The Tragedy of September 11

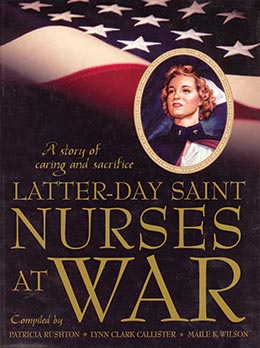

Patricia Rushton, Lynn Clark Callister, Maile K. Wilson, comps., Latter-day Saint Nurses at War: A Story of Caring and Sacrifice (Provo, Utah: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2005) 271–278.

Historical Background

On September 11, 2001, two American Airlines jumbo jets, hijacked by terrorists, flew into the twin towers of the World Trade Center in New York City. A third airliner crashed into the Pentagon, and a fourth, forced to the ground by its passengers, crashed in a field near Shanksville, Pennsylvania, before it reached a possible fourth target. Within a week of the event that took the lives of nearly three thousand people, President George W. Bush, son of former president George Bush—who had declared war on Iraq—declared war on terrorism throughout the world.

A. Elaine Bond

On the morning of September 11, 2001, I was frantically getting ready to go to Amman, Jordan, to be co-chair of an international nursing conference. I had at least four days’ worth of material to compile for the conference, and I only had two days to do it and be on the plane. I went out for a run. All was well in the world because I almost thought I could pull off the preparation for the conference. When I walked in the house, my husband had the television on and said, “There are two planes that have just gone into the World Trade Center.” Before we saw what happened to the Pentagon, I knew that our lives would never be the same. The ramifications of 9/

Dulles is one of the airports from which the terrorists launched their attacks. The scary thing about going was questioning all of the security and what might happen next. I was at the Salt Lake Airport three hours before departure time. Passengers were already lined up outside the door of the terminal and clear down the entire length of the sidewalk, because the airport was using very few check-in points, and everyone who was flying Delta had to go at once. All flights were mixed together. There were zillions of people, but everyone was patient and considerate of others. Those of us who were standing in line recognized that we were going through increased security and that it had to be that way. We moved fairly quickly. It only took about an hour and a half to get through the line up to the ticket area. Then we had to go through a couple more security points. They had to open everything and look at everything. We had to show personal identification and a ticket everywhere to be able to get in. There were absolutely no problems. Everyone worked together very well.

When I got to Dulles, I expected to have difficulty in that there would be even more security. But they weren’t as concerned about those getting off the planes as those getting on. I got a rental car without incident. When I got to Red Cross Headquarters, I found I was one of the very first people to arrive from outside the area. The local Red Cross chapters had handled things up to that point and done an excellent job, but they were absolutely overwhelmed.

I had five hundred pairs of boots from the Salt Lake Red Cross chapter for the rescue dogs in New York City. Their feet were being badly torn up and burned, and there was even a dog that died from heat exhaustion. When I got to DC, the Red Cross arranged to transport the boots with someone who was going to New York. The boots made a big difference for the dogs that were there. I don’t know who donated them, but it was someone in the Salt Lake area.

There was a lot of work for us to do in Washington DC. The first day I went to the Pentagon. At that time there wasn’t as much security. We helped with small wound dressings and mostly mental health support for the relief workers there—the firemen, the military, anybody who was there helping out. I only spent that one day actually at the site. There wasn’t that much that needed to be done there. There were other people who could fill those roles as well as I could, and I was needed other places.

The next day I spent checking health records of the volunteers who were arriving. There were two hundred fifty of them who showed up that day. Out of that bunch, I had to send two people home. Some of them were just overzealous and were not quite ready to return to Red Cross service after having surgery or some other kind of condition. They were not very happy about that, but you just can’t be at a disaster and not be in the best of health.

As far as our individual positions, I don’t think we ever felt threatened. I think we felt like we were safe enough doing what we were doing. It was traumatic and emotionally taxing to work with the people who were there. We worked with rescuers. We worked with firemen. We worked with all of the branches of the military, Secret Service, CIA, FBI, the local fire department, and all of the volunteers, and everyone worked together really well. Even though they were the big tough guys on the front lines, the Red Cross could help in ways they could not. As one fireman put it, “I hadn’t been there very many minutes when I knew I couldn’t make this all better. The Red Cross is the one who really makes it all better.” As they came out, absolutely exhausted, they didn’t really want to talk about some of the things they were seeing. It is just that they needed to, and as they would sit down and start to talk, it was like opening a floodgate. They would give us a lot of information. This was especially true of military people because even though there were mental health workers there for the military, the rescuers didn’t want to talk to their official people, because it would go on their record. They were happy to talk to the Red Cross people because then they could unload the things that were bothering them. Many times all it took was someone to talk to.

After those two days I developed several Integrated Care Teams. Some of the teams worked with patients who had been treated and released from local hospitals. The people I spent the most time with were those who were hospitalized or discharged, along with their families. There were other groups, whom we all joined at the end, who worked with the families. We also worked with the families of the deceased: American Airlines passengers’ families as well as family members of all those at the Pentagon who were killed.

There were one hundred eighty-five people who were killed in Washington DC, some of those from the airlines, the majority from the Pentagon. A lot of community nursing techniques were needed for working with the hospitalized people and those who were discharged. I learned that you always look in the least obvious places. The two hospitals that I originally had under my direction were Arlington Hospital and Walter Reed Hospital. When we arrived at Arlington to visit the two patients who we knew were still in the hospital, we discovered that there were more than twenty-two patients who we did not have on our records. That is where those detective pieces helped us to get information. There was a military liaison person there. When we told him the two people we were to visit, he took us to them. One was about to be released, and she said she had lots of help from neighbors and friends and family who would take care of her. The other person was badly burned, though the hospital did not think she needed to be in a burn center. While we were waiting for her to get out of dressing changes to her burns, we met with the admitting office and the emergency department. They willingly shared all the names, addresses, and telephone numbers of all those who were not on our list. So it was a wonderful communication-negotiation-networking kind of thing.

When we visited with the second woman who had the burns, she was so distressed. She had not come to terms with it. By now, it had been approximately five days since the disaster. The realization of what had really happened was sinking in. She was a civilian Department of Defense worker. She was extremely traumatized by the things that she had seen. The person who was sitting at the desk next to her went for coffee and never came back. They were good associates and had worked together for a long time. She realized that she had survived and her associate had not. We discovered those feelings of guilt were common among survivors. We found that over and over because they would say, “Why would someone die and another wouldn’t?” As we talked with her, she expressed that the most important thing to her would be to see her family. Her family was from Louisiana. We were able to make arrangements for them to fly up. Her father had never been in an airplane. It took some work to be able to make the arrangements, but she was so ecstatic to have her family come. She wanted to have all of her nieces and nephews and brothers and sisters come, which was a little bit out of our range. They couldn’t come anyhow. It made it so we didn’t have to resolve the issue. She and her husband were extremely grateful for the care they received. Every time we interacted with them, we watched them come from a terrible shell-shocked position, where they were just scared to having happy eyes and being happy to see us. They lived in DC because of her work, and he worked somewhere in the city as well. They were an example of everybody who we worked with. It was extremely worthwhile even though we were thoroughly exhausted.

Each night when we went home, we would be totally ready for bed. I would call my husband, talk to him for a few minutes, and sit there to watch the news. I would wake up about two or three in the morning. The TV was still on and I had been sound asleep. I would turn off the TV and sleep a couple of hours before I was ready to go again. One of the things that helped with my mental health while I was there was that I continued my practice of running every morning. We were in Virginia in Falls Church, and they had wonderful running paths there. I was able to go running every morning before it was time to go down to headquarters to begin our day’s work.

After I had done the majority of the work at Arlington and was able to get into Walter Reed, we began to work with some terribly devastated people. Getting into Walter Reed was a choice experience because it was a military hospital and there was always the regular security. But because of the disaster, there was even more. We had to have our FBI identification. We had that to be able to get into the Pentagon and it was the identification we used everywhere else as well. We could go anywhere. They just had to check us along with anyone else who happened to be there and see that we had the proper credentials. I went through checkpoint after checkpoint after checkpoint just to get into Walter Reed. One of the people we saw at Walter Reed had saved several other people in her area. She had tremendous burns as well, but not bad enough to be in a burn unit. She is an example of what we see anytime there is a disaster. Nobody gets up in the morning and says “I think I’m going to have a disaster” or “I think I’m going to start a war.” We think we are going to carry out our everyday activities, and we often have a dozen items on our calendars that we haven’t finished yet or that need to be worked on or that need to be resolved. If we have dysfunctional family relationships, they hang over whatever else we are doing. And this particular patient was dealing with several of these issues. She was recently divorced, and all of the details of that were not yet worked out. Her mother had some mental health problems and lived in South Carolina. Working out the arrangements with the mom was taxing, to say the least, but we did help her. The mother came on a couple of occasions. The client did not want her mom there when she went home from the hospital, and it didn’t take us long to understand why. It took a lot of PR skills to be able to deal with people. We had their fears from the disaster and all of the other odds and ends and quirks that all of us have.

Another person at Walter Reed was in the process of moving. She had only been on the job for two days. Her family was still in upstate New York. She was staying with her father in DC, trying to care for her husband, who was going back and forth; her children; and her mother, who was also going back and forth taking care of the children and the patient’s needs. It was quite a challenge to help arrange the moving and to make sure everything was coordinated on both ends. In the meantime, her mother had a heart attack while she was in New York. There was no one to take care of the children. We were finally able to work it out.

People from the Red Cross came and went, and as some people on our team left, we integrated two of our care teams. I took on the responsibility for the worst patients that were at Washington General, where the burn unit was. Once again, it was terribly devastating to watch the effects of the disaster on families. We didn’t have much association with these patients. The majority of them were still in critical care in the burn unit. There were some who were out of the burn unit, and we were able to talk to those individuals. For the most part, we worked with their families. Those families with education, access to resources, and knowledge about how to access the system did fairly well. Those families who did not know how to access the system, those who had struggled their entire lives, and those who did not have a good education were absolutely devastated. I would go home and want to adopt them and help them to have some positive experiences in their lives. One husband was absolutely overwhelmed by his experience. His wife was severely burned. I am not sure that she survived. I talked to the charge nurse in the burn ICU. It was obvious to her and me that we were talking multisystem failure. Each day the patient would have surgery to remove necrotic tissue, and each day there would be less of her. The poor husband was just beside himself. Very poor, very nice people, but so deprived when it comes to the things of this life. Those experiences wore on us, dealing with them all the time. It was really hard for us, but not nearly as hard as it was for them.

The one who got to my heart the most was a developmentally delayed gentleman. I think he was forty-three. I doubt that he worked at all before he started working at the Pentagon as a janitor. The mental health person on our team was wonderful with him. At first we were not able to find him. That happened often. Names didn’t match the telephone numbers or the addresses. Sometimes there was a telephone number or address at the Pentagon, and obviously we couldn’t access that. But in his case we just couldn’t track him down, and it was his mother who called us. He lived at home with his mother in a modest subsidized apartment. He was not sleeping at night and he would hold his head and shake it and say, “Make it go away. Make it go away.” His mother told us that he didn’t talk very much, and for him to say even that much was something he didn’t normally do. When we arrived, he was so agitated; he just couldn’t sit still. He had been in the hospital but had been released. The reason they had taken him to the hospital was that he had been seizing when they found him on the floor in one of the halls at the Pentagon. They assumed that he had a seizure disorder. He went to Arlington and then went to Walter Reed and was released from there. He was at home when we found him. His mother told us that he had never had a seizure disorder and had never taken any medication. He had been in two healthcare systems, and they had never picked up on that. They didn’t believe it. When we have these underprivileged people who won’t speak up for themselves, they are just so accepting. It was one of those times when I just wanted to tear out my hair at the failings of our society. Even as enlightened as we think we are, we are missing the needs of so many people. He just sat there so agitated and rocked back and forth in his chair. He was jumping from side to side and our healthcare worker said to him, “You don’t have to talk to us about this. You don’t have to tell us anything you don’t want to tell us. We’ll find somebody who you can talk to, and they will come and see you lots of times, and you don’t have to tell them anything until you are very comfortable with them.” That comforted him a little bit, and he calmed down. I think he was probably worse because he thought somehow we were associated with what he had gone through. He functioned on such a low level that he was not able to verbalize a lot of things. He said, “No, no, don’t talk about it, no, no, not talk about it, not remember. Never going back there, bad place, never going back.” When we went that first time, we took him a card from a school child. School children all over the United States made get-well cards and sympathy cards, and we delivered them by the thousands to patients and clients. When we gave him the card, he looked at it from beginning to end, over and over and over. He clutched it tightly in both hands and just looked at it and continued to rock as we talked to his mother.

One of the things the Red Cross does is provide financial help, but the mother said, “We don’t need it. We want someone to get it who needs it more than we do.” There I was, sitting there dying! Their apartment was maybe seven hundred to nine hundred square feet total. They lived on her social security and his minimum wage check. They lived from day to day, but she didn’t want any financial help from us. There were people who needed it more. The Red Cross was handing out thousands to people who could go out and get another job, who could take care of themselves in short order. Here was this woman who needed it more than anyone I had talked to except the one lady we discussed who was at the hospital. This woman just continued to say “We are blessed.” I thought, “How blessed you really are because you’ve got that sense of self-worth and the attitude that ‘We’ll take care of ourselves.’” Eventually we found a way to get her some money, but it took some real convincing on our part. She needed to have surgery, but she was the sole caregiver of her developmentally delayed son, so she didn’t feel comfortable going to have the surgery and leaving him on his own. He had never been alone.

The next time we went to visit, he was happier to see us and was not quite so agitated. We took him a basket of fruit, the kind of thing that anybody would want, but we also took some coloring books, some simple objects, and another card from the children. He loved it. He just sat there and smiled and looked at it over and over and then he said, “Were these children in kindergarten?” It was a full sentence not related to anything we said, and he initiated it. The mother looked surprised, and we were very surprised as well. He did talk to us in short sentences, and his mother was absolutely overwhelmed.

When we went shopping to get the goodies for his bags and especially to get the coloring books, we were in our Red Cross vests with our Red Cross nametags on, and the stores would not take our money. Whatever we wanted, they just provided. They would say, “No, you need it. It’s our contribution, because we want to be of help.” We found that all over Washington DC. It was like living in a Zion society. Everybody considered each other their brothers and sisters. Everybody worked together. Even though there was tight security, everybody was kind and considerate and thoughtful. It was magnificent to experience. Everyplace we went it was the same thing. When we walked down the street wearing our Red Cross vests, everybody said, “Yes! We are so glad you are here. What can we do to help you? Where can I go to give blood? Can I give you money?” We would say, “No, no, you can’t give us the money. It has to go through the proper channels.” Everybody was so cooperative. In light of the horrid experiences that our patients and clients told us and the emotional strain it was on us, overall, it was a positive experience. It was very positive to see how everyone worked together.

At the last, we all moved to the Marriot Hotel, which was across from the Sheraton. The Sheraton was where all of the families from the deceased victims were staying. Between the government and American Airlines, they brought all of those families together. The families didn’t pay anything for staying there. Red Cross helped transport them so that everyone could get there and then the government, military, and the airlines paid for their hotel rooms, all of their meals, and all of their needs. All of the organizations that they needed to see, such as the Social Security Administration, the branches of military service, and the American Red Cross were on one floor of the Sheraton. There was a casualty officer, a military person, assigned to each family. The casualty officer would make the appointments and then go with the family to make sure everything was done for them. They didn’t have to chase to a lot of offices and they didn’t have to worry about whether they had forgotten anything because they were so distraught. The casualty officer would see to that. I said that the government and American Airlines paid all of the hotel costs, but Sheraton, Marriott, and Holiday Inn all donated lots of rooms. For example, Holiday Inn provided rooms for all of the families who had members at Walter Reed, Arlington, and Washington General. All of those families could stay at no cost for as long as they needed to be there. There were lots of other organizations that donated a tremendous amount of services.

During Red Cross disasters, you usually sleep in a sleeping bag, and if you get a shower every so often, you are lucky. Because of the nature of this one, we each had our own hotel room. We slept in a nice clean bed and had our own shower, and if we could stay awake, we could watch television. Local businesses brought meals in every day. It was unbelievable. One night we had prime rib and everything that goes with it. Then we had a pork dinner and several chicken dinners and wonderful sandwiches and salads. So every night a different restaurant brought the dinner, and they served one hundred forty-five people at Red Cross Headquarters besides all of those who were out. There was always tons of food. Everybody kept saying, “This is not like any disaster we have ever been in.” This was the first disaster that I had ever been out of town for. The Salt Lake tornado counted as a disaster, so this was the second one I have been on, but it was the first one I had ever been able to go to away from Salt Lake. The Red Cross expects a three-week commitment from volunteers when they go. I can understand why, because it takes a while to pick up the pieces. The fewer times you have to report off and change people, the less likely you are to lose people between the cracks. I was there for three weeks. The reason I was able to be there for three weeks was that I was on leave of absence from BYU, since I was supposed to be in Jordan for the conference and then for research work.

The highlight of my experience was the unity—the working together. There were a couple of events that were absolutely remarkable. One was a candlelight vigil on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial. It was organized by the local Afghanis, but there were all kinds of religious groups there: Christians, Jews, Hindus, Muslims, and numerous others. Everyone was there together, and it was a tremendously powerful spiritual experience to share. We did a candlelight ceremony at the end of the talks, and the flag came down the steps of the Lincoln Memorial. It looked like it just floated down there by itself, even though it was being carried by people. I just don’t have the words for it. We lit each other’s candles, and there was a sense of unity there.

The name of the whole operation while we were there at the Pentagon was called Camp Unity. Each of us has a tee-shirt that has that emblem: hands holding the Pentagon in a circle with a flag in the background and then underneath it says “Camp Unity.” We really felt that.

We were able to go to the Kennedy Center for a concert. The National Symphony and Orchestra put on a concert, along with other performers from across the United States, as a benefit for the families and the Red Cross workers. We had six hundred family members there along with the Red Cross workers. We had the National Symphony in the Kennedy Center hosted by First Lady Laura Bush and Senator Ted Kennedy, and we sat seven rows away from them. We all sang “God Bless America” and stood while they played the National Anthem. There were other tributes that were paid. It was an extremely powerful, unifying force. This is the way we need to live together, and it is unfortunate that we have to have a war to be able to bring us together. I understand that it happened with World War II as well. We were not so good for Vietnam and the Korean conflict, but for World War II and this present conflict it, it has brought us together as a nation, and we really needed that at this time. We have been struggling. It has just been a horrible experience for us, but the big thing that came out of that for me was the unity and the brotherhood that was shown by all.

I went to the temple while I was there and that was a wonderful experience. I had not been to the Washington DC Temple before. I accidentally found it when I first got there because I always have to take the scenic route! I did not go to Church on Sunday, because that was my day to work, but we did have interfaith church services at Red Cross Headquarters almost every evening. Out of that we had many interesting religious experiences. We had a mixture of people, and I said, “I am not acquainted with doing a service that way. Tell me how that works.” For instance, on our care team there was a Protestant and a Catholic. We talked about some of the differences and similarities between Latter-day Saints, Protestants, and Catholics. It opened up the conversation. It was a spiritual discussion. As we would go to the candlelight services and listen to those speakers from each of those religions, underneath it all was the brotherhood of man and the love of our Heavenly Father. They may call Him by different names, but the same concept is there. If we can build on those similarities, on those strengths, then we are so much better off. There will come a day when we all are one church, but those relationships we build in the meantime are the unifying, strengthening, spiritual experiences that make it easier for people to come into the gospel.

It has been interesting to listen to the debate going on across the country. It is a bad thing that anyone is questioning how the Red Cross money is being used. The money that goes to Red Cross is not meant specifically to hand over to people. It is meant to provide relief. Well, there are lots of ways that people need relief. All of the supplies that we did purchase cost money, though we didn’t have to purchase a lot of things. Getting that many volunteers to the site cost money. Each volunteer provides thousands of dollars’ worth of relief. They’re not paid for it, but their expenses are paid. Red Cross has arrangements with airlines so that the cost of airline tickets are very low. Each of the families involved got a blanket amount of three months’ worth of their living expenses: rent, groceries, credit card statements, car payments, transportation, whatever they have as ordinary expenses. Then there were also grants that paid for additional food so that they have a supply on hand. People who have lost personal items have those items replaced. One lady lost both pairs of glasses in the Pentagon. She had to have them. Those didn’t come out of the Red Cross funds, because I made a telephone call to Lenscrafters in her small New York town, told them that her prescription was less than one year old, and asked them if they would please donate her glasses. In less than an hour I had a call from Lenscrafters in DC. They had received a call from the Lenscrafters in New York, and they were FedExing the glasses over to the lady at that very moment. In less than two hours from the time I made the call, she had two pair of glasses. The Red Cross will take care of lost medications, lost glasses, or any lost things that make a difference in people’s lives. All of those things cost a tremendous amount of money. In addition to that, these people are not going to be free and clear in three months. They are going to have long-term needs and there will continue to be funds paid out.

There is a little bit of criticism that you have to prove that you qualify to be a recipient, but I’m sorry, I dealt with ex-husbands and ex-wives who wanted their three months’ worth when they hadn’t had anything to do with the family for two or three years. Those kind of people come out of the woodwork in a disaster, the same way the goodness and the sharing and the brotherhood come out. There are always people who want to take advantage, so you do need to have rules and regulations. The Red Cross rules specify that the funds must be spent for the purpose for which they were gathered. The money will go into the disaster fund over a period of time. You don’t just automatically put it all out there and say, “Here, come take all this money.” That is not helpful. We ask, “What are your needs, and how can we meet your needs?” rather than say, “Here’s money, go do it yourself.”

I think there will be enough money because there are a lot of people who are donating to a lot of causes: United Way, Salvation Army, relief funds for firemen and policemen, and pension funds for all of the organizations. Most people have life insurance and social security benefits to survivors, so children will always have that kind of money. The idea is to meet people’s needs without paying out a lot of money unnecessarily. If you are getting college tuition paid from one fund, there is no need for another fund to duplicate this. It takes a long time for those things to be worked out.