The Korean War

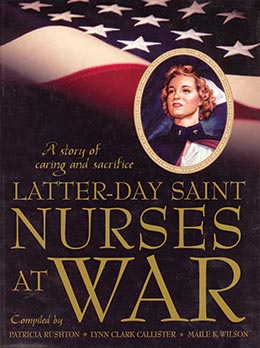

Patricia Rushton, Lynn Clark Callister, Maile K. Wilson, comps., Latter-day Saint Nurses at War: A Story of Caring and Sacrifice (Provo, Utah: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2005) 155–160.

Historical Background

At the end of World War II, Korea was divided at the 38th parallel by the United States and the Soviet Union. The USSR supported a communist government in North Korea, and the United States successfully supported the installation of a democratic government in South Korea. In the post-World War II forties and fifties there was great national concern over the spread of communism. This concern intensified into an anti-Communist hysteria (Roark 1998, 1048) in June 1950 when ninety thousand North Koreans crossed the 38th parallel into South Korea. President Harry Truman’s advisers felt that the communist governments of Russia or China or both had instigated the attack. Thirty years later, former Soviet leaders indicated that the Kremlin had simply acquiesced to North Korean plans. However, on June 30, 1950, Truman decided to commit ground troops in Korea. Roark states,

Sixteen nations, including many of the NATO allies, sent troops to Korea, but the United States contributed most of the personnel and weapons. The United States deployed almost 1.8 million troops in Korea and essentially dictated military strategy. Yet Congress never declared war. Truman himself refused to call it a war. At first he said that it was simply the United States, as a member of the United Nations, “going to the relief of the Korean Republic to suppress a bandit raid.” When pressed by a reporter, he agreed that it was a “police action under the United Nations,” and “police action” became the official label for the war. (1050)

The “police action” seesawed from one side to the other. From June to September, North Korean troops punished United Nations troops and advanced south to Pusan, South Korea. In September, UN troops led by General Douglas McArthur advanced toward the 38th parallel from both North and South Korea and liberated Seoul. In November, UN troops were within forty miles of the Korean-Chinese border, but one hundred fifty thousand Chinese troops came across the border over the Yalu River and drove UN troops south of the 38th parallel and recaptured Seoul. Three months later the UN troops advanced again to the 38th parallel, and President Truman decided to negotiate a peace.

The peace negotiations began in July 1951 and were not concluded until July 1953. Talks went on amid a great deal of controversy in the United States about whether the United States should push to eliminate the Communist threat in Korea and Asia or settle on containment of the Communist “threat” to its previous borders. The controversy cost Harry Truman his popularity and the Democratic Party the U.S. presidency. More importantly, the conflict had a high cost in lives and materials. Again Roark recounts,

In July 1953, the two sides reached an armistice that left Korea divided as it had been three years earlier. The war took the lives of 54,000 and wounded more than 100,000 Americans. Total UN casualties included 118,515 killed, 264,591 wounded, and 92,987 captured, most of who did not return alive.

Korean and civilian casualties were heavier still. More than 1.6 million North Koreans and Chinese were killed or wounded and 3 million South Koreans died of war-related causes. The nature of the war and the unpopularity of the Rhee (South Korean) government made it difficult for soldiers to distinguish between friends and enemies, since civilian populations sometimes harbored North Korea agents. Consequently, as one journalist reported, the situation “forced upon our men in the field, acts and attitudes of the utmost savagery” the blotting out of villages where the enemy might be hiding, the shooting and shelling of refugees who may be North Koreans. (1054)

The Korean War is sometimes referred to as the “Forgotten War.” Dr. Paul Edwards (Scott, 2001) says, “It’s not that the Korean War is being forgotten, it’s just that Americans don’t think of it . . . and the government has ignored it’” (26). The Korean War veterans did not come home to the glorious homecoming that had welcomed veterans of World War II. “They would have to return from an unresolved political conflict to an American culture no longer interested in identifying with the GI experience. Korean War veterans were the first to experience this dispiriting phenomenon that would be prevalent for years to come.” (26)

Though articles and books about military nursing during the Korean War are few in number, at least two accounts summarize, in some detail, the work of navy and army nurses during that conflict. Captain (ret) Doris M. Sterner (1996) and Colonel (ret) Mary T. Sarnecky (1999) have written histories of the U.S. Navy and Army Nurse Corps, respectively. These histories provide excellent information about the status of nursing care provided to members of the military during the Korean conflict. Only a brief summary of their histories is appropriate for this account.

Health-care conditions in Korea at the end of World War II were inferior to those of Japan. Sarnecky (1999) notes that the system in Japan was “comparable to that in existence two hundred years previously in colonial America” (286). In 1947, shortly before the Korean conflict began, Ianthe Swope, first lieutenant, described the conditions at the 71st Station Hospital in Pusan, Korea. “During the biting damp cold of the winter season the wards were not warm. More than one day no baths were given because of the cold. Though we wore the brown and white striped seersucker uniform during the day, the night nurses were permitted to wear wool shirts and trousers . . . [and the] liner to [the] field jacket. As cold as it was on the wards I did on occasion return to the ward or stay around in an inconspicuous place to keep warmer than I would have if I had been in Quarters” (286). The nurses who worked in these conditions worked twelve to sixteen hour shifts with minimal nursing staff as a result of the drawdown of military troops after World War II. They became proficient at putting up whole tent hospitals and base camp facilities in the shortest possible time in order to begin caring for patients. They took care of patients on ships such as the USS Consolation, Haven, and Repose; on trains; in helicopters; and in vacant schools. They took care of many times more patients than their facilities were designed to accommodate. They provided care for active duty troops, civilians, Korean POWs, and orphans. They were pioneers in the use of new medical and nursing techniques such as dialysis, vessel grafting, care of cold weather injuries, and new developments in amputee care, which accounted for saving lives and limbs, improving patient care, and increasing quality of life. They became the first to practice what would become principles of critical care. They became independent practitioners who functioned at high levels of assessment and critical thinking. They performed medical and surgical techniques to allow physicians to provide more complicated care to a greater number of patients. They took care of patients while the military was advancing, retreating, being shot at, and dying. They too were attacked, and some died. Others returned home to struggle with the memories and the horrors of war. They were an amazing group of nurses.

Bonnie Jean Hughes Hubbard

After high school my parents encouraged me to go to college. I wanted to go to Brigham Young University with some friends, but it was beyond our financial means. I could go to the University of Utah in Salt Lake City, and I could live at home.

I remember getting off the bus at the university, which seemed huge. After awhile, I found the administration building. Both my sister Elaine, a registered nurse (RN), and Mom wanted me to consider nursing. It wasn’t something I had always wanted to do, but looking at the long lines and hundreds of students waiting, it suddenly sounded good when I found a very short line and a large sign that read “Nursing.”

College degrees were new to the nursing field. You could be a licensed practical nurse (LPN) in a year and a diploma RN in three. Most people thought it was silly to spend four years when you could get an RN certificate in three. The year 1949 was only the second year the university had a nursing school where you could get an RN and a bachelor of science (BS) degree. We went four quarters a year for four years. They had not decided what could be left out of the nursing program or basic BS curriculum, so we got it all.

I worked sixteen hours a week as a hospital aide the first year of college, so I was very busy studying, taking classes, and working.

I moved into the County Hospital School of Nursing dormitory the summer of 1950. On June 15, 1951, “capping” exercises were performed. Most nurses do not wear caps now, but then it was a big deal. It meant you had passed your probation and someone thought you could really be a nurse!

There were fifteen in our class—all female. The next year would see four leave. In August 1953, not only were we ready to graduate from the university, but the Salt Lake County Hospital also held a “pinning” ceremony. We all took the Florence Nightingale Pledge. Eleven of us dear, dear, friends had laughed and cried, studied and played together. We spent long nights cramming together. We supported each other through giving our first enemas, inserting our first nasal gastric tubes, delivering our first babies, and experiencing our first surgeries. We tried to comfort the psychiatric patients and support the public health crisis. We dated the interns and resident physicians and essentially became a family. We even bought a car together when we got tired of riding the bus to the university.

After graduation we took the state board exam to become registered nurses. The exam was a national test. It took ten hours for two days and had six sections. It was three months before we learned the results of the test.

During that time, I worked at the county hospital as a graduate nurse, as did most of my classmates. Since nurses were very scarce, they relied on us for lots of different positions and different shifts. I worked from June to December as the head nurse of a sixty-five-bed male medical floor.

After graduation we faced the big problem of what now? Four of the class joined the U.S. Public Health Service and were assigned to Alaska. My roommate, Alice Coyte, met her husband there and has been there ever since. Three were married right away and started their families. Two returned to their hometown to work. Two joined the U.S. Army to see the world. Barbara Kerr and I were off for an adventure. It was during the Korean War, and not only did it seem a patriot-type thing to do, but we both really wanted to see something besides Utah. Later, when we moved to Ohio in 1957, I registered in that state.

Barbara Kerr and I left Salt Lake City on a wintry day in late February 1954. My parents were a bit reluctant to send me out into the big world, and my brothers were appalled. My brothers had all been in the services and had a low opinion of army nurses. In the end, they all sent me off with their blessings.

We were second lieutenants and were headed for Fort Sam Houston, Texas, for officers’ training school. We spent two months learning how to read a map, salute, march, set up camp, survive in the wilderness, shoot a gun, purify water, control insects, build a latrine, and survive chemical and atomic warfare, just to name a few things.

After basic training, Barbara and I were assigned to Fort Hood, Texas, the army’s tank center. It had been some time since we had done any nursing, so it was good to get back to a hospital. It was in the middle of nowhere, but the men outnumbered the women eight hundred to one, which made the social life good. Six nurses from basic training went with us. It was a surprise when three of us received orders to go to the Far East in less than three months. Even though the Korean War was going strong, we were told the chance of going there was slim. Everyone was sure we would be stationed in Japan, so we took a foot locker full of pretty clothes.

We landed in Japan and never left the airport before we were being fitted with boots, long underwear, and fatigues. All three of us arrived at a MASH unit on the 38th parallel in Korea, on a cold, rainy day in October, less than three days after we left hot, sunny Texas.

We lived in tents at the MASH and learned to pack up an entire medical unit in half an hour. There were constant helicopters bringing in the wounded, and we worked eighteen to twenty hours a day. We could have a shower every three days, and we were assigned to use the latrine twice a day (6:00 a.m. to 8:00 p.m.). There was only one, so since there were only three women and lots of men, certain hours were assigned.

It was a busy and sad time. Several young men died, but we were also able to save many and send them on to the evacuation hospital. It was a United Nations effort, so we had many patients from many different nations. I was especially impressed with the Turkish soldiers.

After the fighting stopped and the truce was signed, we moved to an evacuation hospital. It was a bombed-out building with no roof or running water, but it was better than the tents. We had a bathroom just for females (there were eight of us), and we could shower every other day. We lived in Quonset huts. Toilet paper was a priority. Every month Mom would send me a boxful, and I was so popular when it arrived.

The nicest thing about Seoul was the fact that I got to meet many of the Korean people. I taught English classes to Korean doctors and nurses and got to visit their villages, shrines, and homes. There also was an LDS branch in Seoul, and when I could get Sunday off I could go to church, which was something I had really missed.

In October 1955, I was promoted to first lieutenant. I also was evacuated from Korea in late December 1955 when I was infected with hepatitis B from a contaminated needle. I flew directly to Hawaii and then on to Denver, Colorado, the nearest army hospital to my family. I was in Fitzsimmons Army Hospital in Denver for nearly three months. When I was well, I was assigned to Madigan Army Hospital in Tacoma, Washington. I was there for one year, from March 1956 to March 1957, and then I was discharged from active duty with the army.

Barbara G. Toomer

I went into nursing because we were just coming out of the Depression and my family did not have much money. I just happened to run into somebody who knew about St. Joseph’s College of Nursing in San Francisco. She said, “Why don’t you apply?” I did. I was living in Manhattan Beach, California, at the time. That was how I wound up as a nurse. It was none of those longtime ambitions or always-wanted-to-do-it things. It was, “Here is the opportunity. Do you want to take it?” Yes indeed I did.

I went to El Camino Junior College and graduated from there in 1949. After that I went to San Francisco to St. Joseph’s College of Nursing. My nursing program was from 1949 to 1952. It was a three-year program. At that time the four- and five-year programs were just coming into effect, but we felt as though we were good learners and that we had the hands-on ability to take care of things. That was probably to make us feel better. I know the nurses from the four- and five-year schools looked down on us. They did a lot of classroom work. I remember when I was a probie and I had been there about two days, I got my uniforms and I was on the floor at night and went to class during the day. It was scary, but we did it. After about two months, people started dropping out and I said, “No way. I have put in two weeks or two months (or whatever it was), and this is it.” There were seventeen in my class who graduated, and we started out with twenty-five or twenty-six.

I graduated from St. Joseph’s College of Nursing, which was associated with St. Joseph’s Hospital. Our three-year program was really intensive and we learned. But on the other hand, we did not learn things we should have, that we could have, that other nurses were learning. I did not have the slightest idea how to give an IV, and I had never done a male catheterization. We were back-rubbing bedpan experts. We did basic things, including medications. We were loaded with classes in anatomy, physiology, and nutrition.

We did our pediatrics and communicable diseases in San Francisco General Hospital. In fact, most of the schools of nursing did it there because most hospitals didn’t have pediatric or communicable disease areas. There was nothing in geriatrics. Nursing went from hands-on to supervision, except in places like the ICU.

I graduated in 1952 and I went back home and worked at St. John’s Hospital in Santa Monica as a surgical nurse in the operating room. I wanted to be in OB-GYN, but there wasn’t room. They asked if I would mind going in to OR, and I said I didn’t. I did that for a while. I do not really remember how it came about that I joined the military. The Korean War was on and my father and my family were extremely patriotic. My father unfortunately had a heart murmur, so he could not join the armed services during the Second World War. He bought airplanes for the army at Lockheed. My sister had joined the air force. She had no education; she just joined as a private. It was probably in our blood.

I enlisted in the Army Nurse Corps and was sworn in by my father, a notary public in Manhattan Beach. I was sent to San Antonio to basic training. I was assigned to Fort Bragg, North Carolina, but San Antonio is where I wound up. That was a long way from home, but I had been away from home in San Francisco for three years, so I really was never homesick. I just had a wonderful time, especially in basic training.

The thing I liked best about the army that sticks with me more than anything else was the educational opportunities to learn from physicians and nurses from all over the country. You really learned different techniques and different ways of looking at things. I had not realized we were so sheltered, but we (nursing students at St. Joseph’s) really were medically sheltered. I had never given an IV. I was assigned to the emergency room and it was at that point the doctor showed me how to give an IV. In training I had taken care of patients with IVs, but the nurses couldn’t give them. You had to call a doctor or resident to do it. You were really leery about residents because they did not have the knowledge. It is really a pecking order in the medical profession.

In the army I had to know how to put in an IV because I was running an emergency room. We had a doctor in the ER all the time, but this was an active-duty post. We had special forces and paratroopers—young kids who were doing crazy things. These were gung ho guys who felt as though they were superman and were surprised when they got hurt. I learned how to use a Stryker frame. I had never seen a Stryker frame and did not know anything about spinal cord injuries. These kids were diving into this lake that said “No Swimming, No Diving, Shallow Water, Off Limits!” Of course we had broken necks. We also had people from the war coming back who lived in that area or whose home residence was in the confines of North Carolina, South Carolina, and Virginia.

The hospital had at least five hundred beds. They were long dormitory-type open wards, except in certain areas like the officers’ wards and the women’s and dependants’ areas. We took care of everything from people who had fainted all the way up to broken backs and broken bones. I was able to continue to do things that had originally been considered physicians’s tasks, like starting IVs and drawing blood. In my time at Fort Bragg I was in the OR and was in charge of a couple of wards and the emergency room. I was the charge nurse on the 4:00 to12:00 shift for six months.

I was at Fort Bragg for the full two years. I never moved. I had a two-year commitment. Just before my two-year commitment was up, I was pregnant. At that time as soon as you said you were pregnant—oops, out you go—so I did not want to let them know. When my husband was assigned to Saigon, I was assigned to Tokyo. Since I had served two years, I got out. I saw my husband off at the air force base at Travis Field in California. Then I stayed in California and had my oldest daughter.

In Fort Bragg we spent two to four weeks out in the field in a MASH field hospital. I remember this master sergeant coming in the door of the tent, strapped down with weapons, and I said, “Leave those guns at the door. I don’t want to see guns in here.” I don’t like weapons. I certainly didn’t want them in my MASH unit; that is for sure. I remember him standing there and saying, “Lieutenant, these aren’t guns, they are weapons.” I said, “Well then, leave those weapons outside.” We ran that MASH unit for practice; it was a field exercise. We were in the field during April. I remember going from the field to church on Easter Sunday in a helicopter. They dropped me off by my barracks and I changed uniforms, went to church, came back, changed uniforms, got back into the helicopter, and went back into the field.

There was a male student in my nursing class in San Francisco. It was sort of an experimental thing. Paul was really a great kid. There was no problem with Paul, and he graduated with us and became an RN with us. The nuns thought he was wonderful—the sun rose and set around Paul. I stayed in San Francisco about six weeks preparing for my state boards. Paul and I both worked on the wards, and he earned more money than I did. I went to the sisters and I said, “This is not right, we are classmates, we are both here for only six weeks while we are studying to pass our state boards. What is the deal here?” She said, “Well, he is going to have a family someday.” I didn’t like that idea at all, but a little while later while I was in the army, along comes Paul with the sergeant’s stripes. They wouldn’t give him a commission as a nurse because he was male. I don’t know when that changed, probably between 1956 and 1960, but it did change by Vietnam. I do know that he was an RN and that he was there as an RN.

Being in the military was a wonderful experience professionally and personally. I think the military changed my outlook on people as a whole.