Religiosity and Delinquency among LDS Adolescents

Bruce A. Chadwick and Brent L. Top

Bruce A. Chadwick and Brent L. Top, “Toward a Social Science of Contemporary Mormondom,” in Latter-day Saint Social Life: Social Research on the LDS Church and its Members(Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1998), 499–524.

Bruce A. Chadwick is professor of sociology at Brigham Young University. Brent L. Top is associate professor of church history and doctrine at Brigham Young University. This article was originally published in Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 32:51–67; reprinted with permission.

Abstract

This study tested the religious ecology hypothesis that postulates that religion is negatively related to delinquency only in a highly religious climate. Data were collected from a sample of 2,143 LDS youth living along the east coast during the spring of 1990. The link between religion and delinquency in this low-LDS religious climate was compared to the connection found in an earlier study of three highly moral communities, southern California, Idaho, and Utah. The religious ecology hypothesis was not supported; religiosity had a strong negative relationship to delinquency in both the high and low religious ecologies. In addition, a multivariate model allowed peer, family, and religious factors to compete to explain delinquency. The multivariate model revealed that although peer influence made the strongest contribution in the regression equation, religiosity also made a significant contribution.

Introduction

This study tested the relationship of several dimensions of religiosity, family characteristics, and peer influences to delinquent behavior with a sample of adolescent members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Mormons). An earlier study by one of the researchers discovered that religiosity had a significant, negative relationship to delinquency among LDS youth living in Southern California, Idaho, and Utah (Albrecht et al. 1977). It has been suggested by Stark, Kent, and Doyle (1980) and by Stark (1984) that this relationship materialized because a supportive religious climate in these predominantly LDS communities reinforced both religious practices and nondelinquent activities.

The first objective of this study was to test whether a supportive religious environment is a necessary condition for religiosity to be related to lower occurrences of delinquency among LDS youth. To do this we collected information from LDS adolescents living along the east coast of the United States, a non-LDS environment, and compared the results to those found in the earlier California-Idaho-Utah study.

Our second objective was to test the strength of religiosity’s relationship to delinquency in comparison to (a) example and pressure from friends, and (b) family characteristics. Generally peer influence and family life have been considered more important than religion in explaining delinquency (Tittle and Welch 1983; Elifson et al. 1983; Burkett and Warren 1987). The relative strengths of these three factors were determined using multiple regression in which indicators competed to enter the regression equation.

Religion and Delinquency

It has long been assumed by clergymen, church members, and some social scientists that religious beliefs and church attendance are effective deterrents to delinquent behavior. It has been argued that religious beliefs are the foundation for moral behavior. Thus, the more religious a person is, the less likely he or she will be to participate in delinquent or criminal behaviors (Durkheim 1915; Davis 1948; Coogan 1954; Yinger 1957). It is claimed that the multiple and diverse functions of religion in a person’s life make it an effective personal control against deviant behavior (Rohrbaugh and Jessor 1975).

These assumptions were seriously challenged in the 1960s by researchers who failed to confirm that religion deterred such behavior. Hirschi and Stark (1969) found that adolescents who attended church were “no more likely than non-attenders to accept ethical principles.” They also found that church attendance was “unrelated to the commission of delinquent acts, while those variables strongly related to delinquency are unaffected by church attendance” (p. 202).

Some investigators have even argued that religion not only fails to deter delinquency but might actually contribute to it (Lunden 1964; Bonger 1969). Schur (1969, pp. 85–86) has asserted that organized religion might “be held partly responsible for the magnitude of the American crime problem—through its frequent support for translating standards of private morality into criminal laws.”

During the 1970s and 1980s several studies using more sophisticated methodologies and statistical analysis produced mixed results. We will not review all of these studies in this paper, because several good reviews are available (Tittle and Welch 1983; Ellis 1985). The general conclusion is that religion has a rather limited relationship to delinquency.

Religious Ecology

In the early 1980s, Stark and associates (1980) felt that they had discovered the reason for the contradictory findings obtained in earlier studies linking religion and delinquency. The “key to unlock the mystery” of the unreliable relationship was “ecological conditions, namely, the religious climate” of the community. In their view, religion is negatively associated with deviance only when it is part of widely accepted social values and norms prohibiting such behavior. They reviewed two previous studies (Empey and Erickson 1972; Hindelang et al. 1981) and assessed the moral climate in the two communities where the data were collected. Provo, Utah, had a very powerful religious ecology, since 966 of every thousand residents were church members. On the other hand, Seattle, Washington, had a weak religious community, since the rate of church membership was only 280 per thousand. Support for the ecological explanation was discovered, for the relationship between church attendance and delinquency was significant in Provo, while it was so weak as to be of little importance in Seattle. Similar analysis using a national data set from high school seniors found that church attendance, religious values, and religious salience were related to lower rates of delinquency (Bachman 1970). Stark et al. (1980, p. 14) concluded that moral communities are the norm across the country and that “for the nation as a whole, religion serves to undergird the moral order.”

Stark (1984) stressed that if religion is conceptualized as a psychological trait that produces fear and guilt over deviance, its relationship to such behavior is problematic. On the other hand, he argued that if we conceptualize religion as a social or group characteristic, i.e., “the majority of an adolescent’s friends are religious,” then its relationship is robust.

The empirical studies that followed Stark’s and his associates’ initial work didn’t support the ecological hypothesis. Tittle and Welch (1983) conducted a study of delinquent and criminal behavior of 1,993 individuals over the age of fifteen years residing in New Jersey, Iowa, and Oregon. This study was somewhat unusual in that it asked respondents the likelihood that they would commit specific delinquent or criminal acts in the future, rather than how often they had committed them in the past. This allowed the researchers to specify a clear time sequence in the link between current religion and estimations of future deviance. The results did not support the ecological hypothesis. It was found that religion had a stronger relationship to deviant behavior when there was normative ambiguity, low social integration, perceptions of low peer conformity, and a relatively high proportion of people who were not religious. These findings suggest that religiosity has its greatest effect on adult deviance in a secularized and disorganized social context because the other social mechanisms that foster conformity are absent.

Bainbridge (1989) also discovered that the influence of religion on deviant behavior was not reduced by social or moral cohesion. He correlated the rate of church membership to the rates of selected crimes, homosexuality, and suicide in seventy-five metropolitan areas. When statistical controls for social integration were introduced, the relationship between church membership and suicide and homosexuality disappeared as expected. Yet even when such controls were included, church membership maintained a relationship to crime, especially violent crime.

Using data collected in the mid-1970s, Cochran and Akers (1989) tested five competing hypotheses relating religiosity to adolescent substance abuse. Examining the responses of over three thousand seventh- to twelfth-grade students attending school in three midwestern states, they found no support for the moral community hypothesis. The percentage of the student body that belonged to a church was not related to the level of substance abuse within the school.

On the other hand, a recent study by Welch and associates (1991) supported the ecological theory. They tested the moral community hypothesis with a national sample of adult Catholics. Information about the possibility of cheating on their income tax, excessive drinking, and using company equipment for personal use was collected from a sample of 2,667 adult Catholic members. The researchers argued that using a self-estimated probability of committing the three deviant acts would provide a better test of the hypothesis than would using self-reported past behaviors. This procedure did solve the problem of whether the religiosity preceded the deviance or vice versa. However, there remain nagging doubts about whether people predict with any degree of accuracy how they will behave in a stressful situation like being caught between “a strong need” and opposing religious values. The concern over whether past acts or anticipated future deviance is better for testing this hypothesis might be unnecessary, since the authors acknowledged that there is a strong correlation between reported past behavior and future intentions. Religiosity was determined by how frequently the respondent read the Bible, watched religious TV programming, listened to religious radio programming, and held family prayer. The level of moral community was assessed by the aggregate level of religiosity in each parish. It was discovered that in a strong religious community context, private religiosity was related to lower occurrences of self-projected deviant behavior.

The inconsistent support discovered for the religious ecology explanation justifies additional exploration of whether religion’s relationship to delinquency is a function of social cohesion or whether religious beliefs and values are related to such behavior, independent of the moral ecology. The present study collected data about religiosity and delinquency from a sample of LDS teenagers living in a very weak LDS moral climate. The results were then contrasted to those obtained in a previous study of LDS adolescents in a highly moral climate which had found a significant relationship between religiosity and delinquency (Albrecht et al. 1977). Comparing the results obtained from these two samples of LDS teenagers living in different moral climates furnished valuable insight concerning whether the relationship between religion and delinquency was a manifestation of social cohesion or whether the young people had internalized religious values related to their behavior regardless of the moral environment.

Peers, Family, Religion, and Delinquency

In previous studies, when religion has competed with peer pressures and family characteristics to explain delinquency, it has generally dropped out of the analysis. For example, Elifson et al. (1983) interviewed a sample of nearly six hundred high school students in Atlanta, Georgia, and found that when peer influences were included in the model, religion was insignificant in predicting delinquency. The general conclusion has been that in multivariate models religion has marginal value for explaining delinquency.

To test the relationship between peers and religion, we included four measures of peer influence in this study. We measured how often the respondent thought his or her friends engaged in delinquent activities, how often friends pressured the respondent to participate in such behavior, the level of friends’ disapproval of delinquency, and whether such disapproval was a deterrent for the respondent.

Tittle and Welch (1983) have noted that religion, especially for youth, is strongly intertwined with family characteristics such as family structure, family religiosity, and the bonds between parents and children. Rhodes and Reiss (1970) have tested the notion that parents’ religiosity is important in predicting their children’s religiosity and delinquency. They obtained questionnaires from over twenty thousand junior and senior high school students in the Nashville and Davidson County, Tennessee, school systems and matched them to juvenile court records. It was discovered that parental participation in religious activities had a significant, negative relationship with children’s delinquent activity.

Parental attitudes toward use of drugs and parental use of drugs, along with several measures of religiosity, were included in a multivariate model predicting the drug use of 1,358 public school students in the Brazo Valley of Texas (McIntosh et al. 1981). McIntosh and associates also added to the regression equation a measure of how close the adolescents felt to their mothers and fathers in order to test whether the association between delinquency and parental behavior was enhanced by the parent-child bond. Not surprisingly, they found that young people whose parents were users had higher levels of drug use themselves. On the other hand, the closeness of the adolescent to his or her parents did not contribute much to the prediction of drug use.

We included in our regression model the following: family structure (single- versus two-parent family); perceived quality of parents’ marriage; family size; maternal employment; socioeconomic status; closeness to mother and to father; parental disapproval of delinquent activities; and whether perceived parental disapproval was a deterrent to such behaviors.

Methodology

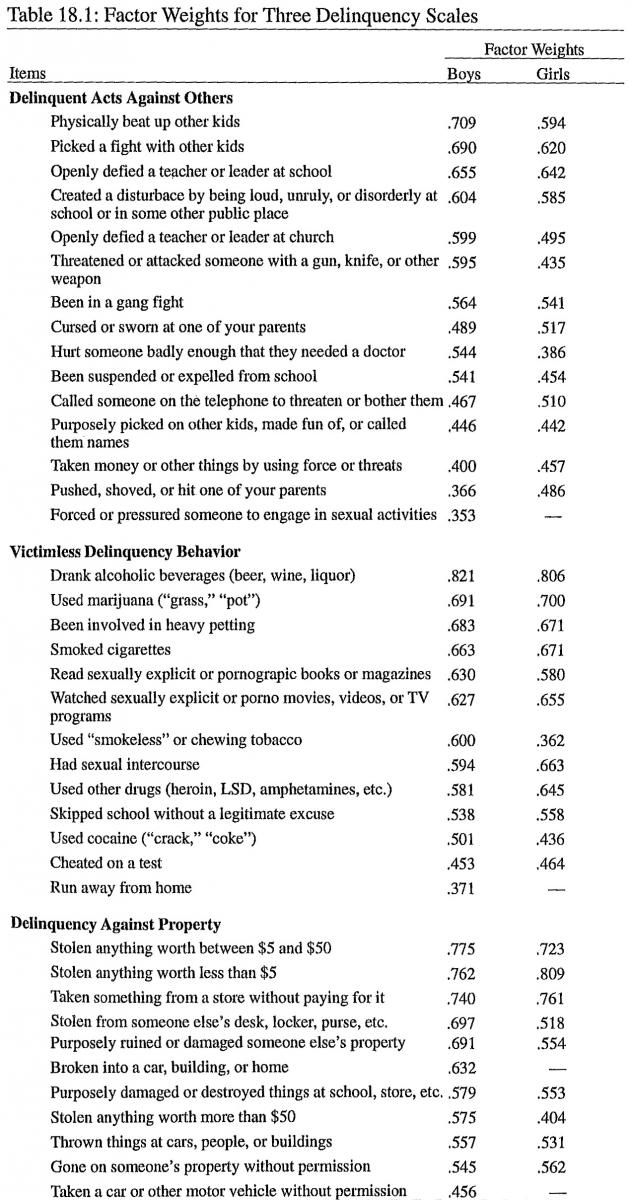

Previous research has discovered that religion has a somewhat stronger relationship to victimless delinquent activities than to crimes against people or property (Burkett and White 1974; Albrecht et al. 1977; and Elifson et al. 1983). This study focused on three different types of delinquent behaviors. Victimless offenses included drinking alcoholic beverages, taking drugs, exposure to pornography, and premarital sexual behavior. How often respondents attacked their parents, teachers, and other teens were used as measures of offenses against others. Finally, shoplifting, theft, and vandalism were treated as indicators of offenses against property.

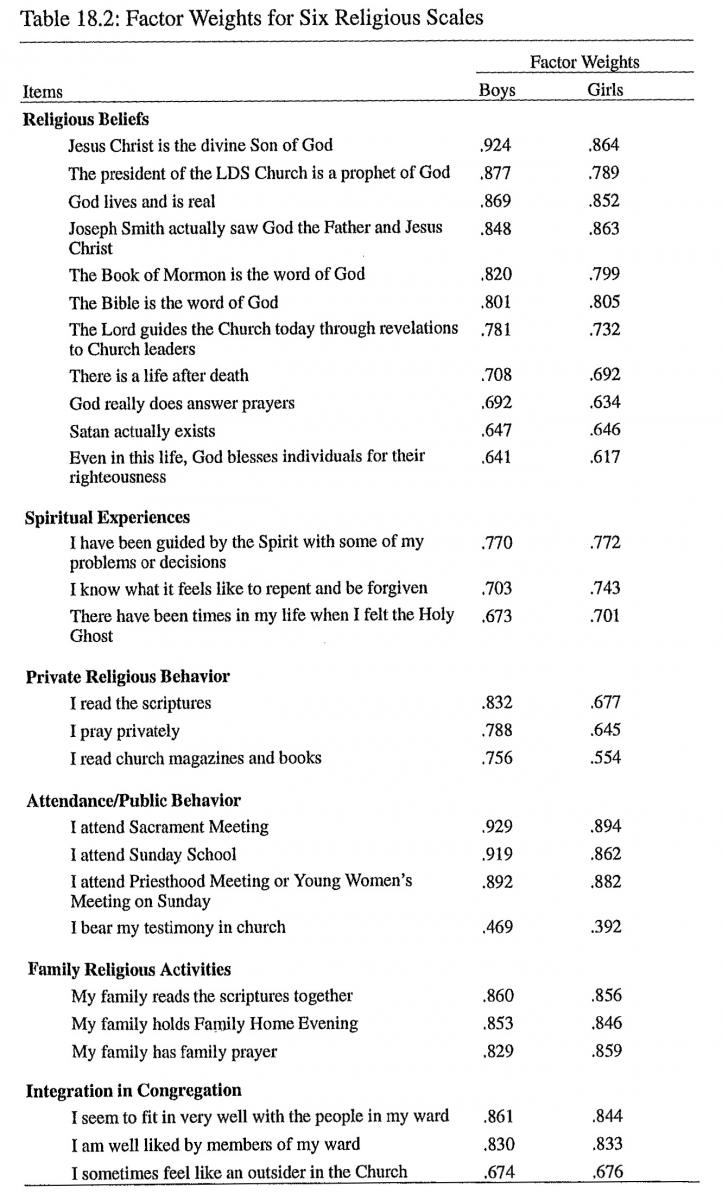

Most previous studies testing the relationship between religion and delinquency have used single measures of religiosity such as affiliation or attendance. Recent research has noted that religiosity contains several different dimensions that might have unique relationships to delinquency (Cornwall et al. 1986). To provide a more adequate test of the relationship between religion and deviant behavior, we included several measures of religiosity, including religious beliefs, private religious behaviors, spiritual experiences, public religious behaviors, family religious practices, and feelings of integration into a church congregation.

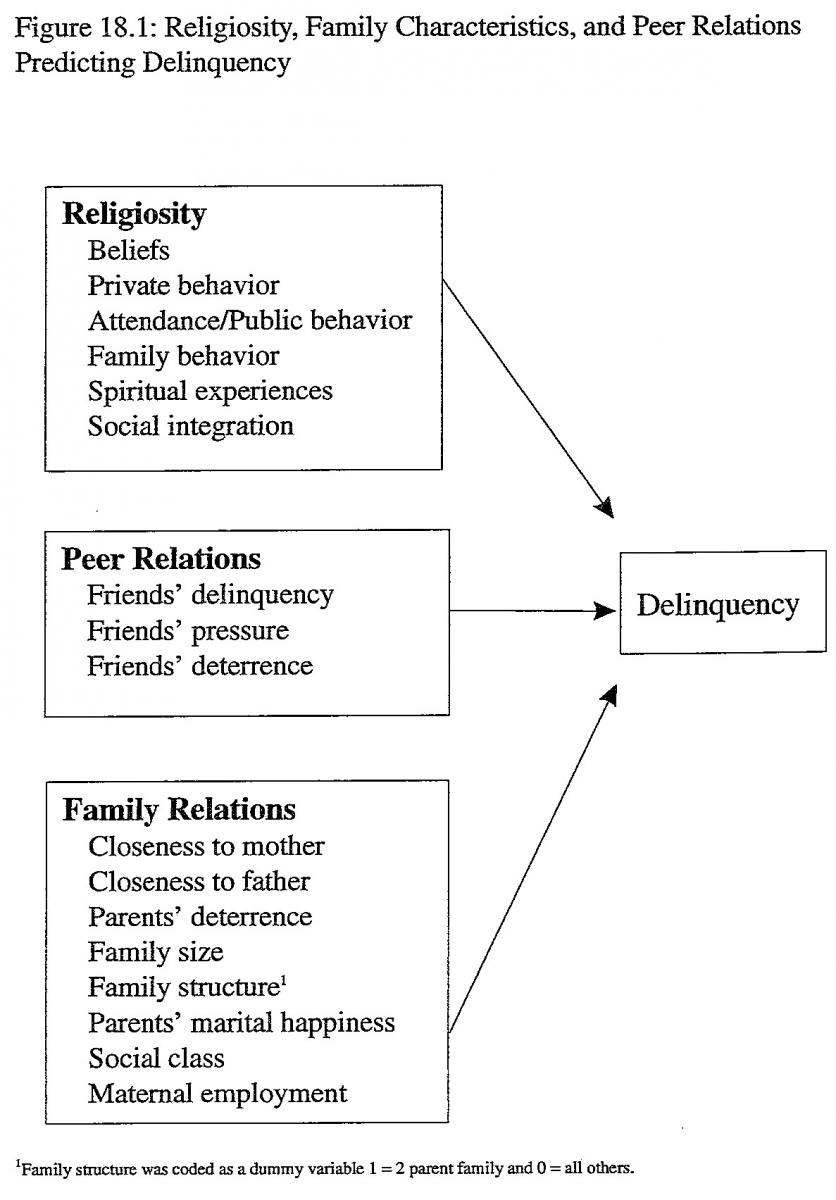

In this study we tested the multivariate model presented in fig. 18.1, which includes several measures of peer and family characteristics as well as different dimensions of religiosity to predict delinquent activities.

Data Collection

A mail questionnaire survey was conducted in the spring of 1990 with a sample of 2,143 LDS teenagers between the ages of fourteen and nineteen years living in Delaware, New York, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Virginia, Washington, D.C., and West Virginia. These young people were enrolled in LDS seminary (religious instruction classes that generally meet early in the morning before public school or during a weekly class). One of the authors served three years as a coordinator of seminary in Virginia and observed that most LDS teenagers (over 95 percent) were enrolled in seminary, regardless of their church activity. Thus the sampling frame included nearly all LDS youth in the area.

A packet was sent to the parents of the young people with a letter explaining the study and asking permission for their children to participate. Parents were informed that the questionnaire asked about sensitive behavior such as drug use and sexual activity. If parents did not want their children to complete the questionnaire, they were encouraged to return their mailing labels with the promise that they would not be bothered with any follow-up mailings. Surprisingly, we did not receive a single refusal. Parents were instructed to give the letter and questionnaire to their children, and it was stressed that if meaningful data were to be collected, they would have to allow their children to fill out the questionnaire in complete privacy. The letter to the young people also emphasized the need to fill out the questionnaire by themselves. A business reply envelope was enclosed.

A postcard reminder was mailed approximately three weeks later. One month after the postcard, a new packet was sent, including letters, questionnaire, and return envelope. A final approach was made one month later with another full packet. The letters were modified for the subsequent contacts. These procedures produced 1,398 completed questionnaires, a 67 percent response rate.

Measurement of Variables

Delinquent behavior was measured by forty-four items that asked whether the respondent had ever engaged in certain specific activities and, if so, how often he or she had ever done each. Sixteen questions that focused on drug and alcohol use as well as premarital sexual activity measured victimless offenses. An eleven-item scale gauged property offenses such as shoplifting, theft, and vandalism. Sixteen items involving attacks on parents, school officials, and other teens measured offenses against others.

As mentioned earlier, we included six dimensions of religiosity in the questionnaire. Religious beliefs were measured by eleven questions examining traditional Christian beliefs as well as belief in unique LDS doctrines. Three items asking about frequency of personal prayer, reading of the scriptures, and payment of tithing, assessed private religious behavior, and four questions about attendance at various meetings tapped public religious behavior. Three questions probed the degree of spiritual experience. Family religious behavior was determined by three questions about the frequency of family prayer, family scripture study, and family home evening. Three items that asked how well the respondents felt they fit into their congregations and were accepted by fellow church members determined feelings of religious integration.

Family structure, number of siblings, maternal employment, and perceived happiness of parents’ marriage were each measured by a single question. Closeness to father and to mother were each gauged by a four-item scale probing the parent-child relationship. Parental disapproval of delinquency was measured by asking the young respondents how they thought their parents would feel if they engaged in eight activities: lying or cheating, fighting, stealing, vandalism, premarital sex, using drugs, and drinking alcoholic beverages. Parental deterrence indicated whether respondents regularly did any of the seven activities, and, if not, whether parental disapproval was a reason.

Information about four dimensions of peer influences was collected. First, friends’ delinquency was determined by the respondent’s perceptions that his or her friends engage in the forty-four delinquent activities, and friends’ pressure by the frequency that friends had “tried to get” the respondent to participate in each of the behaviors. Friends’ disapproval focused on the respondent’s perceptions of how their friends felt about the seven delinquent activities mentioned above. Finally, friends’ deterrence was assessed by whether friends’ influence was a reason for why the respondent refrained from such behavior. Sex of the respondents was asked and used as a control variable.

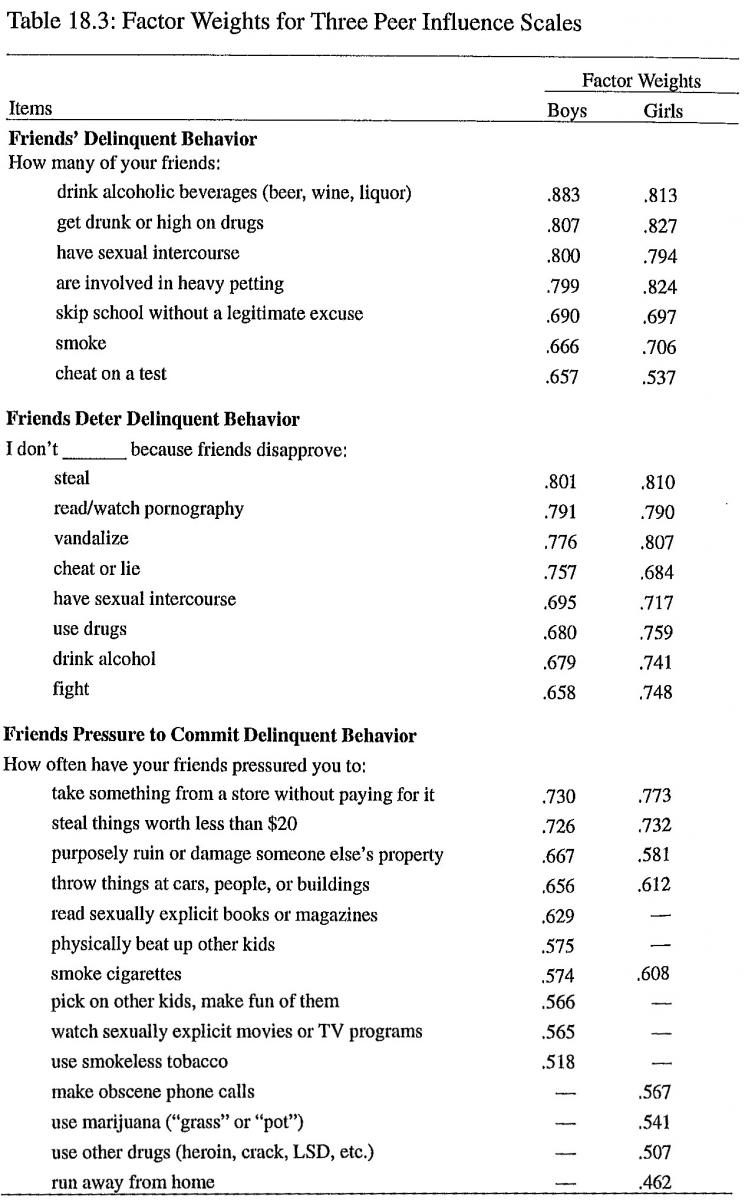

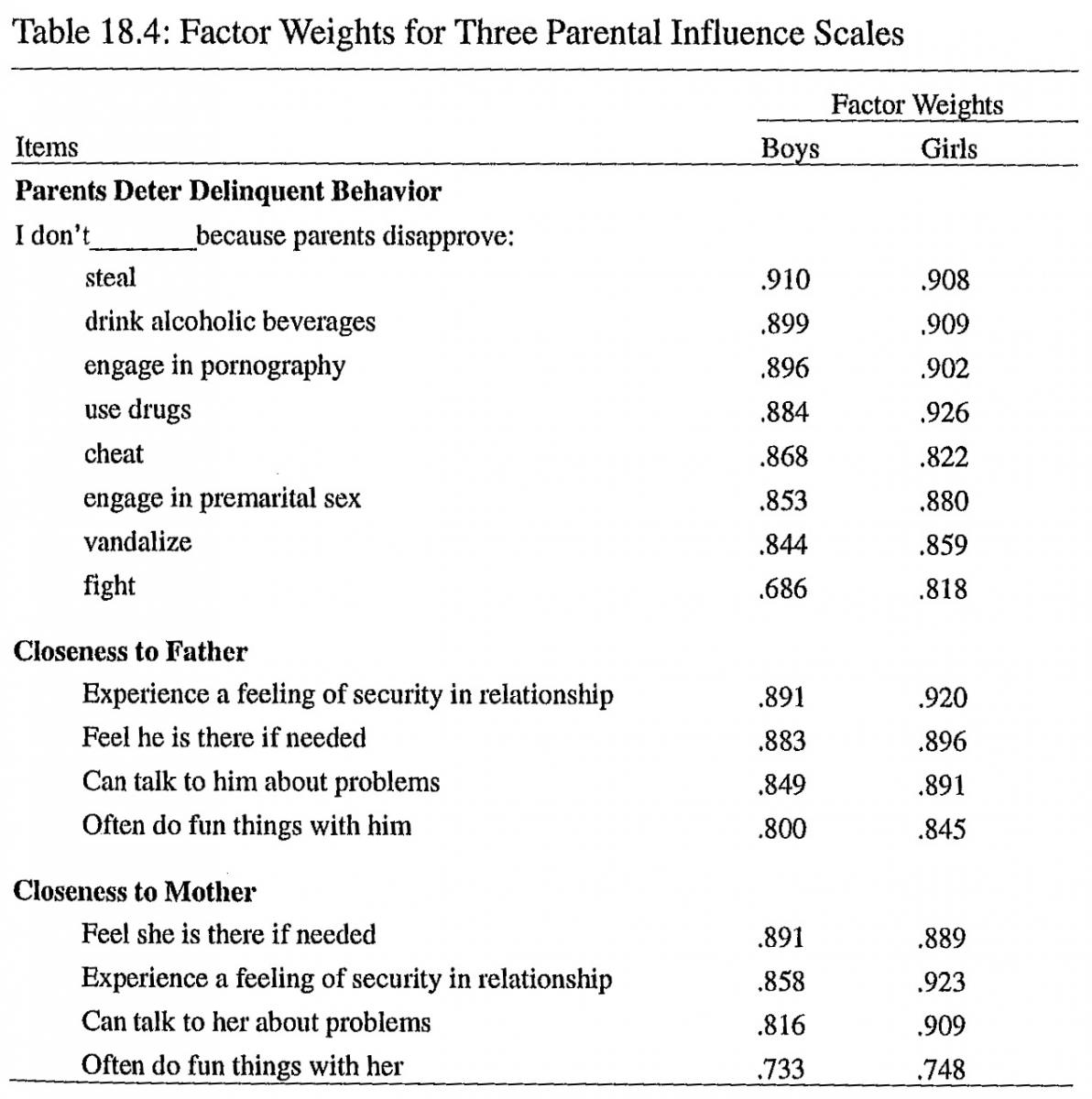

The three sets of delinquency items were submitted to oblimax factor analysis. Standardized individual scores were computed for respondents on each of the scales using the regression method (SPSS 1984). The items and factor weights in the delinquency scales are presented in table 18.1. All of the religion items were submitted to factor analysis simultaneously to ascertain the existence of the several dimensions of religiosity. A few items were removed because they loaded on two or more dimensions. The same procedures were used for the family and peer items. Individual scale scores were computed for each factor via the procedures noted above. The items and factor weights in the religious scales are presented in table 18.2, peer scales in table 18.3, and family scales in table 18.4. The eigenvalues for the various scales ranged from 2.6 to 15.8. In addition, Cronbach alpha coefficients were computed for each scale, and these varied from .76 to .98. The eigenvalues and the alphas both indicate the items combined to produce strong unidimensional scales.

Before testing the general model presented in fig. 18.1, we examined the correlations between the various independent variables to identify any multicollinearity problems. These were determined by regressing the independent variables on each other (Berry and Feldman 1985). Peer disapproval was removed from the model because of collinearity with peer deterrence. Parental disapproval was also dropped from the model because of its high correlation with parental deterrence.

Findings

Characteristics of Sample

Fifty-four percent of the sample were girls and 46 percent boys. This difference was largely accounted for by a somewhat higher response rate from girls (70 percent versus 62 percent). The younger people in the sample were fairly evenly distributed between ninth and twelfth grades. The sample was predominantly white; Asians, Blacks, and Hispanics combined for only 5 percent. The sample was clearly upper-middle class: 29 percent of the teenagers’ fathers had college degrees and 36 percent had advanced degrees. Their mothers were also well educated: 33 percent were college graduates and 8 percent had postgraduate degrees. The fathers worked primarily in white-collar occupations: 56 percent held managerial positions, 14 percent were in clerical occupations, and 5 percent were professionals. Only 13 percent of the fathers held blue-collar occupations.

Frequency of Delinquency

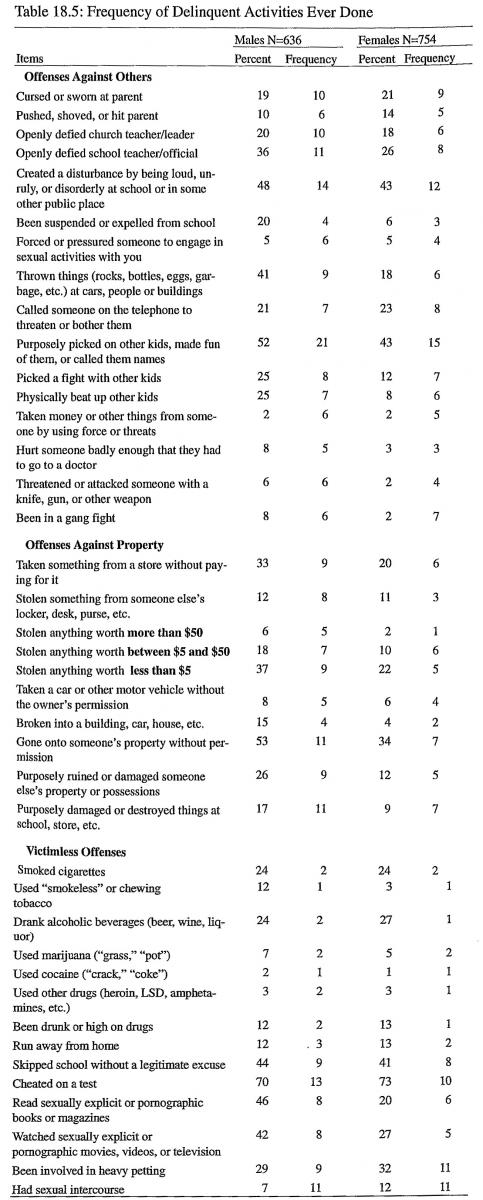

In table 18.5 we present the percentages of the LDS young men and women who had ever engaged in each of the various delinquent activities and the average number of times. Picking on other kids, calling them names, or making fun of them were the most frequent delinquent activities directed against others, followed by creating disturbances at school. Throwing rocks, bottles, eggs, and similar objects at others had also been engaged in by a fairly large proportion of the youth. Not surprisingly, more boys than girls had picked fights, been suspended from school, and thrown objects at others.

Trespassing was the offense against property most often engaged in by the teenagers, followed by petty theft and shoplifting. Significantly more boys than girls had participated in the various property offenses.

Cheating on tests at school was widely practiced: Over 70 percent of both the boys and girls reported that they had done so. Skipping school had also been participated in by most respondents. More young men than young women had read or watched pornographic materials, but, surprisingly, more girls had petted and experienced intercourse. This finding was unexpected since nearly all previous research has reported that boys are more active sexually than girls. Although LDS norms prohibit the use of tobacco, alcohol, and drugs, substantial numbers of the young people had at least tried the forbidden substances. One-fourth reported that they had smoked cigarettes and drunk alcoholic beverages.

The Religious Ecology Hypothesis

The 1977 Albrecht et al. study asked about the frequency often delinquent activities: (1) cigarette smoking, (2) beer drinking, (3) drinking of hard liquor, (4) marijuana smoking, (5) use of LSD or similar drugs, (6) petting on a date, (7) premarital sex, (8) stealing things worth more than two dollars, (9) shoplifting, and (10) starting fights. These were combined into a measure of total delinquency: The first seven comprised victimless delinquency, and the last three comprised victim delinquency. Religious behavior was measured by frequency of attendance at Sunday School, at sacrament meeting (LDS worship service), and at other meetings, and the frequency of personal prayer. Religious attitudes were gauged by belief in the existence of God, Jesus Christ, and the devil, and the acceptance of the Bible as the word of God.

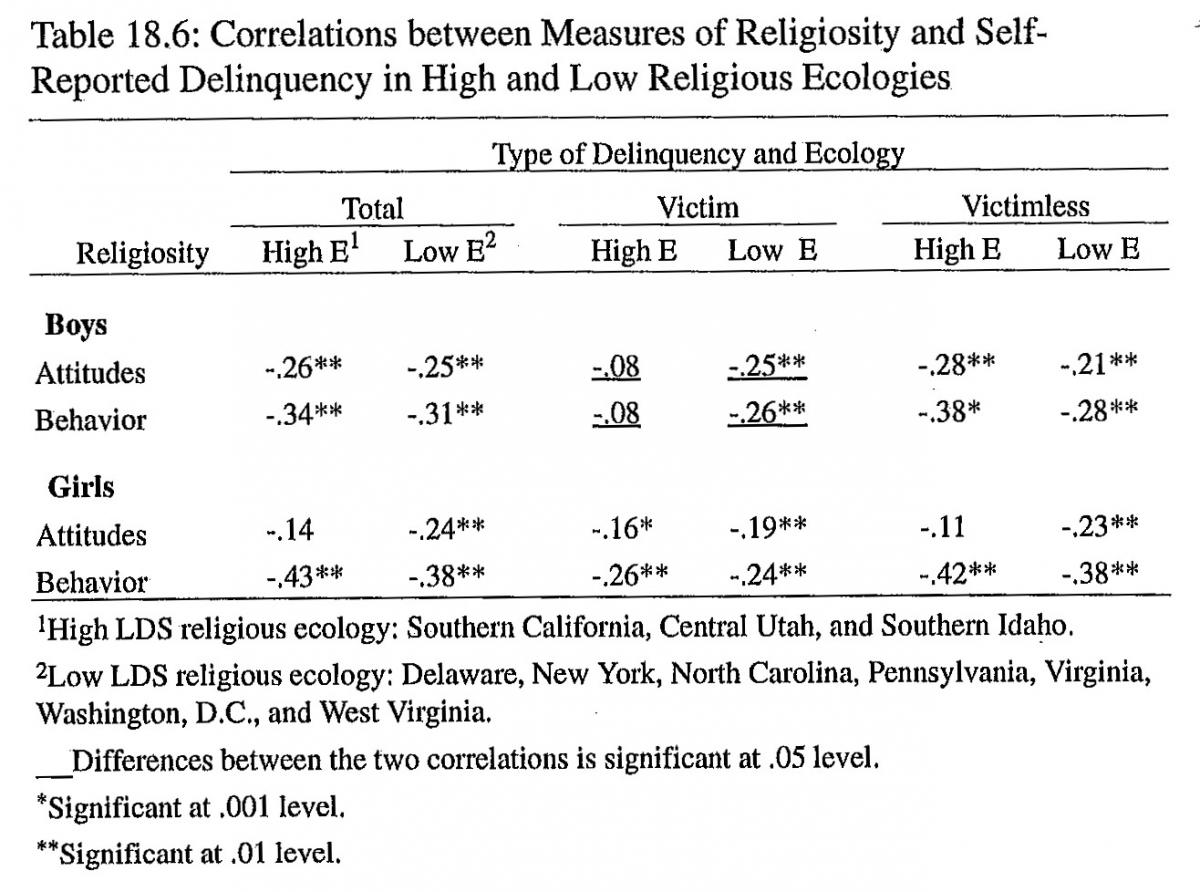

Our 1991 survey asked the same information. There were minor variations in wording and in response categories, but overall the items were very similar, and we created the same delinquency and religion scales. The bivariate correlations between the several measures of religiosity and delinquency for both the high moral climate (1976 study) and the low moral climate (1991 study) are presented in table 18.6. The correlations obtained in the two environments are very similar. The only significant difference was for boys’ victim delinquency, and in this case a relationship between religion and delinquency appeared only for low moral climate. Eight of the twelve correlations in the high climate achieved statistical significance, while all twelve did so in the low-LDS religious environment. The correlations between religion and delinquency among the youth living in a low-LDS ecology were as strong as, if not stronger than, those among the young people from the high religious ecology.

Previous research has suggested that religion has a stronger relationship to victimless activities (such as under-age drinking, drug use, and premarital sex) than it has to other types of delinquent behaviors. Although such was the case for boys in the high moral environment, overall the differences in the correlations between religion and the various types of delinquency were so small as to be negligible.

This lack of support for the religious ecology hypothesis is consistent with a recent study of adult Catholics’ criminal behavior (Welch et al. 1991). It appears that LDS youths have internalized religious values and beliefs and engage in religious practices that are indeed associated with their nonparticipation in delinquent activities. These findings indicate that if we are to understand fully the relationship of religion to delinquency, contrary to Stark’s observation, both psychological and sociological perspectives are essential.

Peer, Family, and Religiosity Model of Delinquency

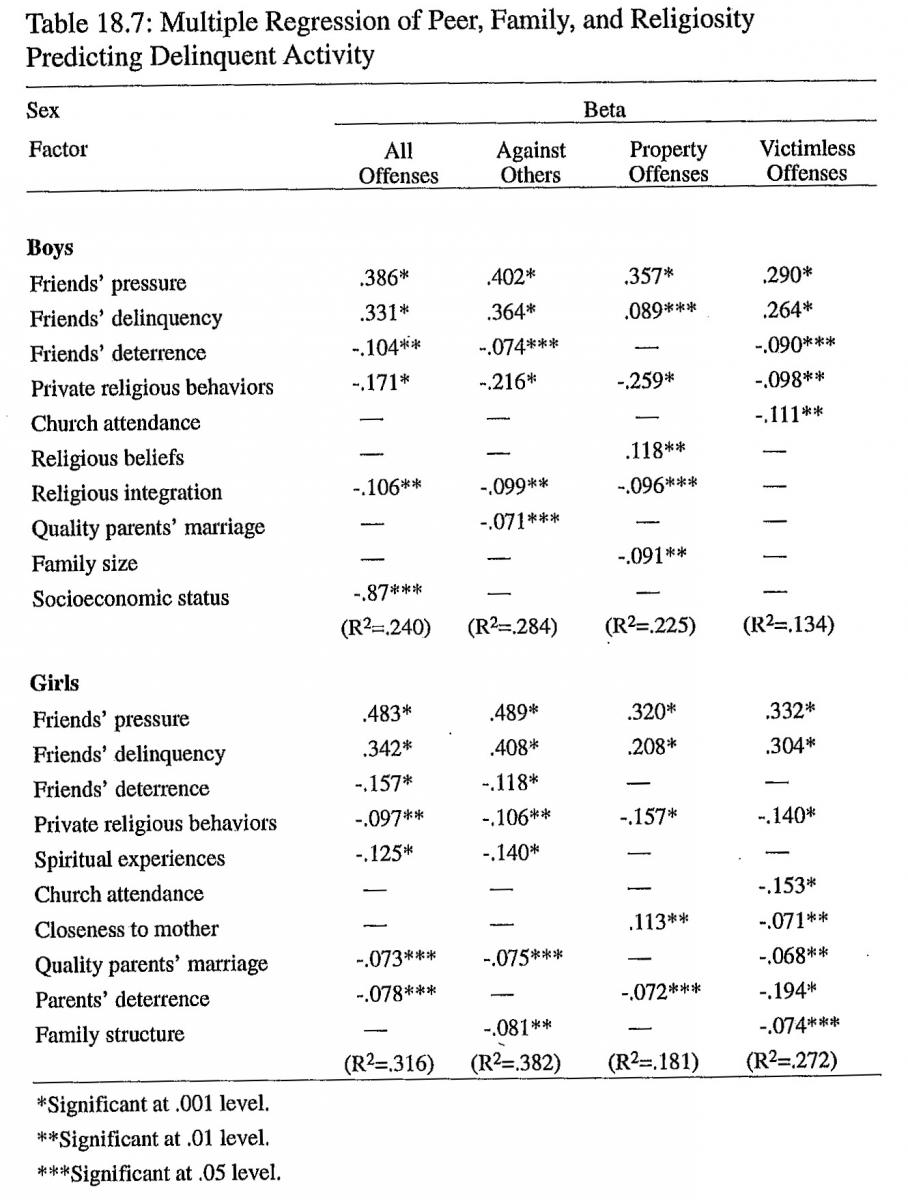

Step-wise multiple regression analysis was used to test the hypothesis that religion, along with peer and family factors, makes a significant contribution to predicting delinquency. Our intent was not to develop a comprehensive model of delinquency, but rather to assess the relative strength of peer, family, and religious factors predicting delinquency. Step-wise multiple regression was utilized because it allows the independent variables to compete to enter the regression equation. The independent variable with the highest partial correlation with delinquency (when the factors already in the equation are controlled) is added to the equation in each step.

The results of the step-wise multiple regression analysis for total delinquency are presented in table 18.7. The beta coefficients and probabilities are those obtained in the final step with all the variables making a significant contribution entered into the regression equation. The first two factors to emerge in predicting boys’ delinquent behavior were (1) pressure their friends put on them to participate in such activities, and (2) their estimates of how often their friends engaged in delinquent acts. The greater the pressure and the more frequent the friends’ delinquent activity, the greater the respondent’s delinquency. Two measures of religiosity, private religious behavior and feelings of integration, also made significant contributions to predicting delinquency. The more frequent the private religious behavior and the stronger the feelings of being accepted in the local congregation, the lower was the level of delinquency. Friends’ deterrence also entered the equation. Finally, socioeconomic status of the family (fathers’ and mothers’ education and income) was added. These six factors together accounted for 24 percent of the variance in delinquency reported by the boys in the sample. Peer or friends’ influences were the strongest factors, since they entered the equation first and had the largest betas, but the two religious factors also made significant contributions to understanding delinquency.

Similar results appeared for the girls. The same two peer factors entered the regression equation first, followed by reports of spiritual experiences. Friends’ deterrence entered the equation next, followed by private religious behavior. Finally the family characteristics, perceived quality of their parents’ marriage, and parents’ deterrence also entered the equation for the girls. The happier the marriage, the lower was the level of delinquency. The level of explained variance was a little higher for the girls (32 percent). Importantly, religious factors made very meaningful contributions to predicting girls’ delinquency.

The same general pattern of peer factors making the strongest contribution, followed by religious factors and family characteristics, appeared in the analysis of the three specific types of delinquency, especially for young men (see table 18.7). Family factors appear to be more important to girls’ delinquent activity than to boys’.

The same general pattern of peer factors making the strongest contribution, followed by religious factors and family characteristics, appeared in the analysis of the three specific types of delinquency, especially for young men (see table 18.7). Family factors appear to be more important to girls’ delinquent activity than to boys’. Among the dimensions of religiosity, private religious behavior and acceptance in religious congregations have the strongest relationship to delinquency. It should be noted that religious beliefs were a significant factor in predicting only property offenses for boys and were not related to any of the measures of delinquency for girls. Also, church attendance was significant in predicting only victimless offenses for both boys and girls. On the other hand, private religious behavior, which is a strong indicator of the importance or salience of religion, was a significant predictor for all types of delinquency among both boys and girls. Finally, integration in the local congregation emerged as a significant factor for the boys and suggests that, for them at least, the social/

The results of these multiple regression analyses clearly demonstrate that religious factors make significant contributions to predicting delinquent activities of LDS youth living in even a low religious ecology. Peer factors are somewhat more important, but the significance of religion should not be ignored.

Conclusion

The LDS youth in this study appear to have internalized a set of religious values and practices that are related to less frequent participation in delinquent activity in both high and low moral communities. The relationship of religion with delinquency for this population is not entirely a cultural or social phenomenon. The link between religion and delinquency was just as robust in the low-LDS religious climate of the eastern states as it was in the powerful religious environments of southern California, Idaho, and Utah.

Contrary to previous research, peer and family factors did not overpower the various dimensions of religiosity in the multivariate analysis. Religion made a significant contribution to predicting delinquency even in competition with peer and family influences.

References

Albrecht, Stan L., Bruce A. Chadwick, and David S. Alcorn. 1977. “Religiosity and Deviance: Application of an Attitude-Behavior Contingent Consistency Model.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 16:263–74.

Bachman, J. 1970. The Impact of Family Background and Intelligence on Tenth-Grade Boys. Vol. 2. Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research.

Bainbridge, William Sims. 1989. “The Religious Ecology of Deviance.” American Sociological Review 54:288–95.

Berry, William D. and Stanley Feldman. 1985. Multiple Regression in Practice. Beverly Hills: Sage.

Bonger, W. A. 1969. Criminality and Economic Conditions. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Burkett, Steven R. and Bruce O. Warren. 1987. “Adolescent Marijuana Use: A Panel Study of Underlying Causal Structures.” Criminology 25:109.

Burkett, Steven R. and Mervin White. 1975. “Hellfire and Delinquency: Another Look.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 13:455–62.

Cochran, John K. and Ronald L. Akers. 1989. “Beyond Hellfire: An Exploration of the Variable Affects of Religiosity on Adolescent Marijuana and Alcohol Use.” Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency 26:198–225.

Coogan, John E. 1954. “Religion: A Preventive of Delinquency.” Federal Probation 18:25–29.

Cornwall, Marie, Stan L. Albrecht, Perry H. Cunningham, and Brian L. Pitcher. 1986. “The Dimensions of Religiosity: A Conceptual Model with an Empirical Test.” Review of Religious Research 27:226–44. Also in this volume.

Davis, Kingsley. 1948. Human Society. New York: Macmillan.

Durkheim, Emile. 1915. The Elementary Forms of the Religious Life. Translated by Joseph Ward Swain. New York: Free Press.

Elifson, Kirk W, David M. Petersen, and C. Kirk Hadaway. 1983. “Religiosity and Delinquency: A Contextual Analysis.” Criminology 21:505–27.

Ellis, Lee. 1985. “Religiosity and Criminality: Evidence and Explanations of Complex Relationships.” Sociological Perspectives 28:501–20.

Empey, L. T. and M. L. Erickson. 1972. The Provo Experiment. Lexington, MA: D. C. Heath.

Hindelang, Michael J., Travis Hirschi, and Joseph G. Weis. 1981. Measuring Delinquency. Beverly Hills: Sage.

Hirschi, Travis and Rodney Stark. 1969. “Hellfire and Delinquency.” Social Problems 17:202–13.

Lunden, W. A. 1964. Statistics on Delinquents and Delinquency. Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas.

Mcintosh, William Alex, Starla D. Fitch, J. Branton Wilson, and Kenneth L. Myberg. 1981. “The Effect of Mainstream Religious Social Controls on Adolescent Drug Use in Rural Areas.” Review of Religious Research 23:54–75.

Rhodes, Albert Lewis and Albert J. Reiss Jr. 1970. “The ‘Religious Factor’ and Delinquent Behavior.” Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency 7:83–98.

Rohrbaugh, John and Richard Jessor. 1975. “Religiosity in Youth: A Personal Control against Deviant Behavior.” Journal of Personality 43:136–55.

Shur, Edwin M. 1969. Our Criminal Society. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

SPSS. 1984. SPSS-X User’s Guide. Chicago: SPSS.

Stark, Rodney. 1984. “Religion and Conformity: Reaffirming a Sociology of Religion.” Sociological Analysis 45:273–81.

Stark, Rodney, Lori Kent, and Daniel P. Doyle. 1980. “Religion and Delinquency: The Ecology of a ‘Lost’ Relationship.” Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency 19:4–24.

Tittle, Charles R. and Michael R. Welch. 1983. “Religiosity and Deviance: Toward a Contingency Theory of Constraining Effects.” Social Forces 62:653–77.

Welch, Michael R., Charles R. Tittle, and Thomas Petee. 1991. “Religion and Deviance among Adult Catholics: A Test of the ‘Moral Communities’ Hypothesis.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 30:159–72.

Yinger, John Milton. 1957. Religion, Society and the Individual: An Introduction to the Sociology of Religion. New York: Macmillan.