Bruce A. Chadwick and H. Dean Garrett, “Women’s Religiosity and Employment: The LDS Experience,” in Latter-day Saint Social Life: Social Research on the LDS Church and its Members (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1998), 401–424.

Bruce A. Chadwick is professor of sociology at Brigham Young University. H. Dean Garrett is professor of church history and doctrine at Brigham Young University. This article was originally published in Review of Religious Research 36:277–93; reprinted by permission.

Abstract

This study explores the relationship between women’s religiosity and employment. The hypothesis that a reciprocal relationship exists between religion and work was tested with data from a sample of three thousand women between the ages of twenty and sixty years living along the Wasatch Front in Utah during the spring of 1991. The responses of 1,130 women who belong to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, which has strong profamily values integrated into its theology, were analyzed. The effect of religiosity was tested examining the relationship between the measures of religiosity—religious beliefs, private behavior, and public behavior—and three measures of employment experience—current employment status, percent of adult life worked, and employment intentions for the future. The results reveal that religiosity has a significant relationship with LDS women’s employment. Employment is related to lower rates of religious activity, primarily attendance, and holding church positions.

Clergy, social scientists, and casual observers have long noted that women are more religious than men (Argyle and Beit-Hallahmi 1975; Alston and McIntosh 1979; Gee 1991; Thompson 1991). For example, DeVaus (1984), using information from Gallup polls and the NORC General Social Surveys, found significantly higher percentages of women than men attended church every year from 1947 to 1978. On the average, 10 percent more women than men reported “weekly” attendance (30–35 versus 20–25 percent). Men’s higher rate of labor force participation has frequently been suggested as an explanation for their lower religiosity. As more women have entered the world of work some observers speculate that their religiosity will decline.

At the turn of the century less than 20 percent of women fourteen years and older were in the labor force, and less than 5 percent of married women were in the labor force (Cox 1990, pp. 308–9). Today, 58 percent of all women over age twenty are working outside the home. Fifty-eight percent of married women with their husbands present are in the labor force, while 66 percent of mothers with children under eighteen are working (Statistical Abstract 1991, p. 389). The percent of women in the labor force will probably continue to rise until it approximates the rate for men (Morgan and Scanzoni 1987).

Most studies linking women’s religiosity and employment have implied a causal relationship as they have discussed the “impact,” “effect,” and “influence” of one on the other. Logic and social theory both suggest that the relationship is reciprocal. On the one hand, women who are highly religious are less likely to enter the labor force, as they favor the traditional housewife role. On the other hand, the demands of working outside the home, coupled with housekeeping, may take time away from religious activities. Also, workplace experiences may secularize women. Although the causation is probably reciprocal, we will review the literature according to the individual authors’ perceived direction of influence.

Religion’s Influence on Work

A frequently reported rationale asserts that religious values support wife and mother roles, which influence religious women to remain in the home. In an early test of the religious values-labor force participation hypothesis, Bainbridge and Hatch (1982) examined census data for 1930 and 1970 in ninety-three American cities to determine whether religious values as indicated by rate of church membership were related to the proportion of women in high status occupations (managers, bank officials, lawyers, judges, and physicians). They concluded that a high rate of religious affiliation in a community had not interfered with women pursuing high status occupations.

Morgan and Scanzoni (1987), however, found support for the hypothesis that religiosity is related to lower labor force participation. They surveyed 325 female college students about their current religious devoutness and their intentions to enter the labor force and pursue a career. Religious devoutness combined religious values, feelings, and activities. The researchers tested an elaborate path model that included four background factors, three mediating attitudes, and college major, along with devoutness, as predictors of intention to take and keep paid employment. Regardless of denomination, devoutness was related to lower intended labor force participation. The authors conclude that religiosity influences labor force participation.

Hertel (1988) attempted to test a causal link between church affiliation and labor force participation by comparing the religious affiliation of women to later labor force experience. Data from the NORC General Social Surveys from 1972 to 1985 were used to compare religious affiliation at age sixteen with current affiliation at date of survey. Female respondents were placed into one of five categories: “stable religion,” the same affiliation at age sixteen and at survey; “stable none,” no affiliation at age sixteen or at the survey date; “apostates,” affiliated at age sixteen, but not affiliated at survey; “converts,” not affiliated at age sixteen, but affiliated at survey; “switched,” changed affiliation between age sixteen and the survey date.

Hertel (1988) predicted that the “stable none” and “apostate” women, with their lower religiosity, would have higher rates of employment than women in the other three categories. Surprisingly, women in the “stable religion” category were employed as often as those in the “stable none” group. The hypothesis was partially supported as significantly more “apostate” women were in the labor force. Unfortunately, the data do not reveal whether the apostate women left their church before or after they went to work; thus it is not possible to infer whether abandoning their church influenced their employment or vice versa.

Heaton (1994) found the labor force participation rate for LDS women, whose religious values strongly favor traditional family roles, approximates the national average. However, religious beliefs were linked to work behavior as significantly more LDS women worked part-time, while more of their national counterparts had full-time employment.

Overall, only modest support has emerged linking women’s religious values to their employment experience. One reason for the rather weak findings may be the measures of religious values. Most studies inferred religious values from affiliation and attendance. Research has shown that religiosity is composed of several relatively independent dimensions (Demerath 1965; Glock and Stark 1965; DeVaus and McAllister 1987; Chadwick and Top 1993). Different dimensions of religiosity may have different relationships to employment. For example, Jones and McNamara (1991) discovered among a sample of female undergraduate women that intrinsic religious orientations were related to intentions to remain at home during children’s early years, but extrinsic religious orientations were not.

Work’s Influence on Religiosity

Some social scientists argue that women who cope with the time demands of a full-time job and maintain a household are less involved in church activities because of time constraints (Glock, Ringer, and Babbie 1967). Although no longitudinal studies have been conducted, it is assumed that time previously devoted to religious activities is shifted to household work and family activities. Women who in former times were in church on Sunday now spend the day doing housework, participating in family recreation, enjoying personal leisure, or resting. Occasionally women are required to work on Sundays, which interferes with church attendance.

Another explanation for employment’s impact on religiosity is the replacement of religious values with those relevant to the workplace (Lenski 1953). In other words, loving, expressive religious and profamily values diminish in importance and are replaced, to a degree, by competitive, instrumental workplace values. Luckman (1967) suggests that as women enter the labor force they are impacted more fully by industrialization/

A final explanation for linking work and religiosity focuses on shifting social ties. It has been suggested that working women develop friendships with co-workers and reduce their attachment to friends from their church (Moberg 1962). Thus social ties supportive of religious activities are replaced by friendships with co-workers and secular activities.

Although it did not separate the effects of the above three influences, an early study linked employment to religious activity by analyzing three national surveys collected by the Survey Research Center at the University of Michigan in 1957 and 1958 (Lazerwitz 1961). The study showed that both Protestant and Catholic women in the labor force attended church as often as women who did not work.

DeVaus (1984) examined the NORC General Social Surveys for the period 1972 to 1980 and also found that employment was not related to lower church attendance for women. Fifty-one percent who worked full-time, 56 percent who worked part-time, and 54 percent of women who did not work attended church regularly. Thus, DeVaus rejected the notion that time availability influences church attendance.

Ulbrich and Wallace (1984) analyzed the responses of 476 Christian women who either worked full-time or not at all in the 1980 NORC General Social Survey. They found that working women attended church less often than housewives. However, when they calculated bivariate correlations between twenty-eight independent variables and church attendance for both the working and non-working women, they found that attendance was related to age, religious intensity, and having a spouse of the same denomination. They concluded:

Thus, in general, working individuals are younger, less religious (by their own description), and less likely to have a spouse of the same religion. This suggests that working women may come from a different “pool” from non-working women and no conclusions can clearly be drawn about how these women will behave as they age—whether they will become more religious and consequently attend more often or whether their distinctiveness is permanent, (p. 349)

DeVaus and McAllister (1987) tested three hypotheses explaining the difference in religiosity of men and women in Australia. The hypotheses focused on women’s structural location in society. Women’s child-rearing role was hypothesized to lower labor force participation while stronger family values were anticipated to increase their higher religiosity. They found that women’s lower labor force participation was related to higher religiosity. This finding is inconsistent with their earlier discovery that workplace experience “does not appear to affect” women’s religiosity in the United States (DeVaus 1984). They reconciled the contradictory findings by speculating that religiosity persists among employed U.S. women because religion is more strongly integrated into mainstream American culture.

In spite of strong theoretical reasons to anticipate that workplace participation is related to lower levels of religious activity in women, the hypothesis has not been supported in previous research. Working women appear to be almost as religious as housewives.

These weak findings may be due in part to the measures of labor force participation and religiosity used in the various studies. Labor force participation generally has been measured as employment status at the time of the survey. Glass (1992) argues that the relationship between employment and traditional family attitudes (and probably religious values) cannot be fully understood by examining only employment. She concludes the meaning of employment is as important as the actual work experience in explaining women’s religious values. As mentioned earlier, religiosity typically was measured by denominational preference or by church attendance. Perhaps if more sensitive measures of employment experience and religiosity were studied a stronger relationship would be revealed.

Research Objectives

Our first objective was to examine, within the limits of survey data, the relationship between current religious values and employment of women. To accomplish this, we assessed the relationship between religious values and employment among women affiliated with a conservative religion, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS). Along with traditional Christian beliefs concerning family roles, LDS theology contains additional beliefs that strongly encourage women, especially mothers, to remain out of the labor force. For example, in 1983, the President of the LDS Church, who is revered as a prophet, plainly taught that “Mothers are to spend their full time in the home in rearing and caring for their children” (Benson 1987). Thus LDS women, with their presumed acceptance of what they consider to be modern “scripture” encouraging them to remain in the home, are an excellent population to test the religious values-employment hypothesis. We assessed whether LDS women with stronger religious values had lower labor force participation than LDS women with weaker values.

The second research objective was to examine the relationship between employment and religious activity. It was hypothesized that employed LDS women would participate in fewer religious activities because of time constraints. Specifically we examined the relationship between time constraints and religious activities by comparing the frequency and type of church positions held by working LDS women to those of housewives. We anticipated that fewer employed LDS women would have a church position, and those with a calling would have a less demanding one. Also, we asked employed LDS women whether the demands of work, housekeeping, and family activities required them to reduce their religious activity.

To accomplish these objectives, we obtained several measures of both religiosity and workplace participation. We asked religious preference along with items measuring three dimensions of religiosity: religious beliefs, private religious behavior, and public religious behavior. Work experience was measured as the woman’s current employment status, the percent of her adult life she has worked, and future employment intentions.

Methods

Data Collection

A mail questionnaire survey was conducted by the Center for Studies of the Family at Brigham Young University in the spring of 1991 with a sample of three thousand women between the ages of twenty and sixty living along the Wasatch Front in Utah. The R. L. Polk Company drew a random sample of women in these ages living in the metropolitan strip from Ogden to Provo, which includes Salt Lake City.

A packet was sent to each woman which included a letter explaining the study, stressing the confidentiality of the information, and requesting her participation. A questionnaire was included, along with a self-addressed business reply envelope.

A postcard reminder was mailed approximately three weeks later. One month after the postcard, a new packet, including letter, questionnaire, and return envelope was sent. A final approach, one month later, was made with another full packet. The letter was modified for each subsequent contact. These procedures produced 1,431 completed questionnaires. The sample was reduced by 133 women who had moved and left no forwarding address, so the response rate is 50 percent. The response rate is low, given the number of follow-up contacts. BYU sponsorship may have reduced response by non-LDS women and inactive LDS women.

Measurement of Variables

Demographic characteristics—age, education, religious preference, marital status, and number of children—were measured with single questions asking the relevant information. Religious preference was determined by asking “What is your religious preference? Protestant, Roman Catholic, LDS, No preference, or Other.” Religious beliefs were assessed with three questions on traditional Christian beliefs, “There is a God,” “Jesus is the divine Son of God,” and “There is life after death.” An additional seven items asked about acceptance of unique LDS beliefs, including “Joseph Smith was a true prophet of God” and “The Book of Mormon is the word of God.” The five response categories ranged from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree,” with “mixed feelings” as the mid-point.

Private religious behavior was measured by the frequency of private prayer and scripture study. The responses included “daily,” “a few times each week,” “a few times each month,” “a few times each year,” and “never.” Financial contributions were also included in private religiosity. The question was “How much money did you give your church last year?” The responses included “none,” “0 to 2%,” “3 to 5%,” “6 to 9%,” and “10% or more of income.” A final item asked whether the women felt they had internalized a religious culture that influenced their daily activities. The item asked was “My religion has considerable influence on my behavior.” The response categories ranged from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree.”

Public religious behavior was evaluated by asking the frequency of attendance at religious services. The response categories were “weekly,” “at least monthly,” “several times a year,” “once or twice a year,” and “not at all.” For LDS women, we asked their attendance at three different LDS religious Sunday services. We also asked them how often they hold Family Home Evening where LDS families participate in religious instruction and recreation each Monday evening. The response categories were “weekly,” “two or three times a month,” “monthly,” “seldom,” and “never.” In addition, the frequencies of family prayer and family scripture reading were obtained. The responses ranged from “daily” to “never.” We also asked the women, “Do you hold a church calling(s) at the present time?” Those that reported yes, were then asked, “What is your calling?”

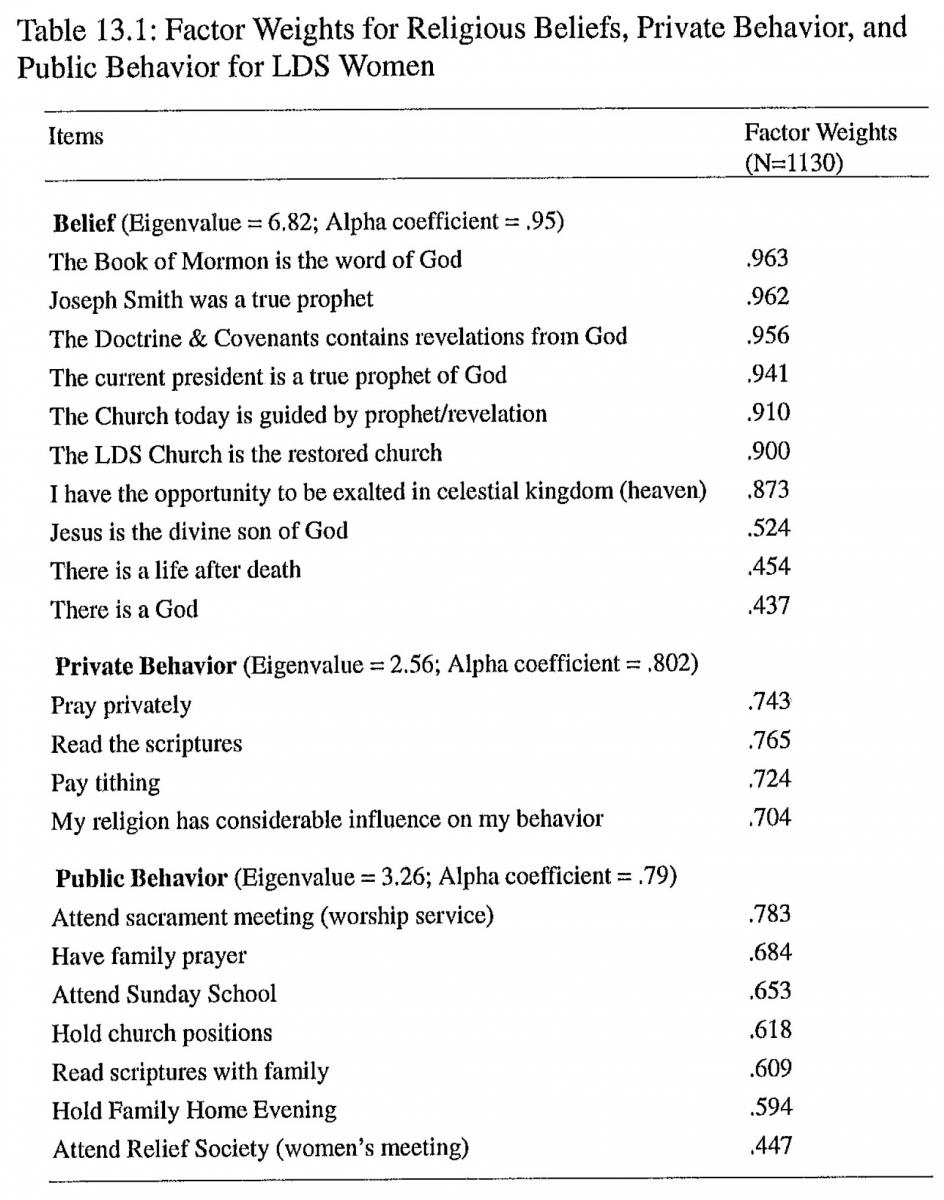

Previous research with LDS respondents has demonstrated that these religious items separate into the three independent dimensions of religiosity: beliefs, private behavior, and public behavior (Chadwick and Top 1993). Therefore the ten belief items, six public behavior items, and four private behavior items were submitted to principal components factor analysis. Standardized individual scores were computed for respondents on each of the scales using the regression method (SPSS 1984). The individual questions, factor weights, eigenvalues, and Chronbach Alpha coefficients are presented in table 13.1. The factor weights, eigenvalues, and alpha coefficients indicate the items combined to produce reliable unidimensional scales.

Employment status was gauged by asking: “Are you currently employed?” The response categories included “no,” “yes: part-time,” and “yes: full-time.” The number of years the women had participated in the labor force was identified with the following question: “Would you please estimate how many years of your life that you have worked for pay, either full- or part-time? Please add parts of years together.” Finally, employment intentions were measured by asking housewives: “Do you expect to go to work in the next two years?” Working women were asked, “Do you expect to continue working during the next ten years?” The five response categories ranged from “definitely yes” to “definitely no.”

The percent of their adult lives the women had spent in the labor force was calculated by subtracting the age they started working from their current age. The years of potential employment were then divided into the number of years they estimated they had been in the labor force. We computed the percent of their adult lives they had been employed full-time and part-time.

Description of Sample

Eighty percent of the women in the sample identified themselves as members of the LDS Church. Nine percent reported affiliation with a Protestant Church, 4 percent with the Catholic Church, and 6 percent indicated no religious preference or affiliation. The percent of LDS is comparable to the 75 percent LDS in the state. The five counties from which the sample was drawn range from a low of 60 percent LDS to a high of 83 percent. The average in these counties is 66 percent, and thus, LDS women are somewhat over-represented in the sample. This may have been a function of the BYU sponsorship, the subject of the survey, or both.

Results

Religion’s Influence on Employment

To test the hypothesis that religiosity is related to employment we evaluated the relationship between strength of religious beliefs, private religious behavior, and employment experience. We first compared LDS women’s religious beliefs and private religious behaviors to their current employment status, the percent of their adult life employed, and their employment intentions. We did not include public religious behavior in this analysis because we did not want to introduce a time constraint. Most studies have examined time pressures as a reason given by employed women to reduce their religious activity. In LDS culture, public religious behaviors make rather heavy demands on the women’s time and must compete with the pressures of work and family. Obviously, religious beliefs by themselves do not require any of the women’s time, and private behaviors of praying, reading the scriptures, and making financial contributions can be done in odd moments.

As discussed earlier, standardized factor scores were computed for religious values and private behavior. We attempted to divide the women into three equal-size groups of high, medium, and low belief scores and private behavior scores. These LDS women reported such strong religious beliefs that they fit into only two groups. Three-fourths of the women “strongly agreed” with all ten items and thus had the maximum score available on the scale. These women comprise a group of “very strong beliefs,” and the other fourth of the respondents are a “less than very strong belief group. There was greater variation among these LDS women’s private religious behavior, but they are still a highly religious group. For example, 73 percent of the women paid a “full tithe” of 10 percent of their income. Sixty percent prayed privately daily. The least frequently occurring behavior was reading the scriptures, as only 20 percent did so daily. Given this variation, we were able to divide private religious behavior into three groups of fairly comparable size.

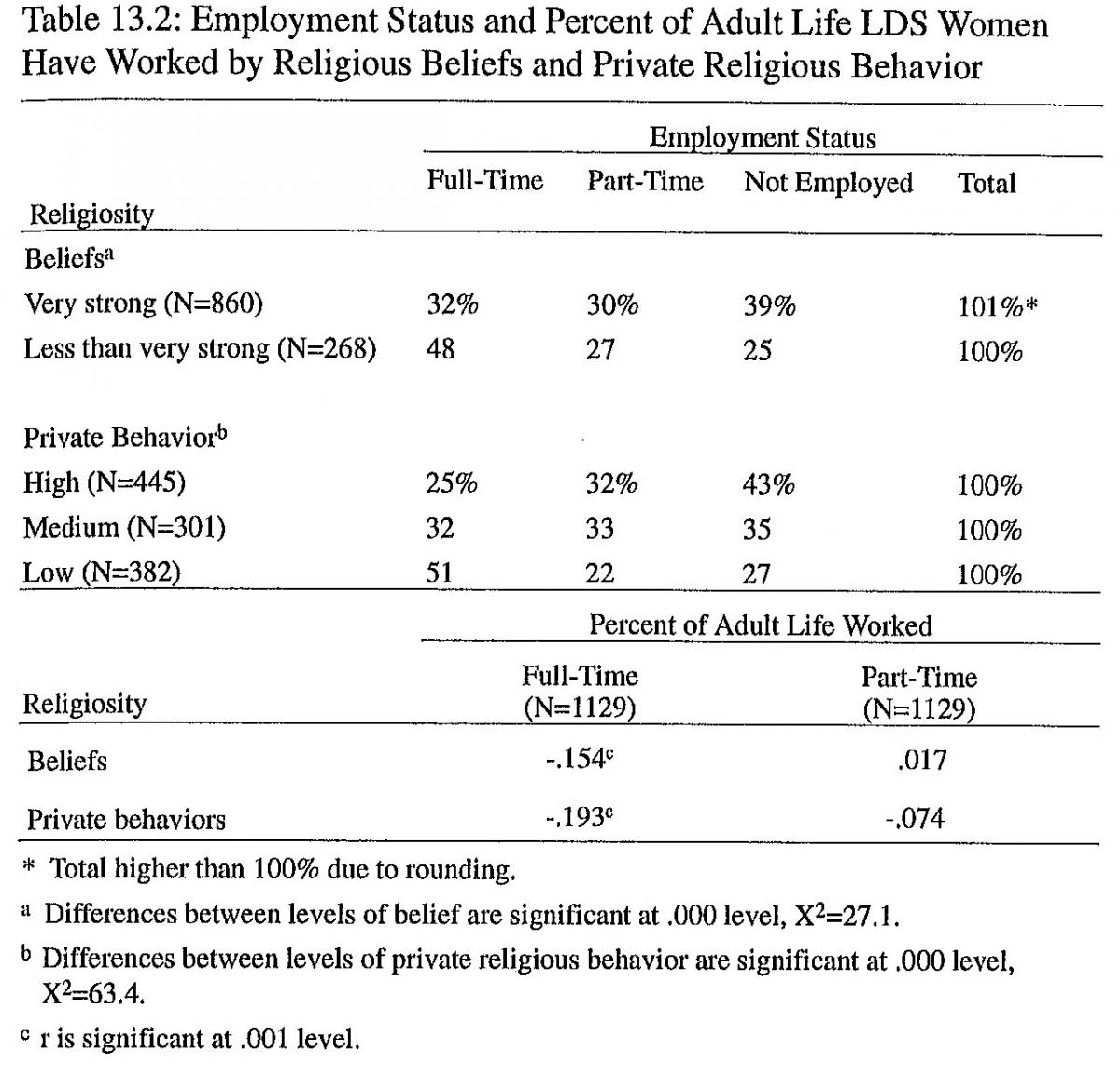

The hypothesis of a relationship between religious beliefs and employment is supported (table 13.2). It should be noted that roughly one-third, 36 percent, of the women in the sample were housewives, 28 percent worked part-time, and 36 percent were employed full-time. Those women holding very strong beliefs were significantly more often housewives than women with lower levels of belief. Thirty-nine percent of the women with very strong religious values were not employed as compared to 25 percent of the women with weaker beliefs. In addition, religious beliefs were significantly correlated with the percent of their adult life the women had been in the labor force (lower panel of table 13.2). The stronger a woman’s beliefs, the less time she had spent in the workplace. As can be seen, religious beliefs were not related to part-time work, but were strongly related to full-time employment. If the sample had included a large number of women with weak religious beliefs it is suspected that the effect would have been even stronger.

The results relating private religious behavior to current employment status are also as anticipated. Those women who pray, study the scriptures, pay the tithe, and feel that their religious beliefs influence them more often are significantly over-represented in the housewife category and under-represented among those working full-time. Forty-three percent of the women with high rates of private religious behavior were not employed, while only 27 percent of those with a low rate of private religious behavior were not in the work force. The correlations between private behaviors and percent of adult life employed full-time also supports the hypothesized relationship (r = .193; p<.001). The women who frequently pray, study the scriptures, contribute money to their church, and feel their religious beliefs are important had spent less time in the labor force.

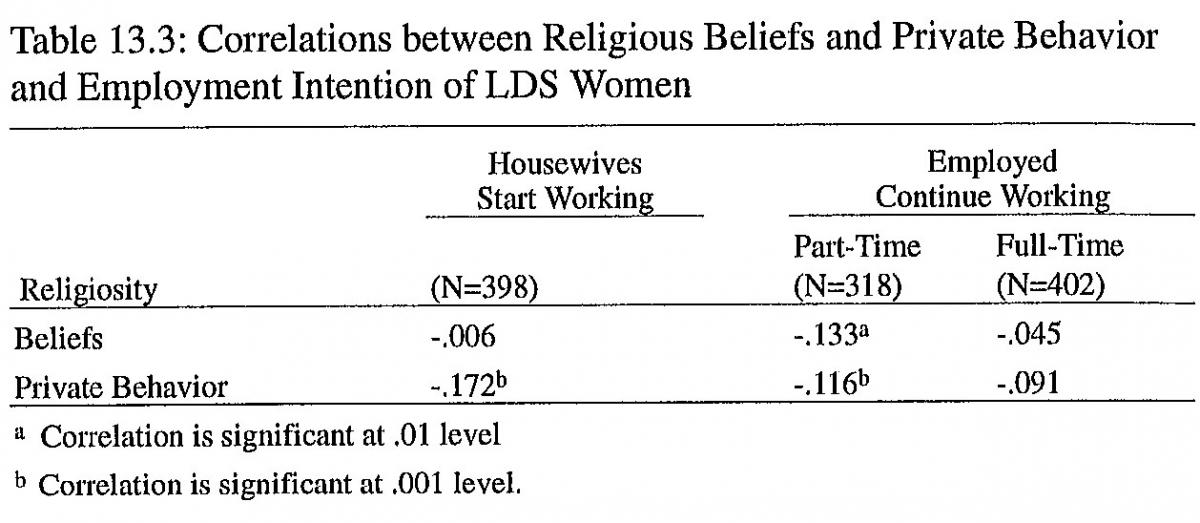

We constructed table 13.2 to reflect the conventional interpretation that religion has influenced labor force participation. Some support for religiosity’s causal relationship to employment appeared in the women’s future labor force intentions. We asked housewives whether they expected to go to work outside the home in the next two years and employed women if they anticipated remaining in the labor force for the next ten years. The correlations between the religious beliefs, private behavior, and employment intentions are presented in table 13.3, and indicate a fairly strong relationship between current religiosity and anticipated future labor force participation.

Religious beliefs were not related to intentions. This lack of a relationship probably reflects the fact that nearly all of these women reported exceptionally strong beliefs. On the other hand, the higher the rate of private religious behavior, the stronger the intention to remain out of the workplace. The religiosity of women who work part-time has a significant influence on their employment intentions. Both religious beliefs and private behavior are negatively related to these women’s intentions to remain employed. It may be that their religiosity probably influenced their decision to take part-time rather than full-time employment. These women are less committed to the workplace, and those with stronger religious beliefs and higher rates of private behavior intend to quit their employment sometime in the future. Neither religious beliefs nor private behavior are significantly related to the employment intentions of women employed full-time. These women seem to be committed to long-term employment regardless of their religiosity. These findings suggest that for housewives and women who work part-time, religiosity, especially their private behavior, influences their employment intentions.

In an earlier study Ulbrich and Wallace (1984) noted that younger, less religious women were in the workplace more often than older, more religious women. In order to assess the influence of not only age but also education on the relationship between religiosity and employment, we entered age and education into a multiple-regression equation before adding either religious beliefs or private behavior to explain the percent of time in the labor force. The betas produced by beliefs and private behavior in the regression equation explaining full-time work experience are as strong as the bivariate correlations reported in table 13.2. For example, the bivariate correlation between private religious behavior and percent of adult life worked full-time is –.193, while the beta produced by public behavior with age and education in the regression equation is –.185. Age made a significant contribution (Beta = –.082) but did not greatly impact the relationship between private religious behavior and full-time work experience. Although younger LDS women are more often employed, the relationship between religiosity and employment experience is not a spurious one produced by age or education.

Another way we attempted to assess the causal link between religiosity and employment was through the reasons housewives gave for not being in the labor force. The question asked was “Why don’t you work? (Check as many as apply)”: (1) “I don’t have necessary training or skills,” (2) “Working is not rewarding to me,” (3) “I can’t find a job,” (4) “I can’t find a job I enjoy,” (5) “I can’t find a job that pays enough,” (6) “I have a baby,” (7) “I am raising a family,” (8) “Because of my religious values,” (9) “I am attending school,” (10) if married: “My husband is opposed to my working,” and (11) “Other reasons.” Eighty-eight percent of the nonemployed women stated they don’t work because they are raising a family. Importantly, the second most often repeated reason was because of their religious values. Over half, 60 percent, indicated that their religious beliefs and values influence them to stay at home. Less than 15 percent of the women gave employment-related reasons such as a lack of training, job availability, or low pay. The percentages for the different reasons total more than 100 percent because the women checked more than one reason for not working. Importantly, family and religious considerations were the reasons these housewives gave for remaining at home.

Another way of inferring that religiosity influences women’s employment was to examine the women’s responses to the question of whether their religious beliefs affect their decision to work outside the home. We content analyzed the written comments to the question, “Do your religious beliefs affect your working outside the home or not?” We coded the various responses asserting the independence of religious beliefs to employment status into a “no effect” category. Responses about staying home, working in the home, and working part-time because of religious beliefs were coded into a “reduce employment activity” category. Some working women reported their religious beliefs made them feel guilty or depressed about working. Also, a few reported anger or resentment that their religious beliefs conflict with their working. These types of comments were coded into a “negative feelings” category. The reliability between two independent coders was 94 percent. Fifty-three percent of the women indicated their religious beliefs influenced them to reduce their employment activity. Most of these women reported their religious beliefs convinced them to stay in the home, while the others were influenced to seek part-time work or to work in their home. Thirty-eight percent of the women stated their religious values had no impact on employment behavior. These women tended to be those with weaker religious beliefs. Finally, 9 percent of the women noted that although their religious beliefs did not keep them out of the labor force, they did generate guilt, depression, or anger about their employment. The fact that over half of the women felt that their religious beliefs influenced whether they worked outside the home or not supports the belief-employment hypothesis.

Overall, the data support the hypothesis that religiosity, as measured by beliefs and private worship, is moderately related to lower employment among LDS women. Reasons housewives gave for not working, their employment intentions, and self-reported impacts support the contention that religiosity reduces employment participation.

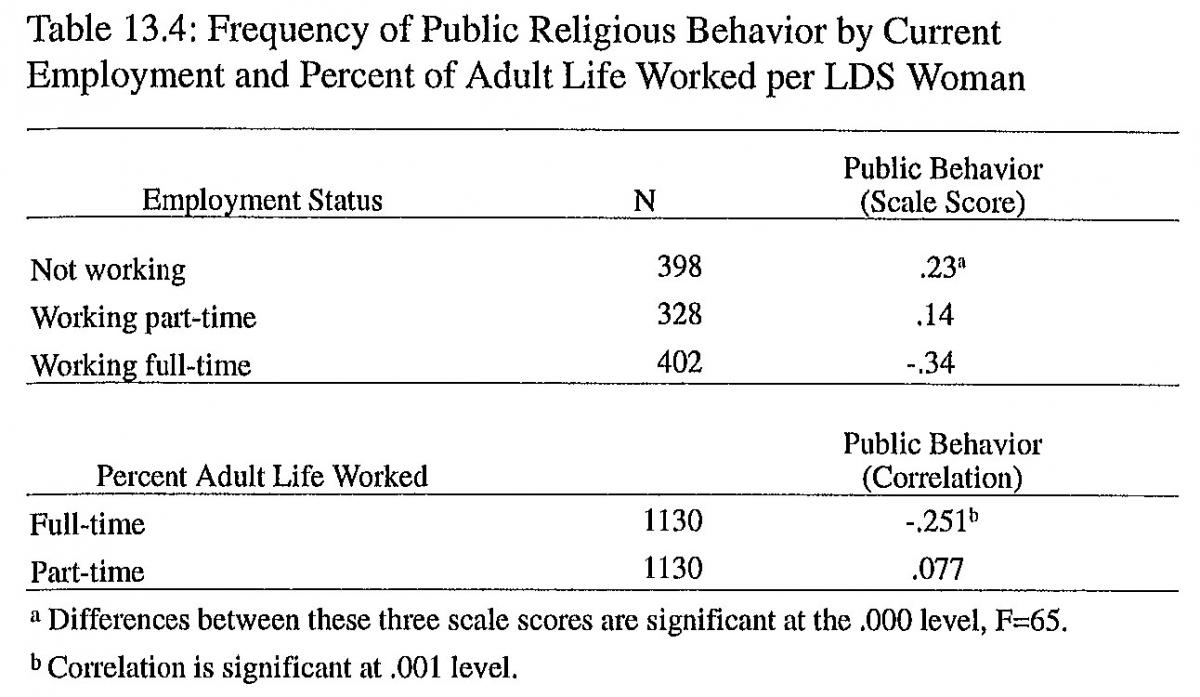

Employment’s Influence on Religiosity

The relationship between employment and religious activity was first assessed by comparing the public religious behavior of employed women and housewives. Public religious behavior includes attendance and other activities that require considerable time, and thus it was anticipated that working women would have lower activity. It was hypothesized that women working outside the home would have lower rates of public religious behavior because they use their time for housework and family activities. As can be seen in table 13.4, housewives had significantly higher public behavior scale scores than working women. The factor analysis set the mean value of the scale to zero, and thus it is clear that not working has a positive relationship with public religious behavior since the housewives’ score was .23. On the other hand, the –.34 score demonstrates that working full-time is associated with lower public religious behavior.

The percent of adult life the women have worked is also significantly related to public religious behavior. The correlations reported in the lower panel in table 13.4 demonstrate that women who have worked a higher percent of their adult life had lower public religious activity. The relationship between full-time employment and religious activity is rather strong, while part-time employment is not related to activity.

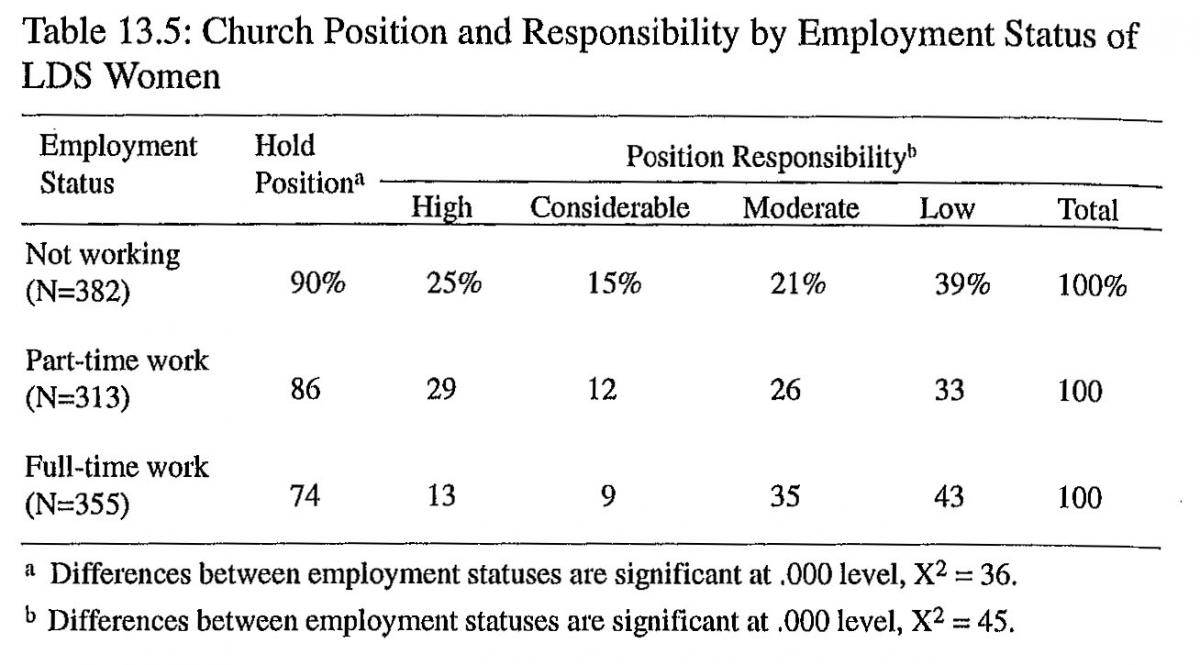

A specific test of the time-constraint hypothesis was the comparison of church positions held by employed women and housewives. Significantly more housewives and women who worked part-time had a church position than women employed full-time (see table 13.5). In addition, we coded church positions into four categories based on their responsibility and time demand. President and councilor in church organizations were coded as “high” and advisor, instructor, and teacher were assigned “considerable” responsibility. Secretary and assistant advisor were coded as “moderate” and finally, music and other minor positions were placed in the “low” responsibility category. Housewives and part-time employed women held significantly more responsible positions than those employed full-time. Over 40 percent of the housewives and women employed part-time held positions with “high” or “considerable” responsibility as compared to only 22 percent of the full-time employed women.

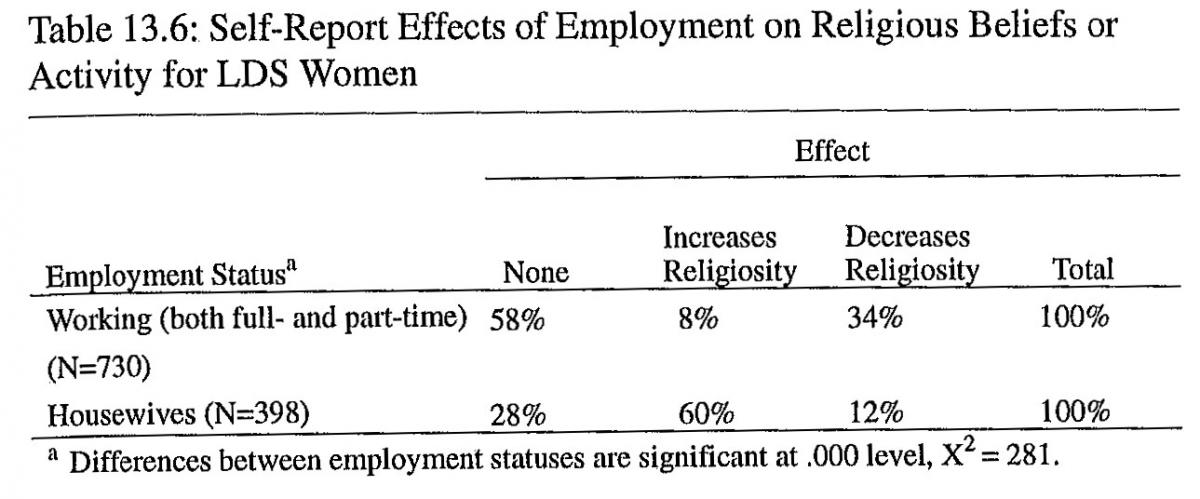

We also asked the women whether their current employment status was affecting their religious beliefs or activity. The question asked was: “How does your (not) working affect your religious beliefs and activities?” We coded the written responses into three categories. The first included comments asserting their employment had “no influence” on their religiosity. Statements about how their employment increased their ability, time, money, and opportunities to attend church or to serve in church callings were categorized as “increasing religiosity.” Having to work on Sunday, doing family and housekeeping activities that preempted religious activities, and being too busy or too tired to hold a church calling were coded as “decreasing religiosity.” The reliability in coding between two independent coders was 96 percent. Table 13.6 presents the data for both employed women and housewives. The perceived impact of working is obvious. Only 8 percent of the employed women reported their working increases their religiosity as compared to 60 percent of the housewives who indicated their not working fosters greater religious activity. Thirty-four percent of the employed women believe their work decreases their religious activity, while only 12 percent of housewives felt that staying home stifles their religiosity. It is clear that employed LDS women feel that their work limits their religious participation.

Another measure of how employment demands reduce religious activity involved asking the women with lower rates of attendance why they didn’t participate more. The question was: “If your answer to Church attendance was ‘monthly,’ ‘seldom,’ or ‘never,’ which of the following would best describe the reasons why you don’t attend more often (check as many as apply).” The ten possible reasons listed for respondents to check included, “My family demands prevent me from attending” and “I have to do housework.” Only 2.5 percent of the housewives, 2.4 percent of those working part-time, and 4.5 percent of those employed full-time identified family responsibilities as keeping them out of church services. These small differences are not significant. For many LDS participants, church activity is defined as a family activity and is one way to share time together. Only .3 and .6 percent of housewives and part-time workers, respectively, identified the need to do housework on Sunday as a reason for missing services, while 7 percent of the full-time employed women did so. Although the number is small, significantly more women employed full-time believe that it is necessary to spend Sunday completing housework and consequently skip church services.

A final measure of time conflict between employment and religious activity was the frequency of Sunday work. Working on Sunday is but a minor deterrent to church attendance as only 4 percent of the employed women reported they miss church services because they have to work.

Among LDS women, employment is significantly related to lower participation in religious activities, including holding a church calling. Based on self-perceived effects, it appears that full-time employment reduces women’s religious behavior. Housework and Sunday work had only a minor impact on religious activities.

Discussion and Conclusions

The results obtained in this study demonstrate the circular link between the religiosity and employment of LDS women. The predicted pattern that Christian/

Three independent dimensions of religiosity were related to three different measures of women’s employment. Religious values and private religious behaviors were significantly related to current employment status, long-term employment experience, and intentions to remain in the labor force or to leave it. Religiosity emerged as a significant correlate of, and perhaps a cause affecting, labor force participation.

Some researchers have noted that employed women are demographically different from housewives. They are younger and better educated. In this study of LDS women, those employed were younger, but did not have any more education than housewives. Importantly, the relationship between religiosity and employment was not affected by education and only modestly by age. Even among young and highly educated women, religiosity and employment were significantly related.

It was hypothesized that women’s employment, in turn, is related to lower public religious behavior, especially attendance. Rather strong evidence of employment’s relation with religious activity appeared in the lower frequency that employed women attended church. Support for the time constraint hypothesis was obtained in the smaller number of employed women who filled church positions. Additional evidence is that employed women who did hold positions had less demanding ones. The small number of employed women who reported they use Sunday to do their housework reveal that this direct competition for the women’s time reduces attendance only slightly. It seems the employed women have time to attend religious services, but not to fill a demanding leadership position.

Finally, the relationship between religiosity and employment does not mean that all religious women are housewives or that all employed women have lost their faith and left the church. As noted earlier, these LDS women reported strong religious beliefs and high rates of religious behavior. We were amazed at the ability of the women to maintain their religiosity in spite of the time demands of full-time employment. Many of the LDS women in this study reported they recognize that working outside the home is inconsistent with their religious beliefs and that it threatens time they want to devote to religious activity. They also stated their strong resolve to minimize these effects. The results of this study suggest that although these women have not been completely successful, their employment has not lead to a wholesale abandonment of faith and church.

References

Alston, J. P. and W. A. McIntosh. 1979. “An Assessment of the Determinants of Religious Participation.” The Sociological Quarterly 20:49–62.

Argyle, Michael and Benjamin Beit-Hallahmi. 1975. The Social Psychology of Religion. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Bainbridge, William S. and L. R. Hatch. 1982. “Women’s Access to Elite Careers: In Search of a Religion Effect.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 21:242–55.

Benson, Ezra Taft. 1987. To the Mothers in Zion. Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

Chadwick, Bruce A. and Brent L. Top. 1993. “Religiosity and Delinquency among LDS Adolescents.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 32:51–67. Also in this volume.

Cornwall, Marie, Stan L. Albrecht, Perry H. Cunningham, and Brian L. Pitcher. 1986. “The Dimensions of Religiosity: A Conceptual Model with an Empirical Test.” Review of Religious Research 27:226–44. Also in this volume.

Cox, F. D. 1990. Human Intimacy: Marriage, the Family and Its Meaning. 5th ed. St. Paul, MN: West.

DeVaus, D. A. 1984. “Workforce Participation and Sex Differences in Church Attendance.” Review of Religious Research 25:247–56.

DeVaus, David and Ian McAllister. 1987. “Gender Differences in Religion: A Test of the Structural Location Theory.” American Sociological Review 52:472–81.

Demerath, Neil J. III. 1965. Social Class and American Protestantism. Chicago: Rand McNally.

Gee, E. M. 1991. “Gender Differences in Church Attendance in Canada: The Role of Labor Force Participation.” Review of Religious Research 32:267–73.

Glass, J. 1992. “Housewives and Employed Wives: Demographic and Attitudinal Change, 1972–1986.” Journal of Marriage and the Family 54:559–69.

Glock, Charles Y. and Rodney Stark. 1965. Religion and Society in Tension. Chicago: Rand McNally.

Glock, Charles Y., B. B. Ringer, and E. R. Babbie. 1967. To Comfort and to Challenge: A Dilemma of the Contemporary Church. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Goodman, Kristen L., and Tim B. Heaton. 1986. “LDS Church Members in the U.S. and Canada: A Demographic Profile.” AMCAP Journal 12:88–107.

Heaton, Tim B. 1994. “Familial, Socio-Economic, and Religious Behavior: A Comparison of LDS and NonLDS Women.” Dialogue 28:169–83.

Hertel, B. R. 1988. “Gender, Religious Identity, and Work Force Participation.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 27:574–92.

< lang="ES">Jones, B. H., and K. McNamara. 1991. “Attitudes toward Women and their Work Roles: Effects of Intrinsic and Extrinsic Religious Orientations.” Sex Roles 24:21–29.

Lazerwitz, B. 1961. “Some Factors Associated with Variations in Church Attendance.” Social Forces 39:301–9.

Lenski, Gerhard E. 1953. “Social Correlates of Religious Interest.” American Sociological Review 18:533–44.

Luckmann, T. 1967. The Invisible Religion. New York: Macmillan.

Moberg, D. 1962. The Church as a Social Institution. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Morgan, M. Y. and J. Scanzoni. 1987. “Religious Orientations and Women’s Expected Continuity in the Labor Force.” Journal of Marriage and the Family 49:367–79.

SPSS. 1984. SPSS-X User’s Guide. Chicago: SPSS.

U.S. Bureau of the Census. 1991. Statistical Abstract of the United States, 1991. 111th ed. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Thompson, Edward H. 1991. “Beneath the Status Characteristic: Gender Variations in Religiousness.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 30:381–94.

Ulbrich, H. and M. Wallace. 1984. “Women’s Work Force Status and Church Attendance.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 23:341–50.