focused on improving education, and the president and his advisers, who wanted to eliminate the department. It also illustrates how politics both helped and hindered Bell’s efforts.

Roads to Washington

Terrel Howard Bell was born 11 November 1921 in Lava Hot Springs, Idaho, the eighth of twelve children born to Willard D. and Alta Martin Bell.[1] His father passed away shortly after Bell’s eighth birthday. As a result, he grew up in very humble circumstances during the Great Depression and saw education as his passport to the future.[2] After completing high school in his hometown, Bell attended Albion State Normal School, a small teachers college in Albion, Idaho.[3] World War II interrupted his education as he spent three and a half years serving in the Marine Corps, but he returned to Albion and completed a BA degree in 1946. He later received an MA (1954) from the University of Idaho and a PhD (1961) from the University of Utah.[4] He married Josephine Saunders in 1950. Their son, Jon, died in infancy, and they divorced in 1956. He later married Betty Ruth Fitzgerald on 1 August 1957. Together they had four sons.[5]

During his career as an educator, Bell worked as a coach, teacher, and professor at the secondary and postsecondary levels in Idaho, Wyoming, and Utah. He also served in various administrative positions at the district, state, and national levels; he was the commissioner of higher education for the state of Utah at the time of his appointment as U.S. secretary of education.[6] Bell noted that the basic tenets of his faith he had learned in his youth—hard work and self-sufficiency—influenced all aspects of his life, both personally and professionally.[7]

Ecclesiastically, Bell served much of his adult life teaching and working to improve teaching at the ward, stake, and general Church levels, serving on the Sunday School general board from 1972 to 1974. He was the Gospel Doctrine teacher of the Falls Church Ward while serving as secretary of education. Upon returning to Utah after his service in Washington, he served as a high councilor, stake president, and regional representative of the Twelve.[8]

Before his appointment as secretary of education, Bell had served in Washington on two previous occasions: first as associate commissioner (1970–71) in the Office of Education—a division of the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (HEW)—under Richard Nixon and later as the commissioner (1974–76) under Gerald Ford. While serving as commissioner, Bell reported to Caspar Weinberger, secretary of HEW at that time. These two men got along well and respected one another.[9] Weinberger spent more than three decades in various political roles, including chair of the California Republican Party from 1962 to 1968. He was well-known by Reagan and served as secretary of defense during most of the Reagan administration.[10] Bell believed that it was Weinberger who recommended him to Reagan for consideration as secretary of education.[11]

During his early years in Washington, members of Congress and others within the administration recognized Bell for the keen administrative abilities and tact he exhibited when he addressed many challenging educational issues.[12] In his role as commissioner of education, he testified before Congress in support of creating a cabinet-level department for education.[13] Congress passed the act creating the U.S. Department of Education during the Carter administration, and it officially began operation in November 1979.[14] The department was the thirteenth cabinet office created and, as Bell noted, since the number thirteen is a notoriously unlucky number, its concerns and issues would indeed be last on the list for the Reagan administration’s consideration.[15]

Ronald Reagan emerged as a political leader in the state of California. He was elected president of the United States on 4 November 1980 after serving as governor of that state from 1967 to 1975. His tenure as governor shaped his views on educational institutions and their leaders based, in part, on the turbulent circumstances of the times. Through the 1960s and extending into the early 1970s, negative reactions to U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War exploded across a number of university campuses.[16] The seedbed of discontent in California germinated at the University of California at Berkeley.[17] By the mid-1960s, however, the attitude of the public had not yet coalesced with that of the students. Many citizens were appalled at what was taking place in Berkeley (and later, on other campuses) and wanted leaders to put an end to the protests.[18]

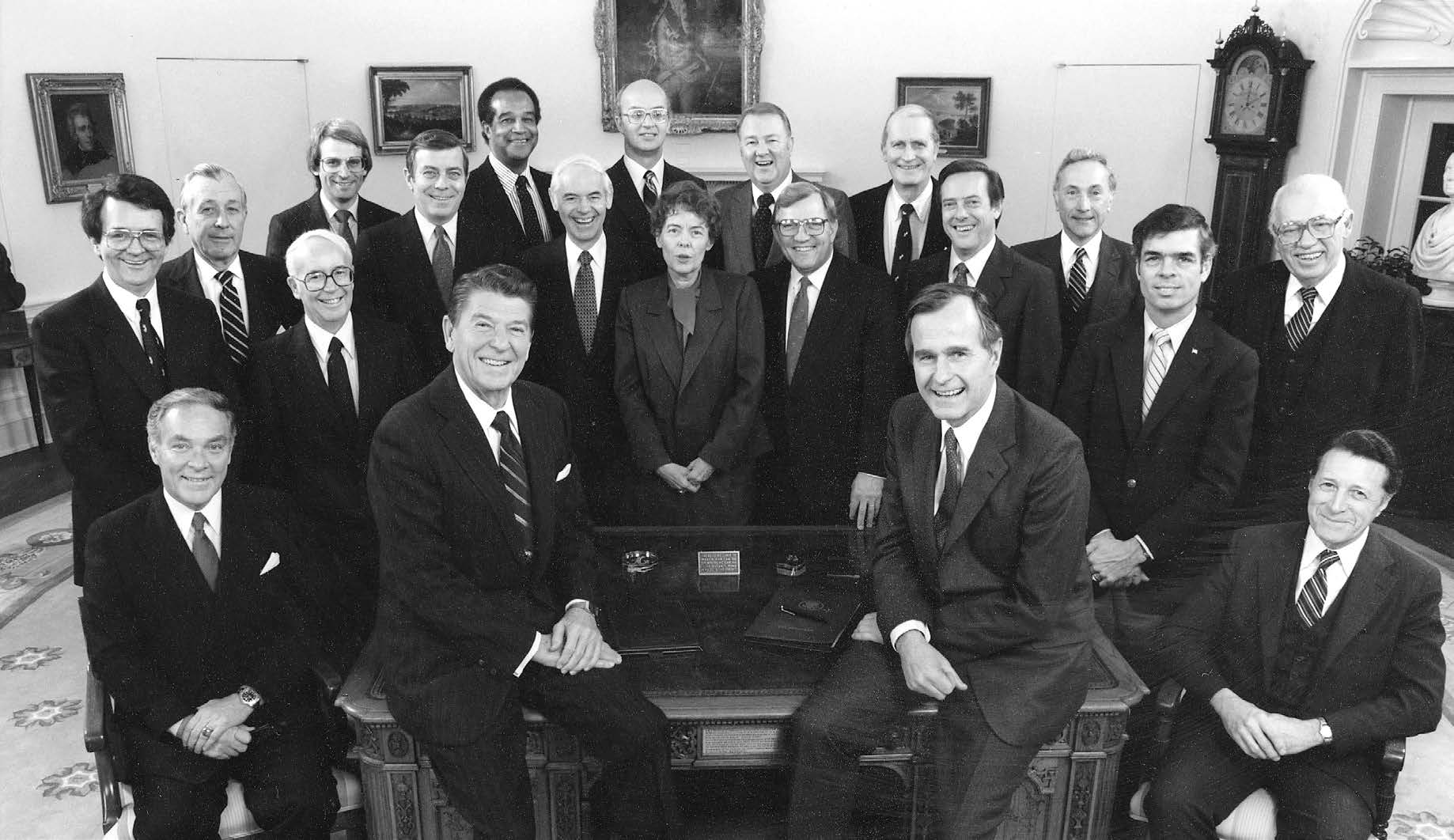

Reagan’s first official cabinet photo in the Oval Office, 1981. Ronald Reagan Presidential Library.

Reagan’s first official cabinet photo in the Oval Office, 1981. Ronald Reagan Presidential Library.

One of Reagan’s political strengths was his ability to assess popular sentiment, and he tapped into the anti-protest attitude in order to criticize educational institutions, administrators, faculty, and students for allowing the protests to occur.[19] His political mantra became, “It is time to clean up the mess at Berkeley.”[20] Many believe he launched his political career based on his harsh criticism of higher education and, in particular, educational leaders.[21] He campaigned for governor on the platform of fiscal responsibility, limited government, welfare reform, and cracking down on student protests.[22] When Reagan won the nomination for the presidency, prominent planks in the Republican Party platform included similar themes: reduce taxes, limit government with corresponding reductions in federal spending, and eliminate the Department of Education.[23]

The stage was set for a political clash between the president-elect and his eventual nominee for secretary of education. Bell was officially nominated to become the U.S. secretary of education on 20 January 1981 by President Reagan and confirmed two days later by the U.S. Senate’s vote of 90–2.[24]

Rough Roads Ahead

During the vetting process for his nomination as secretary of education, Bell met with members of the transition team, including Edwin Meese and his longtime friend Pendleton James. Meese served with Reagan during his years as governor of California (1967–75) and throughout his presidency, first as special counselor (1981–85) and then as attorney general (1985–88).[25] Meese knew well the president-elect’s disdain for big government and educational institutions, including their leaders. He also was a leader of the “movement conservatives,” a group that felt empowered to implement the president’s agenda. James, president of an executive search firm, ultimately became director of the White House Personnel Office, which oversees hiring within departments of the administration, including the Department of Education. Both of these men proved to be antagonists in Bell’s later efforts regarding the future of the department.[26]

The initial meeting focused on Bell’s willingness to work toward eliminating the department. Pendleton James noted that, if appointed, Bell would have the distinction one day of walking into the Oval Office and stating, “Well, we’ve shut the abominable thing down. Here’s one useless government agency out of the way.”[27] The comment clearly expressed the environment and, presumably, the position Bell would assume if he accepted the nomination. Still, he felt he could make a difference in the national discourse around education and expressed his willingness to serve.[28]

Recruiting people to assume leadership positions in the department, however, became an arduous task due to the administration’s stated objective. The most qualified and likely candidates declined being considered. Bell initially had to appoint temporary leaders into crucial positions from among the ranks of career civil service employees.[29] Key senior individuals in the administration—particularly Ed Meese, Pendleton James, and David Stockman, director of the Office of Management and Budget (OMB)—became central in all discussions Secretary Bell had regarding the administration of the department. Any actions having an impact on budgets or hiring of personnel had to be coordinated with these men, all of whom were movement conservatives and were firmly committed to abolishing the department.[30]

Fortunately, the president had assured his cabinet that they did not need to employ people in senior staff positions that they were not comfortable working with, which essentially gave each cabinet officer veto power over political appointees.[31] Bell used this delegated authority effectively, but it repeatedly created an impasse with White House staff in obtaining approval for his proposed candidates. For example, White House Personnel initially proposed that Bell consider Loralee Kinder to be the undersecretary of education. She had chaired a national educational task force and had high regard among the movement conservatives. Bell disagreed with many of the proposals of the task force and additionally felt that Kinder lacked the academic credentials to command the necessary respect within the academic community. Bell proposed Christopher Cross, a Republican educator, who was also a respected scholar. White House Personnel quickly rejected this recommendation, still angered over Bell’s veto of Ms. Kinder.[32]

After extended (and at times contentious) negotiations, Bell secured a leadership team he could work with.[33] He noted, “It had been a rocky start, but I finally proved to my White House adversaries that I would not be intimidated or dominated. . . . I didn’t win, but most importantly, I didn’t lose either. . . . I had succeeded in assembling a staff that was a balance between moderates and ideologues, making it possible for me to have credibility in the education community as well as to do my job.”[34]

At the Crossroads

Bell developed a level of credibility with educators, legislators, and the media while he navigated appointees through the approval process and some initial administrative actions he had taken regarding bilingual education and merit pay for teachers. In July 1981, U.S. News & World Report published an appraisal of the effectiveness of the Reagan cabinet based on a survey of 131 “Washington insiders”—White House administrators, Senators, members of Congress, key lobbyists, and others. Bell ranked fifth out of the thirteen cabinet secretaries. The article noted, “The ultimate surprise would be if Bell’s Education Department, which has been slated for eventual elimination in Reagan’s drive to trim the bureaucracy, escapes the ax—something that now seems a distinct possibility.” He hoped to leverage his newfound standing to develop a measured proposal about the department’s future.

Although he was determined to keep his commitment to the president, he also saw a need to maintain some role for the federal government in education, especially regarding “vital college-student-aid funding from loans, work-study opportunities, and grants to financially needy students.”[35] In addition, he had regulatory obligations for other substantial programs, such as Title I funding for schools with large concentrations of low-income and educationally disadvantaged students, and enforcement of civil rights required by the education acts passed in the 1960s and 1970s. These matters weighed heavily on Secretary Bell, and he knew disrupting existing systems could be problematic if he didn’t consider the long-term impact of any proposed changes. He needed time to assess the areas of greatest need in education across the country and how the department could best meet those needs.

Bell understood the impact of a timely message, one that could capture the attention of organizations and policy makers, as evidenced by the 1910 Flexner Report addressing the poor quality of medical education at that time in the United States and Canada.[36] He sensed the time was right for a landmark statement on the overall state of education in the United States, which could then inform long-term policy decisions (including recommendations on the department’s future) and help define the role of the federal government in education.[37]

Bell discussed the idea of a presidential commission to study education with senior White House staff. His proposal met resistance from Ed Meese and other movement conservatives.[38] He therefore decided to move forward on his own and appointed a blue-ribbon commission to undertake a national study. He and his staff found qualified individuals to serve as members of the commission who would represent a broad spectrum of educational interests.[39]

The National Commission on Excellence in Education was formally organized by a charter Secretary Bell signed on 5 August 1981.[40] The charter included multiple responsibilities: (1) evaluating and synthesizing data and scholarly literature on the quality of teaching and learning across the country for all levels of education and types of educational institutions; (2) analyzing curriculum, academic standards, college admissions requirements, and student performance; (3) identifying educational programs that consistently attained higher than average results; (4) comparing academic requirements and outcomes for schools in the United States with those of other economically advanced countries; and (5) assessing major changes that had significantly affected educational achievement over the previous twenty-five-year period.[41] The commission also was to hold hearings to gather insights from experts and the public on perceived issues or concerns at all levels of education. It was then to provide a report defining issues and providing practical recommendations to help those serving in a capacity to influence change including parents, educators, governing boards, and local, state, and federal officials.[42]

Bell held a public orientation meeting to initiate the study and outline its objectives. Members of the media attended the session, which helped it garner national attention. He assured the commission that the department’s support and resources would be available to it so that the tasks could be completed without interference. Bell also committed to holding a series of conferences across the country following receipt of the report in order to disseminate its findings, and he indicated that he would do all he could to get the president involved in those public meetings. In addition, Bell emphasized the importance of having the work of the commission be of the highest quality and insisted that any proposed recommendations be unanimous.[43]

The commission held a total of seventeen public meetings, panel discussions, hearings, and symposia in varying locations across the country. In addition, the commission solicited written papers on topics of concern from individuals who were experts in their respective fields.[44] Bell met with the commission on several occasions during the process in order to respond to questions and to offer encouragement.[45] As the deadline for submitting the report approached, Bell became concerned when the chair, David Gardner, called and requested an extension. Bell regarded Gardner highly and had previously worked closely with him when Gardner served as president of the University of Utah; he also knew they had a narrow window in which to get the report to the president if they hoped to have his involvement in any of the public meetings prior to the 1984 election season. Bell pressed hard, but Gardner was firm about needing the additional time to achieve full consensus of all eighteen members on all the recommendations. Bell relented and received the final report from the commission in April 1983.[46]

The report, entitled A Nation at Risk: An Imperative for Educational Reform, was direct, impassioned, and relatively short (only thirty-six pages long, not counting the appendices). The opening paragraph summarized the commission’s concerns. It states, “Our Nation is at risk. Our once unchallenged preeminence in commerce, industry, science, and technology innovation is being overtaken by competitors throughout the world. . . . The educational foundations of our society are presently being eroded by a rising tide of mediocrity that threatens our very future as a Nation and as a people.”[47] Additionally, the report presented the study’s process, findings, recommendations, and its call to action. The summary comments were similarly poignant. The report concluded, “Reform of our educational system will take time and unwavering commitment. It will require equally widespread, energetic, and dedicated action . . . from groups with interest in and responsibility for educational reform.”[48]

Secretary Bell was both pleased with and apprehensive about the commission’s report. The day after receiving it, he transmitted a copy to the president, and it circulated among the White House staff. Within hours, Bell received calls from many who had read the report, and they commended the work. He was told that the president had also read the entire report and was pleased with it.[49]

Reagan’s remarks on receiving the final report of the National Commission on Excellence in Education, 26 April 1983. T. H. Bell, David P. Gardner (chair of the commission), and President Reagan. Ronald Reagan Presidential Library.

Reagan’s remarks on receiving the final report of the National Commission on Excellence in Education, 26 April 1983. T. H. Bell, David P. Gardner (chair of the commission), and President Reagan. Ronald Reagan Presidential Library.

Bell arranged to make the report public at a White House media event on 26 April 1983, where the president would receive an official copy.[50] The day before the meeting, Bell received an urgent call from a White House staffer who had seen a draft of the president’s planned remarks and expressed concern about the tenor of his message. It said little about the work of the commission or of its report; the focus was on some key issues championed by the movement conservatives regarding education—tuition tax credits and school prayer. Bell immediately called the president’s chief of staff, James Baker, to see if anything could be done to tailor the message appropriately. Baker assured Secretary Bell that the extraneous or irrelevant comments would be removed from the president’s prepared notes.

On the morning of the press conference, emotions ran high. Everything was proceeding as planned, and the White House briefing room was packed—the back of the room was crowded with television cameras, invited guests occupied every available chair, and members of the commission sat up front. Bell welcomed everyone, gave a brief overview of the purpose of the work of the commission and invited the chair, David Gardner, to explain more about the process. Gardner delivered his comments and turned the microphone back to Bell. The president did not arrive as scheduled, so Bell continued making additional comments to fill the void. He tried to be positive, but it became apparent to everyone in the crowd that he was just buying time.[51]

When President Reagan finally entered the room, Bell turned over the podium to him. The president apologized for being late, pulled his note cards from his pocket, and started his remarks as prepared by his staff. Reagan waxed eloquent about aspects of the report, noting, “You have found that our educational system is in the grip of a crisis caused by low standards, lack of purpose, ineffective use of resources, and a failure to challenge students to push performance to the boundaries of individual ability.” He continued, “We’re entering a new era, and education holds the key. Rather than fear our future, let us embrace it and make it work for us by improving instruction.” He then moved on to address the importance of school prayer as a fundamental freedom, the importance of competition and choice in education, and the value of tuition tax credits in accomplishing these aims. He also emphasized the need to abolish the department.[52]

Bell was stunned. These latter themes were the points he had hoped to excise from the president’s comments. Although Bell did not take exception to most of these concepts in principle, this was not the proper setting for expressing these issues. As the president spoke, Bell looked down the corridor where Reagan had entered and saw Ed Meese and others of the movement conservatives smiling and giving congratulatory gestures to one another.[53]

Bell worried about how the press would treat the meeting and the report of the commission. Despite his worst fears, the president’s peripheral comments fell flat with journalists covering the event; because everyone in the audience had received a copy of A Nation at Risk in advance, most news reports covered the content of the report, not the press conference related to its release.[54]

The importance of educational reform was now in the national spotlight. Nearly every broadcast media outlet and every newspaper across the country reported on the findings presented in A Nation at Risk. Secretary Bell became a popular interviewee on all the national news shows, and on the Sunday morning programs of Meet the Press and Face the Nation. Requests for copies of A Nation at Risk caused the U.S. Government Printing Office to run out of stock, and there were requests on backorder for months. Follow-up reports in the media kept the recommendations from the commission’s report before the public for many days after its initial release.[55]

Cabinet meeting, 23 February 1984. T. H. Bell, President Reagan, John A. Svahn (director, White House Office of Policy Development). Associated Press.

Cabinet meeting, 23 February 1984. T. H. Bell, President Reagan, John A. Svahn (director, White House Office of Policy Development). Associated Press.

The issues raised in A Nation at Risk struck a national nerve. It became clear that addressing educational reform was high on the public agenda. This visibility given to the department also became a turning point on how it was perceived, for a time, within the administration. In a subsequent cabinet meeting to address budget proposals for the following fiscal year, David Stockman, director of OMB, emphasized the importance of reducing expenditures in each department with one notable concession: “The sensitive issue of education is an exception, of course. We will want to keep in front on this.”[56] As a result, the department did not experience large budget cuts that year.

Bell had committed to organizing public dissemination meetings following the release of the commission’s report. He coordinated twelve conferences in strategic areas around the country. Most members of the commission participated in these meetings, as did Secretary Bell. President Reagan also committed to help disseminate the findings of the report, and based on the national mood, it provided opportunities to address topics of importance during the pre-election season.[57] Reagan’s involvement also gave greater visibility to the events and assured continuing media coverage.

In these public meetings, President Reagan assured the people that he was working on plans to resolve the educational crisis. He was also involved in some of the question-and-answer sessions. However, in one question directed specifically to Reagan, “What was your rationale for wanting to abolish the Department of Education?” he was a bit awkward in his reply. He spoke of his keen interest in and support of education; however, he feared the federal government would take a stronger role in controlling education across the country if not carefully kept in check. Later, Reagan asked Secretary Bell, “Did I handle the question on the future of the Department of Education okay?” Given Reagan’s prior commitment to abolish the Department and the current public interest in improving education, Bell concluded, “The question of abolishing the department of Education was an exercise in futility. He and I both knew that it would never happen.”[58]

Moving Down the Road

Aligning with public sentiment, the tone of the Reagan administration toward education changed dramatically. In stark contrast to the wording of the 1980 Republican Party platform, the 1984 platform extolled President Reagan’s leadership in shaping the national agenda on education. In part it read, “The Reagan Administration turned the nation’s attention to the quality of education. . . . Ronald Reagan’s significant and innovative leadership has encouraged and sustained the reform movement. He catapulted education to the forefront of the national agenda.”[59] After much positive public attention, the president sent a personal note to Secretary Bell, praising him for his leadership in shaping the future of education in the country.[60]

Although pleased with what seemed to be a strong endorsement from the president, that support was short-lived. Bell soon realized the president’s real interests were not in educational reform at all. It became apparent that the president was using the present enthusiasm for change in education to his political advantage.[61] He and many of his advisers leveraged the focus brought by the attention on education to advance other policy issues within their own political agendas. After winning a landslide election in 1984, Reagan quickly moved on to other pressing issues. All of the traction gained around education quickly dissipated, and education reform again became a low priority. Those who had pushed for abolishing the department once again had the president’s ear.

Confidential proposals Bell sent to the White House to address educational reform were leaked to the press and received unfavorable commentary in several conservative publications. Bell learned that Ed Meese and others among the movement conservatives had requested advanced copies of his proposals and were likely the source of these leaks. In a subsequent meeting to address budget requests, Bell confronted Meese and David Stockman directly. Both denied any knowledge of how the information became public. Although Bell continued to push his agenda on educational reform, senior White House staff repeatedly rebuffed his efforts; moving proposals on educational issues through the internal political process regularly stalled. Bell realized his effectiveness as secretary was compromised. As a result, he chose to resign from office to return to Utah, where he hoped to have an impact in formulating improvements in education at the state and local levels.[62]

Back in Utah, Bell received a professorship in the College of Education at the University of Utah and began teaching again.[63] According to a business associate, Bell loathed the idea of retiring, so in 1991 he also founded an educational consulting firm—T. H. Bell and Associates—and continued his advocacy for improving education across the nation.[64] During this time, Bell also served as a regional representative of the Twelve for two years (1990–92). He was released from that role in March 1992 to chair a special coalition against a proposed ballot initiative in Utah to legalize pari-mutuel betting.[65] T. H. Bell died on 22 June 1996 of pulmonary fibrosis at the age of seventy-four.[66]

At the End of the Road

As noted in A Nation at Risk, educational reform takes time and unwavering commitment. Without a consistent long-term policy, many issues raised in 1983 regarding education in America have persisted. Reflecting on his career, Bell lamented, “We would have changed the course of history in American education had the president stayed with us through the implementation of the school reform effort.”[67] Although Bell was not successful in achieving the objectives he had hoped to realize, the immediate impact of his blue-ribbon report was extensive, and some positive steps were initiated. He helped set the tone for a national conversation, and he demonstrated the need for partnered efforts to raise the quality of education for every student.

Although T. H. Bell was tasked with abolishing the department, his background, vision, and role at a critical time allowed him to highlight national concerns about education and to elevate the image of the department in the eyes of many, especially in the eyes of the public. His leadership effectively saved the department from elimination. At that critical moment in history, he stood at the crossroads and helped influence the future direction that the U.S. Department of Education would take.

I chose to research the role of T. H. Bell because of a personal relationship I had with him. Bell served as secretary of education from 1981 to 1985 in the first Reagan administration. Shortly after returning to Utah from Washington, he was called as a regional representative of the Twelve. In 1990, while I was serving as a young counselor in a stake presidency, Elder Bell was assigned to work with the stakes in our area. During the time he met with our stake presidency, he started every meeting by sharing a political anecdote (generally humorous) about his experiences while serving in Washington. I also grew up in Northern California, near the University of California, Berkley, during the years Reagan served as governor of that state.

Notes

[1] Terrel Howard Bell, FamilySearch.org.

[2] Terrel H. Bell, The Thirteenth Man: A Reagan Cabinet Memoir (New York: The Free Press, 1988), 6–8.

[3] Bell, Thirteenth Man, 8–12.

[4] Ronald Reagan, “Nomination of Terrel H. Bell to Be Secretary of Education,” 20 January 1981, The American Presidency Project (website).

[5] Bell, FamilySearch.org.

[6] Reagan, “Nomination of Terrel H. Bell to Be Secretary of Education.”

[7] Bell, Thirteenth Man, 7–8.

[8] Terrel H. Bell, biographical information provided to the Church History Department, 1990.

[9] Bell, Thirteenth Man, 1–2.

[10] Caspar W. Weinberger, “Biographical Information,” https://

[11] Bell, Thirteenth Man, 1–2.

[12] Hearing before the Committee on Labor and Public Welfare, United States Senate, Second Session on Terrel H. Bell, PhD, of Utah, to Be Commissioner of Education, 93rd Cong. (1974).

[13] Senator Jennings Randolph, “U.S. Commissioner of Education Leaves Significant Imprint on the Future of Public Education in America” (Congressional Record, 122:94, 30 July 1976), 28419–20.

[14] Department of Education Organization Act of 1979. Pub. L. No. 96-88.

[15] Bell, Thirteenth Man, ix–xi.

[16] E. M. Schreiber, “Opposition to the Vietnam War among American University Students and Faculty,” British Journal of Sociology 24, no. 3 (September 1973), 288–302.

[17] William J. Rorabaugh, Berkeley At War: The 1960s (New York: Oxford University Press, 1989).

[18] Gerard J. De Groot, “Ronald Reagan and Student Unrest in California,” Pacific Historical Review 65, no. 1 (February 1996): 107–29.

[19] Stuart K. Spencer, oral history, interviewed by Gabrielle Morris, 1979, “Developing a Campaign Management Organization” (Regional Oral History Office, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley), 31.

[20] Totton J. Anderson and Eugene C. Lee, “The 1966 Election in California,” Western Political Quarterly 20, no. 2, part 2 (June 1967): 535–54. See also Jeffrey Kahn, “Ronald Reagan’s Political Career and the Berkeley Campus,” UC Berkley News, 8 June 2004.

[21] De Groot, “Ronald Reagan and Student Unrest,” 107–9.

[22] Anderson and Lee, “The 1966 Election in California,” 535–54.

[23] Republican Party Platforms, “Republican Party Platform of 1980,” 15 July 1980, The American Presidency Project (website).

[24] Reagan, “Nomination of Terrel H. Bell to Be Secretary of Education.”

[25] Edwin Meese III, “Biographical Information,” Hoover Institution, Stanford University.

[26] Bell, Thirteenth Man, 38–51.

[27] Bell, Thirteenth Man, 2.

[28] Bell, Thirteenth Man, 3–5.

[29] Bell, Thirteenth Man, 40.

[30] Bell, Thirteenth Man, 39–40, 67.

[31] Bell, Thirteenth Man, 38.

[32] Bell, Thirteenth Man, 40–41.

[33] Bell, Thirteenth Man, 43–51.

[34] Bell, Thirteenth Man, 48–50.

[35] Bell, Thirteenth Man, 90.

[36] The Carnegie Foundation, “Medical Education in the United States and Canada,” A Report to the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, by Abraham Flexner, Bulletin Number Four, 1910. See also Lester F. Goodchild and Harlod S. Wechler, eds., “Professional Education” and “Surveying the Professions,” in The History of Higher Education, 2nd ed., ed. Lester F. Goodchild and Harold S. Weschler (Needham Heights, MA: Association for the Study of Higher Education, 1997), 379–402.

[37] Bell, Thirteenth Man, 115.

[38] Bell, Thirteenth Man, 116.

[39] The National Commission on Excellence in Education was eventually composed of eighteen individuals. For a full list of members of the Commission, see USA Research, A Nation at Risk: The Full Account (Cambridge, MA: Murray Printing Company, 1984), appendix B: Members of the National Commission on Excellence in Education, 91–92.

[40] USA Research, A Nation at Risk, appendix A: Charter: National Commission on Excellence in Education, 87–90.

[41] This timeframe coincided with the period following the Russian launch of Sputnik I, the first artificial satellite, in October 1957 and the subsequent emphasis placed on STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) education across the United States.

[42] USA Research, A Nation at Risk, appendix A: Charter: National Commission on Excellence in Education, 87–90.

[43] Bell, Thirteenth Man, 118–19.

[44] For a full list of meetings, see USA Research, A Nation at Risk, appendix D: Schedule of the Commission’s Public Events, 95–96. For a listing of participants and events at each location, see appendix E: Hearing Participants and Related Activities, 97–109. For a listing of those submitting commentary to the Commission, see appendix F: Other Presentations to the Commission, 111.

[45] Bell, Thirteenth Man, 120.

[46] Bell, Thirteenth Man, 120–22.

[47] USA Research, A Nation at Risk, 5.

[48] USA Research, A Nation at Risk, 84; emphasis added.

[49] Bell, Thirteenth Man, 127.

[50] Bell, Thirteenth Man, 123–31.

[51] Bell, Thirteenth Man, 129–30.

[52] Ronald Reagan, “Remarks on Receiving the Final Report of the National Commission on Excellence in Education,” 26 April 1983, The American Presidency Project (website).

[53] Bell, Thirteenth Man, 130–31.

[54] Bell, Thirteenth Man, 131.

[55] Bell, Thirteenth Man, 131.

[56] Bell, Thirteenth Man, 131.

[57] Bell, Thirteenth Man, 144.

[58] Bell, Thirteenth Man, 148–49. After Bell’s tenure in the department, the lack of a consistent education policy to address the issues initially raised in A Nation at Risk contributed to perceptions of the department’s value in resolving these concerns. As a result, some politicians still question its purpose and the need for an ongoing role of the federal government in education.

[59] Republican Party Platforms, “Republican Party Platform of 1984,” 20 August 1984, The American Presidency Project (website).

[60] Bell, Thirteenth Man, 159.

[61] Bell, Thirteenth Man, 158.

[62] Bell, Thirteenth Man, 157–58.

[63] University of Utah, College of Education, Alumni Profiles, Terrell [sic] Howard Bell.

[64] “Terrel Bell, Known for Defending Federal Role in Education, Dies,” Education Week, 10 July 1996.

[65] “LDS Leaders Attack Pari-Mutuel Betting,” Deseret News, 1 June 1992.

[66] “T. H. Bell, Ex-Cabinet Member and Educator, Dies at 74,” Deseret News, 23 June 1996.

[67] Bell, Thirteenth Man, 159.