World War II

Patricia Rushton, Lynn Clark Callister, Maile K. Wilson, comps., Latter-day Saint Nurses at War: A Story of Caring and Sacrifice (Provo, Utah: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2005) 13–113.

In September 1939, Germany invaded Poland. By 1941 Czechoslovakia, Norway, Denmark, Belgium, Holland, and France had been invaded by Hitler and Great Britain was being attacked. The United States entered World War II on December 8, 1941, on the side of the Allies, after Japan bombed Pearl Harbor on December 7. The United States, Great Britain, and France became the Allied Powers, fighting Germany initially and then the Axis Powers of Germany, Italy, and Japan.

Historical Background

In 1940 the American Red Cross organized hospital units to aid Britain and collect information about the effects of disasters such as epidemics, floods, and crowded living conditions. The Harvard Unit was one of these (Fosburgh, 1995). Units were constructed of tents, and the Red Cross took everything necessary to erect, equip, and supply the hospitals for patient care. Gertrude Madley recalled, “We had twenty-two [tents]; ten for patients, one administration, one laboratory, one kitchen and dining room, one laundry, one storeroom, one recreation, and six for living quarters” (Fosburgh 1995, 501). All of the equipment was transported on British ships. American ships could not land at British ports since America was not yet at war. Sometimes the supplies arrived in an organized fashion, and other times they were destroyed upon arrival by German air attacks, or they arrived too late to be of much use. However, the concept of a mobile tent hospital, fully staffed and supplied, continued throughout the conflicts of the twentieth century and into the twenty-first century.

Crossing the ocean in a convoy brought the risk of being sunk by German submarines. The Harvard Unit had two ships destroyed in transit. Twenty-seven nurses were aboard those two ships. A tanker picked up nine nurses, and six other nurses were taken to Iceland. Four more nurses landed in Iceland after spending twelve days in an open boat. These nurses were so ill from frostbite and exposure that they returned to the United States. Four more nurses landed in Ireland after spending nineteen days in an open boat, and two died from the effects of exposure. The two who survived served another year with the Harvard unit. The four remaining nurses were never heard from after their ship sank.

Madley also described the conditions in Britain after their arrival. There was destruction everywhere. The British people bounced back from every attack, carrying on with their lives amidst the physical destruction and emotional trauma. Madley commented on the blessing of being an American: “How fortunate we are that we are privileged to live in a country like America, and how many of us offer up our thanks in prayer. The things we see in the movies and read about in the newspapers, and hear about over the radio, are actually happening over there. Do we ever try in imagination to live that thing through?” (Fosburgh 1995, 504).

Even though the United States did not enter the war until December 1941, nursing shortages had already become apparent by August of that year (Fosburgh 1995). The shortages became problems for both military and civilian institutions and were an impetus to shorten the education and training period of nurses. Fosburgh notes, “United States nurse anesthetists sought to deal with possible manpower shortages concerning military and civilian service as the threat of war mounted. Proper education and adequate facilities for a full education in nurse anesthesia became a legitimate concern to the profession. Furthermore, American Association of Nurse Anesthetists (AANA) leaders sought to gain military recognition of nurse anesthesia being a clinical specialty within nursing, and allow nurse anesthetists to make the most efficient use of the training” (1995, 387).

World War II was the first time in history that a real attempt was made to salvage the critically wounded from the battlefield (Breakiron 1995). Efforts were made to get medical care to the front for immediate stabilization of the wounded before transfer to a stationary hospital. For the first time, nurses were given commissions as officers and salaries of $70 a month. Under the direction of Major Luther H. Wolff, field hospitals also kept extensive records of the work they performed:

Dr. Wolff wrote often in his WWII diary about how poor the care of the wounded was until nurses arrived. Because of legal restrictions during most of the war, nurses were the only military females allowed to serve outside the continental United States. At their peak, the Army and Navy Nurse Corps had nearly 69,000 recruits. These nurses served at nine stations in 52 areas scattered across 50 nations. Navy nurses served on 12 hospital ships and in more than 300 naval stations. By the time the law was amended in 1944, the first Women’s Army and Navy nurses already had seen action on the Philippine Islands of Bataan and Corrigador. Nurses also had waded ashore with the field and evacuation hospitals on the Anzio, Italy, beachhead four days after the invasion of Normandy, France. (Breakiron 1995, 713)

Breakiron noted that these nurses dealt with many difficulties, including filthy facilities that needed to be cleaned with soap and water, water carried in combat helmets, limited supplies or supplies that never arrived, the cleaning and repair of old equipment, the washing and boiling of surgical instruments, and the long hours. They struggled to provide adequate hygiene for themselves and their patients. However, they were instrumental in some innovations. They worked for the first time with antibiotics, principally penicillin and sulfa. They developed the first recovery room close to the operating room to decrease the amount of time and number of nurses it took to help patients recover in the wards. Nurses became autonomous in making routine, emergency decisions and in giving ether-type anesthesia because physicians were either in short supply or working in the operating room. Nurses who were in dangerous situations learned to use weapons to protect themselves and their patients.

Breakiron notes:

More than 217 Army nurses are buried in U.S. cemeteries overseas. More than 1,600 nurses were decorated for meritorious service and bravery under fire. . . . Twenty-one Army nurses escaped the Philippine Island of Corrigador before it fell to the Japanese, but 11 Navy nurses and 66 Army nurses became prisoners of the Japanese and were interned in the Santo Tomas prison, Manila, Philippines, for 37 months. Thirteen flight nurses crash-landed behind German lines in Albania and were lost for four months before they managed to find their way out. Some nurses were killed instantly when their hospitals sustained direct hits from enemy artillery. Six nurses were killed on the Anzio beach when their hospital was bombed. They lie buried with infantrymen, tank drivers, artillery men, and others in the American cemetery on the Anzio beach.

Some nurses went down with their patients on hospital ships hit by torpedoes. On the night of April 28, 1945, the hospital ship Comfort had all her lights burning and her great red cross showing clearly, according to the rules of the Geneva Convention. The ORs were crowded with wounded. The Comfort carried no guns, so it was helpless when a Japanese kamikaze pilot circled above and plunged into the ship’s superstructure. It tore into the OR and exploded. Six OR nurses were killed, and four were seriously wounded. Those nurses who were still standing continued to work. (1995, 718)

Norman wrote about the seventy-seven nurses who became prisoners of war in the Philippine Islands when the Japanese invaded the islands in 1942 (1999, xii). Norman and Eifried described the fear, deprivation, creativity, and resourcefulness experienced by the group of nurses in order for them to survive their experience and to care for patients. “They endured because they possessed two fundamental virtues. They had each other and they remained faithful to their mission as nurses” (1995, 105).

World War II was the first time American women worked as military flight nurses (Barger 1991). They described the terrible living conditions, the poor food, and the lack of bathroom facilities for women, either on base or at plane stops. They talked about the snakes, lizards, and insects that plagued their lives. They commented on their experiences of trying to stabilize patients and keep them alive while in flight until they could get medical assistance. “Pilots, for example, would land at the nearest base having a medical facility if such a request was made by the flight nurse to save the life of a patient. . . . Concern for their own safety was seldom mentioned by the flight nurses; rather, the safety of their patients was the flight nurses’ primary concern” (Barger 1991, 155). They discussed their own conflict with such issues as whether it was morally correct to drop the atomic bomb on Japan or whether they should save themselves before they saved the patients if there was an emergency landing at sea. Flight nurses commented on the vulnerability they felt while at war. They realized they could die or be wounded. “Writing letters to the deceased flight nurse’s family and arranging for the notification of parents and the disposition of belongings in the event of death reflected problem-focused coping” (Barger 1991, 156).

Flight nurses used techniques common to other military nurses to deal with their own particular situations. Social support was very important, especially among POW nurses. Health and youthful energy were important resources. Diet, rest, and relaxation when possible were important coping strategies. These nurses learned to be creative and flexible in administering patient care as well as in meeting their own personal needs. Flight nurses were noted for their devotion to country, patients, and each other, as well as for their ability to take care of themselves, to be responsible, to meet expectations, and to endure hardships that non-military nurses would probably never experience.

In November 1943, flight nurse training was changed from six to eight weeks and included curriculum in emergency medical treatment, transporting patients at high altitudes, the use of oxygen on board the plane, antibiotic and blood therapy, ditching procedures, and survival. This training acknowledged the ability and autonomy of nurses to manage treatment of patients on board the plane.

A public relations document contained in the news film archives explained that during flights a nurse may have to apply splints, administer medications, stop a sudden hemorrhage, treat shock, administer oxygen, or handle any other emergency. The document claimed that “The flight nurse can do anything an MD can do except operate.” . . . Nurses increased the caliber of care aboard a plane and contributed mightily to the morale of patients who often were airborne for the first time: “The presence of the nurse quieted their fears.” (Stevens, 97)

Some nurses served on active duty in more than one war—sometimes in as many as three different conflicts. Their stories will be presented in the section representing the first conflict in which they served.

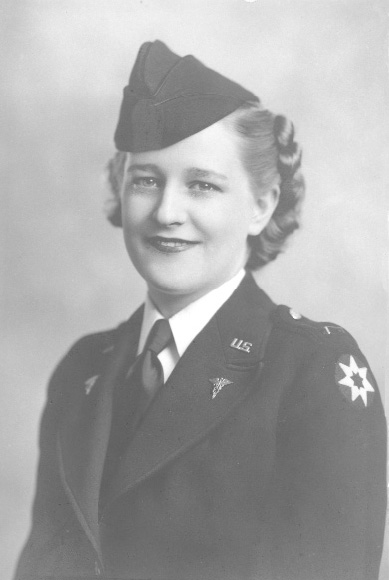

Wylma Jane Callahan Ade

Wylma Jane Callahan Ade

Wylma Jane Callahan Ade

I was born in Davenport, Iowa, on March 10, 1920. During World War II, my mother had a flag in her window with three stars on it for the three children [two sons and one daughter] she had in the army. The Gold Star mothers had a gold star for their children that were lost in the service. They started taking some women in the military after I left for the service, but up until that time the only women in the military were nurses.

In 1941 I was at a Children’s Memorial Hospital in Chicago on a pediatric affiliation when the bomb was dropped on Pearl Harbor. I was a senior. My main thought was that the war would be over before I could have the chance to go into the army. I think how different that is from the people now. But there is a little renewed interest in the military and public service since September 2001.

When I was in school, the pay for registered nurses was $70 a month, but when I graduated it was increased to $90 a month because by September of 1942 the older nurses were already leaving, and they were having trouble staffing the hospital. When I went in the army as second lieutenant, the pay was $150 a month. That was a lot of money then.

I graduated in 1942 and at that time the war was in full speed, so we only had to take state boards for one day because they wanted to hurry getting us registered. I had already signed up to go in the 31st General Hospital in Denver, Colorado. Because I was affiliated with that hospital, I knew I would eventually be going overseas. However, my first duty was at Fort Leonard Wood in Missouri. It was an engineering camp not too far from St. Louis, Missouri. I was at Fort Leonard Wood for several months. There we did calisthenics, marched, and all the military things, including taking caring of patients in the hospital. The military was getting us ready to go overseas. We did an obstacle course where we had to crawl under barbed wire while machine guns were firing over our heads. I guess they were a safe distance over our head. I was young, but many of the nurses working in the hospital were quite a bit older than I was, and they had to do everything that we had to do. It was hard for the older women.

The medications were very different from what they are today. APCs were the drug of choice. Everybody got it no matter what was wrong. The APCs were aspirin, phenacetin, and caffeine, kind of like Empirin now. We had aspirin and soda: you would give a 5-grain aspirin and 5-grain soda tablets. Sulfa was just being developed in the late 1930s. Germany was where Prontosil and Neoprontisol were really developed, and they were miracle drugs at the time. They were a sulfa-type drug. They were the first things we had to fight infections. Morphine was the drug for pain besides aspirin. We boiled water in little teaspoons and dissolved the morphine tablets and drew it up in our syringes. We probably used codeine for milder pain.

In 1942 penicillin was being developed, but it was a long time before they had the long-acting type. We had to administer it every two or three hours and it was a big job to keep giving penicillin around the clock. There was a lot of gonorrhea with the soldiers, and penicillin proved to be effective in treating it.

After we left Fort Leonard Wood, we went to Camp Carson in Colorado, and that was when the 31st General Hospital was organized. Of course at this time the war was escalating, and we were looking forward to getting on with our duty. When we left Camp Carson, we were up all night at Camp Stoneman in California, where we were issued wool clothes. I am sure that the army knew we were going to the South Pacific, but they issued us all the army wool clothing to take to the South Pacific, where it just mildewed and most was just thrown away because it was useless. My friends who were nurses in France were freezing to death. I have heard many of them talk about how they were so cold and they didn’t have anything warm to wear.

After being up all night, we got aboard our ship, the Klipfontein, which was a Dutch ship still on its maiden voyage. It was a luxurious ship. We went down to San Diego and picked up about 2,500 marines. The crew on the ship was trained to take care of the people who would ordinarily be traveling on a luxury ship. The dining room had all silver service. It was quite elegant. In the morning they would put out hard rolls and meat and cheese so that we could fix a sandwich. We only had two meals a day, so at lunch we would have tea or hot chocolate and maybe a soup and the sandwiches we had made earlier. In the evening it really was almost a formal dining room. We heard later that the ship never made it home. It was sunk before ever reaching Holland again.

Our destination was Noumea, New Caledonia. Our first area was a beautiful French town named Bougeanvillea; the whole island was covered with red and purple flowers. There was a big navy base there. We were stationed at a little hospital about ninety miles north of Noumea. We were only there for a short time for temporary duty.

We were then sent to the New Hebrides on the island of Espiritu Santo. That was where we were for the next couple of years. We had a big general hospital: one-thousand patients the first day. All the islands in the Pacific had many fierce battles going on, like Guadalcanal and Saipan. Those casualties were sent back to our hospital. We had a large group, a large hospital, and we had all the services. There were probably 100 to 130 nurses in my group; we had physical therapists, x-ray technicians, and five Red Cross workers. There were only female nurses in my unit, and our unit was also all white. We had to censor the mail of the enlisted personnel. I don’t think the officers’ mail was censored. Much of our mail was the one-page V-Mail; it was not so bulky. The five Red Cross workers who were assigned to our unit were friends and all lived together; they would take care of the patients’ other needs, such as writing letters to their families, and other things. It was a one-thousand bed hospital. Some of our doctors were young, and others were experienced surgeons and orthopedic doctors. Our hospital was filled the first day it opened.

We had all kinds of bad injuries. I remember a few of them specifically and how hard we would work to get them stabilized so that they could go home. Later we would find out that they died on the way home. We felt bad about that because we gave them everything that we could to keep them going. We worked long hours. It was like all nursing: you worked until the work was done. We all had to take turns doing night duty. We still didn’t have many drugs. We still gave the penicillin around the clock. We had the sulfa drugs too. We were able to take care of some infections that we would not have been able to earlier on.

When I was in my school of nursing, there were no aides or corpsmen to help us. The student nurses did everything; we cleaned the bedpans and took the flowers out at night to water them. Nursing was completely different then from what it is now. In the army we did have corpsmen and we had a very good relationship with them. They were good, dedicated men working to help us. Some of the patients were in critical condition. We did work hard on some of them just to get them stabilized because we were a long way from home. Down in the South Pacific it was probably a two- to three-week trip to get back to the States.

We had a lot of orthopedics and gunshot wounds. Some were self-inflicted because they wanted to go home. They probably had good reason to want to go home. The islands were not that pleasant. It was hot and sweaty, and the food was not very good. Wherever they were, it was grim. It was so different invading those islands than the hand-to-hand combat that you usually think about in war. They had to go island by island and take each one separately.

One of my most memorable patients was a fellow named Updike. He was seriously injured. He was there a long time before we got him stabilized and ready to go home. As far as I know he made it home. It was hard to get information back because there were so many ships taking people back and forth that it was just a fluke if you heard from anybody. In Espiritu Santo we worked just like we would in the States and did everything that we could for the patients. I don’t remember ever having a shortage of medications or dressings. It seems like we had everything that we needed.

The military would fly in the wounded, but most of them came by ship. There was a big harbor and a navy base. Whenever we wanted a good meal, we would go out with someone in the navy because they always had better food. I didn’t drink milk, I didn’t eat eggs, and I didn’t like beer, so it wasn’t a hardship to me as far as food was concerned in the army. We had raisin bread once a week, and one of my friends would pick the raisins out of mine because I don’t like raisins.

In Espiritu Santo there were no Anopheles mosquitoes, so we didn’t have to take Atabrine as a malaria preventative. Many of the other nurses on the other islands had to take Atabrine, and it turned their skin yellow. We did have a mosquito net, and there were mosquitoes, just not Anopheles mosquitoes.

We had a limited knowledge of how the war was progressing. We were in radio contact, so we knew what was generally going on in the different battles. After being on Espiritu Santo in 1943 and 1944, we were transferred to Hollandia, New Guinea, for several months. Hollandia was where General MacArthur had his big home on a high peak so he could look out on the ocean. When we were in Hollandia, New Guinea, there were some navy and marine officers there who were sure the war was going to be over soon. I think they knew something about the atomic bomb. I think they knew there was something special in the works because they wanted to bet us that the war was going to be over soon. We were just as sure that it wasn’t going to be.

After we were in Hollandia about three months, we were sent to Luzon, Philippines. There were still some of the Japanese army fighting in the hills around us while we were there, and it was considered an active war zone. That was where the Japanese came in when they invaded the Philippines and continued on to Manila, Bataan, and Corregidor. The Japanese occupation lasted until the early part of 1945.

The war just seemed to get progressively worse as we moved on. The first time that we heard about V-E Day (May 7, 1945) was around Mother’s Day. We were happy that the war was over in Europe. I was in the Philippines on V-J Day (September 2, 1945). Every morning songs that were popular in the States, like “Sentimental Journey,” were played over the loudspeaker. Then we heard, “Now hear this, now hear this!” and we waited to hear what was going to be announced. I remember when they announced the war was over in Japan. That was a very happy day, but we didn’t think that affected us much because we were still busy.

I heard over the loudspeaker that the war was over, and then we got a little camp newspaper that was just a one- or two-page sheet. I suppose more information came to us after the first bomb fell. We had been waiting all summer for something to happen. Every day when they alerted us over the loud speaker, we kept thinking that something was going to happen. We were probably getting ready to go home. We had been overseas since 1943, but every day was a busy day just like it was for everybody else. You have certain things you have to do everyday, so you keep going.

I still have a camp newspaper that was published when the war was finally over. It is kind of hard to remember what I heard then about the bomb being dropped and what I have heard since. I picture the big atomic bomb with the big umbrella. I don’t remember when we first knew that there was an atomic bomb or of the devastation in Japan. It is only now, sixty years later, that I fully comprehend all the atrocities of that war. As I read about the experiences of the people who were prisoners in the Philippines and how the Japanese people treated them, I really feel we got off pretty easy. I feel sorry for the devastation of the atomic bomb, but I don’t think that the people in the United States really comprehended what they were doing to us, even though they saw the things happening at Pearl Harbor. That was terrible, but it was only the beginning. Wherever there were prisoners of the Japanese for the next three years, it was incomprehensible how they were treated.

We were on a hospital ship for a month coming home. Something happened to the ship’s rudder, and we were out in the middle of the Pacific Ocean going around in circles until they got it fixed. It was pretty rough coming home. We were mustered out at Fort Sheridan. We got a lot of money because we hadn’t been paid for a long time. We left in December, and it was cold. We must have looked like poor people from Europe. We had carried our wool clothes all through the South Pacific, and we didn’t have any warm clothes by the time we got home. We had a lot of money in our pockets, but we probably looked pretty sad. I came home on Thanksgiving, and the war was over in August. I was on leave until February, so we were still considered in the army until the middle of February.

My dad was a rural mail carrier, and one of the regrets that I have in my life was that when I came home from the army he wanted me to wear my uniform and go on the mail route with him, and I didn’t do it. I was just glad to get out of my uniform. I did go on the mail route with him. He was extremely proud of me. For three years everybody on his mail route had to hear about me. I am sure that everyone on the mail route knew all about his three children who were in the service. It would have given him so much pleasure if I would have worn my uniform so he could show me off, but I didn’t do it, and it is too late now.

When I was discharged from the army, they gave me bars to symbolize the medals for which I was qualified. One is from being in the American theater, USAFFE, and the Bronze Star. I will have a Bronze Star on the Philippines victory medal because they were still shooting there. I never picked my medals up because I never thought the medals that go with them were important, but now I want to leave a legacy for my children and grandchildren. I recently wrote to my congressman to get them. Hopefully they will soon be on their way.

Then I got married in 1947 and joined The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in 1952. I was Catholic at the time of the war, and I had the opportunity to go to church. Espiritu Santo was a French island with a French coffee plantation owner, just like in the movie South Pacific. There was a little Catholic church that we would go to. I remember hearing that there were Mormon church services on Sunday afternoons at about 3 o’clock. I know there was a nurse and some corpsmen who were Mormon. I know that there were Mormons in my group, and I know that they did meet.

When I was in the Philippines, I didn’t drink beer or smoke. I thought I was doing all the work while everyone was outside smoking. I decided to join them. It wasn’t easy to start smoking. You choke and cough, and you really have to be determined to abuse yourself like that. My main thought was that I was working the floor while everyone was getting a break. I was never a heavy smoker, but one year at Christmas time I added up all the money I was spending on cigarettes, and it was about a dollar a week, and I thought with that I could buy a package of cookies and the whole family could enjoy a treat. In March 1952 we heard about the Church. If the missionaries would have come around and told me I could not smoke or drink coffee (I had been drinking coffee my whole life), I would never have listened to them. But by then I wasn’t smoking. I have always been glad I did quit smoking. It was foolish to ever get started in the first place.

I went to church more while I was in the army than I did growing up. In Espiritu Santo we went to church more than we did other places. When you are working you don’t necessarily get every Sunday off to go to church, and I don’t remember going to church in the Philippines. I think that I was always fundamentally a good person, but I don’t think that I was real religious at all during that time. We never had a lot of religion in our home while I was growing up. After my husband and I got married and joined the Church, it became a big part of our lives. There was not even a Mormon Church in Davenport, Iowa, until after we moved away. I don’t know what I would do with my time and money if I wasn’t able to serve the Lord.

We were living in Davenport, Iowa, when we joined The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. We started to go to church in March and were baptized in May 1952. I had a strong testimony from the very beginning.

I would like to tell my children and grandchildren that I am happy I had a chance to serve. I never felt like my experiences were more than any ordinary job that anyone else does. I know that when we are helping we are happy. I feel fortunate to do as much as I can do at age eighty-two. I don’t know that I have had many trials, and I have been incredibly blessed. I think that I was blessed to recognize the truthfulness of the gospel. I know it has been a blessing to my children and grandchildren.

Laura Ellen Alley

I graduated in June 1944 from LDS Hospital School of Nursing. I enlisted with a friend of mine on March 1, 1945, and was sent to camp at Fort Lewis, Washington. We went up to Fort Lewis, which was absolutely wonderful. We were treated just like the troops. We went out on bivouac, and we were there for a month. We had to do drills, and we had to learn some army law and things like that.

After that thirty days we were sent to Macaw General Hospital in Walla Walla, Washington, where I was assigned to the orthopedic division. At that time we were working twelve-hour shifts for six or sometimes seven days a week. We were short of help. When I was in orthopedics, these kids would come from the front in casts that had never been changed, or with wounds that looked abscessed. They weren’t healed when they got to me, but they were in fairly good shape. As soon as they got there, we would cut off the casts and start looking at the wounds, and they were full of maggots. I just nearly died. I will never forget that experience when we cut away the cast. One fellow who had on an airplane splint was the worst. The wounds that I saw with the maggots were clean and not infected. The maggots just happened because of the conditions they were in: the doctors didn’t put them there. We cleaned the maggots out of the wound because they were far enough along so that they were doing okay. When I came home and was working at the hospital in Salt Lake, the patients had severe osteomyelitis. The doctors were beginning to use a lot of antibiotics, but they weren’t as effective in these kind of cases as maggots.

I worked in the orthopedics division for about a month, and then I was transferred to the paraplegics and quadriplegic wards, where I stayed until I was transferred again. I had a wonderful experience with those boys. Most of them were about nineteen or twenty-year-old boys. We cared for them and tried to get them up into chairs, swimming, and out into the social life.

It was the last of September 1945. I volunteered to go overseas once a month. Finally, as the war tapered down over there, we were sent to Birmingham General Hospital, Van Nuys, California. Macaw was closed at that time because of the war closing up a little. We stayed with those boys, and they made a lot of progress down there. It was really a pretty good experience. By that time we were working eight-hour shifts, which was standard in nursing, but we still sometimes worked six or seven days a week.

In March 1946 they said that they were going to close Birmingham, so I elected to come home.

All of them [the patients] were so young (I was twenty-two). Most of them were my age or younger. We had two or three who were older—in their late twenties. This one fellow was paralyzed from the waist down, but he had a lot of spasms, and he used to bend over into fetal position and couldn’t help it. He would cry. So all of us spent a long time trying to help him through this. We had an older man from California who was in his late twenties or early thirties, and he wouldn’t let anybody but me shave him because I did such a good job.

We had the old Stryker frames; they were just coming out at the time. You had to be sure that the patients were tied in, and we had to turn them every two hours. We had several patients’ legs fall out of the frame when we turned them. Before we used Strykers, we used manpower. We just turned them. I remember when I came home from the service, my sister-in-law Virginia said to me, “My gosh, you have the most wide, powerful upper body that I ever did see.” It was from lifting those kids. We had to turn those Stryker frames frequently. We had a young man who came from the Pacific zone and had malaria quite bad. He was on a Stryker frame (he was a paraplegic). When he would begin his chills, a couple of us would have to lie across his body to keep him on top of the frame because he would shake so violently.

Antibiotics were new in nursing—at that time we had just started giving penicillin. We had some sulfa that we used, but the penicillin was the thing. We used to fill a syringe and then just change the needles and give them each one cc. Streptomycin, I think, came out at that time too. The Wangensteen suction was improved a little bit at that time. It was the two-bottle stomach suction. The Stryker frames were made wider after the war ended. The care of paraplegics and quadriplegics also improved because caregivers realized that patients needed to be up and more active.

We used to load a government van up with the kids and take them out to the diners. All the restaurants and show places down there catered to these kids and built ramps for their wheelchairs and put them up at the tables. They were very helpful.

There was one parapalegic whose father was very wealthy. This independent young man came down to Birmingham while we were there to demonstrate to the boys what they could do. He had his own car, and he would show them how he could get in and out of his car and show them different techniques he developed to help himself. He got sick with kidney problems while he was there. We kept him for several days until he could move on. He did a lot to show the boys how independent they could become and how to get around much better.

I wasn’t aware of any nurses or boys who were LDS. They did have a church and a Protestant chaplain, as I remember. We just all went to the church.

I think my life was different because I served those thirteen months. I got a lot of good nursing experience. I developed a lot more patience and understanding of some of these people who had such terrible wounds and accidents. My skills developed considerably in taking care of post-op patients. I don’t think the nurses who didn’t serve in the war ever realized the importance of turning patients and making them get up, and making them breathe and all of that. That was one thing we really starting doing with the patients and getting them ambulatory a little bit faster.

I’m glad I stayed in nursing. I haven’t been disappointed with any of that.

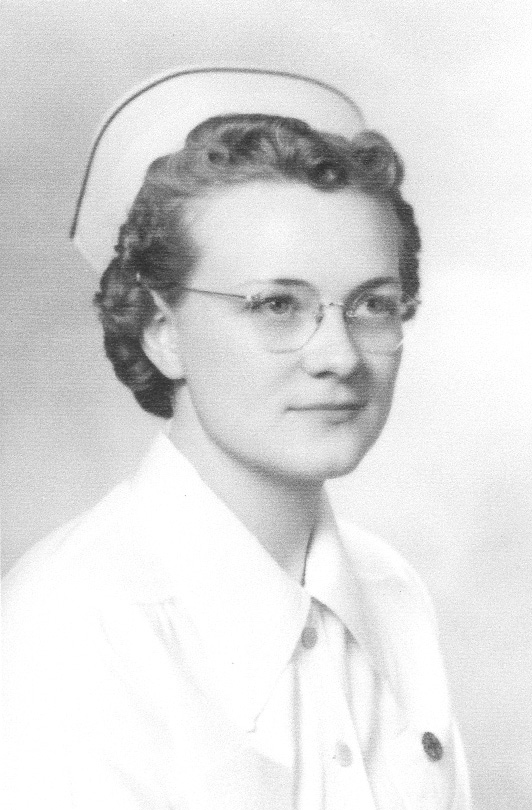

Alice Lofgren Andrus

On December 7, 1941, I vividly remember that I was a junior student nurse on duty in an outpatient clinic at the Los Angeles County General Hospital. Sunday was seldom busy, so while we were between patients, several of us were listening to a small radio when we were startled to hear about the tragic attack on Pearl Harbor by the Japanese. As World War II was declared, we knew that all of our lives would be changed.

Alice Lofgren Andrus

Alice Lofgren Andrus

I received my navy orders to report to the Oak Knoll Naval Hospital at Oakland, California, by May 10, 1944. I reported to the office at Oak Knoll Naval Hospital. I was now officially a navy ensign.

As I remember back over fifty years, within a day or two I was in uniform, taking care of patients in the burn ward while I also learned the navy’s way of doing things. Every week or so we were alerted that a convoy of ships from the fighting in the Pacific would soon arrive, bringing new patients.

Many of our patients were undergoing a series of reconstructive plastic surgeries to repair damage done earlier. Ambulatory patients helped us take care of bed patients and admit new patients. Their friendly joking and assistance soon made new patients feel welcome. Some wanted to talk about their experiences, like the barely eighteen-year-old sailor whose oil tanker had gone down with burning oil engulfing everyone trying to escape. The young sailor was severely disfigured by burns on his face, head, arms, and body. Talking about it seemed to be his way of trying to accept the fact that he really was scarred and that nothing would ever again be normal for him. Another patient had only moderate burns, but he had been told that he would never see again. While he was despondent and wanted to be left alone, occasionally other patients quietly made brief visits to his bedside, gradually making him feel one of the group. He was still depressed, but he did not feel alone, as the other patients gave him moral support and understanding.

Another patient had been confined to bed for some weeks. As he began to feel better, he wanted to get up and walk around, but his orders as a bed patient remained. Finally one day, with nearby patients as lookouts, he sneaked into the bathroom and was almost back to his bed when he was seen by a corpsman. When the doctor was told of this adventure, he laughed. When patients are determined enough to sneak out of bed, he explained, they are well on their way to recovery. This improved the morale of the whole ward.

Some of our patients, between operations, were encouraged to get passes and take the bus to Oakland to get used to being among civilians again. Some who had gone once refused to go again. They said that some children and many adults would stare at their scars, crutches, or bandages and whisper, point, and laugh at them. Since they were in uniform, it was obvious that their wounds were a result of the war, but many people reacted in a cruel, unthinking way, ridiculing anyone who looked different in any way.

Once when I was working a late shift, all but one of our patients who had been out on passes were back in bed. Suddenly, the door to our ward was jerked open, and in walked our marine patient. He was tall, strong, good-looking, and a little unsteady on his feet. He was angry and mumbling something I couldn’t understand. As he stood in the hall, he suddenly punched a hole in the plasterboard wall. This was entirely out of character, as he was a friendly, good-natured person whom I had never seen angry before. I quickly called the corpsmen, who, with the help of another patient, soon had our marine sleeping peacefully in bed.

In the morning he was embarrassed to see the hole he had made in the wall and explained that he had been out with a buddy who had noticeable scars. They were enjoying a fine evening until several civilians began making crude, ridiculing jokes about them. Since getting into a fight could have caused serious medical problems, especially for his buddy, they controlled their anger and walked away quietly. However, the anger and frustration remained. All of us in the ward understood, and the wall was soon mended without comment.

Many of our patients preferred to remain in the ward or on the base among others in uniform, where they were accepted without question. It was a sanctuary where they felt safe. Planning on moving back into civilian life was traumatic for many, especially for those with extensive scars that could not be corrected, even with skilled plastic surgery. Some of the luckiest patients had families who would occasionally visit them and plan for their homecoming with joy and acceptance, but others just had to hope that their families and friends would not desert them.

I will never forget how the patients on 74 A Burn Ward developed close friendships and acted with compassion and good cheer, even when they felt sad and worried inside. It was a happy ward where I had many friends, and I was content to work. Once I was transferred to a medical ward, but within a few weeks I managed to get transferred back to my favorite ward, 74 A.

During my months at Oak Knoll, I remember that we did have a few drill sessions and even marched in one dress parade on the base. We also had to pass a swimming test, which was easy for me because I enjoyed swimming. Navy life included lighthearted times too. Being stationed fairly close to San Francisco was an experience most of us enjoyed. When we were off duty, a few of us nurses would put on our dress uniforms and take the local bus to Oakland and then the “A” train to San Francisco. There we would happily spend all day sightseeing, eating at favorite restaurants, shopping, or maybe seeing a movie before starting the long journey back to the base.

We heard that the military needed nurses to sign up for sea duty on a navy hospital ship that would soon be commissioned. As much as I liked working on the Burns and Plastic Surgery Ward, the opportunity to go to sea on a hospital ship seemed irresistible. Very soon my official application was on file in the office, and I was notified that I was accepted and I would receive transfer orders within a few weeks. Many friends, both patients and coworkers, were disappointed that I would be leaving.

One interview that touched me the most was when our top surgeon called me into his office and tried to talk me into changing my mind. He knew that I liked working on the ward, and he sincerely believed that I would be unwise to go into a situation where I might find problems I didn’t expect. He had been in the navy for many years and said that women in areas closer to the war were assumed to have loose morals, and he was convinced that I might get a bad reputation, whether or not it was deserved. He assured me that if I had been his daughter, that is the advice he would give me. But I had the self-confidence of youth that I would get along all right. The promise of new adventures was too great to resist, so the surgeon reluctantly agreed to my transfer.

At the airport I was disappointed when someone with a higher priority got the last seat on the last plane departing that day for the East Coast. Since I was suffering from chills and fever, the kind people at the airport arranged for me to stay all night in the stewardesses’ overnight room at the airport. How grateful I was to crawl into bed and have a good night’s sleep.

The next morning I felt much better and was soon on a plane flying east. Not long after we were airborne, the stewardess began handing out small gifts to all of the passengers. We were delighted to hear that the war in Europe had just ended, and the airline company provided key chains for all with a small medallion inscribed with “V-E Day, May 8, 1945” and a wish that we would always remember our flight that historic day.

When I finally reached Norfolk, Virginia, and reported aboard my ship, the USS Consolation, I was assigned to share a small inside stateroom with another ensign—a tall, blonde, cheerful young nurse. We became good friends, and I felt very lucky to be aboard. Our small stateroom did not have a porthole, so we found a stick-on picture of a porthole and soon felt right at home.

On May 22, 1945, the entire new crew assigned to serve on the USS Consolation was aboard for the official commissioning ceremony. We also went on a shakedown cruise in Chesapeake Bay and returned to the shipyard in Norfolk. Since modifications on the ship would require more than a month, we were encouraged to request official leave, so I did.

My sister Ruth was on the faculty of the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, so we had time for a pleasant visit. One event I recall was a delicious steak dinner she had prepared for us in her apartment. When I casually mentioned that I liked the meal and that we had steak dinner fairly often in officers’ mess, Ruth seemed rather shocked and explained to me that steak was a rare treat for civilians. She had been saving up her ration coupons for quite a while so she could prepare something really special. It made me realize how fortunate I was to be a navy officer. I hadn’t realized how much civilian life had changed, with so many regulations, shortages, and frustrations of all kinds.

When I returned to the ship, it wasn’t long until we made final preparations for going to sea, at last. After we got under way leaving Norfolk on July 14, 1945, we soon settled into a daily routine of assignments. The ship’s crew was busy with the mechanics of running the ship. Since we were equipped to serve as a floating hospital, but had no patients aboard, it must have been challenging to keep all the hospital personnel busy, including doctors, thirty nurses, hospital corpsmen, and two women Red Cross aides who were quartered with the nurses.

Because I was the nurse with the lowest seniority, I didn’t question my assignment to be in charge of the linen room, supervising several corpsmen.

There was an old-fashioned treadle sewing machine in the linen room. When I said I knew how to use it, the medical officer in charge of the x-ray department asked me to make a dust cover for the irregular boxlike x-ray machine. I was pleased to have a useful project to work on. Making a rough sketch of the machine, I took measurements for a guide. One of the corpsmen got some muslin from the ship supplies, and we started cutting. Sewing pieces together was simple, but when we first tried the cover on the machine, we found where angles had to be modified. Before long, the x-ray machine had its cover.

A few days after we left Pearl Harbor, we sailed west in the Pacific. On August 17, 1945, we crossed the international date line, and since we had no patients aboard, the hospital staff happily joined in a Davy Jones’s Locker celebration. A carefree evening of games, special events, and movies temporarily made the war seem far away.

When we reached port, mail call was an eagerly awaited event. Even getting an advertisement was better than getting nothing. Some people were very popular, receiving a handful of letters, some even perfumed, according to the sailor handing out the mail. It was sad to see that some never seemed to get any mail, and they would usually avoid mail call. One learns to travel light in the navy, so I only saved a few of the letters I received.

When we were first ordered to the Pacific, we were supposed to be a stationary hospital convenient to the fighting wounded, but our orders changed as we proceeded. On August 28, 1945, we anchored in Buckner Bay, Okinawa. For the next few days, the nurses were allowed ashore, a few at a time. We visited the informal headquarters and were driven by jeep on a brief sightseeing tour, but we were required to have an armed guard along at all times. We were told that even though the island was considered secure, it was impossible to predict when a Japanese sniper might appear, since they were experts at hiding out for long periods of time. As I recall, some of the nurses decided not to go ashore, but I will always remember that jeep ride along the narrow road on what became a historic island.

The war finally ended on September 2, 1945. On V-J Day, we were still in Buckner Bay, but with new orders. On September 9 we sailed toward Wakayama, Japan, where we helped in the evacuation of newly released prisoners of war. We departed on September 18, arriving at Hagushi, Okinawa, where many of the patients were taken ashore on September 22 and 23 to be flown to their home countries as quickly as transportation could be arranged.

We remained in the western Pacific for several more weeks. On October 26, 1945, we were in Nagoya, Japan, where we were given new orders. Our “magic carpet” orders had us soon making many trips, transporting military dependents from Honolulu to San Francisco. The new orders also included a transfer of most of the hospital staff to shore duty. Only seven of us remained from the original thirty nurses. A few doctors and corpsmen also remained on board to help care for patients and passengers.

On February 14, 1946, we finally left San Francisco, heading south. Two days later we went through the Panama Canal again, going from the Pacific back to the Atlantic Ocean. On March 3 we arrived back in Norfolk, Virginia, where we remained for several weeks. In the following months, the USS Consolation was assigned to stay with a navy fleet in the Caribbean.

Finally, we returned to New York City on May 24, 1946. Although I had requested permission to stay on board, I was told that all of the nurses were to be transferred to land bases. Without sea duty, I decided that the navy no longer needed me. I had more than enough points to be released from active duty, so I was officially released from active duty in the navy on August 7, 1946. (Written November 1993.)

Alice wrote about a memorable patient:

One day we had a patient transferred by stretcher from another ship to our hospital following a storm. He was in a coma and was taken directly to surgery. Apparently, he had been working on the deck of his ship when an oil drum broke loose and smashed him in the head.

After some hours in surgery, he was placed in one of our private rooms and I was assigned to monitor his condition and notify the doctor when he regained consciousness. Since the intercranial pressure had been quite severe, the doctors weren’t sure how much permanent damage had been done.

Several hours later he showed signs of consciousness, so the corpsmen hurried to call the doctor. The patient groaned and asked where he was, since everything was unfamiliar. By the time the doctors came, he was fully conscious and cooperative. A few simple reflex tests indicated that he was not able to move his right arm, but his condition was much better than might have been expected.

Three of us nurses were assigned to special-duty care for our injured patient, in eight-hour shifts. I was happy to have the busier day shift. Soon our patient was well enough to be up in a wheelchair for several hours each day. Since he was right-handed, I soon began encouraging him to try to eat using his left hand, but he said it felt too awkward and that he spilled food too much.

Luckily he had a good sense of humor when I spread towels to catch any spills, and each day I insisted that he feed himself a little more of his meal before I wheeled him out on deck, where he enjoyed the sunshine and the change of scenery.

During this time I regularly massaged his right arm, with his doctor’s permission. I also had him frequently squeezing an orange to try to strengthen the muscles in his hand and arm. After about a week of this, he excitedly showed me that he did have some voluntary movement in his hand and arm. When the doctor came to see him later, he had a big grin as he showed how much movement he had regained. Everyone was delighted, and the patient gradually regained full use of his arm.

I grew up in a caring family that had the sensible religious beliefs of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, often called the Mormons. So when I was in the navy, I naturally declined to drink alcohol at any time. One time a friend coaxed me to go to the officers’ club with her, but I soon felt out of place since drinking seemed to be the main source of entertainment. Leaving was easy.

Later, on board my ship, it soon became apparent that I was the only nurse who never drank alcohol. This solved a problem, because when nurses were invited to attend captain’s dinner aboard another ship or a party on land somewhere, I always volunteered to stay on board in case of an emergency.

One time, in Honolulu, an officers’ party was planned on a large private plantation. As usual I did not get an invitation, but I planned to go ashore since no one was needed to stay aboard in port. But one of my best friends, the assistant chief nurse, said she was required to put in an appearance at the party. She promised that if I would only go with her, we could soon leave, so I finally agreed.

We enjoyed the colorful scenery and admired the large swimming pool. About the time we arrived, someone playfully pushed one of the officers into the pool, fully clothed. Obviously the party was well under way. My friend and I promptly changed into our bathing suits and jumped into the pool, where we swam alone for a while. I was glad to avoid those who were acting foolishly; apparently, my friend and I were the only ones who were sober. Soon my friend’s recently sunburned back began to hurt, so we climbed out of the pool. I was given some soothing lotion to rub on her reddened back, which gave her some relief. Back in uniform again, we were urged to eat. We had some delicious sandwiches, but I politely declined anything to drink, no matter how harmless it seemed. My roommate had already explained how some people liked to spike innocent-looking drinks to make people involuntarily drunk. Since I was so strong-minded, I’m sure I made many “happy” people feel uncomfortable, especially when they were behaving foolishly. Anyway, when my friend and I said we wished to return to the ship, we were happily told good-bye.

An important element of fighting a war is the need to provide effective medical care as soon as possible to the fighting forces. Medics and corpsmen travel with military units. MASH units and front-line hospitals care for the men as close to the fighting as possible. Hospital ships are another means of bringing effective up-to-date medical care within a short distance of the wounded. Such military platforms saw service in World War II, Korea, Vietnam, and again in the Persian Gulf conflict (Operation Desert Storm). Alice’s ship, the USS Consolation, was one of the first United States Navy hospital ships.

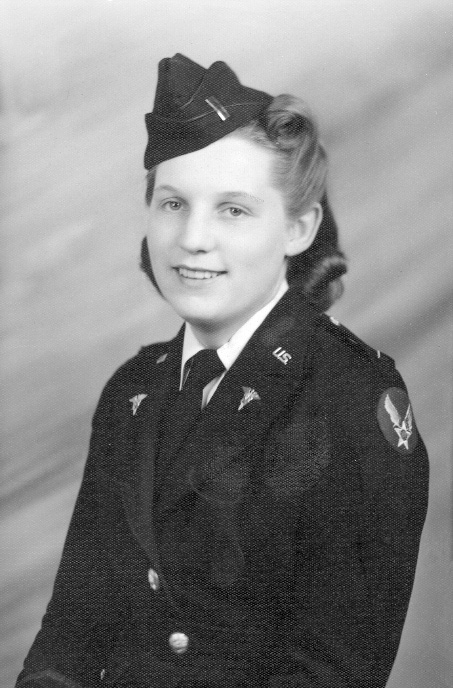

Virginia Scherbel Armstrong

Virginia Scherbel Armstrong

Virginia Scherbel Armstrong

I entered the Army Nurse Corps in April 1941 before World War II at the request of the Red Cross Nurse Association. I was assigned to Barnes General Hospital in Vancouver, Washington. When I arrived the hospital consisted of hastily constructed wooden buildings with ramps between them and a firewall running through the center. There were no patients or equipment. An administration group and army corpsmen who had been transferred from Fitzsimmons General Hospital in Denver, Colorado, were already there. These corpsmen were our technicians for the lab and x-ray, served as wardmen and cooks, worked in the motor pool, and performed many other duties. The doctors arrived at a later date.

Our first activities (with the help of the corpsmen, who had been trained in army hospitals) involved ordering equipment and supplies for the wards including chairs, cots, bedding, pajamas, robes, and other items, as well as dressings, bandages, and surgical instruments. Everything smelled of mothballs and had to be aired out and cleaned. Our first surgical instruments were all caked in wax and had to be cleaned of the wax before they were usable. We were told that all this equipment had been stored since World War I. Some instruments were familiar and similar to those we had used in our previous work, but some were completely different than any we had ever used.

Once the hospital was in some kind of order, we started receiving patients. Our patients were mostly transfers from post hospitals, like Fort Lewis in Washington and Fort Stevens in Oregon. Consequently, patients usually arrived in groups from a few to as many as seventy-five at a time. They were sent through the admissions area and then assigned to the type of ward they needed, such as ENT, urological, medical, or psychiatric. It was only a short time before the hospital was completely filled with patients suffering from a variety of illnesses.

I was the nurse in charge of an open psychiatric ward at the time of the bombing of Pearl Harbor. Patients who were out of bed went to the mess hall for their meals. My patients had gone for their meal but rushed back to the ward to tell me that Pearl Harbor was being bombed. I thought at first that they were kidding me as they always did, but when we turned on the radio, we heard the news of the bombing and later of the president, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, declaring war, December 7, 1941. Most of my patients wanted to be sent right back to service, and most of them were. However, the hospital was kept filled with patients from the posts, as it was filled even before war was declared. The hospital went on full alert and was soon painted camouflage, and our activities away from the hospital or post became restricted as to distance and type of activity.

I received my honorable discharge from the service in July 1942, so you see my army activity was limited. I did return to work at LDS Hospital in the nursery during the war years, which was plenty busy. I was also attending the University of Utah during that time.

Estelle Morrison Burton

I was a cadet nurse during World War II, and I went to Mary Hitchcock Memorial Hospital at Dartmouth College School of Nursing in Hanover, New Hampshire. We were privileged to be able to take some of our nursing classes at Dartmouth College itself, which made it especially nice. I graduated at the top of my class and received a scholarship to Simmons College in Boston.

I went into the navy hoping to become a flight nurse. The war was just over, and we were in what they call a “state of war.” My first assignment was at Jacksonville Naval Air Station. Because of some supervisory experience and my scholastic record, they put me right into head nursing and evening supervisory situations and threw the book at me. It was very challenging and very enjoyable—challenging because I did a lot of problem solving.

Back in those days nurses did not start intravenous lines. One day I was the head nurse on the orthopedic ward and they brought a black sailor back from the OR, which was three buildings away. He was in severe shock. I called a commander who was in charge of the unit and told him the situation. He said to give him so much Esgotin (I think it was called at the time) intravenously, stat [immediately]. I had never given an intravenous shot in my life. Medical residents and interns always started intravenous lines in those days. The patient was a very dark-skinned black man. All of the corpsmen gathered around the head nurse, and I thought, “I am going to lose face if I don’t hit this vein, and this man is going to die.” Thank goodness he had big veins. I felt boom, and in it went. It shook me up pretty good, but I didn’t let on. Esgotin was an adrenaline-type solution, and it brought his blood pressure right back up. I didn’t lose face in front of all of my subordinates. When the doctor told me to administer the shot, I said, “I don’t do that.” He said, “You do it. I’ll be right behind you.” I said, “Sure you will—three buildings away.” He laughed. He was a full commander and I was an ensign. He told me to do it, and I did it.

One day when I was still head nurse on the orthopedic floor, the phone rang, and it was the chief nurse, who said, “Miss Morrison, would you please give your narcotic keys to the nurse in the next building and come to the administration building. Is your narcotic count balanced?” I said, “Yes, of course.” She said, “All right, well, we’d like you to come over to the administration building please, after you give your keys to the nurse on the next floor.” I said “All right.” I turned around and right by my side was a hospital chief corpsman standing there. He said, “I’ll walk over with you.” Little did I know I was under arrest—nobody told me. So we walked across the lawn over to the administration building. They took me around the corner and there was a master at arms swinging his club, and he had a gun on and three men sitting in chairs outside of the administration building. They said, “You can sit right here.” I said, “Well, if I have to wait, I’ll go get paid,” and I went around the corner. He looked at me and he looked at them, and I guess he decided I was the best bet of the group to come back. I didn’t have any idea I was under arrest, so I went around, got my paycheck, and came back. The master at arms looked quite relieved when I came back.

They invited me into this room wherein sat naval intelligence. They are very important, and they were the only ones who were nice to me. The Florida Narcotics Bureau and the Jacksonville police were also there. They sat me in a chair and their opening statement was, “We understand you are addicted to morphine.” I said, “No, I’m not.” They said, “Well, roll up your sleeves so we can see the tracks on your arms” (navy nurses wore long sleeves). I said, “No, I’m not going to roll up my sleeves for you, but the chief of medicine has an office right across the hall, and if you want me to go over there and roll up my sleeves for him, I will be happy to.” I just didn’t like their attitude. They were flippant and almost rude, when I hadn’t done anything. So I went across the hall, and the chief of medicine looked at them and came back and told them, “No, there are no scars or tracks or anything on her arms.” They said, “Tell us every time you have had morphine since you were born.” I said, “At the very beginning?” “Yes.” So I decided I might just as well be deceitful as they were, so I said, “When I was five, I had my tonsils out, and I had a little pain and they gave me something, but I don’t know what it was.” I was just being obnoxious, because they were pushing my buttons the wrong way. I took them all the way through to an appendectomy at age twelve. Then they said, “We understand that you sold eight grains of morphine for $35 on the corner in Jacksonville, Florida, last night.” I said, “Number one, I wasn’t off the base last night; number two, I have never been on that street in Jacksonville; and number three, if I would have sold that morphine, I would have gotten a lot more than $35 for it.” I was a complete bust to them; they didn’t get anywhere. All I could think of was people who had been charged with something they didn’t do.

The naval intelligence officer had very little to say, and he was the only one who was extremely polite and courteous to me. The others were rude and crude and really annoyed me. But then they let me go. I didn’t know that day what the result was, but I found out the next day that they had caught three veterans’ administration patients who had come in from Cuba and had come across the fence into the Naval Air Station. They were the ones that had sold the morphine, but they had accused the nurse on the ward, and that was me. They were my outpatients.

In the navy you are sick until you are fit for duty. We had a ward with fifty-two patients. I actually had two wards; I had an orthopedic ward and a dirty surgery ward, and each had fifty-two patients in it. I also had one or two wards, it varied from time to time, of outpatients who would come in the morning for their medication. They lived in another ward; they weren’t well enough to go back to active duty, but they didn’t have to be on the sick ward. They were supervised by a navy chief. They probably didn’t have enough navy nurses to watch over them.

I was in Jacksonville from January 1948 to December 1948, and then my father became quite ill, so I had a hardship transfer to Massachusetts, and I was transferred to Chelsea Naval Hospital.

Leona Berg Campbell

Leona’s daughter tells her mother’s story.

Leona Berg Campbell, my mother, graduated from the Grove LDS Hospital Nursing School in 1923. She was a supervisor after graduation and for most of my childhood did private duty nursing.

In 1943 she and my father worked at the Topaz Japanese Relocation Camp about twenty miles outside of Delta, Utah. My father was the placement officer there, and Mom nursed in the hospital.

The hospital was a very modern facility with the most up-to-date equipment for that time. There were two Japanese doctors in the hospital, and my mom considered them tops in their fields. For example, after surgery they had their patients up and moving around shortly after their operations. This was a new innovation for Mom.

Those days in the hospital at Topaz were very happy ones for her. She told how clean and virtually scrubbed the mothers-to-be were when they came to the hospital for their deliveries and how she enjoyed taking the beautiful new babies to their mothers.

When she left the hospital after her 3:00 to 11:00 shift, it was a thrill for her to walk home and look up at the sky—the stars seemed so close to her out there on the desert.

Ruth Udy Dare

It was September 1943, and the war was raging in Europe and in the Pacific. LaRue and I went to see the movie So Proudly We Hail—a film about army nurses. That made our decision final to join the Army Nurse Corps. So we went up to Fort Douglas, Utah, and signed up and told them we would be available for assignment January 1944. We requested that we would be stationed together.

Our army life of twenty-four wonderful months began. The change in temperature from Utah to the Sacramento area was surprising to me. We took a late evening train to Medford. A bus took us to Camp White, which was five miles away.

We filled out papers of all kinds, learned our army numbers, and were given shots. We had our teeth checked, our eyes checked, and were issued two pairs of glasses as well as corrective lenses in our gas masks. We were put in a barracks with lots of other new army nurses.

We went to parties at the officers’ club, where LaRue and I were always the only ones not drinking and smoking. Sometimes it was fun, sometimes boring. I was thankful we had each other. One day I was summoned to the chief nurse’s office—I couldn’t imagine why. I was reprimanded for coming in late—drunk. This time I was innocent—a case of mistaken identity. It wasn’t easy convincing her of my innocence. I was pretty shaken by that experience.

For an extra week we worked eight hours daily in the hospital. We had six weeks to learn what the army was all about and received our orders to report to Sawtelle Station Hospital in west Los Angeles, California. The hospital was set up in domiciliary buildings used for World War I veterans, within walking distance of Westwood Village and near Santa Monica.

It was an exciting life for us. We went to church at Wilshire Ward when our work schedule would permit. We also went to Hollywood Ward a few times. I felt the Tabernacle Choir broadcasts were my link with the Church at that time. LaRue and I were good for each other and helped each other live the gospel even though we could not attend church regularly.

In March I was called home to take care of my sister Vivian, who had given birth to her eighth child at home without a doctor in attendance. She had developed a postpartum infection. It was my first plane ride and I was alone, worried, airsick, and scared. Family met me in Salt Lake City and took me to Cottage Hospital in Burley, Idaho, where Vivian was hospitalized. Penicillin, which would have cured her, was not available for civilian use. There were no antibiotics. She did seem to be getting better, so after two weeks I came back to California. She was still in the hospital, but my leave was up. The ironic thing is that I had been giving penicillin shots every four hours to soldiers with venereal diseases in the G.U. ward but couldn’t get any for my sister who needed it so desperately. She left eight children when she died about a week after I returned to Los Angeles. This was a very difficult time for my parents. They had now buried their firstborn child and had taken her baby—also named Vivian—to raise. Now they were worrying about my chances of being sent overseas. When I joined the army I assured them there was no chance that I would receive an overseas assignment because of my myopic condition and because they said I was underweight (116 pounds).

I was transferred to Birmingham Hospital when Sawtelle was closed. Birmingham was an extremely large complex, like a small city, located on Victory and Balboa Boulevards. After the war ended it became a VA Hospital and then a high school.

We were working very hard now, receiving convoys of patients from the China-Burma-Indonesia area—lots of psychiatric patients. Nurses were being sent overseas from Birmingham every week or so, and LaRue and I became worried one of us might go without the other. So we went and talked with the chief nurse and told her we would very much like to stay together—even on an overseas assignment. Our orders came in September to join the 81st Field Hospital. We were elated that we could be together.

On November 20, we were assigned to the 81st Field Hospital assembling at Camp Lee, Virginia. It was a long train ride. Camp Lee was about twenty miles from Richmond. It was a staging area where units were made up. The personnel for the 81st were from many different banks from San Diego. The chief nurse was Captain Eileen Donnelly from Massachusetts. We had 18 nurses, 22 officers, and 186 enlisted men. LaRue and I were the two youngest nurses.

On Sunday we found an LDS service in the camp. There were very few there, but we had the sacrament and a Bible study class—friends even though we were strangers.

We worked in the hospital while we were there and enjoyed the city of Richmond and the beautiful countryside. This was my first experience in the South, and I didn’t like what I saw—blacks in the back of buses, separate entrances, and so forth. This was all new to me, and I found it very distasteful.

On December 16, 1944, the 81st Field Hospital personnel boarded a train, and on December 24, 1944, we were taken to the New York Harbor. There we boarded the Vollendam, a former Dutch luxury liner, now a troopship. The crew was British. There were at least two-thousand infantrymen on board. Christmas Day was spent on board ship in the New York Harbor. On December 26, 1944, at 5:00 a.m., we moved out. When we awoke we were out at sea. We were with a big convoy of ships, including tankers and destroyers. We were headed for the European theater of operations. The North Atlantic in midwinter can be very rough. We zigzagged across, trying to avoid enemy submarines. Many times we would be aware of depth charges being dropped, indicating the presence of the enemy. That was nerve-racking but I felt an inner peace that all would be well. Some of our nurses were basket cases. We also encountered another enemy—the storms that blew up forty-foot waves, making it impossible to go out on deck. Many were seasick, including me. I felt a great deal of sympathy for the enlisted men in the hold of the ship in hammocks. Our food wasn’t that great. We ate lots of Nabisco sugar wafers, which we could buy at the ship store. We were onboard ship for nineteen days. On January 7, 1945, we arrived at Southampton, England. Here we received orders to cross the English Channel to the French port of Le Havre. This port had been completely destroyed. It looked burned and was still smoldering. We docked long enough for the two-thousand infantrymen to climb aboard the LST boats, their destination—the front lines. I thought how young those boys looked and wondered how many of them would return home. We headed back again across the channel to Southampton after playing cat and mouse with U-Boats. We finally made it around the west coast of England, ducking in at Milford Haven, Wales, to avoid submarines, and then running—or steaming—as fast as we could through the Irish Sea, docking in Gourock, Scotland, on January 13. At 3:30 p.m. we finally felt earth under our feet. After twenty-one days the 81st was in Scotland.

The next leg of our journey was a troop train to Beeston Castle, England, and then a bus to Oulton Park three miles away, near the city of Chester. It was very cold. We were dressed in fatigues—full regalia—and were carrying sleeping bags. Our luggage consisted of a bed roll, in which we had stashed everything we thought we would need for a year. Oulton Park was a series of Quonset huts. Each had a small stove in the center where we burned compressed coal dust. The washroom and toilets were in another Quonset hut. We preferred using our helmets and washing up around the stove in our hut.

We slept on double-decker cots with inflatable rubber mattresses, and the sleeping bags and warm cotton blankets we had brought from Richmond saved our lives. We stacked black woolen blankets on top of that. We wore more clothes at night than during the day. I always put a fancy nightgown over the other layers as a morale booster. We were lucky—our cot was close to the stove. We took turns getting up to keep the fire going during the night. We had lots of mail and packages from home waiting for us here.

On January 18 we went to London on a three-day pass. Westminster Abbey was badly bombed and damaged, and sandbags were everywhere to protect it. Each night air-raid sirens wailed, indicating German U2 rockets were being sent across the channel to bombard south England. The Red Cross served waffles and ice cream cones—a taste of home. I was so happy to be there and see all the places I had heard about.

When we returned to Oulton Park we found the latrine frozen up. It was the coldest winter in England in eighty-two years. Our stovepipe plugged up. We couldn’t get our fire to burn, so we went to bed to get warm. Finally some of our boys came and cleaned it out for us. There were soot and ashes everywhere, but we were warm again.

Our hospital [unit] had been divided into three platoons. Each platoon had six nurses, seven officers, and sixty-two enlisted men. LaRue and I were in A Platoon. Each platoon could function on its own if necessary. On January 24 A Platoon nurses were assigned to the 109th General Hospital near Liverpool. We stayed there until March 11. We were working ten hours a day. Our uniforms were brown and white striped seersucker with field shoes and olive drab wool socks. We didn’t look very glamorous, but the boys didn’t seem to care. They were great patients and helped us a lot if they were able to be up and about. We were taking care of some boys who were left off our ship at Le Havre. They had been up to the front and were wounded. Seven hundred of those boys who were on the Vollendam were killed in a train wreck the same night they got off our ship. We loved taking care of the soldiers. We had been in the army fourteen months and had enjoyed every bit of it.

On March 11 our whole unit moved back to Oulton Park. On March 21 our hospital unit left Oulton Park, traveled by train for eight hours to Salisbury, then went by truck to a staging area called C-5. This was an area for units shipping to the continent. This time it was for real. We were headed for the real war—the combat zone. On March 25 we left Southampton on board a ship called the Dobrieske. It was a Polish steamer with a U.S. Navy crew—a ritzy ship with deluxe cabins and wonderful food. It was an overnight ride across the channel to Le Havre, France. From there we took an overnight train ride to Paris. We spent the whole day in the Paris train station. We were in combat dress including helmets and were not allowed to leave the station. We ate K-rations for all our meals that day. K-rations were dry foods packed in a box about the size of a Cracker Jack box. There was one for breakfast, one for lunch, and one for dinner.

We left Paris by train on March 27 in the evening, traveling to Luneville, which is near the city of Nancy. It was 2:00 a.m. on March 28, and our unit was headed for Mannheim, Germany. We traveled in eighteen 2 1/

We were near the Rhine River as dusk approached. At Ludwigshafen we seemed to be obstructing the passage of an armored tank division. Their commander asked our Captain Corley, in charge of our unit at the time, what we were doing there. Captain Corley explained we were on our way to Mannheim. The tank commander replied in disgust, “You’d better wait until we capture it.” Some of our nurses stuck their heads out at this time, and the commander looked at us and said, “Wouldn’t you know, a bunch of women.” We didn’t care for his reaction, but chances are he saved our lives. Our orders had been misinterpreted. We were to go to Marnheim, not Mannheim. The tank commander told us to go about twenty miles northwest. We had no map. We were driving in blackout. The bridges had been bombed. The Germans had turned road signs around so the allies would have a difficult time getting to their destinations. We were driving in circles. At 11:00 p.m. we were in Golheim. We went across fields, through streams and barnyards with cows, chickens, and pigs. At 1:00 a.m. we were back in Golheim again. We got into areas where we couldn’t turn around and had to back all the trucks out to where we could move forward. Ted, a member of our company, had a compass and offered to try to get us to Marnheim. It was a moonlit night—he would walk into a town and see what was ahead and then come back and move the convoy. He finally found a station hospital set up in tents. They gave him a map. He got us to Marnheim about 3:00 a.m. It was now pouring rain, and we waded in mud up to our knees. We slept the rest of the night in an old building on cots with two dirty army blankets, near the 27th evacuation hospital.

The next day, March 29, in Marnheim—that elusive city—our own tents were set up and we were cozy with our sleeping bags and air mattresses. Candles were our lights. In two more days we had electricity from our own generators and stoves in our tents—even violets growing on our floor. We heated water in buckets and were allowed a helmetful for a bath at night. Our unit was attached to the 7th Army here, and we were waiting for orders. On April 5, we moved to Dieburg, about forty-five miles from Marnheim. We crossed the Rhine River on a pontoon bridge at the city of Worms. This city had no buildings standing—just rubble, dust, and dirt. We witnessed total devastation of homes and countryside as we traveled over bomb-pocked roads in the backs of ambulances. German people pushing little carts containing their only salvageable possessions were everywhere. In Dieburg we set up our hospital in tents; our living quarters were also tents. An expression of the enlisted men, whose job it was to set up, was “pitch, ditch, and bitch.”