Operation Desert Storm: The First Gulf War

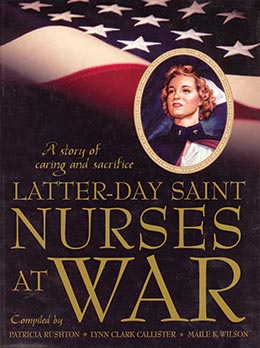

Patricia Rushton, Lynn Clark Callister, Maile K. Wilson, comps., Latter-day Saint Nurses at War: A Story of Caring and Sacrifice (Provo, Utah: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2005) 199–270.

Historical Background

On August 2, 1990, Iraq invaded Kuwait. Kuwait asked the United States for assistance in defending themselves, and within five days United States F-15 Eagle fighters arrived in the Persian Gulf from Langley Air Force Base in Virginia to begin Operation Desert Shield, an effort to liberate Kuwait from Saddam Hussein, the political leader of Iraq. The United States was able to put together a coalition of more than thirty-five nations who supported the military liberation of Kuwait (moral support, troops, money, and supplies). It was clear that the United States would carry the major burden of the effort. On August 22, 1990, President George Bush authorized the call-up of the reserves. Reservists began to mobilize in preparation to go to the Gulf for combat and to receive casualties. Areas were prepared to receive patients in the Gulf, in Europe, and in the United States. The activities in August began a five-month diplomatic effort to liberate Kuwait and stop the conflict. However, on January 17, 1991, a one-month air war began to try to convince Saddam Hussein to leave Kuwait, with no result. On February 22, President Bush delivered an ultimatum to Hussein demanding that he withdraw from Kuwait by February 23, 1991. When no withdrawal came, United States armed forces moved into Iraq and Kuwait. Though there had been much concern about a substantial resistance from Iraqi forces, little resistance was encountered and on February 26, 1991, Kuwaiti resistance leaders declared that they were again in control of Kuwait. On February 27, President Bush ordered a cease-fire at the end of what is sometimes referred to as the “one-hundred hours’ war.” On March 3, 1991, Iraqi leaders accepted the terms of the cease-fire. During the war there were 148 combat deaths out of the 533,608 troops who served in the Gulf War. Another 145 died of non-combat-related conditions. One hundred thousand Iraqi troops died during the conflict and three hundred thousand Iraqis were wounded.

Though it has been over a decade since the first Gulf War, nursing literature is still being generated about lessons learned from that conflict. One registered nurse, Heather Worthington (1995), said of her experience in the Gulf,

We worked twelve-hour shifts, five days a week. The hospital was thirty minutes away, so bus transportation was important. The buses were always packed. Driving on the Saudi highway was a terrifying experience. I was less afraid of getting killed by a Scud missile than being in a bus accident on the highway. Our young bus drivers didn’t have much experience. Also, young soldiers who thought they were “Rambos” rode shotgun. I thought, “Why don’t they give the duty to our Vietnam vets who understand that weapons are serious?” We were loaded into buses with our backpacks, gas masks, helmets, and weapons. We learned to live with the gas masks day and night. (18–19)

Worthington (1991) spoke of the short preparation time many military personnel personnel dealt with during mobilization in the Gulf conflict.

I had only four days to prepare before reporting to my mobilization point, Fort Lewis. This left very little time for family goodbyes. Nothing seemed real through the transition. I felt like I was having a bad dream from which I would soon awake. Tears were always close. Leaving home, I was not even sure of my destination—Germany or Saudi Arabia. (29)

We had twenty-four hours’ notice when we left Saudi Arabia. Leaving was another new adjustment, especially for the women. Throughout the entire stay, we had no responsibilities except to our job and to ourselves. We went back to Fort Lewis via Cairo, Ireland, and the Arctic Circle—a striking contrast from the desert. We were warmly welcomed at Fort Lewis. From there, approximately thirty of us flew into San Francisco, where more than five hundred people were waiting for us—members of our units and our families. The emotion and anticipation of seeing loved ones again and of being back in the United States was overwhelming. (34)

Worthington also spoke of her feelings about the combat experience in general.

As I recount these events, the experience retains a sense of the unreal, as if I had traveled to the “Twilight Zone.” My part in the war was an experience filled with contrasts—impoverished apartments, sparse surroundings, and war paraphernalia set against service in a modern hospital with wealthy clients and gourmet food in the cafeteria.

I felt a profound resurgence of patriotism. Homecoming brought tears and a full range of emotions that were different, yet just as intense, as those I felt upon leaving. I felt I had been a part of a much larger group, part of a true international force. Together with persons from many nations, we formed a multinational treatment team, all working toward a common goal. (34)

Kent Dean Blad

Kent Dean Blad

Kent Dean Blad

Serving in the Persian Gulf War was definitely an interesting experience. My wife and family, we have been truly blessed because of it. We also had many challenges because of it.

Just to give you a little chronological scenario, it was on Saturday before Thanksgiving 1990 that we were at our regularly scheduled monthly drill at the National Guard. I was a member of the 144th Evacuation Hospital out of Salt Lake City, serving in the operating room as an OR nurse. Many units at that time were being activated or put on alert to go to the Persian Gulf to help out with the conflict that was occurring at that time. At lunchtime there was an emergency formation called, at which time our commanding officer informed us that not only had we been put on alert, but we had been activated, as of Thanksgiving Day, which was four days following our notice. For me, the reaction was one of fear, mostly because of the unknown. I had four days in which to get our (my family’s) lives in order, get our finances taken care of, get our shots, insurance—all the technical things that would need to be done in a four-day to physically leave home—not knowing when we would be back. Even worse than that, we were given four days in which to mentally get ready. I think that was the toughest of the assignments. Thanksgiving Day we did spend at home. They were kind enough to let us spend the morning and the afternoon at home. The buses left in the evening for Fort Carson, Colorado.

We spent approximately the rest of November, all of December, and the first week of January at Fort Carson. In January we were given our station assignment in Saudi Arabia. We flew over on commercial air transportation. We landed at night with the lights on the plane and on the runway dimmed, so as not to be identified. We spent three days, immediately upon arrival in Saudi Arabia, in a makeshift barracks or apartment complex that was sitting empty there until we were to get our exact location to set up our hospital in Saudi Arabia. The place we stayed for those first three days in Dhahran, Saudi Arabia, is the same building that was hit by the Scud missile toward the end of the conflict that took out the majority of our casualties in the Persian Gulf War.

We were assigned to the airport, the Riyadh Airport called the King Fahd International Airport in Saudi Arabia. Our hospital was to be set up at the side of the runway. As casualties occurred they would be flown in, the planes would stop right on the runway, the doors would open, and they would empty them right into our tent hospital.

We were very fortunate in that we saw no casualties that led to deaths. We only saw one individual with a combat-related injury. The rest of our patients were more or less accident victims—vehicle rollovers, broken limbs—that sort of thing. We did not receive a tremendous number of patients. At any one time we probably averaged ten to twenty patients in our hospital a day. We were very grateful for that. The conflict ended the last day of February, but we were asked to stay on for an additional time period to be medical support for the troops while they were evacuating out of the country. So we did spend a little more time there than a lot of the soldiers who were in the conflict.

But my story today is not about times and dates. It is more about experiences that we had, about feelings that come in such a situation, and about lessons that were learned from that conflict. At the time my wife and I had four children, all under the ages of seven—very dependent children. It was a difficult time. We had a newborn and it was a very difficult time to leave my wife and children. But through the events that happened, there were a lot of blessings that came. It was very difficult leaving small children who did not understand that Dad was going to be gone for an unknown period of time. We did not know if it would be temporary or long-term or if I would even return at all. What do you say to your children, when you don’t know what the future is going to bring? It was a very difficult thing and one that we certainly do not wish to repeat. It was very difficult leaving a wife right in the middle of raising a family, having had a very wonderful relationship. We were right in the middle of our lives. We were loving life at the time. Things were going great. Things were pretty much turned upside down from this experience.

I would like to share some of the things I learned. Probably the main lesson that I learned was that having four days to get our lives completely in order—physically, mentally, spiritually—there was not a lot of time. The lesson learned was that we never know what tomorrow will bring. We should live today as though it might be our last. I don’t mean that in a doomsday way but in a very positive way. We should treat others as if this may be the last time we ever see them. We should treat our family members as if this may be the last day that we are with them. Life is very fragile and we never know what tomorrow may bring. I would hope that we would treat others and be kind to others and do it as if tomorrow might not come for us or for them.

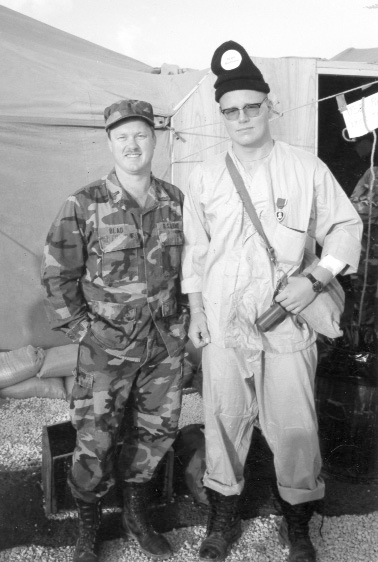

Kent, left, with a patient would be willing to give our lives for

Kent, left, with a patient would be willing to give our lives for

I learned also that we should cherish freedom and hold it so close and dear to our hearts that we it; that we should have wives and husbands who would be willing to sacrifice a spouse for that freedom and children who would be willing to give up a father or mother if need be to protect the freedoms that our country is based on.

What I learned was a great lesson on priorities in our life. All of a sudden, it was not important what kind of car we drove or what kind of a home we possessed. It was not important what kind of sports we played in high school. What we thought was important at times quickly switched to things that really are priorities, such as families and loved ones. I learned very quickly and in a big way that where your heart is there also will be your treasure, and that is what we should focus on in life.

I also promised myself that if I made it through this conflict, that in the future if I ever had to choose between time and money I would always choose time—time to be with my family, friends, and associates—time to be with those that I love.

We may find times in our lives when we are totally helpless. No matter how much control we think we have over our lives, we must always remember that we have to have faith and trust in the Lord. We are not in control of things. There is a higher power beyond us that controls the big scheme of things. That was brought home ever so emphatically in this situation.

In addition to what I said about cherishing freedom, we should always cherish the things that we love the most, and not take them for granted: our families, our friends, and those around us that we care about so much. We should not think that they will always be here for us, no matter what, because that may not always be true.

The next thing I learned is that the gospel and the family are everything. Without those two things, our lives would be pretty empty. I cherish them even more now. I thought I did before but even more after this happened. Those two things became the main focus of my life.

Another thing I learned was that the time we spend on things should equal the priorities that we have. The things that are lowest on our priority list should not be the things that get the majority of our time. The time spent in our lives should be equal to the importance of our priorities, whatever they may be.

I learned that there are great rewards in service. How many times are we told in the scriptures or asked to provide service and commanded to be of service and to love like Christ did? Even though each individual soldier who went to that conflict may not feel like they alone made a great impact, collectively there was a great impact by all the individuals that were involved. Having an opportunity to serve and to love those things that I cherish so dearly was a great blessing in my life.

I learned to always be positive. Too often in life we focus on the negative aspects of life. We spend a lot of time and attention thinking and talking about negative things, when in essence, life is so short and fragile, it should be just the reverse. Our time should be spent with positive things and our attitudes should be positive. We should approach things always in a positive manner. We should treat others positively.

I learned that you should treat people you love as if you really love them. Don’t just go through the motions. Show with your time, energy, and actions that you really do love them. Being kind to others is a good insurance policy. We never know when we are going to need others to be kind to us. I am thinking specifically that when I left that Thanksgiving night, I left my family not knowing if I was going to return. Knowing that I would be gone, I prayed so hard that people that we had tried to be kind to would show generosity and kindness toward my wife and children in the absence of their husband and father. I prayed that I would now be the recipient of that 100 percent home teaching that I had tried to do for so many years. The day before I left, the bishop came over and met with us in our home. He asked us, as kind as he was, what he could do specifically to help us while I was gone. It was not the need of food, it was not the need of money, and in fact, it was not any physical need that we had at that time. I begged the bishop to please be sure that my wife received the best home teachers that he had in the entire ward, someone that could be dependable, somebody that may come on another day besides the last day of the month. He had assigned himself and his wife as our family’s home teachers. According to my wife, there was not a week that went by without him checking in. I’m sure it was probably closer to daily visits. The children’s birthdays were not missed; special events in our family were attended to in a great way by this great man and his good wife. So, we should remember that if we are kind to others, we may end up being a recipient of that kindness from them. We should always treat others with kindness.

The next lesson learned is that righteousness always prevails. Sometimes it takes a little time for that to happen, but righteousness, goodness, and honesty—the best thing that could happen will always prevail.

One of the last things, but certainly one of the most important things, was my gratitude to my Savior for many things—for protecting me and for protecting my family. Being over in Saudi Arabia, in the Arabian Peninsula, close to the birthplace of our Savior, there were many nights that I was very lonely. There were many nights that even though we were surrounded by many people, loneliness and missing our families set in. That is the worst feeling that anyone could experience. On those nights of loneliness, I would go outside and stare into that sky, that Eastern sky that held that star on the day that our Savior was born. That was a great comfort. It was a great feeling and a great thought to know that for the first time in my life. I was able to stare at the same sky that the wisemen and the people around the time of the Savior’s birth had stared at. I was grateful to my Savior for my wife’s sake. My only prayer, the whole time that I was gone, was not that I would be protected, but that my wife and children would be well cared for in my absence. My wife relates experiences that are very sacred and very private, particularly of protection and help that she did receive. She said that at no other time in her life had she felt so secure. She felt protected to the point that she would not hesitate to leave the windows open at night in our home, which for her is major breakthrough. She is very security seeking. We did not live in a great area of town at that time. She said that she felt that there was a shield, a protection that was over our home at all times. That meant a lot to me.

My oldest child at the time was seven, and his name is Matthew. He was the only child we had at the time that could even remotely understand that his dad had to leave and that it was not necessarily Dad’s choice, even though I was grateful for the opportunity to serve. I sat each of the children down and said goodbye to them. As I specifically said goodbye to him, not knowing his level of maturity or sensitivity, I said to him, “Son, I’m going to have to go now. I don’t know when and I don’t know if I will be able to return. Since Dad is going to be gone, I need you to be the man of this house. Mom is going to need a lot of help and Dad will not be here to help Mom like he wants to. I would ask that you would now take over as the man of the house.” The day I arrived at the Salt Lake Airport, where we were released from duty, he ran to me with his arms out. We embraced for a long period of time, as fathers and sons often do. He said, “Dad, I’m so glad that you are home because I am tired of being the man of the house.” And I saw a physical release come over him. Little did I realize that he had taken me so literally that day when I asked him to be the man of the house at seven years old. He was physically exhausted from trying to help his mother. There were many lessons that I learned from that experience about children and about human nature in general and about being a father in a family. I have been ever so grateful to him for the valuable lessons that he taught me with those one or two sentences that he muttered that day. I was anguished and pained that I had put that burden upon his shoulders but was grateful for the seriousness with which he took them and was grateful for the lessons that he taught a mom and a dad that day.

Even though we did not experience great numbers of casualties through the Persian Gulf conflict, there were many valuable lessons that were learned. My wife and I feel like that was a turning point in our marriage, which was very good at the time but became even better. There was a bond that occurred there that could never be broken. There was a newfound love for my country. Ever since that very day that I returned home, I cannot see a flag or hear the “Star-Spangled Banner” without privately coming to attention and paying respect for the symbol that flag represents. I am deeply offended by those who choose to talk negatively or unfavorably about our country and our flag, especially those who have never had to pay a price or who are so willing to be the benefactors of those who have fought for their freedoms. Yet they bad-mouth those very freedoms that have been protected over the years. I am grateful for the opportunity that I had. I feel like it was a huge blessing in my life. In a lot of ways it was an answer to many prayers and in six months time I surely grew many years beyond my age. I will ever be so grateful. We have benefitted financially, physically, and most importantly, our family has benefitted spiritually from that experience. I am ever so grateful to my Heavenly Father for that.

Paul Levi Blad

In 1981 I was doing pre-med courses at Snow College and decided I needed some financial help. That is when I joined the army. After joining the Army National Guard, I trained to work in the operating room as a technician. I did that at LDS Hospital while I attended the University of Utah College of Nursing, plus I did weekend drills for the 144th Evacuation Hospital. After my four years of nursing school, I decided I just wanted a break before I went into a graduate program. I joined the Air Force as an active-duty member and was stationed in Northern California at Beale Air Force Base. It was there that I had a major life event.

My first wife passed away—a sudden, unexpected death. I got off of active duty because of my family situation. I had three small children—one a baby daughter. I came back to Utah and joined up with the original Army National Guard unit that I had previously belonged to. That was the 144th Evacuation Hospital out of Salt Lake City. I had invested enough in the military that I knew I didn’t want to get out completely. Within a year of going from active-duty status to National Guardsman, Desert Storm broke out and I was activated as a reservist. The active duty unit I had belonged to never was activated. Here, I got out of being an active duty member to be Mom and Dad to my children. Then the war breaks out and of course they don’t take hardship cases. They need you for your specialty and that is what I trained for.

I had just gotten remarried when I was activated for Desert Storm. It was about a year after my first wife had passed away. I thought, “How could my poor new wife take on my three children and her two children—five children into this new marriage.” It was a hard time. Basically, we had just come off our honeymoon. We began our marriage with me leaving to go to a war. I did not try to get a waiver. It was my responsibility and I went. I didn’t see my hardship as any worse than anyone else’s. Basically, my life had stabilized because I had gotten married and my children had a support system. Also, my brother, Kent, was activated and left a large family.

Right before Thanksgiving we had a weekend drill. They notified us that right after Thanksgiving we would be leaving. It was a hard, emotional, and sad time of my life because we did not know what we were getting into. We had the impression that Iraq was almost a world power when it came to military equipment. We had heard about the Russian-made equipment and how efficient it was. If we went over, we really did not know if we would be coming back. Of course, that is the situation with any war. It was a very emotional time. And having survived it and looking back, I have to say that a major bond formed between me, my wife, and my family. We survived it together. We feel like we went through a hard time and we survived it. We did our best.

I live in the small community of Kanosh, Utah, total population of just under five hundred. In the entire Millard County, only two people were activated to the war. I pretty much represented the east side of Millard County. I got more support than I could have imagined, but I didn’t realize it until after I got home. It was a good thing for my wife to be in a place where she received a lot of support. It was a time when home teachers and visiting teachers and the whole ward really kicked in. I have extended family in the area and they really helped out. It means more than I can ever say.

We went over to Saudi as a whole unit, about three hundred members. They supplemented our unit with members from all over the nation. Most units have vacancies, and in a war situation vacancies are filled. We received physicians and nurses from all over the nation who were put into basically an LDS unit. At least 90 percent of our unit was LDS with about 60 percent activity. We functioned as a branch during the war. It was really fun to be a part of something like that. Bonding came with it. We were all kept together as a unit when we got to Saudi. It was interesting watching our medical unit function as a branch. Many of the leaders of our unit were bishops or stake presidents back in Utah. Important people in society were taken to a war zone, leaving their comfort zones. We were all so humbled. I can’t tell you the spirit that was there in our sacrament meetings. It was always so strong. Usually the theme was how much we appreciate the gospel, our families, everything we had previously taken for granted. There was a great spirit, and we became very close because of it. We held positions in the branch. Everyone was at least a home teacher or a visiting teacher. We took turns teaching, and we had a lot of testimony meetings. The leadership was already established because we functioned as a branch during weekends before mobilization. Our branch leader was also our commanding officer. We had a chaplain who was part of the branch presidency. There were a lot of inactive people that became very active during that period. However, there were a few people that you would have assumed were strong and active, who went the other way. It was interesting to stand back and watch how people cope with the stress of such situations. For the most part, people usually bonded together and made the most of it.

We were warned not to bring up religion to the Arabs. We befriended many Arabs and some of them actually invited us into their homes and explained their way of life and actually asked us questions about our religion and what we believed in. We were told that if we were asked about our faith, we could respond, but it was not okay to proselyte. I have heard it said that war usually opens up doors of missionary work, so who knows what seeds were planted during this war.

Our unit was designated as an evacuation unit, like a MASH unit. We are supposed to be able to pick up and set up our hospital anywhere in twenty-four hours. We set up our hospital right next to the International Airport in Riyadh, where we could receive the heavy casualties. It was a five hundred-bed hospital, covering just about every specialty you can imagine in a wartime setting. Some of our physicians were actually plastic surgeons. That wasn’t their title in the war, but that’s what they were in the civilian world. We had sixty physicians, three hundred plus nurses, and all the ancillary support and equipment that went with it. I was associated with the operating room section. All of our operating rooms were huge mobile boxes. They popped out to be these incredible two-bed operating rooms. The OR suits were interconnected to the hospital so that we have the same air-conditioning and heating systems and air control.

We were activated and we went to Fort Carson to do our pre-war training, most of which was nuclear and biochemical warfare training. That took two or three weeks. Once we were done with that, it became a waiting game—waiting for our turn to go over. Of course, all of our equipment had to precede us. It was kind of a logistics nightmare. It was over Christmas and we couldn’t decide whether we should bring our families to Fort Carson and have a little Christmas or whether we should we go meet them somewhere. We were told we really couldn’t leave because we could be sent off at any time. That’s why Fort Carson was difficult for families.

I spent a lot of time on the phone. My phone bills got as high as $800 a month. We were lucky to even have access. To be able to call home during the war situation was fortunate. We had to hike several miles to a phone in Saudi, at least at the beginning of the war. Later, as technology came in, we did get phones closer to us. You would have to wait hours sometimes to get to the phone. I don’t remember anyone having cell phones. There were several ways to call home. One was like a ham radio where you say, “Hi honey, I love you, over,” and then she would have to give her message and everybody in the camp could hear you. I really felt that as a newlywed I needed to call home, and I wanted to call as often as I could. I was promoted during Desert Storm from first lieutenant to captain. So the pay raise all went toward phone bills. That was how I justified the phone calls.

They took us from Fort Carson to Saudi in a very large commercial airliner. We didn’t fly right into Riyadh. We flew into Bahrain. It was frightening. There were certain instructions given to every unit coming to Saudi. When the airplane got close to the city it had to turn off all of its lights, and we landed on a very dim airstrip. Lights were out. We were going into a war zone and we did not want to enter conspicuously. When we got out of that plane and walked onto the runway, we were dead silent. The feeling was very eerie. We had just walked into a war. Everyone kept the noise level down. We didn’t turn on our flashlights. Fear of the unknown dominated our thoughts.

They put us up in Bahrain in an apartment complex while we waited for our final assignment as to where we were going to set up our hospital. The apartments that we stayed in are the very apartments that ended up getting bombed at the end of the war. It was hit by the one Scud missile that did get through and ended up killing thirty servicemen. Speaking of the Scud missiles that had come into Riyadh, after it was all over, they sent each of the units a copy of the trajectory of each of those Scud missiles, where they would have hit had they made it through. There were four of those that were projected to hit the complex where we resided. So we were grateful for the Patriot missiles and modern technology.

We had a Patriot missile battery right next to where we were stationed. They were set up right next to our hospital, right there by the international airport. Whenever a Scud missile would come close, a Patriot missile would go off. They sent two Patriot missiles at each Scud missile. They did that in case the first one missed, which they rarely did. Sometimes one would hit the warhead of the Scud and the other one would come by and hit the rest of the missile.

We were in Saudi a few weeks before the war actually started. Our hospital was already set up and we had already started to work shifts in the hospital. The hospital was twenty or thirty miles away from the apartments that the Saudi Arabian government gave us to stay in. We would be shipped in for our shifts, which were twelve-hour shifts. The first night of the war they sent thirty-eight Scud missiles. We medical types had no idea what was happening. All we knew was that there were a lot of explosions, a lot of earthshaking, and we thought we were right in the middle of it. I was not on shift at the hospital on the night the war began. My brother and I and our little group had actually gone to watch the football playoffs at about 1:00 in the morning. We had to walk several miles to where we knew there was a TV. I remember it was half-time. We decided we would leave and go get some breakfast. They had mess halls set up everywhere and we were in the mess hall eating breakfast about 1:30 or 2:00 in the morning when Iraq started sending the Scud missiles. When the first one hit the lights went out. We basically just took cover. None of us carried weapons and didn’t know what to do anyway. We were in the mess hall, took cover under the tables, and just listened over the next few hours to one explosion after another. When this all happened, there were a lot of people in there. It was pitch dark. The attack lasted two to three hours. We did have our gas masks and chemical suits, and we were trained to get into those immediately. So there we were, all decked out in our chemical gear, and it was very hot. Eventually, we high-tailed it back to our apartment complex.

Being stationed next door to a Patriot missile battery, we experienced the power of such technology. Each Patriot missile being launched felt like a double earthquake, one explosion from the concussion of the launch and another as it broke the sound barrier right out of the launchpad. The biggest explosion of all was when it would connect with the Scud and then everything would just shake. Pieces would come flying down around us. In the daytime we could go around picking up shrapnel. At home I have pieces of Raytheon circuit boards from the missiles. Fortunately, none of us got hit with any of the debris. It was a bewildering situation. We were trained not to panic, but fear of the unknown and not really knowing what your place is in such a situation was just different.

During this war we treated many more non-war casualties than war casualties. We were next to their freeway, and we treated civilians involved in accidents. We were willing to take any patient we could as we had ample medical gear and personnel waiting to do something, not wanting to lose their skills. As far as war casualties, the few that we did get had already been seen by frontline medical units and so they had been treated and triaged to the point that they were stable. We performed some surgeries: appendectomies, exploratory laps, on-the-job injuries, heavy-duty lacerations, sandstorm accidents.

Approximately 50 percent of our unit was male and the other half female. While we were waiting for the war to start we befriended the Saudi medical personnel. We actually went to their hospitals and worked alongside them in a teaching/

The physicians were so concerned about losing their skills. We were seven months over there. We arrived there the first part of January 1990, and we left the end of May or first part of June. We were one of the last units to get there and get set up. Because we were set up so well and had a reputation of efficiency, they decided to keep us behind to support the troops. We were the designated medical support for the exiting troops.

By the time we got home, the ticker tape and parades had pretty much ended except for my little community. When I came into town they were waiting outside with the town fire engine and they made me and my family get on and ride down the only street in town. Folks were waiting and welcoming me home. At the Fourth of July parade in Fillmore, I was designated the grand marshal. While I was gone, the staff at the hospital doubled up and covered for me, so when I got back I tried to pay them back by working some extra shifts, but they were so supportive. I received several letters and postcards from them. The support was just incredible.

In retrospect, from a family standpoint, the war turned out to be one of the biggest blessings of my life. While I was gone for seven months, my three children learned to love their new mother. When I came home, she was their mother. There was no stepmother/

We learned to entertain ourselves and keep busy. We had Olympics between us and other countries, like the Swiss unit right next to us. We would have get-togethers and entertainment shows. My brother Kent and I had the unwritten assignment as entertainment specialists and tour guides. We took tours into downtown to the perfume and gold shops. These activities appeared to aid in building morale during such stressful times.

None of our people were hurt in action. Some of the ladies were sent home because of pregnancy. We had a couple of on-the-job heavy-equipment accidents, but no one was sent home because of them.

One of the great lessons I learned during the war was how important our freedoms are as Americans. When Iraq left Kuwait and the war was basically over, we were allowed to go in and help where needed. We would go into Kuwait, only as small groups as a security measure, because there was always the threat of terrorism and a few bands of Iraqis left behind that weren’t very predictable. The streets of Kuwait City were pretty empty, but the Kuwaitis would come up to us and thank us and cry at our feet and do anything they could think of to show their appreciation for what we had done. When we left Kuwait, all the oil fields were burning and that was a really eerie feeling. We went to the freeway that leads to Iraq, Thunder Hill. During the conflict, all the tanks and Iraqi troops were trying to get back to Iraq by that route. Our air force just bombed it all. The sky was black and the sun looked like blood from the burning oil, and there was a feeling of death and destruction and darkness. I can’t tell you what it felt like. It penetrated to the bone. It has had an everlasting effect on me. It certainly felt like a sign of the times.

I learned three lessons from my combat experience. First, I am so grateful to be a member of the Church and to have the gospel and the blessings and security of the plan of salvation. Second, the strength of family and their love and support through prayers and letters meant everything. Finally, love of country. Having experienced firsthand what it would be like to be stripped of your freedoms by a neighboring country, I would defend our nation at all costs.

Susan Herron

Susan Herron with a flag that

her unit kept in their plane

My name is Susan Herron, and I have been in the air force reserves since December 1988, when I was commissioned. It was one of those things where I was reading one of my nursing magazines, and it said, “If you want to see the world, join the air force.” They were right because I’ve been all over. I knew that I didn’t want to spend my weekends in the hospital, that’s what I did during the week, so the air force offered the opportunity to be a flight nurse and to fly around. The army uses rotary aircraft, like helicopters, for medevac. They’ll go in and get the sick and wounded and bring them to us. We fly in a large cargo plane to do the long haul.

For Iraqi Freedom, we had a very complicated thing to start with. We started out in England, then we would fly down to Sicily. We would sit alert in Sicily, then we would go to Kuwait and pick the patients up and fly them to either Germany or Spain. It was a huge circle. As the war progressed, they eliminated some of these spots. Pretty soon we ended up going from Germany to the desert, Germany to the desert, and so forth.

The planes that we mostly flew on were the C-141s, and they are capable of transporting 103 litter patients and then a mixture if you have ambulatory patients. We had a combination of patients. Some of the patients would come on the plane and they had an abnormal pap smear. Other patients would come to us on ventilators with head injuries or blast wounds or burns. You saw everything. We had Landstuhl, which was a big hospital in Germany that had the capability for everything. They could handle trauma and all kinds of stuff.

After we took care of the service members, we never really knew what happened to them. What we did know is that we took them to Germany, and then occasionally we would do a mission to the States and we would bring some of the more serious ones stateside. We never really saw them after that. Now I’m assuming that there were many that returned to duty. We were deployed from February 2003 until August, so about six or seven months later.

We never seemed to stay in one place for more than two days. We were in England for two days, and then we would fly to Sicily. Then we would crew rest, get ready for a mission, and stay there for two days before going to Kuwait. In the initial part of the war, we would just land in Kuwait and go on, and that made a twenty-four-hour workday for us. We would be dead after that. Then they decided that they were killing the aerovac crews, so they decided to allow for crew rest. Even then when we hit Kuwait, we had to off-load all the cargo that they put on the plane and set up everything for air evacuation. By that time, we were twelve hours into our day, and we were dead tired already. It was also 120 degrees outside, and we were in a metal tube. We would pick up all our patients and then fly to Germany. That was another overwhelming thing. When we were in Sicily, we would get a basic initial report of how many patients we were going to get. They would tell us that we would get twenty to thirty patients, and that in itself was kind of overwhelming because we had three nurses on the plane. So then we land in Kuwait and they come on the plane and say, “Oh, you’re getting seventy patients today.” Seventy patients! It was crazy.

Our patients were mostly active duty. We did have a couple of Iraqi nationals. Most of them were humanitarians. I remember one was a sixteen-year-old girl who had burns. Another one was an Iraqi freedom fighter. There were a couple others interspersed in there. Most of the time they had an interpreter with them. That really helped. Otherwise, we used body language. You have to be very careful, especially if you’re dealing with the males, because females couldn’t touch them or even approach them. You really had to keep that in mind. We Americans are very touchy-feely. That’s how nursing is.

Susan caring for casualties on an aerovac mission

Susan caring for casualties on an aerovac mission

There were three nurses on the flight crew. One nurse would be the medical crew director, who was in charge of paperwork and coordination and all that kind of stuff. The other two nurses would split the plane in half. One nurse would take one side of the plane, and the other nurse would take the other side of the plane. So you started at one end of the plane and you just worked your way down. You gave medicines and bandages, started IVs, gave morphine pushes, charted when you could, and did whatever else you had to do. By the time you finished and got down one side of the plane, you had to start all over again. We have very strict guidelines and regulations on narcotics. When a client comes on a plane with narcotics, you do a double count and chart that. Well, when you have seventy patients and at least half of those are coming on with tons of morphine, there’s no way to count it and no way to account for it. So you’re just pushing morphine and hopefully charting it because there are so many that you’re doing. Everything took so much time because we were mixing all of our IV antibiotics since nothing came premixed. It was overwhelming.

One of the things I realized when I got back here into the urgent care emergency room here at the VA was that there were some days that I really enjoyed my job here and other days where I felt this stressful feeling. I realized that I was having some feelings, I don’t want to call them flashbacks, because that just sounds so veteranish, but it was that overwhelming feeling, the feeling of being overwhelmed and being out of control and not knowing if you could do it because there are so many things that needed to be done. When we have fifty patients out in our waiting area and they all need to be seen now and you can’t get to them all, it’s just like seventy patients being on your plane and each one of them needs something, but you can’t do everything. Again it was that overwhelming feeling that I felt during the war and I didn’t like that, so I started to think that it was time to go on to a more structured environment, so that’s why I was looking for another job position.

I’m going to have to word this carefully because this was one of our difficulties. They tell you to train the way you’re going to go to war, so we train a certain way. We have our medical supplies packaged a certain way. We go on training missions. Like this weekend, I have a training mission coming up. We’re going to bring our supplies and set up the plane, and we’re going to have people playing patients and people playing crew members. We will have diagnoses for these patients, and we will have to go get supplies out of our kits to take care of these patients. That’s how we train. Well, I don’t know when it was, whether it was the week we left before the war or the week after we got to the war, but they changed the packaging guidelines. It was great in theory because the theory was if you have between ten and twenty patients, you’re going to take bags one through three, so you only have to take three bags. If you have between twenty and fifty patients, you’re going to take two extra bags. Okay, now that’s five to seven bags we’re up to, but it was still manageable. That was the theory. If you have fewer patients, you’ll take fewer bags. So that was great. However, like I say, when we got to Sicily, we were told we were going to have twenty to thirty patients, but by the time we get to Kuwait we were told we have seventy. So we ended up bringing every single piece of equipment and every package of bags full of all our stuff on each and every mission. So now that the packaging guidelines are different, we don’t know where to go or which bag is what. It didn’t really help, because we had to take everything anyway. So when you’re looking for IV tubing, it used to be in bag number three, but you’d have to look through the packaging guideline. Then you would have to look through sixteen pages of the packaging guideline to figure out which bag it was in, and your patients are screaming in pain. You don’t have time to be looking for stuff like that. It was very frustrating to have things change right before we went to war. Initially, we had enough stuff because we were only carrying twenty to thirty patients during the first couple of weeks of war. After that is when we started getting our missions of fifty, sixty, seventy, and sometimes up to eighty patients. Then we started running out of things like saline flushes, piggy backs, tubing, needles, syringes, or other things you were using all the time for a lot of patients. What we as individual flight nurses started doing after every mission was repacking our kits. We all had our own little kits, our own personal bags that we would throw a bunch of extra stuff in, the stuff we knew we were going to be using so much of, so we all had extra supplies with us. It happens to you once and you learn, and then the rest of the time you’re prepared.

I was deployed three times. I went on Operation Restore Hope. That started in 1992. I was deployed in 1993 for it. It was the famine relief effort in Somalia. You might remember it from the movie Black Hawk Down. It started out being a humanitarian effort. We went there to feed the hungry people, but it didn’t turn out like that. I was a flight nurse then too, and we spent half of our time in Cairo, Egypt, where our base was. We would do rotations down into Mogadishu. We spent two weeks in Cairo, two weeks in Mogadishu, two weeks in Cairo, and again two weeks in Mogadishu. Our plane would take off from Cairo, come down, pick up the patients, and fly back to Cairo and then on to Germany. That was our ultimate destination. If we had a really sick patient who couldn’t tolerate a stop in Cairo, we would go all the way on to Germany, which was a ten-hour flight. It was really hard on the patient and hard on the crew. But sometimes you just have to do it. It was a United Nations effort. On the flight line in Somalia, you had the different countries camped all the way around the flight line. You had Americans

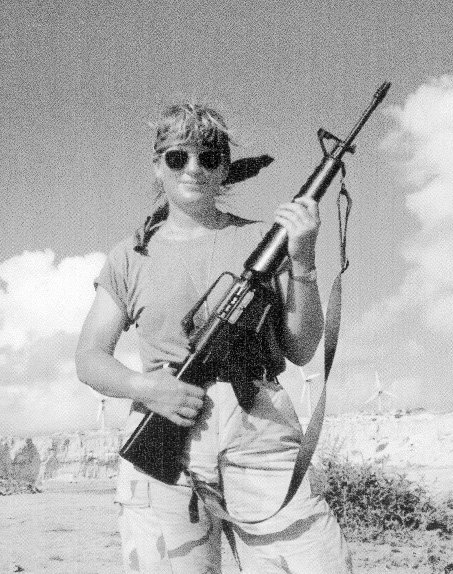

Susan with the marines in Somalia, 1993

Susan with the marines in Somalia, 1993

here, Pakistanis there, Egyptians here, Romanians here, Germans there, and Italians here—every country you could imagine. It turned out really well. If you had some connections, you could go to dinner at a different country every night. We carried a lot of American military, but we also did a lot of humanitarian missions. The Pakistanis got ambushed, and there were fifty patients. We regulated those to go to Pakistan, so we actually sent one of our aircrafts into Pakistan. It was the first time in I don’t know how long. We did not have good relations with Pakistan back then. We sent fifty of their soldiers back with our medical crew taking care of them. That was really cool. We never took any Somalis out. They pretty much stayed in country. I don’t remember any of them going out.

There were nurses on the ground as part of the humanitarian mission. The army was there as the ground unit. They initially were at the flight line as well. They got bombed a couple of times, so they decided it wasn’t a good place for the hospital to be. They moved into town, which didn’t seem much better either, because then they were right in the thick of things. So we would have to convoy initially to go up to the hospital to see patients or to do whatever we needed to do preflight because there are things you’ve got to tell patients or make sure they have before they get on your airplane. Initially we would just get in convoys and go up to the hospital, but pretty soon that became too dangerous because people were getting either sniped or bombed or whatever. So the army had the helicopters there, Blackhawks, and we would just ride the Blackhawk to the hospital. That was really cool because you don’t get to fly in a Blackhawk helicopter all that much. That was a lot of fun. Pretty soon that too became very dangerous.

Did I feel like I was threatened? You know it’s funny because people ask that, especially when you get back. They always want to know how close you were to being shot at or something like that. For me, I must always have a false sense of security or I just know that I’m being protected and watched over and that whatever happens is going to happen no matter what. I know I have to be careful, but when I was deployed and doing my job, thank goodness for me that was always way back in my mind. I’m not so concerned with safety or things like that. We did have a couple of instances. We had gone in a convoy to the hospital and there were several of us in the convoy and we were done with whatever we had to do. It was me, one other flight nurse, and the SP. We were in a Humvee and we were done with our task, so we just thought we would go ahead and drive back. The convoy was still doing their stuff, so they stayed. Well, I won’t mention names. The marine that was our SP escort asked if we wanted to take a different way home, because we would always take the same path back and forth. So we said, “Sure!” We went through a district called K-4. The day after we went through there, we were banned from going through that area because it was so dangerous. We were going down this street and there was a car accident in front of us, so that blocked all the traffic. I don’t know how it happened, but all of a sudden there were two or three hundred Somalis coming out into the street. Whenever we drove in a convoy, we always had what we called our kid beater sticks. We always carried a stick because people reach into your vehicle and try to steal things. As they were reaching in you’d swat them, and that was basically your protection. We all had to carry guns. That was the first time nurses had ever had to carry guns. You always had your weapon strapped to your chest. On this particular day, the accident, Somalis surrounding us, the marine was in the front seat of the Humvee and the other flight nurse and I were in the back seat. As this swarm of people started to approach our vehicle, and it wasn’t just our vehicle, there were several vehicles. Thank goodness there was a UN vehicle behind us with a turret gun. The other flight nurse and I ended up back to back in the vehicle facing our respective window with our kid beater sticks because these people were just converging on our vehicle and they were grabbing at anything that wasn’t tied down, especially our sunglasses. So we’re beating people out of the vehicle. They popped the back of the vehicle and start scrambling in and stealing. It’s like you’re just beating people right and left. This whole time I kept thinking, “Please don’t let me have to pull this gun off my chest and start using it.” Then next thing I hear is the nurse who’s got her back to me and she says, “That guy over there has a knife.” I kind of looked around and this guy lifted up his shirt to show that he’s got this huge machete stuck down his pants. He was just showing us to let us know that he had a weapon. The next thing I hear is the marine, our driver, with his M-16 locking up. I was like, “Oh my goodness, please please just let us get through here.” My first thought was, “I wish I had a little piece of paper to write a note to my mom and tell her that I loved her so I could stick it down my shirt, and hopefully somebody would find it.” Then I realized, “That’s so stupid, my mom knows I love her and I don’t need to write a note to tell her.” But it’s one of those crazy thoughts that passes through your mind when you don’t know what’s going to happen next. Anyway, the traffic finally cleared. What seemed like an eternity was probably only about ten minutes. So we get back to the base and I had that incredible adrenaline surge and thought, “We made it. That was the weirdest experience, and I’m so glad we’re here. I will never do it again.” But I’m so glad I had that experience because it was so incredible.

Another time one of the army pilots and I had gotten to be friends. He was going through a hard time at home with his wife and everything. He just needed someone he could talk to. We had concertina wire all around the camp, and we were told never to go outside of that. Well, there was this fuel truck with a bench beside it. It was parked just right outside the concertina wire because, of course, you can’t maneuver the truck inside of it, so we just walked right outside the concertina wire. We were just sitting on the bench chatting. All of a sudden we heard gunfire and we could see the tracer bullets going right over our camp and right over the fuel truck. So we’re like, “Oh, crap.” Here it is. It’s dark outside. We can’t run into camp because camp doesn’t know what’s going on and all they hear is the gunfire, so if they see people running, they’re probably going to shoot us. So we just kind of stayed there waiting to see what was going to happen because there were reports that the Somalis were trying to come over the wall of the camp. So we we’re just sitting there and didn’t hear anything after that. We probably waited half an hour and still nothing, so we thought we needed to do something because we didn’t know what was going on inside camp either, and they were probably looking for us because they must be doing head counts. It was probably about forty-five minutes after the incident. We kind of nice and slowly walked into camp talking so they could hear our voice and know that we were coming. They had blackout conditions in the camp, so we made our way to our individual tents. I got into my cot, and the person next to me said, “Susan, is that you?” And I said, “Yeah, what happened?” She said that evidently some Somalis tried to come over the fence, and the Egyptian guard went crazy and was just shooting randomly all over the place. She said, “I knew where you were, I knew who you were with, so when they came in to do the head count and called your name, I just said ‘Here.’” So I thanked her. Everything turned out fine, but it’s times like that that you don’t know what’s going on. You don’t know how threatened you really are. I guess the different countries took turns posting guards on the wall, and he must have seen people coming up. I don’t know if he was shooting directly at them or firing warning shots or had too much to drink. Who knows?

I think if you thought about these kinds of experiences and knew that they were going to happen, it would be something that you wouldn’t want to go into or do. My mom always used to say that I was looking for adventure, and maybe that’s it. But I don’t focus on the danger of the experience. I think I always have to ask, “Why am I doing this?” Well, I’m doing this for a reason. “Am I willing to do whatever it takes?” Well, yeah, because I’ve already made that commitment and taken that oath, and that’s what’s asked of me. Like I say, if you knew it beforehand, you probably wouldn’t do it, but you don’t know the individual experience that might be the one or the one that comes close. Sure, if we had known that we were going to have our vehicle surrounded and that we would have to beat people out of it, we wouldn’t have gone that way, but you never know.

When I was young, I always used to think I would die at an early age. Don’t ask me why. But that early age I thought was more close to my twenties, and here I am at forty-three years old and I’m thinking I haven’t had that feeling or thought for a long time. I guess I’m not destined to die at a young age. I had another experience after my mom died. She died in 1997. I had this feeling after she died like, “My mission on earth is complete. I have eased my mother out of this world and have helped to take care of her until she could die. Now I feel like my mission is done.” Then I realized I still had my own mission to complete. I guess I just have this innate sense that I’m protected and taken care of and that my Father in Heaven is with me and that whatever is going to happen is going to happen because of the experience that I need to have or the growth I need. I don’t think everyone experiences that, because I’ve had friends in the past who seemed to be afraid of everyday life. Part of me, when I sit and listen to them, has a really hard time. “What’s the matter with you? That’s not right.” And maybe it’s the way they were brought up or they didn’t have that religious background. To live in fear everyday, that’s got to be hard.

Absolutely, I think being in the air force is part of what I’m supposed to be. I became a nurse by accident. My very first job when I was sixteen was in a nursing home, and my job was to wash the wheelchairs, pass ice water, and feed patients. I considered myself an assistant to a nursing assistant. Then I graduated to be a nursing assistant. After high school I was working at this convalescent hospital full time, there was a group of people who were going to go down to the city college and take the entrance exams for the LPN program. I thought, “Hey, I’ll go with you,” so we went. There were probably six or seven of us that went down. I was the only one that passed. I had to ask myself if I was doing this because everyone else was doing it or because I really want to become a nurse. So I thought, “Well, I’m not doing anything right now.” So I went to the LVN program and of course that led to the RN program, which just continued on. I guess for so long I had been working and going to school, doing both at the same time. When I graduated from my RN program, I found myself just working for the first time. Then that’s when I got interested in the law, so I went to law school, and I was working and going to school again. When I got finished with that, boom, all of a sudden I was just working again. I was working at the law firm, and call it boredom or whatever, I guess I just don’t know how to not be busy. It was then that I was looking through my nursing magazines and saw the ad. I went through the interview and said, “Hey, this sounds great.”

Now that I’m not working and going to school all the time, I’m working and doing the reserves. I’ve got at least those two things going still. When I joined the military, I think I just became a different person. It caused whatever was in me to sprout and grow because I was forced into different situations (like leadership positions), and I hated that. Initially I hated being put in a leadership position. Once I did it several times and started to become comfortable with it, I realized I kind of liked it because now I could set the tone. I could not do things my way, but I could make sure things ran smoothly and got done efficiently. I think that’s the part of the leadership position that I liked, so I knew I was destined for the military. If I had known it was going to be like this, I would have joined years ago, and I would have been able to retire by now.

I graduated from nursing school in 1983, and I didn’t join the air force until 1988. I was married at that time. I got divorced and then joined the air force. When I was married, we had some friends, and the wife was in the navy. They had been to the Philippines and lived in all these places. She was active duty. I thought, “Oh, I wouldn’t like being told where I had to live and having to move to someplace that I might not like.” I knew that active duty wasn’t really for me, so I thought, “Hey, the reserves, that’s great because I can live where I want and work where I want. I don’t have to be at Balboa. I don’t have to be in a tent with the army. I can go on a plane and fly and I can stay in hotels.” I chose the air force over the other services because of what I could do with them.

I think that until we have certain experiences in life, we don’t know what we’re capable of doing. It’s the same no matter what you do. If you’re challenged, you’re going to rise to the opportunity. It’s like our callings at Church. My first calling was a Primary instructor, and I thought, “Holy cow!” Number one, I don’t do kids. I’m forty-three and I don’t have children. I’m not exposed to children. I don’t know how to deal with children all the time. Sure I have fun with them and laugh and joke, but to know how to control them and to make them listen and discipline, I don’t know how to do that, so it was really hard for me. But I learned how through trial and error. My next calling was camp director. Well now I had the teenage girls. “Oh my goodness, teenagers!” They’re harder than the kids. I had a lot to learn. I remember the stake leader said, “If you’re ever in doubt, just keep loving them. No matter what they do, just keep loving them.” So that was a real growing experience because you want to say, “No, you need to be over here and not over there!” Then again, going right into the military and being in charge of your crew and being responsible, that’s something that they really can’t teach you. They can teach you the principles, but then it’s up to you to figure out how to apply them through trial and error. You don’t always do it right, but at least the job gets done.

I remember my mom asking me, when I first became a nurse, “Susan, how do you do it? How do you deal with all the stuff you deal with during the day and then come home and be like a normal person?” And I said, “One day as I walked in the hospital and came through the front door, it was like a feeling. I could feel that I became another person.” I must have put up that protective wall or whatever it is that you do in order to deal with the patient who has cancer or the child who is dying or the family member who is going through all the grief or whatever it is you do during the day. I think we all have our own protective mechanisms that we put up.

I was inactive for a very long period of time, about fifteen years, from my early twenties to my mid thirties. During that time of my inactivity, my coping mechanism was going out and partying with my girlfriends. We’d get drunk almost every night. I look back now and I see that that was a coping mechanism for nursing and for the stress of the day and for the crazy things I had to do or see, especially during deployments and wartime. You get done with your flight, and the first place everybody goes to is the bar. Then in my thirties, when I started going back to church and stopped the drinking and other things, I realized, “Uh oh, what am I going to use for my coping now?” Then it became chocolate for a while. Then it was exercise for a while. Sometimes it’s a book. My escape during the war was a book—to be able to totally focus on one thing and be in another world. That was just an escape. So home life as opposed to professional life during the various years of my life have been a little different. I just did what I had to do. I now know that I need to concentrate on being a social person because as I’ve gotten older, I’ve realized that I’m involved in fewer social activities. When I was younger, we were out all the time socializing. Now that I’m older, I prefer to stay home, and it’s just nice to have the peace and quiet.

I would do it all over again. If there was another war, I would volunteer for that one too. It’s kind of funny because we knew that the war was coming up, we didn’t know when, and they were asking for volunteer lists because we have a squadron of 150 people. In an air evac squadron, they usually don’t deploy your whole squadron. They usually take bits and pieces and make their own squadron with a bunch of different people. So when we knew that the war was coming up, boy I was like, “Are you sure I’m on the volunteer list? I want to see it.” Then when we got the call, it was like, “Uh oh. This is really going to happen now.” But I knew that because I have over fifteen years in that this might be my last chance for a war and my last chance to do what I’ve been trained to do. Maybe you get psyched up your whole career because this is what you’re trained to do and then finally you’re able to do it. There are several people in our squadron like me. Then there are several people like, “Hey you know what, I joined to go to school and to get benefits, and I’ve got a family now.” I totally understand that. I can’t even imagine being a regular reservist and having children and being gone one weekend a month, let alone being deployed away from your home when you have kids. So I’m so thankful that my life worked out to where I’ve been single and I can just float around and go wherever I’m asked to go. But I remember thinking, “This might be my last chance for war, so I’ll go.”

Each deployment is different. For Desert Storm, I was in England. It was a party time. We never saw a patient. We never got on an airplane, never flew. Operation Restore Hope was half party, half scary. When we were in Cairo, we were in five-star hotels and were catered to. It was just wonderful. Then when we were in Somalia, we were in a tent in the middle of a desert, but still that was great. Then with this war, it was totally different because there was no fun and games time. There was none of that party time or that let down and relax time. In that seven months, I would venture to say I had five days off. On those five days, if you were in England, you went down into London, and that was your day off. Once we were in Sicily and we went to Mount Etna. Two more times I had days off in Germany, and that was pretty much it. Your other days were spent getting ready for the mission, doing the mission, or recovering from the mission. Then you started up that whole cycle again. I don’t think of myself as being an adventurer. I think of myself as having a pretty mundane life that every once in a while has these blips on the screen of excitement. I would do it again. Maybe that’s

Susan in a casualty receiving area, 2003

Susan in a casualty receiving area, 2003

a personal thing, but I would do it again in a heartbeat. When we got back, they were asking for volunteers who wanted to stay on active duty and probably go out again soon, and I said no to that. I was dead when I got back—mentally, physically, psychologically, spiritually, and emotionally. I felt like my sense of joy had been taken away, and it was so hard to integrate back into normal life, back into my family, friends, and home life. I don’t remember it being that hard before with other deployments or coming home from my mission or other stretches of time of being gone, so right when I came back I said I was never going anywhere again. But I’ve recovered and am back to normal life, and, oh yeah, I would go back again.

In comparison to other times, when I was deployed for Desert Storm, we were only gone for three months, so that wasn’t a big issue. We didn’t see anything there. We heard about it on the news, but CNN was as close to the war as we got. In Somalia, it was such a great time that that’s why it was hard to come home, because I didn’t want to come home. It was an intense experience and I loved it. It’s kind of like you leave the stress of your normal life and take on the stress of different life, but this stress is different. It’s easier to take initially because it’s a different stress. Then this time, I didn’t really have any preconceived ideas of what it was going to be like because I just had no clue. I knew it was going to be totally different. When we got there, we were separated into crews, so I knew who I was going to be flying with. I had a great crew, people who I flew with all the time at home. Well I do one mission and then they split the crews up. My second crew was a crew that was at each other constantly—fighting, bickering, and having power struggles. It was horrible. I flew with them for a month on other deployments. I never ever remembered feeling like, “I can’t wait to go home.” But that’s the way I felt during that time.

We were on one-year orders with an opportunity to extend for a year, so we didn’t know when we were going to go home. I thought, “This is going to last forever and it’s going to kill me.” Thank goodness at the end of that month the crew I was with was in a special group and they got to go. That was hard too, seeing other people go home, especially after this difficult time I had been through with this crew. Plus, the guy who I had been dating sent me a “dear John,” and it was right at the height of the war. All of these things were hitting me during this one period of time. The next crew, which was my last crew, I spent the most time with, probably two and a half or almost three months with them. They were a great crew, so then I thought, “Maybe I can make it now.”

This whole time I kept thinking, “I can’t wait to go home,” and I had never felt like that on deployments before. Then I get home and it was like, “I can’t wait to go back,” because life is so hard now. It’s hard to get back into a schedule and routine. I don’t know what normal life is like. I don’t have a job, well I’m still on active duty. I had three weeks off. I was commuting back and forth from Riverside to the base. We get home, we have three weeks off. That was the hardest three weeks of my life. I had people living in my home who were moving out since I was moving back in. I wanted my house back. Then finally I got to live in my house. I woke up every morning and wondered, “What do I do?” There are so many things to do and you’re overwhelmed, so you don’t do anything. Then I found out that I had to start going back up to the base. It was such a relief and it felt so good to be around people who I had been deployed with, people who had been through the same thing that I had and understood the stressors. And they were all going through the same thing too. It was so good to get back to our family, our military family. It’s weird now to be uncomfortable with your own family and to be very comfortable with your military family. That was my life. With my own family now, I have more of a level of comfort. When I first got back, I stayed with my brother for a week because people were still in my house. I didn’t feel comfortable there because it wasn’t my home. People always want to know how it was and what I did, and if they don’t ask, you wonder why they’re not. You’re uncomfortable sometimes when they do. And now there are some who say, “I didn’t know what to ask or what to say, so I just didn’t.”

You had such a structured life being on active duty for so long, and then all of a sudden there’s no structure whatsoever. You felt overwhelmed, so you just didn’t do anything because it was easier than having to tackle all these things. I guess for me, I felt like I needed to give myself permission to take a break. I’ve been through all this; it’s okay to just sit on the couch and do nothing. My favorite thing was just flipping through the channels not watching anything because while I was deployed, we didn’t have TV that we could understand. In Italy it was all in Italian. In Germany we did have some TV, but nothing was familiar. So once I got home, it was like, “I have ninety-six channels that I can flip through.” I wouldn’t concentrate on any of them; I just wanted to see what they were.

The three weeks were hard, but I did feel like I needed them physically, especially because your sleep cycle is weird. It takes time to just get your sleep cycle back on track. When you’re deployed, you slept, but you were always one step ahead of yourself. Alert days were hard because you were always in a state of “What’s going to happen today?” You just never knew. It got to the point after a while where you just got so used to it that it wasn’t a big deal any more.

When I got back, I did not want to share anything. Part of you feels like it’s a very personal experience and if somebody hasn’t been there, they can’t understand it. When they do ask you specifically or they invite you to talk about it, you tend to be very superficial. You tell them pretty much what they already know—what they’ve seen on the news. Every once in a while you’ll interject something like, “The seventy patients . . . ‘ or something like that. But you never talk about how scared you were when you flew into the desert because of the intelligence briefing you got beforehand about how you might get shot and where the RPGs are located and what they’re aiming at and the chemical possibilities and how you’re having to strap on all your chem gear when you land in the desert. All this kind of stuff. The first several weeks when we flew in, we were getting these intelligence briefings, and that was enough to scare the crap out of us. So that was hard. You don’t talk a lot about that stuff. When we got back, unfortunately, it wasn’t until about three or four months after we got back that our squadron had a debriefer. We didn’t get debriefed until everybody was pretty much getting over it. We had already talked amongst ourselves. We went through about a month where everybody in our squadron didn’t really say anything until one person said, “Are you having any difficulties now that we’re back?” And I said, “Yeah!” Then we asked a couple of other people, and it turns out that everybody is having some sense of difficulty. Maybe not the same but in some facet of their life they’re having some difficulty. We all talked about it, and then all of a sudden we’re getting a debriefer.

I still keep in touch with the people in my squadron that were deployed at the same time. I see them every month. That’s very nice because we all have a bond. The other people, we have bonds with them too, but it’s a little different, not as strong. There are a couple of other people from different squadrons that I ended up flying with that I still keep in touch with. That’s really neat to see what they’re going through now. I got an e-mail from one of the guys I flew with the longest, and he talked about some of the difficulties he’d been through, so I wrote him back. He wrote me back and said, “I don’t know if you knew this, but every time something happened or something came up that was difficult on the mission, I always kind of turned to you for validation or to make sure it was okay or what I did was right.” I thought that was so sweet. I never realized that. But it’s nice to hear stuff like that, especially with him, because I looked at him as being the guy in charge. He was the strong man, but he never showed his fear. The sign of a good leader is not showing how scared you really are.

I had been e-mailing the guy who sent me a “dear John.” We only started dating two or three months before I left, but we were talking to each other every day and going out every other night before I left. We were pretty close. I had been gone about two months, and looking back I can tell that his e-mails had slipped off a little bit. Then I remember the day that I got the e-mail. We were able to go check our e-mails at either the library or tent or wherever the computers were set up. Like I say, it was that time when I was on that really hard crew, and when I got the e-mail, it was something I couldn’t share with anybody. I didn’t feel close enough with anybody on my crew that I could share that, so I kept it inside. The other nurse who was very difficult was my roommate at the time. After I got the e-mail, I just remember I was walking home in the dark and went in between two buildings where I knew no one would see me, and I just leaned up against the wall and slid down to ground and was just bawling. I had to let it out and that was the only way I could then. That was really hard.

Through the Church, I had really great support. I had been the Relief Society president before I left, so the ward knew me. That was really nice. I would get a lot of e-mails. Every week the Achievement Day girls would get together and spend the last five minutes of their meeting writing to me. Their leader would then send all their cards to me. That was really special. Every week I would get a packet.

I have two big brothers; neither one has been in the military. My dad was actually in the navy for four years during Korea. They didn’t call them this back then, but he was a SEAL. He underwater demolitions and all that good stuff. UDT is what they called them then. It’s funny because once I joined the military, he started opening up and telling me a couple of stories. Then when I would go on deployments, especially after Somalia because I would write back all the time, he would open up a lot more. Especially now, after this one, I got back in August. My dad was a fireman, and he got emphysema really bad because he was a smoker, plus all the smoke from the fires, so he just moved in with me in November. He lives with me now, and we have more opportunity to talk. It’s nice to talk about things with my dad, especially about things that he’s kept in for so many years.

He worries a lot, especially now. When he was living in Georgia, he didn’t know when I would go off on the weekends or whatever, but now that he’s living with me, he knows. This weekend I’m going to be gone on a three-day mission, and he worries now because our planes are old and they’re falling apart. He would never tell me how much he worried, but when I got home I could tell by some of the things he said that he was definitely worried. But he didn’t want to let on to that, because he wanted to support me. He didn’t want me to worry about him worrying.