Secularization, Higher Education, and Religiosity

Stan L. Albrecht and Tim B. Heaton

Stan L. Albrecht and Tim B. Heaton, “Secularization, Higher Education, and Religiosity,” in Latter-day Saint Social Life: Social Research on the LDS Church and its Members (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1998), 293–314.

Stan L. Albrecht is professor of health policy and epidemiology at the University of Florida in Gainesville, Florida. Tim B. Heaton is professor of sociology at Brigham Young University. This article was originally published in Review of Religious Research 26:43–58; reprinted with permission.

Abstract

This paper examines the secularization thesis in terms of the relationship between level of education and various measures of religiosity. National data indicate a negative relationship: the most educated are the least religious. Within denominations, however, there is a positive relationship between education and church attendance. Among Mormons, this positive relationship is also found for other measures of religiosity. Possible explanations for the positive relationship support the conclusion that higher education does not have a secularizing influence on Mormons.

The last several years have seen the emergence of a growing literature based on the general thesis that we live in an age of irreligion, an age when religious beliefs and activity have decreased significantly from previous historical periods. Religion, according to this perspective, has lost its “presence” as a social force and has become less visible, less public, and less important in the lives of people (Yinger 1957; Glock and Stark 1965; Wilson 1978).

Much of the literature that builds upon this thesis adopts the view that the forces of modernization, urbanization, and industrialization have all contributed to a substantial trend toward secularization. [1] Peter Berger has defined secularization as that “process by which sectors of society and culture are removed from the domination of religious institutions and symbols” (Berger 1967, p. 107). He also notes that just “as there is a secularization of society and culture, so is there a secularization of consciousness. Put simply, this means that the modern West has produced an increasing number of individuals who look upon the world and their own lives without the benefit of religious interpretation” (1967, pp. 107–8).

It should be noted, of course, that the concept of secularization has multiple uses in the literature in addition to that of Berger. Campbell (1971), for example, discusses at least five of these in his work on the sociology of irreligion. Shiner (1967) has discussed six different uses of the concept of secularization in the literature. Our usage here would most closely parallel Shiner’s Types 1 and 4: a decline in religion or a transposition from sacred to secular explanations of events. It is recognized that this usage is a rather narrow one and that it fails to take into account either alternative uses of the concept or the more recent arguments that the so-called secularization of society is actually the ultimate triumph of “religion” (see Shiner 1967, p. 219; also Fenn’s 1978 discussion of the concept).

Typically, however, those who use the concept of secularization to refer either to a decline of religion or a transposition from sacred to secular modes of explanation view this as an irreversible process that accompanies modernization. It is seen as continuous, starting from some unspecified point in the past and proceeding irresistibly into the future. Its consequence has been the transport of modern mankind out of an age of faith into an age of practical reason (Caplow, Bahr, and Chadwick 1983).

One need not posit a linear trend, however. Martin (1978), among others, has argued that a theory of secularization need not assume that secularization is either a long-term or an inevitable process. Furthermore, in identifying some of the important ambiguities that surround the concept, Shiner (1967) has noted that in some historical periods, both the so-called religious and the so-called secular have risen to higher levels of intensity at virtually the same time (see also Hexter 1961).

A basic problem with the view that religion is on the decline appears when one begins to examine the actual empirical data. For example, one cannot spend much time with the literature on religious observance—at least as that occurs in the United States—without wondering about the reality of the supposed trend toward irreligion. Several years ago, Andrew Greeley described secularization as a myth (Greeley 1972). More recently, in describing some of the findings from their monumental restudy of Middletown, Caplow, Bahr, and Chadwick state:

The idea that religion is a vestigial institution destined to decline and eventually disappear persists among some contemporary sociologists—but is itself a vestige of theoretical positions they no longer hold. The 19th century confidence in the eventual triumph of reason in human affairs is long since gone. . . . Nevertheless, the dim view of religion that positivism held in its heyday lingers on. (Caplow, Bahr, and Chadwick 1983, p. 37)

The work of Caplow and his colleagues in Middletown provides virtually no support for the secularization hypothesis, at least as they conceptualized the term. The Middletown work takes on special significance because of the researchers’ ability to present longitudinal data and to compare their findings from the late 1970s with the work of the Lynds that was done in the 1920s and the 1930s. The careful comparisons of over half a century of change in Middletown provide virtually no support for the idea that religion is becoming a declining force in the lives of Middletown citizens. Nor do the Middletown findings stand alone. Wilson (1978, p. 410) observes: “That just under half the adult population in the United States is to be found in a place of worship at least once a week—more than at any time in the country’s history—makes it difficult to argue that America is a secularizing society.”

One of the key elements of the secularization thesis as used here is that the supposed decline in religion is directly linked with the rise of science (Weber 1946; Eliade 1961; Shiner 1967). The important beginning of this increased attention to “scientific” explanations is typically identified as the period of the Enlightenment—”a period when the faith in reason, with its empirical, pragmatic orientation to the world, began to replace faith in revelation or tradition” (Wilson 1978, p. 412). Religion was clearly a problem for the growing rationalism and positivism that were associated with the rise of science. Religious beliefs and practices were simply not seen as rational or scientific and, as a result, their very existence required some explanation (Campbell 1971, p. 8). Wilson further specifies the important role of science in this process as follows:

The growth of the scientific world view means that the natural (and, later, the social) world becomes the object of systematic scrutiny, for the purposes of which canons of procedure are agreed upon. . . . The scientific world view is largely incompatible with a belief that there are supernatural powers. Science is valued not only for its practicality but also for its universalism, impartiality, and skepticism. The contrast between religion and science is one of values as well as technique. (Wilson 1978, pp. 412–13)

A somewhat more contemporary effort to link secularization, with its emphasis on scientific, rational thought, with a decline in religion is found in the increasing amount of empirical work on the relationship between education and religiosity (see, for example, Zelan 1960; Stark 1963; Greeley 1964; Thalheimer 1965; Hoge 1974; Mobery and McEnry 1976; Hastings and Hoge 1976, 1981). The “academic mind” (Lazarsfeld and Thielens 1958), it is assumed, is antithetical to commitment to a religious world view. In discussing the more intellectually or academically oriented, Caplovitz and Sherrow (1977, p. 95) state:

The intellectuals are apt to manifest . . . three processes undermining religious identification. . . . They are committed to empirically based truth and suspicious of nonempirical “truths” that form the bases of religion (the secularization theory); they are apt to be alienated from the dominant values of society in that they view themselves as unconventional and . . . liberal, committed to higher values rather than to materialism . . . ; and, finally, they are more committed than most people to the values of universalism and achievement which are in opposition to positions based on the values of ascription and particularism, as is the case of religion. These attributes of intellectuals do not stem from relinquishing a religious identity . . . but rather they cause the shedding of a religious identity.

This view would be supported by the argument that it is difficult to hold simultaneously both a religious and scholarly orientation to the world. Lehman (1972), for example, found in his study of college and university faculty members, that scholarly and religious commitments tended to be almost mutually exclusive.

However, just as the link between modernization and irreligion is anything but clear, so is the relationship between education and religiosity problematic. Our purpose in this paper is to evaluate the growing body of data on the relationship between increased levels of education and the expression of religious attitudes and behavior. We will begin by reviewing evidence on both sides of this issue and then will conclude with a brief case study from our work on religiosity among Mormons.

The Negative Influence of Education on Religiosity [2]

Numerous studies have dealt with the question of the role of higher education on religious apostasy, and many of these studies have found the link to be a positive one. In their carefully written work on religious dropouts, Caplovitz and Sherrow (1977) provide strong evidence that there is an important strain between commitment to intellectual pursuits and commitment to religion and that the former tends to clearly undermine the latter. In their analysis, Caplovitz and Sherrow found that attending college did, indeed, increase the probability of apostasy. In addition, the type of college one attended was critical and had an impact on apostasy rates independent of other predisposing traits of the individual student. For example, highly religious students were largely impervious to the college environment. However, apostasy rates among those who were less committed were strongly related to the nature of the college environment. This was particularly true for Catholics. Catholics attending Catholic colleges seldom apostatized during their college years, whatever their predisposing qualities. However, Catholics attending secular colleges exhibited much higher levels of apostasy. It is also important to note that those who went on to postgraduate work following college graduation exhibited even higher levels of apostasy. Thus, the higher the education level, the greater the probability of apostasy.

Caplovitz and Sherrow (1977, p. 108) hypothesize several reasons for their findings:

In most colleges, students are exposed to ideas which seriously question fundamentalistic religious beliefs. . . . Furthermore, for most students college represents a departure from the family and incorporation into a peer culture. Familial influences which, we have seen, play an important role in sustaining a religious identification, are likely to decline when the student is away at college. The college peer group is typically a breeding ground for new ideas, new styles of thought and behavior.

There has been a long-standing debate in the literature regarding the direction of the causal relationship between apostasy and intellectualism (see, especially, Stark 1963; Zelan 1960, 1968; Greeley 1964; Lehman 1972; and Caplovitz and Sherrow 1977). Stark, along with Caplovitz and Sherrow, treats apostasy as the dependent variable and demonstrates how those committed to more intellectual lives show higher levels of apostasy from religion. [3] Zelan and Greeley argue that those who are bent toward apostasy are also bent more toward an intellectual life. For them, there is no fundamental strain between intellectuality and religion; some individuals are simply more prone to exhibit both qualities. Further, intellectualism for such individuals often replaces religious beliefs in providing meaning and purpose to life. Intellectualism, itself, is not the cause; it simply fills the gap created by other forces.

The most prevalent view in the literature, then, seems to be that educational achievement impacts negatively on religious commitment and that increased levels of education often lead to apostasy as individuals encounter views that deemphasize spiritual growth and elevate scientific and intellectual achievement. Argyle and Beit-Hallahmi (1975) summarize this view well in their extensive review of two decades ago. They conclude that there is a highly consistent trend towards a lower level of church attendance and a lower level of religious beliefs and attitudes with increases in educational levels. The higher the level of education, the less likely one is to be orthodox or fundamentalistic in one’s religious beliefs. In addition, the higher one’s educational level, the less likely one is to believe in God and to think of him as a person, the less favorable one is toward the church, and the less importance one attaches to religious values.

That things have not changed significantly since the Argyle and Beit-Hallahmi review can be seen from the data summarized in table 9.1. Data for this table have been compiled from a series of tables included in the recent Princeton Religion Research Center publication entitled Religion in America 1982 (1982). As can be seen from the table, the relationship between education level and religiosity is negative and linear on virtually all of the sixteen measures that were included. Only on the measure of attendance at church or synagogue are those with a college education likely to be as religiously active as those with lower levels of education. And, of course, there have been a variety of explanations for this developed in the literature as we shall note shortly.

|

Table 9.1: Education and Expressions of Religiosity |

|||

|

Educational Level |

|||

|

Measures of Religiosity |

% college |

% high school |

% grade school |

|

Attended church/ |

43 |

39 |

43 |

|

Church receives highest rating for meeting individual’s spiritual needs |

38 |

46 |

65 |

|

Evangelical experiences |

|||

|

Had “born again” experience |

27 |

39 |

39 |

|

Ever proselytize for Christ |

39 |

46 |

56 |

|

Believe in literal translation of Bible |

21 |

40 |

56 |

|

Reports living “a very Christian life” |

8 |

9 |

22 |

|

Watched religious programs on TV in last seven days |

21 |

33 |

47 |

|

Reads the Bible at least daily |

12 |

16 |

21 |

|

Prays |

80 |

91 |

92 |

|

Agrees that religion is most important influence in life. |

56 |

72 |

81 |

|

Constantly seeks God’s will through prayer |

51 |

69 |

86 |

|

Believes that God loves me though I may not always please him |

82 |

91 |

95 |

|

Receives a great deal of comfort from religious beliefs |

72 |

79 |

88 |

|

Completely or mostly believes in the divinity of Jesus |

74 |

87 |

94 |

|

Wishes faith were stronger |

68 |

80 |

87 |

|

Spiritual commitment very high |

6 |

11 |

25 |

|

Source: adapted from various tables in Religion in America 1982, the Princeton Religion Research Center, Inc., Princeton, New Jersey. |

|||

Contrary Evidence

While the majority view seems to be that higher education has a strong negative influence on religiosity, this view is not accepted by all. For example, Estus and Overington (1970) found that among Protestant church members, religious participation shows a small positive association with occupational level but is unrelated to educational level. Mueller and Johnson (1975), who focus on socioeconomic status more generally and not just on education, conclude that socioeconomic status is not a major determining factor in religious participation and that future research should be directed toward identifying more promising determinants.

Greeley’s (1964) position discussed earlier would also be consistent with this view. While he recognizes a correlation between religious attitudes and behavior and education level, Greeley argues that the causal arrow actually runs the other way. That is, one does not reject religion as a result of higher levels of intellectual attainment; rather, one may seek more intellectual pursuits as a consequence of already having rejected one’s religious faith.

As noted earlier, the recent completion of the volume on Middletown religion by Caplow, Bahr, and Chadwick (1983) also provides evidence refuting the negative effect of education on religion. These researchers found, apparently to their surprise, that the well-educated in Middletown were as committed in their religious worship as were the uneducated.

One of the most immediate problems we must deal with, of course, is operational. A cursory review suggests that on virtually all measures of the expression of religiosity except that of attendance at church or synagogue, the evidence strongly supports the belief that higher levels of education have a negative impact on religiosity. This is clearly evident from the recent Princeton study of religion in America and is not really contradicted by the work from Middletown. This leaves us to contend with the argument that much church attendance may actually be irreligious in nature, particularly among those of higher socioeconomic status (SES). That is, it is sometimes argued (see, for example, Stark 1963; Demerath 1965; and Marx 1967) that much religious participation is social in nature and is without any real commitment to what would typically be defined as a set of religious beliefs. Attendance at church, in other words, is simply another form of participation in a type of voluntary association such as a club, business association, and so on.

If this argument holds, then the contrary evidence showing a positive relationship between educational level and church attendance really does not become a basis for rejecting the thesis that intellectual pursuits, particularly as these are reflected in educational achievement, are parenthetical to maintaining a high degree of meaningful religious commitment.

A Mormon Case Study

Most analyses of the relationship between SES and religiosity treat all Protestants as a homogeneous group. Such highly aggregated analysis ignores important denominational differences both in levels of SES and religious participation, and may obscure the relationship between these variables (Davidson 1977).

The nature of the relationship between educational attainment and religiosity will be amplified by an examination of data we have developed in a large-scale study of members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Mormon).

Data collection for the Mormon survey was initiated in the summer of 1981. In the first phase, questionnaires were mailed to a random sample (n = 7446) of adults (aged eighteen and over) in the United States and Canada from a computerized membership list maintained at Church headquarters. A reminder postcard was sent out two weeks later. The response rate was 54 percent. The second phase involved asking bishops (local ministers) to send someone to interview respondents. An additional 5 percent return was achieved. The third step was to ask bishops to fill out as much of the information as they could, based on personal knowledge and membership records. This provided information on an additional 15 percent. Finally, an attempt was made to interview respondents by telephone yielding an additional 7 percent. Only 4 percent actually refused to participate, 1 percent had died or were no longer members of the LDS Church, and we were unable to locate 14 percent of the sample.

We suspect some bias in the reported frequency of religious participation since those who refused and those who were not located are probably less involved in the Mormon Church. Many in this group would probably not identify themselves as Mormons, however, implying comparability of our results with surveys which rely on denominational preference. Respondents were assured of confidentiality and, except for the 5 percent who were interviewed, local Church authorities had no access to completed surveys. Even with the interviews, interviewers were instructed to mail the questionnaires immediately after completion. These procedures probably reduced bias somewhat, but we are unable to detect how much remains because of Church auspices. Hopefully this bias would not appreciably alter the findings or conclusions.

Education and Religiosity among Mormons

From its very beginning, the Mormon Church has placed significant emphasis upon education. One result of this has been a standard of educational attainment that is significantly higher than the national average. Table 9.2 summarizes the number of years of school completed for Mormons and for the U.S. population more generally. For both males and females, the percentage of Mormons who have completed post-high school education is significantly higher than is the case for the population as a whole. For Mormon males, 53.5 percent have some post-high school education compared to 36.5 for the U.S. population. For females, the figures are 44.3 for Mormons and 27.7 for the U.S. population generally.

|

Table 9.2: Years of School Completed—Comparison Between U.S. Mormon Population and U.S. Total Population (Percent Distribution), by Sex |

||||

|

Years Completed |

Males |

Females |

||

|

U.S. |

Mormon |

U.S. |

Mormon |

|

|

0–11 |

30.7 |

15.3 |

31.8 |

16.4 |

|

12 |

32.8 |

31.2 |

40.5 |

39.3 |

|

13–15 |

15.6 |

25.0 |

14.1 |

28.6 |

|

16 or more |

20.9 |

28.5 |

13.6 |

15.7 |

To begin our examination of the relationship between educational level and religious participation, we can briefly compare Mormons with Catholics and members of other major Protestant denominations in terms of the relationship between education and church attendance (see table 9.3). Information for Mormons comes from the Demographic Study described above while information from other denominations is from the 1982 cumulative N.O.R.C. General Social Surveys.

For each religious group and for both males and females the relationship is positive. In some instances the relationship is very weak, but in others the pattern is very clear. Two general groups can be distinguished. Presbyterians, Episcopalians, and Mormons have very high educational attainment (over 50 percent of men and 40 percent of women have completed four or more years of college) while Catholics, Baptists, Lutherans, Methodists, and other Protestants have moderate or lower educational attainment (less than 40 percent of men and 30 percent of women have completed four or more years of college). The high education group is characterized by high correlations between education and attendance (.20 or greater), but the correlations are lower in the low education group (the average correlation is .08). Mormons are similar to Episcopalians and Presbyterians in terms of the correlation between education and attendance. Mormons are unique, however, in another important respect. Episcopalians and Presbyterians have lower overall attendance rates than the groups with lower education, but Mormons have the highest attendance rates of any group considered. Mormons with no college are not exceptionally high attenders, but Mormons with college experience have attendance rates notably higher than any other group. These differences underscore the necessity of disaggregating the analysis by denominations and point to Mormons as prime candidates for a case study.

|

Table 9.3: Percentage of Weekly Attenders by Education for Major Denominations |

||||||||

|

Level of Education |

||||||||

|

Males |

Females |

|||||||

|

0–11 |

12 |

13–15 |

16+ |

0–11 |

12 |

13–15 |

16+ |

|

|

Catholic |

37.8 |

39.7 |

42.8 |

52.8 |

50.6 |

55.9 |

53.1 |

60.0 |

|

(495) |

(466) |

(290) |

(265) |

(601) |

(807) |

(305) |

(170) |

|

|

Baptist |

26.4 |

40.0 |

27.4 |

52.0 |

37.6 |

47.1 |

48.4 |

54.7 |

|

Methodist |

24.0 |

19.5 |

20.9 |

23.4 |

32.5 |

34.7 |

39.8 |

39.5 |

|

(196) |

(220) |

(134) |

(116) |

(246) |

(325) |

(123) |

(109) |

|

|

Lutheran |

23.1 |

25.3 |

14.2 |

44.5 |

34.6 |

33.0 |

35.5 |

44.9 |

|

(156) |

(174) |

(70) |

(72) |

(185) |

(281) |

(90) |

(49) |

|

|

Presbyterian |

19.7 |

18.9 |

16.3 |

37.4 |

30.3 |

25.2 |

40.0 |

51.4 |

|

(66) |

(58) |

(74) |

(83) |

(76) |

(119) |

(75) |

(72) |

|

|

Episcopalian |

18.2 |

4.2 |

19.4 |

27.8 |

10.3 |

20.0 |

26.4 |

38.1 |

|

(21) |

(24) |

(31) |

(54) |

(29) |

(65) |

(53) |

(63) |

|

|

Other |

46.7 |

43.3 |

40.9 |

51.8 |

50.9 |

47.1 |

53.6 |

53.6 |

|

Protestant |

(261) |

(192) |

(105) |

(85) |

(242) |

(312) |

(123) |

(97) |

|

LDS |

43.9 |

43.4 |

64.3 |

77.3 |

48.9 |

53.5 |

70.9 |

78.9 |

|

(240) |

(793) |

(677) |

(660) |

(399) |

(1082) |

(842) |

(360) |

|

|

Attendance and Education Correlation |

||

|

Males |

Females |

|

|

Catholic |

.08* |

.06* |

|

Baptist |

.19* |

.10* |

|

Methodist |

.05 |

.10* |

|

Lutheran |

.13* |

.00 |

|

Presbyterian |

.22* |

. 21* |

|

Episcopalian |

.38 |

.23* |

|

Other |

.03 |

.10* |

|

LDS |

.26* |

.20* |

|

*P<.05 |

||

How do we explain these findings in light of the data from the Princeton Religion Survey presented in table 9.1? Two issues should be stressed. First, the data in table 9.1 are not broken out by religion. When that is done, a fairly strong relationship between educational attainment and church attendance is evident for some denominations while the relationship is practically nonexistent for others. Second, we must emphasize that the figures presented to this point deal with church attendance only and, as we have already noted, both the figures presented in table 9.1 and findings reported by other researchers suggest that this is the one measure of religiosity for which those with higher levels of education may exhibit higher scores—again, however, recognizing that attendance at church may occur for motivations that are not strictly (or perhaps even primarily) religious.

To address this second question for our Mormon population, we included a number of other indicators of religiosity in our questionnaire. Respondents were asked to report the amount of tithing that they contributed to the Church, they were asked the frequency of their engagement in personal prayer, they were asked to report the amount of time spent in religious study, and they were asked to report how important their religious beliefs were to them. In other words, three behavior measures, in addition to church attendance, were used, along with one belief measure. The results for different educational attainment groups are reported in table 9.4.

As noted in the previous table, the data indicate a strong positive relationship between educational level and attendance at meetings. For males, 34 percent of the respondents with just a grade school education report weekly attendance. This increases to 71 percent of the males who are college graduates and 80 percent of those who have had graduate school training. The relationships for females are similar with the percentage of weekly attenders increasing from 48 percent of those with a grade school education to 82 percent of those with the college degree. Attendance drops slightly, however, for females who go beyond the college degree. In all categories except for those with post-graduate education, the attendance level is higher for women than it is for men. However, post-graduate men are more likely to attend on a weekly basis than are post-graduate women.

|

Table 9.4: Relationship between Education and Religiosity Indicator |

||||||||||||

|

Percent weekly Attendance |

Percent Full Tithing |

Percent Daily Prayer |

Percent Gospel Study |

Percent Beliefs Important |

Number |

|||||||

|

M |

F |

M |

F |

M |

F |

M |

F |

M |

F |

M |

F |

|

|

Grade School |

34 |

48 |

40 |

50 |

52 |

72 |

3 |

56 |

71 |

95 |

94 |

102 |

|

Some High School |

48 |

52 |

51 |

48 |

44 |

61 |

37 |

45 |

75 |

82 |

181 |

265 |

|

High School Graduate |

43 |

54 |

42 |

49 |

44 |

58 |

37 |

11 |

70 |

85 |

620 |

919 |

|

Some College |

65 |

71 |

57 |

59 |

54 |

63 |

46 |

53 |

81 |

88 |

620 |

795 |

|

College Graduate |

71 |

82 |

68 |

73 |

60 |

75 |

48 |

52 |

81 |

93 |

241 |

205 |

|

Graduate School |

80 |

76 |

71 |

73 |

68 |

62 |

61 |

48 |

87 |

83 |

377 |

131 |

|

Correlation |

.24* |

.20* |

.22* |

.14* |

.15* |

.02 |

.17* |

.04 |

.12* |

.02 |

||

|

*P<.05 |

||||||||||||

The pattern is similar for tithing status. Forty percent of the men with grade school educations report paying a full tithing. This increases to 71 percent of the men who have had graduate school training. For women, half of those with grade school educations report a full tithing, and this increases to 73 percent of those with a college degree or with post-graduate training. Women with just grade school educations are slightly more likely to pay a full tithing than are women in the next two higher education categories. Again, women report slightly higher levels of performance for all educational categories except for those with some high school education.

Responses on the personal prayer measures are somewhat different for the different educational categories. Men who have graduated from college or completed post-graduate programs are more likely to pray than men in the other educational categories. However, men with just a grade school education are more likely to pray regularly than are those in the next two higher educational categories. For women, the two groups that are most likely to report daily prayer are the women who have completed college and those with grade school educations. Those least likely to report daily prayer are the high school educated. For all educational categories except graduate school, women are more likely to report daily prayer than are men.

The religious study variable is again somewhat unique. While men with post-graduate training are the most likely to report one or more hours of religious study per week, grade school educated women study more than any other group of women. And the women with post-graduate education are among the least likely to indicate one or more hours of religious study per week. In all of the educational categories, however, women are more likely to report regular study than men except for those with post-graduate training. In this case, men are more likely to study regularly.

Just as is true with the behavioral measures. Mormon men with higher levels of education report that their beliefs are stronger than those with lower levels of education. A positive association is also present for women in the middle range of education, but women who have completed some post-college graduate study are again low while those with only a grade school education score high on belief.

Our findings show, then, a strong positive relationship between educational attainment and a variety of religious behavior and belief indicators for Mormon men. The relationship between education and attendance or tithe paying is positive for women, but no clear pattern emerges with prayer, gospel study, or belief. Nevertheless, women with college experience are more likely to report religious involvement than women with only a high school education. Overall, higher levels of education support rather than obstruct or discourage religiosity for Mormons.

Discussion

How can we explain the important differences that we have observed between our Mormon data and that generally reported in the literature for other religious denominations? Education simply does not appear to have a secularizing influence on either religious attitudes or importance of beliefs for our sample. While the supposed secularizing influence of higher education may be helpful in understanding the lower overall attendance rates in higher education denominations, as reported in table 9.3, it cannot explain the positive association within each denomination and is certainly inapplicable to both attendance and other expressions of religiosity of highly educated Mormons.

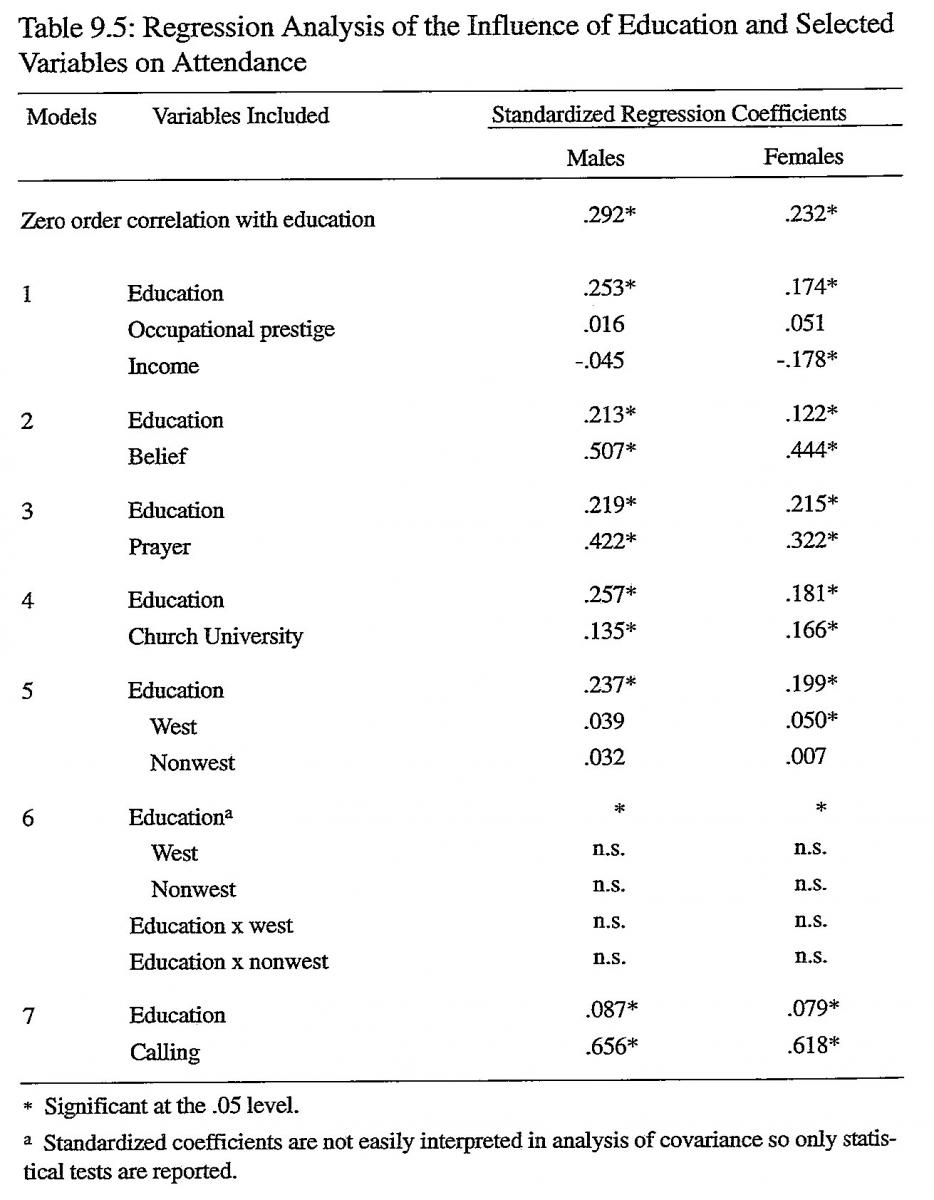

We have also discounted the status attainment explanation for Mormons. First, status attainment is applicable primarily to those public expressions of religiosity such as church attendance. It is less applicable to private expressions such as religious study, prayer, and belief. On all of these indicators the relationship between educational level and religiosity remains strong. Second, if the status enhancement hypothesis is correct then it should also apply, perhaps even to a greater degree, to other measures of social standing such as occupation and income. If all three variables are entered in a regression equation to predict attendance rates of men, the coefficients are .016 for occupational prestige, –.045 for income, and .253 for education; for women coefficients are .051, –.178, and .174 respectively (see table 9.5). Occupation does not have a large influence; the income effect is, in fact, negative, and education still has a positive influence. These results imply that the status enhancement hypothesis is not very useful in understanding attendance, at least among Mormons.

A third explanation, closely related to the second, is that religion means different things to different social classes. The lower classes, it is sometimes argued, place more emphasis on doctrine and on their relationship with God, whereas the upper classes are more concerned with the social and humanistic aspects of religion. Information available in the demographic survey is insufficient to examine this hypothesis in any detail but, as we have discussed, education is positively associated with other measures such as prayer and strength of religious beliefs. Statistically controlling for belief or prayer has little effect on the relationship between education and attendance (see models 2 and 3 of table 9.5). Highly educated Mormons are more likely to pray frequently, to have strong religious beliefs and to attend meetings, suggesting that devotion is even more important for those with higher levels of education than those with lower educations.

Yet another possible explanation is that many Mormons who have received higher levels of education may have received that education at institutions like Brigham Young University, Ricks College, or BYU-Hawaii where their commitment and belief are strongly supported by the nature of their educational experience. We have already noted that the nature of the college one attends may have a strong impact on the degree to which that college experience has a secularizing influence (see, especially, Caplovitz and Sherrow 1977). Our analysis gives some support to this explanation. Those who have attended a Church university have very high attendance rates. Almost 90 percent report weekly attendance, ranking them ten to twenty percentage points higher than those who did not go to a Church university. Even so, this latter group has higher attendance than those who did not go to college, and their rate increases the more years of college they complete. Adding a dummy variable for attendance at a Church university does reduce the education coefficient somewhat, but it is still positive and statistically significant (model 4, table 9.5). People with college experience are more likely to attend meetings whether or not they went to a Church university. Thus, education has a significant effect over and above the socializing influence of Church colleges.

A corollary of this explanation relates to geographical location of the respondent. Utah, of course, is the heartland of Mormonism and the culture there is permeated with religious influence. It might be suggested that the secularizing influence of education might be greater outside the heartland where Mormon influence is not pervasive. Moreover, those intellectuals who feel uncomfortable with the religious milieu may move out of Utah. Thus, the relationship between education and attendance would vary depending on region of residence. To test this possibility we identified three regions of influence. Utah is clearly the center where Mormonism is the dominant influence. In other western states there are pockets of Mormon settlements and fairly large concentrations in major urban centers along the Pacific Coast. This area might be called the semi-periphery. The third region includes all states east of the Rocky Mountains where Mormons are generally a small minority. Inclusion of two dummy variables representing the west and nonwest can only account for a small share of the education-attendance relationship (model 5, table 9.5). Moreover, analysis of covariance indicates that the relationship between education and attendance is not significantly different in these regions for either men or women (model 6, table 9.5). Educational attainment and religious involvement are compatible in the peripheral as well as the core areas of Mormon culture.

A final explanation to be considered focuses on the importance of the lay-clergy in the Mormon Church. O’Dea (1957) suggested many years ago that the negative relationship between religiosity and higher education may be attenuated within the context of Mormonism because the educated are selected into positions of leadership where they administer the church programs. He argued that this status and responsibility makes compartmentalization of scientific and religious attitudes somewhat easier. The idea in the Mormon Church is for every capable member to have a calling. Successful performance in these callings requires a great variety of skills including things like bookkeeping, teaching, organizational management, and interpersonal relations. Some of these skills are acquired through the educational system. All else being equal, we would expect education to be positively associated with acquisition of these types of skills. As a result, people with more education may be among the first to be considered for any given calling, and they may also have greater success in their callings. Since success in one’s calling is such a central aspect of church participation, the link between education and participation comes as no surprise. Education has a higher correlation with having a calling (r = .31 for men and .25 for women) than with attendance. Moreover, if education and having a calling are both used to predict attendance, then the education effect is reduced to .09 for men and .08 for women or about one-third of the total effect (model 7, table 9.5). Thus, it appears that having a calling is a key link between education and attendance. On the other hand, the attenuating effect of a calling on other measures of religiosity is much less evident. The relationship between educational level and high scores on these measures remains important, even when controlling for whether or not one has a calling. [4]

For our Mormon sample, then, we find virtually no evidence to support the hypothesis that education has a secularizing influence. For Mormon men, the higher the level of education, the higher one’s level of religious observance. A critical point in our findings is that this holds for several measures of religiosity, in addition to that of attending religious services. This discounts the idea that much church attendance on the part of those of higher SES is actually motivated by social as opposed to religious reasons—attendance among Mormon men is strongly related to a variety of other measures of religiosity. The same findings hold generally for Mormon women. The one important exception is that Mormon women who continue their education beyond college graduation do show a slight decline on all our measures of religiosity. Whether this is a function of a secularizing influence of education or other forces is a question that we are unable to address with the data currently available.

References

Argyle, Michael and Benjamin Beit-Hallahmi. 1975. The Social Psychology of Religion. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Berger, Peter L. 1967. The Sacred Canopy: Elements of a Sociological Theory of Religion, edited by David G. Bromley. Garden City, NY: Doubleday.

Campbell, Colin. 1971. Toward a Sociology of Irreligion. London: Macmillan.

Caplovitz, David and Fred Sherrow. 1977. The Religious Drop-Outs: Apostasy among College Graduates. Beverly Hills: Sage.

Caplow, Theodore, Howard M. Bahr, and Bruce A. Chadwick. 1983. All Faithful People: Change and Continuity in Middletown’s Religion. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Davidson, James D. 1977. “Socio-Economic Status and Ten Dimensions of Religious Commitment.” Sociology and Social Research 61:462–85.

Demerath, Neil J. III. 1965. Social Class in American Protestantism. Chicago: Rand McNally.

Eliade, Mircea. 1961. The Sacred and the Profane. New York: Harper Torchbooks.

Estus, Charles W. and Michael A. Overington. 1970. “The Meaning and the End of Religiosity.” American Journal of Sociology 75:760–81.

Fenn, Richard K. 1978. Toward a Theory of Secularization. Storrs, CT: Society for the Scientific Study of Religion, University of Connecticut.

Glock, Charles Y. and Rodney Stark. 1965. Religion and Society in Tension. Chicago: Rand McNally.

Greeley, Andrew. 1963. Religion and Career. New York: Sheed and Ward.

———. 1964. “Comment on Stark’s ‘On the Incompatibility of Religion and Science.’“ Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 3:239–40.

———. 1972. Unsecular Man: The Persistence of Religion. New York: Schocken.

Hastings, Phillip K. and Dean R. Hoge. 1976. “Changes in Religion among College Students. 1948–1974.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 15:237–49.

———. 1981. “Religious Trends among College Students, 1948–1979.” Social Forces 60:517–31.

Hexter, J. H. 1961. Reappraisals in History. New York: Harper Torchbooks.

Hoge, Dean R. 1974. Commitment on Campus: Changes in Religion and Values over Five Decades. Philadelphia: Westminster.

Lazarsfeld, Paul F. and Wagner Thielens Jr. 1958. The Academic Mind. Glencoe, IL: Free Press.

Lehman, Edward C. Jr. 1972. “The Scholarly Perspective and Religious Commitment.” Sociological Analysis 33:199–216.

Martin, David. 1978. A General Theory of Secularization. Oxford: Blackwell.

Marx, Gary T. 1967. Protest and Prejudice. New York: Harper Torchbooks.

Moberg, David O. and Jean N. McEnry. 1976. “Changes in Church-Related Behavior and Attitudes of Catholic Students, 1961–1971.” Sociological Analysis 37:53–62.

Mueller, Charles W. and Weldon T Johnson. 1975. “Socioeconomic Status and Religious Participation.” American Sociological Review 40:785–800.

O’Dea, Thomas F. 1957. The Mormons. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

———. 1982. Religion in America, 1982. Princeton, NJ: Princeton Religion Research Center.

Shiner, Larry. 1967. “The Concept of Secularization in Empirical Research.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 6:207–20.

Stark, Rodney. 1963. “On the Incompatibility of Religion and Science: A Survey of American Graduate Students.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 3:3–20.

———. 1972. “The Economics of Piety: Religious Commitment and Social Class.” Pp. 483–503 in Issues in Social Inequality, edited by Gerald W. Thielbar and Saul D. Feldman. Boston: Little, Brown.

Thalheimer, Fred. 1965. “Continuity and Change in Religiosity: A Study of Academicians.” Pacific Sociological Review 8:101–8.

Weber, Max. 1946. “Science as a Vocation.” Pp. 129–56 in Essays in Sociology, edited by H. H. Gerth and C. Wright Mills. New York: Oxford University Press.

Wilson, John. 1978. Religion in American Society: The Effective Presence. Engle-wood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Wuthnow, Robert and Charles Y Glock. 1973. “Religious Loyalty, Defection, and Experimentation among College Youth.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 12:157–80.

Yinger, John Milton. 1957. Religion, Society and the Individual: An Introduction to the Sociology of Religion. New York: Macmillan.

Zelan, Joseph. 1960. “Correlates of Religious Apostasy.” University of Chicago, Chicago. Unpublished manuscript.

———. 1968. “Religious Apostasy, Higher Education, and Occupational Choice.” Sociology of Education 41:370–79.

Notes

[1] It should be noted at the outset that our primary interest in this paper is not in secularization per se but, rather, in the effect of increased levels of education on the expression of one’s religiosity. Nevertheless, since many of the usages of the concept of secularization link this so-called process with increases in levels of education and, particularly, with the rise of science, we will begin with a brief overview of the concept.

[2] We must recognize, of course, that the concept “religiosity,” like that of secularization, has many different meanings and uses. Attendance at religious services is a common beginning point in much of the literature. Church attendance, however, is only one of several behavior indicators of religiosity, and there are numerous attitudinal or belief indicators as well. Here we will treat the concept as multi-dimensional, having expressions both at the behavioral as well as at the belief level.

[3] Stark’s position on this issue has been somewhat modified in a more recent paper (Stark 1972). In this later analysis Stark concludes that religious involvement is positively related to social class and, more particularly, to educational level.

[4] It has been pointed out by at least one reviewer that another potentially important intervening variable is college major. It may be that those who specialize in fields like business, medicine, and law are less affected than those who specialize in the social sciences, humanities, or art. Unfortunately we are unable to assess this question with the data at hand. We are also unable to control for level of participation in non-religious voluntary organizations since data on this issue were not obtained.