The Vietnam War

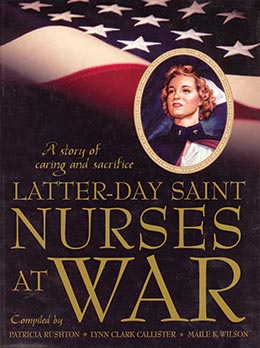

Patricia Rushton, Lynn Clark Callister, Maile K. Wilson, comps., Latter-day Saint Nurses at War: A Story of Caring and Sacrifice (Provo, Utah: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2005) 161–197.

Historical Background

The military involvement of the United States in the affairs of Vietnam the administration of five U.S. presidents and almost thirty years. In 1945 the Truman administration provided aid to the French who were trying to maintain their Vietnamese colony from Vietnamese rebels led by Ho Chi Minh. Eisenhower believed in the domino theory. Roarke (1998) quoted Eisenhower: “You have a row of dominoes set up. You knock over the first one, and what will happen to the last one is the certainty that it will go over very quickly” (1067). Roarke noted that Eisenhower “warned that the fall of Southeast Asia to communism could well be followed by the fall of Japan, Taiwan, and the Philippines” (1067). By 1954 the U.S. was providing 75 percent of the cost of the war to the French. However, Eisenhower stopped short of providing troops to the French. France was defeated and signed a truce in 1954. This truce created the countries of North and South Vietnam. Kennedy continued to provide support to the government of South Vietnam and ultimately supported South Vietnam in the conflict between the two nations, providing troops and materials. Johnson continued the support, making the Vietnam War “American’s War.” Again Roarke commented:

The Americanization of the war increased the number of U.S. military personnel in Vietnam to 540,000 at peak strength in 1968 and to more than three million total throughout the war’s duration. Yet not only did this massive intervention fail to defeat the North Vietnamese and their allies in South Vietnam, but it added a new burden to the costs of fighting the cold war—intense discord among the people at home. Believing that the war was immoral or futile, hundreds of thousands of Americans protested it. (1138)

Nixon was president of the United States when the formal accord ending the conflict in Vietnam was signed in Paris in 1973.

During the Vietnamese conflict, hundreds of thousands of U.S. military troops were being sent overseas to fight on the front. One of the most important aspects of a military conflict is the ability to care for the casualties at the front, transport the critically wounded to adequate medical facilities, and return those well enough to the battlefield. Militarily savvy people have known this since the Crimea, when the British sent Nightingale to care for the troops. They have known it since the Civil War, when most of the casualties resulted from disease and inadequate patient care. It is the reason people like Bickerdyke, Dix, and Barton were accepted at the battlefront. It was obvious in World War II, when the Cadet Nurse Corps was formed to provide nurses to care for the troops. During the Vietnamese conflict, when hundreds of thousands of U.S. troops were being sent to Indonesia, it was clear that health care providers were essential. Male physicians were drafted and sent to the front, and nurses were heavily recruited. The Nurse Corps Candidate Program was instituted, a program similar to the Cadet Nurse Corps of World War II.

Possibly more nursing literature has been written about the effects of war on veterans and nurses from the Vietnam War than any other. As noted above, it was America’s War. It is the war remembered and experienced on some level by most Americans over forty years old. What happened there will impact Americans for generations. It is impossible to review in this work all the nursing literature concerning nurses serving in Vietnam. Perhaps two summaries of the conflict will provide a sense of what nurses endured. The first is from a 1995 edition of the Nebraska Nurse, the official publication of the Nebraska Nurses Association:

The Vietnam War started insidiously. Although American military advisors were a presence in the area from 1945, their numbers escalated. . . . No one is exactly clear about how or why but the numbers grew steadily after that until the early 1960s, when thousands of American soldiers were involved.

The first American military hospital was established in 1962 and the number of military personnel and nurses grew steadily until the war was halted in 1973. Initially female military personnel were not “in country” but soon the need for nurses outstripped the number of male nurses available.

In the end, over 250,000 women had served, 11,500 of whom actually served in Vietnam, or “Nam” as it came to be known. Women worked as clerks, mapmakers, intelligence specialists, photographers, air traffic controllers, Red Cross and USO volunteers. But the largest number of women in uniform were nurses, sent to care for soldiers and civilians in hospital beds that grew in number in 11 years from zero to 5,283.

Air Force, Army, and Navy nurses served on helicopter med-evac flights which lifted-off directly from the battlefield, in inflatable hospitals in tenuous settings within Vietnam, on jet med-evac missions that picked up battlefield casualties from units in Vietnam and delivered them to hospital centers in the Philippines, Japan, and Okinawa for stabilization before the long flight home.

Women of the Army Nurse Corps averaged two years service in Vietnam. Many were novices—only 35% had more than two years nursing experience when they left the US. Army nurses were 79% female, some were married, most were not. They served a 12 month tour of duty often living in tents and quonset huts. The quarters “leaked, were bug infested, noisy, and almost always humid.” Some stabilized war wounded GIs in transportable, inflated “buildings” which posed constant problems with maintaining electricity and drainage.

While nurses at more permanent sites wore white duty uniforms, most others wore lightweight fatigues. Nurses worked a six day week, in twelve hour shifts, “except during emergencies when everyone worked.” Hospital-based nurses were deployed to surgical ICUs, recovery and emergency rooms, and in med-surg areas.

As in other wars, hospital admissions for disease outnumbered battlefield injuries. Diseases commonly treated were malaria, viral hepatitis, and diarrheal, skin, and venereal diseases. The most common diagnosis was FUO–Fever of Unknown Origin.

The length of stay of battle-wounded soldiers was shorter than in previous wars due to the availability of whole blood, rapid aerial evacuation, and advanced medical and nursing procedures. The hospital mortality rate was 2.6% per 1,000 compared to 4.5% per 1,000 during World War II.

The war that began insidiously somehow ended. It was not a popular war, many refused to serve, and those who served, nurses as well as soldiers, came home to find their service was, by and large, not appreciated. The Vietnam War is a wound slow to mend. The first sign of healing was construction and subsequent appreciation of the Vietnam War Memorial Wall, known to many veterans as “the Wall.” The 10 year struggle and dedication of the Vietnam Women’s Memorial is an indication that the tours of duty by women as well as men are now honored. The scar tissue of that “ugly little war”, although still tender, is forming. (Nebraska Nurse, 1995)

The second account is that of author Elizabeth M. Norman, summarizing the gathering of the accounts of fifty nurses who had served in Vietnam:

The nurses’ professional and personal experience in Vietnam was complex. It was a year involving difficult and rewarding nursing situations and dangerous and satisfying personal situations. Their twelve month tours were divided into three periods: the first three months of adjustment, the middle six months of routine when Vietnam became familiar, and the final three months. The final three months were an ambivalent time. The women wanted to go home but they were torn by the friends they would leave behind.

The stressful experiences of the nurses in Vietnam were not very different from those of nurses in other wars. The youthful age of the patients, the severity of injury seen, the lack of progress information on transferred patients, the death of friends, the unpreventable deaths, working with wounded enemy patients, and the triage system all proved difficult. Often the stress was balanced by friends, patients who recovered, and the ability to practice and be respected for their nursing skills.

Two factors, the branch of military service and the year served in Vietnam were responsible for different patterns in the wartime nursing experience. Each service had a unique practice environment—shipboard, aircraft or land based—that resulted in disparate environmental and combat dangers. Those nurses who served in Vietnam early in the war, 1965–1967, worked with traditional battle injuries and enjoyed some level of support from home. Those nurses in Vietnam during the peak of fighting, 1967–1970, experienced more triage situations and enemy attacks at the same time people began to openly question the purpose and wisdom of the war. By 1970–1973, nurses worked with more self-inflicted wounds and drug overdoses. It was hard to maintain morale and be a participant in an unpopular war.

More nurses returned home with a stronger commitment to the profession. They were convinced that nursing could have a direct impact on patient care. The decision to remain in critical care work, however, varied greatly. Over half of the fifty nurses decided to leave this specialty area for work in clinical areas where there would be fewer dying patients and injured young people.

The level of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder decreased from their first year home when over 30% reported high level of distress to a level of 14% at the time of the interviews. The nurses at greatest risk for PTSD included those who experienced more personal danger and professional stress in Vietnam, and those women who did not have a strong social network after the war. An examination of PTSD, however, does not provide a complete portrait of the nurses’ reaction to serving in the war.

Vietnam was unique in their lives. Nothing before or after compares with the stresses and the rewards of serving overseas. Because of its uniqueness, the war continues to be a focal point with which the other life experiences are compared (Norman 1992).

Anonymous

When I was a little girl, my grandmother was hospitalized with appendicitis. I thought her nurses were wonderful. They were very attentive to her needs and sometimes even let me help with her care. It was then that I decided to become a nurse. During high school I was a “pinky,” volunteering at the hospital. Sometimes there was just a nursing student and me to take care of a whole floor of patients. I loved the work and never wavered in my decision to be a nurse.

I received my BSN from Cornell University–New York Hospital School of Nursing in 1966. I joined the Army Student Nurse program for the last two years of my education, with a commitment to serve on active duty for three years. My first duty assignment was at Walter Reed. I had married a few weeks after graduation, so my husband and I moved to Washington DC. I had been assured by my army recruiter that I would be assigned to a post where my husband would be able to accompany me. Too late I discovered that the army had no intention of keeping that promise. Walter Reed was a wonderful arena for learning the practical skills that had not been taught at Cornell. Unfortunately, seven months later, I received orders for Vietnam. I shipped out, and my civilian husband stayed behind. We grew apart during that year, and the marriage ended soon after I returned.

My first duty station was the 67th Evacuation Hospital in Qui Nhon. I arrived in September 1967 and served there for three months. Mostly I was assigned to medical wards or the POW ward. In the 67th the POWs were kept in a separate ward. We had both medical and surgical patients in the POW ward, which was challenging from a nursing perspective. However, I did learn many skills that would help me later. The care of patients with malaria, hepatitis, and multiple gunshot wounds was not stressed at Cornell. Nursing in Vietnam was definitely on-the-job training!

In December 1967, I was one of several nurses who volunteered to transfer to the 71st Evacuation Hospital in Pleiku. Pleiku is in the central highlands of Vietnam, very close to the Montagnard villages where special forces operated. Some units a few miles north of Pleiku were taking heavy casualties, and more nurses were needed to handle the large influx of patients. In Pleiku I was assigned to the post-op unit in the surgical “T.” This building was designed in the shape of a T to facilitate handling multiple patients arriving at the same time. The ER/

triage area was in the vertical part of the T. A hallway connected the ER/ triage area to the six-bed OR located in half of the horizontal part of the T. Patients were lined up in the hallway to await their turn in the OR. From the OR patients were sent to post-op, which was located in the other half of the horizontal part of the T. Post-op was a thirty-six bed unit with eighteen beds for a recovery room and eighteen beds for surgical intensive care. Working there was a very challenging nursing experience. We were always busy but were usually well-staffed with all the supplies and equipment we needed. The only time we had a supply problem was when a short round, aimed at one of the military installations near us, blew up our water supply. Until it was repaired, we had no clean water. We brushed our teeth and administered medications with soda, beer, or whatever clean liquid was available. The patients in post-op were the most severely wounded in the hospital. Our job was to stabilize the patients and evacuate them to hospitals in Japan or the Philippines. After that we rarely found out what happened to them. Sometimes our patients got well enough to be sent back to their units. At those times we wished we hadn’t done our job quite so well. Sometimes our patients died, although not as many as one would suppose. Medical care at the 71st was the best I have ever seen. For me, nothing in civilian life could ever equal the level of care we were able to give at the 71st. Of course, no one had a life outside the hospital to distract us from our mission. If we needed a doctor or more nurses and corpsmen, we went to their hooch and woke them up. If they weren’t there, we would check the clubs or the other hooches, which were gathering places for bridge games and other fun activities. Even after exhausting twelve-hour shifts, almost everyone was willing to come back to help out when needed. Our ward was the only one in the hospital with regular hospital beds with side rails. This was because our patients were too sick to get under their beds if an alert was sounded. We went on alert frequently because of our location, which was in the middle of a triangle made up of the Pleiku airbase, engineer hill, and artillery hill. When an alert sounded, almost always in the middle of the night, we would put on flak jackets and helmets, put tree branches across the side rails, and throw an extra mattress over the tree branches. These mattresses were to protect the patients from falling debris in the event of a direct hit on the hospital. The staff would get under the beds of the sickest patients and creep out with flashlights to render needed care. As the assistant head nurse, I was in charge from 7 p.m. until 7 a.m. The head nurse was in charge from 7 a.m. until 7 p.m. There was one policy on the post-op ward that I never agreed with. The POWs were placed in whatever bed was available—sometimes in the bed next to a soldier wounded in the same firefight. POWs were to be given the same level of care that was given to the United States soldiers and Allied troops. I found that policy especially difficult when many wounded arrived at the same time, and all our time and skills were needed to care for our own guys. We knew that if the POWs got better, they would be turned over to an interrogation team. Nobody on staff knew exactly what happened in those interrogations, but many rumors circulated suggesting that these guys were going to end up dead anyway. It seemed like a waste of time and resources to go to extraordinary means to patch up the POWs. Of course, we did try to give them good care because that is what nurses do, regardless of the patient’s politics. I always felt sorry for our soldiers, though, when they realized the guy in the next bed was one of the enemy soldiers.

Many of my experiences on the post-op ward were memorable. There are some experiences that are difficult to talk about, even thirty years later. There was a fourteen-year-old civilian Vietnamese boy who had lost a leg in a firefight in his village. The surgeons amputated his leg below the knee. He could have lived, but he didn’t want to. One of our Vietnamese workers told us that he would not be able to survive in his culture with a prosthetic leg. He refused to eat or cooperate with his care in any way. He just gave up and he died about a week later.

One of our U.S. soldiers had his arm amputated above the elbow. It was very difficult for the staff to take care of him. He would throw his food and bath water at anyone who came near him. He also would shout curses and threats that were very disturbing to other patients as well as the staff. On the day we had finally had enough of his behavior, I was determined to break through his rage. My goal was just to get him to stop his verbal and physical assaults on everyone around him. I pulled a chair up next to his bed and told him I was going to remain there until he was ready to talk about his feelings instead of acting out in inappropriate ways. It took three hours of silence, periodically broken by episodes of salty language, but he finally opened up. After three hours he began to sob. He reluctantly let me hold his hand. When the sobbing subsided, he began to talk about his anger and his fear of facing life without part of his arm. He was afraid of losing his girlfriend and being unable to have a fulfilling career. The emotion just poured out of him. That was the first of many hours we spent together talking about his future. He became more cooperative with less acting out in negative ways. By the time he was evacuated to the Philippines, he had become a staff favorite.

There was another memorable patient who was in a coma for three weeks. He had a head wound and didn’t respond to any stimuli. His condition was much too unstable to evacuate him. One night we were on alert status with all the lights out. We could hear the sound of rockets whistling overhead and the loud booms when they landed. I was under his bed when all of a sudden I heard cussing. The corpsman under the next bed and I scrambled out, and sure enough our comatose patient had awakened to the sounds of incoming rounds. His condition continued to improve, and he was eventually evacuated to the Philippines.

There was one patient that I became way too close to. A few docs, nurses, and other personnel were having a cookout when we heard several incoming medevac choppers. We all ran to the chopper pad, offloaded the patients, carried the litters to the triage area, and began the protocol for handling multiple wounded. Some were so severely wounded that we knew we could not save them. They were moved to an isolated area with a nurse and a corpsman who would administer pain meds and try to keep them as comfortable as possible until they died. Others were prepped for surgery and lined up on gurnies in the hallway in the order they were to be taken into the operating room. We had only six operating tables, so sometimes patients had to wait. Minor wounds were handled in the triage area. Later that night during my regular shift, I received a patient from the operating room who had multiple wounds from a fragmentation grenade. I later found out he was from North Carolina and had a wife and two children. When we got him cleaned up, the wounds didn’t look so bad from the outside. We knew he was in serious trouble, however, because some of his frag wounds were to the chest. Wounds from a high-speed projectile entering the chest cavity frequently resulted in a condition called wet lung, which, in 1968, was usually fatal. The patient’s lungs gradually filled with fluid until he could no longer breathe. These patients initially feel very fortunate because they made it to the hospital and through surgery. With pain medication they were comfortable and anticipated recovery. Toward the end of my tour, we had learned to manage wet lung more effectively, but for this soldier that would be too late. We worked as hard as we could to save him, but ultimately we failed. At first, he was happy and fun to be with. We played games and wrote letters to his family. He loved to talk about life back in North Carolina and what he planned to do when he returned home. His surgeon and I became very close to this patient. As his condition deteriorated, we put in a chest tube. When that was no longer effective, we put in a trach tube. By that time he no longer thought he was going to make it. He would cover his trach tube and talk about never seeing his family again and what it would be like to die. Soon he became incoherent and sometimes combative. He needed arm restraints to keep him from pulling out his trach tube. One night he succeeded in removing the trach tube and was able to say a few words as I reinserted it. He called me by name and begged me to let him go. Putting that tube back was the most difficult thing I have done in my nursing career. I put the tube back in, and he lived two more days. That decision haunts me to this day. The surgeon and I were sitting with him when he died. Because we were still learning about the pathology of wet lung, the surgeon wanted to do a partial autopsy of the chest. I assisted with that procedure too. It didn’t seem right to allow anyone else to do it.

It was around this time that I started taking uppers to stay alert during the long twelve-hour overnight shift. I was already having trouble sleeping, so downers became more and more necessary as time went on. I told myself the drugs were necessary to keep me functioning at a high level. They did not become a habit at that time, and when I was transferred to a malaria ward, I no longer needed them. On the malaria ward I was the head nurse working days in a less stressful environment. Unfortunately, the groundwork had been laid for a more serious problem later on.

It was on the malaria ward that I cared for a very sick little Vietnamese boy. It was a few weeks after Tet (Vietnamese New Year) of 1968. Some marines were delivering clothing to an orphanage. They saw an unconscious child on the floor with a partially eaten rat in his mouth. They picked him up, brought him to the medical ward, and put him in my lap. We didn’t think we were going to be able to save him. He was severely malnourished and had multiple medical problems, including intestinal worms. His abdomen was swollen, and his eyes were swollen shut. When the swelling subsided, we discovered he was blind in one eye. He had a very flattened affect, probably due to emotional and psychological problems. We found out later that he spent three days in a hooch with the bodies of his parents, who had been killed during the Tet offensive. The other patients would try to make him smile by blowing up surgical gloves and drawing funny faces on them. We had our Vietnamese workers try to talk with him. We tried everything we could think of to encourage him to interact with us. Nothing worked for several weeks. Gradually his health improved, but he was still withdrawn and uncommunicative. One night the patients and the boy were watching The Lone Ranger on TV. There was a lot of gunfire in the show. Suddenly the boy started to act out the gunfight. Other patients joined in, and soon about fifteen guys were running around the ward having a pretend gunfight. Although others were participating, the boy seemed to be in a world of his own. Everyone stopped to watch him because the sight was so mesmerizing.

Apparently, he was able to work out some of the pain through playacting, because from that time on he began to communicate with us. We brought back the Vietnamese interpreter and finally learned about some of the horror he had experienced. His health continued to improve, and he began to speak English. No one wanted to send him back to the orphanage, so we kept him. At that time Americans were not permitted to adopt the children.

He continued to live at the hospital, even though many of the staff had completed their tour of duty and returned home. I was able to keep track of him for a while after returning home. Eventually however, the hospital closed down and I lost track of where he was. I was in graduate school at the time, but I reenlisted to return to Vietnam to find him. Rules had changed by 1970, and adopting Vietnamese orphans was now permitted. I was never able to find him, even with the help of several army units. I hope he was adopted and brought to the United States because, as Americanized as he was, I don’t think he would have been allowed to live after the fall of Saigon.

I joined The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints a few weeks before I returned to Vietnam for my second tour. I was divorced from my first husband soon after the completion of my first tour and was living with my parents while I awaited my orders. The missionaries were tracting in our neighborhood. They found me working in my mom’s flower garden. I told them I was interested in learning about their church, but there was no chance that I would be baptized. I didn’t know anything about the “Mormon” Church and was simply curious. When we reached the discussion of the plan of salvation, I was intrigued. It seemed to be what I had always believed, even though I had never heard it before. It just felt right. I had always been active in another church, but I remember sitting in church on Sunday thinking there had to be more to it than what I was hearing. Why did we go to church on Sunday and forget about it the rest of the week? After that lesson with the missionaries, events happened very quickly. I hurried through the remaining discussions and was baptized two weeks before I left for my second tour in Vietnam.

I arrived at my first duty station in Da Nang. There was an LDS congregation in the town, but I had no transportation to get there. For a few weeks I was able to borrow a staff car from one of the officers who was trying to help find my orphan boy. That luxury ended, however, when it was discovered that a nurse was driving a staff car. I was soon asked to play the organ at a nondenominational service on the base. I began to fall further and further away from the LDS Church and the values encompassed within it.

My second tour in Vietnam, which was in 1970, is largely a blur. I was unable to find the boy I was looking for. Many of our patients were being treated for drug overdoses, self-inflicted wounds, and sometimes wounds inflicted by each other. Morale was low in many units. American troops were being withdrawn and the war was being turned over to the South Vietnamese army, with Americans participating only as advisors. The combat-wounded patients that we saw frequently told us they would not have been wounded if South Vietnamese troops had functioned as they had been advised to by their American counterparts. It was a very discouraging time for many of us. Unfortunately, I responded by resuming the abuse of medications. I would write prescriptions to get the drugs I wanted. It was never necessary to take drugs from the wards where I worked. However, my job performance suffered in many ways. Eventually I was sent home to finish my military career at a stateside hospital. As I was being processed out of the army, my discharge physical showed a growth in my right lung. I was hospitalized for tests to determine what was wrong with me.

During the night I would put on my uniform and go to the pharmacy to have prescriptions filled that I wrote for myself. Of course this was very much against regulations, and I was eventually caught. The pharmacist, who noticed the irregularity, sent for me. When confronted with the evidence, I confessed everything. I was astonished that he was kind to me. He seemed to be more concerned about my welfare than about my illegal behavior. We talked for quite a long time. Eventually the conversation turned to spiritual matters and church affiliations. I did not want my behavior to reflect unfavorably on the LDS Church, so I did not tell him I had been baptized. I did tell him, however, that I had taken the missionary discussions and felt a closer affinity to the LDS Church than to any other. It was then that he told me he was a bishop in the LDS Church. It was the most amazing single moment in my life. I don’t believe in coincidences of that magnitude. I knew, with certainty, that Heavenly Father had led me to this particular pharmacist. I knew that regardless of the temporal and spiritual laws I had broken, Heavenly Father knew me and still cared about me. It was the moment that began a long and difficult path back to full activity in the Church. I spent many Sundays with this wonderful man and his family. He had several children, a black poodle, and a wonderful wife who welcomed me into their family. They helped me believe that redemption, even for me, was possible through the sacrifice of our Savior, Jesus Christ.

Now, thirty years later, I have a wonderful life. I have been married for twenty-four years to a terrific man. I have a lovely family, including a granddaughter who is heading for college this year and a grandson who brings me great joy during his annual summer visits. The path back was not straight or easy. I have had the help of wonderful bishops and branch presidents along the way. Many visiting teachers have been there to pick me up when I stumbled. Attending the temple is a continuing source of strength and peace. I have been truly blessed by the miracle of this church and the love of my Father in Heaven.

JoAnn Coursey Abegglen

I was actually raised in a military family. My father was in the air force, so my whole life I just kind of traveled around the world and have been a part of that. When I came to BYU, I actually did a first year in dietetics. After that first year I went home for the summer and worked in the local hospital in northern California. They hired me in dietetics so that I could kind of get a feel for that. However, I fell in love with what was going on on the floor. I said to myself, “You know, I’m more interested in the people and not the food they’re eating.” So I came back to BYU the next fall and because the classes were similar, I just switched my major into nursing. In the fall of 1963 it wasn’t difficult to get into nursing. I said, “This is where I want to be.” I was always glad that I made that decision a number of years ago. I love nursing. It’s where my heart is.

I graduated in 1967, and that fall a friend of mine, Leslie Finehauer, and I were accepted into graduate school at the University of Utah. We went to Salt Lake City to graduate school. We were poor graduate students on a stipend, working during the summer as nurses in California. We worked the night shift in an ICU unit. We decided that we’d never work nights again after working that whole summer on the night shift.

We came back in the fall, and there was a fellow who was the officer in charge of the medevac unit at Hill Air Force Base. He was recruiting flight nurses for his Air Force Reserve medevac unit. He wanted to know if we wanted to join. They would provide us with education and send us off to flight school. The money sounded good, and we thought, “Well, we’re adventurous people.” So we signed up for the Air Force Reserves. We were commissioned second lieutenants. That year we did a variety of monthly training. The following summer we were accepted into nurses’ flight school, a six-week course at Brooks Air Force Base in Texas. The med techs were trained separately. Our classmates in graduate school asked if we were going to spend the summer working on our thesis. We said, “No, we are going to flight school.” Once we had been to flight school and were fully qualified as flight nurses, we could be of more service to the unit. We could also be called into work during our two weeks’ active duty as flight nurses on the flight teams that were going in and out of Vietnam at that time. We could fly from Travis Air Force Base in California into the Philippines, or from the Philippines taking groups into Japan, and then from Japan back to the United States. We were really well trained. We had six weeks of gruel. Between classes we had practice flights. We practiced everything and flew regularly.

We saw the first Nightingale. This was the very first plane that was designated for use by the military as a hospital plane. We didn’t get to fly on it, but we got to go through it before it was deployed into service. They were designed late in the war, about 1969. There were supposed to be three or four of these planes. They actually carried only fifteen or twenty patients, but they had critical care units designed into them. They were really luxurious from a patient care standpoint. We flew in the C-141. It was a huge cargo plane that was transformed by putting in seats and beds or stretcher racks. It then became a hospital because of the equipment brought on board. It had everything—equipment, suction, oxygen—built right into the plane. It was used domestically to fly military patients around the United States. It wasn’t really capable of flying overseas. It wasn’t big enough, and it couldn’t be used as a kind of dual system. Usually the crews on the C-141s went over in the plane, reconfigured it, picked up their patients, and flew out as a hospital ship. It was a huge plane, and we just slid seats in and usually designated some areas for stretchers.

Sometimes we took short trips. If I was just flying between the Philippines and Japan, I might make that run a couple of times and then come back and pick up a group of patients. Usually we flew only one-way with patients, such as into the United States to Travis. I came more into Travis because it had a big military hospital and they could stage patients out of there. Usually another crew would pick patients up and distribute them throughout the country. We had limits on our flying time. The crews could fly only so many hours, and then they would have to have some down time.

The flying team consisted of three nurses and three med techs. We had doctors available to answer questions, but I believe it was primarily the nurses and med techs who made the decisions. We could use the radio over the Pacific to call a physician and say, “By the way, this is what I have here.” We always had a motto that nobody died on our flight. That was possible because the nurse who was responsible for selecting the patients that we were flying out was very careful to select people who were pretty stable. Even though we were careful, we could still have ninety patients with a maximum of ten of those patients who were trached on Bird respirators on the plane at a time. We could have only so many psychiatric patients because it was hard to know how they would respond to the plane and close quarters during the flight.

With three nurses and three med techs, we really moved. We had to be very aware of what was happening to our patients. Some patients had abdominal wounds. The wounds were never sutured but were open, because high altitude changed body cavity pressures and would have disrupted sutures. The Heimlich valve on chest tubes was developed during the Vietnam War in order to allow patients with chest tubes to fly without wreaking havoc with chest pressures. You couldn’t have glass bottles or any other kind of bottle attached to the chest tube when you were flying. The Heimlich valve was a one way valve that allowed the air out of the chest with the change of air pressure at high altitude but didn’t allow anything else to get sucked back in. As we flew, any air trapped in a cavity could cause a problem. That’s why we couldn’t have a lot of wounds that were sutured very tight. We packed a lot of neutracaine in the wounds for pain control.

When we checked blood pressures, we had to make sure our stethoscopes were really in our ears because we always had the sound of engines. Listening to breath sounds and making sure that lungs were really expanded or getting vital signs could be a little tricky. Those were the days before we had automatic reading machines and telemetry. We had to be able to hear or palpate it out. We learned these things in flight school. They taught us about the changes that go with altitude changes, the physiological things that take place in patients, and some of the issues that we had to look for and deal with. They taught us how to gather our information. We had a lot of practice listening with stethoscopes because we really didn’t have heart monitors.

We did have the Bird respirators—the green machines—from the 60s. We basically set a peak inspiratory pressure on those, hooked the patient up, and hoped our patient was getting enough oxygen. We could blend it and we could humidify some. That was about it. Nothing like the sophisticated machines we have today. There was no such thing as a respiratory tech. Nurses did all the suctioning and made all the changes in the respirators. There were no blood gases. We had to use our assessment skills to decide if the patient was hypoxic and needed more oxygen. We really had to solve all of our own problems in the air. Many times the key to that was doing good assessment and making good selections on the ground.

Assessments on the ground could take several hours. One or two nurses would go out to do all of the assessments. They looked at the patients who were leaving and then went through and carefully checked the patients, gathered the data, and decided who would go. We did a basic assessment, checked out all the injuries, and classified them. We could say, “We’ve got so many of level-four patient,” or level-three or whatever. These were the walking wounded. We divided them up as to how many we could take. “Okay, this is the group. Here’s our list.” We’d make a list of the patients we would be taking out on our flight, and then the ambulances would collect those patients and bring them out. Then we would load them on and place them where we wanted them. Once we got everybody in place we’d go.

The pilots were great, too. I know that in some of the other crews if they ran into real serious issues they would find a place to land. “We’re close, only an hour out of——.” They may have had to divert to Japan and gone in when somebody really went bad on them and was in big trouble. “We’ll find you calm air,” or “This is what’s coming up, so sit down for a while.” It was like being a stewardess on the plane. We just laughed about that.

Usually, if you were out on the flight, you were busy. There was no “I’m going to sit down and rest for an hour; I have nothing to do.” Between the six of us, we kept moving. We checked everybody, checked vital signs, changed dressings, and reinforced things on a continual basis. We were generally moving the whole flight until we got to point B and signed them off. Then we sat down and rested. Usually the flight nurse—the head nurse—would be the one who was responsible for signing the paper work. If all the patients were going to the same institution, she would check the patients and make the report. We kept brief notes of medications, dressing changes, and IVs. We usually didn’t give blood in flight.

I loved the marines. The marine patients who had minor injuries and were ambulatory were always attentive to their marine buddies who needed help or who could possibly get a little out of hand. They would say, “We’ll help them out,” or “I think that he’s really in a lot of pain, but he’s not saying anything to you.” This would allow one of the med techs to get to them.

We never had anybody die on our flights. I think the toughest flight of all was towards the end of 1970. We were flying a lot of burn patients, taking them to Travis and Brooks, which was a burn center. The burn patients were the hardest. Their burns were caused by napalm. At that time the treatment for burns was to basically just wrap the patient. Our patients were all wrapped up and sedated with morphine in hopes of getting them to the States without too much pain. Some of them were pretty badly burned, some over 50 percent of their body and on respirators. The ones who were super high risk and couldn’t really handle the flight all the way back from the Philippines would be staged out from Vietnam. They’d come to the Philippines and then go to Kara, Japan, and then to Travis, and eventually to Brooks.

The burn patients smelled. They had debrided the burns some, but there was still a lot of debridement to do. I can still remember the smell of burned flesh. Five or six hours in the plane with a group of burn patients was hard. We were glad to get them to Travis and off the plane. We kept them sedated and they all had IVs so they weren’t hurting. We tried to make them as comfortable as possible, but it was hard on a stretcher where they couldn’t turn or move very well.

The med techs were wonderful. I don’t think that any flight nurse would have been successful without them. If you had a good one, you knew the flight would go well. You could assign them and say, “Okay, this is your group.” We usually broke the assignments down among the three nurses to oversee what the enlisted people were doing. If your medic was on top of things, he would come to you and say, “Such and such is going on. Let’s do this and this.” It was a wonderful blessing to have these kind of people working with you. If you were splitting ninety patients up among six people, it was important to have staff who were sharp.

There was a lot of drug use in east Asia, and there were a lot of soldiers who were into drug use. Some of them were on the verge of exploding just because of the psychological effects of the war and the pressures of returning home. I didn’t have that experience, for which I am grateful. I prayed every trip that this hospital ship would get from point A to point B.

I was never in a situation where I was concerned for my life—no bad storms, mechanical problems, or anything of that type. Sometimes we were grounded because of issues on the ground or things that came up about the plane during the flight checks. In all my flying experience we never had problems with the aircraft. An airplane is really a flying box, so there were few amenities. We had oxygen and oxygen masks. It was kind of rough living because we sat strapped into jump seats. There were two restrooms on board for ninety people. The patients who flew on stretchers were all catheterized. It was just the easiest way to transport people. The guys were kind of used to a few bathrooms for lots of people, and the ladies were sort of outnumbered by the multitudes and just had to take our turn.

Our crews were always really nice to us. If we stayed over, they always made sure we had housing and that we could get around. I don’t know if that is typical air force or not, but our flight crews always looked after the flight nurses. The nurses looked after the enlisted, so we really always traveled as a group. I never really had to worry when I was traveling with a crew. Most of them were just great people. They always looked out for the nurses because they really understood what kind of work the crews in the back were doing. I also learned that some days you have to wait a long time for things. Sometimes the weather would ground us, and we’d wait two or three hours before we could fly. If we ran out of flying time, we had to wait overnight. I learned to travel light. The pilots would always say, “Come on with us to the bar and have a beer.” We would always answer, “Well, that is really nice. Could I have a Coke?” You could have all the beer you wanted to drink for free, but a soft drink cost a dollar. The crews who were not Mormon got a charge out of teasing us a lot about our not drinking, but they always looked out for us.

I met my husband while I was in the air force. He was in the air force stationed in California. He was a fighter pilot. He says, “My wife picked me up in Vietnam and she took care of me all the way home. That’s how I met her. She was a flight nurse.” It is a wonderful story, but not likely. He had graduated from college and had to join the service, so he chose the air force. He was full time. He had gone through pilot training down in Texas and then transferred up to Hamilton Air Force Base in northern California. That was where my father had retired from the air force. My husband came to the same ward, and we met there. He was never injured. He actually ended up never going to Vietnam, though he did have orders. After we were married, he had orders, but it was important for the career of someone in the air force to go, so other people would keep stealing his orders. So after we were married we were sent to Canada. That was really funny because people who didn’t want to participate in the war went to Canada. But we were legitimately going to Canada, to Vancouver Island. He was responsible for managing the nuclear weapons on Vancouver Island. That duty station was kind of “the eyes” watching Russia, thinking they might come down through Alaska. It was kind of the northern front. There were four young couples sent from Hamilton Air Force Base to Canada for a year after we were married. My husband had about a year and a half left before he was to get out of the service. After we were married and went to Canada, I didn’t have a unit I could drill with. I went inactive hoping to find a unit to drill with in the future. It was too far to come down to McCord Air Force Base from up in Canada. I remained inactive and got out of the reserves in 1973. But I loved it. I wear wings that I honestly earned myself. I still have my uniforms at home, flight uniforms and regular uniforms. When we flew we wore nice long navy blue slacks, a light blue shirt with an overwaisted shirt, and a tie. We wore black lace-up shoes and our hat. We wore our names and our wings on our shirt. We dressed really quite nicely even though we were flying. We didn’t wear our skirts or formal jackets, and we never wore cammies.

My military experience really did change my life. I found a husband. I had a real appreciation for good assessment skills because so many times we didn’t have equipment. Your own skills and knowledge base got you through. I learned a great deal about teamwork and how to depend on other people. I learned how to divide the work up among people and get that work done. I have a real respect for people who provide medical care in the middle of nowhere to keep the patients stable enough to get back to the next point. The dedication of medical people, flight crews, and all of those folks interested in getting all those wounded people back was incredible. I really appreciated that. The politics of war are completely different. But I’ll always remember people taking care of the patients and just getting the job done. Nursing care in the air was a little scary at times, but we also gained a sense of confidence that we could do it. We improvised so many things and solved little problems. We could sit and help people through things. We talked to soldiers so they weren’t terrified of flying. If their eyes were covered, their sensory perception would be off. Noises would frighten or startle them. We appreciated each day as it came because we didn’t know if it would be our last. We learned to be thankful for everything that we had. If we got another day, that was a gift. I learned to deal with one day at a time and when that was over I would think, “Oh, that’s great. I’ll go on with the next day.” I still do that. When things are stressful and there is a lot going on, I can go back to my military experience and say, “No, this is today. What needs to be done today? Okay, we have to get through this today.” I even try to use that with my students at times. In the newborn ICU when things are real busy, I say, “Let’s get through this one piece at a time. We’ll deal with this issue now and then we’ll move on to the next issue.” I have always appreciated learning that. If I need to focus for the instant, I can focus and get it done, and then I can move on. I think that is one of the things I learned while I was flying for that short time—to be thankful for the moment.

I think I have a strong testimony, but the war situation certainly puts your faith into practice. I learned a new courage. Sometimes we were out with crews that were not Latter-day Saints, and they would make fun of us. When I was a twenty-two-year-old or twenty-three-year-old woman, it was hard—especially at a time in history when it was not a woman’s world. I had to remember who I was and what my values were. I really appreciated having the opportunity to determine my values when those around me had very different ones. I gained a greater understanding of faith. We sometimes flew with some unstable patients, and we had faith to know that we would be sensitive enough to pick up early on what was going on and be able to intervene in a situation. I was always grateful when I got to our destination and got off the plane in one piece. I think that spiritually I was strengthened by patients who just had courage and hope. What were these young people who were missing an arm or a leg and returning to a sometimes unfriendly environment going to do with the rest of their lives? They had girlfriends and wives who they worried might not accept them. They thought that if I would sit and talk with them, maybe their wives and girlfriends would talk to them. We would talk with some of those patients who were actually terrified to get back home for fear that their families would reject them because of the seriousness of their wounds. They were great people. I thought that under those circumstances, you have to have the courage to really go on. The battle was not easy once they got home. They had surgeries and all kinds of things ahead of them. I learned a lot from other people that strengthened my spiritual side.

I had some really great patients who appreciated the little things that we did. We would bring them water or juice, or look at them and say, “You know, you look like you really are in pain. Can I get you something?” At the end of the flight I was always grateful to those people who got off and said, “Thank you for helping us this far.” They were so appreciative, even though they were the ones who were in such misery. Air force nursing was always rewarding. We may have been tired but generally left a flight feeling like we had done a good job. We got everybody to the destination so we could go home and sleep.

Now I am a professor at the Brigham Young University College of Nursing. What I’ve learned with my own students is to have patience and to believe that we can work through problems. I have learned to spend time listening to people tell their stories. I tell students that they need to get the data

correct and look at the history. I explain to them that it is really hard to plan interventions or care if you don’t know what is happening to the person. Those are probably the main things that I have brought over into teaching.

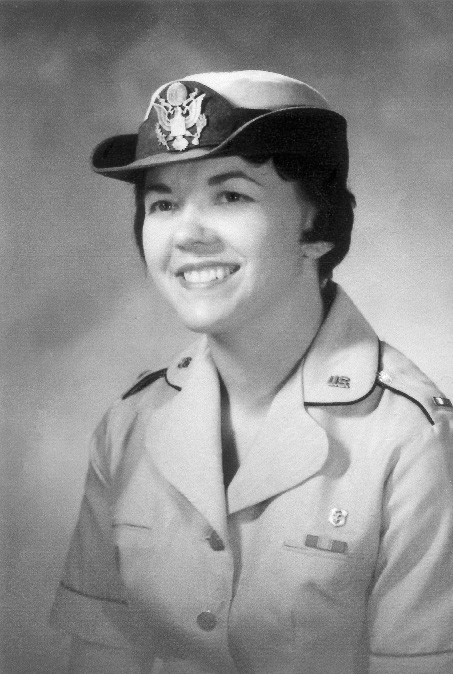

Phyllis C. Doxford

Phyllis C. Doxford

My mother had been sickly throughout her life, and I had seen her many times in the hospital and watched people care for her. My grandmother had had some hemorrhages of the stomach as I was growing up, so I watched that. I kept thinking, “You know, if I was a nurse I could take care of them.” When I was younger, the books I read always dealt with either nursing or airline stewardesses, and I had a librarian that told me one day, “You know, you’re going to go into one of those two fields.” At that time a stewardess had to have a nursing background anyway. That was the criteria for being a stewardess. When you flew, you had to be able to take care of any emergency that happened in the air. That got me started, and then afterward, when my family had their illnesses, I decided that I wanted to do nursing.

I chose to go to a hospital school of nursing and not a university program because it was closer to home and didn’t take as long. The university was four years; the hospital school was three. I would be able to do more hands-on nursing in the hospital school. I chose Saint Mark’s School of Nursing. And at that time I could live at home for the first two years. The last year I had to live down at Saint Mark’s on Third West between Seventh and Eighth North. Today it’s on Thirty-ninth South between Tenth and Thirteenth East. The hospital was funded and run by the Episcopalian Church. We had to attend church services on a regular basis. We had our capping ceremony at the Episcopal Cathedral. Nurses don’t even wear caps now. I don’t know how many times over the years I hit my nursing cap and my hairdo would be askew, particularly when I was bending over to care for the patients in traction. The cap could be a pain at times.

When I first started out at Saint Mark’s Hospital as a student nurse, we had glass syringes. We would rotate into the central supply, and we had to check the needles for barbs and the gloves for pinholes. We had big jugs of distilled water and a gas stove, and we would boil all of our syringes and everything on the stove. Our morphine came in a tiny, narrow tube that was about a quarter of an inch in diameter with a corked top. We would pop the cork and drop the little morphine tablet into the syringe, draw up the sterile water, shake it to dissolve it, and then give the injection. We didn’t have prepared medications for a long, long time. For all my student days, and for the first two years I started working as a registered nurse at Saint Mark’s hospital, we prepared our own medication. Gradually more packaged supplies were used. Then they stopped having student nurses check the gloves for holes because they had disposable ones.

After graduation in 1962, I worked in Salt Lake City at St. Mark’s Hospital for four and a half years. At first I worked pediatrics. I took the older kids. I figured that if I took the older kids, they could tell me what was wrong. I was a beginning nurse then, and I had a lot of fears too.

I took care of a lot of cancer patients. I would see them for the initial therapy and then I would see them back for the chemotherapy. The only chemotherapy drug that we had in those days was 5-FU. Then I would see them for the radiation. They got to be my family. It was a terrible responsibility for a young graduate. They would beg me not to go on my days off. They’d say, “Nobody can take care of patients like you can,” and “You can’t go. You have to stay here and take care of us.” That haunted me when I went home. And I would worry about them and wonder, “Is that person after me going to do their job as good as I was doing it?” I would take these patients through their final stages. The night nurse and I knew when our patients were going to die. I would work seven days and then have two days off, then work another seven and have four off. It was a long schedule. I would say to her if I was approaching my four days off, “Now don’t worry about Mr. or Mrs. so and so. She or he is going to wait for me, and I’ll be there with them when they go.” That worked for me, and it worked for the night nurse because she’d tell me the same. She was LDS, as I was. I think the Lord knew that those people dying needed somebody that they knew. That’s the way it went for three and a half years and I got really burned out. At that time nobody knew what depression was and I just kept getting more and more depressed over the patients who were dying. I had a rose gallery of the dead, and if I was really tired, I’d see them all night long. I got to the point where I couldn’t stand that. I didn’t want to go anywhere. I just wanted to go home and stay there. I didn’t want to go out with my friends. I didn’t want to do anything. My mother said I was sitting in a rocker one day and she said, “What’s the matter with you? You’re so quiet these past days.” I said, “I was just sitting here thinking that the good Lord could take me anytime. I’m ready to go.” And she said, “What do you mean you’re ready to go?” I can still hear her. “You’re in your twenties. How can you be ready to go?” I said, “I am. I’m ready to go. He can take me with whatever disease He wants. I’m ready to go.” My mother sat down with me, and she said, “You know, you have got to get out of that ward. You’ve got to do something different. I don’t care what you do, but you’ve got to get away from those patients.” And I said, “They’re the only patients that I know, and I would come in contact with that if I worked any other floor in nursing.” She said, “Well maybe you need to do something different. Maybe you need to go back to pediatrics.” I said, “No, pediatrics is not my interest. I don’t want to do that.”

About that time I was receiving information from the air force. The Vietnam War was going on, and the military needed nurses. The air force was requesting nurses, and they asked if I would like to be a part of that. I quietly thought about it and the more I thought about it, the more I thought that it would be a nice place for me to go. I talked with Mom about it. My mother said, “I think that’s a very good idea.” And so I went, without telling my father, and took the oath of office to be a nurse in the air force.

My father and I had talked about the military. He was a sergeant in the army, and he would never take a higher rank. He said, “No, I’ve had enough of the service. I don’t want to have anymore.” So, anyway, he was very set on things concerning the service. I knew his thoughts on the service. He had once said to me, “Well, Phyllis, you’d never make it in the service because you have too much of a temper. You can’t have a temper and go in the service.” When my father heard I had joined the air force, he blew his cool. Later he calmed down.

It was a toss-up between the air force and the navy. I liked both of them. But I kept thinking, “I have claustrophobia.” In the navy, if you ever had to get off of the hospital ship, your best chances probably would be in a submarine. I kept thinking, “They’d never get me in a submarine. I’d never be able to do nursing in a submarine because I’d be too claustrophobic. They’d have to sedate me as one of the patients.” I decided that I would go into the air force, so that’s what I did. I was sent to Mountain Home Air Force Base in Mountain Home, Idaho. My dad finally calmed down. He finally accepted the fact that I was in the service. When we went through basic training in Texas, they had a big celebration for us when graduation came.

Mountain Home was out in the desert. There wasn’t a lot to do. The town of Mountain Home had two sidewalks and that was it. It wasn’t very big. We were ten miles outside of town, and we had desert all around us. It was a Strategic Air Command (SAC) base. Later it was changed to a tactical command.

I worked four and a half months there, and then they told me that I had orders for the Philippines. I said, “How can I have orders for the Philippines when I haven’t been here long enough?” Usually you have to be in active duty for at least two years before you get any change of destination. There was a Filipino nurse at Mountain Home who had orders for England. She came to me one day and said, “Phyllis, I’d like to go home. Would you trade with me and go to England, and I’ll go to the Pacific area because that’s my home.” I said, “Oh sure, I’ll do my mother’s genealogy there.” We were English, Irish, Welsh, and Scottish, and I thought, “No problem, I’ll go there.” The Air Force said, “Absolutely not.” So she went to the cold water fleet in England and I went to the PAC (Pacific Air Command) area, which is where I served the remainder of my time.

I was put on a surgical floor that took all the head injury cases. They would air-evac them out of Nam. They would do enough surgery on the injured in Vietnam to stabilize them and then ship them to us or to Japan. We were the two areas that took care of them if they had to do further reconstructive surgery. If they were not able to go back into active duty after that, they would be sent home. Otherwise they would go back to active duty. That was a sad thing.

I had patients that had leg wounds or arm wounds or different things like that. We would get them sutured and care for them until their sutures were out. As soon as they were able to use their arm or leg, they were sent back into the war zone. I don’t know how many patients I had that begged me to intercede for them so that they didn’t have to go back. I had to tell them that I didn’t have any pull and that there was nothing that I could do. Even the doctors were under orders to send them back if they were capable of fighting another day. That was a sad time for me. I didn’t ever see any come back; I’d see them once and that was it. That’s not to say that they didn’t come back to the hospital.

There was a ward opposite ours on the same floor that was a mirror image of ours. Everything was the same, except they took all the spinal injury cases and we took all of the burn patients. It didn’t matter who was admitting that day, we took the head injury cases, and they took the spinal injury cases. The rest of the patients were alternated, depending on whose day it was for admissions.

Since the Koreans were our allies in the war, we also took care of them. We had flip charts to help us speak Korean, and we would speak to them in one syllable or in pantomime. If we wanted them to scrub a certain area, we would pantomime to them to do that. I think that they were probably like our men. If they got well, they were probably sent back out into the war zone. I remember that they were fun-loving. One day we’d had two of them come off the plane. They had head injuries, and one had a plate put in his head. The old hospital beds were really high, and you couldn’t raise or lower them. One patient was hopping from his bed to his friend’s bed next door, and there was a four-foot space between them. He gave me heart failure. They were having the time of their life, and two other patients were egging them on. I thought, “If you miss that spot and go down and hit your head, then where would we be?” I really chewed them out with facial expressions and hand signals. They were put out, and they sat there, dumpy-like, looking like they were thinking, “Well, I know I’m in the wrong.”

When I began nursing and when I got to the Philippines, they were still using silver nitrate on burn patients. It was messy. We would soak the bandages in it and then wrap the burns. I was taking care of three or four patients. I had a corpsman working with me, and he wasn’t paying any attention. It was really hard at that time to get American clothes in my size, and I am five feet five and a half inches. I weighed 165 pounds at that time. I didn’t fit into a size 4 shoe, and I didn’t fit into a size 28 slip. There I was, dipping and rolling those bandages, and this corpsman wasn’t watching what he was doing. He tipped the basin, and the silver nitrate poured right down the side of me. When light hits silver nitrate, it turns black. My shoes, my hose, my uniform, and my unmentionables all turned black. It doesn’t come out. I was so mad at him.

Then a short while after that happened, we started using the Silvadene cream. It was all right except that you had to wipe it all off of the burns, and you had to put it on twice a day. Wiping it off was painful. If they had a third-degree burn, they wouldn’t feel it, but if they had a second- or a first-degree burn, it was painful to have you wipe that off. They would beg us not to, and it made us feel terrible. By the time I finished my tour, we didn’t have to wipe it off. We still had to put it on twice a day, but it was a lot easier on the burn patients.

They usually moved nurses around, but I stayed in surgery that entire time. Taking care of these soldiers wasn’t quite as bad as taking care of the cancer patients. We would keep them long enough to get them stable so that they could either go back home or back to the war zone. I didn’t become as attached to them as I had to the cancer patients. Yet we had good times with those patients too. I remember playing games, like checkers, that didn’t take an awful long time. Those boys really needed that too. There were times when we didn’t have as many casualties, and we had a little bit more time to do that.

While I was in the Philippines, we had some earthquakes. That was something. I had corpsman who had never been around earthquakes. They had been in tornadoes and hurricanes, but they had never been in earthquakes. We had been having small earthquakes all along. I kept telling the people who worked with me, “We’re having small earthquakes.” “Oh, no, no, no—it’s the aircraft going over.” They just kept pooh-poohing it. But one day I was suctioning a patient, and I was having a hard time getting the suction catheter out. I couldn’t figure out why. I looked up and saw that the IV bottle was swinging. I knew then that we were probably having an earthquake. I let my hand drop, and the catheter came out.

The earthquakes went on and off for about a month. One night I was working the midnight shift, and there was one that measured seven on the Richter scale. It hit more in Manila than where we were. My corpsmen had never been in an earthquake, and they didn’t know what to do. They were standing out in the corridor, and their eyes were as big as saucers. I said, “You have got to get yourselves into the doorway. Stand in the doorway. That’s where you’re going to be safe.” So that’s what they did. Then I remembered that we had a patient in a circle electric bed in the room opposite of me. The top piece wasn’t even tucked into its cradle; it was just up against the wall. I realized it was going to start flying and hurt the men. I thought that if I could get in there and stand in the center of the room, I could deflect whatever was going to fly around. I was trying to inch myself in there. It wasn’t working very well because the earth was rolling. I only inched my way part way into the room. But I know that the Lord blessed us. The beds rattled and shook but none of those pieces flew anywhere. The patients’ beds in the other rooms would move forward and backward, almost touching each other, and then roll back. The circle electric beds never moved.

At the time we had glass IV bottles, and we stored them on high metal racks. We had to use a stool to put the bottles on the top shelf. We would send a corpsman down with a grocery cart, to get his supplies. The quake knocked some of the bottles down into the grocery cart, but not one broke. It rolled other bottles to the edge, but didn’t knock them off. We had a big cylinder oxygen tank in the storage room with a file cabinet. It picked up the oxygen tank, tipped over the cabinet, and laid the oxygen tank over the cabinet instead of turning it into a missile or causing it to explode.

The quake made cracks along the baseboard. The corpsmen who ran out onto the lawn said the top half of the hospital was going in the opposite direction from the bottom. It looked like a zigzag. We had a one-thousand-pound air-conditioning unit right above us. I kept waiting for all this equipment to come crashing down and kill us all, but it never did.

We had a nurse from Hawaii who disappeared during the earthquake. Later, after I checked everyone out and made sure they were okay, I said to several of the corpsmen, “Where is so-and-so?” “Well, I don’t know.” She had folded herself up into a corner under the nurse’s station. She was so small and was so flat in there, we didn’t even see her as we walked around. She came out after a while. She probably did it out of fear and figured that it was the safest place.

The telephone was something else, too. The telephone was set up through the radio operators. If we put in a long distance call to the States, we would get a United States operator. We would be talking along and then we would say “over,” and then our parents, or whoever we were calling, would come on. They’d talk, and then they’d say “over.” The operator would say, “Now, you realize that you are going through the radio operators, and you have to say ‘over’ so we make sure that we cut it to the other person.” They would rotate it back and forth, so you never knew who else was listening on the telephone. That’s what we went through when I first got to the Philippines. Gradually I just put through my own calls. My friend was a captain. She would pay a lot of her own money for some of the men to make telephone calls to their people, especially those that she knew were never going to get home. I really admired her for that. If there is a place for another angel she would be there.

The Vietnam War was an undeclared war. That is my biggest complaint against the government. Those men fought and bled and died there, and they were never recognized. The First World War and the Second World War were different from the Vietnam War. The Vietnamese had women and children that fought right along with the men. They had children who carried bombs and blew people up. They had young girls that claimed to need assistance. The soldiers would go to help them, and they would be blown up. Our men had to worry about pongee sticks, which were six-inch-long bamboo spikes that were guide-wired up into the trees. When the soldiers stepped on the wire, the pongee stick would come down and spear them. The Vietnamese would put feces on the pongee sticks, and our men would immediately get a serious infection. It was hot and humid, and bacteria would grow very quickly. Some of these men, especially the ones that got liver wounds from the pongee sticks, never really got better. There were many of them who died. They would get better, and then they would get worse, and then finally they would die. I didn’t work with those patients that had liver wounds, but my friend did. She would tell me about the boys. Most of the time they didn’t make it.

It was sad for the men who were in battle. I knew some of the men from our unit at Mountain Home. Two were killed in a battle at an apartment complex. War is a terrible thing. When you join, you have to go where they send you. We were involved in the Tet Offensive. We worked twelve-hour shifts for several months at a time. We would have a full complement of patients, and we knew we were going to get more from the air-evac system. We went in at midnight and started to triage patients to make room for the ones who were coming. We put them onto stretchers and laid them all out in the aisle on the first floor. We put flight tags on them with information about their injuries. As soon as possible, they were moved out to the United States or back to duty, if they were able to go back to duty. I can remember having to pass medications, and my patients were scattered all over the place. I had to go down with a flashlight to administer medications at two and five in the morning. I would be looking at flight tags, praying that it was the right patient with the right name. Doctors had scrawled names and moved patients in such a hurry that I was afraid I would make a mistake. We no sooner got those patients out than we got the beds scrubbed for the incoming patients.

If patients were well enough they would do their own beds, but we didn’t have janitors. We worked right alongside the corpsmen. I learned that patients who were active got healthier a lot faster. I think that is why health-care providers decided to get patients up and walking the day after their surgery. I know that came from the service. We didn’t have patients with deep vein thrombosis. They didn’t have pneumonia. They were up and walking the floors. It was the same when I got home and went back to work at the VA Hospital. They would say, “I’m too sick,” and I would say, “I’m sorry, but this is going to help you get well.”

I think that my military experience made me more aware of how precious life is. It could be snuffed out at any moment. We treated what we had more lovingly. You figured the good Lord blessed this land. He put all the beauty in it and He put us here, and now it is up to us to take care of it. I never got over the fact of seeing Him. I see the Lord in so much. I see His handiwork in so much around me. I used to come out of the hospital in the Philippines when we had worked so hard and kept the patients alive through our shift, and I would pray that the good Lord would bless and guide them and that they would be able to make it back home, that they would live long enough to get home. I think when you are in situations like that, you see His hand in so many, many things. I saw His hand in saving patients that I didn’t think were going to be saved.

There was a small Latter-day Saint group on base in the Philippines. I had been inactive at home before joining the air force. It had been hard to stay active because I worked shifts and weekends as a student and as a registered nurse. I couldn’t get off to go to church. You don’t say to sick patients, “I’m sorry, I’ve got to go to church.” If you did that you wouldn’t have a job. Besides, my conscience wouldn’t have let me do that. I just got away from church. When I went in the military, I didn’t attend either. I did attend the group on base a couple of times. They just had the sacrament. I still believed in the Lord and I still followed His teachings. I knew the Lord existed and heard my prayers; otherwise, a lot of people could have been hurt or killed during that earthquake. I knew the Lord guided and directed me. I think my military experience strengthened my testimony and helped me return to activity.

One reason I became inactive was that when I cared for the cancer patients, I saw a child with cancer come into the hospital. I used to pray that the Lord would take me instead of the child, but the Lord wasn’t ready for me and He would take the child instead. Consequently, I was upset with the Lord and wanted to have no part of Him. But, you know, the Lord lets you have a lot of running room, and then He starts reeling you back in. I began to realize that I wasn’t seeing the whole pie. When I finally started reasoning that way, when I came to that realization, I began to understand that the child didn’t need all the time I did. He didn’t need to spend all the time in the school of hard knocks that I did. All the child needed was that many years, and then he could return to Father in Heaven, where he didn’t have to worry about all the stuff I had to worry about. So I came back to the Lord and realized I just didn’t know all those things. It wasn’t luck that brought me back. It was because the good Lord put me in a place to help me realize I needed to come back. I think all of my experiences have brought me to the Lord and kept me there. You see all kinds of things in nursing—good things, sad things, terrible things. However, you realize that it is part of life, and you grow by those things that make you the strongest and make you better able to know the Lord. The Lord didn’t promise us a rose garden without thorns. I have had experiences where I know that He is real, that He is alive.

Jay Nielsen

When I graduated from high school in 1969, I decided I would volunteer for Vietnam. Two days after graduation, I volunteered for the army. I actually counted as being drafted, so, in October I was drafted into the army for two years. On October 8 the group I was drafted with met up in Salt Lake City and found out they would be sending us to Fort Lewis, Washington. I spent two months at Fort Lewis in basic training as a private E1. When you graduate from basic training, you go to specialist training. Out of seventy-five soldiers, two of us were picked to go to medic training.

In early December, I went to Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio where I spent three months being trained as a medic. When I finished my training, I was assigned to the hospital in Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri. Orders came down sending half of my training group to Vietnam. The post commander rejected the orders because we didn’t have enough people working in the hospital as it was. We were getting Vietnam casualties and taking care of the veterans in Missouri. When they sent the second order, everyone that wasn’t on the first order was on the second order to Vietnam. After joking and laughing and making fun of my friend who was on the first order, I was on the second order. The first order got to stay home, and everyone on the second order was going to Vietnam. They promised me that I would be assigned to the hospital in DaNang and that we didn’t have to worry.

I came home for a month and on January 4, 1971, I left to go to Oakland, California. From Oakland, I was shipped to Vietnam. After arriving in Vietnam, I was assigned not to a hospital but to the First Cavalry Division, the First and Twelfth Division Infantry. I would be going into the jungle and riding in helicopters and shooting at people. I ended up just going around in helicopters and being dropped off in the jungle.

We received our first assignment on February 15. Six helicopters placed twenty-seven men ten to twelve miles deep into the jungle. They told us they would be back to pick us up in about twenty days. The stated mission was to find the enemy and kill them. On the way to the destination, the helicopter was shot at by an AK-47. It made an odd sound. I asked what it was and was told it was an AK-47. That was what the bad guys shot. We hiked around in the jungle and looked for the bad guys. It was in the Tainen Province in the highlands of Vietnam. It is very dense, beautiful jungle. We burnt down a village. I thought that was kind of a waste of a beautiful village.

We had a couple of incidents of shooting people, nothing major, but the experience, as far as being a Latter-day Saint in Vietnam, struck home. On March 3, we started hiking along this trail. It was late in the morning and we came to a fork in the trail that was fairly heavily used. As the medic, I would always walk about fifth in line, after the point man, the lieutenant, the man with machine gun, and the man with the radio. I always wanted to be close to the men so that if someone was shot, I could see what was happening. Suddenly there was all this screaming and gunshots. The sound of screaming and M-16s just exploded. I never heard such noise and hollering in my life.