World War I

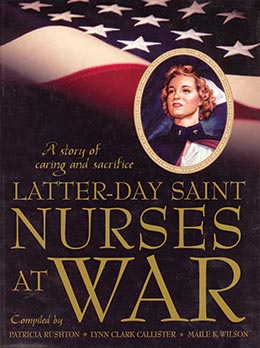

Patricia Rushton, Lynn Clark Callister, Maile K. Wilson, comps., Latter-day Saint Nurses at War: A Story of Caring and Sacrifice (Provo, Utah: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2005) 9–12.

The twentieth century was a time of great conflict during which the United States fought in six major military operations: the Spanish-American War, World War I, World War II, the Korean War, the Vietnam War, and Operation Desert Storm (the Gulf War). In World Wars I and II, as in the Crimean War and the U.S. Civil War, there were more deaths from disease than from combat wounds.

Historical Background

Even before the United States entered World War I, the Red Cross recruited nurses and sent them to the battlefront (Baer 1987). Then, when the United States entered the war, the surgeon general charged the American Red Cross to recruit nurses to serve American troops in France. Their motto was “American Nurses for American Men.” In spring 1918 the Red Cross was charged to recruit eight thousand nurses for service to American soldiers. These nurses were outfitted by the Red Cross in uniforms that came to be a familiar image, complete with the Red Cross cape with red lining. These nurses were often housed in Red Cross facilities and supported overseas by the Red Cross (Bledsoe 1997).

Another route was to apply directly to the Army Nurse Corps. Sarnecky notes, “From July to November of 1918, 9,200 new Army nurses joined the corps, another 4,700 transferred overseas, and approximately 1,500 arrived at the Port of Embarkation waiting for transportation” (1999, 92). The army and Red Cross shared responsibilities for care throughout the theaters of operation (Sarnecky 1999, 99).

In 1916 the army and Red Cross collaborated to form fifty base-hospital units. Their staffs were drawn from the large hospital staffs of established civilian universities such as Princeton, Yale, and Harvard. It was felt that units formed in such a manner would have an inherent sense of staff cohesion combined with advanced professional training. This would lead to quicker mobilization and more efficient medical service (Sarnecky 1999, 80–81).

Travel was by train and troopship. There were two million American soldiers in Europe at the end of World War I and twenty thousand Red Cross nurses who joined the Army Reserve to care for the 230,000 wounded Americans (Bledsoe 1997). One hundred ninety-eight nurses died in World War I, many from disease rather than combat-related conditions (Beeber 1996).

The conditions under which nurses worked in the field during World War I were terrible. Hoskins describes battlefront conditions for British soldiers during the Battle of the Somme:

They took the wounded soldiers to the regimental first-aid post, which was situated about 100 yards behind the trenches. The regimental medical officer then performed the first triage by separating the walking wounded . . . from the severely wounded. . . . The seriously injured were moved on to dressing stations run by the RAMC field ambulance. . . . Here a second triage of the wounded took place, which included the provision of rudimentary first aid, such as antitetanus jabs and the application of field dressings. Very severely wounded soldiers were separated to one side and left to die.

On the first day of the Battle of the Somme, the bodies were piled high in rows as the true extent of the tragedy unfolded. . . .The full complement of nursing staff, which covered several tents, usually consisted of a sister, a staff nurse and two Voluntary Aid Detachments (VADs), which was grossly inadequate for the task in hand. . . .

Surgeons worked on five or six operations simultaneously, and nurses found themselves participating in procedures they were not qualified to carry out, such as the administration of anaesthesia and the closing-off of amputated limbs.

The only analgesia that could be offered to quieten the cries of the wounded was aspirin or morphine. There were no antibiotics to administer prophylactically to prevent gas gangrene, which subsequently accounted for 80% of arm and leg wounds resulting in amputations. (1998, 15)

Instead, nurses continually carried out irrigation of septic wounds in an attempt to prevent gas gangrene, which in the early stages of the war killed as many British soldiers as the bullets themselves. Millard describes the horror of caring for patients who had been exposed to mustard gas:

Mustard gas produced profound burns and lung damage. Gas cases are terrible. They cannot breathe lying down or sitting up. They just struggle for breath but nothing can be done . . . their lungs are gone . . . literally burnt out . . . some with their eyes and faces entirely eaten away by the gas, and bodies covered with first degree burns. We try to relieve them by pouring oil on them. They cannot be bandaged or even touched. . . . One boy, today, screaming to die. The entire top layer of skin burned from his face and body. I gave him an injection of morphine . . . he was wheeled out just before I came off duty. (Quoted in Beeber 1996, 24)

Long hours, the short staff, and the multiplicity of terrible wounds had their effect on nurses. “As L. Herrick, RN, who had served in Contrexieville, France, put it . . . ‘the experience made me different from nurses, and from other women I knew . . . so different that when I returned, for a long time I felt lost—I didn’t fit in anymore’” (Beeber, 23).

Letters home from France during World War I expressed love for home, country, and the American soldiers who were fighting in the war:

The letters reflected the themes of love of country and of the American “boys” who were protecting that country. The nurses projected this sentiment as their reason for being in whatever camp or hospital they served: “What a great privilege it is to be here and take care of our dear American boys”; “our boys deserve everything that can be given them, they are so unselfish always thinking of the boys they left behind and they are the bravest things . . . they have the spirit of 1776 born right in them”; “we can never understand or appreciate what our men, or the men of any other country really undertakes when they are called to arms, until we really live in the camps and know their privations.” (Baer 1987, 23)

Letters to St. Vincent’s Hospital in New York City refer to the many non-military conditions affecting the troops and the nurses. The military had no experience with housing or caring for large numbers of people. The men lived in open tents. Fire was a constant threat and often destroyed hospital and troop property. The troops were exposed to such diseases as measles, with its associated pneumonia, mumps, scarlet fever, and influenza, and the flu pandemic of 1917.

Many nurses were required to stay in the United States to care for men here, thus making it possible for other nurses to go to the front and for more troops to be shipped overseas. One nurse wrote, “There are some among us who, perhaps, will never experience the excitement of life near the ‘front’ but will remain quietly behind somewhere and accept whatever of duty that comes our way” (Baer 1987, 19).

Accounts of Agnes Climie’s war experience in France were much different in her journal than in her letters home. The letters did not describe the terrible rations and living conditions, the frequent air raids, or the sorry state of the soldiers brought into the hospital from the front. The journal notes that water was carried in buckets, that there was no way to boil water to sterilize it, and that wounds were dressed in cold carbolic lotion and unsterilized gauze and wool.

The actions of nurses during World War I had an impact on the passage of women’s suffrage in 1918 and the passage of the British Nurses Registration Act in 1919 (Lorenzton 1995, 28).

Only one account of a Latter-day Saint nurse who served during World War I is currently available to this project. The following experience was contributed by the nurse’s family.

Dora Maiben

Dora was always interested in caring and healing. In May 1906, at age nineteen, she entered training at LDS Hospital in Salt Lake City, Utah. Students were paid ten dollars a month for the three-month nursing course.

During World War I, the Red Cross was in desperate need of trained nurses. Dora spent one year at Fort Bliss and Fort Sam Houston in Texas as a Red Cross nurse. As the war was drawing to a close, Dora’s group was sent to Europe.

Dora was assigned to Mobile Unit Two, stationed in France. Dora belonged to the Princeton Unit. After arriving at the front, the units would leapfrog each other in truck convoys. As a unit arrived to a new location on the front, they would first evacuate the wounded who could be moved and then set up hospital tents and equipment for the next group to care for the immobile.

Amid the blood and tumult of the fighting of the Argonne Forest (September–November 1918), one of Dora’s tasks was to determine which of the wounded had a chance of being saved if quickly transferred by ambulance to a field hospital and which had little or no chance.

After the war ended on November 11, 1918, Dora was transferred to Koblenz, Germany. She worked at Medical Occupation Hospital 29, caring for the American occupation forces from December 1918 until August 1919. Dora gained a reputation among the soldiers for being very matter-of-fact as to what was expected of them. As she approached one of the wards, she heard the hushed warning going around, “Better get back to bed. Here comes Reddy.”

Dora was then sent to the Balkans, specifically Serbia near the Turkish border. She worked in a Red Cross school and children’s clinic. An epidemic of childhood diseases broke out. In a cart pulled by a donkey, Dora would travel to the outlying rural areas to treat the children. It was in Salonka, Montenegro, that Dora felt she did the most good. The orphanage there was in terrible shape. The children were covered with sores and scabs on their scalps and skin. Dora found that even a simple gift to a child went a long way. To one little girl, Dora gave a set of underclothes. The little girl was so proud that she wore them over her other clothing for all to admire. On occasions when Dora would stay at a private home while traveling, the locals were so interested in this western woman that they observed and examined everything, from her actions to her clothing. The local people seemed very grateful for the healthcare provided. Children often ran ahead of the nurses, calling, “Merican Nursee.” The occupation forces also set up soup kitchens for the locals, providing cereal and hot cocoa. The empty milk cans from the States were saved to make cups for the people.

Dora returned to the United States and worked at the Salt Lake City, Utah Board of Health. Until her retirement at age sixty-five, Dora spent many years as a school health nurse and was remembered for her tireless efforts and concern for the health and well-being of others. Dora passed away on March 11, 1978, at the age of ninety-one.