Beverly Campbell: Church Public and International Affairs Director

Mary Jane Woodger and Brooke Anderson

Mary Jane Woodger and Brooke Anderson, “Beverly Campbell: Church Public and International Affairs Director,” in Latter-day Saints in Washington, DC: History, People, and Places, ed. Kenneth L. Alford, Lloyd D. Newell, and Alexander L. Baugh (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book), 303‒18.

Mary Jane Woodger was a professor of Church history and doctrine at Brigham Young University when this was published.

Brooke Anderson was a senior majoring in English at Brigham Young University when this was published.

Beverly Campbell in her office. Photos in this chapter courtesy of Thomas Campbell.

Beverly Campbell in her office. Photos in this chapter courtesy of Thomas Campbell.

Beverly Brough Campbell was an extraordinary woman known for her ability to open doors of communication and respect for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Among Latter-day Saint women, none has left a more indelible mark on world affairs than Beverly Campbell. Campbell’s skills and gifts further developed and made a lasting impact on the international relations for the Church. She served as the director of the International Public Affairs Office in Washington, DC (1987–97), and her influence is still seen in Church organizations and the individuals who worked under her leadership.

For twelve years as she served as the director of International Affairs for the Church’s Public and International Affairs Department in Washington, DC, she developed numerous programs and relationships still in place today. When asked how she was able to do all that she did, Campbell responded that she “had been prepared and trained from every step” of her life.[1]

Move to Washington

When Campbell was thirty, she and her husband, Arwell Pierce Campbell, received job offers in New York, Los Angeles, and Chicago for positions in which Campbell felt certain their talents would be used. Despite the promise of these positions, she and her husband instead decided to move to Virginia to capitalize on a job offer for Pierce from a marketing firm. Campbell recalls the impracticality of their decision: “It made no sense. It made no sense at all. We just felt that was where we needed to be.”[2]

Regional Public Affairs Director

In 1984, Campbell was asked to be “the regional public affairs director for the Northeast Region” of the Church.[3] The Department of Public Affairs for the Church was created in 1970 by Spencer W. Kimball, President of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles. In February of that year, President Kimball had met in New York with Church leaders and prominent Latter-day Saint businesspeople to discuss how the Church could respond to attacks and allegations regarding blacks and the priesthood and other issues. The result was the creation of two new departments: the Department of Internal Communications and the Department of Public Communications, later renamed the Department of Public Affairs. The purpose of Public Affairs was to “apprise the public of the policies, aims, and activities of the Church and to respond to questions raised about the Church and to attacks made on it.”[4] The head of the department was located in Salt Lake City with regional directors located in each region of the Church. As regional director of the newly created office in Washington, DC, Campbell was responsible for developing contacts and fostering a “positive and accurate Church presence in the national and international media.”[5] At first Campbell worked with the media in Washington to get stories about the Church into the news, but her work “quickly morphed” into the business of forming international relations.[6]

Pope Jean Paul II with Beverly Campbell in Rome.

Pope Jean Paul II with Beverly Campbell in Rome.

Change came when Campbell realized that “the shotgun approach of trying to reach individuals through media campaigns was less effective than getting accurate and useful information directly into the hands of policy makers in other countries.” She found that because most countries viewed the Church as an American institution, when problems or questions arose concerning the Church in a particular country, government officials would consult their U.S. embassy for further information. The embassy staff, knowing little about the Church firsthand, would turn to the media, “often acquiring negative or misleading information that they did not have the means to adequately evaluate.” Campbell determined that the best means of assuring that the Church was presented accurately would be to develop personal relations with the countries’ ambassadors and provide them with firsthand knowledge. “Thus began the process of establishing personal contacts between ambassadors, prominent Church members in the Washington, DC, area, and the Church leaders responsible for various countries of the world”—a revolutionary approach for the Church.[7]

Initially, the hardest part of this approach was obtaining appointments with ambassadors and other government personnel[8] due to the Church’s minimal ties. Fortunately, Campbell had previously been the director of the Joseph P. Kennedy Jr. Foundation, director of community relations for the Special Olympics, and the Church’s spokesperson on the Equal Rights Amendment. These previous positions provided her opportunities to form ties with many key people in the DC area. “I used members of Congress and senators, and CEOs—whoever I needed to get a door open.”[9]

The Church’s Unofficial Embassy

One approach Campbell employed to form ties with necessary officials was to invite them one at a time to low-key dinners where they would meet well-known Church leaders, businesspeople, politicians, and others at her secluded home on the Potomac River in Virginia. The home was the fifth Campbell had designed and the largest, at 14,000 square feet.[10]

Campbell had begun building the home shortly before receiving her call to the Church Public Affairs Office. While the house was still under construction, Elder Royden G. Derrick of the First Quorum of the Seventy visited the house and told Campbell, “This house is being built for the Lord’s purposes.”[11] In fulfillment of Elder Derrick’s pronouncement, Campbell’s home became known as the unofficial embassy for the Church in Washington, DC. “I probably had a dinner party every ten days with one of the Brethren, a couple of CEOs, and nearly always a few congressmen, depending on what our objective was.”[12] The dinners at her home provided the perfect atmosphere in which to develop personal relationships with her dinner guests. “They would often stay for long and substantive talks after dinner,” she says. “That kind of interaction doesn’t happen in more formal settings.” As a result of these interactions, friendships and trust formed.[13] “It was amazing,” Campbell recalls. “I saw a miracle a day.”[14]

Director of International Affairs

In 1987, Campbell’s office gained the additional title of International Affairs.[15] The work of the International Affairs Department began in 1974 when President Kimball called David M. Kennedy “to assist the First Presidency with the explicit purpose of getting the Church into countries where it had no official presence.” While Kennedy had worked with officials abroad, Campbell worked with the embassies in Washington, DC, to foster a positive media presence. When Kennedy’s assignment ended, his work was absorbed by the Public Affairs Office, which was renamed the Office of Public and International Affairs. As director of that office, Campbell became “the key figure in obtaining for Church leaders an audience of government officials.”[16] When international issues arose, they often found their way to Campbell’s office,[17] where she would “marshal the resources and personnel necessary to address the issue,”[18] whether that issue was persecution of members, the inability of members to worship, or the forbiddance of missionaries in foreign countries.[19] She worked regularly with embassies and with the press and did a great deal of work with interfaith counsels, putting together interfaith events and conferences, all of which was “groundbreaking for the Church.”[20]

Planning International Events

With her new title and associated duties, Campbell’s efforts to create contacts remained her primary focus. In addition to her home dinner parties, Campbell “nurtured relations with people internationally by having large events,” developing many programs to acquaint ambassadors with the Church and to help them feel comfortable interacting with its members.[21] Among the most well-known events were the annual picnic at the Marriott Ranch, the annual Christmas parties at her home, and the temple lighting ceremony at the Washington D.C. Temple. Campbell would invite ambassadors from all over the world to these and other events.

Campbell began hosting the fall Western Family Picnic in October 1991. The event capitalized on the ambassadors’ desires to have an event to which they could take their families. “There are so few opportunities for diplomatic families to participate together in the formal life of Washington,” said Campbell to one newspaper reporter.[22] The annual event took place at the Marriott Ranch in Northern Virginia, where ambassadors and their families learned to dance the “Virginia Reel,” rode ponies, played shuffleboard, and learned about the Church and its history—all while having an enjoyable day in the country.[23]

“This was one of the most beautiful days my family and I have spent in Washington,” remarked Robert McClean, Peru’s ambassador to the United States. Richard Marriott agreed to the annual event’s success: “This gathering has produced more goodwill than countless Washington meetings.”[24] The event was such a success that sometime later, several ambassadors at a reception approached Campbell with their personal calendars, wanting to “ensure their plans would not conflict with the annual barbecue picnic at the Marriott Ranch.”[25]

Another popular event was the annual Christmas party that Campbell would host at her home with the Chinese embassy. Campbell “had an incredible number of very close relationships with Chinese government officials” and would invite the entire Communist Chinese embassy. “We’d have three to four hundred diplomats in the house singing Christmas hymns around the Christmas tree,” recalls her son, Tom.[26] Campbell also had a tradition of making a birthday cake for Jesus on Christmas Eve, which she used as an opportunity to talk about Christmas and the beliefs of the Church. Tom says, “I’m sure there are thousands of Chinese that think that’s part of the traditional Christmas ceremonies.”[27] Campbell’s Christmas party quickly became one of the most desired Washington invitations, second only to the Festival of Lights at the Washington D.C. Temple.

The Festival of Lights had its inauguration in 1978. The two-day Christmas time event began with a prayer at the visitors’ center, after which eighty thousand lights would be turned on around the temple square. Campbell inaugurated a second ceremonial night of lighting in which a host ambassador would be asked to join a Church dignitary in turning on the lights. She also began the tradition of having Christmas trees decorated with traditional cultural items from countries around the world. The tradition began with each country being represented by a doll that was placed on a large Christmas tree in the visitors’ center, which quickly mushroomed so that each country was represented with its own tree. The trees and the lighting ceremony helped to increase the visibility of the Church as an international organization.

The serene temple surrounded with lights also provided the perfect backdrop for introducing “international guests, members of the media, and local government, business and religious leaders,” to the basic beliefs of the Church. [28] Campbell recalls one instance when Elder Neal A. Maxwell of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles was the presiding Church dignitary. After the lighting, at a private reception for the ambassadors, an African ambassador fell to his knees and cried, “You are an apostle. I know you are an apostle of the Lord.”[29]

In addition to familiarizing others with the Church’s beliefs, the event publicly confirmed the positive relations between the Church and foreign diplomats. Ten years after the first Festival of Lights, ambassadors and diplomats from more than fifty countries attended the 1988 Festival of Lights, including officials from Brazil, Columbia, Czechoslovakia, Guatemala, Hungary, South Africa, and the Soviet Union. “Also in attendance were numerous Congressmen, high officials in executive and judicial government positions, clergy from other churches, and reporters from local and international press organizations.”[30] Campbell recalls, “I must have taken at least fifty or sixty ambassadors and their families to the temple. It got to be the big treat. When their children came they would call and say, “Will you take us to the temple?”[31]

Today, so many diplomats accept invitations to the Washington D.C. Temple lighting ceremony and other events that the occasions seem like UN sessions.[32] Through these large events and numerous more private meetings and interactions, Campbell “helped the ambassadorial community understand the Mormons were an integral part of the U.S. and that they weren’t strange folk.”[33] Following a day at the Marriott Ranch, Peru ambassador Robert Maclean remarked, “The Mormon people were warm and generous as anyone can imagine.”[34]

As a result of Campbell’s goodwill and hospitality, senators and representatives from Congress opened their doors to Church officials and representatives. Says Campbell, “My job was to create goodwill, to give them accurate, positive information so they would stand as our advocates in whatever court in their country they were standing in.”[35] The task was not an easy one.

Opening Doors for the Church

During Campbell’s time as director of the International Affairs office, the Cold War’s iron curtain and the Communist suppression of religious activity seemed impenetrable barriers to the spreading of the Church and the gospel. “Openings and opportunities were mercurial and fleeting,” Campbell recalled.[36]

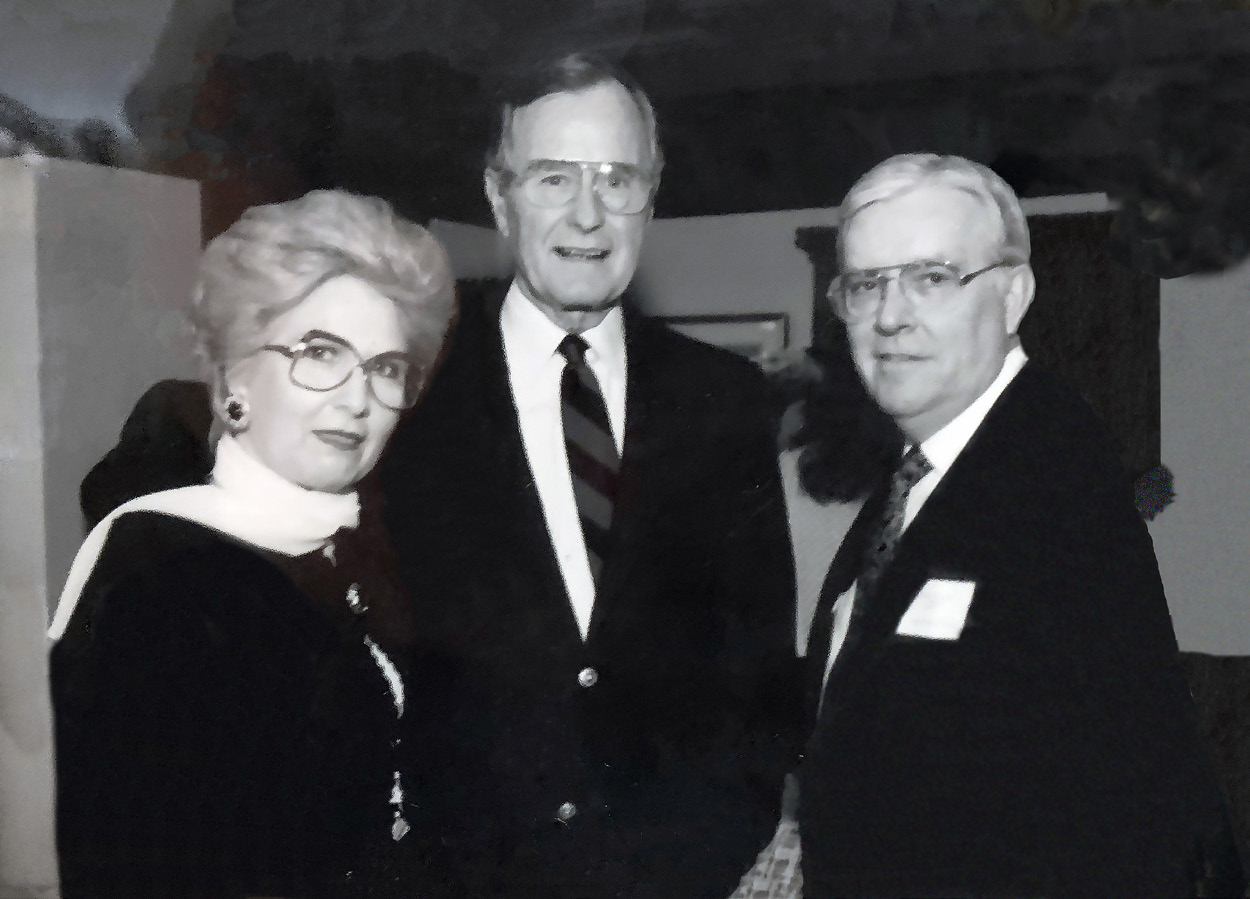

Beverly Campbell, President George H. W. Bush, and Elder M. Russell Ballard.

Beverly Campbell, President George H. W. Bush, and Elder M. Russell Ballard.

At first, getting just a finger in the door was a daunting and difficult task, but by 1985, “the Soviet empire’s western edge had begun to slough the doctrine of Communism.”[37] The Church got its hand in the door, then its foot, and then all at once it seemed, the door swung wide open. The tedious process of “first becoming acquainted with representatives of Eastern European nations in Washington, DC, and subsequently meeting their compatriots on the other side of the Atlantic had not only helped build bridges but also established trusting relationships that opened doors to the nations.”[38] Working behind the scenes in the American embassies, Campbell was able to establish relations and set appointments for General Authorities to meet with the governing officials in Eastern Europe. “She paved the way for the entry of the gospel in Eastern Europe working with Bulgarians and East Germans and Albanians and Yugoslavians,” her son recalls. “She was opening doors.”[39]

Opening Czechoslovakia

Many, if not most, of the doors Campbell was able to open were due to the contacts she had made. One such connection was with Rabbi Arthur Schneier, head of an organization known as the Appeal of Conscience Foundation. Whenever leaders from European countries were in New York, Rabbi Schneier would invite Campbell to meet with them. Due to this network, in 1986 Campbell was able to arrange for Miroslav Houstecky, the Czechoslovak Soviet Socialist Republic’s ambassador, to meet at her home with Elder Russell M. Nelson of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles. After dinner, Houstecky and Elder Nelson retired to Campbell’s study, where Elder Nelson was able to present the Church’s desire to practice openly. Ambassador Houstecky agreed to lend his best efforts in arranging a consultation with the minister of religious affairs in Prague. The minister was a member of the Communist Party who oversaw religious activity within the Communist regime. He was the one to determine which churches could be recognized as legitimate organizations. Meeting with the minister was an essential step for the Church to gain recognition in the Czech Republic.[40]

Ambassador Houstecky was successful in arranging a meeting; however, it would be another four years of yearly meetings before, following the collapse of the Berlin Wall, the Church would be granted legal authority in the Czech Republic. The long-awaited call came from Ambassador Houstecky, who had been successful in arranging meetings soon to be held in Prague with the new deputy prime minister of the Republic of Prague. Within a month of the meeting, on 21 February 1990, papers were signed that granted the Church official recognition and ended forty years of waiting for the few and faithful Saints in the Czech Republic.[41]

Opening Albania

While the Saints in the Czech Republic had waited for recognition, the people of Albania had suffered similar depravations. During WWII, Albanian citizens lived in isolation under “a Communist tyrant as maniacal as any in history.” In 1992 demonstrations and political unrest finally resulted in democratic developments and the election of a president, but when the door of the modern age opened on Europe, it slammed shut on Albania: “Over half the population did not have jobs, housing and food shortages forced two and three generations to live together in very small apartments, and the country’s infrastructure was dilapidated and barely functioning.”[42]

A year earlier, in 1991, Esat Ferra, an Albanian who defected, sought assistance for his country from the Austria Vienna Mission president Kenneth Reber. He provided the president with ten names of people that could assist the Church in helping Albania. These references later “proved to be the key in making contacts that gave the Church exposure at the highest levels of Albanian society.”[43]

At the time, there were not yet any diplomatic relations between Albania and the United States. Campbell “contacted the Albanian UN delegation in New York to obtain permission for Church officials to enter the country” and made the necessary “arrangements with the Europe Area office in Frankfurt for the visit of Elder Dallin H. Oaks of the Quorum of the Twelve and Elder Hans B. Ringger, the area president. Nevertheless, when the two Church officials arrived at the Tirana airport in April 1991, they were not permitted to leave the plane.” Campbell spent hours on the phone with Albania’s U.N. office in New York and Albanian officials in Tirana. Through her efforts, the two were permitted to deplane.[44]

Six months later, Elder Ringger and others returned to Albania and explained to the Department of Agriculture their willingness to meet the nation’s needs. Shortly thereafter, service workers flooded into the country. As a result of their presence, in 1992 Albania had its first convert to the Church. As Elder Ringger continued to meet with Albanian officials, he found them greatly impressed with the Church and its volunteers. In 1993, Elder Dallin H. Oaks flew to Albania to bless and dedicate the country for the spreading of the gospel.[45]

Picking Up the Pace and Office Expansion

Beverly Campbell hosting Nancy Reagan.

Beverly Campbell hosting Nancy Reagan.

After 1989, with the fall of the Berlin Wall, the pace at which the Church was welcomed into Europe grew exponentially. Campbell was at the home of her coworker Carolyn Ingersoll when she heard the news. “It’s not possible!” she exclaimed. Campbell knew that the collapse of the wall would open up “many doors to the Church.”[46] Indeed, many of the breakthroughs that Campbell was able to make for Church leaders came as a result of it. When asked which particular countries Campbell helped open, President M. Russell Ballard of the Quorum of the Twelve replied, “Every one that we had a challenge with.”[47]

Changes were happening so fast that to keep aware and stay on top of them, Campbell and her office staff were reading newspapers daily. Every morning they would skim the Washington Post, the Wall Street Journal, and a couple other newspapers “to find out what was happening”[48] in each of the countries they were focusing on.

To help manage the influx of information and opportunities, Campbell began expanding the office and staff by identifying people who had expertise in certain areas. Each staff member was responsible for an area of the world based on the Church’s assignment. They would keep Campbell abreast of the news in their assigned countries and help her arrange meetings and lunches with diplomatic representatives. She set a standard of high expectations for her staff. Said Carolyn Ingersoll, “She developed and ran in that office a very sophisticated, well-grounded, well-organized, well-executed machine.” She had developed a “procedure and a way of doing business for the Church that was very professional.” With strong secretarial support and hand-selected staff, Campbell was ready at the door for the influx of diplomats that came in the wake of the fall of the Berlin Wall.

Always the visionary, Campbell understood that there would be many new nations opening embassies in Washington and sending their ambassadors and that she would need to be prepared to meet them, saying, “All these people are going to come and have ambassadorial or counselor presence in Washington, and we need to get to know them.”[49] Over the next few months, Campbell and her staff worked to locate the emerging embassies and become acquainted with the incoming ambassadors to Washington, DC.

Campbell’s process of developing friendships with ambassadors and other officials is still the program of the Church today. “Part of what we still do is make friends for the Church that can be advocates for the Church in their respective countries,” remarked Elder Ralph W. Hardy Jr., an Area Seventy who served as a stake president in DC at that time.[50] Throughout the remainder of her life, Campbell still heard from people from all over the world with whom she had worked during her time in the International Affairs office. Nearly twenty years following her retirement, Campbell received an email from the deputy ambassador of the Soviet Union, who told her how he still thought of his trips to Salt Lake City and their talks about religion with great fondness.[51] Campbell also kept in touch with many ambassadors in China, Japan, the Soviet Union, and Ukraine.[52]

Campbell will be remembered as a pioneer, a dynamic leader, a powerful spokesperson, a wonderful representative of the Church, and a good and faithful servant to the Lord and facilitator for leaders of the Church.[53] During her tenure as director of International Affairs from 1987 to 1997, the Church had “gained official recognition in thirty-nine countries and new access to many more,” with Campbell having fostered “many of the initial contacts that opened those doors.”[54] When Campbell had begun work as director of the International Affairs office, “there were few ambassadors” that were known to the Church and “no established protocol for gaining appointments with the government officials of foreign entities.” Now the Church has close ties with many ambassadors from a multitude of nations across Europe and the world.

At a time when international doors were mostly shut, Campbell had held a strong belief “that when the time is right for doors to open, they will open.”[55] And open they did. President Ballard paid a fitting tribute when he said, “The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints came out of the darkness publicly because of the great work of this good woman.”[56]

Notes

[1] Beverly Campbell, interview by Mary Jane Woodger, 8 October 2010, Salt Lake City; transcription in author’s possession.

[2] Beverly Campbell, interview.

[3] Susan Easton Black and Mary Jane Woodger, Women of Character (American Fork, UT: Covenant Communications, 2011), 59.

[4] Francis M. Gibbons, Spencer W. Kimball: Resolute Disciple, Prophet of God (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1995), 262.

[5] Kahlile B. Mehr, “An LDS International Trio,” Journal of Mormon History 25, no. 2 (Fall 1999): 114.

[6] Carol Petranek, interview by Mary Jane Woodger, May 2019, Sandy, UT; transcription in author’s possession.

[7] Mehr, “LDS International Trio,” 114.

[8] Beverly Campbell, interview.

[9] Beverly Campbell, interview.

[10] Beverly Campbell, interview.

[11] Beverly Campbell, interview.

[12] Beverly Campbell, interview.

[13] Lee Davidson, “‘Ambassador’ Opens Doors for LDS Church,” Deseret News, 4 October 2010, 10.

[14] Beverly Campbell, interview.

[15] Mehr, “LDS International Trio,” 114.

[16] Kahlile B. Mehr, Mormon Missionaries Enter Eastern Europe (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2002), 93, 158.

[17] Mehr, “LDS International Trio,” 118. See also Mark Campbell, interview by Mary Jane Woodger, May 2019, Sandy, UT; transcription in author’s possession.

[18] Beverly Campbell, interview.

[19] Mark Campbell, interview.

[20] Carol Petranek, interview.

[21] Mark Campbell, interview.

[22] Myrna Wahlquist, “Diplomats Get a Taste of Old West at Picnic,” Church News, 26 October 1991, 11.

[23] Black and Woodger, Women of Character, 59.

[24] Wahlquist, “Diplomats Get a Taste of Old West,” 11.

[25] Davidson, “‘Ambassador’ Opens Doors for LDS Church,” 10.

[26] Mark Campbell, interview. See also Tom Campbell, interview by Mary Jane Woodger, May 2019, Sandy, UT; transcription in author’s possession.

[27] Mehr, “LDS International Trio,” 114.

[28] Kathryn Baer Newman, “Ambassador Helps Turn on Yule Lights,” Church News, 12 December 1998, 6.

[29] Beverly Campbell, interview by Mary Jane Woodger.

[30] Lee Davidson, “Christmas Message Delivered through Tools of Goodwill,” Church News, 17 December 1988, 9.

[31] Beverly Campbell, interview.

[32] Davidson, “‘Ambassador’ Opens Doors for LDS Church,” 10.

[33] Tom Campbell, interview.

[34] Wahlquist, “Diplomats Get a Taste of Old West,” 11.

[35] Beverly Campbell, interview.

[36] Spencer J. Condie, Russell M. Nelson: Father, Surgeon, Apostle (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2003), 247.

[37] Mehr, Mormon Missionaries Enter Eastern Europe, 111.

[38] Condie, Russell M. Nelson, 255.

[39] Tom Campbell, interview.

[40] Condie, Russell M. Nelson, 250.

[41] Condie, Russell M. Nelson, 252–53.

[42] Mehr, Mormon Missionaries Enter Eastern Europe, 267.

[43] Mehr, Mormon Missionaries Enter Eastern Europe, 267.

[44] Mehr, “LDS International Trio,” 118.

[45] Mehr, Mormon Missionaries Enter Eastern Europe, 270–73.

[46] Carolyn Ingersoll, interview by Mary Jane Woodger, May 2019, Sandy, UT; transcription in author’s possession.

[47] M. Russell Ballard, interview by Mary Jane Woodger, May 2019, Sandy, UT; transcription in author’s possession.

[48] Ingersoll, interview.

[49] Ingersoll, interview.

[50] Ralph W. Hardy Jr., interview by Mary Jane Woodger, May 2019, Sandy, UT; transcription in author’s possession.

[51] Beverly Campbell, interview.

[52] Hardy, interview.

[53] Petranek, interview. See also Wanda Franklin, interview by Brooke Anderson, May 2019, Provo, UT; transcription in author’s possession. See also Mark Campbell, interview.

[54] Davidson, “‘Ambassador’ Opens Doors for LDS Church,” 10.

[55] Petranek, interview.

[56] M. Russell Ballard, interview.